Chapter 7 Toxicology

Descriptive toxicology focuses on toxicity testing with the intent of defining the degree of risk associated with substances.

Descriptive toxicology focuses on toxicity testing with the intent of defining the degree of risk associated with substances. Environmental toxicology involves the detection and understanding of environmental pollutants and their effects on humans and other organisms.

Environmental toxicology involves the detection and understanding of environmental pollutants and their effects on humans and other organisms. Forensic toxicology is primarily concerned with detection and quantification of toxic substances for legal purposes.

Forensic toxicology is primarily concerned with detection and quantification of toxic substances for legal purposes. Mechanistic toxicology is focused on determining the mechanisms by which substances exert toxic effects.

Mechanistic toxicology is focused on determining the mechanisms by which substances exert toxic effects. Regulatory toxicology uses toxicologic data to establish policies regarding exposure limits for toxic substances.

Regulatory toxicology uses toxicologic data to establish policies regarding exposure limits for toxic substances.General Principles

Terminology

Toxin, by strict definition, is a poison of biologic origin that does not have the ability to replicate. However, the term toxin has been used more loosely. For example, environmental toxin has been used to describe toxic substances of nonbiologic origin.

Toxin, by strict definition, is a poison of biologic origin that does not have the ability to replicate. However, the term toxin has been used more loosely. For example, environmental toxin has been used to describe toxic substances of nonbiologic origin. Toxicant is a general term that refers to any harmful substance and is generally interchangeable with poison.

Toxicant is a general term that refers to any harmful substance and is generally interchangeable with poison.General Mechanisms of Toxicity

Physical. The physical presence of the toxicant triggers reactions that are harmful (e.g., asbestos fibers in the lung).

Physical. The physical presence of the toxicant triggers reactions that are harmful (e.g., asbestos fibers in the lung). Chemical. Toxicants react chemically with the tissues or body fluids such as blood to produce harmful effects (e.g., strong acids or bases cause burns).

Chemical. Toxicants react chemically with the tissues or body fluids such as blood to produce harmful effects (e.g., strong acids or bases cause burns). Pharmacologic. Toxicants interact with endogenous pharmacologic pathways, resulting in inhibition or overstimulation (e.g., botulinum toxin inhibits release of acetylcholine to cause paralysis).

Pharmacologic. Toxicants interact with endogenous pharmacologic pathways, resulting in inhibition or overstimulation (e.g., botulinum toxin inhibits release of acetylcholine to cause paralysis). Biochemical. Toxicant reacts biochemically with cellular constituents to produce cellular damage (e.g., venom of many snakes contains phospholipases that destroy cell membranes).

Biochemical. Toxicant reacts biochemically with cellular constituents to produce cellular damage (e.g., venom of many snakes contains phospholipases that destroy cell membranes). Genomic (genotoxic). Toxicant alters the genetic material of the cell, resulting in disruption of function. Genotoxic substances may be mutagenic or carcinogenic.

Genomic (genotoxic). Toxicant alters the genetic material of the cell, resulting in disruption of function. Genotoxic substances may be mutagenic or carcinogenic. Mutagenic (carcinogenic). Toxicants alter DNA structure or function sufficiently to cause mutations (benzene) or initiate and promote the development of cancers (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzo[a]pyrene, found in cigarette smoke).

Mutagenic (carcinogenic). Toxicants alter DNA structure or function sufficiently to cause mutations (benzene) or initiate and promote the development of cancers (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzo[a]pyrene, found in cigarette smoke).Target Organs

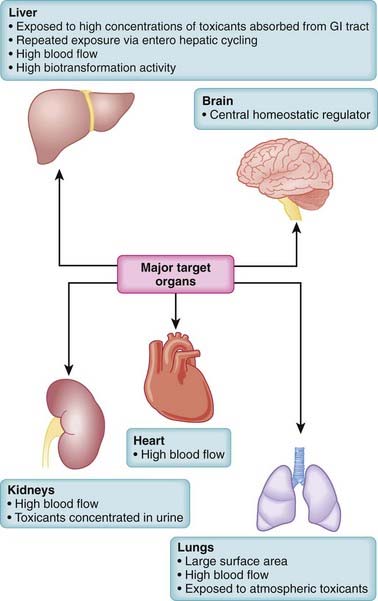

Toxicity may be systemic, affecting the whole body, or it may be largely confined to select target organs, the so-called toxic effect organs. Some organs, such as the liver, brain, lungs, heart, and kidney, play a central role in poisonings (Figure 7-1). When toxicity is site specific, the word toxic is preceded by an indication of the specific target organ. Thus, hepatotoxicity refers to effects on the liver, nephrotoxicity refers to effects on the kidney, ototoxicity refers to effects on the auditory system, and so on. A number of factors interact to determine the susceptibility of organs to toxic effects. These include the organ’s anatomic location, blood flow, metabolic processes and activity, affinity for the toxicant, and capacity for self-repair. Major toxic effect organs include the following:

