The History of Obstetric Anesthesia

Donald Caton MD

For I heard a cry as of a woman in travail, anguish as of one bringing forth her first child, the cry of the daughter of Zion gasping for breath, stretching out her hands, “Woe is me!”

—JEREMIAH 4:31

Chapter Outline

MEDICAL OBJECTIONS TO THE USE OF ETHER FOR CHILDBIRTH

PUBLIC REACTION TO ETHERIZATION FOR CHILDBIRTH

THE EFFECTS OF ANESTHESIA ON THE NEWBORN

“The position of woman in any civilization is an index of the advancement of that civilization; the position of woman is gauged best by the care given her at the birth of her child.” So wrote Haggard1 in 1929. If his thesis is true, Western civilization made a giant leap on January 19, 1847, when James Young Simpson used diethyl ether to anesthetize a woman with a deformed pelvis for delivery. This first use of a modern anesthetic for childbirth occurred a scant 3 months after Morton’s historic demonstration of the anesthetic properties of ether at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Strangely enough, Simpson’s innovation evoked strong criticism from contemporary obstetricians, who questioned its safety, and from many segments of the lay public, who questioned its wisdom. The debate over these issues lasted more than 5 years and influenced the future of obstetric anesthesia.2

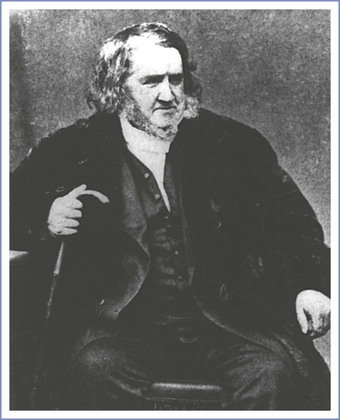

James Young Simpson

Few people were better equipped than Simpson to deal with controversy. Just 36 years old, Simpson already had 7 years’ tenure as Professor of Midwifery at the University of Edinburgh, one of the most prestigious medical schools of its day (Figure 1-1). By that time, he had established a reputation as one of the foremost obstetricians in Great Britain, if not the world. On the day he first used ether for childbirth, he also received a letter of appointment as Queen’s Physician in Scotland. Etherization for childbirth was only one of Simpson’s contributions. He also designed obstetric forceps (which still bear his name), discovered the anesthetic properties of chloroform, made important innovations in hospital architecture, and wrote a textbook on the practice of witchcraft in Scotland that was used by several generations of anthropologists.3

FIGURE 1-1 James Young Simpson, the obstetrician who first administered a modern anesthetic for childbirth. He also discovered the anesthetic properties of chloroform. Many believe that he was the most prominent and influential physician of his day. (Courtesy Yale Medical History Library.)

An imposing man, Simpson had a large head, a massive mane of hair, and the pudgy body of an adolescent. Contemporaries described his voice as “commanding,” with a wide range of volume and intonation. Clearly Simpson had “presence” and “charisma.” These attributes were indispensable to someone in his profession, because in the mid-nineteenth century, the role of science in the development of medical theory and practice was minimal; rhetoric resolved more issues than facts. The medical climate in Edinburgh was particularly contentious and vituperative. In this milieu, Simpson had trained, competed for advancement and recognition, and succeeded. The rigor of this preparation served him well. Initially, virtually every prominent obstetrician, including Montgomery of Dublin, Ramsbotham of London, Dubois of Paris, and Meigs of Philadelphia, opposed etherization for childbirth. Simpson called on all of his professional and personal finesse to sway opinion in the ensuing controversy.

Medical Objections to the Use of Ether for Childbirth

Shortly after Simpson administered the first obstetric anesthetic, he wrote, “It will be necessary to ascertain anesthesia’s precise effect, both upon the action of the uterus and on the assistant abdominal muscles; its influence, if any, upon the child; whether it has a tendency to hemorrhage or other complications.”4 With this statement he identified the issues that would most concern obstetricians who succeeded him and thus shaped the subsequent development of the specialty.

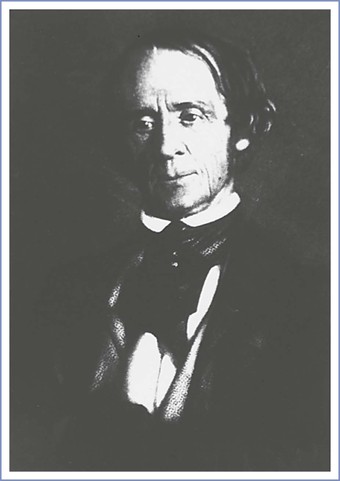

Simpson’s most articulate, persistent, and persuasive critic was Charles D. Meigs, Professor of Midwifery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia (Figure 1-2). In character and stature, Meigs equaled Simpson. Born to a prominent New England family, Meigs’ forebears included heroes of the American revolutionary war, the first governor of the state of Ohio, and the founder of the University of Georgia. His descendants included a prominent pediatrician, an obstetrician, and one son who served the Union Army as Quartermaster General during the Civil War.5

FIGURE 1-2 Charles D. Meigs, the American obstetrician who opposed the use of anesthesia for obstetrics. He questioned the safety of anesthesia and said that there was no demonstrated need for it during a normal delivery. (Courtesy Wood-Library Museum.)

