Introduction Hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery

Historical perspective

Ancient History until the Eighteenth Century

A tablet believed to be from the time of Hammurabi (about 2000 bce), now in the British Museum, names the various parts of the liver and indicates the prognostic significance of each (Jastrow, 1908). The liver was divided into about 50 portions for individual inspection in an effort to overlook as little as possible. Such hepatoscopy was widely in vogue over the following centuries and was practiced by the Etruscans, as evidenced by a bronze tablet in a museum at Piacenza depicting the liver, this being strikingly similar to the Babylonian clay tablet in the British Museum.

The Roman Celsus in his text De Medicina, translated by W.G. Spencer in 1935, mentioned the liver and described its anatomic location: “[T]he liver, which starts from the actual partition under the praecordia on the right side, is concave within (that is on the inferior surface) and convex without; its projecting part rests lightly on the stomach and it is divided into four lobes. Outside its lower part, the gallbladder adheres to it.” Celsus lived in the first century and described symptoms attributable to liver disease. Gallstones were recognized in the embalming of mummies in ancient Egypt. In 1909, a mummy with a preserved liver and a gallbladder containing 30 gallstones was presented to the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London. This mummy came from Deir-el-Bahn at Thebes and was that of a priestess of the twenty-first dynasty around 1500 bce. Elliot-Smith, an outstanding English anatomist and Egyptologist, described the gallbladder as being large and containing “many spherical calculi.” The specimen was destroyed by German bombs during World War II, but the description of it was accepted as evidence that the gallstones contained therein were the earliest specimen of such calculi to have survived from antiquity (Glenn, 1971). Gordon-Taylor, a noted surgical historian in England, had likewise called attention to the terminal illness of Alexander the Great at the age of 34 (323 bce) as an example of fatal biliary tract disease. The description of Alexander’s illness as recounted by Weigall (1933) suggests that he died of complications culminating in peritonitis.

Rhazes (850-923) and Avicenna (980-1037), two Persians, wrote on general surgical topics and the nature of disease and appreciated the gallbladder but lacked knowledge of the common bile duct. Biliary fistulae were known to have formed after the drainage of an abdominal wall abscess, and it was known that individuals with fistulae had a better prognosis than those who had an external communication with the intestines (Glenn, 1971).

Greek academic achievements surpassed that of all other civilizations until the fifth century bce. Hippocrates, widely acclaimed in medicine then and since that time, recognized the seriousness of biliary tract disease as evident in the following passage from The Genuine Works of Hippocrates (translated by Adams in 1939): “[I]n a bilious fever, jaundice coming on with rigor before the seventh day carries off the fever, but if it occurs without the fever, and not at the proper time, it is a fatal symptom.” He also noted that in the case of jaundice, “[I]f the liver hardens it is a bad sign.”

A few centuries after Aristotle recognized jaundice as an element of disease, Galen viewed biliary tract disease as a recognized clinical entity to be treated successfully in part by diet. Although Celsus had drawn attention to the gallbladder and liver in the first century ce, in the second century, Galen was the most noted author of the Greco–Roman age. Galen named three main organs that govern the body: the heart, the source of heat and the principal organ; the brain, the source of sensitivity for all parts; and the liver, as a principal part of the nutritive facility (Green, 1951). Galen considered jaundice to be due to yellow bile flowing into the skin and recognized that although jaundice could be the result of hepatic disease, it also could arise when the liver was not involved at all. Galen’s teaching persisted for centuries, and until the middle of the seventeenth century, many disorders were described as alterations in the balance of the main humors of the body brought about by hepatic dysfunction. As recorded by Rosner (1992), ancient Hebrew physicians used pigeons to treat jaundice by placing the pigeon on the patients umbilicus. “The pigeon will draw all yellowness out.”

Many subsequent advances came from Italy about the time of the Renaissance. Benivieni (1506) in Florence described a series of autopsies in his patients, which was the first record of special reference to biliary tract disease and its clinical manifestations. Two examples are cited in the translation by Singer and Long (1954) of Benivieni’s book, The Hidden Causes of Disease:

The second quotation also suggests death from gallstones:

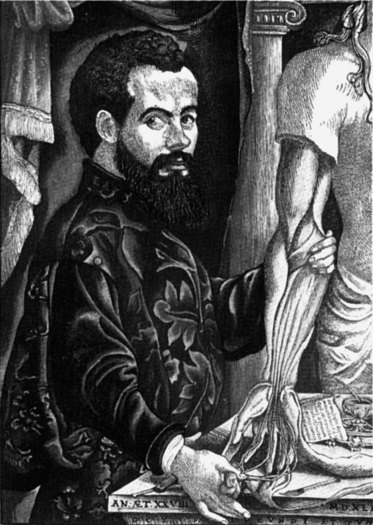

Much of the next phase of development of knowledge was centered around northeast Italy, particularly Padua, and many of the eponyms that we now use in surgery evolved from that period. The publication of Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543 (Fig. 1) and Harvey’s De Mortu Cordis 100 years later marked the emergence of a new scientific spirit in anatomy and physiology. As was the custom of the times, Vesalius often recorded descriptions of findings of dissections on individuals who had recently died and expressed an opinion on the cause of death. Rains (1964), in his treatise Gallstones—Causes and Treatment, stated “Vesalius found [that he had] a hemoperitoneum coming from an abscess, which had eroded the portal vein. The gallbladder was yellow and contained 18 calculi. Very light, of a triangular shape with even edges and surfaces everywhere, green by color somewhat blackish. The spleen was very large.” Similarly, Rains recounted that Falloppio described stones in the gallbladder and common bile duct in 1543, and that Fernell in his De Morbis Universilibus et Particularibus (1588) proposed that the predisposing cause of gallstone formation was stasis and observed that in jaundice, the feces become white and the urine dark, and that stones may be passed per anum. Falloppio, Vesalius, and Fernell all were active in the first half of the sixteenth century and probably discussed their theories of the cause of gallstones and the changes in the liver with which they were associated.

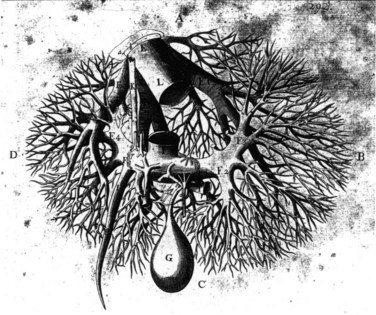

William Harvey (1578-1657), who also worked in Padua, is held by many to be the greatest of the contributors to the study of anatomy and physiology, and he established a clear understanding of the circulation. There is little doubt that Harvey also gave thought to the liver and its relation to the circulation and to the heart in particular. Harvey’s student and younger contemporary, Francis Glisson, investigated the structure and function of the liver extensively. His book Anatomia Hepatis was published in 1654 and is the first major modern work on hepatology. Glisson gave a clear description of hepatic anatomy, especially of the hepatic capsule and of the investment of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and bile duct. He described the fibrous framework of the liver and illustrated hepatic vascular and biliary anatomy on the basis of cast and injection studies (Fig. 2). Glisson was the first to mention a sphincteric mechanism around the orifice of the common bile duct (Boyden, 1936). He also deduced the flow of blood through the portal veins traversing the capillaries into the vena cava at a time when no microscopic studies of the liver had been done (Walker, 1966). Some of his illustrations are remarkably similar to those of Couinaud (1954, 1957, 1981) and to the images displayed today in three-dimensionally constructed computed tomography (CT) scans. Glisson was one of the great clinical physicians of all time, yet his name is related to an anatomic structure of limited importance.

In the century that followed the time of Harvey, great activity in publication among individuals engaged in medicine occurred. As today, senior professors often held opposing opinions and expressed their feelings based on fact or fancy with equal fervor. In an attempt to select the factual, Morgagni, senior professor of anatomy and president of the University of Padua, published in 1761 an analysis of disease (translated by Benjamin Alexander in 1960) under the title Seats and Causes of Disease, among which are those of the liver and biliary tract. In referring to gallstones, this text analyzed the distribution of stones in male and female patients, including the age, incidence, and treatment:

As outlined by Wood (1979), numerous eponyms currently used pertain to the names of these early physicians. Johann Georg Wirsung (1600-1643) also studied in Padua and was the first to dissect the human pancreatic duct and to describe it in a letter to Riola, professor of anatomy and botany at the University of Paris in 1642. Wirsung was subsequently murdered by a Dalmatian physician, the dispute probably related to who had described the duct first (Major, 1954; Morgenstern, 1965). Abraham Vater (1684-1751) was the first to describe the papilla of the duodenum. In 1720, he wrote that “those double ducts (bile and pancreatic ducts) … come together in single combination” (Boyden, 1936). He described not an ampulla but an elevation of the mucosa of the duodenum and described the first case of an ampulla with two orifices. Likewise, the duct of Santorini takes its name from the Venetian Giovanni Domenico Santorini (1681-1737), a brilliant anatomist and one of the most exact and careful dissectors of his day. While Vater was describing the tubercle at the confluence of the pancreatic and bile ducts, Santorini was relating the first detailed observation of the orifice of the two ducts (Boyden, 1936). In observations printed posthumously, Santorini noted a second pancreatic duct of normal occurrence and named the upper one the superior pancreatic duct and the lower one the main pancreatic duct. It was not until Oddi in 1864, working in Bologna, rediscovered “Glisson’s sphincter” and did studies in dogs that the holding quality of the sphincter of the outlet of the choledochus was recognized (Boyden, 1936).

