Maternal Mortality

Jill M. Mhyre MD

Chapter Outline

Global Maternal Mortality

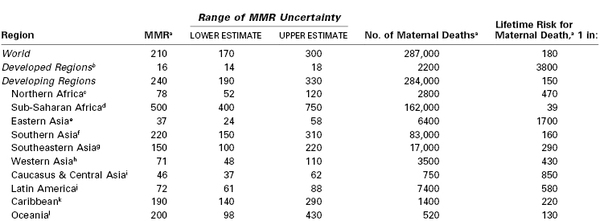

Globally in 2010, 287,000 women died while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy.1 This number corresponds to a ratio of 210 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and to a 1-in-180 lifetime risk for maternal death for each girl entering her childbearing years (Table 40-1).1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “No issue is more central to global well-being than maternal and perinatal health. Every individual, every family and every community is at some point intimately involved in pregnancy and the success of childbirth.”2

TABLE 40-1

Estimates of Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), Number of Maternal Deaths, and Lifetime Risk by United Nations Millennium Development Goal Regions, 2010

a The MMR, number of maternal deaths, and lifetime risk have been rounded according to the following scheme: < 100, no rounding; 100-999, rounded to nearest 10; 1000-9999, rounded to nearest 100; and > 10,000, rounded to nearest 1000.

b Albania, Australia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Ukraine, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America.

c Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia.

d Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

e China, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Mongolia, Republic of Korea.

f Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka.

g Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Vietnam.

h Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza Strip (territory), Yemen.

i Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.

j Argentina, Belize, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of).

k Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago.

l Fiji, Micronesia (Federated States of), Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu.

Reproduced from World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990-2010: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. Geneva, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2012.

Definitions for maternal death are listed in Table 40-2, and measures of maternal mortality are listed in Table 40-3. More than 99% of maternal deaths occur in developing countries, with 85% in either sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia (see Table 40-1). As part of the Millennium Development Goals,1 the international community committed to reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by 75% between 1990 and 2015,1 from 400 to less than 100 per 100,000 live births. Between 1990 and 2010, the global MMR fell by 47%, with the greatest reductions demonstrated in East Asia (69%), North Africa (66%), and South Asia (64%).1 Although the MMR declined 41% in sub-Saharan Africa, the lifetime risk for maternal death remains unacceptably high, at 1 in 39.1 There is considerable regional variation. Within sub-Saharan Africa, the highest MMRs are in Chad (1100) and Somalia (1000) and represent rates that are 10-fold higher than the lowest ratios in the region.1

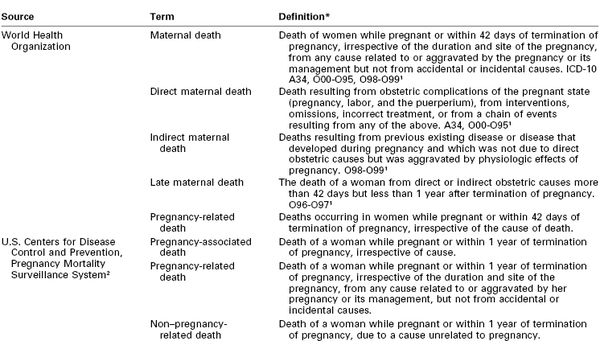

TABLE 40-2

Glossary of Terms Used in Discussions of Maternal Mortality

* Numbers after some definitions indicate cause of death codes.

1ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: 10th revision.

2From Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116:1302-9.

TABLE 40-3

Measures of Maternal Mortality

| Maternal Mortality Measure | Definitions | Reports Using the Measure |

| Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) | Direct and indirect maternal deaths, but not late maternal deaths, per 100,000 live births | WHO1 |

| Maternal mortality rate | Direct and indirect maternal deaths, but not late maternal deaths, per 100,000 maternities (pregnancies resulting in a live birth or stillbirth ≥ 20 weeks gestational age) | UK CEMD63 |

| Pregnancy-related mortality ratio (PRMR) | Pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births | US CDC PMSS75 |

| Lifetime risk for maternal death | The lifetime risk for maternal death takes into account both the probability of becoming pregnant and the probability of dying as a result of that pregnancy cumulated across a woman’s reproductive years | WHO1 |

UK CEMD, The United Kingdom Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Death; US CDC PMSS, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System; WHO, World Health Organization.

Leading Causes

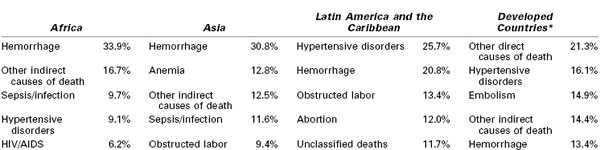

Hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and sepsis account for more than half of global maternal deaths and for slightly more than a third of deaths in the developed world.3 Hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death in both Africa and Asia (Table 40-4). Hypertensive disorders represent the leading cause in Latin America and the Caribbean.3 Infection and sepsis may be substantially underestimated in regions where laboratory diagnostic tests are unavailable.4 In one Malawi hospital with full laboratory capabilities, infection played a primary role in almost three fourths of all maternal deaths.5

TABLE 40-4

The Five Leading Causes of Maternal Death by Region

* Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, Japan.

Data from Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006; 367:1066-74.

Anemia and obstructed labor each cause approximately one tenth of maternal deaths in Asia.3 Anemia is associated with (1) iron and other micronutrient deficiencies, (2) pregnancy intervals of less than 1 year, (3) adolescent pregnancy, (4) hemoglobinopathy, (5) urinary tract infection, (6) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, (7) parasitic infections including malaria, and (8) recurrent antepartum hemorrhage.6–8 Anemia can cause lethal congestive heart failure in pregnancy7 and also increases the risk for maternal death from other complications, particularly hemorrhage and infection.6

Obstructed labor is an important cause of maternal death in communities in which early adolescent pregnancy is common, childhood malnutrition leads to small maternal pelves, and operative delivery is unavailable.9 Maternal mortality from obstructed labor is largely the result of uterine rupture or ascending genital tract infection.9,10 Prolonged pressure on the pelvic outlet can lead to tissue necrosis and obstetric fistula, which is thought to affect between 2 and 3.5 million women worldwide.11,12

HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) increases vulnerability to both nonobstetric infection (e.g., tuberculosis, malaria) and obstetric complications (e.g., hemorrhage, pregnancy-related sepsis, septic abortion).13,14 The WHO attributed 6.5% of maternal deaths in 2010 to HIV/AIDS.1 In contrast, the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation estimated that one in five maternal deaths in 2011 would not have occurred in the absence of the HIV epidemic, based on statistical models that account for the prevalence of HIV within a population.15,16 In countries most severely affected, including Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe, MMRs increased between 1990 and 2000, but they have since begun to decline as antiretroviral therapy becomes increasingly available.1,15,16

Maternal deaths attributed to unsafe abortion account for 13% of maternal deaths worldwide (47,000 in 2008).17 The WHO defines unsafe abortion as “a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy either by individuals without the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both.”17,18 Worldwide, 49% of abortions were unsafe in 2008, compared with 44% in 1995.19 The case-fatality rate (460 maternal deaths per 100,000 unsafe abortions) and the absolute number of maternal deaths per year (28,500) are highest in sub-Saharan Africa.17,20

