Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes

Josep Dalmau and Myrna R. Rosenfeld

• The paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes include an extensive group of disorders that can affect any part of the central or peripheral nervous system.

• Evidence indicates that many of these syndromes have an immunopathogenesis.

• Patients with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes may have serum and cerebrospinal fluid antibodies that are highly specific for the presence of a cancer. The detection of these antibodies serves as a marker of paraneoplasia. Other antibodies associate with specific neurologic syndromes that occur with or without cancer. In these cases, the antibodies serve as markers for the neurologic syndrome but do not distinguish between a paraneoplastic or nonparaneoplastic etiology.

• Antibodies directly mediate some disorders such as the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and neuromyotonia and likely mediate other disorders such as anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. In these disorders the antibodies target neuronal cell surface proteins (e.g., receptors and ion channels), and immunotherapy along with tumor treatment often result in substantial neurologic improvement.

• For paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes in which T-cell mechanisms are predominant, the associated antibodies target intracellular neuronal proteins. In this group of disorders, the response to therapy is, in general, disappointing. The physician’s main concern should be to rule out other diagnostic entities and to uncover the presence of the associated neoplasm. For these syndromes the treatment approach should be aimed at the tumor, because stabilization and, less often, improvement of neurologic symptoms after tumor treatment have been reported for almost all syndromes. In a few cases, depending on the syndrome and whether the patient is in the early stages of the neurologic disease, treatment with immunosuppression may have some effect on the paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome.

Introduction

Most paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes are thought to have an immunopathogenesis. One hypothesis is that the expression of neuronal antigens by the tumor triggers the production of antineuronal antibodies that can be found in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Some antibodies are highly specific for the paraneoplastic origin of the neurologic symptoms and are not found (or are rarely found at low titers) in patients with similar neurologic disorders without cancer. These antibodies serve as markers of the paraneoplastic origin of neurologic symptoms and as markers for the presence of specific tumor types (Table 39-1).

Table 39-1

Immune Associations in Paraneoplastic Neurologic Disorders

| Antibody | Syndrome | Most Common Tumor Association |

| Anti-Hu | PEM/PSN | SCLC |

| Anti-Yo | PCD | Ovary, breast |

| Anti-Ma | Brainstem encephalitis/PCD | Several |

| Anti-Ma2 | Limbic/brainstem encephalitis | Testicular |

| Anti-Ri | Opsoclonus-ataxia | Breast, gynecologic |

| Anti-Tr | PCD | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Anti-amphiphysin | Stiff man syndrome | Breast, SCLC |

| Anti-CV2/CRMP5 | PEM/PCD, peripheral neuropathy, uveitis | SCLC, several |

| Anti-recoverin | Retinopathy | SCLC |

| Anti-bipolar cells of retina | Retinopathy | Melanoma |

| Anti-NMDAR* | Limbic encephalitis, seizures, psychiatric symptoms | Teratoma |

| Anti-VGCC* | LEMS, PCD | SCLC |

| Anti-AChR* (muscle) | Myasthenia gravis | Thymoma |

| Anti-AChR* (neuronal) | Autonomic neuropathy | SCLC |

| Anti-Caspr2* | Peripheral nerve hyperexcitability (with/without CNS involvement) | Thymoma, others |

| Anti-LGI1* | Limbic encephalitis | Thymoma, SCLC |

| Anti-AMPAR* | Limbic encephalitis with tendency to relapse | SCLC, thymoma, breast |

| Anti-GABAB* | Limbic encephalitis with prominent seizures | SCLC |

| Anti-mGluR5 | Limbic encephalitis | Hodgkin lymphoma |

*This antibody may occur with or without a cancer association and is therefore not a marker of paraneoplasia.

An immune-mediated pathogenesis has been demonstrated for several syndromes. Patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) have serum antibodies against voltage-gated calcium channels that are expressed by the tumor, which usually is a small cell lung cancer (SCLC). These antibodies block the entry of calcium necessary for the release of quanta of acetylcholine and result in neuromuscular weakness.1 In paraneoplastic myasthenia gravis, a thymoma triggers an immune response against the acetylcholine receptor at the postsynaptic level of the neuromuscular junction, resulting in weakness and fatigability.2 Evidence supporting an immune pathogenesis in other syndromes includes responses to immunomodulatory therapies and in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating antineuronal effects of the antibodies.3–7 In all cases where antibodies are or appear to be pathogenic, the target antigens are neuronal cell surface receptors or ion channels or proteins that interact with synaptic proteins. Patients with these antibodies often respond to antibody-depleting immunotherapies in addition to treatment of the underlying tumor.

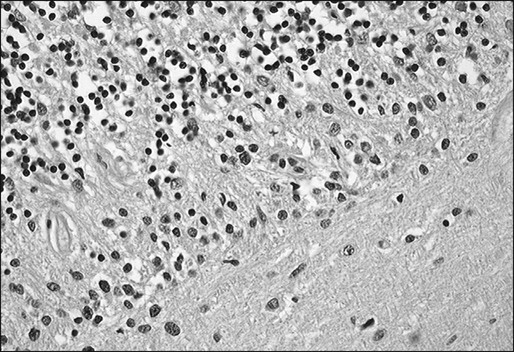

In contrast, there exists a group of antibodies that are directed against intracellular neuronal antigens. In disorders associated with these antibodies, the pathogenicity appears to be mediated by cytotoxic T cells. Autopsies of patients with these antibodies often demonstrate intense inflammatory infiltrates of mononuclear cells, including CD4+ and CD8+, which predominate in the areas that are symptomatic.8,9 Because of the neuronal destruction caused by the cytotoxic T cells, these disorders tend to be refractory or minimally responsive to treatment.

