Chapter 20 Percutaneous biopsy

Biopsy Overview

Image-guided needle biopsy is the mainstay for diagnosis of nonpalpable masses almost anywhere in the body. The indications for biopsy continue to evolve, and although percutaneous biopsy of a given mass is possible, it may not be indicated (Thompson et al, 1985). As with any invasive procedure, percutaneous biopsy has associated risks that should be weighed prior to the procedure. Needle biopsy is warranted when the result of the biopsy would potentially affect patient management. These indications include confirmation of preoperative diagnosis, documentation of primary or metastatic disease in patients who are not surgical candidates, evaluation of organ dysfunction, and sampling for special studies such as receptor or gene mutation status.

Biopsy Technique

Fine Needle Aspiration

A 25- to 20-gauge needle is advanced into the target lesion, and real-time (ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or CT fluoroscopy) or interrupted imaging (conventional CT or MRI) is performed to guide and assess needle position. Coaxial techniques are sometimes useful but are generally unnecessary, but some operators are partial to this technique. Although coaxial biopsy requires the introduction of a larger needle than is used for biopsy, it has the advantage that multiple samples may be obtained without creating a new tract for each pass, and the tract can be embolized or “plugged” to prevent hemorrhage in high-risk situtations (Billich et al, 2008).

In the ideal situation, an on-site cytopathologist or cytotechnologist can provide an immediate interpretation of the sample; this has been shown to increase the sensitivity of the biopsy, shorten the procedure time, and minimize the number of passes required to obtain a diagnostic specimen (Nasuti et al, 2002; Silverman et al, 1989).

Core Biopsy

Despite the fact that more tissue is usually obtained during a core needle biopsy than with a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, the diagnostic rates for most malignancies are not necessarily higher (Longchampt et al, 2000; Stewart et al, 2002). The incremental benefit of a core biopsy in the liver is most notable in the discrimination of a well-differentiated HCC from nodular regeneration in the setting of cirrhosis and in confirmation of benign diagnoses, including hemangioma, adenoma, and focal nodular hyperplasia (Kulesza et al, 2004; Kuo et al, 2004).

Imaging Guidance

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US; see Chapter 13) is commonly used to guide percutaneous biopsies of the liver, because it is widely available, inexpensive, and portable. US may be used at the bedside or in patients in whom CT guidance is impractical. Lesions larger than 1 cm are often visible, and US allows for real-time visualization of the needle as it courses from the skin into the lesion. This is especially helpful in small lesions that move with respiration and are difficult to target with interrupted imaging modalities. Visualization of smaller caliber needles may be difficult, and many manufacturers make needles specially designed to enhance visibility with US.

Computed Tomography

CT (see Chapter 16) is a common modality for guiding percutaneous biopsies, because it provides superb anatomic detail that gives the operator the ability to plan a path from skin to lesion using the safest approach, clearly visualizing interposed structures. CT is the imaging modality of choice for biopsies of the pancreas, adrenal glands, abdominal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and bone and liver lesions that are not well visualized with US, or when biopsy is performed by operators who are not skilled with US. CT is also commonly used for lung lesions, although at our institution, fluoroscopy is preferred by some operators to capitalize on the real-time visualization of the target in the moving background of the lung.

