CHAPTER 13 The foot

Anatomical Features

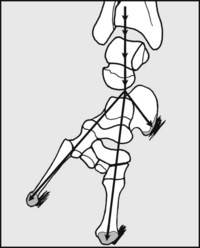

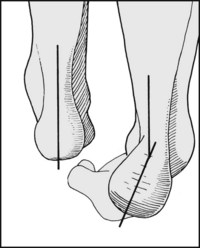

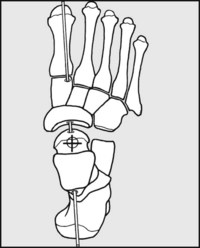

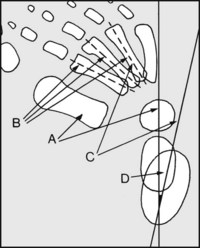

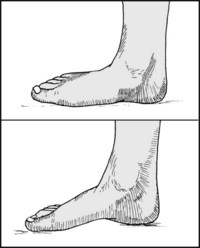

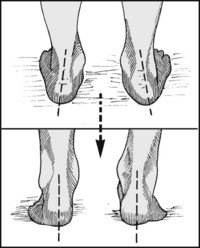

Fig. 13.A. Tripod action of the foot:

To maintain perfect ground contact each foot acts as a tripod, with the legs of the tripod being represented by the calcaneus and the heads of the first and fifth metatarsals. To maintain balance, the centre of gravity (in front of S2) must fall within the area covered by one or both feet, and to facilitate this each foot must be capable of movement in two planes.

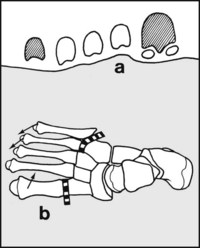

Fig. 13.B. Planes of movement (1):

In the x-axis nearly all of the movement occurs in the ankle, and this allows balance to be maintained when going up and down slopes. (Some very slight movement in the same plane occurs in the midtarsal and tarsometatarsal joints, and minimally in the subtalar joint.)

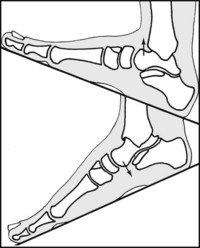

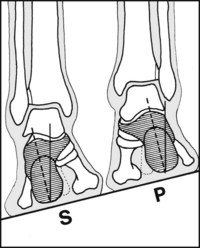

Fig. 13.C. Planes of movement (2):

In the z-axis supination (S) occurs when the soles of the feet are turned inwards to face one another; pronation (P) involves movement in the opposite direction. This allows the feet to adapt to a surface sloping at right angles to the direction of travel. The major part of this movement involves the subtalar joint (but the midtarsal and tarsometatarsal joints are also involved).

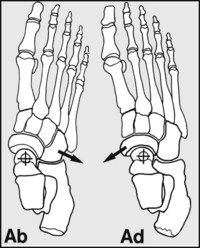

Fig. 13.D. Planes of movement (3):

In the y-axis, at right angles to the others, a very limited range of abduction and adduction of the forefoot may occur. Most of this occurs in the midtarsal joint, but some takes place in the tarsometatarsal joints and in the ankle. This is of relatively little importance, although a fixed metatarsus adductus is a well known, self-limiting deformity, generally of childhood.

Inversion of the heel occurs when the calcaneus tilts into varus. This movement occurs in the subtalar joint. As the heel tilts, it carries the rest of the foot with it (the foot is directly connected to the calcaneus through the calcaneocuboid joint), and this results in supination of the foot. (Valgus tilting of the heel (eversion) results in pronation of the foot.)

Fig. 13.F. Subtalar movements (1):

Movements in the subtalar joint, which involves two pairs of articular surfaces, are highly complex, the only joints they resemble being those between the radius and ulna. There is, however, a relatively fixed axis of movement which passes through the centre of the head of the talus in front, and through the posterolateral tubercle of the calcaneus behind.

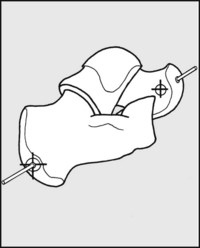

Fig. 13.G. Subtalar movements (2):

The complex pattern of calcaneal movements that occurs in inversion are sometimes compared with the three-plane movements of ships or aircraft: the calcaneus rolls (1), pitches (2) and yaws (turns) (3) under the talus.

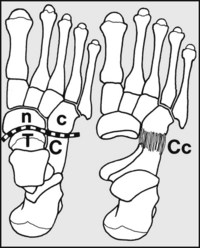

Fig. 13.H. The midtarsal joint (1):

This links the hindfoot with the midfoot. It is formed by the head of the talus (T) and the navicular (n) on the medial side, and on the lateral by the calcaneus (C) and the cuboid (c). The latter joint (Cc), which permits only a limited range of movements, ensures that when the heel moves the rest of the foot follows.

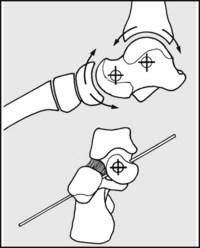

Fig. 13.I. The midtarsal joint (2):

The joint has in effect two axes of movement. First, it acts as a hinge, allowing slight dorsiflexion and plantarflexion (like the ankle). The axis of this hinge passes through the centre of the head of the talus, so that this movement is coordinated with subtalar movement (which passes through the same point). The plane of this axis is tilted at 45° relative to the horizontal.

Fig. 13.J. The midtarsal joint (3):

In addition to movements in (roughly) the x-axis, a limited amount of pronation and supination (z-axis) is possible; the navicular slides and rotates round the head of the talus, and the cuboid slides on the calcaneus. This axis of rotation also passes through the centre of the head of the talus.

Fig. 13.K. Tarsometatarsal movements:

(a) Whereas the heads of the first and fifth metatarsals form the anterior limbs of each foot tripod, the other metatarsal heads can adapt to any irregularity in the surface of the ground. Elevation and depression of the first metatarsal head and of the others (particularly the fourth and fifth (b)) can contribute an appreciable amount to overall supination of the foot (e.g. first tarsometatarsal movement amounts to 15°).

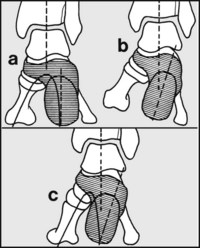

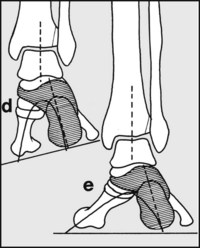

Normally, in the weightbearing foot the axis of the heel is in alignment with the tibia (a). If the heel posture is abnormal and tilts into varus, then under normal circumstances the foot would supinate and the first metatarsal head would not contact the ground (b). To correct this, the foot distal to the subtalar joint must pronate, and this leads to accentuation of the medial longitudinal arch (c).

If, on the other hand, the heel posture is one of valgus (d), then to allow all the metatarsal heads to contact level ground the foot distal to the subtalar joint must supinate, leading to flattening of the medial arch (e). The important practical points to note are that valgus heels are associated with flat foot, and varus heel with pes cavus

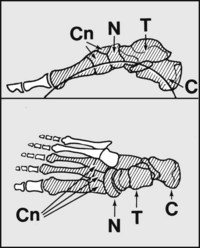

These are well known features of the foot. The medial longitudinal arch is the most important, and the one primarily affected in pes planus and pes cavus. It is formed by the calcaneus (C), talus (T), navicular (N), cuneiforms (Cn) and medial three metatarsals. Flattening of the arch is common and is assessed clinically, although weightbearing lateral radiographs may be helpful.

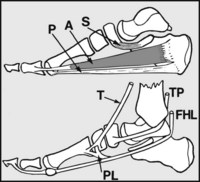

The medial arch is supported by the spring ligament (S), which shoulders the head of the talus; the plantar fascia (P), which acts as a tie; abductor hallucis (A) and flexor digitorum brevis, which act as spring ties; tibialis anterior (T), which lifts the centre of the arch (and, with peroneus longus (PL), forms a stirrup-like support for it); tibialis posterior (TP) which adducts the midtarsal joint and reinforces the action of the spring ligament; and flexor hallucis longus (FHL), which acts as a long spring tie and helps support the head of the talus.

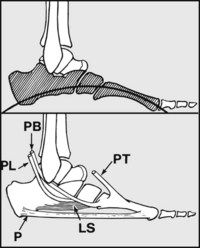

The lateral longitudinal arch is formed by the calcaneus, cuboid and fourth and fifth metatarsals; it is very shallow, and generally flattens out on weightbearing. It is supported by the long and short plantar ligaments (LS), the plantar fascia (P), flexor digitorum brevis, flexor and abductor digiti minimi (not shown), peroneus tertius (PT), peroneus brevis (PB) and peroneus longus (PL).

The transverse arch is formed by the cuneiforms (c) and cuboid (cu). It stretches across the sole in the coronal plane. It is in fact a half arch: the whole arch is completed by the other foot. It is of no particular clinical significance, as its presence and size are precisely related to those of the medial longitudinal arch. The shape of the cuneiforms (likened to the voussoirs of stone arches) helps maintain the arch.

The anterior arch lies in the coronal plane; its bony components comprise the metatarsal heads. It is not a feature of the weightbearing foot, as under load the metatarsal heads flatten out. The metatarsal heads are prevented from spreading out (splaying) by the intermetatarsal ligaments (IM) and the intrinsic muscles, especially the transverse head of adductor hallucis (AH).

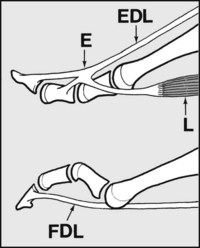

Extensor digitorum longus (EDL) extends the MP (metatarsophalangeal) and both IP (interphalangeal) joints of each toe. The interosseous and lumbrical muscles (L), through their attachment to the extensor expansions (E), extend the toes at the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, and flex the MP joints; if they become weak or fail, the unchecked pull of flexor digitorum longus (FDL) results in clawing of the toes.

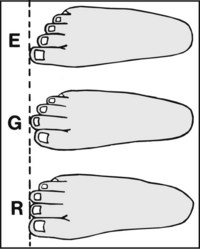

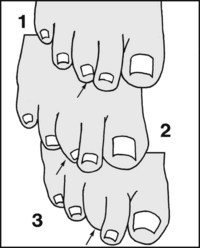

The relative length of the toes is subject to variations, many of which are regarded as normal. The commonest arrangement is the Egyptian foot (E), when the great toe is longest and the succeeding toes progressively shorter. In the so-called Greek foot (G), the second is the longest. In the rectangular or intermediate foot (R), the great and second toes (and often the third) are equal in length.

