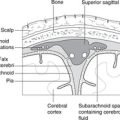

Anatomy is a visual subject: ideally, you need to see, touch and feel to get an idea of three dimensions. When you read a portion of text you should try to picture the structures concerned: dissected parts and a good anatomical atlas, whether on paper or computer, will help.

Different people study differently, and some find an understanding of three dimensions easier to come by than do others. Nevertheless, as a basis for study I recommend that you use the nervous system and the main arteries, together with the following conceptual framework, common to all living things:

• we reproduce

• we seek sustenance

• we absorb and distribute nutrients

• we excrete waste products

• we try to prolong our own existence; and

• we endeavour to control these processes.

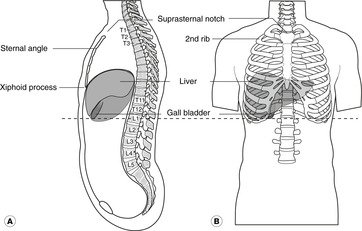

Surface markings and vertebral levels

The surface projection of internal organs is important since it forms the basis of the clinical examination of a patient. When you read about any structure, the heart for example, you should try to picture the body and relate the printed word to a precise location. Better still, get a friend to be a surface anatomy model (it is no good looking at yourself in a mirror because right and left are the wrong way round).

The horizontal level of a structure in the body is described by reference to the vertebra(e) at the same level – that is to say in the same transverse plane. This is known as ‘the vertebral level’. Both surface markings and vertebral levels are important and useful in the clinical context.

Study Figure 1.1 and note that:

• the suprasternal notch is at vertebral level T2

• the sternal angle is at vertebral level T4

• the xiphoid process is at vertebral level T9 (about)

• the surface marking of the gall bladder is the tip of the right ninth costal cartilage (at the anterior end of the ninth rib). Its vertebral level is L1.

Regional anatomy and systematic anatomy

The cardiovascular and nervous systems are found in all parts of the body. The respiratory system is in the head, neck and thorax. The alimentary system is in the head, neck, thorax, abdomen and perineum. To study anatomy by systems is relevant to the particular system, but wasteful since it means that, for example, different parts of the thorax must be studied on different occasions for several systems. Study by systems also fails to give an appreciation of the fact that disease knows no boundaries: a bronchial carcinoma may cause symptoms in more than one system because the carcinoma may involve adjacent structures. Both approaches, systematic and regional, are important and after a superficial survey of the anatomically important systems, a regional approach is used in this book.

Prenatal development

Knowledge of prenatal development is necessary to understand how congenital anomalies arise, and it helps in appreciating why the structures of the body are as they are. Development itself is a consequence of history – the succession of living things – and of the demands of the embryo for nutrition and survival. This is not a textbook of embryology, or of anthropology or evolution, but occasional references to these topics will be made where it seems helpful.

Variation

You should bear in mind when you are studying anatomy or examining a patient that variations are found, and in some organs and systems, for example superficial veins, variations are common. Nevertheless, there are ‘averages’ and it is these, given in this book, that you should be familiar with.

Eponyms

Angle of Louis, foramen of Winslow, Hirschsprung’s disease – who are these people? Why do we continue to use their names? Such eponyms are commonly used in medicine despite the best efforts of grey men and women to abolish them. They remind us of history and of personalities and they are sometimes easier to pronounce than the proper names. In this book I use the more commonly occurring eponyms, and give the proper names with them. You will hear eponyms used by others sooner or later, so you might as well start now. Some examiners may ask you who such-and-such was (though they shouldn’t). If you don’t know, simply say ‘a nineteenth century Dublin doctor.’ You’d be surprised how many were, and I doubt that the examiner would be sure enough to challenge you even if you are bluffing.