At the heart of the dispute between Meigs and Simpson was a difference in their interpretation of the nature of labor and the significance of labor pain. Simpson maintained that all pain, labor pain included, is without physiologic value. He said that pain only degrades and destroys those who experience it. In contrast, Meigs argued that labor pain has purpose, that uterine pain is inseparable from contractions, and that any drug that abolishes pain will alter contractions. Meigs also believed that pregnancy and labor are normal processes that usually end quite well. He said that physicians should therefore not intervene with powerful, potentially disruptive drugs (Figure 1-3). We must accept the statements of both men as expressions of natural philosophy, because neither had facts to buttress his position. Indeed, in 1847, physicians had little information of any sort about uterine function, pain, or the relationship between them. Studies of the anatomy and physiology of pain had just begun. It was only during the preceding 20 years that investigators had recognized that specific nerves and areas of the brain have different functions and that specialized peripheral receptors for painful stimuli exist.2

In 1850, more physicians expressed support for Meigs’s views than for Simpson’s. For example, Baron Paul Dubois6 of the Faculty of Paris wondered whether ether, “after having exerted a stupefying action over the cerebro-spinal nerves, could not induce paralysis of the muscular element of the uterus?” Similarly, Ramsbotham7 of London Hospital said that he believed the “treatment of rendering a patient in labor completely insensible through the agency of anesthetic remedies … is fraught with extreme danger.” These physicians’ fears gained credence from the report by a special committee of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society documenting 123 deaths that “could be positively assigned to the inhalation of chloroform.”8 Although none involved obstetric patients, safety was on the minds of obstetricians.

The reaction to the delivery of Queen Victoria’s eighth child in 1853 illustrated the aversion of the medical community to obstetric anesthesia. According to private records, John Snow anesthetized the Queen for the delivery of Prince Leopold at the request of her personal physicians. Although no one made a formal announcement of this fact, rumors surfaced and provoked strong public criticism. Thomas Wakley, the irascible founding editor of The Lancet, was particularly incensed. He “could not imagine that anyone had incurred the awful responsibility of advising the administration of chloroform to her Majesty during a perfectly natural labour with a seventh child.”9 (It was her eighth child, but Wakley had apparently lost count—a forgivable error considering the propensity of the Queen to bear children.) Court physicians did not defend their decision to use ether. Perhaps not wanting a public confrontation, they simply denied that the Queen had received an anesthetic. In fact, they first acknowledged a royal anesthetic 4 years later when the Queen delivered her ninth and last child, Princess Beatrice. By that time, however, the issue was no longer controversial.9

Public Reaction to Etherization for Childbirth

The controversy surrounding obstetric anesthesia was not resolved by the medical community. Physicians remained skeptical, but public opinion changed. Women lost their reservations, decided they wanted anesthesia, and virtually forced physicians to offer it to them. The change in the public’s attitude in favor of obstetric anesthesia marked the culmination of a more general change in social attitudes that had been developing over several centuries.

Before the nineteenth century, pain meant something quite different from what it does today. Since antiquity, people had believed that all manner of calamities—disease, drought, poverty, and pain—signified divine retribution inflicted as punishment for sin. According to Scripture, childbirth pain originated when God punished Eve and her descendants for Eve’s disobedience in the Garden of Eden. Many believed that it was wrong to avoid the pain of divine punishment. This belief was sufficiently prevalent and strong to retard acceptance of even the idea of anesthesia, especially for obstetric patients. Only when this tradition weakened did people seek ways to free themselves from disease and pain. In most Western countries, the transition occurred during the nineteenth century. Disease and pain lost their theologic connotations for many people and became biologic processes subject to study and control by new methods of science and technology. This evolution of thought facilitated the development of modern medicine and stimulated public acceptance of obstetric anesthesia.10

The reluctance that physicians felt about the administration of anesthesia for childbirth pain stands in stark contrast to the enthusiasm expressed by early obstetric patients. In 1847, Fanny Longfellow, wife of the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and the first woman in the United States anesthetized for childbirth, wrote:

I am very sorry you all thought me so rash and naughty in trying the ether. Henry’s faith gave me courage, and I had heard such a thing had succeeded abroad, where the surgeons extend this great blessing more boldly and universally than our timid doctors. … This is certainly the greatest blessing of this age.11

Queen Victoria, responding to news of the birth of her first grandchild in 1860 and perhaps remembering her own recent confinement, wrote, “What a blessing she [Victoria, her oldest daughter] had chloroform. Perhaps without it her strength would have suffered very much.”9 The new understanding of pain as a controllable biologic process left no room for Meigs’s idea that pain might have physiologic value. The eminent nineteenth-century social philosopher John Stuart Mill stated that the “hurtful agencies of nature” promote good only by “inciting rational creatures to rise up and struggle against them.”12

Simpson prophesied the role of public opinion in the acceptance of obstetric anesthesia, a fact not lost on his adversaries. Early in the controversy he predicted, “Medical men may oppose for a time the superinduction of anaesthesia in parturition but they will oppose it in vain; for certainly our patients themselves will force use of it upon the profession. The whole question is, even now, one merely of time.”13 By 1860, Simpson’s prophecy came true; anesthesia for childbirth became part of medical practice by public acclaim, in large part in response to the demands of women.

