CHAPTER 26 Systemic mastocytosis

Introduction

SM diagnosis is based on morphology and cannot be established on the basis of clinical findings alone. Therefore, the pathologist should be familiar with the diagnostic criteria defined for mastocytosis and also to recognize its mimickers.1,2 Important mimickers of mastocytosis are reactive states of mast cell hyperplasia and a few rare neoplastic hematological disorders such as tryptase-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelomastocytic leukemia. Diagnostic criteria of SM are given in Box 26.1.

The major and two of four minor diagnostic criteria are morphology-based. Diagnosis of SM can be established if the major and one minor criterion are fulfilled. In cases lacking the major criterion, SM diagnosis can be established if at least three minor criteria are found.1,2 Most cases of SM can be easily diagnosed when focal compact infiltrates with a significant proportion of spindle-shaped mast cells are present. SM exhibiting exclusively round mast cells can be diagnosed after demonstration of an atypical immunophenotype with expression of CD25, which is not present in normal mast cells.3 If compact mast cell infiltrates are missing, diffusely scattered spindle-shaped mast cells with CD25 expression alone are not enough to establish a diagnosis of mastocytosis. In these patients, demonstration of the KITD816V mutation and/or chronically elevated serum tryptase enables diagnosis of mastocytosis since three of four minor criteria are fulfilled.4,5,6

BM is the main tissue where diagnosis of SM can be established. However, demonstration of compact mast cell infiltrates in extramedullary tissues like lymph node, spleen, liver and/or mucosa should also be regarded as strong indication for SM.7,8,9 Rarely, the diagnosis of mastocytosis is first established in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and BM involvement is confirmed later. It is rather unlikely that pure GI form exists. In all patients with GI involvement, the meticulous investigation of the BM should be performed using immunohistochemistry and molecular biology. In a considerable proportion of SM patients, the degree of tissue infiltration is very low. The WHO 2008 classification of mastocytosis is given in Box 26.2.2 The approach to the diagnosis of mastocytosis is complex and considering its relatively low incidence, the diagnosis is usually more difficult than in most other hematological malignancies. The different forms of SM can only be recognized when the pathologist is aware of important clinical findings, especially the so-called ‘B-findings’, including organomegaly, and ‘C-findings’, indicating organ dysfunction due to widespread mast cell infiltration (Box 26.2).

Box 26.2 Classification of mastocytosis (WHO 2008)2

‘B’ findings

Molecular genetics aspects

Mast cells of most patients with SM carry the activating point mutation KITD816V of the c-kit gene.10 However, the frequency of KITD816V varies between subtypes of the disease. It has been found in almost 100% of patients with SM-AHNMD but only in about 50–60% of patients with aggressive SM and mast cell leukemia (MCL). Indolent SM assumes an intermediate position. Other than D816V point mutations of c-kit (e.g. D816Y or D816H) do occur but are rarely detected in SM.11 A considerable number of patients with SM-AHNMD were found to carry KITD816V not only in the SM but also in the AHNMD compartment of the disease. The frequency of KITD816V depends on the subtype of hematological disorder. SM-associated chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) exhibits KITD816V in almost all cases. The mutation is found both in the SM and the AHNMD compartment of the disease, which underlines a close clonal relationship between SM and CMML in the setting of SM-AHNMD. In SM associated with a myeloproliferative neoplasm with eosinophilia (MPNEo), KITD816V is usually not found in the MPNEo. Very surprisingly, it is also lacking in the SM compartment, although compact infiltrates of CD25+ mast cells are present in a few cases thus enabling the morphological diagnosis of SM.12 In other types of SM-AHNMD (SM with myelodysplastic syndrome (SM-MDS), SM-AML, and SM with myeloproliferative neoplasms (SM-MPN)), the incidence of KITD816V in the associated disorder varies between 20% and 60% of patients. Interestingly, it has been shown that in cases of SM-MPN (e.g. primary myelofibrosis), both mast cells and cells of neutrophilic lineage could carry both activating point mutations KITD816V and JAK-2V617F, further indicating the close relationship between SM and ‘AHNMD’.13

