Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

Lawrence C. Tsen MD

Chapter Outline

History

Cesarean delivery is defined as the birth of an infant through incisions in the abdomen (laparotomy) and uterus (hysterotomy). Although the technique is commonly associated with the birth of the Roman Emperor Julius Caesar, medical historians question this possibility, given his birth in an era in which such operations were invariably fatal (100 BC) and the acknowledged presence of Caesar’s mother in his later life.1 Although the term cesarean section is commonly used, the Latin words caedere and sectio both imply “to cut,” and modern linguists argue that use of both words is redundant. Consequently, cesarean delivery is the preferred term.

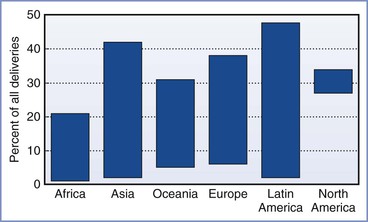

Morbidity and mortality, most often associated with hemorrhage and infection, limited the use of cesarean delivery until the 20th century, when advances in aseptic, surgical, and anesthetic techniques improved the safety for both mother and baby. Today, cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure performed in the United States, accounting for more than 30% of all births and 1 million procedures each year.2 Globally, the incidence of cesarean delivery has progressively increased; however, the rate varies dramatically by country, ranging from 0.4% to 45.9% (Figure 26-1).3 Maternal, obstetric, fetal, medicolegal, and social factors are largely responsible for this variability, resulting in significant differences in cesarean delivery rates even among individual obstetricians and institutions (Box 26-1).4

Indications

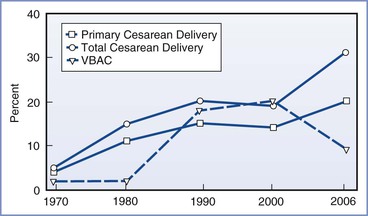

The common indications for cesarean delivery include dystocia, malpresentation, nonreassuring fetal status, and previous cesarean delivery (Box 26-2). An elective cesarean delivery can be performed for obstetric or medical indications or at the request of a pregnant patient, and it is typically planned and performed prior to the onset of labor.5 A cesarean delivery performed during labor for a planned vaginal delivery can also occur for a wide range of maternal and fetal indications but may need to be conducted in an urgent or emergent manner. A prior cesarean delivery does not necessitate cesarean delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. A trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC), which if successful is called a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), is an alternative option; the use of TOLAC, once growing in popularity, has declined in recent years for a variety of reasons (Figure 26-2) (see Chapter 19).

FIGURE 26-2 Rates of primary cesarean delivery, total cesarean delivery, and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC) in the United States, 1970 to 2006. (Data for 1970-1988 from the National Hospital Discharge Survey; data for 1989-2006 from the National Vital Statistics System, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at http://www.cdc.gov.)

Operative Technique

The technical aspects of performing a cesarean delivery are comparable worldwide, with minor variations. A midline vertical abdominal incision allows rapid access and greater surgical exposure; however, the horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incision offers better cosmesis and wound strength. Similarly, a low transverse uterine incision, in comparison with a vertical incision, allows for a lower incidence of uterine dehiscence or rupture in subsequent pregnancies, as well as a reduction in the risks of infection, blood loss, and bowel and omental adhesions. Vertical uterine incisions are most often used in the following situations: (1) when the lower uterine segment is underdeveloped (before 34 weeks’ gestation), (2) in delivery of a preterm infant in a woman who has not labored, and (3) in selected patients with multiple gestation and/or malpresentation. In some cases, a vertical uterine incision is performed high on the anterior uterine wall (i.e., classic incision), especially in the patient with a low-lying anterior placenta previa or when a cesarean hysterectomy is planned.

Uterine exteriorization following delivery facilitates visualization and repair of the uterine incision, particularly when the incision has been extended laterally. Although the effect of exteriorization on blood loss and febrile morbidity remains controversial,6 higher rates of intraoperative nausea, emesis, and venous air embolism as well as postoperative pain have been observed.7,8

Morbidity and Mortality

Complications of cesarean delivery include hemorrhage, infection, thromboembolism, ureteral and bladder injury, abdominal pain, uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies, and death (Box 26-3).9 Nonelective cesarean delivery is associated with a greater risk for maternal morbidity than elective cesarean delivery; a 2008 study of all deliveries in Finland indicated that the rates of severe maternal morbidity were 5.2, 12.1, and 27.2 per 1000 vaginal, elective cesarean, and nonelective cesarean deliveries, respectively.10

Maternal mortality has decreased during the past 75 years (see Chapter 40). Since 1937, when the maternal mortality rate for nulliparous women undergoing cesarean delivery in the United States was 6%, the risk for death associated with the procedure has decreased by a factor of nearly 1000 owing to the availability of blood transfusions, antibiotics, safer anesthetic techniques, and critical care units.11 Maternal morbidity and mortality vary widely from country to country. In most developed nations, the rate of maternal death associated with all cesarean deliveries remains higher than that associated with vaginal deliveries.3,12 The risk for maternal death for a planned, elective primary cesarean delivery may not differ from that associated with a planned vaginal delivery, but performance of cesarean delivery places the mother at higher risk for morbidity (and perhaps mortality) in subsequent pregnancies and cesarean deliveries.13

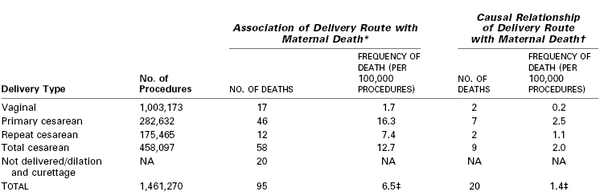

Clark et al.12 identified the causes of maternal death in a retrospective study of 1.5 million deliveries that occurred between 2000 and 2006 within a health care network composed of primary, secondary, and tertiary care hospitals in 20 states (Table 26-1). Only 15% of maternal deaths were related to preexisting medical conditions; most deaths occurred in women classified as being at low risk at the beginning of pregnancy. The investigators concluded that 17 deaths (18%) could have been prevented by provision of more appropriate medical care. (Causality was determined by evaluating whether the maternal death could have been avoided with the use of an alternative route of delivery, with the assumption that all other details remained the same prior to delivery.) The preventable deaths were associated with postpartum hemorrhage (8), preeclampsia (5), medication error (3), and infection (1). Cesarean delivery was determined to be directly responsible for maternal death in four cases, including hemorrhage from surgical vascular injury in three cases and sepsis from surgical injury to the bowel in the fourth. Deaths associated with, but not directly caused by, cesarean delivery were associated with perimortem procedures or caused by thromboembolic phenomena; of the nine patients who died of thromboembolic phenomena, none had received peripartum mechanical or pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. The investigators concluded that cesarean delivery per se was only rarely the causative factor in maternal death; in the majority of cases, death was related to the indication for the cesarean delivery rather than the operative procedure. Nonetheless, these investigators also concluded that the risk for death caused by cesarean delivery is approximately 10 times higher than that for vaginal birth and likely could be reduced with the implementation of universal perioperative thromboprophylaxis (see later discussion).

TABLE 26-1

Relationship between Route of Delivery and Maternal Death

* Association relationships: For vaginal birth versus total cesarean, vaginal birth versus primary cesarean, and vaginal birth versus repeat cesarean, P < .001. For primary cesarean versus repeat cesarean, P = .01.

† Causal relationships: For vaginal birth versus total cesarean and vaginal birth versus primary cesarean, P < .001. For vaginal birth versus repeat cesarean, P = .12. For primary cesarean versus repeat cesarean, P = .50. For vaginal birth versus primary, repeat, and total cesarean delivery, excluding pulmonary embolism deaths preventable with universal prophylaxis, P = .07, P = .38, and P = .08, respectively.

‡ Deaths per 100,000 pregnancies.

NA, not applicable.

Modified from data in Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199:36.e1-5.

Neonatal morbidity, in particular respiratory system morbidity (thus potentially resulting in the anesthesia provider’s involvement in neonatal resuscitation), is greater with elective cesarean delivery than with vaginal delivery.14 Patterns and rates of neonatal mortality are similar to those of maternal mortality; the higher neonatal mortality rates observed after cesarean delivery most likely reflect the conditions that prompt nonelective cesarean delivery.15

Prevention of Cesarean Delivery

Neuraxial labor analgesia was earlier thought to increase the cesarean delivery rate compared with nonmedicated labor or other analgesic techniques; however, randomized controlled trials and sentinel event studies indicate that neuraxial analgesia is not associated with a higher cesarean delivery rate than systemic opioid analgesia (see Chapter 23).16,17 Moreover, the combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique for labor analgesia, despite its association with fetal bradycardia, does not result in an increase in the total cesarean delivery rate.18,19 Some cesarean deliveries may be avoided through the provision of (1) adequate labor analgesia, including analgesia for trial of labor after cesarean delivery and instrumental vaginal delivery; (2) analgesia for external cephalic version (see Chapter 35); and (3) intrauterine resuscitation, including pharmacologic uterine relaxation in cases of uterine tachysystole.

