Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Mark J. Roschewski and Wyndham H. Wilson

• Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is the most common hematologic malignancy; more than 70,000 were estimated to be diagnosed in the United States in 2012. Diffuse large B-cell (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) are the most common subtypes, each comprising approximately one third of cases in the Western Hemisphere.

• In the Western hemisphere, approximately 85% of lymphomas are of B-cell origin and 15% are of T-cell/natural killer-cell origin. T-cell lymphomas have a higher incidence in parts of Asia.

• Etiology of most lymphomas is complex and multifactorial. Defects in host immunity that increase the risk and infections associated with NHL include Helicobacter pylori, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I (HTLV-I), hepatitis C, and human herpesvirus–8 (HHV-8).

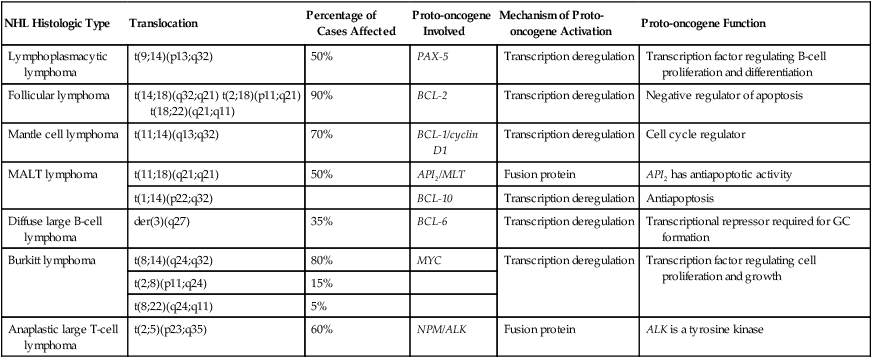

• Specific genetic abnormalities associated with lymphomas include translocations of BCL-2 (t(14;18)) in FL and DLBCL; BCL-6 (t(3;16)) in DLBCL; BCL-10 (t(11;18)) in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; MYC (t(8;14), t(2;8), t(8;22) in Burkitt lymphoma and subsets of DLBCL; BCL-1 (t(11;14)) in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); and ALK (t(2;5)) in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) + anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma (ALCL).

• Gene expression profiling can subdivide the largest group of lymphomas, DLBCL, into three subtypes with distinct pathogenetic mechanisms and decidedly different prognoses.

• Excisional biopsy is preferred for initial diagnosis and should be reviewed by an experienced hematopathologist. Fresh-frozen tissue should be collected for additional studies.

• World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lymphoid Malignancies recognizes lymphomas that may be unclassifiable with morphologic features alone. Clinical and molecular features are essential for subclassification of lymphomas.

• Staging evaluation includes patient history and physical examination; complete blood cell count and chemistry studies including lactate dehydrogenase; computed tomography (CT) of chest, retroperitoneum, and pelvis; and bone marrow biopsy. Positron emission tomography (PET) aids in the detection of extranodal disease and is more sensitive than CT alone.

• Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20, is an essential component of the front-line and relapsed treatment of B-cell lymphomas.

• Treatment of indolent lymphomas such as follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is for palliative benefit and is not curative; treatment is frequently curative for DLBCL, ALK+ ALCL, Burkitt lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma; and proper dose-intensity of therapy is essential.

• MCL demonstrates remarkable clinical heterogeneity; no curative therapy exists, but a subset of patients can have a long indolent course without therapy.

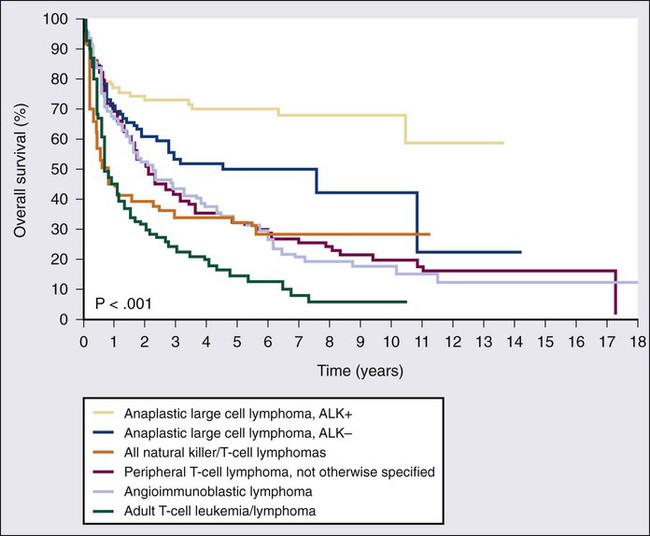

• Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) other than ALK+ ALCL have a poor prognosis and are difficult to cure with standard therapy.

• High-dose therapy with stem cell transplant cures a smaller fraction of patients with relapsed aggressive lymphomas in the rituximab era.

• Numerous novel agents that have been developed on the basis of biological targets of lymphoma subtypes are demonstrating significant promise.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Incidence, Distribution, and Death Rates

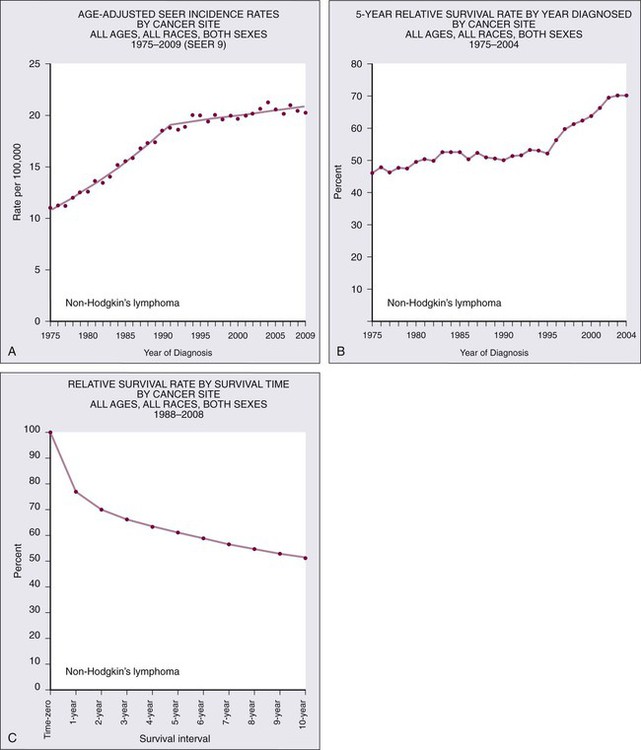

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic malignancy, with an estimated 70,130 cases diagnosed in the United States in 2012.1 One in 47 men and women will be diagnosed with NHL during their lifetime, with B-cell lymphomas representing 80% to 85% of those cases and T-cell lymphomas comprising the remainder. NHL is the seventh most common malignancy in the United States with a slight male predominance.2 Even though NHL affects all ages, its incidence increases steadily with each decade of life between ages 20 to 80, with a median age of 66. Whites have the highest incidence of NHL, followed by Hispanics, blacks, and Asians, and it is least commonly diagnosed in Native Americans/Alaska natives. From the early 1970s to the 1990s, the annual percent change in the incidence of NHL in the United States increased steadily at a compound rate of almost 4%, partly the result of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and improved diagnostic techniques, but has been stable between 2004 and 2009 (Fig. 106-1A).

NHL is the eighth most commonly diagnosed malignancy worldwide.3 It is more commonly diagnosed in developed areas, with the highest incidence rates in North America, Australia, and Europe and the lowest rates in Asia and the Caribbean.3 Outcomes have improved, with death rates from NHL declining recently. The 5-year relative survival rate for all cases of NHL increased to 70% in 2001 through 2007 compared with 51% in the 1980s and 47% in the 1970s; 10-year survival rates are now slightly above 50% (see Fig. 106-1B and C). Although the majority of people who die of NHL are older than 75 years, it remains the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in persons aged 20 to 39 years.1

Risk Factors and Predisposing Conditions

The sequence of events that results in NHL is unknown. Inherited genetic susceptibility and/or shared environmental exposures is suggested by registry-based studies that demonstrate slightly increased risk of developing NHL in first-degree relatives of patients with lymphoma and patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).4,5 No germline mutations have been identified, and the majority of patients with NHL have no familial clustering. Many factors related to the host’s immune status combined with environmental exposures such as organic solvent exposure and wood products correlate with an increased risk of NHL (Box 106-1).6,7 Conflicting reports exist on the connection between exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, vitamin D levels, and the lifetime risk of NHL.8

Rare, extranodal T-cell lymphomas are also encountered in the setting of immunologic defects. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATCL) often occurs in the setting of celiac sprue, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) occurs in young men with a history of solid-organ transplantation or other immune defects.9 The current World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphomas recognizes a subset of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) that arise as a consequence of chronic inflammation and are frequently associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).10 The classic example is pyothorax-associated lymphoma, which was first reported in 1987 in patients treated for tuberculosis by artificial pneumothorax. Other cases of DLBCL may occur in the setting of chronic inflammation, such as chronic skin ulcers or osteomyelitis.11

The role of chronic immune stimulation is less ambiguous in infection-associated lymphomas, such as in lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in which the lymphoproliferation is frequently antigen driven.12–15 Evidence for the essential role of the chronic immune stimulation is that eradication of the underlying infection, such as chronic hepatitis C or Helicobacter pylori, can result in remission in many cases.18–18 Viruses may also function as co-factors in lymphomagenesis, whereby they may exert their effect through genomic integration, which leads to alterations in gene expression, and/or by directly affecting cellular proliferation. EBV, human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I (HTLV-I), and human herpesvirus–8 (HHV-8), in particular, have well-established oncogenic roles in subtypes of NHL.19–22 In the case of EBV, it appears to have a direct oncogenic role in lymphomas of immunocompromised patients, such as those infected with HIV and in the posttransplant period.11 HTLV-I has a direct role in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), but carriers have only a 2% to 5% lifetime risk of developing disease with a latency period of 30 to 40 years. HHV-8, also known as Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV), has been associated with primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), which is a rare B-cell lymphoma that occurs primarily in highly immunosuppressed patients with AIDS who are often co-infected with EBV.23

Diagnosis and Classification

The crucial step in ensuring an accurate pathological diagnosis is an adequate tissue biopsy. Attention should be paid to the biopsy site with the largest or most rapidly enlarging node, or functional imaging such as combined fluorodeoxyglucose-labeled positron emission tomography and computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) may be used to guide biopsy sites.24 In most cases, fine-needle aspiration is insufficient for initial diagnosis because lymph node architecture is usually critical for diagnosis.25 Excisional lymph node biopsies are preferred, but multiple core needle biopsies can be adequate in situations in which involved nodes are not easily accessible. Clinicians must have a low threshold for re-biopsy in circumstances in which the original biopsy is nondiagnostic or ambiguous. Re-biopsy should be performed in most situations of suspected relapse because inflammatory conditions can radiographically mimic lymphoma and it is not uncommon for indolent lymphomas to transform their histology.

