CHAPTER 10 The knee

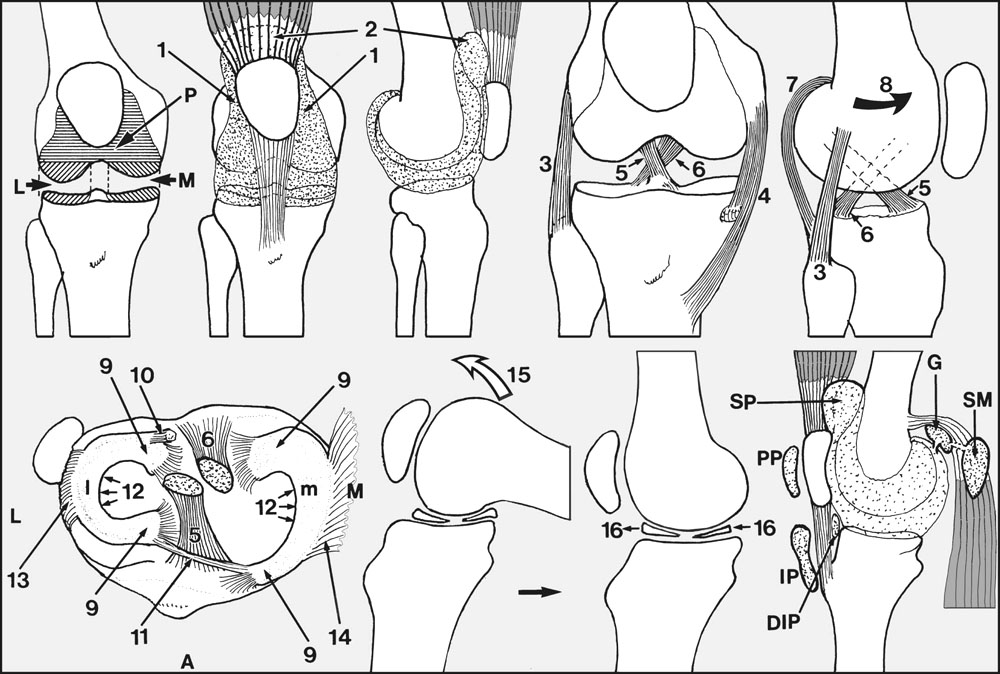

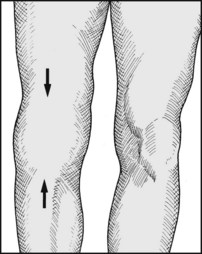

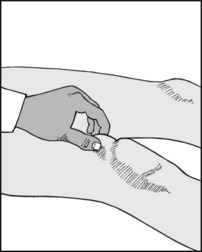

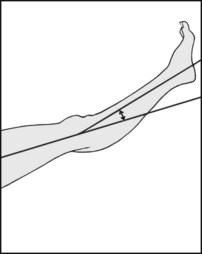

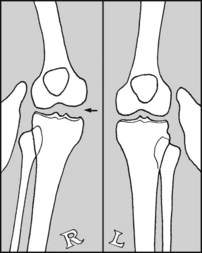

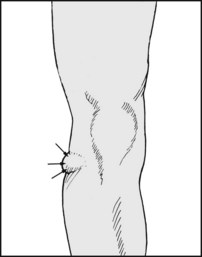

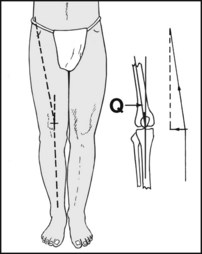

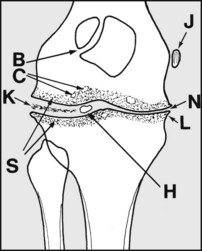

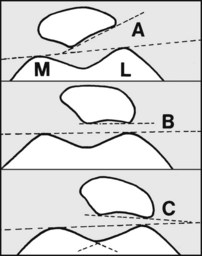

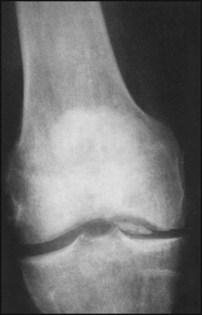

Fig. 10.A.

Anatomical Features

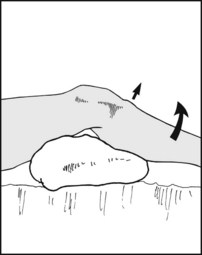

The knee joint (Fig. 10.A) combines three articulations (medial tibiofemoral (M), lateral tibiofemoral (L) and patellofemoral (P)), which share a common synovial sheath; anteriorly, this extends a little to either side (1) of the patella and an appreciable amount proximal to its upper pole (2). This portion, the suprapatellar pouch, lies deep to the quadriceps muscle.

There is little congruency between the articular surfaces of the tibia and femur; as a result, there is a well developed system of ligaments to give the knee stability, and an arrangement of intra-articular menisci to reduce the contact loadings between femur and tibia.

Ligaments

During the last 10° or so of knee extension the ligaments of the joint are twisted taut as a result of medial rotation (8) of the femur on the tibia; at the start of flexion, this tightening is undone by lateral rotation of the femur, aided by contraction of the popliteus muscle.

Menisci

In plan view the medial (m) and lateral (l) menisci are C-shaped; they are triangular in cross-section, and formed from dense avascular fibrous tissue. Their extremities (horns) (9) are attached to the upper surface of the tibia on which they lie; the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus has an additional attachment (10) to the femur, whereas both anterior horns are loosely connected (11). The concave margin (12) of each meniscus is unattached; the convex margin of the lateral meniscus is anchored to the tibia by coronary ligaments (13), whereas the corresponding part of the medial meniscus is attached to the joint capsule (14) and thereby loosely united to both femur and tibia.

During extension of the knee (15) the menisci slide forwards (16) on the tibial plateau and become progressively more compressed, adapting in shape to the altering contours of the particular portions of the femur and tibia between which they come to lie.

Only the peripheral edges of the menisci have an appreciable blood supply, so that meniscal tears that involve the more central portions have a poor potential for healing.

Bursae

Numerous bursae have been described round the knee, but from the practical point of view only a few are of any real significance.

Bursal enlargements may be encountered in the popliteal fossa, and these are generally referred to as Baker’s cysts or enlarged semimembranosus bursae. Some are found to communicate with the knee joint (sometimes with a valve-like mechanism), and tend to keep pace in terms of distension with any effusion in the knee.

Others are quite unconnected with the joint. The anatomical explanation is that although the semimembranosus bursa (SM) itself never communicates with the knee, it is often connected to the bursa (G) under the medial head of gastrocnemius, which does.

Swelling of the Knee

The knee may become swollen as a result of the accumulation within the joint cavity of excess synovial fluid, blood or pus (synovitis, haemarthrosis, pyarthrosis). Much less commonly, the knee swells beyond the limits of the synovial membrane. This is seen in soft tissue injuries of the knee, when haematoma formation and oedema may be extensive. It is also a feature of fractures, infections and tumours of the distal femur, where confusion may result either from the proximity of the lesion to the joint or because it involves the joint cavity directly. Although primary tumours of the knee are rare, in malignant synovioma there is striking swelling of the joint, and this often extends beyond the limits of the synovial cavity.

Synovitis, Effusion

The synovial membrane secretes the synovial fluid of the joint; excess synovial fluid indicates some affection of the membrane. Joint injuries cause synovitis by tearing or stretching the synovial membrane. Infections act directly by eliciting an inflammatory response which causes the synovial membrane to secrete more fluid. The membrane itself becomes thickened and its function disturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and villonodular synovitis; both conditions are usually accompanied by large effusions. In long-standing meniscus lesions and in osteoarthritis of the knee the synovial membrane may not be directly affected, and consequently no effusion may be present in either of these conditions. Minor injuries of the knee which do not materially damage any of the main structural elements are in some cases followed by rather persistent effusions (traumatic synovitis). In spite of these exceptions, the recognition of fluid in the joint is of great importance. Effusion indicates damage to the joint, and the presence of a major lesion must always be eliminated. A tense synovitis may be aspirated to relieve discomfort.

Haemarthrosis

Blood in the knee is seen most commonly following acute injuries where there is tearing of vascular structures. The menisci are avascular, and there may be no haemarthrosis when a meniscus is torn. Bleeding into the joint will take place, however, if the meniscus has been detached at its periphery, or if there is accompanying damage to other structures within the knee (e.g. the cruciate ligaments). In injuries of the medial ligament, a haematoma may track distally without involvement of the joint cavity. Nevertheless, the presence of a haemarthrosis generally indicates a substantial injury to the joint and is a serious finding. Its physical presence alone may give rise to great discomfort and make diagnosis of its underlying cause rather difficult. In view of this a tense, painful haemarthrosis should be aspirated.

Pyarthrosis

Infections of the knee joint are rather uncommon, and usually bloodborne. Sometimes the joint is involved by direct spread from an osteitis of the femur or tibia; rarely the joint becomes infected following surgery or penetrating wounds.

In acute pyogenic infections the onset is usually rapid and the knee very painful; swelling is tense, tenderness is widespread, and movement resisted. There is pyrexia and general malaise. Pyogenic infections occurring in patients already suffering from rheumatoid arthritis often have a much slower onset. Although the joint is invariably swollen, other inflammatory changes are often suppressed, especially if the patient is receiving steroids.

Tuberculous infections of the knee, now uncommon in the UK, have a slow onset spread over weeks. The knee appears small and globular, with the associated profound quadriceps wasting contributing to this appearance.

In gonococcal arthritis, great pain and tenderness, often apparently out of proportion to the local swelling and other signs, are the striking features of this condition.

When pus is suspected in a joint, aspiration should always be carried out to empty it and obtain specimens for bacteriological examination. If tuberculosis is suspected, synovial biopsy to obtain specimens for culture and histology is required. All knee infections are treated by splintage and an appropriate antibiotic regimen.

Extensor Mechanism of the Knee

Extension of the knee is produced by the quadriceps muscle acting through the quadriceps ligament, patella, patellar ligament and tibial tubercle. Weakness of extension leads to instability, repeated joint trauma and effusion. There is often a vicious circle of pain → quadriceps inhibition → quadriceps wasting → knee instability → ligament stretching and further injury → pain. Loss of full extension also leads to instability, as there is failure of the screwhome mechanism which tightens the ligaments of the joint at terminal extension.

