Chapter 55B Management of chronic pancreatitis

Conservative, endoscopic, and surgical

Overview

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive, destructive, inflammatory process that ends in total destruction of the pancreas and results in malabsorption, diabetes mellitus, and severe pain. Incidence and prevalence of CP varies between continents and countries. Most studies from Western countries show comparable incidence and prevalence rates of around 7 per 100,000 and 28 per 100,000, respectively (Lankisch et al, 2002; Levy et al, 2006). The numbers reported from Asia are markedly higher with a rapidly rising incidence (Otsuki & Tashiro, 2007; Wang et al, 2009). The etiologic factors associated with CP are commonly summarized using the TIGAR-O classification: toxic–metabolic (in the West, alcohol and tobacco are associated in approximately 80% to 90% of cases), idiopathic, genetic (PRSS1, CFTR, or SPINK1 gene mutations), autoimmune, recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis, or obstructive (pancreas divisum, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, or neoplasm) (Etemad & Whitcomb, 2001). Tropical CP is a common entity in India, southern Africa, and parts of South America and typically affects younger patients. Tropical CP is often classified as idiopathic but may in fact have a mixed etiology that includes nutritional, metabolic, and genetic factors (Mohan et al, 2003). Current evidence suggests that a combination of predisposing factors—environmental, toxic, and genetic—is likely involved in most cases rather than a single factor. The sentinel acute pancreatitis event (SAPE) hypothesis proposes a sentinel event of acute pancreatitis that initiates the inflammatory process, which is then sustained by a combination of the mechanisms mentioned above (Whitcomb, 1999).

Repeated episodes of inflammation initiated by autodigestion, oxidative stress, one or more episodes of severe pancreatitis, and toxic-metabolic factors can lead to activation and continued stimulation of pancreatic stellate cells. Histologically, CP is characterized by inflammatory infiltration, acinar atrophy, formation of metaplastic ductal lesions (tubular complexes and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia), extended fibrosis, and in some cases by focal necrosis and cysts (Klöppel, 2007). Furthermore, neural hypertrophy and perineural inflammation can frequently be observed and are the correlate of neuropathic pain (Ceyhan et al, 2009a).

In the natural course of CP, endocrine and exocrine insufficiency frequently develops secondary to the fibrotic changes of the pancreas. As a result of morphologic changes of the pancreas, patients frequently develop local complications. Inflammatory ductal changes and intraductal calculi (pancreatolithiasis) may result in obstruction of the pancreatic duct or of the intrapancreatic portion of the bile duct. An inflammatory mass of the pancreatic head, as it is regularly observed in European and American series (Beger et al, 1999; Jimenez et al, 2000), frequently results in obstruction of the duodenum and affects the splenic, superior mesenteric, or portal vein with subsequent thrombosis. Development of pancreatic pseudocysts represents another local complication, which results in obstruction, abscess formation, or in ascites or pleural effusions in cases of rupture (see Chapter 54). A rare but severe local complication of CP is vascular erosion presenting as gastrointestinal hemorrhage or, less frequently, as intraabdominal bleeding (see Chapter 19). Finally, CP is a risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer (see Chapter 58A, Chapter 58B ); patients with CP have a fourfold higher risk of cancer than individuals without it. Especially in the management of patients with an “inflammatory mass,” this differential diagnosis has to be considered (Pedrazzoli et al, 2008).

Conservative Treatment

Pancreatic Exocrine Dysfunction

In Western countries, the number of patients suffering from pancreatic exocrine insufficiency has increased. The most common cause is an increase in alcohol consumption with a concomitant increase of CP (FitzSimmons, 1993). The main goal of therapy for pancreatic exocrine dysfunction is to avoid fat maldigestion. Reasons for earlier and more severe impairment of fat digestion, compared with protein and carbohydrate digestion, in patients with pancreatic insufficiency are that 1) impairment of pancreatic lipase synthesis and secretion occurs earlier; 2) more rapid and complete inactivation of lipase occurs in the acidic duodenum as a result of impaired bicarbonate output; 3) proteolytic degradation of lipase occurs earlier during aboral transit than with amylase and proteases; 4) impairment of pancreatic bicarbonate secretion decreases duodenal pH, resulting in precipitation of glycine-conjugated bile acids and further deterioration of fat digestion; and 5) extrapancreatic sources of lipase are unable to compensate for loss of pancreatic lipase activity.

Pancreatic Exocrine Enzyme Supplementation

When weight loss or steatorrhea (≥15 g/day) or both develop, supplementation of pancreatic enzymes is indicated. Dyspepsia, diarrhea, meteorism, and malabsorption of proteins and carbohydrates also have been cited as indications. Another interesting indication for pancreatic enzyme supplementation, although not formally studied, is in the treatment of pain (discussed in the next section). The main goal of the treatment of pancreatic exocrine dysfunction is to ensure that optimal amounts of lipase reach the duodenum with the delivered food. With the currently available pancreatic enzyme supplement preparations, azotorrhea (protein malabsorption) can be eliminated (Brady et al, 1991), whereas steatorrhea usually can be reduced but not totally corrected.

Four different types of pancreatic exocrine enzyme preparations are available. Uncoated preparations show only poor effects because of their inactivation by gastric acid. Huge doses of enzymes are required to have any effect on fat malabsorption. These preparations should be used only in patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria. The use of enteric-coated tablets is strongly discouraged, because these preparations are ineffective for decreasing fat excretion owing to erratic enzyme release. The superiority of enteric-coated microsphere preparations over conventional enzyme preparations with regard to decrease in stool fat excretion has been firmly established (Layer & Holtmann, 1994). Pancreatic enzymes in these preparations are protected at low pH by a special polymer coating. The release of the enzymes occurs only at a pH of at least 4.5. Simultaneous administration of antacids, H2-receptor antagonists, or proton pump inhibitors is unnecessary. Unfortunately, microencapsulation results in a considerable increase in costs. Another problem concerning enteric-coated microspheres might be considerable differences in the diameter of the microspheres and in their physical nature as a result of differences in the manufacturing process; however, clinical differences in the various enteric-coated microsphere preparations have not yet been proofed.

The use of enzyme preparations in combination with acid-reducing compounds also is not justified for many reasons, although additional administration of proton pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists reduces fecal nutrient loss. These preparations are expensive, there is a variability of the effects owing to the acid-reducing therapy, and especially in children, the safety of long-term administration has not been firmly established (Lebenthal et al, 1994).

Certain bacterial and fungal lipases have shown no benefit in the treatment of pancreatic steatorrhea, although they are resistant against acid denaturation and proteolytic digestion. Decreased lipolytic activity of fungal lipase in the presence of bile acids could explain the fact that no superiority over enteric-coated microsphere preparations has been demonstrated to date (Griffin et al, 1989; Zentler-Munro et al, 1992).