Imaging in Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery

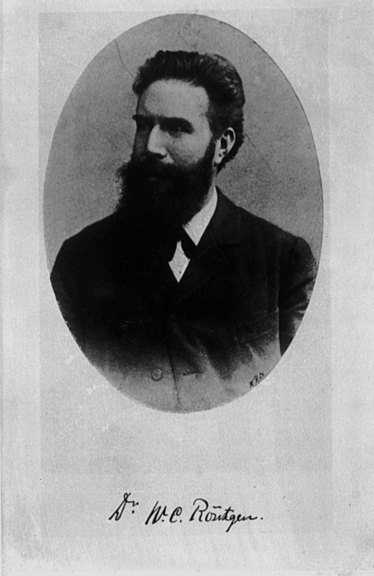

Following the discovery of x-rays by Roentgen (Fig. 3) in 1895, there have been continual important and extraordinary developments in radiology. A contemporary surgeon who examines images to determine the cause of disease, sometimes before taking a history or examining the patient, can hardly contemplate a time when precise imaging was not available. A landmark development in hepatobiliary imaging occurred when, after experimenting with various iodine compounds, Graham, a North American surgeon, developed oral cholecystography (Graham & Cole, 1924). Although biliary calculi had been observed by plain x-rays since 1898 (Buxbaum, 1898), the problem of detecting radiotransparent calculi was evident, and the development of oral cholecystography marked an important turning point. Postoperative cholangiography was soon developed by Mirizzi (1932) in Argentina. Intraoperative cholangiography (Mirizzi, 1937) and choledochoscopy (Bakes, 1923; McIver, 1941) also were developed.

In the 1970s, endoscopic cholangiopancreatography (McCune et al, 1968; Demling & Classen, 1970; Oi et al, 1970; Blumgart et al, 1972; Cotton et al, 1972a, 1972b) and endoscopic papillotomy (Classen & Demling, 1974) revolutionized biliary and pancreatic radiology and approaches to common bile duct stones. The 1970s saw not only the introduction of endoscopic approaches to the biliary tract but also the development of good methods for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (Ohto & Tsuchiya, 1969; Okuda et al, 1974), CT of the liver (Grossman et al, 1977), and the use of ultrasound (Bryan et al, 1977) in liver and biliary surgery. Magnetic resonance (MR) axial imaging (Damadian, 1971; Lauterbur, 1973) was conceived and has led to the development of magnetic resonance imaging cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Not only were endoscopic and transhepatic approaches to stones now possible, endoscopic and percutaneous transhepatic intubation of the biliary tree for the relief of jaundice and for dilation of strictures became a reality. Arteriography developed to a fine degree, so that good hepatic arteriography and portography were developed (Hemingway & Allison, 1988), which inevitably led to the development of techniques for hepatic artery embolization in the management of liver tumors and of hemobilia (Allison et al, 1977).

Surgery of the Biliary Tract and Pancreas

Biliary Tract

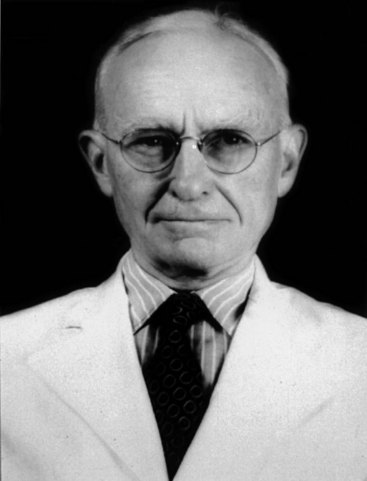

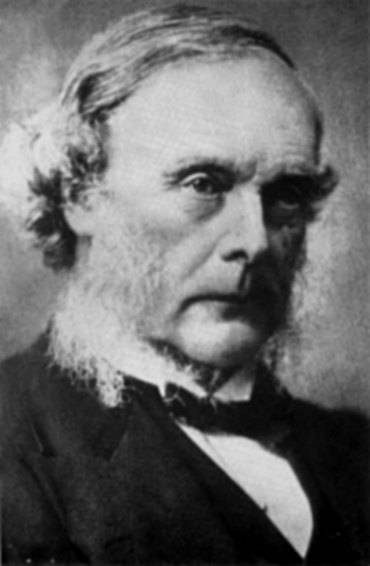

Biliary surgery began in Indiana on July 15, 1867, when John Bobbs operated on a woman who had a large tumor that he believed to be an ovarian cyst. To his amazement, when the abdomen was opened, he found an enormous gallbladder filled with stones. He opened it and extracted the calculi, sutured it carefully, and replaced it back in the abdomen (Bobbs, 1868). It was nearly a decade before a similar cholecystostomy was performed almost simultaneously by a Swiss, Theodore Kocher (Fig. 4), a North American, Sims, and an Englishman, Lawson Tait. All three surgeons planned operations in which the gallbladder was affixed to the abdominal wall to allow extraction of stones and pus and to leave it open to the exterior, so that peritonitis as a result of maneuvers within the abdomen could be avoided.

Sims worked on both sides of the Atlantic, and in Paris he operated on a patient with long-standing jaundice and a tumor in the right hypochondrium. With antiseptic technique, he opened the gallbladder and extracted 60 calculi then sutured the gallbladder to the abdominal wall; this was perhaps the first elective surgical procedure for obstructive jaundice (Sims, 1878). In the same year, in Bern, Switzerland, Kocher performed a cholecystostomy in two stages (Glenn, 1971). In the first stage, he packed the wound with gauze to the bottom of the gallbladder, and 8 days later, he emptied the residual stones from the gallbladder. Incidentally, Kocher, who won the Nobel prize in medicine in 1909 for his work on the physiology and surgery of the thyroid gland, also described sphincterotomy, or internal choledochoduodenostomy. His name is remembered by every biliary surgeon who performs mobilization of the duodenum as described by the great master (Kocher, 1903). Kocher originally described the maneuver for use in gastric surgery, but similar to so many other firsts in surgery at that time, the maneuver was first described by Jourdan (1895) and was first performed in biliary surgery by Vautrin (1896). Perhaps the maneuver should be referred to as “Vautrin’s maneuver” rather than Kocher’s. Tait, the great British surgeon, is given credit for performing the first cholecystostomy for gallbladder lithiasis in one stage. The patient, a 40-year-old woman, survived, and by 1884, he had performed the procedure in 14 cases with only 1 death (Tait, 1885).

The first elective cholecystectomy was done by Langenbuch (Fig. 5). While others were pursuing the construction of biliary fistulae and direct removal of gallstones, Langenbuch observed that because stones were known to recur, others had “busied themselves with the product of the disease, not the disease itself” (Langenbuch, 1882). As he was later to recount, two thoughts kept occurring to him: first, that in animal experiments, Zambeccari in 1630 and Teckoff in 1667 had performed cholecystostomy and cholecystectomy in dogs and had shown that the gallbladder was not essential to life (Langenbuch, 1896); second, that his medical colleagues believed that the gallbladder itself gave rise to stones. He developed the technique for cholecystectomy over several years of cadaver dissection and performed the operation at the Lazarus hospital in Berlin on July 15, 1882. The patient had had biliary colic for 16 years and was addicted to morphine. He was afebrile the day after the operation, had little pain, and was smoking a cigar; the patient was walking at 12 days and left the hospital 6 weeks later, pain free and gaining weight (Traverso, 1976). Report of this case (Langenbuch, 1882) led to a controversy over cholecystostomy as championed by Tait. Langenbuch’s operation was the new cholecystectomy.

In 1886, Gaston had tabulated 33 cholecystostomy operations with a mortality of 27% compared with 8 cholecystectomies (5 by Langenbuch) with 1 death recorded, a mortality of 12%. By 1890, 47 cholecystectomies had been done by 27 surgeons, and in 1897, the number had increased to nearly 100 operations with a mortality of less than 20% (Gaston, 1897).

The most important recent advance in surgery of the gallbladder came 100 years after Langenbuch’s first cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conceived and first performed in Germany by Muhe in 1985. Between 1985 and 1987, he performed 94 laparoscopic cholecystectomies (Muhe, 1986, 1991). Mouret in Lyon, France, performed the first video laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He did not publish his experience, but the news spread rapidly, and Dubois in Paris published the first series of laparoscopic cholecystectomies (Dubois et al, 1989, 1990). Perissat, working in Bordeaux, further developed the laparoscopic approach and introduced it to the United States in 1989 (Perissat et al, 1990). The procedure has since been extended, so that laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct is now possible and is routinely carried out. Today, most cholecystectomies are done using laparoscopic techniques, such that the modern surgical trainee often has little or no experience in open cholecystectomy. More recently, cholecystectomy has been done via minimally invasive techniques using robotics (Marescaux et al, 1998; Satava, 1999) to manipulate the instruments.

