Chapter 12 Clinical investigation of hepatopancreaticobiliary disease

Clinical History and Physical Examination

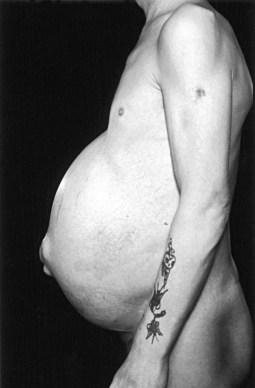

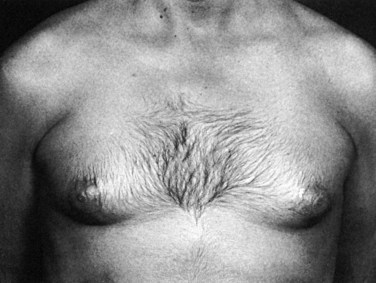

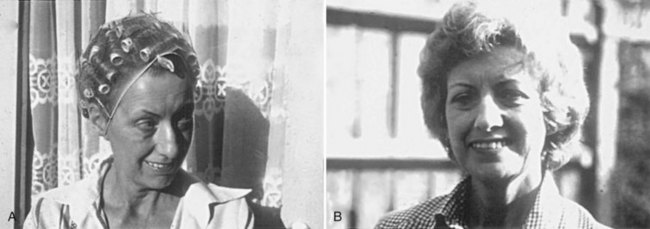

Examination should assess the presence or absence of the stigmata of chronic liver and biliary disease (see Chapter 7), including jaundice, pruritus, spider nevi (Fig. 12.1), hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 12.2), ascites (Fig. 12.3), and caput medusae. Abnormal abdominal masses should also be noted. The circulation in patients with liver failure is hyperdynamic with flushed extremities and a bounding pulse, and peripheral cyanosis may be evident. Fetor hepaticus—a sweet, musty odor of the breath—is associated with hepatocellular failure and is thought to be related to changes in the gut flora (Challenger & Walsh, 1995). Spider nevi are angiomata that occur in the vasculature of the superior vena cava, and their disappearance and reappearance vary with liver function and are thought to be associated with estrogen excess (Bean, 1959). Palmar erythema (Fig. 12.4) affects the thenar and hypothenar eminences and is associated with the hyperdynamic state. Other changes include loss of axillary and pubic hair and whitening of the nails (Lloyd & Williams, 1948). Gynecomastia (Fig. 12.5) and testicular atrophy can also occur.

Chronic encephalopathy associated with portal hypertension and portosystemic shunting varies in severity, producing symptoms that range from mild confusion and a shortened attention span to marked intellectual deterioration that may end in coma. Psychomotor tests have been devised to quantify the intellectual deterioration and allow monitoring (Sherlock & Dooley, 2002). A flapping tremor of the extended wrist (“liver flap”) and later cogwheel rigidity and ankle clonus may be present. Acute liver failure is associated with jaundice, confusion, delirium, and renal failure. These features may occur on a background of cirrhosis, and the precipitating cause may be treatable (e.g., infection).

Patients also may be seen with acute abdominal pain or jaundice. Examination may reveal localized peritonism in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium with a tender mass or generalized peritonitis in cases of gallbladder perforation or severe pancreatitis. A Murphy sign is a “catch” in the breath elicited by gently pressing on the right upper quadrant and asking the patient to take a deep breath. A Boas sign is hyperesthesia of the skin over the lower right ribs posteriorly. One or both of these signs may be found in acute cholecystitis. Erythema ab igne is caused by prolonged local application of heat and may be evident in the right upper quadrant in patients with chronic gallbladder disease or, more commonly, on the back in patients with chronic pancreatitis (Fig. 12.6). In Asia, bleeding from a ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma is a common acute presentation. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis may develop a bluish discoloration of the flanks as a result of retroperitoneal bleeding (Turner sign) or in the periumbilical area (Cullen sign; Fig. 12.7).

Examination of the Liver

The liver is examined using a combination of palpation and percussion from above and below to delineate its borders. Dullness to percussion of the upper border extends as far as the fifth intercostal space. Auscultation is also important, because a venous hum may be heard with portal hypertension, and a bruit may be heard in association with hepatocellular carcinomas. The normal liver is usually impalpable; however, in asthenic individuals, the anterior edge may be palpable. Enlargement of the liver occurs in many pathologic states, although a tonguelike extension from the right lobe—a Riedel lobe, which is of no pathologic significance—may be mistaken for a tumor (Fig. 12.8). Causes of hepatomegaly are listed in Table 12.1. A lobe may undergo hypertrophy and become palpable, and this may occur in the presence of liver atrophy or after liver resection. Reduction in liver size also is important, because this may occur in cirrhosis and certain types of hepatitis. Consistency also is relevant; a hard, knobbly liver often represents the presence of metastases, whereas smooth enlargement may be due to cirrhosis.

| Variant Anatomy |

Examination of the Spleen

Examination of the spleen should begin in the right iliac fossa and proceed toward the left subcostal region, because this is the direction in which splenomegaly occurs. Rotation of the patient 45 degrees to the right may aid palpation, because the spleen then falls onto the examining right hand. During this maneuver, the left hand should support the rib cage and relax the skin and abdominal musculature by drawing these down to the right. Percussion may be useful, and if ascites is present, the spleen may be ballotable. If the spleen is sufficiently enlarged, the notch on its anterior border may become palpable. Causes of splenomegaly are listed in Table 12.2.

| Infection |

Signs of Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension (see Chapter 70A, 74 ) is due to either intrahepatic or extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Intrahepatic portal hypertension usually is associated with hepatomegaly and may be accompanied by splenomegaly and ascites. Dilated abdominal wall veins also may be found secondary to portosystemic anastomosis, giving rise to a caput medusae. The more common clinical site of portosystemic anastomosis is at the gastroesophageal junction, leading to esophageal varices; any evidence of upper gastrointestinal blood loss, whether hematemesis or melena, should be investigated with urgent endoscopy (see Chapter 75A). Rarely, these patients may develop hemorrhoidal varices around the anus as a result of portosystemic anastomosis.

