The penis and scrotum231

22.2 The prostate232

The male genital tract consists principally of the penis, foreskin, testes, epididymes and prostate gland. A large range of disease processes affect the male genital tract, but inflammation and tumours are probably the most important clinically. Malignancies of the testis and prostate are particularly common tumours and it is important that you have a working knowledge of these. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are also seen and may affect a variety of organs in the male genital tract. Congenital diseases are also common and vary from the relatively insignificant (overly long foreskin) to the very significant (e.g. the maldescended testis with the associated increased risk of malignancy).

22.1. The penis and scrotum

The penis is a skin-covered organ (as is the scrotum) and can therefore exhibit many of the common skin disorders (e.g. eczema/dermatitis). In addition, the penile urethra may be susceptible to tumours of the urothelium (proximally) and squamous epithelium (distally).

Congenital disorders

Abnormalities include an excessively small penis (micropenis) or a urethra that opens either on the ventral (under) surface (hypospadias) or dorsal surface (epispadias) of the penis rather than at the tip.

Acquired disorders

Inflammatory disorders

Many inflammatory skin conditions can occur in the penis, foreskin and scrotum, such as eczema, psoriasis and lichen planus. In addition, more specific inflammatory diseases may cause penile (skin) inflammation.

Granuloma inguinale

Granuloma inguinale is caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. This is an STD and causes an ulcer on the glans.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an STD caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (which also causes non-specific urethritis). Males may be asymptomatic carriers of the organism. The infection causes a spontaneously healing red papule on the penis. Enlarged lymph nodes in the groin then develop, which then become soft and attach to the overlying skin. Sinus formation occurs.

Syphilis (caused by the spirochaete, Treponema pallidum), herpes simplex and human papilloma virus (HPV) are all important causes of penile infection (see Table 41).

| Infection | Organism | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|

| Syphilis | Treponema pallidum (bacterium, spirochaete) | Rare Penis usually involved in primary syphilis (‘chancre’ seen – nodule on penis). Heals after about 1month Penis can be involved in secondary syphilis (papular rash) |

| Herpes simplex | Herpes simplex virus (herpes virus) | Common Painful recurrent blisters/ulcers on penile skin May last 2–3weeks then resolve Virus can remain latent in sacral sensory ganglia and reactivate/recur |

| Human papilloma virus | Human papilloma virus (HPV; papillomavirus) | Causes condylomata acuminata (‘venereal warts’) Especially types 6 and 11 Types 16 and 18 can cause premalignant and malignant conditions |

| Chancroid | Haemophilus ducreyi | Rare Penile ulceration and inguinal lymphadenopathy |

Peyronie’s disease is a penile disease of unknown cause in which the penis becomes excessively curved or bowed due to accumulation of scar tissue (the curvature may make sexual intercourse impossible).

Tumours

The penis can be affected by both in situ and invasive (squamous) malignancies. Benign tumours of the penis are rare.

Intra-epithelial neoplasia

Unfortunately, there are three very confusing historical names for intra-epithelial dysplasia in the region of the penis and scrotum (see Table 42).

| On glans | On shaft | Glans + shaft |

|---|---|---|

| Erythroplasia of Queyrat | Bowen’s disease | Bowenoid papulosis |

| Red patches | Pale, thickened areas | Velvety papules (younger men) HPV-associated in most cases |

Squamous cell carcinoma

This is a relatively rare tumour in Western countries (and very rare in circumcised males), but occur more frequently in parts of Asia and Africa. A poorly retracting infected foreskin and infected glans are probably risk factors. There is an association between HPV 16 and 18 infection and squamous cell carcinoma. The tumour may vary from a papillary and well-differentiated malignancy with abundant keratin formation to a solid, ulcerated, widely invasive, poorly differentiated lesion (which spreads via lymphatics to local lymph nodes).