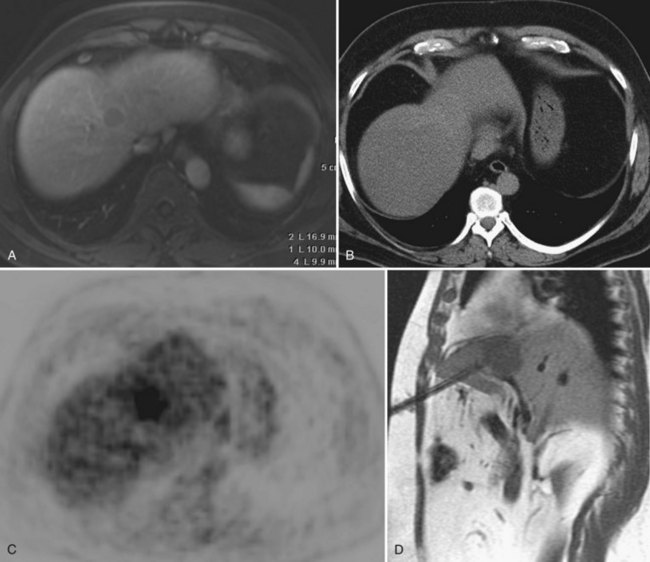

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Biopsies guided by MRI (see Chapter 17) have been made possible by the advent of open-bore MRI systems that provide access to patients during imaging and the availability of nonferrous biopsy needles and monitoring equipment. The superior contrast resolution of MR allows for targeting of lesions that are difficult to visualize with US and noncontrast CT, and the ability of MRI to image in any plane enhances the targeting of lesions that are not safe to approach or easy to access in the axial plane (Stattaus et al, 2008; Fig. 20.1). Owing to high cost and limited availability, MR-guided biopsies are generally reserved for patients whose lesion cannot be seen or targeted with US or CT. In addition, it is necessary to ensure that nonferromagnetic, MRI-compatible equipment is on hand and that the patient is able to undergo MRI.