Maternal Labor Analgesia

The National Institutes of Health consensus statement on cesarean delivery on maternal request emphatically concluded that “maternal request for cesarean delivery should not be motivated by unavailability of effective [labor] pain management.”5 It is of concern that a survey of 1300 hospitals indicated that as recently as 2001, 6% to 12% of hospitals in the United States did not provide any form of labor analgesia.20 Although the availability of labor analgesia, especially in the form of neuraxial techniques, has increased during the past three decades,20 there are still institutions, predominantly smaller ones, where cesarean deliveries are likely performed because of nonexistent or inadequate labor analgesia.

Adequate maternal analgesia and perineal relaxation are also important for instrumental (forceps, vacuum) vaginal deliveries. Neuraxial techniques can optimize anesthetic conditions for these obstetric procedures (see Chapter 23).

External Cephalic Version

Singleton breech presentations occur in 3% to 4% of term pregnancies. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists21 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)22 caution against a vaginal breech delivery, given the increased risk for emergency cesarean delivery and neonatal injury. External cephalic version (ECV), a procedure by which manual external pressure is applied to the maternal abdomen to change the fetal presentation from breech to cephalic, remains a viable option. ECV is usually performed between 36 and 39 weeks’ gestation.22

Neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia has been observed to increase the success of an ECV of a fetus with a breech presentation (see Chapter 35). Two recent, independent meta-analyses both concluded that the use of neuraxial blockade resulted in a significant improvement in the ECV success rate.23,24 Both randomized and nonrandomized studies have indicated that the use of neuraxial blockade improves the overall success rate by 13% to 50%. Moreover, in these studies, the use of neuraxial blockade did not appear to compromise maternal and fetal safety, and specifically it did not increase the incidence of fetal bradycardia, placental abruption, or fetal death.

Intrauterine Resuscitation

Evidence of intrapartum fetal compromise (nonreassuring fetal status) should prompt the obstetric team (including obstetric and anesthesia providers and nurses) to attempt intrauterine fetal resuscitation (Box 26-4).

In cases of uterine tachysystole, the administration of nitroglycerin (50 to 100 µg intravenously) may provide rapid onset (40 to 50 seconds) uterine relaxation.25 Higher doses of intravenous nitroglycerin (200 to 500 µg) have been described for uterine relaxation in other settings (e.g., internal podalic version, ECV, uterine prolapse)26; to date, a nitroglycerin dose-response study evaluating uterine tone as well as side effects (e.g., hypotension) has not been performed. Nitroglycerin may also be administered via other routes (e.g., sublingual, topical), but the bioavailability associated with the use of these routes is different and highly variable. For example, three sprays of sublingual nitroglycerin (400 µg/spray) have been used for uterine tocolysis27; however, the bioavailability of nitroglycerin by this route is approximately 38%. Nitroglycerin relaxes the uterus through the production of nitric oxide in uterine smooth muscle.28 Although the use of nitroglycerin has not been uniformly demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the promotion of uterine relaxation,29 a number of reports have indicated its value in cases requiring acute tocolysis.30 Nitroglycerin does not provide total relaxation of the cervix because the majority (85%) of cervical fibers are fibrous in origin.31

Preparation for Anesthesia

The anesthetic management of cesarean delivery may depend in part on the obstetric indications for operative delivery. The anesthesia provider should consider the patient’s medical, surgical, and obstetric history, the presence or absence of labor, the urgency of the delivery, and the resources available in preparing for a cesarean delivery.

Preanesthetic Evaluation

All women admitted for labor and delivery are potential candidates for the emergency administration of anesthesia, and an anesthesia provider ideally should evaluate every woman shortly after admission. Optimally, for high-risk patients, preanesthesia consultation should occur in the late second or early third trimester, even if a vaginal delivery is planned. This practice offers the opportunity to provide patients with information, solicit further consultations, optimize medical conditions, and discuss plans and preparations for the upcoming delivery.32,33 Early communication among the members of the multidisciplinary team is encouraged.34 In some cases, the urgent nature of the situation allows limited time for evaluation before induction of anesthesia and commencement of surgery; nonetheless, essential information must be obtained and risks and benefits of alternative anesthetic management decisions should be considered.

A focused preanesthetic history and physical examination includes (1) a review of maternal health and anesthetic history, relevant obstetric history, allergies, and baseline blood pressure and heart rate measurements; and (2) performance of an airway, heart, and lung examination consistent with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) guidelines (see Appendix B).34,35

Informed Consent

Recognized by the courts as early as the 18th century, the concept of informed medical consent was defined in 1957 as a requirement that the physician explain to the patient the “risks, benefits, and alternatives” of a procedure.36 The ethical issues in obtaining consent from the obstetric patient can be challenging because of the clinical situations encountered, such as (1) the pain and stress of labor; (2) birth plans (in which the patient dictates in advance those interventions that are “acceptable” and “not acceptable”); (3) rapidly changing maternal and fetal status, often requiring emergency care; and (4) fetal considerations, which may involve consideration of extrauterine viability and the definition of independent moral status (i.e., the existence of fetal rights equal to those of the mother). Discussion of this last issue may invoke theological, moral, ethical, and philosophical arguments (see Chapter 33).

Informed consent has the following three elements: threshold, information, and consent (Box 26-5).37

Threshold Elements

Threshold elements include the ability of the patient to meet the basic definition of competence, which refers to the patient’s legal authority to make a decision about her health care. Although some cognitive functions may be compromised by the effects of pain, exhaustion, and analgesic drugs,38 evidence suggests that most laboring women retain the capacity to hear and comprehend information during the consent process.36

Information Elements

The premise that a patient should be informed about the risks of a planned procedure in a language that she understands is the basis for the information elements of the consent process. In part, the difficulty with obtaining informed consent for anesthesia lies in determining the incidence of anesthesia-related morbidity and mortality. Jenkins and Baker39 surveyed the risks associated with anesthesia and compared them with risks inherent in daily living to provide contextual comparisons for patients. The investigators concluded that the perceptions regarding anesthesia risks held by anesthesia providers, surgeons, and the public are somewhat optimistic and that the consent process should include a more realistic and comprehensive disclosure.

A second difficulty is determining what risks require disclosure. White and Baldwin40 stated:

Anesthesia is by nature a practical specialty; every procedure [is] performed carrying a range of risks, which may be minor or major in consequence, common or rare in incidence, causal or incidental to the harm sustained (if any), convenient or inconvenient in timing, expected or unexpected, relative or absolute, operator-dependent or any combination of the above. In addition, there are significant difficulties in communicating risk, caused by patient perceptions, anaesthetist perceptions and the doctor-patient interaction, and complicated by the range of communication methods (numerical, verbal, or descriptive).

A survey conducted among obstetric anesthesia providers in the United Kingdom and Ireland found a consensus that the following neuraxial anesthetic risk factors should be disclosed: (1) the possibility of intraoperative discomfort and a failed/partial blockade, (2) the potential need to convert to general anesthesia, (3) the presence of weak legs, (4) hypotension, and (5) the occurrence of an unintentional dural puncture (with the use of an epidural technique).41 Backache and urinary retention were considered “optional” for discussion, and the risk for paraplegia was considered unworthy of mention unless the patient specifically asked about it.41

Among obstetric patients, the desire for risk disclosure varies. In a study from Australia, Bethune et al.42 reported a significant range (between 1 : 1 and 1 : 1 billion) in the level of risk for complications of epidural analgesia at which pregnant women wished to be informed. In a similar study from the United Kingdom in which the risks associated with general anesthesia were discussed, Jackson et al.43 found that 50% of pregnant women wished to know all risks that occurred at a frequency of greater than 1 : 1000. Overall, pregnant women appear to want more rather than less information regarding the risks of anesthetic interventions.44

Consent Elements

In obtaining consent, care must be taken to preserve patient autonomy by providing information in a noncoercive, nonmanipulative manner (i.e., avoiding a paternalistic or maternalistic approach). Barkham et al.37 observed that there are occasions when noncoercive forms of influence may be appropriate and that reasoned argument can be used to persuade patients of the merits of a particular course of action. For example, a woman with anatomy consistent with a difficult airway who is requesting general anesthesia for an elective cesarean delivery may reconsider her choice after rational persuasion.

