CHAPTER 2 Segmental and peripheral nerves of the limbs

The Brachial Plexus: Cervical Part

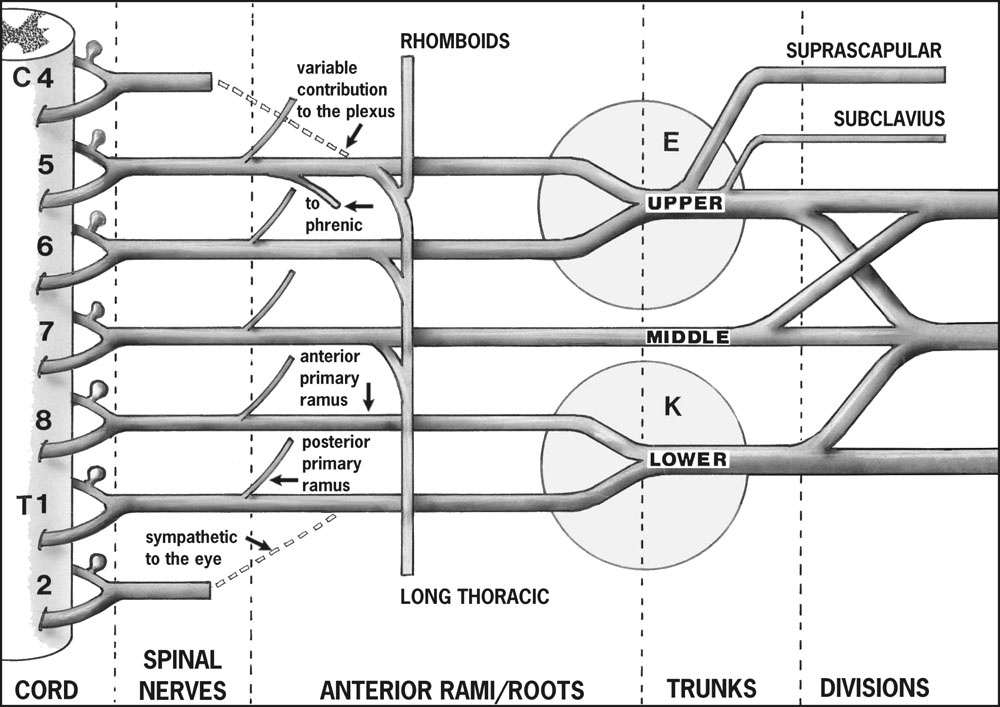

The roots of the brachial plexus are formed by the anterior primary rami of C5–T1 inclusive, with occasional contributions from C4 and T2. The roots lie between the scalene muscles in the neck. (Do not confuse the roots of the plexus with the roots of the segmental spinal nerves, which are intrathecal.) C5 and C6 form the upper trunk, C7 forms the middle trunk, and C8 and T1 form the lower trunk. (Preganglionic sympathetic nerve fibres to the upper limb arise from T2–T6, ascend in the sympathetic trunk, synapse in cervicothoracic ganglia, and pass to the upper limb mainly through the lower trunk of the plexus. An important localising point to note is that preganglionic fibres en route to the eye via the stellate ganglion arise from T1.) The trunks are found in the posterior triangle of the neck. The subclavian artery lies in front of the lower trunk.

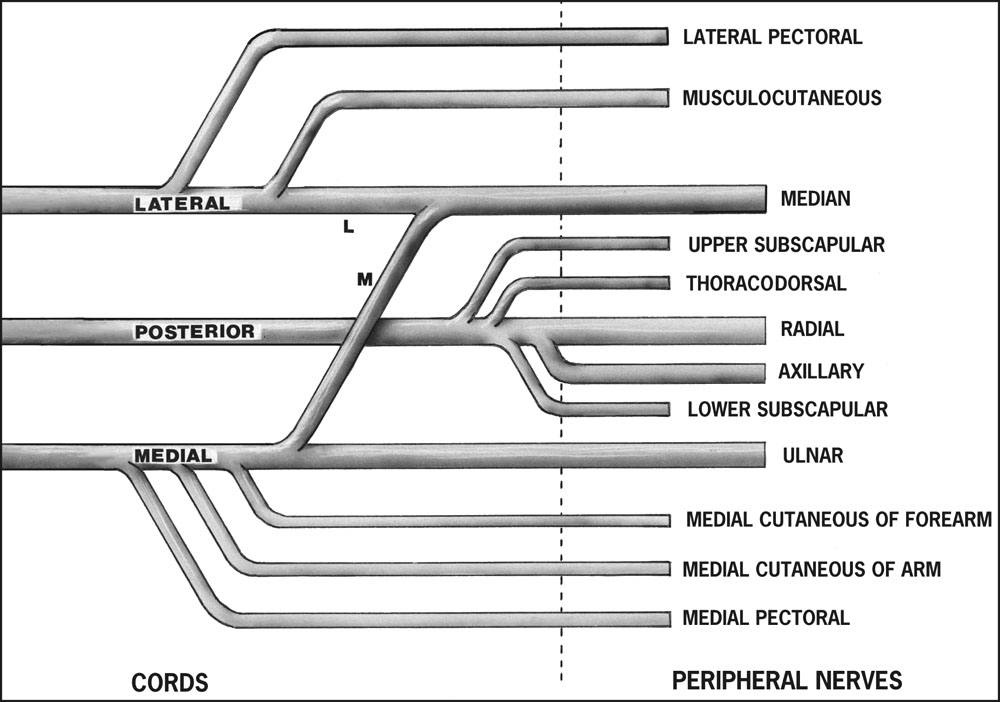

Each trunk forms an anterior and a posterior division. The divisions lie behind the clavicle. The three posterior divisions form the posterior cord, the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks form the lateral cord, and the anterior division of the lower trunk continues as the medial cord. The divisions and commencement of the cords lie in the posterior triangle of the neck.

The brachial plexus has a most extensive distribution, and the order in which the nerves come off is of value in determining the site of any lesion. This is of particular importance in traumatic lesions, where the prognosis and treatment are closely related to the level of injury.

Branches from the Nerve Roots

The first branches of the plexus to be given off arise from the nerve roots themselves. Two important branches in this category are:

C5 also contributes to the phrenic nerve, and C5, 6, 7 and 8 supply the scalenes and longus colli. Although not strictly branches of the brachial plexus, these segmental branches are of some importance; paralysis of the hemidiaphragm, when found after a brachial plexus injury, indicates a proximal lesion.

Branches from the Trunks

There are two branches only at this level:

Both these nerves arise from the upper trunk. All the branches from the nerve roots and trunks arise above the clavicle (the supraclavicular branches).

1. In Erb’s (upper obstetrical) palsy (E in Fig. 2.1) the C5–6 roots are affected but the nerve to rhomboids and the long thoracic nerve are spared.

