Special Issues in Pregnancy

Jorge J. Castillo and Tina Rizack

• Cancer complicates 1 in 1000 pregnancies; the most common malignancies in pregnant women are breast, uterine, and cervical cancer, lymphoma, and melanoma.

• No evidence exists that pregnancy alters the clinical behavior of cancer, but cancer often is advanced at diagnosis because of the overlap of symptoms with those of a normal pregnancy.

• Important factors in management include assessment of gestational age, maternal staging with limited exposure to ionizing radiation, the urgency of therapy, and the impact of therapy on maternal prognosis and fetal outcome.

• Physiological changes in pregnancy affect the metabolism of chemotherapy drugs, but few practical guidelines exist about how dosing should be adjusted to take this factor into account.

• Alkylators and antimetabolites should be avoided in the first trimester, but these agents and other cytotoxic drugs are generally not contraindicated (with the possible exceptions of methotrexate and hydroxyurea) in the second and third trimesters.

• The scheduling of chemotherapy should be planned to minimize the risk of complications at the time of delivery.

• No evidence exists that exposure to chemotherapy results in long-term adverse effects on physical or intellectual development, and surviving children have no increased risk of malignancy.

• Therapeutic radiation jeopardizes fetal outcome and should be reserved for the postpartum period whenever possible.

• Subsequent pregnancy after cancer diagnosis and treatment is usually possible.

Introduction

This chapter focuses on the issues related to the care of women with cancer that is diagnosed during pregnancy. Cancer is the second leading cause of death in women between the ages of 20 and 39 years and complicates 1 in 1000 pregnancies. The most common cancers diagnosed in pregnant patients are the same as those seen in nonpregnant women of similar age: breast, uterine, and cervical cancer, lymphoma, and melanoma.1 Although pregnancy is associated with immunologic tolerance, no evidence exists of an increased incidence of cancer or of more aggressive behavior of malignancies that are diagnosed during pregnancy. However, many cancers in pregnancy are diagnosed at an advanced stage, often because symptoms of the malignancy overlap with those that are experienced during a “normal” pregnancy.

Fetal Development and Physiology

Because most chemotherapy drugs are uncharged, lipophilic, of low molecular weight, and minimally protein bound, they cross the placenta to the fetal circulation. The placenta is the primary portal of exit of waste products and toxins from the fetus. However, the metabolites are generally more polar than the parent compound, might not cross the placenta as easily, and hence may accumulate in fetal tissues or amniotic fluid. The fetal liver can metabolize drugs as early as 7 to 8 weeks of pregnancy, but the extent to which fetal liver and kidneys participate in drug elimination is minimal.2

Maternal Physiology: Relevance to Chemotherapy and Surgery

Pregnancy induces a number of important physiological changes that cause significant alterations in the metabolism and efficacy of commonly used medications (Box 64-1). However, few data exist to guide physicians in adjustment of drug dosing (see the Chemotherapy Dosing section).

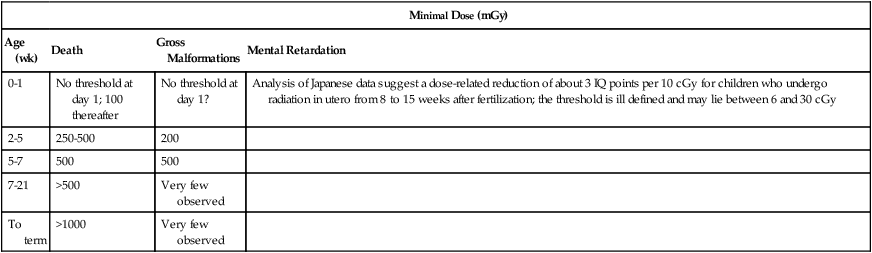

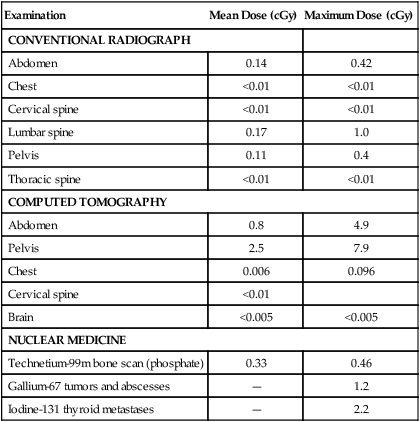

Diagnostic Radiology for Staging

Radiation can be divided into ionizing and nonionizing radiation. Ionizing radiation has the ability to penetrate tissue and damage cellular DNA, resulting in mutation and ultimately affecting the development and viability of the fetus. Numerous studies of radiation exposure after the atomic bomb detonations in Japan confirmed that this effect is dependent on radiation dose and stage of fetal development at the time of exposure (Table 64-1).3 Fetal abnormalities associated with exposure to excessive ionizing radiation include microcephaly, eye malformation, and growth retardation.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations for imaging during pregnancy state that 5-cGy exposure to the fetus is not associated with any increased risk of fetal loss or birth defects.5 Radiation exposure is well below this amount for most procedures except for the maximum dose with computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen and pelvis (Table 64-2). A more relevant concern is an increased risk of childhood cancer. After a gestational age of 3 to 4 weeks, the number of excess cancer cases (leukemia and solid tumors) up to age 15 years after radiation in utero is estimated to be 1 in 17,000 per 0.1 cGy. The baseline cancer risk in the first 15 years is about 1 in 650, and thus fetal doses of 2.5 cGy will approximately double the risk; however, this represents an excess lifetime fatal cancer risk of less than 0.5%.

Table 64-1

Estimates of Threshold Doses for Effects After Fetal Radiation in Utero

| Minimal Dose (mGy) | |||

| Age (wk) | Death | Gross Malformations | Mental Retardation |

| 0-1 | No threshold at day 1; 100 thereafter | No threshold at day 1? | Analysis of Japanese data suggest a dose-related reduction of about 3 IQ points per 10 cGy for children who undergo radiation in utero from 8 to 15 weeks after fertilization; the threshold is ill defined and may lie between 6 and 30 cGy |

| 2-5 | 250-500 | 200 | |

| 5-7 | 500 | 500 | |

| 7-21 | >500 | Very few observed | |

| To term | >1000 | Very few observed | |

Table 64-2

Typical Ranges of Fetal Doses* After Common Diagnostic Procedures

| Examination | Mean Dose (cGy) | Maximum Dose (cGy) |

| CONVENTIONAL RADIOGRAPH | ||

| Abdomen | 0.14 | 0.42 |

| Chest | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cervical spine | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Lumbar spine | 0.17 | 1.0 |

| Pelvis | 0.11 | 0.4 |

| Thoracic spine | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY | ||

| Abdomen | 0.8 | 4.9 |

| Pelvis | 2.5 | 7.9 |

| Chest | 0.006 | 0.096 |

| Cervical spine | <0.01 | |

| Brain | <0.005 | <0.005 |

| NUCLEAR MEDICINE | ||

| Technetium-99m bone scan (phosphate) | 0.33 | 0.46 |

| Gallium-67 tumors and abscesses | — | 1.2 |

| Iodine-131 thyroid metastases | — | 2.2 |

*The radiation doses have been estimated from surveys conducted in the United Kingdom for a range of diagnostic radiology.