Important messages

Routine work-up of cases with suspected systemic mastocytosis

Bone marrow trephine biopsy

The adequate BMTB specimen should be above 2 cm in length. Antibodies against CD25, CD117 and tryptase should be applied.20,21,22,23 In cases of suspected SM-AHNMD further immunohistochemical stainings with appropriate antibodies depending on the subtype of the hematological disorder should also be performed. The tissue can also be used for demonstration of the KITD816V mutation, which is best detected if the biopsy is fixed in 5% buffered neutral formalin and mildly decalcified in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) overnight. Peripheral blood (PB) and BM smears are crucial for differential diagnosis between aggressive SM (ASM) and aleukemic MCL or aleukemic from leukemic MCL, respectively.

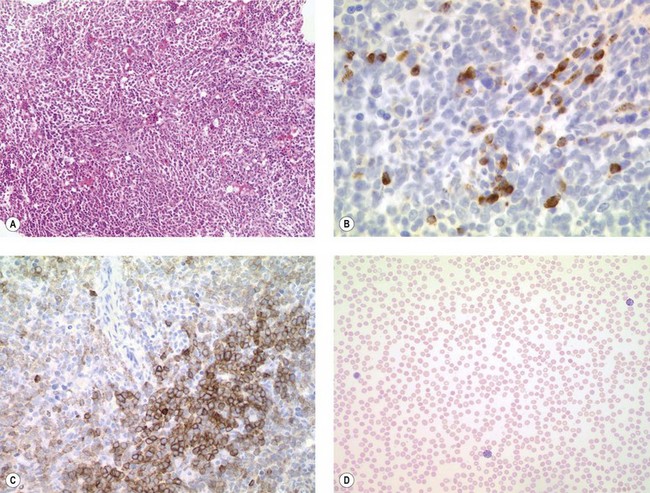

General morphological aspects of SM

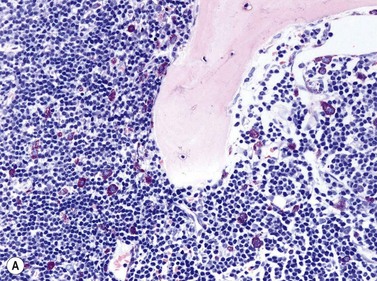

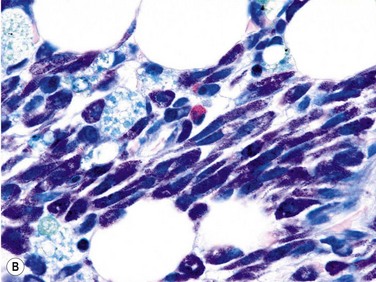

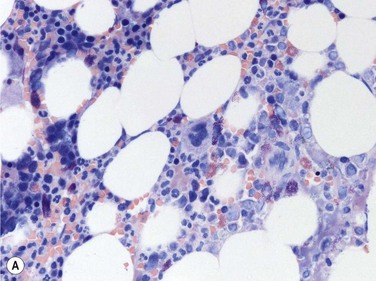

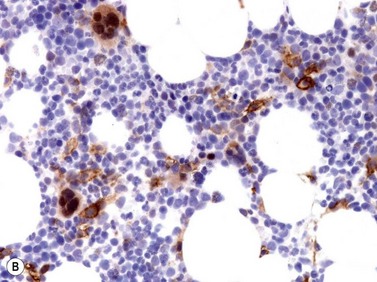

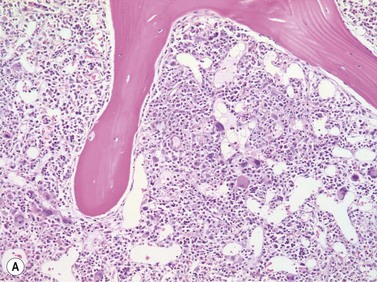

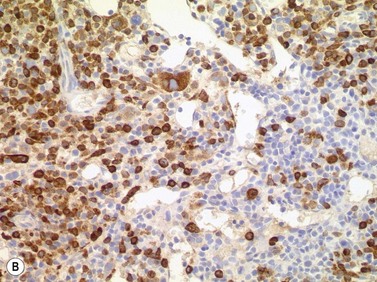

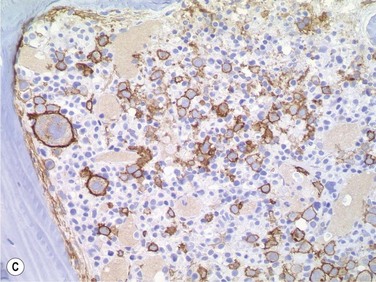

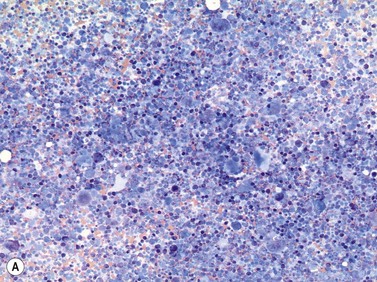

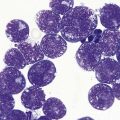

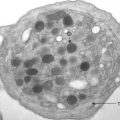

Size and cytological composition of compact (diagnostic) mast cell infiltrates varies greatly. Mast cells are not always dominant and may be obscured by follicle-like aggregates of lymphocytes. The lymphocyte-dominated infiltrates may mimic lymphocytic lymphoma, which is almost always accompanied by an increase in reactive (round, strongly metachromatic) mast cells posing considerable differential diagnostic problems in some cases (Fig. 26.1A).24 In contrast to mast cell hyperplasia, most SM cases exhibit at least one compact infiltrate consisting of slightly atypical often spindle-shaped and hypogranulated mast cells (Fig. 26.1B). Increased numbers of eosinophils are also usually found, admixed to lymphocytes and mast cells. Eosinophilic microabscesses are rarely detected. Focal increase in eosinophils within these compact infiltrates is only rarely accompanied by a significant eosinophilia in the hematopoietic islands. Stromal reaction shows almost always a dense network of reticulin fibers with the possibility to transform into collagen fibrosis. In some cases, the infiltrates may show striking variation in morphological appearance within the same biopsy specimen, ranging from large foci of collagen fibrosis with loosely scattered spindle-shaped mast cells to smaller lymphoid follicle-like structures with adjacent compact micronodules of round hypogranulated mast cells containing only slightly increased amounts