Classification of Lymphomas

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases with a variety of natural histories. Histologic classification schemes have been developed to organize lymphomas into groups with shared pathogenesis and clinical behavior with an aim to guide treatment. The classification systems for lymphomas have changed frequently and dramatically since they were first introduced in the 1950s and continue to evolve with technologic advances and scientific discovery. These classifications have evolved from exclusively morphologic to the current working system that incorporates immunophenotype and hallmark genetic abnormalities. The most recent version of the WHO classification system in 2008 places great emphasis on molecular and cytogenetic abnormalities in conjunction with clinical variables to define individual subtypes (Box 106-2).

History of Lymphoma Classification Systems

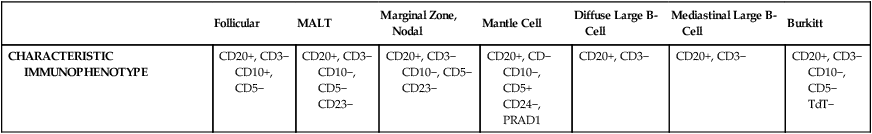

In 1956, Henry Rappaport of the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology proposed a simple system of lymphomas based on the growth pattern of the disease (nodular vs. diffuse) as well as the predominant cell’s well-differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, or histiocytic appearance. With the use of this system, nodular lymphomas composed of small lymphocytes were generally considered indolent disorders whereas so-called histiocytic lymphomas were aggressive. The Rappaport system was used until the 1970s when the American pathologists L.J. Lukes and R.D. Collins and the German pathologist Karl Lennert each proposed classification systems that reflected advances in cellular immunology, cell morphology, and lymphocyte lineage by dividing entities into B-cell and T-cell disorders on the basis of their cell surface markers.26,27 The immune phenotype proved fundamental for the accurate classification of lymphoma, with early studies showing that most lymphomas are of B-cell origin (Table 106-1), but these studies still did not address clinical concerns and were not uniformly embraced.

Table 106-1

Typical Immunophenotype of Major Subtypes of B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas

| Follicular | MALT | Marginal Zone, Nodal | Mantle Cell | Diffuse Large B-Cell | Mediastinal Large B-Cell | Burkitt | |

| CHARACTERISTIC IMMUNOPHENOTYPE | CD20+, CD3− CD10+, CD5− |

CD20+, CD3− CD10−, CD5− CD23− |

CD20+, CD3− CD10−, CD5− CD23− |

CD20+, CD− CD10−, CD5+ CD24−, PRAD1 |

CD20+, CD3− | CD20+, CD3− | CD20+, CD3− CD10−, CD5− TdT− |

In 1994, the International Lymphoma Study group developed a consensus list of diseases that could be recognized by pathologists and was codified in the Revised European–American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL) classification system; this ultimately became the WHO classification system and is the recognized standard today.28 The first WHO classification, published in 2001, defined diseases by four features: morphology, immunophenotype, molecular genetic characteristics, and clinical information,29 whereas the updated 2008 version places greater emphasis on distinctive immunologic and molecular profiles of lymphomas and emphasizes the importance of clinical characteristics.30

Molecular Genetics of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Insight into the genetic features that characterize tumor subtypes has aided in the diagnosis of lymphomas and identification of potential therapeutic targets. A variety of complementary technologies can measure the expression of thousands of genes on a solid platform, termed molecular profiling, and can link biology to a genetic expression signature. The application of gene expression profiling (GEP) to lymphoma has provided insights into unique molecular signatures of distinct types of B-cell malignancies31 and can relate lymphoid neoplasms to normal stages in B-cell development and physiology. This approach has provided a new way to classify lymphomas and predict clinical outcome.

Molecular profiling has advanced the understanding of lymphomagenesis through identification of genes important in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.32–36 At a molecular level, genetic lesions identified in lymphomas include oncogene activation or loss of tumor suppressor genes caused by chromosomal translocation, deletion or mutation, or the integration of viral genomes (Table 106-2). Some lymphomas rely on the continuous signaling provided by these oncogenes, termed oncogene addiction, whereas others seem more reliant on signaling pathways not controlled by oncogenes, termed non-oncogene addiction.37 GEP has also helped define the molecular makeup of the nonmalignant cells in tumor specimens, the so-called microenvironment that is important for pathogenesis and may include potential therapeutic targets.38,39

Table 106-2

Major Molecular Translocations in Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas

| NHL Histologic Type | Translocation | Percentage of Cases Affected | Proto-oncogene Involved | Mechanism of Proto-oncogene Activation | Proto-oncogene Function |

| Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma | t(9;14)(p13;q32) | 50% | PAX-5 | Transcription deregulation | Transcription factor regulating B-cell proliferation and differentiation |

| Follicular lymphoma | t(14;18)(q32;q21) t(2;18)(p11;q21) t(18;22)(q21;q11) | 90% | BCL-2 | Transcription deregulation | Negative regulator of apoptosis |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | 70% | BCL-1/cyclin D1 | Transcription deregulation | Cell cycle regulator |

| MALT lymphoma | t(11;18)(q21;q21) | 50% | API2/MLT | Fusion protein | API2 has antiapoptotic activity |

| t(1;14)(p22;q32) | BCL-10 | Transcription deregulation | Antiapoptosis | ||

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | der(3)(q27) | 35% | BCL-6 | Transcription deregulation | Transcriptional repressor required for GC formation |

| Burkitt lymphoma | t(8;14)(q24;q32) | 80% | MYC | Transcription deregulation | Transcription factor regulating cell proliferation and growth |

| t(2;8)(p11;q24) | 15% | ||||

| t(8;22)(q24;q11) | 5% | ||||

| Anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma | t(2;5)(p23;q35) | 60% | NPM/ALK | Fusion protein | ALK is a tyrosine kinase |

MALT, Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; GC, gastric cancer.

Gray Zone Lymphomas

Cases exist that cannot be classified with certainty. The term gray zone lymphoma was first introduced in 1998 for cases that shared morphologic and immunophenotypic features of Hodgkin lymphoma and DLBCL.40 It has been demonstrated that primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) has an overlapping gene expression profile with nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL).41,42 Given that PMBL and NSHL exhibit clinical and biological overlap, the term mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) was first used in 2005 by Traverse-Glehen and colleagues to identify those cases with features intermediate between PMBL and NSHL.43 The term has more than theoretical interest because MGZL has an inferior prognosis with contemporary therapies.44,45 As such, the 2008 version of the WHO classification system includes a provisional category of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma that includes these cases of MGZL.

Similarly, the distinction between high-grade lymphomas such as DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) can be challenging on morphologic and immunophenotypic grounds.46 The distinction between the two entities is critical, because patients with BL require high-intensity chemotherapy. Two studies have demonstrated that BL has a unique molecular profile and that a subset of cases classified as DLBCL have a BL molecular profile.47,48 It is now appreciated that between 8% and 10% of cases of newly diagnosed DLBCL will harbor a mutation in the MYC oncogene and have a poor outcome with R-CHOP (rituximab + cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).49,50 Some cases of MYC+ DLBCL may have dual translocations affecting both MYC and BCL-2, which portends an even worse outcome.51–54 The WHO 2008 classification includes a provisional category for these cases that is referred to as “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma.”

Staging and Prognosis

Principles of Evaluation and Staging

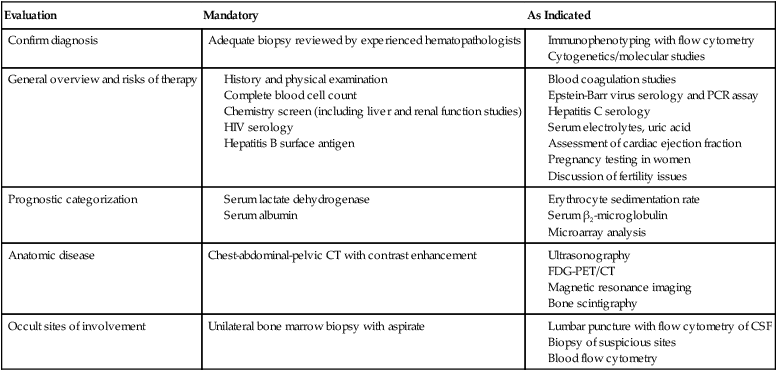

Accurate staging is essential for determining optimal management and prognosis. Initial evaluation begins with a history focused on the pace of signs or symptoms suggestive of lymphoma, the presence or absence of “B symptoms” (fevers, chills, drenching night sweats), possible sites of nodal and extranodal involvement, and assessment of possible underlying immunodeficiency. A history of exposure to pathogens including HIV, EBV, hepatitis C, and HTLV-I should specifically be addressed. Medication history is important, with emphasis on history of exposure to immunosuppressive agents such as chemotherapy, tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors, or corticosteroids. When performing the physical examination, the physician should assess for hepatosplenomegaly and examine Waldeyer’s ring, epitrochlear nodes, and popliteal nodes, which may be difficult to measure on radiographic imaging. Extranodal involvement such as the skin should be closely examined. Laboratory tests should include a complete blood cell count (CBC) and serum chemistry with determination of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. HIV and serologic tests for hepatitis B and C are needed regardless of reported exposure history. Viral tests such as for HTLV-I should be done in high-risk populations, whereas EBV viral loads may have prognostic value in specific lymphomas such as PTLDs and extranodal NK-cell/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type.55 Serum β2-microglobulin has prognostic implications for many lymphomas. Recommended tests that supplement the history and physical examination are listed in Table 106-3.