Early marriage (before age 18 years) has been identified as a major health risk for girls, increasing their exposure to domestic violence, coercion, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS.21–23 Girls younger than 15 years are five times more likely to die in childbirth than women in their 20s,24 and pregnancy is among the leading causes of death worldwide for girls ages 15 to 19.25 Early childbearing also increases the likelihood of high parity birth (≥ 5) later in life. With a threefold increase in the MMR, high parity is the most important demographic risk for maternal death because it remains so common, accounting for 29% of births globally between 1990 and 2005.26 Advanced maternal age is less common globally but increases individual risk for maternal death as much as fourfold for women aged 35 years or older and as much as eightfold after age 40.27

Anesthesia providers working in the developing world must contend with profound limitations in staffing, equipment, and other resources.14,28–33 In addition, patients who labor at home may face a variety of social and environmental obstacles to reach a facility with the capacity to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care,34–36 and many arrive at these facilities in septic or hemorrhagic shock.37,38 Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure in Africa,39 and perioperative maternal mortality is estimated to be between 1.2% and 2%.40–42 As many as one third of deaths that occur within 24 hours of surgery have been attributed to anesthesia, mainly because of airway problems with general anesthesia or hemodynamic collapse with neuraxial anesthesia.14,28,29,43 Peripartum deaths have also been attributed to limited availability or affordability of blood products.32,40,43,44 The number of maternal perioperative deaths likely pales in comparison with maternal deaths that result from the unmet need for lifesaving obstetric procedures, including cesarean delivery.45

Strategies to reduce global maternal mortality include (1) improvement in family planning services and a reduction in the performance of unsafe abortion46,47; (2) community-based education focused on safe birth practices and indications for transfer to a higher level of care48–51; and (3) development of the infrastructure needed to provide timely emergency obstetric care, including the performance of indicated cesarean delivery (and safe administration of anesthesia) by trained care providers, who can also provide resuscitation of women in whom shock develops secondary to hemorrhage or infection.52–57 Limited human, political, and economic capital mandate ongoing rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness of future programmatic efforts.58,59 Cluster randomized trials to evaluate these strategies are beginning to appear48,49,51 and suggest that certain interventions succeed only when deployed as part of an integrated, context-specific and culturally sensitive program.55 For example, training traditional birth attendants to identify and manage complications may only improve maternal and perinatal outcomes if accompanied by ongoing training, resource support, and effective referral pathways to emergency obstetric care.60

Maternal Mortality in the Developed World

In developed regions of the world, the reported MMR has traditionally fluctuated around 10 per 100,000 live births.61 As of 2010, the WHO has reported an MMR of 16 (95% confidence interval [CI], 14 to 18). This apparent increase reflects increases documented primarily in the United States, as well as expansion of the developed world to include Cyprus, Israel, the Republic of Moldova, Belarus, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine.1

The most comprehensive maternal surveillance system in the world is the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) in the United Kingdom.* Triennial reports of CEMD in England and Wales extend back to 1952 and have covered the entire United Kingdom since the 1985 to 1987 report. By government mandate, all maternal deaths are subject to this enquiry, and health professionals have a duty to provide all requested information.62,63 Once a case is identified, practitioners are asked to provide (1) a full account of the circumstances leading up to the woman’s death, (2) all supporting records, (3) any clinical or other lessons that have been learned, and (4) details of any actions that may have been taken as a result.62,63 Regional assessors review the files to ensure completeness before removing identifying information. Central assessors compile the cases and produce the triennial reports. The reports focus on both medical and nonmedical recommendations for action to improve safety for future pregnant women.

The CEMD reports include both the internationally defined MMR and the U.K.-defined maternal mortality rate (see Table 40-3). The numerator for the U.K.-defined maternal mortality rate includes all deaths that in the opinion of the central assessors are related to pregnancy, including some causes that are not internationally coded as maternity related (e.g., suicide attributed to postpartum depression). The denominator includes all pregnancies that resulted in a live birth or stillbirth after 20 weeks’ gestation. The international MMR is calculated strictly from data coded on death certificates; the U.K. maternal mortality rate includes all deaths identified through active surveillance. As a result, the 2006 to 2008 internationally defined MMR for the United Kingdom (6.69 per 100,000 live births) is significantly lower than the 2006 through 2008 maternal mortality rate (11.39 per 100,000 maternities).63,64

National confidential enquiry reports are now published by many other countries, including Australia,65 France,66 the Netherlands,67 New Zealand,68 and South Africa.14

In the United States, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) has provided maternal death counts since 1900 and MMRs since 1915.69 Accuracy is limited because (1) the system relies on death certificates rather than active surveillance, (2) the certification of death is the legal responsibility of individual states, and (3) the process of maternal death ascertainment varies by state.

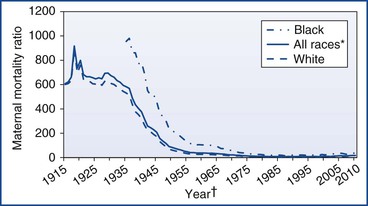

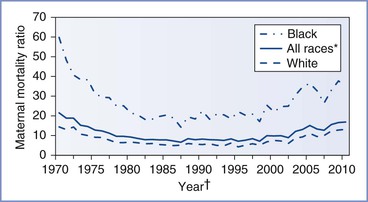

The U.S. MMR reported by the NCHS declined from more than 600 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1915 to fewer than 10 deaths per 100,000 live births by 1980 (Figure 40-1).69 Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the MMR oscillated between 6.6 and 9.2. Then in 1999, the MMR began to increase, reaching 16.6 in 2009 (Figure 40-2).70 Improvements in ascertainment explain some of the increase. In 1999, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) replaced the ICD-9 as the coding system for U.S. death certificates and liberalized the criteria by which pregnancy could be linked with death. Growing numbers of states perform electronic matches among women’s death certificates, live birth certificates, and fetal death files. In addition, increasing numbers of states have adopted the 2003 revision of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death, which introduced questions about pregnancy status at the time of death (Box 40-1). By 2005, 19 states had adopted the standard pregnancy questions; the MMR calculated from vital records in these states was 17.3, compared with 10.7 from states without any questions about pregnancy on the state death certificate.71

FIGURE 40-1 U.S. maternal mortality ratios by race, 1915 to 2010.69,70,155–158 *Includes races other than white and black. †For 1915 to 1934, data on black race not available.

FIGURE 40-2 U.S. maternal mortality ratios by race, 1970 to 2010.69,70,155–158 *Includes races other than white and black. †Beginning in 1989, race for live births tabulated according to race of mother, not child.

