CHAPTER 125 Pineal Tumors

Historical Perspective

Although pineal tumors were first described in 1717, the earliest attempts at surgery in the pineal region did not occur until 200 years later.1 Those initial attempts were led by pioneers such as Horsley, Brummer, and Schloffer, whose boldness in the setting of primitive neurosurgical technique predictably did not produce favorable outcomes.2 Oppenheim and Krause reported the first successful removal of a tumor from the pineal region in 1913.3 In 1921, Dandy described the transcallosal approach that he used in three patients with pineal tumors after his scholarly development of the technique in dogs.4 In 1926, Krause reported modest success without operative mortality in three patients with the infratentorial approach.5 These achievements are testament to the skill and innovation of these remarkable individuals whose work was hampered by the lack of microscopes, lighting, instrumentation, and modern anesthesia.

This modest success provoked interest in approaches to the pineal region; however, the difficulty of operating on these deep-seated lesions was apparent from the unacceptably high surgical mortality and morbidity. A more conservative approach was adopted whereby patients had shunts placed to relieve hydrocephalus and received empirical radiation therapy.6–13 Surgery was considered only for patients who failed to respond to radiation treatment. This algorithm was especially favored in Japan, where a high preponderance of radiosensitive germinomas are found.14–17 Unfortunately, this strategy of “blind radiation” led to unnecessary and potentially harmful radiation exposure in a large percentage of patients with benign and radiation-resistant tumors.18–20 Eventually, clinical management of these patients became more sophisticated and led to an appreciation of the need for individualized therapy based on specific tumor histology.21–32 This philosophic shift coincided with improvements in neuroanesthetic and microsurgical techniques and spurred development of the modern operative approaches. In 1971, Stein ushered in the microsurgical era for pineal region surgery with his successful modification of Krause’s infratentorial approach.31 Subsequently, additional supratentorial approaches have been reevaluated and added to the neurosurgeon’s armamentarium.21,33–38

Safe and effective surgical strategies are essential for current clinical management of pineal tumors because securing a histologic diagnosis is fundamental to decision making.25,27,28,39–44 Distinguishing among the many diverse histologic subtypes that can occur in the pineal region has important implications for planning adjuvant therapy regimens, making prognostic determinations, and establishing follow-up strategies.

Anatomy

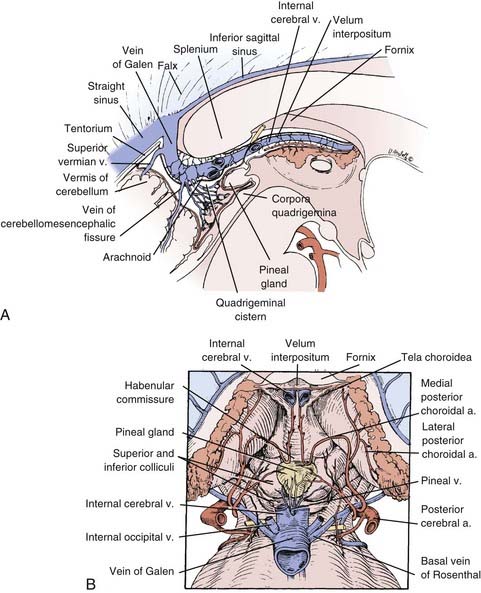

The pineal gland is an encapsulated structure that occupies a deep position near the geometric center of the brain. The pineal gland is essentially an extra-axial structure, a feature that makes tumors of the pineal gland readily resectable because a surgical plane can often be established between adjacent structures. Surrounding structures include the posterior commissure ventrally, the corpus callosum superiorly, and the habenular commissure dorsally (Fig. 125-1).45 The velum interpositum, which incorporates the internal cerebral veins and the choroid plexus, is intimate with the dorsal gland. The basal veins of Rosenthal combine with the internal cerebral veins to form the vein of Galen before draining into the straight sinus. The blood supply to the pineal gland is from branches of the medial and lateral choroidal arteries through anastomoses to the pericallosal, posterior cerebral, superior cerebellar, and quadrigeminal arteries.46,47

FIGURE 125-1 Sagittal (A) and dorsal (B) drawings of pineal region anatomy.

(From McComb J, Levy M, Apuzzo M. The posterior intrahemispheric retrocallosal and transcallosal approaches to the third ventricle region. In: Apuzzo M, ed. Surgery of the Third Ventricle. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:743-777.)

Pathology

The different cell types that make up the pineal gland account for the diverse pathology of pineal region tumors. The mature pineal gland is made up of pinealocytes arranged in lobules to form the pineal parenchyma.45 The pinealocytes are surrounded by astrocytes, with endothelial cells forming the vasculature and connective tissue cells forming septa between the lobules. The gland also contains nerve endings from sympathetic nervous innervation to the pinealocytes. The ependymal cells of the third ventricle adjoin the gland along its anterior border.

The term pinealoma was originally used by Krabbe but is a misnomer because it initially pertained to germ cell tumors.48 Eventually, this term was applied more generically to any tumor of the pineal region, but it is now obsolete. Pineal region tumor is the preferred general term; the individual tumor’s histology is used for specificity (e.g., astrocytoma of the pineal region).49

Pineal tumors are grouped into four main categories: germ cell tumors, pineal parenchymal cell tumors, glial cell tumors, and other miscellaneous tumors and cysts.21 Within each category, tumors exist along a continuum from benign to malignant; mixed tumors of more than one cell type also occur.42,50,51

The miscellaneous category includes such entities as meningioma, hemangioblastoma, choroid plexus papilloma, metastatic tumor, chemodectoma, adenocarcinoma, and lymphoma.21,29,52,53 Additionally, a variety of vascular lesions can occur, including cavernous malformations, arteriovenous malformations, and vein of Galen malformations.43,54

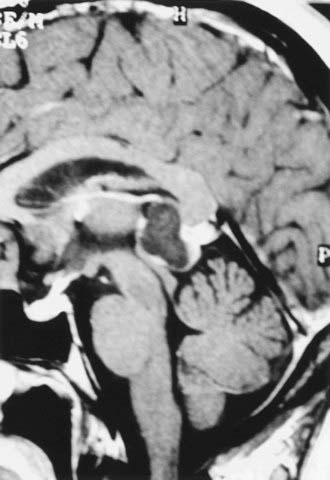

Benign pineal cysts are being encountered with greater frequency as the indications for radiographic imaging expand (Fig. 125-2).55,56 Histologically, these cysts are benign, normal variants of the pineal gland and consist of cystic structures surrounded by normal pineal parenchymal tissue. They can be up to 2 cm in diameter, with a contrast-enhancing rim representing compressed pineal gland tissue. They are nearly always asymptomatic and generally do not require treatment unless they are causing aqueductal obstruction. Radiographically, pineal cysts can mimic pilocytic astrocytomas, although tumors can be distinguished by their increased tendency to be progressive and symptomatic. The natural history of pineal cysts is that of a static anatomic variant that does not require treatment.

Clinical Features

Initial Symptoms

Pineal region tumors are generally manifested in one of three ways21,56: (1) symptoms of increased intracranial pressure from obstructive hydrocephalus, (2) direct brainstem and cerebellar compression, or (3) endocrine dysfunction.

The most common initial symptom is headache, which is associated with obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to compression of the aqueduct of Sylvius. Further progression of hydrocephalus can lead to nausea, vomiting, obtundation, cognitive impairment, papilledema, and ataxia. In rare cases, symptoms can develop abruptly in association with pineal apoplexy from hemorrhage in a pineal tumor.57–60

Direct compression of the midbrain, particularly at the level of the superior colliculus, can cause disorders of extraocular movement, classically known as Parinaud’s syndrome.61,62 This syndrome can consist of paralysis of upgaze, convergence or retraction nystagmus, and light-near pupillary dissociation. The sylvian aqueduct syndrome, which consists of paralysis of downgaze or horizontal gaze from further midbrain compression, can be superimposed on Parinaud’s syndrome.63 Dorsal midbrain compression or infiltration can lead to lid retraction (Collier’s sign) or ptosis. Less commonly, fourth nerve palsies with diplopia and head tilt may occur. Although eye signs can be due to either hydrocephalus or direct brain compression, symptoms from hydrocephalus generally recede after a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion procedure. Interference with the cerebellar efferent pathways of the superior cerebellar peduncles can cause ataxia and dysmetria. Rare cases of hearing dysfunction have been reported, probably caused by a disturbance in structures associated with the inferior colliculi.64,65

Endocrine dysfunction is rarely encountered but usually arises from the secondary effects of hydrocephalus or from spread of tumor to the hypothalamic region.66 Diabetes insipidus can occur with a germinoma spreading along the floor of the third ventricle. Such symptoms may develop early in the disease process, even before the tumor is radiographically apparent. Precocious puberty has been linked historically with pineal masses; however, documented cases are rare.48,66,67 This syndrome is actually precocious pseudopuberty because the hypothalamic-gonadal axis is not mature, and it is therefore limited to boys whose choriocarcinoma or germinoma contains syncytiotrophoblastic cells producing ectopic secretion of β-human chorionic gonadotropin.66,68

