Liver and Bile Duct Cancer

Ghassan K. Abou-Alfa, William Jarnagin, Maeve Lowery, Michael D’Angelica, Karen Brown, Emmy Ludwig, Anne Covey, Nancy Kemeny, Karyn A. Goodman, Jinru Shia and Eileen M. O’Reilly

• There is a continued rise of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence especially in the Western hemisphere.

• HCC main risk factors are hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

• Screening programs continue to evolve, but depend mainly on ultrasound and α-fetoprotein (AFP) evaluations.

• Staging of HCC depends on evaluating the two aspects of the disease: the cancer itself, and the commonly associated cirrhosis.

• Pathology evaluation may help distinguish variants or combined HCC and cholangiocarcinoma.

• Patterns of spread are hematogenous, and may involve lung and bones.

• Surgery, liver transplantation, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), are the sole proven curative therapies for HCC.

• Locally advanced disease is generally treated with different forms of local therapies, including but not limited to, transarterial chemoembolization, bland embolization, radioembolization, and radiation therapy.

• Sorafenib is the sole drug approved for the treatment of advanced HCC, based on an improvement in survival compared with placebo.

• Future developments are likely to be dependent on the evaluation of combination therapies and/or the development of new targets.

• Future studies are most likely to entail enriched patient populations based on biology, risk factors, and/or etiology.

• The majority of biliary tumors are adenocarcinomas.

• Despite their similarities, biliary tumors are now better understood as three different diseases: gallbladder cancer, extrahepatic, and intrahepatic biliary tumors, with different clinical and biological characteristics.

• Gallbladder resection may require resection of segments IVA and V of the liver plus a locoregional lymph node dissection for better tumor control and staging.

• Preoperative considerations for extrahepatic biliary tumors include percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

• Surgical therapy for distal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is a pancreaticoduodenectomy, as for all periampullary malignancies.

• No adjuvant therapy has been proven effective for biliary tumors.

• The standard of care for advanced disease consists of gemcitabine plus cisplatin based on the ABC-02 study.

Liver Cancer

Epidemiology

HCC is the sixth most common malignancy in the world, and is responsible for 600,000 deaths annually.1 Approximately 82% of cases arise in developing countries, with 55% in China alone, caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV). Transmission of HBV occurs both vertically and horizontally. In the United States, HCC incidence and mortality continues to rise. According to the American Cancer Society and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, 28,720 new diagnoses of primary liver cancer and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and 20,550 deaths from these diseases were expected to occur in 2012.2 Southern European countries in the Mediterranean basin have a high incidence of HCC mainly due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use.1

Egypt represents a particular and very concerning example where HCC incidence continues to increase exponentially and is a leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality.3 Egypt has one of the highest prevalences of HCV in the world, ranging between 6% and 40% in different regions. This is partly the result of a national treatment program against schistosomiasis, another known risk factor for HCC, in which the use of nondisposable needles potentially served as a conduit for transmission and a continuing epidemic.4

Worldwide, HCC is more common among men than women, with a ratio that ranges from 1.5 : 1 to 11 : 1. The male-to-female ratio is further increased in high-risk areas.5 This disparity is a consequence of the differential effects of androgens and estrogens on hepatocytes.6

Temporal age variations are also noted, reflecting different patterns of exposure to etiologic factors. In high-risk areas, the age-specific incidence rates begin to increase after the age of 20 years, reflecting the importance of vertical transmission of HBV or acquisition of HBV infection in early childhood, and stabilizes at age 50 years and older.5 In low-risk areas, the incidence rate steadily increases with age, reflecting the later acquisition of viral infection or the impact of other factors, such as alcohol-related cirrhosis.

Fibrolamellar carcinoma, which is considered a variant of HCC, is an extremely rare disease, comprising less than 1% of all primary liver cancers. Fibrolamellar carcinoma-HCC occurs equally in younger individuals, with a median age of 27 years, with a slight preponderance in women and without any underlying liver disease. It also tends to occur more frequently in whites.7

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitides, mainly HBV and HCV, are the leading risk factors for HCC in Asian and Western populations, respectively. HBV is a DNA virus that can disrupt key regulatory oncogenes of the host genome by insertional mutagenesis. Chronic inflammation because of the host immune response may also destabilize the genome, permitting the accumulation of transforming mutations leading to HCC.9 In the case of HCV, a RNA virus, hepatocarcinogenesis is driven by oxidative DNA damage and inflammation, which gives rise to cirrhosis and, eventually, HCC, in a process that may take 10 to 30 years to develop in 5% of those patients who were infected with HCV at some point.10

Metabolic Disorders

Morbid obesity, diabetes mellitus, and resultant nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are all independent risk factors for hepatocarcinogenesis.12 The metabolic syndrome is associated with peripheral insulin resistance and upregulation of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor–1 receptor (IGF1IGF–1R).13 Hereditary hemochromatosis is a common hereditary metabolic disorder in Northern European countries with a 20- to 220-fold higher risk of developing HCC.14 Other metabolic disorders associated with the development of HCC include α1-antitrypsin deficiency,15 plus several others.

Environmental Exposures

Aflatoxin, produced by the Aspergillus fungus that contaminates grain product,16 is a recognized risk factor for developing HCC in sub-Saharan Africa, and southeast Asia. Carcinogenesis occurs as a result of p53 tumor suppressor mutations as a consequence of the transversion of glycine (G) to threonine (T) at codon 249.17,18

Betel quid consumption is a popular practice in several Asian countries. The major carcinogenic ingredient in betel quid is the arecoline alkaloid.19 Mouse models have shown that toxicity occurs through immunosuppression, structural hepatocyte injury, and suppression of antioxidants.

Contaminated water in parts of rural China with microcystins, a blue-green algal hepatotoxin, can cause HCC by increased oxidative DNA damage20 and induction of apoptosis by increasing expression of p53 and Bax while suppressing expression of Bcl-2.21

Prevention and Early Detection

Measurement of serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) is the most widely employed screening test for HCC in an at-risk population.22 One prospective study in an HBV carriers’ population randomized 5581 men to undergo either AFP testing every 6 months or no screening.23 Overall survival was not different between the screened and unscreened populations. On the other hand, in a larger trial, 18,816 patients with HBV were randomized to screening with serum AFP levels and liver ultrasonography biannually compared to no screening. Among individuals assigned to the screening arm, HCC mortality was reduced by 37%.24 AFP screening continues to be a subject of debate, although most physicians elect to continue using it in practice.

The role of other serologic tests such as assays for des-γ-carboxy prothrombin, Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction (AFP-L3), and insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF1) remains unclear.25

Adjunctive screening with ultrasonography on an every 6 month basis also is recommended by published guidelines.22 The sensitivity and specificity of screening ultrasound in high-risk patients are 71% and 93%, respectively.26 Ultrasound examination is cheap and safe but has low sensitivity for detection of small nodules, and its usefulness in this regard is particularly operator-dependent. Newer techniques, such as helical computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including the newer gadoxetate acid-enhanced MRI, remain unclear in regard to any impact on mortality rates in at-risk populations.27 And, of course, the issue of cost and affordability are critical in defining early detection strategies.