Clinical Features of Other Types of Liver Disease

Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn Disease

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease are associated with hepatobiliary disorders, especially primary sclerosing cholangitis (see Chapter 41). It is important to include a detailed gastrointestinal systems review and investigations in any patient with unexplained liver disease.

Budd-Chiari Syndrome

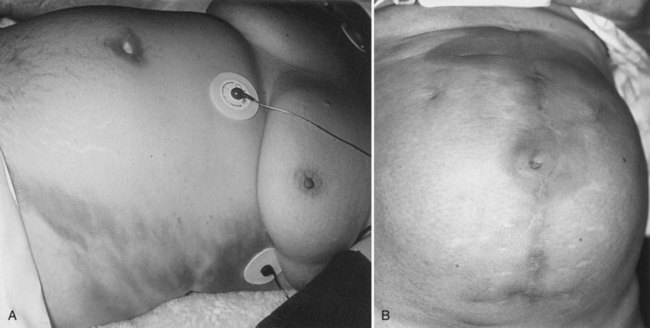

This syndrome is characterized by venous outflow obstruction to the liver, which could be intrahepatic or extrahepatic (see Chapter 77). Acute venous obstruction is usually secondary to another pathologic process and presents with abdominal pain, vomiting, hepatomegaly, ascites, and jaundice, which may be mild. Hepatocellular failure leading to death is usually rapid. Chronic venous obstruction of the liver usually presents with ascites and hepatomegaly. If the inferior vena cava (IVC) is blocked with tumor or thrombus, gross edema of the legs and superficial venous distension of the abdominal veins is apparent. Diagnosis is made on imaging.

Polycystic Disease

Symptoms of polycystic disease are usually caused by the mass effect of the enlarged liver (see Chapter 69A). Abdominal distention and breathlessness are common. Early satiety and vomiting can occur because of pressure on the stomach. Acute abdominal pain is usually due to infection or bleeding into a cyst.

Acute Liver Failure

Acute liver failure (ALF) is characterized by massive cellular injury to a previously healthy liver, and it is associated with the development of hepatic encephalopathy (see Chapter 72). This can occur as a result of paracetamol (acetaminophen) toxicity, usually caused by overdosage, or from a massive viral infection. ALF is associated with a high mortality and requires careful monitoring. Orthotopic liver transplantation is the only effective treatment for this condition, although some cases of ALF can recover spontaneously. Donor organ shortage has dictated the development of criteria that can help to predict whether a patient with ALF has a potential to recover or whether a liver transplant is required. More recently, these criteria have also been used to predict the prognosis of patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma (Kuang et al, 2009). Various sets of criteria have been proposed, of which the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and the King’s College Hospital (KCH) criteria are the best known. Most criteria utilize prothrombin time/INR, serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, arterial blood pH, and hepatic encephalopathy in categorizing patients’ disease severity.

Liver Masses

Patients with large liver masses may be seen initially with right upper quadrant discomfort or a palpable mass in the upper abdomen. More often, liver masses are discovered during imaging as part of the investigation of jaundice, nonspecific abdominal symptoms, or follow-up of malignancy. If the liver mass is discovered incidentally, a full clinical history should be obtained with particular attention to gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Details and duration of oral contraceptive and anabolic steroid use should be recorded. Relevant past history, especially of other malignancies, should be obtained, and the possibility of viral hepatitis should be considered. A thorough abdominal examination should be performed, especially for abnormal masses and ascites, and a digital rectal examination is mandatory at the initial assessment. Signs of jaundice, liver insufficiency, and development of collateral circulation should be sought. A comprehensive hematologic and biochemical screening (Table 12.3) should include an assessment of coagulation factors and of common tumor markers (α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 19-9, CA 125). Cross-sectional imaging evaluation of liver masses is discussed later in this chapter (see Investigation of Hepatobiliary Disease; see also Chapters 16 and 17).

Table 12.3 Laboratory Investigations in Hepatopancreatobiliary Disease

| Hematologic Tests |

Gallbladder and Biliary Tract Disease

Gallbladder

Tenderness and guarding in the right hypochondrium exacerbated by inspiration (Murphy sign) suggests cholecystitis. If the gallbladder is palpable in the presence of obstructive jaundice, this suggests malignant obstruction of the biliary tree (Couvoisier’s law), which is commonly due to carcinoma in the head of the pancreas. Failure to palpate the gallbladder does not exclude malignant disease, however, and a nonpalpable gallbladder is the rule in malignant obstruction at the hilus of the liver. A gallbladder that is intermittently palpable suggests the presence of a periampullary carcinoma (Kennedy & Blumgart, 1971). Gallbladder distension and signs of sepsis in the presence of gallstones may indicate empyema of the gallbladder. In such instances, initial treatment consists of percutaneous aspiration and drainage, with a cholecystectomy delayed for some time.