Ultrasound, CT Scan, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Ultrasound is believed to be safe during pregnancy and can be particularly useful in assessing the breasts and liver.6 CT scans and noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are being used with increasing frequency during pregnancy and lactation. Radiation doses from CT of the head and chest are minimal.7 CT should be used as the initial study for suspected pulmonary embolism. Noncontrast MRI does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and there has been no indication that noncontrast MRI during pregnancy has produced deleterious effects. Contrast agents such as gadolinium cross the placenta and are contraindicated. MRI of the abdomen is limited by motion artifact of the bowel.

Position Emission Tomography Scanning

Pregnancy is a relative contraindication to positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with use of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose as a radiomarker, but termination is not generally recommended if a patient is found to be pregnant after undergoing a PET scan. A PET/CT scan has a representative dose of 8 mGy (PET) and 0.3 cGy (CT). The dose to the fetus may be higher because of close proximity of the mother’s bladder, where 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose is excreted.

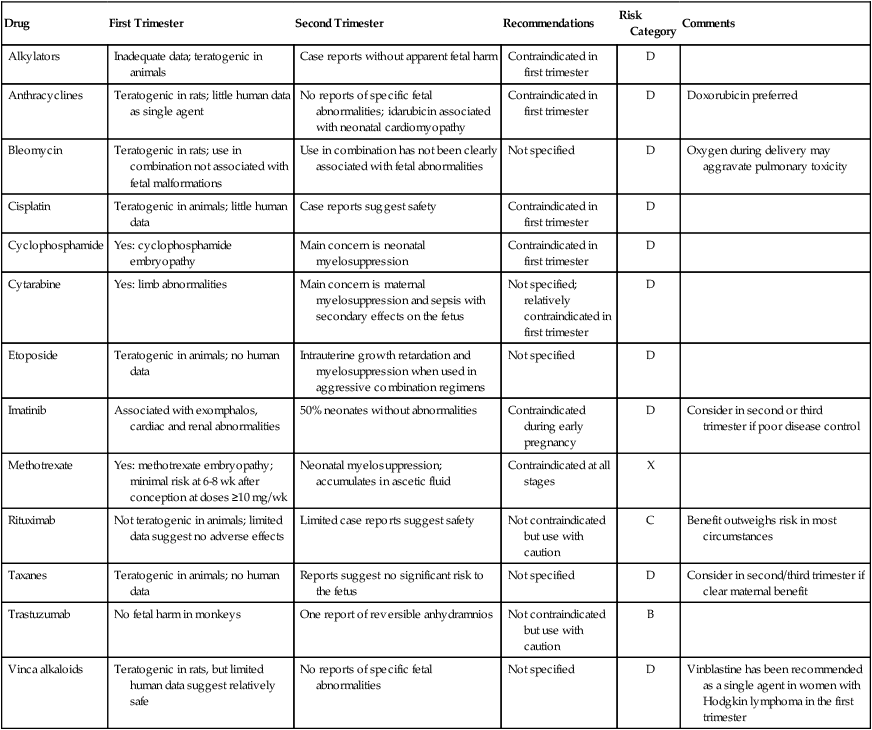

Teratogenicity of Chemotherapy

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined risk categories for all drugs based in part on the evidence in animals of fetal harm (Table 64-3). The majority of chemotherapeutic agents are category D, for which there is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on adverse reaction data from investigational or marketing experience or studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks. Extrapolation of teratogenic and mutagenic effects of chemotherapeutic agents from animals to human organogenesis is difficult, however, because of differences in susceptibility between species.8 The timing of fetal drug exposure is critical. Administration of drugs within 1 week of conception may result in a spontaneous abortion or a healthy fetus. During the first trimester, when organogenesis occurs, drugs may produce congenital malformations and/or result in spontaneous abortion. Other factors that may influence the probability of teratogenesis include the frequency of drug administration, duration of exposure, synergistic effects of multiple drugs, use of radiation, and individual genetic susceptibility.

Table 64-3

Food and Drug Administration Risk Categories for Drugs Administered During Pregnancy

| Category | Description |

| A | Controlled studies in women do not show risk to the fetus during the first trimester; there is no evidence of risk in late trimesters, and the possibility of fetal harm is remote |

| B | Animal reproduction studies have not shown a fetal risk, but no controlled studies in pregnant women have been performed; or animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility), but this effect has not been confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (no evidence exists of a risk in later trimesters) |

| C | Studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic, embryocidal, or both), and no controlled studies have been performed in women, or studies in animals and women are unavailable; drugs should be given only if potential benefit justifies the risk to the fetus |

| D | Positive evidence of human fetal risk exists, but the benefits from use in pregnant women may be acceptable despite the risk (if the drug is needed in a life-threatening situation for which other safer drugs are not available) |

| X | Studies in humans and animals have shown fetal malformations; there is evidence of fetal risk based on human experience or both; the risk of use in a pregnant woman clearly outweighs any potential benefit; this drug is contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant |

Most human data about chemotherapy during pregnancy involve small series or case reports, which are prone to reporting bias. Specific or systemic information about the teratogenicity of individual cytotoxics or modern multiagent chemotherapy regimens is limited, particularly in the first trimester. Many reported malformations have occurred after exposure to multiple agents, making it difficult to assign blame to a single causative agent. It is important to note that the overall incidence of major congenital malformations with chemotherapy use after the first trimester is approximately 3% (close to the risk of the general population), although the incidence of minor malformations may be as high as 9%, and between 10% to 15% of all pregnancies result in a miscarriage or spontaneous abortion.9 Extrapolation from older data also might not be appropriate, because many of these drugs (e.g., alkylating agents such as nitrogen mustard and busulfan and antimetabolites such as aminopterin) are now rarely used. Limited experience in the first trimester with regimens such as Adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) and cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), Oncovin (vincristine), and prednisolone (CHOP) suggests low rates of teratogenicity.10 In the second and third trimesters, drugs very rarely cause significant malformations but could impair fetal growth and development. The current available literature suggests that chronic prenatal chemotherapy exposure does not result in learning or behavioral problems (also known as functional teratogenesis).10,11 Overall, the use of systemic antineoplastic therapy alone appears to be accompanied by significantly lower risk than is commonly appreciated.

Specific Chemotherapy Drugs

Table 64-4 details the available experience on the use of some of the more commonly used chemotherapy drugs in animals and at various stages of human pregnancy, together with the FDA category.12–37 The recommendations are those published by Briggs and colleagues,13 with some additional comments from the authors. The choice of chemotherapy agents should be based on the most current available literature.

