CHAPTER 205 Familial Tumors (Neurocutaneous Syndromes)

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Epidemiology and Genetics

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1; also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease) is the most common neurocutaneous syndrome, with a prevalence of 1 in 2190 to 7800.1 The NF1 gene encodes the protein neurofibromin; the NF1 mutation responsible for NF1 features autosomal dominant inheritance with complete penetrance but variable expression, although roughly half of cases appear sporadically, probably secondary to new mutations.2–4

The NF1 gene maps to the locus 17q11.2, where it spans more than 350 kilobases of DNA.5 The gene contains 59 exons encoding the protein product neurofibromin.6 Neurofibromin, a 2818–amino acid protein, bears significant homology with members of the guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase)-activating protein (GAP) superfamily, which led it to be dubbed the NF1-GAP–related protein (NF1-GRP).7 This protein interacts with the intrinsic GTPase of p21-Ras-guanosine triphosphate (GTP) by hydrolyzing GTP to guanosine diphosphate (GDP) and thus inactivating p21-Ras.8,9 Because p21-Ras plays a pivotal role in many growth factor signaling pathways, its unregulated function in the absence of neurofibromin—resulting in constitutive p21-Ras activation—leads to an overall tendency toward increased cell proliferation and survival.10,11

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of NF1, as outlined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference Statement, hinges on the presence of two or more of seven distinct criteria, as noted in Table 205-1.12

TABLE 205-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis Type 1

From National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13-15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1:172.

The aforementioned diagnostic features are the hallmarks of the disease, and the skin findings, in particular, are conducive to accurate identification of this patient population (Fig. 205-1). However, a pitfall in the diagnosis of pediatric patients is that these cutaneous manifestations may develop late and therefore younger affected individuals may appear free of NF1 stigmata. Consequently, the neurosurgeon must be cognizant of NF1 as a possible underlying diagnosis during patient evaluation because it may have an impact on the care of several neurosurgical lesions.

Clinical Features and Management

The care of patients with neurofibromatosis involves multiple medical specialties. Of particular importance to the neurosurgeon is the development of central nervous system (CNS) tumors in this patient population. Older series report an incidence of CNS tumors of roughly 10%, although studies using modern imaging techniques suggest that the rate may be much higher.13–15 The lesions most likely to come to neurosurgical attention include optic gliomas, plexiform or other neurofibromas, brainstem gliomas, and cerebellar gliomas.

Neurofibromas

Neurofibroma, one of the characteristic lesions of NF1, affects the peripheral nerves. Neurofibromas consist of Schwann cells and fibroblasts, in addition to perineural cells, endothelial cells, mast cells, pericytes, and other intermediate cell types; the fundamental architectural feature involves Schwann cells in increased number and with reduced association with axons, along with breakdown of the perineural layer and disorganization of supporting cells.10,16,17 Neurofibromas are nearly ubiquitous in NF1 patients and follow a characteristically indolent and benign course. For this reason, the optimal management of neurofibromas involves careful observation, with surgical intervention reserved for symptomatic cases.

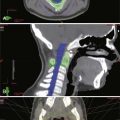

Plexiform neurofibromas pose particular management challenges. These tumors, in contrast to simple neurofibromas, extend across the length of a nerve and involve multiple nerve fascicles or multiple branches of a large nerve, or both, thereby resulting in a potentially sizable mass of diffusely thickened nervous tissue (Fig. 205-2).18 Plexiform neurofibromas were identified on physical examination in 26.7% of individuals in one study and were detected on chest/abdomen/pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scans in the thoracic region of 20% of patients and in the abdomen/pelvis in 44% of patients.19,20 The lesions that are most likely to come to the attention of the neurosurgeon involve the spine or, less commonly, the brachial plexus.

FIGURE 205-2 Coronal magnetic resonance imaging scan showing plexiform neurofibroma affecting every nerve root.

Plexiform neurofibromas pose an unusual management challenge because they frequently involve nerve roots at multiple levels, which in turn leads to extensive spinal compression and resultant myelopathy and quadriparesis/paraparesis.21–23 The surgical goal of treatment in such cases is control of symptoms because these lesions are not amenable to cure without the profound, unacceptable morbidity associated with the resection of nerve roots at multiple levels. However, good results can be obtained with laminectomy for debulking and decompression of the involved spinal levels. Loss of neurological function is rare after surgery.22,24 Regrowth of tumor with recurrence of symptoms has been noted, with secondary reoperation typically providing some benefit. Progressive kyphosis is also a significant concern after multilevel laminectomies, and patients may require subsequent spinal fusion. Most authors, however, do not advocate undertaking fusion at the time of initial resection, and the risk for progression of kyphosis may be reduced with the use of osteoplastic laminotomy techniques to preserve some degree of competency of the posterior elements.21–25 Standard recommendations do not include routine spinal imaging for NF1 patients because the symptoms, not imaging characteristics, ultimately determine surgical management.22

Neurofibromas also carry the potential for degeneration to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs). Independent studies have recently shown the lifetime risk for MPNST in NF1 patients to be 8% to 13% and 5.9% to 10.3%.15,26 Although conventional wisdom holds that these tumors affect adults with NF1, in 35% of patients with MPNST lesions first developed when younger than 20 years.27 In a more recent study, 15% of MPNST patients were initially seen when younger than 17 years and had a mean survival time of 30.5 months.28 In both studies, MPNSTs arose primarily from nodular neurofibromas or plexiform neurofibromas, with pain or enlargement of a mass being the typical initial signs. Although MPNST may be infrequent, an awareness of its relationship to neurofibromas in NF1 is essential because the possibility of underlying malignant degeneration might influence the surgeon to pursue earlier, more aggressive resection of plexiform or simple neurofibromas.

