Surgical Interventions in Cancer

Soroush Rais-Bahrami, Peter A. Pinto and John E. Niederhuber

• The cancer surgeon is a key member of a multidisciplinary cancer care team.

• The surgeon is frequently the “entry point” for patients who are suspected of having cancer or are newly diagnosed with cancer.

• The surgeon must be prepared to communicate the results of initial biopsy pathology and staging to the patient, interpret these results in a meaningful way, and prepare the patient for the next steps in care.

• To be an effective member of the “team,” the surgeon must have knowledge of the biology and natural history of the cancer to be treated.

• The surgeon must be technically experienced in diagnostic procedures and operative interventions used in cancer management.

• The cancer surgeon must be experienced in the preoperative and postoperative care of surgical patients with complex cases.

• The surgical oncologist must have an appropriate knowledge base in medical and radiation oncology.

• Patients treated in a multimodality setting and in high-volume centers have improved outcomes.

• Training of the surgical oncologist must encompass the following:

Etiology and genetic predispositions of cancer

Etiology and genetic predispositions of cancer

Environmental risk factors and natural history of specific tumors

Environmental risk factors and natural history of specific tumors

Knowledge of genomic characterization, subclassification, and current options for highly targeted therapies

Knowledge of genomic characterization, subclassification, and current options for highly targeted therapies

Understanding of how to provide cost-effective treatment

Understanding of how to provide cost-effective treatment

Skills to develop, conduct, and manage clinical trials

Skills to develop, conduct, and manage clinical trials

Guidance in the management of advanced disease, including appropriate nutritional support

Guidance in the management of advanced disease, including appropriate nutritional support

Guidance in offering compassionate support

Guidance in offering compassionate support

Guidance in determining and evaluating outcomes

Guidance in determining and evaluating outcomes

Skills in managing complications of treatment and of disease progression

Skills in managing complications of treatment and of disease progression

• The surgical oncologist should be a participant in clinical trials, providing guidance in design and monitoring of quality control aspects of the surgical intervention component, as well as providing overall leadership and guidance in the study design and implementation.

• The surgical oncologist should be an educational resource in the health care environment and the community.

• The surgical oncologist plays an important role in prevention and screening.

Historical Perspective

In medicine, professional and public acceptance of a subspecialty has historically depended largely on accomplishment. The development of the surgical oncology subspecialty is no exception and has been intimately tied to the history of surgery. In fact, surgical treatment of cancer has been significantly responsible for the role of surgery in modern medicine. The earliest discussion of surgical treatment of tumors appears in the E.S. Papyrus (circa 1600 BC), but it is believed to be based on earlier writings dating back to 3000 BC.1

Advances made using anesthesia in the 1840s were led by John Crawford, a dentist who first discovered the loss of pain sensation with ether inhalation. John Collins Warren, who in 1838 published the earliest American work on tumors,2 was the first person to use ether in the removal of a tongue cancer.3 Sepsis, however, remained a major barrier to successful surgery until Joseph Lister (subsequently Baron Lister), an accomplished surgeon, introduced the concept of bactericidal therapy with carbolic acid in 1867.4 This concept was an outgrowth of Pasteur’s theory that bacteria caused infection. By using carbolic acid as an antiseptic agent in conjunction with heat sterilization of instruments, absorbable ligatures, and a drainage tube, Lister dramatically decreased the rate of postoperative fatalities.

Although the value of Lister’s contributions was not recognized by his senior colleagues, they were quickly adopted by William Stewart Halsted,5 the first professor of surgery at the new Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Halsted introduced to the United States the meticulous techniques of tissue handling during surgery and the antiseptic methods proposed by Lister. Halsted, who had a major interest in cancer, was strongly supported in his work by his close friend and colleague at Johns Hopkins, Sir William Osler. Osler was a student of abdominal malignancies, and the collaboration of these two great American physicians represents one of the earliest occurrences of the multidisciplinary approach to cancer treatment.