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

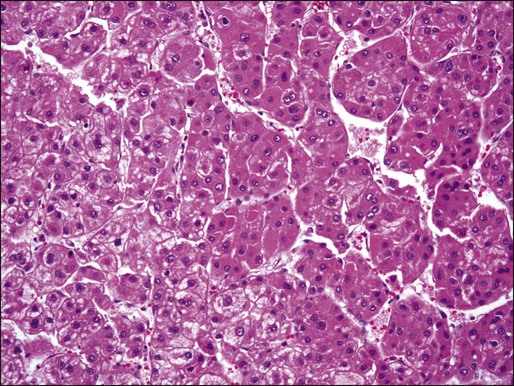

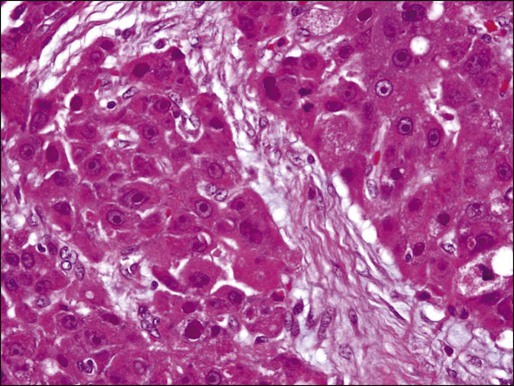

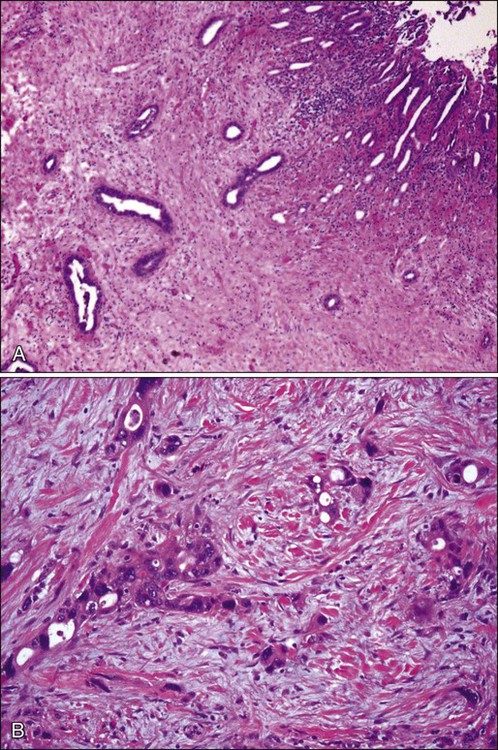

HCC is a malignant neoplasm derived from the hepatocytes. Grossly, HCCs associated with liver cirrhosis often present as expansile tumors with a fibrous capsule and intratumoral septa; in contrast, tumors arising in noncirrhotic livers tend to grow to massive size and may be nonencapsulated (Fig. 80-1). All HCCs have a strong propensity for invasion of vascular channels, and large vein invasion may be seen grossly. Histologically, HCCs assume a wide spectrum of morphologic alterations (Fig. 80-2). Well-differentiated HCCs recapitulate the cellular and architectural characteristics of benign hepatocytes to such extent that a histologic diagnosis of malignancy can be a challenge, especially in small biopsy samples. On the other hand, poorly differentiated tumors may lose almost all histologic hallmarks of hepatocytes. A variety of histologic patterns have been described, including trabecular, acinar, solid, and scirrhous. The prognostic significance of these patterns, however, is yet to be determined.

Approximately 5% of all primary liver tumors are combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma.6,8 The WHO defines such tumors as having unequivocal, intimately mixed elements of both HCC and cholangiocarcinoma. The hepatic component is defined by the presence of bile production, bile canaliculi, and a trabecular pattern of growth. The glandular component is defined by the presence of true gland formation.

A distinctive clinicopathological variant of HCC is the fibrolamellar carcinoma, which occurs in young adults and has no association with cirrhosis or other known risk factors. This variant tends to present as well circumscribed, nodular, yellow-to-brown tumors with extensive fibrosis grossly. Some tumors may present with a “central scar.” Histologically, this variant is characterized by the presence of dense bands of lamellar fibrous tissue separating the tumor cells that are typically polygonal and exhibit large nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 80-3).

Immunohistochemical studies may aid in the diagnosis of hepatocellular neoplasms. Characteristic hepatocellular markers include the hepatocyte antibody, also known as HepPar-1, glypican-3, an oncofetal protein elevated in the sera of many patients with HCC, polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CD10, which both label hepatocytes in a canalicular pattern, and AFP. Fibrolamellar carcinomas tend to express CK7 and epithelial membrane antigen, two markers that are typically not expressed in conventional HCC, which can help to differentiate between fibrolamellar carcinoma and HCC.28

HCC characteristically invades the portal vein and its branches, and vascular invasion is the main route for intrahepatic tumor spread. Tumor invasion into the major bile ducts is infrequent clinically, but may be seen histologically. Intraorgan spread of HCC is considered under the T category, not M, in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system.29 Extrahepatic tumor spread is common, and is mainly via hematogenous dissemination and targets the lung most commonly, followed by bone and other sites such as the adrenal glands.30 In recent years, bone metastases from HCC have increased in incidence.31 In a retrospective evaluation over 5 years at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, almost 10% of HCC patients were found to have bone metastases at presentation (unpublished data). This increasing potential for metastatic disease is mainly explained by the improved survival of HCC patients across the board. It is thus imperative that patients with HCC receive appropriate staging that includes a whole body radiologic evaluation including the chest. Bone scans should be done in case of symptoms or suspicious radiologic or laboratory findings.

Lymph node metastasis is more commonly seen in fibrolamellar carcinoma. In a recent retrospective analysis of 95 cases of fibrolamellar carcinoma from three institutions, lymph node metastases were present in 50% of the cases.32

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

Clinical Manifestations

Although a majority of patients present with locoregional disease, many patients present initially with stage IV disease or develop metastases at a later time. Recurrences after surgery are either intrahepatic or extrahepatic, with the most common sites of extrahepatic metastasis being lung, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and bone. Clinical manifestations may include malaise, anorexia, abdominal pain, abdominal fullness because of ascites or mass effect, or weight loss. Acute abdominal pain and distention caused by the spontaneous rupture of a superficial tumor with resulting hemoperitoneum is a common presentation of HCC in high-prevalence areas.33 This potentially fatal event is a medical emergency that warrants early recognition and management.

Patient Evaluation

All patients with suspected HCC also should undergo hepatitis serologic studies, including testing for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antibody, and hepatitis C antibody. Where applicable, a polymerase chain reaction quantitative assay should be performed. Depending on the degree of underlying liver damage from fibrosis, results on liver function testing and the prothrombin time may be abnormal. An assessment of liver function should be performed; the most commonly used assessment with the most widespread availability is the Child-Pugh score. Although there are guidelines to help diagnose HCC using imaging and AFP levels, these are applicable for screening and surveillance situations.34–37 Their application, of course, will depend on a faithful application of the criteria, which include a diagnosis of cirrhosis (which remains ill defined). Newer technology may help improve the noninvasive diagnosis of HCC. Gadoxetate disodium is a new gadolinium-based contrast agent indicated for intravenous use in T1-weighted MRI of the liver to detect and characterize lesions in adults with known or suspected focal liver disease.38 Cholangiocarcinoma is commonly identified in what was thought to be HCC.39,40

In the setting of advanced disease, and especially if systemic therapy is considered, a biopsy is very valuable. As described in the pathology section, diagnosis of HCC may include variants, as well as possible combined cholangiocarcinoma plus HCC, the treatment of which will differ from that of HCC. Translational research using tissue specimens have been pivotal in the elucidation of key signaling pathways that may be targeted with novel therapies. Liver biopsy is a comparatively safe and well-tolerated procedure. Although it is true that it carries a risk of bleeding and tumor seeding, these complications are rare with hemorrhage reported in 0.4% of cases and tumor seeding in 1.6% of cases.41,42

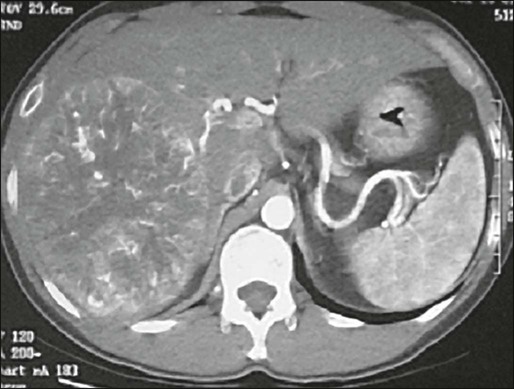

Dynamic CT has replaced ultrasonography in assessing HCC. In the early phase, the tumor is hyperdense because of its increased vascularity (Fig. 80-4). In the later phase, the tumor is hypodense, as a result of washout of contrast from the more “porous” lesion. On MRI, HCC is of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and of intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Because of the propensity of this tumor for extension into and along major vessels, contrast-enhanced triple-phase CT or MRI is particularly useful for imaging the portal and hepatic veins. In addition, contrast-enhanced images provide critical information about multifocality, resectability, and presence of extrahepatic disease.