Table 64-4

Summary and Recommendations for Chemotherapy Drug Experience in Pregnancy

| Drug | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Recommendations | Risk Category | Comments |

| Alkylators | Inadequate data; teratogenic in animals | Case reports without apparent fetal harm | Contraindicated in first trimester | D | |

| Anthracyclines | Teratogenic in rats; little human data as single agent | No reports of specific fetal abnormalities; idarubicin associated with neonatal cardiomyopathy | Contraindicated in first trimester | D | Doxorubicin preferred |

| Bleomycin | Teratogenic in rats; use in combination not associated with fetal malformations | Use in combination has not been clearly associated with fetal abnormalities | Not specified | D | Oxygen during delivery may aggravate pulmonary toxicity |

| Cisplatin | Teratogenic in animals; little human data | Case reports suggest safety | Contraindicated in first trimester | D | |

| Cyclophosphamide | Yes: cyclophosphamide embryopathy | Main concern is neonatal myelosuppression | Contraindicated in first trimester | D | |

| Cytarabine | Yes: limb abnormalities | Main concern is maternal myelosuppression and sepsis with secondary effects on the fetus | Not specified; relatively contraindicated in first trimester | D | |

| Etoposide | Teratogenic in animals; no human data | Intrauterine growth retardation and myelosuppression when used in aggressive combination regimens | Not specified | D | |

| Imatinib | Associated with exomphalos, cardiac and renal abnormalities | 50% neonates without abnormalities | Contraindicated during early pregnancy | D | Consider in second or third trimester if poor disease control |

| Methotrexate | Yes: methotrexate embryopathy; minimal risk at 6-8 wk after conception at doses ≥10 mg/wk | Neonatal myelosuppression; accumulates in ascetic fluid | Contraindicated at all stages | X | |

| Rituximab | Not teratogenic in animals; limited data suggest no adverse effects | Limited case reports suggest safety | Not contraindicated but use with caution | C | Benefit outweighs risk in most circumstances |

| Taxanes | Teratogenic in animals; no human data | Reports suggest no significant risk to the fetus | Not specified | D | Consider in second/third trimester if clear maternal benefit |

| Trastuzumab | No fetal harm in monkeys | One report of reversible anhydramnios | Not contraindicated but use with caution | B | |

| Vinca alkaloids | Teratogenic in rats, but limited human data suggest relatively safe | No reports of specific fetal abnormalities | Not specified | D | Vinblastine has been recommended as a single agent in women with Hodgkin lymphoma in the first trimester |

Refer to the text for additional comments.

Adapted from Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe ST. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005.

Antimetabolites

Methotrexate is widely distributed, including into fluid spaces such as amniotic fluid, and when given during the first trimester it is closely associated with fetal abnormalities, characterized by cranial dysostosis, hypertelorism, micrognathia, limb deformities, and mental retardation. In fact, methotrexate is commonly used in combination with misoprostol during the first trimester to medically induce abortions. However, methotrexate does not uniformly cause malformations, and a critical dose and timing may exist above which fetal malformations occur.24 Exposure to methotrexate in the latter trimesters has not been associated with significant malformations,13 but its elective use at this time, particularly in high doses, is still not recommended.

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) was associated with multiple congenital malformations in the fetus of a patient who was found to be pregnant at week 14 after she began receiving chemotherapy for colon cancer at week 12 and hence is not recommended for use during the first trimester.38 Multiple studies have shown safe use beyond the first trimester in combination therapy.39,40 Use of cytosine arabinoside during the first trimester, alone and in combination with other drugs, has also been associated with congenital anomalies.36 Capecitabine is an oral drug akin to 5-FU that is used in persons with bowel and breast cancer. Capecitabine is embryotoxic in animals, is classified as a category D drug, and is not recommended for use during pregnancy.

Use of hydroxyurea is believed to be unsafe during pregnancy because of a case series of 31 patients in which an increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation, intrauterine fetal demise, and prematurity was noted.41 Whether this finding was due to underlying disease is unclear. No data for cladribine or fludarabine exist in the literature.

Alkylating Agents

Alkylating agents are commonly used in the treatment of lymphoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer. Cyclophosphamide is the most widely used and the best studied. Use in the first trimester has been associated with some fetal abnormalities, tempered with several reports with no abnormalities. Second and third trimester use is believed to be safe. Regarding dacarbazine use during pregnancy, congenital abnormalities were seen in two cases during the first trimester, consisting of isolated microphthalmos with secondary severe hypermetropia and a unilateral floating thumb malformation and one fetal death. In the second or third trimester exposure, one fetus died and one case of minor malformation (syndactyly) was observed. In all cases, dacarbazine was administered with several other cytotoxic drugs.42 Exposure to chlorambucil during the first trimester has been reported to cause renal aplasia, cleft palate, and skeletal abnormalities.43

Platinum Derivatives

Regarding cisplatin and carboplatin, a number of case reports documenting platinum use after the first trimester have not noted any congenital malformations.22,33 Oxaliplatin is embryotoxic in animals, is classified as a category D drug, and is not recommended for use during pregnancy, although one case has been reported without adverse outcomes.44

Taxanes

Although data are limited, the use of taxanes appears feasible and safe during pregnancy based on placental expression of drug-extruding transporters such as P-glycoprotein and BCRP-1, which result in low fetal exposure.45 Forty cases have been reported in the literature, including use of paclitaxel (21 cases), docetaxel (16 cases), and both drugs (3 cases).46 Ninety-five percent were treated after the first trimester and 95% received taxanes concomitantly with other chemotherapy. Despite the inherent bias in case reports, the pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and docetaxel and available data suggest that these drugs appear safe for use in the second and third trimesters in cases where benefit is believed to outweigh risk.

Vinca Alkaloids

Although vinblastine is highly teratogenic in animal models, the literature suggests that its use in the first trimester may be relatively safe. In a series of patients treated with single agent vinblastine for Hodgkin lymphoma, no adverse outcomes to the pregnancy or in infants who were followed up afterward were reported.47 No congenital malformations were reported in 11 pregnancies when exposure to vincristine occurred, with exposure in three pregnancies occurring in the first trimester.19 Vinorelbine, vinblastine, and vincristine had been used during the latter trimesters without harm to the fetus.10,14

Anthracyclines

Little information is available about the effects of anthracyclines during pregnancy when they are used as single agents. Few malformations have been reported when anthracyclines are used in combination regimens in the first trimester. A few studies have shown acute myocardial dysfunction after anthracycline use in a minority of fetuses.48,49 However, a study of 81 children with in utero chemotherapy exposure, including anthracylines, who were followed up until age 9 to 29 years, showed that cardiac function did not differ from the general population.11 Idarubicin is more lipophilic, which favors placental transfer; it has been associated with neonatal cardiomyopathy, and its use during pregnancy is not recommended.32 Doxorubicin is preferred to daunorubicin and has been used in combination therapy in a prospective single-arm study of 57 pregnant women with breast cancer in the second or third trimester. No stillbirths, miscarriages, or perinatal deaths were observed.50 Similar findings have been reported in smaller series.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 protein (HER2), is used in breast and gastric cancers. HER2 is strongly expressed in fetal renal epithelium. In a case series of 15 patients exposed to trastuzumab in utero, three fetuses had renal failure and four died. In addition, oligohydramnios or anhydramnios was present in eight pregnancies.51 Trastuzumab is not recommended for use during pregnancy.

Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody with an antiangiogenic effect, is used to treat multiple cancers. Because it is teratogenic in animals, consistent with a crucial role of angiogenesis during normal fetal development,51 bevacizumab should not be administered to pregnant women.