2. In Klumpke’s (lower obstetrical) palsy (K in Fig. 2.1) the C8–T1 roots are involved. The sympathetic nerve supply to the eye (arising from T1) is often also affected, leading to a Horner’s syndrome. It was said that 80% of birth injuries to the plexus make a full recovery by 13 months, and persisting severe sensory or motor deficits in the hand are rare; recent work suggests that this view is somewhat optimistic. Note that a number of obstetrical injuries to the plexus are accompanied by facial nerve palsy and posterior dislocation of the shoulder.

3. In traumatic plexus lesions in adults the commonest patterns of injury are (a) C5–6 (Erb type); (b) C5, 6, 7; (c) C5–T1 inclusive.

The Brachial Plexus: Axillary Part

The cords for the most part lie in the axilla, and are closely related to the axillary artery. (The axillary artery commences at the outer border of the first rib and ends at the lower border of teres major. The second part of the axillary artery lies behind the pectoralis minor, with the first and third parts of the artery lying above and below it. The three cords enter the axilla above the first part, embrace the second part in the position indicated by their names, and give off their branches around the third part.)

Branches from the Cords

The medial cord (C8, T1)

The posterior cord (C5, 6, 7, 8, T1)

Details of the most important branches (median, ulnar, radial, axillary) are given later.

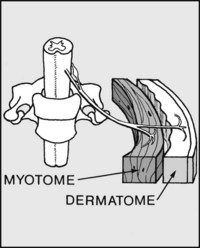

Where you suspect involvement of spinal nerves rather than peripheral nerves (e.g. injuries to the spine or brachial plexus, cervical spondylosis etc.) you must examine myotomes and dermatomes. These are the muscle masses and areas of skin supplied by single spinal nerves (no matter how the nerve fibres within these spinal nerves are finally distributed via the limb plexuses and peripheral nerves).

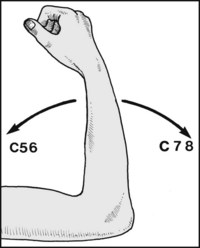

Normally two roots produce movement of a joint in one direction, and two in another. This is true at the elbow, where weakness of elbow flexion and an absent biceps tendon jerk indicate C5,6 involvement; and where weakness of extension and an absent triceps jerk suggest a C7,8 lesion. This general rule is followed throughout the lower limb, but is modified in the highly specialised upper limb.

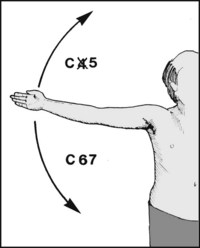

In a distal or proximal joint the four spinal segments involved differ by plus or minus one, so that theoretically the shoulder should be controlled by C4,5,6,7. However, C4 has been suppressed, with the result that abduction is mediated through C5 alone (deltoid, supraspinatus etc). Adduction (involving principally pectoralis major) is controlled by C6,7.

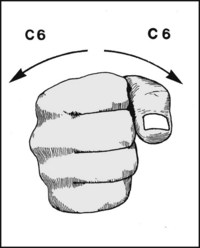

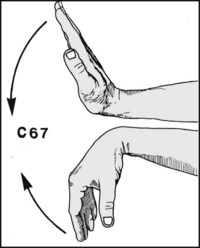

At the wrist, where C6,7 would have been expected to control palmar flexion only, it is the case that these two segments control dorsiflexion as well.

A single segment again, namely T1, is involved in producing abduction and adduction of the fingers: these movements are carried out by the small muscles (intrinsics) of the hand. Note: In testing for myotomes the ability to perform the above movements should be assessed by MRC grading, and note made of the segments affected. Often the defect can be localised to a single segment.

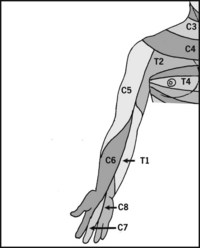

Note that the middle finger is supplied by C7, and that there is a regular, easily remembered sequence of sensory distribution round the preaxial line of the limb.

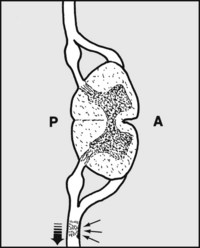

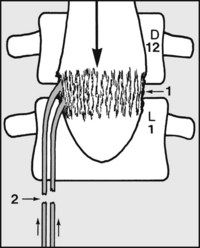

2.10. Types of brachial plexus injury (1):

Lesions in continuity: more than half of plexus injuries are of this pattern. Traction is the commonest cause, and the nerve roots are affected between the intervertebral foramina and the clavipectoral fascia (postganglionic). The lesions may be transient (neuropraxia). If the axons degenerate (axonotmesis), regeneration occurs at the rate of 1 mm/day, provided the axons can penetrate the intraneural scar.

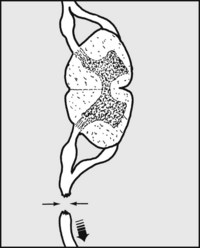

2.11. Lesions with ruptured nerve roots (2):

In more severe injuries the nerves are disrupted at the same level. Only surgical intervention can offer any hope of recovery, but repair, even with nerve grafting, may be impossible because of extensive intraneural damage. It is important to differentiate between lesions of this type, lesions in continuity (where the treatment is expectant), and cord avulsion lesions (where the prognosis is hopeless).

2.12. Complete avulsion lesions (3):

The nerve is avulsed from the cord and surgical repair is impossible. Motor axons degenerate and the paralysed muscles show denervation fibrillation potentials on the electromyograph (EMG). The cells of the sensory nerves in the dorsal root ganglion remain intact (preganglionic lesion); although sensation is lost, conduction within the distal nerve remains and may be detected through externally applied electrodes.

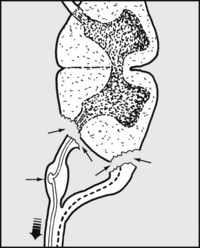

2.13. Partial avulsion lesions (4):

Rarely, the posterior roots are spared, so that there may be the paradox of muscle paralysis accompanied by preservation of sensation. The prognosis for the motor loss is in these circumstances also hopeless. Although the exact nature of the lesion may seem fairly clear after clinical examination and further investigation, in many cases the picture is complex owing to the fact that one or more of these injuries may be combined.

2.14. Long-standing plexus lesions (1):

In Erb’s palsy (upper obstetrical palsy), which affects the upper trunk of the brachial plexus (and hence C5,6), there is deformity of the limb, which is held in a characteristic position: the wrist is flexed and pronated, and the fingers flexed. The elbow is extended and the shoulder internally rotated (waiter’s tip deformity). The nerve to rhomboids and the long thoracic nerve are usually spared.