Not long after the performance of the first cholecystectomy, attempts were made to remove stones from the bile ducts. In 1898, Thornton performed the first removal of a stone from the common bile duct. A year later, Courvoisier operated successfully on another case of choledocholithiasis and published his well-known monograph on the pathology and surgery of the biliary ducts. He also enunciated the law that was to bear his name, which established that in cases of jaundice, if the gallbladder is not distended, the case is more likely to be one of stones. The operative procedure for exploration of the common bile duct for choledocholithiasis was not popularized, however, because of the risk of peritoneal infiltration of bile.

In 1897, Kehr (Fig. 6) performed the procedure and placed a rubber tube in the common bile duct through the cystic duct; this was the first systematic use of biliary intubation. Kehr’s name is properly associated with the development of biliary intubation; Kehr (1912) and Quenu and Duval (1908) were able to extract stones along the tunnels created by the drainage tubes. These were the precursors for techniques later developed by Mondet (1962) and Mazzariello (1966, 1974). Kehr had developed numerous combinations of drainage in patients with biliary stones, and many other surgeons rapidly developed choledochotomy without suture and using tube drainage.

Surgery of the bile ducts rapidly disseminated across Europe, England, and the United States, and in 1912, Kehr developed what came to be known as the T-tube. Not only was choledochotomy simplified, but biliary tract repair was done over these tubes. Kehr became justly famous for his introduction of biliary intubation and was probably the most outstanding biliary surgeon of his day. In 1913, he published a treatise entitled Surgery of the Biliary Tract, which for more than 40 years was the most respected text on the subject. Kehr (1908a, 1908b) described the resection of cancerous gallbladders, including hepatic resection, and he resected hepatic tumors and aneurysms of the hepatic artery. He also performed the first hepaticoenteric anastomosis.

Before the development of Kehr’s tubes, choledochotomies often became biliary fistulae, either because of residual supraampullary stones, or because the surgeon had inadvertently opened the bile duct proximal to a cancer. German and Austrian surgeons were the first to perform supraduodenal choledochoduodenostomy (Riedel, 1892; Sprengel, 1891). Sprengel’s operation described a side-to-side choledochoduodenostomy, and it subsequently became popular in Europe and the United States (Madden et al, 1965). Cholecystenterostomy also was developed initially by von Winiwarter (1882) and was used later by many surgeons, including Oddi (1888).

Transduodenal surgery was not long in developing. In 1895, Kocher wrote an article on internal choledochoduodenostomy to remove supraampullary choledochal calculi; by 1899 he had performed the operation 20 times. MacBurney (1898) published his experience with duodenostomy and papillotomy in patients with impacted periampullary calculi. These early procedures of a choledochotomy and choledochoenteric anastomosis for the treatment of jaundice and of stones in the biliary tract are still used today, with frequent application of the same principles but with the use of the endoscope.

At about the same time, surgeons began to operate on cancer of the papilla. In Baltimore in 1900, Halsted resected a portion of the duodenum that included a tumor and reimplanted the common duct, at the same time performing a cholecystostomy. He then reoperated to remove the gallbladder. Mayo (1901) reported an operation on a 49-year-old man with papillary cancer. Mayo opened the duodenum, removed the tumor, and carried out a choledochoduodenostomy. This was the first transduodenal ampullectomy. Kausch (1912) in Germany and Harmann (1923) in France gave accounts of resections of ampullary tumors. In Lausanne, Switzerland, Roux, a disciple of Kocher, had described preparation of a “jejunal loop” for use in gastric surgery, and it soon became an adjunct in biliary surgery (Roux, 1897). This Roux-en-Y procedure was soon used by Monprofit (1904) in the performance of cholecystojejunostomy, and he proposed it for hepaticojejunostomy at the French Congress of Surgery in 1908. Dahl (1909), in what he called “a new operation on the bile ducts,” was the first to advocate the Roux anastomosis in biliary surgery.

With the advent of cholecystectomy and choledochostomy came the inevitable sequelae of residual bile duct stones and iatrogenic lesions. Initially, these were treated by various forms of intubation, similar to the techniques advocated by Kehr, but many leading surgeons, such as Moynihan and Mayo, used hepaticoduodenal anastomoses (Estefan et al, 1977). Dahl (1909) used the Roux-en-Y loop, but more recently, other authors (Madden et al, 1965; Schein & Gliedman, 1981) have preferred choledochoduodenostomy as described previously.

Operative biliary drainage in upper biliary tract cancer and in patients with severe scarring in the porta hepatis is always difficult. Kehr (1913) successfully performed three operations in which he fixed a jejunal loop to a cut section of a hepatostomy wound; similar procedures were done by others, as cited by Praderi (1982). Longmire and Sanford (1948) performed a similar operation, resecting the end of the left lobe of the liver and anastomosing it to a jejunal loop. This technique, although popular for a short time, was complicated by stenosis and has fallen out of favor.

Goetze (1951) developed a procedure of transanastomotic drainage with a catheter that went through the hepatic parenchyma, the anastomosis, and the jejunal loop. Goetze’s contribution was apparently forgotten but was reinvented and popularized by others, including Praderi in 1962 (Praderi, 1982). Praderi argued strongly that Goetze’s procedure was the answer to difficult procedures in the high biliary tract but conceded that the development of transhepatic percutaneous cholangiography (Okuda et al, 1974) allowed for the development of transhepatic percutaneous methods for intubation and dilation of the biliary tract, which are now common procedures throughout the world.

The greatest advances in techniques for repair of biliary injuries came from two sources. At the Lahey clinic in the United States, three generations of famous surgeons headed by Lahey, Cattell, and Warren perfected the reconstruction of the common bile duct as an immediate or delayed procedure and splinted their anastomoses with a variety of tubes (Estefan et al, 1977). The results of these techniques were unsatisfactory, with numerous recurrent strictures. However, following the detailed study of the anatomy by Couinaud in France (1954), Hepp and Couinaud (1956) and Soupault and Couinaud (1957) developed techniques for direct biliary–enteric anastomosis, either to the left hepatic duct or to the segment III duct of the left liver. These surgical techniques have become widely accepted and are used throughout the world (Bismuth & Corlette, 1956; Bismuth et al, 1978; Voyles & Blumgart, 1982; Warren & Jefferson, 1973).

Pancreas

Like liver surgery, pancreatic surgery developed largely as a result of responding to wounds inflicted in wars. Claessen (1842), Ancelet (1866), Da Costa (1858), and Nimier (1893) documented the early development of pancreatic surgery. In 1923, Harmann wrote an extensive review of the French, German, and English literature. Early efforts at elective pancreatic surgery largely revolved around drainage of cysts (Thiersch, 1881). In 1883, Gussenbauer marsupialized a pancreatic pseudocyst, and the patient survived. Other surgeons, including Senn (1886), soon performed similar procedures.

Direct anastomosis of the pancreas to the gastrointestinal tract followed in the early part of the twentieth century, when Coffey (1909) performed an anastomosis of the tail of the pancreas to the small bowel. Ombredanne (1911) anastomosed a pancreatic cyst to the duodenum, and Jedlicka (1923) anastomosed a cyst to the posterior wall of the stomach. Chesterman (1943) performed a cystojejunostomy, and König (1946) carried out the same operation to a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum.

Operations for pancreatic tumors were being done at about the same time. Ruggi (1890) reported a resection of a large lesion of the tail of the pancreas, and Briggs (1890) performed a similar operation. Biondi (1897) reported resection of a tumor arising from the inferior part of the head of the pancreas, and the patient was still alive 18 months later.

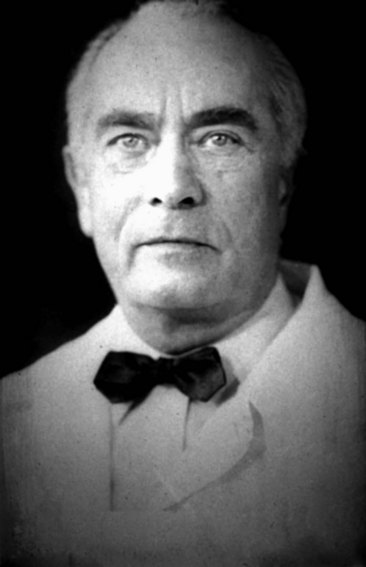

Whipple (Fig. 7) and associates (1935) published a technique for cephalic duodenopancreatectomy, done in two stages, for cancer of the ampulla of Vater. In the first operation, they performed a cholecystogastrostomy and gastroenterostomy. In the second and subsequent procedure, they resected the head of the pancreas with a portion of the duodenum without anastomosis to the stump of the pancreas, which they sutured. Whipple (1941) subsequently performed this operation in one stage and reported 41 cases with a mortality of 27%. Eventually, the technique of this operation was perfected. Although English-speaking surgeons throughout the world continue to call this operation “Whipple’s operation,” the procedure had been done many years before.