Conditions Commencing or Seen First in Childhood

Talipes Equinovarus (Club Foot)

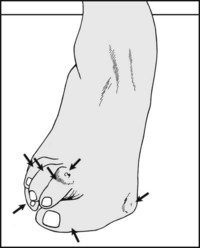

This is the commonest of the major congenital abnormalities affecting the foot, and may be detected before birth by ultrasonography. All newly born children should be examined to exclude this condition. It is commoner in boys than girls, and the aetiology is uncertain. The deformity is a complex one: characteristically there is a varus deformity of the heel and adduction of the forefoot, accompanied by some degree of plantarflexion and supination. MRI scans are regarded as being of value in determining talonavicular alignment and as a guide to management.

The best results are obtained with early, aggressive conservative treatment, and in particular the long-established Ponseti regimen has been shown to be particularly successful in the management of this potentially very disabling condition. It involves manipulative stretching of the tightened structures (in practice, gently stretching the foot into as near normal alignment as possible) and applying a cast from the toes to the groin. This is repeated every 5–7 days, to better each correction. Once full correction has been obtained, the child is given an abduction foot orthosis which is worn full time for 12 weeks – and then at night and nap times. (Possible percutaneous tenotomy of the tendocalcaneus and transfer of tibialis anterior are integral parts of the protocol.)

In some cases, especially when there is a delay in starting treatment or where there is a failure to respond, simple measures may not be enough. More radical treatments include division of the plantar fascia at the heel and procedures that stretch the soft tissues and influence bone growth, especially those using the Ilizarov method (this involves the insertion of wires through bony elements in the leg and foot, connecting them with a frame, and repeatedly adjusting their spacing and orientation).

In untreated cases the primary anomaly affecting the soft tissues is followed by alteration in tarsal bone growth. In such cases, wedge excision of bone and fusion of the midtarsal and subtalar joints may be required to obtain a plantigrade foot (Dunn’s arthrodesis, triple fusion).

When an incomplete correction has been obtained, the commonest residual deformities seen in the older child and adult are persistent adduction of the forefoot, shortening of the Achilles tendon and some stunting in overall growth of the foot.

Talipes Calcaneus

This is a much less common congenital abnormality of the foot, in which the dorsum of the child’s foot lies against the shin. There are frequently associated deformities of the subtalar and midtarsal joints, with the heel lying in the varus or valgus position (talipes calcaneovarus, talipes calcaneovalgus). This condition is also treated by stretching and splintage as soon as the diagnosis has been made.

Skew Foot

In this condition there is adduction of the metatarsals (metatarsus adductus) accompanied by a valgus deformity of the hindfoot. It may be seen as a residual deformity in cases of club foot where treatment has not been followed by complete resolution, or it may occur on its own. Many cases resolve spontaneously, but in some it persists, leading to callosities and foot pain. Treatment is usually by conservative measures, but surgery may be required in resistant cases.

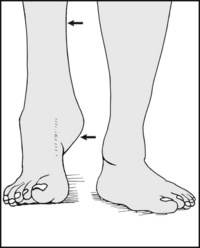

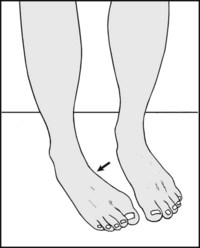

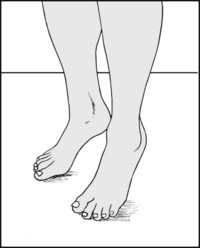

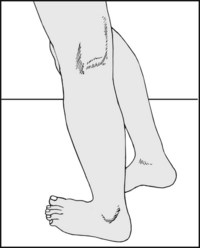

Intoeing

After walking has commenced, parents may seek advice because the child is walking with the feet turned inwards (intoeing, hen-toed gait). The feet may be internally rotated to such an extent that the child is constantly tripping and falling. Sometimes this may be due to torsional deformity of the tibiae (which must always be excluded), or be seen as a complication of cerebral palsy, but more often it is the result of a postural deformity of the hips (internal rotation) or excessive anteversion of the femoral neck. The condition generally corrects spontaneously by the age of 6. Continued observation is advised until correction occurs, but active treatment is seldom required.

Flat Foot

The arches of the foot do not start to form until a child starts walking, and they are not fully formed until about the age of 10; the young child’s foot is normally flat. Nothing is known to speed up the process of arch formation: orthopaedic shoes, heel cups and plastic moulded insoles have all been shown to be valueless. Failure of establishment of the arches is quite rare, but if this occurs it can lead to awkwardness of gait, rapid, uneven wear and distortion of the shoes, but seldom pain or other symptoms if joint mobility is preserved. Persistent flat foot may be associated with valgus deformities of the heel, knock knees, torsional deformities of the tibiae and shortening of the Achilles tendon. Rarely it may result from an abnormal talus (vertical talus) or neuromuscular disorders of the limb (e.g. poliomyelitis, muscular dystrophies). In the older child, gross deformities with a clear organic basis may require surgery, the nature of which is dependent on the pathology (e.g. calcaneal osteotomy for severe valgus heels).

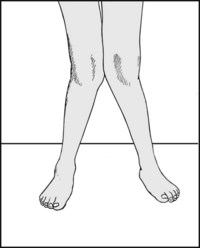

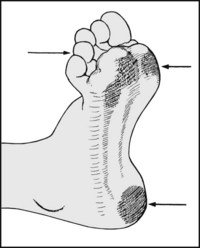

Pes Cavus

Abnormally high longitudinal arches are produced by muscle imbalance, which disturbs the forces controlling the formation and maintenance of the arches. In many cases there is a varus deformity of the heel and a first metatarsal drop (an increase in the angle between the first metatarsal and the tarsus). Two distinct groups are seen: those in which subtalar mobility is maintained, and those in which subtalar movements are decreased or absent. A neurological abnormality should always be sought, and sometimes this may be obvious (e.g. spastic diplegia or old poliomyelitis). Many cases are associated with spina bifida occulta, which may be confirmed by clinical and radiological examination. Rarely fibrosis of the muscles of the posterior compartment of the leg from ischaemia may be the cause. In the more severe cases there is weakness of the intrinsic muscles of the foot, with clawing of the toes; the abnormal distribution of weight in the foot leads to excessive callus formation under the metatarsal heads and the heel.

When the deformity is marked, surgery is indicated to relieve symptoms and lessen the chances of ultimate skin breakdown under the metatarsal heads. Where there is a varus deformity of the heel, correction of this defect alone may give good results; in some cases a wedge osteotomy of the distal tarsus or metatarsal bases is required to flatten the highly curved arch and improve the weight distribution in the foot. Where clawing of the toes is the most striking finding, proximal interphalangeal joint fusions of the toes or transplanting the flexor into the extensor tendons may be helpful.

Kohler’s Disease

This is an osteochondritis of the navicular occurring in children between the ages of 3 and 10. Pain of a mild character is centred over the medial side of the foot. Symptoms settle spontaneously over a few months and are not influenced by treatment.

Sever’s Disease

Chronic pain in the heel in children in the 6–12-year age group generally arises from the calcaneal epiphysis, which radiologically often shows increased density and fragmentation. The condition is usually referred to as Sever’s disease which, although originally considered to be an osteochondritis, is now believed to be due to a traction injury of the Achilles tendon insertion. Symptoms settle spontaneously without treatment.

Conditions Affecting the Adolescent Foot

Hallux Valgus

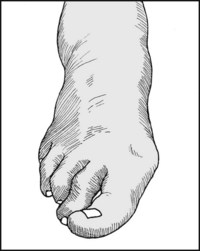

In adolescence, and particularly in girls, where there is competition between the rapidly growing foot, tight stockings and often small, high-heeled, unsuitable shoes, valgus deformity of the great toe first appears. In some cases a hereditary short and varus first metatarsal may contribute to the problem. As the deformity progresses, the drifting proximal phalanx of the great toe uncovers the metatarsal head, which presses against the shoe and leads to the formation of a protective bursa (bunion), often associated with recurrent episodes of inflammation (bursitis). The great toe may pronate, and further lateral drift results in crowding of the other toes; the great toe may pass over the second toe or, more commonly, the second toe may ride over it. The second toe may press against the toe cap of the shoe, where there is little room for it, and develop painful calluses. Later it may dislocate at the metatarsophalangeal joint. The sesamoid bones under the first metatarsal head may sublux laterally, leading to sharply localised pain under the first metatarsophalangeal joint. In the late stages of the condition, arthritic changes may develop in the metatarsophalangeal joint. More commonly, there is associated disturbance of the mechanics of the forefoot, leading to anterior metatarsalgia.

A number of surgical procedures are available to correct hallux valgus deformity. The most popular are (a) fusion of the metatarsophalangeal joint in a corrected position; (b) Keller’s arthroplasty (excision of the prominent part of the metatarsal head and removal of the basal portion of the proximal phalanx); (c) osteotomy of the first metatarsal neck (Mitchell operation); and (d) in early cases, simple excision of the prominent part of the metatarsal head may give relief. Silicone replacement of the metatarsophalangeal joint is no longer advocated, as it has been found that a troublesome silicone granuloma almost invariably develops in the region within 4 years of surgery.

Peroneal (Spastic) Flat Foot

In adolescents (boys in particular), painful flat foot may be found in association with apparent spasm of the peroneal muscles. The foot is held in a fixed, everted position. Inversion of the foot is not permitted, and there is often marked disturbance of gait. The condition is frequently associated with ossification in a congenital cartilaginous bar bridging the calcaneus and navicular (tarsal coalition). This anomaly may be demonstrated radiologically. Surgery in the form of excision of the bar is now the normal treatment for this condition.

Exostoses

Apart from the exposure and prominence of the medial side of the first metatarsal head commonly seen in association with hallux valgus (and referred to as a first metatarsal head exostosis), several exostoses may give rise to trouble in adolescence:

Conditions Affecting the Adult Foot

Hallux Rigidus

Primary osteoarthritis of the metatarsophalangeal (MP) joint of the great toe often commences in adolescence and gives rise ultimately to pain and stiffness in this joint. It is commoner in males, and is not associated with hallux valgus. Sometimes the toe is held in a flexed position (hallux flexus), and the proximal phalanx and metatarsal head are thickened following joint narrowing and circumferential exostosis formation. Treatment is usually by fusion or Keller’s arthroplasty.

Adult Flat Foot

Gradual flattening of the medial longitudinal arch (incipient flat foot) may occur in those who spend much of the day on their feet. This is often associated with an increase in body weight and the degenerative changes of ageing in the supporting structures of the arch. When these changes are rapid, they give rise to pain (‘medial foot strain’). Secondary (tarsal) arthritic changes may also give rise to pain in long-standing flat foot, and are associated with loss of movement in the foot (rigid flat foot). Nevertheless, in two-thirds of cases of flat foot mobility is preserved in the ankle, subtalar and other foot joints (flexible or mobile flat foot), and there is no cause for clinical concern or significant potential for disability. (Ballet dancers and many professional footballers have grotesquely flat feet which do not interfere with their activities.)

In the early stages incipient flat foot may be helped by weight reduction, physiotherapy and arch supports. In the later stages, surgical shoes with moulded insoles may be the most helpful measure.