Table 106-3

Evaluation of a New Patient with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Evaluation | Mandatory | As Indicated |

| Confirm diagnosis | Adequate biopsy reviewed by experienced hematopathologists |

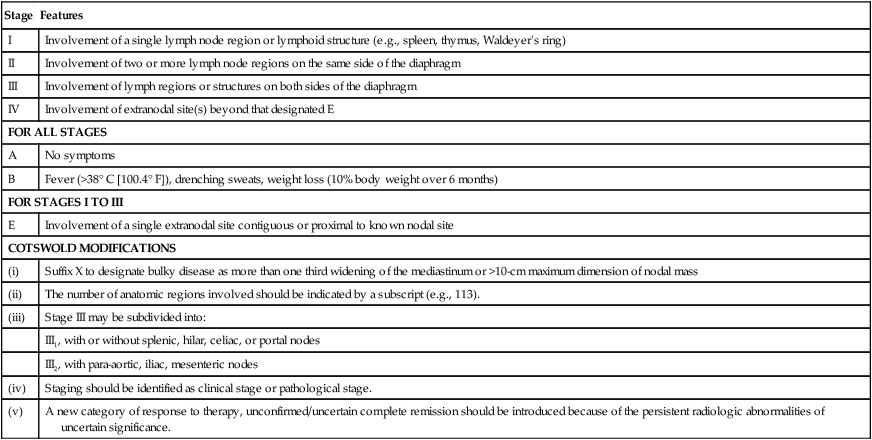

The Ann Arbor staging system that was developed for Hodgkin lymphoma is the standard, but NHL does not spread along contiguous nodes as seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Table 106-4). Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is standard for assessing sites involved with lymphoma. Lymph nodes are considered involved if the long axis is 1.5 cm or more or if the long axis is 1.1 cm or longer and the short axis is more than 1.0 cm. Lymph nodes that are less than or equal to 1.0 cm in both axes are considered uninvolved.56 Pitfalls in determining disease stage based on anatomic imaging alone is that enlarged nodes may not be involved with lymphoma, and extranodal sites of disease such as bone or skin involvement may be missed. Involvement of the bone is best evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and FDG-PET scans. A head MR image and lumbar puncture with evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by cytology and flow cytometry57 should be performed in high-risk patients or if there are signs or symptoms suggestive of central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Patients at high risk for CNS involvement include those with extranodal involvement and those with highly aggressive lymphomas such as BL and precursor lymphoid neoplasms.49,50,58,59 Bone marrow involvement impacts both management and prognosis60 and should be assessed in all patients with NHL. It is not uncommon to find discordant lymphoma subtypes in the bone marrow and biopsy samples.61

Table 106-4

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Ann Arbor Staging Classification and the Cotswold Modifications

| Stage | Features |

| I | Involvement of a single lymph node region or lymphoid structure (e.g., spleen, thymus, Waldeyer’s ring) |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

| III | Involvement of lymph regions or structures on both sides of the diaphragm |

| IV | Involvement of extranodal site(s) beyond that designated E |

| FOR ALL STAGES | |

| A | No symptoms |

| B | Fever (>38° C [100.4° F]), drenching sweats, weight loss (10% body weight over 6 months) |

| FOR STAGES I TO III | |

| E | Involvement of a single extranodal site contiguous or proximal to known nodal site |

| COTSWOLD MODIFICATIONS | |

| (i) | Suffix X to designate bulky disease as more than one third widening of the mediastinum or >10-cm maximum dimension of nodal mass |

| (ii) | The number of anatomic regions involved should be indicated by a subscript (e.g., 113). |

| (iii) | Stage III may be subdivided into: |

| III1, with or without splenic, hilar, celiac, or portal nodes | |

| III2, with para-aortic, iliac, mesenteric nodes | |

| (iv) | Staging should be identified as clinical stage or pathological stage. |

| (v) | A new category of response to therapy, unconfirmed/uncertain complete remission should be introduced because of the persistent radiologic abnormalities of uncertain significance. |

FDG-PET exploits the enhanced rate of glucose utilization in tumor cells compared with normal surrounding cells, a process known as the “Warburg effect.”62 FDG-PET provides a semi-quantitative measurement of tumor involvement in NHLs that has superior sensitivity to anatomic imaging.63 FDG uptake is dependent on several variables and is subject to interpretation. Nonetheless, FDG-PET is commonly used for staging of the disease of patients with newly diagnosed aggressive lymphomas, but its impact on treatment decisions is unclear.

Prognostic Factors for Lymphoma

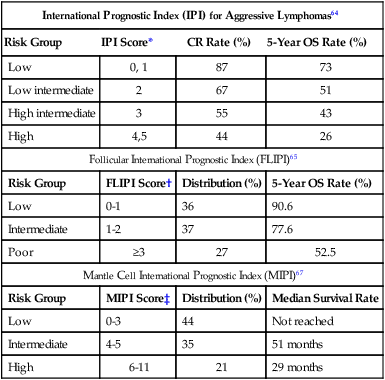

Clinical variables are powerful and independent predictors of outcome. A number of prognostic indices aid in the prognosis of individual NHL subtypes.64–67 An international project identified that inferior outcome was related to age older than 60 years, stage III or IV disease, serum LDH value above normal range, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or higher, and involvement of two or more extranodal sites. A clinical prognostic model, termed the International Prognostic Index (IPI), was developed with these five factors and stratifies patients into quartiles with differing disease-free survival rate at 5 years (Table 106-5). The IPI is the standard for assessing prognosis in DLBCL, as well as for comparison between clinical trials. Because the IPI was developed before use of rituximab, a revised IPI was suggested, but it was not validated in a larger prospective study.68,69

Table 106-5

| International Prognostic Index (IPI) for Aggressive Lymphomas64 | |||

| Risk Group | IPI Score* | CR Rate (%) | 5-Year OS Rate (%) |

| Low | 0, 1 | 87 | 73 |

| Low intermediate | 2 | 67 | 51 |

| High intermediate | 3 | 55 | 43 |

| High | 4,5 | 44 | 26 |

| Follicular International Prognostic Index (FLIPI)65 | |||

| Risk Group | FLIPI Score† | Distribution (%) | 5-Year OS Rate (%) |

| Low | 0-1 | 36 | 90.6 |

| Intermediate | 1-2 | 37 | 77.6 |

| Poor | ≥3 | 27 | 52.5 |

| Mantle Cell International Prognostic Index (MIPI)67 | |||

| Risk Group | MIPI Score‡ | Distribution (%) | Median Survival Rate |

| Low | 0-3 | 44 | Not reached |

| Intermediate | 4-5 | 35 | 51 months |

| High | 6-11 | 21 | 29 months |

*One point is given for the presence of each of the following characteristics: age > 60 years, elevated serum LDH level, ECOG performance status ≥ 2, Ann Arbor stage III or IV, and more than two extranodal sites.

†One point is given for the presence of each of the following characteristics: age > 60 years, elevated serum LDH level, hemoglobin level < 12 g/dL, Ann Arbor stage III or IV, and number of nodal sites ≥ 5.

‡Points are based on age, ECOG performance status, white blood cell count, and serum LDH level.