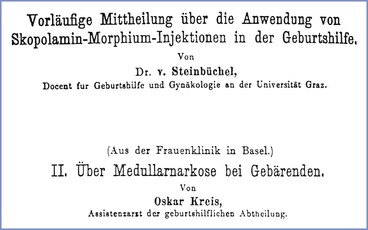

Opioids and Obstetrics

The next major innovation in obstetric anesthesia came approximately 50 years later. Dämmerschlaff, which means “twilight sleep,” was a technique developed by von Steinbüchel14 of Graz and popularized by Gauss15 of Freiberg. It combined opioids with scopolamine to make women amnestic and somewhat comfortable during labor (Figure 1-4). Until that time, opioids had been used sparingly for obstetrics. Although opium had been part of the medical armamentarium since the Roman Empire, it was not used extensively, in part because of the difficulty of obtaining consistent results with the crude extracts available at that time. Therapeutics made a substantial advance in 1809 when Sertürner, a German pharmacologist, isolated codeine and morphine from a crude extract of the poppy seed. Methods for administering the drugs remained unsophisticated. Physicians gave morphine orally or by a method resembling vaccination, in which they placed a drop of solution on the skin and then made multiple small puncture holes with a sharp instrument to facilitate absorption. In 1853, the year Queen Victoria delivered her eighth child, the syringe and hollow metal needle were developed. This technical advance simplified the administration of opioids and facilitated the development of twilight sleep approximately 50 years later.16

FIGURE 1-4 Title pages from two important papers published in the first years of the twentieth century. The paper by von Steinbüchel introduced twilight sleep. The paper by Kreis described the first use of spinal anesthesia for obstetrics.

Although reports of labor pain relief with hypodermic morphine appeared as early as 1868, few physicians favored its use. For example, in an article published in Transactions of the Obstetrical Society of London, Sansom17 listed the following four agents for relief of labor pain: (1) carbon tetrachloride, the use of which he favored; (2) bichloride of methylene, which was under evaluation; (3) nitrous oxide, which had been introduced recently by Klikgowich of Russia; and (4) chloroform. He did not mention opioids, but neither did he mention diethyl ether, which many physicians still favored. Similarly, Gusserow,18 a prominent German obstetrician, described using salicylic acid but not morphine for labor pain. (Von Baeyer did not introduce acetylsalicylic acid to medical practice until 1899.) In retrospect, von Steinbüchel’s and Gauss’s descriptions of twilight sleep in the first decade of the century may have been important more for popularizing morphine than for suggesting that scopolamine be given with morphine.

Physicians reacted to twilight sleep as they had reacted to diethyl ether several years earlier. They resisted it, questioning whether the benefits justified the risks. Patients also reacted as they had before. Not aware of, or perhaps not concerned with, the technical considerations that confronted physicians, patients harbored few doubts and persuaded physicians to use it, sometimes against the physicians’ better judgment. The confrontation between physicians and patients was particularly strident in the United States. Champions of twilight sleep lectured throughout the country and published articles in popular magazines. Public enthusiasm for the therapy subsided slightly after 1920, when a prominent advocate of the method died during childbirth. She was given twilight sleep, but her physicians said that her death was unrelated to any complication from its use. Whatever anxiety this incident may have created in the minds of patients, it did not seriously diminish their resolve. Confronted by such firm insistence, physicians acquiesced and used twilight sleep with increasing frequency.19,20

Although the reaction of physicians to twilight sleep resembled their reaction to etherization, the medical milieu in which the debate over twilight sleep developed was quite different from that in which etherization was deliberated. Between 1850 and 1900, medicine had changed, particularly in Europe. Physiology, chemistry, anatomy, and bacteriology became part of medical theory and practice. Bright students from America traveled to leading clinics in Germany, England, and France. They returned with new facts and methods that they used to examine problems and critique ideas. These developments became the basis for the revolution in American medical education and practice launched by the Flexner report published in 1914.21

Obstetrics also changed. During the years preceding World War I, it had earned a reputation as one of the most exciting and scientifically advanced specialties. Obstetricians experimented with new drugs and techniques. They recognized that change entails risk, and they examined each innovation more critically. In addition, they turned to science for information and methods to help them solve problems of medical management. Developments in obstetric anesthesia reflected this change in strategy. New methods introduced during this time stimulated physicians to reexamine two important but unresolved issues, the effects of drugs on the child, and the relationship between pain and labor.