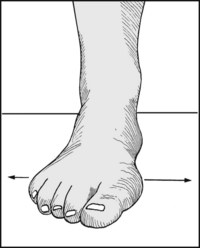

Splay Foot

Widening of the foot at the level of the metatarsal heads is known as splay foot. This may occur as a variation in the normal pattern of foot growth, causing no difficulty apart from that of obtaining suitable footwear. Splay foot may also be seen in association with metatarsus primus varus, hallux valgus and pes cavus.

Anterior Metatarsalgia

In anterior metatarsalgia there is complaint of pain under the metatarsal heads. The condition is particularly common in middle-aged women and is also often associated with some splaying of the forefoot. Symptoms may be triggered by periods of excessive standing or an increase in weight, and there is often a concurrent flattening of the medial longitudinal arch. Weakness of the intrinsic muscles is usually present, so that there is a tendency to clawing of the toes; hyperextension of the toes at the MP joints leads to exposure of the plantar surfaces of the metatarsal heads, which give high spots of pressure against the underlying skin. In turn this produces pain and callus formation in the sole. This pathological process is by far the commonest cause of forefoot pain, but in every case March fracture, Freiberg’s disease, plantar digital neuroma and verruca pedis should be excluded.

The majority of cases of anterior metatarsalgia respond to skilled chiropodial measures, which may include trimming of calluses and the provision of supports: these distribute the weightbearing loads more evenly under the metatarsal heads. Where there is much splaying of the forefoot and associated toe deformities, surgical shoes may be required. Where there is a marked hallux valgus deformity an MP joint fusion may improve the mechanics of the forefoot, with relief of pain.

March Fracture

This occurs in young adults and involves the second or, less commonly, the third or fourth metatarsals. The fracture usually follows a period of unaccustomed activity (there is no history of injury) and pain settles after 5–6 weeks when the fracture unites.

Freiberg’s Disease

This is an osteochondritis of the second metatarsal head associated with palpable deformity and pain. Pain may persist for 1–2 years, and in severe cases excision of the metatarsal head may become necessary. Excellent results have also been claimed for a dorsiflexion osteotomy of the metatarsal neck.

Plantar (Digital) Neuroma (Morton’s Metatarsalgia)

A neuroma situated on one of the plantar digital nerves just prior to its bifurcation at one of the toe clefts may give rise to piercing pain in the foot. It most commonly affects the plantar nerve running between the third and fourth metatarsal heads to the third web space, but any of the digital nerves may be affected. It most commonly occurs in women, particularly in the 25–45-year age group, and is often treated by excision of the affected nerve. Division of the intermetatarsal ligaments in the affected space without excising the nerve is said to give comparable results.

Verruca Pedis (Plantar Wart)

Verrucae, thought to be viral in origin, are common in the metatarsal region, the great toe and the heel. They must be differentiated from calluses, and are most frequently treated by the careful application of caustic preparations such as salicylic acid, acetic acid and carbon dioxide snow.

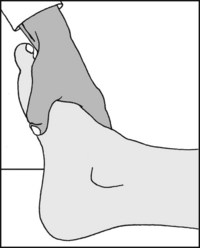

Plantar Fasciitis

Pain in the heel due to plantar fasciitis is a common complaint in the middle-aged. The condition is related to degeneration of the plantar fascia at its attachment to the medial calcaneal tuberosity. The condition has been described as having three stages. Initially there is a traction periostitis of the medial band of the plantar fascia, causing local heel pain. In the more advanced second stage, the posterior tibial nerve may be involved, giving rise to the symptoms and signs typical of tarsal tunnel syndrome. In the third stage, the tibialis posterior tendon may be affected, causing the occurrence of tenderness along the line of its course behind and beneath the medial malleolus and at its insertion in the navicular. There is seldom difficulty in making a diagnosis from the history and clinical findings, but local thickening of the plantar fascia may be confirmed by MRI scans or ultrasound examination. Symptoms tend to be prolonged, and the first aim of treatment is to reduce stress on the plantar fascia. Measures include weight loss, the wearing of lacing boots with small heels, night splints and orthoses. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been shown to be effective, but the use of NSAIDS and local steroid injections is no longer advised. In persistent cases, surgery in the form of fasciotomy of the medial band of the plantar fascia may be considered.

Mallet Toe, Hammer Toe, Claw Toe, Curly Toe

In a mallet toe there is a fixed flexion deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint of the toe; in a hammer toe there is a fixed flexion deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joint of a toe: the distal IP and MP joints are extended; in a claw toe both interphalangeal joints are flexed and the MP joint extended; and in a curly toe all three joints are flexed. In all these conditions corns may develop where the deformed toe presses against the footwear. Treatment may be conservative, by local chiropodial measures, or surgical, by means of interphalangeal joint fusions or, occasionally, in the case of mallet toe, by amputation. Simultaneous correction of an accompanying hallux valgus deformity may be required if a straightened second hammer toe is prevented from lying correctly because of the position of the hallux. Multiple clawed toes seen in association with pes cavus may be treated by IP joint fusions and flexor/extensor tendon transfers.

The Nail of the Great Toe

Ingrowing of the great toenail gives rise to pain and a tendency to recurrent infection at the nailfold. If infection is not a problem, skilled chiropody treatment (e.g. by nail training using a prosthetic device) is usually successful.

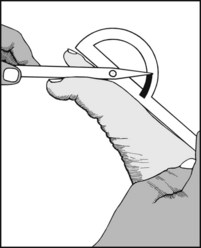

Where infection is marked, avulsion of the nail to permit drainage and healing is often required. In chronic cases, ablation of the nailbed (e.g. by phenolisation) may give a permanent cure.

Gross thickening and deformity of the nail (onychogryphosis) may also be treated by ablation of the nailbed or by regular chiropody.

Subungual exostosis, often a source of great pain, is treated by surgical removal of the exostosis.

Deformities of the nails may result from mycelial infections and are very resistant to treatment.

Abnormal pigmentation of the nail (melanonychia) requires investigation, generally by biopsy, to exclude malignancy.

Irregularity of nail growth is a common feature of psoriasis and is usually associated with skin lesions elsewhere. There may be an accompanying psoriatic arthritis.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

The foot is commonly involved in rheumatoid arthritis and the deformities are often multiple and severe. They frequently include pes planus, splay foot, hallux valgus, clawing of the toes, and subluxation of the toes at the MP joints. Anterior metatarsalgia is often marked. Sometimes a single deformity, such as a hammer toe, may be the main source of the patient’s symptoms and may be amenable to a simple local surgical procedure. Where there are many deformities, the prescription of surgical shoes with moulded insoles may be the best treatment. Where there is gross crippling deformity, Fowler’s operation, which is an arthroplasty of all the metatarsophalangeal joints combined with a plastic reconstruction of the metatarsal weightbearing pad, is often helpful in older patients; the best results may be obtained when the procedure is combined with fusion of the first MP joint.

Gout

Gout classically affects the MP joint of the great toe, but in severe cases the other MP joints and even the tarsal joints are involved in the arthritic process. The treatment is mainly medical, but surgical footwear may be required.

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

The posterior tibial nerve may become compressed as it passes beneath the flexor retinaculum into the sole of the foot, giving rise to paraesthesia and burning pain in the sole of the foot and in the toes. The condition is uncommon, but is relieved by division of the flexor retinaculum. The superficial peroneal nerve may also be compressed as it runs under the extensor retinaculum on the dorsum of the foot, giving paraesthesia in the area of its distribution.

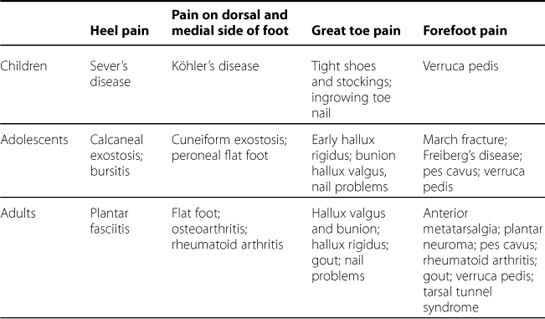

Diagnosis of Foot Complaints

The following tables list the most common disorders and relate them to the age groups in which they have the highest incidence.

| Factors in flat foot | Factors in pes cavus | |

|---|---|---|

| Infants |

Children

Adolescents

Adults

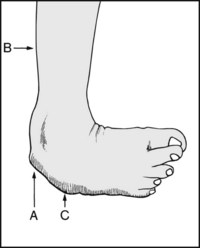

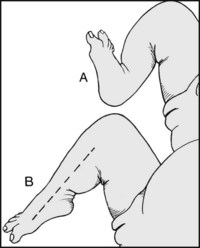

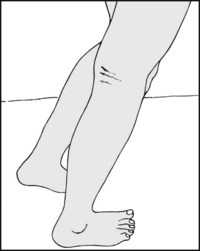

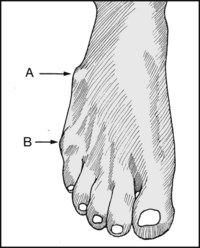

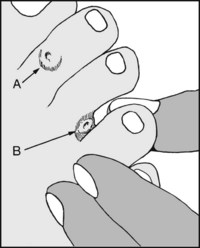

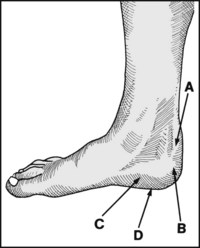

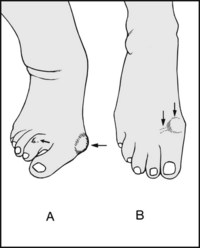

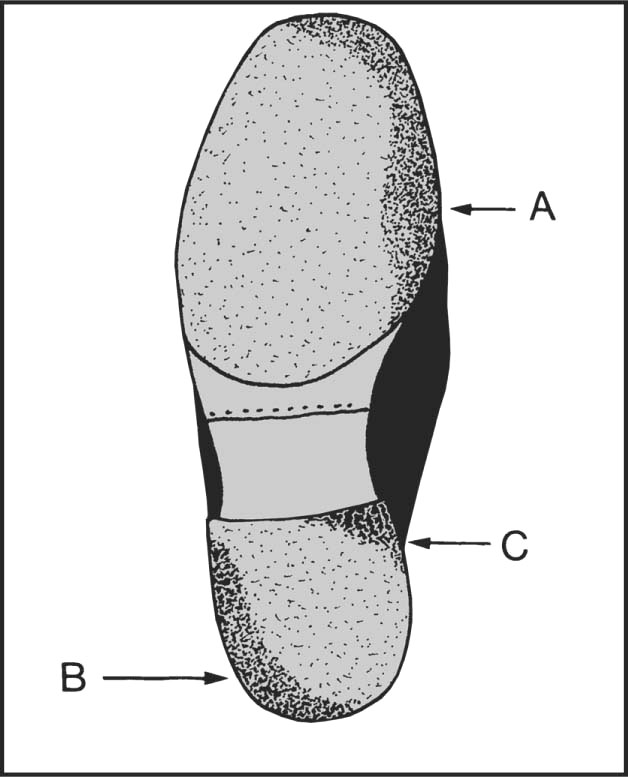

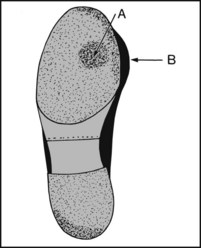

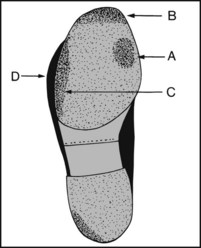

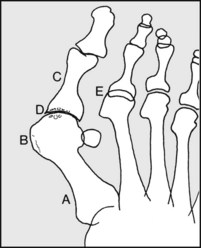

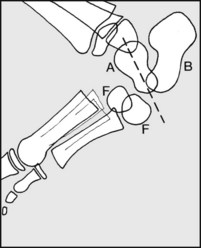

13.1. Clubfoot (1): talipes equinovarus:

In the untreated case there is (A) persisting varus of the heel, (B) atrophy of the calf muscles, (C) callus where the child walks on the lateral border of the foot. It is commoner in males, may be bilateral, and may be associated with other anomalies.