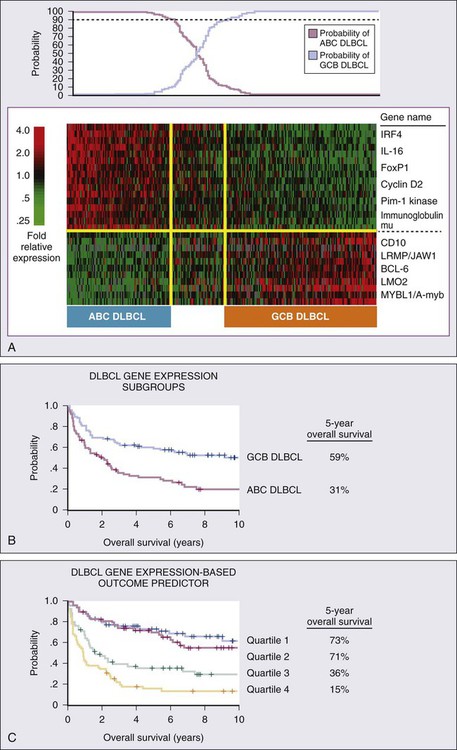

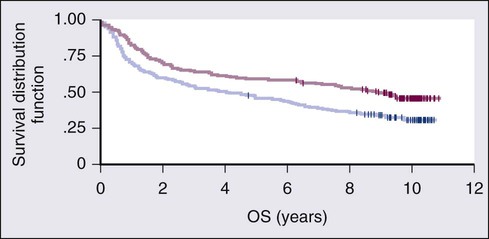

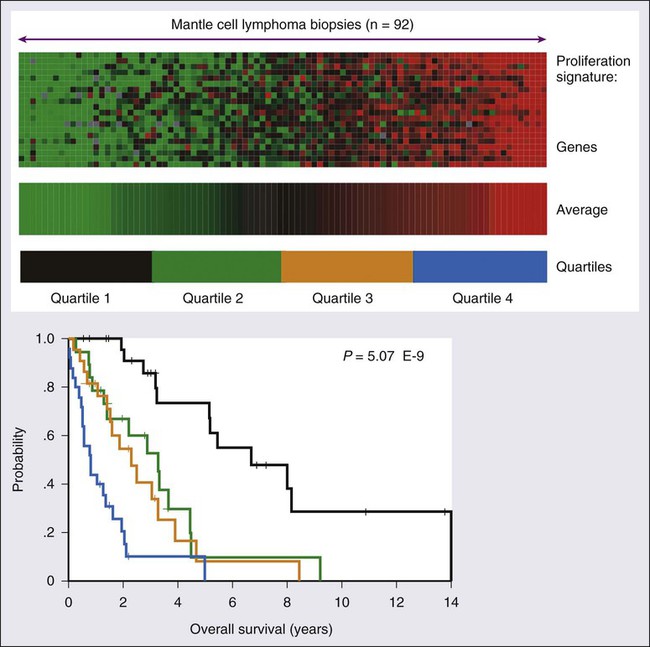

Gene expression profiling (GEP) is also an important prognostic tool that demonstrates molecular heterogeneity within tumors. In DLBCL, for example, morphologically indistinguishable tumors show marked heterogeneity in gene expression and these patterns of expression correspond to the cellular origin of the lymphoma according to its stage of differentiation.70 DLBCL can thereby be divided into at least three different subtypes: germinal center B-cell (GCB)-like, activated B-cell (ABC)-like, and PMBL that arise by distinct pathogenetic mechanisms and have a very different prognosis.38,42,71,72 A molecular prognostic model of survival based on signatures of germinal center B cells, proliferating cells, reactive stromal and immune cells in the lymph node, and major histocompatibility complex class II cells, was developed for CHOP-treated DLBCL.71 Overall survival (OS) was superior in patients with the GCB-type compared with the ABC-type DLBCL, a finding that was independent of the IPI (Fig. 106-2). The distinction between GCB-like and ABC-like subtypes of DLBCL carries prognostic information in patients treated with rituximab-containing regimens.34 Wilson and associates demonstrated that treatment with dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) resulted in a 5-year progression-free survival rate (PFS) of 100% for GCB-like DLBCL compared with 67% for non–GCB-type DLBCL.73 In relapsed DLBCL, different responses were observed in bortezomib-containing regimens.74 The gene expression profiles of follicular lymphoma (FL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) have also identified subgroups with different prognosis on the basis of cellular proliferation75 and tumor-infiltrating cells.39

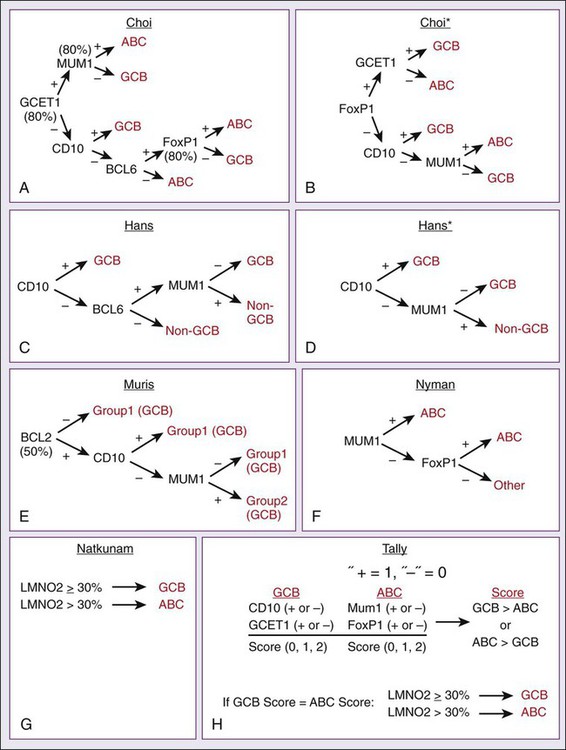

GEP is impractical to perform on all patients with newly diagnosed lymphomas, so multiple immunohistochemical (IHC) models using combinations of antibodies have been developed to predict GCB and non-GCB subtypes of DLBCL.76–80 The concordance rate with GEP is variable, however, ranging between 74% and 93%.81 The “Tally” algorithm in which results are not analyzed in a specific order demonstrated the best concordance with GEP at 93% (Fig. 106-3). IHC models will require further validation and standardization but have the advantage of being widely available.

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are short noncoding regions of the RNA that regulate gene expression and have been used to discriminate between normal cells and cancer cells.82 Recently a 9-miRNA signature was shown to separate cell lines derived from GCB and ABC-like subtypes of DLBCL.83 MiRNA profiling demonstrates promise in predicting outcomes in DLBCL,84 FL,85 and MCL86 and will require further study and validation.

Response Assessment

Accurate assessment of response to therapy is critical, particularly in curable lymphomas. Treatment response should be documented by physical findings, and all abnormal tests should be repeated. End-of-therapy assessment is usually performed 3 to 6 weeks after completion of therapy unless progression is suspected earlier. An International Working Group (IWG) workshop held under the auspices of the National Cancer Institute in 1998 standardized response criteria based on the bi-dimensional measurements of involved nodal groups.87 The spleen is considered to be a nodal site and is assessed by CT. Focal lesions in the liver are considered measurable. Patients with bone marrow involvement before initiating therapy are required to be morphologically free of lymphoma to be considered in complete remission.

The response criteria were updated in 2007 and state that if all involved nodes have regressed to 1 cm or less, symptoms of disease have disappeared, and bone marrow biopsy is without involvement, the patient is in complete remission.56 Because residual necrotic tissue and inflammatory cells may prevent bulky nodes from reducing to 1 cm or less, FDG-PET can help distinguish residual tumor cells from tissue necrosis. The timing of the imaging after therapy affects the positive predictive value, and it is recommended that FDG-PET be performed 3 to 8 weeks after chemotherapy and 8 to 12 weeks after radiation therapy.88 In patients with bulky mediastinal lymph nodes, FDG-PET confirmation of a complete response is essential because these nodes frequently do not completely regress.

Management

Indolent Lymphomas of B-Cell Origin

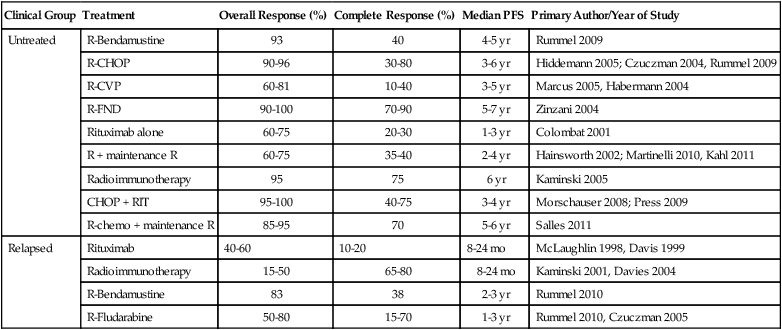

Indolent B-cell lymphomas are characterized by a relapsing and remitting natural history. Intermittent therapy is required to control clinical signs and symptoms but is not curative in most cases. Many classes of chemotherapy are effective, including anthracyclines, purine analogs, and alkylators. Immunotherapy such as with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab and the radioimmunoconjugates ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) and iodine-131 (131I)–labeled tositumomab (Bexxar) is highly effective both as single-agent therapy and in combination with chemotherapy (Table 106-6). Clinical observation without treatment (“watchful waiting”) is an important strategy for asymptomatic patients with low tumor burden because spontaneous remission occurs in 8% to 10% of patients, no curative therapy exists, early treatment has not been shown to improve survival, and patients may not experience symptoms for months or years. Indications to initiate treatment of indolent lymphomas are bothersome symptoms, organ compromise, and/or evidence of rapid tumor growth.

Table 106-6

Treatment Outcomes in Indolent Lymphoma

| Clinical Group | Treatment | Overall Response (%) | Complete Response (%) | Median PFS | Primary Author/Year of Study |

| Untreated | R-Bendamustine | 93 | 40 | 4-5 yr | Rummel 2009 |

| R-CHOP | 90-96 | 30-80 | 3-6 yr | Hiddemann 2005; Czuczman 2004, Rummel 2009 | |

| R-CVP | 60-81 | 10-40 | 3-5 yr | Marcus 2005, Habermann 2004 | |

| R-FND | 90-100 | 70-90 | 5-7 yr | Zinzani 2004 | |

| Rituximab alone | 60-75 | 20-30 | 1-3 yr | Colombat 2001 | |

| R + maintenance R | 60-75 | 35-40 | 2-4 yr | Hainsworth 2002; Martinelli 2010, Kahl 2011 | |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 95 | 75 | 6 yr | Kaminski 2005 | |

| CHOP + RIT | 95-100 | 40-75 | 3-4 yr | Morschauser 2008; Press 2009 | |

| R-chemo + maintenance R | 85-95 | 70 | 5-6 yr | Salles 2011 | |

| Relapsed | Rituximab | 40-60 | 10-20 | 8-24 mo | McLaughlin 1998, Davis 1999 |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 15-50 | 65-80 | 8-24 mo | Kaminski 2001, Davies 2004 | |

| R-Bendamustine | 83 | 38 | 2-3 yr | Rummel 2010 | |

| R-Fludarabine | 50-80 | 15-70 | 1-3 yr | Rummel 2010, Czuczman 2005 |

All indolent lymphomas maintain a perpetual risk of transforming into a more aggressive disease. The estimated risk is 20% at 5 years and 30% at 10 years for patients with follicular lymphoma.89 No biomarkers reliably predict which patients will undergo such histologic transformation, and these transformed lymphomas are more difficult to manage than de novo aggressive lymphomas.89,90

The prototypical indolent lymphoma is FL, and the principles applied to the diagnosis and management of FL can be applied to other indolent NHLs. Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is biologically identical to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and is considered separately in Chapter 102.

