Vertebrae25

5.2 Intervertebral discs25

5.3 Typical vertebra26

5.4 Regional variations in vertebrae26

5.5 Joints, ligaments and movements27

5.6 Arteries and veins of the vertebral column28

The vertebral column provides support. Flexibility is provided by its arrangement into individual vertebrae: 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar and 5 fused to form the sacrum. Vertebrae are separated by intervertebral discs. Ligaments pass between equivalent parts of adjacent vertebrae to form a ligamentous and bony tube containing the spinal cord. Movements of the column are constrained by the anatomy of individual regions of the column and the rib cage. The venous plexuses around the column and inside the vertebral canal are important in the spread of disease, particularly from the lower abdomen and pelvis.

You should:

• list the bones that make up the vertebral column

• describe how the characteristics of vertebrae of the four main regions reflect function

• describe the function and disposition of intervertebral discs

• describe the main movements of the column and the muscles that produce them

• describe how the column is supplied with blood, and how its veins are important in the spread of disease.

5.1. Vertebrae

The vertebral column confers rigidity on the trunk: it is an adaptation to deal with gravity. A solid, rigid column would confer maximum rigidity, but then movement would be virtually impossible, so the column is broken up into individual vertebrae as follows:

• 7 cervical

• 12 thoracic (sometimes called dorsal, but this is misleading since they are no more dorsal than the others)

• 5 lumbar

• 5 sacral, fused into one bone, the sacrum

• a few coccygeal, which are very small and may be fused; forget about them.

5.2. Intervertebral discs

Intervertebral discs are found between all vertebrae from C2 to S1. They consist of:

• an annulus fibrosus: tough hyaline cartilaginous rim, and

• a nucleus pulposus: fibrocartilaginous core, softer, probably derived from remnants of the notochord.

Rupture of the annulus fibrosus may allow the softer nucleus pulposus to herniate and this may compress the spinal cord or segmental nerve roots in the spinal (vertebral) canal of the vertebral column. This is often somewhat inaccurately referred to as a slipped disc. The symptoms of this condition will depend upon at which level it occurs and which structures are affected. The herniation usually occurs to one side or the other, compressing nerve roots that leave the spinal (vertebral) canal below the site of herniation. If the herniation occurs in the midline, then the centrally situated nerve roots of the cauda equina may be affected, causing cauda equina syndrome. See Ch. 6, p. 31; Ch. 11, p. 151).

There is no disc between the base of the skull and vertebra C1 or between vertebrae C1 and C2; this is because of the specialised movements which take place here (see Ch. 14, p. 243).

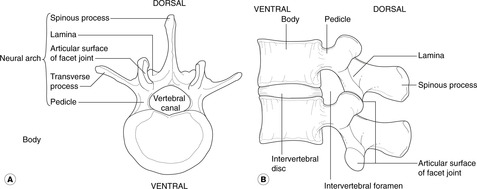

5.3. Typical vertebra (Fig. 5.1)

5.4. Regional variations in vertebrae

Cervical vertebrae have:

• a triangular vertebral canal

• a foramen in each transverse process for arteries and veins

• a bifid (two-pronged) spinous process (except C1, C7).

The atlas and axis (C1, C2) are specialised for movement: see Chapter 14.

Thoracic vertebrae have:

• facets for rib articulations

• a spinous process orientated in a marked inferior direction.

Lumbar vertebrae are identifiable by their large size.

Sacral vertebrae are fused to form the sacrum.

Junctional zones

Vertebra C7 has some features (for example the non-bifid spinous process) of a thoracic vertebra. Vertebra T12 has some features, notably the bulk, of a lumbar vertebra.

Fusion of vertebra L5 to the sacrum, giving a six-segment sacrum, is known as sacralisation of L5. Separation of vertebra S1 from the sacrum, leaving a four-segment sacrum and six ‘lumbar’ vertebrae, is lumbarisation of S1. These two conditions will affect strength and mobility and a free S1 vertebra that is out of alignment may compress spinal nerve roots.

Surface anatomy

• C7. When you flex your neck and drop your chin onto your chest, the most prominent vertebral spinous process is that of C7 – the vertebra prominens. This is useful clinically should you want to determine a particular vertebral level.

• L3/4. A line joining the highest points of the right and left iliac crests intersects the midline at (usually) the L3/L4 junction. This is useful clinically since this level is the usual site for lumbar puncture (see Ch. 6, p. 40).

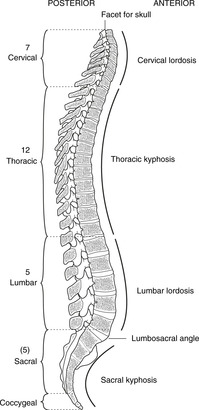

Spinal curvatures (Fig. 5.2)

A dorsal convexity is a kyphosis; a dorsal concavity is a lordosis; and a side-to-side bending is a scoliosis.