Optic Gliomas

Gliomas of the anterior optic pathway occur in up to 15% of NF1 patients and commonly affect the optic nerve or chiasm or the hypothalamus.14 Unlike sporadic optic pathway gliomas, which are seen almost exclusively in children younger than 7 years, optic gliomas in NF1 may occur at any time.29 Symptoms referable to these lesions include headache, visual complaints, proptosis, endocrine disturbances, and other findings stemming from local mass effect or hydrocephalus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality for these lesions and may be useful in prognostication: evidence suggests that nonenhancing optic gliomas—which may constitute almost 60%—do not progress.30 The optic pathway gliomas in patients with NF1 are usually World Health Organization (WHO) grade I astrocytomas, although a recent study reported higher grade lesions occurring in this region as well.29,31

As with most neurosurgical lesions in patients with NF1, the optimal treatment strategy for optic gliomas probably involves conservative monitoring until MRI progression is documented or symptoms develop. However, treatment of optic gliomas in NF1 patients may be distinct from that of patients with sporadic optic gliomas in that the former patients may exhibit a much more indolent clinical course.32–41 A recent systematic review of prognostic factors in patients with optic pathway gliomas demonstrated the complex nature of this issue: although multiple studies have claimed NF1 to be prognostically beneficial, all but one had significant methodologic limitations, including a failure in some cases to differentiate NF1 status from tumor site or age in prognostication.42 Most authors recommend surgical intervention only in patients with an atypical appearance on MRI—which should encourage biopsy—or in patients with progressive symptoms, for which craniotomy and debulking should be undertaken.30,43 Subtotal resection may be acceptable or even preferable, given the significant morbidity associated with aggressive resection near the optic apparatus. Adjuvant therapy typically involves chemotherapy, with vincristine and carboplatin being first-line agents.44 Radiation therapy can also be considered but carries with it the risks of radiation necrosis, cognitive problems, visual loss, secondary malignancy, and even moyamoya disease.43,45 In planning optimal therapy, one must remain cognizant of the potential for lesion stability or even regression of lesions in NF1 patients.30,46

Brainstem Gliomas

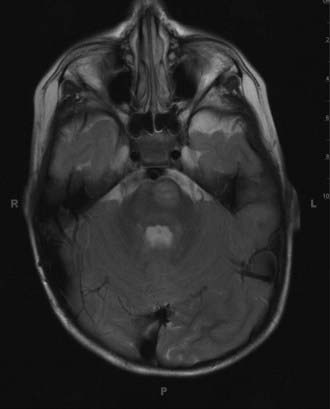

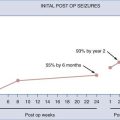

Although brainstem gliomas (Fig. 205-3) generally represent one of the more malignant of childhood neoplasms, neurofibromatosis has long been recognized as a favorable prognostic indicator.47 In fact, studies have demonstrated that the brainstem gliomas in NF1, with their characteristically indolent course, exhibit such drastically different behavior from their counterpart lesions in non-NF1 patients that it could be suggested that they are entirely unique clinical entities. One concern in evaluating the natural history of these lesions arises in differentiating them from “unidentified bright objects” (UBOs) of the brainstem, which occur in more than half of NF1 patients and commonly involve the brainstem yet have no apparent predilection for evolving into gliomas. Inclusion of these UBOs in a study of the natural history of brainstem gliomas will lead to erroneous conclusions regarding the indolence of this type of tumor. Several studies have sought to separate these UBOs from actual gliomas and have still found gliomas to follow an indolent course. Indeed, brainstem gliomas in NF1 have been shown to undergo radiographic progression in less than 50% of cases and clinical progression in less than 20% of cases, irrespective of intervention with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy.48–50 A recent study restricted to the clinical outcomes of 23 patients with expansile brainstem lesions demonstrated that all but 1 exhibited clinical stability or regression over a median follow-up period of 67 months.50 It seems that current evidence suggests taking a conservative approach by monitoring these lesions with serial MRI and undertaking therapy only in the event of clear progression.

It is important to note that NF1 patients with brainstem gliomas will frequently have synchronous tumors at other locations in the CNS, including the optic pathways.50

Cerebellar Gliomas

The true incidence of cerebellar gliomas in patients with NF1 is not clear, although it has been estimated that a 10th of pediatric cerebellar gliomas are associated with NF1.51 The pathologic spectrum of these lesions includes pilocytic astrocytoma most commonly, although anaplastic astrocytoma, ganglioglioma, and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma have also been described.13,51–54 Several differences between cerebellar gliomas in NF1 and sporadic cerebellar gliomas have been highlighted. Anatomically, these lesions often occur in the subependymal white matter of the fourth ventricle, in contrast to the typical vermian or hemispheric location of sporadic gliomas.51 In terms of their clinical behavior, some authors have suggested that NF1-associated cerebellar gliomas exhibit a more malignant phenotype than the sporadic subtype, although modern clinical series have not necessarily borne this out.13,51,55 One point that seems less controversial relates to the management of cerebellar gliomas in NF1 patients: in contrast to the wait-and-see approach for optic or brainstem gliomas, cerebellar lesions should be resected whenever clinically feasible because their anatomic location is more amenable to complete resection, which will in many cases be curative. The pathologic grade of the lesion dictates the need for further adjuvant therapy.

Additional Features

Patients with NF1 suffer from a variety of other conditions, including macrocephaly or learning disabilities, or both, in nearly 50% and short stature or scoliosis, or both, in more than 20%.3 For a time it was thought that the learning disabilities might correlate with T2 signal abnormalities on MRI (UBOs), but studies have borne out an association only with bright lesions in the thalamus, not in other brain regions.56,57 Other authors, however, have suggested that UBOs might not be benign but instead might pose a risk for malignant transformation and hence deserve close follow-up with serial MRI.58,59 Recently, medulloblastomas have been proposed as an additional tumor to which NF1 patients may have a predisposition.60

Although there is a rare association between NF1 and moyamoya disease,61 some controversy exists regarding whether NF1 patients have a predilection for the development of intracranial aneurysms. Even though some case reports demonstrate the presence of aneurysms and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in NF1 patients,62,63 a more exhaustive autopsy series has failed to demonstrate any association.64

Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Epidemiology and Genetics

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is a disorder of autosomal dominant inheritance that affects 1 in 33,000 to 40,000 individuals, with 99% penetrance by the age of 60.65 Like NF1, NF2 patients have a predilection for intracranial, ocular, and skin lesions. Skin findings are less characteristic of NF2 than NF1, but clinical investigation has demonstrated a surprisingly high 60% incidence of skin tumors, including schwannomas, neurofibromas, and mixed tumors as well. Café au lait spots, too, are evident in a third of patients.66 The prototypical and pathognomonic finding in NF2 patients, however, remains the presence of bilateral acoustic schwannomas.