Rituximab is a chimeric anti-CD20 IgG1 antibody that can cross the placenta and interact with fetal B cells. The few reports that have been published seem to indicate safe use of rituximab in pregnancy in all trimesters when given for both oncologic and nononcologic indications.16,18,21,23,26,31,52 Transient B-cell depletion in the neonate followed by full immunologic recovery and normal response to vaccinations has been reported in four cases.16,18,23,53 Rituximab is labeled pregnancy category C.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Of the multitude of tyrosine kinase inhibitors available, the most published data regarding use during pregnancy pertains to imatinib, which is used to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). In a series of 180 women who were exposed to imatinib in pregnancy, with data available for 125, 12 infants were born with abnormalities, among which 3 had similar complex combinations of defects.28 On the basis of these data, imatinib cannot be recommended for use during pregnancy. Fewer data exist for dasatinib and nilotinib.

Erlotinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is used in persons with metastatic lung and pancreatic cancer. Two case reports with no adverse outcomes have been published.54,55

No or little data are available on use of the following tyrosine kinase inhibitors during pregnancy:

Other Agents

When administered during the first trimester, all-trans retinoic acid, which is used to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia, is associated with an 85% risk of teratogenicity, and when used with chemotherapy, it is associated with an increased rate of miscarriage.56 The use of all-trans retinoic acid alone or with chemotherapy in the second and third trimester has been shown to have generally favorable outcomes in the mother and fetus.

Interferon alpha is believed to only minimally cross the placenta because of its high molecular weight. Forty cases of interferon used in pregnancy for a variety of hematologic disorders and eight cases in the first trimester showed no mutations. One case of fetal malformation was seen when used in conjunction with hydroxyurea.57

Minimal human data are available with respect to the following agents:

• Topoisomerase-1 inhibitors such as topotecan (used to treat ovarian and small cell lung cancer) and irinotecan (used to treat colorectal cancer and non–small cell lung cancer)

• Arsenic trioxide (used to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia)

• Asparaginase (used to treat acute lymphocytic leukemia)

• Bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor used to treat multiple myeloma)

• Bendamustine (an alkylating agent used to treat non-Hodgkin lymphomas)

• 5-Azacitidine and decitabine (hypomethylating agents used to treat myelodysplastic syndromes)

• Romidepsin and vorinostat (histone deacetylase inhibitors used in T-cell lymphomas)

• Everolimus and temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitors used to treat renal cell cancer)

Supportive Care

Regarding the prevention of nausea and vomiting, consensus on the safe use of metoclopramide, 5-HT3 antagonists, NK1 antagonists, and corticosteroids during pregnancy have been established.58 For corticosteroids, methylprednisolone or hydrocortisone are extensively metabolized in the placenta, and thus relatively little crosses into the fetal side.59 Methylprednisolone and hydrocortisone are preferred over dexamethasone/betamethasone both for use as an antiemetic and for the prevention of anaphylaxis.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is not teratogenic in rats, and no congenital malformations or toxicities attributable to G-CSF have been reported in humans.9 G-CSF is a category B drug and should not be withheld during pregnancy if there is significant potential benefit to the mother. Safe use in pregnancy has been documented,60 as well as in the prevention of recurrent miscarriage.61

Recombinant human erythropoietin (category C) does not cross the human placenta and does not appear to present a major risk to the fetus.13 The benefit when used appropriately for maternal anemia appears to outweigh any known or potential risks.

Chemotherapy in Pregnancy: Overview

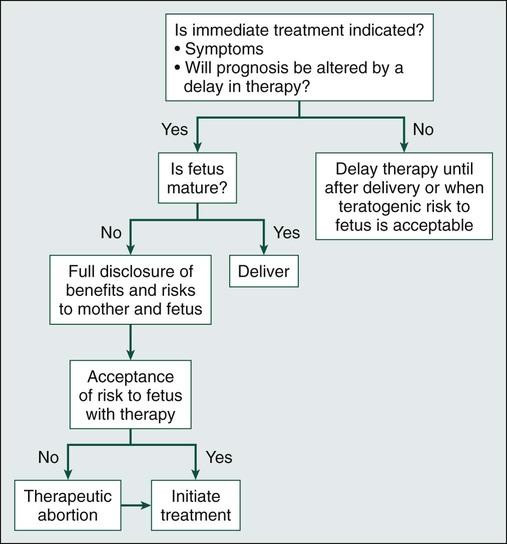

An overview of the approach to treatment is detailed in Figure 64-1.

The administration of most chemotherapeutic agents in the second and third trimesters has not been associated with specific adverse effects on the fetus; hence, in general, chemotherapy-based treatment of the underlying malignancy at this stage of pregnancy should not be delayed and should follow the same guidelines as for nonpregnant women. The main risk to the fetus appears to be a result of neutropenic sepsis, anemia, and nutritional deficiency in the mother.48 The parents can be assured that long-term studies have shown that in the absence of chemotherapy-embryopathy, children who are exposed to chemotherapy in utero are not different physically or intellectually from matched control subjects, and there is no suggestion of a significantly increased risk of malignancy in the neonate (i.e., transferred from the mother) or in long-term follow-up.10,11

Chemotherapy Dosing

An anecdotal observation of fewer chemotherapy-related side effects during antenatal treatment compared with identical chemotherapy postpartum has been reported,48 which is consistent with the physiological changes in pregnancy that lead to lower plasma levels and reduced area under the concentration × time curve. Pharmacokinetic studies have not been performed. Accordingly, particularly when given with curative intent, chemotherapy doses should not be empirically dose-reduced. Dosing should be the same as for nonpregnant patients, and the dose should be determined according to the patient’s increasing weight.

Specific Malignancies

Breast Cancer

The incidence of breast cancer during pregnancy is estimated to be 1 in 3000.62 Women with a genetic predisposition to breast cancer, particularly BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, might be overrepresented in this group but do not have an increased risk of breast cancer in pregnancy.63 All patients diagnosed with breast cancer during pregnancy should be referred for genetic counseling. During pregnancy, breast cancer most often manifests as a painless mass or thickening. Rarely breastfeeding women may notice a “milk rejection sign,” in which the infant refuses the breast that contains an occult carcinoma.64,65

Diagnosis may be difficult and is often delayed because of a number of factors, including physiological changes in pregnancy such as engorgement, hypertrophy, and nipple discharge. Although pregnant women are more likely to be seen with advanced stage disease than are nonpregnant women,66 current data are inconclusive regarding the prognosis of women who are diagnosed and treated for breast cancer during pregnancy in comparison with nonpregnant women.11 Little evidence exists to show the disease is accelerated by pregnancy.