Today cancer surgery is involved in another period of transition as surgeons evaluate the pros and cons of minimally invasive surgical techniques in the diagnosis and resection of malignancies. Although minimally invasive surgery (MIS) can be traced to 1910 with the first endoscopic surgery in humans performed by Hans Christian Jacobaeus in Sweden,6 it was the advent of the computer chip television camera in the 1980s and the ability to view the operative field on a monitor that were foundational to rapidly advancing this new era of surgery during the next several decades.

In 1987, the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed by Phillipe Mouret in France.7 Since then, technical advances and instrumentation have propelled the field into a highly competitive surgical technology and expanded its application to encompass a list of procedures involving the chest, heart, abdomen, and pelvis. Today, MIS, including robotic surgery, is being applied to the primary resection of tumors of the colon, rectum, and prostate, female pelvic malignancies, gastric cancer, lung cancer, and esophageal cancer. The benefits of MIS are smaller incisions, decreased postoperative pain, decreased risk of infection, better cosmesis, shorter hospital stays, and significantly reduced convalescence. In today’s health care market, these advantages are popular among surgeons, patients, hospital administrators, and insurance companies. The questions have been whether resection for cure is compromised using an MIS approach and whether there is a risk of cancer cells seeding the port sites or other areas of resection.

The Surgical Oncologist

Surgical oncology, as a subspecialty of general surgery, has emerged to play an increasingly important role in the multidisciplinary treatment of cancer (Box 25-1). There are many reasons for this evolution of subspecialization within general surgery, but the most significant are: (1) the increasing complexity of multidisciplinary cancer care; (2) the opportunities for clinical and laboratory investigation of cancer’s complex biology; (3) the rapid increase in the number of medical and radiation specialty boarded oncologists, which threatens to diminish significantly the traditional role of the surgeon in coordinating the management of cancer care for patients (even those with early disease); and (4) the expectation of patients that surgeons have the latest information and understand the newest treatment options.8

Today the surgical oncologist is really a “cancer physician” who interacts with all other members of the cancer therapy team in a knowledgeable and confident manner (Box 25-2). This role requires a sound knowledge of cancer biology (including cancer prevention and the biology of metastasis), imaging technologies, chemical and biological therapy, and radiation therapy.

In a 1996 address before the American College of Surgeons, Murray Brennan of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York stated, “In defining what might be considered the role of the surgeon in cancer care, there are at least seven important areas that I believe need to have renewed emphasis.”9 Brennan used his experience with soft-tissue sarcoma to illustrate the importance of the following performance objectives for the cancer surgeon: (1) understands etiology and genetic predisposition; (2) understands prognostic factors and natural history; (3) performs cost-effective treatment; (4) develops clinical trials; (5) guides advanced disease management; (6) guides compassionate support; and (7) evaluates outcome. Brennan’s analysis of the cancer surgeon’s role as a member of today’s therapy team is an excellent real-life description of the responsibilities involved and the opportunities to provide real leadership in cancer care. These principles remain just as true today as when Dr. Brennan first spoke of them in 1996.

Training in Surgical Oncology

To address some of these issues, a conference was held at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1979. It was the consensus of this conference that training in surgical oncology should involve a 2-year period after completion of a general surgery residency.10 The committee charged a national organization, the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO), with developing training guidelines, reviewing criteria, and developing the approval process for identifying qualified training programs. Clearly, the hope of those involved was that expertise in surgical oncology could be increased in significant numbers and disseminated more broadly in the community practice arena, not just in academic centers. Further, it was hoped that the development of a number of university training programs would eventually lead to board certification.

