Chapter 48 Benign tumors and pseudotumors of the biliary tract

Overview

Painless jaundice is most frequently caused by obstruction of the extrahepatic bile duct by malignant periampullary neoplasms, but benign tumors and pseudotumors of the biliary tract, although rare, should be included in the differential diagnosis. Benign biliary tumors are clinical rarities that in the past have been the subject of infrequent case reports, usually combined with a review of the literature. In previous series, benign bile duct tumors have been reported in 0.1% of all biliary tract operations and have constituted only 6% of all extrahepatic bile duct neoplasms (Burhans & Myers, 1971). To date, fewer than 300 cases of benign bile duct tumors have been reported in the English literature. As shown in Table 48.1, benign neoplasms are derived from the epithelia or from nonepithelial structures that make up the normal bile duct (Levy et al, 2002). Similarly, pseudotumors or tumorlike lesions of the bile duct or other periampullary tissues can cause biliary tract obstruction and jaundice. When pseudotumors or nontraumatic inflammatory strictures of the extrahepatic bile duct are included, the incidence increases, with some surgical series reporting up to a 10% to 25% incidence of benign biliary pseudotumors (Corvera et al, 2005; Koea et al, 2004). Importantly, these series demonstrate that with current preoperative staging tools, it is often impossible to distinguish between benign and malignant etiologies for biliary obstruction, so preoperative tissue confirmation does not often alter management in resectable patients.

Table 48.1 Benign Tumors and Pseudotumors that Can Cause Bile Duct Obstruction

| Epithelial Tumors |

Modified from Levy AD, et al, 2002: Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the gallbladder and extra-hepatic bile ducts: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22:387-413.

Biliary cystadenoma is not covered in this chapter because the lesion usually presents as an intrahepatic cystic neoplasm, which is difficult to differentiate from cystadenocarcinoma (see Chapter 79B). Indeed, benign and malignant epithelium frequently coexist, and histologic diagnosis is extremely difficult (Ishak et al, 1977; Marsh et al, 1974; Moore et al, 1984; Woods, 1981).

Embryologic And Anatomic Factors

Benign tumors of a variety of histologic types have been observed in the extrahepatic ductal system. The embryology and anatomy of the region account for this to a large degree (see Chapter 1A). Embryologically, the extrahepatic biliary tree develops in close relationship to the liver, arising from a thickened area of endoderm on the ventral surface of the primitive gastrointestinal (GI) tract at the junction of the foregut and hindgut in the 3-mm human embryo during the fifth week of intrauterine life. This small outpouching is the anlage of the liver, extrahepatic biliary ducts, gallbladder, and the ventral bud of the pancreas.

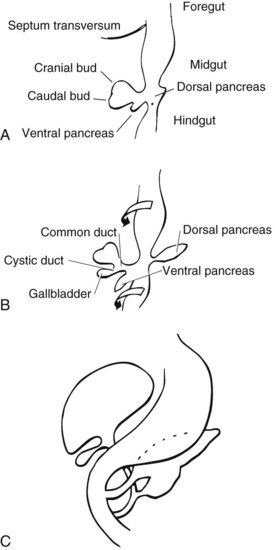

A diverticulum evolves from this thickened area, which divides into a superior and inferior bud as it grows into the ventral mesogastrium (Fig. 48.1A). The ventral pancreatic bud develops from the superior surface of the diverticulum, proximal to the enlarging terminal sacculations. The cranial sacculation, the larger of the two, pushes ventrally and cranially into the septum transversum, which separates the thoracic from the celomic cavity. Composed of a solid mass of endodermal cells, it spreads out into the substance of the septum transversum, eventually forming the right and left lobes of the liver. Cephalad growth and extension of the cranial sacculation results in stretching of the endodermal cell mass from the duodenum to the liver, which eventually evolves into the extrahepatic biliary tree. At approximately the seventh week of intrauterine life, vacuolization takes place within the solid mass of cells of the primitive extrahepatic biliary tree and results in the development of a ductal lumen.

Before the 7-mm stage, the common bile duct (CBD) is attached to the ventral surface of the duodenum close to the ventral pancreatic bud. At the 7-mm stage, left-to-right rotation of the ventral pancreas and duodenum takes place so that the CBD eventually enters on the posteromedial surface of the duodenum (Fig. 48.1B and C). The gallbladder and cystic duct develop concurrently from the caudal portion of the primitive hepatic diverticulum during the same period (Lindner & Green, 1964).

The CBD lies in the right border of the hepatoduodenal ligament between serosal surfaces. The ductal wall is composed of mucosa, fibrous tissue, and serosa. Rare smooth muscle fibers may be found in the duct wall, but muscular tissue is not a prominent component. Thickness of the duct wall varies from 0.8 to 1.5 mm, with an average of approximately 1.1 mm (Mahour et al, 1967). The terminal end of the duct is invested with muscle fibers, as elegantly described by Boyden (1957). At this point the CBD usually joins with the major pancreatic duct, but they may fail to unite and enter the duodenum separately (Dowdy et al, 1961).

The mucosa lining the extrahepatic biliary tree consists of a single layer of columnar epithelium and a tunica propria containing mucous glands. Scattered chromogranin-positive cells can be formed in glands of the normal gallbladder neck, and rare cells immunoreactive for somatostatin have been found between the lining epithelium of the hepatic duct in patients with biliary disease (Dancygier et al, 1984). It has been observed that chronic inflammation of the biliary tract may result in intestinal metaplasia of the mucosa, which seems to result in an increase in the number of argentaffin cells (Kulchitsky cells). Barron-Rodriguez and colleagues (1991) have suggested that these changes may be the basis for the development of carcinoid tumors of the biliary tree. The epithelial surface of the duct is generally flat except for tiny pits in the mucosa known as sacculi of Beale, which are luminal openings for the intramural mucous glands. As the duct penetrates the wall of the duodenum, the mucosa appears to become thickened and the surface roughened by longitudinal folds of mucosa, or valvules, particularly at the terminal end of the duct. According to Boyden (1936), the valvules were first described in the Fabrica of Vesalius (1543), followed later by a more detailed description by Santorini (1724). Brown and Echenberg (1964) described a more frequent occurrence of transversally oriented flaps or valvules that face the duodenal lumen and probably function to prevent reflux of duodenal contents into the biliary tree and pancreatic ducts (Fig. 48.2). Baggenstoss (1983) has also reported that free folds of ductal epithelia in the form of papillary processes may extend 2 to 3 mm beyond the Vaterian orifice.

Clinical Presentations And Diagnosis

Patients with benign biliary tract tumors, and often those with inflammatory masses masquerading as neoplasms, invariably present with clinical manifestations of jaundice. The onset of icterus may be insidious or intermittent, with few other symptoms. On the other hand, the presentation may be sudden and associated with colicky epigastric pain, referred to the back or shoulder, along with nausea and vomiting. There is seldom any significant weight loss, unlike patients with pancreas cancer or cholangiocarcinoma, who frequently present with jaundice, poor appetite, and weight loss (see Chapters 50B and 58B). Because these tumors are relatively slow growing, some of the clinical symptoms may be intermittent or gradually progressive over an extended period only to culminate with obstructive jaundice. No clinical symptoms are apparent that can help the physician differentiate a benign biliary tract tumor from other, more common causes of biliary tract obstruction.

Physical findings are likewise nonspecific: liver enlargement, a palpable gallbladder, tenderness to palpation in the right hypochondrium, and jaundice. Indeed, because of the lack of characteristic symptoms and physical findings, benign biliary tumors usually are not diagnosed preoperatively or antemortem (Chu, 1950).

Reports since the early 1970s have emphasized the usefulness of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the establishment of a preoperative diagnosis of extrahepatic obstruction and in distinguishing between calculus and tumor as a cause (see Chapter 18; Kittredge & Baer, 1975). Noninvasive imaging of the biliary tree with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and high-quality computed tomography (CT) also now play a significant role in the diagnosis of these lesions. In their report of a patient with granular cell myoblastoma, Jain and colleagues (1979) suggested that an eccentric, short stenosis might be associated with a benign biliary tumor. However, obstructive changes identical to those seen in malignant neoplasms are not uncommon and indeed may be produced by inflammatory masses (Hadjis et al, 1985; Stamatakis et al, 1979). Although PTC and ERCP cannot distinguish between a benign tumor and a malignant process, adequate visualization of the ductal system can provide vital information concerning tumor location, extension, and size as well as the status of the intrahepatic ductal system. However, no preoperative diagnostic study is capable of reliably distinguishing benign from malignant tumorous obstruction of the biliary ducts. Endobiliary brush cytology has a high positive predictive value but, unfortunately, the negative predictive value is too low for clinical usefulness, particularly in the setting of a resectable tumor. Similarly, molecular study of cytology specimens, such as K-ras mutational analysis, has not shown improved diagnostic accuracy (Sturm et al, 1999). Newer minimally invasive tissue-acquisition techniques that include endoscopic, ultrasound-guided methods may improve diagnostic accuracy, although negative biopsy results still offer no assurances because of the suboptimal negative predictive value. Therefore these tests often do not often alter clinical management in the resectable patient (Byrne et al, 2004; Eloubeidi et al, 2004).

