Rehabilitation of Individuals with Cancer

• As cancer treatment improves, more patients are living longer with functional limitations, and quality of life issues become as important as survival.

• Rehabilitation must be patient centered and goal oriented. It requires an interdisciplinary team and the active participation of the patient.

• Impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions from cancer dramatically impact quality of life but are amenable to rehabilitation efforts.

• The focus of rehabilitation varies with the phase of the disease process.

• Important impairments include pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorders, paresis, feeding difficulties, bone and soft tissue involvement, and bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction.

• Activity limitations can be ameliorated with training in activities of daily living, exercise, and adaptive equipment.

• Participation in home, vocational, and recreational activities plays a critical role in quality of life. Economic burdens, environmental barriers, and transportation problems often need to be addressed.

Introduction

The National Cancer Institute Dictionary of Cancer Terms defines rehabilitation as “a process to restore mental and/or physical abilities lost to injury or disease, in order to function in a normal or near-normal way.”1 Rehabilitation is critical to improving quality of life (QOL) for cancer survivors and maintaining dignity for persons with terminal illness. Rehabilitation requires several components to be successful.

The World Health Organization has recently published an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, which is meant to supplement the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10).2 It presents a series of definitions that are crucial to understanding the role of rehabilitation in improving quality of life. These definitions are listed in Box 55-1. In this chapter, we will focus on impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in patients with cancer and discuss how rehabilitation can ameliorate these disabilities.

Epidemiology of Cancer Disability

The number of cancer survivors continues to grow because more people are living longer with cancer as a result of new advances in surgery, medical, and radiation oncology.3 The result is that increasing numbers of patients face more years with cancer-related disability. Cancer survivors who are older than 55 years have significantly more pain and deficits in self-care and mobility than do control subjects.4 Focus needs to be directed away from mere survival toward the preservation and improvement of QOL for these survivors. In Japan, for example, the number of breast cancer survivors with lymphedema and pain in the chest wall, axilla, and arm is expected to double by 2020.5

Which Patients Should be Referred for Cancer Rehabilitation and When?

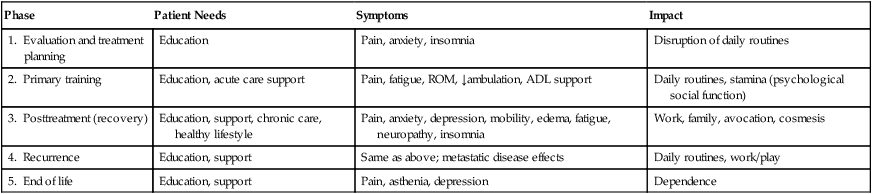

Patients with cancer can benefit from rehabilitation at every phase of the disease (Table 55-1). Clinicians should ask the patient the simple question: “Has your ability to function changed?” Because cancer is a complex, chronic illness, management requires vigilance and a comprehensive and preventive approach to illness and disability. The major concerns of persons with cancer include their overall health, fitness, fatigue, emotional and social function, and pain, which may vary during different phases of the disease. For example, in the initial phase, anxiety and disruption of routines may present the greatest challenges. During the treatment phase, fatigue, nausea, and sleep disruption may be the most significant problems. If the patient is having difficulty with mobility, self-care, fatigue, or pain, referral to a cancer rehabilitation program may be appropriate. Guidelines for referral for breast cancer rehabilitation have been published.6

Table 55-1

Phases of Cancer Rehabilitation

| Phase | Patient Needs | Symptoms | Impact |

| 1. Evaluation and treatment planning | Education | Pain, anxiety, insomnia | Disruption of daily routines |

| 2. Primary training | Education, acute care support | Pain, fatigue, ROM, ↓ambulation, ADL support | Daily routines, stamina (psychological social function) |

| 3. Posttreatment (recovery) | Education, support, chronic care, healthy lifestyle | Pain, anxiety, depression, mobility, edema, fatigue, neuropathy, insomnia | Work, family, avocation, cosmesis |

| 4. Recurrence | Education, support | Same as above; metastatic disease effects | Daily routines, work/play |

| 5. End of life | Education, support | Pain, asthenia, depression | Dependence |

Impairments

Pain

Virtually every patient with cancer experiences pain during the course of the illness, and the pain often can become debilitating.7 Pain severity correlates closely with function, as demonstrated in one study of 216 Chinese patients with cancer who had metastatic disease.8 In that study, patients with increasing severity of pain had poorer function, whereas patients with mild, well-controlled pain functioned similarly to persons without pain.