Although rare, possible side effects of pancreatic exocrine enzyme supplementation are sourness of the mouth, perianal irritation, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation in infants, allergic reactions to pork proteins, hypersensitivity reactions after inhalation, and fibrosing colonopathy in cystic fibrosis patients (Lebenthal et al, 1994; Loser & Folsch, 1995). In regard to fibrosing colonopathy, it has been recommended that the maximum dose of lipase should not exceed 10,000 IU/kg body weight per day, or 2500 IU/kg body weight per meal.

Substitution Therapy in Chronic Pancreatitis

Approximately 80% of patients with CP can be managed by dietary means and pancreatic enzyme supplements. Some patients (10% to 15%) need oral supplements (polymeric or semielemental), 5% need enteral tube feeding, and approximately 1% need total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Reduction of steatorrhea and supplementation of calories are the main goals of nutritional therapy in CP. Treatment of exocrine insufficiency starts with dietary therapy and pancreatic enzyme supplementation (DiMagno, 1979).

Total abstinence from alcohol and partaking of frequent meals are basic dietary recommendations. The diet should be rich in proteins (1.0 to 1.5 g/kg body weight/day) and carbohydrates, although carbohydrates must be limited when diabetes mellitus is present. In addition, 30% to 40% of calories should be in the form of fats. Medium-chain triglycerides may be used to increase fat absorption, because they are absorbed directly across the small bowel into the portal vein, even in absence of lipase, co-lipase, and bile salts. Vitamins should be supplemented if serum levels indicate a deficiency (Havala et al, 1989). Patients with protein maldigestion and steatorrhea must be supplemented individually with exogenous pancreatic enzymes. Weight control, symptomatic relief of diarrhea, and a decrease in 72-hour fecal fat excretion are practical end points of therapy.

Conservative Treatment of Pain

Different medical treatment options and therapeutic interventions are available, and these must be integrated into an individualized treatment plan. The pathogenesis of pain especially influences the therapeutic procedure. Two mechanisms are suggested for the generation of pain in the absence of local complications: 1) inflammatory changes of pancreatic parenchyma with intrapancreatic and peripancreatic neural alterations (Bockman et al, 1988; Ceyhan et al, 2009a, 2009b; Di Sebastiano et al, 1997), and 2) ductal and intraparenchymal hypertension (Di Sebastiano et al, 2003; Ebbehoj et al, 1990).

As for the second mechanism, options that reduce the intrapancreatic pressure may lead to a significant reduction of pancreatic pain. In the case of inflammation, a significant number of inflammatory mediators in pancreatic parenchyma and pancreatic nerves are detected in patients with pain (Ceyhan et al, 2009b; Di Sebastiano et al, 2000). Several medical, analgesic, and antiinflammatory treatment options are available, which may be combined with or supported by interventional methods.

Alcohol Abstinence and Diet

Besides alcohol abstinence, no specific dietary measures have been found to be effective in preventing pancreatic pain. Even total abstinence from alcohol may achieve pain relief in only 50% of patients with moderate to mild CP (Gullo et al, 1988).

Suppression and Inhibition of Pancreatic Secretion

The effect of pancreatic enzyme preparations on pain is uncertain. A meta-analysis of six studies on enzymes for pain treatment concluded that there is no positive effect, but this conclusion is unreliable because of the heterogeneity of the study groups and significant differences in drug preparations (Brown et al, 1997). A more recently published review that also included data from studies published in abstract form came to a similar conclusion (Winstead & Wilcox, 2009). Further studies are needed to prove whether somatostatin and its analogue octreotide have any impact on pain in patients with CP. A proper placebo randomized controlled trial (RCT) must be performed, which should include 1) the classification of patients as to the etiology of their CP, 2) the systematic assessment of quality of life of patients prior to the initiation of therapy and at regular intervals throughout the study, 3) a priori power analysis estimating a placebo response rate of at least 25%, and 4) multiple planned subgroup analysis (Winstead & Wilcox, 2009).

Analgesics

Guidance for analgesic treatment in patients with CP is based on the consensus report of the German Society of Gastroenterology (Mössner et al, 1998) and the recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1990). One physician should be responsible for the administration of analgesics. For the first step in pain management, nonnarcotic agents, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are recommended. Opioids are often necessary further along. Every patient requires an individualized type and dose of analgesic drug, starting with the lowest dose necessary to control pain. In patients with pain mainly caused by inflammation and by invasion of inflammatory cells, antiinflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs may be helpful. Some patients with CP have depression, which lowers the visceral pain threshold. An additional antidepressant therapy may have an effect on pain and generally increases the effects of opiates.

Interventional Procedures to Treat Pancreatic Pain

Of patients with pancreatic pain, 40% to 70% seem to benefit from medical treatment (Ammann et al, 1984). This percentage may increase by combining medical therapy and interventional procedures (van der Hule et al, 1994). Pancreatic pain may also be improved by the combination of interventional endoscopy and lithotripsy, although a recent RCT demonstrated increased costs but no outcome benefit when systematic endoscopy was added to lithotripsy (Dumonceau et al, 2007). Some studies showed a significant difference in improvement of pain among patients with successful or unsuccessful lithotripsy (Delhaye et al, 1992; Costamagna et al, 1997; Johanns et al, 1996; Ohara et al, 1996; Sauerbruch et al, 1992; Schneider et al, 1994; Smits et al, 1996). Other studies did not report this difference (Adamek et al, 1999).

Celiac plexus neurolysis and celiac block involve injecting an agent at the celiac axis, with the aim of either selectively destroying the celiac plexus or temporarily blocking visceral afferent nociceptors. Agents most commonly used for this purpose include alcohol or phenol for neurolysis and bupivacaine and triamcinolone for a temporary block. Methods to administer such agents to the celiac ganglion include CT imaging, percutaneous ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Whereas the EUS-guided technique may be superior compared with the other methods, response rates in general are relatively low (Gress et al, 1999; Noble & Gress, 2006; Santosh et al, 2009).