NF2 was first identified as having a distinct genetic basis from NF1 when the NF2 gene was mapped to chromosome 22, where it encodes a cytoskeletal protein dubbed merlin or schwannomin.67–69 Interestingly, the type of mutation in the NF2 gene appears to dictate disease severity, with single-codon/single–amino acid missense alterations, somatic mosaicism, splice site mutations, or large deletions (leading to no protein product) resulting in mild phenotypes. Protein-truncating mutations and frameshift mutations result in a severe phenotype.70–73 Ongoing studies have attempted to elucidate the role of the merlin protein, with evidence that it senses intercellular contact and regulates mitogenic signaling, as well as directs the function of membrane receptors active in cell proliferation and differentiation.74

Diagnosis

With the exception of patients with bilateral vestibular schwannomas, which are pathognomonic for NF2, the optimal diagnostic criteria for this disease remain in flux; current criteria are shown in Table 205-2.12,75 In evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of the four sets of criteria proposed for the diagnosis of NF2 (NIH 1987 and 1991, Manchester, and National Neurofibromatosis Foundation), Baser and colleagues found surprisingly low sensitivity—less than 15%—for each set of criteria in the initial assessment of 163 patients with NF2 but without bilateral acoustic neuromas.76 These sensitivities improved over time as patients were monitored longitudinally, but it is clear that the current criteria may not adequately address the diagnostic challenge posed by this disease.

TABLE 205-2 Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis Type 2

| 1991 NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH CRITERIA |

Data from National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13-15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1:172; and Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, et al. NIH conference. Neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:39.

Clinical Features and Management

NF2 patients may initially be seen with the following lesions: vestibular schwannomas, other schwannomas, meningiomas, gliomas, neurofibromas, and cataracts. Because of the varied clinical manifestations of NF2, referral to tertiary care centers for multidisciplinary management is vital for successful patient outcomes and has been identified, along with age at diagnosis, presence of intracranial meningiomas, and type of NF2 mutation, as one of the primary determinants of risk for mortality.77,78

A detailed discussion of the general management of vestibular schwannomas can be found elsewhere in this text. However, the occurrence of vestibular schwannomas in NF2 patients, especially when bilateral, can pose unique clinical challenges for the neurosurgeon. Vestibular schwannomas develop in more than 95% of NF2 patients and are commonly manifested as deafness (most often unilateral), tinnitus, and vertigo.79–81

The frequent bilaterality of vestibular schwannomas has generated controversy regarding optimal management strategies. Large tumors causing brainstem compression present less of a management dilemma because they should be resected microsurgically to prevent progressive neurological deficits. Conversely, smaller tumors that cause either no symptoms or only audiologic symptoms continue to confound the development of universal management guidelines. Complicating the planning of management strategies is the fact that the natural history of vestibular schwannomas in patients with NF2 remains somewhat unclear, with discordant findings in recent longitudinal studies; however, a recent review evaluating four recent studies does show that although significant variability exists, the growth rates of these tumors tend to decrease with increasing age.82–86 In any case, a multidisciplinary approach to care should be used, and consideration must also be given to patient and family education in sign language to facilitate ongoing communication. Recently, additional concern has been raised with regard to the risk associated with stereotactic radiosurgery in patients genetically predisposed to malignancy because of some evidence suggesting that secondary tumors such as MPNSTs or sarcomas might develop as a result of exposure to radiation (although this link is far from certain).87–90 The possibility of inducing a malignancy after treating a benign lesion again highlights the need for the treating physician to be cautious in the management of this complex disease entity.

The prevalence of posterior subcapsular opacities, which affect roughly 80% of NF2 patients, presents an important clinical consideration because preservation of vision becomes paramount in patients for whom hearing will probably be imperiled.81,91

Intracranial meningiomas occur in roughly half of NF2 patients and may be multiple in about 40%.80,81 NF2-associated meningiomas differ from sporadic forms in that they occur earlier in life, they pathologically show a higher mitotic index and greater nuclear pleomorphism, and they have higher proliferation potential.92

As with NF1, NF2 poses a substantial risk for spinal tumors, typically either meningiomas or schwannomas. Studies have shown that spinal tumors afflict 67% to 90% of NF2 patients, and even though they vary considerably in size and location, surgical resection might be required if radiographic progression or neurological symptoms are documented.80,81,93

Gliomas also develop with greater frequency in NF2 patients, at a rate of roughly 4%, and 80% occur in the spine.79 Their management mirrors that of sporadic gliomas, with the obvious caveat that NF2 patients may have more extensive tumor burden at other sites and may therefore have increased potential for tumor recurrence after therapy.

Tuberous Sclerosis

Epidemiology and Genetics

Tuberous sclerosis (TS), like the other neurocutaneous syndromes thus far discussed, is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although sporadic cases outnumber inherited cases. The overall incidence of this disorder is 1 in 30,000, with a birth incidence of 1 in 5800.94

The genetic loci involved in TS have been traced to chromosomes 9q34 (TSC1) and 16p13 (TSC2), which encode for protein products named hamartin and tuberin, respectively.95–97 These proteins form the tuberin-hamartin complex that controls mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) by acting as a GTPase-activating complex for the protein Rheb (Ras homologue enriched in brain).98–102 Tuberin-hamartin thus acts in regulating cell proliferation, ultimately interacting through mTOR to inhibit the activity of S6 kinase.103

Diagnosis

TS can have a wide variety of clinical findings, with the skin, kidneys, brain, heart, and vasculature most commonly being affected. The classic finding involves a triad of seizures, mental retardation, and skin lesions, although this triad occurs in just 29% of patients and 6% lack all three.104 Skin lesions include hypopigmented macules (also known as “ash leaf spots”), shagreen patches, subungual fibromas, and facial angiofibromas (i.e., adenoma sebaceum) (see Fig. 205-1).105 Other non-CNS findings include renal cysts and angiomyolipomas, renal cell carcinoma, pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis, and cardiac rhabdomyoma.106

The criteria for diagnosing TS have undergone revision to reflect current understanding of the initial features of the disease. No single clinical sign definitively proves the presence of the TS complex, so a combination of radiographic and clinical features, divided into major and minor categories, can be combined to yield a definitive, probable, or possible diagnosis, as outlined in Table 205-3.106–108

| MAJOR |

| MINOR |

* Definitive tuberous sclerosis diagnosis: two major features or one major plus two minor features; probable diagnosis: one major plus one minor feature; possible diagnosis: one major or two or more minor features.