Liver. The liver is exposed to a high concentration of toxic substances. Orally absorbed toxicants are presented first to the liver via the portal circulation. The liver also receives a large proportion of systemic blood flow. Enterohepatic cycling extends exposure to toxicants excreted through the bile. The high metabolic activity of the liver also results in the generation of reactive intermediates that may have toxic actions.

Liver. The liver is exposed to a high concentration of toxic substances. Orally absorbed toxicants are presented first to the liver via the portal circulation. The liver also receives a large proportion of systemic blood flow. Enterohepatic cycling extends exposure to toxicants excreted through the bile. The high metabolic activity of the liver also results in the generation of reactive intermediates that may have toxic actions. Kidney. The kidney receives a high proportion of the cardiac output. Many toxic substances are excreted by the kidney. These toxicants are concentrated in the urine as fluid is reabsorbed from the renal tubule.

Kidney. The kidney receives a high proportion of the cardiac output. Many toxic substances are excreted by the kidney. These toxicants are concentrated in the urine as fluid is reabsorbed from the renal tubule. Heart. The total blood volume passes through the heart. Thus it is exposed to all blood-borne toxicants.

Heart. The total blood volume passes through the heart. Thus it is exposed to all blood-borne toxicants. Lungs. The lungs represent an extremely large surface area for interaction with toxicants, particularly those that are airborne. The total cardiac output passes through the lungs, so blood-borne toxicants are also distributed extensively to the lungs.

Lungs. The lungs represent an extremely large surface area for interaction with toxicants, particularly those that are airborne. The total cardiac output passes through the lungs, so blood-borne toxicants are also distributed extensively to the lungs.Risk Assessment

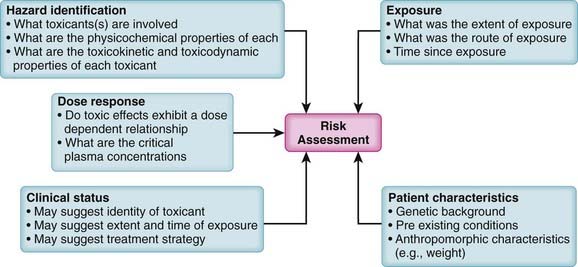

Because virtually all substances are potentially toxic, key questions in toxicology are how much risk is associated with a particular substance and under what conditions does this risk become apparent? In addition, the level of acceptable risk will vary. In some circumstances, very toxic substances (e.g., anticancer drugs) are used therapeutically despite their known toxic effects because the benefits of such treatments outweigh the risks. Accordingly, risk assessment is a primary consideration in the management of toxic events (Figure 7-2).

Key factors contributing to risk assessment include the following:

Hazard identification. What substances are involved and what are the adverse effects of each substance? Knowledge of the physicochemical properties, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics of the suspected toxicant(s) is invaluable in designing treatment strategies.

Hazard identification. What substances are involved and what are the adverse effects of each substance? Knowledge of the physicochemical properties, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics of the suspected toxicant(s) is invaluable in designing treatment strategies. Dose response. Is there a known dose response relationship for the toxic effects of the toxicant? Do toxic effects mirror plasma concentrations? At what dose (concentration) do toxic effects appear?

Dose response. Is there a known dose response relationship for the toxic effects of the toxicant? Do toxic effects mirror plasma concentrations? At what dose (concentration) do toxic effects appear? Exposure assessment. Exposure assessment is a key process in determining the urgency and strategy for treatment of toxic events. Exposure assessment includes estimation of the following:

Exposure assessment. Exposure assessment is a key process in determining the urgency and strategy for treatment of toxic events. Exposure assessment includes estimation of the following:

Route of exposure. The route of exposure is an important determinant of both the extent and rate of absorption of the toxicant. For example, dermal exposure is generally associated with reduced rates and extent of absorption compared with oral ingestion or inhalation.

Route of exposure. The route of exposure is an important determinant of both the extent and rate of absorption of the toxicant. For example, dermal exposure is generally associated with reduced rates and extent of absorption compared with oral ingestion or inhalation. Time since exposure. An estimate of the time since the exposure will be helpful in estimating the following:

Time since exposure. An estimate of the time since the exposure will be helpful in estimating the following:

Clinical status. In many cases, information about the degree and time of exposure may be lacking. In such cases, careful determination of the clinical status of the patient coupled with knowledge of potential hazards can assist in determining the type of toxicant (e.g., recognition of anticholinergic effects of mushroom poisoning), the suspected time course, and the treatment protocol. In addition, recognition of compromised airway, circulatory, or neural function requires immediate supportive measures.