Acute Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis may begin with a constant dull ache that slowly increases in severity over time, usually a couple of days, and may be associated with anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and pyrexia. It arises as the result of acute inflammation of a distended, obstructed, and usually infected gallbladder (see Chapter 31). Patients may be more comfortable lying still because of the associated localized peritonitis, and coughing or sneezing may exacerbate the pain. Acute cholecystitis is often associated with tenderness (peritoneal irritation) in the right upper quadrant and signs of systemic infection (pyrexia, raised leukocyte count, raised C-reactive protein), and it requires antibiotic therapy to settle the infection. An infected, obstructed gallbladder sometimes ruptures and causes generalized peritonitis or a liver abscess. It is important to examine patients with acute cholecystitis regularly, and if the pain and tenderness do not settle rapidly with antibiotic therapy, percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder or an emergency cholecystectomy may be required.

Biliary colic, which is a clinical entity distinct from acute cholecystitis, usually has a crescendo-decrescendo pattern, with the pain slowly building up to a peak over a few hours; this peak is often associated with vomiting, and the pain then gradually subsides over the ensuing few hours. Often the pain radiates to the back (Berhane et al, 2006), and this pattern of gallbladder pain is thought to arise from gallbladder nociceptors, in response to a rise in intracholecystic pressure caused by strong contraction of the gallbladder against an obstructed neck. Biliary colic usually settles spontaneously, leaving some residual soreness in the right upper quadrant. These attacks of pain can be widely variable in their occurrence, and some patients may have an interval of many years between attacks; others may have almost constant discomfort. Some patients report that the pain is triggered by certain foods, usually fatty foods, and some patients are afraid of eating for fear of triggering an attack of pain (sitophobia).

Cholelithiasis

Symptomatic cholelithiasis is the commonest indication for cholecystectomy. Unfortunately, the symptomatology of gallbladder stone disease has been hard to define despite research spanning decades (Johnson & Jenkins, 1975; see Chapter 30). A large epidemiologic investigation in Denmark into the relationship between abdominal symptoms and gallstones concluded that the predictive values of various abdominal symptoms for gallstones were very low. In patients with gallstones, the prevalence of right upper quadrant abdominal pain was similar to patients without gallstones but was higher in patients who had previously undergone cholecystectomy (Jorgensen, 1989). A larger, multicenter Italian study, MICOL, showed that in an Italian population, the presence of epigastric or right upper quadrant pain radiating to the right shoulder that forced the patient to rest and intolerance to fried or fatty food were good predictors of gallstones (Corazziari et al, 2008). A recent Swedish study that followed up 503 patients without gallstones for 5 years reported that the incidence of gallstone formation was 1.39 per 100 person-years, and that no change was seen in the symptoms of these patients before and after development of gallstones (Halldestam et al, 2009).

Studies examining the relief of symptoms after cholecystectomy suggest that approximately one quarter of patients undergoing cholecystectomy will not experience relief of symptoms, and that dyspeptic symptoms are least likely to be cured by cholecystectomy (Weinert et al, 2000; Jorgensen et al, 1991). A study comparing the symptomatic outcomes after cholecystectomy for functioning and nonfunctioning gallbladders showed no difference in outcome (Larsen et al, 2007). An important study outlined the variation in perceptions of what was considered a valid indication for cholecystectomy (Scott & Black, 1991). These authors showed the case histories of 252 patients to two panels, one comprising surgeons and the other a mixed panel of doctors. The mixed panel considered 41% of the operations appropriate for the indications and 30% inappropriate, but the surgeons considered 52% appropriate and 2% inappropriate but could not agree on the other 46%. It is therefore important that an accurate documentation of dyspeptic or atypical symptoms be made, and patients should be counseled that cholecystectomy may not relieve any of their symptoms.

Biliary Obstruction

Classically, pain is a discriminating feature in jaundiced patients. Patients with biliary tract obstruction resulting from tumor usually have painless jaundice (see Chapters 50A through 50D and Chapter 58B), whereas patients with an acute attack of pain or a long history of intermittent episodes of jaundice accompanied by pain frequently have gallstone disease (see Chapter 35). In the event of cholangitis, rigors and fever also are present. Jaundice unaccompanied by pain, and especially if the gallbladder is palpable, almost always indicates malignancy. Back pain usually indicates a pancreatic lesion; chronic pancreatitis and tumors of the pancreas can manifest in this manner. Patients with chronic pancreatitis occasionally are seen with jaundice, especially during an acute-on-chronic attack, and the jaundice may be accompanied by symptoms of endocrine and exocrine deficiency (diabetes, steatorrhea, malabsorption; see Chapter 55A).

Malignant disease affecting the hepatic ducts at the biliary confluence in the hilus of the liver often presents with jaundice (Fig. 12.9), but in such instances, the gallbladder is not palpable (see Chapter 50B). Itching can be an initial feature of biliary obstruction (Fig. 12.10), but in prolonged cholestasis, itching may occur in association with partial biliary obstruction and significantly in primary biliary cirrhosis. Alkaline phosphatase often is markedly increased in partial biliary obstruction, even though the bilirubin may be only marginally elevated. A markedly increased or increasing alkaline phosphatase level may be the only sign of an early malignant or benign biliary stricture.