Diagnosis

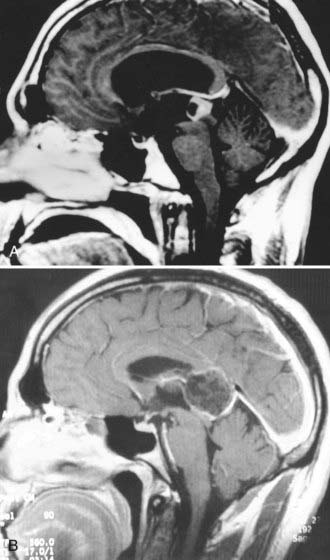

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement is the principal diagnostic test for pineal tumors.49,69–71 MRI reveals the degree of hydrocephalus and allows evaluation of tumor size, vascularity, homogeneity, and anatomic relationships with surrounding structures. In planning the operative approach, knowledge of the relevant anatomic relationships is useful, including the position of the tumor within the third ventricle, the amount of lateral and supratentorial extension, and the degree of brainstem involvement. The extent of tumor invasiveness can be estimated from the margination and irregularities of the tumor border; however, the true degree of tumor encapsulation can be defined only at surgery.42

Pineal tumors generally displace the vessels of the deep venous system superiorly along the dorsal periphery of the tumor. This is an important point when planning surgical approaches because most tumors can be separated from the surrounding veins and midbrain (Fig. 125-3).42 Notable exceptions are meningiomas arising from the velum interpositum and epidermoid or other tumors originating in the corpus callosum. These tumors displace the deep venous system ventrally and inferiorly, thereby providing a diagnostic clue on MRI. The position of the tumor relative to the deep venous system is important because it may influence the choice between an infratentorial and a supratentorial approach. Although the location of the deep venous system may be conspicuous on MRI, magnetic resonance venography may be desirable to better delineate it.

Despite advances in high-resolution MRI, tumor histology cannot be reliably predicted on the basis of imaging features alone.21,69,70,72,73 Computed tomography can complement MRI by providing details of calcification, blood-brain barrier breakdown, and the degree of vascularity.74 Angiography is not necessary unless a vascular anomaly is suspected.

Tumor Markers

The presence of α-fetoprotein or β-human chorionic gonadotropin, measured in either serum or CSF, is pathognomonic for malignant germ cell elements (Table 125-1).47,56,75 CSF levels tend to be more sensitive than serum levels.51,56,75 α-Fetoprotein indicates the presence of fetal yolk sac elements, and levels are markedly elevated with endodermal sinus tumors; smaller elevations are seen with some embryonal cell carcinomas and immature teratomas.56,68,75–79 β-Human chorionic gonadotropin is produced by trophoblastic elements; high levels are found with choriocarcinomas, whereas low levels can be associated with some, but not all embryonal cell carcinomas and germinomas.49,56,68,75,76,78,80–83 Although the presence of germ cell markers indicates a malignant germ cell tumor, the converse is not necessarily true. That is, the absence of germ cell markers should be interpreted cautiously because it does not rule out the presence of a germinoma or embryonal cell carcinoma. Similarly, if α-fetoprotein is elevated in the presence of a germinoma, it is likely that an embryonal cell carcinoma or endodermal sinus tumor is present as part of a mixed tumor.84

| TUMOR | β-HUMAN CHORIONIC GONADOTROPIN | α-FETOPROTEIN |

|---|---|---|

| Benign germ cell | − | − |

| Immature teratoma | ? | +/− |

| Germinoma | − | − |

| Germinoma with syncytiotrophoblastic cells | + | − |

| Embryonal cell carcinoma | +/− | +/− |

| Choriocarcinoma | ++ | − |

| Endodermal sinus tumor | − | ++ |

Tumor markers are useful for monitoring response to adjuvant therapy or as an early sign of recurrence. Because they are reliable indicators of malignant germ cell elements, the presence of malignant germ cell markers makes surgery and biopsy unnecessary, and such patients should be managed with radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Other biologic markers for germ cell tumors include lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes and placental alkaline phosphatase.56,85,86 These germ cell markers have diagnostic value when used for the immunohistochemical analysis of histologic specimens but are not useful as serum or CSF markers.

Markers such as melatonin and S-antigen have been investigated in patients with pineal parenchymal cell tumors.45,87–90 These markers also have more applicability in immunohistochemical diagnosis. Analysis of melatonin levels in postoperative patients has been investigated but has little clinical applicability.

Treatment

Management of Hydrocephalus

Most patients are initially seen with obstructive hydrocephalus, which can be managed in several ways. Symptomatic patients are best managed initially with a stereotactic-guided endoscopic third ventriculostomy to allow gradual reduction of intracranial pressure and resolution of symptoms before tumor resection.91 This method is preferable to ventriculoperitoneal shunting because it eliminates potential complications such as infection, overshunting, and peritoneal seeding of malignant cells. Mildly symptomatic patients in whom gross total resection is anticipated at surgery can be managed with a ventricular drain placed at the time of surgical resection.25,92 The drain can be removed or converted to a shunt in the postoperative period as circumstances dictate.

Tissue Diagnosis: Biopsy versus Open Resection

Given the diverse pathology that can occur in the pineal region, a histologic diagnosis is necessary to optimize management decisions.42,44,92–95 An individual tumor’s histology strongly influences the choice of postoperative adjuvant therapy, need for metastatic work-up, estimation of prognosis, and planning of long-term follow-up. Although CSF cytology and radiographic examination provide insight into the histologic diagnosis, they are not sufficiently sensitive to supplant a tissue diagnosis.72,96–101 CSF cytology occasionally reveals malignant cells but is rarely diagnostic. The only time that a tissue diagnosis is unnecessary is in the presence of malignant germ cell markers; in these cases, chemotherapy and radiation therapy should proceed without a biopsy.92,100,102

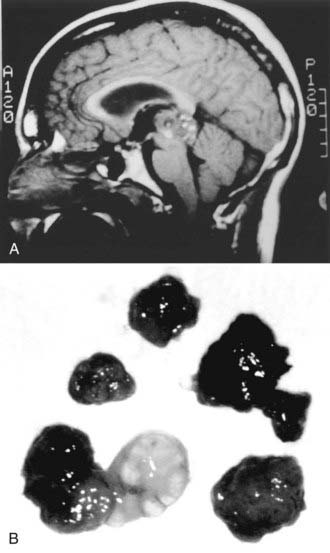

Tissue diagnosis can be achieved by either stereotactic biopsy or an open procedure. This decision is influenced by the clinical features of the patient, radiographic features of the tumor, and the surgeon’s degree of experience with the procedures. Inflexible or dogmatic dedication to either procedure is not appropriate. In general, patients with known primary systemic tumors, multiple lesions, or medical conditions that make open resection dangerous are good candidates for stereotactic biopsy.49,92 Radiographic evidence of brainstem invasion might make stereotactic biopsy an attractive choice; however, the degree of invasion seen radiographically can be misleading and may not reflect a dissectible tumor capsule at surgery. The advantage of open resection is the ability to obtain larger amounts of tissue and more extensive tissue sampling. This is particularly important for pineal region lesions in general and germ cell tumors in particular because heterogeneity and mixed cell populations are common. This diversity makes it difficult for neuropathologists to appreciate the subtleties of histologic diagnosis when only small specimens are available (Fig. 125-4; Table 125-2).25,92,103–105

TABLE 125-2 Pure versus Mixed Germ Cell Tumors at the New York Neurological Institute (1978-2000)

| TUMOR TYPE | NUMBER |

|---|---|

| Pure Germ Cell Tumors | |

| Germinoma | 30 |

| Teratoma | 9 |

| Epidermoid | 3 |

| Immature teratoma | 2 |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 2 |

| Lipoma | 2 |

| Total | 48 |

| Mixed Germ Cell Tumors | |

| Germinoma/teratoma | 4 |

| Germinoma/embryonal carcinoma | 3 |

| Immature teratoma/germinoma/EST | 2 |

| Germinoma/dermoid | 1 |

| Germinoma/immature teratoma | 1 |

| Choriocarcinoma/teratoma | 1 |

| Choriocarcinoma/immature teratoma | 1 |

| Embryonal carcinoma/EST | 1 |

| EST/embryonal carcinoma/germinoma | 1 |

| Nonspecified mixed | 2 |

| Total | 17 |

EST, endodermal sinus tumor.

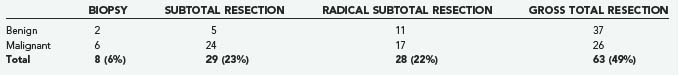

Additionally, a clinical advantage is gained when the tumor burden is reduced with an open procedure. For the third of tumors that are benign, resection is usually complete and curative, thus making it the clear procedure of choice (Table 125-3).42,92,106 The advantages of tumor debulking are less apparent with malignant tumors; however, anecdotal evidence favors more radical resection, when possible, to improve the response to adjuvant therapy.34,92,106–108 Additionally, for certain patients with mild hydrocephalus whose tumors can be completely resected, shunting can be avoided.25,92

TABLE 125-3 Extent of Resection for 128 Consecutive Pineal Region Surgeries at the New York Neurological Institute (1990-2008)

Stereotactic biopsy offers the advantages of relative ease of performance and reduced complications when compared with an open procedure.24,29,109–111 Usually, only local anesthesia is necessary. However, stereotactic biopsy carries a risk for hemorrhage from several mechanisms, including bleeding in highly vascular tumors, damage to the deep venous system, and bleeding into the ventricle, where tissue turgor is insufficient to tamponade minor bleeding.25,92,103,110,112 These risks notwithstanding, several large series have validated the relative safety of stereotactic biopsy for these tumors despite their rather hazardous location.24,109 Of minor concern but worth mentioning is a report of metastatic seeding along the biopsy tract after biopsy of a pineoblastoma.113

Surgical Techniques

Stereotactic Procedures

Most target-centered stereotactic frame systems are adequate for biopsy. Computed tomography is sufficient to provide accurate targeting information and to track the trajectory in three dimensions. MRI provides more sensitive soft tissue visualization, and current software has minimized any spatial inaccuracy. Volumetric treatment planning should be used to identify the trajectory in all the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. Two possible approaches are favored for stereotactic surgical trajectories.24,29,56,114 The most common is through a precoronal entry point, with the tumor being reached through an anterolaterosuperior approach that avoids the interior surface of the lateral ventricle and comes inferior and lateral to the internal cerebral veins to reduce the risk for bleeding. The alternative approach is through a posterolaterosuperior approach near the parieto-occipital junction, which can be useful for tumors that extend laterally or superiorly.