In many cases, the course of action most appropriate for maternal health is also beneficial to the fetus. In some cases, however, the best interests of the mother may conflict with those of the fetus. For example, emergency cesarean delivery with general anesthesia is often performed primarily for the benefit of the fetus but may involve higher risk to the mother than a nonemergency procedure performed with neuraxial anesthesia. This conflict in relative risks and benefits will most likely intensify in the future as intrauterine fetal surgery becomes more common.

Informed Refusal

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) is a part of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. The NICE guidelines for cesarean delivery state that “after providing the pregnant woman with evidence-based information and in a manner that respects the woman’s dignity, privacy, views, and culture whilst taking into consideration the clinical situation … a competent pregnant woman is entitled to refuse treatment, even when the treatment would clearly benefit her or her baby’s health. Refusal of treatment needs to be one of the woman’s options.”45 Although compliance with maternal requests is the usual course of action, a court-based decision is sometimes made on behalf of the unborn infant (see Chapter 33).

The anesthesia provider is not obliged to honor a patient’s or obstetrician’s request (e.g., general anesthesia in a morbidly obese patient with a difficult airway), particularly when it conflicts with the clinician’s experience and knowledge of acceptable risks and benefits.46

Overall, anesthesia providers are encouraged to (1) engage in, rather than withhold, a discussion of anesthetic risks; (2) recognize that their own biases may influence the presentation of risks; (3) understand how the perception of risks is modified by the situation; and (4) provide contextual explanation of risks, to help place potential complications in perspective.39 When recognized as an opportunity to foster a closer patient-physician relationship and greater involvement of the patient in her care, rather than simply as a tool to avoid litigation, informed consent can help guide the decision-making associated with anesthesia care.

Blood Products

Peripartum hemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide (see Chapters 38 and 40).47 There is little difference in blood loss between an uncomplicated elective cesarean delivery and an uncomplicated planned vaginal birth48; however, a cesarean delivery performed during labor is associated with greater blood loss.49 Risk factors for peripartum hemorrhage are listed in Box 26-6.

Preparation for obstetric hemorrhage includes (1) reviewing the patient’s history for anemia or risk factors for hemorrhage (e.g., placenta previa, prior uterine surgery, possible placenta accreta); (2) consulting with the obstetric team regarding the presence of risk factors; (3) reviewing reports of ultrasonographic or magnetic resonance images of placentation; (4) obtaining a blood sample for a type and screen or crossmatch; (5) contacting the blood bank to ensure the availability of blood products; (6) obtaining and checking the necessary equipment (blood filters and warmers, infusion pumps and tubing, compatible fluids and medications, and standard clinical laboratory collection tubes [to check hemoglobin, platelets, electrolytes, and coagulation factors]); and (7) consulting with a blood bank pathologist, hematologist, and/or interventional radiologist in selected cases (Box 26-7).

Currently, there is a lack of consensus as to which patients require a blood type and screen and which patients require a crossmatch.34 The maternal history (previous transfusion, existence of known red blood cell antibodies) and anticipated hemorrhagic complications, as well as local institutional policies, should guide decision-making. In certain high-risk cases (e.g., suspected placenta accreta), blood products (i.e., 2 to 4 units of packed red blood cells) should be physically present near or in the operating room before making the surgical incision, if possible.

If an interventional radiologist plans to place prophylactic intravascular balloon occlusion catheters before surgery, and if neuraxial anesthesia is planned, the anesthesia provider should place an epidural catheter prior to placement of the balloon catheters (see later discussion).50

Monitoring

Attention should be given to the availability and proper functioning of equipment and monitors for the provision of anesthesia and the management of potential complications (e.g., failed intubation, cardiopulmonary arrest).34 Equipment should be checked on a daily basis and serviced at recommended intervals. The equipment and facilities available in the labor and delivery operating room suite should be comparable to those available in the main operating room.34

The ASA standards for basic monitoring apply to the provision of anesthesia for all patients.51 Within obstetrics, basic monitoring consists of maternal pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram (ECG), and noninvasive blood pressure monitoring,* as well as fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring.

Automated blood pressure monitors that use oscillometric methods indicate lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures than auscultatory methods between 11% to 22% of the time in normotensive pregnant women.53 Forearm, wrist, and finger blood pressure monitors have been developed but have not yet undergone adequate validation. In general, blood pressure measurements at locations distal to the heart tend to reflect higher systolic and lower diastolic blood pressures, respectively, relative to central aortic pressure.52 Invasive hemodynamic monitoring should be considered in women with severe cardiac disease, refractory hypertension or hypotension, pulmonary edema, or unexplained oliguria.

ECG abnormalities are often observed in late pregnancy and are believed to be due to hyperdynamic circulation, circulating catecholamines, and/or altered estrogen and progesterone concentration ratios (see Chapter 2). During cesarean delivery with neuraxial anesthesia, ECG changes have a reported incidence of 25% to 60%54,55; in this setting, administration of droperidol, ondansetron, and oxytocin may be associated with prolongation of the QTc interval,56,57 and oxytocin administration may be associated with ST-segment depression.58 The significance of these ECG findings as an indicator of cardiac pathology remains controversial, because only a small minority of parturients experience myocardial ischemia as measured by elevated serum cardiac troponin levels.59 The placement of five ECG leads improves the sensitivity of detecting ischemic events; combining leads II, V4, and V5 resulted in a sensitivity of 96% in detecting ST-segment changes in a nonobstetric population.60 In a prospective study of 254 healthy women undergoing cesarean delivery with spinal anesthesia, Shen et al.61 determined the incidence of first- and second-degree atrioventricular block (3.5% for each), severe bradycardia (< 50 beats/min; 6.7%), and multiple premature ventricular contractions (1.2%). The investigators speculated that a relative increase in parasympathetic activity occurred as a result of spinal blockade of cardiac sympathetic activity. Most of the dysrhythmias were transient and resolved spontaneously.

Monitors that process the electroencephalogram to indicate the depth of anesthesia have received only limited evaluation in women undergoing cesarean delivery.62 Whether routine use of these monitors can reduce the incidence of intraoperative awareness during general anesthesia for cesarean delivery is unclear (see later discussion).

An indwelling urinary catheter is used in almost all women undergoing cesarean delivery.63 A urinary catheter helps avoid overdistention of the bladder during and after surgery. In cases associated with hypovolemia and/or oliguria, or anticipated significant blood loss, a collection system that allows precise measurement of urine volume is helpful.

An evaluation of the FHR tracing by a qualified individual may be useful before and after administration of anesthesia.34 Whether FHR evaluation should be performed before every cesarean delivery is controversial. The ACOG64 has stated that the decision to monitor the fetus either by electronic FHR monitoring or by ultrasonography before a scheduled (elective) cesarean delivery should be individualized, because data are insufficient to determine the value of FHR monitoring before elective cesarean delivery in patients without risk factors. In contrast, the National Collaboration Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health in the United Kingdom has stated that the FHR should be monitored during the initiation of the neuraxial technique and until the abdominal skin preparation for cesarean delivery has begun.45

In most cases of emergency cesarean delivery, a previously placed fetal scalp (or buttock) ECG electrode can be used to monitor the FHR before, during, and after the initiation of anesthesia. Typically, the fetal scalp electrode is removed when the surgical drapes are applied to the abdomen, but in some cases the scalp electrode may be left in place until just before delivery, when the circulating nurse reaches under the drapes to disconnect the electrode.

In cases of emergency cesarean delivery, continuous FHR monitoring is useful for at least three reasons. First, the FHR abnormality often resolves; in some cases, the obstetrician will then elect to forgo the performance of a cesarean delivery. In other cases, the obstetrician may continue with plans to perform a cesarean delivery but continuous FHR monitoring may facilitate the administration of neuraxial anesthesia. For example, an improved FHR tracing allows time for extension of adequate epidural anesthesia or administration of spinal anesthesia. Second, continuous FHR monitoring may guide management in cases of failed tracheal intubation. If intubation fails and there is no evidence of fetal compromise, both the anesthesia provider and the obstetrician will have greater confidence in a decision to awaken the patient and proceed with an alternative anesthetic technique. By contrast, if there is evidence of ongoing fetal compromise, the anesthesia provider may decide to provide general anesthesia by means of a face mask or supraglottic airway (e.g., laryngeal mask airway [LMA]), and the obstetrician may proceed with cesarean delivery (see Chapter 30). Third, intraoperative FHR monitoring allows the obstetrician to modify the surgical technique according to the urgency of delivery.