Histologic and immunohistochemical findings for breast cancer in pregnancy are similar to those in nonpregnant women of similar age. The majority of breast cancers in pregnancy are invasive ductal cancers that have a high grade (40% to 95%), feature lymphovascular invasion, and are estrogen and progesterone hormone receptor negative. Tumors tend to be larger and are associated with a higher incidence of nodal involvement (53% to 71%) than in nonpregnant patients.69–69 Data on HER2 status varies between 28% and 58%, and it remains unclear whether HER2 status is different from that of age-matched control subjects.11,70,71 However, stage-specific survival is similar to that of nonpregnant patients.66,72 Placental metastases from breast cancer have been reported, but rarely, and there are no reports of fetal involvement.73

Any suspicious or persistent breast mass in pregnancy warrants further investigation. The principles of diagnosis are similar to those for nonpregnant women. Mammography is safe, because the radiation dose to the fetus is negligible with abdominal shielding, but mammography may be associated with high false-positive rates. Ultrasonography can distinguish solid from cystic masses. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the breast is contraindicated. Core biopsy is preferred over fine-needle aspiration biopsy, which can be misleading in pregnant patients. Use of the services of an experienced pathologist who is aware that the patient is pregnant is preferable. If a core biopsy is nondiagnostic, solid masses should be subject to excisional biopsy. Staging can be deferred until after delivery if the risk is believed to be low. Safe staging procedures include a chest radiograph with abdominal shielding, ultrasound, and MRI without contrast. A chest CT scan is not contraindicated (see “Diagnostic Radiology for Staging”), but a noncontrast MRI of the thorax is preferred, largely because of a lower cumulative radiation dose. A skeletal MRI is preferred for the detection of suspected bone metastasis. If findings are uncertain on MRI or MRI is unavailable, a modified bone scan may be performed (with half the usual trace dose and double the acquisition time) with maternal hydration to limit fetal radiation exposure from radionuclides in the adjacent maternal bladder.74,75 The serum alkaline phosphatase level rises physiologically during pregnancy and is not useful as an indicator of bony metastases. The liver may be evaluated with ultrasound.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for the treatment of nonmetastatic breast cancer during pregnancy are available.76 International expert recommendations have also been published.77 Treatment should not be unnecessarily delayed unless delivery is planned within the next 2 to 4 weeks. Therapeutic abortion does not appear to alter maternal survival.

Considerations and selection of optimal local therapy are similar to that recommended in nonpregnancy-associated breast cancer. Breast and axillary surgery during any trimester appears to be reasonably safe for the mother and is associated with minimal fetal risk. Both radical mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery are options. Axillary lymph node dissection is important, because nodal metastases are common and nodal status may affect the choice of adjuvant therapy. The use of sentinel lymph-node dissection is controversial but may safely be used because absorbed doses are well below the fetal threshold. Blue dye should be avoided because of the risk of a maternal anaphylactic reaction, which could lead to fetal distress. A 1-day protocol is preferred.78

In general, therapeutic radiation should be avoided during pregnancy because of significant risk to the fetus, including pregnancy loss, malformation, disturbances of growth or development, and mutagenic and carcinogenic effects. The calculated exposure to the fetus depends on both the dose administered and the gestational age—as much as 20 cGy in early pregnancy and 700 cGy in late pregnancy, which are above the acceptable limits.62 Accordingly, mastectomy is a consideration in early gestation when radiation therapy must be significantly delayed. If necessary, a balanced discussion of potential risks and harms for the patient and developing fetus should take place. Breast-conserving surgery is an option in the second or early third trimester with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or by itself late in the third trimester.

Adjuvant chemotherapy should be delayed to beyond the first trimester. 5-FU, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide have been the most commonly used agents. Anthracylines are believed to be safe, but prospective data and outcomes in children exposed in utero are limited. Dose-dense regimens should be avoided because of a scarcity of data. Although data are limited, the use of taxanes appears feasible and safe during pregnancy. In 40 case reports of taxane use after the first trimester with 27 cases involving breast cancer, minimal maternal, fetal, or neonatal toxicity was reported.46,74 A taxane may be considered beyond the first trimester if the likelihood of maternal benefit is strong.

Trastuzumab is contraindicated in pregnancy. The FDA recommends against in utero exposure of trastuzumab because of reported fetal deaths, pulmonary hypoplasia, and fetal developmental abnormalities. Trastuzumab causes oligohydramnios and anhydramnios, but severity appears to be linked to the duration of exposure. Long-term use should be avoided, but short-term use appears to be less toxic.11 Data are lacking for bevacizumab and lapatinib, and their use during pregnancy should be avoided. Tamoxifen is contraindicated because of its association with spontaneous abortion, birth defects, fetal death, and, in pregnant rats, breast cancer in female offspring.77

No evidence exists that a future pregnancy worsens the prognosis with respect to recurrence, at least in patients with early stage cancer.79 However, most oncologists advise women to wait 2 to 3 years before becoming pregnant again, because the risk of recurrence is highest during this time.

Cervical Cancer

Approximately 1% to 3% of women diagnosed with cervical cancer are pregnant or postpartum.80,81 In 70%, the cervical cancer is stage I at diagnosis.82 Cervical cancer is one of the most common malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, probably because of routine Papanicolaou screening. As a result, cervical cancer is often detected early, and advanced disease is rare. Symptoms such as vaginal bleeding or discharge may overlap with those of pregnancy. Human papillomavirus is involved in the majority of cases. No evidence exists that the relative immunosuppressive state of pregnancy modifies the aggressiveness of human papillomavirus infection.83

Recommendations for diagnostic procedures after abnormal cervical screening are the same as for nonpregnant women, which is generally colposcopy. Endocervical curettage is contraindicated. If no evidence of invasive carcinoma is present, treatment can be delayed until after delivery, and patients are followed up with colposcopy every trimester with repeat biopsies if progression is suspected.82 Conization for diagnosis during pregnancy is indicated only for confirmation of invasive disease that would alter the timing or mode of delivery,84,85 and it is associated with a 5% to 15% risk of hemorrhage, miscarriage, preterm labor/delivery, and infection.85,86

Cervical cancer is staged clinically by the extent of tumor and nodal status. During pregnancy, noncontrast MRI is the preferred imaging modality for the assessment of locoregional disease.87 Ultrasound may also be used. A chest radiograph with abdominal shielding is recommended for evaluation of pulmonary metastases for all patients with more than microscopic cervical cancer. Lymphadenectomy may be indicated for selected patients at significant risk for lymph node metastases if results would alter management, such as delaying treatment. Case reports of successful laparoscopic lymphadenectomy during pregnancy have been published.88–91

Management recommendations differ according to disease stage, term of pregnancy, histologic subtype, the mother’s belief regarding termination, and future childbearing desires. For stage IA1 disease, serial clinical examinations and colposcopy with each trimester is recommended. At delivery, an extrafascial hysterectomy should be offered to women who have completed childbearing. If advanced disease is diagnosed and the fetus is viable, then delivery by cesarean section is recommended, followed by commencement of therapy. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a consideration if treatment needs to be delayed for fetal indications. If the fetus is not viable and stage IIB–IVA disease is detected, treatment should be directed with curative intent. Chemoradiation should be initiated promptly, which will lead to abortion of the fetus within 3 weeks.92 Several international guidelines have been published, but they generally differ on the treatment of tumors less than 2 cm and the treatment of locally advanced disease (stage IB2–II).58,93

Melanoma

Although overall there is a male preponderance of melanoma, age-specific incidence rates are higher among women until age 40 years, leading to speculation that some causes may be hormonally driven.94 However, no clear evidence exists that exogenous hormone use increases the risk,95 that the incidence of melanoma is higher in pregnancy,96 or that pregnancy influences the prognosis.97 Early lesions should be excised with adequate margins. Metastases may be palliated with excision, when appropriate, with possible long-term survival.98,99 Standard therapies for melanoma are largely palliative, and only case reports of use in pregnancy exist; standard therapies are not advised during pregnancy. An approach to the management of pregnant women with high-risk melanoma has been published.100 Melanoma is the most common malignancy associated with transplacental metastases to the fetus. With placental involvement, the fetal risk of melanoma metastasis is approximately 22%, with a high fatality rate in affected infants.101

