20.2 Benign breast conditions209

20.3 Breast cancer209

20.4 Diagnosis of breast lesions209

20.5 The male breast209

Self-assessment: questions209

Self-assessment: answers209

20.1. The normal female breast

Structure and function

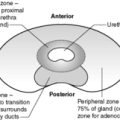

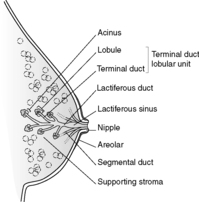

The function of the female breast is to produce and express milk. The functional unit of the breast is called a lobule (Figure 56) and there are numerous lobules within each breast. A lobule consists of a variable number of acini (glands) lined by secretory epithelium. The acini connect to, and drain into, a terminal duct. Each terminal duct and its acini are together referred to as the terminal duct lobular unit. The terminal ducts drain via a series of larger ducts into the lactiferous ducts and sinuses. The lactiferous ducts open onto the skin surface at the nipple. The nipple and areola are covered by stratified squamous epithelium, and the areolar skin is pigmented. Areolar glands of Montgomery produce secretions to lubricate the nipple during lactation.

|

| Figure 56 |

The ducts and acini are lined by two cell types – an inner layer of secretory epithelium and an outer layer of myoepithelial cells. Surrounding and supporting the ducts and acini is breast stroma, which consists of loose connective tissue.

Hormonal influences on the breast

Breast tissue is sensitive to many different hormones. The breast undergoes minor changes with the menstrual cycle, more significant changes during pregnancy and lactation, and undergoes involution when hormone stimulation is withdrawn (menopausal and postmenopausal period).

Changes with the menstrual cycle

After ovulation, there is epithelial proliferation and an increase in the number of acini, and the breast stroma becomes oedematous. These changes occur under the influence of oestrogen and rising levels of progesterone. With menstruation, there is a drop in the levels of these sex steroids with consequent apoptosis of epithelial cells and disappearance of the stromal oedema. The breast becomes quiescent again until the next ovulation.

Pregnancy and lactation

A number of hormones, including oestrogen, progesterone, prolactin and growth hormone, are important in the development of the breast during pregnancy. During pregnancy, there is a marked increase in the number of acini and lobules within the breast at the expense of the stroma. The epithelial cells begin to synthesise milk, which is stored in secretory vacuoles in the cell cytoplasm. With delivery of the baby, the levels of oestrogen and progesterone fall, and the activity of prolactin causes the secretion of milk (lactation).

When breastfeeding ceases, the breast tissue regresses back towards the pre-pregnancy state.

Involution

With increasing age and the reduction in the levels of circulating sex steroids, the ducts and acini begin to atrophy and the amount of breast stroma decreases. In the very elderly, the acini may be completely lost, leaving only breast ducts in a little stroma.

20.2. Benign breast conditions

Inflammation

Acute mastitis

Acute mastitis is the most common inflammatory disorder of the breast, and is usually confined to the lactation period. During breastfeeding, the nipple can develop fissures and cracks. Via these cracks, bacteria (usually Staphylococcus aureus) gain access to the breast tissue. The infection is usually confined to one segment of the breast, and is manifest by oedema and erythema of the overlying skin.

If severe and untreated, the acute inflammation may progress to abscess formation.

Mammary duct ectasia

This term is used to refer to dilatation of the breast ducts. The ducts become filled with inspissated breast secretions and there is associated inflammation and fibrosis. If there is an unusually heavy infiltrate of plasma cells, the term ‘plasma cell mastitis’ is sometimes applied. The aetiology of mammary duct ectasia is unknown. Affected women can present with a palpable mass, skin retraction or nipple discharge, which can occasionally be blood-stained. The lesion is of clinical importance because it can be mistaken for carcinoma clinically, grossly and mammographically.

Fat necrosis

This lesion is usually related to previous trauma to the breast, although a history of trauma may not always be obtained. Histologically, there is an initial focus of necrotic fat cells and acute inflammation, which then becomes heavily infiltrated by macrophages that engulf the debris and hence develop a lipid-laden ‘foamy’ appearance. With healing, the focus often becomes replaced by fibrous tissue and there may be (dystrophic) calcification. Affected women present with a palpable breast lump or nipple retraction, raising the suspicion of carcinoma. If there is calcium deposition, lesions may also mimic carcinoma mammographically.