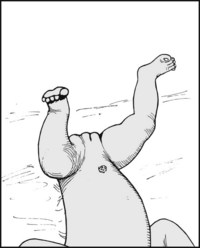

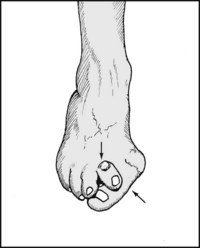

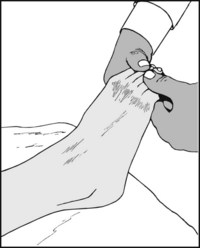

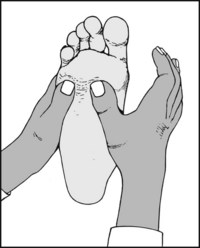

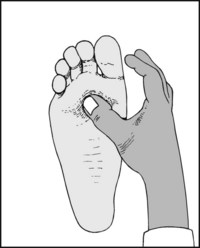

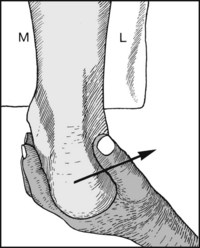

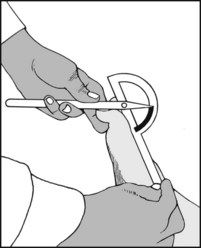

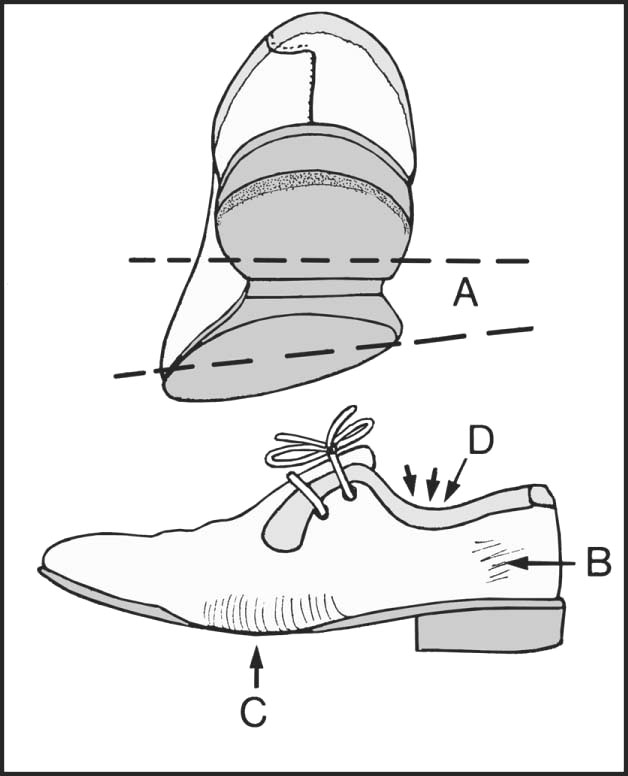

The newborn child often holds the foot in plantarflexion and inversion, giving a false impression of deformity. First observe the child as it kicks to see if this position is maintained.

If the child maintains the foot in the inverted position, support the leg and lightly scratch the side of the foot.

In the normal foot the child will respond by dorsiflexion of the foot, eversion, and fanning of the toes. This reaction does not take place if the child has a talipes deformity.

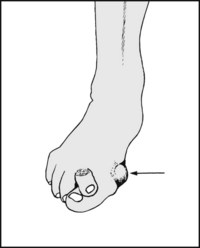

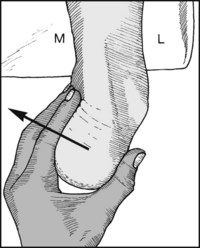

If the child does not respond in a normal fashion, gently dorsiflex the foot. In the normal child, the foot can be brought either into contact with the tibia or very close to it.

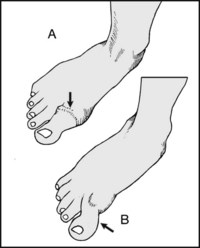

(A) Note that in the less common talipes calcaneus deformity, the foot is held in a position of dorsiflexion. (B) Note that in the normal infant the foot can be plantarflexed to such a degree that the foot and tibia are in line.

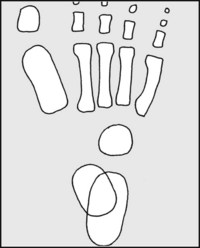

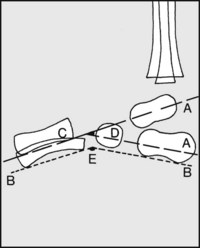

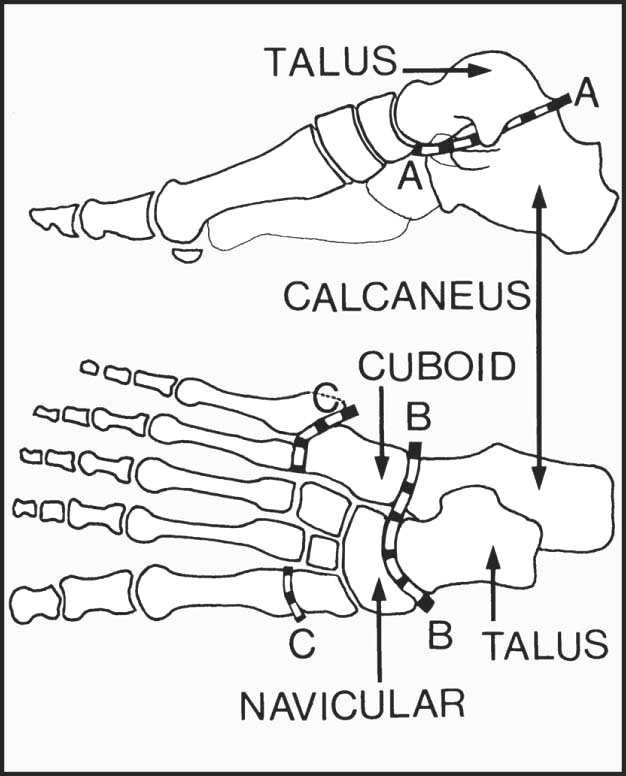

13.7. Radiographs: anteroposterior view (1):

Interpretation is difficult owing to the incompleteness of ossification. Centres for the talus, calcaneus, metatarsals, phalanges, and often the cuboid are present at birth. Begin by drawing a line through the long axis of the talus.

13.8. Radiographs: anteroposterior view (2):

This line normally passes through the first metatarsal, or lies along its medial edge. Note also that the axes of the middle three metatarsals are roughly parallel. Now draw a second line through the long axis of the calcaneus.

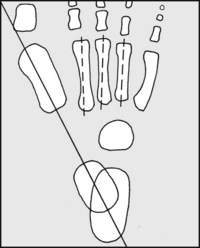

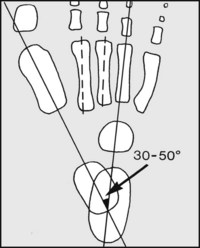

13.9. Radiographs: anteroposterior view (3):

Note (A) the axial line of the calcaneus passes through or close to the fourth metatarsal. (B) The axes of the talus and calcaneus subtend an angle of 30–50°.

13.10. Radiographs: anteroposterior view (4):

In club foot, the previously described relations are altered owing to forefoot adduction. Note (A) the talar axis does not cut the first metatarsal; (B) the middle three metatarsal axes are not parallel; (C) the calcaneal axis does not strike the fourth metatarsal; (D) the angle between the talus and calcaneus is reduced.

13.11. Radiographs: lateral (1):

Draw (A) axes through talus and calcaneus, and (B) tangents to the calcaneus and fifth metatarsal. Note that in the normal foot at birth that the talar axis passes below the first metatarsal (C); the interaxial angle (D) is 25–50°; the angle between the tangents (E) is 150–175°.

13.12. Radiographs: lateral (2):

In club foot, note (A) the talar and calcaneal axes are nearly parallel; (B) the angle of the tangents is less obtuse; (C) the talar axis does not pass below the first metatarsal. Geometric analysis of the type discussed on this page may be of help in the doubtful case and in assessing progress, and MRI scans are of particular value in determining talonavicular alignment.

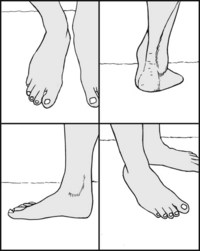

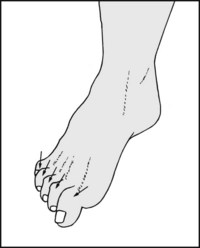

Note the shape of the foot, and the presence of any obvious deformities, abnormal callus formation etc.

The Mature Foot: Summary of the Key Stages in Examination (Frames 13.13–13.18)

Examine the gait, with and without shoes. If indicated, screen the ankles, knees, hips and spine; examine the circulation, and carry out a neurological examination. Note the footprint and examine the shoes.

Study the results of special investigations, e.g. radiographs, serum uric acid, sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor etc.

Note whether the foot is normally proportioned. If not, look at the hands and assess the rest of the skeleton. In Marfan’s syndrome, for example, the feet are long and thin (arachnodactyly, spider bones).

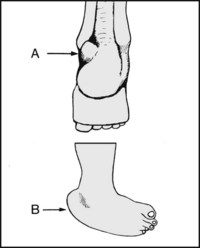

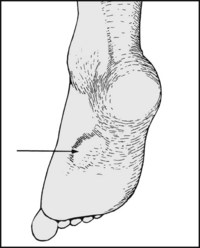

Is there (A) a calcaneal prominence (‘calcaneal exostosis’) with overlying callus or bursitis? (Note that where the exostosis is primarily lateral it is known as a Haglund deformity.) Is there deformity of the heel, suggesting old fracture or (B) talipes deformity?