Medication Availability and Storage

The drugs used for the provision of general and neuraxial anesthesia, including vasopressors and emergency medications, should be readily available. The Joint Commission65 mandates that all medications should be secured. Currently, only Schedule II controlled substances as classified by the Drug Enforcement Agency66 need to be secured in a “substantially constructed locked cabinet.”67 Other drugs and products, including anesthetic medications, should be “reasonably secure” but not necessarily locked. These drugs include the Schedule III drug thiopental, as well as succinylcholine and vasopressor agents. The Joint Commission has defined “reasonably secure” as storage in areas not readily accessible or easily removed by the public. Federal law requires that all hospitals receiving Medicare funding adhere to conditions of participation, which state that “drugs and biologicals must be kept in a secure area, and locked when appropriate.”67 This rule applies to noncontrolled substances.

Equipment

Labor and delivery units may be adjacent to or remote from the operating rooms. In some facilities, the unit is located on a separate floor but shares a common operating room facility (used for other surgical procedures), whereas in others it is a geographically separate, self-contained unit with its own operating room facilities. Regardless of location, the equipment, facilities, and support personnel available in the labor and delivery operating room should be comparable to those available in the main operating room.34 In addition, personnel and equipment should be available to care for obstetric patients recovering from major neuraxial or general anesthesia.

Resources for the conduct and support of neuraxial anesthesia and general anesthesia should include those necessary for the basic delivery of anesthesia and airway management as well as those required to manage complications (e.g., failed tracheal intubation). The immediate availability of these resources is particularly important, given the frequency and urgency of anesthesia care. Consideration should be given to having some of the equipment and supplies immediately available in one location or in a cart (e.g., difficult airway cart, massive hemorrhage cart, malignant hyperthermia box) specifically located on the labor and delivery unit. Equipment and supplies should be checked on a frequent and regular basis. Securing special-situation equipment and supplies in a cart with a single-use breakthrough plastic tie helps ensure that the cart is kept in a fully stocked state.

Aspiration Prophylaxis

The patient should be asked about oral intake, although insufficient evidence exists regarding the relationship between recent ingestion and subsequent aspiration pneumonitis (see Chapter 29). Gastric emptying of clear liquids during pregnancy occurs relatively quickly; the residual content of the stomach (as measured by the cross-sectional area of the gastric antrum 60 minutes after the ingestion of 300 mL of water) does not appear to be different from baseline fasting levels in either lean or obese nonlaboring pregnant women.68,69 Moreover, when measured by serial gastric ultrasonographic examinations and acetaminophen absorption, the gastric emptying half-time of 300 mL of water is shorter than that of 50 mL of water in healthy, nonlaboring, nonobese pregnant women (24 ± 6 versus 33 ± 8 minutes, respectively).68

The healthy patient undergoing elective cesarean delivery may drink modest amounts of clear liquids up to 2 hours before induction of anesthesia.34 Examples of clear liquids are water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, black coffee, and sports drinks. The volume of liquid ingested is less important than the absence of particulate matter. Patients with additional risk factors for aspiration (e.g., morbid obesity, diabetes, difficult airway) or laboring patients at increased risk for cesarean delivery (e.g., nonreassuring FHR pattern) may have further restrictions of oral intake, determined on a case-by-case basis.34

Ingestion of solid foods should be avoided in laboring patients and patients undergoing elective surgery (e.g., scheduled cesarean delivery or postpartum tubal ligation). A fasting period for solids of 6 to 8 hours, depending on the fat content of the food, has been recommended.34

A reduction in gastric content acidity and volume is believed to decrease the risk for damage to the respiratory epithelium if aspiration should occur. Oral administration of a nonparticulate antacid (0.3 M sodium citrate, pH 8.4) causes the mean gastric pH to increase to greater than 6 for 1 hour; it does not affect gastric volume.70,71 H2-receptor antagonists (ranitidine, famotidine), proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole), and metoclopramide reduce gastric acid secretion and volume but require at least 30 to 40 minutes to exert their effects.72 In a systematic review of interventions used to reduce the risk for aspiration pneumonitis in women undergoing cesarean delivery, Paranjothy et al.73 found a significant reduction in the risk for gastric pH less than 2.5 with antacids (relative risk [RR], 0.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09 to 0.32), H2-receptor antagonists (RR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.18), and proton-pump antagonists (RR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.46), compared with no treatment or placebo. The combined use of an antacid and an H2-receptor antagonist was found to be more effective in reducing pH less than 2.5 than administration of placebo or an antacid alone.73 Sodium citrate was associated with a higher incidence and severity of nausea than an H2-receptor antagonist (famotidine).74 Metoclopramide is a promotility agent that hastens gastric emptying, increases lower esophageal sphincter tone, and decreases nausea and vomiting.75,76 Prior to surgical procedures, the timely administration of a nonparticulate antacid, an H2-receptor antagonist, and metoclopramide should be considered, especially for nonelective procedures.34

Prophylactic Antibiotics

With both elective (nonlaboring) and nonelective (laboring) cesarean deliveries, a 60% decrease in the incidence of endometritis, a 25% to 65% decrease in the incidence of wound infection, and fewer episodes of fever and urinary tract infections have been demonstrated after prophylactic antibiotic administration.77 The ACOG78 has recommended the prophylactic administration of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic, such as a first-generation cephalosporin, within 1 hour of the start of cesarean delivery.

Antibiotics with efficacy against gram-positive, gram-negative, and some anaerobic bacteria are commonly used for prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Appropriate coverage includes intravenous ampicillin 2 g, cefazolin 1 g, or ceftriaxone 1 g. Appropriate antibiotic coverage should last for 3 to 4 hours; therefore, ampicillin may be less appropriate owing to a shorter half-life.78,79 In parturients with a significant allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g., history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria), intravenous clindamycin with gentamicin is a reasonable alternative.

Because of the greater volume of distribution, higher doses of antibiotics should be considered in women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2 or an absolute weight greater than 100 kg.78,80 After administration of cephazolin 2 g, Pevzner et al.80 observed that the minimum inhibitory tissue concentration for gram-negative rods was not achieved at the time of skin incision or closure in 20% of obese women and 33% of morbidly obese women.

The optimal timing of antibiotic administration (before skin incision versus after clamping of the umbilical cord) and the potential value of more broad-spectrum antibiotics remain controversial. In the past, prophylactic antibiotics typically have been administered after umbilical cord clamping, because of concern that fetal antibiotic exposure might mask a nascent infection and/or increase the likelihood of a neonatal sepsis evaluation. However, in a meta-analysis, Costantine et al.81 concluded that pre-incision antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the incidence of postcesarean endometritis and total maternal infectious morbidity, without evidence of adverse neonatal effects. Although earlier studies suggested that ampicillin and first-generation cephalosporins are similar in efficacy to more broad-spectrum agents,77 more recent trials have suggested that there is benefit associated with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis that includes the addition of an agent that covers other organisms such as Ureaplasma.79,82 Further investigation is necessary to determine whether more broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotic coverage improves maternal and fetal outcomes in mothers with active or presumed infection (e.g., chorioamnionitis).

Aseptic Technique

In the early 19th century, Ignác Semmelweis observed that puerperal fever, known as “childbed fever,” was most likely transmitted when the first stage of labor was prolonged and multiple individuals performed vaginal examinations with contaminated hands. Since that time, the practice of hand hygiene has caused a significant reduction in maternal and neonatal infectious morbidity.

Epidural abscess and meningitis have been reported as complications of neuraxial procedures in obstetric patients (see Chapter 32). These cases have prompted questions regarding the best antiseptic solution for disinfecting the skin,83 provider attire, and the appropriate dressing for the neuraxial catheter insertion site (see Chapters 12 and 32). There is wide variation in aseptic practices. Regrettably, some anesthesia providers do not wear a face mask, whereas others wear a gown, face mask, and hat.84 “Rapid-sequence spinal” has been described for cases of emergency cesarean delivery in which the use of draping is omitted and a single-wipe skin preparation is used85; however, many obstetric anesthesia providers would argue that this practice is unwise.