Granulomatous mastitis

This condition is rare. Causes include infections (e.g. tuberculosis, deep-seated fungal infections) and systemic disorders (e.g. Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoid).

Fibrocystic changes

This term is used to refer to a wide range of morphological changes to the breast. Fibrocystic change is the commonest disorder of the breast. The exact pathogenesis remains obscure but hormonal imbalances are thought to be important. Affected women are usually aged between 30 and 55 with a marked decrease in incidence after the menopause. The clinical features vary depending on the underlying morphological changes but, in general, fibrocystic change can mimic carcinoma clinically by producing palpable lumps, nipple discharge and mammographic densities. Evidence indicates that some of these conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing carcinoma of the breast (see later).

The morphological subtypes of fibrocystic disease are listed below:

• adenosis

• cysts

• apocrine metaplasia

• fibrosis

• epithelial hyperplasia

• sclerosing adenosis

• radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions.

An individual may show one, or some, or a combination of all of these changes.

Adenosis

This term denotes an increase in the number of acini within a lobule. The gland lumina in adenosis occasionally contain calcium deposits.

Cysts

This term refers to cystic dilatation of acini or terminal ducts. Some cysts may reach a very large size (up to 2–3cm across). The secretions within cysts may calcify.

Apocrine metaplasia

Fibrosis

This is probably a secondary event to rupture of cysts and it may proceed to hyalinisation.

Sclerosing adenosis

In this condition, there is an increased number of acini and increased intralobular fibrosis. The fibrosis causes marked distortion of the acini. The lesion can present as a mammographic density or a palpable mass, therefore mimicking carcinoma. Sclerosing adenosis may be mistaken for carcinoma histologically also. Radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions are morphological variants of sclerosing adenosis, and are characterised by:

• a stellate shape

• a central area of fibrosis and elastosis

• a variable degree of adenosis and distortion of acini.

Radial scar is the term reserved for lesions less than 10mm in diameter, whereas larger lesions are called complex sclerosing lesions. They can mimic carcinoma clinically, mammographically and histologically.

Epithelial hyperplasia

Epithelial hyperplasia is defined as an increase in the number of layers of cells lining the acini or ducts, often resulting in the obliteration of their lumen. Epithelial hyperplasia is classified as being either of usual type or atypical.

Usual-type epithelial hyperplasia (mild, moderate, florid)

In this type, the proliferating epithelial cells show no atypical features. Epithelial hyperplasia is considered mild if the epithelium is three to four cell layers thick, moderate if the epithelium is more than five layers thick, and florid if the lumina are nearly or completely filled by epithelium.

Atypical hyperplasia

In this type, the epithelial proliferations display various degrees of cellular and architectural atypia. There are two subtypes:

• atypical ductal hyperplasia

• atypical lobular hyperplasia.

Benign breast tumours

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign tumour of the breast. The tumours are composed of both glandular and stromal tissue. These benign neoplasms can occur at any age, but they are most commonly seen in women under 35years of age. Fibroadenomas are usually solitary, although in some women they may be multiple and bilateral. In younger women they present as palpable lumps (often freely mobile), and in older women they may present as mammographic densities. They can therefore mimic carcinoma clinically.

Pathology

Fibroadenomas grow within the breast as sharply circumscribed soft to firm nodules, and are usually easily enucleated at surgery. They vary in size from less than 1cm to around 4cm in diameter, although rarely they can reach up to 15cm in diameter (juvenile fibroadenoma/giant fibroadenoma – see below). The cut surface is grey-white and sometimes glistening, and contains slit-like spaces. In older women, fibroadenomas can become calcified. Histologically, these tumours are well-circumscribed nodules consisting of loose cellular stroma associated with breast ducts that, in longitudinal section, appear as compressed and elongated clefts.

The vast majority of fibroadenomas are benign. However, those containing cysts, sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcification or papillary apocrine change (so-called complex fibroadenomas) are associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Juvenile fibroadenoma / giant fibroadenoma

These terms are interchangeable and are used to refer to a reasonably distinct type of fibroadenoma that tends to occur in adolescents (often black girls) and reaches a large size (over 10cm in diameter). Histologically, they also tend to be rather hypercellular, but cellular atypia is not a feature.