† When both are present together, other features are also required for the diagnosis.

Clinical Features and Management

The causes associated with the decreased life expectancy in patients with TS include renal disease, complications of intracranial tumors, hemorrhage (such as from aortic aneurysms or lymphangiomyomatosis of the lung), status epilepticus, and cardiac rhabdomyomas, in decreasing order of frequency.109

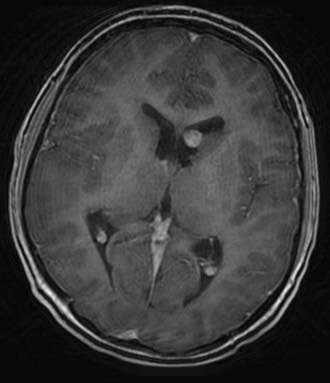

CNS lesions affecting patients with TS include cortical tubers, subependymal nodules (SENs), white matter linear migration lines, transmantle cortical dysplasia, and subependymal giant cell tumors (SGCTs); 90% of all TS patients will demonstrate at least one of these lesions on cranial imaging (Fig. 205-4).110 Most of these lesions cause neurosurgical problems only insofar as they act as epileptogenic foci, although SGCT presents a unique cause of morbidity and mortality.

SGCTs occur in 6% to 18% of TS patients.111,112 Determining the exact incidence of SGCT is difficult, in part because it probably represents one end of a continuum between SENs and SGCT. Histopathologically, SENs and SGCTs are identical and display a mixed glioneuronal lineage; controversy exists over whether size, location, imaging characteristics, or other features should distinguish the two lesions, although a reasonable approach recently proposed is to deem any lesion exhibiting growth on serial imaging or causing hydrocephalus an SGCT.111 When SGCTs become symptomatic, they may exhibit the typical stigmata of elevated intracranial pressure, although a subacute onset of more subtle findings such as lethargy, visual field deficits, or behavioral or cognitive decline may also be seen.111,113,114

The operative approach to SGCTs has ranged from simple shunt placement to early tumor resection before symptoms develop. Over time, the approach to these lesions has become increasingly aggressive for the following reasons: (1) shunts can in some cases be avoided, (2) smaller lesions may lend themselves to easier operative resection, (3) cases of sudden death associated with SGCTs have been reported, (4) and excessive morbidity and mortality seem to be associated with delayed therapy.111,113–115 Recent reports related to the timing of surgery suggest that it should be undertaken at the first sign of clinical symptoms referable to the tumor or to documented growth on serial scans.114 Clearly, serial imaging of TS patients with SENs is recommended.

Operative approaches for SGCTs fall into the categories of transcallosal or transcortical routes, with the former being favored over the latter given the potentially epileptogenic nature of transcortical surgery in an already susceptible patient. Endoscopic management is an additional option. Outcomes typically prove favorable, although perioperative mortality related to acute hydrocephalus remains a catastrophic but potentially avoidable complication.114 These lesions are WHO grade I. Recent studies have characterized them not as astrocytomas but as mixed glioneuronal cell tumors, which has prompted suggestions for a name change from the extant “subependymal giant cell astrocytoma” to SGCT.111,116

Beyond the presence of symptomatic or incidentally discovered intracranial tumors, patients with TS may also come to neurosurgical attention because of their seizures. Eighty percent to 90% of TS patients will suffer from seizures—most of which develop initially within the first year of life—and up to a third will suffer infantile spasms.117 In patients with medically refractory seizures, surgery may be beneficial, especially if the seizures result from focal lesions. A recent systematic review of the literature demonstrated that freedom from seizures was achieved in 57% of such patients, with an additional 18% having a greater than 90% reduction in seizures.118

Von Hippel-Lindau Disease

Epidemiology and Genetics

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, like the other syndromes thus far reviewed, is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Its genetic locus, the VHL gene, is situated on chromosome 3p.119 VHL acts as a tumor suppressor gene, and most patients inherit one defective copy of the gene and one wild-type copy; according to the two-hit hypothesis, inactivation of both VHL alleles leads to tumorigenesis.120 VHL occurs with a birth incidence of 1 in 36,000 and has a roughly 90% penetrance rate.121,122

Diagnosis

One can make a diagnosis of VHL disease on the basis of clinical criteria. If a patient has a family history of the disease, the presence a single CNS hemangioblastoma or a single visceral tumor associated with VHL disease suffices for the diagnosis. In the absence of a family history, the presence of two CNS hemangioblastomas or one CNS hemangioblastoma plus a visceral tumor combines to make the diagnosis.120 Unlike the other neurocutaneous syndromes, VHL disease is not typically associated with skin findings; it has nonetheless been traditionally classified with the phakomatoses.

Clinical Features and Management

Individuals with VHL disease become susceptible to a number of tumors of the CNS, including hemangioblastomas of the cerebellum, spinal cord, brainstem, and nerve roots. Other lesions associated with VHL disease include renal carcinomas and cysts, pheochromocytomas, neuroendocrine tumors, pancreatic cysts, and epididymal cystadenomas.120

Cerebellar hemangioblastomas develop in 84% of patients with VHL disease by the age of 60.122 They are associated with symptoms of a posterior fossa mass and elevated intracranial pressure. Hemangioblastomas predominantly occur sporadically, although 33% of them develop in the setting of VHL disease and, in this circumstance, tend to occur as multiple rather than solitary lesions, oftentimes even at sites within the nervous system distant from the cerebellum.120,122 Otherwise, cerebellar hemangioblastomas can be approached similar to sporadic lesions, with a documented 98% improvement in symptoms and no evidence of recurrence on long-term follow-up.123

VHL disease also predisposes patients to hemangioblastomas of the spinal cord and brainstem. Clinical series have demonstrated that these lesions can be resected safely, with preoperative neurological function serving as the best predictor of postoperative neurological outcome. Factors influencing the decision to proceed with surgery include neurological symptoms or signs, increasing size that might ultimately render the lesion more difficult to resect, or the presence of an enlarging cyst (with brainstem lesions) or an enlarging syrinx (with spinal lesions).124,125 The ultimate goal remains preemptive avoidance of progressive neurological disability from these lesions.