Follicular Lymphoma

The genetic hallmark of FL is the t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation, which is present in 80% to 90% of cases and places the BCL-2 oncogene under the control of the IgH enhancer. This leads to impaired cellular apoptosis and overexpression of the BCL-2 gene product.91 Inhibition of apoptosis by BCL-2, which occurs in normal germinal center cells, appears to play an important role in lymphomagenesis.92 However, constitutive BCL-2 expression is not necessarily required for survival because it may be turned off in FL cells that have undergone aggressive transformation.93

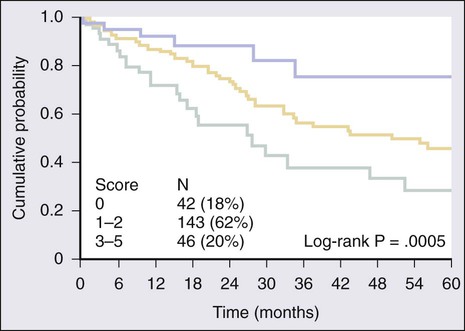

Most indolent lymphomas are of follicular histology and classified into three grades based on the number of centroblasts. Grades 1 and 2 exhibit an indolent clinical course, but grade 3 FL is biologically diverse and includes both grade 3a and grade 3b, which has a follicular growth pattern but clinically behaves like DLBCL.94 On the basis of multivariate analysis collected on more than 4000 patients, a five-variable prognostic index was constructed known as the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) (see Table 106-5). The variables associated with outcomes included age older than 60 years, Ann Arbor stage III or IV, hemoglobin level less than 12 g/dL, abnormal serum LDH level, and involvement of five or more lymph node areas.65 The scoring system of the FLIPI was found to predict outcomes in FL better than the IPI, but it is based on a cumbersome method of determining the number of nodal sites involved (Groupe d’Études des Lymphomes Folliculaires [GELF] criteria) and predated the use of rituximab, which may render its use obsolete. An international project, termed the F2 study, was conducted on more than 1000 patients with newly diagnosed FL and all treated with rituximab-based regimens using the PFS as the end point.66 The F2 study identified three risk groups based on age, hemoglobin value, serum β2-microglobulin, bone marrow involvement, and the longest diameter of the largest involved lymph node (see Table 106-5).66 The high-risk group in this model had a 3-year PFS of 51%, whereas those with no risk factors had a 3-year PFS of 91% (Fig. 106-4). The F2 study uses clinical variables derived from patients treated with rituximab, but validation of its prognostic value with current treatment strategies will be required. Neither the FLIPI nor the F2 study defines which patients should be treated at the time of diagnosis.95

Localized Follicular Lymphoma

Fifteen to 25% of FL cases are diagnosed at stage I or II. Radiation therapy alone has been the standard of care in this population, with 50% to 65% of patients showing no progression of their disease at 10 years.96,97 Additionally, relapses appear to be rare 10 years after treatment.97 It is not clear, however, if these results reflect the curative potential of radiation therapy or the indolent natural history of early-stage low-burden disease. One retrospective analysis of 43 patients with untreated stage I or II FL found that 63% did not require therapy during a median follow-up time of 86 months and only 4 patients showed histologic transformation; the 10-year estimated survival rate was 85%.98 Thus, it is difficult to make firm recommendations regarding treatment. The National LymphoCare Study analyzed practice patterns in both academic and community centers in the United States regarding therapy delivered to patients with newly diagnosed FL.99 Radiation therapy alone was chosen in 23.4% of patients with stage I disease, whereas observation was chosen in 28.7%.99 The most common treatment was chemotherapy, with rituximab given more than 30% of the time. When considering treatment options for early-stage FL, it is important for the clinician to recognize that there is no clear best option and that treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

Advanced Follicular Lymphoma

The majority of patients with FL have advanced-stage disease, and they are not candidates for radiation therapy alone. Watchful waiting is appropriate until symptoms emerge or the disease threatens organ function. Careful attention should be placed on the pace of the disease and signs of histologic transformation. Watchful waiting is used in only 17.7% of patients with newly diagnosed FL in the United States.99 A randomized study of single-agent rituximab therapy versus watchful waiting in nonbulky FL demonstrated that early treatment with rituximab improves the median time to initiation of therapy, but the effect of this benefit is unclear.100 All available data suggest that early administration of therapy does not improve OS and carries inherent risks that observation does not.

The most important advance in indolent lymphomas is rituximab, and it has revolutionized the treatment of FL since its introduction. Rituximab as a single agent in therapy for FL is a viable option for infirm patients because it has manageable toxicities. Extended-duration therapy for patients who initially respond may be an effective strategy and appears to be safe. In 41 untreated patients with FL and CLL/SLL, rituximab yielded an overall response rate of 54% after four weekly infusions, including 15% complete remissions.101 Patients who responded to rituximab were subsequently treated with maintenance therapy of four weekly infusions every 6 months; this treatment was continued for as long as 2 years in those patients without progression. The response rate was 47% after induction with an increase to 73% during maintenance, and the median PFS was 34 months.102 In another study, treatment with eight versus four doses of rituximab demonstrated a significant improvement in event-free survival (EFS) in the extended dosing arm, and an impressive 45% of patients had not experienced an event at 8 years.103 Scheduled maintenance doses of rituximab were compared with reserving re-treatment for progression of disease in the RESORT trial.104 In this trial, 384 patients with untreated low tumor burden FL were given four doses of rituximab. Responding patients were then randomized to four more doses given 3 months apart versus deferred therapy until evidence of disease progression. There was no observable difference in time-to-treatment-failure in either group, suggesting that extended dosing may have no advantage over re-initiating therapy at the time of progression in FL.104 Of note, rituximab monotherapy is not effective for patients with bulky nodes and is most effective for patients with low tumor burden and/or those who are not candidates for combination chemotherapy.

Rituximab can be safely added to combination chemotherapy regimens and results in improvements in response and PFS. Many immunochemotherapy regimens exist for the treatment of indolent lymphoma (see Table 106-6). All regimens produce excellent initial responses but vary in the duration of response and toxicities. In the first study of R-CHOP in mostly untreated patients with indolent lymphoma, the overall response rate was 95%, including 55% complete response rate with an 82-month median PFS.105 Hiddemann and colleagues performed a randomized study of CHOP versus R-CHOP in 428 patients with symptomatic advanced-stage FL.106 Patients in whom the disease responded to therapy were offered a second randomization after treatment to stem cell transplantation or interferon-α maintenance. With a median follow-up of 18 months, patients in the R-CHOP arm had a 60% reduction in risk of treatment failure and an improvement in OS. Dose intensity is not as important in indolent lymphomas as in aggressive lymphomas. In a randomized study of 300 patients with advanced-stage indolent lymphomas, R-CHOP given in 21-day cycles (R-CHOP-21) was compared with a dose-dense strategy of administration every 14 days (R-CHOP-14). Both regimens demonstrated identical complete response rates (49% vs. 50%) and no differences in PFS or OS at median duration of 5 years of follow-up.107 Anthracyclines are not mandatory in the initial management of follicular lymphoma, and regimens such as cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone (CVP) with rituximab have significantly improved response, progression, and survival compared with CVP alone.108 Bendamustine is an old chemotherapeutic drug developed in East Germany in the 1940s that has demonstrated impressive activity in FL. Combination therapy with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) demonstrated a median PFS of 55 months compared with 35 months with R-CHOP in a randomized study, with higher rates of complete remissions and less toxicity.109 Given the many effective treatment strategies, no standard approach exists. In the National LymphoCare Study, before the approval of bendamustine, R-CHOP was the most commonly administered regimen in the United States, albeit with some geographic variation.99

Maintenance Therapy in Follicular Lymphoma

Relapse of disease is certain after initial therapy for indolent lymphoma, so effective strategies at maintaining remissions have been explored after initial therapy. Interferon-α was the first agent tried in this setting but has been controversial, with only some studies showing a survival advantage.110 Idiotype vaccines are another maintenance strategy, with much of the initial excitement coming from a small study in which an idiotype vaccine induced durable molecular remissions after first clinical remission.111 A recent randomized trial of idiotype vaccinations administered with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulation factor (GM-CSF) after combination chemotherapy without rituximab in untreated advanced FL demonstrated a significant improvement in disease-free survival (DFS) of 44.2 months versus 30.6 months in patients who received the vaccination compared with those who did not receive vaccine.112 How these immune strategies will be used to treat FL in the rituximab era is unclear.

Because rituximab has limited long-term toxicities, it has been an attractive agent for maintenance therapy, and this was studied in a randomized study of CVP versus fludarabine/cyclophosphamide (FC) with a second randomization to observation or maintenance rituximab every 6 months for 2 years.113 Three-year PFS was better in the maintenance arm (68% vs. 33%), but no OS benefit was demonstrated. The effect of rituximab maintenance after initial rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens was addressed in the randomized, phase III PRIMA study.114 In this study, 1217 patients with untreated FL were randomized to 2 years of maintenance rituximab on a schedule of one dose of 375 mg/m2 every 2 months for 2 years versus no maintenance after initial chemotherapy with rituximab. Choice of initial chemotherapy regimen was not mandated, but most patients were given four cycles of R-CHOP. With a median follow-up of 36 months, the subjects in the maintenance arm of the study demonstrated a significant improvement in PFS of 75% versus 58% but no improvement was seen in OS.114 Infections were observed in 39% of patients on maintenance therapy, compared with 24% in the subjects in the observation arm of the study. Until long-term data demonstrate a benefit in OS, this cannot be recommended to all patients, but it is a promising method of prolonging response duration in many patients with indolent lymphomas.

A treatment strategy that has impressive results in phase II studies is the anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugates such as 131I-tositumomab and ibritumomab tiuxetan. These agents, collectively known as radioimmunotherapy (RIT), have demonstrated extremely high complete response rates in untreated FL, with one study of 76 patients demonstrating 75% complete remissions.115 RIT also demonstrates promise as a consolidation strategy in patients who achieve a partial response or better after initial chemotherapy. In a randomized study of ibritumomab tiuxetan after chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone, the PFS was 2 years longer in the ibritumomab tiuxetan arm versus chemotherapy alone.116 A randomized study by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) compared R-CHOP with CHOP followed by ibritumomab tiuxetan in untreated FL and demonstrated no difference in PFS, OS, or toxicity.117 Concerns linger regarding the long-term risks of treatment-related complications such as myelodysplasia or acute myelogenous leukemia, and long-term safety data are lacking.