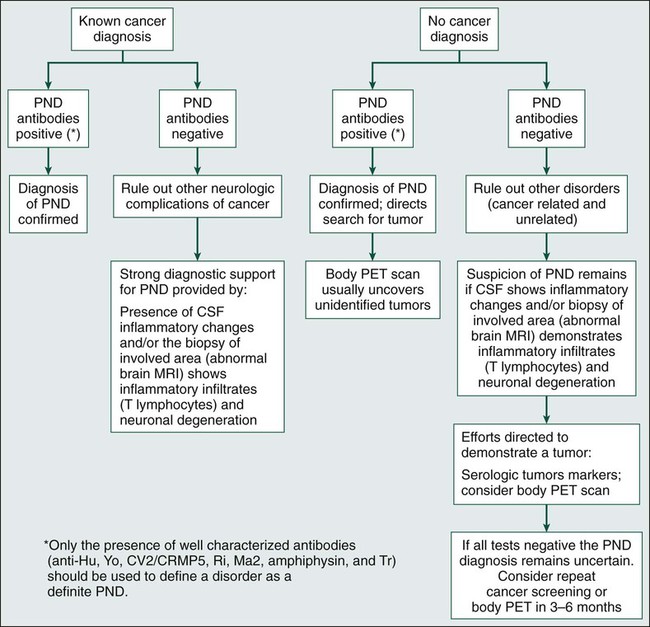

Identification of the paraneoplastic origin of a patient’s symptoms is important because in more than two thirds of patients, the neurologic symptoms develop before the cancer is detected. Because similar disorders may occur without cancer, the diagnosis of the paraneoplastic origin of a disorder depends heavily on the index of suspicion, which is based in part on the syndrome, because some syndromes have a paraneoplastic origin more frequently than do others. For example, the likelihood that LEMS or subacute cerebellar degeneration in a middle-aged or elderly patient is paraneoplastic is probably greater than 50%.10 In contrast, subacute sensory neuropathy or dermatomyositis probably is paraneoplastic in origin in less than 20% of patients.11,12 In most paraneoplastic syndromes, symptoms develop acutely or subacutely and may resemble a viral process. Symptoms evolve over weeks or months and then stabilize, differentiating them from the more chronic and progressive degenerative diseases of middle age and adulthood. Criteria have been proposed to facilitate the diagnosis of paraneoplastic disorders that take into consideration the type of neurologic syndrome, the detection of an associated tumor, and the presence or absence of paraneoplastic antibodies (Box 39-1 and Fig. 39-1).13

Paraneoplastic Syndromes of the Central Nervous System

Paraneoplastic Encephalomyelitis

Patients with PEM experience symptoms of multifocal involvement of the nervous system, resulting in several syndromes that may occur in isolation or in various combinations.14,15 Syndromes include limbic encephalitis, cerebellar degeneration, brainstem encephalitis, myelitis, and sensory and autonomic neuropathies.

Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis has been described in association with many tumors, but in 70% of patients, the underlying tumor is a SCLC. Most tumors are diagnosed within 2 years of neurologic presentation. Most patients with PEM and SCLC have high titers of anti-Hu antibodies in their serum and CSF, as do some patients with PEM that is associated with other types of cancer.14,16 Antibodies to CV2/CRMP5, with or without anti-Hu antibodies, also occur at a lower frequency and most commonly are associated with thymoma.14,17 A subset of patients with PEM and antibodies to CV2/CRMP5 also experience paraneoplastic chorea and uveitis.18

The onset of symptoms in persons with PEM is subacute. Sensory neuropathy is the most common initial manifestation, followed by brainstem and limbic encephalopathy.14,19,20 Symptom progression is usually relentless, or, less frequently, intermittent, until stabilization. Spontaneous improvement is rare but has been described in patients with limbic encephalitis.21 For most patients the neurologic deficits are severe and incapacitating. Respiratory or autonomic failure due to neurologic dysfunction is commonly the cause of death.14,19

About one third of patients with PEM experience symptoms of cerebellar and/or brainstem dysfunction.14,19 Motor weakness, muscle atrophy, and fasciculations are found in 20% of patients with PEM.19 When spinal cord involvement predominates, a diagnosis of subacute motor neuron dysfunction or atypical motor neuron disease may be entertained until other areas of the nervous system become involved.22,23 Autonomic dysfunction affects about 30% of patients. Symptoms include orthostatic hypotension, gastrointestinal paresis, and pseudoobstruction.24,25 Hypothermia, hypoventilation, sleep apnea, and cardiac arrhythmias may be the cause of sudden death in these patients.

About 75% of patients with anti-Hu–associated PEM experience an asymmetric pansensory neuropathy, called “paraneoplastic sensory neuronopathy” (PSN; see later discussion).14,19 PSN is often associated with painful dysesthesias that result from inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia and neuronal degeneration. For patients in whom motor weakness and a sensory neuropathy develop subacutely, the initial diagnosis may be that of acute inflammatory polyneuritis (Guillain-Barré syndrome [GBS]).26

Limbic Encephalitis

Symptoms of paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) may develop alone but more often are found in association with brainstem dysfunction, cerebellar symptoms, or PSN (see “Paraneoplastic Encephalomyelitis”).19 The most common underlying tumor is SCLC, followed by testicular cancer. Regardless of the tumor type, the neurologic dysfunction usually precedes the diagnosis of cancer.

The most characteristic finding is short-term memory deficits with relative preservation of other cognitive functions.27,28 Memory deficits often become evident after several weeks of depression, personality changes, irritability, and seizures. Partial complex temporal lobe seizures with or without motor involvement of the face and extremities are common. Some patients show signs of diencephalic-hypothalamic dysfunction, including drowsiness, hyperthermia, hyperphagia, and, less frequently, pituitary hormonal deficits. The disorder may resemble viral encephalitis or a rapidly developing dementia due to a primary neurodegenerative disorder.