Duct papillomas

Duct papillomas are uncommon and are usually seen in middle-aged women. They appear as outgrowths projecting into the duct lumen and consist of a fibrovascular core covered by benign breast duct epithelium. There are two types of duct papilloma:

• Large duct papillomas – these arise within the large central breast ducts and are usually solitary. Presentation is usually with a bloodstained nipple discharge, although some present as palpable lumps or mammographic densities. They are associated with an increased risk of developing carcinoma.

• Small duct papillomas – these arise in the smaller peripheral ducts, are often asymptomatic, and may be multiple. Multiple small duct papillomas are seen in younger patients, and are associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Adenomas

Adenomas of the breast are rare. There are three main subtypes:

• Tubular adenomas – these are sharply circumscribed nodules composed of closely packed ductal structures with little intervening stroma.

• Lactating adenomas – these are adenomas that arise during pregnancy and lactation.

• Nipple adenomas – these present as nodules just under the nipple. Microscopically, they consist of proliferating ductal structures and show a variety of growth patterns. The overlying skin may become ulcerated, mimicking Paget’s disease of the nipple (see below).

Benign connective tissue tumours

Risk of invasive breast carcinoma in women with benign breast disease

Several large case–control studies have now clarified the association between benign breast abnormalities and breast cancer risk.

There is no increased risk in the presence of:

• mastitis

• duct ectasia

• ordinary cysts

• apocrine metaplasia

• adenosis

• fibrosis

• mild usual-type epithelial hyperplasia without atypia

• fibroadenoma without complex features.

There is slightly increased risk (1.5–3 times) in the presence of:

• moderate or florid usual-type epithelial hyperplasia without atypia

• radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions

• fibroadenoma with complex features

• duct papilloma.

There is moderately increased risk (4–5 times) in the presence of:

• atypical ductal hyperplasia

• atypical lobular hyperplasia.

A family history of breast cancer increases the risk in all categories.

Some researchers have advocated a new classification system for benign breast disease that reflects the above observations. Three main categories of disease are defined in this system:

• non-proliferative diseases – this category includes the entities that are associated with no increased risk of developing breast cancer

• proliferative diseases without atypia – this category includes entities that are associated with a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer

• proliferative diseases with atypia – this category includes atypical hyperplasia.

20.3. Breast cancer

Breast cancer is a major cause of cancer morbidity. One woman in eight will develop breast cancer in her lifetime and, of these, a third will die from the disease.

Risk factors

The cause of breast cancer is still uncertain, but a number of factors that increase the risk of developing breast cancer have been identified.

Genetic predisposition

It has long been known that there is a familial aggregation of breast cancer, and at least four genes that convey increasing susceptibility to breast cancer have been identified. These are:

• BRCA1

• BRCA2

• p53

• ATM gene (responsible for ataxia telangiectasia).

Genetic predisposition is responsible for only 5–10% of breast cancer cases.

Age

Breast cancer is uncommon before the age of 25years, but the incidence increases steeply with age, doubling about every 10years until the menopause. The rise slows in the postmenopausal period.

Factors related to menses

Early age at menarche and late age at menopause are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. These findings indicate that hormones may have an important role in the development of carcinoma of the breast.

Factors related to pregnancy

An early age at first pregnancy is associated with a decreased risk of developing breast cancer.

Demographic influences

The incidence of breast cancer in Western countries is around five times higher than that in Far Eastern countries. Also, the rate of breast cancer is higher in women of high socioeconomic status. These differences are thought to be related to differing reproductive patterns, such as age at first birth, age at menarche and age at menopause.

Radiation

Exposure to ionising radiation increases the risk of breast cancer. The greatest risk has been found among women exposed to radiation around the menarche.

Benign breast disease

The risk of breast cancer varies according to the type of benign breast disease (see above).

Previous breast cancer

Women with breast cancer have an increased risk of developing a new primary lesion in the contralateral breast or the conserved ipsilateral breast.

Dubious risk factors

The role of obesity, diet and alcohol as risk factors for the development of breast cancer remains controversial and unresolved.

Distribution

Most cancers (50%) arise in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, 10% occur in each of the remaining three quadrants, and 20% occur in the central or subareolar region. Bilaterality of breast cancer occurs in 4% of cases.

Classification

Nearly all breast cancers are adenocarcinomas. Breast cancer is traditionally divided into non-invasive (in situ) carcinoma and invasive carcinoma.