2.15. Long-standing plexus lesions (2):

In Klumpke’s paralysis the small (intrinsic) muscles, including the hypothenar and thenar groups, are wasted and there is a claw hand deformity. There is sensory loss on the medial side of the forearm and wrist. In many cases there is an associated Horner syndrome. (Note also that 38% of patients who receive radiotherapy for breast carcinoma develop a brachial neuropathy.)

2.16. Long-standing plexus lessons (3):

The T1 root alone may be involved, the sole signs being wasting of the small muscles of the hand, including the thenar group, along with sensory loss on the medial side of the hand only. Lesions of this type are seen in incomplete lower obstetrical palsy, cervical spondylosis, cervical rib syndrome, neurofibromatosis, and apical and metastatic carcinoma.

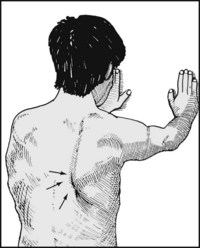

2.17. Acute traumatic lesions of the brachial plexus:

The commonest mechanisms of injury involve depression of the shoulder combined with lateral flexion of the neck to the opposite side, or traction on the arm. Motorcycle accidents are the single most common cause. On inspection, look for the presence of telltale bruising over the shoulder or at the root of the neck. In the more severe cases the arm hangs flaily at the side.

Begin by determining the extent of the lesion, i.e. which segments are involved, and whether the involvement is partial or complete. Start by testing for active movements in the shoulder, elbow, wrist and fingers, relating your findings to the myotomes responsible for these movements. Then check for sensation to pinprick and light touch, again noting the dermatomes involved (which normally correspond with the previously determined myotomes).

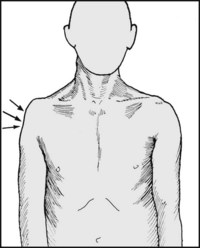

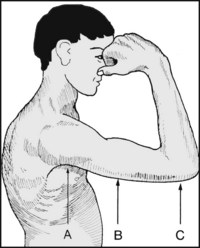

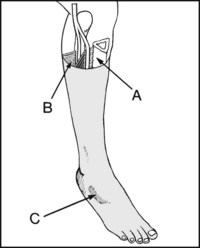

After determining which segments are affected, you should try to form an opinion as to the type of injury. This may be difficult to clarify, but the more evidence there is of proximal damage, the greater the chance of cord avulsion and a poor prognosis. Horner’s syndrome, characterised by (A) pseudoptosis, (B) smallness of the pupil on the affected side, and (C) dryness of the hand from absence of sweating, occurs when the T1 root is involved close to the canal.

Look for sensory loss above the clavicle. This area is normally supplied by C3,4, and if this is affected it generally indicates that the injury has been so severe that it has not only involved the plexus but the roots above; it is usually indicative of a proximal injury with a poor prognosis. Deep bruising in the posterior triangle is also strongly suggestive of a preganglionic lesion.

Now test the first nerves that come off the plexus. Nerve to rhomboids (C5): Ask the patient to place the hand on the hip and to resist the elbow being pushed forwards; feel for contraction in the rhomboid muscles. Absence of activity is indicative of a lesion proximal to the formation of the upper trunk of the plexus (and suggestive of cord avulsion). Presence of activity means a lesion distal to the intervertebral foramen.

Nerve to serratus anterior (C5,6,7): Damage to this nerve produces winging of the scapula, which is normally demonstrated by asking the patient to lean with both hands against a wall, but this test may have to be abandoned in the presence of an extensive plexus lesion. (Note that the nerve to serratus anterior may be damaged in isolation through lifting very heavy weights.)

Suprascapular nerve (C5,6): This nerve arises from the upper trunk of the plexus and supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. To test for activity in the supraspinatus, ask the patient to try to abduct the arm against resistance; feel for muscle contraction above the spine of the scapula. (The infraspinatus may be tested by feeling for muscle contraction below the spine of the scapula while the patient attempts to rotate the shoulder externally.)

Other tests, observation and investigations. (1) Tinel’s sign: Tap vigorously at the side of the neck, working from above downwards in the line of the nerve roots as they emerge from the spine. The test is positive if there is marked, painful paraesthesia in the corresponding dermatomes: for example, if tapping over the C6 root produces severe pain and tingling in the thumb. A positive test generally indicates a ruptured nerve root and a postganglionic lesion. (It is said, however, that the test may also be positive in the presence of an avulsed posterior root ganglion.)

(2) X-ray and MRI scans: (a) Plain films of the cervical spine should be obtained. Although these are of principal value in eliminating other pathology, they may occasionally reveal a transverse process fracture; such a fracture is indicative of the severity of an injury and the probability of an irrecoverable lesion. (b) A plain posterior–anterior (PA) radiograph of the chest may reveal paralysis of a hemidiaphragm, indicative of a proximally sited lesion. (c) An MRI scan may clarify the site of nerve disruption, particularly in the case of preganglionic lesions. (d) Myelography may give valuable information regarding the presence or absence of signs of avulsion of roots from the cord. Signs indicative of a poor prognosis include traumatic meningocoele, loss or diminution or exaggeration of root pouches, and cystic accumulation of CSF within the spinal canal.

(3) Electromyography: It has been recommended that at least two muscles supplied by each root should be examined by the insertion of needle electrodes: the presence of any action potentials will indicated some continuity in that root.

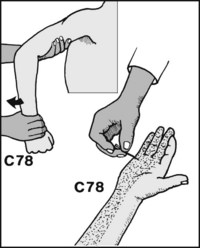

(4) Sensory conduction: Sensory conduction may be assessed in two ways: (a) by electrically stimulating (say) the median nerve at the wrist, and by means of separate electrodes attempting to pick up resultant potentials over the plexus or in the neck (evoked potentials); or (b) stimulating (say) the median nerve at the wrist, and attempting to pick up potentials distally by means of ring electrodes round the index finger (sensory action (antidromic) potentials). The latter method appears preferable. One side is compared with the other. If the sides are the same, this suggests a severe or complete preganglionic lesion (avulsion of nerve roots from the cord). If no sensory action potentials are obtained on the injured side, this suggests a postganglionic lesion; and if diminished action potentials are present, a mixed lesion is likely.

(5) Histamine test: A drop of 1% histamine is placed over the centre of each affected dermatome and the skin pricked through it; the normal side is used as a control. On the normal side there should be the usual triple response, with the flare fully developed within 10 minutes. Absence of a flare on the injured side suggest postganglionic damage. If a normal triple response is found persisting after 3 weeks in anaesthetic skin, a preganglionic lesion is virtually certain.

2.25. Signs indicating a poor prognosis in traumatic plexus lesions:

Classification of brachial plexus injuries in children: The Narakas classification is simple and useful for grading the severity of any lesion. It may help in deciding whether to embark on surgical repair.

In surgically untreated cases it has been found that there is full spontaneous recovery in 90% of cases in Group I. In Group II, normal function was regained in only 25% of cases. No child in Group III made a full recovery, although in the majority of cases hand function was good. In Group IV, 50% were found to have no or poor hand function.