Fluoroscopy

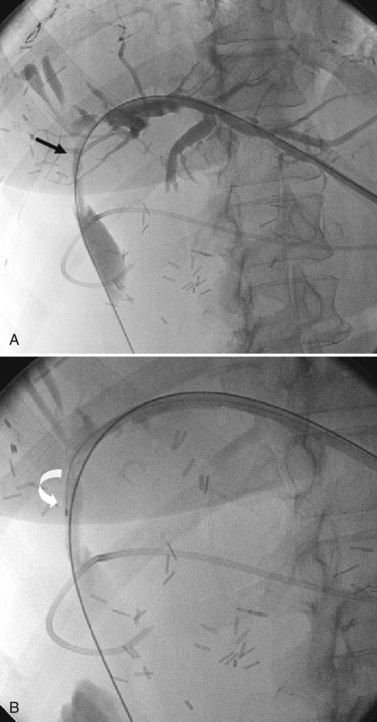

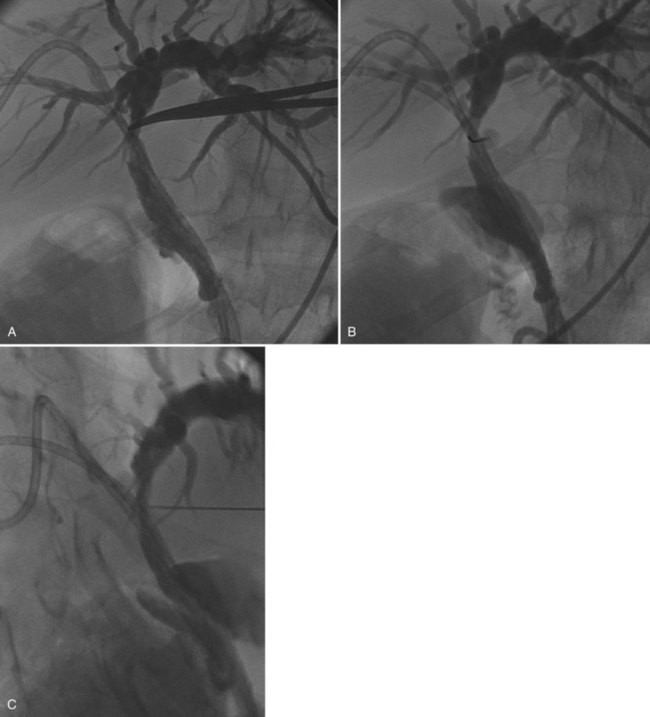

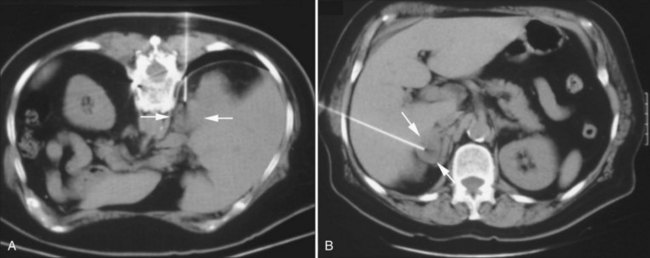

Fluoroscopy is useful for guiding bile duct biopsies. Benign and malignant biliary strictures (see Chapter 18, Chapter 42A, Chapter 42B, Chapter 50A, Chapter 50B, Chapter 50C, Chapter 50D ) often have similar cholangiographic appearances and rarely can be distinguished based on imaging alone (Hadjis et al, 1985; Corvera et al, 2005). Lesions originating within the duct may be sampled by either an endoluminal (see Chapter 14) or a direct percutaneous approach (see Chapter 18). Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage allows direct access to the biliary tract for endoluminal biopsy, when satisfactory decompression of the biliary tree has been achieved. Biopsy forceps or brush-biopsy catheters can be used through the existing tract to obtain tissue samples of suspicious areas (Fig. 20.2). The sensitivity of forceps biopsy is in the range of 40% to 80%, higher than that of brush biopsy, which is in the range of 30% to 60%. Specificity for each approaches 98% (Stewart et al, 2001; Govil et al, 2002; Weber et al, 2008), and sensitivity is highest for intraductal lesions and when biopsy is done in conjunction with choledochoscopy to provide direct visualization of the lesion (Ponchon et al, 1996).

Alternatively, after the biliary tree is opacified, a direct percutaneous biopsy of a bile duct lesion may be targeted with fluoroscopy using a transhepatic approach (see Chapter 18; Chawla et al, 1989). This technique is most useful for intrinsic bile duct lesions but may also be used to diagnose lesions adjacent to the bile duct. With this technique, contrast is injected into an indwelling biliary drainage catheter to delineate the targeted bile duct abnormality. A needle is advanced through the anterior abdomen to the lesion, and a specimen is obtained. Confirmation of accurate needle position is made by obtaining oblique fluoroscopic images and by real-time fluoroscopy, when the needle is seen to move the duct or the indwelling catheter or both (Fig. 20.3). Fluoroscopy also is useful to guide percutaneous biopsy of lung nodules and for nontargeted transvenous biopsies of the liver or kidney.

New Guidance Equipment

New technology is being developed that allows fusion of multiple modalities. For example, CT and MRI scans can be overlaid with real-time US images to achieve the clarity of the one imaging modality and the real-time visualization capabilities of the other. PET images (see Chapter 15) also can be fused to demonstrate sites of highest metabolic activity. Additionally, robotic guidance systems have been piloted in an effort to optimize speed and accuracy of needle placement.

Biopsy of Specific Sites

Liver Biopsy

Percutaneous liver biopsy is performed to determine the nature of focal liver masses, the cause and extent of cirrhosis, or the cause of liver dysfunction (see Chapter 64, Chapter 65, Chapter 70A, Chapter 70B ). Modern cross-sectional imaging techniques—including ultrasound, CT, and MRI—allow percutaneous biopsy of both subcentimeter and deep lesions to be performed on an outpatient basis with minimal morbidity. With current techniques, almost any liver lesion can be targeted percutaneously; most liver lesions larger than 5 mm are suitable for biopsy (Yu et al, 2001). Fine needle biopsy of liver lesions has a sensitivity of 69% to 97% (Ohlsson et al, 2002).

Focal Liver Lesions

Focal liver lesions may be solitary or multiple. For a solitary lesion, several benign conditions—cyst, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, and adenoma—often can be diagnosed confidently by high-quality cross-sectional imaging, obviating the need for biopsy (see Chapter 16, Chapter 17, Chapter 79A, Chapter 79B ; Gibbs et al, 2004; Hussain et al, 2004; Kim et al, 2004). These diagnoses should be considered in all solitary liver lesions, unless they are known to be new in the setting of a known cancer or in patients at risk for primary HCC.

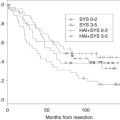

HCC may also be diagnosed based on imaging and clinical criteria. In patients with cirrhosis and an arterial enhancing liver mass greater than 2 cm, an α-fetoprotein value of greater than 400, or two concordant imaging studies diagnostic of HCC, biopsy is generally unnecessary (Bruix et al, 1981). When the diagnosis of HCC is considered, and these criteria are not met, the diagnosis often can be established based on cytology alone. Smaller, encapsulated tumors are more likely to be well differentiated, and tissue cores may be required to distinguish a well-differentiated tumor from normal or cirrhotic liver. Because of the risk of tumor seeding in the biopsy tract for a lesion highly suspicious for HCC (Chaudhry et al, 2004; Perkins, 2007; Durand et al, 2007), when a curative treatment is possible, biopsy should be performed only after consultation with a hepatobiliary surgeon and after referencing the most current imaging and clinical criteria.