Although positron emission tomography using fluorine 18-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) has been found to be useful to image a variety of tumors, its use in HCC has yielded disappointing results, with significantly lower standardized uptake values for HCC compared with metastatic tumors or other primary liver tumors.42

Staging

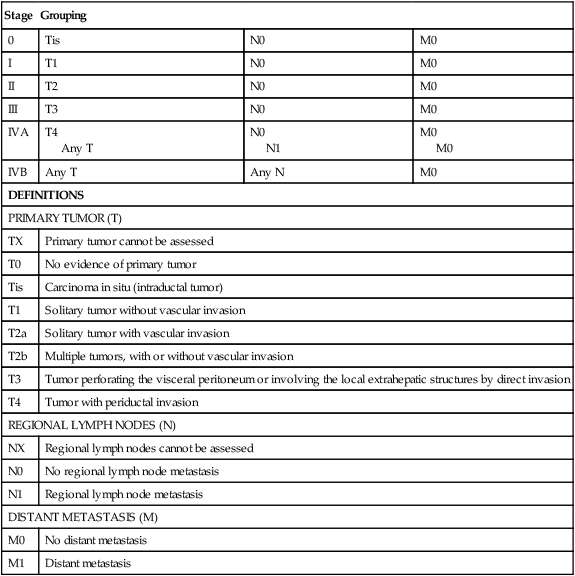

The seventh edition of the AJCC staging classification uses size, presence of vascular invasion, lymph node status, and metastatic disease as prognosticators of outcome (Table 80-1). The main features of this revised system included a separate staging systems for HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a split of the T3 category to reflect the different prognoses of large multifocal lesions versus the presence of macrovascular invasion, a redefined the N1 category, and a classification of lymph node metastases as stage IV disease.29

Table 80-1

American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging System for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Including Intrahepatic Bile Ducts: Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) Classification

| Stage | Grouping | ||

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IVA | T4 Any T |

N0 N1 |

M0 M0 |

| IVB | Any T | Any N | M0 |

| DEFINITIONS | |||

| PRIMARY TUMOR (T) | |||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (intraductal tumor) | ||

| T1 | Solitary tumor without vascular invasion | ||

| T2a | Solitary tumor with vascular invasion | ||

| T2b | Multiple tumors, with or without vascular invasion | ||

| T3 | Tumor perforating the visceral peritoneum or involving the local extrahepatic structures by direct invasion | ||

| T4 | Tumor with periductal invasion | ||

| REGIONAL LYMPH NODES (N) | |||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| DISTANT METASTASIS (M) | |||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | ||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

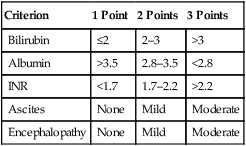

The prognosis of HCC depends not only on an anatomic assessment of the tumor, but also on the extent of underlying liver cirrhosis. The Child-Pugh scoring system remains the most commonly used tool for assessing cirrhosis.45–45 It remains the most common scoring system used in HCC clinical trials. It consists of five parameters: serum bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time, clinical ascites, and clinical encephalopathy. The severity of each parameter is graded from 1 to 3 (Table 80-2), and the total make up the score that is defined as A to C.

Table 80-2

Modified Child-Pugh Classification for Assessing Degree of Liver Impairment

| Criterion | 1 Point | 2 Points | 3 Points |

| Bilirubin | ≤2 | 2–3 | >3 |

| Albumin | >3.5 | 2.8–3.5 | <2.8 |

| INR | <1.7 | 1.7–2.2 | >2.2 |

| Ascites | None | Mild | Moderate |

| Encephalopathy | None | Mild | Moderate |

INR, International normalized ratio.

From Child CG, editor. The liver and portal hypertension. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1964. p. 50.

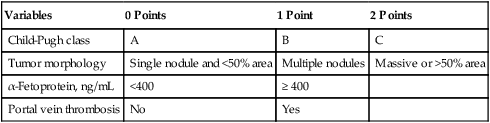

The limitations of both the TNM and Child-Pugh systems was first overcome by the Okuda staging system,46 which includes parameters related to the cirrhosis and factors related to the cancer itself. The Okuda scoring system was considered by many as unsatisfactory and several scoring systems followed, many of which were prospectively validated. These include, but are not limited to, the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP),47 the Chinese University Prognostic Index (CUPI) scoring system,48 the Groupe d’Etude et de Traitement du Carcinoma Hepatocellulaire (GETCH) staging system,49 the Japan Integrated Staging (JIS),50 and the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification system.51 The BCLC couples prognosis with treatment assignment; however, it has been found to be less valuable in the setting of more advanced disease, defined as BCLC category C.52,53 It was found that the CLIP (Table 80-3), CUPI, and GETCH scoring systems were the most informative regarding the outcome of this specific patient population, while the BCLC classification system had limited discriminatory abilities in this population, and its use is not recommended for patients with advanced disease.

Table 80-3

Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Scoring System

| Variables | 0 Points | 1 Point | 2 Points |

| Child-Pugh class | A | B | C |

| Tumor morphology | Single nodule and <50% area | Multiple nodules | Massive or >50% area |

| α-Fetoprotein, ng/mL | <400 | ≥ 400 | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | No | Yes |

From the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators. Prospective validation of the CLIP score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2000;31:840-845.

Primary Treatment and Adjuvant Therapy

Primary Therapy

Resection

Partial Hepatectomy

In patients with limited disease and no underlying liver parenchymal disease, the outcome after resection can be reasonably good. The operation can be performed with an operative mortality rate of less than 5% in high volume centers, and 5-year survival may exceed 30%.54–58 This subgroup represents, however, a small minority of all patients with HCC, as the vast majority have at least some degree of underlying liver disease or frank cirrhosis. The adverse influence of cirrhosis on surgical outcome is well documented, with very high perioperative mortality rates, up to 10% in some series from high-volume centers.55–59 From the same series, cirrhotic patients who survive the operation may enjoy a reasonable 5-year survival rate, approximately 30%. Recent series, albeit small, have shown further improvements in outcome, with perioperative mortality of at least 1.4% and 5-year survival rate of 77%.60,61 These patients are at very high risk, not only for recurrent disease, but also the development of new sites of malignancy in the diseased liver remnant and deterioration of liver function resulting in hepatic failure. Indeed, the presence or extent of cirrhosis has been shown to be an independent predictor of reduced survival.58,60

Thus, when assessing patients for surgery, careful evaluation of the hepatic functional reserve is equally as important as the disease extent and feasibility of a complete resection. The single most reliable method of assessing hepatic function is the Child-Pugh classification (see Table 80-2),44,45 which remains the most useful and most widely used in Western series, although the indocyanine green retention rate commonly is used in Asia. A more sensitive assessment of hepatic function is the hepatic vein wedge pressure, a technique that may be particularly useful for identifying patients with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis with occult portal hypertension.62 The invasive nature and special radiologic expertise required for this study have limited its use.

Most surgeons will consider resection only for patients with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis and in selected patients in the Child-Pugh B category; with major resections only considered in the former group. Few surgeons are willing to perform hepatic resection for patients with Child-Pugh C, considering a high operative mortality rate of 30%. Nonetheless, some studies have reported reasonable long-term survival even when a larger tumor size required extended hepatectomy, rather than more limited resection.63,64 In general, though, these patients are better served with transplantation if they meet accepted criteria.

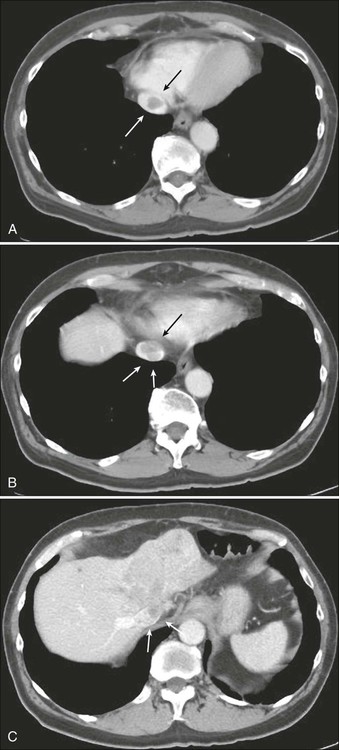

HCC has a great propensity for vascular extension, and the presence of tumor thrombus within the main portal vein or vena cava (E-Figure 80-1 and Fig. 80-5) is an ominous sign that, in general, is a contraindication to resection because of the very high risk of occult disseminated disease. Liver resections accompanied by portal venous tumor thrombectomies are unlikely to yield long-term survival.

Multiple lesions do not necessarily preclude surgical resection or ablation (or both).55,57,65 Five-year survival rates can still be expected to be between 20% and 30%.55,57 Nonetheless, the presence of multiple tumors is associated with reduced survival after resection compared to resection of solitary tumors.60 Furthermore, tumor size is a well-known predictor of disease recurrence and survival.58,66

One strategy that may improve outcome after resection is preoperative portal vein embolization. This technique involves occlusion of the portal vein supplying the portion of the liver targeted for resection, typically the right hemiliver. This procedure results in atrophy of the liver to be resected and hypertrophy of the future liver remnant, and theoretically should result in a lower risk of postoperative liver failure. Indeed, a recent prospective study demonstrated the usefulness of preoperative portal vein embolization in patients undergoing resection of HCC, with significant reductions in postoperative liver failure, overall morbidity, and hospital length of stay.67

Total Hepatectomy and Transplantation

The “Milan criteria” have become the standard guidelines for hepatic transplantation in patients with hepatic cirrhosis: single tumor less than 5 cm in size or no more than 3 tumors all less than 3 cm in diameter, after transplantation demonstrated an actuarial 4-year survival rate of 75%.68 This report refocused attention on liver transplantation for HCC, which was verified in several subsequent reports.69 Using these criteria, several series have found excellent 5-year survival rates of 70% or greater, with a 15% chance for recurrence.61,70–73