The Effects of Anesthesia on the Newborn

Many physicians, Simpson included, worried that anesthetic drugs might cross the placenta and harm the newborn. Available information justified their concern. The idea that gases cross the placenta appeared long before the discovery of oxygen and carbon dioxide. In the sixteenth century, English physiologist John Mayow22 suggested that “nitro aerial” particles from the mother nourish the fetus. By 1847, physiologists had corroborative evidence. Clinical experience gave more support. John Snow23 observed depressed neonatal breathing and motor activity and smelled ether on the breath of neonates delivered from mothers who had been given ether. In an early paper, he surmised that anesthetic gases cross the placenta. Regardless, some advocates of obstetric anesthesia discounted the possibility. For example, Harvard professor Walter Channing denied that ether crossed the placenta because he could not detect its odor in the cut ends of the umbilical cord. Oddly enough, he did not attempt to smell ether on the child’s exhalations as John Snow had done.24

In 1874, Swiss obstetrician Paul Zweifel25 published an account of work that finally resolved the debate about the placental transfer of drugs (Figure 1-5). He used a chemical reaction to demonstrate the presence of chloroform in the umbilical blood of neonates. In a separate paper, Zweifel26 used a light-absorption technique to demonstrate a difference in oxygen content between umbilical arterial and venous blood, thereby establishing the placental transfer of oxygen. Although clinicians recognized the importance of these data, they accepted the implications slowly. Some clinicians pointed to several decades of clinical use “without problems.” For example, Otto Spiegelberg,27 Professor of Obstetrics at the University of Breslau, wrote in 1887, “As far as the fetus is concerned, no unimpeachable clinical observation has yet been published in which a fetus was injured by chloroform administered to its mother.” Experience lulled them into complacency, which may explain their failure to appreciate the threat posed by twilight sleep.

FIGURE 1-5 Paul Zweifel, the Swiss-born obstetrician who performed the first experiments that chemically demonstrated the presence of chloroform in the umbilical blood and urine of infants delivered by women who had been anesthetized during labor. (Courtesy J.F. Bergmann-Verlag, München, Germany.)

Dangers from twilight sleep probably developed insidiously. The originators of the method, von Steinbüchel and Gauss, recommended conservative doses of drugs. They suggested that 0.3 mg of scopolamine be given every 2 to 3 hours to induce amnesia and that no more than 10 mg of morphine be administered subcutaneously for the whole labor. Gauss, who was especially meticulous, even advised physicians to administer a “memory test” to women in labor to evaluate the need for additional scopolamine. However, as other physicians used the technique, they changed it. Some gave larger doses of opioid—as much as 40 or 50 mg of morphine during labor. Others gave additional drugs (e.g., as much as 600 mg of pentobarbital during labor as well as inhalation agents for delivery). Despite administering these large doses to their patients, some physicians said they had seen no adverse effects on the infants.28 They probably spoke the truth, but this probability says more about their powers of observation than the safety of the method.

Two situations eventually made physicians confront problems associated with placental transmission of anesthetic drugs. The first was the changing use of morphine.29 In the latter part of the nineteenth century (before the enactment of laws governing the use of addictive drugs), morphine was a popular ingredient of patent medicines and a drug frequently prescribed by physicians. As addiction became more common, obstetricians saw many pregnant women who were taking large amounts of morphine daily. When they tried to decrease their patients’ opioid use, several obstetricians noted unexpected problems (e.g., violent fetal movements, sudden fetal death), which they correctly identified as signs of withdrawal. Second, physiologists and anatomists began extensive studies of placental structure and function. By the turn of the century, they had identified many of the physical and chemical factors that affect rates of drug transfer. Thus, even before twilight sleep became popular, physicians had clinical and laboratory evidence to justify caution. As early as 1877, Gillette30 described 15 instances of neonatal depression that he attributed to morphine given during labor. Similarly, in a review article published in 1914, Knipe31 identified stillbirths and neonatal oligopnea and asphyxia as complications of twilight sleep and gave the incidence of each problem as reported by other writers.

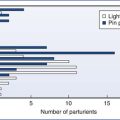

When the studies of obstetric anesthesia published between 1880 and 1950 are considered, four characteristics stand out. First, few of them described effects of anesthesia on the newborn. Second, those that did report newborn apnea, oligopnea, or asphyxia seldom defined these words. Third, few used controls or compared one mode of treatment with another. Finally, few writers used their data to evaluate the safety of the practice that they described. In other words, by today’s standards, even the best of these papers lacked substance. They did, however, demonstrate a growing concern among physicians about the effects of anesthetic drugs on neonates. Perhaps even more important, their work prepared clinicians for the work of Virginia Apgar (Figure 1-6).

FIGURE 1-6 Virginia Apgar, whose scoring system revolutionized the practice of obstetrics and anesthesia. Her work made the well-being of the infant the major criterion for the evaluation of medical management of pregnant women. (Courtesy Wood-Library Museum.)