22.2. The prostate

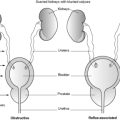

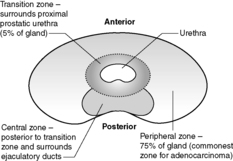

The prostate is a 20g, walnut-shaped gland located in the male perineum. The exact function of the gland is still unclear. The gland lies subjacent to the bladder and is traversed by the urethra. Any enlargement of the prostate gland, particularly that part surrounding the urethra (see Figure 60 for zones of the prostate), can lead to reduction/obstruction of flow of urine –dribbling, hesitancy, poor stream or complete blockage (retention). The prostate is composed of glandular and fibromuscular components, and it is hyperplasia/hypertrophy of both of these elements and malignancy of the glandular elements that commonly lead to urinary symptoms.

|

| Figure 60 |

Hyperplasia of the prostate

This is such a common finding in adult men that it is often considered to be a normal part of ageing (probably about 80% of 80-year-olds will have evidence of prostatic hyperplasia). The prostate has a nodular, whorled appearance to the naked eye (nodular hyperplasia). It is mainly the periurethral and transition zones that are affected. Down the microscope, the glandular and/or stromal components may be affected. The glands may become papillary in form, or cystically dilated. However, hyperplastic glands have two cell layers – an inner clear cell layer and an outer, more darkly staining, basal cell layer. Hyperplasia of the prostate is often accompanied by areas of infarction, chronic inflammation and glandular atrophy.

Acute and chronic prostatitis can also occur in the setting of urinary tract infection (UTI) with organisms such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella.

Carcinoma of the prostate

Carcinoma of the prostate is a very common malignancy. The biological behaviour of this tumour is poorly understood – a significant number of latent and incidental cancers are found at autopsy or in tissue removed at operation on an apparently benign prostate (e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate, TURP). Thus, it is likely that some prostatic cancers either never progress or only do so very slowly. The disease is more common in older men (particularly those aged over 60) and is seen more often in black men than in white men or Asian men. A small number of prostatic cancers appear familial. Most cases (about 70%) arise in the peripheral zone of the prostate.

Macroscopically, it is usually difficult to see prostatic cancer (it may or may not cause gland enlargement). On microscopy, prostatic cancer is usually an adenocarcinoma (although leiomyosarcoma and lymphoma occur, and rhabdomyosarcoma may be seen in children; Table 43). The Gleason grading system is now widely used for prostatic adenocarcinoma. This system depends on the glandular differentiation and pattern of infiltration of the tumour (see Table 44).

| Incidence | Age >50years (very common in >80-year-olds) |

| Risk factors | Black men > white men > Asians + family history ?fats in diet ?androgen-driven |

| Associated lesions | High-grade PIN (particularly multifocal) |

| Clinical presentation | Incidental finding Urinary symptoms |

| Diagnosis | Per rectal examination, ultrasound scan and biopsy Blood levels of prostatic-specific antigen (PSA) |

| Macroscopic | Usually invisible to the naked eye |

| Microscopic | Gleason scoring system (see Table 44) |

| Pattern of spread | Local versus lymphatic versus blood |

| Treatment | Carefully supervised ‘watch and wait’ (small intraprostatic lesions) Surgery Radiotherapy |

| Gleason grade (or pattern) | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1 | Uncommon Very round, regular, monotonous, closely packed glands Well circumscribed |

| 2 | Similar to 1, but less circumscribed, some variation in gland size and shape |

| 3 | Commonest grade May be small or large glands or cribriform (sieve-like) pattern May be marked variation in size/shape of glands Ragged edges and infiltrates widely |

| 4 | Glands now fused together Nests and streams of cells seen |

| 5 | Large sheets of malignant cells Necrosis may be seen May be very undifferentiated |

The higher the Gleason score (achieved by adding together the commonest two patterns or doubling a single pattern tumour) the more poorly differentiated the tumour. There is a correlation between the score of the tumour and its biological behaviour (the higher the score, the higher the cancer mortality rate). The tumour may be associated with high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (PIN; thought to be a likely precursor lesion). Adenocarcinoma of the prostate typically invades locally through the gland and into surrounding pelvic tissues and then by lymphatics to local/regional lymph nodes. Prostatic cancer has a propensity to metastasise via the bloodstream to bones (particularly the spine).