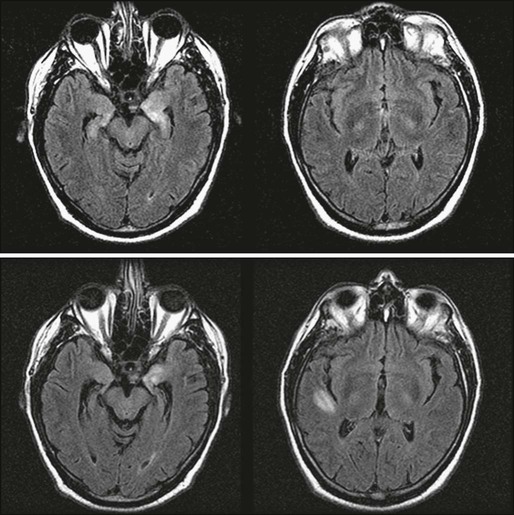

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis is one of the few paraneoplastic neurologic disorders in which neuroimaging may be useful. Typical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings include unilateral or bilateral mesial temporal lobe abnormalities best seen on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images (Fig. 39-2).21,29–31 On T1-weighted sequences, the temporal-limbic regions may be hypointense and sometimes may enhance with contrast injection. Patients with herpes simplex encephalitis may have similar MRI findings in the early stages of the disease. However, these patients usually exhibit prominent signs of edema and mass effect involving one or both inferomedial temporal lobes, inferior frontal lobes, and the cingulate gyrus, which often is associated with gyral enhancement and signs of hemorrhage.32,33

The major pathological findings are seen in the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, cingular cortex, insular cortex, and diencephalon.28 Almost all patients have mild abnormalities in other areas of the nervous system in a pattern of distribution resembling PEM, suggesting that PLE should be regarded as PEM with predominant involvement of the limbic structures.

Antineuronal antibodies, when present in serum and CSF, facilitate the diagnosis of PLE and often allow for early detection of the associated tumor. In patients with SCLC, the anti-Hu antibody is present in about 50% of cases with predominant or isolated symptoms of limbic encephalitis.34 A few patients have been reported with limbic encephalitis and anti-CV2/CRMP5 antibodies. In these patients the underlying tumors are SCLC and thymoma.35 Anti-Ma2 antibodies may be found in the serum and CSF of patients with limbic and/or brainstem encephalopathy. These patients usually have testicular cancer (either seminomatous or nonseminomatous germ cell tumors), but other tumors have been reported.9 Patients with anti-Ma2 antibodies often have additional involvement of the hypothalamus and brainstem and are more likely to have abnormal MRI findings than are other patients with PLE.36

Limbic encephalitis may be associated with antibodies to leucine-rich glioma-inactivated–1 protein (LGI1), an epilepsy-related protein.37 In addition to seizures, some patients experience hyponatremia and rapid eye movement sleep disturbances. The disorder is paraneoplastic in about 20% of cases, with thymoma and SCLC the more commonly associated tumors. Until recently this disorder was incorrectly attributed to antibodies to voltage-gated calcium channels.

Acute limbic dysfunction, sometimes with psychiatric features in association with antibodies to the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, has been reported and appears to more commonly affect middle-aged women.5,38 Approximately 70% of the cases are paraneoplastic, with lung, breast, or thymic tumors being the most common.

Limbic encephalitis associated with antibodies to the gamma-amino-butyric acid type B (GABAB) receptor has been reported.39 Patients with this condition usually have seizures, and in about 50% of cases, patients have SCLC or a neuroendocrine tumor of the lung. Additional antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and antibodies to nonneuronal proteins of unclear significance are frequently present, suggesting a tendency to autoimmunity.40

Two cases of limbic encephalopathy in association with Hodgkin lymphoma (Ophelia syndrome) were reported in which the target antigen was shown to be the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5).41 One patient responded to corticosteroids and the other to treatment of the tumor. The initial patient reported with Ophelia syndrome also responded to tumor treatment.42

When limbic encephalitis is part of PEM or PSN, it usually responds poorly to treatment. Symptom stabilization or improvement may occur if the tumor is recognized and treated early.9,15,43 A study of patients with SCLC and PLE suggested that the presence of anti-Hu antibodies was associated with a decreased likelihood of improvement.34 In contrast, about 35% of patients with limbic encephalopathy associated with antibodies to Ma2 improve with immunotherapy and treatment of the tumor (of these 35% of patients, most have a testicular germ-cell tumor).44

The syndromes associated with LGI1, AMPA receptor, and GABAB receptor antibodies often respond to treatment of the tumor, when present, and immunotherapy. Patients with AMPA receptor antibodies have a tendency to relapse that can be successfully treated with reinstitution of immunotherapy.5

Anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor Encephalitis

Anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis is the most common of the recently described immune-mediated encephalitides that associate with and are likely caused by antibodies to neuronal cell surface receptors or ion channels (see “Limbic Encephalitis”).45,46 Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis usually occurs in young women and children of both sexes, although older men and boys may be affected.47 Patients present with an acute change in behavior and personality and memory loss, and they may be diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder or be suspected of malingering or drug abuse. Symptoms progress within days or weeks to include seizures, a decreased level of consciousness, abnormal movements (e.g., orofacial and limb dyskinesias and dystonia), and autonomic instability with frequent hypoventilation.47 The antibodies are directed against the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor that is highly enriched in the hippocampus (Fig. 39-3). Studies in vitro and in vivo have shown that the binding of the antibodies to the receptors alter the number and function of the receptors in a reversible manner.6 Titers of antibodies are higher in CSF than in serum, and CSF titers may remain elevated even when serum is negative.