Ovarian Cancer

Although ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecological malignancy observed in pregnancy, it is rare, affecting 1 in 10,000 to 100,000 deliveries.74,102,103 The majority of cases are diagnosed early because of the frequent use of pelvic ultrasound and generally have germ cell or low malignant potential histology.63,64 Ultrasound is usually adequate for preoperative staging. Tumor markers (e.g., AFP, hCG, CEA, and CA125) in pregnancy are unreliable because many markers are elevated as a result of fetal development, and they fluctuate with gestational age; they can also be elevated because of abnormal placentation or fetal abnormalities.104 An elevated α-fetoprotein and inhibin A level, which is used for screening Down syndrome and neural tube defects, can be indicative of a germ cell tumor.

General consensus guidelines are for surgical resection of tumors that persist into the second trimester, are greater than 10 cm, or are shown by ultrasound to have solid or mixed solid and cystic components.107–107 Surgical staging and treatment of ovarian neoplasms includes debulking surgery, consisting of omentectomy, lymph node and peritoneal biopsy, and assessment of peritoneal washings. Attempting to leave as much of the reproductive tract in situ as possible is favored. If the corpus luteum is removed before 8 weeks’ gestation, postoperative progesterone supplementation should be initiated.108

Use of chemotherapy to treat ovarian cancer during pregnancy is rare. For epithelial tumors, a single-agent platinum derivative, such as carboplatin or cisplatin, is recommended followed by a regimen that includes paclitaxel after delivery with a goal of six cycles of total chemotherapy, although some limited data on safe use of combination therapy after the second trimester have been reported.33,109,110 Germ cell tumors are typically treated with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. Experience with these agents in the latter trimesters of pregnancy with this combination is limited but has been associated with prematurity and ventriculomegaly in only one report.82,111 Neoplasms with a low potential for malignancy are treated with surgery alone.

Malignant Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

Malignant gestational trophoblastic disease includes persistent/invasive gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, choriocarcinoma, placental site trophoblastic tumors, and epithelioid trophoblastic tumors. Gestational trophoblastic disease is a highly malignant vascular neoplasm of the cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast that readily metastasizes, and it can be preceded by any gestational event; most arise after a hydatiform mole or a spontaneous abortion or after a normal pregnancy. Diagnosis concurrent with a normal pregnancy is extremely rare.112 A scoring and risk factor system for gestational trophoblastic disease from the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has been published; chemotherapy recommendations depend on the FIGO risk score.113 In tumors that are diagnosed after pregnancy, a high cure rate can be achieved with single-agent chemotherapy (usually methotrexate) for low-risk disease, but responses are lower in high-risk disease, for which multiagent chemotherapy is the treatment of choice.114 However, the cure rate for gestational trophoblastic disease concurrent with pregnancy is poor. Simultaneous gestational trophoblastic disease in the mother and infant is rare but may be curable in both if it is recognized and treated early.115 Pregnancy should be avoided for at least 1 year after treatment because of the significant risk of relapse within the first year and because pregnancy can lead to a delay in diagnosis.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer during pregnancy is rare, occurring in approximately 0.002% of all pregnancies.116 Underlying risk factors such as hereditary or familial syndromes and long-standing inflammatory bowel disease are likely to be particularly relevant in this younger age group.117 Unlike the general population, in which only 20% to 25% of colon cancers occurs in the rectum, a higher incidence of 64% to 86% of pregnant women with colon cancer have right-sided tumors.118 Ovarian metastases may be more common, occurring in 25% of patients compared with 3% to 8% in nonpregnant patients.117

Diagnosis may be delayed because of the similarity of symptoms of colon cancer and pregnancy such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, and altered bowel movements. Sigmoidoscopy is safe and usually adequate given the prevalence of distal tumors in pregnancy. Although the safety of colonoscopy during pregnancy is not well established, the limited literature suggests no increase in adverse outcome to the mother or fetus.117 In 2005, the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy issued guidelines for endoscopy during pregnancy and lactation that include deferring endoscopy to the second trimester whenever possible, preferred use of meperidine and midazolam for sedation, positioning of the patient in the left pelvic tilt or left lateral position, and monitoring of the fetus.119 Carcinoembryonic antigen levels in pregnancy are usually normal but may be elevated and are not useful for screening.120 They may be useful for monitoring and prognosis.

Serum β-HCG may be elevated because of ectopic production by the cancer cells.72 Abdominal ultrasound and noncontrast MRI are safe, but CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis, especially in the first trimester, is problematic (see the section on radiology).

Surgical recommendations are complex and are based on the gestational age of the fetus, the tumor stage, and the need for emergent versus elective surgery. The general consensus is that if the patient is diagnosed at less than 20 weeks’ gestation, termination of the pregnancy is recommended because of the significant risk of tumor progression should the pregnancy continue. After 20 weeks, resection may be delayed until after fetal viability.121 Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU or related drugs such as capecitabine is contraindicated in the first trimester. Data on chemotherapy for colon cancer in pregnancy are limited but indicate that 5-FU and leucovorin may be safe and should be used in cases where the benefit is believed to outweigh the risk.122 Data for the addition of oxaliplatin and, especially, irinotecan is too limited to recommend use. Delaying adjuvant chemotherapy is an option, but whether the beneficial effect is maintained is unclear. Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy is contraindicated during pregnancy. Survival is generally poor because of late presentation and advanced pathological stage but is no different from that in the general population when stratified for pathologic stage.116,118

Thyroid Cancer

The most common presentation of thyroid cancer is that of an asymptomatic nodule. The outcome does not appear to be affected by pregnancy.123,124 Recommendations include delaying surgery until after delivery for indolent tumors.124,125 When surgery is delayed, ultrasound should be performed each trimester and surgery should be performed if a significant increase in size is found.126 Conventional chemotherapy is not particularly effective in resistant disease, and use of radioactive iodine is not recommended during pregnancy.