Serial biopsies are desirable whenever possible; however, this is often prohibited by the small size of the tumors commonly encountered.24,109 The side-cutting cannula type of biopsy needle is preferred over a cup forceps instrument, which can tear a blood vessel. If bleeding is encountered, continuous suction and irrigation for up to 15 minutes may be necessary. When bleeding is suspected, an immediate scan should be obtained to assess for intraventricular blood and the degree of hydrocephalus to determine the need for ventricular drainage.

Endoscopic Biopsy

Endoscopic biopsy of pineal tumors through the ventricles has been reported as an alternative method for securing a tissue diagnosis.115–119 In addition to sampling error, a major drawback of this procedure is that the tumor is biopsied along its ventricular surface, where there is no tissue turgor to tamponade the bleeding. Even minor bleeding within the CSF space can be difficult to manage, a problem that is compounded by the highly vascular properties of many pineal tumors. Typically, this procedure is combined with a ventriculostomy. However, even with flexible endoscopes, it is difficult to perform a biopsy simultaneously with a ventriculostomy because the trajectory required is different for each procedure. The rigid endoscope is not easily maneuverable without risk of damage to the fornix and the septal and thalamostriate veins at the foramen of Monro. A suitable entry point through the forehead might allow the use of a rigid scope, but this offers no advantage over a simple stereotactic biopsy. More typically, endoscopes have been used to aspirate pineal cysts; however, the benefits of this approach are equivocal.

Operative Procedures

Several variations on approaches to the pineal region exist, but essentially they are categorized as supratentorial or infratentorial.36,42,92 Supratentorial approaches include transcallosal interhemispheric, occipital transtentorial, and the rarely used transcortical transventricular.13,34,92,120 The infratentorial approach is through a natural corridor created between the tentorium and the cerebellum.31,121 The choice of approach depends on the surgeon’s experience and comfort with the specific technique. Many of these approaches are interchangeable, although there are several caveats. Large tumors that extend supratentorially or laterally to the trigone of the lateral ventricle generally benefit from a supratentorial approach.92 Supratentorial approaches afford greater exposure than infratentorial approaches do, but they have the disadvantage of forcing the surgeon to work around the convergence of the vein of Galen and internal cerebral veins, where they interfere with tumor removal.

The location of most pineal tumors infratentorially and in the midline gives the infratentorial supracerebellar approach several natural advantages.92,122 It is performed with the patient in the sitting position, whereby gravity allows the cerebellum and the tumor to drop downward. The tumor can then be dissected more easily off the deep venous system and velum interpositum, which is often the most technically difficult portion of tumor dissection. Besides the obvious anatomic advantage of using a midline trajectory, the deep venous system lies dorsal to the mass, thus making it more avoidable through most of the tumor dissection. The approach is less favorable if the tumor has a significant supratentorial or lateral extension, although with appropriate extra-long instruments, even tumors extending anteriorly into the third ventricle can be removed.

Patient Positioning

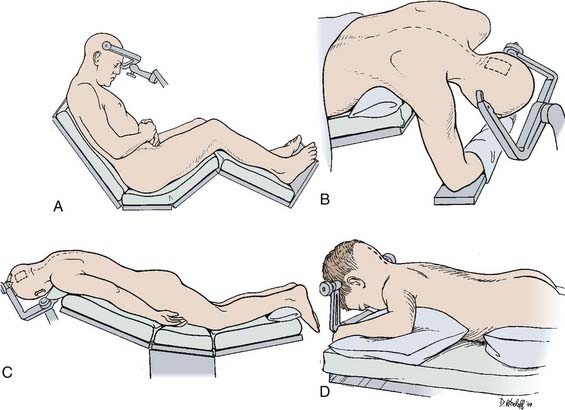

Numerous patient positions have been described for these approaches, each having advantages and disadvantages (Fig. 125-5).

Sitting Position

The sitting position is usually preferred for the infratentorial supracerebellar approach (see Fig. 125-5A).92,122 Gravity works in the surgeon’s favor by reducing pooling of blood in the operative field and by facilitating dissection of the tumor from the deep venous system. The risks for air embolism, pneumocephalus, or subdural hematoma associated with cortical collapse can be anticipated and managed with proper precautions.92,123 Doppler monitoring helps detect small amounts of air entering the venous system during the operative procedure. A central venous catheter can be used to remove entrapped air if necessary.

Lateral Position

The lateral decubitus position with the dependent, nondominant right hemisphere down is generally used.124 The head is raised approximately 30 degrees above the horizontal in the midsagittal plane, especially for the transcallosal approach. For the occipital transtentorial approach, the head should be positioned with the patient’s nose rotated 30 degrees toward the floor.

A more desirable variation of this approach is the three-quarter prone position (Fig. 125-5B).125 The legs are flexed with a pillow between them, and the patient is strapped down so that the table can be rotated during the procedure to improve exposure when appropriate. The three-quarter prone position is essentially an extension of the lateral position, except that the head is at an oblique 45-degree angle with the nondominant hemisphere dependent. This is suitable for more posterior approaches, such as the occipital transtentorial as opposed to the transcallosal approach. The nondominant hemisphere is easily retracted with the help of gravity. Surgeon fatigue is reduced because the surgeon’s hands are on a horizontal plane and are not extended to the degree they are with patients in the sitting position. The three-quarter prone position can be cumbersome and requires placing an axillary roll under the patient’s right axilla with the right arm supported in a sling-like fashion beneath the patient. A supporting roll is placed under the left thorax, and a three-point head-pin vise holder is used to support the head in a slightly extended and rotated position to the left at a 45-degree oblique angle. The patient is securely strapped, and the legs and feet are elevated to facilitate venous return.

Prone Position

The prone position is simple and safe for supratentorial approaches (Fig. 125-5C).92,120 It is generally comfortable for the surgeon, although the operative field is considerably raised, which makes it difficult for the surgeon to be seated. This position is useful when two surgeons work together through an operative microscope that has a bridge to allow simultaneous binocular vision. The steep angle of the tentorium, however, makes the prone position impractical for the infratentorial approach. This position is often useful in the pediatric population. To facilitate its use, the position of the head can be rotated 15 degrees away from the craniotomy side in a variation known as the Concorde position (Fig. 125-5D).126

Operative Approaches

Infratentorial Supracerebellar Approach

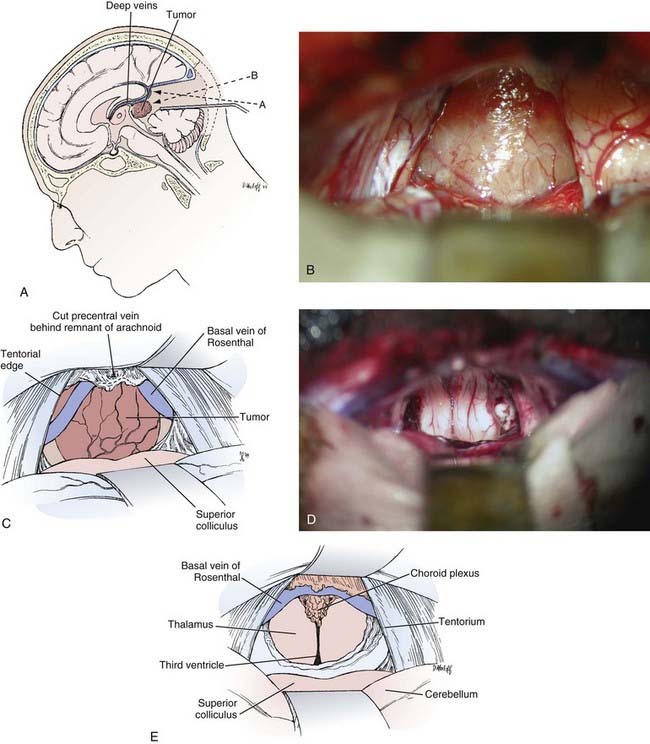

![]() The infratentorial supracerebellar approach was first described by Krause at the beginning of the 20th century (Fig. 125-6, Video 125-1).5 The technique was lost for many years because of limitations in microsurgical technique until its rediscovery in 1971 by Stein.31

The infratentorial supracerebellar approach was first described by Krause at the beginning of the 20th century (Fig. 125-6, Video 125-1).5 The technique was lost for many years because of limitations in microsurgical technique until its rediscovery in 1971 by Stein.31

The infratentorial supracerebellar approach is usually performed with the patient in the sitting position.42,92,122 If necessary, a ventricular drain can be placed in the trigone of the lateral ventricle through a bur hole in the midpupillary line at the lambdoid suture. A suboccipital exposure is begun through a linear midline incision extending from just above the torcular and external occipital protuberance down to the level of the C4 spinous process. The incision is brought through the nuchal ligament of the suboccipital musculature. It is not necessary to detach the muscles from the spinous processes of C1 and C2, and the foramen magnum does not need to be exposed. A single low-profile, self-retaining retractor is used to retract the muscles and fascia of the suboccipital region for exposure of the suboccipital bone. The craniotomy is centered just below the torcular. The bony opening must be sufficient to provide access for the surgical instruments and adequate light from the operating microscope. A craniotomy is preferred over a craniectomy because it reduces the incidence of postoperative aseptic meningitis, fluid collections, and discomfort. Slots are drilled over the sagittal sinus, above the torcular, and over both lateral sinuses. A final slot is drilled approximately 1 or 2 cm above the foramen magnum in the midline. A craniotome is used to connect the slots, which allows the bone flap to be elevated. Sufficient bone should be removed above the transverse sinus to ensure that the view along the tentorium is not obscured. Any bone edges should be carefully waxed, and all venous bleeding should be controlled to avoid air emboli.