2.26. Examination of the peripheral nerves of the upper limb:

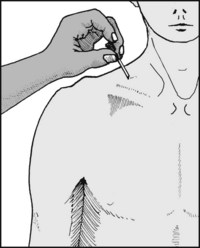

The axillary (circumflex) nerve (posterior cord) C5,6: (1): This nerve is most commonly damaged during shoulder dislocations and displaced fractures of the proximal humerus (humeral neck fractures). Spontaneous recovery usually occurs. Flattening over the lateral aspect of the shoulder develops when muscle wasting is at its height.

Ask the patient to attempt to move the arm from the side, pain permitting, while you resist any movement. Look and feel for deltoid contraction. Sometimes this is difficult to assess, and the two sides should be carefully compared if there is any doubt.

Look for loss of sensation over the ‘regimental badge’ area of the shoulder: this is the area exclusively supplied by the axillary nerve. Where the shoulder is too painful to move (e.g. if dislocated) loss of sensation is sufficient evidence of axillary nerve involvement without testing muscle power.

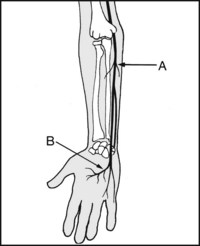

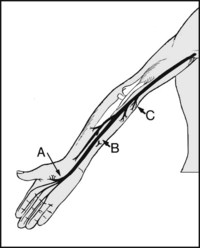

2.29. Radial nerve: (posterior cord) C5,6,7,8 (T1):

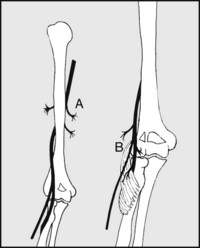

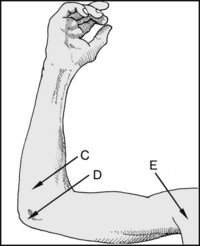

Motor distribution: (A) In the upper arm the radial nerve supplies triceps. (B) In front of the elbow, it supplies brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and brachialis. Its posterior interosseous branch, before it enters the supinator tunnel, supplies extensor carpi radialis brevis and part of supinator.

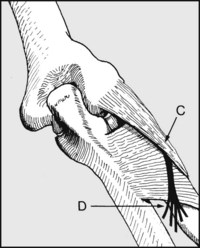

2.30. Radial nerve (motor distribution) contd.:

(C) In the supinator tunnel the posterior interosseous branch of the radial supplies the rest of supinator; lesions here may cause local tenderness. (D) On leaving supinator below the elbow it supplies extensor digitorum communis, extensors digiti minimi and indicis, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus and extensors pollicis longus and brevis.

Sensory distribution: (A) The terminal part (the superficial radial nerve) supplies the radial side of the back of the hand. (B) The posterior cutaneous branch of the radial, given off in the upper part of the arm, supplies a variable area on the back of the arm and forearm.

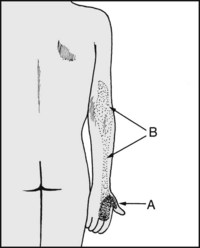

Common sites affected: (A) In the axilla (e.g. from crutches, or the back of a chair in the so-called ‘Saturday night’ palsy); (B) mid-humerus (from fractures and tourniquet palsies); (C) at and below the elbow (e.g. after dislocations of the elbow, Monteggia fractures, ganglions, and sometimes surgical trauma following exposures in this region).

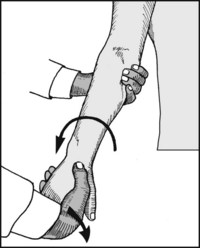

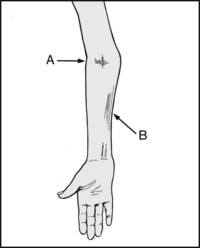

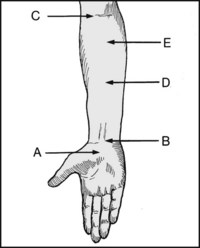

2.33. Examination of the radial nerve (1):

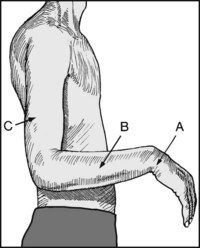

Note in particular the following: (A) Is there an obvious wrist drop? (B) Is there wasting of the forearm muscles? (C) Is there wasting of the triceps, suggesting a high (proximal) lesion?

2.34. Examination of the radial nerve (2):

Test the extensors of the wrist and fingers. The elbow should be flexed and the hand placed in pronation. Support the wrist, and ask the patient first to try and straighten the fingers and then to pull back the wrist: if there is any activity, judge the strength by applying counterpressure on the fingers or hand.

2.35. Examination of the radial nerve (3):

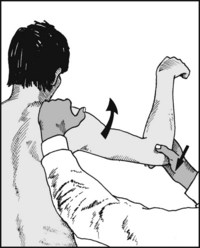

Now test the supinator muscle. The elbow must be extended to eliminate the supinating action of biceps. Ask the patient to turn his hand while you apply counterforce. Loss of supination suggests a lesion proximal to the exit of the supinator tunnel. Look for tenderness over the tunnel.

2.36. Examination of the radial nerve (4):

Test the brachioradialis. Ask the patient to flex the elbow in the mid-prone position against resistance. Feel and look for contraction in the muscle. Loss of power suggests a lesion above (proximal to) the supinator tunnel.

2.37. Examination of the radial nerve (5):

Now test the triceps. Extend the shoulder and ask the patient to extend the elbow, first against gravity and then against resistance. Weakness of triceps suggests a lesion at mid-humeral level, or an incomplete high lesion; loss of all triceps activity suggests a high (plexus) lesion.

2.38. Examination of the radial nerve (6):

Test for sensory loss in the areas supplied by the nerve. Loss confined to the hand indicates that the lesion is unlikely to be much proximal to the elbow. Careful analysis of both the motor and sensory deficits should allow accurate localisation of the lesion.

2.39. Ulnar nerve (medial cord) C8, T1:

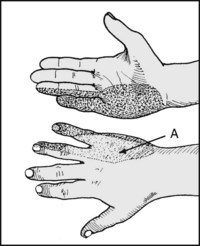

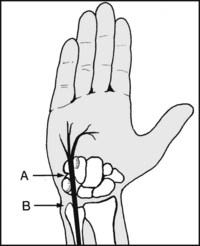

Motor distribution: (A) In the forearm it supplies flexor carpi ulnaris and half of flexor digitorum profundus. (B) In the hand, it supplies the hypothenar muscles, the interossei, the two medial lumbricals, and adductor pollicis.

Sensory distribution: Note that there are variations in the areas supplied by the median and ulnar nerves in the hand: the commonest pattern is illustrated. The branch supplying the dorsum (A) arises in the forearm; loss here indicates a lesion proximal to the wrist.