In 1987, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) partnered with state health departments and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to form the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS).72 To capture maternal deaths more completely, the PMSS recommended that states develop an active surveillance system and collect death certificates and matching live birth or fetal death certificates for all pregnancy-associated deaths (defined in Table 40-2). These certificates are forwarded to the CDC, where clinically experienced epidemiologists manually review the certificates to identify all pregnancy-related deaths (defined in Table 40-2). Similar surveillance enhancement procedures have been estimated to improve case ascertainment by between 22% and 93%.73 The pregnancy-related mortality ratio (PRMR) includes deaths that took place up to a year after the end of pregnancy and, according to the PMSS, increased from 10.3 in 1991 to 16.8 in 2003 before returning to 15.4 in 2005.74,75 Documentation of pregnancy on the death certificate increases ascertainment further. In 2005, among the 19 states with death certificates that include the standard pregnancy questions, the combination of data from the NCHS and the PMSS suggests an MMR of 19.7 and a PRMR of 22.3.71

Leading Causes

According to a 2006 systematic review of data from Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, embolic disorders, and hemorrhage together account for slightly less than half of maternal deaths in the developed world (see Table 40-4).3 Indirect deaths account for another 14%.3

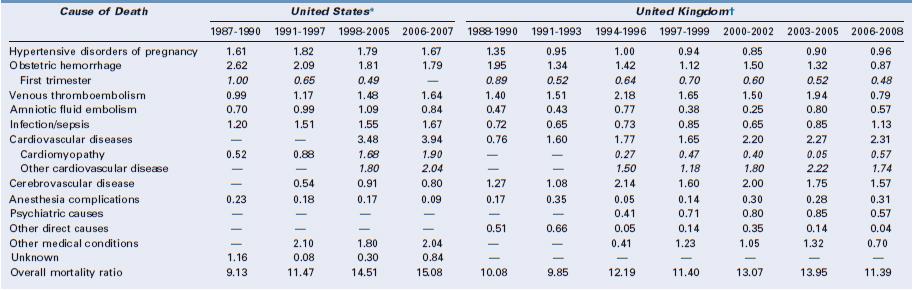

Indirect deaths have exceeded direct deaths in the United Kingdom since 1997, with cardiac disease being the most common category of death. Similar patterns are seen in the United States, where the combination of cardiovascular conditions and cardiomyopathy comprised 23% of all pregnancy-related deaths between 1998 and 2005 and cerebrovascular accidents and noncardiovascular medical conditions represented another 20%.75 Cause-specific mortality ratios are shown in Table 40-e1 (available online at expertconsult.com). Cardiomyopathy, including both peripartum and other types of cardiomyopathy, is the leading diagnosis underlying maternal cardiac death in both the United States and the United Kingdom.63,75

TABLE 40-e1

Ratios of Leading Causes of Maternal Death in the United States (1987-2007) and United Kingdom (1988-2008)

* United States: Cause-specific mortality ratio includes death during pregnancy and up to 1 year after the end of pregnancy per 100,000 live births. Data from references 1 to 4 below.

† United Kingdom: Cause-specific mortality ratio includes deaths during pregnancy and up to 1 year after the end of pregnancy per 100,000 pregnancies lasting at least 20 weeks’ gestation. Italicized numbers represent subcategories of the numbers listed above. Data from reference 5 below.

References

Venous thromboembolism was the leading direct cause of maternal death in the United Kingdom for many years (see online Table 40-e1), but a national campaign to improve venous thromboembolism prophylaxis heralded a 60% reduction in the cause-specific mortality ratio to 0.79 per 100,000 in the 2006 to 2008 CEMD report.63,76,77

During this period, sepsis due to genital tract infection emerged as the leading cause of direct obstetric death in the United Kingdom and was largely attributed to community-acquired group A streptococcal disease.63,64 Current recommendations focus on early warning scoring systems to identify vital sign derangements that could indicate systemic infection, standardized management according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, and early involvement of anesthesiologists and intensivists.63,78 More detail is provided in Chapters 37 and 55.

In the United States between 1998 and 2005, seven conditions each accounted for 10% to 13% of all pregnancy-related deaths, including hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, sepsis, thrombotic pulmonary embolism, cardiomyopathy, other cardiovascular disorders, and noncardiovascular medical disorders (see online Table 40-e1).75

Injury-related deaths are considered pregnancy-associated but not pregnancy-related; they are discussed in Chapter 55.

Risk Factors

Detailed descriptions of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, obstetric sepsis, maternal hemorrhage, embolic disorders, and cardiovascular diseases in pregnancy are provided in Chapters 36, 37, 38, 39, and 42, respectively. Common clinical and sociodemographic factors that increase the risk for maternal death from all of these complications are discussed in this chapter (see later discussion).

Advanced maternal age increases maternal risk,79 with a linear trend evident for each 5-year increase in maternal age beyond 34 years.63 In the United States between 1998 and 2005, the PRMR among women 40 years of age and older was 166.9 for black women (compared with 24.8 for black women 20 to 24 years of age) and 40.0 for white women (compared with 7.5 for white women 20 to 24 years of age).75 Based on data from the PMSS for the years 1991 through 1999, the association between age and mortality persisted after data were controlled for parity, prenatal care, race, and education.79 Among older black women (≥ 40 years), the excess risks were greatest for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, infection, cerebrovascular accident, and other medical conditions. Among older white women, the greatest excess risks for death were due to hemorrhage, cardiomyopathy, embolic disorders, and other medical conditions.79

In the United States, black or African-American race significantly correlates with the risk for death. Non-Hispanic black women experience a PRMR that is 3.5-fold higher than non-Hispanic white women. Based on death certificate data (1999 to 2009), disparities are most dramatic for deaths associated with ectopic pregnancy (black-to-white ratio of 4.8), cardiomyopathy (4.2), and deaths from complications of anesthesia (2.9).70 In a case series of anesthesia-related maternal deaths in Michigan published in 2007, six of eight deaths occurred among non-Hispanic black women in Detroit, suggesting a profound concentration of maternal risk.80 The disparity in maternal mortality between black and white women persists after data are controlled for maternal age, income, and receipt of prenatal care81 and appears to be related to a higher case-fatality rate.82

Other racial and ethnic groups also experience increased risk.63 In the United States between 1999 and 2009, in comparison with non-Hispanic white women, the MMR was 80% higher for American Indian or Alaska Native women.70 In England, black African, black Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, and Chinese women have higher relative risks of death than white women.63,83

Immigrants, asylum seekers, and non-native speakers appear to be particularly vulnerable to both maternal death and substandard care, based on data from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.63,67,83,84 In the United States, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander immigrants face increased risk compared with women of these same racial/ethnic groups born in the United States.85 Significant regional variation has been identified in France, with increased risk noted for women delivering in Paris (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.0) and the overseas districts (AOR, 3.5; 95% CI, 2.4 to 5.0) compared with continental France.86 Differences in behavior, biology, environmental conditions, social circumstances, and the quality of clinical care may contribute to disparities in outcomes for sociodemographically vulnerable populations.63,86,87

Maternal obesity increases the risk for maternal death from a variety of causes, including pulmonary embolism, infection, preeclampsia, and anesthesia-related complications. Remarkably, there are limited epidemiologic data to establish this connection. Obesity is a common feature in case series of maternal deaths. In the 2006 to 2008 CEMD report from the United Kingdom, 49% of women who died were overweight or obese.63 Among the subset of women experiencing severe obstetric complications (including eclampsia, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and antenatal stroke), obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) was associated with maternal death [AOR, 5.26; 95% CI, 1.15 to 6.46].83

Multifetal pregnancies increase maternal risk for a variety of complications, including preeclampsia, venous thromboembolism, heart failure, myocardial infarction, peripartum hemorrhage, and maternal death.63,88–91 Compared with twin pregnancies, triplet and higher-order multiple pregnancies further increase maternal risk for preeclampsia, hemorrhage, and emergency peripartum hysterectomy.89,90 In the United States between 1979 and 2000, the relative risk of death associated with a multifetal pregnancy was 3.6 (95% CI, 3.1 to 4.1) with threefold to fourfold increases in the cause-specific relative risk of death for embolism, hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, infection, cardiomyopathy, and other medical conditions.91