To open the infratentorial corridor, the arachnoidal adhesions and midline bridging veins between the dorsal surface of the cerebellum and the tentorium are cauterized and carefully divided. The presence of extensive collateral circulation minimizes complications from venous sacrifice; however, to minimize risk, it is desirable to preserve any veins found laterally.127 Cauterizing the bridging veins and dividing them midway can minimize the nuisance of bleeding from the sinus. When these attachments are divided, the cerebellum drops away from the tentorium to provide an excellent corridor with minimal brain retraction. The dorsal surface of the cerebellum can be protected with padding such as Telfa, and a small brain retractor can be used to provide additional cerebellar retraction in a posterior and inferior direction. Additional adhesions and bridging veins can be divided when they become visible near the anterior vermis as the cerebellum is retracted. With the retractor in place, the opalescent arachnoid covering the pineal region can be seen.

Under the microscope, the arachnoid overlying the quadrigeminal plate is sharply opened. This is generally an avascular plane, and minimal cautery is necessary. The precentral cerebellar vein is identified as it courses from the anterior vermis to the vein of Galen and should be carefully dissected, cauterized, and divided. Although this vein can be taken without difficulty, it is not advisable to cauterize any other veins of the deep venous system. The retractor can then be adjusted to visualize the inferior portion of the tumor. The trajectory of the microscope is adjusted downward along the central axis of the tumor away from the initial plane parallel to the tentorium, where it would otherwise lead to direct encounter with the vein of Galen (see Fig. 125-6A).

With the posterior surface of the tumor exposed, the central portion is cauterized and opened with a long-handled knife or bayonet scissors (Fig. 125-6B and C). Specimens can be taken from within the capsule and sent for frozen diagnosis. The accuracy of frozen tissue diagnosis is low, however, and this should be taken into consideration during intraoperative decision making. The tumor is then internally debulked with a variety of instruments such as suction, cautery, tumor forceps, and a Cavitron ultrasonic aspirator if necessary. Most tumors are soft and can generally be suctioned with a large-bore Japanese-style suction device with variable control. As the tumor is decompressed, the capsule can be separated from the surrounding thalamus. Most of the vessels along the wall of the capsule are choroidal vessels and need not be preserved. The dissection continues until the third ventricle is encountered. The tumor is then carefully dissected inferiorly off the brainstem. This is often the most difficult portion of the tumor dissection and can be facilitated by retracting the tumor superiorly and dissecting it bluntly off the brainstem under direct vision. Finally, the tumor is removed superiorly after separating the attachments along the velum interpositum and the deep venous system. These attachments can be carefully cauterized and sharply dissected, although a rent in the deep venous system can be difficult to control and must be avoided.

Once tumor removal is completed, the surgeon should have a comprehensive view into the third ventricle (Fig. 125-6D and E). Flexible mirrors can be useful for examining the inferior portion of the tumor bed to verify the extent of resection and to avoid leaving any blood clots. Careful attention must be given to hemostasis.92,128 Generally, direct but careful cautery is preferable. It is advisable to avoid extensive use of hemostatic agents, which can float into the ventricle and obstruct a shunt or the aqueduct. If absolutely necessary, long strips of Surgicel draped over the surface of the cerebellum and covering the tumor bed can provide hemostasis with small risk of floating into the ventricle.

Transcallosal Interhemispheric Approach

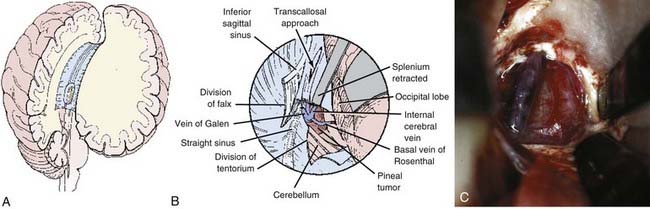

The transcallosal interhemispheric approach was first described by Dandy (Fig. 125-7).8,44 This approach between the falx and hemisphere of the brain involves a corridor along the parieto-occipital junction. Dandy’s early contributions recognized the importance of the deep venous system and the cortical bridging veins between the hemisphere and the sinus. Any of the previously described patient positions can be used for this approach, although the prone or sitting position is generally preferred.

Positioning of the bone flap depends on where the tumor is centered in the third ventricle.120,129,130 A wide craniotomy roughly 8 cm in length provides flexibility in determining the corridor and avoiding bridging veins whenever possible. The craniotomy is generally centered over the vertex to avoid manipulation of the occipital lobe. A U-shaped scalp flap extending across the midline and reflected laterally provides adequate exposure. A bur hole is made over the sagittal sinus, both anteriorly and posteriorly, and a craniotome is used to turn a generous craniotomy. The craniotomy should extend 1 to 2 cm to the left of the sagittal sinus. Bleeding from the sagittal sinus can be controlled with hemostatic agents.

The corpus callosum is easily identified with the operating microscope by its striking white appearance. The pericallosal arteries are identified as a paired structure running over the corpus callosum. These arteries are retracted either to one side or with separate retractors to each side. The opening into the corpus callosum, centered over the maximal bulge of the tumor, is generally about 2 cm, which is not likely to lead to disconnection syndrome or cognitive impairment (see Fig. 125-7A). Even more posterior openings in the splenium have been performed routinely without deficits. The corpus callosum is generally thin and can be opened with gentle suction and cautery. The lateral extent of the opening is determined by the amount that is sufficient to expose the tumor and avoid damage to the pericallosal arteries. If necessary, the tentorium and falx can be divided to provide additional exposure (Fig. 125-7B).

Once through the corpus callosum, the dorsal surface of the tumor can be seen, and the veins of the deep venous system must be identified early to prevent damage to them (Fig. 125-7C). The importance of the deep venous system and the degree of venous collaterals is a topic of anecdotal speculation. Obviously, sacrificing any vein is undesirable. Whether one vein can be sacrificed safely is questionable, but certainly interruption of two would have a devastating result.

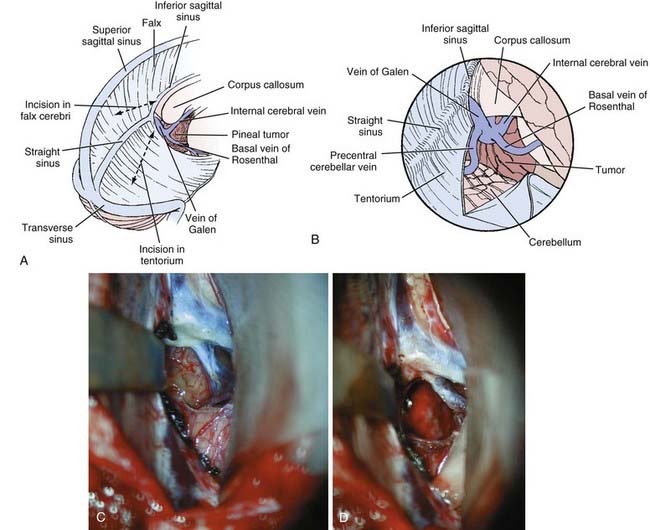

Occipital Transtentorial Approach

![]() The occipital transtentorial approach, originally described by Horrax and later modified by Poppen, is a variation of the supratentorial approaches (Fig. 125-8, Video 125-2).35,131 A three-quarter prone position is generally preferred. This approach to the pineal region uses an oblique trajectory for lesions that are essentially midline and may therefore be disorienting to surgeons who are not familiar with it. However, by dividing the tentorium, excellent exposure of the quadrigeminal plate is achieved, thus making it particularly useful for tumors that extend inferiorly.

The occipital transtentorial approach, originally described by Horrax and later modified by Poppen, is a variation of the supratentorial approaches (Fig. 125-8, Video 125-2).35,131 A three-quarter prone position is generally preferred. This approach to the pineal region uses an oblique trajectory for lesions that are essentially midline and may therefore be disorienting to surgeons who are not familiar with it. However, by dividing the tentorium, excellent exposure of the quadrigeminal plate is achieved, thus making it particularly useful for tumors that extend inferiorly.

A U-shaped right occipital scalp flap is reflected inferiorly, with the medial vertical limb beginning just to the left of midline at about the level of the torcular.34,129 A bur hole is placed in the midline over the sagittal sinus just above the torcular, along with another bur hole 6 to 10 cm above this. A craniotome is then used to turn a generous craniotomy extending 1 to 2 cm left of midline. Alternatively, it is feasible to place the bur holes adjacent to the sagittal sinus without crossing the midline. If this option is chosen, it is important to get as close as possible to the sagittal sinus to avoid a bony overhang that limits the operative view.

