Interconnecting the pRB, p53, and mTORC1 Pathways

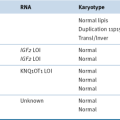

The pRB Tumor Suppressor Pathway

The p53 Tumor Suppressor Pathway

pRB and p53 Pathways in Action: Cellular Senescence

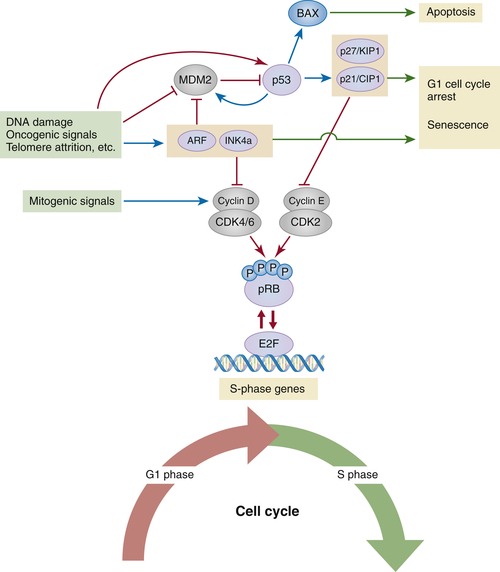

The mTORC1-Dependent Pathways

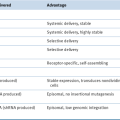

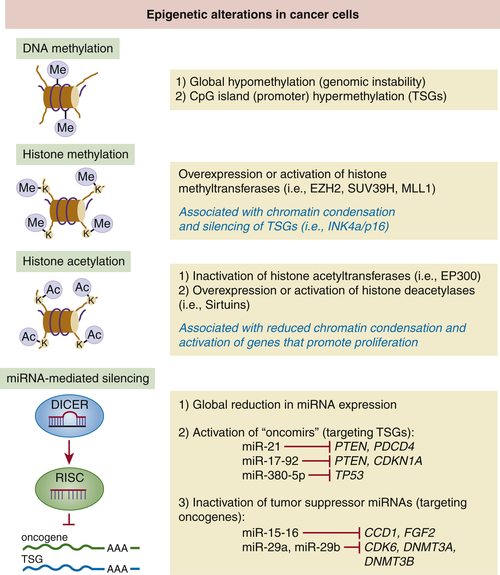

Epigenetic Modifications and Tumor Suppression

DNA Methylation

Histone Modifications

Micro-RNAs

Conclusions

1. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation . Cell . 2011 ; 144 : 646 – 674 .

2. Cancer genes and the pathways they control . Nat Med . 2004 ; 10 : 789 – 799 .

3. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer . Nature . 2004 ; 432 : 316 – 323 .

4. Principles of tumor suppression . Cell . 2004 ; 116 : 235 – 246 .

5. DNA damage, aging, and cancer . N Engl J Med . 2009 ; 361 : 1475 – 1485 .

6. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer . Nature . 2001 ; 411 : 366 – 374 .

7. P53 in cancer: a paradigm for modern management of cancer . Surgeon . 2005 ; 3 : 197 – 205 .

8. A continuum model for tumour suppression . Nature . 2011 ; 476 : 163 – 169 .

9. Architecture of inherited susceptibility to common cancer . Nat Rev . 2010 ; 10 : 353 – 361 .

10. Cancer genetics: from Boveri and Mendel to microarrays . Nat Rev . 2001 ; 1 : 77 – 82 .

11. Suppression of malignancy by cell fusion . Nature . 1969 ; 223 : 363 – 368 .

12. Chromosome analysis of two related heteroploid mouse cell lines by quinacrine fluorescence . J Cell Sci . 1973 ; 12 : 263 – 274 .

13. The analysis of malignancy by cell fusion. I. Hybrids between tumour cells and L cell derivatives . J Cell Sci . 1971 ; 8 : 659 – 672 .

14. Human cancer syndromes: clues to the origin and nature of cancer . Science . 1997 ; 278 : 1043 – 1050 .

15. Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer . Nat Rev . 2001 ; 1 : 157 – 162 .

16. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma . Nature . 1983 ; 305 : 779 – 784 .