Clinical status. In many cases, information about the degree and time of exposure may be lacking. In such cases, careful determination of the clinical status of the patient coupled with knowledge of potential hazards can assist in determining the type of toxicant (e.g., recognition of anticholinergic effects of mushroom poisoning), the suspected time course, and the treatment protocol. In addition, recognition of compromised airway, circulatory, or neural function requires immediate supportive measures. Patient characteristics. The specific characteristics such as anthropomorphic characteristics, genetic background, and preexisting conditions of each patient also factor into risk assessment. Some (e.g., weight) may affect the course of poisoning indirectly, whereas others may have a more direct effect (e.g., alcoholism) by influencing the production or elimination of toxic substances. Genetic polymorphisms may affect absorption, biotransformation, or elimination of toxicants.

Patient characteristics. The specific characteristics such as anthropomorphic characteristics, genetic background, and preexisting conditions of each patient also factor into risk assessment. Some (e.g., weight) may affect the course of poisoning indirectly, whereas others may have a more direct effect (e.g., alcoholism) by influencing the production or elimination of toxic substances. Genetic polymorphisms may affect absorption, biotransformation, or elimination of toxicants.General Strategies for Management of Toxic Events

Antibodies that neutralize toxicants or prevent their distribution to target organs (e.g., antivenin for snake bites)

Antibodies that neutralize toxicants or prevent their distribution to target organs (e.g., antivenin for snake bites) Compounds that sequester the toxicant, prevent its distribution, and promote its excretion (e.g., heavy metal chelators)

Compounds that sequester the toxicant, prevent its distribution, and promote its excretion (e.g., heavy metal chelators) Compounds that scavenge the toxicant to prevent its interaction with tissues (e.g., N-acetylcysteine [NAC] in acetaminophen poisoning)

Compounds that scavenge the toxicant to prevent its interaction with tissues (e.g., N-acetylcysteine [NAC] in acetaminophen poisoning) Treatments that act physiologically to oppose the actions of the toxicant (e.g., pressor agents to reverse hypotension)

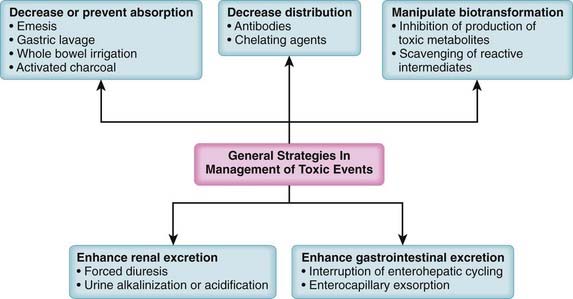

Treatments that act physiologically to oppose the actions of the toxicant (e.g., pressor agents to reverse hypotension)In addition to specific treatments, a number of generalized treatment strategies can be used in poisonings (Figure 7-3). These are toxicokinetic treatment strategies targeted at reducing or preventing the absorption of the toxicant, at reducing the distribution of the toxicant, at manipulating biotransformation to reduce formation of the toxicant, or at hastening excretion of the toxicant. These approaches rely heavily on the concepts of pharmacokinetics presented earlier, which will not be repeated here. These generalized approaches are very useful in situations in which there are no specific antidotes or the causative toxicant(s) and/or modes of action are not sufficiently well defined to allow application of a specific antidote.

Reduction or Prevention of Absorption

Gastric Lavage

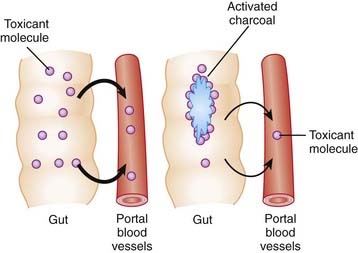

Activated Charcoal

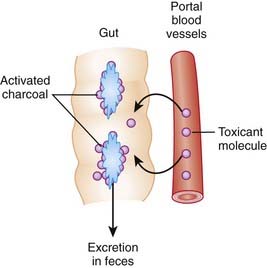

Activation of charcoal by oxidization increases its adsorptive surface area. The large surface area of charcoal is capable of adsorbing many toxicants, thus sequestering them in the gut. Because only free molecules are able to diffuse across membranes, reduction of the concentration of free toxicant in the gut by charcoal greatly reduces absorption into the bloodstream (Figure 7-4). This treatment is administered as a slurry of the activated charcoal powder.