Subtle changes in circulating immunoglobulin levels induced by pregnancy may affect the risk associated with exposure to infectious pathogens.86 As a consequence, obstetric anesthesia providers should always give careful attention to aseptic technique, especially during performance of a neuraxial technique. Proper sterile technique consists of wearing a face mask, giving careful attention to hand hygiene, and donning sterile gloves before initiating neuraxial blockade.87

Attention should also be given to the careful preparation of anesthetic drugs during administration of either general or neuraxial anesthesia. Although many local anesthetics have bactericidal properties that appear concentration dependent,88 propofol and other anesthetic agents can support bacterial growth.89 An increasing number of institutions are using premixed solutions of local anesthetic and opioid (prepared under aseptic conditions in a hospital or compounding pharmacy) to limit breaches in aseptic technique during the administration of neuraxial anesthesia.

Intravenous Access and Fluid Management

The establishment of functional intravenous access is of critical importance to the successful outcome of many clinical situations in obstetric anesthesia practice. According to the Hagen-Poiseuille equation, the infusion rate of fluid through a catheter is directly related to the pressure gradient of the fluid and the fourth power of the catheter’s radius, and inversely related to the viscosity of the fluid and the catheter’s length. Because the size of the catheter, more than the size of the vein, dictates the flow rate, the use of a short, large-diameter catheter (e.g., 16- or 18-gauge) is associated with the best flow.90

In general, a smaller but functional catheter is more important than a larger catheter that is unreliable or requires frequent manipulation. Smaller catheters may be acceptable in an emergency; volume and blood resuscitation can be satisfactorily achieved using 20- and 22-gauge catheters (without evidence of greater red blood cell destruction) with the use of dilution, pressurization, or both.91 However, when large-bore peripheral venous access is problematic, especially when large blood loss is anticipated, or administration of multiple blood products is required, the anesthesia provider may choose to insert a central venous catheter.

Although the administration of intravenous fluids may decrease the incidence of neuraxial anesthesia–associated hypotension, initiation of anesthesia should not be delayed to administer a fixed volume of fluid,34 particularly in the case of an emergency cesarean delivery, in which the life and health of the mother and the infant are best preserved with timely delivery. Vasopressors can be used for both prophylaxis and treatment of hypotension. The type of fluid (crystalloid, colloid) and the volume, rate, and timing of administration are relevant factors in the prevention and treatment of hypotension.92,93 In most situations, a balanced salt solution such as lactated Ringer’s solution is acceptable. Blood products are most often administered with normal saline. Crystalloid or colloid solutions that contain calcium or glucose should not be administered with blood products, owing to the risks for clotting (due to reversal of the citrate anticoagulant) and clumping of red blood cells, respectively.

Traditionally, approximately 1 L of crystalloid solution has been administered intravenously (as “prehydration” or “preload”) to prevent or reduce the incidence and severity of hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery. However, prehydration, even with large volumes (30 mL/kg), is minimally effective in preventing neuraxial anesthesia–induced hypotension. Although an initial study found that administering crystalloid solution at the time of the intrathecal injection (“co-load”) was more efficacious than prehydration in preventing hypotension,94 later studies did not support this finding,95 likely because the infusion rate was too slow.93 Colloid, administered before or at the time of the intrathecal injection, is more effective than crystalloid for preventing hypotension.96 Colloid administered before the intrathecal injection (preload) is equally efficacious to administration at the time of injection (co-load).95

In healthy patients, we rapidly administer approximately 1 L of crystalloid at the time of initiation of neuraxial anesthesia. For patients at high risk for hypotension or the consequences of hypotension, colloid may be administered before or at the time of initiation of neuroblockade.93 Hypotension despite fluid administration is treated with vasopressors (see later discussion).

Supplemental Medications for Anxiety

The administration of benzodiazepines, even low doses (e.g., midazolam 0.02 mg/kg), may result in amnesia97,98; as a consequence, benzodiazepines are typically avoided during awake cesarean delivery. However, on occasion, particularly in women with severe anxiety or undergoing an emergency cesarean delivery, the use of low doses of intravenous midazolam or an opioid may facilitate performance of a neuraxial technique, awake tracheal intubation, or the induction of general anesthesia. Anxiolytics may also assist in mitigating the feelings of distress during the birthing experience, which may lessen the risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder.99 The use of low doses of sedative or anxiolytic agents has minimal to no neonatal effects. Frölich et al.100 observed no differences in neonatal Apgar scores, neurobehavioral scores, or oxygen saturation among women who were randomized to receive either intravenous midazolam (0.02 mg/kg) and fentanyl (1 µg/kg) or saline before administration of spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery.

Positioning

After 20 weeks’ gestation, all pregnant women should be positioned with left uterine displacement to minimize aortocaval compression. The supine hypotension syndrome, which is caused by compression of the aorta and inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus, can manifest as pallor, tachycardia, sweating, nausea, hypotension, and dizziness.101,102 Uteroplacental blood flow is compromised by decreased venous return and cardiac output, increased uterine venous pressure, and compression of the aorta or common iliac arteries.103

The full lateral position minimizes aortocaval compression but does not allow performance of cesarean delivery. In an editorial, Kinsella104 concluded that 15 degrees of left lateral tilt (left uterine displacement) significantly reduces the adverse hemodynamic consequences of the supine position, although both the aorta and inferior vena cava may remain partially compressed. However, most anesthesia providers underestimate the degree of lateral tilt. In a systematic review, Cluver et. al.105 observed no differences in maternal and early neonatal outcomes among various maternal positions for cesarean delivery, but acknowledged that the small sample size in their study was a serious shortcoming that limited the applicability of their observations. They also acknowledged that the effect of maternal position may vary with different clinical situations and that aortocaval compression may be more problematic in women with multiple gestation, fetal macrosomia, or polyhydramnios.105 Anesthesia providers should recognize that (1) individual susceptibility to aortocaval compression varies,106 (2) visual estimates of lateral tilt may be in error,107 and (3) in symptomatic women, increasing the extent of left uterine displacement may be beneficial. Lateral tilt should be used in all women in mid to late pregnancy after the administration of neuraxial or general anesthesia, with greater tilt used when feasible if aortocaval compression is suspected as the cause for maternal or fetal compromise.108

The use of a slight (10 degrees) head-up position may help reduce the incidence of hypotension after initiation of hyperbaric spinal anesthesia.109 The use of a more significant head-up position (30 degrees) has been observed to significantly increase functional residual capacity in parturients compared with the supine position, with the effect diminishing with increasing BMI.110 In morbidly obese patients receiving general anesthesia, the 30-degree head-up position may be particularly useful to improve preoxygenation, denitrogenation, and the view of the glottis during direct laryngoscopy111; this can be accomplished with blankets or commercially available devices (see Chapters 30 and 50). If blankets are used to create the ramp position, they should be stacked rather than interlaced, to allow for rapid readjustment of the head and neck position if necessary. Ideal positioning leads to the horizontal alignment between the external auditory meatus and the sternal notch; this position (1) aligns the oral, pharyngeal, and tracheal axes (“sniffing position”) and (2) facilitates insertion of the laryngoscope blade (see Chapter 30).112

Theoretically, the Trendelenburg (head-down) position may augment venous return and increase cardiac output. The value of this approach in preventing hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia has been questioned.105 After the initiation of hyperbaric spinal anesthesia, the Trendelenburg position has been reported to result in more cephalad spread of anesthesia in one study113 but not in others.114,115 However, this position had no effect on the incidence of hypotension after administration of hyperbaric spinal anesthesia.113,115

The optimal patient position for insertion of a neuraxial needle (or catheter) may depend on clinical circumstances and the preferences and skills of the anesthesia provider. Whether the use of the lateral or the sitting position is best for routine initiation of neuraxial anesthesia is controversial.116,117 Advocates of the lateral position cite a reduction of vagal reflexes, which can result in dizziness, diaphoresis, pallor, bradycardia, and hypotension.118 Moreover, the lateral position may allow better uteroplacental blood flow than the sitting position. Using technetium Tc 99m–radiolabeled isotopes in pregnant women in the third trimester, Suonio et al.119 observed a 23% reduction in uteroplacental blood flow when pregnant patients moved from the left lateral recumbent to the sitting position. In contrast, Andrews et al.120 observed a greater decrease in cardiac output in parturients placed in the left lateral position than in those in the sitting position during initiation of epidural analgesia. Using substernal Doppler ultrasonography, Armstrong et al.121 observed that maternal cardiac index, stroke volume index, heart rate, and systolic blood pressure were higher by approximately 8% in the right or left lateral positions than in the sitting or supine positions; however, there were no significant differences among positions in fetal heart rate, pulsatility index, or resistivity index.