Liver Parenchyma Biopsy

Core liver biopsy is used to grade and stage liver disease in patients with abnormal liver function studies, chronic hepatitis, and known or suspected cirrhosis (see Chapter 64, Chapter 65, Chapter 70A, Chapter 70B ). Gastroenterologists have historically performed most liver biopsies without imaging guidance; however, unusual anatomy occasionally makes imaging-guided biopsy advisable. Adequate tissue cores can be obtained with needles 20 gauge and larger, although needles 18 gauge and larger provide a more generous specimen for analysis (Guido & Ruggae, 2004; Maharaj et al, 1986).

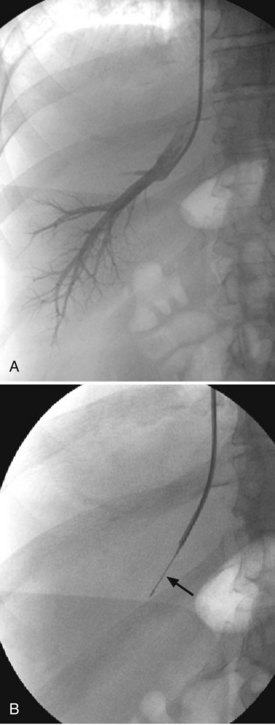

Transvenous Biopsy

Transjugular liver biopsy is a useful alternative to percutaneous biopsy in patients with coagulopathy or when hepatic venous pressure measurements are required (Sawyerr et al, 1993; Garcia-Compean & Cortes, 2004). Although transvenous biopsy is seemingly more invasive than percutaneous biopsy, the risk of significant bleeding in coagulopathic patients is minimized using a transvenous approach, because bleeding from the biopsy site tracks back into the venous circulation and not into the abdominal cavity, as can happen with percutaneous biopsies. Proper technique to avoid puncture of the liver capsule is crucial to optimize safety.

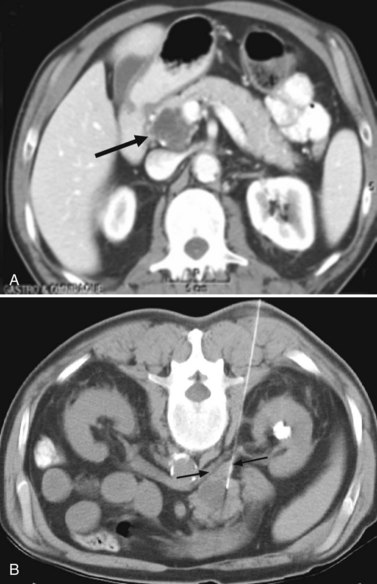

In this technique, a venous sheath is introduced into a hepatic vein, most commonly the right hepatic vein, from a right internal jugular approach. Pressure measurements may be obtained to evaluate the source (presinusoidal, sinusoidal, or postsinusoidal) and degree of portal hypertension. A core biopsy needle or biopsy forceps is introduced through the sheath into the liver parenchyma to obtain histologic samples (Fig. 20.4). Care must be taken to avoid performing the biopsy from a peripheral approach, because this increases the risk that the liver capsule will be punctured and that peritoneal hemorrhage will result.

Transvenous biopsy is only used for nontargeted parenchymal biopsy; it cannot be used for biopsy of a focal lesion. Transvenous biopsy of the kidney also has been reported and may be useful for evaluation of renal dysfunction in coagulopathic patients (Cluzel et al, 2000). This may be particularly convenient in coagulopathic patients who require both parenchymal hepatic and renal biopsies.

Biopsy of Other Organs

Adrenal Biopsy

The adrenal gland is a common site of metastatic disease. This gland also is the site of many benign neoplasms, and adenomas occur in 5% of individuals (Abecassis et al, 1985; Libe et al, 2002). Adrenal biopsy can often be avoided, as MRI can sometimes distinguish between an adenoma and a metastasis (National Institutes of Health, 2002). In some cases, the mass remains indeterminate, and biopsy is indicated. Because of the posterior approach used for all left and some right adrenal biopsies, it is common to traverse the lung, introducing the possibility of a pneumothorax. The right adrenal gland can alternatively be targeted from a lateral, transhepatic approach to eliminate the risk of pneumothorax (Fig. 20.5).