17. Chromosomal deletion and retinoblastoma . N Engl J Med . 1976 ; 295 : 1120 – 1123 .

18. A human DNA segment with properties of the gene that predisposes to retinoblastoma and osteosarcoma . Nature . 1986 ; 323 : 643 – 646 .

19. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene . Nat Rev . 2008 ; 8 : 671 – 682 .

20. Tailoring to RB: tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response . Nat Rev . 2008 ; 8 : 714 – 724 .

21. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex . Nat Rev . 2009 ; 9 : 749 – 758 .

22. The role of mutant p53 in human cancer . J Pathol . 2011 ; 223 : 116 – 126 .

23. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(∗)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations . Nat Genet . 2002 ; 31 : 55 – 59 .

24. PALB2, which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene . Nat Genet . 2007 ; 39 : 165 – 167 .

25. Evaluating the effects of imputation on the power, coverage, and cost efficiency of genome-wide SNP platforms . Am J Hum Genet . 2008 ; 83 : 112 – 119 .

26. Calibrating the performance of SNP arrays for whole-genome association studies . PLoS Genet . 2008 ; 4 : e1000109 .

27. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis . Nature . 2005 ; 436 : 725 – 730 .

28. Subtle variations in Pten dose determine cancer susceptibility . Nat Genet . 2010 ; 42 : 454 – 458 .

29. Altered gene expression in morphologically normal epithelial cells from heterozygous carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations . Cancer Prev Res (Phila) . 2010 ; 3 : 48 – 61 .

30. Retention of wild-type p53 in tumors from p53 heterozygous mice: reduction of p53 dosage can promote cancer formation . EMBO J . 1998 ; 17 : 4657 – 4667 .

31. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer . Nat Rev . 2001 ; 1 : 222 – 231 .

32. G1 cell-cycle control and cancer . Nature . 2004 ; 432 : 298 – 306 .

33. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm . Nat Rev . 2009 ; 9 : 153 – 166 .

34. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives . Biochim Biophys Acta . 1998 ; 1378 : F115 – F177 .

35. Tumor suppression by Ink4a-Arf: progress and puzzles . Curr Opin Genet Dev . 2003 ; 13 : 77 – 83 .

36. Oncogene- and tumor suppressor gene-mediated suppression of cellular senescence . Semin Cancer Biol . 2011 ; 21 ( 6 ) : 367 – 376 .

37. p53 and E2f: partners in life and death . Nat Rev . 2009 ; 9 : 738 – 748 .

38. The essence of senescence . Genes Dev . 2010 ; 24 : 2463 – 2479 .

39. Short telomeres limit tumor progression in vivo by inducing senescence . Cancer Cell . 2007 ; 11 : 461 – 469 .

40. Pro-senescence therapy for cancer treatment . Nat Rev . 2011 ; 11 : 503 – 511 .

41. The power and the promise of oncogene-induced senescence markers . Nat Rev . 2006 ; 6 : 472 – 476 .

42. BRAF(E600) in benign and malignant human tumours . Oncogene . 2008 ; 27 : 877 – 895 .

43. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi . Nature . 2005 ; 436 : 720 – 724 .

44. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth . Genes Dev . 2009 ; 23 : 537 – 548 .

45. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship . Nat Rev . 2006 ; 6 : 729 – 734 .

46. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations . Nat Rev . 2009 ; 9 : 550 – 562 .

47. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism . Nat Rev . 2011 ; 11 : 85 – 95 .

48. p53 and metabolism . Nat Rev . 2009 ; 9 : 691 – 700 .

49. Cancer epigenetics . CA Cancer J Clin . 2010 ; 60 : 376 – 392 .

50. The history of cancer epigenetics . Nat Rev . 2004 ; 4 : 143 – 153 .

51. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology . Nat Med . 2011 ; 17 : 330 – 339 .

52. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers . Nat Rev . 2006 ; 6 : 857 – 866 .

53. The microcosmos of cancer . Nature . 2012 ; 482 : 347 – 355 .

54. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy . Nat Rev . 2011 ; 11 : 849 – 864 .