Under the operating microscope, the straight sinus is identified so that the tentorium can be divided adjacent to it (Fig. 125-8A). A retractor can be placed over the falx for exposure. The inferior sagittal sinus and falx can be divided to facilitate further falcine retraction. At this point, the arachnoid overlying the tumor and the quadrigeminal cisterns can be seen (Fig. 125-8B). Tumor removal proceeds as described earlier while taking care to avoid injury to the deep venous system. Closure and hemostasis proceed as described previously.

Transcortical Transventricular Approach

The transcortical transventricular approach was developed by Van Wagenen, who used a trajectory through the right lateral ventricle via a transcortical incision.13 This approach is rarely used because the exposure is limited and the need for a cortical incision is undesirable. Obviously, an entry point should be chosen in noneloquent cortex. Stereotactic guidance is often useful with this approach and may be desirable for a tumor that extends into the lateral ventricle.

Postoperative Care

High-dose steroids should be maintained for the first few days and then tapered as the patient’s condition improves.128,129 Lethargy and mild cognitive impairment are common and make it difficult to evaluate neurological status in the immediate postoperative period, particularly in patients with extensive subdural air as a result of the sitting position. Careful and frequent neurological examinations are necessary, and any changes should be investigated by computed tomography to rule out the possibility of hydrocephalus, hemorrhage, or residual air. Shunt malfunction is a frequent immediate problem caused by air, blood, or operative debris; it is particularly worrisome because deterioration and major morbidity can occur rapidly.

Complications

Patients frequently have some impairment in extraocular movements in the immediate postoperative period, particularly limited upgaze and convergence.38,106,128 Some degree of pupillary impairment with difficulty focusing may also occur. Many of these extraocular problems are transient and resolve within the first few days, although they can persist for several months. Permanent major impairment is rare, but some mild limitation of upgaze is not unusual and has little clinical significance. As with most neurological deficits, their persistence and magnitude are proportional to the degree to which they were present preoperatively.128,132 Similarly, ataxia is frequently present but resolves within a few days after surgery.

More severe morbidity is rare but can be a sequela of overzealous brainstem manipulation. This can lead to cognitive impairment or, in its extreme form, even to akinetic mutism. Complications are more common in previously irradiated patients, patients with invasive tumors, and those who were progressively symptomatic preoperatively.128,132

One of the most devastating complications is hemorrhage into an incompletely resected tumor bed. Patients with highly vascular, invasive tumors such as malignant pineal parenchymal tumors are at greatest risk for this complication.24,58,112,128 Small hemorrhages can be managed conservatively, but a large hemorrhage may require immediate evacuation. Such decisions must consider the possibility of obstructive hydrocephalus.

Complications of supratentorial approaches include hemiparesis from brain retraction or from sacrifice of bridging veins.123,128,133 Fortunately, these deficits usually resolve spontaneously, and infarction and permanent deficits are rare. Seizure prophylaxis is desirable in the immediate postoperative period, although long-term use is not necessary. Parietal lobe retraction can cause sensory or stereognostic deficits on the opposite side.129 Occipital lobe retraction during the transtentorial approach can cause visual field defects.34,129,134 Although disconnection syndromes have been reported with corpus callosum incisions, this has been rare in our experience, even when the splenium is divided.120,129

Complications related to the sitting position include subdural hematoma, hygroma, and ventricular collapse.42,106,123 These conditions are generally self-limited. Air embolism is rarely a problem but can be anticipated by a drop in end-tidal carbon dioxide levels or with Doppler monitoring.

Surgical Outcome

Surgery in the pineal region is among the most arduous of microsurgical challenges, and outcomes vary substantially with the expertise of individual surgeons. With modern microsurgical techniques, surgical series that include more than 20 patients report operative mortality in 0% to 8% and permanent morbidity in 0% to 12% of patients (Table 125-4).25,44,92,106,135 The impact of surgery on long-term outcome depends on the tumor’s histology and responsiveness to adjuvant therapy. With benign tumors, such as teratomas, cystic pilocytic astrocytomas, dermoid tumors, epidermoid tumors, and low-grade pineocytomas, expectations include complete surgical removal, excellent long-term follow-up, and probable cure.42,92,121,136–138

TABLE 125-4 Results of Pineal Region Surgery at the New York Neurological Institute (1990-2008)

| Total Procedures | 128 |

| Benign pathology | 55 (43%) |

| Malignant pathology | 73 (57%) |

| Diagnosis established | 127 (99%) |

| Surgical Morbidity | |

| Death (pulmonary embolism/cerebellar infarct) | 2 (2%) |

| Permanent major morbidity | 1 (1%) |

| Transient major morbidity (with recovery) | 7 (5%) |

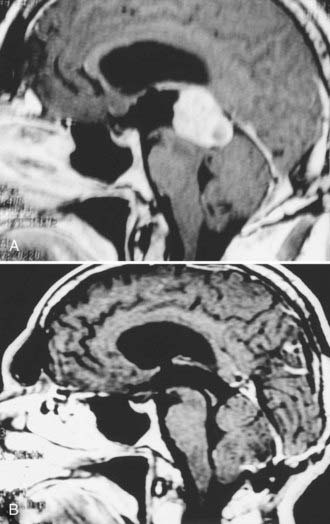

With malignant tumors, the paucity of surgical series reported in the literature makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the effect of the degree of resection on outcome. The anecdotal evidence, however, is that except for germinomas, greater resection improves the prognosis and response to adjuvant therapy.42,51,92,107,132 A small subset of pineocytomas, representing approximately 16% of all pineal cell tumors, are discrete, encapsulated, histologically benign. and fully resectable (Fig. 125-9).8,92,112,134,136,137 Surgery alone may lead to long-term recurrence-free periods without any additional therapy. Such patients, however, should be monitored closely with serial MRI.

Postoperative Work-Up

Postoperative MRI with gadolinium enhancement should be performed within 72 hours of surgery to determine the completeness of resection.21 Tumor markers, if present preoperatively, should be measured in the postoperative period to serve as a baseline for detecting early recurrence or for monitoring response to treatment.

Spinal MRI to look for spinal seeding is required for patients with pineal cell tumors, malignant germ cell tumors, and ependymomas (Fig. 125-10).21,92,139,140 MRI of the spine can be difficult to interpret in the immediate postoperative period because blood clots or operative debris can sometimes mimic spinal metastasis. If the images are equivocal, serial images should be obtained before instituting spinal irradiation. CSF cytology should be evaluated by lumbar puncture postoperatively, although this has not been particularly helpful in predicting the metastatic potential of these tumors.9,17,78,92,141,142 Overall, the incidence of spinal seeding is low, and prophylactic spinal irradiation is not recommended unless there is clear radiographic evidence of metastasis.25,39,68,92,101,143–146 The one possible exception is in patients with highly malignant pineoblastomas.92,106,147

Adjuvant Therapy

Radiation Therapy

Patients with malignant germ cell or pineal cell tumors require radiation therapy. The recommended radiation dose is 5500 cGy given in 180-cGy daily fractions, with 4000 cGy to the ventricular system and an additional 1500 cGy to the tumor bed.49,92 Recent studies suggest that using a more limited field of irradiation that avoids the adverse side effects of ventricular exposure may be sufficient; however, these studies lack long-term follow-up.143

Radiation therapy may be withheld for the rare, histologically benign pineocytoma or ependymoma that has been completely resected.42,92,106,137 Identification of this exception is based on intraoperative observation of a well-circumscribed tumor that is well differentiated histologically. Surgical resection alone provides excellent long-term control in these circumstances, but careful follow-up is necessary so that radiation therapy can be contemplated at the first sign of recurrence.

Germinomas are the most radiosensitive malignant tumors in the central nervous system. Some studies report a 90% long-term control rate for these tumors.93,146,148 Among series with more long-term follow-up, 5-year survival rates greater than 75% and 10-year survival rates of 69% have been reported with radiation doses of 5000 cGy.62,149,150 With less than 5000 cGy, a higher incidence of local failure can be expected.100,150 Germinomas associated with elevated β-human chorionic gonadotropin levels may have a less favorable prognosis.151,152

Methods of reducing radiation doses are being investigated to avoid the associated long-term side effects. These methods include treatment strategies that combine radiation therapy with chemotherapy.15,95,153–156 Cognitive deficits, hypothalamic and endocrine dysfunction, cerebral necrosis, and de novo tumor formation are some of the reported delayed complications of cranial radiation therapy.18,20,25,157–159 This has particular significance for patients with pineal region tumors because the excellent long-term survival after radiation therapy means that they are likely to live long enough to manifest long-term side effects. Pediatric patients are particularly vulnerable to adverse radiation effects.68,160–163

Prophylactic spinal irradiation is controversial in the setting of pineal region tumors. Previously, complete cranial-spinal irradiation was recommended for all malignant pineal tumors; however, the current trend is to avoid spinal irradiation unless there is documented evidence of spinal seeding.* Overall, the incidence of spinal seeding is relatively low, and it is not clear that spinal irradiation prevents metastasis to the spine when no tumor is present on postoperative staging. When seeding has been documented, a dose of 3500 cGy is recommended for the spine.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy has been most beneficial in patients with nongerminomatous malignant germ cell tumors; significant improvement in long-term follow-up has been demonstrated with current regimens. Patients with germinomas containing syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells have a less favorable prognosis and may benefit from more aggressive treatment with chemotherapy in addition to radiotherapy.42,92,166

Most of the germ cell chemotherapy regimens have been extrapolated from experience treating germ cell tumors of extracranial origin, where success has been remarkable.167–170 Unfortunately, these regimens have not been as successful in treating intracranial tumors.16,25,40,68,80,152,171–174 Most successful chemotherapy regimens are derived from protocols for testicular cancer that use the Einhorn regimen of cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin, although other combinations involving cyclophosphamide or etoposide have been investigated.95,172,175 Recent studies using VP-16 (etoposide) in place of vinblastine and bleomycin to avoid pulmonary toxicity have shown improved response rates with less morbidity.152,171,173 Currently, a regimen of cisplatin or carboplatin with etoposide is among the most widely used.

