Oncology and Health Care Policy

Steven Kent Stranne, Allen S. Lichter and Deborah Y. Kamin

• Policies promulgated by government at the federal, state, and local levels have profound effects on virtually every aspect of the day-to-day practice of oncology. In the face of extreme financial pressures, policy makers will continue to make decisions that have tremendous impact on the cancer community.

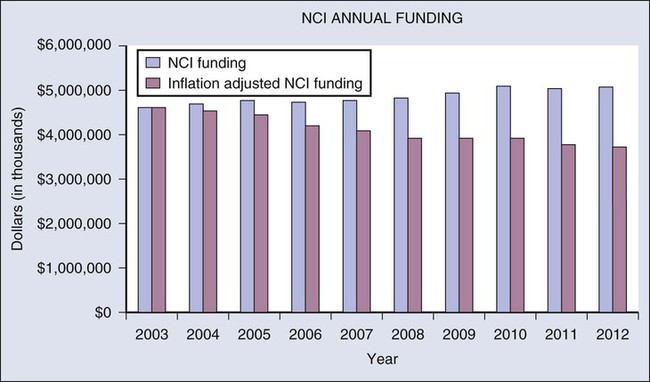

• Federal policies play a critical role in cancer research. Although the national resources devoted to cancer research remain substantial (exceeding $5 billion in 2012), the nation is losing opportunities and efficiencies because of suboptimal funding. The combination of relatively flat funding for the National Cancer Institute since 2003 and biomedical inflation has eroded the effective level of federal support for cancer research by more than 20% during the past decade. The promise for new highly effective cancer therapies has never been brighter, and as a result, the need to amplify the cancer community’s commitment to ensure that adequate research funding exists has never been greater.

• There are many examples within the federal government of initiatives to create safeguards for patients with cancer through laws, regulations, and agency determinations. For example, genetic testing holds great promise to help prevent significant morbidity and mortality for individuals carrying genetic risk factors for certain types of cancer. Although care must be taken to avoid unnecessary regulation, too few protections are currently provided in this area. Oncologists are uniquely positioned to help agency officials establish more robust safeguards that promote and protect the interests of patients with cancer.

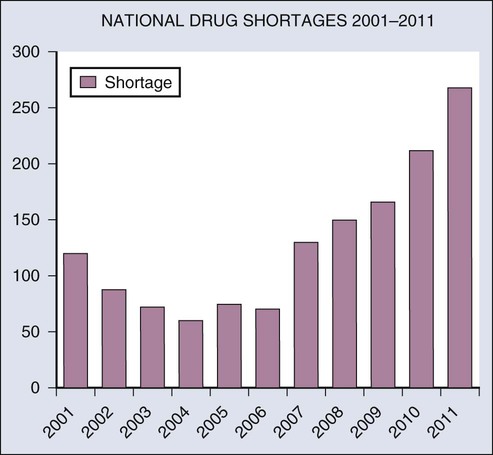

• Drug shortages have also emerged to challenge the oncology community and policy makers. During the past few years, there has been a worsening trend in which critical and often curative anticancer drugs are suddenly becoming unavailable to patients in the United States. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration increased its efforts to tackle this issue, and Congress took initial steps to help address drug shortages. The oncology community should continue to work with Congress and federal agencies to address the complex issue of drug shortages.

• Policies adopted by the Medicare program regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer have greatly influenced both the practice of oncology and the services available to both Medicare and non-Medicare patients throughout the United States. Both public and private insurers often rely on coverage policies, reimbursement levels, and coding used by Medicare as a starting point for establishing their own policies. In the face of extreme economic pressure, oncologists and other cancer care professionals must remain engaged in helping to inform policy makers and to shape these changes. This effort includes working to ensure that policies designed to reduce health care expenditures do not undermine the quality of care received by persons with cancer and that reimbursement for cancer care is fair and adequate to permit the ongoing delivery of high-quality, high-value cancer care.