of reticulin fibers. In larger infiltrates, there is also a significant angio-neogenesis with increase in small blood vessels. In most cases, mast cell infiltrates show a predominant peritrabecular localization leading to focal sclerosis of the adjacent bone. Cytomorphology of mast cells also varies greatly, ranging from cases with a predominance of spindle-shaped, markedly hypogranulated cells to cases containing exclusively round hypergranulated, mature-appearing mast cells, posing here the differential diagnosis of well-differentiated SM. The numbers of loosely scattered atypical mast cells are usually hard to estimate in Giemsa-stained sections (Fig. 26.2A), but they can be easily seen in CD25 immunostaining (Fig. 26.2B). It is crucial to apply all three antibodies: CD25, CD117 (KIT) and tryptase in all cases of suspected SM, in order to identify spindle-shaped, hypogranulated, fibroblast-like cells as mast cells, to recognize an aberrant immunophenotype with CD25-expression, and to be able to estimate the degree of the diffuse involvement of the BM aside from the compact mast cell infiltrates However, co-expression of tryptase and CD117 defines both normal/reactive and clonal-neoplastic mast cells of all stages of maturation and all degrees of atypia. Tryptase-expressing cells without CD117 are not mast cells but can be regarded as (neoplastic) basophils or myeloblasts. Such tryptase-positive CD117-negative cells are small to medium-sized and exclusively round. CD117-positive tryptase-negative cells are not mast cells but most likely BM progenitor cells of granulopoietic and/or erythropoietic lineage. Mast cells of high-grade subtypes like aggressive or leukemic SM may express some other aberrant markers like CD30 and/or CD33 that easily may lead to an erroneous diagnosis when the relevant mast cell-associated antibodies are not applied. In most patients with ISM or isolated SM of the bone marrow, the hematopoiesis is completely normal. Some signs of so-called inflammatory reaction like plasmacytosis, ceroid histiocytosis and eosinophilia are often present. In cases with aggressive SM or MCL, the hematopoiesis is often markedly reduced or almost completely effaced. It may be very difficult to assess or exclude the diagnosis of an ‘AHNMD’ (i.e., ASM-AHNMD or MCL-AHMD) in such cases. It is therefore strongly recommended to analyse BM and PB smears carefully in order not to miss an associated hematological malignancy. There are cases of ASM with subtotal involvement of the BM, where PB investigation revealed a diagnosis of CMML thus leading to the ultimate diagnosis of ASM-CMML. It is likely that ‘pure’ aggressive SM is a very uncommon disorder and ASM-AHNMD is the common setting (own unpublished observations).