22.3. The testis and epididymis

The testis

Each testis is composed of densely packed, coiled seminiferous tubules, which are lined by Sertoli cells (regulatory cells) and germ cells (which mature into spermatozoa). In the normal adult testis, luminal spermatozoa are seen. Between the tubules lies the interstitium, which has the Leydig cells. These cells secrete testosterone under the influence of luteinising hormone from the anterior pituitary gland.

Congenital abnormalities of the testis

The immature (prepubertal) testis has small seminiferous tubules, which contain mainly Sertoli cells and only a very small number of germ cells.

Torsion

Torsion of the testis, i.e. twisting of the spermatic cord, leading to vascular (most often venous) obstruction of the testis, is usually caused by a congenital, structural abnormality of the testis and may lead to haemorrhagic necrosis.

Inflammatory conditions

Inflammation of the epididymis is more common than the testis. There may be severe pain in the scrotal area. Non-specific epididymitis and orchitis are usually associated with UTIs. Causative bacteria include E. coli in older men and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in young adults.

Histologically, non-specific acute/acute-on-chronic inflammation may be seen, together with abscess formation and, eventually, scarring.

Testicular tumours

Testicular tumours are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in young and middle-aged men. There is a wide range of tumours of the testis and the nomenclature can be confusing and, unfortunately, different systems are used in different parts of the world. Most testicular tumours present as painless enlargement of the testis.

Broadly speaking, tumours of the testis can be divided into two groups:

• germ cell tumours (about 90%)

• non-germ cell tumours.

Germ cell tumours

These can be:

• seminomas

• non-seminomatous tumours

• combined seminomas and non-seminomatous tumours.

Classification of germ cell tumours of the testis

The two main classification systems are the World Health Organization (WHO) system and the British system (Table 45).

| British Testicular Tumour Panel | WHO |

|---|---|

| Seminoma Classical Spermatocytic |

Seminoma Typical Spermatocytic |

| Malignant teratoma | |

| Undifferentiated (MTU) Intermediate (MTI) Differentiated (MTD) Trophoblastic (MTT) |

Embryonal carcinoma and teratoma Teratoma, mature/immature/with malignant transformation Choriocarcinoma Yolk sac tumour |

Both systems are based on recognition of the wide spectrum of morphological patterns seen in germ cell tumours (Table 46). It is believed that the precursor lesion for most germ cell tumours is intratubular germ cell neoplasia. In this condition, large, pleomorphic, vacuolated malignant cells are seen in atrophic (non-spermatozoa-producing) seminiferous tubules (often seen around invasive germ cell tumours).

| NB: Testicular germ cell tumours secrete hormones/enzymes/proteins into the patient’s blood and these can be used as a ‘marker’ for progression/response to treatment/relapse of the tumour. Examples include α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotrophin and lactate dehydrogenase. Treatment/prognosis of these tumours depends on histology and extent of spread. Options include surgery alone, or with chemoradiotherapy. | |||||

| Seminoma | Embryonal carcinoma | Yolk sac tumour | Choriocarcinoma | Teratoma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour | Low-grade malignancy | Aggressive | Variable | Very aggressive | Variable |

| Frequency | Commonest type of germ cell tumour | Commonest testicular tumour in infants (pure form). Usually mixed with embryonal carcinoma in adults | Rare | Common in infants to adults but pure forms common in infants Adults – usually mixed | |

| Naked eye appearance | Large, white mass | Variegated appearance with haemorrhage and necrosis | Yellowish, mucinous appearance | Small haemorrhagic nodule | Large, cystic solid masses |

| Microscopy | Large cells with large nuclei and clear cytoplasm Well-demarcated cell membranes Fibrous septae with chronic inflammatory cells |

Large, pleomorphic overlapping cells with numerous mitoses | Lacy lines of tumour cells Pink globules (containing α-fetoprotein and α1-antitrypsin, seen in and outside cells |

Cytotrophoblastic and syncytiotro-phoblastic cells seen (latter contain human chorionic gonadotrophin) | Haphazard arrangement of often mature tissues such as cartilage, muscle, neural tissue, fat, etc. Rarely a focus of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma may be seen (malignant transformation) |

Germ cell tumours tend to spread initially by lymphatics to the iliac and retroperitoneal (para-aortic) lymph nodes. Bloodstream spread occurs to the lungs, liver, bones and brain. Clinical staging of germ cell tumour is shown in Table 47.