Pancreas Biopsy

Despite the best efforts of clinicians and advances in imaging, most patients with pancreatic cancer still initially present with unresectable disease. Needle biopsy may be requested for tissue diagnosis so that treatment can be initiated, and it is essential to evaluate the preprocedure imaging carefully to determine the safest approach. An anterior approach to the pancreas may be difficult because of interposed colon, spleen, or mesenteric vessels, which we would prefer not to traverse. We often prefer a posterior, transcaval approach (Sofocleous et al, 2004) or a transhepatic approach, particularly for lesions in the head or uncinate process (Fig. 20.6).

Lung and Mediastinum Biopsy

Lung biopsies can be performed with CT, CT fluoroscopy, or conventional fluoroscopy, but they are often easiest and fastest with conventional fluoroscopy. The size, location, and nature of the target lesion, as well as operator experience, determine which modality is used. Mediastinal biopsies are usually performed using CT guidance. The size of the needle used and type of specimen acquired vary depending on the clinical indication. Diagnostic rates for needle biopsy of malignant lung lesions have been reported as greater than 90% (Swischuk et al, 1998).

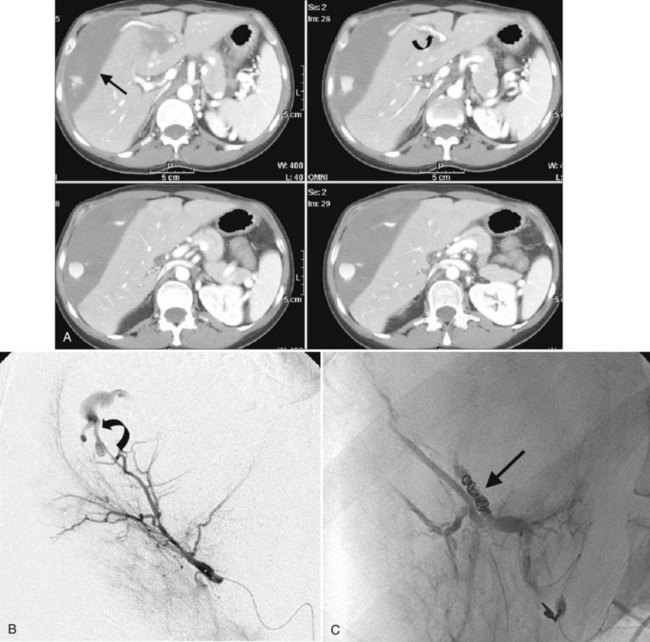

Complications of Percutaneous Biopsy

The risk of significant bleeding after liver biopsy is less than 1% (Piccinino et al, 1986; Riemann et al, 2000). In most cases, the bleeding is self-limited, and conservative management comprising observation and hydration is sufficient. In patients with more significant bleeding, hepatic angiography and potential embolization of an injured artery may be required (Fig. 20.7). Some authors advocate placing absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) pledgets in the biopsy tract through the needle after core biopsy, but this has not been shown definitively to decrease the risk of major bleeding (Hatfield, 2008).

Pain out of proportion to imaging findings after liver biopsy may be due to bile peritonitis (Ruben & Chopra, 1987). Care should be taken to minimize needle passes through the gallbladder, cystic duct, or dilated bile ducts. If the gallbladder is inadvertently punctured, it should be aspirated as completely as possible before removing the needle. Bile leaks resulting in discernible collections are rare after liver biopsy in the absence of downstream biliary obstruction.

Adrenal masses and lesions in the dome of the liver often require an approach for biopsy that crosses the lung base, putting patients at risk for pneumothorax. The two most common complications after lung biopsy include hemoptysis and pneumothorax (Westcott et al, 1997). Hemoptysis occurs in up to 30% of lung biopsies and is usually self-limited, but it can be frightening to the patient. Pneumothorax occurs in 20% to 30% of patients after biopsy and requires placement of a chest tube in approximately 6% of cases. The risk of pneumothorax is typically related more to patient than technical factors, although depth of the target lesion, number of pleural surfaces transgressed, and patient positioning (prone positioning decreases the risk of pneumothorax) have been shown to affect the likelihood. Elderly patients and patients with underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are more prone to developing a pneumothorax requiring treatment (Covey et al, 2004). A symptomatic or enlarging pneumothorax is treated with a small-bore chest tube (generally 8 to 12 Fr) and occasionally necessitates hospital admission.