Guidelines established by the SSO in 2001 called for 12 months of training in the surgical management of cancer cases, with a minimum number of procedures established for specific anatomic categories. In addition to surgical cases, trainees were required to gain experience in the other aspects of the multidisciplinary management of cancer. Nonsurgical experience was required in radiation oncology, surgical pathology, medical oncology, and supportive and rehabilitative care. Clinical research on human subjects was also part of the training experience, and participation in laboratory research was encouraged.11 By 2012, 14 surgical oncology training fellowship programs had been approved; additionally, 32 SSO-approved fellowship programs had been developed specific to the clinical training of the breast surgeon.

The effort to enhance training in surgical oncology, broaden available training opportunities, and provide a measure of qualification or certification of competence has been supported and nurtured by the SSO, which was founded in 1940 as the James Ewing Society.12 This organization has become the leading academic oncologic society for surgeons around the world. In assuming this leadership role, the SSO developed and disseminated optimal guidelines for the multidisciplinary care of patients with cancer, provided an important resource for continuing education through its annual meeting, initiated and supported a monthly journal (The Annals of Surgical Oncology, founded in 1994), and actively stimulated cancer research.13 The Society has willingly taken on the responsibility of evaluating and approving fellowship training programs. It embraced the recommended guidelines proposed by the 1979 NCI Committee and, in 1982, approved the first three training sites.14 In 1992, the World Federation of Surgical Oncology Societies was inaugurated and immediately worked to develop “standards of education, training, and practice” in surgical oncology.15,16 It is through the efforts of the SSO and the World Federation of Surgical Oncology Societies that excellent training opportunities now exist for a significant number of general surgery graduates. The work of the SSO and its leaders, beginning in 1982 with the approval of three fellowship training sites, recently achieved one of its most important goals when, in March 2011, the American Board of Surgery approved the new certificate in “Complex General Surgical Oncology” and on April 28, 2011, announced the formation of the Surgical Oncology Board.17

The Surgeon’s Role in Cancer Management

Prevention and Screening

The most effective weapons against cancer are prevention and early detection. Much of the debate about prevention has focused on the cost of delivering cancer prevention and screening services and the availability of enough adequately trained individuals to perform the appropriate screening test. Furthermore, the application of a screening test is a complex process (Box 25-3), and multiple layers of evaluation are needed to prove test efficacy. Clearly, a screening test must be applied at the right time and to the appropriate population to be effective. Moreover, the screening test itself is merely designed to identify a possible condition that needs further in-depth evaluation. For the surgeon, the effectiveness and cost of screening are directly related to the strategies used to address positive test results, including the rate of false positive results for a screening test. An example of the problem of false-positive results is seen in the use of computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer.

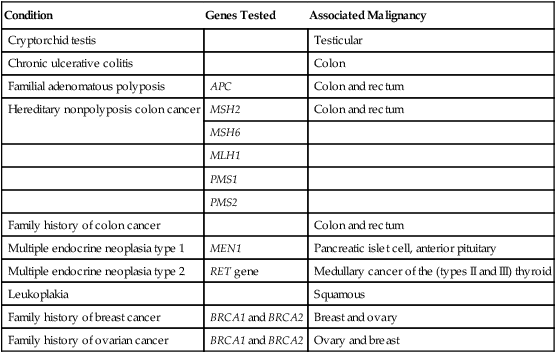

Certain conditions, which often are congenital or inherited genetic traits, are associated with the subsequent manifestation of cancer (see Chapters 12 and 13). Genetic testing has made it possible to accurately identify the carriers of mutations that increase the risk of the occurrence of certain cancers. For example, genetic tests available include those for the RET proto-oncogene present in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, the CDH1 mutation in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, the APC gene in colorectal cancer, and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast and ovarian cancers. In these instances, the surgeon has a responsibility to inform and educate the patient about the condition and to alert the family to the hereditary nature of the disorder and its possible occurrence in other family members. The surgeon should also discuss the availability of genetic testing for family members at risk. Table 25-1 outlines some common predisposing conditions, genes associated with these conditions, and their corresponding malignancies.