Apgar became an anesthesiologist when the chairman of the Department of Surgery at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons dissuaded her from becoming a surgeon. After training in anesthesia with Ralph Waters at the University of Wisconsin and with E. A. Rovenstine at Bellevue Hospital, she returned to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital as Director of the Division of Anesthesia. In 1949, she was appointed professor, the first woman to attain that rank at Columbia University.32

In 1953, Apgar33 described a simple, reliable system for evaluating newborns and showed that it was sufficiently sensitive to detect differences among neonates whose mothers had been anesthetized for cesarean delivery by different techniques (Figure 1-7). Infants delivered of women with spinal anesthesia had higher scores than those delivered with general anesthesia. The Apgar score had three important effects. First, it replaced simple observation of neonates with a reproducible measurement—that is, it substituted a numerical score for the ambiguities of words such as oligopnea and asphyxia. Thus it established the possibility of the systematic comparison of different treatments. Second, it provided objective criteria for the initiation of neonatal resuscitation. Third, and most important, it helped change the focus of obstetric care. Until that time the primary criterion for success or failure had been the survival and well-being of the mother, a natural goal considering the maternal risks of childbirth until that time. After 1900, as maternal risks diminished, the well-being of the mother no longer served as a sensitive measure of outcome. The Apgar score called attention to the child and made its condition the new standard for evaluating obstetric management.

The Effects of Anesthesia on Labor

The effects of anesthesia on labor also worried physicians. Again, their fears were well-founded. Diethyl ether and chloroform depress uterine contractions. If given in sufficient amounts, they also abolish reflex pushing with the abdominal muscles during the second stage of labor. These effects are not difficult to detect, even with moderate doses of either inhalation agent.

Simpson’s method of obstetric anesthesia used significant amounts of drugs. He started the anesthetic early, and sometimes he rendered patients unconscious during the first stage of labor. In addition, he increased the depth of anesthesia for the delivery.34 As many people copied his technique, they presumably had ample opportunity to observe uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage.

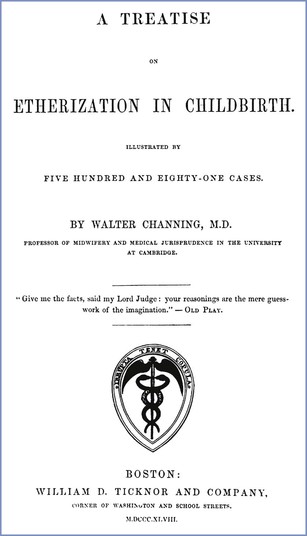

Some physicians noticed the effects of anesthetics on uterine function. For example, Meigs35 said unequivocally that etherization suppressed uterine function, and he described occasions in which he had had to suspend etherization to allow labor to resume. Other physicians waffled, however. For example, Walter Channing,36 Professor of Midwifery and Medical Jurisprudence at Harvard (seemingly a strange combination of disciplines, but at that time neither of the two was thought sufficiently important to warrant a separate chair), published a book about the use of ether for obstetrics (Figure 1-8). He endorsed etherization and influenced many others to use it. However, his book contained blatant contradictions. On different pages Channing contended that ether had no effect, that it increased uterine contractility, and that it suspended contractions entirely. Then, in a pronouncement smacking more of panache than reason, Channing swept aside his inconsistencies and said that whatever effect ether may have on the uterus he “welcomes it.” Noting similar contradictions among other writers, W. F. H. Montgomery,37 Professor of Midwifery at the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland, wrote, “By one writer we are told that, if uterine action is excessive, chloroform will abate it; by another that if feeble, it will strengthen it and add new vigor to each parturient effort.”

FIGURE 1-8 Frontispiece from Walter Channing’s book on the use of etherization for childbirth. Channing favored the use of etherization, and he persuaded others to use it, although evidence ensuring its safety was scant.

John Snow23 gave a more balanced review of the effects of anesthesia on labor. Originally a surgeon, Snow became the first physician to restrict his practice to anesthesia. He experimented with ether and chloroform and wrote many insightful papers and books describing his work (Figure 1-9). Snow’s technique differed from Simpson’s. Snow withheld anesthesia until the second stage of labor, limited administration to brief periods during contractions, and attempted to keep his patients comfortable but responsive. To achieve better control of the depth of anesthesia, he recommended using the vaporizing apparatus that he had developed for surgical cases. Snow23 spoke disparagingly of Simpson’s technique and the tendency of people to use it simply because of Simpson’s reputation:

FIGURE 1-9 John Snow, a London surgeon who gave up his surgical practice to become the first physician to devote all his time to anesthesia. He wrote many monographs and papers, some of which accurately describe the effects of anesthesia on infant and mother. (Courtesy Wood-Library Museum.)

The high position of Dr. Simpson and his previous services in this department, more particularly in being the first to administer ether in labour, gave his recommendations very great influence; the consequence of which is that the practice of anesthesia is presently probably in a much less satisfactory state than it would have been if chloroform had never been introduced.

Snow’s method, which was the same one he had used to anesthetize Queen Victoria, eventually prevailed over Simpson’s. Physicians became more cautious with anesthesia, reserving it for special problems such as cephalic version, the application of forceps, abnormal presentation, and eclampsia. They also became more conservative with dosage, often giving anesthesia only during the second stage of labor. Snow’s methods were applied to each new inhalation agent—including nitrous oxide, ethylene, cyclopropane, trichloroethylene, and methoxyflurane—as it was introduced to obstetric anesthesia.