Papilloma And Adenoma

The most common variety of benign tumor of the extrahepatic biliary tree is that arising from the glandular epithelium lining the ducts. Roughly two thirds of the benign neoplasms reported fall into the category of either polyp, adenomatous papilloma, or adenoma. Chu (1950), in his classic review of benign biliary neoplasms, found that 26 out of 30 cases studied were either papillomas or adenomas. A similar observation was made by Dowdy and colleagues (1962), when 36 of the 43 reviewed cases were noted to be either papillomas or adenomas. Since 1962, 58 additional patients have been added to the English literature (Bahuth & Winkley, 1966; Short et al, 1971; Sull & Brown, 1972; Archie & Murray, 1978; Lukes et al, 1979; Bergdahl & Andersson, 1980; Austin et al, 1981; Gouma et al, 1984; Van Steenbergen et al, 1984; Thomsen et al, 1984; Byrne et al, 1989; Loh et al, 1994; Chae et al, 1999; Fletcher et al, 2004; Kunisaki et al, 2005; Boraschi et al, 2007; Akaydin et al, 2009). Presently, we have traced a total of 120 patients reported in the English literature with benign polyps, adenoma, or cystadenoma.

A slight female predominance (1.3 : 1) in the incidence of these lesions has been noted, and although the average age at diagnosis is 58 years, the youngest recorded occurrence was in a 3-year-old child (Wardell, 1969). Leriche (1934) reported a massive papillomatous tumor weighing 750 grams, arising from the CBD of a 4-year-old child.

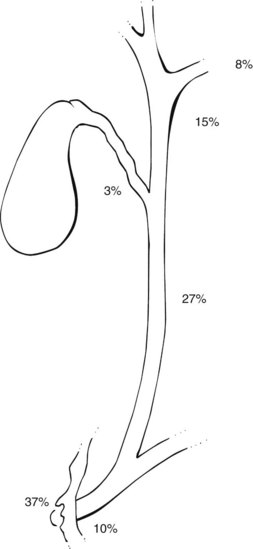

The anatomic distribution of papillomas or adenomatous lesions reported to date appears in Figure 48.3. The majority are found either in the ampulla or in close proximity to the Vaterian system (47%), and the CBD (27%) is the second most frequent site.

The onset of symptoms may vary from a few weeks to 35 years. Jaundice, a presenting symptom in more than 90% of patients (McIntyre & Pay-Zen, 1968), occurs intermittently in approximately 40% of patients. Most patients complain of right upper quadrant pain associated with the jaundice. Wright (1958) reported a patient with relapsing pancreatitis who was cured by excision of a CBD polyp that had prolapsed into the ampulla of Vater. Gallstones or biliary calculi are reported in only 20% of patients found to have benign extrahepatic ductal tumors. Cattell and Pyrtek (1950) suggest that recurrence of symptoms following cholecystectomy should suggest the possibility of a tumor in the ampullary area rather than biliary dyskinesia.

A benign adenomatous tumor should be included on the differential list in all secondary operations performed for obstruction of the biliary tree. Interestingly, Kunisaki and colleagues (2005) described the case of a 54-year-old man who showed up with abdominal pain and jaundice 3 years after a cholecystectomy for cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis. ERCP revealed impingement of the common hepatic duct (CHD) at the level of the cystic duct, without filling of the cystic duct remnant. Reexploration for a presumed diagnosis of retained cystic duct stone revealed a 2-cm papillary adenoma of the cystic duct remnant, compressing the CBD (Mirizzi syndrome; see Chapter 42B) and causing symptoms. These lesions are generally soft, difficult to palpate, and present little or no resistance to exploring ductal probes; thus they are difficult to detect at operation and are more frequently detected by intraoperative cholangiography, ultrasonography, or choledochoscopy (see Chapter 21).

The radiographic features of extrahepatic bile duct adenomas are often difficult to distinguish from cholangiocarcinomas and even ampullary cancers (see Chapters 50B and 59; Figs. 50B.2 and 50B.8). Ultrasound typically reveals a nonshadowing intraluminal mass, sometimes with a visible pedicle or stalk but more often with a sessile architecture. ERCP will show a lobulated intraluminal filling defect that is often obscured by mucin accumulation in mucin-producing adenomas. Lesions developing in the lower CBD near the ampulla may actually protrude through the papilla and be visible endoscopically, and we have seen such a case. In contrast, malignant lesions developing in the ampullary area tend to be infiltrative and are usually larger, firmer, and more likely to be ulcerated at presentation. Initial symptoms related to bleeding in association with benign adenomatous polyps of the bile ducts are exceedingly rare, although Teter (1954) recorded a death due to massive hemorrhage secondary to such a lesion.

Kozuka and colleagues (1984) suggested that most polypoid or papillary cancers of the extrahepatic duct arise from preexisting adenomas (see Chapter 50B). In a review of 43 carcinomas of the extrahepatic tree, they identified an adenomatous residue in nine (21.4%). Gouma and colleagues (1984) reported a case of intrahepatic bile duct papillomata associated with changes of nuclear atypia and reviewed the literature, suggesting that it is reasonable to regard these lesions as having low-grade malignant potential. Pathologic review of the specimens often show foci of carcinoma in situ, atypia, or dysplasia; these may point to a premalignant nature, but the rarity of such lesions makes definitive conclusions difficult.

Although it has been suggested that biliary adenomas may be the result of a focal reactive process to injury, the exact etiology remains uncertain. Miyano and colleagues (1989) demonstrated that these lesions could be produced experimentally by performing a choledochopancreatostomy in puppies, a model for anomalous choledochopancreatic ductal junction. After several years, mucosal hyperplasia was observed in 100% of the dogs, and almost half had bile duct adenomas.

Austin and colleagues (1981) reported two patients who presented with obstructive jaundice and solitary, nonparasitic liver cysts. At reoperation, the first was found to have a papillary adenoma in the CHD, which was excised; the second had an obstructing polypoid cystadenoma of the left hepatic duct compressing the right biliary system.

A possible association was proposed between solitary, nonparasitic liver cysts and adenomas of the ductal system (Austin et al, 1981), and the clinical course of these two underscores the difficulty in detection of soft adenomatous tumors obstructing the extrahepatic biliary tree. An association between nonparasitic cystic biliary disease and the development of cholangiocarcinoma has also been described in the literature (Schiewe et al, 1968; Jones & Shreeve, 1970; Gallagher et al, 1972; Dayton et al, 1983; Nasu et al, 1971; Leroy et al, 1979). However, any association between these overt malignancies and the presence of preexisting adenoma or papilloma within biliary cysts is difficult to prove.

Multiple Biliary Papillomatosis

Multiple biliary papillomatosis (MBP) is a rare disease characterized by the presence of numerous mucin-secreting papillary adenomas within the extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic biliary tree. It is generally considered a low-grade malignancy with a propensity for local recurrence after resection. Histologically, these papillomas consist of fibrovascular stalk covered by a single layer of epithelial cells with apical mucin and minimal pleomorphism (Tsui et al, 2000). The etiology and pathogenesis of MBP remain unclear. One hypothesis includes induction of mucosal metaplasia or hyperplasia in response to chronic biliary inflammation by stones, infection, or pancreatic juice. Terada (1991) and Cheng (1999) suggested a relationship between MBP and Caroli disease that may indicate a congenital etiology. Most of the reported cases are from Asia, which may reflect a racial or geographic predeliction, but such an association has not yet been established.

Preoperative diagnosis is made radiologically and may be made more frequently now, since the advent of widespread availability of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC), MRCP, and direct cholangioscopy. The endoscopic examination of the papilla of Vater often shows a widely open orifice with mucin drainage. Direct or noninvasive cholangiography shows multiple intraluminal filling defects that typically do not move with vigorous catheter irrigation and hence can be differentiated from mucin or stones. The lesions can be intrahepatic, extrahepatic, or both (D’Abrigeon, 1997). Tompkins and colleagues (1976) have emphasized the value of intraoperative endoscopy in the evaluation of the biliary tree for multiple lesions. Several studies have suggested that endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be at least as accurate as ERCP in diagnosing MBP, with the additional advantage of visualizing invasion of the duct wall or adjacent vessels and metastasis to locoregional lymph nodes in the presence of malignancy (Mukai, 1995; Ma, 2000; Lai, 2002).

Caroli and colleagues (1959) first reported the occurrence of diffuse papillomatosis in both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts of a 42-year-old male. Although the presenting symptoms were of abdominal pain and jaundice, the patient was also noted to be anemic secondary to hemobilia. A T-tube was placed in the biliary tree, through which 10 L of mucoid secretions were drained in the first 24 hours following surgery. The patient died 48 hours later. It was noted that the biliary secretions had a high potassium content, which the authors postulated might be analogous to the mucoid diarrhea and hypokalemia associated with villous adenoma of the colon. In the same report, a second patient presented with cholangitis and was reported to be cured following a left hepatectomy for papillomatosis confined to the left intrahepatic ducts.