Table 25-1

Common Predisposing Conditions and Associated Malignancies

| Condition | Genes Tested | Associated Malignancy |

| Cryptorchid testis | Testicular | |

| Chronic ulcerative colitis | Colon | |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | APC | Colon and rectum |

| Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer | MSH2 | Colon and rectum |

| MSH6 | ||

| MLH1 | ||

| PMS1 | ||

| PMS2 | ||

| Family history of colon cancer | Colon and rectum | |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 | MEN1 | Pancreatic islet cell, anterior pituitary |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 | RET gene | Medullary cancer of the (types II and III) thyroid |

| Leukoplakia | Squamous | |

| Family history of breast cancer | BRCA1 and BRCA2 | Breast and ovary |

| Family history of ovarian cancer | BRCA1 and BRCA2 | Ovary and breast |

Diagnosis

Four techniques are currently in use for obtaining tissue for diagnosis:

1. Needle aspiration biopsy. This approach involves aspirating tissue fragments through a needle guided into an area in which disease is suspected. It can usually be performed using local anesthesia or, possibly, no anesthesia. Sampling can be guided by various imaging modalities, including CT and ultrasound. A study of the usefulness of CT-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of malignancy in small pulmonary lesions showed 82% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 88% accuracy.18 The disadvantage of aspiration biopsy is that it seldom yields a sufficient specimen for histologic diagnosis. As a result, a margin of error always exists in individual cell analysis, even with an exceptionally skilled cytopathologist. Cytology has the disadvantage of being unable to distinguish between invasive and noninvasive cancers, and thus a more detailed histologic diagnosis is usually necessary.

2. Needle (core) biopsy. This technique entails the retrieval of a small core of tissue, using a specially designed “core-cutting” needle. This specimen is usually sufficient for histologic diagnosis of most tumor types. Like aspiration biopsy, this technique is relatively cost-effective and can usually be performed with use of a local anesthetic.

3. Incisional biopsy. This technique involves surgical retrieval of a small segment of a larger tumor for diagnosis. The advantage of the procedure is that it yields enough histologic material to provide analysis of tumor markers. In addition, it is often possible to perform this procedure in an outpatient setting using local anesthesia. Incisional biopsies are particularly useful in the diagnosis of sarcomas, large tumors, and unresectable tumors and when the preferred treatment is nonsurgical. The disadvantages of incisional biopsy include possible sampling errors, the risk of trauma to the tumor, the possible risk of tumor spread, and the need for an excisional biopsy if no cancer is diagnosed. Precise technique is essential.

4. Excisional biopsy. This technique entails total removal of all suspicious tumor tissue, with little or no margin. The circumstances of the procedure dictate the use of local or general anesthesia. This procedure is the most definitive diagnostic tool of the four described. It provides adequate treatment for nonmalignant tumors and involves minimal trauma to the cancer. It is necessary to perform an excisional biopsy if the results of an incisional biopsy or core needle biopsy are inconclusive. One of the disadvantages of an excisional biopsy is that it is generally limited to small tumors (e.g., lymph nodes and parotid tumors). It also involves a deeper area of dissection, which necessitates wider margins.

The biopsy technique selected should be appropriate for the suspected lesion and should yield an adequate tissue sample for proper histologic and molecular diagnosis. Orientation of the specimen, if applicable, should be marked clearly and carefully by the surgeon to facilitate proper histologic interpretation. Proper handling of excised tissue is the surgeon’s responsibility, and the surgeon must be knowledgeable regarding procedures required to provide optimal high-quality specimens for tissue banking. Although such banking procedures thus far have been ad hoc, the NCI has in place a set of First-Generation Guidelines for the biorepositories that it supports (http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices/2011-NCIBestPractices.pdf).19 In addition to knowledge of such guidelines, it is also important for the surgeon to maintain a close relationship with the pathologist, who can provide guidance prior to staging procedures with regard to tissue requirements. Furthermore, if the patient has a pathological diagnosis from an outside source, it is always necessary to have the diagnosis confirmed. It may even be necessary to obtain tissue blocks to prepare more slides, to perform more extensive cytologic marker studies, and occasionally, to perform additional biopsies to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Staging