About half of women older than 12 years will have unilateral or bilateral ovarian teratomas (either benign or malignant) that may be mistaken for benign ovarian cysts upon imaging, whereas only 8% of girls younger than 12 years have an associated tumor.48 Tumors occur in only 5% of male patients (usually a testicular germ cell tumor).47

The course of the disorder may be prolonged even with aggressive treatment. Early institution of therapy improves outcome, although patients with prolonged courses will often have substantial if not complete recovery with continued care.47,49 Treatment should focus on identification and removal of a tumor if present and immunotherapy with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs), or plasma exchange. Patients who do not respond to initial treatments should receive second-line therapy with cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab, because this treatment significantly improves outcomes.48 Relapses occur more frequently in nonparaneoplastic cases and in paraneoplastic cases in which the tumor was not removed.50

Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration

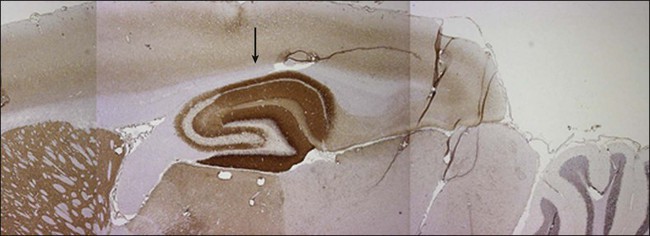

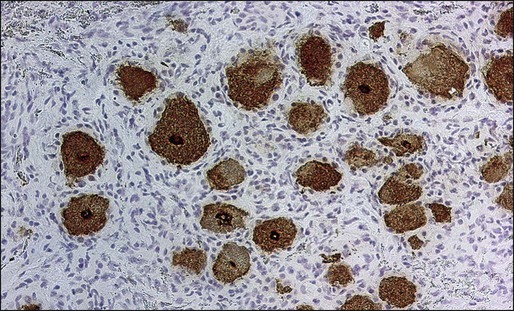

PCD is characterized by the subacute development of rapidly progressive cerebellar dysfunction, which stabilizes after a few months, leaving the patient severely disabled.51 Postmortem studies demonstrate near or total loss of Purkinje cells with relative preservation of other cerebellar neurons, and they also demonstrate Bergmann astrogliosis (Fig. 39-4). Almost every type of tumor has been reported in association with PCD; the most common neoplasms are gynecologic tumors, breast and lung cancers, and lymphomas.52,53 Neurologic symptoms precede detection of the tumor in about 60% of patients.

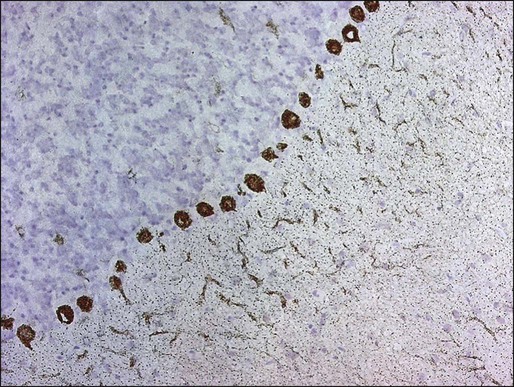

Manifesting symptoms of PCD include dizziness, visual problems, nausea, vomiting, and dysarthria. Within days or even hours, ataxia of gait and of the extremities develops, usually accompanied by dysphagia. Some patients with PCD who have gynecologic or breast tumors have serum and CSF antibodies called anti-Yo that react with 34- and 62-kd proteins expressed by Purkinje cells and the underlying tumor.51 Other patients may have PCD in association with Hodgkin disease, in which case an antibody called anti-Tr usually is found (Fig. 39-5).54,55

For patients with SCLC, PCD may develop in association with LEMS.52,56 Because LEMS symptoms often are treatable, suspicion of LEMS should prompt an appropriate investigation with electrophysiological testing or measurement of antibodies directed against P/Q type voltage-gated calcium channels. These antibodies may also be present in some patients with SCLC and PCD without symptoms of LEMS.57

A distinctive clinical syndrome occurring predominantly in women is characterized by the subacute onset of ataxia and opsoclonus.58 The ataxia predominates in the trunk, causing severe gait difficulty and frequent falls. In half of these patients, the neurologic symptoms develop before the tumor is diagnosed. The tumor usually is a breast cancer or, less frequently, gynecologic cancers or SCLC. The serum and CSF of these patients contain an antibody called anti-Ri, which is expressed by neurons and the associated tumor.58,59

In patients with SCLC, the development of PCD may be the manifesting symptom of PEM. In such cases, anti-Hu or anti-CV2/CRMP5 antibodies usually are present, and patients eventually develop signs and symptoms of multifocal neurologic disease. Patients whose symptoms remain restricted to the cerebellum and who do not harbor anti-Hu antibodies may have antibodies to voltage-gated calcium channels.60

In one subset of patients, PCD develops in the setting of brainstem dysfunction. These patients have serum and spinal fluid antibodies against Ma1 and Ma2 proteins expressed in neurons and spermatogenic cells of the testis. These patients have a variety of associated cancers, including those of the lung, breast, parotid, colon, and testis.61

Most patients with PCD do not improve, although there are isolated reports of improvement with treatment of the tumor, corticosteroids, IVIG, plasma exchange, rituximab, or cyclophosphamide.64–64

Motor Neuron Syndromes

The existence of paraneoplastic motor neuron dysfunction is based on reports of patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) who improved after treatment of the underlying tumor, suggesting more than a coincidental relationship.65,66 In patients with cancer and symptoms of motor neuron disease, the most common neoplasms are carcinoma of the lung, breast, kidney, and lymphoma.67,68 For these patients, the neurologic syndrome and laboratory studies are similar to those seen in patients with typical ALS.

Patients with PEM may experience symptoms resembling motor neuron disease.19,22 These patients almost always exhibit signs of involvement of other areas of the nervous system, which, along with the presence of the anti-Hu antibody, helps to rule out ALS.