• Oncologists and other cancer care specialists have unique insights involving the care of patients with cancer, and it will continue to be increasingly important to communicate these insights effectively. Policy can have a profound impact on practice, making engagement in the process not only important but a professional responsibility.

Introduction

Federal and state governments play critical roles in establishing policies that shape and fund virtually every aspect of cancer care and research throughout the United States. Although federal health care reform legislation—the Affordable Care Act (ACA)1—has attracted headlines for several years, such high-profile legislation is just one aspect of cancer policy. Many important policies arise with much less fanfare. Examples include policies adopted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to guide funding of research proposals, national coverage determinations for Medicare promulgated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and policies established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding products used for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.

• Research. Through NCI and other federal agencies, the federal government serves a leadership role in and provides significant funding for cancer research performed throughout the United States, including basic science research, translational research, and clinical trials.

• Patient Safeguards. The federal government promotes patient safeguards and regulates health care services and products. For example, the federal government has taken steps to establish safeguards for genetic testing and privacy of health records. The FDA determines whether cancer drugs and devices may be provided to patients in the United States. The FDA also regulates other areas that affect the day-to-day practice of oncology, including monitoring and reporting of drug-related adverse events. State law and regulation also have a prominent part in regulating cancer care and establishing patient safeguards. Examples include insurance regulation and cancer-specific initiatives such as oral parity legislation.*

• Health Care Insurance. The federal government operates and funds the Medicare program, which covers approximately 60% of all patients with cancer in the United States.2 It also oversees public health programs managed by CMS, the Department of Defense, the Veterans Health Administration, and other federal agencies. Coverage, reimbursement, and coding policies established by Medicare have significant influence on the policies adopted by most other public and private health care insurers. Federal and state laws may also create patient safeguards that private insurers must follow, such as the protections established under the ACA to promote patient access to cancer care through clinical research trials.

Background

The Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of two major provisions of the ACA—the individual mandate (a requirement that individuals maintain a minimum level of health care insurance for themselves and their tax dependents) and the ACA’s requirements for states to expand their Medicaid programs. Architects of the ACA relied heavily on Medicaid as a vehicle for expanding coverage to the uninsured. In June 2012, the Supreme Court upheld the individual mandate but did so by defining it as a tax. The court struck down the ACA’s requirement for states to expand their Medicaid programs.3

Medicaid funding and oversight is a shared responsibility between states and the federal government, and political leaders in many states have indicated an initial unwillingness to engage in any significant expansion of their Medicaid programs. From the perspective of oncology patients and providers, the issue of Medicaid expansion remains complicated. Although any form of coverage may appear preferable to being uninsured, the coverage for cancer care under most Medicaid programs is grossly inadequate, and some studies indicate that cancer outcomes are not significantly better for Medicaid patients in comparison with the uninsured.6–6

Although some provisions of the ACA will remain highly controversial, a number of relatively noncontroversial provisions are particularly important for the cancer community. These provisions include protections for patient access to preventive screening for cancer; protections to help vulnerable individuals with cancer secure and retain access to health insurance; safeguards for individuals with cancer and other preexisting conditions; and protections for patient access to clinical trials.7,8 The political debate over the ACA is certain to continue for many years, and these patient safeguards, which have bipartisan support, warrant the cancer community’s ongoing attention.

As with the ACA, cancer-related policies of significance at the federal level often arise from laws enacted by the U.S. Congress (Table 21-1). However, in virtually every law enacted by Congress, there are substantial gaps, conflicts, and ambiguities within the legislation that must be resolved as part of the implementation process. As a result, the work to influence the final version of a national policy involving cancer rarely ends with the enactment of legislation. Advocates for the cancer community must typically devote substantial attention to educate agency officials and influence policies adopted by agency officials under both new and preexisting legislative authority. These same dynamics also occur at the state level.