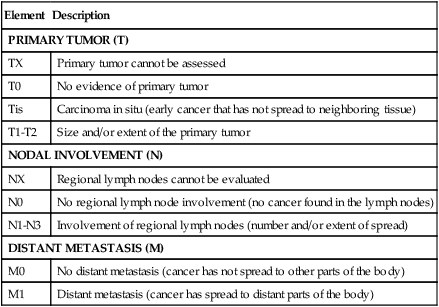

Staging is the classification of the anatomic extent of cancer in an individual. Specific stage groups categorize cancers of particular anatomic sites. Staging is essential in the treatment process and requires an understanding of the biology of cancer and the extent of disease. The tumor-node-metastasis classification, detailed in Table 25-2, is the global standard in cancer staging.

Table 25-2

| Element | Description |

| PRIMARY TUMOR (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (early cancer that has not spread to neighboring tissue) |

| T1-T2 | Size and/or extent of the primary tumor |

| NODAL INVOLVEMENT (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated |

| N0 | No regional lymph node involvement (no cancer found in the lymph nodes) |

| N1-N3 | Involvement of regional lymph nodes (number and/or extent of spread) |

| DISTANT METASTASIS (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis (cancer has not spread to other parts of the body) |

| M1 | Distant metastasis (cancer has spread to distant parts of the body) |

*Describes the anatomic extent of disease based on assessment of three components: primary tumor size and extent (T), regional lymph node involvement (N), and distant metastasis absent or present (M).

From American Joint Committee on Cancer. What is cancer staging? <http://www.cancerstaging.org/mission/whatis.html>; 2010 [accessed 29.01.13].

During the past decade, there has been a move to use minimally invasive techniques for the staging of a tumor. For instance, although staging for pancreatic cancer has been traditionally done by CT, peritoneal spread of the disease is difficult to interpret by this method. A minimally invasive laparoscopy allows for such a determination and can help determine inoperable candidates.20 One center’s negative exploration rate was reduced from 65% to 24% after the introduction of staging laparoscopy in the treatment protocol.20 In persons with breast cancer, routine axillary dissection has been replaced by sentinel lymph node biopsy as the standard of care.21 In validation studies for the procedure, accuracy rates ranged from 95% to 100%, yet the procedure carried significantly less morbidity than did axillary dissection. Only patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes currently undergo the more extensive procedure. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is also now routinely used in the staging of melanoma and shows promise as a procedure in persons with colorectal cancer.22,23

Recently, molecular characterization of sampled lymph node tissue has been shown to demonstrate evidence of tumor when standard cytology and histology cannot do so. The importance of such findings remains to be demonstrated and certainly will vary depending on the tumor. Increasingly, however, molecular characterization will determine therapy.24

Multidisciplinary Management

Although advances in multimodal therapy have changed the role of the surgeon in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, the surgeon continues to be a primary care provider for most patients with cancer and frequently coordinates care with other oncology specialists, including radiation and medical oncologists. Like the surgeon, the radiation oncologist provides an important modality of local and regional cancer therapy. Radiation therapy often is used after surgery to improve local disease control rates or even before surgery to reduce tumor bulk or downstage the tumor. It is also increasingly common for radiation to be combined with simultaneous administration of chemotherapy or radiation sensitizer agents. The medical oncologist’s responsibilities include administering and monitoring the patient’s chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and in some instances, biological therapy. Medical oncologists manage the toxicities of intravenous and oral anticancer therapy, and as a result, they provide considerable supportive care, especially as new agents have been developed to better control nausea and fatigue (see Chapters 42 and 45).