Autoimmune Pancreatitis

A type of CP that might be caused by an autoimmune mechanism was first described by Sarles and collegues (1961) and was termed primary inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas. Since then, a growing body of evidence suggests that autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is distinct from obstructive or calcifying forms of CP. Two clinical and histologic patterns of AIP can be distinguished (Park et al, 2009). Type 1 is characterized by the histologic key features of dense periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, swirling or storiform fibrosis, and obliterative venulitis; serum levels of the immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) subclass of IgG are typically increased (Hamano et al, 2001). Type 1 AIP fits the classic description of the disease reported in Japan, also known as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Type 1 AIP appears to be the pancreatic manifestation of a systemic disease that may also affect other organs, including the bile duct, retroperitoneum, kidney, lymph nodes, and salivary glands. Type 2 AIP is typically characterized by a duct-destructive pathology with infiltrating neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Typical serologic markers seen in type 1 AIP are not elevated in type 2 AIP (Park et al, 2009). Typical imaging features—a diffuse, sausage-shaped, enlarged pancreas with delayed and peripheral enhancement—only show up in about 50% of patients. Furthermore, classic features of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis are found in just 20% of core biopsies, and false-positive IgG4 immunostaining has also been reported in the setting of cancer. Thus the preoperative differentiation from pancreatic carcinoma is a diagnostic challenge. In highly suspected or histologically confirmed cases of AIP, steroid therapy (prednisolone, initially 30 to 40 mg/day) may ameliorate symptoms and imaging findings within two weeks. Importantly, the similarity to pancreatic carcinoma and the absence of specific diagnostic parameters may result in surgical treatment of this disease. Because reports about patients misdiagnosed as having AIP are increasingly encountered, surgery should always be considered in doubtful cases (Gardner et al, 2009).

Endoscopic Treatment In Chronic Pancreatitis

Pancreatic ductal obstruction by fibrotic stenoses and/or calculi are the most frequent indications for endoscopic therapy. Interventional treatment modalities aim to decompress and drain the pancreatic ductal system. Endoscopic interventions (see Chapters 14 and 27)—such as stone extraction, dilations, and stenting—have to be repeated on a regular basis in almost all patients. As a consequence, patients suffer from frequent rehospitalizations.

Two recent RCTs demonstrated the superiority of surgical versus endoscopic therapy in primary success rate, pain relief, and quality of life in patients with duct obstruction in the pancreatic head (Cahen et al, 2007; Dite et al, 2003). On the other hand, a large multicenter study in 1018 patients reported success of endoscopic therapy (multiple sessions) in 65% of patients, with the necessity for surgery in only 24% (Rösch et al, 2002). A study of 61 patients with CP and bile duct stenosis reported a 1-year success rate of 59% with endoscopic stenting and stent replacement every 3 months, but failure of endoscopic therapy occurred in the majority of cases with presence of calcifications, with a success rate of only 7.7%; moreover, 49% of patients who had an unsuccessful interventional therapy underwent surgery within a year (Kahl et al, 2003). In patients with symptomatic pseudocysts and no ductal obstruction, endoscopic drainage procedures may be as safe and effective as surgical drainage but superior to external drainage, as reported in a recent retrospective study (Johnson et al, 2009). However, this result needs confirmation in a larger-scale randomized trial.

Endoscopic treatment options and their possible indications are summarized in Table 55B.1. Endoscopic therapy for pancreatic pseudocysts and common bile duct stenosis associated with CP is discussed in detail here.

Table 55B.1 Interventional and Endoscopic Therapy: Options and Indications

| Options | Indications |

|---|---|

| Interventional External Drainage | Temporary treatment of a pancreatic abscess or an infected pseudocystFrequently followed by definitive surgical treatmentIf internal drainage is not possible |

| Internal Drainage | Effective therapy of pseudocysts; no RCTs with comparison to surgery |

| Endoscopic cystogastrostomy/cystroduodenostomy | If anatomically possible: less invasive than surgeryProblems with recurrence and catheter dislocation |

| Endoscopic Ductal Drainage | |

| ePT | Pancreas divisum, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction |

| ePT plus dilation + stenting of pancreatic duct | Proximal stenosis of pancreatic duct |

| ePT plus lithotripsy and stone extraction | Pancreatolithiasis |

| ePT plus bile duct stenting | Bile duct stenosis |

| Indicators of Poor Outcome | |

| Distal stenosis of pancreatic duct | |

| Parenchymal calcifications | |

| Unsuccessful management after 1 year |

RCT, Randomized, controlled trial; ePT, endoscopic papillotomy

Decompression of Pancreatic Pseudocysts

Pancreatic pseudocysts are a late complication of CP. The main techniques for decompression of pancreatic pseudocysts include transgastric and transduodenal approaches (Sahel, 1990; Dohmoto & Rupp, 1992); these require a clear bulging of the cyst into the gastric or duodenal cavity to ensure a short distance between the cystic wall and the intestinal tract. In this context, endosonography has been shown to reduce the risk of cyst perforation and hemorrhage (Binmoeller et al, 1994; Etzkorn et al, 1995; Grimm et al, 1992).

The technical success rate appears to be better for cystoduodenostomy than for cystogastrostomy owing to a higher complication rate (Binmoeller et al, 1994; Sahel, 1991). In more recent articles, the mortality appears to be almost zero, whereas morbidity rates are reported between 3% and 11% (Binmoeller et al, 1994; Dohmoto & Rupp, 1992; Etzkorn et al, 1995; Grimm et al, 1992; Sahel, 1990, 1991). A more recent approach to access the cystic cavity is indirectly via the papilla and the ductal system (Pinkas et al, 1994). For this reason, a selective endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy and a retrograde pancreatography must be performed to introduce a guidewire, over which the dilation of the cannulation can be performed. A double-pigtail endoprothesis should be inserted through the papilla into the cyst. No deaths (Dohmoto & Rupp, 1992; Pinkas et al, 1994; Sahel, 1990) and very low morbidity (2% to 7%) have been reported. A major problem of this approach is its nonfeasibility in patients with strictures or stones located between the papilla and the pseudocyst. Because these procedures call for a highly specialized endoscopist, cases with poor anatomic conditions or with contraindications determined by preliminary endosonography should be referred to a specialized center.

Common Bile Duct Stenting

Common bile duct stenosis is a mechanical complication of CP. A team approach that includes endoscopists and surgeons should guide the treatment of common bile duct stenosis in patients with CP. The decision for either interventional or surgical treatment depends on the patient’s age, comorbidities, the course of CP, and the cause of the stricture. A subgroup of patients has been reported to benefit from endoscopic stenting, with permanent regression of the stenosis reported after stent removal. Endoscopic stenting should be performed as first-line therapy in those patients with CP-induced acute cholestasis, when malignancy can be excluded. Especially for patients who refuse surgery or those who have significant comorbidities, the endoscopic approach might be the therapy of choice. Kahl and associates (2003) reported in a prospective follow-up study that endoscopic drainage of biliary obstruction provides excellent results in the short term but offers only moderate long-term results. Patients without calcifications of the pancreatic head benefit from biliary stenting; patients with calcifications were identified to have an increased risk of failure within a 12-month course of endoscopic stenting. Major limitations, such as plastic stent clogging, migration, and cholangitis, frequently occur in the long-term follow-up. Alternatively, self-expanding Wallstents may improve the results, and metal stents that cannot migrate offer a stent effectiveness greater than 80% (Ng & Huibregtse, 1998). At present, long-term follow-up data to clarify the role of endoscopic approaches and to identify the preferred stent for the management of cholestasis in CP are unavailable. The placement of Wallstents used to be irreversible, but results with the latest generation of stents that are covered, and therefore removable, are awaited. However, for young patients with CP and no comorbidity, adequate and definitive therapy for recurrent cholestasis is provided by a surgical drainage procedure or pancreatic head resection (Eickhoff et al, 2001).