TROCI-bm (= tryptase positive round cell infiltrate of the bone marrow)25 is a recently described immunohistochemical phenomenon, defined as focal or diffuse but always compact tissue infiltrates consisting exclusively of tryptase-expressing round cells in the BM. TROCI-bm is only seen in some rare hematological neoplasms. Diffuse TROCI-bm is encountered in myelomastocytic leukemia, MCL or chronic basophilic leukemia. Focal TROCI-bm is seen in common type systemic mastocytosis, well-differentiated mastocytosis or chronic basophilic leukemia, as well as in accelerated phase of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Bone marrow smears

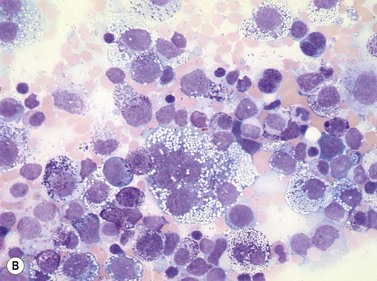

In most cases, evaluation of BM smears is not sufficient for diagnosis of SM. However, cytomorphologic evaluation and differential count of BM smears is inevitable for differentiation of ASM from MCL.26 If numbers of mast cells exceed 20% of nucleated BM cells, diagnosis of MCL is confirmed (Fig. 26.3A–C). Conversely, mast cell numbers are lower than 0.1% of nucleated cells in BM smears from patients with indolent SM and therefore it is challenging to search for mast cells and estimate their frequency. In patients with ISM, cytomorphological evaluation usually confirms mild atypia of mast cells. The mast cells here are often spindle-shaped and contain plump cigar-like nuclei together with a hypogranulated cytoplasm. The presence of such mast cells in patients with cutaneous mastocytosis (usually urticaria pigmentosa) must prompt suspicion of ISM and can be regarded as an indication for histological investigation of a BMTB specimen.

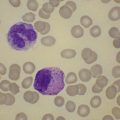

Blood smears

Apart from rare patients with MCL, blood findings are not indicative of SM.15 MCL shows a significant increase in circulating mast cells, which exhibit varying degrees of atypia. Some cases show mature round mast cells with abundant metachromatic granules leading to a correct diagnosis at first glance. Other MCL contain highly atypical hypogranulated circulating mast cells with pale large cytoplasm mimicking monocytoid or hairy cells. In most patients with indolent SM, PB exhibits no significant changes but some patients may show mild eosinophilia. Major alterations of blood cells are detected in most cases of SM-AHNMD, in particular those with associated myeloid leukemia. It has to be emphasized that sometimes a diagnosis of SM-AHNMD can only be established when a BMTB specimen and blood smears are investigated together because SM shows diffuse-compact BM infiltration thus obscuring the AHNMD. In every patient with aggressive SM or MCL, blood smears have to be analyzed in order not to overlook the AHNMD.