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) is treated like other indolent B-cell lymphomas. When these lymphomas have a significant IgM paraprotein, they are known as Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), which has a clinical picture that may be dominated by symptoms of hyperviscosity (e.g., dizziness, tiredness, and a propensity for bleeding from the mucous membranes) and symptoms of cryoglobulinemia and cold agglutinin anemia.118 In addition, some patients have peripheral neuropathy, renal disease, and amyloidosis. Patients with acute hyperviscosity symptoms require emergency plasmapheresis with frequent rapid resolution of symptoms.119 Alkylating agents, purine analogs, and rituximab monotherapy have all been used effectively in this disorder,119 but the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, in combination with rituximab and dexamethasone (BDR) has demonstrated impressive results with more rapid responses than with chemotherapy.120 An important cautionary note is the paradoxical rise in IgM levels that is associated with rituximab treatment.121 Patients with signs of hyperviscosity should undergo plasmapheresis before initiating treatment with rituximab-containing regimens or when using rituximab as a single agent.122

Marginal Zone Lymphomas

The treatment principles applied to FL do not apply to all indolent lymphomas. Some lymphomas such as extranodal MALT lymphomas have special treatment requirements. Maltomas are mucosa-associated lymphoid tumors that occur at multiple anatomic sites but predominantly involve the gastrointestinal tract (especially the stomach), the lungs, and the salivary glands. They are frequently antigen driven. Localized gastric MALT lymphoma is unique because of its association with Helicobacter pylori. In many cases, the MALT clone is indirectly dependent on H. pylori and resolves with appropriate antibiotic treatment. Approximately 70% of the cases of stage IE-gastric MALT regress after eradication of H. pylori with antibiotics.123 However, the presence of t(11;18) in the tumor cells predicts a poor response to antibiotic therapy.124 Patients with localized disease and persistent lymphoma despite antibiotics can be effectively treated with rituximab, chemotherapy such as fludarabine,125 and/or radiation therapy,126 depending on the clinical circumstances. Rituximab is particularly active in gastric MALT lymphomas, with overall responses in 64% and complete responses in 29% of patients.127

Nodal marginal zone lymphomas (NMZL) are an extremely rare subtype of lymphoma and a disease mainly of older women. The relationship with MALT lymphomas is complex, and they may occur in the context of a MALT lymphoma (e.g., lymph node involvement secondary to a gastric or parotid MALT lymphoma) with an immunophenotype that is characteristically indistinguishable. NMZLs occur in the absence of extranodal disease and are often more aggressive than MALT lymphoma.128 There is little consensus about treatment, and management is dictated by the site that is involved and the age of the patient. In general, however, the principles of therapy that were described for FL are usually applied to NMZL.

Splenic B-cell marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) represents another special lymphoma that presents as splenomegaly and B cells with villous projections that can often be detected in the peripheral blood. Lymph nodes near the splenic hilum and bone marrow are often involved in these cases. SMZL is rare but represents most cases of chronic lymphoid leukemias that are CD5 negative as well as a large percentage of cases that present as splenomegaly as the dominant clinical feature.129 SMZL is associated with disruptions in the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway in up to one third of patients.130 In patients with chronic hepatitis C, treatment of the infection with interferon-α alone or in combination with the antiviral agent ribavirin is associated with regression of disease in most patients.16 Many patients can be monitored without treatment for many years and should not be treated in the absence of symptoms.131 Historically, splenectomy was often required to establish the diagnosis and prolonged responses are often observed, but rituximab is highly effective and should be considered before splenectomy.132

Relapsed Therapy for Indolent Lymphomas of B-Cell Origin

Relapsed indolent lymphomas can often be re-treated with the same regimen used for initial treatment. Multiple active regimens exist for patients with relapsed disease, with none clearly superior. Fludarabine can be safely combined with other agents and rituximab to achieve high responses. In a randomized phase III trial of 147 patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade lymphoma, patients were treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (FCM) versus FCM with rituximab (R-FCM). Both overall and complete response rates favored R-FCM and were 79% versus 58% and 33% versus 13%, respectively.133 More recently, bendamustine-rituximab (BR) demonstrated a superior overall response rate, 83.5% versus 52.5%, and PFS, 30 versus 11 months, when compared with fludarabine-rituximab in 219 patients with relapsed FL in a multicenter, randomized phase III study.134 Agents with novel mechanisms, such as bortezomib, have also demonstrated good activity in relapsed FL with tolerability that exceeded most chemotherapy agents.135–138 Early activity of these agents led to the investigation of a novel combination therapy of bendamustine, bortezomib, and rituximab (BBR) in patients with relapsed indolent lymphomas.139,140 In the first study, 29 evaluable patients were treated with BBR and 83% achieved an overall response rate with a complete response rate over 50% and a 2-year PFS of 47%.139 A second study gave a similar dosing regimen to 73 patients and found an overall response rate of 88% with a complete response rate of 53% and a median PFS of almost 15 months.140

RIT is highly active in relapsed indolent lymphomas and is indicated for this purpose. In one study, 131I-tositumomab was administered to 40 patients with low-grade or transformed lymphoma and showed a response rate of 65%, with particularly good responses in low grade FL cases with tumors less than 7 cm.141 Ibritumomab tiuxetan was assessed in rituximab failures as defined by no response or progression within 6 months.142 Among 57 patients with FL, overall and complete responses were observed in 74% and 15% of patients, respectively, and the median PFS was 6.8 months. The role of RIT is currently limited to use in patients who have experienced relapse and who have limited bone marrow involvement, but it is under investigation with chemotherapy for initial treatment.117

Multiple studies have demonstrated the feasibility of high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) in patients with relapsed and transformed indolent lymphomas.145–145 Although patients who undergo HD-ASCT early in their disease course have the best outcome, relapses are almost universal. Once transformation occurs, prognosis is generally poor, with median survivals of 6 to 18 months. Long-term risks of this approach such as secondary malignancies are of concern for an approach that has not demonstrated to be curative.146 Overall, these results indicate that autologous transplantation is feasible and active in indolent lymphomas but has a diminishing role in the era of rituximab and novel agents.

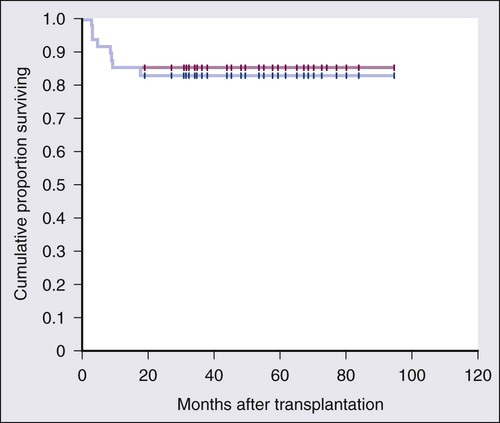

Several groups have investigated allogeneic transplantation in the hope that graft-versus-lymphoma effect may eradicate residual disease. In an effort to avoid the historical 40% treatment-related mortality (TRM) associated with myeloablative conditioning regimens, investigators have developed reduce intensity conditioning stem cell transplants. Khouri and coworkers reported 8-year results of the conditioning regimen using fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in 47 patients with relapsed and refractory FL.147 With a median of 60 months of follow-up, the PFS was 83% with the incidence of grade 2 or more graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) only 11% (Fig. 106-5). More recently, the same group tested the addition of ibritumomab tiuxetan to the FCR conditioning backbone in patients with both chemosensitive and chemorefractory disease and demonstrated 3-year PFS rates of 87% and 80% in those patients, respectively.148 Larger clinical trials with longer follow-up and randomized study designs are needed to establish the role of allogeneic transplantation in the treatment of relapsed indolent lymphomas.

Aggressive Lymphomas of B-Cell Origin

Precursor B-lymphoblastic and T-lymphoblastic lymphomas are highly aggressive diseases with primarily nodal presentations but are biologically identical to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). These entities are extensively discussed in Chapter 98.

Burkitt Lymphoma

BL is an uncommon aggressive B-cell lymphoma composed of rapidly proliferating B cells; it is considered the most highly aggressive NHL, with doubling times of 24 to 48 hours in some cases.149 It was the first tumor to be associated with a virus, one of the first to demonstrate a translocation that activates an oncogene, and the first lymphoma associated with HIV infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).149 Morphologically, BL is composed of small noncleaved cells arranged in a monotonous pattern with a “starry sky” appearance, and nearly 100% of cells are actively proliferating by Ki-67. Biologically, BL is derived from a mature post–germinal center B cell as indicated by its CD20+, CD10+, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)− immunohistochemical profile and gene expression profiling.47,48 BL mostly occurs in the first 2 decades of life, and cases are often subdivided into endemic, sporadic, and those associated with underlying HIV/AIDS. Endemic BL typically manifests as jaw and facial bone disease, and is it virtually always associated with EBV. Sporadic BL usually presents as ileocecal disease and is associated with EBV in 30% to 50% of cases. Immunodeficiency-associated BL usually occurs in HIV-positive populations, associated with nodal disease, and is variably associated with EBV. Patients with disease involving the CNS or bone marrow have a worse prognosis than patients with limited-stage disease.

BL is characterized by a translocation between MYC on chromosome 8 and one of the three immunoglobulin chain loci. These translocations occur with a respective frequency of 80%, 15%, and 5% on chromosomes 14, 22 and 2, which encode in turn for the immunoglobulin heavy chain and λ and κ light chains.149 Because these translocations bring the MYC oncogene into close approximation with the immunoglobulin gene inducible promoter, there is abnormal overexpression of the functionally intact MYC protein. The quantitative overexpression of MYC has been shown to result in deregulation of cellular growth and is capable of blocking phenotypic maturation. Hence, MYC overexpression appears to be central to the pathogenesis of BL.