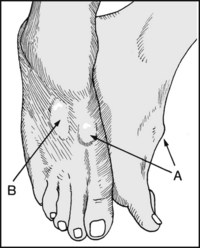

13.21. Inspection: dorsum (1):

Is there (A) prominence of the fifth metatarsal base? (B) an ‘exostosis’ from prominence of the fifth metatarsal head? (The latter is sometimes known as a bunionette or tailor’s exostosis.) Both can be a source of local pressure symptoms.

13.23. Inspection: dorsum (3):

Note the general state of the skin and nails. If there is any evidence of ischaemia, a full cardiovascular examination is required. In all cases, the presence of the dorsalis pedis pulse should be sought routinely.

13.24. Inspection: great toe (1):

Note any hallux valgus deformity. If the deformity is severe, the great toe may under- or over-ride the second, and it may pronate. The second toe may sublux at the MP joint. Always reassess any valgus deformity of the great toe with the foot weightbearing.

13.25. Inspection: great toe (2):

Note the presence of any bursa over the MP joint (bunion) and whether active inflammatory changes are present (from friction or infection). Discoloration of the joint with acute tenderness is suggestive of gout.

13.26. Inspection: great toe (3):

Note whether (A) the great toe is thickened at the MP joint, suggesting hallux rigidus (osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint), or (B) held in a flexed position (hallux flexus), again generally due to osteoarthritis.

13.27. Inspection: great toe (4):

Note the presence of excess callus under the great toe. This finding is highly suggestive of hallux rigidus.

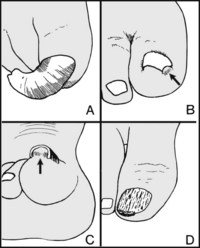

13.28. Inspection: great toenail (1):

Note whether the great toenail is (A) deformed (onychogryphosis), (B) ingrowing, possibly with accompanying inflammation, (C) elevated (suggesting subungual exostosis), (D) uneven in texture and growth (suggesting fungal infection or psoriasis).

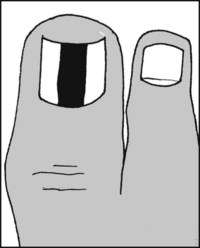

13.29. Inspection: great toenail (2):

Note, if present, the striking appearance of melanonychia. This is where there is longitudinal brown or black streaking of the nail due to any cause. The condition is first seen after puberty, and usually only one digit is affected – most often the great toe or the thumb. Malignancy must be excluded, and all cases should be referred without delay for biopsy.

Note the relative lengths of the toes. A second toe longer than the first may occasionally become clawed or throw additional stresses on its MP joint; it may be associated with Freiberg’s disease.

Flex the toes and note the relative lengths of the metatarsals. Abnormally short first or fifth metatarsals are a potential cause of forefoot imbalance and pain. When both are short, there is often painful callus under the second metatarsal.

13.32. Inspection: toes (3): curly toe:

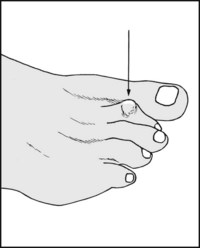

In this deformity a degree of fixed flexion develops in both IP joints and the MP joint. It is generally caused by interosseous muscle weakness. In grade 1 the toe is mildly flexed, with or without some adduction; in grade 2 there is a degree of under- or over-riding; and in grade 3 the nail is not visible from the dorsum.

13.33. Inspection: toes (4): claw toes:

The toes are said to be clawed when they are extended at the metatarsophalangeal joints and flexed at the interphalangeal joints. If all the toes are involved, this suggests that there may be an associated pes cavus or some other cause of intrinsic muscle insufficiency (the lumbricals and interossei flex the MP joints and extend the IP joints).

Is there a hammer toe deformity, where the toe is flexed at the proximal interphalangeal joint and extended at the MP and distal IP joint? The second toe is most commonly affected, often owing to an associated hallux valgus deformity. There is usually callus over the prominent interphalangeal joint as a result of pressure against the shoe.

Note the presence of (A) a mallet toe deformity (flexion deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint). There is usually callus under the tip of the toe or deformity of the nail. Note (B) an overlapping fifth toe or quinti varus deformity (often congenital). Prominence of the fifth metatarsal head (bunionette, taylor’s bunion) may be related, but seldom causes problems.

Note the presence of (A) hard corns. These are areas of hyperkeratosis that occur over bony prominences, and are generally caused by pressure against the shoes. (B) Soft corns are macerated hyperkeratotic lesions occurring between the toes and are not associated with pressure or friction.

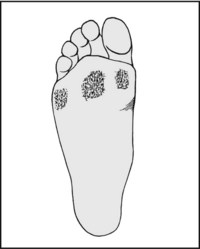

Note (A) Hyperhidrosis. (B) Evidence of fungal infection or athlete’s foot. (C) Ulceration of sole, suggesting pes cavus or neurological disturbance (trophic ulceration).

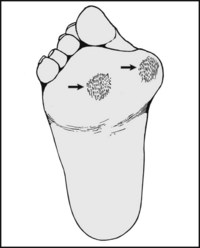

Note the presence of callus, indicating an uneven or restricted area of weightbearing. Be careful to distinguish between abnormal, local thickening, and diffuse, moderate thickening at the heel and under the metatarsal heads (which is normal).

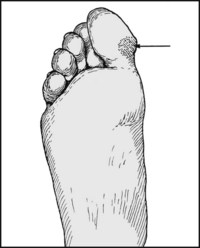

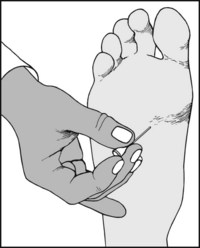

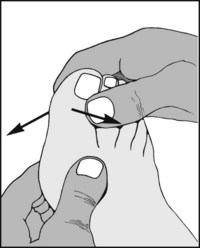

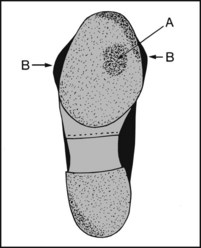

Note the presence of a verruca (plantar wart). Note the three classic sites: at the heel, under the great toe, and in the forefoot in the region of the metatarsal heads. In the sole they are situated between the metatarsal heads: unlike calluses, they do not occur in pressure areas.

verruca, contd. A verruca is exquisitely sensitive to side to side pressure. Calluses are much less sensitive, and only to direct pressure. If there is any remaining doubt a magnifying lens may be used to confirm the central papillomatous structure of the verruca.

Note any localised fibrous tissue masses in the sole typical of Dupuytren’s contracture of the feet. These tissue thickenings arise from the plantar fascia, and are attached to the skin. Always inspect the hands, as both upper and lower limbs are often involved together in this process.

Examine the patient standing. Are both the heel and forefoot squarely on the floor (plantigrade foot)? If the heel does not touch the ground, examine for shortening of the leg or shortening of the tendocalcaneus.

If this deformity is present, examine for (A) torsional deformity of the tibia, (B) increased internal rotation of the hips, or (C) adduction of the forefoot. Most cases of intoeing in children resolve spontaneously by age 6.

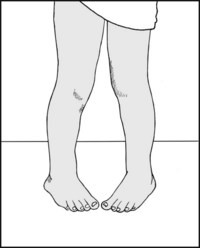

13.44. Posture (3): genu valgum:

Note the presence of genu valgum, which is frequently associated with valgus flat foot. Genu valgum in turn is most commonly seen as a result of a growth disturbance about the knee, or as a complication of rheumatoid arthritis.

If the foot is everted this suggests (A) peroneal spastic flat foot, (B) a painful lesion on the lateral side of the foot, (C) if less marked, pes planus.

13.46. Posture (5): inversion:

If the foot is inverted this suggests (A) muscle imbalance from stroke or other neurological disorder, (B) hallux flexus or rigidus, (C) pes cavus, (D) residual talipes deformity, (E) a painful condition of the forefoot.

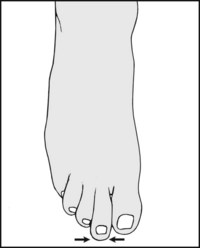

Note whether there is any broadening of the forefoot. This is often the result of intrinsic muscle weakness, and may be associated with pes cavus, callus under the metatarsal heads, hallux valgus, anterior metatarsalgia, and trouble with shoe fitting.

Reassess the toes for curling, clawing, mallet toe and hammer toe. Reassess the great toe, particularly for the degree of hallux valgus, over-riding of adjacent toe(s), and torsion.

13.49. Posture (8): medial arch (1):

With the patient weightbearing, look at the medial longitudinal arch and try to assess its height. Try to slip the fingers under the navicular. In pes cavus, the fingers may penetrate a distance of 2 cm or more from a vertical line dropped from the medial edge of the foot.

13.50. Posture (9): medial arch (2):

If the arch appears high and accentuated, this suggests a degree of pes cavus. Look for confirmatory clawing of the toes, callus or ulceration under the metatarsal heads, and alteration of the footprint.

13.51. Posture (10): medial arch (3):

If pes cavus is present, carry out a full neurological examination. Look at the lumbar spine for dimpling of the skin, a hairy patch, or pigmentation suggesting spina bifida or neurofibromatosis. Radiological examination of the lumbar spine is desirable.

13.52. Posture (11): medial arch (4):

In pes planus, the medial arch is obliterated. The navicular is often prominent, and the fingers cannot be inserted under it. Ask the patient to attempt to arch the foot. In mobile flat foot the arch can often be restored voluntarily. Note that in children the arches are slow to become established. Examine the Achilles tendon, shortening of which can cause flat foot.

13.53. Posture (12): medial arch (5):

If pes planus is suspected, re-examine the sole for confirmatory evidence of callus under the metatarsal heads, and an increase in the area of the sole involved in weightbearing (i.e. extension of the narrow lateral strip). The footprint will be abnormal in these circumstances. Note also the presence of any knock-knee deformity.

13.54. Posture (13): medial arch (6):

In pes planus, assess the mobility of the foot first by asking the patient to stand on the toes, while at the same time examining the alteration in the shape of the foot by sight and feel. Later in the examination carefully note the range of inversion and eversion. Note that although 23% of adults have flat feet, symptoms are not usually present unless there is associated stiffness.

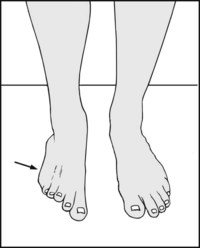

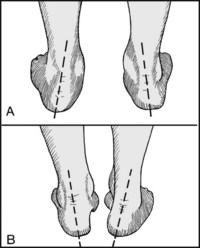

13.55. Posture (14): heel (1):

Look at the foot from behind, paying particular attention to the slope of the heels. Note (A) valgus heels are associated with pes planus, (B) varus heels are associated with pes cavus.

13.56. Posture (15): heel (2):

Again ask the patient to stand on the toes, observing the heels. If the heel posture corrects, this indicates a mobile subtalar joint. Persisting deformity suggesting loss of movement, which may be due to arthritic changes, tarsal coalition, loss of spring ligament or tibialis posterior function, or shortening of the tendocalcaneus.