Morphology of the various defined subtypes of SM in the bone marrow

Main subtypes of SM

Provisional entities

Differential diagnosis

Mastocytosis has to be strictly separated both from reactive states of mast cell hyperplasia and from neoplastic diseases exhibiting signs of mast cell differentiation. The so-called ‘monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome’ (MMAS) is only roughly defined until now with respect to morphology. MMAS can be applied to cases showing disseminated scattered mast cells carrying the KITD816V mutation but not fulfilling other criteria for mastocytosis, in particular missing compact infiltrates. MMAS is somewhat analogous to a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS, see Chapter 30) and at present is a preliminary description of a still ill-defined status.

It is important to be aware that even the different forms of mastocytosis include a considerable spectrum of differential diagnoses. These are summarized in Box 26.3.

1 Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603-625.

2 Horny HP, Metcalfe DD, Bennett J, et al. Mastocytosis. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. p. 54–63

3 Sotlar K, Horny HP, Simonitsch I, et al. CD25 indicates the neoplastic phenotype of mast cells: a novel immunohistochemical marker for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis (SM) in routinely processed bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1319-1325.

4 Sotlar K, Marafioti T, Griesser H, et al. Detection of c-kit mutation Asp 816 to Val in microdissected bone marrow infiltrates in a case of systemic mastocytosis associated with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:188-193.

5 Feger F, Ribadeau DA, Leriche L, et al. Kit and c-kit mutations in mastocytosis: a short overview with special reference to novel molecular and diagnostic concepts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:110-114.

6 Sperr WR, Jordan JH, Fiegl M, et al. Serum tryptase levels in patients with mastocytosis: correlation with mast cell burden and implication for defining the category of disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;128:136-141.

7 Horny HP, Valent P. Diagnosis of mastocytosis: general histopathological aspects, morphological criteria, and immunohistochemical findings. Leuk Res. 2001;25:543-551.

8 Horny HP, Valent P. Histopathological and immunohistochemical aspects of mastocytosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:115-117.

9 Horny HP, Ruck MT, Kaiserling E. Spleen findings in generalized mastocytosis. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1992;70:459-468.

10 Furitsu T, Tsujimura T, Tono T, et al. Identification of mutations in the coding sequence of the proto-oncogene c-kit in a human mast cell leukemia cell line causing ligand-independent activation of c-kit product. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1736-1744.

11 Sotlar K, Saeger W, Stellmacher F, et al. ‘Occult’ mastocytosis with activating c-kit point mutation evolving into systemic mastocytosis associated with plasma cell myeloma and secondary amyloidosis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:875-878.

12 Maric I, Robyn J, Metcalfe DD, et al. KIT D816V-associated systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia and FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated chronic eosinophilic leukemia are distinct entities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:680-687.

13 Sotlar K, Bache A, Stellmacher F, et al. Systemic mastocytosis associated with chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis: a distinct subtype of systemic mastocytosis associated with a [corrected] clonal hematological non-mast [corrected] cell lineage disorder carrying the activating point mutations KITD816V and JAK2V617F. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:58-66.

14 Escribano L, Orfao A, Diaz-Agustin B, et al. Indolent systemic mast cell disease in adults: immunophenotypic characterization of bone marrow mast cells and its diagnostic implications. Blood. 1998;91:2731-2736.

15 Horny HP, Ruck M, Wehrmann M, Kaiserling E. Blood findings in generalized mastocytosis: evidence of frequent simultaneous occurrence of myeloproliferative disorders. Br J Haematol. 1990;76:186-193.