Early physicians modified their use of anesthesia from experience, not from study of normal labor or from learning more about the pharmacology of the drugs. Moreover, they had not yet defined the relationship between uterine pain and contractions. As physicians turned more to science during the latter part of the century, however, their strategies began to change. For example, in 1893 the English physiologist Henry Head38 published his classic studies of the innervation of abdominal viscera. His work stimulated others to investigate the role of the nervous system in the control of labor. Subsequently, clinical and laboratory studies of pregnancy after spinal cord transection established the independence of labor from nervous control.39 When regional anesthesia appeared during the first decades of the twentieth century, physicians therefore had a conceptual basis from which to explore its effects on labor.

Carl Koller40 introduced regional anesthesia when he used cocaine for eye surgery in 1884. Recognizing the potential of Koller’s innovation, surgeons developed techniques for other procedures. Obstetricians quickly adopted many of these techniques for their own use. The first papers describing obstetric applications of spinal, lumbar epidural, caudal, paravertebral, parasacral, and pudendal nerve blocks appeared between 1900 and 1930 (see Figure 1-4).41–43 Recognition of the potential effects of regional anesthesia on labor developed more slowly, primarily because obstetricians seldom used it. They continued to rely on inhalation agents and opioids, partly because few drugs and materials were available for regional anesthesia at that time, but also because obstetricians did not appreciate the chief advantage of regional over general anesthesia—the relative absence of drug effects on the infant. Moreover, they rarely used regional anesthesia except for delivery, and then they often used elective forceps anyway. This set of circumstances limited their opportunity and motivation to study the effects of regional anesthesia on labor.

Among early papers dealing with regional anesthesia, one written by Cleland44 stands out. He described his experience with paravertebral anesthesia, but he also wrote a thoughtful analysis of the nerve pathways mediating labor pain, an analysis he based on information he had gleaned from clinical and laboratory studies. Few investigators were as meticulous or insightful as Cleland. Most of those who studied the effects of anesthesia simply timed the length of the first and second stages of labor. Some timed the duration of individual contractions or estimated changes in the strength of contractions by palpation. None of the investigators measured the intrauterine pressures, even though a German physician had described such a method in 1898 and had used it to evaluate the effects of morphine and ether on the contractions of laboring women.45

More detailed and accurate studies of the effects of anesthesia started to appear after 1944. Part of the stimulus was a method for continuous caudal anesthesia introduced by Hingson and Edwards,46 in which a malleable needle remained in the sacral canal throughout labor. Small, flexible plastic catheters eventually replaced malleable needles and made continuous epidural anesthesia even more popular. With the help of these innovations, obstetricians began using anesthesia earlier in labor. Ensuing problems, real and imagined, stimulated more studies. Although good studies were scarce, the strong interest in the problem represented a marked change from the early days of obstetric anesthesia.

Ironically, “natural childbirth” appeared just as regional anesthesia started to become popular and as clinicians began to understand how to use it without disrupting labor. Dick-Read,47 the originator of the natural method, recognized “no physiological function in the body which gives rise to pain in the normal course of health.” He attributed pain in an otherwise uncomplicated labor to an “activation of the sympathetic nervous system by the emotion of fear.” He argued that fear made the uterus contract and become ischemic and therefore painful. He said that women could avoid the pain if they simply learned to abolish their fear of labor. Dick-Read never explained why uterine ischemia that results from fear causes pain, whereas ischemia that results from a normal contraction does not. In other words, Dick-Read, like Simpson a century earlier, claimed no necessary or physiologic relationship between labor pain and contractions. Dick-Read’s book, written more for the public than for the medical profession, represented a regression of almost a century in medical thought and practice. It is important to note that contemporary methods of childbirth preparation do not maintain that fear alone causes labor pain. However, they do attempt to reduce fear by education and to help patients manage pain by teaching techniques of self-control. This represents a significant difference from and an important advance over Dick-Read’s original theory.

Some Lessons

History is important in proportion to the lessons it teaches. With respect to obstetric anesthesia, four lessons stand out. First, every new drug and method entails risks. Physicians who first used obstetric anesthesia seemed reluctant to accept this fact, perhaps because of their inexperience with potent drugs (pharmacology was in its infancy) or because they acceded too quickly to patients, who wanted relief from pain and had little understanding of the technical issues confronting physicians. Whatever the reason, this period of denial lasted almost half a century, until 1900. Almost another half-century passed before obstetricians learned to modify their practice to limit the effects of anesthetics on the child and the labor process.

