CHAPTER 5 The elbow

Anatomical Features

General Points

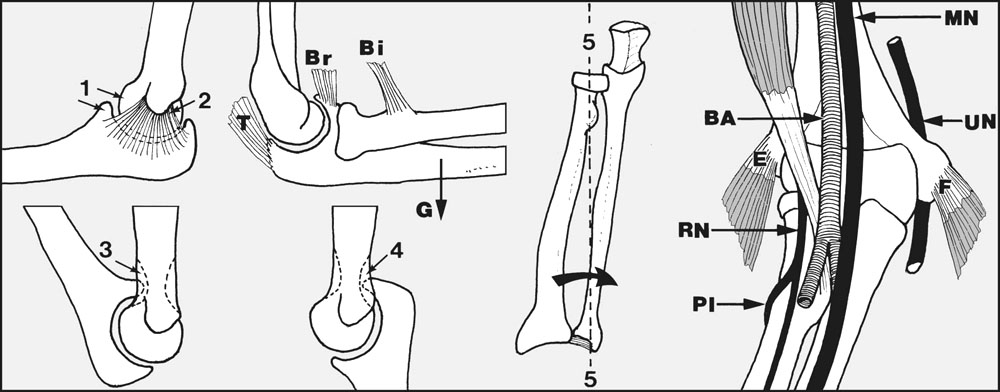

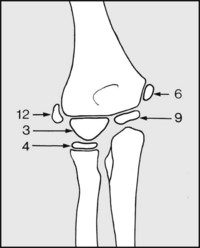

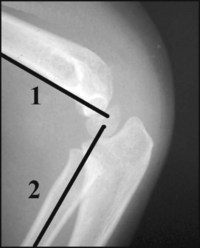

The calliper-like close fit between the ulna and the trochlea (1) contributes to the impressive stability of the normal elbow; this is aided by the strong collateral ligaments (2). Instability may be seen following certain fractures of the coracoid or olecranon, owing to impairment of the stabilising bony features of the joint. It may follow ligamentous laxity from repeated stretching and tears in athletes; or it may occur when the ligaments become lax in the course of rheumatoid arthritis or an elbow joint infection.

At the end of flexion the coronoid process tucks into the coronoid fossa (3), and at full extension, the olecranon process fits into the olecranon fossa (4). The clearances are small, and only a little local disturbance, such as a small loose body in one of the fossae, may produce a significant restriction of movement.

The elbow joint is normally extended by gravity (G); forced extension is powered by triceps (T); and triceps acting with the elbow flexors (biceps (Bi) and brachialis (Br)) holds the elbow straight and rigid.

The axis (5) of pronation and supination passes through the radial head and the attachment of the triangular fibrocartilage.

Mechanically, pronation and supination may be restricted by problems involving the elbow, wrist or forearm bones. Pronation is controlled by pronator teres and pronator quadratus; supination is carried out by biceps and supinator.

Tennis Elbow

This is by far the commonest cause of elbow pain in patients attending orthopaedic clinics. It is generally believed to be due to a strain of the common extensor origin, but fibrosis in extensor carpi radialis brevis or a nerve entrapment syndrome have been suggested as alternative causes. The patient, usually in the 35–50-year age group, complains of pain on the lateral side of the elbow and difficulty in holding any heavy object at arm’s length. There may be a history of recent excessive activity involving the elbow, e.g. dusting, sweeping, painting, or even playing tennis.

In sportsmen, a period of rest or modification of a flawed game-playing technique may allow the condition to settle. In manual workers relief may follow avoidance of the suspected causal activity, although this may not always be possible. When these basic measures fail, an elbow clamp (employed to redirect the pull of the forearm extensors) can be effective. Symptoms are also usually relieved by one to three injections of local anaesthetic and hydrocortisone into the painful area, and local ultrasound may be tried. Excellent results have been claimed from extracorporeal shock-wave therapy. In resistant cases, when all conservative measures have failed, exploration of extensor carpi radialis brevis may be considered (with excision of any fibrous mass or lengthening of the tendon).

In golfer’s elbow there is a similar history, but here pain and tenderness involve the common flexor origin on the medial side of the elbow. This condition is much less common than tennis elbow.