Patients with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience a subacute lower motor neuronopathy.69 Typically, these patients have subacute, progressive, painless, and asymmetric involvement of the extremities, with legs affected more than the arms. In contrast to typical ALS, fasciculations are rare, bulbar muscles are usually spared, and upper motor neuron signs are absent. Examination of the CSF is normal or shows mildly increased proteins, and electrophysiological studies demonstrate denervation with normal or mild slowing of motor nerve conduction velocities. Neurologic stabilization or spontaneous improvement may occur. Paraneoplastic subacute lower motor neuronopathy must be distinguished from the lower motor neuron dysfunction that may develop after radiation therapy of the spinal cord.70

Stiff Man Syndrome

Stiff man syndrome is an unusual disorder characterized by progressive muscle stiffness, aching, muscle spasms, and rigidity. The stiffness develops over a period of months and is most prominent in the paraspinal muscles and lower limbs. The muscle spasms are painful and triggered by a variety of stimuli. They are severe enough to produce limb deformities and fractures.71 There are no other associated neurologic abnormalities; the CSF may show oligoclonal bands and increased IgG index, and neuroradiologic studies are usually normal.72 The tumors most commonly involved include breast cancer, SCLC, thymoma, and Hodgkin disease. A subset of patients with paraneoplastic stiff man syndrome and breast cancer or SCLC have antibodies that react with amphiphysin, a neuronal synaptic protein.71,73,74 When stiff man syndrome occurs in patients who do not have cancer, the disorder is associated with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase.77–77 Diabetes and other endocrine deficits usually develop in these patients. Treatment of the tumor and use of corticosteroids may result in improvement. Patients with nonparaneoplastic stiff man syndrome respond to IVIG, and this approach may be useful for patients with the cancer-associated syndrome.78,79 Drugs that enhance GABA-ergic transmission (e.g., diazepam, baclofen, sodium valproate, tiagabine, and vigabatrin) improve symptoms of most patients.80

Peripheral Nerve Hyperexcitability (Neuromyotonia)

Peripheral nerve hyperexcitability is characterized by muscle cramps, stiffness, myokymia, and delayed muscle relaxation due to spontaneous and continuous muscle fiber activity of peripheral nerves.81 It often is found in association with a sensorimotor polyneuropathy and has been described most often in patients with thymoma and SCLC.82 Electrophysiological studies reveal large numbers of bizarre, high-frequency motor unit discharges during voluntary contraction that persist during relaxation, in contrast to patients with stiff man syndrome, who have continuous but relatively normal motor unit activity. Morvan syndrome is used to describe the occurrence of neuromyotonia in association with CNS dysfunction (i.e., cognitive impairment, memory loss, hallucinations, seizures, and autonomic dysfunction).83,84

In addition to tumor treatment, small case series have reported responses to a variety of immunomodulatory treatments including plasmapheresis, IVIG, and prednisolone with or without azathioprine or methotrexate.85,86 Symptom improvement may be obtained with carbamazepine or phenytoin.87

Some patients with neuromyotonia or Morvan syndrome had incorrectly been described as having antibodies that target the voltage-gated potassium channel. In fact, the antigenic targets are proteins that interact with the channel. These proteins include contactin-associated protein-like 2 (Caspr2), an axonal protein that helps cluster the potassium channel in the juxtaparanodal region and is also expressed in the hippocampus.88 Caspr2 antibodies have been found in patients with thymoma and also in patients without cancer. Patients with Caspr2 antibodies often respond to immunotherapy, suggesting a pathogenic role of the antibodies.

Paraneoplastic Opsoclonus-Myoclonus

Opsoclonus is a disorder of ocular motility characterized by the presence of spontaneous, arrhythmic, large-amplitude conjugate saccades occurring in all directions of gaze without a saccadic interval.89 In patients with cancer, opsoclonus can have a paraneoplastic origin, in which case it often is associated with myoclonus of the head, trunk, or extremities (paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus). The differential diagnosis includes viral, toxic, metabolic, and vascular disorders.

In children, paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus is a well-known complication of neuroblastoma.90,91 In half of the patients, the opsoclonus precedes diagnosis of the neuroblastoma, but it may also develop after tumor diagnosis, during remission, or at recurrence. The onset is subacute, with frequent fluctuations of symptoms; in some patients, symptoms may resolve spontaneously. Treatment with corticosteroids, adrenocorticotropic hormone, plasma exchange, or IVIG or treatment of the tumor results in improvement in half to two thirds of patients.92 Some children refractory to these therapies have been reported as responding to rituximab or other anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.93,94 Despite an initial response, about 60% of patients are left with permanent neurologic deficits, including language and cognitive dysfunction.95

Paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus has also been described in adult patients with cancer. Most have an underlying SCLC, although individual case reports are associated with other tumors, including carcinoma of the uterus, fallopian tube, breast, bladder, thyroid, and thymus, chondrosarcoma, and Hodgkin disease.89,96–99 Reports have been made of a small number of women with breast cancer, anti-Ri antibodies, and opsoclonus.58,100 Patients with anti-Ri antibodies often have other symptoms, suggesting diffuse involvement of the brainstem, whereas patients without anti-Ri antibodies tend to have limb or truncal myoclonus and encephalopathy.

Compared with the idiopathic form of opsoclonus-myoclonus, from which patients often recover, paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus in adults has a more severe clinical course, even when aggressively treated with IVIG or corticosteroids. For patients who experience an associated encephalopathy, one series noted improved outcomes when the tumor (usually SCLC) was identified and treated promptly.101 No specific antibody markers have been found that identify adult or pediatric paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus, although recent studies found a high incidence of autoimmune responses to a variety of neuronal autoantigens.102,103

Paraneoplastic Syndromes of the Visual System

In patients with cancer, visual symptoms and blindness are usually related to metastatic infiltration of the optic nerves by tumor and neurotoxicity from chemotherapy and radiation therapy.104–107 Paraneoplastic visual syndromes can result from optic neuropathy and retinopathy. Paraneoplastic optic neuropathy is very rare, and although it may develop in isolation, it usually is associated with PEM.108 Onset is subacute with painless bilateral visual loss.109,110 Additional features include vertical gaze paresis, opsoclonus, and bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Some patients have antibodies to CV2/CRMP5.111

The paraneoplastic retinopathies are a heterogeneous group of syndromes including cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) and melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR). These two syndromes have specific clinical, electrophysiological, and pathological characteristics and distinct immunologic associations. In patients with CAR, acute or subacute visual loss develops as a result of degeneration of the retinal photoreceptor or ganglion cells.112,113 The onset is usually unilateral but becomes bilateral over days or weeks. Initial symptoms include photosensitivity, light-induced glare, color vision deficits, intermittent visual obscurations, and central or ringlike scotomas. For most patients the underlying tumor is SCLC, but a few case reports have been associated with breast or gynecologic cancers. Visual symptoms usually precede diagnosis of the tumor. Visual-evoked responses often are normal, but electroretinograms demonstrate reduced or flat responses to photopic and scotopic stimuli, suggesting dysfunction of cones and rods. Examination of the CSF may reveal a mild pleocytosis; neuroimaging studies are normal.