Pheochromocytomas deserve special consideration by the neurosurgeon because they pose a threat of perioperative hypertensive crisis induced by anesthetic or analgesic agents.126 Patients with hemangioblastomas and known or suspected VHL disease should undergo preoperative evaluation with functional testing such as 24-hour urine free cortisol or plasma concentrations of metanephrine and normetanephrine, along with CT, MRI, or radionuclide studies as necessary.127 If evaluation reveals a pheochromocytoma, resection of the lesion should be considered; if resection is prohibitive, preoperative α-blockade—with β-blockade begun only after α-blockade to avoid unopposed α-activity—should proceed to minimize the risk for catecholamine crisis.128

Ataxia-Telangiectasia

Epidemiology and Genetics

Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT), unlike the other neurocutaneous syndromes, exhibits autosomal recessive inheritance. The ATM gene has been linked to chromosome 11q22-23 and encodes the ATM protein kinase, which plays a pivotal role in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks by inducing either DNA repair or apoptotic cell death.129,130 AT patients with a defective ATM protein exhibit DNA double-strand breaks that proliferate in cells and lead to several deleterious effects, including neurodegeneration, immune system dysfunction, sensitivity to ionizing radiation, and proclivity for the development of lymphoid and solid organ malignancies.131,132

AT occurs rarely, in roughly 1 per 40,000 births, but the prevalence of heterozygotes ranges from 0.5% to 2%.133 Homozygotes exhibit drastically shortened life spans, with more than half dying before the age of 20.134 Heterozygotes, too, live 7 to 8 years less than their noncarrier counterparts and suffer from early cancers and ischemic heart disease.135

Diagnosis

AT is manifested in several characteristic ways. Primarily, patients with AT have a propensity for debilitating, progressive cerebellar degeneration resulting in truncal and gait ataxia, which typically occurs by the age of 5 years and renders patients wheelchair bound by their early teens.131 Other neurological signs include oculomotor apraxia and dysarthric speech. AT patients are also subject to characteristic cutaneous and conjunctival telangiectases, which appear at an early age and worsen with exposure to ionizing radiation.

Beyond these clinical findings, diagnosis of this disease can be made on the basis of elevated blood α-fetoprotein levels, cerebellar degeneration on MRI, radiosensitivity testing, or evidence of ATM protein dysfunction on molecular diagnostic testing.133,136

Clinical Features and Management

AT patients have a propensity for the development of multiple cancer types, particularly of the lymphoreticular system. However, CNS lesions have also been linked to AT. Multiple case reports have associated AT with astrocytoma, medulloblastoma, and even craniopharyngioma.137–139 Meningiomas, too, have been shown to have both positive and negative associations with certain ATM haplotypes.132 Recent evidence does not, however, suggest a primary role for the ATM gene in the oncogenesis of medulloblastoma.129

The surgical management of AT-associated intracranial lesions does not necessarily differ from that of sporadic lesions. An important consideration, however, is that the extreme sensitivity of AT patients to ionizing radiation necessitates judicious use of radiation therapy as an adjunctive treatment, with lower than standard dose regimens perhaps optimizing the balance between maximizing effectiveness and minimizing risk.140

Sturge-Weber Syndrome

Epidemiology and Genetics

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), or encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, involves the skin, eyes, and nervous system and hence is classified with the neurocutaneous syndromes. However, it differs substantially from the other syndromes in that it does not have a recognizable genetic contribution and its sufferers do not show an increased propensity for cancer. The reported incidence approaches 1 in 50,000 live births.141 Characteristic findings include leptomeningeal angiomatosis with a tropism for the occipital or parietal lobes, along with an ipsilateral vascular malformation of the face in the V1 or V2 divisions of the trigeminal nerve that appears as a port-wine stain (see Fig. 205-1). Other associated findings may include glaucoma, behavioral or developmental disorders, and seizures and neurological deficits referable to intracranial lesions.141

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SWS hinges on appearance of the typical clinical stigmata, with children normally coming to attention shortly after birth for a unilateral facial port-wine stain; the presence of a port-wine stain, however, implies neither the presence nor the severity of intracranial leptomeningeal angiomatosis because only 8% of facial port-wine stains have this association.142

MRI serves as the “gold standard” modality for the diagnosis of SWS. Critical diagnostic features include leptomeningeal enhancement (the primary finding), along with cerebral atrophy, lack of superficial cortical veins and other venous abnormalities, and evidence of calcification. CT and plain films can also demonstrate calcification and cerebral “tram-tracking.”143

Clinical Features and Management

Epilepsy will affect 75% to 90% of SWS patients and is the primary reason that such patients would need neurosurgical care.143 Roughly 75% of SWS patients will experience seizures before the age of 1 year.144 Patients in whom seizures remain medically refractory may benefit from surgery. Patients with large unilateral intracranial lesions may improve significantly after functional hemispherectomy. A review of 32 reported cases demonstrated an 81% rate of freedom from seizures, with 53% of patients not needing medications; surgery did not appear to worsen hemiparesis or other neurological deficits when compared with the preoperative state.145 Results with simple lesionectomy have not achieved this degree of success, but series have shown a 58% to 65% seizure freedom rate in patients amenable to this approach.146,147 Controversy still remains regarding the optimal timing of surgery; some authors argue that early surgery might preempt the cognitive deficits that can result from chronic, intractable epilepsy, whereas others suggest that early surgery might subject some patients to the risks associated with surgery who might otherwise attain a relatively normal developmental trajectory.143

Baser ME, Evans DGR, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis 2. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:27.

Baser ME, Friedman JM, Aeschliman D, et al. Predictors of the risk of mortality in neurofibromatosis 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:715.

Buccoliero AM, Franchi A, Castiglione F, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA): is it an astrocytoma? Morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Neuropathology. 2009;29:25.

Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345.

Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Cerminara C. Current management for epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:119.

de Ribaupierre S, Dorfmuller G, Bulteau C, et al. Subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in pediatric tuberous sclerosis disease: when should we operate? Neurosurgery. 2007;60:83.

Di Rocco C, Tamburrini G. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:909.

Frappart PO, McKinnon PJ. Ataxia-telangiectasia and related diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:495.

Friedman JM. Epidemiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:1.