Non-invasive (in situ) carcinoma

This term is used to refer to the situation where the malignant cells are confined to the ducts or acini, with no evidence of invasion by the tumour cells through the basement membrane and into the breast stroma. Women with these lesions have a markedly increased risk (8–10 times) of developing breast cancer. There are two types of non-invasive carcinoma:

• ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Ductal carcinoma in situ

In this type of non-invasive carcinoma, the breast ducts contain a malignant population of cells. DCIS is usually unilateral. Presentation can be as a nipple discharge or Paget’s disease of the nipple (see later), although DCIS may present as mammographic densities because the involved ducts often contain calcifications. Around half of all mammographically detected cancers subsequently turn out to be DCIS.

Pathology Histologically, DCIS can be divided into five architectural subtypes:

• Comedocarcinoma – characterised by the presence of solid sheets of high-grade malignant cells within the ducts with central necrosis. The necrosis commonly calcifies and this calcification is detected on mammography.

• Solid – denotes the presence of solid sheets of malignant cells within the ducts.

• Cribriform – this type is characterised by numerous gland-like structures within the sheets of malignant cells within ducts.

• Papillary.

• Micropapillary.

Classification of DCIS for patient management is usually based on the degree of cytological atypia. DCIS is graded by the pathologist as low, intermediate or high grade.

Risk of subsequent invasive cancer Evidence now indicates that many cases of low grade DCIS and most cases of high grade DCIS may progress to invasive carcinoma.

Lobular carcinoma in situ

In this type of non-invasive carcinoma, the malignant cells are found in the acini, although the changes seen may extend into the ducts. LCIS is often multifocal within one breast and frequently bilateral. The lesions do not present as palpable lumps and calcifications rarely occur, which means that they are rarely detected by mammography. Hence, the lesions are usually identified incidentally in biopsies for other breast abnormalities.

Risk of subsequent invasive cancer

Around a quarter to a third of women with LCIS go on to develop invasive carcinoma, but unlike DCIS, both breasts are equally at risk irrespective of which side the LCIS was originally identified.

Invasive carcinoma

With invasive carcinoma, the malignant cells have breached the basement membrane of the ducts or acini, and have spread into the surrounding stromal tissue.

Classification

Invasive breast carcinoma is classified according to overall histological appearance. The various histological subtypes are listed below:

• infiltrating ductal carcinoma (85%)

• infiltrating lobular carcinoma (10%)

• mucinous carcinoma (2%)

• tubular carcinoma (2%)

• medullary carcinoma (<1%)

• papillary carcinoma (<1%)

• others, e.g. apocrine carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumours, adenoid cystic carcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma (<1%).

Invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type (NST) Carcinomas that cannot be classified as any other subtype are designated invasive ductal carcinoma NST. Most breast carcinomas fall into this category. Macroscopically, these tumours appear as hard grey-white nodules (scirrhous carcinoma) imparted by their densely fibrous stroma. Histologically, the stroma is infiltrated by malignant cells that can be arranged in cords, nests, tubules or irregular masses – ductal carcinomas do not display any distinctive morphological features.

Invasive lobular carcinoma These tumours can have a scirrhous macroscopic appearance, but they are often softer and have an ill-defined infiltrating outline. Histologically, linear cords of malignant cells infiltrate a densely fibrous stroma. This linear arrangement of cells is often referred to as an ‘Indian file’ pattern. Carcinoma cells often form concentric rings around ducts. Signet-ring cells are common. It is important to distinguish lobular carcinoma from other types of carcinoma for the following reasons:

• invasive lobular carcinomas tend to be multicentric within the same breast

• these tumours metastasise more frequently to serosal surfaces, bone marrow, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the uterus and ovaries compared to other subtypes.

Mucinous carcinoma These tumours typically arise in older women and grow slowly over a number of years. Macroscopically, mucinous carcinomas have a soft, grey, gelatinous cut surface and are well-circumscribed. Histologically, the tumour is composed of small nests and cords of tumour cells lying in lakes of mucin. Because of the absence of densely fibrous stroma, and the fact that this type of carcinoma does not cause skin tethering or nipple retraction, mucinous carcinomas can be mistaken for benign breast lesions clinically. The prognosis for women with this type of breast cancer is better than that for invasive ductal or lobular carcinoma.