The serum of some patients with CAR contains antibodies that react with antigens expressed by photoreceptors and ganglion cells. The most common antibody is against recoverin, a 23-kd photoreceptor calcium-binding protein,114 and the presence of anti-recoverin antibodies indicates that the associated tumor almost always is a SCLC.115 These antibodies cause apoptotic retinal cell death, suggesting a direct pathogenic role.116 More than 20 other less common antigenic targets have been identified in patients with CAR, including tubby-like protein 1 and the photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor.117,118 The role of these antibodies in the pathogenesis of the retinopathy is unknown, but it is of interest that mutations of the photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor gene have been identified in a cohort of patients with enhanced S-cone syndrome, a disorder of retinal cell fate that progresses to retinal degeneration.119,120 This finding suggests a mechanism whereby antibodies interfere with autoantigen function, resulting in retinal cell death.

Melanoma-associated retinopathy has been described in patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma. These patients present with acute visual loss years or months after the diagnosis of the metastatic disease121,122 and have serum antibodies that target unidentified proteins localized in the bipolar cells of the retina.123,124 The electroretinogram shows selective loss of the photopic “b” wave with relative preservation of the “a” and “d” waveforms. Intraocular injection of serum from patients with MAR reproduces the retinal abnormalities, demonstrating that the antibodies are pathogenic.122

For both CAR and MAR, the visual loss is usually irreversible. Treatment with immunosuppression, plasma exchange, or corticosteroids is mostly ineffective, but in rare cases it may result in symptom stabilization.125,126 Three patients with CAR who had a mild to moderate response to IVIG have been reported, as well as one patient with a response to alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody.127,128 For patients with MAR, it has been suggested that cytoreductive surgery with or without immunotherapy may be associated with improved visual acuity.129

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation is a rare paraneoplastic disorder in which patients with cancer experience diffuse proliferation of melanocytes in the uveal tract, resulting in progressive visual loss.130 Carcinoma of the reproductive tract in women and lung and pancreatic tumors in men have been most commonly reported. The onset is abrupt, often before the cancer diagnosis, and is associated with the development of cataracts and retinal detachment. Three cases with responses to plasma exchange have been reported.131,132

Paraneoplastic Syndromes of the Peripheral Nervous System

Paraneoplastic Sensory Neuronopathy

PSN resulting from dorsal root ganglia dysfunction may develop in isolation but most often is a fragment of PEM.19 Patients typically experience asymmetric pain and paresthesias that can mimic radiculopathy or multineuropathy.133 Symptoms usually progress over weeks or months to involve other extremities and, sometimes, the trunk.19 Cranial nerves may be affected, resulting in loss of taste, facial numbness, and sensorineural deafness. Eventually, severe involvement of all modalities of sensation occurs, resulting in pseudoathetotic movements of the hands, a debilitating sensory gait ataxia, and neuropathic pain that are difficult to control.

In more than 80% of patients with PSN, the associated tumor is SCLC. Sensory symptoms usually precede diagnosis of the tumor. Electrophysiological studies confirm the isolated or predominant involvement of the sensory nerves, but in some patients, the motor conduction velocities may be affected.134 These patients had evidence of both demyelination and axonal degeneration in association with loss of neurons in the dorsal root ganglia and circulating anti-CV2/CRMP5 antibodies in association with anti-Hu antibodies.

Patients with PSN as a component of PEM often have anti-Hu antibodies, and the associated cancer almost always is a SCLC (Fig. 39-6).14,19 In patients with PSN without anti-Hu antibodies, associated cancers include SCLC, non-SCLC lung tumors, and breast cancer. Except for the detection of anti-Hu antibodies in patients with SCLC, laboratory studies of patients with PSN are nonrevealing. The CSF may show increased proteins and a mononuclear pleocytosis.

There is no specific treatment for PSN. Studies have suggested that patients with PSN associated with SCLC and anti-Hu antibodies whose tumors responded to therapy were more likely to have stabilization or improvement of the PSN compared with patients whose tumors were not treated or did not respond to treatment.14,15 Some patients may have partial improvement with corticosteroids. The effects of IVIG, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab are unclear.64,135,136

Sensorimotor Neuropathies

Many patients with cancer, particularly those with advanced disease and significant weight loss, have signs and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy. In most patients, an identifiable cause such as a nutritional deficit, hepatic or renal failure, the use of chemotherapeutic agents, or leptomeningeal metastases can be found. Mononeuropathies and plexopathies in patients with cancer most often are a result of compression of nerves by tumor or hemorrhage and infarction as a result of leukemic infiltration. A paraneoplastic brachial neuritis may occur with increased frequency in patients with Hodgkin disease.137,138 The clinical presentation is similar to that of brachial neuritis observed in patients without cancer, with the initial pain complaints followed by the development of paresthesias and weakness.

A subacute or chronic sensorimotor neuropathy may occur with any malignancy but most commonly is associated with lung cancers.139,140 The onset usually follows the cancer diagnosis but may precede it by several months or years. Lower extremities are predominantly involved, with symptoms spreading proximally over the course of the disease with rare involvement of cranial nerves. Weakness occurs late, and most patients have slowly progressive disease.