Rapid wasting of the quadriceps is seen in all painful and inflammatory conditions of the knee. Weakness of the quadriceps is also sometimes found in lesions of the upper lumbar intervertebral discs, as a sequel to poliomyelitis, in multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders, and in the myopathies. Difficulty in diagnosis is common when the wasting is the presenting feature of a diabetic neuropathy or secondary to femoral nerve palsy from an iliacus haematoma. Maintenance of good quadriceps tone and breaking the quadriceps vicious circle is an essential part of the treatment of virtually all conditions affecting the knee joint.

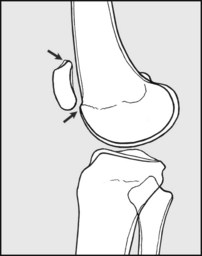

Disruption of the extensor mechanism of the knee is seen in a number of conditions. Fractures of the patella seldom give difficulty in diagnosis provided the appropriate radiographs are taken. Ruptures of the quadriceps tendon or patellar ligament result from sudden, violent contraction of the quadriceps and are seen in the middle-aged when there has been some accompanying degenerative change in the structures involved. Avulsion of the tibial tuberosity may also be seen as a result of a sudden muscle contraction. All these acute conditions are generally treated surgically.

There are a number of conditions short of disruption which may affect the patellar ligament and its extremities, with the generic title of jumper’s knee. In the Sinding–Larsen–Johansson syndrome, seen in children in the 10–14-year age group, there is aching pain in the knee associated with X-ray changes in the distal pole of the patella. Osgood–Schlatter’s disease (which is often thought to be due to a partial avulsion of the tuberosity) occurs in the 10–16 age group. There is recurrent pain over the tibial tuberosity, which becomes tender and prominent. Radiographs may show partial detachment or fragmentation of the tuberosity. Pain usually ceases with closure of the epiphysis, and the management is usually conservative. In an older age group (16–30) the patellar ligament itself may become painful and tender. This almost invariably occurs in athletes, and there may be a history of giving—way of the knee. CT scans may show changes in the patellar ligament, which becomes expanded centrally. Exploration and incision of the patellar ligament is usually advised. Rarely, pain and tenderness may occur proximal to the upper pole of the patella in quadriceps tendinitis.

Ligaments of the Knee

The cruciate, collateral, posterior and capsular ligaments, and the menisci, form an integrated stabilising system which prevents the tibia from shifting or tilting under the femur in an abnormal fashion. The pathological movements that may occur after ligamentous injury are (a) tilting of the knee into varus or valgus, (b) shifting of the tibia directly forwards or backwards (anterior or posterior translation), and (c) rotation of the tibia under the femur so that the medial or lateral tibial condyle subluxes forwards or backwards.

Ligament injuries are important to detect as they may account for appreciable disability, in the form of incidents of giving way of the joint, recurrent effusion, lack of confidence in the knee, difficulty in undertaking strenuous or athletic activities, and sometimes trouble in using stairs or walking on uneven ground.

The diagnosis and interpretation of instability in the knee is difficult and somewhat controversial, for the following reasons:

The Medial Ligament and Capsule

The medial ligament stretches between the femur and the tibia and has both superficial and deep layers. Considerable violence (usually in the form of a valgus strain or a blow on the lateral side of the knee) is required to damage the medial ligament. When the forces are moderately severe a few fibres only may be torn, usually near the upper attachment (sprain of the medial ligament). Then, when the knee is examined clinically, no instability will be demonstrated, but stretching the ligament will cause pain. Minor tears of the medial ligament may be followed eventually by calcification in the accompanying haematoma, and this may give rise to sharply localised pain at the upper attachment (Pellegrini–Stieda disease).

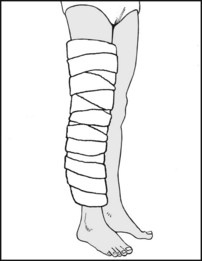

With greater violence the whole of the deep part of the ligament ruptures, followed in order by the superficial part, the medial capsule, the posterior ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament, and sometimes finally the anterior cruciate ligament. Acute complete tears give rise to serious instability in the knee, which can move or be moved into valgus. They are usually dealt with by immediate surgical repair. Partial tears do well by immobilisation for 6 weeks in a pipe-stem plaster. Chronic lesions may be accompanied by tibial condylar subluxation (see later), although there is some doubt as to whether this is indeed possible without there being some additional damage to the anterior cruciate ligament. Surgical treatment may be indicated for such instability. Medial ligament tears may accompany fractures of the lateral tibial table, which will require additional attention.

The Lateral Ligament and Capsule

This ligament may be damaged by blows on the medial side of the knee, throwing it into varus. It most frequently tears at its fibular attachment. As in the case of the medial ligament, increasing violence will lead to tearing of the posterior capsular ligament and the cruciates. In addition, the common peroneal nerve may be stretched and sometimes irreversibly damaged. These injuries are usually treated by operative repair and, where applicable, exploration of the common peroneal nerve. Again, any associated fracture of the medial tibial table may require attention. Chronic lesions may be associated with tibial condylar subluxations.

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Impaired anterior cruciate ligament function is seen most frequently in association with tears of the medial meniscus. In some cases this is due to progressive stretching and attrition rupture of the ligament. (This may occur if an attempt is made to obtain full extension in a knee blocked by a meniscal fragment.) In others, the anterior cruciate ligament tears at the same time as the meniscus, and in the most severe injuries the medial ligament may also be affected (O’Donoghue’s triad).

Isolated ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament are uncommon and are not usually treated surgically unless accompanied by avulsion of bone at the anterior tibial attachment, or if there is a strongly positive pivot shift test.

When the tear is acute and accompanies a meniscal lesion, the meniscus is preserved if at all possible to reduce the risks of tibial subluxation and secondary osteoarthritic change, although the damage may be such that excision cannot be avoided. After attention to the meniscus, many would then advocate direct repair of the anterior cruciate ligament, supplemented by a ligament reinforcement or a reconstruction procedure (e.g. using part of the patellar ligament and its bony attachments). When an acute anterior cruciate tear is associated with damage to the medial or, less commonly, the lateral collateral ligament, a similar approach may be employed.

Chronic anterior cruciate ligament laxity generally results from old injuries, and may cause problems from acute, chronic or recurrent tibial subluxations. There may be a history of giving way of the knee, episodic pain and functional impairment. There is often quadriceps wasting and effusion, and secondary osteoarthritis may develop. Intense quadriceps and hamstring muscle building is usually advised as a first measure. In resistant cases, a ligament reconstruction may be advocated. There is no doubt that these procedures are often initially very successful, but in some the long-term results are disappointing.

The Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Posterior cruciate ligament tears are produced when in a flexed knee the tibia is forcibly pushed backwards (as, for example, in a car accident when the upper part of the shin strikes the dashboard). Most advise immediate surgical repair if the injury is seen at the acute stage, as persisting instability and osteoarthritis are common sequelae in the untreated case.

Rotatory Instability of the Knee: Tibial Condylar Subluxations

In this group of conditions, when the knee is stressed the tibia may sublux forwards or backwards on either the medial or lateral side, giving rise to pain and a feeling of instability in the joint. The main forms are as follows:

1. The medial tibial condyle subluxes anteriorly (anteromedial rotatory instability). In the most severe cases this occurs as a result of tears of both the anterior cruciate ligament and the medial structures (medial ligament and capsule). The medial meniscus may also be damaged and contribute to the instability. In the less severe cases there is some controversy regarding which structures may be spared. Clinically, the condition should be suspected on the evidence of the anterior drawer and Lachman tests, and the demonstration of instability on applying a valgus stress to the joint.

2. The lateral tibial condyle subluxes anteriorly (anterolateral rotatory instability). In the more severe cases the anterior cruciate ligament and the lateral structures are torn, and there may be an associated lesion of the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus. It may be diagnosed from the results of the anterior drawer and Lachman tests, and by demonstrating instability on applying a varus stress to the knee, although a number of specific tests may afford additional confirmation.

3. The lateral tibial condyle subluxes posteriorly (posterolateral rotatory instability). This may follow rupture of the lateral and posterior cruciate ligaments, and be recognised by the presence of instability in the knee on applying varus stress, in combination with eliciting an abnormal posterior drawer test. There are also specific tests for this instability.

4. Combinations of these lesions (particularly 1 and 2, and 2 and 3) may be found, especially where there is major ligamentous disruption of the knee.

Where symptoms are demanding, and when a firm diagnosis has been established, the stability of the joint may be restored by an appropriate ligamentous reattachment or reconstruction procedure.

Lesions of the Menisci

Congenital Discoid Meniscus

This abnormality, most frequently involving the lateral meniscus, commonly gives rise to presenting symptoms in childhood. The meniscus has not its usual semilunar form but is D-shaped, with its central edge extending in towards the tibial spines. It may produce a very pronounced clicking from the lateral compartment, a block to extension of the joint, and other derangement signs. It is usually treated by excision.

Meniscus Tears in the Young Adult

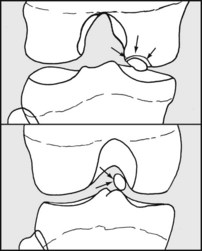

The commonest cause is a sporting injury, when a twisting strain is applied to the flexed, weightbearing leg. The trapped meniscus commonly splits longitudinally, and its free edge may displace inwards towards the centre of the joint (bucket-handle tear). This prevents full extension (with physiological locking of the joint), and if an attempt is made to straighten the knee a painful elastic resistance is felt (’springy block to full extension’). In the case of the medial meniscus, prolonged loss of full extension may lead to stretching and eventual rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.

The aim in treating meniscal tears is to correct the mechanical problems that they have created within the joint, while if at all possible preserving as much of each meniscus as is possible; this, it is thought, will reduce the risks of instability and the onset of secondary osteoarthritis. In many cases the torn part of the meniscus (e.g. the handle of a bucket-handle tear) only is excised, but some major meniscal tears may require total meniscectomy. In peripheral detachments and certain other lesions, particularly those near the periphery of the meniscus, repair by direct suture or other measures is sometimes attempted. Many surgical procedures are performed arthroscopically, thereby facilitating early recovery.

Degenerative Meniscus Lesions in the Middle-Aged

Loss of elasticity in the menisci through degenerative changes associated with the ageing process may give rise to horizontal cleavage tears within the substance of the meniscus; these tears may not be associated with any remembered traumatic incident, and sharply localised tenderness in the joint line is a common feature. In an appreciable number of cases symptoms may resolve without surgery, although this may sometimes be required.