Tubular carcinoma These tumours tend to be small (<1cm in diameter) and are usually detected by mammography. Affected women are younger on average. Macroscopically, tubular carcinomas are small, firm, gritty tumours with irregular outlines. Histologically, they are composed of well-formed tubules in a desmoplastic stroma. The tubules lack a myoepithelial layer, a feature that distinguishes these malignant tumours from benign breast lesions. The prognosis for patients with tubular carcinoma is excellent.

Medullary carcinoma Macroscopically, these tumours tend to have a soft, fleshy consistency and are typically well-circumscribed. Histologically, medullary carcinomas are characterised by syncytial (fused) masses of large cells with pleomorphic nuclei, numerous mitotic figures, a conspicuous lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate, and a pushing (non-infiltrating) border. Gland formation is not seen. Despite the aggressive cytological features of the tumour cells, the prognosis for patients with this type of breast cancer is significantly better than that for many of the other subtypes.

Papillary carcinoma These tumours are rare. Microscopically, they show a papillary architecture. The prognosis is better than that of invasive ductal carcinoma.

Paget’s disease of the nipple

This condition presents as roughening and reddening of the skin of the nipple and areola, the appearances resembling eczema. Ulceration may occur. The condition is important to recognise because it is associated with underlying in situ or invasive carcinoma of the breast. Histologically, the epidermis is infiltrated by malignant cells.

Spread of breast carcinomas

Breast carcinomas can infiltrate locally or spread via the lymphatics or bloodstream to distant sites.

Direct spread

Breast carcinomas spread locally in all directions, becoming adherent to the underlying muscle fascia of the breast or tethered to the overlying skin. The latter manifests by dimpling of the skin and nipple retraction.

Spread via lymphatics

Involvement of the breast lymphatics by carcinoma causes blockage of the lymphatic drainage with consequent lymphoedema and thickening of the overlying skin, an appearance referred to clinically as peau d’orange. Several groups of lymph nodes drain lymph from the breast, but the axillary lymph nodes are the commonest initial site of lymph node metastases. Around a third of women with breast cancer will have lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Spread via the bloodstream

Once the malignant cells have developed the ability to enter the bloodstream, they can reach virtually any organ in the body, but the most frequently affected sites are the lungs, bones, liver, adrenals and brain.

Staging of breast cancer

Two main systems are used to stage breast cancer. These are the International Classification of Staging of Breast Cancer, and the TNM (tumour, node, metastasis) system. The management of the patient will depend on the stage of the disease (Table 36).

| Stage | Extent of spread |

|---|---|

| International Classification of Staging of Breast Cancer(ICSBC) | |

| I | Lump with slight tethering to skin, but node negative |

| II | Lump with lymph node metastases or skin tethering |

| III | Tumour that is extensively adherent to the skin and/or underlying muscles, or ulcerating or lymph nodes are fixed |

| IV | Distant metastases |

| Tumour, Node, Metastases (TNM) classification | |

| T1 | Tumour 20mm or less, no fixation or nipple retraction Includes Paget’s disease |

| T2 | Tumour 20–50mm, or less than20 mm but with tethering |

| T3 | Tumour greater than 50mm but less than 100mm; or less than 50mm but with infiltration, ulceration or fixation |

| T4 | Any tumour with ulceration or infiltration wide of it, or chest wall fixation, or greater than 100mm indiameter |

| N0 | Node-negative |

| N1 | Axillary nodes mobile |

| N2 | Axillary nodes fixed |

| N3 | Supraclavicular nodes or oedema of arm |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Prognostic factors

A number of factors influence the prognosis of breast cancer.

Axillary lymph node status

Tumour size

Small tumours are associated with a more favourable prognosis.

Histological grade

Many studies have shown the value of histological grade in predicting survival in breast cancer, low-grade cancers being associated with a more favourable prognosis.

Histological subtype

Certain types of breast carcinoma have a better prognosis than others, although the significance is less important than histological grade. Tubular carcinoma (and probably mucinous, medullary and papillary carcinoma) have a more favourable prognosis than invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type.

Oestrogen and progesterone receptors

Women with oestrogen receptor-positive (ER+ve), node-negative breast cancer have a better prognosis than those who have oestrogen receptor-negative (ER−ve) tumours. This is probably because tumours that express oestrogen receptors respond well to hormonal manipulation. The progesterone receptor status of a tumour is less important than the oestrogen receptor status, but it may have a small effect on the overall responsiveness of a tumour to hormonal manipulation in that women with ER+ve tumours which are also progesterone receptor positive (PR+ve) have a slightly increased chance of benefiting while those with tumours that are ER+ve and PR−ve have a slightly decreased chance of benefiting. Tumours that are both ER−ve and PR−ve are less likely to respond to hormonal manipulation than tumours which are ER−ve and PR+ve.