Hemorrhagic pericardial tamponade is a rare, potentially life-threatening complication after mediastinal biopsy (Kucharczyk et al, 1982). Although hypoxemia may be a feature, this complication can be distinguished from iatrogenic pneumothorax clinically by the development of hypotension with narrowing of the pulse pressure and diminished amplitude of the electrocardiogram complex on the monitor. The diagnosis can be confirmed immediately by scanning the heart and pericardium, and it can be treated by directly placing a drainage catheter into the pericardial space.

Needle-tract seeding after percutaneous biopsy is a worrisome complication. The interval between biopsy and appearance of a tract metastasis is 6 to 24 months (Kosugi et al, 2004; Schotman et al, 1999). The risk overall is likely greater than reported, but current understanding is that the risk in HCC is in the range of 2% to 3% (Perkins, 2007; Stigliano et al, 2007). Although the incidence is relatively small, the possibility of rendering a patient ultimately incurable because of tract or peritoneal seeding should be considered in the risk/benefit analysis for each patient. For this reason, some surgeons do not advocate percutaneous biopsy for patients with potentially resectable lesions highly suspicious for malignancy (Cha et al, 2002; Al-Leswas et al, 2008); this sentiment is particularly strong among transplant surgeons in regard to patients with HCC or other malignant disease undergoing evaluation for a new liver graft (see Chapters 97D and 97E).

Conclusion

Percutaneous needle biopsy is a well-established and safe diagnostic tool, and it is an important instrument in the diagnosis of tumors, for determining the cause of organ dysfunction staging, and for documenting recurrent or metastatic disease. Complications occur infrequently, and most are easily treated or self-limiting. Tract seeding has been reported but occurs infrequently. There is no such thing as a “negative” biopsy (Phillips et al, 1998). If a diagnosis of malignancy is not made, a specific benign diagnosis needs to be confirmed. If nonspecific findings are evident on cytology—including inflammatory or reactive changes, fibrous tissue, or normal site tissue—or if atypical cells are present, another biopsy should be performed, or the lesion should be closely followed up, depending on the pretest probability of disease.

Abecassis M, et al. Serendipitous adrenal masses: prevalence, significance and management. Am J Surg. 1985;149:783-788.

Al-Leswas D, et al. Biopsy of solid liver tumors: adverse consequences. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7(3):325-327.

Billich C, et al. CT-guided lung biopsy: incidence of pneumothorax after instillation of NaCl into the biopsy track. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(6):1146-1152.

Bruix J, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona 2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 1981;35(3):421-430.

Cha C, et al. Surgery and ablative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(Suppl 2):S130-S137.

Chaudhry SI, et al. Preoperative biopsy of hepatocellular carcinoma renders 1 in 5 operable cases incurable (abstract). Br J Surg. 2004;91(Suppl 1):103.

Chawla S, et al. Cholangiographically guided aspiration cytology in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1989;8:95-96.

Cluzel P, et al. Transjugular versus percutaneous renal biopsy for the diagnosis of parenchymal disease: comparison of sampling effectiveness and complications. Radiology. 2000;215:689-693.

Corvera CU, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of proximal biliary strictures masquerading as hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:862-869.

Covey AM, et al. Factors associated with pneumothorax following percutaneous lung biopsy in 443 consecutive patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:479-483.

Durand F, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: role of biopsy. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:S17-S23.

Garcia-Compean D, Cortes C. Transjugular liver biopsy: an update. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:100-103.

Gibbs JF, et al. Contemporary management of benign liver tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:463-480.

Govil H, et al. Brush cytology of the biliary tract: retrospective study of 278 cases with histopathologic correlation. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:273-277.

Guido M, Ruggae M. Liver biopsy sampling in chronic viral hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:89-97.

Hadjis NS, Collier NA, Blumgart LH. Malignant masquerade at the hilum of the liver. Br J Surg. 1985;72:659-661.