Sauve (1908) reviewed the literature on pancreatectomy and reported that several surgeons had resected small tumors from the head of the pancreas, and larger ones from the body of the organ, without touching the duodenum. Codivilla of Italy is reported to have resected the duodenum and head of the pancreas and performed a cholecystojejunostomy in 1898, but the patient died in the postoperative period. The first surgeon to perform cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy successfully was Kausch, a professor of surgery in Breslau and later in Berlin. On June 15, 1909, he performed a cholecystojejunostomy on a jaundiced 49-year-old man; on August 21, 1909, Kausch reoperated, performing a posterolateral gastroenterostomy and resection of the head of the pancreas with the tumor, the pylorus, and the first and second part of the duodenum. He anastomosed the third portion of the duodenum to the pancreatic stump. Kausch (1912) published a report entitled “Cancer of the Duodenal Papilla and Its Radical Treatment.” He gathered in that publication all reports that included excisions of the papilla. Tenani (1922) reproduced this operation with success, also in two stages but with one difference: Tenani performed a choledochojejunostomy, and the patient survived 3 years. Kausch and Tenani, although cited by Whipple (1941), are generally ignored in the English and American literature.

Resection later was extended to deal with cancers of the common bile duct and of the duodenum (cancers of the proximal bile duct are described subsequently in the section on liver surgery). Recognition of endocrine tumors of the pancreas later led to operations for these conditions. Wilder and colleagues (1927) reported the first case of resection of an insulinoma arising from the islet cells of the pancreas. Mayo operated on a patient in whom he found a tumor of the pancreas with metastases to the liver, and an extract from one of the metastases produced an insulin-type reaction when injected into a rabbit. Graham and Hartman (1934) reported subtotal pancreatectomy for hypoglycemia, and total pancreatectomy was performed by Priestley and colleagues (1944) for a patient in whom there was proven hyperinsulinism, but no tumor of the pancreas was to be found. The patient was cured by the operation, and the small tumor causing the syndrome was discovered during the pathologic examination.

Later, Fallis and Szilagyi (1948) performed total pancreatectomy for cancer, and this procedure was developed further in the hope that total removal of the gland would reduce morbidity and mortality and perhaps lead to better results. ReMine and colleagues (1970) and Brooks and Culebras (1976) adopted this approach, but early suggestions regarding efficacy were not fulfilled, and total pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer has largely been abandoned. Fortner (1973) described the even more extensive procedure of regional pancreatectomy. The operation included an extensive total pancreatectomy and resection of the pancreatic segment of the portal vein—and sometimes the hepatic and superior mesenteric arteries, if these vessels were invaded by tumor—together with subtotal gastrectomy and regional lymph node dissection. Fortner’s results have not been reproduced by others.

Surgery for pancreatitis also developed over the same period, and the severity of acute pancreatitis was recognized. Ockinczyc (1933) revealed the frustration of the times when he advocated “the use of drainage of the pancreas and hope.” Because the mortality of emergency surgery reached 78%, the conservative approach to acute pancreatitis was advocated. Nevertheless, some patients with acute pancreatitis still came to operation because of the necessity to treat gallstones and pancreatitis or to deal with complications, such as abscess and pseudocyst (Cattell & Warren, 1953).

The development of intensive care, antibiotics, and better metabolic management of patients with acute pancreatitis led to improvements in outcome, although the death rates remained unacceptably high. Ranson and colleagues (1976) and Imrie (1978) made important contributions in that they defined the evaluation of the severity of an attack. The surgical treatments of abscess and peritonitis were made systematic. The role of gallstones in acute pancreatitis was defined, particularly by Acosta and Ledesma (1974), and endoscopic papillotomy to extract calculi impacted at the papilla of Vater was also described.

Surgical procedures aimed at the treatment of chronic pancreatitis had been developing since the beginning of the twentieth century. As mentioned previously, Coffey (1909) had anastomosed the tail of the pancreas to a loop of jejunum, and in 1953, Link reported external drainage of a pancreatic duct in a patient who lived for a prolonged period but expelled calculi periodically from the fistula tract. Roget (1958) described 50 cases treated this way, but only a few patients were cured by drainage. Doubilet and Mulholland (1948) attempted sphincterotomy in the treatment of pancreatitis. As a result of the success of cystojejunostomy in the treatment of pancreatic pseudocyst mentioned earlier, Cattell in 1947 used a side-to-side anastomosis between a loop of jejunum and the pancreatic duct in an attempt to relieve pain in a patient with cancer of the head of the pancreas. Subsequently, Longmire and associates (1956) carried out end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy to a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum; however, this procedure proved unsuccessful. Du Val (1957) performed a similar operation in an attempt to drain the pancreatic duct, but this too was unsuccessful.

Leger and Brehand (1956) and von Puestow and Gillespy (1958) performed pancreatic ductal drainage in chronic pancreatitis patients for the relief of pain. Longitudinal opening of the pancreactic duct allowed better decompression after anastomosis to a jejunal loop. Mercadier (1964) performed a similar operation without the need for splenectomy, and further technical variations were introduced more recently by Prinz and Greenlee in 1981 and by Frey and Smith in 1987. Mallet-Guy (1952) and Mercadier (1964) performed resection of the left pancreas for chronic pancreatitis. This approach subsequently was extended, so that only a small portion of the head of the pancreas remained. A more modern approach aimed at conserving pancreatic parenchyma has since been developed (Beger et al, 1985) and was further promoted by Buchler and collegues (Di Sebastiano et al, 2007).

Liver Surgery

Liver surgery has evolved from being almost nonexistent to comprising a repertoire of operations that can safely remove nearly any amount of liver tissue (Chakravorty & Wanebo, 1987; Fortner & Blumgart, 2001). These operations are now performed at numerous hospitals and medical centers throughout the world. Courageous surgeons were enabled by extraordinary developments in anesthesiology, blood transfusion, infectious disease, and radiologic imaging.

Features of the anatomy and physiology of the liver that allow major resection were known in ancient times. The structural arrangement of the liver into lobes was apparent to individuals preparing animals for food or for ceremony or to those preparing humans for mummification. Two other properties of the liver, functional reserve and rapid regeneration, were suggested by the early Greek mythology of Prometheus, in which Prometheus’s liver grew back nightly after the eagle’s daily and apparently bloodless “resections.” This oft-cited myth does not necessarily mean that the ancient Greeks knew about liver regeneration; however, more recent evidence provides dramatic proof of the liver’s power to grow back rapidly (Blumgart et al, 1971).

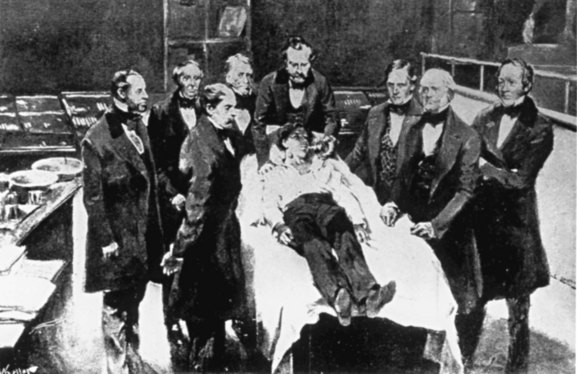

Early descriptions of operations on the liver usually concerned complete or partial avulsion of some portion that was protruding externally as a result of abdominal trauma. Berta in 1716 amputated a portion of liver protruding from the abdomen after a wound, and Von Bruns in 1870 (Beck, 1902) removed a lacerated part of the liver of a soldier wounded in battle. Despite these anecdotal descriptions, true hepatobiliary operations were not possible until the advent of anesthesia (Fig. 8) and antisepsis (Lister, 1867a, 1867b; Fig. 9). Although Warvi (1945) recounted that Couzins performed a liver resection in 1874, Langenbuch (1888) recorded the first planned hepatic resection in Germany. In the United States, Tiffany (1890) resected a liver tumor, and Lucke (1891) reported a liver resection for cancer. Keen (1899) in the United States reported 76 liver resections, of which 37 were for benign or malignant tumors.

About the time of these surgical developments, Rex (1888) and later Cantlie (1897a, 1897b) did detailed anatomic studies of the liver and its intrahepatic architecture. These studies established the lobar and segmental structure of the liver and of the Glissonian sheath enclosing structures that enter or leave the organ at the porta hepatis. They delineated the planes within the parenchyma of the organ that were relatively devoid of major blood vessels and bile ducts. These descriptions would make possible controlled hepatic resection.

Surgeons quickly learned to fear the liver’s friability and capacity for bleeding and its propensity for biliary leakage after operation. Elliot (1897) wrote that the liver is “so friable, so full of gaping vessels and so evidently incapable of being sutured that it seemed impossible to successfully manage large wounds of its substance.” Kousnetzoff and Pensky (1896) reported, however, passing ligatures in the liver substance at a sufficient distance from the margins of the wound to ensure that they would not slip, and reported that, by pulling these up tightly, it was possible to allow them to cut into the liver parenchyma and compress the blood vessels. In writing about surgical approaches for parenchymal transection of the liver and the arrest of bleeding during operations on the liver, Garre (1907) paid respect to Kousnetzoff and Pensky’s work, in which they had essentially shown that the vessels in human liver are no less resistant than arteries and veins of similar caliber in other parts of the body, and that they were suitable for ligature. These basic techniques for suture of the liver substance and ligation of vessels as a means of controlling hemorrhage have persisted to modern times and find recent application in the control of the pedicles of the liver within its parenchyma, as described by Ton (1979), and more recently in approaches to the control of the pedicles of the liver described by Couinaud (1954), Patel and Couinaud (1952a, 1952b), Takasaki and others (1986), and as developed and practiced by Launois and Jamieson (1992). Although ligatures and suture ligation remain the basic mainstays for the control of intrahepatic vessels, stapling techniques are now used for the same purpose (Fong & Blumgart, 1997).