Surgery

The surgical treatment of CP is based on two main concepts: preservation of tissue via drainage aims to protect against further loss of pancreatic function, and pancreatic resection is performed for nondilated pancreatic ducts, pancreatic head enlargement, or if a pancreatic carcinoma is suspected in the setting of CP. An overview on the common surgical procedures and the indications for surgery are listed in Table 55B.2.

| Indications for Surgery in Chronic Pancreatitis | |

|---|---|

| Intractable pain | |

| Symptomatic local complications | |

| Unsuccessful endoscopic management | |

| Suspicion of malignancy | |

| Surgical Techniques | Indications and Recommendations |

| Pure Drainage Operations | |

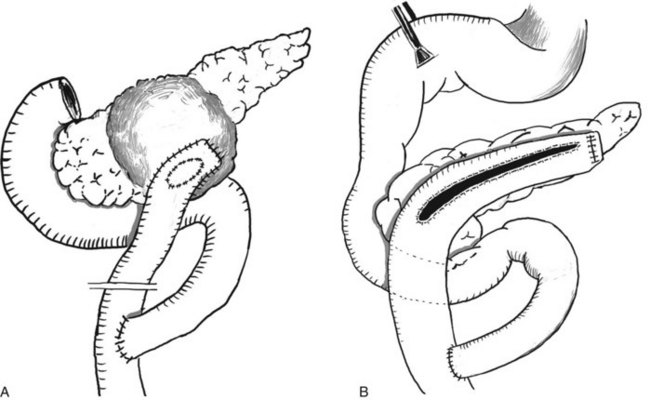

| Cystojejunostomy (see Fig. 55B.1A) | Surgical procedure of choice for isolated pseudocysts* |

| Laterolateral pancreatojejunostomy | Ductal dilation >7 mm without inflammatory mass |

| Partington-Rochelle procedure (see Fig. 55B.1B) | |

| Caudal drainage/Puestow procedure | Rare indications, replaced by other procedures |

| Resection Procedures | |

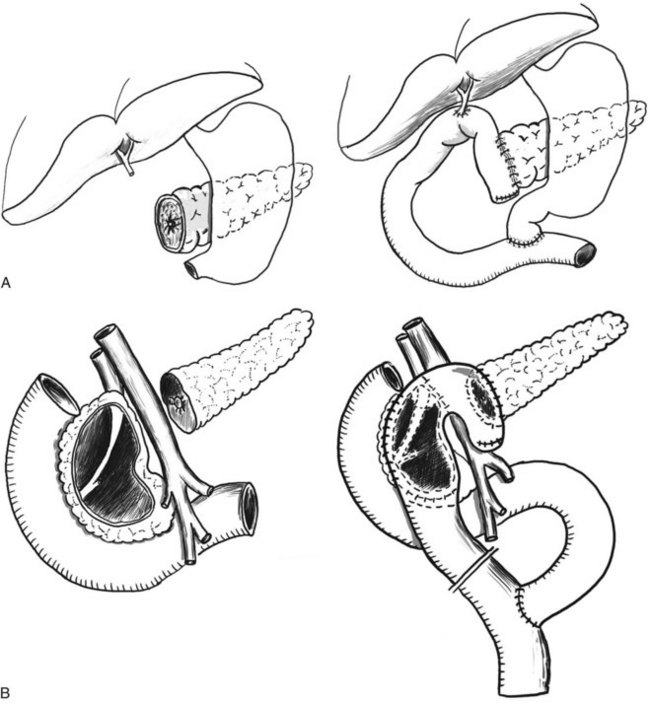

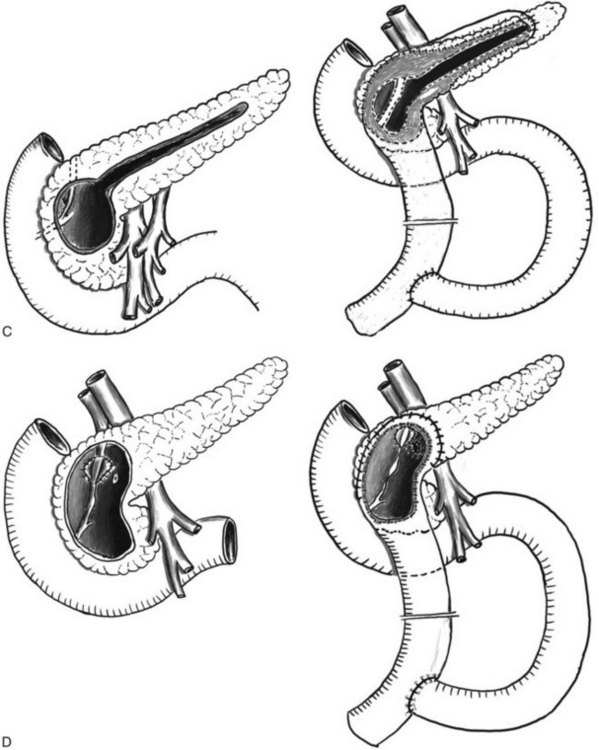

| Pancreatic head resection (see Fig. 55B.2) | Always include a ductal drainage |

| Procedure of choice if inflammatory mass is in the head of the pancreas | |

| All techniques have comparable results | |

| PD and ppPD (see Fig. 55B.2A) | Procedure of choice in suspected malignancy and in irreversible duodenal stenosis |

| DPPHR Techniques† | |

| DPPHR, Beger (see Fig. 55B.2B) | Procedures of choice if inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas |

| DPPHR, Bern (see Fig. 55B.2D) | Technically less difficult than Beger but equal in long-term outcome |

| DPPHR, Frey (see Fig. 55B.2C) | Patients with ductal obstruction in the head and tail and a smaller inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas |

| V-shaped excision | Small duct disease (diameter of pancreatic duct <3 mm) |

| Pancreatic left resection | Rare cases, such as isolated chronic pancreatitis in the tail (e.g., posttraumatic) |

| Rare cases of large psudocysts in the tail | |

| Segmental resection | Rare cases, such as isolated ductal stenosis in the body (e.g., posttraumatic) in patients without diabetes |

| Total pancreatectomy | Rare cases with severe changes in the entire pancreas and preexisting IDDM |

PD, pancreatoduodenectomy; ppPD, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; DPPHR, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

* Caution: intraoperative frozen section must be done to exclude a cystic neoplasm.