Before birth the entire vertebral column is kyphotic. After birth, with the demands of weightbearing and the effects of gravity, the cervical and lumbar regions become lordotic. The thoracic and sacral kyphoses are said to be primary curvatures (because they are present at birth); the cervical and lumbar lordoses are secondary curvatures (because they develop subsequently). Age changes in the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs result in increasing kyphosis as the years advance, more marked in some people than others.

Degrees of scoliosis vary with posture (postural scoliosis), although marked scoliotic deformities, most often developing in adolescent girls, require treatment.

5.5. Joints, ligaments and movements

Each vertebra articulates with the one above and the one below by means of:

• a midline cartilaginous joint – intervertebral disc

• two lateral synovial joints between transverse processes – one on each side. These are often called ‘facet’ joints.

The movements are flexion, extension and lateral flexion to both sides. All joints are involved in all these movements to some extent, and disease of the facet joints can be particularly troublesome because of the proximity of the joint to the segmental nerves passing through the intervertebral foramina. This can give rise to both back pain at the site of the injury or disease, and pain perceived in the skin and other structures served by the nerve affected (referred pain).

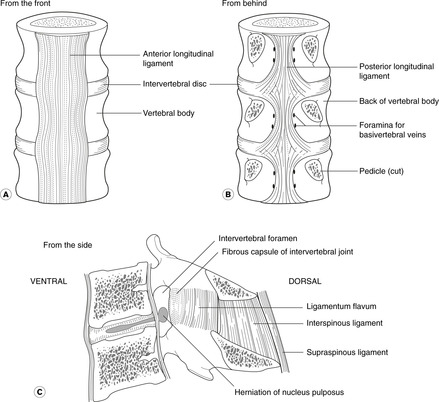

Ligaments of the vertebral column (Fig. 5.3)

• Anterior longitudinal ligament: connecting the anterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies.

• Posterior longitudinal ligament: on the anterior wall of the vertebral canal, connecting the posterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies. This narrows as it descends and is at its narrowest in the lumbar region, just where the spine bears most weight. In this region, therefore, with a combination of a heavy load and a narrow ligament, herniation of the intervertebral discs is most likely. Such herniations in a posterolateral direction may impinge on the nerve roots or on the spinal cord itself, depending upon the level, causing pain both locally and in the distribution of the nerve concerned.

• Ligamentum flavum: connecting adjacent laminae. This ligament is pierced by a needle (e.g. in lumbar puncture) inserted from behind.

• Articular ligaments. All synovial articulations between the ribs and the vertebral column, and all the synovial facet joints are surrounded by ligaments which may be injured.

• There are also ligaments joining adjacent vertebral spines (interspinous, supraspinous ligaments).

Muscles

Contraction of the muscles of the abdominal wall causes flexion and lateral flexion of the vertebral column. They are assisted by other muscles, depending upon posture, such as lower limb muscles (for example, psoas).

The large muscle bulk posterior and lateral to the vertebral column, between the vertebral spines and the rib cage, is sacrospinalis, sometimes, not strictly accurately, known as erector spinae muscles. They are the postvertebral muscles supplied by the posterior rami of all segmental nerves. You do not need to know the names or attachments of the muscles, but you should realise that they are responsible for maintaining our erect posture and are in constant use during locomotion and as we shift our weight during postural changes of all descriptions.

At the cranial end immediately below the skull, this group includes the suboccipital muscles supplied by the dorsal ramus of C1. These are responsible for movements at the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints. Again, you do not need to memorise them, merely know that they are there.

5.6. Arteries and veins of the vertebral column

Arteries

The vertebral column is surrounded by an arterial network with contributions from the vertebral artery in the neck and the intercostal and lumbar arteries in the trunk. Branches pass through the intervertebral foramina to supply the spinal meninges and cord, and small nutrient arteries supply the bones themselves.

Cartilage is generally held to have no blood vessels, and although a few arteries are found on the surface of intervertebral cartilaginous discs, they do not penetrate far. Because a good blood supply is necessary for the healing process, damaged discs do not heal.

External and internal vertebral venous plexuses

The external vertebral venous plexus surrounds the vertebral column. It has connections with the pelvic venous plexus, the lumbar veins and the azygos system.

The internal vertebral venous plexus is inside the vertebral canal. It anastomoses freely with the external plexus by veins passing through the intervertebral foramina. The internal vertebral venous plexus is in the extradural space and into this plexus drain:

• two or more short veins draining the vertebral body: the basivertebral veins

• veins draining the spinal cord.

These venous connections are important. Since these veins lack valves, blood flow can be in either direction, depending upon intra-abdominal pressure. Pelvic or abdominal malignancy may spread by these venous channels to give secondary deposits (metastases) in the vertebral bodies. These may present as backache, or, if the vertebral body collapses, as nerve entrapments or spinal cord compression. Prostatic malignancy is well known for spreading like this to involve the vertebral column and give rise to vertebral metastases.