Goh S, Butler W, Thiele EA. Subependymal giant cell tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2004;63:1457.

Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, et al. Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1.

Jagannathan J, Lonser RR, Smith R, et al. Surgical management of cerebellar hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:210.

Korf BR. Plexiform neurofibromas. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:31.

Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059.

Lonser RR, Weil RJ, Wanebo JE, et al. Surgical management of spinal cord hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:106.

Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, et al. NIH conference. Neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:39.

Myklejord DJ. Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: the anesthesiologist nightmare. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:59.

Opocher E, Kremer LC, Da Dalt L, et al. Prognostic factors for progression of childhood optic pathway glioma: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1807.

Pollack IF, Shultz B, Mulvihill JJ. The management of brainstem gliomas in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neurology. 1996;46:1652.

Poyhonen M, Niemela S, Herva R. Risk of malignancy and death in neurofibromatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:139.

Roach ES, Sparagana SP. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:643.

Ruttledge MH, Andermann AA, Phelan CM, et al. Type of mutation in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene (NF2) frequently determines severity of disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:331.

1 Friedman JM. Epidemiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:1.

2 Crowe FSJ, Need J. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1956.

3 North K. Neurofibromatosis type 1: review of the first 200 patients in an Australian clinic. J Child Neurol. 1993;8:395.

4 Poyhonen M, Niemela S, Herva R. Risk of malignancy and death in neurofibromatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:139.

5 Li Y, O’Connell P, Breidenbach HH, et al. Genomic organization of the neurofibromatosis 1 gene (NF1). Genomics. 1995;25:9.

6 Jenne DE, Tinschert S, Dorschner MO, et al. Complete physical map and gene content of the human NF1 tumor suppressor region in human and mouse. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:111.

7 Gutmann DH, Wood DL, Collins FS. Identification of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9658.

8 Ahmadian MR, Wiesmuller L, Lautwein A, et al. Structural differences in the minimal catalytic domains of the GTPase-activating proteins p120GAP and neurofibromin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16409.

9 Mittal R, Ahmadian MR, Goody RS, et al. Formation of a transition-state analog of the Ras GTPase reaction by Ras-GDP, tetrafluoroaluminate, and GTPase-activating proteins. Science. 1996;273:115.

10 Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, et al. Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1.

11 Viskochil D. The Structure and Function of the NF1 Gene: Molecular Pathophysiology. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999.

12 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13-15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1:172.

13 Ilgren EB, Kinnier-Wilson LM, Stiller CA. Gliomas in neurofibromatosis: a series of 89 cases with evidence for enhanced malignancy in associated cerebellar astrocytomas. Pathol Annu. 1985;20:331.

14 Lewis RA, Gerson LP, Axelson KA, et al. von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. II. Incidence of optic gliomata. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:929.

15 McGaughran JM, Harris DI, Donnai D, et al. A clinical study of type 1 neurofibromatosis in north west England. J Med Genet. 1999;36:197.

16 Sanguinetti C, Greco F, De Palma L, et al. The ultrastructure of peripheral neurofibroma: the role of mast cells and their interaction with perineurial cells. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1992;18:207.

17 Sanguinetti C, Greco F, de Palma L, et al. The ultrastructure of schwannoma and neurofibroma of the peripheral nerves. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1991;17:237.

18 Korf BR. Plexiform neurofibromas. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:31.

19 Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. A clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111:1355.

20 Tonsgard JH, Kwak SM, Short MP, et al. CT imaging in adults with neurofibromatosis-1: frequent asymptomatic plexiform lesions. Neurology. 1998;50:1755.

21 Craig JB, Govender S. Neurofibromatosis of the cervical spine. A report of eight cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:575.

22 Leonard JR, Ferner RE, Thomas N, et al. Cervical cord compression from plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1404.

23 Lot G, George B. Cervical neuromas with extradural components: surgical management in a series of 57 patients. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:813.

24 Pollack IF, Colak A, Fitz C, et al. Surgical management of spinal cord compression from plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:248.

25 Ward BA, Harkey HL, Parent AD, et al. Severe cervical kyphotic deformities in patients with plexiform neurofibromas: case report. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:960.

26 McCaughan JA, Holloway SM, Davidson R, et al. Further evidence of the increased risk for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour from a Scottish cohort of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:463.

27 Leroy K, Dumas V, Martin-Garcia N, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 17 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:908.

28 Friedrich RE, Hartmann M, Mautner VF. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) in NF1-affected children. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1957.

29 Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189.

30 Farmer JP, Khan S, Khan A, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and the pediatric neurosurgeon: a 20-year institutional review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:122.

31 Leonard JR, Perry A, Rubin JB, et al. The role of surgical biopsy in the diagnosis of glioma in individuals with neurofibromatosis-1. Neurology. 2006;67:1509.

32 Astrup J. Natural history and clinical management of optic pathway glioma. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17:327.

33 Czyzyk E, Jozwiak S, Roszkowski M, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in children with and without neurofibromatosis 1. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:471.

34 Deliganis AV, Geyer JR, Berger MS. Prognostic significance of type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease) in childhood optic glioma. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:1114.

35 Garvey M, Packer RJ. An integrated approach to the treatment of chiasmatic-hypothalamic gliomas. J Neurooncol. 1996;28:167.

36 Grill J, Laithier V, Rodriguez D, et al. When do children with optic pathway tumours need treatment? An oncological perspective in 106 patients treated in a single centre. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:692.

37 Janss AJ, Grundy R, Cnaan A, et al. Optic pathway and hypothalamic/chiasmatic gliomas in children younger than age 5 years with a 6-year follow-up. Cancer. 1995;75:1051.

38 Listernick R, Darling C, Greenwald M, et al. Optic pathway tumors in children: the effect of neurofibromatosis type 1 on clinical manifestations and natural history. J Pediatr. 1995;127:718.

39 Perilongo G, Moras P, Carollo C, et al. Spontaneous partial regression of low-grade glioma in children with neurofibromatosis-1: a real possibility. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:352.

40 Singhal S, Birch JM, Kerr B, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and sporadic optic gliomas. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:65.

41 Stern J, DiGiacinto GV, Housepian EM. Neurofibromatosis and optic glioma: clinical and morphological correlations. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:524.