Cesarean delivery has also been associated with an increased risk for maternal death; however, the association does not always reflect a causal relationship. Death can be a consequence of the indication for the operation rather than the mode of delivery itself. In an attempt to estimate the relative risk of death due to cesarean delivery, a population-based case-control study from France focused on 65 maternal deaths after singleton births among low-risk women in whom complications developed only after delivery.92 Cases were identified by the French National Confidential Enquiry on Maternal Deaths from 1996 through 2000.92 These cases were compared with 10,244 singleton births to low-risk women identified through the French National Perinatal Survey conducted in 1998. After data were controlled for maternal age, nationality, parity, and preterm delivery, the AOR for increased risk for death with cesarean delivery was 3.64 (95% CI, 2.15 to 6.19). The increased risk was most dramatic for intrapartum cesarean deliveries (AOR, 4.58; 95% CI, 2.30 to 9.09) but persisted when cesarean delivery preceded labor (AOR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.14 to 5.13).92 Among women who underwent cesarean delivery, there was an increased risk for cause-specific maternal mortality from venous thromboembolism, puerperal infection, and complications of anesthesia. There was no difference in risk for death from postpartum hemorrhage or amniotic fluid embolism.

A cohort study of deliveries in Canada between 1991 and 2005 compared 46,766 planned cesarean deliveries for breech presentation with 2,292,420 planned vaginal deliveries in which labor was either spontaneous or induced.93 Planned cesarean delivery increased the risk for postpartum cardiac arrest (AOR, 5.1; 95% CI, 4.1 to 6.3), major puerperal infection (AOR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.7 to 3.4), anesthetic complications (AOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 2.0 to 2.6), and puerperal venous thromboembolism (AOR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.5 to 3.4), but did not increase the risk for in-hospital maternal death (P = .87).93

A medical record review of all in-hospital maternal deaths that occurred in a sample of U.S. hospitals between 2000 and 2006 sought to identify evidence for a causal connection between mode of delivery and the mechanism of maternal death.94 Among 1,461,270 live births, there were 95 maternal deaths (6.5 per 100,000). Although 61% of the deaths were associated with cesarean delivery, one third of these were perimortem cesarean deliveries in which the surgical procedure followed maternal cardiac arrest. Four deaths were thought to have been directly caused by cesarean delivery (attributed to hemorrhage or infection), with an additional seven deaths attributed to pulmonary thromboembolism after cesarean delivery. Two deaths were thought to have been causally related to vaginal delivery (one case of uterine inversion and one case of rupture of an unrecognized cerebral berry aneurysm during labor), and two deaths were attributed to pulmonary thromboembolism after vaginal delivery. Another 16 deaths were thought to have been potentially preventable had a cesarean delivery or an earlier cesarean delivery been performed (12 due to preeclampsia, 3 due to hemorrhage, and 1 due to sepsis).94 The investigators concluded that a policy of universal thromboprophylaxis for all patients undergoing cesarean delivery would eliminate the increased risk for maternal death caused by cesarean delivery as opposed to vaginal delivery.94

Regardless of mode of delivery, risk appears to be particularly concentrated in women with preexisting medical conditions; pulmonary hypertension, malignancy, systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, and major cardiovascular and renal disease all confer substantially increased risk for maternal death or end-organ injury.95,96 Given the preponderance of indirect deaths documented in recent CEMD reports, central assessors have repeatedly recommended both preconception counseling and intensive multidisciplinary antepartum and intrapartum care for women with serious medical or mental health conditions that may be aggravated by pregnancy.62,63 These conditions include congenital or acquired cardiac disease, obesity with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher, epilepsy, diabetes, asthma, autoimmune disorders, renal or liver disease, HIV infection, and a personal or family history of severe mental illness.62,63 The Joint Commission has advanced a similar proposal in the United States.97

Some health system characteristics have been associated with a higher risk for maternal death; they include (1) low maternal-fetal medicine specialist density98 and (2) a single physician functioning as both the obstetrician and the anesthesia provider.99

Severe and Near-Miss Morbidity

Death is considered the extreme outcome of the following continuum of adverse pregnancy events: normal pregnancy → morbidity → severe morbidity → near-miss → death.100 Approximately half of women experience some morbidity during pregnancy, most commonly anemia, urinary tract infection, mental health conditions, hypertensive disorders, and pelvic or perineal trauma.101 Research has focused on severe morbidity, near-miss events, and maternal deaths to elucidate the patient, provider, and health system factors that lead to these adverse outcomes.

Severe maternal morbidity includes those complications that have the potential to evolve toward end-organ injury or maternal death; its estimated incidence depends on the health system evaluated, the method of ascertainment, and the definition of severe morbidity used.102–105 Waterstone et al.102 evaluated pregnancies in France between 1997 and 1998 for the presence of severe preeclampsia, severe hemorrhage, or sepsis; the combined incidence for these three conditions was 12.0 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 11.2 to 13.2). Zhang et al.103 applied the same criteria across Western Europe and identified a combined European incidence for these three conditions of 9.5 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 9.1 to 9.9). Analyses of administrative codes (ICD-9 or ICD-10) for conditions that indicate severe obstetric morbidity in population-level data suggest rates of 8.1 per 1000 hospitalizations in the United States from 2004 to 2005, 13.8 per 1000 in Canada from 2003 to 2007, and 13.8 per 1000 deliveries in Australia in 2004.106–109

Near-miss morbidity occurs when a woman survives a life-threatening complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.110 The concept of a near-miss event evolved from early studies of pregnant patients who required intensive care.111–113 Mantel et al.114 proposed a definition that requires evidence of severe organ dysfunction, intensive care unit admission, emergency hysterectomy, or an anesthetic accident such as failed intubation. On the basis of these criteria, a meta-analysis of 11 studies suggests a ratio of 4.2 near-misses per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 4.0 to 4.4).115 Geller et al.116 validated a five-factor scoring system consisting of organ system failure (5 points), intensive care unit admission (4 points), transfusion of more than 3 units of blood products (3 points), extended intubation (2 points), and surgical intervention (1 point); a total score higher than 7 points defines a near-miss event. According to this scoring system, the incidence of a near-miss event was approximately 0.2 per 1000 deliveries in a perinatal tertiary care center in Chicago between 1995 and 2001.116

Maternal near-miss morbidity has also been defined using administrative data by combining ICD-9 codes for diagnoses indicating end-organ injury with either a prolonged length of stay (> 99th percentile) or transfer to a second health care facility.95 Based on this administrative data definition, the incidence of near-miss maternal morbidity or maternal death in the United States between 2003 and 2006 was 1.3 per 1000 hospitalizations for delivery.95

The WHO Working Group on Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Classification determined that end-organ injury represents the most epidemiologically sound way to identify near-miss morbidity.117 In 2009 the WHO proposed a panel of clinical, laboratory-based, or management-based criteria to identify maternal end-organ injury (see Box 40-e1 available at expertconsult.com).110,118 Cecatti et al.119 applied the WHO near-miss criteria to all ICU admissions in a tertiary care facility in Brazil between 2002 and 2007 and found a near-miss morbidity ratio of 14.7 events per 1000 live births, a MMR of 125 deaths per 100,000 live births, and a maternal near-miss-to-mortality ratio of 10.7 : 1.