Cysts of the Menisci

Ganglion-like cysts occur in both menisci, but are much more common in the lateral. Medial meniscus cysts must be carefully distinguished from ganglions arising from the pes anserinus (the insertion of sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus). In true cysts there is often a history of a blow on the side of the knee over the meniscus. They are tender, and as they restrict the mobility of the menisci they render them more susceptible to tears. They are generally treated by excision, and sometimes simultaneous meniscectomy may be required, especially if there are problems with recurrence. Some workers believe that all meniscal cysts have an associated tear, and prefer to deal with the problem by arthroscopic resection of the tear and simultaneous decompression of the cyst through the substance of the meniscus.

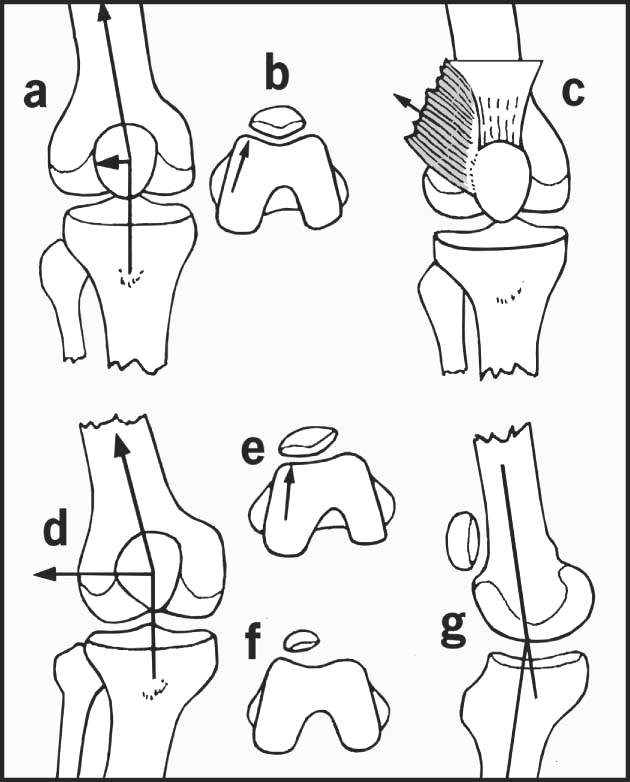

Patellofemoral Instability

The patella has always a tendency to lateral dislocation as the tibial tuberosity lies lateral to the dynamic axis of the quadriceps (Fig. 10.B); any tightness in the extensor mechanism (e.g. from quadriceps contractions or fibrosis) generates a lateral component of force that tends to displace the patella laterally. Normally, at the beginning of knee flexion the patella engages in the groove separating the two femoral condyles (the trochlea), and this keeps it in place as flexion continues. This system may be disturbed in a number of ways. The side thrusts that tend to cause the patella to sublux laterally may be increased by an abnormal lateral insertion of the quadriceps, tight lateral structures, or by increases in the angle between the axis of the quadriceps and the line of the patellar ligament (e.g. as a result of knock-knee deformity, or by a broad pelvis). The lateral condyle which supports and guides the patella may be deficient, or the patella itself may be small and poorly formed (hypoplasia). If the patella is highly placed (patella alta) it may fail to engage in the condylar groove at the beginning of flexion. (This condition is often associated with genu recurvatum.) Medial to the patella the soft tissues that would normally help prevent an abnormal lateral excursion of the patella may be deficient, sometimes as a result of stretching from previous dislocations.

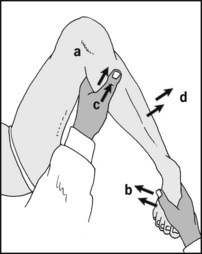

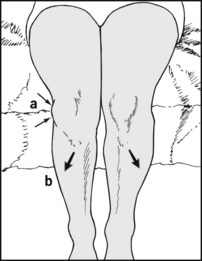

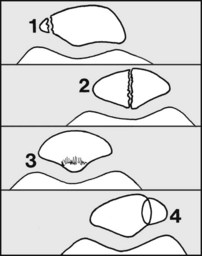

Fig. 10.B. Some factors relating to patellar instability. Because the quadriceps and the patellar ligament meet at an angle (Q angle) there is a lateral component of force when the quadriceps contracts, and this tends to dislocate the patella laterally (a). This is resisted by the femoral sulcus in which the patella lies, and the prominence of the lateral femoral condyle (b). This mechanism may be interfered with by an abnormal lateral insertion of the quadriceps (c), or an increase in the Q angle (e.g. in knock knee) (d). The lateral femoral condyle may be hypoplastic and the condylar sulcus shallow (e); or the patella itself may be hypoplastic (f). The patella may be highly placed, especially in genu recurvatum (g), so that it fails to engage in the condylar gutter.

There are a number of conditions characterised by loss of normal patellar alignment.

Acute traumatic dislocation of the patella

This injury occurs most frequently in adolescent females during athletic activity (e.g. playing hockey). There may be a history of a direct blow on the inside of the knee. The patella dislocates laterally and causes a striking deformity, which has often reduced by the time the patient is first seen. If still displaced it is reduced, and a period of fixation in a cylinder plaster is usually advised in all cases. Some advocate exploration, with reefing of the medial structures and release of those on the lateral side.

Recurrent lateral dislocation

Further painful dislocations of the patella occur, often with increasing frequency and ease. Surgical stabilisation is usually advised in the well established case, to reduce the risks of secondary patellofemoral osteoarthritis and prevent the danger that the patient might be exposed to should the dislocation occur in a hazardous situation. The type of procedure carried out is aimed at correcting the underlying defect, which should be established by investigation.

Congenital dislocation of the patella

The patella may be dislocated at birth in association with congenital abnormalities. The dislocation is irreducible. Surgical correction is difficult, and the results often poor.

Habitual dislocation of the patella

The patella dislocates every time the knee flexes, and this is pain free. It often arises in childhood and may be due to an abnormal attachment of the iliotibial tract. In a number of cases in the neonatal period it results from fibrosis in a quadriceps muscle which has been used for intramuscular injections. The condition also occurs in joint laxity syndromes. In the established case there is usually a severe associated deficiency of the trochlea. It may be treated by extensive lateral releases, medial reefing, and sometimes transposition of the tibial tubercle.

Retropatellar/Anterior Knee Pain Syndromes/Chondromalacia Patellae

These are characterised by chronic ill-localised pain at the front of the knee, often made worse by prolonged sitting, or walking on slopes or stairs. It is commonest in females in the 15–35-year age group, and the pathology is often uncertain. In some there is softening or fibrillation of the articular cartilage lining the patella (chondromalacia patellae), and some of these cases progress to develop clear patellofemoral osteoarthritis.

Those suffering from retropatellar knee pain (anterior knee pain) may be divided into two groups: in one no significant cause can be found, whereas in the other there is evidence of patellar malalignment. In this latter group some of the factors responsible for recurrent dislocation may be found to be present (even although there may be no history of frank dislocation). Although symptoms are often prolonged, they are usually not severe and may be dealt with by restriction of the activities known to aggravate the symptoms, and by physiotherapy. In some cases, where symptoms are particularly severe and unresponsive, and where there is evidence of malalignment, lateral release and patellar debridement procedures are often practised. Where the articular surface of the patella is seriously involved, patellectomy is sometimes advocated. Anterior knee pain was once thought to be associated with excessive foot pronation, but this is no longer considered to be the case.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

This occurs most frequently in males in the second decade of life, and most commonly involves the medial femoral condyle. Possibly as a result of impingement against the tibial spines or the cruciate ligaments, a segment of bone undergoes avascular necrosis, and a line of demarcation becomes established between this area and the underlying healthy bone. Complete separation may occur so that a loose body is formed. The symptoms are initially of aching pain and recurring effusion, with perhaps locking of the joint if a loose body is present. Good results generally follow conservative treatment with quadriceps exercises and continued weightbearing if the condition is found before epiphyseal closure. If the fragment becomes loose, it should be fixed surgically. If the lesion is long standing, with a fragment smaller than its crater, it should be excised. The cavity may be drilled in an attempt to encourage vascularisation of its base. In all cases the damaging effects of a loose body must be prevented.

Fat Pad Injuries

The infrapatellar fat pads may become tender and swollen and give rise to pain on extension of the knee, especially if they are nipped between the articulating surfaces of femur and tibia. This may occur as a complication of osteoarthritis, but is seen more frequently in young women when the fat pads swell in association with premenstrual fluid retention. Excision of the pads may be required to relieve the symptoms.

Loose Bodies

Loose bodies are seen most frequently as a sequel to osteoarthritis or osteochondritis dissecans. Much less commonly, numerous loose bodies are formed by an abnormal synovial membrane in the condition of synovial chondromatosis. Loose bodies are treated by excision, but synovectomy may be required in synovial chondromatosis if massive recurrence is to be avoided.

Affections of the Articular Surfaces

Osteoarthritis (Osteoarthrosis)

The stresses of weight-bearing mainly involve the medial compartment of the knee, and it is in this area that primary osteoarthritis usually first occurs. This is an exceedingly common condition, arising without any obvious previous pathology in the joint. Overweight, the degenerative changes accompanying old age, and overwork are common factors. Secondary osteoarthritis may follow ligament and meniscus injuries, recurrent dislocation of the patella, osteochondritis dissecans, joint infections and other previous pathology. It is seen in association with knock-knee and bow-leg deformities, which throw additional mechanical stresses on the joint.

In osteoarthritis the articular cartilage undergoes progressive change, flaking off into the joint and thereby producing the narrowing that is a striking feature of radiographs of this condition. The subarticular bone may become eburnated, and often small marginal osteophytes and cysts are formed. Exposure of bone and free nerve endings gives rise to pain and crepitus on movement. Distortion of the joint surfaces is one cause of progressive loss of movement and fixed flexion deformities. Treatment is generally conservative, by quadriceps exercises, short-wave diathermy, analgesics and weight reduction. Surgery may be considered in severe cases. The procedures available include joint replacement, osteotomy (especially in cases of genu varum and valgum) and arthrodesis.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Characteristically the knee is warm to touch, there is effusion, limitation of movements, muscle wasting, synovial thickening, tenderness and pain. Fixed flexion, valgus and (less commonly) varus deformities are quite common. Generally other joints are also involved, although the monoarticular form is occasionally seen. Active cases are often treated by synovectomy in an attempt to avoid or delay the progress of the condition. An acute flare-up of symptoms may be treated by temporary splintage. Either joint replacement, osteotomy or arthrodesis may be considered in well selected cases.