† Caution: intraoperative frozen section must be done to exclude malignancy.

Drainage Procedures

Pancreatic duct sphincterotomy was one of the first surgical procedures proposed for patients with CP and stenosis at the papilla of Vater. This procedure was recognized as a dangerous approach, however, with lower success rates for amelioration of pain, indicating that a stenosis at the papilla Vater is not the cause of pain in CP. The original Puestow procedure, and its modification by Partington and Rochelle (1960), proved more successful in patients with CP and a dilated pancreatic duct. The procedure includes resection of the tail of the pancreas, followed by a longitudinal incision of the pancreatic duct along the body of the pancreas and an anastomosis with a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum. The modification by Partington and Rochelle abandons the resection of the pancreatic tail. Preservation of tissue and reduction of mortality to less than 1% and of morbidity to less than 10% are the advantages of this operation (Evans et al, 1997; Izbicki et al, 1999; Prinz & Greenlee, 1981; Proctor et al, 1979). Although these ductal drainage operations have good primary success rates (Duval, 1956; Partington, 1952), their long-term outcome is poor (Markowitz et al, 1994). Moreover, these procedures are only promising if the duct is substantially dilated (>7 mm), which is the case in about 25% of patients (Büchler & Warshaw, 2008), and in patients who do not show a dominant mass in the head of the pancreas. For these reasons, pure drainage procedures have been replaced by techniques that combine resection and drainage for the majority of patients.

In patients with isolated pancreatic pseudocysts, and often in those with a history of a severe episode of acute pancreatitis, a drainage procedure in the form of a cystojejunostomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Fig. 55B.1) is still the surgical procedure of choice.

Resective Procedures

The vast majority of patients are seen with a ductal obstruction in the pancreatic head, frequently associated with an inflammatory mass. In these patients pancreatic head resection is the procedure of choice; the available techniques are shown in Figure 55B.2. The partial pancreatoduodenectomy, or Kausch-Whipple procedure, in its classic or pylorus-preserving variant, has been the procedure of choice for pancreatic head resection in CP for many years (Jimenez et al, 2000, 2003). The duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections and its variants—the Beger (Beger et al, 1985), Frey (Frey & Smith, 1987), and Bern procedures (Gloor et al, 2001)—represent less invasive, organ-sparing techniques with equivalent long-term results (see Table 55B.2).

Only very few patients come to medical attention with small duct disease (diameter of the pancreatic duct <3 mm) and no mass in the pancreatic head. In these cases, a V-shaped excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas is a safe approach and offers effective pain management (Yekebas et al, 2006). In the rare case of a patient seen with segmental CP in the pancreatic body or tail, such as that seen as a result of posttraumatic ductal stenosis, a middle segment pancreatectomy or a pancreatic left resection may be the best approach. The most frequently applied resection techniques are detailed here.

Partial Pancreatoduodenectomy: Kausch-Whipple Procedure (See Chapter 62A, Chapter 62B )

The most frequent indications for a pancreatoduodenectomy in patients with CP and pain are 1) the head of the pancreas is enlarged, often containing cysts and calcifications; 2) a previous endoscopic intervention or drainage procedure was ineffective; or 3) a malignancy is present in the head of the gland. Concerning the latter subgroup, it is commonly accepted that the distinction between benign and malignant disease remains an unsolved dilemma in some patients (up to 6% to 8%) (Büchler & Warshaw, 2008). The extent of resection in the classic Kausch-Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) includes the pancreatic head with duodenum and the lower third of the stomach. PD was initially designed for malignancies in the pancreatic head and was associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. With increasing safety the procedure has also been used for patients with CP (Traverso & Kozarek, 1993).

With the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (ppPD), a less invasive procedure for resection of cancer or CP was introduced, in which the stomach is preserved (see Fig. 55B.2A) (Traverso & Longmire, 1978). Today, PD and ppPD are safe and effective procedures in experienced hands, with an operative mortality of 2% to 5% and lasting pain relief in about 80% of patients (Büchler & Warshaw, 2008; Jimenez et al, 2000).

With regard to quality of life, the data after the Kausch-Whipple procedure are promising, although poor postoperative digestive function has been reported, including gastric dumping, diarrhea, peptic ulcer, and dyspeptic complaints in some patients. In up to 20% of the patients with CP, the Kausch-Whipple resection results in diabetes mellitus and subsequently in increased late postoperative morbidity and mortality (Izbicki et al, 1998).

The drawbacks of the Kausch-Whipple procedure may be ameliorated by the ppPD. The rate of gastric dumping, marginal ulceration, and bile-reflux gastritis can be reduced by preserving the stomach, pylorus, and the first part of the duodenum. Regarding quality of life, the ppPD provides better results than the classic PD, specifically with weight gain in around 90% of patients postoperatively. Furthermore, the operation leads to long-lasting pain relief in 85% to 95% of patients during the first 5 years postoperatively (Martin et al, 1996). The postoperative sequelae of transient delayed gastric emptying, which is observed in 30% to 50% of patients, and the risk of cholangitis and long-term occurrence of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency seen in more than 45% of patients represent the possible drawbacks of this operation in CP patients (Müller et al, 1997). The relevant studies (level I and II) concerning delayed gastric emptying comparing classic Kausch-Whipple and ppPD could not show a clear advantage of the classic Whipple procedure (van Berge Henegouwen et al, 1997; Büchler et al, 2000; Di Carlo et al, 1999; Izbicki et al, 1998; Jimenez et al, 2000; Klempa et al, 1995; Lin & Lin, 1999; Roder et al, 1992). Although three studies favored the ppPD, two showed no difference, and two showed lower delayed gastric emptying rates after a classic Whipple procedure compared with the ppPD.

Duodenum-Preserving Pancreatic Head Resection: Beger Procedure

The duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) was introduced by Beger and colleagues as a less radical, organ-sparing procedure designed specifically for patients with CP and an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas (Beger et al, 1985, 1989, 1999). Similar to PD, the pancreas is divided at the level of the portal vein (see Fig. 55B.2B). In contrast to PD, the pancreatic head is excavated with preservation of the duodenum and a layer of pancreatic tissue. In most cases, it is possible to free the bile duct from surrounding scar tissue. In patients with biliary obstruction (approximately 24%), the common bile duct must be opened so that the bile drains into the cavity of the resected pancreatic head (Beger et al, 1985). The mesoduodenal vessels should be respected, while removing the uncinate process. The standard reconstruction consists of a pancreatojejunostomy to the pancreatic tail and a side-to-side pancreatojejunostomy to the remnant of the pancreatic head using a Roux-en-Y loop of proximal jejunum. In about 10% of patients, DPPHR is combined with lateral pancreatojejunostomy as a consequence of multiple stenoses of the pancreatic main duct; the mortality rate is lower than 1%, and the morbidity rate is approximately 15% (Beger et al, 1985).