Other Cancers

Gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and hepatic cancers are very rare in pregnant women, except for gastric cancer in pregnant women in Japan. Delays in diagnosis are common. Genitourinary malignancies are rare, although the risk of renal cell cancer may be increased by pregnancy.127 Lung cancer, although rare, has a poor prognosis in pregnancy because of the advanced stage and diagnosis,22, 54 and metastasis of small cell carcinoma from mother to fetus has been reported.22,128 Sarcomas are rare in pregnancy. There appears to be no interaction between pregnancy and the natural history of osteogenic carcinoma.129 Successful delivery of chemotherapy to the mother has been reported for Ewing’s sarcoma, along with a case with metastases to the placenta in a patient with recurrence.130,131

Hematologic Malignancies

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of 1 : 1000 to 1 : 6000, is the most common lymphoma in pregnancy.132 Reasonable options for staging in pregnancy include a CT scan of the neck and chest with MRI of the abdomen and pelvis. The majority of patients who are found to have Hodgkin’s lymphoma during pregnancy do not require immediate intervention. Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients can be monitored carefully, with treatment reserved for threatening or more symptomatic disease; many patients can carry the pregnancy to term without any treatment becoming necessary.14 Options for symptomatic disease that is diagnosed in the first trimester include single-agent chemotherapy or multiagent chemotherapy with or without a prior therapeutic abortion. No large studies of the teratogenic effects of commonly used regimens such as ABVD in the first trimester have been conducted, although the limited literature has not demonstrated any adverse effect.10,48 Vinca alkaloids, doxorubicin, bleomycin, and steroids appear to be relatively safe in the first trimester, but alkylators such as cyclophosphamide and dacarbazine may be teratogenic. Options for the first trimester that have been proposed include ABV or vinblastine alone.14,48 Mantle field radiotherapy for supradiaphragmatic disease has not been associated with adverse fetal effects, because the estimated fetal dose after uterine shielding is below the threshold for major congenital malformations.132 Nevertheless, it is rarely indicated, and its use during pregnancy cannot be considered standard because of the lack of reliable clinical data on late effects. Multiagent chemotherapy regimens, such as ABVD, appear to have minimal fetal risk when administered during the second or third trimester.48 More recently, Evens and colleagues133 reported minimal maternal-fetal complications in a retrospective study including 22 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who were treated with ABVD during the second and third trimester of pregnancy. Data are also mounting on the safety of chemotherapy during the first trimester. Aviles and colleagues134 reported on 12 patients receiving ABVD for Hodgkin lymphoma during the first trimester of pregnancy without evidence of spontaneous abortions or congenital malformations.

An option is single-agent vinblastine, which almost always induces some disease regression and allows disease control until after delivery, at which time multiagent chemotherapy can be delivered.14 These alternatives—that is, (1) prompt potentially curative chemotherapy with protocols such as ABVD after counseling that there does not seem to be an increased risk of congenital birth defects or of significant long-term neurologic sequelae or (2) minimizing fetal risk by delay of definitive therapy until after delivery—need to be discussed in each case, considering factors such as symptoms and aggressiveness of the tumor. Supradiaphragmatic radiation is problematic in the third trimester, because fetal exposure is increased as a result of uterine proximity. The role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma is controversial, but this approach is occasionally used in patients with relapsed disease after an autograft. In the absence of a histocompatible sibling, alternative sources of allogeneic stem cells include marrow, peripheral stem cells, or cord blood from an unrelated donor. Stem cell transplant in pregnancy is contraindicated, but cryopreservation of umbilical cord blood at delivery is an issue that might need to be addressed in some patients with high-risk disease.135

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma in pregnancy is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000. Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma usually does not require immediate therapy.135 The non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes that are most likely to require treatment in pregnancy are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. These lymphomas are usually aggressive and advanced at diagnosis in pregnancy with a higher incidence of breast, uterine, cervical, and ovarian involvement, perhaps related to increased vascularity.132 The current standard therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is rituximab-CHOP (R-CHOP), with consideration of the addition of involved field radiotherapy for localized disease.136 Treatment delay is rarely advisable in the first trimester but may be a consideration in some patients with relatively indolent disease clinically. A recommended option has been a therapeutic abortion followed by standard chemotherapy.132 However, experience with CHOP-based regimens in the first trimester suggests that the risk of teratogenicity is low; Avilés and Neri10 reported no adverse fetal outcome in 17 mothers with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma who were treated in the first trimester with CHOP-bleomycin or similar regimens.10 This finding suggests that CHOP-based chemotherapy, preferably without an alkylator initially, is a reasonable consideration during the first trimester when treatment is required without delay and termination is not acceptable. Prompt administration of R-CHOP chemotherapy is recommended in the second trimester.

In the case of Burkitt lymphoma, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends against the use of standard R-CHOP because it is considered insufficient therapy.137 The most commonly used combination regimens for Burkitt lymphoma include hyper-CVAD, CODOX-M/IVAC, and the Magrath regimen, usually administered with rituximab. All these intensive regimens include high doses of methotrexate, a well-known teratogenic agent. Based on the aggressiveness of the disease, the intensity of the regimens, and the potential of cure in patients with Burkitt lymphoma, the recommendation during early stages of pregnancy is to terminate the pregnancy and treat patients with standard regimens.57 Additionally, given the increased fetal risk with high doses of methotrexate, it is probably reasonable to refrain from using this agent until the third trimester is reached.138

An important issue is the safety of rituximab during pregnancy. In a number of randomized studies, this agent has been shown to improve outcome in aggressive CD20-positive non-Hodgkin lymphoma and represents a major therapeutic advance.136 Administration of rituximab during organogenesis in monkeys had no obvious adverse effect on embryo or fetal development apart from the expected pharmacologic effect of B-cell depletion, because IgG is known to cross the placental barrier.139 The available literature in human pregnancy is limited. One of the largest studies to date evaluated the rituximab global drug safety database and identified 231 pregnancies associated with maternal exposure to rituximab.140 Of 153 pregnancies with known outcomes, 90 (59%) resulted in live births, of which 22 (24%) were premature; one neonatal death occurred at 6 weeks. Eleven neonates (12%) had hematologic abnormalities, mainly lymphopenia, and two (2%) had congenital malformations. It is important to note that not all the patients included in this study received rituximab for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and more than half of the patients received other concurrent therapies and immunosuppressants. In a more recent retrospective multiinstitutional study, approximately 20 patients were treated with R-CHOP for non-Hodgkin lymphoma during the second and third trimester of pregnancy with minimal maternal or fetal complications, with the exception of one stillbirth at 19 weeks after one cycle of R-CHOP.133 Two reports of exposure to rituximab without chemotherapy in the first trimester have described delivery of healthy, normal babies with no immunologic deficits.23,26 Four reports of CHOP (or CHOP-like)-rituximab chemotherapy in the second trimester described delivery in all cases of healthy babies with subsequent normal immunologic reconstitution.16,18,21,29 Two babies had detectable rituximab levels at birth with severe B-cell lymphopenia but subsequently achieved normal immunologic status at 3 to 4 months without infectious sequelae in the interim.16,18 One report of rituximab in the third trimester described no toxicity apart from asymptomatic transient neonatal neutropenia.31 The approved product information states that rituximab should not be given to a pregnant woman unless the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk. A reasonable position is to recommend rituximab as part of combination chemotherapy during pregnancy because, in the authors’ opinion, the available evidence suggests that the maternal benefits outweigh the fetal risk.