Some parturients find the lateral position more comfortable during administration of neuraxial anesthesia122; this position may also limit side-to-side and front-to-back patient motion during needle insertion. Moreover, because uterine compression of the vena cava diverts blood into the epidural venous plexus,123 the use of the lateral position can reduce hydrostatic pressure and return the engorged epidural venous plexus to its size in the nonpregnant state.124 Bahar et al.125,126 observed that fewer needle/catheter replacements occurred for needle- or catheter-induced venous trauma when epidural procedures were performed in the lateral recumbent head-down position than in either the sitting or the lateral recumbent horizontal position in both obese and nonobese parturients.

The lateral position may also be of value during epidural needle placement because it minimizes the prominence of the dural sac. On the other hand, a bulging dural sac might be preferable during administration of spinal or CSE anesthesia. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography studies have indicated that the cross-sectional area and the anteroposterior diameter of the dural sac at the level of the L3-L4, L4-L5, and L5-S1 interspaces are significantly influenced by posture.127 Lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure is lower and dural sac cross-sectional area smaller in the recumbent position than in the upright position.127 Bulging of the lumbar dural sac—particularly in the sitting position—may decrease the force required to create a dural puncture with a Tuohy epidural needle, but this possibility is unproven.

In a randomized controlled trial, Yun et al.128 observed that the severity and duration of hypotension were greater in women randomly assigned to receive CSE anesthesia (hyperbaric spinal bupivacaine with fentanyl) in the sitting position than in those in the lateral position, despite no differences in the level of sensory blockade.

The sitting position may offer some advantages (e.g., physical landmark recognition in obese parturients, practitioner preference).117 However, anesthesia providers should be facile with the placement of needles for neuraxial techniques in both the sitting and lateral positions, because the sitting position should not be used in some situations (e.g., fetal head entrapment, umbilical cord prolapse, footling breech presentation).116

Supplemental Oxygen

The routine administration of supplemental oxygen during elective cesarean delivery with neuraxial anesthesia has been a common practice since publication of the seminal report by Fox and Houle129; their report demonstrated improved oxygenation, better umbilical cord blood acid-base measurements, and less time to sustained respiration in the neonate, when mothers undergoing cesarean delivery with neuraxial anesthesia breathed 100% oxygen instead of air for at least 10 minutes. However, later evidence suggested that routine oxygen administration may be unnecessary and ineffective130 and may even be detrimental.131 The use of a fractional inspired concentration of oxygen (FIO2) of 0.35 to 0.4 (which cannot be obtained by a nasal cannula or a simple face mask with a flow rate less than 6 L/min132) does not improve fetal oxygenation during labor or elective cesarean delivery. Although respiratory function can deteriorate in parturients receiving neuraxial anesthesia,133,134 maternal or fetal hypoxemia does not normally occur when parturients breathe room air.134 An FIO2 of 0.6 in nonlaboring women undergoing elective cesarean delivery with spinal anesthesia increases the umbilical venous oxygen content by only 12%; an increase in oxygen content is not observed when the uterine incision-to-delivery (U-D) interval exceeds 180 seconds.135

Supplemental oxygen has both beneficial and detrimental effects. Through normal biologic processes, oxygen is converted to reactive oxygen species, including free radicals. The reactive oxygen species cause lipid peroxidation, alteration of cellular enzymatic functions, and destruction of genetic material136; these adverse effects occur with the restoration of perfusion after a period of ischemia (i.e., ischemia-reperfusion injury), including intermittent umbilical cord occlusion and perhaps during uterine contractions.137 Reactive oxygen species are present during hyperoxia (causing such disorders as neonatal retinopathy and bronchopulmonary dysplasia) and in the setting of prolonged labor, oligohydramnios, intermittent umbilical cord compression, and/or fetal compromise.137,138 Hyperoxia in these settings (i.e., during the period of reperfusion following ischemia) results in a higher level of lipid peroxidation.131,138

Term (but not preterm) fetuses may be able to withstand the adverse effects of these reactive oxygen species through a compensatory increase in antioxidants during labor.139,140 Antioxidants, the defense against reactive oxygen species, consist of enzymatic inactivators (superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase) and scavengers (ascorbate, glutathione, transferrin, lactoferrin, ceruloplasmin). The activity of these compensatory mechanisms and their relationships to gestational age and labor suggest that the highest risk for ischemia-reperfusion injury occurs in preterm fetuses before the onset of labor.131,140

The use of a very high FIO2 improves oxygen delivery to hypoxic fetuses for a limited period (approximately 10 minutes); beyond this time, continued hyperoxia, especially in the setting of restored perfusion, increases reactive oxygen species, placental vasoconstriction, and fetal acidosis.141,142 A lower FIO2 may be of benefit in some situations. When asphyxiated infants are immediately resuscitated at birth with air instead of 100% oxygen, better short-term outcomes have been observed143,144; this finding may be a result of the shift in the balance between beneficial oxygenation and detrimental free radicals.

In summary, no significant improvement in maternal-fetal oxygen transfer occurs until very high levels of maternal FIO2 are used. At these levels, the resulting hyperoxia creates reactive oxygen species. Preterm fetuses in nonlaboring mothers are the population at highest risk for hyperoxia-induced injury. Nonetheless, the emergency cesarean delivery of the compromised fetus should include maternal administration of a high FIO2. The greater maternal oxygen consumption and reduced fetal oxygen delivery associated with uterine contractions may exacerbate the fetal compromise; in these situations, supplemental oxygen may augment fetal oxygenation and, perhaps, reduce the severity of fetal hypoxia. However, diminishing fetal benefit appears to occur after 10 minutes.

All women who are at risk for requiring general anesthesia for emergency cesarean delivery should receive an FIO2 of 1.0 after transfer to the operating table. Denitrogenation should always be performed; if it is not performed, the mother is at risk for hypoxemia during apnea before intubation, in turn putting the fetus at risk. When general anesthesia is administered in a patient with fetal compromise, the mother should receive an FIO2 of 1.0 before and immediately after induction of anesthesia, even though the subsequent increases in umbilical venous and arterial oxygen content are not dramatic.

The value of supplemental maternal oxygen during elective cesarean delivery of a noncompromised fetus is questionable. The only reason some obstetric anesthesia providers place nasal cannulae in patients undergoing elective cesarean delivery with neuraxial anesthesia is to facilitate the monitoring of expired carbon dioxide (to monitor the parturient’s ventilation).

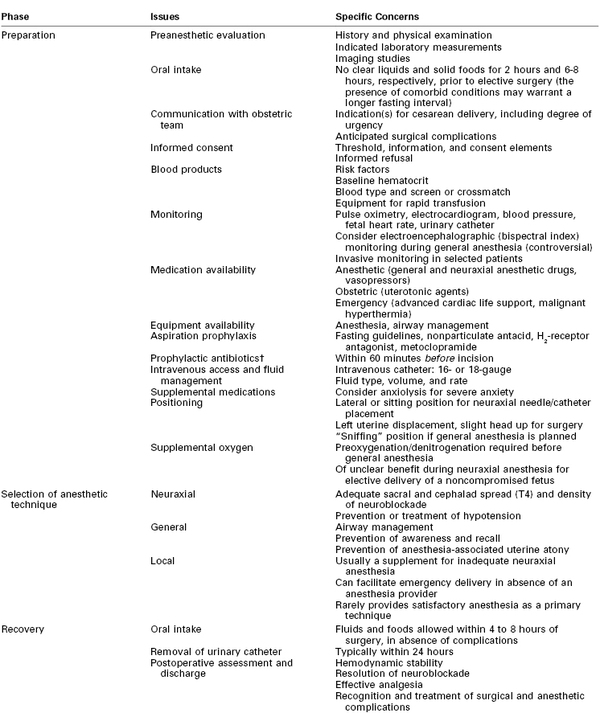

Anesthetic Technique

Providing anesthesia to the parturient is a dynamic, multistep process (Table 26-2). The most appropriate anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery depends on maternal, fetal, and obstetric factors (Table 26-3). The urgency and anticipated duration of the operation play an important role in the selection of an anesthetic technique.

TABLE 26-2

Provision of Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery*

* Procedures, techniques, and drugs may need to be modified for individual patients and circumstances.