Cubitus Varus and Cubitus Valgus/Elbow Instability

A decrease or increase in the carrying angle of the elbow generally follows a supracondylar or other elbow fracture in childhood. Although the normal child has great powers of spontaneous recovery following injury, there may nevertheless be some epiphyseal damage that fails to correct; where there is evidence of interference with the carrying angle the child should be observed for a number of years. If there is failure of spontaneous correction, or even deterioration, and the deformity is very unsightly, correction by osteotomy may be undertaken. In later life either of these deformities may be followed by a tardy ulnar nerve palsy.

Medial instability may occur in athletes who subject their elbows to severe valgus stresses by throwing, e.g. javelin throwers and baseball pitchers. There may be attenuation of the medial collateral ligaments, or even rupture. Mild cases may subside with rest, but in some a reconstruction may become necessary if there is the desire to continue with the activity. Instability is also seen in rheumatoid arthritis, the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and in Charcot’s disease.

Tardy Ulnar Nerve Palsy

This ulnar nerve palsy is slow in onset and progression. It appears usually between the ages of 30 and 50, and the preceding injury to the elbow, considered responsible for the ischaemic and fibrotic changes in the nerve, has usually been in childhood. It is seen most frequently where there is a cubitus valgus deformity. The progress of the palsy may be arrested by transposition of the nerve from its normal position behind the medial epicondyle to the front of the joint.

Ulnar Neuritis and the Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome

Ulnar neuritis, with its frequent accompaniment of small muscle wasting and sensory impairment in the hand, may occur as a complication of local trauma at the elbow or at the wrist. At the elbow, it is also seen where the nerve is abnormally mobile. In these circumstances it is exposed to frictional damage as it slips repeatedly in front of and behind the medial epicondyle. In such cases reanchorage or transposition may prevent further deterioration. Some advocate epicondylectomy.

The nerve is also subject to pressure as it passes between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris below the elbow (the cubital tunnel), or as it lies in the ulnar tunnel in the hand. Where the local findings are not clear enough to localise the site of involvement, nerve conduction rate studies are often most helpful.

In a number of cases no obvious cause for an ulnar neuritis may be found.

Olecranon Bursitis

Swelling of the olecranon bursa is common in carpet-layers and others who repeatedly traumatise the posterior aspect of the elbow joint. Swelling of the bursa is also common in rheumatoid arthritis, and there may be associated nodular masses in the proximal part of the forearm. The condition is usually painless unless there is an associated bacterial infection within the bursa. Excision is sometimes advised for cosmetic reasons.

Pulled Elbow

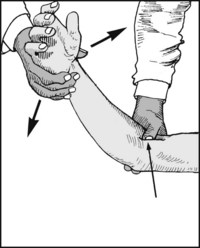

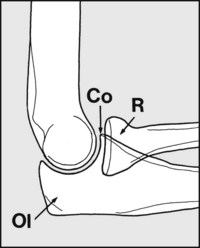

This condition occurs in young children under the age of 5, and is produced by traction on the arm, as for example when a mother snatches the hand of a child wandering towards the edge of a pavement. The radial head slides out from under cover of the orbicular ligament, and the child complains of pain and limitation of supination. The orbicular ligament and radial head may be reduced by forced supination while pushing the radius in a proximal direction (by forced radial deviation of the hand). On the other hand, spontaneous reduction, without manipulation, usually occurs within 48 hours of the incident if the arm is rested in a sling.

Osteoarthritis and Osteochondritis Dissecans

Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow joint is not uncommon in heavy manual workers. Osteoarthritis is also seen secondary to old fractures involving the articular surfaces of the elbow. It may also follow osteochondritis dissecans. Both osteoarthritis and osteochondritis dissecans may give rise to the formation of loose bodies, which restrict movements or cause locking of the joint. The joint may lock in any position, and the patient often develops the trick of unlocking the joint himself. If loose bodies are found, they should be removed to prevent further incidents of locking and to reduce the risk of their causing more damage to the articular surfaces. Joint replacement surgery in those suffering from osteoarthritis of the elbow is seldom indicated, as the physical demands are likely to exceed the capabilities of any current replacement.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis may affect either one or both elbows. If both elbows are involved the functional disability may be particularly great.

Clinically there may be marked synovitis, painful restriction of movements, and a fixed flexion deformity. Pronation and supination may be restricted and painful, although in some cases the distal radioulnar joint may be responsible. When there is gross destruction of the elbow, the ulnar nerve may be affected and the joint may become flail.

Medical treatment and steroid injections may help in the early stages. Later, synovectomy with excision of the radial head may delay progress; and in advanced cases, with gross instability, joint replacement may be considered.