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| PT0 | Histological scar in testis |

| PTis | Intratubular germ cell neoplasia |

| T1 | Tumour confined to testis/epididymis No lymphatic/vascular invasion Tunica albuginea may be invaded |

| T2 | As for T1, but lymphatic/vascular invasion seen or tumour extends through tunica albuginea and invades tunica vaginalis |

| T3 | Tumour invades spermatic cord ± lymphatic or vascular invasion |

| T4 | Tumour invades scrotum ± lymphatic or vascular invasion |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass ≤2cm and up to five positive nodes (≤2cm) |

| N2 | Lymph node mass >2cm but ≤5cm, or more than five positive nodes (≤5cm), or extranodal tumour spread |

| N3 | Lymph node mass >5cm |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

| M1a | Non-regional lymph nodes or lung |

| M1b | Other sites |

Other testicular tumours

Other testicular tumours include sex cord stromal tumours, Sertoli cell tumours and lymphomas.

Epididymis

The epididymis is posterolateral to the testis and functions to store, concentrate and transport spermatozoa. The epididymis is most often affected by inflammatory conditions (epididymitis). This may then affect the testis (epididymo-orchitis). The inflammation is often bacterial in origin (E. coli, Gonococcus or Chlamydia).

Self-assessment: questions

True-false questions

1. Germ cell tumours of the testis:

a. are most common in the over 70s

b. may be associated with in situ malignancy

c. can produce human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG)

d. are of uniformly poor prognosis

e. commonly spread by the lymphatics

2. Prostatic adenocarcinoma:

a. may be incidental

b. is the only cause of a raised serum prostatic-specific antigen (PSA)

c. is usually centrally located in the prostate gland

d. has a predilection for metastasising to bone

e. is staged using the Gleason system

3. The following statements are correctly paired:

a. maldescent of the testis – increased risk of testicular lymphoma

b. squamous cell carcinoma of the foreskin – circumcised men

c. epididymitis – E. coli urinary tract infection

d. spermatocytic seminoma – widespread metastases

e. yolk sac tumour – α-fetoprotein (AFP) production

4. The following statements are correct:

a. testicular torsion is usually painless

b. balanitis xerotica obliterans is similar to lichen sclerosus

c. epispadias is a condition of the epididymis

d. cancer of the glans penis is usually a squamous cell carcinoma

e. a poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma would have a Gleason score of about 8–10

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 30-year-old man noticed a steadily enlarging, painless lump in his right testis. He had no significant medical or surgical history. His general practitioner refers him for an urgent ultrasound examination. This showed a cystic and solid tumour mass. Special blood tests were performed. The following day his right testis was removed.

1. What are the likely differential diagnoses?

2. What is the most likely diagnosis now and what ‘special blood tests’ would have been done?

Histology showed a malignant teratoma and areas of classical seminoma.

3. What does the term teratoma mean?

Case history 2

A 93-year-old man presented to his general practitioner having noticed a hard, painless lump under his foreskin. He did not know how long the lump had been there. On examination, he had a craggy 15mm mass under the foreskin.

1. What is the likely diagnosis? What are the risk factors for this?

He was referred to a urologist who did a biopsy. The report read: ‘This is an ulcerated, invasive, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour is seen in lymphatic channels …’.