Garre (1907) described the use of Doyen’s elastic stomach clamp to provide compression of the liver before it is transected, and he referred to the work of Masnata and Lollini in Bologna, who used a similar clamp. This method also has been used more recently by Storm and Longmire (1971) and Balasegaram (1972a, 1972b). Although almost totally abandoned in recent times, such clamps still are occasionally employed. Garre (1907) mentioned attempts to provide perforated plates to be used on either side of a wound of the liver, through which sutures could be passed to allow compression of liver tissue and bleeding vessels. This technique also was conceived more recently for the management of bleeding after elective liver resection (Wood et al, 1976) and for the control of bleeding from liver injury (Berne & Donovan, 2000).

Garre (1907) also emphasized the use of packing bleeding hepatic wounds, and he advocated that packing ought to be considered more frequently in cases of injury; this, too, was prophetic. Having passed through the phases of vascular ligation and hepatic resection for wounds of the liver, modern surgeons now rely much more frequently on packing to control oozing and hemorrhage for ragged and exposed liver lacerations (Berne & Donovan, 2000). The use of such packing recognizes, but does not specifically state, that major hemorrhage in the liver does not usually occur from the cut surface of the parenchyma but rather occurs from the main hepatic veins or lacerations to the vena cava.

In a seminal contribution in 1908, Pringle described a method of temporarily compressing the portal inflow vessels so as to reduce liver bleeding, but all eight patients he described died during surgery or shortly thereafter. Later, Pringle described the method as being uniformly successful in animals and used the technique successfully on a patient. This technique has been used ever since to control hepatic inflow, and although initially used to occlude the inflow for periods of 1 hour or more, it is now employed in an intermittent fashion.

Major Hepatic Resection

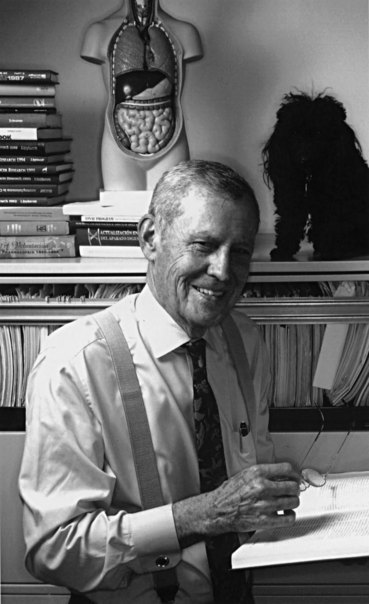

Wendell (1911) was the first to perform a successful right hepatic lobar resection using hilar ligation. Nevertheless, his achievement was lost to his colleagues for many years, and it was not until the detailed anatomic studies of Hjortsjo in 1951, Healey and Schroy in 1953, and Couinaud in 1954 that the concept of segmental anatomy as originally described by Rex and Cantlie was finally accepted. Couinaud’s (Fig. 10) seminal work in 1954 simplified the understanding of segmental liver anatomy and made it easily applicable by numbering the liver segments I through VIII. Goldsmith and Woodburne (1957) used a different nomenclature but subdivided the liver similarly. Subsequent refinements in the description of the liver were offered by Couinaud (1981) in a monograph, which contributed greatly to the understanding of practical surgical anatomy.

In 1950, Honjo published a case of anatomic right hepatectomy; the operation was performed in Kyoto, Japan, on March 7, 1949, and was later reported by Honjo and Araki (1955) in English. In 1952, Lortat-Jacob (Fig. 11) and Robert performed a true anatomic liver resection with preliminary vascular control. These reports opened the way for the development of liver surgery. Lortat-Jacob’s operation captured much attention, and many further case reports followed. As recounted by Fortner and Blumgart (2001), at the Southern Surgical Association’s meeting in the United States on December 10, 1952, Quattlebaum (1953) described a right hepatic lobectomy for hepatoma. The operation had been done about 4 months after that of Lortat-Jacob and Robert. Apparently unaware of Quattlebaum’s achievement, and thinking he would be the first to do a so-called right hepatic lobectomy in the United States, Pack at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center in New York performed the operation on a 40-year-old woman on December 14, 1952 (Pack et al, 1955).

Pack and colleagues (1962) recognized quickly the opportunity to study liver regeneration. Their studies were the first to describe and document regeneration of the human liver after major resection and suggested that complete regeneration occurs over 3 to 6 months. Later, Lin and Chen (1965) studied metabolic function and regeneration of the cirrhotic liver and found no discernible regeneration after resection. Blumgart and colleagues (1971) described the speed of liver regeneration as recovery of liver size within 10 to 11 days after major hepatic resection for trauma.

Contrary to the trends toward anatomic precision, Lin (1958) advocated a finger-fracture technique for liver resection, removing a hepatic lobe in 10 minutes with an average of 2000 mL of blood replacement. The surgical bluntness of this approach and the absence of the customary surgical principles and techniques precluded widespread acceptance of the technique. Similarly, a prominent figure in the early development of liver surgery, Brunschwig (1953; Serrea & Brunschwig, 1955) advocated nonanatomic resection, but his results—with a very high operative mortality for so-called simple right lobectomy, mostly from uncontrolled hemorrhage—led him to accept the approach of Lortat-Jacob. Brunschwig’s report of long-term survivors after hepatic resection for advanced cancer challenged the prevailing skepticism about resecting liver tumors.

The laparothoracotomy approach of Lortat-Jacob and Robert in 1952 quickly became the standard for major hepatic resection. Opening the chest added operating time and increased morbidity but gave needed exposure to the liver. Later, the introduction of costal arch retractors made thoracotomy extension obsolete for most hepatic resections. Steps generally considered unnecessary, such as T-tube drainage of the common bile duct, were eliminated in the 1970s. Opinions were divided in the 1970s and 1980s about the superiority of either intrahepatic or extrahepatic management of the major hepatic veins. Closed drainage was substituted for multiple Penrose drains and packing, although these were still advocated by some in the 1980s. Many hepatic resections have been done without drainage, as described by Franco and associates (1989) and subsequently at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (Fong et al, 1996).

Methods for anatomically based segmental liver resection that conserves parenchyma were developed and have proved valuable in hepatic resection for tumor. Numerous methods to transect the liver parenchyma had been advocated, including the knife handle (Quattlebaum, 1953), nitrogen knife (Serrea & Brunschwig, 1955), electrocautery (Fortner et al, 1978), microwave tissue coagulator (Tabuse, 1979), waterjet (Papachristou & Barters, 1982), ultrasonic aspiration dissector (Hodgson & DelGuercio, 1984), and harmonic scalpel; other techniques are described on an almost daily basis, and simple crushing of the liver tissue remains in use by many.

Bleeding has remained a problem in many cases, and preliminary vascular control is difficult or impossible in some clinical settings. Inflow occlusion using the Pringle maneuver for longer than 15 to 20 minutes was considered hazardous. Local and general hypothermia was used in an effort to increase the liver’s tolerance of the presumed ischemic anoxia associated with the procedure (Longmire & Marable, 1961). More complete vascular control was obtained by Heaney and colleagues (1966), without hypothermia, by employing aortic cross clamping and temporary occlusion of the porta hepatis and vena cava for 24 minutes without ill effect. Fortner and colleagues (1971) described isolation-hypothermic perfusion of the liver, making prolonged vascular isolation for complicated resections possible. Huguet and associates (1978) challenged the long-held belief that the liver could tolerate only 15 to 20 minutes of normothermic perfusion by extending the period to 65 minutes. This observation was subsequently confirmed (Bismuth et al, 1989; Huguet et al, 1992, 1994). As described previously, however, major bleeding during liver resection usually arises from the major hepatic veins or vena cava, and development of techniques of low central venous pressure anesthesia during liver resection, as first described by Blumgart and colleagues (Cunningham et al, 1994, Melendez et al, 1998), have proved simple and efficacious and have rendered vascular isolation techniques rarely necessary (Jarnagin et al, 2002).

Apart from hepatic resection, many other techniques for the enucleation of tumors and of hydatid cysts have been developed. Garre (1907) had first noted that if he kept close to the line of the dense membrane around hydatid cysts—so as not to enter the tissues of the liver too deeply, where large vessels may be encountered—it was possible to resect such lesions with minimal blood loss. Enucleative techniques are now used by contemporary surgeons, not only for the removal of hydatid cysts but also for the enucleation of giant hemangiomata (Baer et al, 1992; Blumgart et al, 2000; Hochwald & Blumgart, 2000). As described in this book, enucleation also may be used for resection of certain neoplasms of the liver, such as fibronodular hyperplasia.