Tuberculosis of the Elbow

Tuberculosis of the elbow is now very uncommon; marked swelling of the elbow with profound local muscle wasting is usually so striking that there is unlikely to be a delay in further investigation by aspiration and synovial biopsy.

Myositis Ossificans

This condition occurs most commonly after supracondylar fractures and dislocations of the elbow. Calcification occurs in the haematoma that forms in the brachialis muscle covering the anterior aspect of the elbow joint. It is particularly common in association with head injuries, and may also follow over-vigorous physiotherapy. It leads to a mechanical block to flexion. If discovered at an early stage, complete rest of the joint is necessary to minimise the mass of material formed. In later cases it may be excised after the lesion has appeared quiescent for many months, and postoperatively a single dose of radiation therapy may help prevent recurrence.

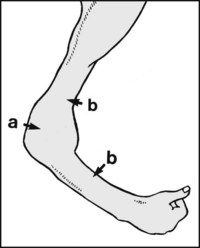

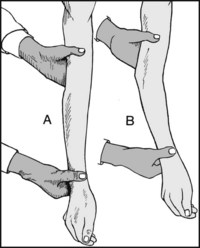

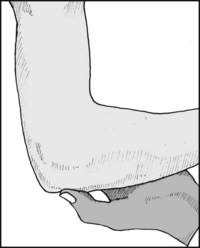

Look for (a) generalised swelling of the joint and (b), muscle wasting, both suggestive of infective arthritis (e.g. tuberculosis) or rheumatoid arthritis. The swollen elbow is always held in the semiflexed position, as in this position intra-articular pressure, and hence pain, is least marked.

Note that the earliest clinical sign of effusion is the filling out of the hollows seen in the flexed elbow above the olecranon (A). The next sign is swelling of the radiohumeral joint (B). Fluid may be squeezed between these two areas.

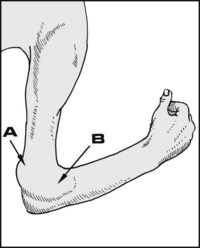

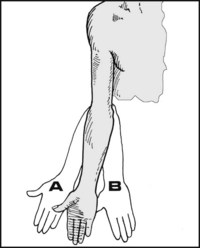

Note whether there are any localised swellings round the joint, e.g. (A) olecranon bursitis, (B) rheumatoid nodules.

Ask the patient to extend both elbows and note the carrying angle on both sides. Any small difference between the sides will then be obvious.

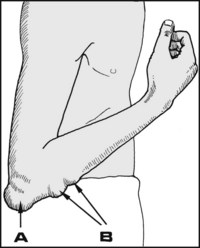

(A) In cubitus valgus there is an increase in the carrying angle. (B) In cubitus varus there is a decrease in the carrying angle (‘gunstock deformity’). The commonest cause of unilateral alteration in the carrying angle is an old supracondylar fracture. Valgus and/or varus laxity and instability (confirm by stressing) may also follow certain elbow fractures.

Extension: (A) Full extension, 0°, is present if the arm and forearm can be made to lie in a straight line. (B) Loss of full extension is especially common in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and old fractures (particularly of the radial head) involving the elbow joint.

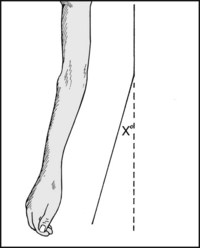

Hyperextension: If the elbow can he extended beyond the neutral position, record this as ‘X° hyperextension’. Up to 15° is accepted as normal, especially in women. Beyond this, look for hypermobility in other joints (for example as may occur in the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome).

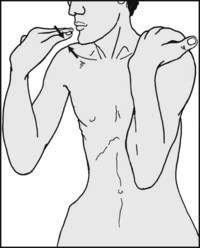

Flexion (1): (Screening test) Ask the patient to attempt to touch both shoulders. A slight difference in flexion between the sides is then usually obvious.

Flexion (2): The range of flexion may be measured.

Restriction of flexion is common after all fractures round the elbow, and in all forms of arthritis.

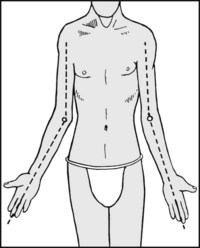

Pronation/supination screening (1): Ask the patient to hold the elbows closely to the sides. Turn the palms upwards into supination and compare the sides.

Pronation/supination screening (2): Now turn the palms downwards in pronation, again comparing the sides.