An acute rapidly progressive sensorimotor polyneuropathy can be seen in association with Hodgkin lymphoma.141 The syndrome is clinically indistinguishable from GBS. A similar syndrome also has been reported in patients with solid tumors. Treatment is the same as for patients with idiopathic GBS and includes plasma exchange and IVIG. Evidence shows that cancer-associated GBS has a worse outcome than GBS without a cancer association.142

A clinically significant peripheral neuropathy has been reported in 2% to 10% of patients with multiple myeloma.143 The neuropathy, most often sensorimotor, commonly precedes diagnosis of the myeloma and is slowly progressive.144 Treatment of the myeloma usually does not alter the course of the neuropathy. Other cancer-related causes of peripheral nerve or nerve root involvement include deposits of amyloid and root compression by spine metastases.

Osteosclerotic myeloma represents about 3% of all cases of myeloma. More than 50% of patients with osteosclerotic myeloma experience a predominantly motor paraneoplastic peripheral neuropathy, which often is the initial presentation of the myeloma.145 The clinical picture is similar to that of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.146 Resection or radiation of the sclerotic lesions or chemotherapy often results in neurologic improvement.147,148

A peripheral neuropathy with predominant sensory involvement develops in 10% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. In some patients, the monoclonal IgM has activity against myelin-associated glycoprotein or gangliosides.149

The POEMS syndrome (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal proteinemia, and skin changes) is a rare disorder that can develop in association with all forms of myeloma but is more often seen with osteosclerotic myeloma.150 Patients experience a severe, symmetric, sensorimotor neuropathy that is associated with muscle atrophy.

Castleman disease is a rare disorder that overlaps with POEMS syndrome. Patients commonly experience neuropathies, including a painful sensorimotor neuropathy, a chronic relapsing sensorimotor neuropathy, and a predominantly motor neuropathy.151 Treatment of Castleman disease along with plasma exchange or immunosuppression may result in improvement of the neuropathy.152

Vasculitic Neuropathy

Paraneoplastic vasculitis may be systemic or may be confined to nerve and muscle. When systemic, the small vessels of the skin commonly are affected, and the most commonly associated tumors are lymphomas and leukemias.153,154 A paraneoplastic microvasculitis of the muscle and nerve without systemic vasculitis has been reported in older patients with solid tumors, particularly carcinoma of the prostate, kidney, lung, endometrium, and lymphoma.155 Patients experience symptoms of symmetric or asymmetric painful sensorimotor neuropathy. As a result of the muscle vasculitis, proximal muscle weakness can develop. The diagnosis is suggested by the presence of elevated proteins in CSF and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and is confirmed by a biopsy of nerve and muscle. This disorder may respond to corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide or other types of immunosuppression.

Autonomic Neuropathy

Paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy usually occurs as a component of other disorders, such as LEMS and PEM, but it may rarely occur as the predominant symptom.19 Patients with paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy can experience several life-threatening complications, such as gastrointestinal paresis with pseudoobstruction, cardiac dysrhythmias, and postural hypotension. Additional symptoms include dry mouth, erectile dysfunction, anhidrosis, and sphincter dysfunction. Paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy has been reported in association with several tumors, including SCLC, cancer of the pancreas, cancer of the testis, carcinoid tumors, and lymphoma. When the autonomic dysfunction is a component of PEM, serum anti-Hu and anti-CV2/CRMP5 antibodies may be positive. Serum antibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors have been reported, but they also may occur without a cancer association.156

Paraneoplastic Syndromes of the Neuromuscular Junction

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis results from an immune response directed against the acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction. Thymic abnormalities are reported to occur in approximately 75% of patients with myasthenia. Of these patients, 15% have microscopic or gross evidence of thymoma and 85% have evidence of thymic hyperplasia. Patients experience weakness of the extremities and the ocular and bulbar muscles; a few patients have pure ocular involvement.2,157 The most common manifesting signs are ptosis and intermittent diplopia. Proximal muscles tend to be more affected than distal muscles, and muscle atrophy is rare. Deep tendon reflexes are preserved. Pain usually is not reported, although some patients report paresthesias. Aspiration as a result of dysphagia and ventilatory paralysis as a result of respiratory muscle involvement may be causes of death.158

The initial approach to treatment should be directed at the underlying tumor. Additional therapeutic strategies, including symptomatic treatment (e.g., anticholinesterase drugs), immunomodulation (e.g., plasma exchange and IVIG), and immunosuppression (e.g., corticosteroids and azathioprine) are similar for patients with and without cancer.87

Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

LEMS is a disorder of the neuromuscular junction in which the presence of autoantibodies against P/Q type voltage-gated calcium channels results in a defect in the presynaptic quantal release of acetylcholine.161–161 Approximately 60% of patients with LEMS have an associated SCLC.10 Patients with LEMS and SCLC often have antibodies to SOX1; these antibodies are found in fewer than 5% of non-cancer-associated cases of LEMS and are therefore a useful marker for the presence of a SCLC in a patient with LEMS.162

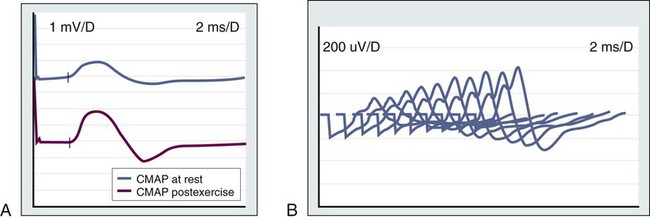

In about 70% of patients with LEMS, neurologic symptoms develop before the tumor diagnosis is made, whereas in most of the remaining cases, symptom onset and tumor diagnosis occur together.163 Patients present with lower extremity weakness, increased fatigability, and difficulties walking, rising from a chair, or climbing stairs. Some patients report a brief increase in muscle strength after a period of activity. Nerve conduction studies show a very-low-amplitude compound muscle action potential that increases progressively (>200%) in response to fast rates (20 to 50 Hz) of repetitive stimulation or after a short period of maximum voluntary contraction (Fig. 39-7). Detection of antibodies against the P/Q type voltage-gated calcium channel is used as a serologic test for LEMS.160