In comparing the results of transplantation with those of resection, it is important to recognize the inherent selection bias of choosing not only those patients with small HCC for transplantation, which is associated with a better prognosis, but additionally the bias of performing transplantation in those patients whose disease has not progressed while on the waitlist. Thus the patients who receive liver transplants are those whose tumors have a less-aggressive natural history. This point is demonstrated by an intention-to-treat analysis that found “drop-out from waiting list” to be the sole survival predictor.74 This study noted that the 2-year survival rate of patients evaluated for transplantation was reduced from 84% to 54% during two separate time periods in which the wait time increased markedly, so that more patients were excluded from transplantation as a result of progression of disease. Survival was significantly worse for patients on the transplant list than for patients who were the best candidates for resection.75 A more recent study found that when the wait list time exceeded 4 months, the differences between resection and hepatic transplantation were not detectable.76

The problem of the waiting list is well-recognized and has resulted in a number of strategies to improve outcome, the most notable of which is the use of ablative therapy, specifically transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), for patients awaiting transplantation. Using this strategy probably reduces dropouts from the waiting list, although its impact on long-term outcome is unclear. It is clear, however, that patients who have a response to such treatment prior to transplantation, even those with tumors exceeding the Milan criteria, appear to have a good prognosis.77 Another factor is the advent of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) for assessing the likelihood of death on the waiting list, and the policy of awarding a greater number of MELD points for patients with transplantable HCC.75,78

Transplantation yields better long-term survival figures when compared directly to resection, but such comparisons are impossible to interpret given the marked differences in patient populations. In a number of recent studies that evaluated outcomes in patients undergoing liver resection with tumors that fit the Milan criteria, the overall survival rates were comparable with those of transplantation.60,61,79,80 As expected, the risk of intrahepatic recurrence in patients undergoing resection was higher than after liver transplantation. To address this problem, a strategy of salvage transplantation for those patients whose tumor recurs after hepatectomy has evolved and may be useful, although it has recently been shown that not all such patients benefit from such a strategy, which may be best used in the setting of favorable histopathological findings.61

In practice, many obstacles exist to limit the applicability of transplantation to a large number of patients worldwide. The greatest obstacle is the lack of available organs for transplantation. In Asian countries, where the need for donor organs is greater, along with the social and cultural obstacles, livers are in even greater shortage than in the United States. Living donor liver transplantation has, therefore, emerged as a potential means of filling the gap, although its use is associated with significant donor-related morbidity and mortality and is quite controversial. Because this procedure requires a right hepatectomy in a healthy donor, concerns have arisen about the safety and ethical implications of this procedure. In addition, sporadic reports of deaths in donors have intensified these concerns. In one of the largest series reporting the results of living donor liver transplantation in 71 patients, with approximately 40% a result of HCC, the mean waiting time to transplantation was markedly reduced from 414 (for cadaveric organ transplants) to 83 days (for living related donor transplants), with a recurrence rate of 15%.81

Although perioperative morbidity and mortality rates are declining in most centers, the mortality rate is still substantial. Operative mortality rates have been as high as 20%,82,83 and recurrence rates, as high as 50%,84 although more recent results are more favorable.72 Nevertheless, for patients with liver dysfunction, total hepatectomy with liver transplantation represents the only potentially curative option, because few of these patients can tolerate major hepatectomy. To demonstrate this point, in noncirrhotic HCC, survival is similar after hepatectomy or transplantation, whereas in patients with cirrhotic HCC, survival was significantly improved after transplantation compared with hepatectomy at each TNM stage.54 The cost associated with the transplantation procedure is also a major obstacle.

Treatment Complications

After resection, postoperative morbidity occurs in approximately 40% of patients, consisting primarily of transient hepatic insufficiency, intraabdominal abscess or biloma, gastrointestinal bleeding, and cardiopulmonary complications.55 Postoperative mortality rates range from 3% to 12% in most series. After transplantation, the 90-day mortality rate has been as high as 15% but is lower in more recent series.75,85,86

Follow-up Program

First follow-up evaluation after resection of HCC should include an office visit 2 to 3 weeks after hospital discharge. Liver transaminases, as well as AFP, are assessed. A return of tumor markers to normal levels postoperatively should dictate a routine follow-up approach of office visits every 3 to 6 months with history and physical examination and measurement of liver function tests and tumor markers. Patients should be asked about symptoms of worsening portal hypertension or liver failure and symptoms of biliary obstruction, including itching or changes in stool or urine color, primarily because a significant proportion of patients die from liver failure, not HCC.87 Of greatest importance is adequate treatment to prevent the complications of portal hypertension, because it is estimated that up to one-fourth of patients who die after diagnosis of liver cancer succumb to gastrointestinal bleeding from portal hypertension.88 New-onset right upper quadrant pain or bone pain should prompt investigation by appropriate radiologic examinations. Physical examination should evaluate for new masses, worsening ascites, and jaundice. The follow-up program also should include contrast-enhanced abdominal CT every 6 months, with a chest radiograph obtained yearly. Five years after resection, office visits should be reduced to every 6 months. The follow-up program also must aim to prevent and treat complications of associated etiologic parenchymal disease, for example, HBV and hemochromatosis, as well as others.

Treatment of Recurrence

Because recurrent HCC may be amenable to potentially curative resection, early detection of such recurrences is extremely important. Multiple series have shown that 5-year survival rates between 20% and 82% are possible in patients with recurrent HCC that is resectable.89–93 In addition, repeated liver resection can be done safely.90 Therefore in patients found to be medically fit for surgery, with adequate liver reserve and technically resectable tumors, repeat hepatic resection is the therapy of choice. In patients who are not candidates for repeat resection but who have isolated liver recurrence, liver transplantation may be possible. Salvage transplantation may be appropriate in selected patients with liver isolated recurrence that is within Milan criteria.61 In patients who are not candidates for any surgical intervention, local therapies may be indicated.

Ablative Therapies

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection therapy has been replaced by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the treatment of small (<5 cm) HCC, based on several studies that have shown a higher rate of complete necrosis achieved with fewer treatments in the RFA group.94–97 As experience has broadened, complications after RFA have become infrequent, reaching a low rate of 2.2% following ablation of 2982 tumors in 1170 patients with one death.98

A randomized trial of RFA versus surgery for solitary HCC smaller than 5 cm found that percutaneous RFA achieved similar 4-year overall survival rates of 67.9% and 64%.99 RFA has also been used to treat patients who are listed for transplantation to avoid dropoff.100 Radiofrequency ablation has also been used as an adjunct to transarterial embolization. In a retrospective case controlled study of patients with HCC tumors smaller than 7 cm, survival outcome following transarterial embolization plus RFA was similar to surgical resection, although median recurrence-free survival was longer in the surgical group.101 Cryoablation has not been adopted for the treatment of HCC in view of serious complications and a high local recurrence rate of 31%.102

Adjuvant Therapy

So far no adjuvant strategy has been shown to be effective in prospective controlled studies. Retinoic acid has been shown to activate DNA repair mechanisms or induce apoptosis of hepatoma cells containing carcinogen-DNA adducts.103 In a prospective adjuvant trial, peretinoin prevented the occurrence of second primary HCC tumors after curative surgery or percutaneous ethanol ablation.104 Survival at 6 years was 74% versus 46% for the placebo group.105 A larger phases II/III trial of high- and low-dose peretinoin compared with placebo did not meet the primary end point of significantly improving recurrence-free survival.106

A study assessing a single-dose treatment of intraarterial iodine 131-labeled lipiodol versus observation was terminated early when an interim analysis demonstrated a marked difference in survival for patients in the treatment group: 57.2 months versus 13.6 months.107 This approach was never carried to a larger trial in a broader patient population. Direct intraportal 5-FU, cisplatin, and doxorubicin demonstrated an improvement in disease-free and overall survival when compared with case-matched control subjects.108

Considering the angiogenic flare that starts immediately after surgery,109 sorafenib is currently being evaluated in a phase III trial versus placebo (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00692770). Its use in the adjuvant setting is not recommended at present and will depend on the outcome of the so-called STORM trial.