Since Caroli’s first report in 1959, an additional 87 cases of MBP have been reported in the English literature. A review of 78 cases by Yeung and colleagues (2003) showed a male/female ratio of approximately 2 : 1, with a mean age at presentation of 63 years (range, 6 to 83 years). The most common symptoms at the initial visit were abdominal pain and jaundice. Almost half of the patients (42%) had diffuse intrahepatic and extrahepatic disease, and 27% had only intrahepatic disease; another 27% had only extrahepatic disease, and two patients had involvement of the gallbladder. Malignant transformation was seen in 42% of the patients at the time of presentation. Only 55% of the patients were candidates for a curative resection, and the remainder were palliated in various ways, including choledochoscopic laser ablation, iridium-192 intraluminal therapy, percutaneous cholangioscopic electrocoagulation, and combined cholangioscopic laser ablation and external beam radiotherapy.

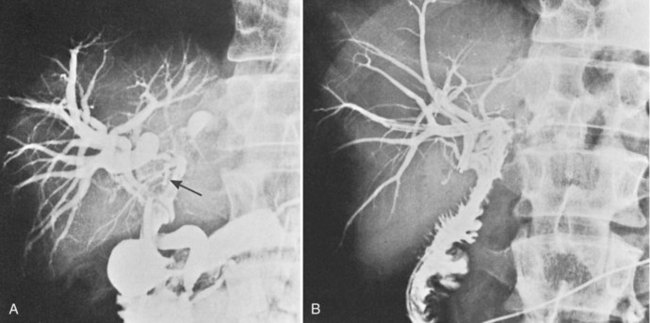

The low-grade malignant potential of MBP has been the subject of many studies. Cattell and colleagues (1962) suggested that these lesions had a low-grade malignant potential after reporting recurrence of obstructive jaundice in a patient within a year of undergoing successful placement of a T-tube. Indeed, risk of malignant transformation with nuclear atypia or carcinoma in situ is significant, and it is commonly observed in papillary lesions. Ohta and others have reported point mutations of the KRAS gene in benign papillary lesions (Ohta et al, 1993). Padfield and colleagues (1988) documented basement membrane discontinuities in three patients consistent with patterns accompanying malignant tumors; they cautioned that papillary neoplasms, although histologically benign, should be considered premalignant. Gouma and others (1984) reported a similar case, in which intrahepatic bile duct papillomata (Fig. 48.4A) were associated with changes of nuclear atypia. The patient was treated by left hepatic resection that included the base of the papillomatous lesions, and biliary-enteric continuity was established by hepaticojejunostomy to the residual right liver (Fig. 48.4B). The patient was symptom-free and without recurrence 4 years after surgery.

The authors concur with Cattell’s view that it is reasonable to regard these lesions as having low-grade malignant potential. A further patient has been reported who lived approximately 5 years before dying of cholangitis (Madden & Smith, 1974). Treatment had included partial hepatic resection, choledochoduodenostomy, and weekly courses of carmustine (BCNU). Some decrease in the amount of tumor was observed following therapy, and although cellular atypia was reported, no malignant changes could be documented at autopsy. Of the two recently reported patients, an 80-year-old male died after choledochoduodenostomy because of variceal bleeding, but the second, reported by Gertsch and colleagues (1990), was reported alive and well 15 months after curettage (Hubens et al, 1991).

The extent, distribution, and secondary obstructive changes induced by these soft lesions present management challenges. If the lesions are limited and confined to one liver lobe, liver resection should be strongly considered, although attempted radical surgery by means of hepatic lobectomy has been reported in only five cases: One of these was alive and well at 4 years (Gouma et al, 1984). One further case was reported alive 6 months after surgery with no evidence of recurrence, and one died 6 years after resection with diffuse malignant tumors in the right lobe of the liver after initial left hepatic lobectomy. The remaining two patients had multiple papillomatoses, apparently localized to the left hepatic duct at operation; both had recurrence in the common and right hepatic duct 6 months and 3 years after lobectomy and died 5 and 6 years, respectively, after the first operation. It seems clear, therefore, that even major resectional surgery for this lesion has a high recurrence rate; Gouma and colleagues (1984) were able to trace 12 patients for whom adequate follow-up figures were available and found mean survival to be 28 months. It should be noted, however, that although no patient survived more than 6 years, the only 5-year survivals were in three cases submitted to radical surgery.

A report by Helling and Strobach (1996) documents a 67-year-old female patient with papillomatosis and high-grade dysplasia occluding the left hepatic duct who was successfully managed by a left hepatic lobectomy. The patient was disease free 20 months following resection. The authors reviewed the literature and commented on three important features of this lesion: 1) a high recurrence rate, with approximately 50% of patients requiring reoperation; 2) copious mucin production that may lead to fluid electrolyte imbalances, and 3) malignant transformation, which is observed in a significant percentage of patients (Helling & Strobach, 1996). Since this report, five additional extrahepatic benign papillary lesions have been recorded (Loh et al, 1994; Lam et al, 1996; Meng et al, 1996; Khan et al, 1998; Yeung et al, 2003).

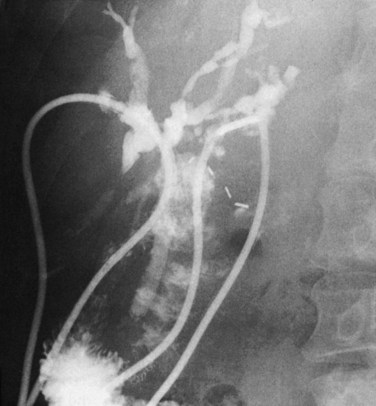

An intubational approach to papillomatosis affecting the entire biliary tree has been described (Fig. 48.5). Employment of the approach described by Hutson and colleagues (1984) and by Barker and Winkler (1984) seems reasonable: a Roux-en-Y hepaticodochojejunostomy is fashioned in such a manner as to allow a jejunal fistula for access to the biliary tree postoperatively and permit repeated curettage or intubation. Meng and colleagues (1996) reported on the use of holmium : YAG laser therapy via choledochoscopy and successful ablation after curettage; after four sessions of choledochoscopy and laser therapy, all tumor was ablated, and there were no signs of tumor recurrence at 6 months. Lastly, consideration might be given to chemotherapy, especially with agents excreted by the liver. Recently Beavers and colleagues (2001) reported the case of a 59-year-old patient with recurrent cholangitis from diffuse biliary papillomatosis that persisted even after a left hepatectomy and hepaticojejunostomy. Because of deteriorating liver function, she was placed on the list for liver transplantation and underwent successful orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) with a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. She was alive and asymptomatic 9 months following the surgery. Similarly, Dumortier and colleagues (2001) reported their results for a 61-year-old patient with recurrent symptoms from diffuse MBP who underwent an OLT and pancreatoduodenectomy. Her final pathology revealed three foci of invasive carcinoma limited to the biliary wall. After 22 months of follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, without evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis.

Granular Cell Tumors

Granular cell tumor (GCT) is a very rare benign tumor of uncertain etiology occasionally encountered in the extrahepatic biliary tree. First desribed in 1926 as granular cell myoblastoma, recent debate has ensued about the cell of origin. Levy and colleagues (2002) suggest that, rather than myoblasts, the tumor may originate fom Schwann cells, evidenced by its immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to S-100 protein normally found in the central nervous system or in Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. Honjo and colleagues (2003) recently reported a case of extrahepatic biliary Schwannoma, basing this diagnosis on S-100 positivity on immunohistochemistry. Similarly, Altavilla and colleagues (2004) described reactivity to S-100 and neuron-specific enolase antibodies in GCT of the intrapancreatic portion of the CBD.

GCTs constitute less than 10% of all benign tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tree (Dursi et al, 1975). Although reported in anatomic locations as varied as the pituitary and appendix, the lesions are most commonly encountered in the tongue, breast, and subcutaneous tissues, with less than 1% of GCTs occurring in the extrahepatic biliary tree (Paskin et al, 1972; Dursi et al, 1975). The most frequent sites of occurrence of extrahepatic biliary GCTs are the CBD, cystic duct, and gallbladder. The average age of patients with this tumor is 34.5 years. More than 80% of documented cases have occurred in females, 66% of whom are black, and 15% of patients have multiple lesions (Vance & Hudson, 1969).

Since Coggins’ original autopsy report in 1952, 67 additional patients have been reported with GCTs of the extrahepatic biliary tree; 33 had lesions arising from the common hepatic or CBD, 19 from the cystic duct, 5 from the cystic duct and CHD, and 4 from the hepatic duct (Kittredge & Baer, 1975; Mauro & Jacques, 1981; Cheslyn-Curtis et al, 1986; Lewis et al, 1993; MacKenzie et al, 1994; Yazdanpanah et al, 1993; Ferri Romero et al, 1994; Foulner, 1994; Karakozis et al, 2000; Pongtippan et al, 2000; te Boekhorst et al, 2000; Altavilla et al, 2004; Lochan et al, 2006). In addition, one patient had lesions involving the cystic duct and the hepatic duct (Sanchez & Nauta, 1991); two had lesions involving the cystic duct, gallbladder, and CBD (Aisner et al, 1982; Martin et al, 2000); and two had cystic duct, CHD, and CBD lesions (Balart et al, 1983; Butler & Brown, 1998). GCT arising from the ampulla of Vater has only been reported once (Khalid et al, 2005).