42 Opocher E, Kremer LC, Da Dalt L, et al. Prognostic factors for progression of childhood optic pathway glioma: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1807.

43 Lee AG. Neuroophthalmological management of optic pathway gliomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E1.

44 Liu GT. Optic gliomas of the anterior visual pathway. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:427.

45 Serdaroglu A, Simsek F, Gucuyener K, et al. Moyamoya syndrome after radiation therapy for optic pathway glioma: case report. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:765.

46 Piccirilli M, Lenzi J, Delfinis C, et al. Spontaneous regression of optic pathways gliomas in three patients with neurofibromatosis type I and critical review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1332.

47 Cohen ME, Duffner PK, Heffner RR, et al. Prognostic factors in brainstem gliomas. Neurology. 1986;36:602.

48 Molloy PT, Bilaniuk LT, Vaughan SN, et al. Brainstem tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: a distinct clinical entity. Neurology. 1995;45:1897.

49 Pollack IF, Shultz B, Mulvihill JJ. The management of brainstem gliomas in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neurology. 1996;46:1652.

50 Ullrich NJ, Raja AI, Irons MB, et al. Brainstem lesions in neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:762.

51 Vinchon M, Soto-Ares G, Ruchoux MM, et al. Cerebellar gliomas in children with NF1: pathology and surgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16:417.

52 Dunn IF, Agarwalla PK, Papanastassiou AM, et al. Multiple pilocytic astrocytomas of the cerebellum in a 17-year-old patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:1191.

53 Naidich MJ, Walker MT, Gottardi-Littell NR, et al. Cerebellar pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:825.

54 Saikali S, Le Strat A, Heckly A, et al. Multicentric pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:376.

55 Pollack IF, Mulvihill JJ. Special issues in the management of gliomas in children with neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurooncol. 1996;28:257.

56 Bawden H, Dooley J, Buckley D, et al. MRI and nonverbal cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis 1. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1996;18:784.

57 Moore BD, Slopis JM, Schomer D, et al. Neuropsychological significance of areas of high signal intensity on brain MRIs of children with neurofibromatosis. Neurology. 1996;46:1660.

58 Carella A, Medicamento N. Malignant evolution of presumed benign lesions in the brain in neurofibromatosis: case report. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:639.

59 Hsieh HY, Wu T, Wang CJ, et al. Neurological complications involving the central nervous system in neurofibromatosis type 1. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2007;16:68.

60 Martinez-Lage JF, Salcedo C, Corral M, et al. Medulloblastomas in neurofibromatosis type 1. Case report and literature review. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2002;13:128.

61 Rosser TL, Vezina G, Packer RJ. Cerebrovascular abnormalities in a population of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology. 2005;64:553.

62 Baldauf J, Kiwit J, Synowitz M. Cerebral aneurysms associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Neurol India. 2005;53:213.

63 Zhao JZ, Han XD. Cerebral aneurysm associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis: a case report. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:592.

64 Conway JE, Hutchins GM, Tamargo RJ. Lack of evidence for an association between neurofibromatosis type I and intracranial aneurysms: autopsy study and review of the literature. Stroke. 2001;32:2481.

65 Evans DG, Huson SM, Donnai D, et al. A genetic study of type 2 neurofibromatosis in the United Kingdom. I. Prevalence, mutation rate, fitness, and confirmation of maternal transmission effect on severity. J Med Genet. 1992;29:841.

66 Mautner VF, Lindenau M, Baser ME, et al. Skin abnormalities in neurofibromatosis 2. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1539.

67 Rouleau GA, Merel P, Lutchman M, et al. Alteration in a new gene encoding a putative membrane-organizing protein causes neuro-fibromatosis type 2. Nature. 1993;363:515.

68 Rouleau GA, Wertelecki W, Haines JL, et al. Genetic linkage of bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis to a DNA marker on chromosome 22. Nature. 1987;329:246.

69 Rubinstein LJ. The malformative central nervous system lesions in the central and peripheral forms of neurofibromatosis. A neuropathological study of 22 cases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:14.

70 Baser ME, Kuramoto L, Joe H, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations for nervous system tumors in neurofibromatosis 2: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:231.

71 Bourn D, Carter SA, Mason S, et al. Germline mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 tumour suppressor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:813.

72 Ruttledge MH, Andermann AA, Phelan CM, et al. Type of mutation in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene (NF2) frequently determines severity of disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:331.

73 Watson CJ, Gaunt L, Evans G, et al. A disease-associated germline deletion maps the type 2 neurofibromatosis (NF2) gene between the Ewing sarcoma region and the leukaemia inhibitory factor locus. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:701.

74 Curto M, McClatchey AI. Nf2/Merlin: a coordinator of receptor signalling and intercellular contact. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:256.

75 Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, et al. NIH conference. Neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:39.

76 Baser ME, Friedman JM, Wallace AJ, et al. Evaluation of clinical diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis 2. Neurology. 2002;59:1759.

77 Baser ME, Friedman JM, Aeschliman D, et al. Predictors of the risk of mortality in neurofibromatosis 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:715.

78 Otsuka G, Saito K, Nagatani T, et al. Age at symptom onset and long-term survival in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:480.

79 Evans DG, Huson SM, Donnai D, et al. A clinical study of type 2 neurofibromatosis. Q J Med. 1992;84:603.

80 Mautner VF, Lindenau M, Baser ME, et al. The neuroimaging and clinical spectrum of neurofibromatosis 2. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:880.

81 Parry DM, Eldridge R, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, et al. Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2): clinical characteristics of 63 affected individuals and clinical evidence for heterogeneity. Am J Med Genet. 1994;52:450.

82 Abaza MM, Makariou E, Armstrong M, et al. Growth rate characteristics of acoustic neuromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 2. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:694.

83 Baser ME, Makariou EV, Parry DM. Predictors of vestibular schwannoma growth in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:217.

84 Baser ME, Mautner VF, Parry DM, et al. Methodological issues in longitudinal studies: vestibular schwannoma growth rates in neurofibromatosis 2. J Med Genet. 2005;42:903.

85 Mautner VF, Baser ME, Thakkar SD, et al. Vestibular schwannoma growth in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: a longitudinal study. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:223.

86 Slattery WH3rd, Fisher LM, Iqbal Z, et al. Vestibular schwannoma growth rates in neurofibromatosis type 2 natural history consortium subjects. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:811.