Manipulation of Distribution

General mechanisms of action

General mechanisms of action

Antibodies

Antibodies

Edetate calcium disodium (calcium disodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EDTA)

Edetate calcium disodium (calcium disodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EDTA)

Dimercaprol (British antilewisite)

Dimercaprol (British antilewisite)

Deferoxamine

Deferoxamine

Enhancement of Toxin Excretion

Renal Excretion

Forced Diuresis

Forced diuresis involves administration of diuretic agents and isotonic saline to increase glomerular filtration rate and urine flow.

Forced diuresis involves administration of diuretic agents and isotonic saline to increase glomerular filtration rate and urine flow. Fluid overload, pulmonary edema, and electrolyte disturbances can complicate therapy in compromised patients, especially in the presence of cardiac, renal, or pulmonary dysfunction.

Fluid overload, pulmonary edema, and electrolyte disturbances can complicate therapy in compromised patients, especially in the presence of cardiac, renal, or pulmonary dysfunction. Although it is important to maintain good urine flow during treatment of toxicities, increasing glomerular filtration through forced diuresis is not encouraged in most intoxications. However, this approach has been used with nephrotoxic drugs because of the dilutional effect on nephrotoxic agents in the renal tubules.

Although it is important to maintain good urine flow during treatment of toxicities, increasing glomerular filtration through forced diuresis is not encouraged in most intoxications. However, this approach has been used with nephrotoxic drugs because of the dilutional effect on nephrotoxic agents in the renal tubules.Urine Alkalinization

As discussed in the pharmacokinetics chapter, many substances are reabsorbed from the renal tubules into the bloodstream, limiting the extent of their urinary excretion.

As discussed in the pharmacokinetics chapter, many substances are reabsorbed from the renal tubules into the bloodstream, limiting the extent of their urinary excretion. The principles of ion trapping (see pharmacokinetics chapter) can be used to increase urinary excretion.

The principles of ion trapping (see pharmacokinetics chapter) can be used to increase urinary excretion. Urine is generally acidic, and alkalinizing the urine (generally to above pH 7.5) increases ionization of acidic substances and thereby prevents their tubular reabsorption.

Urine is generally acidic, and alkalinizing the urine (generally to above pH 7.5) increases ionization of acidic substances and thereby prevents their tubular reabsorption. Because pH is a logarithmic scale, each unit change in pH results in an approximately tenfold change in ionization and presumably excretion.

Because pH is a logarithmic scale, each unit change in pH results in an approximately tenfold change in ionization and presumably excretion. Bicarbonate solution is infused intravenously while urine pH is monitored, with a goal of reaching a urine pH of 7.5 to 8.

Bicarbonate solution is infused intravenously while urine pH is monitored, with a goal of reaching a urine pH of 7.5 to 8.Gastrointestinal Excretion

Interruption of Enterohepatic Cycling

Activated charcoal, particularly MDAC, may increase toxicant elimination in part by interrupting enterohepatic cycling.

Activated charcoal, particularly MDAC, may increase toxicant elimination in part by interrupting enterohepatic cycling.Enterocapillary Exsorption (Gastrointestinal Dialysis)

The very low concentration of free toxicant in the gut lumen means that free toxicant concentrations in the plasma are higher than those in the gut. This blood-to-gut concentration gradient favors diffusion of toxicant from the blood into the gut lumen where the toxicant binds to the charcoal. The charcoal-bound toxicant is eventually excreted in the feces (Figure 7-5). As this cycle repeats itself, the blood is cleared of toxicant.

The very low concentration of free toxicant in the gut lumen means that free toxicant concentrations in the plasma are higher than those in the gut. This blood-to-gut concentration gradient favors diffusion of toxicant from the blood into the gut lumen where the toxicant binds to the charcoal. The charcoal-bound toxicant is eventually excreted in the feces (Figure 7-5). As this cycle repeats itself, the blood is cleared of toxicant.Pharmacologic Treatment of Specific Intoxications

Analgesics

Intoxication with analgesics represents the most common form of toxicity requiring hospitalization.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen poisoning causes hepatotoxicity and is one of the more common lethal poisonings in industrialized countries.