Supination: Supination may be recorded. Give the patient a pencil to hold, and note the angle from the vertical that can be achieved.

Pronation: This may he measured in the same way.

Pronation/supination movements may be reduced after fractures at the elbow, in the forearm and at the wrist (e.g. most commonly after Colles’ fracture). Loss may also occur after dislocation of the elbow, and rheumatoid and osteoarthritis. Pure supination loss may occur in children with pulled elbow.

Begin by locating the epicondyles and the olecranon. If in doubt, flex the elbow and note the equilateral triangle normally formed by these structures. This relationship is disturbed in elbow subluxations.

Palpate the lateral epicondyle with the thumb. Sharply localised tenderness here or just distal is almost diagnostic of tennis elbow. Carry our confirmatory tests (22 et seq.). Note that after the injection of hydrocortisone locally (e.g. for tennis elbow) tenderness becomes more diffuse.

Palpate the medial epicondyle. Tenderness occurs here in golfer’s elbow, tears of the ulnar collateral ligament, and injuries of the medial epicondyle.

Tenderness over the olecranon is uncommon, apart from after fracture and infected olecranon bursitis, both of which are usually obvious.

Press the thumb firmly into the space on the lateral side of the elbow between the radial head and humerus. Now pronate and supinate the arm. Tenderness here is common after injuries of the radial head, osteoarthritis and osteochondritis dissecans.

Palpate the front of the elbow on both sides of the biceps tendon while flexing and extending the elbow through 20°. Note the presence of any abnormal masses (e.g. myositis ossificans, loose bodies).

Roll the ulnar nerve under the fingers behind the medial epicondyle. Note whether there is any difference between the sides. If indicated, carry out a fuller examination of the nerve.

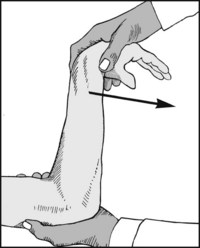

Tennis elbow (1): Flex the elbow and fully pronate the hand. Now extend the elbow. Pain over the lateral epicondyle is almost diagnostic of tennis elbow.

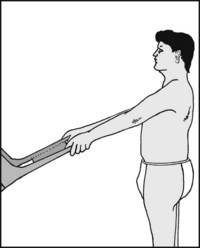

The chair test. Ask the patient to attempt to lift a chair (of about 3.5 kg in weight) with the elbows extended and the shoulders flexed to 60°. Difficulty in performing this manoeuvre, with complaint of pain on the lateral aspect of the affected elbow, is suggestive of tennis elbow.

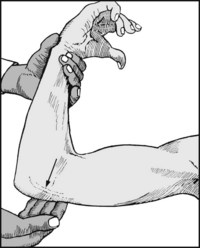

Thomsen’s test: Ask the patient to clench the fist, dorsiflex the wrist and extend the elbow. Try to force the hand into palmar flexion while the patient resists. Severe pain over the external epicondyle is again most suggestive of tennis elbow.

(5): Repeat, this time attempting to flex the extended middle finger rather than the wrist.

5.26. Additional tests: golfer’s elbow:

Flex the elbow, supinate the hand, and then extend the elbow. Pain over the medial epicondyle is very suggestive of golfer’s elbow.

5.27. Additional tests: ulnar nerve (1):

Inspect the medial side of the elbow carefully while the patient flexes and extends the joint. The nerve is visible in the thin patient, and displacement on movement may be obvious.

Palpate again and note the extent of any tenderness, and whether the nerve is thickened. Look again for cubitus valgus. Look for evidence of ulnar nerve palsy.

5.29. Additional tests: elbow instability:

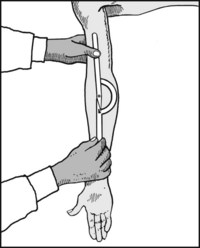

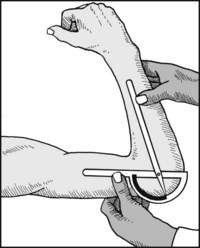

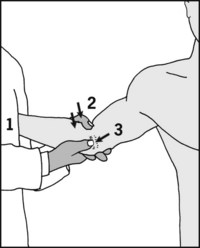

Both valgus and varus instability may be tested by stressing the joint in extension and 30° flexion (as performed for the collateral ligaments in the knee). Alternatively, for valgus instability (which is the commonest), anchor the patient’s arm in 30° elbow flexion against your side (1), apply a valgus stress (2), and feel for any gap opening up on the medial side (3).