2.41. Ulnar nerve: common sites affected (1):

(A) In the ulnar tunnel syndrome, where the nerve passes between the pisiform and the hook of the hamate (e.g. from the pressure of a ganglion, or a hook of hamate fracture). The most distal lesions affect the deep palmar nerve and are entirely motor. (B) At the wrist, especially from lacerations, occupational trauma and ganglions.

2.42. Ulnar nerve: common sites affected (2):

(C) Distal to the elbow, by compression as it passes between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar tunnel syndrome). (D) At the level of the medial epicondyle (e.g. in ulnar neuritis secondary to local friction, pressure or stretching, as may occur in cubitus valgus and osteoarthritis). (E) In the brachial plexus, as a result of trauma, or from other lesions in this area.

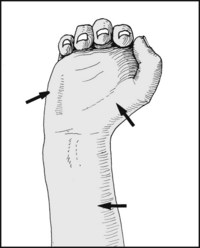

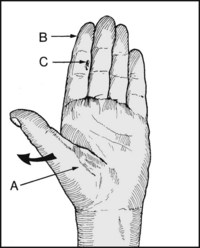

2.43. Ulnar nerve examination (1):

Note the presence of (A) involuntary abduction of the little finger; (B) hypothenar wasting; (C) ulceration of the skin, brittleness of the nails, and any other evidence of trophic change.

2.44. Ulnar nerve examination (2):

Note whether there is an ulnar claw hand, with flexion of the ring and little fingers at the proximal interphalangeal (IP) joints. If the distal IP joints are flexed as well, this suggests that the flexor digitorum profundus is intact and the lesion is distally placed: i.e. paradoxically, the deformity of the hand is less marked in lesions proximal to the wrist, where there is more motor involvement.

2.45. Ulnar nerve examination (3):

The ulnar nerve supplies all the interossei, so look for the presence of any interosseous muscle wasting. The first dorsal interosseous muscle is almost always the first to become noticeably affected, and the hollowing of the skin on the dorsal aspect of the first web space is often most striking.

2.46. Ulnar nerve examination (4):

Note (A) if there is any cubitus valgus or varus deformity suggesting an old injury, such as a supracondylar fracture (of significance in tardy ulnar nerve palsy). (B) Muscle wasting on the medial side of the forearm, confirming a lesion proximal to the wrist. Compare one forearm with the other.

2.47. Ulnar nerve examination (5):

Flex and extend the elbow, looking for abnormal mobility in the nerve where it passes behind the medial epicondyle. If the nerve is seen to snap over the medial epicondyle, a traumatic ulnar neuritis (secondary to a deficiency in the tissues that normally anchor it in position) may be diagnosed with reasonable confidence.

2.48. Ulnar nerve examination (6):

Roll the nerve under the fingers above the medial epicondyle and follow it distally until it disappears under cover of flexor carpi ulnaris – about 4 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. Note the presence of any tenderness, thickening, or the production of an unusual degree of paraesthesia.

2.49. Ulnar nerve examination (7):

Palpate the nerve as it lies just lateral to the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris at the wrist. Follow it down to the region of the ulnar tunnel, again looking for undue tenderness and paraesthesia.

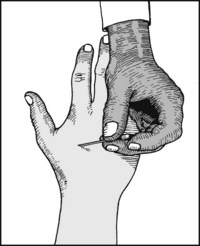

2.50. Ulnar nerve examination (8):

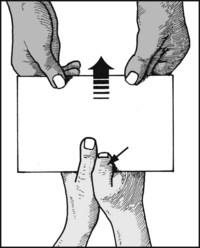

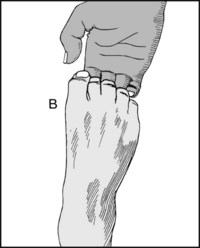

Testing the interossei. Ask the patient to hold a sheet of paper between the ring and little fingers. The fingers must be fully extended. Withdraw the paper and note the resistance offered. In a complete palsy the little finger is normally held in slight abduction and the patient will be unable to grip the paper at all.

2.51. Ulnar nerve examination (9):

Testing the first dorsal interosseous muscle. Place the patient’s hand in a palm-downwards position and ask him to resist while you attempt to adduct the index. Look and feel for contraction in the first dorsal interosseous.

2.52. Ulnar nerve examination (10):

Testing abductor digiti minimi. Ask the patient to resist as you adduct the extended little finger with your index. Note the resistance offered and compare one hand with the other.

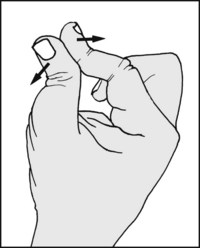

2.53. Ulnar nerve examination (11):

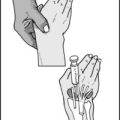

Testing adductor pollicis (1). Ask the patient to grasp a sheet of paper between the thumbs and sides of the index fingers while you attempt to withdraw it. If the adductor of the thumb is paralysed the thumb will flex at the interphalangeal joint, in contrast to the good side (Froment’s test).

2.54. Ulnar nerve examination (12):

Testing adductor pollicis (2). Alternatively, test the patient’s ability to grasp a sheet of paper held between the thumb and the anterior aspect of the index metacarpal.

2.55. Ulnar nerve examination (13):

Testing flexor carpi ulnaris (1). Ask the patient to resist while you attempt to extend the flexed wrist. Feel for the tendon tightening at the wrist while you note the resistance offered.

2.56. Ulnar nerve examination (14):

Testing flexor carpi ulnaris (2). Place the hand on a flat surface and ask the patient to resist while you attempt to adduct the little finger. Again feel for contraction in the tendon. Loss of activity indicates a lesion proximal to the wrist.

2.57. Ulnar nerve examination (15):

Testing flexor digitorum profundus. Only the ulnar half of this muscle is supplied by the ulnar nerve. Support the middle phalanx of the little finger and ask the patient to try to flex the distal joint. Apply counterpressure to the fingertip and note the resistance. Loss of power indicates a lesion near or above the elbow.

2.58. Ulnar nerve examination (16):

Testing for sensation. Test for any disturbance of pinprick sensation in the area supplied by the nerve. Note that sensory loss on the dorsum is indicative of a lesion proximal to the wrist.

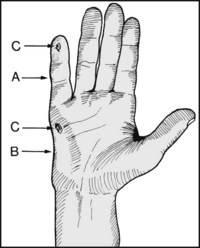

2.59. Median nerve (lateral and medial cords) C(5)6,7,8, T1:

Motor distribution. (A) Hand: the thenar muscles and the lateral two lumbricals. (B) Forearm (through its anterior interosseous branch): flexor pollicis longus, half of flexor digitorum profundus, pronator quadratus. (C) Near the elbow: flexor digitorum superficialis (sublimis), flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus and pronator teres.