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

Hepatic Artery Embolization

Embolization of the feeding arterial vessels is one possible treatment option for patients with locally advanced unresectable HCC. A randomized, controlled trial that assessed chemoembolization, embolization or best supportive care (BSC) showed a survival advantage for chemoembolization, with a 2-year survival probability of 63%, compared with 27% for control and 50% for embolization.110 When the study was stopped, there were not enough patients enrolled in the embolization arm to make any statement regarding the effectiveness of this technique compared to BSC. However, there was no significant difference in outcome between the embolization and chemoembolization groups. A second study demonstrated a survival advantage for chemoembolization when compared to BSC.111

Data supporting the retention of chemotherapeutic agents within tumors that have been chemoembolized are not robust; many reports are in small numbers of patients, from animal models, or use techniques that are not applied in clinical practice.112–115 Some hypothesize that the primary effect of chemoembolization is to cause tumor cell death by ischemia. There are no randomized control trials comparing embolization with particles alone to BSC, however results of embolization alone in treating a large number of patients with HCC suggest that the outcome is comparable to chemoembolization.116 Because there are no data demonstrating a survival advantage of chemoembolization over bland embolization, either technique may be used to treat patients who are not surgical candidates.117 Obviously, a bland embolization with small particles instead of TACE, avoids the added expense and potential systemic toxicity of chemotherapy.

Starting in the 2000s, two other catheter-based transarterial therapies have come into widespread use for the treatment of unresectable HCC: chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads (DEBs) and radioembolization (RAE). Advances in technology have resulted in the development of spherical embolics that can be loaded with chemotherapy. These embolics provide a reliable method of delivering chemotherapy to liver tumors where the drug is then slowly eluted into the surrounding tissue over days.118 For the treatment of HCC, the DEBs are typically loaded with doxorubicin, although they can be loaded with other agents. In 2009, the Precision V trial, a multicenter randomized trial of DEBs compared to conventional TACE conducted in Europe, reported no difference in response to treatment between the two groups and established the safety and efficacy of DEBs.119 Of note, this trial demonstrated decreased liver and systemic toxicity associated with the use of DEBs compared with conventional TACE. These results were replicated in another prospective randomized trial.120 A third prospective randomized trial showed a better response to treatment and longer time to progression in the patients treated with DEBs but no difference in survival.121 These data supporting the effectiveness of DEBs when compared to conventional TACE with decreased hepatic and systemic toxicity has led to the widespread adoption of DEBs for transcatheter treatment of HCC. Recent data of a randomized trial of DEBs loaded with doxorubicin compared with embolization with unloaded beads did not show a difference in response to treatment, time to local tumor progression, or overall survival 4 versus 16 months (P = 0.7).122

In one of the largest studies of RAE for HCC using yttrium-90 (90Y)-loaded resin spheres, 291 treated patients led to the demonstration of a median survival of 17.2 months in Child-Pugh class A patients and 7.7 months in Child-Pugh B patients.123 Although the treatment is administered transarterially, the embolic effect is minimal and imaging response to treatment may be delayed. Because the embolic effect is minimal the treatment is better tolerated than chemoembolization or embolization and patients can be treated without an overnight stay in the hospital. The same group reported their experience with 90Y RAE compared with conventional TACE in a retrospective analysis of 245 patients and found decreased toxicity and significant increase in time to progression in the group treated with RAE.124 There was no difference in survival between the two groups with median survival of 17.5 months in the chemoembolization group and 17.2 months in those treated with RAE. There are organ specific radiation dose limitations encountered with RAE that cannot be exceeded, limiting the ability to repeat treatment.

The addition of antiangiogenic therapy following embolization has proven to be safe125 and biologically sound.126 In the latest reported data of a randomized study of TACE plus sorafenib versus placebo, even a treatment with sorafenib, that may clamp any possible surge of angiogenesis, failed to demonstrate any improvement in time to progression.127,128 This approach is still being evaluated in an ongoing randomized study (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01004978).

Radiation Therapy

Low doses of whole-liver irradiation were initially evaluated in the management of unresectable HCC; however, these low doses were ineffective in controlling HCC and higher doses resulted in high rates of radiation hepatitis or radiation-induced liver disease characterized by anicteric hepatomegaly, ascites, and elevated liver enzymes, which can occur up to 3 months after irradiation.129,130 Three-dimensional conformal RT (3DCRT), and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) allow partial liver irradiation and has been used for patients with unresectable liver tumors.133–133 These techniques allow for more conformality of the radiation dose to be prescribed to the target volume along with strict dose constraints on normal tissues. Using the higher RT doses (median: 51 Gy) achieved using 3DCRT or IMRT, investigators have reported 2-year in-field progression-free and overall survival rates of 93% and 62%, respectively, for unresectable HCC patients.134 This and another study have reported no cases of radiation-induced liver disease.135

Focal, high-dose stereotactic body RT has been incorporated into the treatment of unresectable HCC.131,136–139 Stereotactic body RT exploits the benefit of overcoming the potential radio-resistance of HCC cells to conventionally fractionated RT with the delivery of very high doses of radiation to the tumor mass and also minimizing normal hepatic irradiation. High-dose, focal RT using charged particles, such as protons and heavy ions, has also been studied, particularly in Asia.140–142,143 These newer modalities may be able to minimize normal tissue effects via precise dose localization, and are being investigated further.

RT has also been evaluated in the adjuvant setting following TACE146–146 and has been used to dissolve tumor thrombosis.147,148 Although the role for RT in HCC is expanding as imaging and treatment-planning technology have allowed for safe delivery of higher doses to liver tumors, pivotal trials are still needed.

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

Chemotherapy

The most extensively studied agent in HCC is doxorubicin, due to a provocative report of a 79% response rate.149 This outcome was never reproduced and doxorubicin failed to show any improvement in survival beyond 6 months.150,151 A range of other chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin, gemcitabine, capecitabine, paclitaxel, irinotecan, etoposide, and fludarabine, have been investigated and found to have minimal activity.152–158

Combination chemotherapy is associated with modestly improved response rates at the expense of greater toxicity, yet no clear standard has emerged because of the lack of significant improvement in survival. One of the most studied combinations is a regimen of cisplatin, interferon-α2b, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil (PIAF).159 The initial phase II report noted a high response rate of 26%. Additionally, nine patients were able to undergo surgery, of whom four had pathological complete response. The approach was limited by a high rate of myelosuppression and mucositis, with two treatment-related deaths related to neutropenic infection. A randomized phase III study of 188 patients comparing PIAF with doxorubicin.150 showed no statistically significant difference in median survival (8.6 months vs. 6.8 months, P = 0.83), despite a doubling in response (21% vs. 10%, P = 0.058).

The combination of gemcitabine and the platinum agent oxaliplatin (GEMOX) showed a partial response of 18% and 56% of patients had stable disease. This translated into a median survival of 11.5 months.160 Oxaliplatin was combined with capecitabine (CAPOX) in a phase II study that reported partial responses in 6% of patients, stable disease in 58% and a median survival of 9.3 months.161

Novel Therapies

Antiangiogenics

The advent of targeted agents was commensurate with a better understanding of the biology of HCC.162 As a vascular tumor, HCC harbors high levels of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and this is correlated with a poor prognosis.163,164 Sorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor that targets VEGF receptor (VEGFR) (–2/–3), in addition to RAF kinase and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β tyrosine kinases.165 A large phase II study examined the use of single-agent oral sorafenib in 137 patients with inoperable HCC and Child-Pugh A or B status, with no prior systemic treatment.166 Median time to disease progression was 4.2 months, and median overall survival was 9.2 months. Following these results, a phase III study of sorafenib versus placebo that was open to patients with advanced HCC Child-Pugh A patients, (SHARP trial), showed a clinically and statistically significant improvement in median overall survival of 10.7 months versus 7.9 months (HR 0.69, P < 0.001), in favor of sorafenib.167 The most common toxicities leading to sorafenib dose reductions and/or discontinuation were fatigue, diarrhea, abdominal pain, hand-foot skin reaction, rash or desquamation, and liver dysfunction in 3% to 8% of patients. Bleeding and cardiac ischemia/infarction were rare.

A similar study, called The Asia-Pacific Trial, enrolled 271 patients with advanced HCC and Child-Pugh A cirrhosis in a 2 : 1 randomization of sorafenib versus placebo.168 Median overall survival favored sorafenib (6.5 months vs. 4.2 months, HR 0.68, P = 0.014). Although the hazard ratio of sorafenib benefit was similar between the two phase III trials, the median overall survival was notably longer in the SHARP population compared to the Asia-Pacific population (10.7 months and 6.5 months, respectively). A direct comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the SHARP and Asia-Pacific populations showed the patients in the Asia-Pacific study to be more ill and possibly started systemic therapy at a later time in their disease when compared to the patients on the SHARP trial. This difference in magnitude of the positive outcome, may also be related to the different etiologies of HCC. This controversial issue is discussed further under “Controversies, Challenges, and Problems” below.

Sorafenib has also been evaluated in combination therapies. A randomized double-blinded phase II study of doxorubicin plus sorafenib and doxorubicin plus placebo in patients with advanced HCC and Child-Pugh A cirrhosis showed in an exploratory comparison, the combination of doxorubicin plus sorafenib to have improved median overall survival (13.7 months from 6.5 months, P = 0.006) compared to doxorubicin plus placebo.151 This data add to multiple hypothesized mechanisms underlying the possible synergy between sorafenib and doxorubicin, including the status of Ask-1,169 and overcoming multidrug resistance.170 This study led to the development of the first National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored phase III trial of sorafenib plus doxorubicin versus sorafenib in HCC (CALGB 80802, www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01015833).