Reiter’s Syndrome

This usually presents as a chronic effusion accompanied by discomfort in the joint. It is often bilateral, with an associated conjunctivitis. There is often a history of urethritis or colitis.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

The first symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis are generally in the spine, but occasionally the condition presents at the periphery, with swelling and discomfort in the knee joint. Stiffness of the spine and radiographic changes in the sacroiliac joints are nevertheless almost invariably present.

Disturbances of Alignment

Genu Varum (Bow Leg)

This commonly occurs as a growth abnormality of early childhood, and usually resolves spontaneously. Rarely genu varum is caused by a growth disturbance involving both the tibial epiphysis and the proximal tibial shaft (tibia vara), and treatment by osteotomy may be required. In adults this deformity most frequently results from osteoarthritis, where there is narrowing of the medial joint compartment. It also occurs in Paget’s disease and rickets. It is less common in rheumatoid arthritis unless secondary osteoarthritic changes supervene in that condition.

Genu Valgum (Knock Knee)

This is seen most often in young children, where it is usually associated with flat foot. Nearly all cases resolve spontaneously by the age of 6. It is also seen in the plump adolescent girl, and it may be a contributory factor in recurrent dislocation of the patella. In adults it most frequently occurs as a result of the bone softening and ligamentous stretching accompanying rheumatoid arthritis. It occurs after uncorrected depressed fractures of the lateral tibial table, and as a sequel to a number of paralytic neurological disorders where there is ligament stretching and altered epiphyseal growth. Selected cases may be treated by corrective osteotomy.

Genu Recurvatum

Hyperextension at the knee is seen after ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament and in girls where the growth of the upper tibial epiphysis may be retarded from much pointe work in ballet classes or from the wearing of high-heeled shoes in early adolescence. In the latter cases there is corresponding elevation of the patella (patella alta) contributing to a tendency to recurrent dislocation. More rarely, the deformity is seen in congenital joint laxity, poliomyelitis and Charcot’s disease.

Bursitis

Cystic swelling occurring in the popliteal region in both sexes is usually referred to as enlargement of the semimembranosus bursa. In fact, several of the bursae known to the anatomist may be involved, either singly or together. The swelling sometimes communicates with the knee joint and may fluctuate in size. Rupture may lead to the appearance of bruising on the dorsum of the foot, and this may help to distinguish it from deep venous thrombosis or cellulitis. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, or if the swelling is persistent and producing symptoms, excision is advised.

Fluctuant bursal swellings may also occur over the patella (prepatellar bursitis or housemaid’s knee) or the patellar ligament (infrapatellar bursitis or clergyman’s knee). Chronic prepatellar bursitis, with or without local infection, is common in miners, where it is referred to as ‘beat knee’; it is also associated with other occupations where prolonged kneeling is unavoidable (e.g. it is common in plumbers and carpet layers). If the swelling is bulky or tense it is aspirated; recurrent swellings, if troublesome, are excised.

How to Diagnose a Knee Complaint

1. Note the patient’s age and sex, bearing in mind the following important distribution of the common knee conditions (Table 10.1).

| Age group | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 0–12 | Discoid lateral meniscus | Discoid lateral meniscus |

| 12–18 | Osteochondritis dissecans | First incidents of recurrent dislocation of the patella |

| Osgood–Schlatter’s disease | Osgood–Schlatter’s disease | |

| 18–30 | Longitudinal meniscus tears | Recurrent dislocation of the patella |

| Chondromalacia patellae | ||

| Fat pad injury | ||

| 30–50 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 40–55 | Degenerative meniscus lesion | Degenerative meniscus lesion |

| 45+ | Osteoarthritis | Osteoarthritis |

Infections are comparatively uncommon and occur in both sexes in all age groups.

Reiter’s syndrome occurs in adults of both sexes; ankylosing spondylitis nearly always occurs in adult males. Both are comparatively rare.

Ligamentous and extensor apparatus injuries occur in both sexes, but are rare in children.

2. Find out if the knee swells. An effusion indicates the presence of pathology, which must be determined. (Note, however, that the absence of effusion does not necessarily eliminate significant pathology.)

3. Try to establish whether there is a mechanical problem (internal derangement) accounting for the patient’s symptoms. Do this by:

In a high proportion of cases the likely diagnosis will have been established by this stage, requiring only confirmation by clinical examination.

Additional Investigations

Occasionally a firm diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of the history and clinical examination alone. The following additional investigations are often helpful.

Suspected internal derangement

Suspected tuberculosis of the knee

Further investigation of severe undiagnosed pain

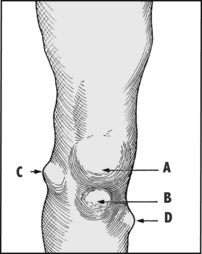

Note the presence of swelling confined to the limits of the synovial cavity and suprapatellar pouch, suggesting effusion, haemarthrosis, pyarthrosis or a space-occupying lesion in the joint.

Note whether the swelling extends beyond the limits of the joint cavity, suggesting infection (of the joint, femur or tibia), tumour or major injury.

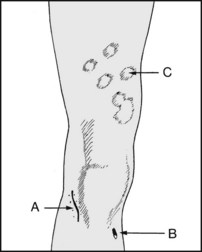

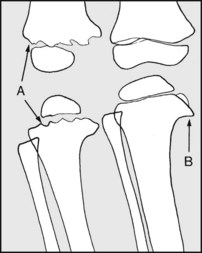

Note presence of localised swellings, e.g. (A) prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee), (B) infrapatellar bursitis (clergyman’s knee), (C) meniscus cyst (in joint line), (D) diaphyseal aclasis (exostosis, often multiple and sometimes familial). In beat knee (a common affliction in miners) there is chronic anterior bursal enlargement, often with thickening of the overlying skin.

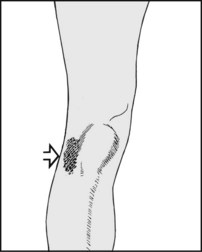

Note any bruising which suggests trauma to the superficial tissues or knee ligaments. Note that bruising is not usually seen in meniscus injuries. Note any redness suggesting inflammation.

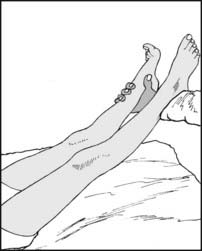

Note (A) scars due to previous injury or surgery: the relevant history must be obtained. (B) Sinus scars are indicative of previous infections, often of bone, and with the potential for reactivation. (C) Evidence of psoriasis, with the possibility of psoriatic arthritis.

Note any increased local heat and its extent, suggesting in particular rheumatoid arthritis or infection. There may also be increased local heat as part of the inflammatory response to injury, and in the presence of rapidly growing tumours. Always compare the two sides.

A warm knee and cold foot suggest a popliteal artery block. Always make allowance for any warm bandage the patient may have been wearing just prior to the examination, and check the peripheral pulses.

Inspect the relaxed quadriceps muscle. Slight wasting and loss of bulk are normally apparent on careful inspection.

Examine the contracted quadriceps. Place a hand behind the knee and ask the patient to press the leg against the hand. Feel the muscle tone with your free hand.

Repeat the last test, this time asking the patient to dorsiflex the inverted foot. This demonstrates the important vastus medialis portion of the quadriceps, which may be involved in recurrent dislocation of the patella.

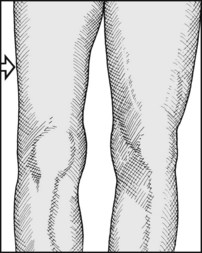

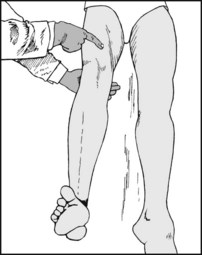

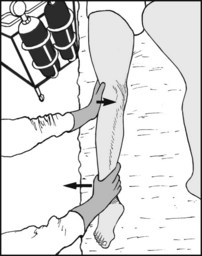

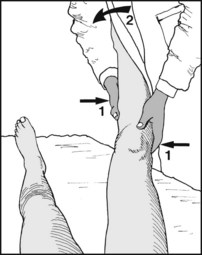

Substantial wasting, especially in the fat leg, may be confirmed by measurement, assuming the other limb is normal. This test, being objective, may be valuable for repeat assessments and in medicolegal cases. Begin by locating the knee joint (see later for details) and marking it with a ballpoint pen. Make a second mark on the skin 18 cm above this. Repeat on the other leg.

Compare the circumference of the legs at the marked levels. Wasting of the quadriceps occurs most frequently as the result of disuse, generally from a painful or unstable lesion of the knee, or from infection or rheumatoid arthritis.

10.13. Extensor apparatus (1):

Loss of active extension of the knee (excluding paralytic conditions) follows (1) rupture of the quadriceps tendon, (2) many patellar fractures, (3) rupture of the patellar ligament, (4) avulsion of the tibial tubercle.

10.14. Extensor apparatus (2):

With the patient sitting with his legs over the end of the examination couch, ask him to straighten the leg while you support the ankle with one hand. Feel for quadriceps contraction and look for active extension of the limb.

10.15. Extension apparatus (3):

Note the position of the patella in relation to the joint line and the tibial tuberosity. If its upper border is high, this suggests that it is proximally displaced and that you should suspect lesions 2, 3 or 4.

10.16. Extensor apparatus (4):

If the patella is normally placed, lay a finger along its upper border. Loss of normal soft tissue resistance is suggestive of a rupture of the quadriceps tendon (1).

10.17. Extensor apparatus (5):

Look for gaps and tenderness at the other levels to help differentiate between lesions 2, 3 and 4. Radiographs of the knee are essential.

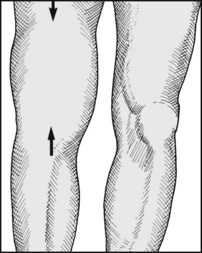

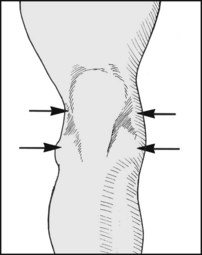

Small effusions are detected most easily by inspection. The first signs are bulging at the sides of the patellar ligament and obliteration of the hollows at the medial and lateral edges of the patella.

With greater effusion into the knee the suprapatellar pouch becomes distended. Effusion indicates synovial irritation from trauma or inflammation.