Other molecular markers (including HER2)

It has been proposed that tumour differentiation, invasion, metastasis, and growth can be inferred by measuring certain cellular markers, e.g. expression of growth factor receptors, proteinases, cell-adhesion molecules, and other products of oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes. Much of the research in this field has focused on the oncogene HER2 (also known a HER2/NEU and c-ERB-B2), the protein product of which is a cell-surface growth factor receptor. Research using molecular techniques indicates that 1 in 4 breast carcinomas show amplification of the HER2 gene and such cancers are referred to as ‘HER2-positive’. Studies have shown that HER2-positive cancers have a poorer prognosis, shorter survival, shorter relapse time, tend to be more aggressive and respond poorly to conventional therapies. However, it has now been possible to develop a treatment strategy that employs the use of a monoclonal antibody called trastuzumab (Herceptin), which can block the HER2 receptor and hence reduce tumour growth. Evidence indicates that administration of this antibody to women with HER2-positive breast cancers may significantly improve survival.

Other malignant breast conditions

Phyllodes tumour

Like fibroadenomas, phyllodes tumours are composed of both glandular and stromal tissue, are usually solitary, and can present as palpable lumps or mammographic densities. They can occur at any age but the median age at presentation is 45years, some 10–20years later than that for fibroadenomas. Phyllodes tumours can only be differentiated from fibroadenomas by their microscopic appearance.

Pathology

Phyllodes tumours vary greatly in size, and they have been reported to reach up to 450mm in diameter. They often grow as lobulated masses within the breast tissue. Microscopically, phyllodes tumours can be differentiated from fibroadenomas by the presence of stromal cellularity, mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism. Most are low-grade tumours, when the major problem is local recurrence. Rare high-grade tumours can behave aggressively, metastasising via the bloodstream.

Sarcomas

Sarcomas such as angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma are all rare.

Lymphomas

Lymphomas in the breast may be primary, but are more usually secondary to disease elsewhere in the body.

Secondary tumours

Secondary tumours to the breast are rare. Those most commonly encountered are metastases from the lung, the contralateral breast and malignant melanoma.

20.4. Diagnosis of breast lesions

When a breast lesion is suspected on clinical grounds (history and physical examination) or detected by mammography, a number of investigation methods can be used to gain further information about the lesion and lead to a diagnosis. These are:

• ultrasonography

• fine-needle aspiration cytology

• core biopsy

• excision biopsy.

Often, a combination of modalities is used. The value of these methods is that benign and malignant conditions may be diagnosed without the need for removal of the breast (mastectomy). In malignant cases, prognostic information may also be provided (e.g. oestrogen receptor status). Appropriate management plans can then be formulated.

20.5. The male breast

Structure

It is not necessary for the male breast to have secretory capability. Hence, it consists of ductular structures surrounded by a small amount of supporting connective tissue, but there are no acini.

Two main conditions can affect the male breast:

• gynaecomastia

• carcinoma.

Gynaecomastia

This benign condition is defined as enlargement of the male breast due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of both ductal and stromal elements. Most cases are unilateral, but around 25% of patients show bilateral involvement.

Aetiology

Gynaecomastia is thought to occur as a result of an imbalance between oestrogens (which stimulate the breast) and androgens. The condition can occur as a normal phenomenon in adolescents and very elderly men, but it can also occur in the following situations:

• drug-induced (most common cause):

• oestrogens (in the treatment of prostate cancer)

• digitalis

• cimetidine

• spironolactone

• conditions causing high oestrogen levels:

• tumours of the adrenal glands

• tumours of the testis

• chronic liver disease

• syndromes of androgen deficiency, e.g. Klinefelter’s syndrome

• other endocrine disorders:

• hyperthyroidism

• pituitary disorders.

Carcinoma

In situ and invasive carcinoma of the male breast is very rare, accounting for only 1% of all breast cancers. Risk factors (except those functionally confined to women), presentation, spread, histological subtypes and prognostic factors are similar to those seen in women. With regard to prognosis, evidence suggests that when male and female breast cancers are matched for grade and stage, the overall prognosis for men and women is the same. However, men often present at more advanced stages than women.