At least 50% of patients have evidence of autonomic dysfunction, such as dry mouth, impotence, constipation, or impaired sweating.10,164,165 Mild and usually transient cranial nerve dysfunction occurs in most patients.166 Although rare, respiratory muscle weakness may occur, even to the point of requiring assisted ventilation. In contrast to persons with myasthenia gravis, in whom the deep tendon reflexes usually are spared, in LEMS they are reduced or absent, especially in the lower extremities. In some patients, LEMS may develop in association with PCD or PEM.52,57

When LEMS is associated with cancer, most patients will have neurologic improvement with combined cancer treatment and therapy directed at LEMS. The latter includes medications that increase the presynaptic release of acetylcholine and immunomodulation. The use of 3,4-diaminopyridine results in moderate to marked neurologic improvement in 80% of patients.167 If 3,4-diaminopyridine is not available, a combination of pyridostigmine and guanidine may be beneficial.168 Plasma exchange and IVIG are useful for treating patients with severe weakness.169 Neurologic improvement occurs within days or weeks but is transient. For patients who are refractory to these treatments, long-term immunosuppression with prednisone or azathioprine may be effective. Patients whose neurologic symptoms relapse should be evaluated for tumor recurrence.

Paraneoplastic Myopathic Syndromes

Polymyositis–Dermatomyositis

Cancer develops in about 9% of patients with polymyositis. Because the neoplasm often is diagnosed several years before or after diagnosis of the polymyositis, this observation may represent a coincidental occurrence.11 In contrast, cancer develops in about 20% to 25% of patients with dermatomyositis, and in most patients the tumor is diagnosed by the time the myopathic symptoms develop.11 Cancer of the breast, lung, ovary, stomach, and lymphoma are most commonly associated with dermatomyositis. It is recommended that patients with a new diagnosis of dermatomyositis undergo cancer screening annually for the first 3 years after diagnosis and then as required for new signs or symptoms suggesting a possible cancer.170

Clinical symptoms of both disorders are similar for patients with and without cancer.171 Patients with dermatomyositis may present with a reddish or purplish skin rash that often precedes the onset of proximal muscle weakness. Serum creatine kinase levels usually, but not always, are elevated. Respiratory muscle weakness may lead to ventilatory failure and contribute to death. Other symptoms include arthralgias and muscle contractures, myocardial inflammation leading to congestive heart failure, and interstitial lung disease.172 Reflexes and sensory examination usually are normal.

About 20% to 40% of patients with dermatomyositis have antisynthetase, anti-signal recognition particle, and anti-translation factor antibodies. Antibodies against histidyl-tRNA synthetase (anti-Jo-1) are found in about 80% of adults with dermatomyositis and concomitant interstitial lung disease.173,174 However, no specific markers are indicative of the paraneoplastic origin of dermatomyositis.

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis often respond to corticosteroids and other types of immunosuppression (e.g., azathioprine). High-dose IVIG has proved to be effective for dermatomyositis.175

Acute Necrotizing Myopathy

Acute necrotizing myopathy has been described in patients with cancer of the lung, bladder, breast, and gastrointestinal tract.176 Patients present with symmetric weakness of the extremities associated with pain and a marked increase of serum muscle enzymes. Electrophysiological studies are consistent with myopathy, and pathology studies demonstrate extensive muscle necrosis with little or no inflammatory infiltrates. Symptoms can rapidly progress to involve pharyngeal and respiratory muscles, often resulting in death. However, case reports of responses to IVIG and corticosteroids have been made.177,178

Treatment and Prognosis

The approach to treatment of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes and the expected response is largely based in the underlying immune mechanism. For the syndromes in which the antigenic targets are intracellular (e.g., Hu and Yo), T-cell mechanisms appear to produce irreversible neuronal destruction that occurs early and rapidly. In general, these syndromes have a subacute, progressive course and result in severe deficits or death in weeks or months.19,51 Spontaneous improvement has been observed in some patients with opsoclonus-myoclonus, mostly children with neuroblastoma,179 or patients with PCD associated with Hodgkin disease,54,180 subacute motor neuronopathy,69 and sensorimotor neuropathies, which usually fulfill the criteria of acute or chronic GBS.141,181,182 Progression to severe disability is seen less often in the neuromuscular disorders that develop after the diagnosis of the tumor, such as some sensorimotor neuropathies. A few patients with anti-Hu–associated sensory neuronopathy, and patients with PCD, particularly those without anti-Yo antibodies, may have a mild, indolent clinical course or even stabilize with only moderate neurologic deficits.52,183

Improvement of neurologic symptoms after tumor treatment has been reported for almost all the paraneoplastic syndromes.184 However, with the exception of osteosclerotic myeloma, in which treatment of the myeloma can clearly result in dramatic improvement of an associated sensorimotor neuropathy, the actual impact of antineoplastic therapy on the paraneoplastic symptoms is difficult to assess.147,185 This difficulty is due, in part, to the low incidence of neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes and the lack of effective treatment for some neoplasms. The rapid and apparently irreversible neuronal damage that is characteristic of many paraneoplastic symptoms may allow potentially effective treatments to arrest but not reverse the neurologic symptoms. Despite these limitations in assessment, some patients with limbic encephalitis have neurologic improvement, which appears to relate to tumor treatment. This outcome is most commonly reported in young men with anti-Ma2 antibodies and germ cell tumors.21,186 Improvement of cerebellar symptoms associated with successful treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma and of anti-amphiphysin-associated stiff man syndrome has also been reported.72,187

For the paraneoplastic syndromes associated with pathogenic antibodies (e.g., myasthenia gravis, LEMS, and neuromyotonia) and the encephalitides associated with antibodies to neuronal cell surface proteins (e.g., NMDA-, AMPA-, GABAB-, LGI1-, and Caspr2-related disorders), treatment of the tumor along with removal of the antibodies or immunosuppression can be highly effective.38,39,47,88