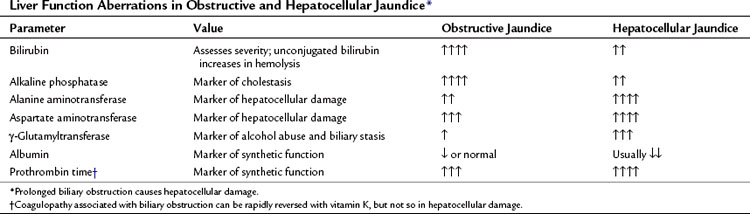

The distinction between obstructive (surgical) jaundice and hepatocellular (medical) jaundice is seldom the problem it was in the past. Hematologic and biochemical tests of liver function (Table 12.4) usually indicate whether the jaundice is obstructive, but this is not always the case. Identification of the cause and level of biliary obstruction is essential. Ultrasound (Chapter 13) is the preferred initial imaging test for diagnosis of biliary obstruction and to determine the etiology and level of obstruction. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP; see Chapters 16 and 17) are also extremely useful for evaluation of biliary obstruction.

Acalculous Biliary Pain

Acalculous biliary pain is considered to be the result of a “functional” motor disorder of the gallbladder and/or sphincter of Oddi (Behar et al, 2006). Gallbladder motor dysfunction giving rise to abdominal pain has been defined by the Rome II Committee on Functional Biliary and Pancreatic Disorders as episodes of severe, steady pain located in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant and all of the following: episodes last 30 minutes or more, symptoms have occurred on one or more occasions in the previous 12 months, the pain is steady and interrupts daily activities or requires consultation with a physician, no evidence of structural abnormalities explains the symptoms, and gallbladder function is abnormal with regard to emptying. To eliminate calculous disease from the differential diagnosis, the Rome II Committee recommendations in the evaluation of these patients includes screening tests: upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, liver biochemisty, pancreatic function tests, and ultrasound of the gallbladder should be normal, and microlithiasis of bile should be excluded by endoscopic aspiration at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or by aspiration of bile from the duodenum after stimulation by cholecystokinin (CCK) or magnesium sulfate. The recommended tests for gallbladder function are CCK cholescintigraphy assessment of gallbladder emptying, CCK- or meal-stimulated ultrasonographic volumetry of the gallbladder, and CCK-induced pain provocation tests. The Committee recommended that abnormal gallbladder emptying after CCK stimulation (<40% ejection) is an acceptable indication for cholecystectomy, as medical therapies are usually not effective (Corazziari et al, 1999).

Unfortunately, no consensus exists regarding the infusion rate of CCK that in turn can directly influence gallbladder emptying. Delgado-Aros and colleagues (2003) and DiBaise and Oleynikov and colleagues (2003) reported meta-anlayses of studies examining the symptomatic benefit from cholecystectomy based on abnormal CCK-stimulated gallbladder emptying. They found no good evidence to support the use of CCK-stimulated gallbladder ejection fraction to select patients for cholecystectomy. Similar findings were reported by Rastogi and colleagues (2005). Smythe and colleagues (1998) conducted a critical evaluation of CCK-provoked gallbladder pain and concluded that this test was not a predictor of symptomatic relief after cholecystectomy. It is interesting to note that in a prospective randomized study examining the development of symptoms in patients with uncomplicated gallbladder stones, a CCK-stimulated ejection fraction greater than 60% was independently associated with the development of symptoms.

The etiology and pathogenesis of calculous and acalculous gallbladder pain are poorly understood despite some recent insights by mathematical modeling (Li et al, 2007, 2008; Bird et al, 2006; Wegstapel et al, 1999; Ooi et al, 2004; Ahmed et al, 2000). We would therefore currently recommend that patients experiencing recurrent and severe symptoms as defined by the Rome II criteria should be offered cholecystectomy but should be carefully counseled regarding the uncertainty of its outcome, and this counseling should be clearly documented.

Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction

Sphincter of Oddi (SO) dysfunction may be present in patients with an intact biliary tree, but it usually comes to light as a potential diagnosis when symptoms continue after a cholecystectomy. SO dysfunction has been subclassified into a biliary or pancreatic type. Biliary type SO dysfunction in postcholecystectomy patients has been arbitrarily subclassified into types I, II, and III. Type I SO dysfunction is defined as pain, elevated liver function tests documented on two or more occasions, delayed contrast drainage, and a dilated common bile duct with a corrected diameter of 12 mm or more at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Type II SO dysfunction is characterized as pain only with one or two of the criteria in Type I. Type III SO dysfunction is defined as recurrent biliary-type pain with none of the criteria from type I. Toouli (2009) concluded that accurate sphincter manometric data is crucial to establish a diagnosis of SO dysfunction. Invasive investigation of sphincter dysfunction and/or sphincterotomy is associated with a risk of pancreatitis in up to 30% of patients. Insertion of prophylactic pancreatic stents are advocated as a means of reducing this risk, and some evidence exists to support this practice. Injection of botulinum toxin into the sphincter also has been advocated as a “therapeutic test” before a sphincterotomy is performed. In a literature review, Sgouros and Pereira (2006) concluded that biliary sphincterotomy reliably treats symptoms in 85%, 69%, and 37% of patients with types I, II, and III SO dysfunction, and pancreatic sphincterotomy may benefit up to 75% of patients. They state that sphincter manometry is the gold standard in the investigation. Pancreatic type SO dysfunction is also subclassified into types I, II, and III according to whether pancreatic enzymes are elevated soon after an attack of pain and whether the pancreatic duct is dilated greater than 5 mm.