Table 21-1

Selected Federal Laws Relevant to Cancer Policy

| Federal Law | Summary of Selected Effects on the Cancer Community |

| National Cancer Institute Act of 1937 | Established the National Cancer Institute and charged it with conducting, fostering, and coordinating research and training related to the cause, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer |

| National Cancer Act of 1971 | Began War on Cancer, initiated the National Cancer Program and its various boards, authorized creation of new cancer centers and training programs, expanded existing research facilities, enhanced collaboration in cancer research between federal, state, and other entities, and appropriated significant funds for a variety of research-related purposes |

| Biomedical Research Training Amendments (1978) | Expanded research on preventing cancer caused by workplace and environmental carcinogens and emphasized cancer education programs initiated within local communities and hospitals |

| Veterans Health Care Act of 1992 | Amended the Public Health Service Act by adding section 340B, which limits the amount certain safety net providers must pay to manufacturers for covered outpatient drugs |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 | Required Medicare to cover off-label uses of anticancer drugs recognized in certain medical compendia and required Medicare to cover orally administered anticancer drugs that have the same indications and active ingredients as covered infused anticancer drugs |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (1996) | Limited the restrictions that group health plans can place on the coverage of preexisting conditions and created security and privacy protections |

| Balanced Budget Act of 1997 | Expanded Medicare coverage for several cancer screening tests, implemented the Sustainable Growth Rate reimbursement methodology, and provided coverage for antiemetic drugs used as part of anticancer chemotherapeutic regimens |

| Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (2003) | Created Medicare Part D (prescription drug benefit), changed methodology for calculating relative value of drug administration services, and instituted new average sales price payment methodology for many drugs and biological products covered under Medicare Part B |

| Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (2008) | Prohibited employment decisions made on the basis of genetic information and prohibited group health plans and health insurers from making coverage and premium decisions for healthy persons on the basis of genetic predispositions for future illnesses |

| Affordable Care Act (2010) | Established safeguards under private health insurance plans to ensure coverage of individuals with preexisting conditions and for individuals participating in clinical trials, established protections for patient access to preventive screenings for cancer under Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, and established the Innovation Center within CMS for evaluating new payment methodologies, including but not limited to accountable care organizations |

| Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (2012) | Established provisions to address shortages of cancer drugs and other medications, included a notification requirement for manufacturers 6 months in advance of an anticipated drug shortage, directed the Food and Drug Administration to include biologicals on drug shortages listings, and included fees for generic drug applications to support agency resources for more rapid reviews of generic drugs, which also may help avoid or alleviate drug shortages |

Research

The federal government plays an integral role in cancer research in the United States, including basic science research, translational research, and clinical trials. Although a number of federal agencies are active in supporting cancer research, the NCI (one of 27 NIH institutes and centers) is the primary agency charged with guiding and funding national research initiatives in oncology. Congress established NCI under the National Cancer Institute Act of 1937.9 Although subject to oversight by Congress and the Administration, NCI retains significant discretion to establish overarching policies and make case-by-case decisions that shape national research efforts.

Federal policy makers have recognized the importance of harnessing the economic benefits of cancer research and supporting the United States’ international leadership position in this field. For example, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), Congress provided nearly $1.3 billion in additional funding to NCI for use during fiscal years 2009 and 2010.10 Congress required that NCI target the ARRA funding to preserve and create jobs, promote economic recovery, and increase economic efficiency through technological advances in science and health. The cancer community welcomed ARRA funding, despite the fact that the ARRA funds did not become part of the permanent baseline for the NCI and NIH budgets.

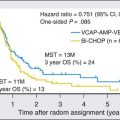

Although the national resources devoted to cancer research remain substantial, the nation is losing opportunities and efficiencies because of suboptimal funding. Despite the significant successes achieved in oncology research from the long-standing collaboration between the federal government and researchers throughout the country, the uncertainty and inconsistency in federal funding for NCI during recent years is taking a substantial toll. The aggregate funding levels for NCI and NIH have been relatively flat since the doubling of these budgets concluded in 2003 (Fig. 21-1). This stagnation has eroded the effective level of federal support for cancer research by more than 20% because of the rate of biomedical research inflation during the past decade.