Preventability has emerged as an important concept in maternal mortality and near-miss morbidity reviews because the opportunities for prevention identified from these reviews can be used to prioritize changes in clinical policy and health system improvements.64,97,120 The Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee in New Zealand proposed a comprehensive list of contributory factors, including those attributed to the health care organization, personnel, technology and equipment, the environment and geography, and patient-level barriers to accessing or engaging with care.68 Although contributory factors may be identified in the majority of maternal deaths, multiple reviews suggest that only 20% to 45% were likely preventable.66,68,116,121,122 In a case-control study of maternal death, near-miss events, and severe morbidity, Geller et al.122 identified a higher proportion of preventability among deaths and near-miss events compared with cases of severe morbidity (41% and 45% versus 17%) and suggested that provider-level improvements in medical care among women who develop severe morbidities represent the most frequent opportunities to prevent both near-miss events and maternal deaths. Across various reviews, the highest rates of preventability are noted among ethnic minorities63,67 and among deaths attributed to hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and sepsis or infection.63,123

Anesthesia-Related Maternal Mortality

Anesthesia-related maternal mortality has been defined as “death attributable to anesthesia, either as the result of medications used, method chosen, or the technical maneuvers performed, whether iatrogenic in origin or resulting from an abnormal patient response.”124 A death may be considered anesthesia-related if it can be uniquely attributed to an anesthetic complication.80 Actual case reports often include layers of comorbidities, anesthetic complications, and problems with nonanesthetic care; these cases may be considered anesthesia-related if optimal anesthetic care would likely have averted the death.80 If optimal anesthetic care in combination with improvements in obstetric or medical management would likely have saved the woman’s life, then the death may be considered anesthesia-contributing.80 In some cases, the anesthetic complication is tragic but incidental (e.g., failed intubation during advanced cardiac life support for massive pulmonary embolism).

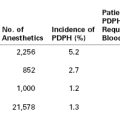

Anesthesia-related maternal death is extremely rare in the developed world. Table 40-5 shows recent MMRs attributed to anesthesia in the United States and the United Kingdom. Comparable ratios reported elsewhere in recent years include 1.4 per million live births in France for the years 2001 through 2006 and 1.0 per million in the Netherlands for the years 1993 through 2005.66,67 Active surveillance in the United Kingdom may be particularly effective at comprehensive identification of anesthesia-related maternal deaths.

TABLE 40-5

Anesthesia-Related Maternal Mortality Ratios in the United States and the United Kingdom, 1979-2008*

| Triennium | United States (95% CI) | United Kingdom (95% CI) |

| 1979-1981 | 4.3 (3.1-5.7) | 8.7 (5.5-13.2)† |

| 1982-1984 | 3.3 (2.3-4.5) | 7.2 (4.3-11.4)† |

| 1985-1987 | 2.3 (1.5-3.4) | 2.6 (1.2-5.8) |

| 1988-1990 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) | 1.7 (0.7-4.4) |

| 1991-1993 | 1.4 (0.8-2.2) | 3.5 (1.8-6.8) |

| 1994-1996 | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.5 (0.1-2.6) |

| 1997-1999 | 1.2 (0.7-2.0) | 1.4 (0.5-4.2) |

| 2000-2002 | 1.0 (0.5-1.7) | 3.0 (1.4-6.6) |

| 2003-2005 | Not available | 2.8 (1.3-6.2) |

| 2006-2008 | Not available | 3.1 (1.5-6.4) |

* Reported rates refer to the risk for anesthesia-related death during pregnancy or up to 1 year after delivery per million live births in the United States or per million maternities in the United Kingdom.

† Rates for England and Wales only.

CI, confidence interval.

U.S. data from Hawkins JL, Chang J, Palmer SK, et al. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States: 1979-2002. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:69-74; U.K. data from Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2011; 118(Suppl 1):1-203.

A number of clinical and sociodemographic factors commonly appear among cases of anesthesia-related maternal death and may play a causal role in the mechanism of death. These include (1) maternal obesity; (2) patient refusal of neuraxial anesthesia; (3) remote anesthetic location; (4) delay in anesthesia provider consultation; (5) insufficient multidisciplinary planning, communication, and coordination; and (6) inadequate supervision of care.62,63,80,124–126 In the United States, the relative risk of anesthesia-related maternal death appears to be increased for African-American women.80,124,127

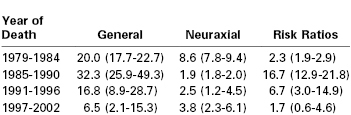

Anesthesia-related maternal deaths are distributed throughout the perioperative period and follow both neuraxial and general anesthesia, primarily administered for cesarean delivery, but occasionally for vaginal delivery or another obstetric or nonobstetric surgical procedure.62,80,126, 127 Case-fatality rates according to mode of anesthesia for cesarean delivery are presented in Table 40-6. To generate these estimates, the authors identified cases from death certificate data collected by the PMSS and estimated the total number of anesthetics delivered based on the national incidence of cesarean delivery and the proportions of cesarean deliveries completed with neuraxial and general anesthesia according to national surveys of anesthesia providers.127,128

TABLE 40-6

Case-Fatality Rates per Million Anesthetics for Cesarean Delivery in the United States (95% CI)

CI, confidence interval.

Data from Hawkins JL, Chang J, Palmer SK, et al. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States: 1979-2002. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:69-74.

Anesthesia-related maternal deaths are almost always preventable,62–64,80,126,129 as evidenced by both individual case analysis and review of historical trends. The relative risks of general and neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery in the United States have shifted over time, reflecting three major safety initiatives in anesthesia practice (see Table 40-6).130 The first initiative addressed the hazard of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST), identified as a major problem in a series of editorials published in the early 1980s.131,132 In response, in 1984, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommended that bupivacaine 0.75% not be used for epidural anesthesia in obstetric patients. Also, anesthesiologists developed a series of safety procedures to avoid the unintentional intravascular administration of a toxic dose of local anesthetic through an epidural catheter. Case-fatality rates for neuraxial anesthesia subsequently declined 78% between the years 1979 through 1984 and 1985 through 1990 (see Table 40-6). Despite this improvement in prevention, LAST remains a rare and potentially lethal complication in obstetric anesthesia, with recent events attributed to drug error by nonanesthesia providers, cumulative dosing above the toxic threshold, epidural catheter migration, and single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks.62,133–135 Lipid emulsion is now recommended as part of a comprehensive resuscitation strategy.136,137

The second initiative involved a shift toward greater use of neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery.128 Between 1985 and 1990, the relative risk of general anesthesia compared with neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery was 16.7 (see Table 40-6), and much of the increase in risk was attributed to failed intubation or aspiration of gastric contents during induction of general anesthesia or both. In response, anesthesia providers now reserve general anesthesia for specific indications, including (1) emergency cesarean delivery with insufficient time to establish neuraxial anesthesia; (2) medical conditions that make neuraxial anesthesia unsafe, such as maternal coagulopathy, hemorrhagic shock, and septic shock; and (3) failed neuraxial anesthesia with intraoperative pain.138

The third initiative introduced a series of protocols and devices to improve the safety of general anesthesia.130 Pulse oximetry and capnography have been widely credited with the decline in the incidence of unrecognized esophageal intubation.139 Failed intubation algorithms, extraglottic airway devices (particularly the laryngeal mask airway), and a heightened focus on simulation and practice have impelled a transformation in airway management toward a clear focus on effective oxygenation and ventilation as well as ongoing preparation for airway emergencies.64,140,141 Consequently, the case-fatality rate for general anesthesia decreased by 80% between the years 1985 through 1990 and 1997 through 2002 (see Table 40-6).127 Nevertheless, recent series continue to report deaths from difficult intubation, unrecognized esophageal intubation, pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents (both with anesthetic induction and emergence), postextubation airway obstruction, and postoperative respiratory arrest attributed to opioids or other respiratory depressants.* Strategies to limit the risk for airway misadventure are discussed in Chapters 29 and 30.