87 Baser ME, Evans DG, Jackler RK, et al. Neurofibromatosis 2, radiosurgery and malignant nervous system tumours. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:998.

88 Evans DG, Birch JM, Ramsden RT, et al. Malignant transformation and new primary tumours after therapeutic radiation for benign disease: substantial risks in certain tumour prone syndromes. J Med Genet. 2006;43:289.

89 Rowe J, Grainger A, Walton L, et al. Safety of radiosurgery applied to conditions with abnormal tumor suppressor genes. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:860.

90 Thomsen J, Mirz F, Wetke R, et al. Intracranial sarcoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 2 treated with gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Am J Otol. 2000;21:364.

91 Bouzas EA, Freidlin V, Parry DM, et al. Lens opacities in neurofibromatosis 2: further significant correlations. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:354.

92 Antinheimo J, Haapasalo H, Haltia M, et al. Proliferation potential and histological features in neurofibromatosis 2–associated and sporadic meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:610.

93 Dow G, Biggs N, Evans G, et al. Spinal tumors in neurofibromatosis type 2. Is emerging knowledge of genotype predictive of natural history? J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:574.

94 Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:125.

95 Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 1993;75:1305.

96 Fryer AE, Chalmers A, Connor JM, et al. Evidence that the gene for tuberous sclerosis is on chromosome 9. Lancet. 1987;1:659.

97 van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805.

98 Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151.

99 Tee AR, Anjum R, Blenis J. Inactivation of the tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products occurs by phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt-dependent and -independent phosphorylation of tuberin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37288.

100 Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13571.

101 Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1259.

102 van Slegtenhorst M, Nellist M, Nagelkerken B, et al. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1053.

103 Osborne JP, Merrifield J, O’Callaghan FJ. Tuberous sclerosis: what’s new? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:728-731.

104 Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189.

105 Jozwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:911.

106 Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345.

107 Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624.

108 Roach ES, Sparagana SP. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:643.

109 Shepherd CW, Gomez MR, Lie JT, et al. Causes of death in patients with tuberous sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:792.

110 Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Cerminara C. Current management for epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:119.

111 Goh S, Butler W, Thiele EA. Subependymal giant cell tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2004;63:1457.

112 Shepherd CW, Scheithauer BW, Gomez MR, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: a clinical, pathological, and flow cytometric study. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:864.

113 Cuccia V, Zuccaro G, Sosa F, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in children with tuberous sclerosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:232.

114 de Ribaupierre S, Dorfmuller G, Bulteau C, et al. Subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in pediatric tuberous sclerosis disease: when should we operate? Neurosurgery. 2007;60:83.

115 Fujiwara S, Takaki T, Hikita T, et al. Subependymal giant-cell astrocytoma associated with tuberous sclerosis. Do subependymal nodules grow? Childs Nerv Syst. 1989;5:43.

116 Buccoliero AM, Franchi A, Castiglione F, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA): is it an astrocytoma? Morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Neuropathology. 2009;29:25.

117 Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:680.

118 Jansen FE, van Huffelen AC, Algra A, et al. Epilepsy surgery in tuberous sclerosis: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1477.

119 Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260:1317.

120 Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059.

121 Maher ER, Iselius L, Yates JR, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: a genetic study. J Med Genet. 1991;28:443.

122 Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77:1151.

123 Jagannathan J, Lonser RR, Smith R, et al. Surgical management of cerebellar hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:210.

124 Lonser RR, Weil RJ, Wanebo JE, et al. Surgical management of spinal cord hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:106.

125 Weil RJ, Lonser RR, DeVroom HL, et al. Surgical management of brainstem hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:95.

126 Gurunathan U, Korula G. Unsuspected pheochromocytoma: von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2004;16:26.

127 Eisenhofer G, Lenders JW, Linehan WM, et al. Plasma normetanephrine and metanephrine for detecting pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1872.

128 Myklejord DJ. Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: the anesthesiologist nightmare. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:59.

129 Liberzon E, Avigad S, Cohen IJ, et al. ATM gene mutations are not involved in medulloblastoma in children. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;146:167.

130 Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, et al. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science. 1995;268:1749.

131 Frappart PO, McKinnon PJ. Ataxia-telangiectasia and related diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:495.

132 Malmer BS, Feychting M, Lonn S, et al. Genetic variation in p53 and ATM haplotypes and risk of glioma and meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:229.

133 Chun HH, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA Repair (Amst). 2004;3:1187.

134 Morrell D, Cromartie E, Swift M. Mortality and cancer incidence in 263 patients with ataxia-telangiectasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:89.

135 Su Y, Swift M. Mortality rates among carriers of ataxia-telangiectasia mutant alleles. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:770.

136 Perlman S, Becker-Catania S, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2003;10:173.

137 Groot-Loonen JJ, Slater R, Taminiau J, et al. Three consecutive primary malignancies in one patient during childhood. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1988;5:287.

138 Masri AT, Bakri FG, Al-Hadidy AM, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia complicated by craniopharyngioma—a new observation. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:287.

139 Miyagi K, Mukawa J, Kinjo N, et al. Astrocytoma linked to familial ataxia-telangiectasia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;135:87.

140 Hart RM, Kimler BF, Evans RG, et al. Radiotherapeutic management of medulloblastoma in a pediatric patient with ataxia telangiectasia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1237.

141 Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:303.

142 Tallman B, Tan OT, Morelli JG, et al. Location of port-wine stains and the likelihood of ophthalmic and/or central nervous system complications. Pediatrics. 1991;87:323.

143 Di Rocco C, Tamburrini G. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:909.

144 Sujansky E, Conradi S. Sturge-Weber syndrome: age of onset of seizures and glaucoma and the prognosis for affected children. J Child Neurol. 1995;10:49.

145 Kossoff EH, Buck C, Freeman JM. Outcomes of 32 hemispherectomies for Sturge-Weber syndrome worldwide. Neurology. 2002;59:1735.

146 Arzimanoglou AA, Andermann F, Aicardi J, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome: indications and results of surgery in 20 patients. Neurology. 2000;55:1472.

147 Bourgeois M, Crimmins DW, de Oliveira RS, et al. Surgical treatment of epilepsy in Sturge-Weber syndrome in children. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:20.