The fact that extrahepatic ductal granular cell myoblastomas are found more commonly in black females is attested to in the literature: 38 of 54 females recorded are black, 10 are Caucasian, 3 are Asian, and 5 are of unspecified racial origin. Three black males and a single male child of unspecified race have been reported. Multiple tumors within the extrahepatic biliary tree have been reported in seven patients (Kittredge & Baer, 1975; Mauro & Jacques, 1981; Aisner et al, 1982; Sanchez & Nauta, 1991; Cheslyn-Curtis et al, 1986; MacKenzie et al, 1994; Martin et al, 2000). Multifocal tumors have been noted in seven patients with bile duct lesions, two patients with separate gastric tumors, four with synchronous skin lesions, in one individual with lesions in the mesentery and trachea, and in one patient with simultaneous lesions in the trachea and CHD (Mulhollan et al, 1992; LiVolsi et al, 1973; Whisnant et al, 1974; Assor, 1979; Manstein et al, 1981; Orenstein et al, 1984; Yang & Ortiz, 1993). Clinical symptoms associated with granular cell myoblastoma arising in extrahepatic bile ducts tend to be those of painless jaundice, and a presentation of upper abdominal pain and colic is more commonly associated with lesions arising in the cystic duct. Other described symptoms include anorexia, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting. Granular cell myoblastoma might be included in the differential diagnosis of obstructive jaundice seen in a black female, especially if she has a tumor nodule in the tongue, breast, or subcutaneous tissue, but such a clinical presentation would be extraordinarily rare.

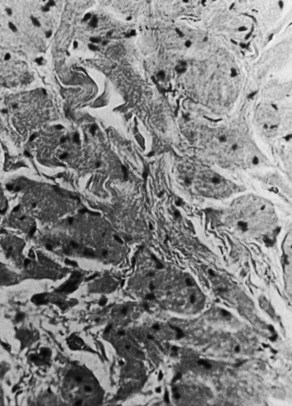

The majority of tumors have been described as firm to palpation, localized, confined to the wall of the CBD or cystic duct, and generally less than 3 cm in diameter. Because granular cell tumors are typically small, they may not be visible on US or CT scan, and only intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilation are seen. ERCP often reveals a short, focal, annular stricture, and MRCP may show similar findings. Usually these tumors do not invade surrounding structures, and the mucosa overlying the tumor has generally been intact and histologically normal. On cut section, granular cell myoblastoma is yellowish white, and microscopically it consists of fibrous tissue diffusely infiltrated by large, elongated polygonal cells or cells containing small, dark nuclei and an abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm on a hematoxylin and eosin stain. The cytoplasmic granules are markedly positive with the periodic acid-Schiff reaction (Fig. 48.6), and frozen-section diagnosis has been shown to be adequate for delineating these lesions. Although this tumor usually does not metastasize, local recurrence may occur, especially if excision is incomplete.

The histogenesis is uncertain and is marked by controversy. The tumor was initially termed granular cell myoblastoma, because it was thought to be derived from “myoid cells.” Indeed, characteristics of the cells in tissue culture suggest a myogenic origin (Murray, 1951). Moreover, it is now generally regarded that granular cell tumors arise from the Schwann cell in that the tumor cells react to antibodies with S-100 protein, normally found in the central nervous system and in peripheral Schwann cells (Armin et al, 1983). Treatment should consist of total excision of the bile duct segment containing the lesion with reconstruction by Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy or hepaticojejunostomy for lesions arising in the CHD (Manstein et al, 1981; MacKenzie et al, 1994). Altavilla and colleagues (2004), Karakozis and colleagues (2000), Chandrasoma and Fitzgibbons (1984), Manstein and colleagues (1981), and Raia and colleagues (1978) have reported successful management of lesions occurring in the intrapancreatic bile duct by pancreaticoduodenectomy. Two local recurrences were documented, and three patients required second procedures because of incomplete local excision (Dursi et al, 1975; Manstein et al, 1981; Butler & Brown, 1998; Khalid et al, 2005). To date, malignancy has not been observed in any reported extrahepatic glandular cell tumor.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Endocrine tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts are exceedingly rare. The only endocrine cells that have been normally demonstrated in the extrahepatic ducts are somatostatin-containing D cells (Dancygier et al, 1984). However, it has been postulated that metaplastic changes in the biliary epithelium, perhaps resulting from inflammation, may lead to the development and appearance of argyrophile cells (Barron-Rodriguez et al, 1991). Because the biliary system is derived embryologically from the foregut, it is not surprising that cells immunoreactive for gastrin, serotonin, and somatostatin have been demonstrated in the biliary tree (Angeles-Angeles et al, 1991). Only a handful of cases have been reported, most of which have been hormonally nonfunctional. Reported tumors fall into one of three categories: carcinoid, gastrinoma, or somatostatinoma. A clinical picture of obstructive jaundice is the usual presentation, although a carcinoid was found incidentally in the unobstructed CBD of an explanted cirrhotic liver following OLT (Hao et al, 1996). To date only one patient has been recorded as having a functioning endocrine tumor, a 52-year-old female with a 2-year history of recurrent duodenal ulcer whose peptic disease was cured when her gastrinoma was excised from the CBD (Mandujano-Vera et al, 1995).

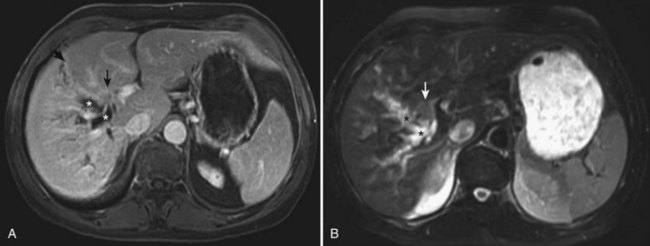

Since Davies’ original report in 1959, an additional 61 documented cases of carcinoid tumors arising in the extrahepatic bile ducts have been reported in the literature (Felekouras et al, 2009). In the cases reviewed, jaundice was the most common presenting symptom (two thirds of patients), and a third had right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Other symptoms included back pain, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting. Analysis also indicates an increased incidence of extrahepatic carcinoid tumors in younger people along with a slight female predominance (1.9 : 1). There have been 35 reported cases of biliary carcinoids arising in the CBD, 14 of tumors originating in the hilum, 7 in the cystic duct, and 5 arising in the CHD (Davies, 1959; Bumin et al, 1990; El Rassi et al, 2004; Nesi et al, 2006; Felekouras et al, 2009). A recent report from Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) documented a case of isolated carcinoid arising from the right hepatic duct (Ferrone et al, 2007; Fig. 48.7A and B). The clinical course is indolent, and endoscopic or percutaneous biopsy or brush cytology tends to be notoriously nondiagnostic, which makes preoperative diagnosis difficult. Most small neuroendocrine tumors of the CBD are found incidentally during biliary tract operations performed for other indications, and the final diagnosis is made postoperatively, after histologic and immunohistochemical examination. Although some patients with carcinoid tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts may have slightly elevated levels of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, none of the published cases have reported carcinoid syndrome. Biliary neuroendocrine tumors have an indolent biologic behavior and exhibit limited propensity for metastatic disease, which has been reported only in a third of the patients at presentation. Most patients are candidates for curative resection, with excellent long-term results.

The choice of operation depends on the location of the tumor and the extent of disease. Hilar, CHD, and proximal CBD neoplasms can be treated with regional lymphadenectomy, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (Jutte et al, 1986; Bumin et al, 1990), and en bloc resection of the tumor and adjacent bile ducts. In the uncommon situation of carcinoid tumors arising at or above the biliary confluence, distinguishing this diagnosis from cholangiocarcinoma prior to operation is nearly impossible; an approach to resection that includes en bloc partial hepatectomy is required for cholangiocarcinoma (see Chapter 50B; Ferrone et al, 2007; see Fig. 48.7A and B). Patients seen initially with tumors of the distal bile duct are generally managed with pancreatoduodenectomy, or Whipple procedure (Vitaux et al, 1981; Nesi et al, 2006). There have been three reported cases of patients with cystic duct tumors treated with a simple cholecystectomy (Goodman et al, 1984; Hermina et al, 1999; Nahas et al, 1998). Long-term disease-free survival up to 20 years has been reported, even in the presence of distant metastases (Davies, 1959; Little et al, 1968; Hao et al, 1996; El Rassi et al, 2004).

No absolute histologic criteria are available by which to judge the malignant potential of biliary endocrine tumors. Larger tumors are thought to be more aggressive with respect to metastatic potential; however, metastases with very small carcinoid tumors of the cystic duct have been reported (Hermina et al, 1999). Ki-67 cell index greater than 5% also does not necessarily predict aggressive behavior (Ligato et al, 2005). Given the good long-term results with surgical resection, it is generally agreed that curative surgical resection is the most relevant prognostic factor in management of endocrine tumors of the extrahepatic biliary ducts.

Neural Tumors

The incidence of neural tumors would appear to be lower than expected, when the abundant network of neural tissue that normally surrounds the extrahepatic bile ducts is considered. In 1955, Oden reported the occurrence of a neuroma in a 40-year-old woman who presented with jaundice and mild epigastric discomfort. At operation, a cystic tumor was found displacing the CBD medially. The cyst was extirpated, but the wall contiguous to the CBD was left in situ. Several common duct stones were also removed.