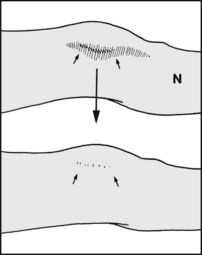

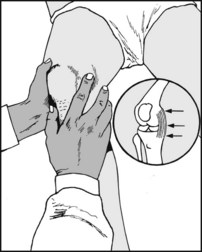

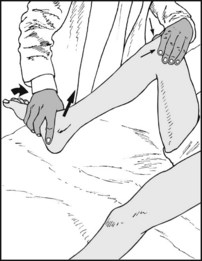

10.20. Effusion (3): patellar tap test (ballottement test) (1):

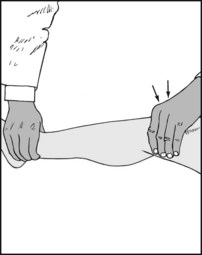

Squeeze any excess synovial fluid out of the suprapatellar pouch with the index and thumb, slid firmly distally from a point about 15 cm above the knee to the level of the upper border of the patella. This will also ‘float’ the patella away from the femoral condyles.

10.21. Effusion (4): patellar tap test (2):

Place the tips of the thumb and three fingers of the free hand squarely on the patella, and jerk it quickly downwards towards the femur. A click as the patella strikes the condyles indicates the presence of effusion. Note that if the patella is not properly steadied as described it will tilt, giving a false negative. Note too that if the effusion is slight or tense, the tap test will be negative.

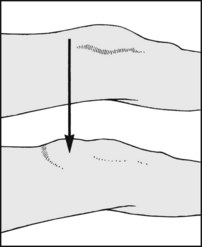

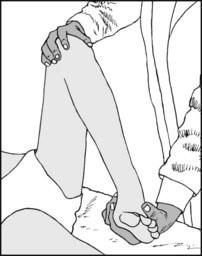

10.22. Effusion (5): fluid displacement test (1):

Small effusions may be detected by this manoeuvre. Evacuate the suprapatellar pouch as in the patellar tap test before.

10.23. Effusion (6): fluid displacement test (2):

Stroke the medial side of the joint to displace any excess fluid in the main joint cavity to the lateral side of the joint.

10.24. Effusion (7): fluid displacement test (3):

Now stroke the lateral side of the joint while watching the medial side closely. Any excess fluid present will be seen to move across the joint and distend the medial side. This test will be negative if the effusion is gross and tense.

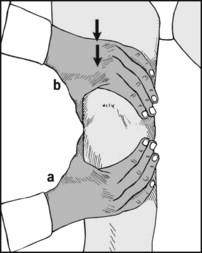

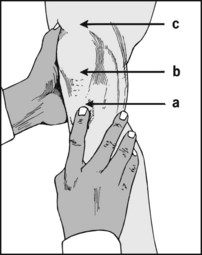

10.25. Effusion (8): palpable fluid wave test:

This can be useful in testing for larger effusions, especially in fat knees. With the thumb on one side of the joint and the fingers on the other (a), compress the knee to empty the hollows at the side of the joint. Now, with the other hand attempt to force fluid from the suprapatellar pouch distally into the knee (b). The force of any fluid being transmitted should be picked up by the compressing hand.

A haemarthrosis is a sign of major joint pathology, is usually obvious within half an hour of injury, and gives a doughy feel in the suprapatellar region. A tense haemarthrosis should be aspirated to relieve pain and permit a more thorough clinical (and usually) arthroscopic examination.

Tenderness in pyarthrosis is usually widespread. There is generally a severe systemic upset, and quadriceps wasting. If pyarthrosis is suspected, the knee should always be aspirated to relieve painful and destructive joint pressure, and to obtain pus for elucidating the infecting agent and establishing antibiotic sensitivities.

Pick up the skin and the relaxed quadriceps tendon to assess the thickness of the synovial membrane in the suprapatellar pouch. The synovial membrane is thickened in inflammatory conditions, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, and in villonodular synovitis.

It is first essential to identify the joint line quite clearly. Begin by flexing the knee and looking for the hollows at the sides of the patellar ligament; these lie over the joint line. Then confirm this by feeling with the fingers or thumb for the soft hollow of the joint. When the examining finger is moved proximally it should rise out of the joint hollow on to the femoral condyle; similarly, when moved distally it should ride over the eminence of the tibia.

10.30. Tenderness (2): joint line structures:

Begin by palpating carefully from in front back along the joint line on each side. Localised tenderness here is commonest in meniscus, collateral ligament and fat pad injuries.

10.31. Tenderness (3): collateral ligaments:

Now systematically examine the upper and lower attachments of the collateral ligaments. Associated bruising and oedema are a feature of acute injuries.

10.32. Tenderness (4): tibial tubercle:

In children and adolescents, tenderness is found over the tibial tubercle (a), which may be prominent in Osgood–Schlatter’s disease, and after acute avulsion injuries of the patellar ligament and its tibial attachment. Tenderness over the lower pole of the patella (b) and proximal patellar ligament is found in Sinding–Larsen–Johansson disease. Tenderness over the quadriceps tendon (c) is found in quadriceps tendinitis.

10.33. Tenderness (5): patellar ligament:

Where in an athletic patient a problem with the patellar ligament is suspected, look for patellar ligament tenderness while the patient is attempting to extend the leg against resistance. This test is best performed with the leg over the end of the examination couch.

10.34. Tenderness (6): femoral condyles: suspected osteochondritis dissecans (1):

Flex the knee fully and look for tenderness over the femoral condyles. Osteochondritis dissecans most frequently involves the medial femoral condyles, and particular attention should therefore be paid to the medial side.

10.35. Suspected osteochondritis dissecans (2): Wilson’s test:

The aim of the test is to cause pressure between the anterior cruciate ligament and the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. Flex the knee (a) and internally rotate the foot (b). Now extend the knee fully (c). If pain occurs at full extension and is relieved by external rotation of the foot, then the test is positive.

10.36. Movements (1): extension:

First make sure that the knee can be fully extended. If in doubt, lift both legs and sight along the good and affected leg. Full extension is recorded as 0°. Loss of full extension may be recorded as ‘The knee lacks X° of extension’.

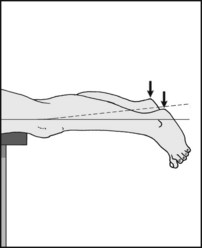

10.37. Movements (2): extension:

If there is still some doubt, examine the patient in the prone position, fully relaxed, and with his legs hanging over the edge of the examination couch. Any loss of extension on one side should be obvious from the position of the heels.

10.38. Movements (3): extension:

Try to obtain full extension if this is not obviously present. A springy block to full extension is very suggestive of a bucket-handle meniscus tear. A rigid block to full extension (commonly described as a fixed flexion deformity) is often present in arthritic conditions affecting the knee.

10.39. Movements (4): hyperextension (genu recurvatum):

This is present if the knee extends beyond the point when the tibia and femur are in line. Attempt to demonstrate this by lifting the leg while at the same time pressing back on the patella. If severe, look for other signs of joint laxity, particularly in the elbow, wrist and fingers, keeping in mind the rare Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

hyperextension, if present, is recorded as ‘X° hyperextension’. It is seen most frequently in girls, and is often associated with a high patella, chondromalacia patellae, recurrent dislocation of the patella, and sometimes tears of the anterior cruciate, medial ligament, or medial meniscus.

10.41. Movements (6): flexion (1):

Measure the range of flexion in degrees, starting from the zero position of normal full extension. Flexion of 135° and over is regarded as normal, but compare the two sides. There are many causes of loss of flexion, the commonest of which are effusion and arthritic conditions.

10.42. Movements (7): flexion (2):

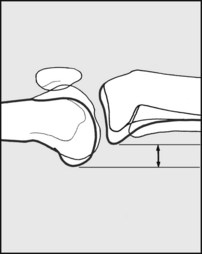

Alternatively, measure the heel-to-buttock distance with the leg fully flexed. This can be a very accurate way of detecting small alterations in the range (1 cm = 1.5° approximately) and is useful for checking daily or weekly progress. Note that obviously flexion can never be greater than when the heel contacts the buttock, and that inability to bring the heel to the buttock is not necessarily an indicator of flexion loss (135° is less than this).

10.43. Movements (8): recording:

The range of movements in the examples illustrated would be recorded as follows: (A) 0–135° (normal range); (B) 5° hyperextension – 140° flexion; (C) 10–60° (or 10° fixed flexion deformity with a further 50° flexion).

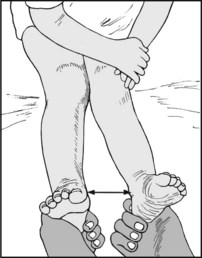

10.44. Genu valgum (knock knee) in children (1):

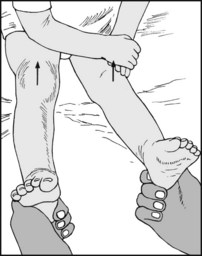

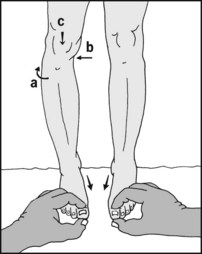

Note whether unilateral or bilateral; the latter is more common. The severity of the deformity is recorded by measuring the intermalleolar gap. Grasp the child by the ankles and rotate the legs until the patellae are vertical.

10.45. Genu valgum in children (2):

Now bring the legs together to touch lightly at the knees, and measure the gap between the malleoli. (Normally the knees and malleoli should touch). Serial measurements, often every 6 months, are used to check progress. Note that with growth a static measurement is an angular improvement. In the 10–16-year age group < 8 cm in females and < 4 cm in males is regarded as normal.

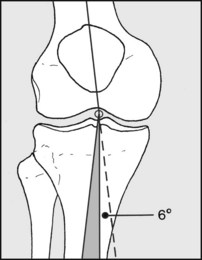

10.46. Genu valgum in adults (1):

In adults the deformity is seen most often in association with rheumatoid arthritis. It is also common in teenage girls. It is best measured by X-rays, and the films should be taken with the patient taking all his weight on the affected side.

10.47. Genu valgum in adults (2):

The degree of valgus may be roughly assessed by measuring the angle formed by the tibial and femoral shafts. Allow for the ‘normal’ angle, which is approximately 6° in the adult. The shaded area represents genu valgum. (Note that the tibiofemoral angle is virtually the same as the Q angle used in the assessment of patellar instability.)