Compared with the Kausch-Whipple procedure, the DPPHR offers the advantage of preserving the duodenum. Its superiority over pylorus-preserving resection has been demonstrated in prospective studies (Beger et al, 1985; Büchler et al, 1995; Müller et al, 1997, 2008a). Patients who underwent DPPHR had greater weight gain, better glucose tolerance, and a higher insulin-secretion capacity (Büchler et al, 1995; Müller et al, 1997, 2008a). Over long-term follow-up, 20% of the patients developed new-onset diabetes mellitus. Compared with the natural course of CP, with normal glucose metabolism in 17% of patients (Lankisch et al, 1993), preserved endocrine function is seen in 39% following DPPHR.

With regard to pain status, DPPHR promotes the transformation of clinically manifest CP into a silent disease in around 91% of patients. In terms of quality of life, 69% of the patients were professionally rehabilitated, 26% retired, and only 5% were still in the status of disease after DPPHR (Köninger et al, 2004). Taking into account the better pain status, lower frequency of acute episodes of CP, decreased need for further hospitalization, low early and late mortality rates, and the restoration of quality of life, DPPHR seems to be able to delay the natural course of CP.

Duodenum-Preserving Pancreatic Head Resection: Frey Procedure

Frey and colleagues developed a modification of the DPPHR that represents a hybrid technique between the Beger and the Partington–Rochelle procedures (Frey & Amikura, 1994; Frey & Smith, 1987). Compared with the Beger procedure, the resection in the pancreatic head in the Frey modification is smaller and is combined with a laterolateral pancreatojejunostomy to drain the entire pancreatic duct toward the tail (see Fig. 55B.2C). Unlike the Beger procedure, the reconstruction can be performed with a single anastomosis. This procedure appears advantageous in patients with less severe inflammation in the head of the pancreas that is combined with an obstruction in the left-sided pancreatic duct.

Duodenum-Preserving Pancreatic Head Resection: Bern Modification

The Bern modification of the DPPHR represents a technical simplification of the Beger procedure with equal outcome (Gloor et al, 2001; Köninger et al, 2008; Müller et al, 2008b). The excavation of the pancreatic head can be performed to the same extent as the Beger procedure (see Fig. 55B.2D). However, unlike the Beger procedure, the pancreas is not divided at the level of the portal vein, which is often difficult because of inflammation and portal hypertension. In patients with portal hypertension, the risk of intraoperative bleeding is reduced by this modification (Gloor et al, 2001). The reconstruction after pancreatic head excavation can be performed by a single anastomosis between a jejunal loop and the pancreatic resection rim (Gloor et al, 2001). As in the Beger procedure, a bile duct obstruction can be managed by internal bile duct anastomosis. Thus the Bern modification of the DPPHR appears ideal for patients with an inflammatory mass and no stenosis in the left-sided duct. Adequate drainage of the pancreatic tail has to be verified by probing of the duct. If a stenosis is discovered, the resection can be extended toward the left, similar to the Frey and Partington-Rochelle procedures, until adequate drainage is achieved. In our collective experience, we have found this to be necessary in about 2% to 3% of patients (Strobel et al, 2009).

Left Pancreatic Resection in Chronic Pancreatitis

Pancreatic left resection can be performed with and without splenectomy. Distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein is time consuming. The advantage of avoiding a postsplenectomy syndrome and the importance of the spleen for the host defense system should be taken into consideration. If no clear indication for splenectomy is present, such as perisplenic pseudocyst or inflammatory or fibrotic encasement of the splenic vessels, preservation of the spleen may be appropriate (Aldridge & Williamson, 1991; Bauer et al, 2002; Warshaw, 1988). Importantly, in patients with spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy in whom the splenic vessels have been resected or in whom the splenic vein showed postoperative thrombosis, the development of left-sided portal hypertension with subsequent formation of gastric varices and potential variceal bleeding demands close follow-up (Balzano et al, 2007; Miura et al, 2005).

The surgical approach concerning the optimal closure technique of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy includes stump closure by sutures or stapler application or by creating a Roux-en-Y pancreatojejunostomy. Because the postoperative outcome is similar in both groups (Shankar et al, 1990), the drainage procedure should be reserved for patients with a dilated duct and/or a stricture in the pancreatic head (Aldridge & Williamson, 1991). Distal resection should not exceed 40% to 60% of the pancreatic gland to avoid postoperative insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) (Eggink et al, 1983). IDDM seems to be more of a long-term complication after pancreatic left resection, however, and it is difficult to differentiate whether this is due to pancreatic resection or simply the natural course of the disease.

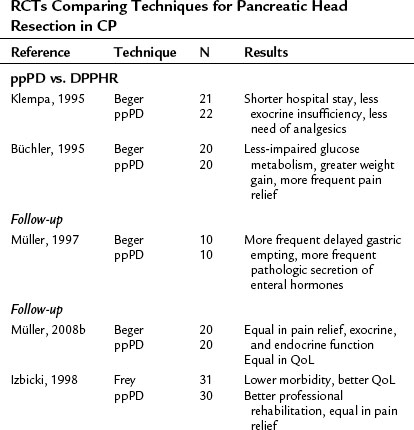

Evidence-Based Surgery in Chronic Pancreatitis: Pancreatoduodenectomy and DPPHR

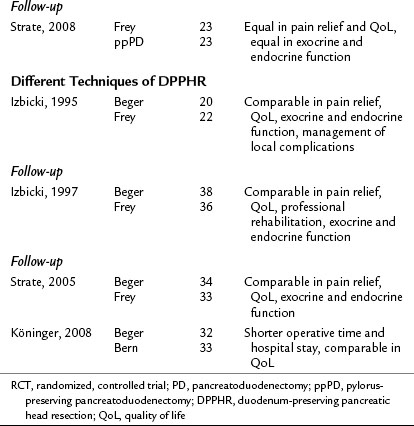

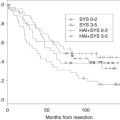

Irrespective of the technique, if carried out by experienced personnel, pancreatic head resection is a safe and effective therapy with good short- and long-term results in patients with CP and an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. Various techniques of pancreatic head resection were compared in several RCTs (Table 55B.3; Büchler et al, 1995; Izbicki et al, 1995, 1997, 1998; Klempa et al, 1995; Köninger et al, 2008; Müller et al, 2008a; Strate et al, 2003, 2008), in which their safety and efficacy were confirmed. The RCTs that compared PD and DPPHR (Büchler et al, 1995; Izbicki et al, 1998; Klempa et al, 1995; Müller et al, 2008a; Strate et al, 2008), as well as a recent meta-analysis (Diener et al, 2008), demonstrated comparable mortality and efficacy rates in terms of pain relief and endocrine insufficiency. The less invasive DPPHR was superior in terms of duration of hospital stay, exocrine insufficiency, weight gain, and quality of life in medium-term follow-up. In recent studies with long-term follow-up, these metabolic advantages appear to decrease over time, and long-term results of PD and DPPHR are equal in terms of pain management, quality of life, and endocrine and exocrine function (compare results reported in the initial trials and the latest follow-ups in Table 55B.3). Of interest, the resection techniques remain effective in terms of pain relief and quality of life but may not stop the progress of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency in the long term (Müller et al, 2008a; Strate et al, 2008). One explanation may be that resection effectively treats duct obstruction and hypertension but does not completely stop continued cellular damage and parenchymal loss (Büchler & Warshaw, 2008). Certainly these observations stress the importance of continued postoperative therapy, including the reduction of etiologic factors, substitution of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency, and possibly antioxidant therapy (Bhardwaj et al, 2009).