Neurofibromas of the bile duct are extremely uncommon, although they have been reported in patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF). Because GI involvement occurs in approximately 25% of patients with NF, biliary involvement is more commonly secondary to obstructing duodenal or periampullary neurofibromas (Mendes, 2000). Although bleeding, perforation, and obstruction as a result of intussusception, volvulus, and stenosis have been reported, only one other instance of obstructive jaundice secondary to visceral neurofibromatosis has been recorded in the literature. Curry and Gray (1972) reported the autopsy finding of a submucosal nodular tumor 25 mm in diameter protruding into the duodenum around the ampullary opening.

Sarma and colleagues (1980) reported a hilar tumor arising in the left hepatic duct and surrounding the right hepatic duct that was deemed unresectable. The biopsy submitted at that time was interpreted as poorly differentiated carcinoma. A tube was placed through the lesion, and the patient was readmitted with cholangitis several times over the next 7 years. A second exploration revealed total obstruction of the left hepatic duct, partial obstruction of the right hepatic duct, and cystic degeneration of the left lobe of the liver. Another tube was placed through the tumor into the right hepatic duct, and the cystic left liver lobe was drained by a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop. Review of the fresh biopsies and the original material were each interpreted as paraganglioma. Although these tumors commonly arise in the adrenal gland as pheochromocytoma, extraadrenal lesions are more commonly found in the neck, the mediastinum, and around the aorta. Paragangliomas have been observed in the gallbladder, GI tract, and the genitourinary tract; this appears to be the first lesion reported in the extrahepatic biliary tree.

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas are the most common benign tumors of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine; in the extrahepatic biliary tree, they are among the least common. The scanty presence of muscle fibers in the normal CBD probably accounts for the fact that only seven such lesions have been reported. Each of these patients presented with progressive jaundice, itching, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. The first case was reported in a 31-year-old female with a 2-cm tumor confined to the intrapancreatic segment of the CBD, which was locally excised, along with some of the overlying pancreatic tissue; the duct of Santorini was also ligated, and the proximal bile duct was anastomosed to the jejunum. This patient was reported well 3 years following surgery (Archambault & Archambault, 1952). Fernandez and Gonzales-Bueno (1974) recorded a leiomyoma occuring at the ampulla of Vater. A third patient, reported by Kune and Polgar (1976), was a 49-year-old male treated by pancreatoduodenectomy for a 4-cm tumor in the intrapancreatic segment of the CBD, which was assumed to be a pancreatic carcinoma at surgery. Microscopically, the lesion was observed to arise from the bile duct wall, and the patient was well 28 months after operation. The fourth patient died of septicemia following ERCP demonstration of a tumor obstructing the lower part of the CBD, seemingly as a result of external compression. Autopsy examination revealed an angioleiomyoma of the CBD; the mucosa overlying the tumor was observed to be intact (Ponka et al, 1983). Mandeville and Stawski (1991) reported a fifth patient in whom a leiomyoma of the hepatic duct bifurcation was treated with excision and hepaticojejunostomy. Yamaoka and colleagues (1993) described the case of a 49-year-old male with distal common bile duct leiomyoma who was treated with pancreatoduodenectomy. Recently, Goo and colleagues (2006) described a seventh case of biliary leiomyoma in a 39-year-old woman who underwent a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy for a distal CBD stricture. Final pathology disclosed leiomyoma of the CBD accompanying severe fibrosis.

Pseudotumors

Nonmalignant lesions may cause obstruction of the extrahepatic biliary ductal system and closely resemble neoplasms at investigation and even at laparotomy; they occur frequently enough to be seriously considered in the differential diagnosis of any lesion suspected to be a bile duct tumor. In a recent large series of 132 consecutive patients undergoing resection for a suspicious hilar lesion, 20 (15%) had a histopathologically proven benign tumor diagnosed as chronic fibrosing or erosive inflammation, sclerosing cholangitis, or a granular cell tumor (Gerhards et al, 2001). Similarly, the incidence of benign pseudotumors is approximately 10% to 20% in several recently published large series of surgically treated patients with proximal biliary obstruction (Corvera et al, 2005; Koea et al, 2004; Binkley et al, 2002). Interestingly, all of these published series show that preoperative diagnosis is difficult, and resection remains the only reliable way to rule out malignancy. In a more recent study of 171 patients with a presumptive diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, benign strictures were ultimately identified in nine (5.3%; Are et al, 2006). In this study, the combination of vascular involvement and lobar atrophy were much more common in patients with cholangiocarcinoma (38%) than in those with other diagnoses (3.3%, P < .001; see Chapter 50A, Chapter 50B, Chapter 50C, Chapter 50D ).

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) should be strongly suspected in a patient with biliary stricture in the setting of ulcerative colitis; the prevalence may be as high as 90% when routine rectal and sigmoid biopsies are obtained (Tung et al, 1996; see Chapter 41). Diagnosis can be established by demonstration of characteristic multifocal stricturing and dilation of the intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary tree on cholangiography (Lee & Kaplan, 1995). Untreated disease almost always leads to complications of hepatic failure and cholestasis, and liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with advanced disease. Five-year survival rates as high as 85% have been described after liver transplantation for patients with PSC (Langnas et al, 1990; Graziadei et al, 1999).

Inflammatory Tumors

Stamatakis and colleagues (1979) reported the occurrence of a benign inflammatory mass of the CBD in a 13-year-old girl who presented with obstructive jaundice and abdominal pain. PTC demonstrated complete obstruction of the CHD with intraluminal shouldering, suggesting a tumor. At operation, a 3-cm spherical mass was found to be closely applied to the porta hepatis, necessitating excision of the confluence, CHD, and CBD with reconstruction by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Pathologic examination demonstrated nearly complete obstruction of the CHD and CBD by an encapsulated yellowish-brown mass. Microscopically, the encased bile duct exhibited loss of muscular coat, loss of ductal epithelium, and replacement by collagenous fibrous tissue. Scattered throughout the fibrous tissue were foci of acute inflammatory cells. These authors concluded that the mass represented an excessive inflammatory reaction to some local chemical or infective irritant and further speculated that the lesion might represent a form of localized sclerosing cholangitis. The child was reported fit and active 1 year after treatment.

Haith and colleagues (1964) reported a somewhat similar clinical occurrence in a 6-year-old boy with a lesion located in the distal CBD, treated successfully by pancreatoduodenectomy. A similar case was reported by Golematis and colleagues (1982) of a 23-year-old man who presented with obstructive jaundice and a lesion at the confluence of the hepatic ducts. The lesion was successfully resected and histologically appeared to represent a localized area of sclerosing cholangitis. One other such case has been reported by Heuser and Polk (1983).

Standfield and colleagues (1989) reported an interesting group of 12 patients with localized strictures of the extrahepatic biliary system. No patient had a history of trauma, gallbladder stones, or antecedent diseases generally associated with sclerosing cholangitis. All patients were found to have histologic evidence of chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and epithelial ulceration. These authors felt that this entity was distinct from sclerosing cholangitis in that the mucosa remains intact in sclerosing cholangitis.

At the Hammersmith Hospital, London, Hadjis and colleagues (1985) showed eight out of 104 patients submitted to surgery with a clinical diagnosis of malignant obstruction at the confluence of the bile ducts to have benign disease. The benign nature of the lesion was not certain in 6 of these patients even at the time of laparotomy. Comprehensive investigation had failed to give an accurate preoperative diagnosis, although biliary obstruction was accurately shown in all patients, and preoperative assessment using cholangiographic and angiographic data indicated that all were potentially resectable. For this reason, and in light of the safety of local excisional surgery and excellent quality of life obtained (Beazley et al, 1984; Blumgart et al, 1984), palliation by intubational methods was not attempted. In all patients, the obstructing lesion was removed, biliary reconstruction was by means of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, and liver biopsy was obtained.

Microscopic examination of the biopsies taken from the bile ducts of these patients showed an extensive increase of fibrous tissue in all instances. Subepithelial mucous glandular proliferation was evident in all patients, but not in every specimen, and the glandular cells were always well differentiated with elongated to round nuclei showing normal polarity. Most glands were surrounded but not replaced by fibrous tissue. In some instances, glands appeared to be distorted by fibrous tissue coursing between acini. Striking nerve trunks were observed in four of the patients but not in all the specimens, some of which were very small. Accumulations of lymphocytes were present in most specimens and were sometimes perivascular, sometimes perineural, but not diffusely infiltrating the wall of the bile duct, with little adventitial inflammation. Sections of associated lymph nodes and of the gallbladder were unremarkable, and no vascular changes were identified. In no specimen was evidence of dysplastic, neoplastic, or preneoplastic cytologic change found. Nuclei were normal, no single epithelial cells were encountered within connective tissue, and no pools of mucin were found. Similar changes were reported by Ikei and colleagues (1989).