Watch the patient walking, first barefooted and then in shoes, to assess the gait. Examine from behind, from in front, and from the sides. A child should also be made to run. A reluctant child can usually be coaxed to walk holding its mother’s hand. Highly technical methods of gait analysis using force plates, computer and videoanalysis etc. are available in some centres.

Grasp the foot and assess the skin temperature, comparing one side with the other. Take into account the effects of local bandaging and the ambient temperature. A warm foot is particularly suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

If the foot is cold, note the skin temperature gradient along the length of the limb. You should have already observed any trophic changes or discoloration of the skin suggestive of ischaemia.

Attempt to palpate the dorsalis pedis artery. The vessel lies just lateral to the tendon of extensor hallucis longus and its pulsation should be felt by compressing it against the middle cuneiform. A good pulse generally excludes any significant degree of ischaemia.

Now try to feel the anterior tibial pulse near that midline of the ankle, just above the joint line where the vessel crosses the distal end of the tibia.

The posterior tibial artery is often difficult to find, and it is helpful to invert the foot while palpating behind the medial malleolus.

Next seek the popliteal artery. When the patient is supine it can only be felt by applying strong pressure in an anterior direction, with the knee flexed to force the vessel against the femoral condyles. Alternatively, it may be sought with the patient prone.

The femoral pulse may be felt a little to the medial side of the midpoint of the groin, when the artery can be compressed against the superior pubic ramus.

Examine the abdomen, palpating the abdominal aorta. Note the presence of pulsation as it is compressed against the lumbar spine, and note any evidence of aneurysmal dilatation.

Note any cyanosis of the foot when dependent and any blanching on elevation, suggestive of marked arterial insufficiency.

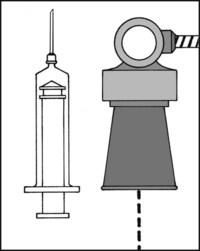

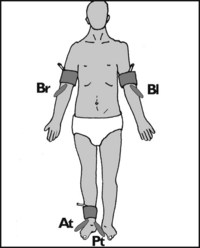

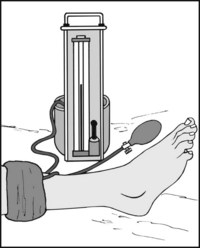

13.67. Circulation (9): ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI):

This is a simple non-invasive method of assessing arterial efficiency within a lower limb by comparing its blood pressure with that in the arms. The patient is asked to lie on the examination couch for 10 minutes to allow the blood pressure to stabilise. The blood pressure in the right arm (Br) is then taken, using a hand-held Doppler ultrasonic flow detector. This is repeated on the other side (Bl). Pressure readings are then obtained from the anterior and posterior tibial arteries (At, Pt) in the suspect limb. The index is then normally calculated by dividing the higher of the upper limb readings with the higher of the readings at the ankle (HAP), and this is the basis of most studies. (Recently it has been suggested that using the lower of the ankle readings (LAP) gives more reliable and sensitive results.) The findings may be interpreted as follows:

| 0.91–1.3 | Normal |

| 0.7–0.9 | Mild disease |

| 0.41–0.69 | Moderate disease |

| 0.4 or less | Severe disease |

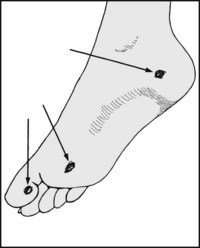

13.68. Tenderness (1): heel (1):

Tenderness round the heel is present in (A) Sever’s disease; (B) superior calcaneal exostosis and tendocalcaneus bursitis; (C) plantar fasciitis and inferior calcaneal exostosis; (D) pes cavus.

13.69. Tenderness (2): heel (2):

Where plantar fasciitis is suspected, perform Jack’s test. Forcibly dorsiflex the great toe to stretch the plantar fascia. Tenderness over the heel attachment of the fascia is diagnostic. Examine the posterior tibial nerve and the tibialis posterior tendon which may also be involved.

13.70. Tenderness (3): forefoot (1):

Diffuse tenderness under all the metatarsal heads is common in anterior metatarsalgia, pes cavus and pes planus, gout and rheumatoid arthritis.

13.71. Tenderness (4): forefoot (2):

Tenderness under the second metatarsal head and over the second metatarsophalangeal joint is found when the second toe subluxes as a sequel to hallux valgus or rheumatoid arthritis.

13.72. Tenderness (5): forefoot (3):

Puffy, localised swelling on the dorsum of the foot, palpable thickening of the second metatarsophalangeal joint, pain on plantarflexion of the toe, and joint tenderness are diagnostic of Freiberg’s disease.

13.73. Tenderness (6): forefoot (4):

Tenderness on both plantar and dorsal surfaces of the second or third metatarsal necks or shafts occurs in march fracture.

13.74. Tenderness (7): forefoot (5): suspected plantar neuroma (Morton’s metatarsalgia) (1):

Sharply defined tenderness between the metatarsal heads (most commonly between the third and fourth) is found in plantar digital neuroma.

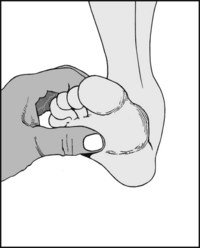

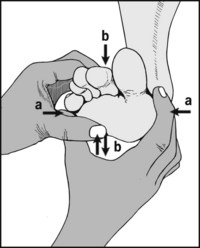

13.75. Suspected plantar neuroma (2):

Compress the metatarsal heads (a) and note whether this reproduces the patient’s symptoms of pain and possibly paraesthesia (Mulder’s sign). Repeat while simultaneously pressing in a coordinated fashion from the sole towards the dorsal surface and back with the other hand (b). This may result in a painful click, which some consider to be associated with a mobile neuroma.

13.76. Suspected plantar neuroma (3):

Sometimes the patient complains of paraesthesia in the toes, and sensory impairment should be sought on both sides of the web space involved. Note that a success rate of 95% is claimed for the diagnosis of neuroma by ultrasonography

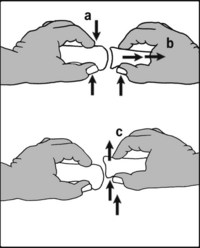

13.77. Suspected plantar neuroma (4):

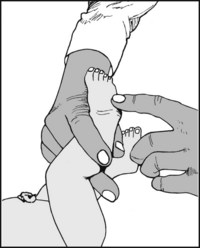

The symptoms and findings from MP joint instability in a toe may be confused with Morton’s metatarsalgia, so always perform the drawer test. To do so, grip the metatarsal at the suspect level with one hand (a) and with the other, while applying traction to the toe (b), attempt to displace it dorsally (c). Pain and excessive translation are diagnostic of instability.

13.78. Tenderness (7): tarsal tunnel syndrome (1):

Tenderness may occur over the posterior tibial nerve in the tarsal tunnel syndrome, where the presenting symptoms are usually of local pain and paraesthesia in the foot. Note that tenderness at the same site may occur in problems affecting the tibialis posterior tendon (which may be visualised by inverting the foot against resistance).

13.79. Tarsal tunnel syndrome (2): Tinel’s sign:

In the tarsal tunnel syndrome, tapping over the posterior tibial nerve may give rise to paraesthesia in the sole of the foot.

13.80. Tarsal tunnel syndrome (3):

Test sensation over the whole of the sole of the foot and the toes in the area of supply of the medial and lateral plantar nerves (the two terminal divisions of the posterior tibial nerve). Compare the feet. Sensory loss is in fact rather uncommon in tarsal tunnel syndrome.

13.81. Tarsal tunnel syndrome (4): the dorsiflexion–eversion test (Kinoshita et al.):

Maximally dorsiflex the ankle (a) and the MP joints of all the toes (b); firmly evert the foot (c) and hold this position. In a positive case the patient’s symptoms will be reproduced, sometimes after only a few seconds. Look also for increased local tenderness (d) accompanying the manoeuvre.

13.82. Tarsal tunnel syndrome (4): the tourniquet test:

In doubtful cases, apply a tourniquet to the calf and inflate to just above the systolic blood pressure. If this brings on the patient’s symptoms in 1–2 minutes, the diagnosis is confirmed. Pain and paraesthesia on the dorsum of the foot may be encountered in the much rarer superficial peroneal nerve compression syndrome.

13.83. Tenderness (8): great toe (1):

In gout, tenderness is often most acute but is diffusely spread round the whole metatarsophalangeal joint and often the entire toe. There is often a reddish-blue discoloration of the skin round the toe.

13.84. Tenderness (9): great toe (2):

(A) In hallux valgus tenderness is often absent, or confined to the bunion or over painful corns on adjacent toes. (B) In hallux rigidus there is usually tenderness over the exostoses that arise on the metatarsal head and proximal phalanx, often on the dorsal surface of the joint as well as the lateral side, where protective bursae may form.

In sesamoiditis there is tenderness over the sesamoid bones, which are situated under the first metatarsal head, although they may sublux laterally to a marked degree, especially in cases of gross hallux valgus. Pain is produced if the toe is dorsiflexed while pressure is maintained on the sesamoid bones.

13.86. Tenderness (11): great toenail:

In subungual exostosis pain is produced by squeezing the toe in the vertical plane. In ingrowing toenail pain is produced by side-to-side pressure.

Move the great toe in an up and down direction while palpating the metatarsophalangeal joint. Repeat with the interphalangeal joint. Crepitus, indicating osteoarthritic change, is constant in the metatarsophalangeal joint in hallux rigidus. Interphalangeal joint crepitus is considered a contraindication for MP joint fusion.

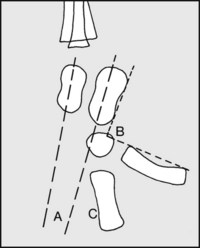

In assessing foot movements, remember that the total range of supination and pronation in the foot is made up of movements that occur in the subtalar joint (A–A), the midtarsal joint (B–B), and the tarsometatarsal joints (C–C). In the latter, the main movements occur in the joints at the bases of the first, fourth and fifth metatarsals.

13.89. Movements (2): supination:

Ask the patient to turn the soles of the feet towards one another. The patellae should be vertical. The resulting angle may be measured. If the legs are squarely placed on the couch, its end may be used as a guide.

Normal range = 35° approximately. Note that this is a summation of movements occurring at the three levels previously described.

13.90. Movements (3): pronation:

Ask the patient to turn the feet outwards. The range of movement may be measured in a similar fashion.

If supination and pronation are restricted, fix the heel with one hand and with the other assist the patient to repeat these movements. No further reduction in the range indicates a stiff subtalar joint. The presence of some movement shows that the midtarsal and tarsometatarsal joints preserve some mobility.

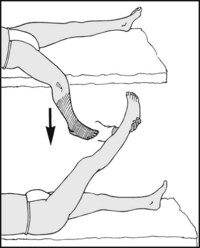

Turn the patient face down with the feet over the edge of the examination couch. Evert the heel and note the presence of movement in the subtalar joint by the position of the heel.