The widespread use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy led to the development of techniques for laparoscopic resection of the liver. First used by Gagner and colleagues (1992), laparoscopic partial hepatectomy has been used by many surgeons. Ferzli and colleagues (1995) and Azagra and colleagues (1996) developed the operation for anatomic resection of the left lateral segment, and most operations have involved this procedure. More recently, major hepatectomy has been performed using laparoscopic techniques. Experience is limited, however, and the indications and place of laparoscopic liver resection are under active investigation.

Liver Tumors

The management of liver tumors has a relatively short history. After the initial reports of hepatic resection for tumors performed by Langenbuch (1888), Tiffany (1890), Lucke (1891), and Keen (1899), no significant reports were published until Foster’s review in 1970 of a multiinstitutional survey conducted on 296 adults who had liver resection for primary cancer and were followed for at least 5 years or until death. The operative mortality rate was 24%. Foster also studied the records of 115 patients who had had hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Operative mortality was 17.3%, and 21% survived for at least 5 years. Hemorrhage during operation was still a problem, and the operative mortality rate was essentially the same or higher than the cure rate so that skeptics remained unconvinced.

In the 1970s, major hepatic resection for tumors became more frequent, and this coincided with improvements in anesthesia, surgical technique, postoperative support, and significantly with the development of better imaging modalities. In the United States, Wilson and Adson (1976), Fortner and colleagues (1974), and Thompson and colleagues (1983) were major figures in this area of endeavor. In Asia, Ong (1977) and others were early explorers in the field, and other major centers made significant technical improvements with encouraging results (Attiyeh et al, 1978; Cady et al, 1979; Starzl et al, 1975).

Morbidity and mortality rates decreased dramatically, and major centers began to provide encouraging preliminary long-term survival figures. As described by Fortner and Blumgart (2001), by the 1980s, the early reluctance by many surgeons to accept the therapeutic benefit of hepatic resection for tumors faded before the onslaught of encouraging reports from a variety of institutions in the United States, Europe, and Southeast Asia.

Methods for limiting the extent of the parenchymal transection developed along with the emergence of surgical resection for tumors in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic livers. Although suggested originally by Pack and Miller (1961) and by McBride and Wallace (1972), Asian and European surgeons soon assumed a leadership role in developing isolated segmental resection and described various operations (Bismuth et al, 1982; Hasegawa et al, 1989; Scheele, 1989; Ton, 1979). The development of reliable intraoperative ultrasound allowed further developments in liver resection (Bismuth et al, 1982; Makuuchi et al, 1985), and subsegmental resection was developed. More recently, the segmental approach was reported and popularized in the United States, particularly by Blumgart and others (Billingsley et al, 1998; DeMatteo et al, 2000). The difficulty of the approach to the caudate lobe was addressed, and the surgical anatomy and technique for caudate resection, either as an isolated segment (Lerut et al, 1990) or in combination with major resections, was described by Blumgart and colleagues (Bartlett et al, 1996).

Probes to perform cryosurgical ablation were developed (Ravikumar & Kaleya, 2000), and cryosurgery-assisted segmental resection has been described (Polk et al, 1995). Radiofrequency ablation for liver tumors also has been evaluated (Curley et al, 1999; Wood et al, 2000). In the future, surgeons may perform controlled tumor ablation or hepatic resection for tumors using robotic techniques and refinements in the development of virtual reality techniques (Marescaux et al, 1998; Satava, 1999). Image-guided surgery opens great possibilities for developments in hepatic surgery in the future.

Primary liver cancer (HCC) occurs mainly in areas where viral hepatitis is endemic. Because of the prevalence of hepatitis B infection in Southeast Asia, most of the initial, significant, published experiences examining the treatment of primary HCC are from Southeast Asia. Improved diagnostic and surgical approaches in Japan permitted the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (1990) to report a 5-year survival rate of 57.5% for HCC; a high proportion of the cases were small, encapsulated tumors. From China, Tang (1993) reported a 5-year survival rate of 40.2%.

In the West, experience with HCC differed from that reported in the East in material ways: tumors were generally large at presentation, the incidence of viral hepatitis was much lower, and many patients did not have underlying cirrhosis. There were several reports of surgical mortality rates for hepatic resection in cirrhotic patients, ranging from 15% to 100%. In recent years, spread of hepatitis B and hepatitis C has changed the demographics of the disease in the United States and in Western Europe. This change has allowed a much greater surgical experience, and better techniques and improved patient selection have led to vastly improved results. Blumgart’s group (Fong et al, 1999) reported a mortality rate of 5% in 100 resections, 57 being major resections, in patients with HCC and cirrhosis, and a 5-year survival of 37% was reported among patients operated on since 1990.

Today the surgical mortality rate in noncirrhotic patients, even for the most extensive resections, is uniformly less than 5% in major centers. The overall 5-year survival is approximately 35% in patients with HCC reported from Western series, in which small HCC is relatively rare (Bismuth et al, 1986; Ringe et al, 1991). In a study reported by Blumgart and others (Fong et al, 1999), patients who had HCC with a median tumor size of 10 cm but no cirrhosis had hepatic resection with a surgical mortality of 3.7% and a 5-year survival of 42%. Although survival rates have not changed substantially, a great improvement has been seen in morbidity and mortality.

The treatment of metastatic liver tumors by hepatic resection was viewed initially as highly dubious. Many regarded the removal of tumor from the liver by hepatic resection as an irrational approach. The natural history of colorectal cancer offered the opportunity for resection of liver metastases more often than any other cancer in Western countries. The multiinstitutional report from Foster (1970) in the United States suggested a 5-year survival rate of 25%, and multiple other reports supported that view. However, the question remained: How long could patients have lived without surgical operations?

A landmark article from Glasgow (Wood et al, 1976) described the natural history of colorectal hepatic metastases. It was shown that survival depended on the extent of the disease, and that multiple bilobar metastases indicated a much more serious prognosis than single or multiple nodules on one side of the liver. In Wood’s study, only one patient survived for 5 years (1%). It was clear that if the operative mortality declined, as it had in many reported series, the issue was closed. A major study from Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (Fong et al, 1999) described the results in 1,001 consecutive patients with a 5-year overall survival of 37% and an operative mortality rate of 3.4%. Five-year survival reached more than 50% in patients with favorable prognostic factors. Tumor recurrence with the liver being the only site of recurrence is common, and such hepatic recurrences are often amenable to repeated resections, with risks and results similar to those of the initial operation (Elias et al, 1992; Fong et al, 1994; Scheele & Stangl, 2000).

More recently the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Group reported 1,600 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated since 1985 (House et al, 2010) and showed an improvement of results over time with results between 1999 and 2004 showing a 5-year survival of 51% in 563 patients, who had an operative mortality of only 1%.

Pichlmayr and colleagues (1990) did the first ex situ tumor resection on the liver, removing the liver for bench surgery, then autotransplanting it back into the patient. The liver was preserved by hypothermic perfusion, as had been described earlier for the in situ procedure (Fortner et al, 1974). This approach may prove to have merit in highly selected cases, but it has not been accepted generally.

Although initially completely ineffective, systemic chemotherapy improved dramatically with the development of new agents, and its use as a neoadjuvant agent and as adjuvant chemotherapy after resection has been extensively explored. The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to convert unresectable tumors to resectable ones was reported by Bismuth and colleagues (1996), and extensive studies were reported regarding the possible benefits of chemotherapy after hepatic resection using hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy (Kemeny et al, 1999). Kemeny’s study followed the demonstration in 1982 by Ensminger and colleagues of an implantable pump for hepatic arterial infusion therapy. Others have studied regression of advanced refractory cancer in the liver using isolated hepatic perfusion chemotherapy (Alexander et al, 2000).

As described in this book, hepatic resection also has been shown to yield satisfactory results in terms of relief of symptoms and prolonging of life in the management of hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine cancer and sarcoma. Hepatic resection for biliary and gallbladder cancer also has developed in a remarkable fashion. Launois and associates in France (1979) reported the first major series of patients in whom hepatic resection was performed to ensure clearance of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Working contemporaneously, Fortner and colleagues (1976) and Blumgart and Beazley and associates (Beazley et al, 1984; Blumgart et al, 1984) reported similar results, and in some patients, hepatic resection was accompanied by resection of the portal vein and portal venous reconstruction (Blumgart et al, 1984). Multiple other reports have confirmed that hepatic resection offers advantages in the management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma and helps achieve negative tumor margins and that this is associated with long-term survival (Hadjis et al, 1990; Jarnagin et al, 2001; Klempnauer et al, 1997; Nimura et al, 1990). Surgeons in Southeast Asia and Japan have contributed considerably in this area and in particular have contributed to the development of caudate lobe resection and vascular reconstruction (Mizumoto & Suzuki, 1988; Nimura et al, 1990).