Iatrogenic Biliary Injury

Patients with iatrogenic damage to the biliary tract (see Chapter 102) may not only present with jaundice because of biliary stricture but also may present with biliary leakage, resulting in biliary peritonitis or fistula. In such patients it is important to obtain a good history that includes a copy of the original operative report, which may offer an indication as to the level and nature of the injury and may provide a baseline for comparison with further investigations. Many patients may present with biliary and abdominal sepsis, and blood and bile cultures should be obtained. If a biliary fistula is present, or if the patient is deeply jaundiced, coagulation may be deranged. Liver function tests may show biochemical evidence of biliary obstruction or of liver damage, and patients are often nutritionally depleted and may be anemic. Ongoing liver damage may be present, resulting from a combination of sepsis and biliary obstruction.

Pancreas

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is usually accompanied with severe upper abdominal pain that develops rapidly, becomes constant, and persists for several hours (see Chapter 53). The pain typically starts in the epigastrium but may soon spread throughout the abdomen and radiate into the back. Sometimes the patient may find relief by sitting forward, but usually they lie still and curled up in bed. The pain can be so sudden in onset that at times, it can simulate a perforated peptic ulcer, and indeed acute pancreatitis can mimic almost every cause of acute abdominal pain and may even produce chest pain that simulates myocardial infarction, pneumonia, or pleurisy. Frequent vomiting and sequestered fluid in the small bowel may lead to rapid and severe dehydration. Even keeping the stomach empty with a nasogastric tube may not prevent the patient from retching, and marked nausea is almost a constant feature. Hiccoughs can also occur due to diaphragmatic irritation secondary to extension of the inflammatory process tracking up via the retroperitoneum.

Rarely, acute pancreatitis can occur without severe pain, and in these cases, the diagnosis can be missed, and such failure may be associated with a poor prognosis (Lankisch et al, 1991). It is important to be aware of the condition and consider it in any patient who develops sudden shock or anuria, especially if it follows biliary surgery, ERCP, coronary artery bypass, or trauma. A detailed history is therefore vital, particularly inquiring as to the past medical history and family history, especially in children. Any history of alcohol abuse, bilary colic, jaundice, recent surgery, or ERCP should be actively sought.

Most cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with alcohol abuse or biliary disease but can also follow ERCP; abdominal surgery, especially to the stomach, duodenum, and biliary tree; coronary artery bypass surgery; trauma; and certain viral illnesses, especially mumps. The association with alcohol abuse varies according to country and urbanization, being as high as 65% in parts of urban America. Biliary disease is responsible for over 30% of cases in a general population, and sieving the feces of patients with gallstone-associated pancreatitis shows gallstones present in a high proportion of them (Kelly, 1976), prompting many to speculate that the pancreatitis resulted from the temporary lodging of a stone in the ampulla of Vater. Postoperative pancreatitis accounts for 5% to 10% of cases (Thompson et al, 1988), and hyperamylasemia can occur in about 10% of patients undergoing ERCP, although only 1% will develop severe acute pancreatitis. The cause of traumatic pancreatitis is again subject to geographical variation (Jones, 1985); penetrating trauma is more common in the United States and blunt trauma and injury as a result of traffic accidents are more common in the United Kingdom. Other rare causes include hyperparathyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and certain drugs including steroids, azothiaprine, and diuretics (Nakashima & Howard, 1977). However, once all these causes have been excluded, for about 25% of patients, no clear etiology is identified. The sex ratio for acute pancreatitis is virtually equal but tends to have a higher peak age incidence in women, reflecting the higher incidence of gallstones; in men the lower peak age reflects their propensity to alcohol abuse.

Chronic Pancreatitis

There are few pathognomonic or diagnostic signs for chronic pancreatitis, and diagnosis usually depends on the history and special investigations (see Chapter 55A). The patient may appear malnourished with signs of weight loss, they may be icteric as a result of compression of the common bile duct by the fibrotic process in the head of the pancreas, and erythema ab igne may be present on the back or abdomen. Uncommonly, a palpable mass, pseudocyst, or splenomegaly may be evident, and occasionally pancreatic ascites, if there has been rupture of a pseudocyst or of the duct system.

Chronic pancreatitis is a difficult condition both to diagnose and to treat. It is crucial to exclude other associated conditions, such as pancreatic cancer; but once the diagnosis is established, it is important to 1) identify any predisposing cause, 2) stage the severity of the disease, and 3) document any morphologic and functional changes against which any progression can be assessed. One of the commonest predisposing factors is alcohol abuse, although chronic pancreatitis is also associated with biliary disease, congenital abnormalities such as an annular pancreas (Dowsett et al, 1989), ductal abnormalities, and rarely with hyperparathyroidism. An autosomal dominant hereditary form of the condition may also be a factor, so a family history is crucial (Teich, 2008). Rarely is any specific drug or dietary factor implicated.