† Evidence now suggests that administration of prophylactic antibiotics before incision (rather than after cord clamping) reduces the incidence of postcesarean endometritis and total maternal infectious morbidity.78

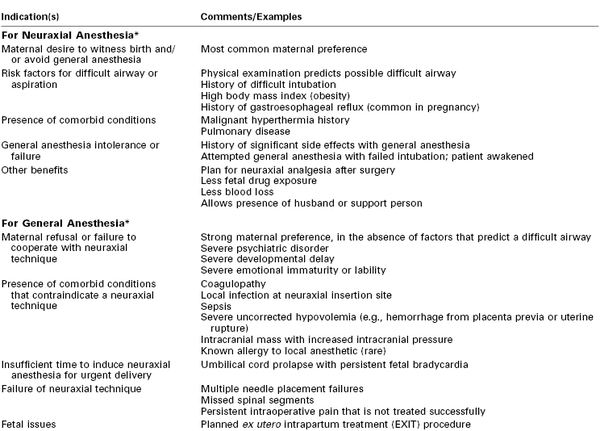

TABLE 26-3

Selection of Anesthetic Technique for Cesarean Delivery

* Many indications for or contraindications to specific anesthesia techniques are relative, and the choice of anesthetic must be tailored to individual circumstances.

In cases of dire fetal compromise, the anesthesia provider may need to perform a preanesthetic evaluation simultaneously with other tasks (i.e., establishing intravenous access and placing a blood pressure cuff, pulse oximeter probe, and ECG electrodes). Regardless of the urgency, the anesthesia provider should not compromise maternal safety by failing to obtain critical information about previous medical and anesthetic history, allergies, and the airway. Effective communication with the obstetric team is critical to establish the degree of urgency, which helps guide decisions regarding anesthetic management. Further, contemporary standards for patient safety require that all members of the surgical team participate in a pre–cesarean delivery “time-out” to verify (1) the correct patient identity, position, and operative site; (2) agreement on the procedure to be performed; and (3) the availability of special equipment, if needed.

In cases of emergency cesarean delivery, the emotional needs of the infant’s mother and father are also important. Parental distress commonly occurs in this setting, and the anesthesia provider is often the best person to give reassurance. All members of the obstetric care team should remember that chaos does not need to accompany urgency.

Neuraxial versus General Anesthesia

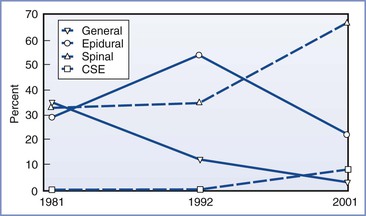

Overall, neuraxial (epidural, spinal, CSE) techniques are the preferred method of providing anesthesia for cesarean delivery; specific benefits and risks of each technique dictate the eventual choice. In contemporary practice, neuraxial anesthesia is administered to some patients who would have received general anesthesia in the past. Umbilical cord prolapse, placenta previa, and severe preeclampsia are no longer considered absolute indications for general anesthesia. For example, in some cases a prolapsed umbilical cord can be decompressed, and if fetal status is reassuring, a neuraxial technique can be used. In an analysis of obstetric anesthesia trends in the United States between 1981 and 2001, a progressive increase was noted in the use of neuraxial anesthesia, especially spinal anesthesia, for both elective and emergency cesarean deliveries (Figure 26-3).20 Neuraxial anesthesia has been used for more than 80% of cesarean deliveries since 1992. Similar increases have occurred in the United Kingdom and in other developed as well as developing countries.145,146

FIGURE 26-3 Rates of use of different anesthesia types for cesarean delivery in the United States. Data from random sample of hospitals in the United States stratified by geographic region and number of births per year. Data shown represent hospitals in stratum I (> 1500 births/yr) and are presented as percentages of cesarean births by anesthesia type. CSE, combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Data from 2001 represent anesthetic technique selected for elective cesarean delivery. (Data modified from Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA. Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update. Anesthesiology 2005; 103:645-53.)

The greater use of neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery has been attributed to several factors, including (1) the growing use of epidural techniques for labor analgesia, (2) an awareness of the possibility that an in situ epidural catheter (even if not used during labor) may decrease the necessity for general anesthesia in an urgent situation, (3) improvement in the quality of neuraxial anesthesia with the addition of an opioid to the local anesthetic, (4) appreciation of the risks of airway complications during general anesthesia in parturients, (5) the desire for limited neonatal drug transfer, and (6) the ability of the mother to remain awake to experience childbirth and to have a support person present in the operating room. Spinal anesthesia is considered an appropriate technique even in the most urgent settings; in a tertiary care institution with an average of 9500 cesarean deliveries annually, neuraxial anesthesia was used in more than 99% of cesarean deliveries over a 6-year period.147 In the setting of a category 1 (immediate threat to life of woman or fetus) cesarean delivery, Kinsella et al.85 described a “rapid-sequence spinal” technique, by which skin preparation, spinal drug combinations, and the spinal technique were simplified; the median time from positioning until satisfactory neuroblockade was 8 minutes (interquartile range [IQR] 7 to 8 [range 6 to 8]). In an analysis of category 4 (elective) cesarean deliveries in a Pakistani hospital, the mean (± SD) elapsed times from initiation to completion of induction of anesthesia were 4.5 ± 1.4 minutes versus 8.1 ± 3.8 minutes for general and spinal anesthesia, respectively.148

Maternal mortality following general anesthesia has been a primary motivator for the transition toward greater use of neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Hawkins et al.149 compared the anesthesia-related maternal mortality rate from 1979 to 1984 with that for the period from 1985 to 1990 in the United States. The estimated case-fatality risk ratio for general versus neuraxial anesthesia was as high as 16.7 in the years 1985 to 1990; however, a similar analysis by the same group of investigators found a nonsignificant risk ratio of 1.7 in the years 1991 to 2002.150 Of interest, these data may overstate the relative risk of general anesthesia, because this form of anesthesia is used principally when neuraxial anesthetic techniques are contraindicated for medical reasons or time constraints147,151; these data also suggest that the relative risk associated with neuraxial anesthesia has increased. However, this change may reflect the growing acceptance of performing neuraxial techniques in parturients with significant comorbidities (e.g., obesity, severe preeclampsia, cardiac disease).

Maternal morbidity is also lower with the use of neuraxial anesthetic techniques than with general anesthesia. In a systematic review of randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials comparing major maternal and neonatal outcomes with the use of neuraxial anesthesia and general anesthesia for cesarean delivery, Afolabi et al.152 found less maternal blood loss and shivering but more nausea in the neuraxial anesthesia group. The intraoperative “perception” of pain was greater in the neuraxial group, but the time elapsed before the first postoperative request for analgesia was longer. Prospective audits of post–cesarean delivery outcomes have indicated that in the first postoperative week, patients who received neuraxial anesthesia had less pain, gastrointestinal stasis, coughing, fever, and depression and were able to breast-feed and ambulate more quickly than patients who received general anesthesia.153

Neonatal outcomes associated with maternal anesthetic selection require further study. Apgar and neonatal neurobehavioral scores are relatively insensitive measures of neonatal well-being, and umbilical cord blood gas and pH measurements may reflect the reason for the cesarean delivery rather than differences in the effect of the anesthetic technique on fetal/neonatal well-being. In a meta-analysis, lower umbilical cord blood pH measurements were associated with spinal, but not epidural, anesthesia compared with general anesthesia.154 However, the study included both randomized and nonrandomized trials and both elective and nonelective procedures, and most trials were conducted in an era when ephedrine was used to support maternal blood pressure (see later discussion). In a systematic review of randomized trials in which the indication for cesarean delivery was not urgent, no differences in umbilical cord arterial blood pH measurements were found among general and neuraxial anesthetic techniques.152

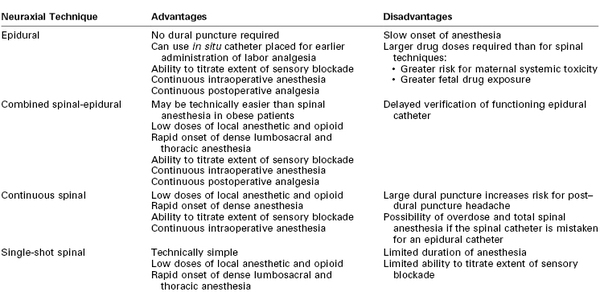

Overview of Neuraxial Anesthetic Techniques

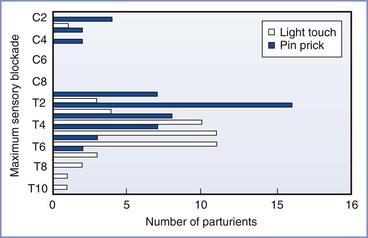

Table 26-4 outlines the advantages and disadvantages of the various neuraxial anesthetic techniques for cesarean delivery. With all neuraxial techniques, an adequate sensory level of anesthesia is necessary to minimize maternal pain and avoid the urgent need for administration of general anesthesia. Because motor nerve fibers are typically larger and more difficult to block, the complete absence of hip flexion and ankle dorsiflexion most likely indicates that a functional sensory and sympathetic block is also present in a similar (primarily lumbosacral) distribution. However, because afferent nerves innervating abdominal and pelvic organs accompany sympathetic fibers that ascend and descend in the sympathetic trunk (T5 to L1), a sensory block that extends rostrally from the sacral dermatomes to T4 should be the goal for cesarean delivery anesthesia.