Pack and colleagues (1955) advocated a similar radical approach for gallbladder cancer. They believed that an extended right hepatic lobectomy had its greatest applicability for gallbladder cancer, and they recommended an en bloc lymph node resection of the porta hepatis to be included with the operation. Brasfield (1956) reported a microscopic focus of metastatic cancer in a patient without gross liver involvement and helped establish the need for hepatic resection for gallbladder cancer. More recent reports indicate that for more invasive lesions and for patients seen after initial cholecystectomy, at which cancer was inadvertently found, an extensive resection seems to be effective (Fong et al, 2000). Fortner and colleagues (1970) performed total hepatectomy and orthotopic liver transplantation in two such patients with short-term survival.

Tumor ablation has been a major feature of the recent history of liver surgery for tumors. Cryosurgery (Adam et al, 1997; Crews et al, 1997; Zhou et al, 1988) has been used for treatment of small tumors and for the management of recurrent disease after resection or for the management of unresectable tumors in combination with chemotherapy. More recently, radiofrequency ablation of tumors has been developed, and its use in primary and metastatic cancer has been reported (Curley et al, 1999; Wood et al, 2000). This technology is still being explored, but it seems to have limitations similar to those of cryosurgery in that tumor cell necrosis is inadequate, particularly when the tumor is located close to large blood vessels. The technique can be used percutaneously, but as with cryosurgery, local recurrence remains a problem.

Ethanol injection has been used in the management of small HCCs (Ebara et al, 1990; Tanikawa, 1991). It is of particular interest because it is inexpensive, widely available, and easily used with a low complication rate even in poor-risk patients, and it can be repeated frequently. Hepatic arterial embolization can also be used to ablate tumors and may be particularly effective in primary HCCs and in metastatic tumors arising from primary neuroendocrine sources (Allison et al, 1977; Allison, 1978).

Liver Transplantation

Starzl (2001) has provided a fascinating overview of the origins of clinical organ transplantation. A historical consensus development conference was convened in March 1999 at the University of California, Los Angeles, to identify the principal milestones leading to the clinical use of various transplantation procedures; the conclusions were published in the July 2000 issue of the World Journal of Surgery (Groth & Longmire, 2000). The early history of the evolution of organ transplantation followed the first convincing evidence that organ rejection is a host-versus-graft immune response (Gibson & Medawar, 1943; Medawar, 1944). For further details, the reader is referred to the publications of Starzl (2001) and of Murray and Hills (2005). This portion of the review of the history of liver surgery is concerned with the history of liver transplantation.

In a magnificent leap forward, Starzl (Fig. 12) and associates (1968) in the United States did the first successful total hepatectomy with orthotopic liver transplantation. Calne and Williams (1968) in the United Kingdom reported similar studies. The contributions of both groups to the development of liver transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy have been monumental. Fortner and colleagues (1970) reported the first successful heterotopic (auxillary) liver homograft. This contribution was the forerunner of the further development of heterotopic liver transplantation and of split-liver and living related-donor transplants. Liver transplantation underwent continued evolution despite the only modestly effective immunosuppressive therapy initially available. One-year survival rates slowly reached 50% by 1979 (Calne & Williams, 1979; Starzl et al, 1979). Chronic infection, rejection, and surgical infections diminished the small group to only a few long-term survivors. The report in 1979 of immunosuppression with cyclosporine by Calne and associates (1979) transformed the field rapidly. A consensus conference held in 1983 declared that liver transplantation was now an acceptable therapy and no longer an experimental procedure. Zeevi and colleagues (1987) reported on another powerful immunosuppressive agent, tacrolimus.

Serious complications of immunosuppressive therapy for liver and other organ transplants have been described, including de novo malignancy (Penn, 1988; Penn & Brunson, 1988; Penn & Starzl, 1972). In 1988, Iwatsuki and associates reported an overall 54% survival of patients at 5 years. Development was rapid, and by 1992, more than 3,000 orthotopic liver transplantations were done annually in the United States (United Network for Organ Sharing).

Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation were initially disappointing for liver cancer. Iwatsuki and colleagues (1988) reported that three of every four patients who lived at least 2 months after transplantation for cancer had recurrence, and adjuvant chemotherapy had no demonstrable benefit. Ringe and associates (1989) reported a 5-year survival of 15.2% for such patients, and Calne and colleagues (1986) had similar results. The best results and apparent cure were obtained when a cancer was an incidental finding in a liver removed for noncancerous disease (e.g., alcoholic cirrhosis). Geevarghese and associates (1998) reported an 1-year survival of 85% and a 5-year survival of 78% for such cases.

Current adjuvant chemotherapy may improve the results. Olthoff and colleagues (1995) reported a 3-year survival of 45% using fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cisplatin, but only three survivors had cancers larger than 5 cm. Laine and associates (1999) reported five children with advanced hepatoma who were alive at a mean of 4.6 years after transplantation preceded by induction chemotherapy.

Improved immunosuppression has allowed surgical techniques to blossom. Bismuth and Houssin (1984) reported reduced-size orthotopic liver grafts in children, and Pichlmayr and colleagues (1988) reported the use of one donor liver for two recipients (split-liver transplantation). Raia and associates (1989), in a letter to the Lancet, and Strong and colleagues (1990) were the first to report living-donor liver transplantation using segments II and III of the liver; Yamaoka and colleagues (1994) reported using the right lobe of the liver. Use of split-liver grafts and living, related donors for grafts of both the right and left lobes has been driven by cultural restrictions and by a shortage of donor organs. This has been a major development, and the potential for mortality and morbidity not only of recipients but also of the live donors has remained a major ethical concern.

Liver transplantation for tumors has evolved considerably in the field of primary HCC. Although liver resection remains the treatment of choice for HCC in patients with good liver function, similar patients with compromised liver function and patients with hepatitis C and a small tumor in a portion of the liver geographically unfavorable for resection are now considered best treated by liver transplantation. Liver transplantation has come to be a recognized therapy for many patients with small HCCs (Bismuth et al, 1999), a wide range of benign disease, and in particular for patients with compromised liver function as a result of cirrhosis of the liver, Budd–Chiari syndrome, polycystic liver and kidney disease, sclerosing cholangitis, and for patients with a wide variety of other parenchymal and metabolic liver diseases. Liver transplantation for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma is under investigation and is occasionally indicated for patients with widespread neuroendocrine metastatic disease of the liver. Patients with metastatic disease from adenocarcinoma have had poor results, and transplantation is no longer used for this indication.

In writing this historical account, I have drawn freely on the work of the following excellent publications: Chakravorty and Wanebo (1987), Glenn (1971), Praderi (1982), and Starzl (2001). I have no doubt that there will be some inaccuracies and disputed claims as to “firsts,” but I have attempted to relate a fascinating surgical story. I apologize for any disagreement I may ignite.

Acosta J, Ledesma C. Gallstone migration as a cause of acute pancreatitis. J Med. 1974;270:484.

Adam R, et al. Place of cryosurgery in the treatment of malignant liver tumors. Ann Surg. 1997;225:39.

Adams F. The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1939.

Alexander B. Translation of Seats and Causes of Disease, Facsimile of London, 1769 edition. New York: Hafner; 1960.

Alexander HRJr, et al. Current status of isolated hepatic perfusion with or without tumor necrosis factor for the treatment of unresectable cancers confined to liver. Oncologist. 2000;5:416-424.

Allison DJ. Therapeutic embolization. Br J Hosp Med. 1978;20:707-715.

Allison DJ, et al. Treatment of carcinoid liver metastases by hepatic-artery embolisation. Lancet. 1977;2:1323-1325.

Ancelet E. Étude sur les Maladies du Pancréas. Paris: Savy; 1866.

Attiyeh FF, et al. Hepatic resection for metastasis from colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21:160-162.

Azagra JS, et al. Laparoscopic anatomical left lateral segmentectomy: technical aspects. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:758-761.

Baer HU, et al. Enucleation of giant hemangiomas of the liver: technical and pathologic aspects of a neglected procedure. Ann Surg. 1992;216:673-676.

Bakes J. Die Choledochopapilloskopie. Arch Klin Chir. 1923;126:473-483.

Balasegaram M. Hepatic surgery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1972;17:85-89.

Balasegaram M. Hepatic surgery: a review of a personal series of 95 major resections. Aust N Z J Surg. 1972;42:1-10.

Bartlett D, et al. Complete resection of the caudate lobe of the liver: technique and results. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1076-1081.

Beazley RM, et al. Clinicopathological aspects of high bile duct cancer: experience with resection and bypass surgical treatments. Ann Surg. 1984;199:623-636.

Beck C. Surgery of the liver. J Am Surg Assoc. 1902;78:1063.

Beger HG, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1985;97:467-473.

Berne TV, Donovan AJ. Liver and bile duct injury. In: Blumgart, LH, Fong, Y. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:1277-1301.

Berta, 1716, cited by Chen TS, Chen PS, 1984: Understanding the Liver: A History. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, p 293.

Billingsley KG, et al. Segment-oriented hepatic resection in the management of malignant neoplasms of the liver. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:471-481.

Biondi G. Contributo clinico e sperimentale al achirurgia del pancreas. Clin Chir. 1897;5:132.

Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy: an operation for biliary obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 1956;36:849-863.

Bismuth H, Houssin D. Reduced-sized orthotopic liver graft in hepatic transplantation in children. Surgery. 1984;95:367-370.

Bismuth H, et al. Long-term results of hepaticojejunostomy Roux-en-Y. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:161-167.

Bismuth H, et al. Major and minor segmentectomies “réglées” in liver surgery. World J Surg. 1982;6:10-24.

Bismuth H, et al. Liver resections in cirrhotic patients: a Western experience. World J Surg. 1986;10:311-317.

Bismuth H, et al. Major hepatic resection under total vascular exclusion. Ann Surg. 1989;210:13-19.

Bismuth H, et al. Resection of nonresectabnle liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509-522.

Bismuth H, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:311.

Blumgart LH, et al. Observations on liver regeneration after right hepatic lobectomy. Gut. 1971;12:922-928.

Blumgart LH, et al. Endoscopy and retrograde choledochopancreatography in the diagnosis of the jaundiced patient. Lancet. 1972;2:1269-1273.

Blumgart LH, et al. Surgical approaches to cholangiocarcinoma at confluence of hepatic ducts. Lancet. 1984;1:66-70.

Blumgart LH, et al. Liver resection for benign disease and for liver and biliary tumors. In: Blumgart, LH, Fong, Y. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:1639-1715.

Bobbs J. Case of lithotomy of the gallbladder. Trans Med Soc Indiana. 68, 1868.

Boyden E. The pars intestinalis of the common bile duct, as viewed by the older anatomists (Vesalius, Glisson, Bianchi, Vater, Haller, Santorini et al). Anat Rec. 1936;66:217.

Brasfield RD. Prophylactic right hepatic lobectomy for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 1956;91:829-832.

Briggs E. Tumor of the pancreas, laparotomy, recovery. St Louis Med Surg J. 1890;58:154.

Brooks JR, Culebras JM. Cancer of the pancreas: palliative operation, Whipple procedure or total pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 1976;131:516.

Brunschwig A. Surgery of hepatic neoplasms, with special reference to secondary malignant neoplasms. Cancer. 1953;6:725-742.

Bryan PJ, et al. Correlation of CT, gray scale ultrasonography, and radionuclide imaging of the liver in detecting space-occupying processes. Radiology. 1977;124:387-393.

Buxbaum A. Über die Photographie von Gallensteinen in vivo. Wein Med Presse. 1898;39:534.

Cady B, et al. Elective hepatic resection. Am J Surg. 1979;137:514-521.

Calne RY, Williams R. Liver transplantation in man: I. observations on technique and organization in five cases. BMJ. 1968;4:535-540.

Calne RY, Williams R. Liver transplantation. Curr Probl Surg. 1979;16:1-44.

Calne RY, et al. Cyclosporin A initially as the only immunosuppressant in 34 recipients of cadaveric organs: 32 kidneys, 2 pancreases, and 2 livers. Lancet. 1979;2:1033-1036.

Calne RY, et al. Liver transplantation in the adult. World J Surg. 1986;10:422-431.

Cantlie J. On a new arrangement of the right and left lobes of the liver. J Anat Physiol. 1897;32:iv-ix.

Cantlie J, 1897: Proc Anat Soc Great Brit Ire 32:4-9.

Cattel RD. Anastomosis of the duct of Wirsung: its use in palliative operations for cancer of the head of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am. 1947;27:636-643.

Cattell RB, Warren W. Surgery of the Pancreas. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1953.

Celsus AC. De Medicina, Loeb Classical Library ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1935.

Chakravorty RC, Wanebo HJ. Historic preamble: liver and biliary cancer. In: Wanebo, HJ, editor. Science and Practice of Surgery, vol 8, Hepatic and Biliary Cancer. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1987:xiii-xxvii.

Chesterman JT. Treatment of pancreatic systs. Br J Surg. 1943;30:234.

Claessen F. Krankheiten der Bauchspeicheldruse. Cologne, Germany: Schauberg; 1842.

Classen M, Demling L. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of Vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author’s transl). Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497.

Codivilla A, 1898: Rendiconto statistico della sezione chirurgica dell’ospedale di Imola.

Coffey RC. Pancreato-enterostomy and pancreatectomy: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1909;50:1238.

Cotton PB, et al. Endoscopic trans-papillary radiographs of pancreatic and bile ducts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1972;19:60-62.

Cotton PB, et al. Cannulation of papilla of vater via fiber-duodenoscope: assessment of retrograde cholangiopancreatography in 60. patients. Lancet. 1972;1:53-58.

Couinaud C. Bases anatomiques des hepatectomies gauche et droite réglées. J Chir. 1954;70:933-966.

Couinaud C. Le Foie: Étude Anatomique et Chirurgicale. Paris: Masson; 1957.

Couinaud C. Controlled Hepatectomies and Controlled Exposure of the Intrahepatic Bile Ducts: Anatomic and Technical Study. Paris: Author; 1981.

Crews KA, et al. Cryosurgical ablation of hepatic tumors. Am J Surg. 1997;174:614-617.

Cunningham JD, et al. One hundred consecutive hepatic resections: blood loss, transfusion, and operative technique. Arch Surg. 1994;129:1050-1056.

Curley SA, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of unresectable primary and metastatic hepatic malignancies: results in 123 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;230:1-8.

Da Costa JM. Cancer of the pancreas. North Am Med-Chir Rev. 1858;2:883.

Dahl R. Eine Neue operation des gallenwege. Zb F Chir. 1909;36:266.

Damadian R. Tumor detection by nuclear magnetic resonance. Science. 1971;171:1151-1153.

DeMatteo RP, et al. Anatomic segmental hepatic resection is superior to wedge resection as an oncologic operation for colorectal liver metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:178-184.

Demling L, Classen M. Duodenojejunoscopy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1970;95:1427-1428.

Di Sebastiano P, et al. Management of chronic pancreatitis: conservative, endoscopic, and surgical, 4th ed. Blumgart LH, et al, editors. Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas, vol II. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2007:1341-1386.

Doubilet H, Mulholland JH. The surgical treatment of recurrent acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948;86:295.

Dubois E, et al. Cholecystectomy by coelioscopy. Presse Med. 1989;18:980-982.

Dubois E, et al. Coelioscopic cholecystectomy: preliminary report of 36 cases. Ann Surg. 1990;211:60-62.

Du Val MK. Pancreaticojejunostomy for chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Surgery. 1957;41:1019.

Ebara M, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma: study of 95 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1990;5:616-626.

Elias D, et al. Another failure in the attempt of definition of the indications to the resection of liver metastases of colorectal origin. J Chir Surg (Paris). 1992;129:59-65.

Elliot J. Surgical treatment of tumor of the liver with report of a case. Ann Surg. 1897;26:83.

Ensminger W, et al. Effective control of liver metastases from colon cancer with an implanted system for hepatic arterial chemotherapy. Proc Am Clin Oncol. 1982;1:94.

Estefan A, et al. Anastomosis colangiodigestivas en cancer bilar. Cir Uruguay. 1977;47:51.

Fallis LS, Szilagyi DE. Observations on some metabolic changes after total pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1948;128:639.

Ferzli G, et al. Laparoscopic resection of a large hepatic tumor. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:733-735.

Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Useful stapling techniques in liver surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:100.

Fong Y, et al. Repeat hepatic resections for metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:657-662.

Fong Y, et al. Drainage is unnecessary after elective liver resection. Am J Surg. 1996;171:158-162.

Fong Y, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309-318.

Fong Y, et al. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557-569.

Fortner J. Regional resection of cancer of the pancreas: a new surgical approach. Surgery. 1973;71:307.

Fortner JG, Blumgart LH. A historic perspective of liver surgery for tumors at the end of the millennium. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:210-222.

Fortner JG, et al. Orthotopic and heterotopic liver homografts in man. Ann Surg. 1970;172:23-32.

Fortner JG, et al. A new concept for hepatic lobectomy: experimental studies and clinical application. Arch Surg. 1971;102:312-315.

Fortner JG, et al. Major hepatic resection using vascular isolation and hypothermic perfusion. Ann Surg. 1974;180:644-652.

Fortner JG, et al. Surgical management of carcinoma of the junction of the main hepatic ducts. Ann Surg. 1976;184:68-73.

Fortner JG, et al. Major hepatic resection for neoplasia: personal experience in 108 patients. Ann Surg. 1978;188:363-371.

Foster JH. Survival after liver resection for cancer. Cancer. 1970;26:493-502.

Franco D, et al. Hepatectomy without abdominal drainage: results of a prospective study in 61 patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:748-750.

Frey C, Smith G. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701.

Gagner M, et al. Laparoscopic partial hepatectomy for liver tumor. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:99.

Garre C. On resection of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1907;5:331.

Gaston J. Surgery of the Gall Bladder and Ducts, vol IX. New York: William Wood. 1897.

Geevarghese SK, et al. Outcomes analysis in 100 liver transplantation patients. Am J Surg. 1998;175:348-353.

Gibson T, Medawar PB. The fate of skin homografts in man. J Anat. 1943;77:299-310.