Acetaminophen poisoning causes hepatotoxicity and is one of the more common lethal poisonings in industrialized countries. Acetaminophen is present in many combination analgesic preparations. Although intentional overdose is a cause of acetaminophen toxicity, intoxication can also be inadvertent owing to use of multiple acetaminophen-containing analgesics (e.g., combining over-the-counter acetaminophen with prescription opioid-acetaminophen analgesics)

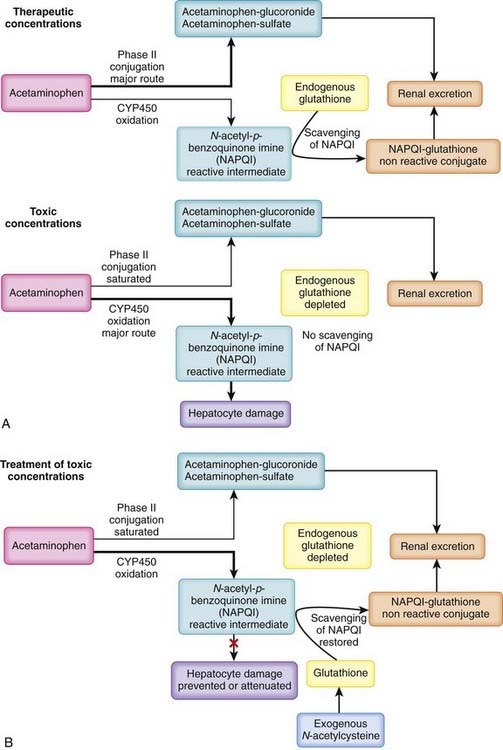

Acetaminophen is present in many combination analgesic preparations. Although intentional overdose is a cause of acetaminophen toxicity, intoxication can also be inadvertent owing to use of multiple acetaminophen-containing analgesics (e.g., combining over-the-counter acetaminophen with prescription opioid-acetaminophen analgesics) Acetaminophen is not toxic per se but is metabolized to a reactive intermediate that is toxic (Figure 7-6, A).

Acetaminophen is not toxic per se but is metabolized to a reactive intermediate that is toxic (Figure 7-6, A).

At therapeutic concentrations:

At therapeutic concentrations:

Treatment of acetaminophen poisoning

Treatment of acetaminophen poisoning

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). A primary treatment strategy for acetaminophen toxicity is replenishment of cellular glutathione via the administration of NAC, a precursor of glutathione (see Figure 7-6, B).

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). A primary treatment strategy for acetaminophen toxicity is replenishment of cellular glutathione via the administration of NAC, a precursor of glutathione (see Figure 7-6, B).

Through these mechanisms, NAC scavenges NAPQI, prevents its interaction with cellular constituents, and prevents hepatic cell death.

Through these mechanisms, NAC scavenges NAPQI, prevents its interaction with cellular constituents, and prevents hepatic cell death. NAC is most effective at preventing acetaminophen toxicity when given within 8 hours of ingestion of the overdose, because it acts by preventing the accumulation of a toxic metabolite. However, beneficial effects of NAC can be expected at later times (even >24 hours) if acetaminophen blood concentrations remain above the threshold for saturation of phase II conjugation.

NAC is most effective at preventing acetaminophen toxicity when given within 8 hours of ingestion of the overdose, because it acts by preventing the accumulation of a toxic metabolite. However, beneficial effects of NAC can be expected at later times (even >24 hours) if acetaminophen blood concentrations remain above the threshold for saturation of phase II conjugation.Salicylates

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is the most recognizable and one of the oldest and most widely used agents for antiinflammatory, antipyretic, antiplatelet, and analgesic purposes.

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is the most recognizable and one of the oldest and most widely used agents for antiinflammatory, antipyretic, antiplatelet, and analgesic purposes. Significant quantities of salicylates are also present in a wide variety of compounds including rubs to treat minor aches and pains (e.g., methyl salicylate rubs) and keratolytics used to treat warts (e.g., salicylic acid) and acne. The antidiarrheal agent Pepto-Bismol contains subsalicylates. Some of these preparations have a very high salicylate content, such that even relatively small quantities can produce severe toxicity. Oil of wintergreen (methyl salicylate) contains approximately 7000 mg of salicylate per teaspoon, the equivalent of approximately 22 aspirin tablets.