Bevacizumab is a humanized anti-VEGF A monoclonal antibody that has also been studied in HCC. In a phase II study, hemorrhagic toxicity was a concern with 11% of patients experiencing grade 3 or greater events and there was one fatal episode of variceal bleeding, prompting an amendment requiring that patients with a history of varices or evidence of varices on imaging undergo pretreatment endoscopies.171 Bevacizumab was also studied in combination. In a phase II trial of bevacizumab plus a gemcitabine-oxaliplatin combination, median progression-free survival time of 5.3 months, and median overall survival time of 9.6 months were obtained.172 Similarly, a first-line study of bevacizumab with capecitabine and oxaliplatin resulted in median progression-free and overall survival of 6.8 and 9.8 months, respectively.173 The most promising combination is bevacizumab plus erlotinib that is based on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling producing proangiogenic effects, and VEGF upregulation undermining anti-EGFR therapy.174 A phase II trial assessing the combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib in 40 patients with treatment-naïve advanced HCC reported a median progression-free survival of 9 months and median overall survival of 15.7 months.175 An update of the trial, which included 19 patients with BCLC stage C disease, as well as patients previously treated with sorafenib, reported median progression-free and overall survival were 7.2 months and 13.7 months, respectively.176 A randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab and erlotinib versus sorafenib in the first-line setting for advanced HCC is underway (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00881751). On the other hand, a phase III trial evaluating sorafenib plus erlotinib versus sorafenib failed to show a statistically significant benefit to the combination arm with the median overall survival being 9.5 months for the combination versus 8.5 months for single agent sorafenib (HR 0.929, 95% CI: 0.781-1.1.06, P = 0.204 1-sided).176a

Sunitinib is a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor of VEGFR, PDGFR, c-KIT, and FLT-3 kinases. Despite several phase II studies of sunitinib in HCC that have reported modest antitumor activity, with a median overall survival of 8 to 9.8 months,179–179 a first-line phase III study comparing sunitinib with sorafenib in a predominantly Asian population was terminated early because of an inferior median overall survival of sunitinib compared with sorafenib (7.9 months vs. 10.2 months, HR 1.3, P = 0.001) plus excessive toxicity.180

Upregulation of basic fibroblast growth factors can initiate tumorigenesis and is thought to be a mechanism of acquired resistance to VEGF inhibition.181 Brivanib is an orally administered dual inhibitor of VEGF and fibroblast growth factor signaling. Following a phase II first-line study that showed a median overall survival of 10 months,182 a phase III trial was initiated and is awaiting reporting (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00355238, NCT00858871). A second phase III placebo-controlled trial evaluated brivanib in the second-line setting, but did not meet its primary end point of overall survival (9.4 months vs. 8.2 months, P = 0.3307) despite a statistically significant improvement in time to progression (4.2 months vs. 2.7 months, P = 0.0001) and response rates (12% vs. 2%, P = 0.0032) over placebo.183 Despite its negative outcome, this study has important implications regarding the understanding and expectation of what a median overall survival on placebo in the second line may be. It is speculated that the dynamic improvement in the general care of patients with HCC may have contributed to this increase in overall survival.

The platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) family of receptor tyrosine kinases encompasses PDGF-α, PDGF-β, FLT3, KIT, and CSF-1R. Together, PDGF and VEGF play complementary roles in angiogenesis. The modulatory effects of PDGF on the tumor microenvironment also promote tumor progression and survival.184 Linifanib (ABT 869) is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor of both PDGF and VEGF signaling that is undergoing investigation in a number of malignancies, including HCC. Following a phase II study that reported a median overall survival of 9.7 months,185 a phase III trial of linifanib versus sorafenib in advanced HCC naïve to systemic therapy showed no survival benefit: 9.1 months for linifanib versus 9.8 months for sorafenib (HR 1.046, 95% CI: 0.896, 1.221).185a Other antiangiogenics that have been evaluated in HCC include ramucirumab,186 which is currently being evaluated in a phase III study against placebo (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01140347), and cediranib (AZD2171) (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00427973).187

Extracellular Signaling Pathways

Ligand binding of EGFR can lead to activation of the Ras/Raf/Erk/MAPK cascade.188 EGFR can be inhibited extracellularly by antibody binding or intracellularly through inhibition of its tyrosine kinase. EGFR inhibitors did not show much activity as single agents in HCC. Among those tested were cetuximab,189 gefitinib,190 lapatinib,191,192 and erlotinib.193,194 Of note, the combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab carried promise, as discussed under “Antiangiogenics” above.

Obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are features of the metabolic syndrome, which is a recognized risk factor for the development of HCC.195 A phase II study of the anti-IGF–1R) antibody, cixutumumab (IMC-A12), in advanced HCC was terminated for inefficacy after 24 patients were enrolled.196 The combination of cixutumumab and sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC naïve to systemic therapy is undergoing evaluation in both phase I and phase II studies (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00906373, NCT01008566).

BIIB022 (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00956436) and AVE 1642197 are two other anti-IGF–1R antibodies undergoing evaluation in HCC both in combination with sorafenib. OSI-906 is an oral dual inhibitor of IGF–1R and the insulin receptor.198 A randomized phase II study in advanced HCC was terminated by the sponsor (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01101906), but another phase II study assessing the combination of OSI-906 and sorafenib is still ongoing (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01334710).

The c-met receptor tyrosine kinase and its cognate ligand, hepatocyte growth factor, are potent mitogens that coordinate hepatogenesis in the developing embryo and promote regeneration and maintain the integrity of the mature liver.199 Tivantinib (ARQ197), an oral non–adenosine triphosphate-competitive c-met tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is currently being studied in a phase IB study of patients with Child-Pugh A or B cirrhosis and HCC, with preliminary data demonstrating acceptable toxicity.200 A phase I dose escalation study of tivantinib and sorafenib in HCC has shown that the combination is well tolerated and may be active in treatment-naïve as well as pretreated disease.201 A randomized phase II study of tivantinib versus placebo in the second-line setting demonstrated an improved median time-to-progression (2.7 months vs. 1.4 months, HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19-0.97; P = 0.03, and 7.2 months vs. 3.8 months, P = 0.01, respectively) among c-met positive patients as defined by the majority (≥50%) of tumor cells with moderate or strong (2+ or 3+) staining intensity.202 c-Met expression has also been reported as a prognostic factor among patients randomized to placebo, with an improved median overall survival of 9 months among c-met–negative compared with 3.8 months among c-met–positive patients (P = 0.02).

Several hybrid antiangiogenic and c-met inhibitors have also been developed and are being studied in HCC. Results from the HCC subset of a phase II discontinuation study of cabozantinib (XL184), a dual c-met/VEGFR-2 inhibitor demonstrated a median progression-free and overall survival of 4.4 months and 15.1 months, respectively.203 Foretinib, another c-met/VEGFR-2 inhibitor, is also being studied in a phase I/II trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00920192).

Intracellular Signaling Cascades

Clinical experience with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in advanced HCC suggests disease stabilizing activity in both the first-line setting and after progression on sorafenib.204 Phases I/II and III trials examining everolimus monotherapy in the first- and second-line settings are currently underway (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00390195, NCT00516165, NCT01035229), along with combination regimens of everolimus with bevacizumab, sorafenib, or pasireotide (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00467194, NCT01005199, NCT01488487). Temsirolimus is also being assessed in combination with sorafenib in phases I and II studies (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01335074, NCT01013519), and with bevacizumab in a phase II trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01010126).

Arginine deprivation therapy with pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) capitalizes on the auxotrophy of HCC cells as they lack the enzyme necessary for its synthesis. Preclinical as well as clinical studies have shown promising antineoplastic activity in HCC.205,206 A phase III, placebo-controlled, second-line trial of ADI-PEG in HCC is currently underway (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01287585).

Intraarterial Chemotherapy

The regional administration of chemotherapy using the hepatic artery has the attraction of achieving high concentrations of drug in the liver and minimizing systemic exposure, particularly if drugs are used that undergo a high degree of first-pass metabolism. The usual coexistence of cirrhosis complicates the local delivery of drugs however, and possible arteriovenous shunting may result in unwanted systemic exposure.207 Numerous small phase II studies have examined various combinations, the most common components being floxuridine (FUDR), mitomycin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin.207–217 Other variations of these therapies include hepatic arterial infusion (HAI)-cisplatin plus systemic interferon.218,219

Although intraarterial chemotherapy never established itself as a standard for either locally advanced or metastatic HCC, it is still a favored therapeutic approach, particularly in Japan,220 despite the limited proof of an overall survival benefit.