The role of radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy in these tumors is unclear.176 Even though radiation therapy is generally given before chemotherapy, the optimal timing has not been defined. An aggressive approach seems reasonable given the poor prognosis of patients with these tumors. Whether radiation therapy improves survival over chemotherapy alone is not clear, although several reports show increased survival in patients aggressively treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery.16,49,68,77,95,177–180 Delayed surgery after radiation therapy and chemotherapy is indicated for patients with residual tumors whose germ cell markers have normalized.181,182 The residual tumor is likely to be benign germ cell elements that are resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. For pure germinomas, the exquisite radiosensitivity of these tumors has made chemotherapy less compelling, except for patients with recurring or metastatic disease. This success has spurred interest in the use of chemotherapy as a means of reducing the overall dosage of radiation.15,153–156,183 Although this is a sound philosophy, the long-term results have not withstood the same test of time that radiation therapy alone has for these tumors.

Chemotherapy has been used mostly for recurrent or disseminated pineal cell tumors.40,56,147,184 There have been some positive responses with various combinations of vincristine, lomustine, cisplatin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, actinomycin D, and methotrexate. Success with these various regimens has been limited, however, so no clear-cut recommendations can be given.139

Radiosurgery

One of the more recent developments in the treatment of pineal region tumors is the application of radiosurgical techniques.22,24,185,186 Several studies have clearly documented the relative safety of this method, although long-term follow-up results are currently lacking. The problem with radiosurgery is not the response of the targeted mass, but recurrence of tumor outside the treatment volume. Radiosurgery is generally limited to tumors smaller than 3 cm in diameter.

The distinct differences in the radiobiologic effects of radiosurgery and conventional fractionated radiation therapy must be considered when choosing optimal therapeutic strategies. Germinomas, for example, have an excellent long-term response to fractionated radiation, and it is unlikely that radiosurgery can improve on these results. Additionally, because radiosurgery provides no therapeutic coverage of the ventricular system, tumors such as pineal cell and germ cell tumors are particularly vulnerable to ventricular recurrence. Radiosurgery may have its greatest benefit in providing a local boost to the tumor bed so that exposure of the ventricles and surrounding brain to radiation can be reduced.22,187 It may also be useful for tumors that recur locally.

Bruce JN, Ogden AT. Surgical strategies for treating patients with pineal region tumors. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:221.

Bruce JN, Stein BM. Surgical management of pineal region tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;134:130.

Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Jurgens H, et al. Impact of surgery, chemotherapy and irradiation on long term outcome of intracranial malignant non-germinomatous germ cell tumors: results of the German Cooperative Trial MAKEI 89. Klin Padiatr. 2004;216:141.

Edwards MS, Hudgins RJ, Wilson CB, et al. Pineal region tumors in children. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:689.

Fetell MR, Bruce JN, Stein BM. Benign cystic enlargement of the pineal gland. Neurology. 1989;39(suppl 1):220.

Ho DM, Liu H-C. Primary intracranial germ cell tumor: pathologic study of 51 patients. Cancer. 1992;70:1577.

Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:155.

Jouvet A, Saint-Pierre G, Fauchon F, et al. Pineal parenchymal tumors: a correlation of histological features with prognosis in 66 cases. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:49.

Kobayashi T, Kida Y, Mori Y. Stereotactic gamma radiosurgery for pineal and related tumors. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:301.

Kobayashi T, Yoshida J, Ishiyama J, et al. Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide for malignant intracranial germ-cell tumors. An experimental and clinical study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:676.

Konovalov AN, Pitskhelauri DI. Principles of treatment of the pineal region tumors. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:250.

Kreth FW, Schatz CR, Pagenstecher A, et al. Stereotactic management of lesions of the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:280.

Lapras C, Patet JD, Mottolese C, et al. Direct surgery for pineal tumors: occipital-transtentorial approach. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1987;30:268.

Linstadt D, Wara WM, Edwards MSB, et al. Radiotherapy of primary intracranial germinomas: the case against routine craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:291.

Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:446.

Pople IK, Athanasiou TC, Sandeman DR, et al. The role of endoscopic biopsy and third ventriculostomy in the management of pineal region tumours. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:305.

Regis J, Bouillot P, Rouby-Volot F, et al. Pineal region tumors and the role of stereotactic biopsy: review of the mortality, morbidity, and diagnostic rates in 370 cases. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:907.

Sawamura Y, de Tribolet N, Ishii N, et al. Management of primary intracranial germinomas: diagnostic surgery or radical resection? J Neurosurg. 1997;87:262.

Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Haddock MG, et al. Histologically confirmed pineal tumors and other germ cell tumors of the brain. Cancer. 1996;78:2564.

Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Schomberg PJ, et al. Pineal parenchymal tumors. Clinical, pathologic, and therapeutic aspects. Cancer. 1993;72:870.

Stein BM. The infratentorial supracerebellar approach to pineal lesions. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:197.

Stein BM, Bruce JN. Surgical management of pineal region tumors (honored guest lecture). Clin Neurosurg. 1992;39:509.

Yamini B, Refai D, Rubin CM, et al. Initial endoscopic management of pineal region tumors and associated hydrocephalus: clinical series and literature review. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:437.

Yoshida J, Sugita K, Kobayashi T, et al. Prognosis of intracranial germ cell tumours: effectiveness of chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide (CDDP and VP-16). Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;120:111.

1 Borit A. History of tumors of the pineal region. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:613.

2 Zulch KJ. Reflections on the surgery of the pineal gland (a glimpse into the past). Neurosurg Rev. 1981;4:159.

3 Oppenheim H, Krause F. Operative Erfolge bei Geschwulsten der sehhugel- und. Vierhugelgegend. Berl Klin Wochenshr. 1913;50:2316.

4 Dandy WE. An operation for the removal of pineal tumors. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1921;33:113.

5 Krause F. Operative Frielegung der Vierhugel, nebst Beobachtungen uber Hirndruck und. Dekompression. Zentrabl Chir. 1926;53:2812.

6 Abay EO2nd, Laws ERJr, Grado GL, et al. Pineal tumors in children and adolescents. Treatment by CSF shunting and radiotherapy. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:889.

7 Cummins FM, Taveras JM, Schlesinger EB. Treatment of gliomas of the third ventricle and pinealomas; with special reference to the value of radiotherapy. Neurology. 1960;10:1031.

8 Dandy WE. Operative experience in cases of pineal tumor. Arch Surg. 1936;33:19.

9 DeGirolami U, Schmidek H. Clinicopathological study of 53 tumors of the pineal region. J Neurosurg. 1973;39:455.

10 Donat JF, Okazaki H, Gomez MR, et al. Pineal tumors. A 53-year experience. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:736.

11 Poppen JL, Marino RJr. Pinealomas and tumors of the posterior portion of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:357.

12 Rand R, Lemmen L. Tumors of the posterior portion of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1953;10:1.

13 Van Wagenen WP. A surgical approach for the removal of certain pineal tumors. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1931;53:216.

14 Araki C, Matsumoto S. Statistical re-evaluation of pinealoma and related tumours in Japan. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1969;30:307.

15 Kochi M, Itoyama Y, Shiraishi S, et al. Successful treatment of intracranial nongerminomatous malignant germ cell tumors by administering neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy before excision of residual tumors. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:106.

16 Takakura K. Intracranial germ cell tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:429.

17 Waga S, Handa H, Yamashita J. Intracranial germinomas: treatment and results. Surg Neurol. 1979;2:167.

18 Duffner P, Cohen M, Thomas P, et al. The long-term effects of cranial irradiation on the central nervous system. Cancer. 1985;56:1841.

19 Jenkin D, Berry M, Chan H, et al. Pineal region germinomas in childhood treatment considerations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;18:541.

20 Sakai N, Yamada H, Andoh T, et al. Primary intracranial germ-cell tumors. A retrospective analysis with special reference to long-term results of treatments and the behavior of rare types of tumors. Acta Oncol. 1988;27:43.

21 Bruce JN. Management of pineal region tumors. Neurosurg Q. 1993;3:103.

22 Casentini L, Colombo F, Pozza F, et al. Combined radiosurgery and external radiotherapy of intracranial germinomas. Surg Neurol. 1990;34:79.

23 Chapman PH, Linggood RM. The management of pineal area tumors: a recent reappraisal. Cancer. 1980;46:1253.

24 Dempsey PK, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic diagnosis and treatment of pineal region tumours and vascular malformations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;116:14.

25 Edwards MS, Hudgins RJ, Wilson CB, et al. Pineal region tumors in children. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:689.