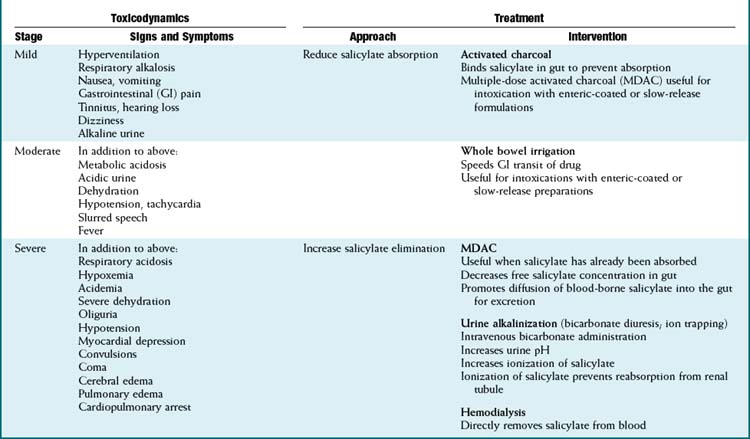

Significant quantities of salicylates are also present in a wide variety of compounds including rubs to treat minor aches and pains (e.g., methyl salicylate rubs) and keratolytics used to treat warts (e.g., salicylic acid) and acne. The antidiarrheal agent Pepto-Bismol contains subsalicylates. Some of these preparations have a very high salicylate content, such that even relatively small quantities can produce severe toxicity. Oil of wintergreen (methyl salicylate) contains approximately 7000 mg of salicylate per teaspoon, the equivalent of approximately 22 aspirin tablets. Salicylate toxicity (Table 7-1)

Salicylate toxicity (Table 7-1)

The widespread availability of salicylate preparations has resulted in a relatively high incidence of salicylate poisoning. Acute ingestion of toxic quantities may occur in accidental overdoses or in suicide attempts. Toxicity may also occur chronically because at high therapeutic doses (e.g., antiinflammatory doses) elimination mechanisms are nearly or completely saturated and salicylates exhibit zero-order kinetics. Some of the early-phase signs and symptoms of salicylate poisoning (see later) may be apparent at high therapeutic doses.

The widespread availability of salicylate preparations has resulted in a relatively high incidence of salicylate poisoning. Acute ingestion of toxic quantities may occur in accidental overdoses or in suicide attempts. Toxicity may also occur chronically because at high therapeutic doses (e.g., antiinflammatory doses) elimination mechanisms are nearly or completely saturated and salicylates exhibit zero-order kinetics. Some of the early-phase signs and symptoms of salicylate poisoning (see later) may be apparent at high therapeutic doses. Salicylic acid is the primary toxicant, and toxicity is related to the amount of free salicylic acid present in the body.

Salicylic acid is the primary toxicant, and toxicity is related to the amount of free salicylic acid present in the body. Salicylic acid is eliminated primarily by phase II conjugation with subsequent renal excretion of the conjugates. At low concentrations, salicylic acid is cleared by first-order kinetics with a half-life of approximately 2 to 5 hours. However, as mentioned previously, these conjugation mechanisms are near saturation at high therapeutic concentrations. Once the phase II conjugation mechanisms become saturated, elimination follows zero-order kinetics and the half-life may be extended to as much as 18 to 36 hours. In addition, renal excretion of free salicylic acid becomes the primary mechanism for clearance once phase II mechanisms are saturated.

Salicylic acid is eliminated primarily by phase II conjugation with subsequent renal excretion of the conjugates. At low concentrations, salicylic acid is cleared by first-order kinetics with a half-life of approximately 2 to 5 hours. However, as mentioned previously, these conjugation mechanisms are near saturation at high therapeutic concentrations. Once the phase II conjugation mechanisms become saturated, elimination follows zero-order kinetics and the half-life may be extended to as much as 18 to 36 hours. In addition, renal excretion of free salicylic acid becomes the primary mechanism for clearance once phase II mechanisms are saturated. Salicylate toxicity manifests as progressive metabolic, neural, cardiovascular, and renal dysfunction.

Salicylate toxicity manifests as progressive metabolic, neural, cardiovascular, and renal dysfunction. Accumulation of free salicylic acid has several toxic effects, which include:

Accumulation of free salicylic acid has several toxic effects, which include:

Salicylate poisoning is progressive. The early (mild) phase involves:

Salicylate poisoning is progressive. The early (mild) phase involves:

The moderate phase of salicylate poisoning involves:

The moderate phase of salicylate poisoning involves:

The severe (late) phase of salicylate poisoning involves:

The severe (late) phase of salicylate poisoning involves:

Progression of CNS toxicity, wherein hyperventilation may switch to hypoventilation with consequent respiratory acidosis and hypoxemia

Progression of CNS toxicity, wherein hyperventilation may switch to hypoventilation with consequent respiratory acidosis and hypoxemia Treatment of salicylate poisoning

Treatment of salicylate poisoning

Salicylic acid is a weak acid with a pKa of approximately 3.5 and therefore will be ionized at alkaline pH.

Salicylic acid is a weak acid with a pKa of approximately 3.5 and therefore will be ionized at alkaline pH. It maintains normal or slightly alkalemic pH to reduce the distribution of salicylic acid to the intracellular compartment.