BL tumor cells have the potential to spontaneously lyse even before the administration of combination chemotherapy, resulting in tumor lysis syndrome. Before the administration of chemotherapy, aggressive use of intravenous hydration and allopurinol reduces this risk by increasing the excretion of uric acid but does not directly address the serum uric acid levels already formed. Rasburicase is a recombinant version of a urate oxidase enzyme that rapidly reduces the preformed uric acid in the serum and can prevent or treat clinical signs of tumor lysis syndrome. Guidelines are available that address situations in which the use of rasburicase should be considered.150

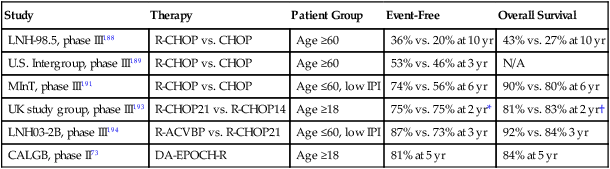

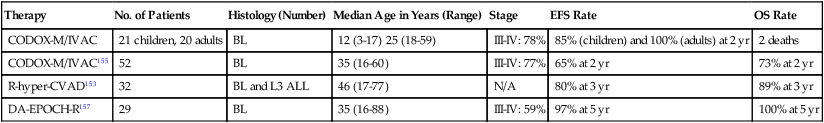

BL requires chemotherapy for all disease stages, but R-CHOP is inadequate. Several biological characteristics of BL have helped guide treatment strategies, including its high proliferative fraction. The high tumor proliferation rate led to the use of dose-intense regimens with a short cycle time to theoretically minimize tumor regrowth between cycles.151–156 Multiple drugs, typically administered in alternating combinations, are used, and the high rate of spread to the CNS has led to the standard use of CNS prophylaxis. Such high-intensity brief-duration regimens have been associated with very high rates of initial response and long-term DFS in most patients (Table 106-7). Toxicity is an important clinical limitation of these regimens in adults, particularly in older patients in whom severe morbidity occurs. Therefore, one of the major therapeutic challenges in BL is to develop therapies that are as effective in achieving high cure rates as “standard” regimens but that improve the therapeutic index and reduce toxicity complications. Preliminary results in a pilot study of dose-adjusted rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine, and prednisone (DA-EPOCH-R) in 29 patients with BL showed an EFS and OS of 97% and 100%, respectively, at a median follow-up of 57 months, with low toxicity compared with conventional regimens.157

Table 106-7

Treatment Outcome in Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

| Study | Therapy | Patient Group | Event-Free | Overall Survival |

| LNH-98.5, phase III188 | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | Age ≥60 | 36% vs. 20% at 10 yr | 43% vs. 27% at 10 yr |

| U.S. Intergroup, phase III189 | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | Age ≥60 | 53% vs. 46% at 3 yr | N/A |

| MInT, phase III191 | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | Age ≤60, low IPI | 74% vs. 56% at 6 yr | 90% vs. 80% at 6 yr |

| UK study group, phase III193 | R-CHOP21 vs. R-CHOP14 | Age ≥18 | 75% vs. 75% at 2 yr* | 81% vs. 83% at 2 yr† |

| LNH03-2B, phase III194 | R-ACVBP vs. R-CHOP21 | Age ≤60, low IPI | 87% vs. 73% at 3 yr | 92% vs. 84% 3 yr |

| CALGB, phase II73 | DA-EPOCH-R | Age ≥18 | 81% at 5 yr | 84% at 5 yr |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

DLBCL is the most common lymphoid neoplasm in adults, representing 30% to 40% of cases diagnosed. It is a disease of older adults, with a median presentation in the seventh decade, but it occurs at any age. Patients have localized or disseminated disease with nodal or extranodal involvement. Within DLBCL, there are several morphologic variants, including centroblastic, immunoblastic, T-cell rich/histiocyte rich, and anaplastic subtypes; and molecular profiling has further advanced this taxonomy.71 There are also several clinicopathological variants of DLBCL, such as primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL); intravascular large B-cell lymphoma; primary DLBCL of the CNS (PCNSL); primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type; EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly; DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation; ALK+ large B-cell lymphoma; plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL); primary effusion lymphoma (PEL); and large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV-8–associated multicentric Castleman disease (see Table 106-3). These entities are considered distinct subtypes of DLBCL based on a combination of clinical, histologic, and molecular findings.

Pathogenesis

Genome-wide molecular profiling has revealed three subtypes of DLBCL that differ in genetic makeup but are indistinguishable on morphologic grounds alone: the activated B-cell (ABC) subtype, the germinal center (GCB) subtype, and the primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) subtype.42,70,71 Tremendous genetic heterogeneity exists within and among the different subtypes of DLBCL: each is defined by unique molecular alterations that determine prognosis and response to initial therapy,73 different responses to salvage therapy with targeted agents,74 and differences in overall cure rates.38

The GCB subtype of DLBCL typically expresses genes normally found in the germinal center of normal B cells such as CD10 and LMO2.70,71 A common molecular abnormality is the deregulation of BCL-6, which is the key transcriptional regulator of the germinal center reaction.158 BCL-6 protein functions as a transcription factor that binds a specific DNA sequence and represses the transcription of genes involved in critical biological processes, such as cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response, and apoptosis.159,160 It is important in the normal functioning of the germinal center B cells and is required for germinal center cell formation during the antigen-driven immune response.161 Thus, DLBCLs with high expression of BCL-6 on immunohistochemistry are usually of GCB origin, and, in part, this may help distinguish them from other DLBCL subtypes.162 Another abnormality found in GCB subtype DBLCL that is not found in ABC-type DLBCL is deletions in the tumor suppressor PTEN found in as many as 15% of cases, which leads to constitutive activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathway.38

ABC-type DLBCL characteristically expresses genes that are normally found in plasma cells.70 The differentiation into plasma cells is blocked by BLIMP1, the master regulator controlling plasmacytic differentiation. BLIMP1 is inactivated in over half of cases of ABC-type DLBCL through multiple mechanisms, confirming it as a true tumor suppressor gene.163 The pathogenic hallmark of ABC-type DLBCL, however, is the constitutive activation of the NF-κB pathway, which promotes cell proliferation and protection from apoptosis.32 The NF-κB family of proteins is a group of five transcription factors (RelA, RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1, and NF-κB2) that are typically kept inactive by inhibitory cytoplasmic proteins.164 Three proteins, CARD11, BCL10, and MALT1, form a signaling complex (CBM), which leads to the activation of NF-κB after antigen stimulation.165 CARD11 mutations can be found in up to 10% of cases of ABC-type DLBCL but are not seen in GCB-type.166 An alternative mechanism of NF-κB activation is the deletion of the negative regular A20, which is found in as many as 30% of cases of ABC-type DLBCL.167 Most recently, another mechanism of NF-κB activation was found in the form of MYD88 mutations, which can be found in 30% of cases of ABC-type DLBCL.33 A newly discovered pathogenic mechanism important for ABC-type DLBCL is a form of chronic B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling that can be found in the subsets without CARD11 mutations. Somatic mutations were discovered in immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) signaling molecules such as CD79B in 18% of cases of ABC-type DLBCL.168 By nature of their relationship to surface BCR expression, this finding suggests multiple potential therapeutic targets for this subtype of DLBCL.

Another common finding in DLBCL is overexpression of the major anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2, originally reported to be present in 24% to 55% of cases.169,170 Interestingly, only 14% to 17% of these cases were found to harbor a BCL-2 gene rearrangement, suggesting the presence of variable molecular mechanisms of BCL-2 overexpression. BCL-2 overexpression is the result of t(14;18) translocation exclusively in the GCB subtype,171 whereas the mechanism of BCL-2 overexpression in ABC subtype is the result of NF-κB activation.172 Overexpression of the BCL-2 protein (but not the BCL-2 gene rearrangement) was originally found to be associated with decreased survival in the ABC subtype in the pre-rituximab era,172 but more recent studies demonstrate that overexpression of the BCL-2 protein portends poor prognosis only in the GCB subtype in the setting of R-CHOP regimens.173 Other variable molecular findings in DLBCL include mutation of the p53 gene, found in approximately 20% of cases at initial diagnosis; this has also been associated with decreased survival and drug resistance, presumably through its anti-apoptotic effects.174,175

Initial Treatment of Localized DLBCL

Radiation treatment alone is inadequate for treatment of localized DLBCL because the disease does not spread to contiguous nodes and commonly has disseminated tumor cells.176 Whether radiation treatment adds to rituximab-containing regimens is controversial. In the pre-rituximab era, combined modality therapy became the standard based on a randomized study that showed a survival advantage of limited-course CHOP plus involved field radiation compared with full-course CHOP in early-stage (I/II) aggressive lymphoma.177 However, longer patient follow-up times showed a convergence of the OS curves because of late systemic relapses in the combined modality arm. One prospective study randomized 576 elderly patients with favorable early-stage aggressive lymphoma to receive CHOP alone (four cycles) or CHOP plus irradiation and found that combined modality therapy was not superior to chemotherapy alone.178 More recently, rituximab has been combined with CHOP and involved-field radiation (IFRT) in limited-stage aggressive NHL and found to have a 2-year PFS of more than 80%.179 This strategy has not been compared with rituximab (R-CHOP) without irradiation, however; and given the long-term risks of radiation, it is difficult to justify the routine use of radiation to nonbulky sites in early-stage disease.

Initial Treatment of Advanced DLBCL

Anthracyclines have established themselves as the single most important drug class in the treatment of aggressive lymphomas, but a number of effective regimens exist (Table 106-8). Since it was first recognized in the 1970s that DLBCL could be cured with combination chemotherapy, the search for a perfect regimen has been ongoing.180 The CHOP regimen is a first-generation regimen that became the standard after being studied extensively in national cooperative settings. In the 1980s, single-institution phase II studies of dose-intensive regimens reported impressive response rates compared with historical response rates seen with CHOP therapy. However, a landmark study in 1993 reestablished CHOP therapy as the backbone by which all challengers are to be compared in a randomized trial in which it was shown to be equally effective and less toxic.181 The fact that only 44% of patients achieved complete remissions with CHOP, however, left significant room for improvement and spawned multiple studies aimed at improving treatment outcome. Many of these studies have focused on modifications to the CHOP platform.

Table 106-8

Selected Regimens for Burkitt Lymphoma

| Therapy | No. of Patients | Histology (Number) | Median Age in Years (Range) | Stage | EFS Rate | OS Rate |

| CODOX-M/IVAC | 21 children, 20 adults | BL | 12 (3-17) 25 (18-59) | III-IV: 78% | 85% (children) and 100% (adults) at 2 yr | 2 deaths |

| CODOX-M/IVAC155 | 52 | BL | 35 (16-60) | III-IV: 77% | 65% at 2 yr | 73% at 2 yr |

| R-hyper-CVAD153 | 32 | BL and L3 ALL | 46 (17-77) | N/A | 80% at 3 yr | 89% at 3 yr |

| DA-EPOCH-R157 | 29 | BL | 35 (16-88) | III-IV: 59% | 97% at 5 yr | 100% at 5 yr |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; EFS, event-free survival; N/A, not available; OS, overall survival.