Fatigue

Cancer-related fatigue has been described as “overwhelming and sustained exhaustion and decreased capacity for physical and mental work…not relieved by rest.”9 In addition, fatigue has been shown to have a negative impact on one’s economic status, social, and emotional status.10 It has been demonstrated that improving the quality of sleep is helpful, but increasing the amount of “rest” is not effective in reducing the symptoms of cancer-related fatigue.11 Exercise has been shown to mitigate fatigue.12 A further discussion of fatigue is provided in Chapter 45.

Delirium and Cognitive Dysfunction

In studies of patients with advanced cancer, the incidence of delirium ranges from 20% to 86%.13 Delirium may be reversible in 50% of cases with proper identification and management.14 The etiology of delirium in persons with cancer is usually multifactorial. Accurate assessment is critical for effective treatment. Risk factors for the development of delirium in patients undergoing bone marrow transplant before transplantation included lower cognitive function, lower physical function, and higher blood urea nitrogen, alkaline phosphatase, and magnesium levels.15

Medications play a large role in the development of delirium. In a study of 216 hospitalized patients with cancer, use of corticosteroids, opioids, and benzodiazepines was most frequently associated with delirium.16 The clinician must also consider metabolic factors. Fever and sepsis often produce acute delirium, and dehydration and uremia frequently contribute to the condition. Hypoxia and hypoglycemia are additional factors that can be easily assessed.

Patients with cancer often report cognitive difficulties after chemotherapy and other treatment regimens. However, a new study indicates no significant differences in the long-term cognitive function of cancer survivors versus control subjects.17 Many of these reports of cognitive difficulty may relate to fatigue.

Mood Disorders

Although most patients cope well, a significant number experience serious mood disorders. Estimates of the prevalence of depression among patients with cancer range from 15% to 25%.18 Anxiety is quite common and may be related to poorly controlled pain, abnormal metabolic states, or medication-related adverse effects. Patients may also experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in response to cancer diagnosis and treatment. PTSD is an anxiety disorder that develops after an extremely stressful event, such as the development of a life-threatening illness. Within 5 years of diagnosis, between 10% and 15% of cancer survivors may meet the criteria for PTSD.19

Neurologic Impairments

Hemiplegia

Brain tumors vary widely in aggressiveness and prognosis. The extent to which tumor type or location has an impact on rehabilitation outcomes is not clear. However, one study found a tendency for greater gains in patients with meningiomas and left hemispheric lesions. Patients receiving inpatient acute rehabilitation show similar gains regardless of whether they have a primary brain tumor or a brain tumor resulting from metastatic disease.20 Some studies have shown that patients with a brain tumor have shorter lengths of stay on acute rehabilitation units compared with patients who have other noncancerous brain disorders.21

Most patients with brain tumors have multiple impairments depending on tumor location and size and the volume of tissue excised at surgery. In a study of patients undergoing acute rehabilitation, the most common neurologic deficits included impaired cognition (80%), weakness (78%), and visual-perceptual dysfunction (53%).20 Rehabilitation efforts should focus on the patient’s neurologic and functional status, co-existing medical problems, and tolerance of physical activity. As for patients who have had a stroke or traumatic brain injury, goal setting should be appropriate to the individual’s physical, cognitive, and behavioral status and include early planning for postacute rehabilitation care.

Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

The incidence of cancer-related spinal cord injury (SCI) may exceed that from trauma and represents the most frequent type of nontraumatic SCI.21 Spinal cord metastases produce a clinical syndrome characterized initially by pain in 90% of cases, followed by weakness, sensory loss, and sphincter dysfunction. Weakness is present in 74% to 76% of patients, autonomic dysfunction is present in 52% to 57% of patients, and sensory loss is present in 51% to 53% of patients.22,23 Pain alone may persist for a month or more (average 6 weeks) before significant neurologic changes develop. Acute onset of back or neck pain in a patient with cancer should be considered to be spinal metastasis until proven otherwise.

Positive results have been demonstrated after rehabilitation for persons with disability from spinal cord tumors.22 Factors that have been identified as better prognostic indicators for survival after inpatient rehabilitation include lymphoma, myeloma, breast and kidney cancer, spinal cord injury as the presenting symptom, slow progression rate of neurologic symptoms, combined surgery and radiation treatments, partial bowel control, and partial independence with transfers on admission.