It maintains normal or slightly alkalemic pH to reduce the distribution of salicylic acid to the intracellular compartment. It replenishes bicarbonate lost through renal excretion as the kidney attempts to compensate for respiratory alkalosis caused by hyperventilation.

It replenishes bicarbonate lost through renal excretion as the kidney attempts to compensate for respiratory alkalosis caused by hyperventilation. Alkalinization of urine converts salicylic acid to its ionized form and prevents its reabsorption from renal tubules (ion trapping).

Alkalinization of urine converts salicylic acid to its ionized form and prevents its reabsorption from renal tubules (ion trapping).Opioid Analgesics

Treatment of opioid toxicity

Treatment of opioid toxicity

Opioid receptor antagonists

Opioid receptor antagonists

Ethylene Glycol, Methanol

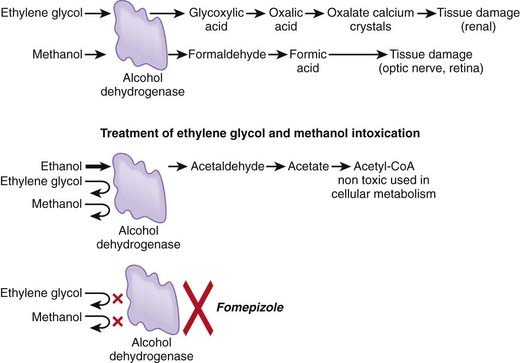

Although relatively infrequent, intoxication with alcohols such as ethylene glycol and methanol can result in a high rate of mortality if not treated appropriately.

Although relatively infrequent, intoxication with alcohols such as ethylene glycol and methanol can result in a high rate of mortality if not treated appropriately. Ethylene glycol is present in automobile coolants, which may be ingested in suicide attempts or by children because of its sweet taste.

Ethylene glycol is present in automobile coolants, which may be ingested in suicide attempts or by children because of its sweet taste. Neither ethylene glycol nor methanol is particularly toxic per se, but these compounds are biotransformed into toxic metabolites (Figure 7-7).

Neither ethylene glycol nor methanol is particularly toxic per se, but these compounds are biotransformed into toxic metabolites (Figure 7-7). Ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol

Oxidation of ethylene glycol and methanol by alcohol dehydrogenase is the initial step initiating these metabolic cascades.

Oxidation of ethylene glycol and methanol by alcohol dehydrogenase is the initial step initiating these metabolic cascades.Treatment of Ethylene Glycol or Methanol Poisoning

Inhibition of metabolite formation

Inhibition of metabolite formation

Ethanol (ethyl alcohol)

Ethanol (ethyl alcohol)

Fomepizole

Fomepizole

Cardiac Glycosides

Also found in a wide range of plants (e.g., foxglove, milkweed) and herbal remedies (e.g., oleander).

Also found in a wide range of plants (e.g., foxglove, milkweed) and herbal remedies (e.g., oleander). Have a low therapeutic index. Poisonings may result from small changes in absorption or elimination of therapeutic doses or from accidental ingestion of pills or cardiac glycoside–containing plants.

Have a low therapeutic index. Poisonings may result from small changes in absorption or elimination of therapeutic doses or from accidental ingestion of pills or cardiac glycoside–containing plants. Cardiac glycoside toxicity

Cardiac glycoside toxicity

Treatment of cardiac glycoside toxicity

Treatment of cardiac glycoside toxicity

Manipulation of distribution or enhancement of elimination

Manipulation of distribution or enhancement of elimination

Pesticides

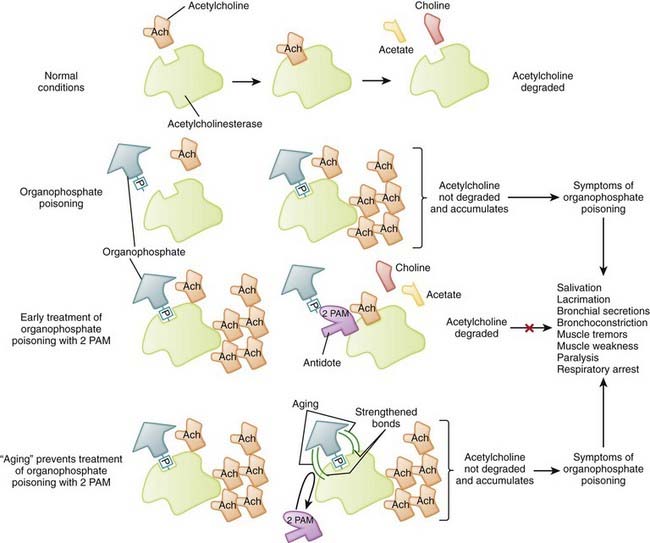

Many pesticides act as inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase, the endogenous enzyme responsible for the degradation of acetylcholine.