The relative risk of general anesthesia in comparison with neuraxial anesthesia has fallen since 1990 and was estimated to be 1.7 (95% CI, 0.6 to 4.6) between 1997 and 2002.127 In contemporary anesthesia practice, both general anesthesia and neuraxial anesthesia carry remote, but tangible risks for maternal death.

Why do women die of neuraxial anesthesia? High neuraxial block was the leading cause of anesthesia-related maternal death among women receiving neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery in the United States between 1997 and 2002.127 It was also the leading cause of legal claims for maternal death or permanent brain injury filed between 1990 and 2003 (n = 15/25; 60%), with the majority of these attributed to unrecognized intrathecal catheters intended for the epidural space.142 Single-shot spinal anesthesia administered after failed epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery represents a second clinical scenario associated with high neuraxial block.143 More details on high neuraxial block and its management may be found in Chapters 23 and 26.

Potentially lethal infectious complications of neuraxial block include meningitis, encephalitis, and neuraxial abscess.144–146 The CEMD 2006 to 2008 report included a case of acute hemorrhagic disseminated leukoencephalitis attributed to thoracolumbar spinal canal empyema.63 Current guidelines stress the importance of strict aseptic technique during neuraxial block administration, as well as appropriate monitoring and management for any infectious complications that may develop.147,148 Further details are available in Chapter 32.

Other series suggest that neuraxial cardiac arrest and hypotensive arrest may be important mechanisms by which neuraxial anesthesia can lead to maternal death.14,149 Prevention likely depends on careful attention to intravascular volume status, as well as the prompt, aggressive treatment of maternal hypotension to prevent reflex-mediated bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse.150 Finally, perioperative respiratory arrest can result from neuraxial opioids or intravenous opioids or other respiratory depressants administered during or after neuraxial anesthesia.62,80

Further efforts to improve maternal safety must include a comprehensive approach to high-quality perioperative patient care. Timely preanesthesia evaluation and ongoing communication with obstetric providers are essential to limit the number of patients who require emergency administration of anesthesia without sufficient evaluation and preparation. Problems with postoperative care have long been recognized151 but appear to account for a growing proportion of perioperative maternal deaths,61,62,125,126 particularly those attributed to respiratory events, hemorrhage, and maternal sepsis.67,68,87,143,145 The physiology of pregnancy and the compensatory physiologic responses that occur in young pregnant women may obscure early signs of septic or hemorrhagic shock. Early warning scoring systems may facilitate the early identification of women who have, or are beginning to develop, a critical illness.62,63,97,126,152 Postanesthesia and postpartum care are commonly provided by labor and delivery nurses (as opposed to perianesthesia care nurses153) with limited training and experience with major anesthetic complications, noninvasive ventilation, and advanced cardiopulmonary life support.154

Fortunately, severe morbidity and mortality are rare in obstetrics; as an unfortunate consequence of this rarity, individual clinical experience with serious adverse events will always be limited. Simulation may be an effective strategy for all obstetric and anesthesia providers to prepare for a wide variety of obstetric emergencies, including postoperative airway obstruction, failed intubation, eclampsia, anaphylaxis, maternal cardiac arrest, and maternal hemorrhage. Chapter 11 details additional strategies to enhance patient safety.

References

1. World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990-2010: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. Department of Reproductive Health and Research: Geneva; 2012.

2. World Health Organization. Ensuring Skilled Care for Every Birth. Department of Making Pregnancy Safer: Geneva; 2006.

3. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:1066–1074.

4. Costello A, Azad K, Barnett S. An alternative strategy to reduce maternal mortality. Lancet. 2006;368:1477–1479.

5. Lema VM, Changole J, Kanyighe C, Malunga EV. Maternal mortality at the Queen Elizabeth Central Teaching Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi. East Afr Med J. 2005;82:3–9.

6. van den Broek N. Anaemia and micronutrient deficiencies. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:149–160.

7. Kavatkar AN, Sahasrabudhe NS, Jadhav MV, Deshmukh SD. Autopsy study of maternal deaths. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;81:1–8.

8. Kagu MB, Kawuwa MB, Gadzama GB. Anaemia in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of pregnant women in a Sahelian tertiary hospital in Northeastern Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:676–679.

9. Neilson JP, Lavender T, Quenby S, Wray S. Obstructed labour. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:191–204.

10. Hofmeyr GJ, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1221–1228.

11. United National Population Fund and the University of Aberdeen. Obstetric Fistula Needs Assessment Report: findings from Nine African Countries. UNFPA: New York; 2003.

12. Wall LL. Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public-health problem. Lancet. 2006;368:1201–1209.

14. Department of Health. Saving Mothers 2005-2007: Fourth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa; 2008.

15. Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375:1609–1623.

16. Lozano R, Wang H, Foreman KJ, et al. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1139–1165.

17. World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Department of Reproductive Health and Research: Geneva; 2011.

18. Singh S, Remez L, Tartaglione A. Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-Related Morbidity: A Review. Guttmacher Institute; and Paris, International Union for the Scientific Study of Population: New York; 2010.

19. Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH, et al. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 2012;379:625–632.

20. Ahman E, Shah IH. New estimates and trends regarding unsafe abortion mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115:121–126.

21. Clark S. Early marriage and HIV risks in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2004;35:149–160.

22. Jain S, Kurz K. New Insights on Preventing Child Marriage: A Global Analysis of Factors and Programs. International Center for Research on Women: Washington, DC; 2007.

23. Mathur S, Greene M, Malhotra A. Too Young to Wed: The Lives, Rights, and Health of Young Married Girls. International Center for Research on Women: Washington, DC; 2003.

24. Chen LC, Gesche MC, Ahmed S, et al. Maternal mortality in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 1974;5:334–341.

25. Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881–892.

26. Stover J, Ross J. How increased contraceptive use has reduced maternal mortality. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:687–695.

27. Centre for Health and Population Research. Bangladesh maternal health services and mortality survey 2001. Bangladesh: Dhaka; 2003.

28. Dyer RA, Reed AR, James MF. Obstetric anaesthesia in low-resource settings. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;24:401–412.

29. Enohumah KO, Imarengiaye CO. Factors associated with anaesthesia-related maternal mortality in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:206–210.

30. Hodges SC, Mijumbi C, Okello M, et al. Anaesthesia services in developing countries: defining the problems. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:4–11.

31. Thoms GM, McHugh GA, O’Sullivan E. The Global Oximetry initiative. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):75–77.