It is important and beneficial to the patient that these various caregivers work in a coordinated and collaborative effort toward the optimum outcome. Although surgical resection affects the rapidly dividing cancer cells by zero-order kinetics, both chemotherapy (including biologics) and radiation therapy effect cell killing by first-order kinetics. Only a fraction of the cells are killed by each treatment cycle, with some varied degree of regrowth between treatments. Whereas the processes we have learned are complementary, surgical resection increases the value of the others. A study in the United Kingdom examining standards of care in head and neck cancer showed increases in 2-year survival for patients assessed in a multidisciplinary clinic.25 An earlier study in skeletal and soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity also confirmed the benefits of multimodal management.26 The patients were treated with preoperative intraarterial doxorubicin and radiation therapy, radical surgical resection, and postoperative chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, resulting in the preservation of a functional extremity in 13 of 14 patients. The results of the combined-modality approach were significantly better than those obtained in patients managed with surgical resection alone or with a combination of surgery and another single modality, in terms of both short-term recurrence-free survival and salvage of a functional extremity.26

The surgical oncologist is not only involved with medical oncologists and radiation oncologists in developing the treatment plan but is also responsible for recognizing the need for input from other surgical cancer specialists (e.g., thoracic, urologic, plastic, head and neck, gynecologic, and orthopedic surgery) or the appropriateness of referring a patient to a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials has been shown to be of enormous benefit to patients with cancer. One study in patients with sarcoma noted that longer survival was associated with clinical trial participation in all age groups studied.27 Although the clinical trials may lack a surgical component, the surgical oncologist can help provide this benefit by keeping abreast of trials and enrolling eligible participants.

Advancing the development of multidisciplinary cancer care is a growing trend toward free-standing cancer care centers. The critical components of these centers are multidisciplinary cancer care, direct care and support services, a commitment to clinical trials, and a comprehensive program for quality assurance.28

Surgical Treatment of Cancer

Surgical Risk

Assessment of surgical risk is based on several factors. The physical status of the oncologic patient and the debilities that often accompany the disease process present specific challenges to the surgical team. Patients should undergo a complete evaluation before surgery, and any history of cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal disease should be documented. Emphasis should be placed on physiological function rather than chronologic age.29

The performance scales most widely used by oncologic specialists are the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale (ECOG-PS) and the Karnofsky Performance Status rating. These performance scales are also useful to surgeons and anesthesiologists in determining operative risk. A comparison of the ECOG-PS and Karnofsky Performance Status ratings showed both methods to be valid prognostic indicators of functional status, but the ECOG-PS seemed slightly superior. If necessary, each can be converted to the other with sufficient accuracy.30 These two classifications are outlined in Table 25-3.

Table 25-3

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale and Corresponding Karnofsky Rating

| ECOG-PS Grade | Description | Karnofsky Rating |

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry on all predisease activities without restriction | 100 |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity, but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature (e.g., light housework, office work) | 80-90 |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all self-care, but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours | 60-70 |

| 3 | Capable of only limited self-care; confined to bed or chair 50% or more of waking hours | 40-50 |

| 4 | Completely disabled; cannot carry on any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair | ≤30 |

ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scale.

Mortality caused by anesthetic complications is most often related to the physical status of the patient. Highly sophisticated techniques of anesthesia have increased the safety of major oncologic procedures, and many of these advances have their basis in modern cardiac surgery and in transplantation, especially liver transplantation. The choice of anesthetic technique and agent should be appropriate for both the procedure and the patient. For example, surgery in the lower abdominal area, lower extremities, or pelvis may be performed with general or spinal anesthesia, depending on the patient’s health status. The risk to the patient who has evidence of congestive heart failure would probably be increased by the use of general anesthesia as opposed to spinal anesthesia. However, patients with a history of ischemic heart disease may become agitated during a surgical procedure in which they are awake, thereby causing myocardial stress. The surgeon should work closely with the anesthesiologist to ensure proper selection of anesthetic application. Epidural-assisted general anesthesia is frequently used for abdominal surgery and provides an opportunity for improved pain management during postsurgical recovery.31