Many pesticides act as inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase, the endogenous enzyme responsible for the degradation of acetylcholine. Organophosphates (e.g., malathion, parathion) are time-dependent irreversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. Organophosphates form a broad group of agents used extensively as insecticides throughout the world and as nerve gas agents.

Organophosphates (e.g., malathion, parathion) are time-dependent irreversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. Organophosphates form a broad group of agents used extensively as insecticides throughout the world and as nerve gas agents. Carbamates (e.g., carbaryl, carbofuran) are reversible inhibitors of acetyl cholinesterase used primarily as insecticides.

Carbamates (e.g., carbaryl, carbofuran) are reversible inhibitors of acetyl cholinesterase used primarily as insecticides. Toxicity of organophosphate and carbamate pesticides

Toxicity of organophosphate and carbamate pesticides

The primary mechanism of action of these agents is inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme responsible for degrading acetylcholine into choline and acetate, with the resultant accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh) in neuroeffector junctions. Overstimulation of cholinergic receptors is responsible for the signs and symptoms and toxicity of organophosphate and carbamate poisoning (Figure 7-8).

The primary mechanism of action of these agents is inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme responsible for degrading acetylcholine into choline and acetate, with the resultant accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh) in neuroeffector junctions. Overstimulation of cholinergic receptors is responsible for the signs and symptoms and toxicity of organophosphate and carbamate poisoning (Figure 7-8). Excess acetylcholine results in overstimulation of cholinergic muscarinic and nicotinic receptors in various tissues.

Excess acetylcholine results in overstimulation of cholinergic muscarinic and nicotinic receptors in various tissues.

Treatment of organophosphate and carbamate pesticide toxicity

Treatment of organophosphate and carbamate pesticide toxicity

2-PAM disrupts a phophoryl-ester bond (-P- in Figure 7-8) between the organophosphate molecule and acetylcholinesterase to release the organophosphate from enzyme.

2-PAM disrupts a phophoryl-ester bond (-P- in Figure 7-8) between the organophosphate molecule and acetylcholinesterase to release the organophosphate from enzyme. Organophosphate inhibitors undergo a time-dependent process (called aging) that strengthens the bonds between the inhibitor and enzyme. This results in irreversibility of the inhibition. Once aging has occurred, 2-PAM and other oximes are unable to break the bonds between inhibitor and enzyme. Consequently, after aging, oximes are not able to reactivate acetylcholinesterase.

Organophosphate inhibitors undergo a time-dependent process (called aging) that strengthens the bonds between the inhibitor and enzyme. This results in irreversibility of the inhibition. Once aging has occurred, 2-PAM and other oximes are unable to break the bonds between inhibitor and enzyme. Consequently, after aging, oximes are not able to reactivate acetylcholinesterase.Calcium Channel Blockers and β-Blockers

Calcium channel blockers are prescribed for a number of cardiovascular conditions (e.g., angina, hypertension, tachycardia).

Calcium channel blockers are prescribed for a number of cardiovascular conditions (e.g., angina, hypertension, tachycardia). β-Blockers are also used extensively for cardiovascular applications (hypertension, heart failure, angina).

β-Blockers are also used extensively for cardiovascular applications (hypertension, heart failure, angina). The widespread use of these drugs has led to an increase in toxicity from overdose, particularly in children, who may become symptomatic with ingestion of a single tablet.

The widespread use of these drugs has led to an increase in toxicity from overdose, particularly in children, who may become symptomatic with ingestion of a single tablet. Toxicity of calcium channel blockers and β-blockers

Toxicity of calcium channel blockers and β-blockers

Calcium channel blockers decrease calcium entry into:

Calcium channel blockers decrease calcium entry into:

Treatment of calcium channel blocker and β-blocker toxicity

Treatment of calcium channel blocker and β-blocker toxicity

Physiologic treatments

Physiologic treatments

American Association of Poison Control Centers. www.aapcc.org

Canadian Association of Poison Control Centres. www.capcc.ca/resources/resources.php

Glossary of toxicologic terms Glossary of toxicologic terms. http://sis.nlm.nih.gov/enviro/iupacglossary/frontmatter.html

National Library of Medicine (U.S.). www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov

National Toxicology Program (U.S.). http://cerhr.niehs.nih.gov/reports/index.html

World Health Organization. www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/directory/en/index.html