Repeat, forcing the heel into inversion.

Normal range of inversion of the heel = 20° approximately. Loss of movement indicates a stiff subtalar joint (e.g. old calcaneal fracture, rheumatoid or osteoarthritis, spastic flat foot).

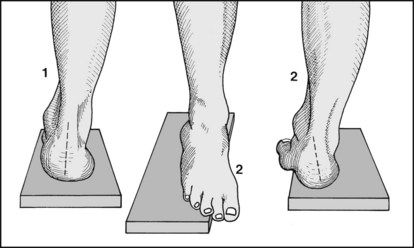

In idiopathic pes cavus, and pes cavus secondary to neuromuscular disease, the subtalar joint is generally mobile; in pes cavus secondary to congenital talipes equinovarus the subtalar joint is often stiff. As a further guide to the differentiation of these cases, mark the axis of the heel with a skin pencil and note its position with the patient standing on a 2 cm block of wood, first squarely (1), and then with the forefoot over the medial edge (2). A change in the axis (3) indicates a mobile subtalar joint.

Test for mobility in the first, fourth and fifth tarsometatarsal joints by steadying the heel with one hand and attempting to move the metatarsal heads individually in a dorsal and plantar direction.

13.96. Movements (9): great toe (1):

Note the range of extension in the great toe at the metatarsophalangeal joint.

13.97. Movements (10): great toe (2):

Note the range of flexion at the metatarsophalangeal joint.

Metatarsophalangeal movements are severely restricted and painful in hallux rigidus. There is often little impairment in hallux valgus unless secondary arthritic changes are quite severe.

13.98. Movements (11): great toe (3):

Note the range in the interphalangeal joint.

Restriction is common after fractures of the terminal phalanx, and is generally regarded as being a contraindication to metacarpophalangeal joint fusion.

13.99. Movements (12): lesser toes:

Overall mobility may be roughly assessed by alternately curling and straightening the toes. Accurate measurement of individual ranges is seldom needed. Restriction is often seen in gout, rheumatoid arthritis, Sudeck’s atrophy, and ischaemic conditions of the foot and leg.

It is sometimes helpful to see the pattern of weight distribution in the foot: note the imprint of the sweaty foot on a vinyl floor, or (A) apply olive oil to the sole and dust the imprint with talc; (B) use ink on paper (or fix on an X-ray plate and develop it). Various specialised technical methods are available. A pedoscope may also be used for this purpose.

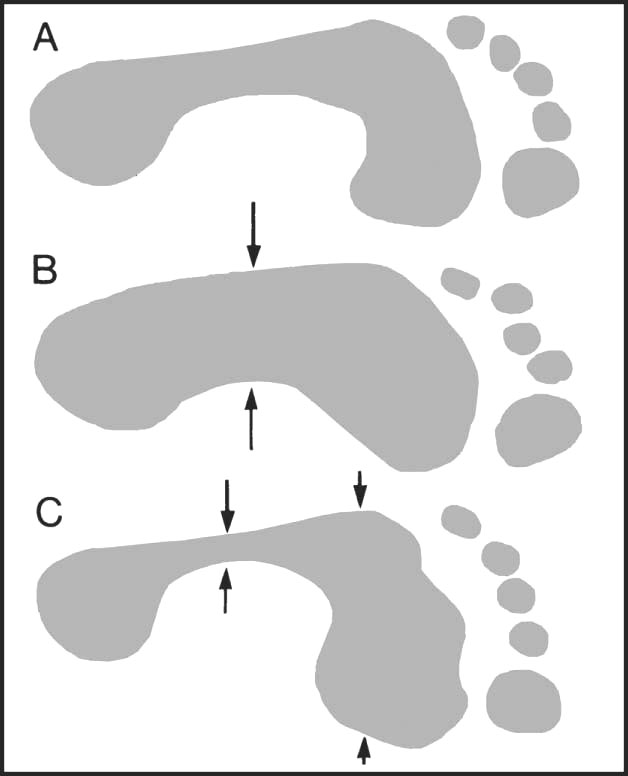

13.101. Footprint (2): typical patterns:

(A) Normal foot. (B) Pes planus. Note the increase in area of the central part of sole taking part in weightbearing. (C) Pes cavus. Note the decrease in area of contact in the midsole and the splaying of the anterior part of the foot. In extreme cases the lateral weightbearing strip may disappear.

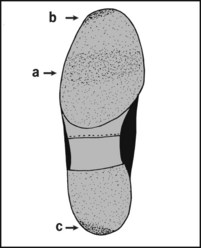

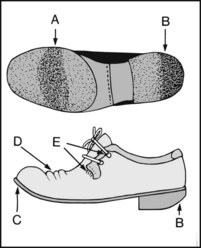

The patient’s only complaint may be shoe wear. Inspection is expected and may be helpful. In the normal sole wear is fairly even, being maximal across the tread (a) and at the tip (to the lateral side) (b). At the back of the heel (c), maximum wear is also to the lateral side.

13.103. Shoes (2): the too-short shoe:

Note (A) the excessive wear at the toe and heel. (B) A gap may appear above sole. (C) The toe cap may bulge, and the inside of shoe may be marked by the toes. (D) The heel may give at the seam. There may be blistering of the heel, and excessive sock wear. (E) A gap may appear between the quarter and the ankle.

13.104. Shoes (3): pes planus (1):

Note (A) wear on the medial side of the sole extending to the tip; (B) wear on the outer side of heel; (C) in severe cases, wear on the diagonal corner of heel.

13.105. Shoes (4): pes planus (2):

Note (A) the shoe may be twisted when viewed from behind (i.e. the heel and sole are on different planes); (B) scuff marks on medial side; (C) the upper bulges over the sole on the medial side. The quarter bulges away from the foot (D).

13.106. Shoes (5): splay foot:

Note (A) excess wear in the region of the first or second metatarsal heads. (B) The upper bulges over the sole anteriorly.

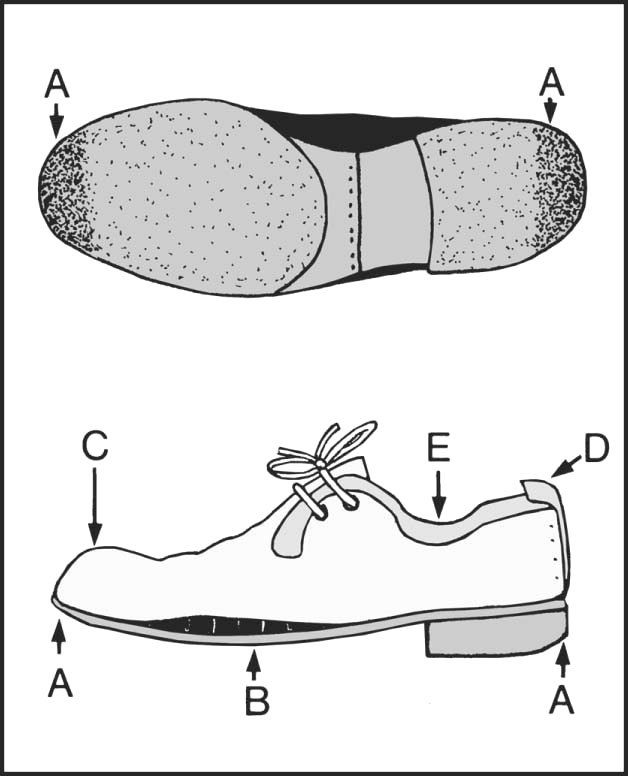

Note (A) excessive wear under the metatarsal head region; (B) excessive wear at the back of the heel; (C) raising of toe; (D) creases; (E) giving way of lacings.

13.108. Shoes (7): hallux valgus:

There is often (A) excess wear as in splay foot under the area of the first and second metatarsal heads; (B) bulging of the upper to accommodate the prominent first metatarsal head.

13.109. Shoes (8): hallux rigidus:

Note (A) excessive wear under the first metatarsal head and (B) at the tip of the sole; (C) excess wear on the lateral side (through walking on the side of the foot); (D) lateral overhang. In addition, the toe of the shoe may be upturned.

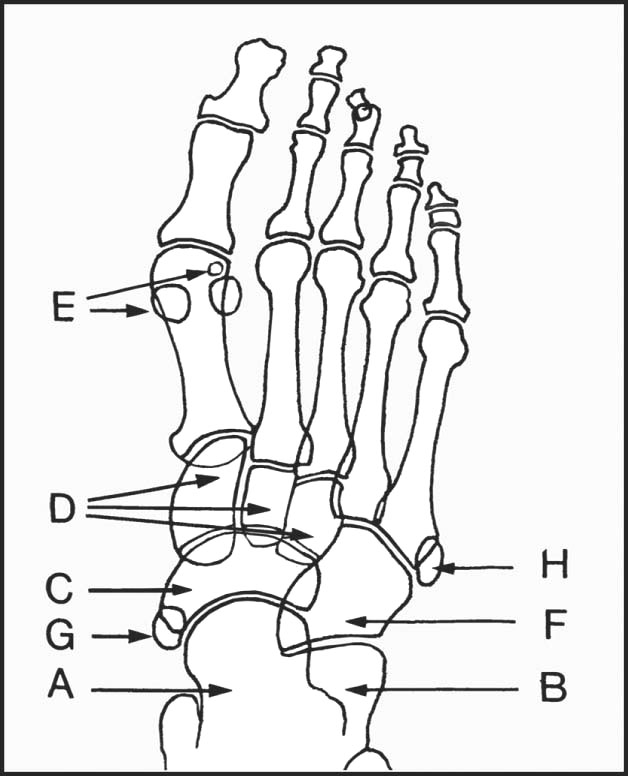

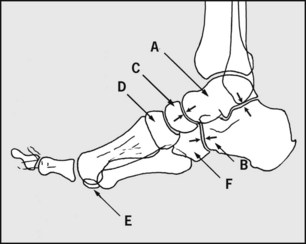

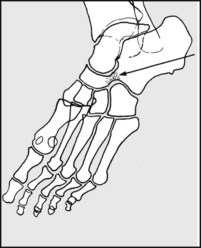

An AP view is routine, along with either a lateral or an oblique. Note (A) talus; (B) calcaneus; (C) navicular; (D) cuneiforms; (E) sesamoids (often bi- or tripartite); (F) cuboid. Inconstant accessory bones may be mistaken for fracture or loose bodies, e.g. (G) os tibiale externum; (H) os Vesalianum.

In the AP view, note the bone texture and typical anomalies, such as (A) march fracture (periosteal reaction occurs in the healing stages); (B) Freiberg’s disease affecting the second metatarsal head; (C) osteoarthritic changes with exostosis formation (hallux rigidus).