Although the cholangiographic picture of diffuse sclerosing cholangitis is usually characteristic (see Chapter 41), this is not necessarily true of the localized form of the disease. The diagnostic difficulty is compounded in that cholangiocarcinoma has been described in association with, or as a complication of, PSC. It is important to emphasize that in the presence of a localized high bile duct stricture, and in the absence of angiographic involvement, it is impossible, without specific biopsy or cytology, to make a definitive diagnosis in this situation. The marked desmoplastic reaction that even small hilar cholangiocarcinoma often excites, together with the ductal and glandular hyperplastic changes consequent of long-standing obstruction and severe secondary cholangitic changes, comprise the main pathologic factors responsible for histologic difficulty in differentiating benign from malignant disease (Weinbren & Mutum, 1983). Indeed, some believe that cases of sclerosing cholangitis localized at the hilum may be instances of slow-growing sclerosing carcinoma, and that it is only a matter of time before such a lesion declares its malignant potential. However, extensive studies at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School have demonstrated characteristic features of malignant biliary disease (see Chapter 47; Weinbren & Mutum, 1983), and these were found to be absent in all cases in the series reported by Hadjis and colleagues (1985). Six patients remained symptom free with normal liver function at a mean follow-up period of 28.3 months.

In a more recent series, Koea and colleagues (2004) presented a New Zealand experience of 49 consecutive patients who presented with obstructive jaundice as a result of a stenosing lesion at the hepatic hilus. The final tissue diagnosis in 12 of these patients was benign (idiopathic benign biliary stricture in ten and stone disease in two). MRI, US, CT scan, and cholangiography were performed in all patients. At least half of the benign lesions had radiologic features suggestive of malignancy. Routine measurement of serum CEA and CA19-9 was also performed. Marked elevation of CA19-9 was shown to have a high positive predictive value, but five of 32 patients with malignancy had a normal CA19-9, and CEA was not found to be useful. The authors concluded that current diagnostic modalities do not reliably distinguish malignant and benign disease, and therefore definitive resection should remain the gold standard. Interestingly, Koea and others point out that frozen section performed intraoperatively did not guarantee an accurate tissue diagnosis, as these were negative in two patients with subsequently confirmed cholangiocarcinoma.

Gerhards and colleagues (2001) reported 20 cases of suspicious hilar lesions that ultimately proved to be benign. Interestingly, of the 16 patients who had ERCP, 13 were considered to have radiographic characteristics suspicious for malignancy (irregular eccentric stenosis or blunt ending). Brush cytology revealed no malignant cells in nine patients, atypical cells in four, and carcinoma in a single patient, again attesting to the poor accuracy of this test.

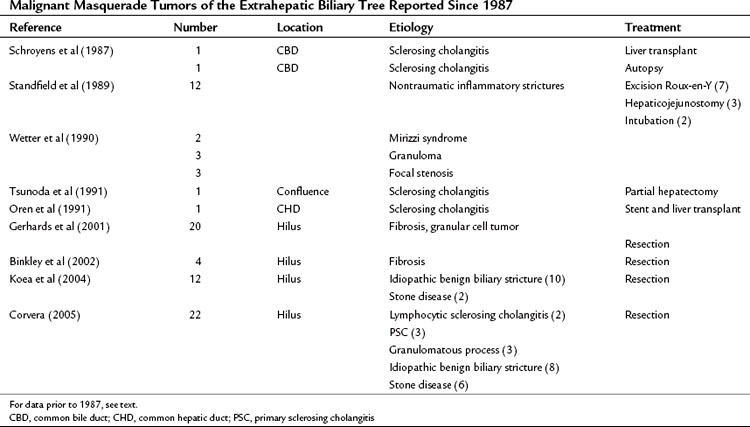

Similarly, in the report by Corvera and colleagues (2005), 22 of 275 patients treated at MSKCC for proximal biliary obstruction had a final histologic diagnosis of benign fibroinflammatory stricture despite preoperative radiologic assessment suggestive of malignancy, a feature termed “malignant masquerade” by the authors. The etiology of obstruction in these cases is listed in Table 48.2. No preoperative clinical or diagnostic features were identified in this series that could reliably distinguish between benign and malignant causes of bile duct stricture, leading the authors to conclude that the treatment approach should continue to be resection for presumed malignancy.

Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis (LPSPC) is a rare inflammatory cause of pancreatitis that can be indistinguishable from pancreatic cancer and may result in biliary obstruction (see Chapter 55A, Chapter 55B ). The hallmark of this diagnosis is an exuberant inflammatory process characterized histologically by fibrosis and a large population of plasma cells, and in many patients it is associated with elevated serum IgG4 levels (Yoshida et al, 1995). Patients usually are seen with painless jaundice and a pancreatic mass. Radiographic studies show biliary obstruction due to the pancreatic mass, which shows characteristics indistinguishable from pancreatic cancer (see Chapter 58b). Weber and colleagues (2003) published a series of patients presumed to have pancreas adenocarcinoma who were subsequently determined to have LPSCP. The pathologic characteristics of this inflammatory tumor includes 1) lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the pancreas, 2) interstitial fibrosis, 3) periductal inflammation, and 4) periphlebitis. Some have reported on the effectiveness of pancreatoduodenctomy in the treatment of this disease (Weber et al, 2003; Hardacre et al, 2003), but others have argued that preoperative diagnosis by evaluating serum IgG4 levels may avoid unnecessary pancreatic resection in these patients, who can often be successfully treated with systemic corticosteroids (Hughes et al, 2004).

It is now recognized that a similar process may involve the biliary tract without concomitant pancreatic disease (Ghazale et al, 2008). Such cases of IgG4-associated cholangitis are extremely difficult to distinguish from sclerosing cholangitis. In a recent report of 10 patients with this diagnosis, compared with 17 with PSC, the former had higher portal and lobular inflammatory scores (Deshpande et al, 2009).

As termed by Hadjis and colleagues in their original report in 1985, malignant masquerade has since been observed by many others. Table 48.2 records the reports in the literature since 1987 related to benign inflammatory lesions occurring in the extrahepatic biliary tree. The authors draw attention to the fact that these lesions should not be allowed to masquerade in the guise of malignant tumors, but it is equally important that bile duct malignancies are not mistaken for benign tumors.

Heterotopic Tissue

Symptomatic heterotopic tissue arising in the biliary tree is exceedingly rare. In 1967, Whittaker and colleagues first observed heterotopic gastric mucosa in a cystic duct that had obstructed the gallbladder. Welling and colleagues (1970) have since recorded a similar mucosal mass obstructing the CBD at the level of the cystic duct. Kalman and colleagues (1981) reported a 1-cm papillary tumor arising in the CHD, which on microscopic examination demonstrated gastric fundal mucosa replacing the full thickness of the bile duct wall.

Heterotopic gastric mucosa occurring at the ampulla of Vater was observed to be the basis for biliary tract obstruction by Blundell and colleagues (1982). Although occurrence elsewhere in the GI tract is well documented, this appears to be the first documented ampullary obstruction secondary to heterotopic gastric mucosa. A more recent report documented a case of heterotopic gastric tissue causing biliary tract obstruction that was clinically indistinguishable from cholangiocarcinoma (Quispel et al, 2005).

Kalman and colleagues (1981) cite two hypotheses for the etiology of heterotopia: First, metaplasia with heterotopic differentiation is suggested. Several authors have described metaplastic gastric replacement of the gallbladder mucosa in cases of chronic cholecystitis; usually the metaplastic glands resemble pyloric and Brunner glands, whereas specialized chief and parietal cells are absent. A second, perhaps more tenable theory is one based upon the observation that embryologically, the epithelial lining of the foregut together with parenchyma of the liver and pancreas all arise from the same primitive endoderm, as discussed previously. Kalman states that because of the “common origin of these structures lined by multipotential cells capable of differentiation along several cell lines, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the heterotopic gastric replacement may have resulted from congenitally replaced tissue.”

Heterotopic pancreatic tissue has been observed to occur from the stomach to the ileum, as well as in the omentum, spleen, gallbladder, and CBD. Seven cases have been reported in which heterotopic pancreatic tissue was found in the CBD or ampulla of Vater (Barbosa et al, 1946; Weber et al, 1968; Sabini et al, 1970; Laughlin et al, 1983). Al-Shraim and colleagues (2010) recently reported a case of ectopic pancreatic tissue in the gallbladder associated with chronic cholecystitis.

Aisner SC, Khaneja S, Ramirez O. Multiple granular cell tumors of the gallbladder and biliary tree: report of a case. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982;106:470-471.

Akaydin M, et al. Tubulovillous adenoma in the common bile duct causing obstructive jaundice. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72(4):450-454.

Al-Shraim M, et al. Pancreatic heterotopia in the gallbladder associated with chronic cholecystitis: a rare combination. JOP. 2010;11(5):464-466.

Altavilla G, et al. Granular cell tumor of the intrapancreatic common bile duct: one case report and review of literature. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2004;28(3):171-176.

Angeles-Angeles A, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Larriva-Sahd J. Primary carcinoid of the common bile duct. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:341-344.

Archambault H, Archambault R. Leiomyoma of the common bile duct. Arch Surg. 1952;64:531-534.

Archie JP, Murray HM. Benign polypoid adenoma of the ampulla of Vater. Arch Surg. 1978;113:180-181.

Are C, et al. Differential diagnosis of proximal biliary obstruction. Surgery. 2006;140(5):756-763.

Armin A, Connelly EM, Rowden F. An immunoperoxidase investigation of S-100 protein in granular cell myoblastoma: evidence for Schwann cell derivation. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;79:37-44.

Assor D. Granular cell myoblastoma involving the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 1979;137:180-181.

Austin EH, et al. Solitary hepatic cyst and benign bile duct polyp: a heretofore unheralded association. Surgery. 1981;89:359-363.