Surgery for Primary Cancer

At times, the cancer surgeon alone will be responsible for patient outcome, whereas at other times a combination of therapeutic modalities may enhance the prospect of cure or improved quality of life. Surgery should always be extended or restricted with these considerations in mind. The cancer surgeon must think first as an oncologist and attempt to envision the entire course of a particular disease and its treatment. The ultimate approach for the patient is multispecialty consultation that develops a consensus-based optimized course of therapy in the context of available clinical trials (the tumor board concept).32 If surgery is indeed the initial treatment option, then the surgeon may act on that conclusion.33

Appropriate treatment of primary cancer varies with the individual cancer type and the area involved. The cardinal principle of surgical cure is total removal of neoplastic tissue. This process involves avoiding implantation of loose tumor cells; minimizing iatrogenic, lymphatic, and vascular dissemination of cancer cells; and obtaining a complete margin of normal tissue around the primary tumor (Box 25-4).

As is the case for staging, minimally invasive extirpative procedures have been proposed for the definitive treatment of several malignancies. Laparoscopic procedures have been shown to be as effective as open surgery in certain cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, and liver, in colorectal cancer, and in urologic and gynecologic malignancies, among others.36–36 When the MIS procedures were initially introduced, concerns were raised because of isolated reports of port site metastases. However, later studies reported no increase in recurrence rates for laparoscopic procedures compared with open procedures.37 The feasibility of MIS for the management of malignant colorectal disease was not widely accepted until several randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic surgery with open surgery for colon cancer were published.38 Comparative studies are ongoing using laparoscopic techniques for rectal cancer; however, these techniques have not been universally accepted because of the more technical demands of the procedure and limited postoperative follow-up.39,40 In recent years, laparoscopic procedures have been enhanced by the use of surgical robots that allow for three-dimensional visualization and greater control over the intracorporeal manipulation of surgical instruments by remotely simulating arm, wrist, and hand motions made by a surgeon at the master console. Robotic surgery has been used to enhance laparoscopic procedures in a variety of cancer operations.41–45 Certain advantages afforded by robotic assistance in laparoscopic surgery have been touted by robotic surgeons, including improved fine-tissue dissection and ease of intracorporeal suturing of anastomoses, which have been challenges of conventional laparoscopy, particularly in advanced oncologic cases. Advances with laparoscopic surgical procedures with novel instrumentation and technology along with the added expertise of surgeons with laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques has facilitated the advent of LaparoEndoscopic Single-Site Surgery and Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery as the next evolutionary steps in MIS with efforts to further minimize incisional length with the goal of improving cosmesis and convalescence.48–48Combining preoperative CT or magnetic resonance with video image fusion as an augmented reality platform has been used to help in guiding the surgeon in dissection and identifying areas of pathology intraoperatively.51–51 Also, real-time imaging platforms have been reported during robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery to aid with microstructural identification during meticulous robotic surgical dissection.52 The potential to expand surgical treatment modalities ensures the future role of laparoscopic and robotic systems in centers equipped to support MIS. Furthermore, with expansion of the field of MIS to LaparoEndoscopic Single-Site Surgery and Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery, centers of excellence are expanding the frontier to scarless surgery with similar efficacy and oncologic outcomes.55–55

Comparison of Robot-Assisted vs Laparoscopic vs Open Surgical Procedures

Trabulsi et al.56 compared 275 patients who were treated using robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP) and 45 patients who underwent a pure laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) performed by the same surgeon. Patient, tumor, and perioperative characteristics, as well as functional outcomes, were evaluated. Preoperative patient and tumor characteristics were similar in both groups. Mean operative time, length of stay, estimated blood loss, and need for blood transfusion were significantly reduced among patients undergoing RALP. Continence at 12 months was better among those in the RALP group; in addition, RALP conferred 82% potency at 24 months compared with only 62% after LRP in men with preoperative potency who were undergoing bilateral nerve-sparing surgery. This report of the benefits of robot assistance compared with conventional laparoscopy comes as a follow-up to many publications that have reported the benefits of MIS (either RALP or LRP) compared with open radical retropubic prostatectomy.56–59