Second, new drugs or therapies often cause problems in completely unexpected ways. For example, in 1900, physicians noted a rising rate of puerperal fever.48 The timing was odd. Several decades had passed since Robert Koch had suggested the germ theory of disease and since Semmelweis had recognized that physicians often transmit infection from one woman to the next with their unclean hands. With the adoption of aseptic methods, deaths from puerperal fever had diminished dramatically. During the waning years of the nineteenth century, however, they increased again. Some physicians attributed this resurgence of puerperal fever to anesthesia. In a presidential address to the Obstetrical Society of Edinburgh in 1900, Murray49 stated the following:

I feel sure that an explanation of much of the increase of maternal mortality from 1847 onwards will be found in, first the misuse of anaesthesia and second in the ridiculous parody which, in many hands, stands for the use of antiseptics. … Before the days of anaesthesia, interference was limited and obstetric operations were at a minimum because interference of all kinds increased the conscious suffering of the patient. … When anaesthesia became possible, and interference became more frequent because it involved no additional suffering, operations were undertaken when really unnecessary … and so complications arose and the dangers of the labor increased.

Changes in obstetric practice also had unexpected effects on anesthetic complications. During the first decades of the twentieth century, when cesarean deliveries were rare and obstetricians used only inhalation analgesia for delivery, few women were exposed to the risk of aspiration during deep anesthesia. As obstetric practice changed and cesarean deliveries became more common, this risk rose. The syndrome of aspiration was not identified and labeled until 1946, when obstetrician Curtis Mendelson50 described and named it. The pathophysiology of the syndrome had already been described by Winternitz et al.,51 who instilled hydrochloric acid into the lungs of dogs to simulate the lesions found in veterans poisoned by gas during the trench warfare of World War I. Unfortunately, the reports of these studies, although excellent, did not initiate any change in practice. Change occurred only after several deaths of obstetric patients were highly publicized in lay, legal, and medical publications. Of course, rapid-sequence induction, currently recommended to reduce the risk of aspiration, creates another set of risks—those associated with a failed intubation.

The third lesson offered by the history of obstetric anesthesia concerns the role of basic science. Modern medicine developed during the nineteenth century after physicians learned to apply principles of anatomy, physiology, and chemistry to the study and treatment of disease. Obstetric anesthesia underwent a similar pattern of development. Studies of placental structure and function called physicians’ attention to the transmission of drugs and the potential effects of drugs on the infant. Similarly, studies of the physiology and anatomy of the uterus helped elucidate potential effects of anesthesia on labor. In each instance, lessons from basic science helped improve patient care.

The fourth and perhaps the most important lesson is the role that patients have played in the use of anesthesia for obstetrics. During the nineteenth century it was women who pressured cautious physicians to incorporate routine use of anesthesia into their obstetric practice. A century later, it was women again who altered patterns of practice, this time questioning the overuse of anesthesia for routine deliveries. In both instances the pressure on physicians emanated from prevailing social values regarding pain. In 1900 the public believed that pain, and in particular obstetric pain, was destructive and something that should be avoided. Half a century later, with the advent of the natural childbirth movement, many people began to suggest that the experience of pain during childbirth, perhaps even in other situations, might have some physiologic if not social value. Physicians must recognize and acknowledge the extent to which social values may shape medical “science” and practice.52,53

During the past 60 years, scientists have accumulated a wealth of information about many processes integral to normal labor: the processes that initiate and control lactation; neuroendocrine events that initiate and maintain labor; the biochemical maturation of the fetal lung and liver; the metabolic requirements of the normal fetus and the protective mechanisms that it may invoke in times of stress; and the normal mechanisms that regulate the amount and distribution of blood flow to the uterus and placenta. At this point, we have only the most rudimentary understanding of the interaction of anesthesia with any of these processes. Only a fraction of the information available from basic science has been used to improve obstetric anesthesia care. Realizing the rewards from the clinical use of such information may be the most important lesson from the past and the greatest challenge for the future of obstetric anesthesia.

References

1. Haggard HW. Devils, Drugs, and Doctors: The Story of the Science of Healing from Medicine-Man to Doctor. Harper & Brothers: New York; 1929.

2. Caton D. What a Blessing. She Had Chloroform: The Medical and Social Response to the Pain of Childbirth from 1800 to the Present. Yale University Press: New Haven; 1999.

3. Shepherd JA. Simpson and Syme of Edinburgh. E & S Livingstone: Edinburgh; 1969.

4. Simpson WG. The Works of Sir JY Simpson, Vol II: Anaesthesia. Adam and Charles Black: Edinburgh; 1871:199–200.

5. Levinson A. The three Meigs and their contribution to pediatrics. Ann Med Hist. 1928;10:138–148.

6. Dubois P. On the inhalation of ether applied to cases of midwifery. Lancet. 1847;49:246–249.

7. Ramsbotham FH. The Principles and Practice of Obstetric Medicine and Surgery in Reference to the Process of Parturition with Sixty-four Plates and Numerous Wood-cuts. Blanchard and Lea: Philadelphia; 1855.

9. Sykes WS. Essays on the First Hundred Years of Anaesthesia. [Vol I] Wood Library Museum of Anesthesiology: Park Ridge, IL; 1982.

10. Caton D. The secularization of pain. Anesthesiology.. 1985;62:493–501.

11. Wagenknecht E. Mrs. Longfellow: Selected Letters and Journals of Fanny Appleton Longfellow (1817-1861). Longmans, Green: New York; 1956.