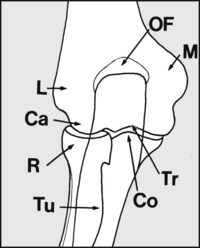

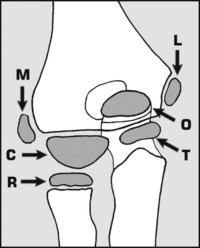

In examining the standard AP view trace out the outline of (M), the medial epicondyle; (OF) the olecranon and coronoid fossae; (L) the lateral epicondyle; (Ca) the capitulum; (R) the radial head; (Tu) the tuberosity of the radius; (Co) the coronoid process of ulna; (Tr) the trochlea.

In examining the standard lateral projection, note (R) the radial head; (Co) the coronoid process of the ulna; (Ol) the olecranon.

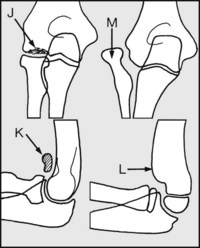

Look for (J) any defects in the capitulum suggesting osteochondritis dissecans; (K) loose bodies (usually secondary to osteoarthritis or osteochondritis); (L) incompletely remodelled supracondylar fracture (usually associated with loss of flexion); (M) old Monteggia fracture (fracture of ulna and dislocation head of radius), usually associated with reduction of pronation and supination.

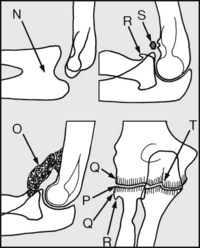

Note the presence of (N) a congenital synostosis (with inevitable loss of pronation and supination); (O) myositis ossificans (with clinically restriction of flexion). Note any osteoarthritic changes with, for example, (P) joint space narrowing, (Q) bony sclerosis of the joint margins, (R) osteophytes, (S) loose body formation, or (T) evidence of previous fracture.

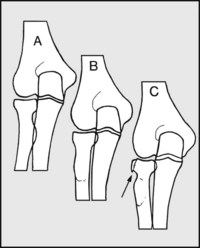

Where the radial head is suspect, radiographs should he taken in the anteroposterior plane (A) in midposition, (B) in supination, (C) in pronation. These may bring an area of osteochondritis of the radial head or an old fracture into profile.

Normal anteroposterior radiograph of the elbow of a child of 8. There are six epiphyses round the elbow, and these appear and unite at various times. There are considerable individual, gender and racial variations in these timings. Nevertheless, in certain situations (e.g. in suspected fractures and dislocations), a knowledge of these is essential.

All six epiphyses are shown simultaneously in this diagram. Memorising the time of their appearance may be aided with the popular mnemonic CRITOL, where C = capitulum (capitellum) at 1 year, R = radial head at 3 years, I = internal (medial) epicondyle at 5 years, T = trochlea at 7 years, O = olecranon at 9 years and L = lateral epicondyle at 11 years. These epiphyses generally unite 2 years after they first appear.

In most situations the old mnemonic ‘cite’ (capitulum, internal epicondyle, trochlea, external epicondyle) for the appearance of the epiphyseal centres at 3, 6, 9 and 12 years, is normally sufficiently accurate.

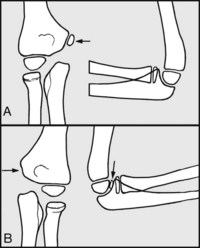

If there is any doubt, radiographs of both sides should be taken. Note that if a child over the age of 6 has injured the elbow there is every likelihood that the medial epicondyle has become displaced into the joint if it cannot be seen in the anteroposterior view, or if it can be seen in the lateral. (A) Normal, (B) displaced.

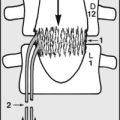

In examining the lateral X-ray projection of a child’s elbow, especially after suspected trauma, always check the alignment of the humeral epiphyseal complex with the humeral shaft. Because of its anterior tilt of 45°, a line (1) drawn down the anterior surface of the humerus should strike the complex. Similarly, a line (2) drawn along the shaft of the radius should strike the complex if the radial shaft is in alignment (i.e. if there is no elbow dislocation).

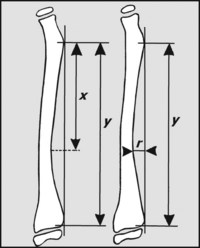

Apart from pathology at the elbow (and wrist) pronation and supination may be affected by disturbance of radial bowing (e.g. after a forearm fracture). Bowing may be assessed using the method of Schemitsch and Richards which uses an AP radiograph taken in the mid position. The location of maximum bowing (x/y × 100) is normally situated 60% along the shaft, while the degree of bowing (r/y × 100) is between 7% and 10%.