32. Okafor UV, Efetie ER, Amucheazi A. Risk factors for maternal deaths in unplanned obstetric admissions to the intensive care unit-lessons for sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15:51–54.

33. Linden AF, Sekidde FS, Galukande M, et al. Challenges of surgery in developing countries: a survey of surgical and anesthesia capacity in Uganda’s public hospitals. World J Surg. 2012;36:1056–1065.

34. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1091–1110.

35. Essendi H, Mills S, Fotso JC. Barriers to formal emergency obstetric care services’ utilization. J Urban Health. 2011;88(Suppl 2):S356–S369.

36. Hirose A, Borchert M, Niksear H, et al. Difficulties leaving home: a cross-sectional study of delays in seeking emergency obstetric care in Herat, Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1003–1013.

37. Tumwebaze J. Lamula’s story. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):4.

38. Lori JR, Starke AE. A critical analysis of maternal morbidity and mortality in Liberia, West Africa. Midwifery. 2012;28:67–72.

39. Grimes CE, Law RS, Borgstein ES, et al. Systematic review of met and unmet need of surgical disease in rural sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg. 2012;36:8–23.

40. Ouro-Bang’na Maman AF, Tomta K, Ahouangbevi S, Chobli M. Deaths associated with anaesthesia in Togo, West Africa. Trop Doct. 2005;35:220–222.

41. Pereira C, Mbaruku G, Nzabuhakwa C, et al. Emergency obstetric surgery by non-physician clinicians in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114:180–183.

42. Chilopora G, Pereira C, Kamwendo F, et al. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:17.

43. Hansen D, Gausi SC, Merikebu M. Anaesthesia in Malawi: complications and deaths. Trop Doct. 2000;30:146–149.

44. Bates I, Chapotera GK, McKew S, van den Broek N. Maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: the contribution of ineffective blood transfusion services. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115:1331–1339.

45. Ronsmans C. Severe acute maternal morbidity in low-income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:305–316.

46. Carvalho N, Salehi AS, Goldie SJ. National and sub-national analysis of the health benefits and cost-effectiveness of strategies to reduce maternal mortality in Afghanistan. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28:62–74.

47. Goldie SJ, Sweet S, Carvalho N, et al. Alternative strategies to reduce maternal mortality in India: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000264.

48. Manandhar DS, Osrin D, Shrestha BP, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:970–979.

49. Jokhio AH, Winter HR, Cheng KK. An intervention involving traditional birth attendants and perinatal and maternal mortality in Pakistan. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2091–2099.

50. Kidney E, Winter HR, Khan KS, et al. Systematic review of effect of community-level interventions to reduce maternal mortality. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:2.

51. Kumar V, Kumar A, Das V, et al. Community-driven impact of a newborn-focused behavioral intervention on maternal health in Shivgarh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:48–55.

52. Bangoura IF, Hu J, Gong X, et al. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric care, an alternative strategy to reduce maternal mortality: experience of Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2012;32:151–158.

53. Liang J, Li X, Dai L, et al. The changes in maternal mortality in 1000 counties in Mid-Western China by a government-initiated intervention. PloS One. 2012;7:e37458.

54. Nyamtema AS, Pemba SK, Mbaruku G, et al. Tanzanian lessons in using non-physician clinicians to scale up comprehensive emergency obstetric care in remote and rural areas. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:28.

55. Nyamtema AS, Urassa DP, van Roosmalen J. Maternal health interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review of packages, impacts and factors for change. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:30.

56. Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–1299.

57. Paxton A, Bailey P, Lobis S, Fry D. Global patterns in availability of emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93:300–307.

58. Bullough C, Meda N, Makowiecka K, et al. Current strategies for the reduction of maternal mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1180–1188.

59. Weil O, Fernandez H. Is safe motherhood an orphan initiative? Lancet. 1999;354:940–943.

60. Wilson A, Gallos ID, Plana N, et al. Effectiveness of strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants on perinatal and maternal mortality: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;343:d7102.

61. World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality in 2005: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. Department of Reproductive Health and Research: Geneva; 2007.

62. Lewis G. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH): Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer: 2003-2005. The Seventh Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH: London; 2007.

63. Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203.

65. Sullivan E, Hall B, King J. Maternal deaths in Australia: 2003-2005. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Statistics Unit: Sydney, Australia; 2008.

66. Report of the National Expert Committee on Maternal Mortality (CNEMM), France, 2001-2006. Institut de Veille Sanitaire: Saint-Maurice; 2011.

67. Schutte JM, Steegers EA, Schuitemaker NW, et al. Rise in maternal mortality in the Netherlands. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;117:399–406.

68. Farquhar C, Sadler L, Masson V, et al. Beyond the numbers: classifying contributory factors and potentially avoidable maternal deaths in New Zealand, 2006-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:331.e1–331.e8.

69. Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality and related concepts. Vital Health Stat. 2007;3:1–13.

70. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Wonder. [Available at] http://wonder.cdc.gov/ [Accessed June 2012] .

71. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Liu X, et al. Changes in pregnancy mortality ascertainment: United States, 1999-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:104–110.

72. Berg C, Danel I, Atrash H, et al. Strategies to Reduce Pregnancy-Related Deaths: From Identification and Review to Action. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta; 2001.

73. Deneux-Tharaux C, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Underreporting of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States and Europe. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:684–692.

74. Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991-1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52:1–8.

75. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1302–1309.

76. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy, labour, and after normal vaginal delivery. Guideline No. 37. [London] 2004.

77. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and puerperium: reducing the risk. Guideline No. 37. [London] 2009.

78. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

79. Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1015–1021.

80. Mhyre JM, Riesner MN, Polley LS, Naughton NN. A series of anesthesia-related maternal deaths in Michigan, 1985-2003. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1096–1104.

81. Harper MA, Espeland MA, Dugan E, et al. Racial disparity in pregnancy-related mortality following a live birth outcome. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:274–279.

82. Tucker MJ, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Hsia J. The Black-White disparity in pregnancy-related mortality from 5 conditions: differences in prevalence and case-fatality rates. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:247–251.

83. Kayem G, Kurinczuk J, Lewis G, et al. Risk factors for progression from severe maternal morbidity to death: a national cohort study. PloS One. 2011;6.

84. Schutte JM, de Jonge L, Schuitemaker NWE, et al. Indirect maternal mortality increases in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:762–768.

85. Hopkins FW, MacKay AP, Koonin LM, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in Hispanic women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:747–752.

86. Saucedo M, Deneux-Tharaux C, Bouvier-Colle MH. Understanding regional differences in maternal mortality: a national case-control study in France. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:573–581.

87. Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–343.

88. Walker MC, Murphy KE, Pan S, et al. Adverse maternal outcomes in multifetal pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:1294–1296.

89. Day MC, Barton JR, O’Brien JM, et al. The effect of fetal number on the development of hypertensive conditions of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:927–931.

90. Francois K, Ortiz J, Harris C, et al. Is peripartum hysterectomy more common in multiple gestations? Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1369–1372.

91. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, King JC, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality among women with multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:563–568.

92. Deneux-Tharaux C, Carmona E, Bouvier-Colle MH, Breart G. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:541–548.

93. Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, et al. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. Can Med Assoc J. 2007;176:455–460.

94. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:36.e1–36.e5.