Other presenting symptoms include marked steatorrhoea resulting from diminished lipase production and inadequate fat absorption (Di Magno, 1982). The stool frequency may be increased up to six times a day, and the stools themselves become pale and bulky with an offensive odor, and they float, making them difficult to flush away. However, this is not a constant feature of chronic pancreatitis; some patients may even suffer from constipation as a result of the increased use of opiate analgesia.

Pancreatic Cancer

Regretfully, physical signs of pancreatic cancer are often absent or infrequent, until the lesion is unresectable (see Chapter 58B). The patient may be symptomatic with weight loss, but unless the lesion is situated in the head of the pancreas such that it obstructs the common bile duct early, causing obstructive jaundice, few other signs may be evident. With distal bile duct obstruction, the gallbladder may become distended (Courvoisier gallbladder). An abdominal mass and ascites are late signs and usually herald inoperability. Systemic signs such as flitting thrombophlebitis migrans may be apparent, but this is uncommon and nonspecific. All too often cachexia is the only physical finding.

Later clinical features of pancreatic cancer are pain, weight loss, and jaundice. The pain is often severe and gnawing and radiates to the back. It is often worse at night, when the patient is lying flat, which usually indicates tumor extension to the retroperitoneum, often signifying irresectability. Weight loss may be marked, and in many cases of tumors in the body of the pancreas, weight loss may be the only symptom, until pain indicates invasion of the peripancreatic tissue. The more rapid the weight loss, the less likely the lesion is to be resectable (Bakkevold et al, 1992). Jaundice can be associated with severe pruritus, but this classical presentation only occurs when the lesion is in the head of the pancreas; when jaundice occurs with tumors of the body or tail of the pancreas, it usually signifies hilar liver or nodal metastases.

About 5% of patients with pancreatic cancer will have developed diabetes mellitus within the 2 years prior to diagnosis (Pannala et al, 2009). Other signs such as ascites, an epigastric mass, or enlarged supraclavicular nodes (Virchow sign) are indications of inoperability. Because of the lack of specific signs and symptoms, very commonly a diagnostic dilemma arises as to whether a lesion is chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer. Frequently, diagnostic imaging cannot provide the answer, and even at operation it may not be apparent which condition the surgeon is facing; this occured in up to 15% of cases in some series (Mao et al, 1995).

Investigation of Hepatobiliary Disease

All patients with suspected hepatobiliary and pancreatic disease should undergo a comprehensive hematologic and biochemical screening, including an assessment of clotting capability. The history may dictate additional serologic tests—tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein, CA 19-9, CEA—and immunologic tests, such as a viral hepatitis screening. Particular attention needs to be paid to the platelet count, coagulation profile, and liver function tests (see Tables 12.3 and 12.4).

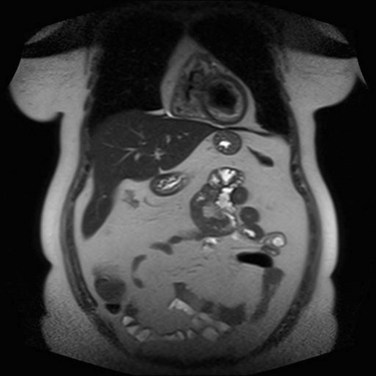

Imaging of incidentally discovered liver masses should be directed toward characterizing the liver lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually highly specific in characterizing liver masses (Seneterre et al, 1996), and it can be used to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions (see Chapter 17). Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is mandatory in patients with suspected malignancy of the liver to exclude extrahepatic disease and to determine resectability (see Chapter 16). In the presence of resectable disease, liver biopsy is seldom indicated, because many lesions can be characterized by imaging and clinical features; biopsy is generally reserved for patients with nonresectable tumors that require histopathologic confirmation prior to instituting therapy (Thompson et al, 1985).

It is important to assess the patient in terms of fitness for surgery, nutritional status, cardiorespiratory and renal function, and parenchymal liver disease. It is vital to be aware of the Child-Pugh stage of the liver disease before planning any treatment of hepatocellular cancer (see Chapter 80). An array of autoantibodies is used to diagnose autoimmune hepatobiliary disorders, and some of these are listed in Table 12.3.

Cardiorespiratory disease and fitness for surgery are assessed during history taking and may indicate the need for further detailed study. These additional investigations are often conducted with advice from anesthesiologists, in the event a major surgical procedure is contemplated. Nutritional status can be determined crudely by hemoglobin, protein, and albumin levels and is often abnormal, especially if liver function has been compromised for a long time. Continuous fine-bore enteral tube feeding may be instituted in these patients to try to optimize nutritional status before surgery (Allison, 2004; Lidder & Lewis, 2004). If renal function is abnormal, creatinine clearance quantifies the problem and may indicate the need for renal support in the perioperative period (Thompson et al, 1987).

Many patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic disease may have undergone instrumentation of the biliary tract. ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography may have been employed. Biliary sepsis is extremely common after these procedures (Brody et al, 1998; Heslin et al, 1998; Povoski et al, 1999). If external biliary drainage has been used, it is important to culture the biliary output, even if no evidence of systemic sepsis is present. In such cases, no immediate indication for antimicrobial therapy is apparent, but culture and sensitivity will guide future therapy. In particular, perioperative antibiotic therapy is indicated in these patients. Systemic sepsis requires urgent broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, subsequently guided by the results of blood culture and sensitivity tests. Patients with long-standing partial biliary obstruction and sepsis have a high likelihood of fungal infections.