High tumor proliferation determined by Ki-67 or MIB-1 immunohistochemistry has been shown to be an adverse prognostic finding with CHOP chemotherapy, suggesting “kinetic failure” is a problem.182 One strategy to overcome kinetic failure is to increase dose density through frequent chemotherapy administration. The Deutsche Studiengruppe für Hochmaligne Non-Hodgkin Lymphome (DSHNHL) group evaluated the effect of dose density and etoposide in two four-arm studies of CHOP administered every 14 or 21 days, with or without etoposide (CHOEP), in patients older than age 60 years and low-risk patients 60 years and younger.183,184 In younger patients, CHOEP-21 showed the best overall results, with a complete response rate of 88% versus 79% and an EFS of 69% versus 58% at 5 years compared with standard CHOP-21, respectively.184 In older patients, however, dose-dense CHOP-14 showed the best outcome with a complete response rate of 76% versus 60% and EFS of 44% versus 33% at 5 years compared with standard CHOP-21.183

An alternative strategy to dose density is to increase the fractional cell kill, thereby reducing the number of tumor cells that can survive and proliferate between cycles. Longer drug exposure may take advantage of the increased sensitivity of cycling cells, and in vitro studies have shown that prolonged low concentration exposure to vincristine and doxorubicin, compared with brief higher concentration exposure, can increase cytotoxicity by as much as 1 log.185 This approach was translated into the pharmacodynamically derived DA-EPOCH regimen, which showed a promising PFS and OS of 70% and 73%, respectively, at 5 years median follow-up in newly diagnosed DLBCL.186 Interestingly, high tumor proliferation was not found to be an adverse biomarker in this study.

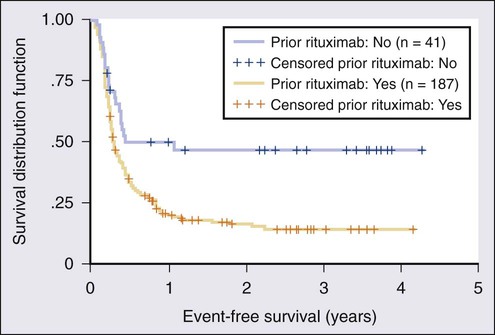

It has been the development of rituximab, however, that has made the single greatest impact on the treatment of DLBCL since CHOP was first introduced almost 40 years ago. The first study to demonstrate the benefit of rituximab was a Groupe d’Études des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) study, in which patients older than 60 years were randomized to receive CHOP or CHOP with rituximab (R-CHOP).187 In this study, the complete response rate (76% vs. 63%) and 5-year EFS (47% vs. 29%) were higher with R-CHOP than CHOP, respectively, making R-CHOP the “de-facto” standard in DLBCL.187 Long-term follow-up of this study demonstrated a 10-year PFS of 36.5% with R-CHOP compared with 20% with CHOP alone with no late relapses or increased risk of secondary malignancies (Fig. 106-6).188 In a similar patient population, this finding was validated in a U.S. Intergroup Study that additionally demonstrated the lack of benefit to maintenance rituximab.189 The MabThera International Trial (MInT) studied the benefit of rituximab with CHOP-based treatment in younger patients (≤60 years) with favorable characteristics defined as low IPI risk.190 Patients who received rituximab fared significantly better, with a 3-year EFS of 79%. As an interesting aside, the MInT study also showed that rituximab obviated the benefit of CHOEP in younger patients. Long-term results of the MInT study demonstrate a 6-year EFS still favoring the rituximab arm of the study, with 74% versus 56% without an increase in secondary malignancies despite the use of radiation therapy in nearly half of patients.191 The DSHNHL group also explored the question of whether there was a difference in outcome between six or eight cycles of treatment in a randomized study of six versus eight cycles of CHOP-14, with or without rituximab, in more than 1200 elderly patients with DLBCL. In that study, named the RICOVER-60 trial, the researchers found no difference in outcome with six versus eight cycles of treatment.192 Although there was an excellent 3-year EFS of 66% with R-CHOP-14 over six cycles, the superiority of R-CHOP-14 to standard R-CHOP-21 was not proven. A randomized comparison done in the United Kingdom of R-CHOP-14 did not demonstrate an advantage over R-CHOP-21 with respect to PFS or OS.193

The GELA group reported outcomes with their ACVBP (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone) regimen used with rituximab (R-ACVBP) versus R-CHOP-21 for eight cycles in patients younger than 60 years old with low-risk IPI aggressive lymphomas. In this regimen, aggressive therapy for CNS disease, including both intrathecal and high-dose methotrexate, was used for a treatment duration of 30 weeks.194 The R-ACVBP regimen demonstrated a 3-year PFS advantage over R-CHOP of 87% versus 73% but was associated with significant hematologic toxicity and is unlikely to be tolerated by patients older than the age of 60 years. Additionally, the need for intensive CNS prophylaxis in all patients with DLBCL, particularly those with low IPI, is unproven and likely results to result in overtreatment of many patients.

Rituximab has also been tested in combination with the DA-EPOCH regimen. In a single-institution study of 72 patients, 80% and 79% of patients were progression free and alive, respectively, at the median follow-up of 5 years.195 Furthermore, 93% and 71% of patients in the low- and high-risk IPI groups, respectively, had not progressed. More recently, these findings were confirmed in a multicenter Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) cooperative group study of 69 patients with untreated DLBCL.73 At a median follow-up of 62 months, the time to progression (TTP) and OS of the entire group were 81% and 88%, respectively.73 Important differences were seen with respect to cell-of-origin phenotype, and the TTP and EFS in the GCB-like DLBCL cohort were 100% and 94%, respectively, whereas the TTP and EFS in the ABC-like DLBCL cohort were only 67% and 58%, respectively, at 62 months. A randomized, multicenter evaluation of DA-EPOCH-R versus R-CHOP in untreated DLBCL is ongoing in the CALGB cooperative group in conjunction with microarray analysis.

The role of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) in the initial treatment of DLBCL remains controversial. Although some studies have suggested benefit, they were performed in the pre-rituximab era.196 ASCT is also associated with late-stage toxicities, including leukemia and secondary myelodysplasia, which must be considered in the risk-benefit analysis of treatment.197

Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) represents a distinct clinicopathological variant of DLBCL with a readily distinguishable molecular profile and a favorable outcome with modern therapy.41,42 PMBL usually occurs in young women, remains localized to the mediastinum, and frequently invades adjacent structures. Involvement of extrathoracic nodal regions and the bone marrow is very uncommon, making the Ann Arbor staging system irrelevant in this disease. Clinically, the features seen in PMBL resemble those observed with NSHL.45

In fact, it is now appreciated that the genetic and epigenetic makeup of PMBL shares more similarities with NSHL than other cases of de novo DLBCL.198,199 The genetic hallmark of PMBL is amplification of a region on chromosome 9p24 that encodes for Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), which can also be found in Hodgkin lymphoma but rarely in other DLBCLs.200,201 PMBL and NSHL both arise from a thymic B cell, but PMBL arises from a mature B cell and NSHL does not.32 Overexpression of NFKB target genes and amplification of the REL locus are also frequently observed in PMBL and are likely important in pathogenesis.164 These tumors, therefore, have many overlapping features and are bridged by MGZLs on a biological continuum between these two entities.45

In the pre-rituximab era, patients with PMBL appeared to benefit from the use of dose-intense regimens, such as methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin (MACOP-B) and etoposide with leucovorin rescue, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin (VACOP-B), as well as 30 to 40 Gy of consolidative radiation therapy to the mediastinum.202,203 Thus, a precedent was set of six to eight cycles of R-CHOP followed by mediastinal irradiation, but the need for radiation therapy has not been validated in the rituximab era. Late complications of mediastinal irradiation in young women include an increased risk of second malignancies, particularly breast cancer, and the early onset of cardiovascular disease. Two groups have recently reported data on rituximab-based chemotherapy programs that largely omit consolidative irradiation. In a phase II study from the National Cancer Institute of 40 patients with PMBL uniformly treated with six cycles of DA-EPOCH-R, 100% and 95% are alive and event free at a median 47 months of follow-up, respectively; only two patients required radiation treatment, and no patient experienced relapse.204 Moskowitz and associates reported data on 54 patients treated with sequential dose-dense R-CHOP every 14 days for four cycles followed by three cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) without the use of mediastinal irradiation.205 Eighty-eight percent and 78% are alive and progression free at 3 years of follow-up, respectively. Taken together, these data suggest that when rituximab is added to dose-intense regimens, it may obviate the need for irradiation in most patients with PMBL.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

MCL is an uncommon but distinct form of NHL derived from naïve small B lymphocytes. The median age of patients of newly diagnosed patients is older than 65 years and there is a male predominance.206 The genetic hallmark of MCL is the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation in which the coding region of cyclin D1 on chromosome 11 is juxtaposed to the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene on chromosome 14.207 MCL has a remarkable tendency to disseminate, and almost all patients have advanced disease at presentation. It frequently involves extranodal sites such as the gastrointestinal tract (even with normal-appearing mucosa), bone marrow, and the CNS.208 A leukemic component can be found in 20% to 30% of patients, often in association with splenomegaly out of proportion to adenopathy.

Pathogenesis

The complex pathogenesis of MCL is characterized by simultaneous disruption of cell cycle regulation and DNA damage response pathways.209,210 The t(11;14) translocation leads to the constitutive overexpression of cyclin D1 in lymphoid cells where normally only cyclin D2 and D3 are expressed. Cyclin D1 complexes with cyclin-dependent kinases such as CDK4 and CDK6 resulting in hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene RB1.209 RB1 arrests cells in G1 by inhibiting the activity of E2F transcription factors but also serves to regulate apoptotic death and preserves chromosomal stability.209 Overexpression of cyclin D1 therefore leads to irreversible progression of the cell through the G1 to S phase transition and is considered the inciting oncogenic event in MCL. In addition to the “gain of function” attributes that lead to rapid cellular proliferation owing to the overexpression of cyclin D1, tumors also exhibit “loss of function” attributes such as the depletion of cell-cycle–dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p27 (a.k.a., KIP1) as well as defective apoptosis.207,209 These additional genetic events are needed for MCL to develop, as evidenced by the fact that transgenic mice overexpressing cyclin D1 do not develop lymphoma.211