One issue of particular concern is the need to restructure and improve funding for the NCI Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program. The Institute of Medicine published a report in 2010 recommending changes, and NCI is working to implement modifications designed to both streamline the research process and prioritize clinical trials with the most promise for improving patient outcomes.11 Even with these changes, increases in NCI funding are needed to ensure that clinical trials can be conducted in a timely manner to translate recent scientific discoveries into benefits for day-to-day patient care. For example, the Institute of Medicine report recommends that NCI increase the payment rate for clinical trials because the current rate only accounts for one third to half of the actual costs incurred by providers conducting clinical trials. With current funding constraints, the NCI has said that, in order to implement such a recommendation, they would have to scale back plans for new trials or reduce accrual rates to existing studies.

Patient Safeguards

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing, whether conducted for purposes of screening, diagnosis, or treatment planning, presents unique potential for discrimination. Congress enacted the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 to prohibit employers from basing employment and promotion decisions on genetic testing information.12 This federal law also bars discrimination in the health insurance market based solely on an individual’s decision regarding genetic testing and information revealed by such testing. Unfortunately, gaps remain in the protections afforded under this federal law. For example, the potential for discrimination remains in the areas of disability insurance and life insurance.

Genetic testing holds great promise to help prevent significant morbidity and mortality for persons carrying genetic risk factors for certain types of cancer. Although care must be taken to avoid unnecessary regulation, there are currently too few protections in this area. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has called upon Congress, the FDA, CMS, and the Federal Trade Commission to exercise their authority and create meaningful safeguards for the distribution, use, and marketing of genetic testing.13

Generics, Biosimilars, and Drug Shortages

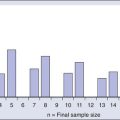

One of the most challenging issues facing the oncology community is the issue of drug shortages. During the past few years, there has been a worsening trend in which critical and often curative anticancer drugs are suddenly becoming unavailable to patients in the United States (Fig. 21-2). These shortages of important cancer drugs are increasing daily, forcing oncologists to substitute less effective treatments in many instances. Frequently, these shortages result in unacceptable delays in treatment (particularly involving pediatric cancers), increased costs to patients with cancer and, in some instances, the denial of curative therapies. These developments are quite alarming.

In the vast majority of oncology drug shortages, a generic drug is involved. By many measures, the legislation and regulations that fostered the use of generic drugs have been a success. Since the enactment of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984,14 the proportion of generic drugs used in the United States grew from less than 20% to nearly 75% over a 25-year period. By one estimate, the savings achieved for the United States health care system through the substitution of generic drugs were in excess of $1 trillion between 1999 and 2010.15

The seriousness of the drug shortages issue has attracted the attention of many policy makers in Washington, D.C. The FDA has been actively engaged in working to mitigate existing and developing shortages, and several members of Congress have introduced legislation to address this issue. President Obama signed an executive order on October 31, 2011, aimed at reducing drug shortages through such means as heightening reporting requirements for manufacturers in advance of foreseeable shortages.16 In 2012, Congress enacted legislation to help ameliorate drug shortages through a combination of manufacturing reporting requirements, direction for the FDA to reduce regulatory burdens, and means to otherwise address potential shortages.16a

At least 20 jurisdictions (including 19 states and the District of Columbia) have enacted oral parity legislation.17 Although the laws vary from state to state, oral parity legislation generally is designed to create safeguards for the financial burdens faced by individuals with cancer that may result from excessive copayments, coinsurance, deductibles, or similar requirements. Under these laws, the patient’s cost sharing for oral anticancer medications typically is limited to no more than the level that would occur under an insurance plan’s policies for intravenous and injected anticancer drugs.

Health Care Insurance

Policies adopted by the Medicare program regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer have greatly influenced both the practice of oncology and the services available to both Medicare and non-Medicare patients throughout the United States. Medicare is a federal health insurance program that provides health care coverage to persons who satisfy eligibility requirements related to age or disability. The influence of the Medicare program is due in large part to the significant size of the program, which covers approximately 60% of all patients with cancer in the United States.2 However, the influence of Medicare’s policies extends well beyond its patient population. Both public and private insurers often rely on coverage policies, reimbursement levels, and coding used by Medicare as a starting point for establishing their own policies.