Colorectal Liver Metastases

Liver metastases from primary colorectal cancer are frequently discovered at the time of diagnosis on the staging CT scan (see Chapter 81A). Metastases may occasionally be detected during operation on the primary tumor, especially if this is done as an emergency procedure. They are also frequently discovered as metachronous tumors during follow-up after resection of primary colorectal cancer. Follow-up strategies in patients with colorectal cancer are a subject of much debate, and no clear consensus exists. In patients with no perioperatively detected metastatic disease and an R0 colonic resection, it is advisable to image the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast-enhanced CT scan at 9 months and 2 years postresection. If metachronous liver metastases are detected, resectability is determined by the patient’s ability to undergo potentially major liver surgery by the location and segmental distribution of the hepatic metastases and by the presence of extrahepatic disease. Positron emission tomography (PET) and CT scan can be most useful in this regard (see Chapter 15). Recent reports have shown added benefit of contrast-enhanced MRI scan to determine resectability (Blyth et al, 2008; Hekimoglu et al, 2009). Synchronously detected liver metastases may be resected at the time of the resection of the primary lesion or as a second procedure, sometimes after the administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Investigation of Patients With Pancreatic Disease

In patients with acute pancreatitis (see Chapters 53 and 54), diagnosis usually is made based on the history and the serum amylase and lipase levels. An elevated serum amylase can fall quite rapidly, and it may be normal if measured 2 to 3 days after the onset of the attack. Urinary amylase may be elevated in these patients, however, a contrast-enhanced CT scan often confirms the diagnosis but is particularly poor at identifying gallstones. An ultrasound scan is usually the first investigation of choice, because it detects gallstones and allows the patient to proceed to endoscopy and endoscopic sphincterotomy when appropriate. In patients with acute pancreatitis, the duodenum and small bowel often are filled with gas, and detection of common bile duct stones is less reliable.

In patients who remain unwell 1 week after onset, or in those who deteriorate after initial improvement, pancreatic necrosis should be suspected, and a contrast-enhanced CT scan should be performed (British Society of Gastroenterology, 2005). Patients judged to have a severe attack of pancreatitis at onset are at high risk of developing a systemic inflammatory response syndrome and require very careful and repeated observation with attention to fluid balance, nutrition, and sepsis. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy in this group of patients is useful and may prevent the development of infected pancreatic necrosis. Patients with clinically and biochemically severe pancreatitis should be managed in conjunction with critical care physicians in a suitable environment. Patients may go on to develop pancreatic pseudocysts that may cause pain or other effects as a result of pressure on neighboring organs, especially the stomach. Nausea, vomiting, or early satiety should alert the physician, as these pseudocysts are easily detectable on CT scanning. Continuing evidence of systemic sepsis usually indicates the presence of infected pancreatic necrosis, which can be confirmed by fine needle aspiration.

It may be difficult to differentiate between pancreatic carcinoma and some cases of chronic pancreatitis, as there are no clear-cut markers for this, although lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis is usually accompanied by an elevated serum IgG. The tumor marker CA 19-9 has a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 75% for pancreatic cancer (Kim et al, 1999), but as the level tends to correspond with tumor volume, potentially curative tumors may be associated with normal levels (Eloubeidi et al, 2004; Schlieman et al, 2003), which limits its use as a screening tool. Very high levels of CA 19-9 are associated with a higher incidence of metastatic disease (Maithel et al, 2008), and laparoscopy is advocated to determine the presence of subradiological metastatic disease in patients with a CA 19-9 level above 150 kU/L (nonjaundiced patients) and above 300 kU/L in jaundiced patients (Halloran et al, 2008).

A contrast-enhanced spiral CT scan using thin (3 to 5 mm) slices provides information as to the extent and nature of any mass and in particular helps differentiate solid from cystic lesions, vascular involvement or encasement, and lymph node metastases. No significant advantage of gadolinium-enhanced MRI over multidetector CT has been seen in the staging of pancreatic cancer (Park et al, 2009), but multidetector CT has a better diagnostic yield (Satoi et al, 2009). MRCP can be useful in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic masses and duct delineation, and endoscopic ultrasound may contribute substantially to the assessment of ampullary tumors (Kahaleh et al, 2004), for image-guided aspiration of pancreatic cysts, and to obtain biopsies of intrapancreatic tumors.

Ahmed R, et al. In vitro responses of gallbladder muscle from patients with acalculous biliary pain. Digestion. 2000;61(2):140-144.

Allison S. Fluid, electrolytes and nutrition. Clin Med. 2004;4(6):573-578.

Bakkevold KE, et al. Carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater: presenting symptoms, signs, and diagnosis related to stage and tumour site: a prospective multicentre trial in 472 patients. Norwegian Pancreatic Cancer Trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27(4):317-325.

Bean WB. Vascular Spiders and Related Lesions of the Skin. Oxford UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1959.

Behar JC, et al. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1498-1509.

Berhane TV, et al. Pain attacks in non-complicated and complicated gallstone disease have a characteristic pattern and are accompanied by dyspepsia in most patients: the results of a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(1):93-101.

Bird NC, et al. Investigation of the functional three-dimensional anatomy of the human cystic duct: a single helix? Clin Anat. 2006;19(6):528-534.

Blyth S, et al. Sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of colorectal liver metastases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90(1):25-28.

British Society of Gastroenterology. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 3):1-9.