Speech/Swallowing/Nutrition

Disorders of speech and swallowing may be the result of direct tumor invasion of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, esophagus, or adjacent structures or the result of surgical or radiation treatment, or they may be consequent to cancers of the nervous system that affect pharyngeal or laryngeal control. Head and neck cancers constitute about 3% to 5% of all malignancies. Preservation of swallowing, having a natural airway, and intact speech are critical components that affect QOL in patients with head and neck cancer. Among these patients, swallowing has been shown to have the largest impact on global QOL.24

Bone Tumors and Amputations

Bone metastases are a frequent source of cancer-related physical impairment that requires the active involvement of the rehabilitation team. Challenges for the treating team arise when metastatic bone lesions produce severe pain that limits function or imposes risks of fracture during therapeutic exercise or mobility. The incidence of pathological fracture among all tumor types is about 8%, with breast carcinoma responsible for the majority of these fractures. Sixty percent of all long bone fractures involve the femur, with most of these fractures involving the proximal portion.25 If the patient is deemed at risk for a pathological fracture, he or she should not bear weight on the affected structure, pending orthopedic consultation.

Patients with cancer who experience pathological fractures and associated functional deficits have been shown to make significant gains when admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation hospital unit.26

Soft Tissue Impairments Associated with Cancer Diagnoses

Cancer, its treatments, or both can cause significant soft tissue abnormalities. One of the most frequently observed abnormalities is lymphedema, that is, extremity swelling that results from disruption of the lymphatics after axillary or groin dissection. The use of manual lymph drainage and compression garments is effective in controlling edema. When applied early in the course of treatment, before the development of significant volume increase (e.g., >250 mL increase in the arm), lymphedema can be reversed.27 Traditionally, patients with lymphedema have been told not to lift weights. However, new data show that not only does weightlifting not worsen lymphedema, but it may be beneficial.28

Another frequently seen complication of cancer treatment is radiation fibrosis. This process is associated with vascular permeability, inflammation, and release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukins and transforming growth factor–β) and continues well past cessation of the radiation therapy. The use of antifibrotic agents in the treatment of this problem has shown promise.29

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation has prolonged life for many persons with hematologic malignancies. One of the complications of this procedure is rejection of the host by the transplanted, immunocompetent engrafted cells, called graft versus host disease. The immunologic reaction is often brisk, resulting in organ damage (fibrosis) to the lung, liver, and notably skin and soft tissue. In the chronic form of graft versus host disease, limb edema, peau d’orange, fasciitis, and enthesitis can occur, resulting in significant loss of joint motion. Subsequent muscle atrophy may occur as a result of disuse and associated loss of upper and lower extremity mobility.30

Sexual Function

Sexual function can be very important to patients with cancer, yet it is seldom discussed by the patient and physician. In persons with breast cancer, treatment often produces adverse effects of fatigue, nausea, and diminished vaginal lubrication, not to mention the significant body image changes that accompany mastectomy. A metaanalysis of 36 studies of sexuality in patients with testicular cancer showed that problems were largely related to ejaculatory dysfunction, but fortunately, rates of decreased sexual desire were low and may improve with time.31 Erectile dysfunction is a common adverse effect of prostatectomy and hormonal and radiation therapy in persons with prostate cancer. Colorectal cancer surgeries often lead to sexual dysfunction in men. Not surprisingly, gynecologic cancers often produce changes in vaginal sensation, structure, and lubrication. On a positive note, however, 63.5% of patients with cancer who received brief sexual counseling reported improvement.32

Activity Limitations

Activities of Daily Living

When persons become disabled enough to require assistance with these skills, the burden generally falls on caregivers. In one study of 483 patients with cancer at varying stages of their disease course, 18.9% had unmet needs in their ADLs because of a lack of a suitable caregiver.33 In patients with advanced-stage cancer, the percentage of caregivers with a high level of psychological distress varies from 41% to 62%, directly depending on the functional status of the patient.34

Rehabilitation efforts, particularly with the involvement of occupational therapy, can significantly reduce this burden on caregivers and enhance the QOL for patients with cancer who have disabling impairments. Addressing functional loss from impairments of the upper limb, such as chemotherapy-related peripheral neuropathy of the hand or radiation-induced brachial plexopathy, can substantially improve performance of ADLs. Simple adaptive aides (Fig. 55-1) can help patients achieve everyday tasks. To improve feeding independence among patients with cancer who have upper limb neurologic dysfunction, Chinese researchers used positioning, feeding aid supports, and upper limb supports and significantly improved function during a 3-week treatment intervention.35 Home-based occupational therapy interventions produce a high level of patient and caregiver satisfaction, reducing the burden of care.