Acute Leukemia

The presence of acute leukemia and/or its treatment has been associated with increased incidence of premature birth, stillbirths, and intrauterine growth retardation, particularly early in pregnancy.48 Contributing factors other than chemotherapy include sepsis, anemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Treatment is generally required without delay, irrespective of gestational age, because delay may increase both fetal and maternal mortality. The most common type of acute leukemia in adults is acute myeloid leukemia, for which the usual chemotherapy is cytarabine (with at least one high-dose course) and an anthracycline such as daunorubicin or idarubicin. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults is less common; induction treatments are less standard and more complex than in acute myeloid leukemia, and generally include cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and steroids. Consolidation treatments in persons with acute lymphoblastic leukemia characteristically include high-dose methotrexate. The risk of teratogenicity appears to be confined to the first trimester, particularly with methotrexate, other antimetabolites, thioguanine, and alkylating agents.48 Cytarabine has been associated with limb malformations after first trimester exposure.36 Other chemotherapy drugs such as vincristine, anthracyclines, and prednisolone appear to be relatively safe. A large review including more than 63 cases of acute lymphoblastic and 89 cases of acute myeloid leukemia in pregnant women found 31 cases with adverse fetal outcome—12 neonates with intrauterine growth retardation, 11 fetal deaths, 6 neonates with congenital abnormalities, and 2 neonatal deaths.48 On the other hand, a smaller study by Avilés and Neri10 reported the outcome of 29 pregnancies that were complicated by acute leukemia: acute myeloid leukemia in 19 patients and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the remainder.10 All were treated with standard antileukemic protocols; 11 received chemotherapy during the first trimester. No congenital abnormalities were observed, there was no evidence of intrauterine growth retardation, and no excess of complications was seen in long-term follow-up in the children. General principles of management include the following:

• In the first trimester, a therapeutic abortion is probably the recommendation of choice, particularly in women with acute myeloid leukemia, because of concern about the teratogenicity of the optimal chemotherapy. Methotrexate is absolutely contraindicated.

• In the second and third trimesters, it is reasonable to treat with standard regimens without inducing an abortion, because at this time no convincing data exist that the relevant chemotherapy is teratogenic. However, the mother needs to be counseled about the fetal risks from maternal sepsis, anemia, and coagulopathy. High-dose methotrexate is inadvisable, and the administration of high-dose cytarabine is arguably best deferred until after birth, because experience with this schedule during pregnancy is minimal.

• If possible, chemotherapy should be avoided 3 to 4 weeks prior to delivery to reduce maternal and/or fetal complications resulting from cytopenias.57 Maintaining platelets at greater than 30 to 50/109/L is recommended, especially around the time of delivery, to allow for regional anesthesia, and maintaining hemoglobin at greater than 9 g/dL is recommended as well, because perinatal complications increase as the hemoglobin declines.135,141 Neonatal blood counts should be checked at delivery. Neonates are at risk of transient myelosuppression and cardiomyopathy after administration of idarubicin.32

• Use of prednisolone rather than dexamethasone is recommended because of concern of repeated fetal exposure to dexamethasone and adverse neurologic sequelae.135 Steroids may increase the risk of diabetes because of increased insulin resistance in pregnancy.

• L-Asparaginase is commonly used in acute lymphoblastic leukemia protocols. Limited experience suggests that this drug does not pose a major risk to the fetus when it is used beyond the first trimester. However, L-asparaginase has been associated with thromboembolism; this association is related to reduced levels of antithrombin III.142 The risk may be higher in pregnancy, which is a hypercoagulable state. Consideration should be given to prophylactic infusion of antithrombin III concentrates if L-asparaginase is administered during pregnancy or in the first 6 weeks thereafter.

• Acute promyelocytic leukemia is optimally treated with all–trans-retinoic acid, usually in combination with an anthracycline.143 Retinoic compounds are teratogenic in animals, which has led to FDA approval of a centralized pregnancy risk management program for isotretinoin preparations. First-trimester acute promyelocytic leukemia should be managed with a therapeutic abortion followed by chemotherapy that includes all–trans-retinoic acid. However, the literature includes a number of reports of safe and effective use of all–trans-retinoic acid in the second trimester and beyond.144,145

• Arsenic is another agent active in acute promyelocytic leukemia. No data are available on the effect of therapeutic doses of arsenic in pregnancy, but epidemiological studies in women with chronic exposure to arsenic found in drinking water reported an increase in stillbirths and an increase in spontaneous abortions.146 These observations argue strongly against the use of arsenic in pregnancy at any stage.

Chronic Leukemias

Of the chronic leukemias, CML is the condition that is most likely to require treatment in pregnancy. Imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib are considered the treatment of choice in newly diagnosed cases of CML in the chronic, accelerated, or blastic phase, although data are more extensive with imatinib.147 Imatinib is teratogenic in rats (but not rabbits) during organogenesis at ≥100 mg/kg, doses that are equivalent to >800 mg/day in adults based on body surface area.148 Defects include exencephaly, encephalocele, and skull bone abnormalities with fetal loss in all animals. Postimplantation loss occurred at doses ≥45 mg/kg, approximately equivalent to 400 mg/day. The product information from Novartis recommends that imatinib not be used in pregnancy. A recent publication reported on 180 cases of women who were exposed to imatinib during pregnancy.28 Timing of exposure by trimester was known in 146 cases; of these, 71% involved exposure in the first trimester. Outcome data were known for 125 cases (63%): normal live infant (n = 63; 50%), elective termination (n = 35; 28%, including three following identification of fetal abnormalities), fetal abnormality (n = 12; 10%), and spontaneous abortion (n = 18; 14%). The fetal abnormalities included bony defects similar to those seen in animal models, as well as an excess incidence of exomphalos. No data were presented on crucial issues such as the relationship of dose to the incidence and the nature of fetal abnormalities or whether abnormalities were confined to first-trimester exposure. The MD Anderson group reported the outcome of CML in 10 women in whom imatinib was discontinued immediately after pregnancy was identified.149 Six patients had an increase in Philadelphia-positive metaphases during pregnancy. All resumed treatment with imatinib after the abortion or birth, and nine achieved complete hematologic remission with varying levels of cytogenetic response with a median follow-up of 18 months (5 to 40 months). Within the caveats of this limited experience, the following guidelines are suggested:

• In the first trimester, cease use of imatinib immediately. Counsel that there might be an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and fetal abnormalities, although the risk is probably not high enough at 400 mg/day to recommend termination of the pregnancy. No meaningful experience is available at doses in excess of 400 mg/day. Monitor CML and institute treatment with leukapheresis or interferon, if therapy is required. Use of interferon is thought to be safe in all trimesters.150 Hydroxyurea is teratogenic at high doses in animals but has not been associated with major malformations in human pregnancies, even with first trimester exposure.151 Consider reintroduction of imatinib at 400 mg/day in the second and third trimesters if CML is poorly controlled with these other measures and the mother’s health is compromised.

• In the second and third trimesters, cease use of imatinib and administer interferon if therapy is required, but consider resumption as described previously.

• Postpartum, resume imatinib as quickly as practical. It should not be administered to women who are breastfeeding.

In patients seen with accelerated phase, the risks and benefits of tyrosine kinase therapy should be discussed with consideration of termination of the pregnancy. If the patient presents with a blastic phase during early stages of pregnancy, termination is mandatory because therapy mimics that of acute leukemia.

Other Considerations

Therapeutic Abortion

Therapeutic Radiation

Radiation therapy is commonly used in the treatment of patients with breast cancer, cervical cancer, and lymphoma, and systemic iodine-131 is often used for treatment of thyroid cancer. The use of radiation therapy is addressed in the sections devoted to these cancers. Radiation is extremely important for palliation of cancer-related symptoms and has been carefully used during pregnancy without fetal harm.152