However, since the late 1990s Congress enacted changes in Medicare reimbursement levels for oncology drugs and professional services that have placed significant financial and administrative burdens on cancer care providers. For example, Congress enacted provisions to control the growth of spending on all physician services through the “sustainable growth rate” under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997,18 and this blunt budgetary instrument has required multiple interventions by policy makers over the years to address the flaws in this system.

Congress enacted provisions within the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (commonly referred to as the Medicare Modernization Act) that changed the reimbursement formula for oncology drugs administered in outpatient settings.19 Despite multiple steps taken by Congress and CMS to mitigate adverse effects on oncologists, the net effect of these changes over time has contributed to the financial challenges to provide optimal care faced by many oncology practices. Policy makers often justify the various forms of cuts in payments to oncologists and other physicians on the basis that health care providers can shift the financial burdens arising from Medicare’s underreimbursements to private-sector employers and insurers. This approach is problematic in general, but it is especially difficult for oncologists who must serve increasingly large numbers of elderly (i.e., Medicare) patients.

Congress enacted multiple safeguards over the years to protect persons with cancer. For example, Congress enacted provisions in 1993 requiring Medicare to cover off-label uses of drugs and biologicals if such uses were supported by clinical evidence reflected in the peer-reviewed medical literature or specific compendia.20 This patient safeguard has been critically important during the past two decades because pharmaceutical companies are unlikely to seek FDA approval for multiple supplemental indications that support the most important therapeutic agents.

Congress enacted a number of changes to Medicare under the ACA, including the creation of a new center within Medicare called the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (the Innovation Center).1 Congress vested broad authority in the Innovation Center to test and expand the use of innovative approaches to reimbursement under Medicare without the need for further action by Congress. In the future, the Innovation Center could test and implement new oncology payment models under this authority. As part of the ACA, Congress suggested but did not require that the Innovation Center conduct a treatment planning project. This demonstration would focus on cancer care and provide financial incentives for treatment planning and follow-up care planning in the context of cancer care guidelines.

Perhaps the most high-profile project involving the Innovation Center is the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which relies on the establishment of accountable care organizations (ACOs).1 ACOs operate under the traditional fee-for-service rules for Medicare Part B. However, the Medicare program will share the savings achieved by ACOs if the aggregate costs incurred by Medicare for the ACO’s assigned Medicare beneficiaries falls below an established benchmark. ACOs are required to meet a minimum set of performance measures. In an attempt to avert the economic incentive that could exist for providers to undertreat patients, one of these measures would assess whether ACOs are permitting patients to access specialists, however there are no performance measures that provide any meaningful assessment of treatment for cancer. In general, Medicare beneficiaries have the autonomy to seek care from any physician at any time, and ACO physicians have no authority to limit the beneficiary from visiting other health care professionals (whether inside or outside of the ACO).

One can view the ACO program as the logical extension of a prior demonstration conducted by CMS. From 2005 to 2010, CMS conducted the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration. Under this demonstration, CMS shared the savings achieved with the participating physician groups. CMS used performance measures focusing on diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and preventive care. Several physician groups succeeded in sharing a portion of the cost savings achieved for the Medicare program.21

The ACA also includes a safeguard to ensure that persons with cancer and other life-threatening conditions are covered under private insurance if they determine with their physicians that enrolling in a clinical study is in their best interest.1 The legislation requires insurers to cover the routine costs of care associated with qualifying phases I, II, III, and IV clinical trials. Ensuring that patients with cancer can access clinical trials is not solely focused on promoting research, because it is a long-standing and firmly held belief in oncology that the option to participate in a clinical trial is a key component of high-quality cancer care and should be a readily accessible option for any patient with cancer. In many instances, clinical trials provide persons with cancer with the best chance for a successful outcome. The ACA safeguard for patients who need access to clinical trials is similar to a protection that already exists for Medicare beneficiaries.