Baggenstoss AH. Major duodenal papilla. Arch Pathol. 1983;26:353-368.

Bahuth JJ, Winkley JH. Benign tumor of the common bile duct. Calif Med. 1966;104:307-309.

Balart LA, Hines C, Mitchell W. Granular cell schwannoma of the extrahepatic biliary system. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:297-300.

Barbosa JJ, Dockerty M, Waugh J. Pancreatic heterotopia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1946;82:527-547.

Barker EM, Winkler M. Permanent-access hepaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg. 1984;71:188-191.

Barron-Rodriguez L, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the common bile duct: evidence for its origin in metaplastic endocrine cells. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1073-1076.

Beazley RM, et al. Clinicopathological aspects of high bile duct cancer. Ann Surg. 1984;199:623-636.

Bergdahl L. Carcinoid tumours of the biliary tract. Aust N Z J Surg. 1976;46:136-138.

Bergdahl L, Andersson A. Benign tumors of the papilla of Vater. Am Surg. 1980;46:563-566.

Bickerstaff DR, Ross WB. Carcinoid of the biliary tree. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1987;32:48-51.

Binkley CE, Eckhauser FE, Colletti LM. Unusual cases of benign biliary strictures with cholangiographic features of cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6(5):676-681.

Blumgart LH, et al. Surgical approaches to cholangiocarcinoma at confluence of hepatic ducts. Lancet. 1984;i:66-70.

Blundell CR, Kanun CS, Earnest DL. Biliary obstruction by heterotopic gastric mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:111-114.

Boraschi P, et al. Solitary hilar biliary adenoma: MR imaging and MR cholangiography features with pathologic correlation. Dig Liver Dig. 2007;39(11):1031-1034.

Borner P. Eine papillomatose der intra und extrahepatischen gallenwege. Z Krebsforsch. 1960;63:474-480.

Boyden EA. The pars intestinalis of the common bile duct as viewed by the older anatomists (Vesalius, Glisson, Bianchi, Vater, Haller, Santorini, etc). Anat Record (Hoboken). 1936;66:217-232.

Boyden EA. The anatomy of the choledochoduodenal junction in man. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;104:641-652.

Brown JO, Echenberg RJ. Mucosal reduplications associated with the ampullary portion of the major duodenal papilla in humans. Anat Record (Hoboken). 1964;150:293-302.

Brown WM, Henderson JM, Kennedy JC. Carcinoid tumor of the bile duct. Am Surg. 1990;56:343-346.

Bumin L, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the biliary duct. Int Surg. 1990;75:262-264.

Burhans R, Myers RT. Benign neoplasms of the extrahepatic biliary ducts. Am Surg. 1971;37:161-166.

Butler JD, Brown K. Granular cell tumor of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Am Surg. 1998;64:1033-1036.

Butterly LF, et al. Biliary granular cell tumor: a little-known curable bile duct neoplasm of young people. Surgery. 1988;103:328-334.

Byrne DJ, et al. Extraheptic biliary cystadenoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1989;34:223-224.

Byrne MF, et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of bile duct lesions. Endoscopy. 2004;36(8):715-719.

Caroli J. Papillomes et papillomatoses de la voie bilaire principale. Rev Med Chir Mal Foie. 1959;34:191-230.

Cattell RB, Pyrtek LJ. Premalignant lesions of the ampulla of Vater. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1950;90:21-30.

Cattell RB, Braasch JW, Kahn F. Polypoid epithelial tumors of the bile ducts. N Engl J Med. 1962;266:57-61.

Chae BW, et al. Villous adenoma of the bile ducts: a case report and a review of the reported cases in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40(1):84-89.

Chandrasoma P, Fitzgibbons P. Granular cell tumor of the intrapancreatic common bile duct. Cancer. 1984;53:2178-2182.

Cheng MS, et al. Case report: two cases of biliary papillomatosis with unusual associations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(5):464-467.

Cheslyn-Curtis S, et al. Granular cell tumor of the common bile duct. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:961-963.

Chittal SM, Ra PM. Carcinoid of the cystic duct. Histopathology. 1989;15:643-646.

Chu PT. Benign neoplasms of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Arch Pathol. 1950;50:84-97.

Coggins RP. Granular-cell myoblastoma of common bile duct: report of a case with autopsy findings. Arch Pathol. 1952;54:398-402.

Corvera CU, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of proximal biliary strictures masquerading as hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):862-869.

Curry B, Gray N. Visceral neurofibromatosis. Br J Surg. 1972;59:494-496.

D’Abrigeon G, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in papillomatosis of the bilie ducts: analysis of five cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(3):237-243.

Dancygier H, et al. Somatostatin-containing cells in the extrahepatic biliary tract of humans. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:892-896.

Davies AJ. Carcinoid tumor (argentaffinomata). Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1959;25:277-280.

Dayton MT, Longmire WPJr, Tompkins RK. Caroli’s disease: a premalignant condition? Am J Surg. 1983;145:41-48.

Deshpande V, et al. IgG4-associated cholangitis: a comparative histologic and immunophenotypic study with primary sclerosing cholangitis on liver biopsy material. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1287-1295.

Dewar J, et al. Granular cell myoblastoma of the common bile duct treated by biliary drainage and surgery. Gut. 1981;22:70-76.

Dowdy GS, Waldron GW, Brown WF. Surgical anatomy of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system. Arch Surg. 1961;84:93-110.

Dowdy GS, et al. Benign tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts: report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1962;85:503-513.

Dumortier J, et al. Successful liver transplantation for diffuse biliary papillomatosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35(4):542-543.

Duncan JT, Wilson H. Benign tumor of the common bile duct. Ann Surg. 1957;145:271-274.

Dursi JF, et al. Granular cell myoblastoma of the common bile duct: report of a case and review of the literature. Rev Surg. 1975;32:305-310.

Eisen RN, Kirby WM, O’Quinn JL. Granular cell tumor of the biliary tree: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:460-465.

Eiss S, MiMaio D, Caedo JP. Multiple papillomas of the entire biliary tract: case report. Ann Surg. 1960;152:320-324.

Eloubeidi MA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(3):209-213.

El Rassi ZS, et al. Endocrine tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts: pathological and clinical aspects, surgical management and outcome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51(59):1295-1300.

Farris KB, Faust BF. Granular cell tumors of the biliary ducts. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1979;103:510-512.

Felekouras E, et al. Malignant carcinoid tumor of the cystic duct: a rare cause of bile duct obstruction. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:640-646.

Fernandez JMC, Gonzales-Bueno CM. Leiomyoma of the ampulla of Vater. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1974;47:165-172.

Ferri Romero J, et al. Tumor de celulas granulosas en la vía hiliar una localizacíon poco fecuente. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1994;85:217-219.

Ferrone CR, et al. Extrahepatic bile duct carcinoid tumors: malignant biliary obstruction with a good prognosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(2):357-361.

Fletcher ND, Wise PE, Sharp KW. Common bile duct papillary adenoma causing obstructive jaundice: case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2004;70(5):448-452.

Foulner D. Granular cell tumor of the biliary tree: the sonographic appearance. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:503-504.

Gallagher PJ, Millis RR, Michinson MJ. Congenital dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts with cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:804-808.

Gerhards MF, et al. Incidence of benign lesions in patient resected for suspicious hilar obstruction. Br J Surg. 2001;88(1):48-51.

Gerlock AJJ, Muhletaler CA. Primary common bile duct carcinoid. Gastrointest Radiol. 1979;4:263-264.

Gertsch P, et al. Multiple tumors of the biliary tract. Am J Surg. 1990;159:386-388.

Ghazale A, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(3):706-715.

Golematis B, et al. Sclerosing cholangitis of the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct. Mount Sinai J Med. 1982;49:38-40.

Goo JC, et al. A case of leiomyoma in the common bile duct. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:77-81.

Goodman ZD, Albores-Saavedra J, Lundblad DM. Somatostatinoma of the cystic duct. Cancer. 1984;53:498-502.

Gouma DJ, et al. Intrahepatic biliary papillomatosis. Br J Surg. 1984;71:72-74.

Graziadei IW, et al. Hepatology. 1999;30(5):1121-1127.

Hadjis NS, Collier NA, Blumgart LH. Malignant masquerade at the hilum of the liver. Br J Surg. 1985;72:659-661.

Haith EE, Kepes JJ, Holder TM. Inflammatory pseudotumor involving the common bile duct of a six-year-old boy: successful pancreatico-duodenectomy. Surgery. 1964;56:436-441.

Hao L, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the common bile duct producing gastrin and serotonin. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:63-65.

Hardacre JM, et al. Results of pancreaticoduodenectomy for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2003;237(6):853-858.

Helling TS, Strobach RS. The surgical challenge of papillary neoplasia of the biliary tract. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:290-298.

Hermina M, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the cystic duct. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195(10):707-709.

Heuser LS, Polk HCJr. Proximal hepatic duct lesion. Surgical Rounds. 1983:48-52.

Honjo Y, et al. Extrahepatic biliary schwannoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(11):2221-2226.

Hubens G, et al. Papillomatosis of the intra and extrahepatic bile ducts with involvement of the pancreatic duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:413-418.

Hughes DB, Grobmeyer SR, Brennan MF. Preventing pancreaticoduodenectomy for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis: cost-effectiveness of IgG4. Pancreas. 2004;29(2):67.