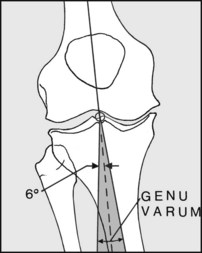

10.48. Genu varum (bow leg) (1):

Measure the distance between the knees, using the fingers as a gauge. Ideally the patient should be weightbearing, and it is essential that both patellae should be facing forwards to counter any effect of hip rotation. In the 10–16-year age group, < 4 cm in females and < 5 cm in males is regarded as being within normal limits.

An assessment of the deformity may also be carried out with X-rays, as in genu valgum, with the patient weightbearing during the exposure of the films. The deformity is seen most commonly in osteoarthritis and Paget’s disease. It may occur in rheumatoid arthritis, although genu valgum is commoner in that condition.

In children, radiography may be helpful. In (A) rickets, note the wide and irregular epiphyseal plates. In (B) tibia vara (Blount’s disease), note the sharply downturned medial metaphyseal border. In the infantile form (under age 4) femoral disturbance is rare. In the late onset type (over 5) femoral varus is present in a number of cases. Note that radiological varus is normal till a child is 18 months old.

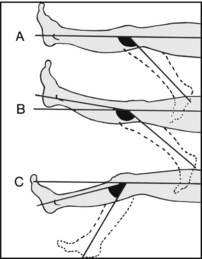

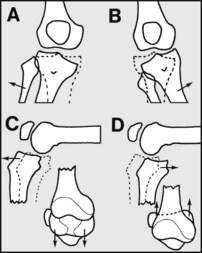

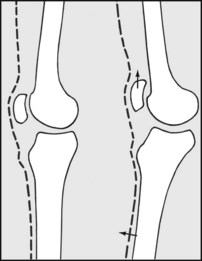

The following potential deformities may be looked for: (A) valgus (when the medial ligament is torn: severe when the posterior cruciate is also damaged); (B) varus (when the lateral ligament is torn: severe when the posterior cruciate is also torn); (C) anterior displacement of the tibia (anterior cruciate tears: worse if medial and/or lateral structures torn); (D) posterior displacement of the tibia (posterior cruciate ligament tears).

10.52. Instability (2): (E) Rotatory:

(1) The medial tibial condyle subluxes anteriorly (anteromedial instability): this is usually due to combined tears of the anterior cruciate and medial structures; (2) the lateral condyle subluxes anteriorly (anterolateral instability): this is usually due to tears of the anterior cruciate plus the lateral structures; (3) the lateral tibial condyle subluxes posteriorly (posterolateral instability) or (4) the medial tibial condyle subluxes posteriorly (posteromedial instability). (3) and (4) are due mainly to tears of the posterior cruciate and lateral or medial structures. (5) Combinations of these instabilities.

10.53. Valgus stress instability (1):

Begin by examining the medial side of the joint, and the medial ligament in particular. Tenderness in injuries of the medial ligament is commonest at the upper (femoral) attachment and in the medial joint line. Bruising may be present after recent trauma, but haemarthrosis may be absent. (Where the medial ligament has been injured and displays tenderness without laxity it may be classified as a grade 1 injury.)

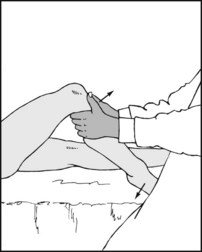

10.54. Valgus stress instability (2):

Extend the knee fully. Use one hand as a fulcrum, and with the other attempt to abduct the leg. Look for the joint opening up and the leg going into valgus. On release of the valgus force a confirmatory clunk may be felt. Moderate valgus is suggestive of a major medial and posterior ligament rupture (grade 2 injury). Severe valgus may indicate additional cruciate (particularly posterior cruciate) rupture (grade 3 injury).

10.55. Valgus stress instability (3):

If in doubt, use the heel of the hand as a fulcrum and use the thumb or index, placed in the joint line, to detect any opening up of the joint as it is stressed. If there is still some uncertainty, compare the two sides.

10.56. Valgus stress instability (4): stress films (1):

If there is still some doubt, then radiographs of both knees should be taken while applying a valgus stress to each joint.

10.57. Valgus stress instability (5): stress films (2):

The films of both sides are then compared. Any instability should be obvious.

10.58. Valgus stress instability (6):

If no instability has been demonstrated with the knee fully extended, repeat the tests with the knee flexed to 20° and the foot internally rotated. Some opening up of the joint is normal, and it is essential to compare the sides. Demonstration of an abnormal amount of valgus suggests less extensive involvement of the medial structures (e.g. partial medial ligament tear, still classified as a grade 2 injury).

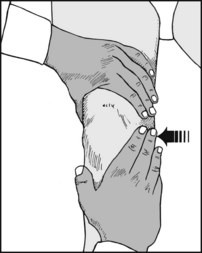

10.59. Valgus stress instability (7):

If the knee is very tender and will not permit the pressure of a hand as a fulcrum, attempt to stress the ligament with this crossover arm grip, with one hand placed over the proximal part of the tibia just distal to the knee joint to avoid any local pressure over the joint and its ligaments.

10.60. Valgus stress instability (8):

If a haemarthrosis is present (and this is not always the case) preliminary aspiration may allow a more meaningful examination of the joint.

10.61. Valgus stress instability (9):

If the knee remains too painful to permit examination, the joint should be fully tested under anaesthesia; there should be provision to carry on with a surgical repair should major instability be demonstrated (i.e. where several major structures are involved), or with an arthroscopy.

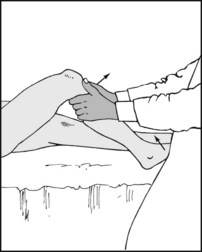

10.62. Varus stress instability (1):

Begin by examining the lateral side of the joint. Tenderness is most common over the head of the fibula or in the lateral joint line in acute injuries of the lateral joint complex (lateral ligament and capsule).

10.63. Varus stress instability (2):

Attempt to produce a varus deformity by placing one hand on the medial side of the joint and forcing the ankle medially. Carry out the test as in the case of valgus stress instability, first in full extension and then in 30° flexion, and compare one side with the other. Note that when testing the lateral ligament, in the normal knee there is a little more ‘give’ than with the medial.

10.64. Varus stress instability (3):

Again, for a more sensitive assessment of ‘give’, the thumb can be placed in the joint line. If there is varus instability in extension as well as flexion, it suggests tearing of the posterior cruciate ligament as well as the lateral ligament complex.

10.65. Varus stress instability (4):

As in the case of valgus stress instability stress films may be taken, and if examination is not possible even after aspiration, arrange to examine the knee under general anaesthesia.

10.66. Varus stress instability (5):

Always check that the patient is able to dorsiflex the foot, to ensure that the motor fibres in the common peroneal nerve (lateral popliteal) have escaped damage.

10.67. Varus stress instability (6):

In addition, test for sensory disturbance in the distribution of the common peroneal nerve.

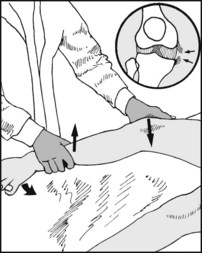

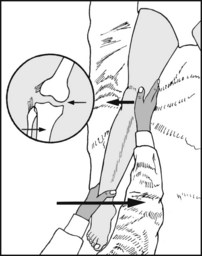

10.68. The anterior drawer test (1):

Flex the knee to 90°, with the foot pointing straight forwards, and steady it by sitting close to it. Grasp the leg firmly with the thumbs on the tibial tubercle. Check that the hamstrings are relaxed, and jerk the leg towards you. Repeat with the knee flexed to 70° and compare the sides. Note: significant displacement (i.e. the affected side more than the other) confirms anterior instability of the knee. Note also that in tears the endpoint of the anterior translation is usually softer and less clearly defined than the firm endpoint when the ligament is intact. When the displacement is marked (say 1.5 cm or more) then the anterior cruciate is almost certainly torn, and there is a strong possibility of associated damage to the medial complex (medial ligament and medial capsule) and even the lateral complex. If the displacement is less marked, and one tibial condyle moves further forward than the other, then the diagnosis is less clear: it may suggest an isolated anterior cruciate ligament laxity or a tibial condylar subluxation (rotatory instability).

10.69. The anterior drawer test (2):

Repeat the test with the foot in 15° of external rotation. Excess excursion of the medial tibial condyle suggests a degree of anteromedial (rotatory) instability, with possible involvement of the medial ligament as well as the anterior cruciate ligament.

10.70. The anterior drawer test (3):

Now turn the foot into 30° of internal rotation and repeat the test. Anterior subluxation of the lateral tibial condyle suggests some anterolateral rotational instability, with possibly damage to the posterior cruciate and the posterior ligament as well as the anterior cruciate ligament.

10.71. The anterior drawer test (4):

Beware of the following fallacy: a tibia already displaced backwards as a result of a posterior cruciate ligament tear may give a false positive in this test. This also applies to the Lachman tests described in the following frames. Check by inspecting the contours of the knee prior to testing.

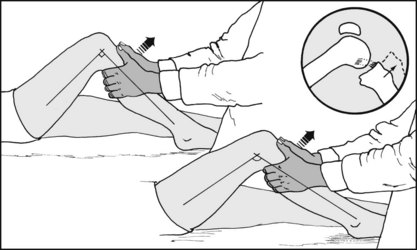

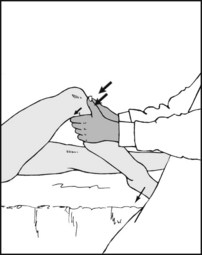

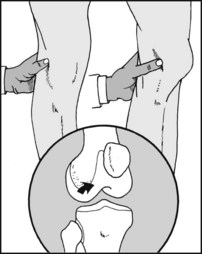

The Lachman tests are also used to detect anterior tibial instability. In the manipulative Lachman test, the knee should be relaxed and in about 15° flexion. One hand stabilises the femur while the other tries to lift the tibia forwards. The test is positive if there is anterior tibial movement (detected with the thumb in the joint), with a spongy endpoint. The test is sometimes easier to perform with the patient prone (see next frame).

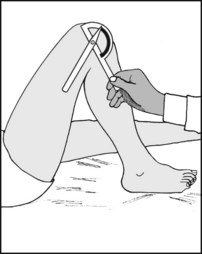

10.73. The Lachman tests (2): the prone test (Feagin and Cooke):

This is especially useful where the patient has large thighs which are difficult to grasp. With the patient prone, encircle the tibia with both hands, placing the index fingers and thumbs in the joint line. Flex the knee to 20° and attempt to push the tibia forwards. Anterior translation should be readily detected by the fingers, and the firmness of the endpoint should be noted.