Controversies, Problems, and Challenges

Systemic Therapy in Patients with Advanced Cirrhosis

Sorafenib’s safety in more than Child-Pugh A patients is of concern. A subgroup analysis of the phase II sorafenib study reported higher rates of hepatic decompensation, represented by worse hyperbilirubinemia, encephalopathy, and ascites in Child-Pugh B compared with Child-Pugh A patients.221 This was commensurate with a shorter treatment duration, as well as shorter survival in Child-Pugh B (3.2 months) versus Child-Pugh A patients (9.5 months). In another study, there were no substantial differences in the incidence of adverse events between Child-Pugh A and Child-Pugh B groups. However, geometric means of AUC0–12 and Cmax at steady state were slightly lower in patients with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis compared with Child-Pugh A.222

Similar findings have been reported from the phase IV postmarketing study of sorafenib known as GIDEON.223 Child-Pugh B and C patients were treated for a shorter duration, and were more likely to develop hepatic and serious drug-related adverse events and also experienced a lesser survival benefit on sorafenib. Based on a phase I study of sorafenib pharmacokinetics in patients with hepatic dysfunction, patients with a serum bilirubin less than or equal to 1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN) can safely initiate sorafenib at the full dose of 400 mg twice daily while those with a bilirubin 1.6 to 3 × ULN should be considered for a 200 mg twice daily. Sorafenib at 200 mg once daily was recommended for patients with an albumin less than 2.5 mg/dL and any bilirubin level. There was no safe dose identified for patients with a bilirubin greater than 3 × ULN.224

Although this situation seems mostly applicable to sorafenib, other antiangiogenic therapies have shown a disadvantage against patients with advanced cirrhosis.185 Nonetheless, this should not be adopted as a universal fact, and efforts should continue to evaluate potential therapies in patients with HCC and advanced cirrhosis. A current study is evaluating vismodegib in such a population (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01546519).

Systemic Therapy and Etiology

There is a continued debate whether advanced HCC represents the same disease regardless of etiology, or different diseases based on implications from different risk factors. The genomic basis of the malignant phenotype seems to be heterogeneous and varies based on etiology.225 Clinical observations support this possibility. The difference in outcome between patients treated on sorafenib in the SHARP and the Asia-Pacific studies,167–168 may be driven at least in part by the HBV versus HCV etiology. In a subset of HCV and HBV patients enrolled in the SHARP study, median overall survival was 14 months versus 7.4 months and 9.7 months versus 6.1 months with placebo, respectively.226 Although the outcome of patients with HBV in the SHARP trial was never reported, a retrospective subset analysis of the phase II study by viral etiology reported a trend toward longer survival among patients with HCV (12.4 months) than with HBV (7.3 months).227 A potential explanation is that the HCV viral core protein can activate Raf-1 kinase in HCC cells,228 theoretically sensitizing them to sorafenib. This potential difference has also been noted in a subgroup analysis of patients treated with sorafenib as part of the phase III trial comparing first-line sunitinib to sorafenib. The magnitude of overall survival benefit with sorafenib varied widely based on etiology and ethnicity, ranging from 18.3 months for patients from outside of Asia with HCV, to 7.9 months for patients from Asia with HCV.180 Obviously these data are not enough to recommend any difference in usage of sorafenib. This is especially true vis-à-vis a new analysis that did not show any biomarker as a predictor of response to sorafenib.229 Nonetheless, future studies may very well be etiology and/or ethnicity specific based on the molecular basis of a specific therapy or combination of therapies.

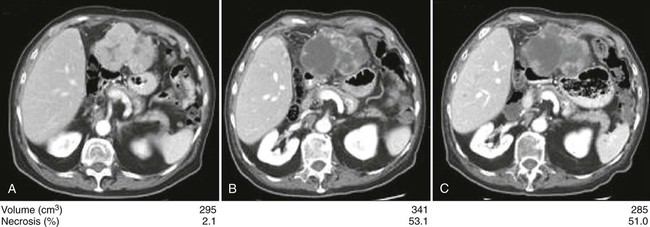

How to Assess Response to Novel Therapeutics in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Responses by the different World Health Organization (WHO) or Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria to antiangiogenic therapies have been almost nonexistent, although a survival benefit is evident. It is obvious that new methodology may be needed. A modified form of the RECIST criteria (mRECIST) has been proposed. This includes an assessment of tumor tissue viability based on the amount of intratumoral contrast uptake during the arterial phase of dynamic imaging studies.230 A limitation of these criteria is that changes in intratumoral enhancement may result from the effects of antiangiogenic therapies on tumor vasculature without reflecting actual antitumor activity. Prospective validation of the mRECIST criteria is still missing, and thus its use are not recommended at present. A novel approach of semiautomated delineation of HCC tumors, and detecting necrosis inside the tumor has been developed and an increased ratio of tumor necrosis to tumor volume from baseline have been observed in patients responding to sorafenib (Fig. 80-6).231 The tumor necrosis-to-tumor volume ratio is currently under evaluation for validation as part of the CALGB 80802 evaluating sorafenib plus doxorubicin versus sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01015833).

There have been other advances in imaging of HCC, including dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI,171,232 along with a continued interest in diffusion- weighted MRI, blood oxygen level–dependent MRI, image subtraction, and functional MRI. Until any of these techniques are validated, decision making for continuing systemic antiangiogenic therapy should depend on a global evaluation of patients. This should include but not be limited to a clinical assessment, a physical examination, plus blood and radiologic test results.

Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

As the incidence of hepatocellular cancer is rising, it is imperative to develop improved screening tests that increase the sensitivity and specificity for detecting HCC. A more sensitive means to detect recurrence may be evaluating the serum for the presence of AFP messenger RNA by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay.233 Molecular studies to assess for genes associated with a high risk of recurrence have shown promise in preliminary studies, but require further evaluation.236–236 Clearly, it would be helpful if the molecular characterization of specific genes associated with an increased risk for developing HCC could help with early detection or prevention.237

Gallbladder Cancer

Epidemiology

Approximately 6000 to 7000 new cases of gallbladder cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year.238 Gallbladder cancer is more common in women than in men in all populations, and in some geographic areas the rates are three times higher for women. Incidence increases with age in all populations.239,240 Certain geographic areas are characterized by a high incidence of gallbladder cancer, including South America and India,243–243 with the highest incidence of gallbladder cancer in women from La Paz, Bolivia (15.5 cases per 100,000 population).240 A high incidence also has been documented in North American Native Americans and Mexican Americans. The geographic variability clearly correlates with populations that have a higher rate of gallstone formation. To further strengthen this association, the mortality rate from gallbladder cancer has been inversely correlated with cholecystectomy rates in Chile, a high incidence region.244

Etiologic and Biological Characteristics

Although an increased risk of gallbladder cancer with cholelithiasis is recognized, gallbladder cancer develops in less than 0.5% of patients with gallstones.245 Up to 85% of patients with gallbladder cancer are found to have gallstones,246,247 that are probably related to chronic inflammation.

The other main associated risk factors include chronic infections of the gallbladder and environmental exposure to chemicals such as thorotrast, a preparation of colloidal thorium dioxide, that is associated with an increased incidence rates for all cancers by three times over that in the general population, with the largest increase in primary liver and gallbladder cancers.248 Thorotrast is no longer used. One higher-risk subset of patients with gallbladder disease is the population with “porcelain gallbladder,” a calcified gallbladder wall, with a risk of approximately 5% for developing gallbladder carcinoma (Fig. 80-7).249

Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder, usually incidentally found, are highly likely to be malignant if they are sessile, increasing in size or have a diameter greater than 10 mm; surgical resection is indicated if one or more of these features are present.250 Patients with choledochal cysts have an increased risk for the development of carcinoma anywhere in the biliary tree. However, the incidence is higher in the gallbladder (12%).251 The risk of carcinogenesis increases with age. Complete surgical resection is recommended for all patients with choledochal cysts at the time of diagnosis. An anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction has been found to be associated with gallbladder cancer, occurring in up to 65% of cases.252,253

Recent epidemiological studies have confirmed an association between obesity, in particular abdominal obesity, and gallbladder cancer. This suggests a potential for public health interventions addressing the prevention of weight gain in adulthood to reduce the incidence of gallbladder malignancy in addition to the other benefits of decreasing obesity.254

Prevention and Early Detection

Because of the strong association of gallbladder cancer with gallstone disease, the question has been raised as to whether all patients with gallstones should undergo elective cholecystectomy. However the historical practice of performing cholecystectomy only in symptomatic patients, thus leaving the gallbladder in place in patients with asymptomatic gallstones, has not led to an increase in the prevalence of gallbladder cancer. epidemiological studies have found the 20-year risk of developing cancer in patients with gallstones is less than 0.5% for the overall population and 1.5% for high-risk groups.245 Thus, routine preventive cholecystectomy against the risk of developing gallbladder cancer remains unwarranted.