Hatfield MK. Percutaneous imaging-guided solid organ core needle biopsy: coaxial versus noncoaxial method. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(2):413-417.

Hussain SM, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia: findings at state-of-the-art MR imaging, US, CT and pathologic analysis. Radiographics. 2004;24:3-17.

Kim J, et al. An algorithm for the accurate identification of benign liver lesions. Am J Surg. 2004;187:274-279.

Kosugi C, et al. Needle-tract implantation of hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma after ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture: clinical and pathologic characteristics and the treatment of needle-tract implantation. World J Surg. 2004;28:29-32.

Kucharczyk W, et al. Cardiac tamponade as a complication of thin-needle aspiration lung biopsy. Chest. 1982;82:120-121.

Kulesza P, et al. Cytopathologic grading of hepatocellular carcinoma on fine-needle aspiration. Cancer. 2004;102:247-258.

Kuo FY, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of liver tumors. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:142-148.

Libe R, et al. Long-term follow up study of patients with adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:489-494.

Longchampt E, et al. Accuracy of cytology vs. microbiopsy for the diagnosis of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and macroregenerative nodule: definition of standardized criteria from a study of 100 cases. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:515-523.

Maharaj V, et al. Sampling variability and its influence on the diagnostic yield of percutaneous needle biopsy of the liver. Lancet. 1986;8:523-535.

Nasuti JF, et al. Diagnostic value and cost-effectiveness of on-site evaluation of fine-needle aspiration specimens: review of 5688 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:1-4.

National Institutes of Health. NIH state-of-the-science statement on management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (“incidentaloma”). NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1-25.

Ohlsson B, et al. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis and management of liver tumours. Br J Surg. 2002;89:757-762.

Perkins JD. Seeding risk following percutaneous approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(11):1603.

Phillips MS, et al. Negative predictive value of imaging-guided abdominal biopsy results: cytologic classification and implications for patient management. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:693-696.

Piccinino F, et al. Complications following percutaneous liver biopsy: a multicentre retrospective study on 68,276 biopsies. J Hepatol. 1986;2:165-173.

Ponchon T, et al. Methods, indications and results of percutaneous choledochoscopy: a series of 161 procedures. Ann Surg. 1996;223:26-36.

Riemann B, et al. Ultrasound-guided biopsies of abdominal organs with an automatic biopsy system: a retrospective analysis of the quality of biopsies and of hemorrhagic complications. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:102-107.

Ruben RA, Chopra S. Bile peritonitis after liver biopsy: nonsurgical management of a patient with an acute abdomen: a case report with review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:265-268.

Sawyerr AM, et al. A comparison of transjugular and plugged percutaneous liver biopsy in patients with impaired coagulation. J Hepatol. 1993;17:81-85.

Schotman SN, et al. Subcutaneous seeding of hepatocellular carcinoma after percutaneous needle biopsy. Gut. 1999;45:626-627.

Silverman JF, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and role of immediate interpretation of fine needle aspiration biopsy specimens from various sites. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:791-796.

Sofocleous CT, et al. CT-guided transvenous or transcaval needle biopsy of pancreatic and peripancreatic lesions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1099-1104.

Stattaus J, et al. MR-guided core biopsy with MR fluoroscopy using a short, wide-bore 1.5 Tesla scanner: feasibility and initial results. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(5):1181-1187.

Stewart CJ, et al. Brush cytology in the assessment of pancreatico-biliary strictures: a review of 406 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:449-455.

Stewart CJR, et al. Comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and needle core biopsy in the diagnosis of radiologically detected abdominal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:93-97.

Stigliano R, et al. Seeding following percutaneous diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma. What is the risk and the outcome? Seeding risk for percutaneous approach to HCC. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(5):437-447.

Swischuk JL, et al. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of the lung: review of 612 lesions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9:347-352.

Thompson JN, et al. Focal liver lesions: a plan for management. Br Med J. 1985;290:1643-1645.

Weber A, et al. Diagnostic approaches for cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(26):4131-4136.

Westcott JL, et al. Transthoracic needle biopsy of small pulmonary nodules. Radiology. 1997;202:97-103.

Yu SCH, et al. US-guided percutaneous biopsy of small (<1 cm) hepatic lesions. Radiology. 2001;218:195-199.