2.60. Median nerve: sensory distribution:

Note that there is considerable variation in the relative areas supplied by the median and ulnar nerves. Note also that the lateral side of the posterior aspect of the hand is supplied by the terminal part of the radial nerve (superficial radial nerve) (R). The commonest pattern of sensory distribution is shown.

2.61. Median nerve: common sites affected:

(A) In the carpal tunnel (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome, and some fractures and dislocations about the wrist). (B) At the wrist (e.g. from lacerations). (C) At the elbow (e.g. after elbow dislocations in children). (D) In the forearm (anterior interosseous nerve) from forearm bone fractures, or by a tight tissue band at the origin of the superficialis. (E) Just distal to the elbow, in the pronator teres nerve entrapment syndrome.

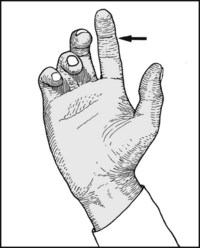

2.62. Median nerve examination (1):

Note (A) thenar wasting. In long-standing cases the thumb may come to lie in the plane of the palm (Simian thumb). (B) Atrophy of the pulp of the index, cracking of the nails and other trophic changes. (C) Cigarette burns and other signs of skin trauma secondary to local sensory deprivation.

2.63. Median nerve examination (2):

In lesions of the anterior interosseous branch, or of the median nerve itself at or above the elbow, there may be wasting of the lateral aspect of the forearm, and the index is held in a position of extension (‘benediction attitude’; but note that in some quarters an ulnar nerve palsy with an ulnar claw hand has confusingly attracted the same term).

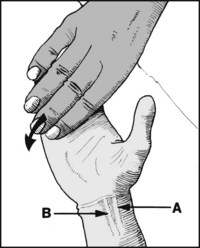

2.64. Median nerve examination (3):

Testing pronator teres. Extend the patient’s elbow and feel for contraction in the muscle as he attempts to pronate the arm against resistance. Loss indicates a lesion at or above the elbow. Accompanying pain and tenderness over pronator teres is found in the pronator teres entrapment syndrome.

2.65. Median nerve examination (4):

Anterior interosseous branch (1): Test the power of flexor pollicis longus in the thumb, and flexor digitorum profundus in the index by asking the patient to try to flex the appropriate distal joint while you support the phalanx proximal to it. Loss of power here may also occur in median nerve lesions proximal to the anterior interosseous branch.

2.66. Median nerve examination (5):

Anterior interosseous branch (2): Screening test: Ask the patient to form a circle with his index and thumb and press their tips tightly together. In an anterior interosseous palsy the terminal phalanges of the thumb and index will hyperextend (owing to paralysis of flexor pollicis longus and the lateral half of flexor digitorum profundus), but the thenar muscles will remain intact.

2.67. Median nerve examination (6):

Anterior interosseous nerve palsy (3): Screening test in children: When a child with an anterior nerve palsy is asked to bend the end joint of the index finger he will use his other hand to do so. This shows that he understands the request, that movement of the finger is not painful (as it might be in a compartment syndrome), and that it is unlikely that he is able to undertake the movement actively. Palsy may be idiopathic, due to entrapment, or follow a supracondylar fracture.

2.68. Median nerve examination (7):

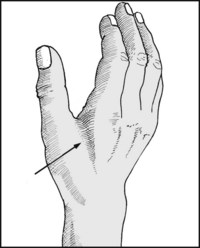

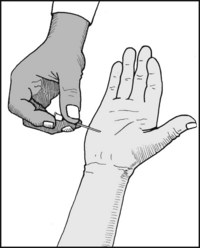

Distal segment: First locate the position of the nerve at the wrist. Ask the patient to flex his wrist, then attempt to extend it while he resists. Look for the tendons which are prominent at the front, near the midline, palpating the area if necessary. The nerve lies between (A) flexor carpi radialis longus and (B) palmaris longus (or medial to flexor carpi radialis longus if the latter is absent).

2.69. Median nerve examination (8):

Apply firm pressure over the area of the nerve at the wrist and distally in the line of the carpal tunnel, looking for tenderness. (If the carpal tunnel syndrome is suspected, apply pressure with both thumbs, timing the onset of paraesthesia; and carry out the other tests detailed later in Chapter 6.)

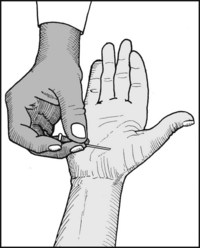

2.70. Median nerve examination (9):

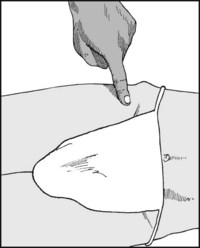

Testing abductor pollicis brevis (1): This muscle is invariably and exclusively supplied by the median nerve. To test it, begin by placing the patient’s hand, palm upwards, on a flat surface. Hold your index finger above the palm.

2.71. Median nerve examination (10):

Testing abductor pollicis brevis (2): Now ask the patient to raise his thumb and try to touch your finger. If he tends to move his hand while doing so, steady it with your other hand. Assess his ability to carry out the movement (he may not be able to do it), and look for contraction in the muscle.

2.72. Median nerve examination (11):

Testing abductor pollicis brevis (3): Ask the patient to resist while you attempt to force the thumb back down to the starting position. Note the resistance offered; palpate the muscle to confirm its tone and bulk, and compare the power on the affected side with that of the other.

2.73. Median nerve examination (12):

Testing for sensation: Look for impairment of sensation to pinprick in the area of distribution of the nerve.

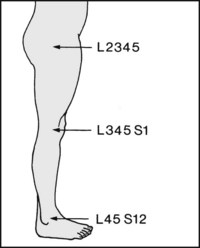

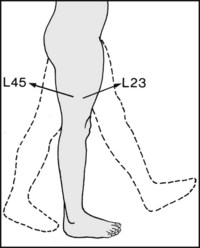

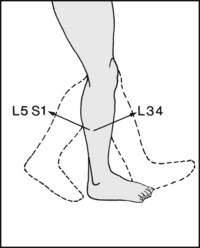

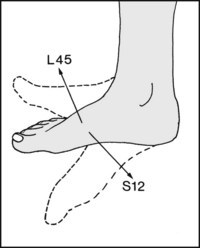

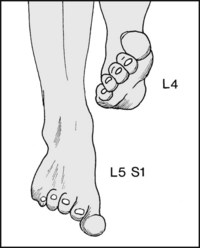

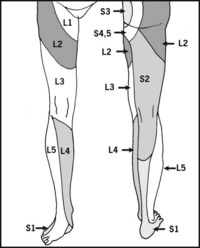

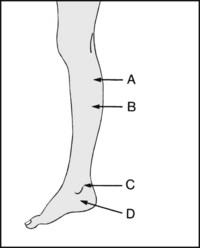

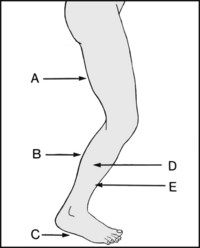

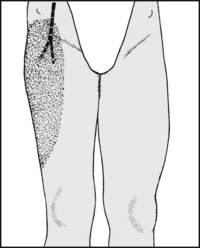

2.74. Segmental nerves in the lower limb:

Myotomes (1): As previously described in relation to the upper limb, the general arrangement is that four consecutive spinal segments control each lower limb joint. In the case of the lower limb adherence to this plan is more rigorous. The progression of control from hip to ankle is shown in the diagram.