The RCTs that compared the various techniques of DPPHR demonstrated equal outcomes regarding pain control, quality of life, and metabolic parameters after the Beger procedure versus the Frey and Bern procedures (see Table 55B.3; Izbicki et al, 1995, 1997; Köninger et al, 2008; Strate et al, 2005). However, the trial by Köninger and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that the Bern modification of the DPPHR represents a technically simpler alternative, as reflected by a significantly shorter operative time (by 46 minutes) and a significantly shorter hospital stay (11 vs. 15 days). Thus the Bern technique represents a modification of the DPPHR that will find a broader acceptance in the future because of technical and economic advantages.

Adamek HE, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic stones treated with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Gut. 1999;45:402-405.

Aldridge MC, Williamson RC. Distal pancreatectomy with and without splenectomy. Br J Surg. 1991;78:976-979.

Ammann RW, et al. Course and outcome of chronic pancreatitis: longitudinal study of a mixed medical–surgical series of 245 patients. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:820-828.

Balzano G, Zerbi A, Di Carlo V. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with excision of splenic artery and vein: a cautionary note. World J Surg. 2007;31:1530.

Bauer A, et al. Pancreatic left resection in chronic pancreatitis: indications and limitations. In: Büchler, MW, et al. Chronic Pancreatitis: Novel Concepts in Biology and Therapy. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Science; 2002:529-539.

Beger HG, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1985;97:467-473.

Beger HG, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in severe chronic pancreatitis: early and late results. Ann Surg. 1989;209:273-278.

Beger HG, et al. Duodenum-preserving head resection in chronic pancreatitis changes the natural course of the disease: a single-center 26-year experience. Ann Surg. 1999;230:512-519.

Bhardwaj P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of antioxidant supplementation for pain relief in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:149-159.

Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Soehendra N. Endoscopic pseudocyst drainage: a new instrument for simplified cystoenterostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:112.

Bockman DE, et al. Analysis of nerves in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1459-1469.

Brady MS, et al. Effectiveness and safety of small vs. large doses of enteric coated pancreatic enzymes in reducing steatorrhea in children with cystic fibrosis: a prospective randomized study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1991;10:79-85.

Brown A, et al. Does pancreatic enzyme supplementation reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2032-2035.

Büchler MW, Warshaw AL. Resection versus drainage in treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1605-1607.

Büchler MW, et al. Randomized trial of duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pylorus-preserving Whipple in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1995;169:65-69.

Büchler MW, et al. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg. 2000;87:883-889.

Cahen DL, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676-684.

Ceyhan GO, et al. Pancreatic neuropathy and neuropathic pain: a comprehensive pathomorphological study of 546 cases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:177-186.

Ceyhan GO, et al. Neural fractalkine expression is closely linked to pain and pancreatic neuritis in human chronic pancreatitis. Lab Invest. 2009;89:347-361.

Costamagna G, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic stones in chronic pancreatitis: immediate and medium-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:231-236.

Delhaye M, et al. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy of pancreatic calculi. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:610-620.

Di Carlo V, et al. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus conventional Whipple operation. World J Surg. 1999;23:920-925.

Diener MK, et al. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pancreatoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:950-961.

DiMagno EP. Medical treatment of pancreatic insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54:435-442.

Di Sebastiano P, et al. Immune cell infiltration and growth-associated protein 43 expression correlate with pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1648-1655.

Di Sebastiano P, et al. Expression of interleukin 8 (IL-8) and substance P in human chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2000;47:423-428.

Di Sebastiano P, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: the perspective of pain generation by neuroimmune interaction. Gut. 2003;52:907-911.

Dite P, et al. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:553-558.

Dohmoto M, Rupp KD. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:118-124.

Dumonceau JM, et al. Treatment for painful calcified chronic pancreatitis: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56:545-552.

Duval MKJr. Caudal pancreaticojejunostomy for chronic pancreatitis: operative criteria and technique. Surg Clin North Am. 1956:831-839.

Ebbehoj N, et al. Pancreatic tissue fluid pressure in chronic pancreatitis: relation to pain, morphology, and function. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:1046-1051.

Eggink WF, et al. Surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis by distal pancreatectomy. Neth J Surg. 1983;35:184-187.

Eickhoff A, et al. Endoscopic stenting for common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis: results and impact on long-term outcome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1161-1167.

Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682-707.

Etzkorn KP, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: patient selection and evaluation of the outcome by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1995;27:329-333.

Evans JD, et al. Outcome of surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:624-629.

FitzSimmons SC. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1993;122:1-9.

Frey CF, Amikura K. Local resection of the head of the pancreas combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy in the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1994;220:492-504.

Frey CF, Smith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701-707.

Gardner TB, et al. Misdiagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: a caution to clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1620-1623.

Gloor B, et al. A modified technique of the Beger and Frey procedure in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2001;18:21-25.

Gress F, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of endoscopic ultrasound– and computed tomography–guided celiac plexus block for managing chronic pancreatitis pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:900-905.

Griffin SM, Alderson D, Farndon JR. Acid-resistant lipase as replacement therapy in chronic pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: a study in dogs. Gut. 1989;30:1012-1015.

Grimm H, Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. Endosonography-guided drainage of a pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:170-171.

Gullo L, Barbara L, Labo G. Effect of cessation of alcohol use on the course of pancreatic dysfunction in alcoholic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1063-1068.

Hamano H, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:732-738.

Havala T, Shronts E, Cerra F. Nutritional support in acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1989;18:525-542.

Izbicki JR, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1995;221:350-358.

Izbicki JR, et al. Drainage versus resection in surgical therapy of chronic pancreatitis of the head of the pancreas: a randomized study. Chirurg. 1997;68:369-377.

Izbicki JR, et al. Extended drainage versus resection in surgery for chronic pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial comparing the longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy combined with local pancreatic head excision with the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228:771-779.