95. Mhyre JM, Bateman BT, Leffert LR. Influence of patient comorbidities on the risk of near-miss maternal morbidity or mortality. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:963–972.

96. Karamlou T, Diggs BS, McCrindle BW, Welke KF. A growing problem: maternal death and peripartum complications are higher in women with grown-up congenital heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:2193–2199.

97. The Joint Commission. Preventing Maternal Death. Sentinel Event Alert. 2010;1–4.

98. Sullivan SA, Hill EG, Newman RB, Menard MK. Maternal-fetal medicine specialist density is inversely associated with maternal mortality ratios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1083–1088.

99. Nagaya K, Fetters MD, Ishikawa M, et al. Causes of maternal mortality in Japan. JAMA. 2000;283:2661–2667.

100. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, Kilpatrick S. Defining a conceptual framework for near-miss maternal morbidity. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57:135–139.

101. Bruce FC, Berg CJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Maternal morbidity rates in a managed care population. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1089–1095.

102. Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: Case-control study. Br Med J. 2001;322:1089–1093.

103. Zhang WH, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH, Macfarlane A. Incidence of severe pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis as a surrogate marker for severe maternal morbidity in a European population-based study: The MOMS-B survey. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:89–96.

104. Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991-2001. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173:759–764.

105. Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:133.e1–133.e8.

106. Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Jamieson DJ, et al. Severe obstetric morbidity in the United States: 1998-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:293–299.

107. Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007: surveillance using routine hospitalization data and ICD-10CA codes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:837–846.

108. Roberts CL, Cameron CA, Bell JC, et al. Measuring maternal morbidity in routinely collected health data: development and validation of a maternal morbidity outcome indicator. Med Care. 2008;46:786–794.

109. Roberts CL, Ford JB, Algert CS, et al. Trends in adverse maternal outcomes during childbirth: a population-based study of severe maternal morbidity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:7.

110. Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC. Maternal near miss—towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:287–296.

111. Bouvier-Colle MH, Salanave B, Ancel PY, et al. Obstetric patients treated in intensive care units and maternal mortality. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65:121–125.

112. Baskett TF, Sternadel J. Maternal intensive care and near-miss mortality in obstetrics. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:981–984.

114. Mantel GD, Buchmann E, Rees H, Pattinson RC. Severe acute maternal morbidity: a pilot study of a definition for a near-miss. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:985–990.

115. Tuncalp O, Hindin MJ, Souza JP, et al. The prevalence of maternal near miss: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:653–661.

116. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox S, et al. A scoring system identified near-miss maternal morbidity during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:716–720.

117. Say L, Pattinson RC, Gulmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reprod Health. 2004;1:3.

118. Pattinson R, Say L, Souza JP, et al. WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:734.

119. Cecatti JG, Souza JP, Oliveira Neto AF, et al. Pre-validation of the WHO organ dysfunction based criteria for identification of maternal near miss. Reprod Health. 2011;8:22.

120. Main EK. Maternal mortality: new strategies for measurement and prevention. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:511–516.

121. Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1228–1234.

122. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:939–944.

123. The California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review: Report from 2002 and 2003 Maternal Death Reviews. California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC): Stanford; 2011.

124. Endler GC, Mariona FG, Sokol RJ, Stevenson LB. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality in Michigan, 1972 to 1984. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:187–193.

125. Cooper GM, McClure JH. Anaesthesia. Lewis G. Why Mothers Die 2000-2002: The Sixth Report of Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. RCOG Press: London; 2004:122–133.

126. Dob D, Cooper G, Holdcroft A. Crises in Childbirth—Why Mothers Survive: Lessons From the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. United Kingdom, Radcliffe Publishing Ltd: Oxford; 2007.

127. Hawkins JL, Chang J, Palmer SK, et al. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States: 1979-2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:69–74.

128. Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA. Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:645–653.

129. Wong CA. Saving mothers’ lives: the 2006-8 anaesthesia perspective. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:119–122.

130. D’Angelo R. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality: a pat on the back or a call to arms? Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1082–1084.

131. Albright G. Cardiac arrest following regional anesthesia with etidocaine and bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:285–287.

132. Marx GF. Cardiotoxicity of local anesthetics—the plot thickens. Anesthesiology. 1984;60:3–5.

133. Smetzer J, Baker C, Byrne FD, Cohen MR. Shaping systems for better behavioral choices: lessons learned from a fatal medication error. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:152–163.

134. Spence AG. Lipid reversal of central nervous system symptoms of bupivacaine toxicity. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:516–517.

135. Philippe R, Naidu R, Liu S, et al. A case report of seizures following transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks in a patient with acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Society of Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology 42nd Annual Meeting: San Antonio, TX; 2010.

136. Neal JM, Bernards CM, Butterworth JF, et al. ASRA practice advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:152–161.

137. Weinberg GL. Treatment of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:188–193.

138. Palanisamy A, Mitani AA, Tsen LC. General anesthesia for cesarean delivery at a tertiary care hospital from 2000 to 2005: a retrospective analysis and 10-year update. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2011;20:10–16.

139. Cheney FW, Posner KL, Lee LA, et al. Trends in anesthesia-related death and brain damage: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1081–1086.

140. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

141. Mhyre JM, Healy D. The unanticipated difficult intubation in obstetrics. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:648–652.

142. Davies JM, Posner KL, Lee LA, et al. Liability associated with obstetric anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:131–139.

143. Dadarkar P, Philip J, Weidner C, et al. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean section following inadequate labor epidural analgesia: a retrospective audit. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:239–243.

144. Bacterial meningitis after intrapartum spinal anesthesia—New York and Ohio, 2008-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:65–69.

145. Baer ET. Post-dural puncture bacterial meningitis. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:381–393.

146. Rodrigo N, Perera KN, Ranwala R, et al. Aspergillus meningitis following spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2007;16:256–260.

147. Practice advisory for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infectious complications associated with neuraxial techniques: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Infectious Complications Associated with Neuraxial Techniques. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:530–545.

148. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Infection control in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1027–1036.

149. Lee LA, Posner KL, Domino KB, et al. Injuries associated with regional anesthesia in the 1980s and 1990s: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:143–152.

150. Campagna JA, Carter C. Clinical relevance of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1250–1260.

151. Li XF, Fortney JA, Kotelchuck M, Glover LH. The postpartum period: the key to maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;54:1–10.

152. Singh S, McGlennan A, England A, Simons R. A validation study of the CEMACH recommended modified early obstetric warning system (MEOWS). Anaesthesia. 2012;67:12–18.

153. Wilkins KK, Greenfield ML, Polley LS, Mhyre JM. A survey of obstetric perianesthesia care unit standards. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1869–1875.

154. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems. World Health Organization: Geneva; 1992.

155. Miniño AM, Heron MP, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;55:1–119.

156. Kung H-C, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56:1–120.

157. Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J. Deaths: Final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;1–134.

158. Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58:1–134.

159. National Center for Health Statistics. United States Standard Certificate of Death—Rev. 11/2003. [Available at] www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/DEATH11-03final-acc.pdf [Accessed June 2012] .

* The Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Death have been overseen by a series of organizations in recent years, including The Confidential Enquiry in Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH), the Center for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE), and, most recently, Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the United Kingdom (MBRRACE-UK), led by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) at the University of Oxford. Future reports are planned on an annual basis starting in 2014.