Self-assessment: questions

One best answer questions

2. A 52-year-old smoker presents to her GP with a mass in the left breast. The subsequent ultrasound, fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy confirmed that this was an invasive carcinoma. The hormone receptor status of the tumour was determined on the core biopsy. The patient was given hormone therapy and underwent excision of the breast lesion and the axillary lymph nodes. Six months later, she saw her GP because she was feeling generally unwell and had been experiencing some pain in her left chest. An X-ray showed a lytic lesion in one of the ribs on the left side and a left pleural effusion. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. bronchopneumonia

b. pulmonary thromboembolism

c. metastatic carcinoma of the breast

d. bronchogenic carcinoma

e. osteosarcoma

True-false questions

1. The following statements are correct:

a. acute mastitis is most frequently seen in the early weeks of breastfeeding

b. mammary duct ectasia may present with a breast mass and nipple discharge

c. early age at first pregnancy increases the risk of developing breast cancer

d. breast cancer is more frequent in multiparous women than nulliparous women

e. men never develop breast cancer

2. The following breast conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer:

a. apocrine metaplasia

b. atypical hyperplasia

c. radial scar

d. duct papilloma

e. complex fibroadenoma

3. The following statements are true:

a. most breast cancers arise in the upper outer quadrant of the breast

b. in situ carcinoma usually presents as a breast mass

c. lobular carcinoma in situ is frequently multifocal and bilateral

d. tumour size is the most important prognostic indicator in women with breast cancer

e. carcinomas that are oestrogen receptor positive have a poorer prognosis than those that are oestrogen receptor negative

4. Invasive breast cancer:

a. can be genetically inherited

b. always presents as a breast mass

c. most commonly metastasises to the mediastinal lymph nodes

d. may be associated with Paget’s disease of the nipple

e. is most frequently of ductal type histologically

5. The following can be associated with breast cancer:

a. axillary mass

b. nipple inversion

c. roughening and reddening of the skin of the nipple

d. bone fracture

e. pleural effusion

6. The following conditions can present with a discrete breast mass

a. fat necrosis

b. fibrocystic change

c. fibroadenoma

d. gynaecomastia

e. breast cancer

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 29-year-old women presents to her GP with a lump in the right breast.

1. What is the differential diagnosis?

2. Which of these diagnoses do you think are least likely in this case, and why?

3. What further information would you seek in the history and examination in order to help determine the diagnosis?

Case history 2

1. What is the most likely diagnosis?

2. Describe the pathological basis of each of the examination findings?

3. What further tests might you perform?

Short note questions

Write short notes on:

1. The diagnosis of breast cancer.

2. The association between benign breast abnormalities and breast cancer risk.

3. Risk factors for the development of breast cancer.

Viva questions

1. What conditions may affect the male breast?

2. What is the rationale behind mammographic breast screening?

3. What factors influence the prognosis of women with breast cancer?

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

2. c. Metastatic carcinoma of the breast. The most likely diagnosis is metastatic carcinoma of the breast. The lytic lesion in the rib most likely represents a metastatic tumour deposit, and the pleural effusion is probably due to involvement of the pleura, either by direct spread through the chest wall or indirect spread to the lung and pleura. Bronchogenic carcinoma is a distinct possibility, but given the recent history of breast cancer this is the more likely diagnosis. The diagnosis could be confirmed by performing a diagnostic aspiration of the pleural fluid. The fluid can be examined under the microscope for the presence of malignant cells, and it may be possible to determine whether these are likely to have originated from a breast or lung primary site. Bronchopneumonia and pulmonary thromboembolism are possibilities, but the lytic lesion in the rib does not fit for these. Osteosarcomas are rare and are usually seen in younger people. Remember that metastatic carcinoma is by far the most common malignant tumour in bone.

True-false answers

1.

a. True.

b. True.

c. False. This is associated with a decreased risk.

d. False. Breast cancer is more frequent in nulliparous than multiparous women.

e. False.

2.

a. False.

b. True.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True. But fibroadenomas that do not showcomplex features are not associated with anincreased risk

3.

a. True.

b. False.

c. True.

d. False. Lymph node status is the most important prognostic factor.

e. False. Oestrogen receptor positive tumours have a better prognosis

4.

a. True. Five to ten per cent of breast cancers aredue to inheritance of an autosomal dominant gene. The genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for most of these cases.

b. False.

c. False. Breast tumours most commonly metastasise to the axillary lymph nodes.

d. True.

e. True.