In the active Lachman test the relaxed knee is supported at 30° and the patient asked to extend it. If the test is positive, there will be anterior subluxation of the lateral tibial plateau as the quadriceps contracts, and posterior subluxation when the muscle relaxes. It is considered that this is best seen from the medial side. Repeat, resisting extension by applying pressure to the ankle.

10.75. Radiological analysis of anterior cruciate function (1):

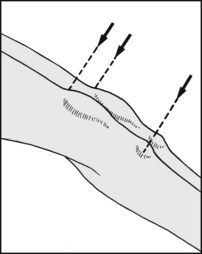

Anterior subluxation of the tibia in extension may also be demonstrated with X-rays. The lower thigh is supported by a sandbag, and the leg extended against the resistance of a 7 kg weight. The limb should be in the neutral position, with the patella pointing upwards, and the X-ray film cassette placed between the legs.

10.76. Radiological analysis (2):

On the films, draw two lines parallel to the posterior cortex of the tibia, tangential to the medial tibial plateau and the medial femoral condyle. Measure the distance between them. Normal = 3.5 mm ± 2 mm. Ruptured anterior cruciate = 10.2 mm ± 2.7 mm. The latter is slightly increased if the medial meniscus is also torn. The diagnostic reliability is high.

10.77. Posterior tibial instability: testing the posterior cruciate ligament (1): the gravity test:

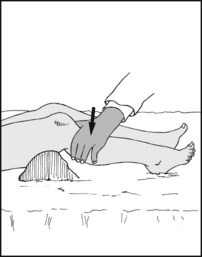

Rupture, detachment or stretching of the posterior cruciate ligament may permit the tibia to sublux backwards, frequently giving rise to a striking deformity of the knee which allows the diagnosis to be made on inspection alone. The knee should be flexed to 20°, with a sandbag under the thigh.

10.78. Posterior cruciate ligament (2):

With the leg still in 20° flexion, ask the patient to lift the heel from the couch while you observe the knee from the lateral side. Any posterior subluxation should normally correct during this extension of the knee, confirming the diagnosis.

10.79. Posterior cruciate ligament (3):

Place the thumb on one side of the joint line and the index on the other to help you assess any tibial movement. Try to pull the tibia forwards with the other hand. If the posterior cruciate ligament is torn and the tibia subluxed posteriorly, the forward movement as the tibia reduces will be easily felt.

10.80. Posterior cruciate ligament (4):

If the posterior cruciate is lax or torn, but subluxation has not yet occurred (uncommon), then backward pressure on the tibia will normally produce a detectable, excessive posterior excursion. Note that a Lachman procedure in the prone position may also be used to detect posterior cruciate laxity.

10.81. Posterior cruciate ligament (5): dynamic posterior shift test:

Flex both the knee and hip to 90°. The latter leads to hamstring tightening, which in the presence of ligament laxity leads to posterior displacement of the tibia. Now extend the knee: this displaces the axis of the pull anteriorly, and the displaced tibia will reduce. This is usually obvious to careful inspection and is indicative of posterior laxity, with or without additional posterolateral laxity.

10.82. Radiological examination of posterior cruciate ligament function (1):

A sandbag is placed behind the thigh and the proximal tibia pressed forcibly backwards (with an equivalent force of 25 kg). This is repeated, and after the second preloading cycle, radiographs are taken while the same force is maintained.

10.83. Radiological examination of posterior cruciate ligament function (2):

The gap between the medial femoral and tibial condyles is measured, along with that between the lateral condyles. A displacement of the order of 8 mm on each side is indicative of an uncomplicated posterior cruciate tear. Excessive movement on the lateral or medial sides indicates posterolateral or posteromedial instability.

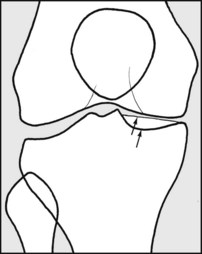

10.84. Visualisation of the cruciate ligaments:

MRI scans allow an accurate assessment of the state of the cruciate ligaments in 80% of cases. (Note that in terms of accuracy this is inferior to clinical assessment.) (Illus: intact anterior cruciate ligament.) The cruciates may also be inspected by arthroscopy. The ability of the cruciate ligaments to prevent abnormal tibial movements can be assessed mechanically by dynamic testing rigs.

10.85. Assessing tibial subluxations (rotatory or torsional instabilities):

(1) Look for medial or lateral tenderness or oedema. (2) Perform the drawer tests noting variations. (3) Test for laxity on valgus stress (often positive in anterior subluxations of the medial tibial condyle). (4) Test for laxity on varus stress (usually positive when the lateral tibial condyle subluxes forwards or backwards). (5) Carry out the following additional tests.

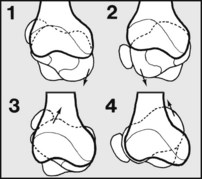

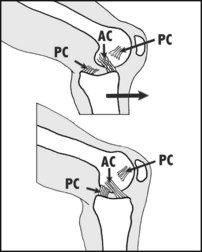

10.86. MacIntosh test for anterior subluxation of the lateral tibial condyle (the pivot shift test):

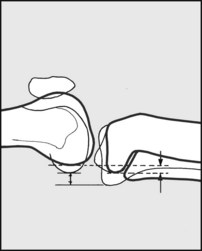

Fully extend the knee while holding the foot in internal rotation (1). Apply a valgus stress (2). In this position, if instability is present the tibia will be in the subluxed position. Now flex the knee (3): reduction should occur at about 30° with an obvious jerk. A positive test indicates an anterior cruciate abnormality, with or without other pathology.

10.87. Losee pivot shift test for anterior subluxation of the lateral tibial condyle:

The patient should be completely relaxed, with no tension in the hamstrings. Apply a valgus force to the knee (1) at the same time pushing the fibular head anteriorly (2). The knee should be partly flexed. Now extend the joint (3). As full extension is reached, a dramatic clunk will occur as the lateral tibial condyle subluxes forwards (if rotatory instability is present). Note: the patient should relate this to the sensations experienced in activity.

10.88. Modified pivot shift or jerk test for anterior subluxation of the lateral tibial condyle:

Grasp the foot between the arm and the chest, and apply a valgus stress (1); lean over to rotate the foot internally (2). Now flex the knee. If the test is positive, and because the tibia is firmly held, the lateral femoral condyle will appear to jerk anteriorly. Now extend the knee, and as the tibia subluxes the femoral condyle will appear to jerk backwards.

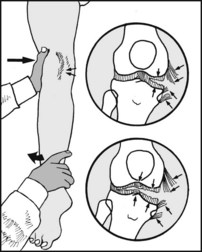

10.89. Posterolateral instability (1): the posterolateral drawer test:

The knee should be flexed to a little less than 90° and the foot placed in external rotation. Apply backward pressure on the tibia. Excessive travel on the lateral side is indicative of posterolateral instability. Posterolateral instability is usually associated with injuries to the posterior cruciate and lateral ligament complex.

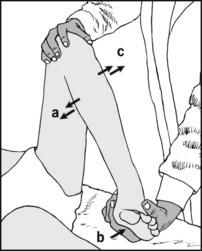

10.90. Posterolateral instability (2): the external rotation recurvatum test:

With the patient in the supine position, stand at the end of the examination couch and lift the legs by the great toes. The test is positive if the knee falls into external rotation (a), varus (b) and recurvatum (c).

10.91. Posterolateral instability (3): Jakob’s reversed pivot shift test:

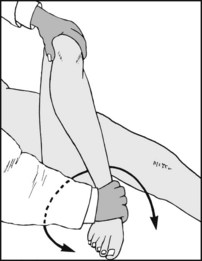

Begin by flexing the knee to 90° (a). Now externally rotate the foot (b), apply a valgus stress (c), and extend the knee (d). If the test is positive, the posteriorly subluxed lateral tibial plateau suddenly reduces at about 20°.

10.92. Posterolateral instability (4): standing apprehension test:

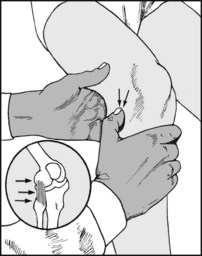

The patient should be taking his weight through the slightly flexed knee. Grasp the knee and with the thumb at the joint line press the anterior part of the lateral femoral condyle medially. The test is positive if movement of the condyle occurs (allowing the tibia to slip posteriorly under it), and if this is accompanied by a feeling of giving way.

Look for tenderness in the joint line and test for a springy block to full extension. These two signs, in association with evidence of quadriceps wasting, are the most consistent and reliable signs of a torn meniscus.

In recent injuries, look for telltale oedema in the joint line. Bruising is not a feature of meniscal injuries.

10.95. The menisci (3): posterior lesions (1):

Fully flex the knee and place the thumb and index along the joint line. The palm of the hand should rest on the patella. You are now in a position to be able to locate any clicks emanating from the joint.

10.96. The menisci (4): posterior lesions (2):

Sweep the heel round in a U-shaped arc, looking and feeling for clicks from the joint accompanied by pain. Watch the patient’s face, not the knee, while carrying out this test.

10.97. The menisci (5): anterior lesions:

Press the thumb firmly into the joint line at the medial side of the patellar ligament. Now extend the joint. Repeat on the other side of the ligament. A click, accompanied by pain, is often found in anterior meniscus lesions.

10.98. The menisci (6): McMurray manoeuvre for the medial meniscus:

Place the thumb and index along the joint line to detect any clicks. Flex the leg fully; externally rotate the foot, abduct the lower leg, and extend the joint smoothly. A click arising in the medial joint line, accompanied by complaint of pain, is indicative of a medial meniscus tear.

10.99. The menisci (7): McMurray manoeuvre for the lateral meniscus:

Repeat the last test with the foot internally rotated and the leg adducted. Use the hand to pick up the source of any clicks which are accompanied by pain. A grating sensation may be felt in degenerative lesions of the meniscus.

If any clicks are detected, the normal limb should be examined to help eliminate symptomless, nonpathological clicks which may be arising from tendons or other soft tissues snapping over bony prominences (e.g. the biceps tendon over the femoral condyle), or from the patella clicking against a femoral condyle.

If a unilateral painful click is obtained, repeat the test with the sensing finger or thumb removed. The cause of the click, whether from meniscus or tendon, may be visible on close inspection of the joint line.