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

The microscopic appearance of gallbladder carcinomas varies depending on the histologic type. Adenocarcinomas recapitulate the glandular features of the gallbladder epithelium and may assume a variety of histologic patterns: adenocarcinoma, gastric foveolar type; adenocarcinoma, intestinal type; clear cell adenocarcinoma; mucinous adenocarcinoma; and signet ring cell carcinoma. However, the majority shows features typical of pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinoma. Characteristically, the malignant tumor glands are widely separated by a fibrotic stroma and have a random or haphazard distribution pattern (Fig. 80-8A) and are simple in appearance. The constituent tumor cells are often cuboidal in shape. Almost invariably, however, gallbladder carcinomas harbor areas with individual, or cords of, tumor cells with significant cytologic atypia (Fig. 80-8B).

Limited information exists regarding the genetic changes in gallbladder cancer. The most widely reported gene abnormalities associated with gallbladder cancer include p53,255 K-ras,255,256 and CDKN2 (9p21) mutations.256,257

The gallbladder differs histologically from the rest of the gastrointestinal tract in that it lacks a muscularis mucosa and submucosa.258 Gallbladder carcinoma may spread locoregionally to the liver or adjacent structures by direct extension or to the regional lymph nodes through the lymphatic drainage.259 The cystic duct lymph node is believed to be the sentinel node for the gallbladder. From there, carcinomas can spread to other regional lymph nodes. Gallbladder cancers frequently invade directly into the liver, which is involved in 70% of patients at the time of surgical evaluation.

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

Gallbladder cancer commonly manifests as an intraoperative or pathological incidental finding after cholecystectomy for presumed benign disease. Up to 47% of cases are incidentally detected at routine cholecystotomy,260 but most patients also present with advanced disease. In the same series 53% of patients presented with advanced or disseminated disease.

Although early gallbladder cancer is notoriously asymptomatic, a common physical finding is right upper quadrant tenderness.261 A palpable mass, hepatomegaly, ascites, or jaundice are signs of advanced disease.262 Laboratory tests may reflect advanced disease, for example, elevated liver enzymes, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, or leukocytosis.261 Although tumor markers are not helpful screening tests for gallbladder cancer, in some studies they have prognostic relevance.263 The most helpful tumor markers are CEA and carbonic anhydrase 19-9 (CA19). These markers can be helpful baselines tests to follow patients through treatment.264,265

Ultrasound is a readily available and excellent imaging modality for assessing gallbladder masses. The most common findings in a patient with gallbladder cancer is asymmetric thickening of the gallbladder wall or a mass involving all or part of the gallbladder (Fig. 80-9).266 The diagnostic difficulty increases when inflammation is present from gallstones especially when gallbladder cancer presents as a diffusely thickened wall. Ultrasound is an excellent modality to assess local invasion into the liver but is limited in its ability to visualize distant nodal or metastatic disease.267,268 Endoscopic ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound are newer modalities that may enhance the role of ultrasound in the workup of gallbladder cancer.269

Cross-sectional imaging with dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI are an important part of the initial workup to assess local extent of disease, as well as nodal and distant metastases. Imaging should include the chest, as pulmonary metastases are a common location of metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP) can provide detailed information on biliary anatomy and involvement in a noninvasive manner.270,271 With the advent of MRCP, direct cholangiography is rarely necessary to delineate biliary anatomy and extent of involvement in patients who are jaundiced. Direct cholangiography should be reserved for patients with jaundice and unresectable disease to relieve symptoms of biliary obstruction. A mid-bile duct obstruction not caused by gallstones represents gallbladder cancer until proven otherwise.

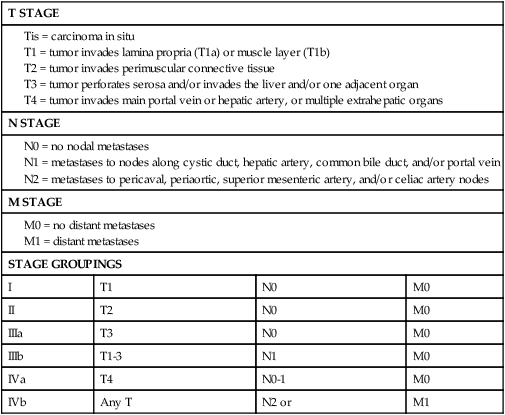

The AJCC’s TNM staging system (Table 80-4) reflects prognostic characteristics of tumor depth, regional nodal disease, and distant spread and has been updated in its seventh edition. The earliest stages have the most potential for surgical cure and are T1 (stage I) and T2 (stage II) disease without nodal metastases. In general, T1 tumors rarely present with nodal metastases but T1b tumors have associated nodal disease in 10% to 15% of cases. T2 tumors have associated nodal metastases in approximately one-third of cases while T3/4 tumors have nodal disease 75% to 80% of the time.272

Table 80-4

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Primary Treatment and Adjuvant Therapy

Long-term survival and cure are possible with appropriate surgical treatment in patients with localized disease and resectable tumors. T1 tumors uncommonly have lymph node metastases and with complete margin negative resection are cured 85% to 100% of the time; often with a simple cholecystectomy.275–275 In completely resected T2 tumors (hepatic resection and regional node dissection) 5-year survival has been reported to range from 60% to 100%.276,277 In locally advanced T3 and T4 tumors long-term survival can occur with complete resection but only at a rate of 15% to 20%. Successful outcome in patients with locally advanced tumors is strongly dependent on nodal status.278 Lymph node–positive disease is an ominous sign. Patients with lymph node metastases outside of the porta hepatis are generally considered incurable. Patients with nodal metastases confined to the porta hepatis and completely resected do poorly with few cures, but have a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 20%.278,279 There are few, if any 5-year survivors among patients who present with jaundice.262

Many patients present having had a noncurative cholecystectomy and requiring subsequent hepatic resection and lymphadenectomy. These patients do not appear to have a worse outcome than those who present without a prior cholecystectomy when matched stage for stage.276 Difficulty can arise at the time of surgery for a gallbladder mass as it will not always be clear whether the tumor is benign or malignant. Although frozen section diagnosis is fairly reliable in determining whether lesions are malignant or benign (95% accurate), the accuracy in correctly assessing depth of invasion is only 70%.280 It is probably important that patients with gallbladder cancer be identified before cholecystectomy. These comparisons are limited by selection bias and simple cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer has been shown to have the potential risk of peritoneal seeding.281,282 Unfortunately, resection is indicated in only 25% of patients, although more recent studies have shown higher resectability rates.260

Role of Staging Laparoscopy

Gallbladder cancer has a marked propensity to spread intraabdominally, with up to 50% of patients found to have unresectable disease at the time of laparoscopy (Fig. 80-10).283 Patients with this tumor are ideal candidates for detection of intraabdominal metastases with laparoscopy.285–285 A recent study, however, documented low yields of less than 5% from staging laparoscopy in patients with a recent incidentally detected gallbladder cancer at cholecystectomy.286

Extent of Resection

The gallbladder is only partially enveloped by visceral peritoneum and the “liver side” of the gallbladder contains the single muscular layer of the gallbladder wall attached to the cystic plate of the liver. There is, therefore, a very short distance from the gallbladder wall into the substance of the liver. A simple cholecystectomy, by definition, dissects directly along the muscular layer and is an inadequate cancer operation for all tumors except for the earliest malignancies (T1a tumors). Lymph node drainage is generally to the cystic duct and porta hepatis nodes, but there are well-defined direct lymphatic channels from these regional lymph nodes to the celiac axis and aortocaval space.287 The initial part of the operation for gallbladder cancer should include a thorough exploration for distant disease in the peritoneum, liver, and lymph nodes. A specific exploration of the celiac axis and retropancreatic/aortocaval area should be carried out as these areas are notorious for containing occult metastatic disease, which, if present, would preclude resection.

Because the gallbladder is essentially attached to the liver, some element of a hepatic resection is critical to completely resect the tumor.288 A limited segmental resection of segments IVb and V, as long as this accomplishes a negative margin, is an adequate operation.278 Larger resections are reserved for tumors that involve hepatic inflow structures. A portal lymphadenectomy including the cystic duct node and nodes along the proper hepatic artery and porta-caval space is appropriate for staging and locoregional control. Bile duct resections have been shown to be associated with significantly higher morbidity and no difference in survival. The operation must be tailored to the location of the tumor, with larger more extensive resections being performed when anatomically necessary to achieve a negative margin.278,279