2. Where is the tumour likely to spread?

Short note questions

Write short notes on:

1. Testicular swellings/tumours.

2. Prostatic adenocarcinoma.

3. Penile cancer.

4. Principles of grading and staging – use the male genital tract to illustrate your answer.

Viva questions

1. What are the risk factors for prostatic/testicular cancer?

2. What is the definition of teratoma (versus hamartoma)?

3. What are the methods of monitoring effects of treatment in prostatic and testicular cancer?

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

1. e. Prostatic hyperplasia mainly affects the central region of the gland, in contrast with carcinoma, which usually arises in the gland periphery. As hyperplasia affects the central periurethral region, it often presents with symptoms of urinary obstruction. Hyperplasia affects the majority of older men (probably 80% by 80years of age). Benign prostate glands (normal or hyperplastic) have two layers – a basal outer layer and an inner luminal cell layer. Malignant prostatic glands are composed of only one layer. Prostatic carcinoma is commoner in black and white men than in Asian men. It often cannot be seen on naked-eye examination of the gland.

True-false answers

1.

a. False. Germ cell tumours of the testis are commonest in the 15–40-year-old age group. In fact, testicular tumours in men over the age of 70 are quite unusual – many turn out to be lymphomas.

b. True. In many cases, in situ germ cell tumour (germ cell tumour confined inside the seminiferous tubules) will be seen around the periphery of the frankly invasive tumour. The tubules containing the tumour cells are usually atrophic (showing no spermatogenesis).

c. True. Testicular seminomas may contain giant cells and syncytial-like cells (i.e. resembling normal human placental tissues) and human chorionic gonadotrophin is contained in, and secreted by, these cells. This can lead to a modestly elevated level of hCG in the blood of these patients. In addition, choriocarcinoma, a highly malignant tumour made up of cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast (again tissue seen in the normal human placenta), can cause a massive outpouring of hCG into the bloodstream (since urinary hCG is the basis of the pregnancy test, it is therefore possible for a man to have a positive pregnancy test). Markers like hCG can be used to monitor the success of treatment (has all the hCG-producing tumour been removed and the level therefore fallen to baseline?) and relapse (the level did fall to baseline but now it has risen again – is there a new tumour somewhere in the body?).

d. False. The prognosis for many of the testicular germ cell tumours is excellent. For instance the survival for a stage I (testis-confined) seminoma is almost 100%.

e. True. Germ cell tumours spread by the lymphatics and bloodstream. The common lymph node groups involved are the retroperitoneal para-aortic lymph nodes (further spread to the mediastinal and supraclavicular lymph nodes then occurs). Blood spread is to lungs, liver, central nervous system and bones.

2.

a. True. Carcinoma of the prostate is a very common malignancy. A small, but significant, number of tumours are found incidentally (e.g. when prostatectomy tissue is examined under a microscope during life or after autopsy).

b. False. An elevated PSA in the blood is not only malignancy related. Prostatitis, and digital examination/instrumentation of the prostate are among other causes of a raised blood PSA (there is still much controversy whether PSA should be used as a screening test for prostatic cancer).

c. False. About 70% of cases of prostatic cancer are found in the peripheral part of the gland (usually posteriorly, hence the importance of good digital rectal examination of the prostate).

d. True. Prostate cancer tends to spread initially locally through the capsule into surrounding nearby structures such as the seminal vesicles and bladder. Lymphatic spread may occur to the obturator, perivesical, iliac and para-aortic lymph node groups and by the bloodstream to bone (remember that cancers of the breast, kidney, thyroid, lung and prostate have a tendency to metastasise to bone). Prostatic metastases tend to induce new bone formation (i.e. they are osteoblastic).

e. False. Gleason is a grading system not a staging system.

3.

a. False. Abnormalities of the descent of the testis are associated with an increased risk of germ cell tumours, not lymphomas.

b. False. Uncircumcised men have an increased risk of carcinoma of the foreskin/glans.

c. True.

d. False. Spermatocytic seminomas are a special category of seminoma. They are often found in older men and are composed of a mixed population of cells, which look like various sperm precursors. In situ germ cell tumour is not associated with these tumours, which do not metastasise.

e. True. This pattern of differentiation resembles adenocarcinoma but the cells form tubules or papillae. It reflects an extraembryonic differentiation pattern. The normal human yolk sac produces AFP in the embryo and usually does so when malignant yolk sac tissue is produced in the testis. Again this protein will be found in the blood and can be used to monitor treatment/relapse of the tumour.