5.

a. True. This may indicate lymph node metastasis

b. True.

c. True. This may represent Paget’s disease of the nipple.

d. True. This may represent a pathological fracture due to bony metastasis.

e. True. Due to spread of the tumour to the pleura.

5.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. Comment: It is important to realise that the differential diagnosis for a lump in the breast includes almost the entire spectrum of breast disorders. Inflammatory lesions, fibrocystic disease, benign tumours and malignant tumours (principally invasive carcinoma) may all present as breast lumps. Remember that in situ carcinoma does not present as a breast lump (unless it is associated with another breast lesion).

2. Comment: Taking note of the patient’s age is often helpful in determining which of the differential diagnoses are more likely and which are less likely. In this case, the patient is 29years old. Carcinoma is therefore the least likely diagnosis, although young patients may develop breast cancer, especially if there is a strong family history.

Case history 2

1. The fact that this woman first felt the breast lump after she sustained an injury to the breast raises the possibility of fat necrosis. However, the clinical findings of a retracted nipple, peau d’orange, a firm immobile mass, and enlarged axillary lymph nodes are all highly suggestive of breast cancer. The preceding trauma may simply have drawn the patient’s attention to her breast, and in the ensuing self-examination the lump would have been revealed.

2. Most of the features on physical examination can be explained in terms of the way that breast cancer spreads. Extension into the overlying skin causes retraction and dimpling, and tumours that have become adherent to the deep fascia of the chest wall become fixed in position (immobile). Involvement of the lymphatic channels around the tumour blocks drainage of the overlying skin, causing localised lymphoedema and skin thickening, referred to as peau d’orange. The axillary lymph nodes become enlarged and firm when there are lymph node metastases.

3. Initial further investigations are directed towards establishing a diagnosis of cancer. Several techniques may be employed, but a combination of different modalities is often necessary to make the diagnosis. These include ultrasonography, fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNA), core biopsy and, if necessary, excision biopsy. Further investigations, e.g. computed tomography (CT) scan, are usually aimed at determining the stage of the disease.

Short note answers

1. Whenever you are asked how you might diagnose any condition, your answer must always include the three most important tools, namely: history; physical examination; and further investigations (or tests). Focus on the most important features that you would want to elicit from the history and examination, i.e. family history, the appearance of the affected breast, the nature of any breast mass and the axillary contents, and the nature of any nipple discharge. Then discuss the further tests that you might use to establish the diagnosis, i.e. ultrasonography, FNA, core biopsy and excision biopsy. Remember that some breast cancers are detected by mammography in the National Breast Screening Programme.

2. What is wanted here is an awareness that there are certain benign breast conditions that are associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions, moderate to florid usual-type epithelial hyperplasia, fibroadenomas with complex features, and duct papillomas are all associated with a slightly increased risk, while atypical hyperplasia is associated with a moderately increased risk.

3. Risk factors for breast cancer include genetic predisposition, age, factors related to the menses and pregnancy, demographic influences, radiation, certain benign breast diseases and previous breast cancer.

Viva answers

1. The two main intrinsic breast conditions that may affect the male breast are gynaecomastia and carcinoma. Try to give an account of the various causes of gynaecomastia. Carcinoma of the male breast is uncommon. However, when it occurs it usually presents at a higher stage and therefore generally has a poorer prognosis. Remember that the male breast may also be affected by pathology of the skin and soft tissue (as may the female breast).

2. Screening implies performing a test in order to detect a particular disease (most commonly cancer) in an asymptomatic but at-risk population. With cancer, the idea is to detect the disease either at its pre-invasive stage, when treatment of the lesion would prevent cancer from developing, or at a stage when the cancer is small and therefore potentially curable. With breast cancer, there is a pre-invasive stage (in situ carcinoma) and small invasive tumours do have a better prognosis. Both in situ and invasive carcinoma can be detected on mammography because they induce densities, calcifications and areas of architectural distortion that can be visualised. Mammography is both sensitive and specific, but it is also acceptable, and it is, therefore, the principal investigative modality in the National Breast Screening Programme.

3. Several factors influence the prognosis of breast cancer. These include lymph node status, tumour size, histological grade, histological subtype and oestrogen receptor status.