26 Hoffman H, Yoshida M, Becker L, et al. Pineal region tumors in childhood. Experience at the Hospital for Sick Children. In: Humphreys R, editor. Concepts in Pediatric Neurosurgery 4. Basel: S Karger; 1983:360.

27 Hoffman HJ, Yoshida M, Becker LE, et al. Experience with pineal region tumours in childhood. Neurol Res. 1984;6:107.

28 Neuwelt EA. An update on the surgical treatment of malignant pineal region tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:397.

29 Pluchino F, Broggi G, Fornari M, et al. Surgical approach to pineal tumours. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;96:26.

30 Rout D, Sharma A, Radhakrishnan VV, et al. Exploration of the pineal region: observations and results. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:135.

31 Stein BM. The infratentorial supracerebellar approach to pineal lesions. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:197.

32 Suzuki J, Iwabuchi T. Surgical removal of pineal tumors (pinealomas and teratomas). Experience in a series of 19 cases. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:565.

33 Bruce JN, Fetell MR, Stein BM. Surgical approaches to pineal tumors. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1023.

34 Lapras C, Patet JD, Mottolese C, et al. Direct surgery for pineal tumors: occipital-transtentorial approach. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1987;30:268.

35 Poppen JL. The right occipital approach to a pinealoma. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:706.

36 Reid WS, Clark WK. Comparison of the infratentorial and transtentorial approaches to the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1978;3:1.

37 Sano K. Pineal region and posterior third ventricular tumors: a surgical overview. In: Apuzzo M, editor. Surgery of the Third Ventricle. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987:663.

38 Little KM, Friedman AH, Fukushima T. Surgical approaches to pineal region tumors. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:287.

39 Fuller B, Kapp D, Cox R. Radiation therapy of pineal region tumors: 25 new cases and a review of 208 previously reported cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;28:229.

40 Packer RJ, Sutton LN, Rosenstock JG, et al. Pineal region tumors of childhood. Pediatrics. 1984;74:97.

41 Shokry A, Janzer RC, Von Hochstetter AR, et al. Primary intracranial germ-cell tumors. A clinicopathological study of 14 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:826.

42 Stein BM, Bruce JN. Surgical management of pineal region tumors (honored guest lecture). Clin Neurosurg. 1992;39:509.

43 Ventureyra EC. Pineal region: surgical management of tumours and vascular malformations. Surg Neurol. 1981;16:77.

44 Konovalov AN, Pitskhelauri DI. Principles of treatment of the pineal region tumors. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:250.

45 Erlich S, Apuzzo M. The pineal gland: anatomy, physiology and clinical significance. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:321.

46 Quest DO, Kleriga E. Microsurgical anatomy of the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:385.

47 Yamamoto S, Kageyama N. Microsurgical anatomy of the pineal region. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:205.

48 Krabbe KH. The pineal gland, especially in relation to the problem on its supposed significance in sexual development. Endocrinology. 1923;7:379.

49 Bruce JN, Connolly ES, Stein BM. Pineal and germ cell tumors. In: Kaye AH, Laws ER, editors. Brain Tumors. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2001:771.

50 Horowitz MB, Hall WA. Central nervous system germinomas. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:652.

51 Sano K. Pineal region tumors: problems in pathology and treatment. Clin Neurosurg. 1984;30:59.

52 Kashiwagi S, Hatano M, Yokoyama T. Metastatic small cell carcinoma to the pineal body: case report. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:810.

53 Smith WT, Hughes B, Ermocilla R. Chemodectoma of the pineal region, with observations of the pineal body and chemoreceptor tissue. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1966;92:69.

54 Fukui M, Matsuoka S, Hasuo K, et al. Cavernous hemangioma in the pineal region. Surg Neurol. 1983;20:209.

55 Fetell MR, Bruce JN, Burke AM, et al. Non-neoplastic pineal cysts. Neurology. 1991;41:1034.

56 Sawaya R, Hawley DK, Tobler WD, et al. Pineal and third ventricular tumors. In: Youmans J, editor. Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:3171.

57 Burres KP, Hamilton RD. Pineal apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:264.

58 Herrick MK, Rubinstein LJ. The cytological differentiating potential of pineal parenchymal neoplasms (true pinealomas). A clinicopathological study of 28 tumours. Brain. 1979;102:289.

59 Higashi K, Katayama S, Orita T. Pineal apoplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1979;42:1050.

60 Steinbok P, Dolmen C, Kaan K. Pineocytomas presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:776.

61 Parinaud H. Paralysis of the movement of convergence of the eyes. Brain. 1886;9:330.

62 Posner M, Horrax G. Eye signs in pineal tumors. J Neurosurg. 1946;3:15.

63 Behrens M. Impaired vision. In: Rowland L, editor. Merritt’s Textbook of Neurology. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:35.

64 DeMonte F, Zelby A, Al-Mefty O. Hearing impairment resulting from a pineal region meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:665.

65 Missori P, Delfini R, Cantore G. Tinnitus and hearing loss in pineal region tumours. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;135:154.

66 Fetell MR, Stein BM. Neuroendocrine aspects of pineal tumors. In: Zimmeman EA, Abrams GM, editors. Neurologic Clinics: Neuroendocrinology and Brain Peptides, Vol 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1986:877.

67 Zondek H, Kaatz A, Unger H. Precocious puberty and chorioepithelioma of the pineal gland with report of a case. J Endocrinol. 1953;10:12.

68 Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:155.

69 Müller-Forell W, Schroth G, Egan PJ. MR imaging in tumors of the pineal region. Neuroradiology. 1988;30:224.

70 Tien RD, Barkovich AJ, Edwards MSB. M.R. imaging of pineal tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:557.

71 Zimmerman R. Pineal region masses: Radiology. In: Wilkins R, Rengachary S, editors. Neurosurgery, Vol 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:680.

72 Satoh H, Uozumi T, Kiya K, et al. MRI of pineal region tumours: relationship between tumours and adjacent structures. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:624.

73 Zimmerman H. Introduction to tumors of the central nervous system. In: Minckler J, editor. Pathology of the Nervous System, Vol 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971:1947.

74 Ganti SR, Hilal SK, Silver AJ, et al. CT of pineal region tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986;7:97.

75 Allen JC, Nisselbaum J, Epstein F, et al. Alphafetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin determination in cerebrospinal fluid. An aid to the diagnosis and management of intracranial germ-cell tumors. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:368.

76 Arita N, Ushio Y, Hayakawa T, et al. Serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin and carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with primary intracranial germ cell tumors. Oncodev Biol Med (Amsterdam). 1980;1:235.

77 Bamberg M, Metz K, Alberti W, et al. Endodermal sinus tumor of the pineal region. Metastasis through a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Cancer. 1984;54:903.

78 Jooma R, Kendall BE. Diagnosis and management of pineal tumors. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:654.

79 Wilson ER, Takei Y, Bikoff WT, et al. Abdominal metastases of primary intracranial yolk sac tumors through ventriculoperitoneal shunts: report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 1979;5:356.

80 Haase J, Norgaard-Pedersen B. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) as biochemical markers of intracranial germ cell tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1979;53:269.

81 Neuwelt E, Smith R. Presence of lymphocyte membrane surface markers on “small cells” in a pineal germinoma. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:133.

82 Page R, Doshi B, Sharr M. Primary intracranial choriocarcinoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:93.

83 Takeuchi J, Handa H, Nagata I. Suprasellar germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:41.

84 Russell DS, Rubinstein LJ. Tumours and tumour-like lesions of maldevelopmental origin. In: Russell DS, Rubinstein LJ, editors. Pathology of Tumours of the Nervous System. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989:664.

85 Metcalfe S, Sikora K. A new marker for testicular cancer. Br J Cancer. 1985;52:127.

86 Shinoda J, Yamada H, Sakai N, et al. Placental alkaline phosphatase as a tumor marker for primary intracranial germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:710.

87 Arendt J. Melatonin as a tumour marker in a patient with pineal tumour. Br Med J. 1978;2:635.

88 Barber S, Smith J, Hughes R. Melatonin as a tumour marker in a patient with pineal tumour. Lancet. 1978;2:328.

89 Korf HW, Bruce JA, Vistica B, et al. Immunoreactive S-antigen in cerebrospinal fluid: a marker of pineal parenchymal tumors? J Neurosurg. 1989;70:682.

90 Wurtman RJ, Kammer H. Melatonin synthesis by an ectopic pinealoma. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:1233.

91 Goodman R. Magnetic resonance imaging–directed stereotactic endoscopic third ventriculostomy. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:1043.

92 Bruce JN, Ogden AT. Surgical strategies for treating patients with pineal region tumors. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:221.

93 Villano JL, Propp JM, Porter KR, et al. Malignant pineal germ-cell tumors: an analysis of cases from three tumor registries. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:121.

94 Fevre-Montange M, Hasselblatt M, Figarella-Branger D, et al. Prognosis and histopathologic features in papillary tumors of the pineal region: a retrospective multicenter study of 31 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1004.

95 Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Jurgens H, et al. Impact of surgery, chemotherapy and irradiation on long term outcome of intracranial malignant non-germinomatous germ cell tumors: results of the German Cooperative Trial MAKEI 89. Klin Padiatr. 2004;216:141.

96 Zee C-S, Segall H, Apuzzo M, et al. MR imaging of pineal region neoplasms. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:56.