Exercise for Patients with Cancer

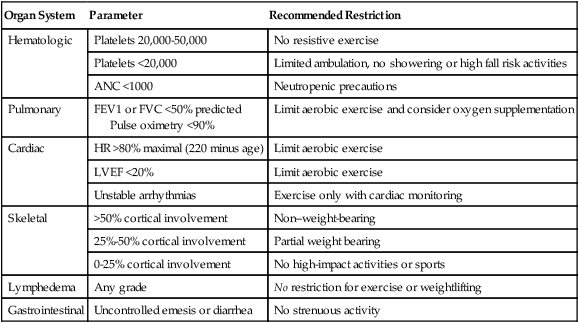

Exercise is one of the most effective strategies for symptoms associated with cancer fatigue, sleep disruption, and abnormalities of mood, physical function, and QOL.36 Metaanalyses37 suggest that for adults with a variety of cancer diagnoses and who are receiving a variety of exercise interventions, exercise improves physical function, QOL, and cardiorespiratory fitness and decreases cancer-related fatigue.38,39 The great majority of these studies employ aerobic exercise, using ergometry and walking programs and, occasionally, aquatic therapies. Table 55-2 outlines contraindications for exercise.

Table 55-2

Contraindications to Exercise in Patients with Cancer

| Organ System | Parameter | Recommended Restriction |

| Hematologic | Platelets 20,000-50,000 | No resistive exercise |

| Platelets <20,000 | Limited ambulation, no showering or high fall risk activities | |

| ANC <1000 | Neutropenic precautions | |

| Pulmonary | FEV1 or FVC <50% predicted Pulse oximetry <90% |

Limit aerobic exercise and consider oxygen supplementation |

| Cardiac | HR >80% maximal (220 minus age) | Limit aerobic exercise |

| LVEF <20% | Limit aerobic exercise | |

| Unstable arrhythmias | Exercise only with cardiac monitoring | |

| Skeletal | >50% cortical involvement | Non–weight-bearing |

| 25%-50% cortical involvement | Partial weight bearing | |

| 0-25% cortical involvement | No high-impact activities or sports | |

| Lymphedema | Any grade | No restriction for exercise or weightlifting |

| Gastrointestinal | Uncontrolled emesis or diarrhea | No strenuous activity |

Participation Restrictions

Family and Social Relationships

Cancer can often draw a family together; however, it just as often leads to significant distress for families. Support groups can be helpful, yet fewer than half of patients receive information about them, even in large tertiary oncology centers.40 In one study of 121 patients with cancer, caregiver QOL was significantly correlated to the social/family and functional dimensions of the patients’ QOL; physical and emotional dimensions did not correlate.41 Cancer also can place significant economic burdens on families. Indeed, cost considerations play a large role in patient decision making regarding cancer treatment, especially among the poor.

Vocational Rehabilitation

Work disability after a cancer diagnosis is a common occurrence. Short and Vargo42 conducted phone interviews of 1433 cancer survivors at 1 to 5 years after diagnosis. More than half had quit work during their first year after cancer diagnosis, but fortunately, three quarters of those subsequently returned to work. A projected 13% had indefinite work disability. Survivors of central nervous system, head and neck, and stage IV blood and lymph malignancies had the highest risk of quitting work.

Little is known about which medical impairments have the greatest impact on employability. Undoubtedly cognitive and communication deficits play a large role, as evidenced by the high work disability rates among survivors of central nervous system and head and neck malignancy.42 Fatigue and pain are also likely to limit work participation. Spelten and colleagues43 studied 235 cancer survivors in the Netherlands. Fatigue levels strongly predicted inability to return to work.

Participation in Recreation

Recreation is critical to physical and mental well-being. Fatigue, pain, weakness, depression, and other impairments will limit cancer survivors’ participation in avocational pursuits. The benefits of recreational activities include improvements in fitness, musculoskeletal problems, immune system function, cognition, and sleep. One study examined 97 European youngsters attending a summer camp for adolescents living with cancer and diabetes.44 Significant improvements were seen in self-esteem, self-efficacy, and anxiety. Adults benefit as well. For example, 11 small studies have shown that Tai Chi Chuan, an Asian mind-body practice, has beneficial effects for cancer survivors.45

Transportation

Patients with cancer may be limited in their ability to drive, fly, or take public transportation. They may not have caregivers available to help transport them. Lack of transportation can become a major barrier to cancer treatment, which often involves frequent medical visits. Some patients forgo recommended treatments because of lack of adequate transportation. Thus it behooves physicians to explore with patients any limits to their ability to get transportation. Galski and colleagues46 showed that patients receiving chronic, stable, opioid analgesic therapy can drive safely. Patients with cerebral dysfunction as a result of a tumor, paraneoplastic effects, or treatment adverse effects should be evaluated for their ability to drive safely before they are allowed to return to the road. Well-defined off-road driver evaluation tools are available.