Note, if present, (A) metatarsus primus varus; (B) first metatarsal ‘exostosis’; (C) hallux valgus; (D) joint narrowing or cyst formation, suggestive of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or gout; (E) metatarsophalangeal joint subluxation secondary to hallux valgus or to rheumatoid arthritis.

In the child, note any increased density of the navicular, suggestive of Kohler’s disease. The bone may appear reduced in size.

In the lateral radiograph it is often difficult to trace the outline of individual metatarsals owing to superimposition, although the first and fifth are usually quite clear; (A) talus, (B) calcaneus, (C) navicular, (D) medial cuneiform, (E) sesamoid, (F) cuboid. Note the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints.

Note, if present, (A) the accessory os trigonum (often mistaken for a fracture), (B) cuneiform exostosis, (C) narrowing of the midtarsal joint, and other changes suggestive of midtarsal rheumatoid or osteoarthritis.

Note, if present in the adult, (A) calcaneal spur, sometimes associated with plantar fasciitis, (B) footballer’s ankle, (C) in the child, increased density and fragmentation of the calcaneal epiphysis, seen in Sever’s disease.

Congenital vertical talus, which is associated with dislocation of the talonavicular joint, has a classic radiographic appearance. Note the direction of the long axis of the talus. (A) Talus; (B) calcaneus; (F) both centres of ossification of the cuboid. (This condition is normally treated by manipulative reduction and the application of serial casts. Improved results are claimed for subsequent pinning of the talonavicular joint and percutaneus tenotomy of the tendocalcaneus.)

Calcaneonavicular bar or synostosis (and the commonest of the tarsal coalitions) is best seen in oblique projections of the foot, and is found in association with spastic flat foot.

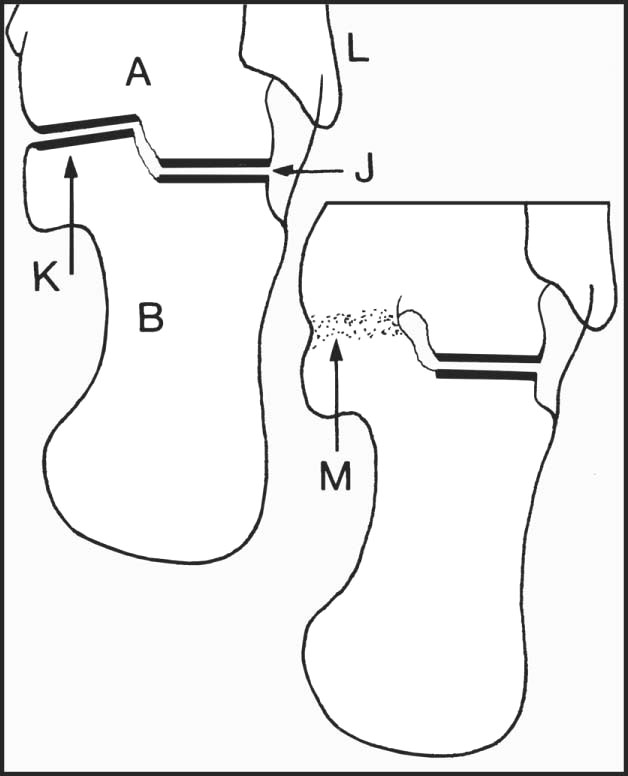

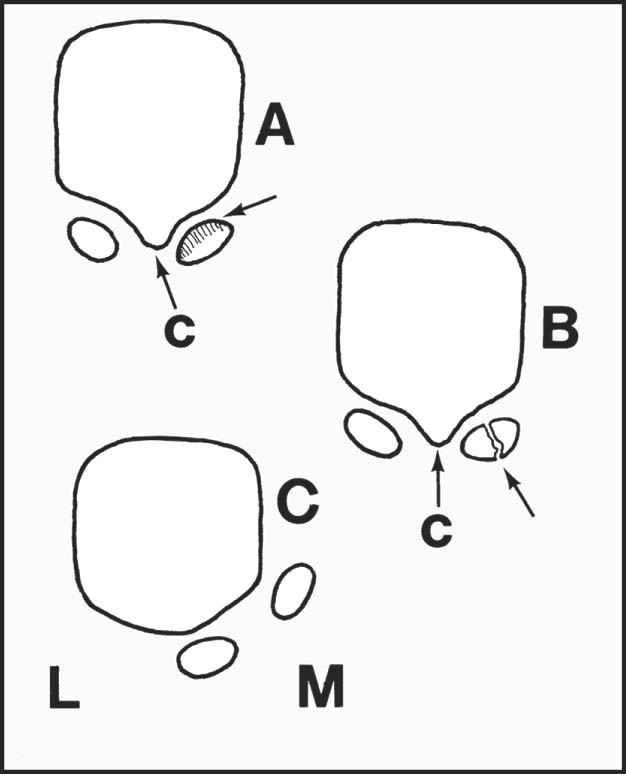

An axial or tangential projection of the heel shows (A) talus, (B) calcaneus, (J) posterior talocalcaneal joint, (K) sustentaculum tali, (L) base of fifth metatarsal. A talocalcaneal synostosis (M), sometimes found in spastic flat foot, may be demonstrated by this view.

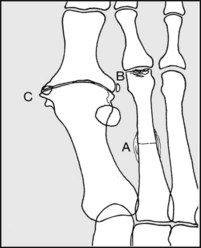

A tangential projection may be used when the sesamoid bones are suspect, showing, for example, (A) osteochondritic changes, (B) stress fracture, (C) dislocation and loss of the crista (c), seen most commonly in association with advanced hallux valgus.

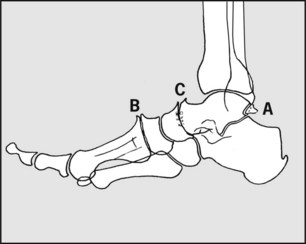

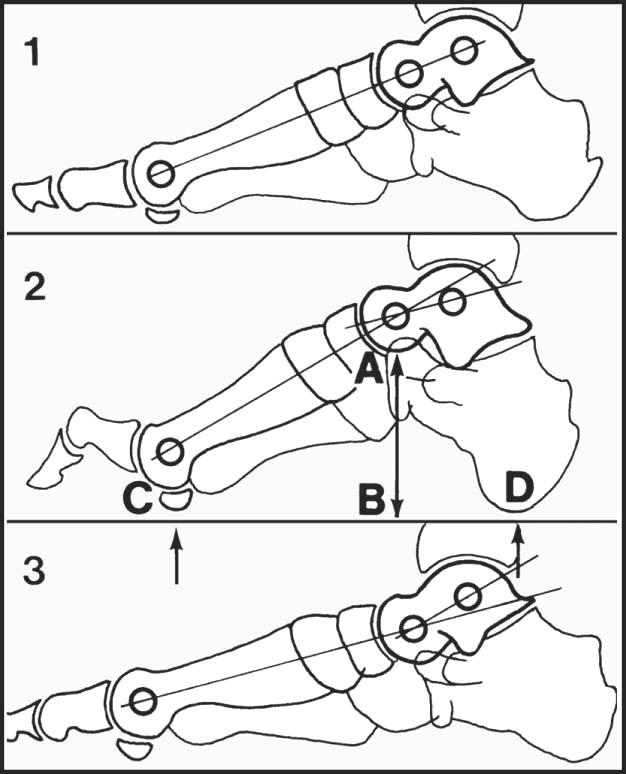

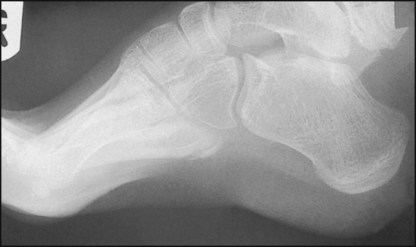

A weightbearing lateral projection is of value in assessing deformities involving the medial longitudinal arch and the toes. The axes of the talus and first metatarsal normally coincide, and the height of the arch may be assessed by noting the ratio AB/CD: (1) normal, (2) pes cavus, (3) pes planus.

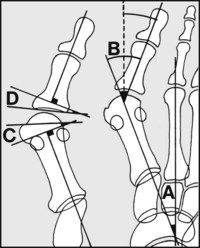

In assessing hallux valgus, note (A) the intermetatarsal angle (the ‘1/2 angle’) is normally 9° or less – more suggests metatarsus primus varus; (B) the so-called hallux valgus angle is normally 16° or less. (True valgus of the hallux is B–A.) The normal distal metatarsal articular and proximal phalangeal articular angles (C and D) are respectively 15° and 5° (or less).

13.126. Radiographs of the foot: examples of pathology (1):

Note the accentuation of both the medial and lateral longitudinal arches of the foot.

There is marked destruction of the second metatarsal head, with broadening and loss of concavity in the base of the proximal phalanx.

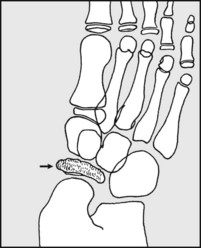

This is an axial (tangential) projection of a patient found to have a painful rigid flat foot. The medial part of the subtalar joint, between the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus and the talus on the right side of the radiograph is not apparent.

Diagnosis: talocalcaneal synostosis (coalition) in the region of the sustentaculum tali.

This oblique radiograph shows a thick bridge of bone uniting the calcaneus with the navicular. The patient had a spastic flat foot.

Diagnosis: calcaneonavicular synostosis (calcaneonavicular coalition; calcaneonavicular bar).

The patient, a probationer nurse, gave a 5-week history of anterior foot pain, and the radiograph of her foot shows new bone formation in the second metatarsal shaft.

There is distortion of the normal architecture of the calcaneus associated with the presence of two large cystic spaces in the bone.

Diagnosis: the appearances are typical of a simple, multilocular bone cyst.

There was complaint of pain on the posteromedial aspect of the foot, and the inferior surface of the calcaneus is elongated.

Diagnosis: plantar fasciitis associated with a large exostosis or calcaneal spur.

The terminal phalanx has virtually disappeared, and there is gross soft tissue swelling of the toe which was associated with great pain.

Diagnosis: the appearances are due to a severe nail infection which has spread locally, leading to a destructive osteitis.

The metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe is narrowed, and there is marked osteoarthritic lipping on both sides of the joint. Little movement was present.

The first metatarsal is short and medially inclined. The forefoot is broadened. The great toe is tilted laterally, and the head of the first metatarsal is uncovered and prominent. The two phalanges of the great toe are rotated.

Diagnosis: gross hallux valgus deformity associated with a metatarsus primus varus. There is pronation of the great toe, and splaying of the forefoot.

There are valgus deformities of all the toes. The MP joints of all the lesser toes are dislocated, and the sesamoid bones are displaced laterally. The bones are somewhat osteoporotic.

There is evidence of a united avulsion fracture of the styloid process of the fifth metatarsal base. There is widespread decalcification and disturbance of bone texture, with clinically marked swelling and stiffness of the foot.

Diagnosis: Sudeck’s atrophy (complex regional pain syndrome, post-traumatic osteodystrophy) secondary to local trauma.