97 Fujimaki T, Matsutani M, Funada N, et al. CT and MRI features of intracranial germ cell tumors. J Neurooncol. 1994;19:217.

98 Liang L, Korogi Y, Sugahara T, et al. MRI of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:382.

99 D’Andrea AD, Packer RJ, Rorke LB, et al. Pineocytomas of childhood. A reappraisal of natural history and response to therapy. Cancer. 1987;59:1353.

100 Kersh CR, Constable WC, Eisert DR, et al. Primary central nervous system germ cell tumors: effect of histologic confirmation on radiotherapy. Cancer. 1988;61:2148.

101 Wood JH, Zimmerman RA, Bruce DA, et al. Assessment and management of pineal-region and related tumors. Surg Neurol. 1981;16:192.

102 Choi JU, Kim DS, Chung SS, et al. Treatment of germ cell tumors in the pineal region. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14:41.

103 Chandrasoma PT, Smith MM, Apuzzo MLJ. Stereotactic biopsy in the diagnosis of brain masses: comparison of results of biopsy and resected surgical specimen. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:160.

104 Ho DM, Liu H-C. Primary intracranial germ cell tumor: pathologic study of 51 patients. Cancer. 1992;70:1577.

105 Kraichoke S, Cosgrove M, Chandrasoma PT. Granulomatous inflammation in pineal germinoma. A cause of diagnostic failure at stereotaxic brain biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:655.

106 Bruce JN, Stein BM. Surgical management of pineal region tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;134:130.

107 Sawamura Y, de Tribolet N, Ishii N, et al. Management of primary intracranial germinomas: diagnostic surgery or radical resection? J Neurosurg. 1997;87:262.

108 Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Haddock MG, et al. Histologically confirmed pineal tumors and other germ cell tumors of the brain. Cancer. 1996;78:2564.

109 Kreth FW, Schatz CR, Pagenstecher A, et al. Stereotactic management of lesions of the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:280.

110 Pecker J, Scarabin JM, Vallee B, et al. Treatment in tumours of the pineal region: value of sterotaxic biopsy. Surg Neurol. 1979;12:341.

111 Regis J, Bouillot P, Rouby-Volot F, et al. Pineal region tumors and the role of stereotactic biopsy: review of the mortality, morbidity, and diagnostic rates in 370 cases. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:907.

112 Peragut JC, Dupard T, Graziani N, et al. De la prévention des risques de la biopsie stéréotaxique de certaines tumeurs de la région pinéale: a propos de 3 observations. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33:23.

113 Rosenfeld JV, Murphy MA, Chow CW. Implantation metastasis of pineoblastoma after stereotactic biopsy. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:287.

114 Maciunas R. Stereotactic biopsy of pineal region lesions. In: Kaye A, Black P, editors. Operative Neurosurgery, Vol 1. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:841.

115 Yamini B, Refai D, Rubin CM, et al. Initial endoscopic management of pineal region tumors and associated hydrocephalus: clinical series and literature review. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:437.

116 Pople IK, Athanasiou TC, Sandeman DR, et al. The role of endoscopic biopsy and third ventriculostomy in the management of pineal region tumours. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:305.

117 Gaab MR, Schroeder HW. Neuroendoscopic approach to intraventricular lesions. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:496.

118 Ferrer E, Santamarta D, Garcia-Fructuoso G, et al. Neuroendoscopic management of pineal region tumours. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1997;139:12.

119 Chernov MF, Kamikawa S, Yamane F, et al. Neurofiberscopic biopsy of tumors of the pineal region and posterior third ventricle: indications, technique, complications, and results. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:267.

120 Bruce JN. Posterior third ventricular tumors. In: Kaye AH, Black PM, editors. Operative Neurosurgery, Vol 1. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:769.

121 Bruce JN, Stein BM. Supracerebellar approach for pineal region neoplasms. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:755.

122 Bruce JN, Stein BM. Supracerebellar approach to pineal region neoplasms, 4th ed. Schmidek HH, editor. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques, Vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2000:908.

123 Bruce JN, Stein BM. Complications of surgery for pineal region tumors. In: Post KD, Friedman ED, McCormick PC, editors. Postoperative Complications in Intracranial Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 1993:74.

124 McComb JG, Apuzzo MLJ. The lateral decubitus position for the surgical approach to pineal location tumors. Concepts Pediatr Neurosurg. 1988;8:186.

125 Ausman JI, Malik GM, Dujovny M, et al. Three-quarter prone approach to the pineal-tentorial region. Surg Neurol. 1988;29:298.

126 Kobayashi S, Sugita K, Tanaka Y, et al. Infratentorial approach to the pineal region in the prone position: Concorde position. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:141.

127 Ueyama T, Al-Mefty O, Tamaki N. Bridging veins on the tentorial surface of the cerebellum: a microsurgical anatomic study and operative considerations. J Neurosurg. 1998;43:1137.

128 Bruce J, Stein B. Supracerebellar approaches in the pineal region. In: Apuzzo M, editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1993:511.

129 Apuzzo M, Tung H. Supratentorial approaches to the pineal region. In: Apuzzo M, editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1993:486.

130 McComb J, Levy M, Apuzzo M. The posterior intrahemispheric retrocallosal and transcallosal approaches to the third ventricle region. In: Apuzzo M, editor. Surgery of the Third Ventricle. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:743.

131 Horrax G. Extirpation of a huge pinealoma from a patient with pubertas praecox. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;37:385.

132 Lapras C, Patet JD. Controversies, techniques and strategies for pineal tumor surgery. In: Apuzzo MLJ, editor. Surgery of the Third Ventricle. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987:649.

133 Apuzzo M, Litofsky N. Surgery in and around the anterior third ventricle. In: Apuzzo M, editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management, Vol 1. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:541.

134 Nazzaro JM, Shults WT, Neuwelt EA. Neuro-ophthalmological function of patients with pineal region tumors approached transtentorially in the semisitting position. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:746.

135 Chandy MJ, Damaraju SC. Benign tumours of the pineal region: a prospective study from 1983 to 1997. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:228.

136 Rubinstein LJ. Cytogenesis and differentiation of pineal neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 1981;12:441.

137 Vaquero J, Ramiro J, Martinez R, et al. Clinicopathological experience with pineocytomas: report of five surgically treated cases. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:612.

138 Deshmukh VR, Smith KA, Rekate HL, et al. Diagnosis and management of pineocytomas. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:349.

139 Chang SM, Lillis-Hearne PK, Larson DA, et al. Pineoblastoma in adults. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:383.

140 Rippe JD, Boyko OB, Friedman HS, et al. Gd-DTPA–enhanced MR imaging of leptomeningeal spread of primary intracranial CNS tumor in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:329.

141 Shibamoto Y, Abe M, Yamashita J, et al. Treatment results of intracranial germinoma as a function of irradiated volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:285.

142 Ueki K, Tanaka R. Treatments and prognoses of pineal tumors—experience of 110 cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1980;20:1.

143 Dattoli MJ, Newall J. Radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: the case for limited volume treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:429.

144 Disclafani A, Hudgins RJ, Edwards SB, et al. Pineocytomas. Cancer. 1989;63:302.

145 Linstadt D, Wara WM, Edwards MSB, et al. Radiotherapy of primary intracranial germinomas: the case against routine craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:291.

146 Wolden SL, Wara WM, Larson DA, et al. Radiation therapy for primary intracranial germ-cell tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:943.

147 Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Schomberg PJ, et al. Pineal parenchymal tumors. Clinical, pathologic, and therapeutic aspects. Cancer. 1993;72:870.

148 Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:446.

149 Sano K, Matsutani M. Pinealoma (germinoma) treated by direct surgery and postoperative irradiation. Childs Brain. 1981;8:81.

150 Sung DI, Harisliadis L, Chang CH. Midline pineal tumors and suprasellar germinomas: highly curable by irradiation. Radiology. 1978;128:745.

151 Uematsu Y, Tsuura Y, Miyamoto K, et al. The recurrence of primary intracranial germinomas. Special reference to germinoma with STGC (syncytiotrophoblastic giant cell). J Neurooncol. 1992;13:247.

152 Yoshida J, Sugita K, Kobayashi T, et al. Prognosis of intracranial germ cell tumours: effectiveness of chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide (CDDP and VP-16). Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;120:111.

153 Allen JC, Kim JH, Packer RJ. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed germ-cell tumors of the central nervous system. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:65.

154 Sawamura Y, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by reduced-volume radiation therapy for newly diagnosed central nervous system germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:66.

155 Silvani A, Eoli M, Salmaggi A, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for intracranial germinomas in adult patients: a single-institution study. J Neurooncol. 2005;71:271.

156 Aoyama H, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by low-dose involved-field radiotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:857.

157 Hodges LC, Smith LJ, Garrett A, et al. Prevalence of glioblastoma multiforme in subjects prior to therapeutic radiation. J Neurosci Nurs. 1992;24:79.

158 Nighoghossian N, Confavreaux C, Sassolas G, et al. Insuffisance hypothalamique apres irradiation demence tardive, subaigue et curable. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1988;144:215.

159 Noell K, Herskovic A. Principles of radiotherapy of CNS tumors. In: Wilkins R, Rengachary S, editors. Neurosurgery, Vol 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:1084.

160 Bendersky M, Lewis M, Mandelbaum DE, et al. Serial neuropsychological follow-up of a child following craniospinal irradiation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988;30:808.

161 Donahue B. Short- and long-term complications of radiation therapy for pediatric brain tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:207.