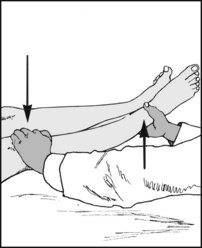

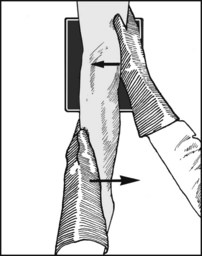

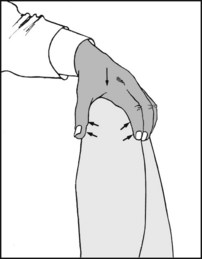

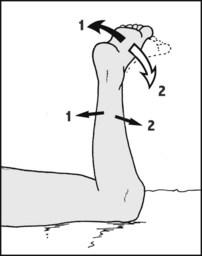

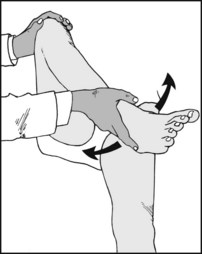

10.102. The menisci (10): Apley’s grinding tests (1):

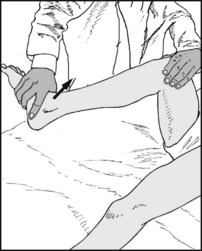

In the tests, the suspect meniscus is subjected to compression and shearing stresses; sharp pain is suggestive of a tear. The patient is prone. The examiner grasps the foot, externally rotates it and fully flexes the knee (1). He then internally rotates the foot and extends the knee (2). The sides are compared. This demonstrates any limitation of rotation, or where any pain occurs.

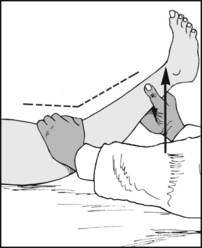

10.103. The menisci (11): grinding tests (2):

Then, while standing on a stool, the examiner throws his weight along the axis of the limb, and externally rotates the foot. Severe sharp pain is indicative of a medial meniscus tear. Repeat in a greater degree of flexion to test the posterior horn. To test the lateral meniscus, repeat the tests with the foot forcibly internally rotated.

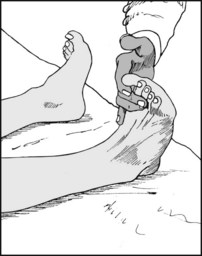

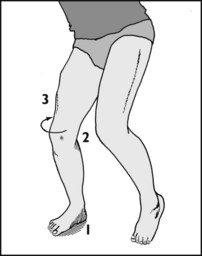

10.104. The menisci (12): Thessaly tests:

As previously described, menisci are prone to tear under simultaneously occurring circumstances: the leg must be solely weightbearing (1); it must be flexed (2); and it must be subjected to a twisting force (3). (A typical example is when a footballer’s right foot is anchored to the ground with an efficient boot, and with his right knee slightly flexed he twists round to perform a swinging kick with his left.)

The Thessaly tests duplicate this scenario, and are described as being positive when the patient experiences joint-line pain, or sensations of locking or catching within the knee like those reported. They are performed at 5° and 10° of flexion – first on the good side and then on the suspect one (to gain familiarity and confidence). The examiner holds the patient’s hands to keep his balance (4); the knee is flexed to the required amount (5) and the other lifted clear (6); and the patient twists slowly from side to side. This manoeuvre is performed 3 times. High diagnostic accuracy is claimed in the order of 95% (particularly at 10° flexion), comparable with MRI scanning which is expensive and not always available, and arthroscopy, which is both expensive and invasive.

Other dynamic testing methods include the use by physiotherapists of so-called provocative exercises and their variations. (A common method is to ask the patient to squat and attempt to catch a medicine ball which is deliberately pitched to either side so that he has to twist on his flexed, weightbearing knee to catch it.)

Meniscal cysts lie in the joint line, feel firm on palpation, and are tender on deep pressure. Cysts of the menisci may be associated with tears. Lateral meniscus cysts are by far the commonest. Cystic swellings on the medial side are sometimes due to ganglions arising from the pes anserinus (insertion of sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus).

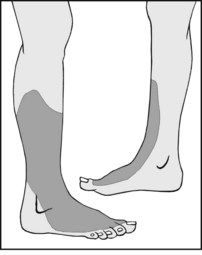

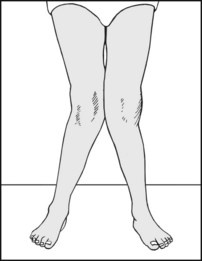

Examine both knees flexed over the end of the couch. This may show a torsional deformity of the femur or tibia, and a laterally placed patella (a) (which will be predisposed to instability (e.g. recurrent dislocation) or chondromalacia patellae). Now ask the patient to extend the knees (b), and look for any gross disturbance of patellar tracking: it should move smoothly in the patellar groove.

Look for genu recurvatum and the position of the patella relative to the femoral condyles. A high patella (patella alta) is a predisposing factor in recurrent lateral dislocation of the patella.

Is there any knock-knee deformity? Because this leads to an increase in the Q angle (quadriceps angle) it predisposes the knee to recurrent dislocation, anterior knee pain and chondromalacia patellae. The deformity is particularly common in adolescent girls. The intermalleolar distance may be measured, or the Q angle (which is similar to the tibiofemoral angle) may be determined.

10.109. The patella (4): finding the Q angle:

this is the angle (normally about 6°) between (i) a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine with the centre of the patella, and (ii) the line of the patellar ligament. Ask the patient (who must be standing) to hold the end of a tape measure on his anterior spine while you centre the other over the patella. Then align a goniometer with the tape and the patellar ligament. (Differences between the sexes are more related to height than pelvic width.)

Look for tenderness over the anterior surface of the patella, and note whether a tender, bipartite ridge is present. Lower pole tenderness occurs in Sinding–Larsen–Johannson disease. (Tenderness may also occur over the patellar ligament, quadriceps tendon and tibial tuberosity in other extensor apparatus traction injuries and variants of ‘jumper’s knee’.)

Displace the patella medially and palpate its articular surface. Tenderness is found when the articular surface is diseased, e.g. in chondromalacia patellae. Repeat the test, displacing the patella laterally. Two-thirds of the articular surface of the patella are normally accessible in this way.

Test the mobility of the patella by moving it up and down and from side to side. Reduced mobility is found in retropatellar arthritis. The quadriceps must be relaxed for adequate performance of this test. Decreased patellar mobility will obviously impair the performance of the previous test.

Move the patella proximally and distally, at the same time pressing it down hard against the femoral condyles. Pain is produced in chondromalacia patellae and retropatellar osteoarthritis.

10.114. The patella (9): the apprehension test:

Try to displace the patella laterally while flexing the knee from the fully extended position. If there is a tendency to recurrent dislocation, the patient will be apprehensive and try to stop the test, generally by pushing the examiner’s hand away.

10.115. Articular surfaces (1):

Place the palm of the hand over the patella, and the thumb and index along the joint line. Flex and extend the joint. The source of crepitus from damaged articular surfaces can then be detected. Compare one side with the other. If in doubt, auscultate the joint. Ignore single patellar clicks. (The short-form WOMAC (see p. 178) is valuable in assessing the degree and progress of osteoarthritis of the knee.)

10.116. Articular surfaces (2):

Apparent broadening of the joint and palpable exostoses occur commonly in osteoarthritis. (Both sides of the joint are affected in the later stages of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis, but in the early stages of this condition the medial side of the joint is often affected first, leading to a bow-leg deformity and frequently laxity of the medial ligament.)

Nearly all the tests previously described have involved examination of the joint from the front. Do not forget to examine the back of the joint, by both inspection and palpation. If the knee is flexed the roof of the fossa is relaxed, and deep palpation becomes possible.

Semimembranosus bursae become obvious when the knee is extended. Compare the sides. A bursa may be small at the time of examination, and transillumination is worth trying although not always positive. Note that semimembranosus bursae may be secondary to rheumatoid arthritis or other pathology in the joint.

Always examine the hip, especially in the presence of severe, undiagnosed pain, as hip pain is often referred to the knee joint. The hip may be screened by testing rotation at 90° flexion and noting pain or restriction of movements.

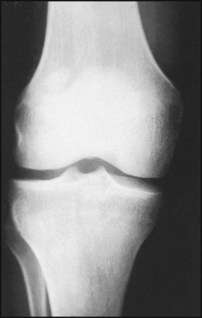

The contours of the femur, tibia and fibula are obvious. The patellar shadow is usually rather faint and difficult to make out. Note on the medial side the two tibial shadows formed by the anterior and posterior rims of the concave medial tibial plateau. (The lateral tibial plateau is convex and has a single shadow.)

Normal lateral radiograph of the knee. The arrow points to the condylopatellar sulcus, which helps identify the lateral femoral condyle, which is larger and flatter.

Note here that the lateral condyles of the femur and of the tibia are drawn with a heavy line. The lateral tibial condyle may often be identified by the fibular articulation. The outline of the medial tibial condyle tends to blend with the shadow of the tibial spines. Note the fabella, an inconstant sesamoid bone lying in the lateral head of gastrocnemius: do not mistake it for a loose body.

Note any joint space narrowing (indicating cartilage loss) (N), lipping (L), marginal sclerosis (S), cysts (C), loose bodies (H), varus or valgus (these are all common in osteoarthritis). Do not mistake a bipartite patella (B) for fracture; bipartite patella, if present, affects the outer quadrant). Note any abnormal calcification, as in Pellegrini–Steida disease (J), calcified meniscus (K), and pseudogout.

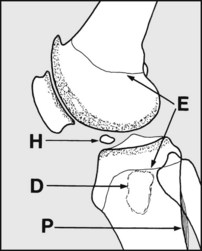

Look for alterations in bone texture (e.g. in Paget’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, osteomalacia, infections). Note any bone defects (D) suggestive of tumour or infection, or areas of periosteal reaction (P), perhaps indicative of tumour or infection. Do not mistake epiphyseal lines (E) for hairline or other fractures.

Intercondylar (tunnel) radiographs are often of help in confirming the diagnosis of osteochondritis dissecans, as they show the common sites more clearly, especially in the medial femoral condyle. They are also of value in locating loose bodies.

Where the patella is suspect, a tangential (skyline) view should he obtained. This may show (1) a marginal (medial) osteochondral fracture, common in recurrent dislocation of the patella, (2) other fractures, (3) occasionally, evidence of chondromalacia patellae, (4) bipartite patella.