Flexion of the hip (mainly iliopsoas) is controlled by L2,3. Extension of the hip (mainly gluteus maximus and the hamstrings) is controlled by L4,5 (L2,3 also control internal rotation, and L4,5 external rotation of the hip).

Extension of the knee and the knee jerk (quadriceps) is controlled by L3,4. Flexion of the knee (mainly hamstrings) is controlled by L5, S1.

Dorsiflexion of the ankle is controlled by L4,5 (mainly tibialis anterior and the long extensors of the hallux and toes). Plantar flexion is controlled by S1,2 (mainly the muscles of the calf). The same segments control the ankle jerk.

It is also useful to know that inversion (mainly tibialis anterior) is controlled by L4. Eversion is controlled by L5, S1 (the peronei).

Remember by the following: the side of the foot, S1, is commonly involved in L5–S1 disc lesions. L5 sweeps from the medial side of the foot next to S1 to the lateral side of the leg. L4 occupies the medial side, L2,3 occupy the thigh. It may be helpful to remember ‘we stand on S1, kneel on L3, and sit on S3’.

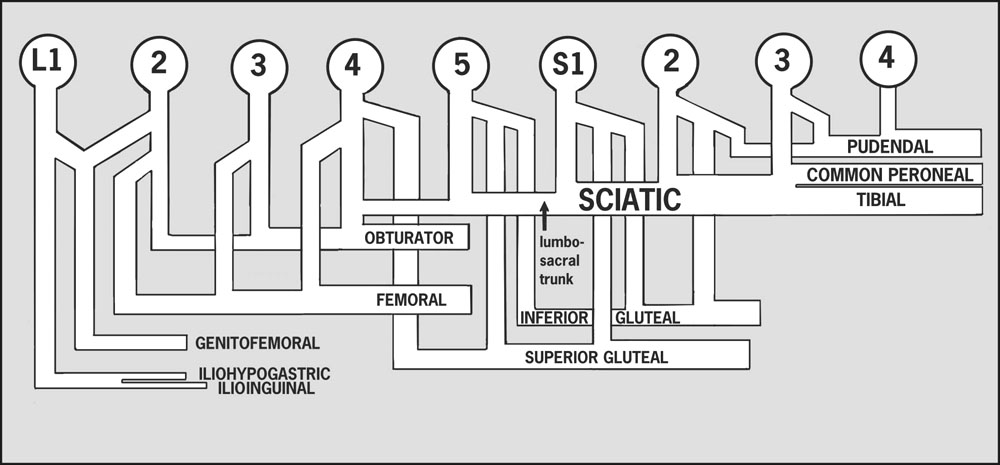

2.80. Peripheral nerves of the lower limb:

The most important nerves of the lower limb are:

Other branches shown include the pudendal (S2,3,4), the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal (L1), and the genitofemoral (L1,2). Not illustrated are the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L2,3), the nerves to quadratus femoris and the inferior gemellus (L4,5 S1), the nerves to obturator internus and the superior gemellus (L5 S1,2), the nerve to piriformis (S(1),2), the nerves to levator ani and the external sphincter (S4).

The lumbosacral trunk is formed from L4 and L5. In its progress it crosses the triangle of Marcille (bounded medially by L5, inferiorly by the proximal part of the sacrum, and laterally by the medial border of psoas), where it may be vulnerable to local pressure or traction. (Some consider that a number of cases of drop foot and other neurological problems occurring in late pregnancy may be due to involvement of the lumbosacral trunk rather than disc prolapse.)

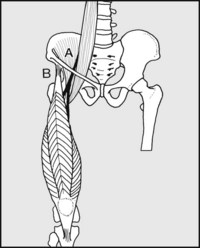

2.81. Femoral nerve: L2, 3, 4: (1):

Motor distribution: (A) Above (i.e. proximal to) the inguinal ligament the femoral nerve supplies iliopsoas. (B) Below the inguinal ligament it supplies the quadriceps, sartorius and pectineus.

Sensory distribution: On emerging below the inguinal ligament it supplies the front of the thigh. The terminal part of the femoral nerve (renamed the saphenous nerve) supplies the medial side of the leg and the foot.

Sites of involvement: Closed lesions of the femoral nerve are rare. Damage may occur when a haematoma is formed in the iliacus muscle, causing local pressure. This is seen in haemophilia and in extension injuries of the hip.

Tests: (A) Test the quadriceps by asking the patient to extend the knee against resistance. (B) Test the iliopsoas (hip flexion against resistance). The response to these tests should determine the level of any lesion. In doubtful cases try to elicit the knee jerk. Observe any quadriceps wasting, and test for loss of sensation to pinprick in the area supplied by the nerve.

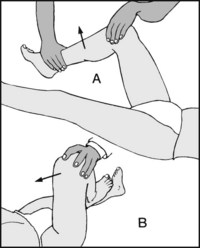

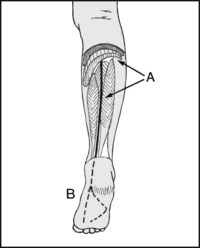

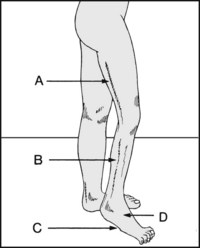

2.85. Common peroneal nerve (lateral popliteal): L4,5, S1,2 (1):

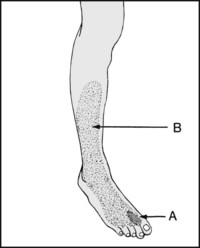

Motor distribution: (A) Muscles of the anterior compartment (tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, peroneus tertius). (B) Muscles of peroneal compartment (peroneus brevis and longus). (C) On the foot, extensor digitorum brevis.

2.86. Common peroneal nerve (2):

Sensory distribution: (A) The first web space (deep peroneal contribution). (B) The dorsum of the foot and the front and side of the leg (superficial peroneal contribution).

2.87. Common peroneal nerve (3):

Sites of involvement: (A) At the fibular neck, e.g. from trauma (e.g. lateral ligament injuries of the knee, direct blows), and from pressure, e.g. from plaster casts (or the side irons of a Thomas splint), ganglion, ischaemia (e.g. tourniquet). It is also involved in a number of neurological disorders. (B) Distal to the fibular neck, e.g. in the anterior compartment syndrome, where the deep peroneal branch may be affected.