The proximal radioulnar joint is not present, and no pronation/supination movements are possible. The epiphysis of the olecranon has not yet united.

After an elbow injury a large mass of bone has formed in the front of the joint, and has virtually obliterated all movements.

There is gross disturbance of the architecture of the elbow joint, and bony ankylosis has occurred.

Diagnosis: in this case the cause was a gunshot wound to the elbow, with extensive bone damage.

There is an obvious defect in the olecranon, with separation of the fragments. The complaints was of weakness of elbow movements.

Diagnosis: ununited fracture of the olecranon. Injuries of this type may have surprisingly few symptoms, but there is often weakness (as was the case here) and restriction of extension.

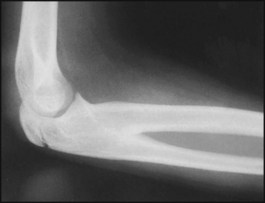

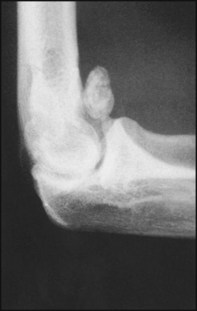

The radiograph is of an acute case where, following a dislocation of the elbow, there was marked restriction of movements.

Diagnosis: the medial epicondyle has displaced and become trapped in the joint.

Both projections show narrowing of the joint space between the ulna and the humerus, with a degree of marginal bone sclerosis. In the lateral view there is lipping of the olecranon, and multiple loose bodies are present.

Diagnosis: osteoarthritis of the elbow with loose body formation. Synovial chondromatosis may have a similar appearance.

The radial head has lost its normal site of articulation with the capitulum, and there is a cubitus valgus deformity. The appearances are of a long-standing lesion.

Diagnosis: this is an old Monteggia fracture dislocation of the elbow. The ulnar fracture has healed and is no longer visible, but the dislocation of the radial head persists. In this case there was an associated tardy ulnar nerve palsy.

The articular surfaces between the humerus and ulna have been virtually obliterated following a long period of pain, swelling and loss of function in the elbow.

Diagnosis: in this case this was due to tuberculous infection of the joint, and ankylosis has resulted.

There is a gap between the distal articular complex of the humerus and the distal humeral shaft. There was little movement left in the elbow joint itself, but there was a limited range of rather unstable movements proximal to it.

Diagnosis: this is an example of longstanding non-union following a supracondylar fracture of the humerus.

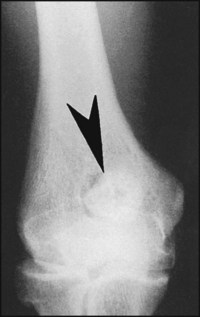

The arrow points to an abnormality in the region of the coronoid fossa. This was associated with severe restriction of elbow flexion.

Diagnosis: this is a large loose body. In the single view the source is not obvious, but the most likely causes are osteochondritis dissecans or osteoarthritis. The loss of flexion is due to a purely mechanical block to movement.

This lateral radiograph shows a large loose bony mass lying in the front of the elbow joint.

Diagnosis: loose body, probably secondary to osteochondritis dissecans or osteoarthritis. In some cases loose bodies of this type may be extruded and come to lie in the brachialis muscle, where their mechanical effects on elbow flexion are less obtrusive.

5.55. Elbow radiographs: examples of pathology (13):

This radiograph shows an irregularity of the capitulum involving its articular surface. This was associated with aching pain in the joint of several months’ duration.

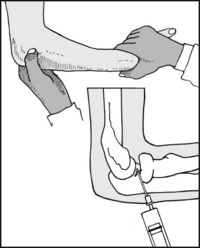

5.56. Aspiration of the elbow joint:

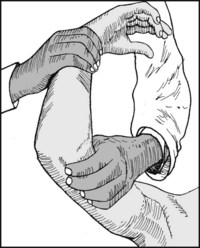

The most direct and safest approach is from the lateral side. Flex the elbow to 90°; to locate the radial head, pronate and supinate the arm, and feel with the thumb for its rotation. After infiltration of the area with local anaesthetic, introduce the aspirating needle in the area of the palpable depression between the proximal part of the radial head and the capitulum.