4.

b. True. Balanitis xerotica obliterans is, in fact, the male analogue of lichen sclerosus of the vulva. Neither condition is well understood. Both present as thickened, white patches and, on microscope examination, show reactive/atrophic epithelial changes with a subjacent zone of hyalinised connective tissue, below which chronic inflammation is seen. It may be a premalignant condition.

c. False. Epispadias and hypospadias are both conditions relating to the position of the urethral opening on the penis.

d. True.

e. True. The higher the Gleason score of a prostatic cancer, the poorer the degree of differentiation (i.e., roughly speaking, a score of 2–4 = well differentiated; 5, 6 = moderate; and 7–10 = poorly differentiated).

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. Obviously, a full history with clinical examination is required. Often, the fact that the lump is growing and is painless is actually more worrying (and more strongly suggests cancer) than if the lump was painful (which may suggest inflammation/ infection). It is probably better to assume the lump is malignant and send the patient for urgent ultrasound. This type of investigation is often conclusive as to whether the lump is benign or malignant (or inflammatory, etc.).

2. With the ultrasound results strongly suggesting this is tumour, preoperative blood tests should be done, including the ‘markers’ of hCG and AFP (looking for choriocarcinoma and yolk sac tumour elements in the tumour). After the operation, further imaging (of abdominal lymph node groups for instance) may be required.

3. Teratomas are tumours that show endodermal, mesodermal and ectodermal elements of differentiation. In essence, they may be mature (showing fully differentiated elements such as intestinal epithelium, muscle and skin), immature (incomplete differentiation of any of the elements of the tumour seen) or show malignant transformation (cancer, e.g. adenocarcinoma, seen developing in a mature teratoma). Some germ cell tumours contain both seminoma and teratoma.

Case history 2

1. This is very likely to be a squamous cell carcinoma of the glans penis. The risk factors for this tumour include:

• uncircumcised penis

• poor penile hygiene, with carcinogen accumulation in smegma

• infection with HPV types 16 and 18.

2. Squamous cell carcinoma of the glans penis is usually a slow growing tumour of older men and spreads to the inguinal and iliac lymph node groups (the 5-year survival rate is about 30% for tumours that have metastasised to regional lymph nodes).

Short note answers

1. With all these types of questions, it is important to set out the response in a logical fashion.

Comment: Remember, common things are common. Congenital as well as acquired things should be on your list (consult surgical textbooks for comprehensive guides for examining the testis and its lumps/bumps!).

2 and 3. Comment: In these sorts of questions you need to go through your ‘memory jogger list’ again (e.g. definition, age, sex, incidence, geography, aetiopathogenesis, macro-, micro-, spread, management) to try to shape your answer into a well-drilled, succinct response. It is worth having a set of hand-written or typed revision sheets/cards for important tumours (set out with these similar headings).

4. Comment: Applications of grading and staging is a very common question in undergraduate (and, for that matter, postgraduate) exams.

Viva answers

| Risk factor | Comments |

|---|---|

| Age | Peak age for germ cell tumours is 25–45years Only yolk sac tumour is common in children |

| Cryptorchidism | A non-descended testis has an increased risk of developing a tumour |

| Genetics | Some testicular tumours are familial |

| Abnormally formed gonad | Testicular dysgenesis predisposes to malignancy |

2. A hamartoma is a mass made up of haphazardly arranged, but differentiated, tissues normally found in the area in which the mass is found. Thus, a lung hamartoma may contain a jumble of cartilage and glandular epithelium. Although it may be rapidly growing, it is not malignant.

3. Blood markers can be used (PSA in prostate cancer and AFP/hCG in testicular cancer).