Izbicki JR, et al. Surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis and quality of life after operation. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:913-944.

Jimenez RE, et al. Outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy with pylorus preservation or with antrectomy in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:293-300.

Jimenez RE, et al. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2003;27:1211-1216.

Johanns W, et al. Ultrasound-guided extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic ductal stones: six years’ experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 1996;10:471-475.

Johnson MD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical management of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:586-590.

Kahl S, et al. Risk factors for failure of endoscopic stenting of biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2448-2453.

Klempa I, et al. [Pancreatic function and quality of life after resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized comparative study after duodenum preserving resection of the head of the pancreas versus Whipple’s operation]. Chirurg. 1995;66:350-359.

Klöppel G. Chronic pancreatitis, pseudotumors and other tumor-like lesions. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(Suppl 1):S113-S131.

Köninger J, et al. [Duodenum-preserving pancreas head resection-an operative technique for retaining the organ in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis]. Chirurg. 2004;75:781-788.

Köninger J, et al. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection: a randomized controlled trial comparing the original Beger procedure with the Berne modification (ISRCTN No. 50638764). Surgery. 2008;143:490-498.

Lankisch PG, et al. Natural course in chronic pancreatitis: pain, exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and prognosis of the disease. Digestion. 1993;54:148-155.

Lankisch PG, et al. Epidemiology of pancreatic diseases in Luneburg County: a study in a defined German population. Pancreatology. 2002;2:469-477.

Layer P, Holtmann G. Pancreatic enzymes in chronic pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1994;15:1-11.

Lebenthal E, Rolston DD, Holsclaw DSJr. Enzyme therapy for pancreatic insufficiency: present status and future needs. Pancreas. 1994;9:1-12.

Levy P, et al. Estimation of the prevalence and incidence of chronic pancreatitis and its complications. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:838-844.

Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:603-607.

Loser C, Folsch UR. Differential therapy of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency: current aspects and future prospects of substitution therapy with pancreatic enzymes. Z Gastroenterol. 1995;33:715-722.

Markowitz JS, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Failure of symptomatic relief after pancreaticojejunal decompression for chronic pancreatitis: strategies for salvage. Arch Surg. 1994;129:374-379.

Martin RF, Rossi RL, Leslie KA. Long-term results of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1996;131:247-252.

Miura F, et al. Hemodynamic changes of splenogastric circulation after spleen-preserving pancreatectomy with excision of splenic artery and vein. Surgery. 2005;138:518-522.

Mohan V, Premalatha G, Pitchumoni CS. Tropical chronic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:337-346.

Mössner J, et al. Guidelines for therapy of chronic pancreatitis: Consensus Conference of the German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases, Halle 21-23 November 1996 [in German]. Z Gastroenterol. 1998;36:359-367.

Müller MW, et al. Gastric emptying following pylorus-preserving Whipple and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:257-263.

Müller MW, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial comparing Beger with pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:350-356.

Müller MW, et al. Perioperative and follow-up results after central pancreatic head resection (Berne technique) in a consecutive series of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196:364-372.

Ng C, Huibregtse K. The role of endoscopic therapy in chronic pancreatitis-induced common bile duct strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:181-193.

Noble M, Gress FG. Techniques and results of neurolysis for chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer pain. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:99-103.

Ohara H, et al. Single application extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is the first choice for patients with pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1388-1394.

Otsuki M, Tashiro M. 4. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, lifestyle-related diseases. Intern Med. 2007;46:109-113.

Park DH, Kim MH, Chari ST. Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:1680-1689.

Partington PF. Chronic pancreatitis treated by Roux-type jejunal anastomosis to the biliary tract. AMA Arch Surg. 1952;65:532-542.

Partington PF, Rochelle RE. Modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1960;152:1037-1043.

Pedrazzoli S, et al. Survival rates and cause of death in 174 patients with chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1930-1937.

Pinkas H, Dolan RP, Brady PG. Successful endoscopic transpapillary drainage of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:97-99.

Prinz RA, Greenlee HB. Pancreatic duct drainage in 100 patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1981;194:313-320.

Proctor HJ, et al. Surgery for chronic pancreatitis: drainage versus resection. Ann Surg. 1979;189:664-671.

Roder JD, et al. Pylorus-preserving versus standard pancreatico-duodenectomy: an analysis of 110 pancreatic and periampullary carcinomas. Br J Surg. 1992;79:152-155.

Rösch T, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a multicenter study of 1000 patients with long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765-771.

Sahel J. Endoscopic cysto-enterostomy of cysts of chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Z Gastroenterol. 1990;28:170-172.

Sahel J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic cysts. Endoscopy. 1991;23:181-184.

Santosh D, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized trial comparing fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous technique vs. endoscopic ultrasound-guided technique of coeliac plexus block for treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:979-984.

Sarles H, et al. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas: an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis. 1961;6:688-698.

Sauerbruch T, et al. Extracorporeal lithotripsy of pancreatic stones in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pain: a prospective follow-up study. Gut. 1992;33:969-972.

Schneider HT, et al. Piezoelectric shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2042-2048.

Shankar S, Theis B, Russell RC. Management of the stump of the pancreas after distal pancreatic resection. Br J Surg. 1990;77:541-544.

Smits ME, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic stones in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:556-560.

Strate T, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:97-106.

Strate T, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing the Beger and Frey procedures for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:591-598.

Strate T, et al. Resection vs. drainage in treatment of chronic pancreatitis: long-term results of a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1406-1411.

Strobel O, Büchler MW, Werner J. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection: technique according to Beger, technique according to Frey and Berne modifications. Chirurg. 2009;80:22-27.

Traverso LW, Kozarek RA. The Whipple procedure for severe complications of chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1047-1050.

Traverso LW, Longmire WPJ. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:959-962.

van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:373-379.

van der Hul R, et al. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy of pancreatic duct stones: immediate and long-term results. Endoscopy. 1994;26:573-578.

Wang LW, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of chronic pancreatitis in China: a retrospective multicenter analysis over 10 years. Pancreas. 2009;38:248-254.

Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1988;123:550-553.

Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis: new insights into acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1999;45:317-322.

Winstead NS, Wilcox CM. Clinical trials of pancreatic enzyme replacement for painful chronic pancreatitis: a review. Pancreatology. 2009;9:344-350.

World Health Organization, 1990: Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care: Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Yekebas EF, et al. Long-term follow-up in small duct chronic pancreatitis: a plea for extended drainage by “V-shaped excision” of the anterior aspect of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2006;244:940-946.

Zentler-Munro PL, et al. Therapeutic potential and clinical efficacy of acid-resistant fungal lipase in the treatment of pancreatic steatorrhoea due to cystic fibrosis. Pancreas. 1992;7:311-319.