Hutson D, et al. Balloon dilatation of biliary strictures through a choledochojejunocutaneous fistula. Ann Surg. 1984;199:637-647.

Ikei S, et al. Adenofibromyomatous hyperplasia of the extrahepatic bile duct: a report of two cases. Jpn J Surg. 1989;19:576-582.

Ishak KG, et al. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1977;39:322-338.

Jain KM, et al. Granular cell tumor of the common bile duct. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;71:401-407.

Jones AW, Shreeve DR. Congenital dilatation of intrahepatic biliary ducts with cholangiocarcinoma. Br Med J. 1970;2:277-278.

Judge DM, Dickman PS, Trapukdi S. Nonfunctioning argyrophilic tumor (apudoma) of the hepatic duct. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;66:40-50.

Jutte DL, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the biliary system. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;32:763-769.

Kalman PG, Stone RM, Philips MJ. Heterotopic gastric tissue of the bile duct. Surgery. 1981;89:384-386.

Karakozis S, et al. Granular cell tumors of the biliary tree. Surgery. 2000;128:113-115.

Khalid K, et al. Granular cell tumor of the ampulla of Vater. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51(1):36-38.

Khan AN, et al. Sonographic features of mucinous biliary papillomatosis: case report and review of imaging findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26:141-154.

Kienzle HF, Bahr R, Stolte M. Granularzell tumor des ductus choledochus. Dstch Med Wochenschr. 1986;111:197.

Kittredge RD, Baer JW. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography: problems in interpretation. Am J Roentgenol, Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;125:35-46.

Koea J, et al. Differential diagnosis of stenosing lesions at the hepatic hilus. World J Surg. 2004;28:466-470.

Kozuka S, Tsubone M, Hachisuka K. Evolution of carcinoma in the extrahepatic bile ducts. Cancer. 1984;54:65-72.

Kune GA, Polgar V. Leiomyoma of the common bile duct causing obstructive jaundice. Med J Aust. 1976;1:698-699.

Kunisaki SM, et al. Mirizzi syndrome secondary to an adenoma of the cystic duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:159-162.

Lai R, et al. EUS in multiple biliary papillomatosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(1):121-125.

Lam CM, et al. Biliary papillomatosis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1712-1715.

Langnas AN, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: the emerging role for liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(9):1136-1141.

Laughlin E, Keown M, Jackson J. Heterotopic pancreas obstructing the ampulla of Vater. Arch Surg. 1983;118:979-980.

Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:924-933.

Leriche R. Volumineuse tumeur papillomateuse du choledoque chez un enfant. Lyons Chir. 1934;31:598-602.

Leroy JP, et al. Carcinome biliaire developpe sur maladie de. Caroli. Arch Anat Pathol Cytol. 1979;27:121-125.

Levy AD, et al. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the gallbladder and extra-hepatic bile ducts: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:387-413.

Lewis WD, et al. Biliary duct granular cell tumor: a rare but surgically curable benign tumor. HPB Surg. 1993;6:311-317.

Li AKC, Warshaw AL, Malt RA. Pseudotumor at the confluence of the hepatic ducts as a pitfall of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;152:59-62.

Ligato S, et al. Primary carcinoid tumor of the common hepatic duct: a rare case with immunohistochemical and molecular findings. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:543-546.

Lindner HH, Green RB. Embryology and surgical anatomy of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Surg Clin N Am. 1964;44:1273-1284.

Little JM, Gibson AAM, Kay AW. Primary common bile duct carcinoid. Br J Surg. 1968;55:147-149.

LiVolsi VA, et al. Granular cell tumors of the biliary tract. Arch Pathol. 1973;95:13-17.

Lochan R, et al. Granular cell tumor as an unusual cause of obstruction at the hepatic hilum: report of a case. Surgery Today. 2006;36:934-936.

Loh A, Kamar S, Dickson GH. Solitary benign papilloma (papillary adenoma) of the cystic duct: a rare cause of biliary colic. Br J Clin Pract. 1994;48:167-168.

Lukes PJ, et al. Premalignant lesions of the papilla of Vater and the common bile duct. Acta Chir Scand. 1979;145:545-548.

KF Ma, et al. Clinical and radiological features of biliary papillomatosis. Australas Radiol. 2000;44(2):169-173.

MacKenzie DJ, et al. Granular cell tumor of the biliary system. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;23:50-56.

Madden JJ, Smith GW. Multiple biliary papillomatosis. Cancer. 1974;34:1316-1320.

Mahour GH, Wakim KG, Ferris DE. The common bile duct in man: its diameter and circumference. Ann Surg. 1967;165:415-419.

Mandeville GA, Stawski WS. Obstructing leiomyoma of the common bile duct bifurcation simulating a Klatskin tumor. Am Surg. 1991;57:676-678.

Mandujano-Vera G, et al. Gastrinoma of the common bile duct: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a case. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:321-324.

Manstein ME, et al. Granular cell tumor of the common bile duct. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:938-942.

Marsh JL, Dahms B, Longmire WPJr. Cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the biliary system. Arch Surg. 1974;109:41-43.

Martin RC, Stulc JP. Multifocal granular cell tumor of the biliary tree: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:238-240.

Mauro MA, Jacques PF. Granular cell tumors of the esophagus and common bile duct. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1981;32:254-256.

McIntyre JA, Pay-Zen C. Adenoma of the common bile duct causing obstructive jaundice. Can J Surg. 1968;11:215-218.

Mendes Ribeiro HK, Woodham C. CT demonstration of an unusual cause of biliary obstruction in a patient with peripheral neurofibromatosis. Clin Radiol. 2000;55(10):796-798.

Meng WCS, et al. Laser therapy for multiple biliary papillomatosis via choledochoscopy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;67:664-666.

Miyano T, et al. Adenoma and stone formation of the biliary tract in puppies that had choledochopancreatic anastomosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:539-542.

Moore S, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver arising in biliary cystadenocarcinoma: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features with review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:267-275.

Mukai H, et al. Tumors of the papilla and distal common bile duct. Diagnosis and staging by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995;5:763-772.

Mulhollan TJ, et al. Granular cell tumor of the biliary tree: letters to the editor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:204-209.

Murray MR. Cultural characteristics of three granular cell myoblastomas. Cancer. 1951;4:857-865.

Nahas SC, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the common bile duct: report of a case. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1998;53(1):26-28.

Nasu S, Sakurai M, Miyagi T. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in intrahepatic bile duct cyst. Nihonrinsho. 1971;29:3075-3081.

Nesi G, et al. Well-differentiated endocrine tumor of the distal common bile duct: a case study and literature review. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:104-111.

Oden B. Neurinoma of the common bile duct. Acta Chir Scand. 1955;108:393-397.

Ohta H, et al. Biliary papillomatosis with point mutation of K-ras gene arising in congenital choledochal cyst. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1209-1212.

Oren R, et al. Localized primary sclerosing cholangitis mimicking a cholecystectomy stricture relieved by an endoprosthesis. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:482-484.

Orenstein HH, Brenner LH, Nay HR. Granular cell myoblastoma of the extrahepatic biliary system. Am J Surg. 1984;147:827-831.

Padfield CJH, Ansell ID, Furness PN. Mucinous biliary papillomatosis: a tumor in need of wider recognition. Histopathology. 1988;13:687-694.

Paskin DL, Hull JD, Cookson PJ. Granular cell myoblastoma: a comprehensive review of 15 years experience. Ann Surg. 1972;175:501-504.

Pilz E. Über ein karzinoid des ductus choledochus. Zentrabl Chir. 1961;86:1588-1590.

Pongtippan A, et al. Granular cell tumor of the common bile duct: a case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83:S7-S11.

Ponka A, Laasonen L, Strengell-Usanov L. Angioleiomyoma of the common bile duct. Acta Med Scand. 1983;213:407-410.

Quispel R, et al. Heterotopic gastric tissue mimicking malignant biliary obstruction. Gastorintest Endosc. 2005;62(1):170-172.

Raia AA, et al. Myoblastoma of the common bile duct: presentation of a case. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1978;24:379-380.

Rugge M, et al. Primary carcinoid tumor of the cystic and common bile ducts. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:802-807.

Sabini A, et al. Heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the common bile duct or ampulla of Vater. Am Surg. 1970;36:662-666.

Sanchez JA, Nauta RJ. Resection of granular cell tumor at the hepatic confluence: a precarious location for benign tumor. Am Surg. 1991;57:446-450.

Santorini JD, 1724: Observationes Anatomicae. Venetiis, apus J.B: Recurti.

Sarma DP, Rodriguez FH, Hoffman EO. Paraganglioma of the hepatic duct. J Southern Med Assoc. 1980;73:1677-1678.

Savage A, Devitt P. Granular cell myoblastoma of the biliary tree. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:574-577.

Schiewe R, Baudisch E, Erhhardt G. Angeborene intrahepatische gallengangzyste mit Steinbildung und maligner entartung. Bruns Beitr Klin Chir. 1968;216:264-271.

Schroyens W, Bleiberg H, Peetrons P. Pseudotumoral primary sclerosing cholangitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1987;1:436-444.

Short WF, et al. Biliary cystadenoma. Arch Surg. 1971;102:78-80.