2.88. Common peroneal nerve (4):

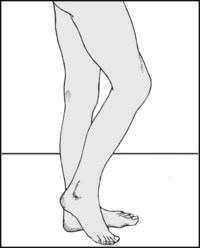

Deformity: The patient will have a drop foot and there will be disturbance of the gait: either the leg will be lifted high to allow the plantarflexed foot to clear the ground, or the foot will be slid along the ground (resulting in rapid and obvious unilateral wear of the shoe).

2.89. Common peroneal nerve (5):

Tests: (A) Ask the patient to dorsiflex the foot (deep peroneal branch) and (B) to evert the foot (superficial peroneal branch). Test for sensation in the area of distribution of the nerve. Note any wasting of the front or side of the leg.

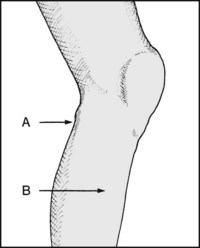

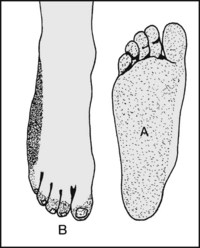

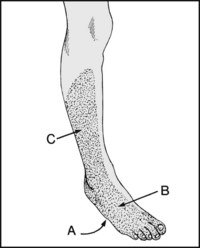

2.90. Tibial nerve (medial popliteal) (1): L4,5, S1,2,3:

Motor distribution: (A) Soleus and the deep muscles of the posterior compartment (tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus). (B) All the muscles of the sole of the foot through its terminal branches of the medial and lateral plantar nerves. It also supplies gastrocnemius before passing under the soleal arch.

Sensory distribution: (A) The sole of foot through the medial and lateral plantar nerves, whose territory includes (B) the nailbeds and distal phalanges on the dorsal surfaces of the toes. Note that the side of the foot is supplied by the sural nerve, which is derived from the tibial nerve and the common peroneal nerve.

Common sites of involvement: (A) When passing under the soleal arch, e.g. from proximal tibial fractures. (B) From ischaemic lesions of the calf (e.g. from tight plasters and the posterior compartment syndromes), and from diabetic neuropathy. (C) When passing behind the medial malleolus (e.g. from lacerations and fractures). (D) When in the foot (e.g. in the tarsal tunnel syndrome).

Diagnosis: Note any muscle wasting in the sole of the foot, clawing of the toes and trophic ulceration. (B) Test the power of toe flexion. (C) Look for sensory loss in the area supplied by the nerve.

Proximal lesions of the nerve (i.e. as it lies in the popliteal fossa) are uncommon owing to the protection afforded by the surrounding soft tissues, and the space available to accommodate expanding lesions. The findings are essentially the same as in distal lesions, but with wasting and loss of power of plantarflexion owing to paralysis of gastrocnemius as well as the soleus.

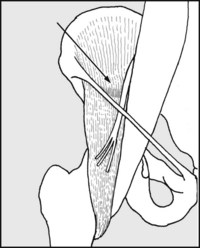

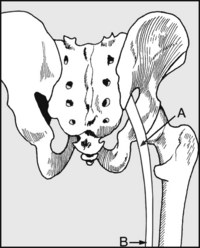

2.95. Sciatic nerve (1): L4,5, S1,2,3:

The losses include those seen in both tibial and common peroneal nerve palsies. Motor loss: (A) The hamstrings in the thigh. (B) The superficial and deep muscles of the calf (tibial nerve). (C) The muscles of the sole of the foot (medial and lateral plantar nerves). (D) The peronei (superficial peroneal). (E) The anterior compartment muscles (deep peroneal).

Sensory loss: (A) The entire sole of the foot. (B) The dorsum of the foot. (C) The lateral aspect of the leg and lateral half of the calf. Note that the medial side of the calf and foot are spared. If the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh is involved, there is loss of sensation at the back of the thigh.

Sites involved: (A) Behind the hip, e.g. after posterior dislocation of the hip, rarely after some pelvic fractures, and after hip surgery. (B) Following deep wounds in the back of the thigh, which are also uncommon. Do not confuse a sciatic palsy with root involvement in intervertebral disc prolapse.

Diagnosis: Note extensive wasting in (A) the thigh, (B) the calf, and of the peronei, and (C), the sole of the foot. Note (D), a drop foot. Observe any trophic ulceration. Note loss of power in the hamstrings and in all three compartments below the knee, an absent ankle jerk, and extensive sensory loss.

2.99. Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh (1) (L2,3):

The nerve pierces or passes under the lateral portion of the inguinal ligament and supplies the lateral aspect of the thigh. It may be compressed by the inguinal ligament, giving rise to pain and paraesthesiae in the leg (meralgia paraesthetica). Note, however, that symptoms with the same distribution may occur secondary to spinal stenosis.

2.100. Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh (2):

Test: Pressure over the nerve may give rise to paraesthesia in the thigh. Test for sensory impairment in the area supplied by the nerve.

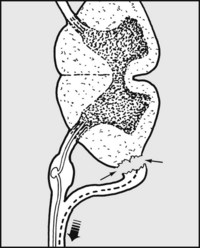

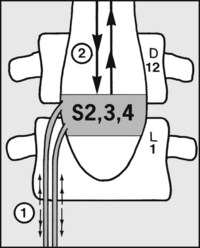

2.101. Neurological control of the bladder:

Note: (a) Autonomic fibres controlling the detrusor muscle of the bladder and the internal sphincter travel from cord segments S2, 3 and 4 to the bladder via the cauda equina (1). (b) Under normal circumstances bladder sensation and voluntary emptying are mediated through pathways stretching between the brain and the sacral centres (2).

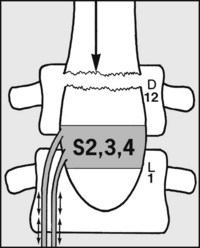

2.102. Neurological control of the bladder contd.:

(c) If the cord is transected above L2 (e.g. by a thoracic spine fracture) voluntary control is lost, but the potential for coordinated contraction of the bladder wall, relaxation of the sphincter and complete emptying remains. (Normally 200–400 mL of urine are passed every 2–4 hours, the reflex activity being triggered by rising bladder pressure or skin stimulation.) (Automatic bladder or cord bladder.)

2.103. Neurological control of the bladder contd.:

(d) Injuries that damage the sacral centres (1) or the cauda (2) prevent coordinated reflex control of bladder activity. Bladder emptying is always incomplete and irregular, and occurs only as a result of distension. Its efficiency varies with the patient’s state of health, the presence of urinary infection, and muscle spasms. (Autonomous or isolated atonic bladder.) In summary, the effects on the bladder are dependent on the level of injury.