In a study by El Sahwi et al.60 comparing 155 cases of a robotic procedure versus 150 cases of open surgery for staging of endometrial cancer, it was reported that the “adequacy of the procedure” was not compromised but that the robotic cohort benefitted from reduced operative time and shorter hospital stays. A significantly lower incidence of postoperative ileus, infection, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and cardiopulmonary complications were also reported benefits in the robotic approach versus open surgery.

For intracranial tumors, stereotactic radiosurgery is gaining clinical acceptance. In a recent review by Levivier et al.,61 newly designed technologies including a gamma knife, robotic CyberKnife, and tomotherapy tools are described. Each targeted radiosurgical system has its inherent advantages and limitations; however, stereotactic radiosurgery technologies have continued to progress and offer novel advances as therapeutic tools not only in neurosurgery but also in other radiosensitive oncologic settings.62,63

Surgery for Metastases

In many cases, patients in whom a single site of metastatic disease has been detected can undergo resection with a reasonable rate of success. Many patients with a limited number of metastases to sites such as the liver, brain, or lung can be cured by surgical resection. For example, published experience indicates that resection of colorectal metastases to the liver should be performed when (1) the number of liver tumors is fewer than four, (2) extrahepatic tumor is not demonstrable, and (3) a tumor-free margin of at least 10 mm can be obtained. The 5-year survival rate is 30% to 40% when all of these criteria are met.64 The current management of metastatic colorectal cancer is a good example of a more aggressive approach to recurrent disease, where ablative procedures added to metastasectomy have greatly extended the options (see Chapter 77). Resection of pulmonary metastases in patients with soft-tissue and bony sarcomas can cure as many as 30% of patients. The surgeon must consider several elements before undertaking surgery for metastatic disease, including tumor histology, disease-free interval, tumor-doubling time, and the location, size, and extent of disease.

Surgery for Debulking

The results of experimental studies suggest that cytoreduction, or debulking of recurrent cancer, has important potential benefits. In the laboratory setting, reduction of the tumor increases the sensitivity of the remaining tumor to chemotherapy and radiation therapy by increasing the proportion of proliferating tumor cells, decreasing the number of therapeutic cycles necessary to eradicate the tumor, increasing cellular distribution of oxygen and nutrient within the tumor, and reducing the likelihood that resistant clones will develop.65

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has also been used to some effect for debulking in patients who have met selection criteria and have liver metastases of primary colorectal, breast, and neuroendocrine tumors. Patients treated with RFA had longer median survival times than did patients undergoing chemotherapy for the metastases.66 Among primary tumors, the use of RFA appears promising in hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and pulmonary neoplasia.66

Vascular Access

Placement of short-term and long-term indwelling central venous catheters has become a common surgical procedure for patients with cancer. These catheters provide venous access for chemotherapeutic infusion and withdrawal of blood. Several important developments in implantation technique and catheter design have decreased operative time and rendered placement of such catheters almost exclusively an outpatient procedure (see Chapter 26).

Future Directions

Cancer surgeons will encounter a greater requirement to work in a multidisciplinary fashion in patient care and will need to play an increasing role in risk assessment, management of genetic screening, and cancer prevention. As a result, cancer surgeons must be well trained in the fundamentals of cancer biology, pharmacogenetics, and genetics. Cancer surgeons must possess experience and skills in the design and management of clinical trials, monitoring of adverse events, and statistical evaluation of end points. The types of cancer operations and the scope of surgical resection may also change as molecular techniques enhance oncologic treatment.67