16 Sperr WR, Horny HP, Lechner K, Valent P. Clinical and biologic diversity of leukemias occurring in patients with mastocytosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:473-486.

17 Horny HP, Sotlar K, Sperr WR, Valent P. Systemic mastocytosis with associated clonal haematological non-mast cell lineage diseases: a histopathological challenge. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:604-608.

18 Bernd HW, Sotlar K, Lorenzen J, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia with t(8;21) associated with ‘occult’ mastocytosis. Report of an unusual case and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:324-328.

19 Caplan RM. The natural course of urticaria pigmentosa. Analysis and follow-up of 112 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:146-157.

20 Li CY. Diagnosis of mastocytosis: value of cytochemistry and immunohistochemistry. Leuk Res. 2001;25:537-541.

21 Horny H.P, Sillaber C, Menke D, et al. Diagnostic value of immunostaining for tryptase in patients with mastocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1132-1140.

22 Li WV, Kapadia SB, Sonmez-Alpan E, Swerdlow SH. Immunohistochemical characterization of mast cell disease in paraffin sections using tryptase, CD68, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, and CD20 antibodies. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:982-988.

23 Jordan JH, Walchshofer S, Jurecka W, et al. Immunohistochemical properties of bone marrow mast cells in systemic mastocytosis: evidence for expression of CD2, CD117/Kit, and bcl-x(L). Hum Pathol. 2001;32:545-552.

24 Horny HP, Sotlar K, Stellmacher F, et al. An unusual case of systemic mastocytosis associated with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (SM-CLL). J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:264-268.

25 Horny HP, Sotlar K, Stellmacher F, et al. The tryptase positive compact round cell infiltrate of the bone marrow (TROCI-BM): a novel histopathological finding requiring the application of lineage specific markers. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:298-302.

26 Sperr WR, Escribano L, Jordan JH, et al. Morphologic properties of neoplastic mast cells: delineation of stages of maturation and implication for cytological grading of mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:529-536.

27 Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis and related mast cell disorders: current treatment options and proposed response criteria. Leuk Res. 2003;27:635-641.

28 Travis WD, Li CY, Hoagland HC, et al. Mast cell leukemia: report of a case and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:957-966.

29 Horny HP, Parwaresch MR, Kaiserling E, et al. Mast cell sarcoma of the larynx. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:596-602.

30 Kojima M, Nakamura S, Itoh H, et al. Mast cell sarcoma with tissue eosinophilia arising in the ascending colon. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:739-743.

31 Guenther PP, Huebner A, Sobottka SB, et al. Temporary response of localized intracranial mast cell sarcoma to combination chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:134-138.

32 Hauswirth AW, Sperr WR, Ghannadan M, et al. A case of smouldering mastocytosis with peripheral blood eosinophilia and lymphadenopathy. Leuk Res. 2002;26:601-606.

33 Jordan JH, Fritsche-Polanz R, Sperr WR, et al. A case of ‘smouldering’ mastocytosis with high mast cell burden, monoclonal myeloid cells, and C-KIT mutation Asp-816-Val. Leuk Res. 2001;25:627-634.

34 Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, et al. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103:3222-3225.

35 Valent P, Samorapoompichit P, Sperr WR, et al. Myelomastocytic leukemia: myeloid neoplasm characterized by partial differentiation of mast cell-lineage cells. Hematol J. 2002;3:90-94.

36 Valent P, Sperr WR, Samorapoompichit P, et al. Myelomastocytic overlap syndromes: biology, criteria, and relationship to mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:595-602.

37 Sperr WR, Jordan JH, Baghestanian M, et al. Expression of mast cell tryptase by myeloblasts in a group of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:2200-2209.

38 Pardanani A, Ketterling RP, Brockman SR, et al. CHIC2 deletion, a surrogate for FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, occurs in systemic mastocytosis associated with eosinophilia and predicts response to imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003;102:3093-3096.