12. Cohen M. Nature: The Philosophy of John Stuart Mill. Modern Library: New York; 1961:463–467.

13. Simpson WG. The Works of Sir JY Simpson, Vol II: Anaesthesia. Adam and Charles Black: Edinburgh; 1871:177.

14. von Steinbüchel R. Vorläufige mittheilung über die anwendung von skopolamin-morphium-injektionen in der geburtshilfe. Centralblatt Gyn. 1902;30:1304–1306.

15. Gauss CJ. Die anwendung des skopolamin-morphium-dämmerschlafes in der geburtshilfe. Medizinische Klinik. 1906;2:136–138.

16. Macht DI. The history of opium and some of its preparations and alkaloids. JAMA. 1915;64:477–481.

17. Sansom AE. On the pain of parturition, and anaesthetics in obstetric practice. Trans Obstet Soc Lond. 1868;10:121–140.

18. Gusserow A. Zur lehre vom stoffwechsel des foetus. Arch Gyn. 1871;3:241.

19. Wertz RW, Wertz DC. Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in America. Schocken Books: New York; 1979.

20. Leavitt JW. Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750-1950. Oxford University Press: New York; 1986.

21. Kaufman M. American Medical Education: The Formative Years, 1765-1910. Greenwood Press: Westport, CT; 1976.

22. Mayow J. Tractatus quinque medico-physici. Quoted in: Needham J. Chemical Embryology. Hafner Publishing: New York; 1963.

23. Snow J. On the administration of chloroform during parturition. Assoc Med J. 1853;1:500–502.

24. Caton D. Obstetric anesthesia and concepts of placental transport: a historical review of the nineteenth century. Anesthesiology. 1977;46:132–137.

25. Zweifel P. Einfluss der chloroformnarcose kreissender auf den fötus. Klinische Wochenschrift. 1874;21:1–2.

26. Zweifel P. Die respiration des fötus. Arch Gyn. 1876;9:291–305.

27. Spiegelberg O. A Textbook of Midwifery. [Translated by JB Hurry] The New Sydenham Society: London; 1887.

28. Gwathmey JT. A further study, based on more than twenty thousand cases. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1930;51:190–195.

29. Terry CE, Pellens M. The Opium Problem. Bureau of Social Hygiene: Camden, NJ; 1928.

30. Gillette WR. The narcotic effect of morphia on the new-born child, when administered to the mother in labor. Am J Obstet, Dis Women Child. 1877;10:612–623.

31. Knipe WHW. The Freiburg method of däammerschlaf or twilight sleep. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1914;70:884.

32. Calmes SH. Virginia Apgar: a woman physician’s career in a developing specialty. J Am Med Wom Assoc. 1984;39:184–188.

33. Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1953;32:260–267.

34. Thoms H. Anesthesia á la Reine—a chapter in the history of anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1940;40:340–346.

35. Meigs CD. Obstetrics, the Science and the Art. Blanchard and Lea: Philadelphia; 1865.

36. Channing W. A Treatise on Etherization in Childbirth. William D. Ticknor and Company: Boston; 1848.

37. Montgomery WFH. Objections to the Indiscriminate Administration of Anaesthetic Agents in Midwifery. Hodges and Smith: Dublin; 1849.

38. Head H. On disturbances of sensation with especial reference to the pain of visceral disease. Brain. 1893;16:1–1132.

39. Gertsman NM. Über uterusinnervation an hand des falles einer geburt bei quersnittslähmung. Monatsschrift Gebürtshüfle Gyn. 1926;73:253–257.

40. Koller C. On the use of cocaine for producing anaesthesia on the eye. Lancet. 1884;124:990–992.

41. Kreis O. Über medullarnarkose bei gebärenden. Centralblatt Gynäkologie. 1900;28:724–727.

42. Bonar BE, Meeker WR. The value of sacral nerve block anesthesia in obstetrics. JAMA. 1923;89:1079–1083.

43. Schlimpert H. Concerning sacral anaesthesia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1913;16:488–492.

44. Cleland JGP. Paravertebral anaesthesia in obstetrics. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:51–62.

45. Hensen H. Ueber den einfluss des morphiums und des aethers auf die wehenthätigkeit des uterus. Archiv für Gynakologie. 1898;55:129–177.

46. Hingson RA, Edwards WB. Continuous caudal analgesia: an analysis of the first ten thousand confinements thus managed with the report of the authors’ first thousand cases. JAMA. 1943;123:538–546.

47. Dick-Read G. Childbirth Without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth. Harper & Row: New York; 1970.

48. Lea AWW. Puerperal Infection. Oxford University Press: London; 1910.

49. Murray M. Presidential address to the Obstetrical Society of Edinburgh, 1900. Quoted in: Cullingworth CJ. Oliver Wendell Holmes and the contagiousness of puerperal fever. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1905;8:387–388.

50. Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191–205.

51. Winternitz MC, Smith GH, McNamara FP. Effect of intrabronchial insufflation of acid. J Exp Med. 1920;32:199–204.

52. Caton D. “The poem in the pain”: the social significance of pain in Western civilization. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:1044–1052.

53. Caton D. Medical science and social values. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:167–173.