The manner in which the level of sensory blockade is assessed has implications for the success of a neuraxial technique. The different methods of assessing the extent of sensory blockade (i.e., sensation to light touch, pinprick, cold) may indicate levels of blockade that differ by several spinal segments. Russell155 prospectively demonstrated differential neuraxial blockade in women undergoing cesarean delivery; pinprick evaluation identified a dermatomal level of blockade that was several segments more cephalad than that identified by light touch. A subsequent study of spinal anesthesia in parturients undergoing cesarean delivery indicated that although sensory blockade to light touch differed from sensory blockade to pinprick or cold sensation by 0 to 11 spinal segments, no constant relationship among these levels could be determined.156 The investigators concluded that a T6 blockade to touch would likely provide a pain-free cesarean delivery for most women.

In a survey performed in the United Kingdom, the majority of anesthesiologists used the absence of cold temperature sensation to a T4 level to indicate adequate cephalad extent of sensory blockade for cesarean delivery.157 Sensory examination should move caudad to cephalad in the midaxillary line on the lower extremities but can be performed in the midclavicular line on the torso. The time at which an adequate block is achieved, as well as the cephalad level of the block and the presence of surgical anesthesia of the lower abdomen, should be documented on the anesthetic record.

Because the undersurface of the diaphragm (C3 to C5) and the vagus nerve may be stimulated by surgical manipulation during cesarean delivery,158 maternal discomfort (including shoulder pain) and other symptoms (e.g., nausea and vomiting) may occur despite a T4 level of blockade. Neuraxial or systemic opioids help prevent or alleviate these symptoms (see later discussion).

Spinal Anesthesia

Spinal anesthesia is a simple and reliable technique that allows visual confirmation of correct needle placement (by visualization of CSF) and is technically easier to perform than an epidural technique. Spinal anesthesia provides rapid onset of dense neuroblockade that is typically more profound than that provided with an epidural technique, resulting in a reduced need for supplemental intravenous analgesics or conversion to general anesthesia.159,160 Only a small amount of local anesthetic is needed to establish functional spinal blockade; therefore, spinal anesthesia is associated with negligible maternal risk for systemic local anesthetic toxicity and with minimal drug transfer to the fetus.161,162 Given these advantages, spinal anesthesia is now the most commonly used anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery in the developed world.20,145 Spinal anesthesia is also associated with predictable and relatively prompt recovery that enables patients to quickly transition through the postanesthesia care unit (PACU); in some settings, such a recovery may result in a cost savings to the institution.159

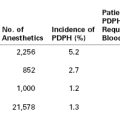

Spinal anesthesia is usually administered as a single-injection procedure (“single-shot” technique) through a non-cutting, pencil-point needle that is 24-gauge or smaller. A number of different needle designs are available (see Chapter 12)163; the size and design of the needle tip affect the incidence and severity of post–dural puncture headache (see Chapter 31).

The spinal technique should be performed at the L3-L4 interspace or below (see Chapter 12). This space is used to avoid the potential for spinal cord trauma; although the spinal cord ends at L1 in most adults, it extends to the L2-L3 interspace in a small minority (see Chapter 32). Additionally, anesthesia providers often misidentify the location of the needle insertion site on the spinal column, and the needle is more frequently introduced at a higher level than intended.

On occasion, a continuous spinal anesthetic technique is used, particularly in the setting of an unintentional dural puncture with an epidural needle. Intentional continuous spinal anesthesia may be desirable in certain settings, when the reliability of a spinal technique and the ability to precisely titrate the initiation and duration of anesthesia are strongly desired (e.g., a morbidly obese patient with a difficult airway). Although microcatheters (27- to 32-gauge) were used to provide spinal analgesia and anesthesia in the 1980s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed these catheters from the market because of concerns about cauda equina syndrome; the catheters are still being used in Europe, particularly in Germany. Currently the administration of continuous spinal anesthesia in the United States requires the use of a 17- or 18-gauge epidural needle and a 19- or 20-gauge catheter; this technique is associated with a high incidence of post–dural puncture headache.

Local Anesthetic Agents

The choice of local anesthetic agent (and adjuvants) used to provide spinal anesthesia depends on the expected duration of the surgery, the postoperative analgesia plan, and the preferences of the anesthesia provider. For cesarean delivery, the local anesthetic agent of choice is typically bupivacaine (Table 26-5). In the United States, spinal bupivacaine is formulated as a 0.75% solution in dextrose 8.25%. Intrathecal administration of bupivacaine results in a dense block of long duration.

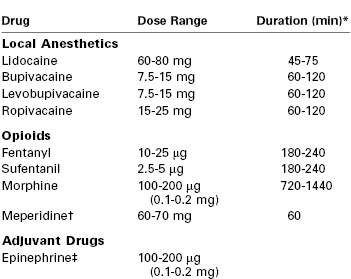

TABLE 26-5

Drugs Used for Spinal Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

* For the local anesthetics, the duration is defined as the time to two-segment regression. For the opioids, the duration is defined as the period of analgesia (or time to first request for a supplemental analgesic drug).

† Meperidine has both local anesthetic and opioid properties and can provide surgical anesthesia without the addition of a local anesthetic. The dose indicated represents meperidine used without a local anesthetic.

‡ The addition of epinephrine may augment the duration of local anesthetics by 15 to 20 minutes.

The dose of intrathecal bupivacaine that has been successfully used for cesarean delivery ranges from 4.5 to 15 mg. In general, pregnant patients require smaller doses of spinal local anesthetic than nonpregnant patients. Reasons include (1) a smaller CSF volume in pregnancy, (2) cephalad movement of hyperbaric local anesthetic in the supine pregnant patient, and (3) greater sensitivity of nerve fibers to the local anesthetic during pregnancy.164 Overall, the mass of local anesthetic, rather than the concentration or volume, is thought to influence the spread of the resulting blockade165; however, the specific influence of the dose/concentration and baricity on the efficacy of the block is controversial. The necessary dose may be influenced by other factors, such as co-administration of neuraxial opioids and surgical technique. (Exteriorization of the uterus during closure of the uterus is more stimulating than closure in situ.) Carvalho et al.166 demonstrated that the effective dose for 95% of recipients (ED95) for plain bupivacaine with fentanyl 10 µg* and morphine 0.2 mg in women undergoing cesarean delivery (n = 48) was 13 mg; the effective dose for 50% of recipients (ED50) was 7.25 mg. By contrast, Sarvela et al.167 demonstrated that spinal hyperbaric or plain bupivacaine 9 mg with fentanyl 20 µg provided satisfactory anesthesia for all but one of 76 subjects. Anesthesia characteristics and hemodynamic changes were similar in the hyperbaric and plain bupivacaine groups; more than 50% of patients in both groups required vasopressor support.

Vercauteren et al.168 demonstrated that hyperbaric bupivacaine 6.6 mg with sufentanil 3.3 µg provided better anesthesia and less hypotension than the same dose of plain bupivacaine. Ben-David et al.169 reported that reducing the dose of plain bupivacaine from 10 to 5 mg decreased the incidence of hypotension and nausea; however, these findings were obscured by the variable use of opioids in the low-dose group. Finally, Bryson et al.170 compared plain bupivacaine 4.5 mg with hyperbaric bupivacaine 12 mg (both with fentanyl 50 µg and morphine 0.2 mg); they observed similar cephalad sensory levels (C8), incidence of hypotension (approximately 75%), side effects, and rates of patient satisfaction with the two approaches. Five of 27 (19%) patients in the bupivacaine 4.5-mg group and 1 of 25 (4%) patients in the bupivacaine 12-mg group required supplemental analgesia; no conversions to general anesthesia occurred. Altogether, these data indicate that lower anesthetic doses can be used; whether they should be used is controversial. The anesthesia provider should consider whether adjuvant drugs will be used and whether the risks of giving supplemental analgesia or conversion to general anesthesia that are associated with low doses of bupivacaine outweigh the potential benefits (i.e., less hypotension, faster recovery).