Brody LA, et al. Clinical factors associated with positive bile cultures during primary percutaneous biliary drainage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9(4):572-578.

Challenger F, Walsh JM. Foetor hepaticus. Lancet. 1995;1:1239.

Corazziari E, et al. Gallstones, cholecystectomy and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) MICOL population-based study. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(12):944-950.

Corazziari E, et al. Functional disorders of the biliary tract and pancreas. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II48-II54.

Delgado-Aros S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: does gallbladder ejection fraction on cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy predict outcome after cholecystectomy in suspected functional biliary pain? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(2):167-174.

DiBaise JK, Oleynikov D, et al. Does gallbladder ejection fraction predict outcome after cholecystectomy for suspected chronic acalculous gallbladder dysfunction? A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(12):2605-2611.

Di Magno EP. Controversies in the treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:737-742.

Dowsett JF, et al. Annular pancreas: a clinical, endoscopic and immunohistochemical study. Gut. 1989;30(1):130-135.

Eloubeidi MA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(3):209-213.

Halldestam I, et al. Incidence of and potential risk factors for gallstone disease in a general population sample. Br J Surg. 2009;96(11):1315-1322.

Halloran CM, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 accurately selects patients for laparoscopic assessment to determine resectability of pancreatic malignancy. Br J Surg. 2008;95(4):453-459.

Hekimoglu K, et al. Small colorectal liver metastases: detection with SPIO-enhanced MRI in comparison with gadobenate dimeglumine–enhanced MRI and CT imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(3):468-472.

Heslin MJ, et al. A preoperative biliary stent is associated with increased complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. Arch Surg. 1998;133:149-154.

Johnson AG, Jenkins A. Flatulent dyspepsia: a tiered symptom complex? Med Hypotheses. 1975;1(6):204-206.

Jones RC. Management of pancreatic trauma. Am J Surg. 1985;150(6):698-704.

Jorgensen T. Abdominal symptoms and gallstone disease: an epidemiological investigation. Hepatology. 1989;9(6):856-860.

Jorgensen T, et al. Persisting pain after cholecystectomy: a prospective investigation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26(1):124-128.

Kahaleh M, et al. Factors predictive of malignancy and endoscopic resectability in ampullary neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(12):2335-2339.

Kennedy A, Blumgart LH. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater and duodenum. J Clin Pathol. 1971;24:765.

Kelly TR. Gallstone pancreatitis: pathophysiology. Surgery. 1976;80(4):488-492.

Kim H, et al. A new strategy for the application of CA19-9 in the differentiation of pancreaticobiliary cancer: analysis using a receiver operating characteristic curve. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;94:1941-1946.

Kuang YH, et al. Predicting morbidity and mortality after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of Model for End-stage Liver Disease score. World J Surg. 2009;33:2412-2419.

Lankisch PG, et al. Undetected fatal acute pancreatitis: why is the disease so frequently overlooked? Amer J Gastroent. 1991;86:322-326.

Larsen TK, et al. The influence of gallbladder function on the symptomatology in gallstone patients, and the outcome after cholecystectomy or expectancy. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):760-763.

Li WG, et al. One-dimensional models of the human biliary system. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129(2):164-173.

Li WG, et al. Non-Newtonian bile flow in elastic cystic duct: one- and three-dimensional modeling. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(11):1893-1908.

Lidder PG, Lewis S. Perioperative and postoperative nutrition. Hosp Med. 2004;65(12):717-720.

Lloyd CW, Williams RH. Endocrine changes associated with Laennec’s cirrhosis of the liver. Am J Med. 1948;4(3):315-330.

Maithel SK, et al. Preoperative CA 19-9 and the yield of staging laparoscopy in patients with radiographically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(12):3512-3520.

Mao C, et al. Observations on the development patterns and the consequences of pancreatic exocrine adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1995;130:125.

Nakashima YH, Howard JM. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145:105-109.

Ooi RC, et al. The flow of bile in the human cystic duct. J Biomech. 2004;37(12):1913-1922.

Pannala RB, et al. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:88-95.

Park HS, et al. Preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cancer: comparison of gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography versus MDCT. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(3):586-595.

Povoski SP, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage: impact on intraoperative bile cultures and infectious morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(5):496-505.

Rastogi A, et al. Controversies concerning pathophysiology and management of acalculous biliary-type abdominal pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(8):1391-1401.

Satoi S, et al. Pre-operative patient selection of pancreatic cancer patients by multi-detector row CT. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(90):529-534.

Schlieman MG, et al. Utility of tumor markers in determining resectability of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:951-956.

Scott EA, Black N. Appropriateness of cholecystectomy in the United Kingdom: a consensus panel approach. Gut. 1991;32(9):1066-1070.

Seneterre E, et al. Detection of hepatic metastases: ferumoxides-enhanced MR imaging versus unenhanced MR imaging and CT during arterial portography. Radiology. 1996;200(3):785-792.

Sgouros SP, Pereira SP. Systematic review: sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: non-invasive diagnostic methods and long-term outcome after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(2):237-246.

Sherlock S, Dooley J. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System. Oxford UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2002.

Smythe A, et al. A requiem for the cholecystokinin provocation test? Gut. 1998;43(4):571-574.

Teich NM. Hereditary chronic pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:115-130.

Thompson JB, et al. Post-operative pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:377-380.

Thompson JN, et al. Focal liver lesions: a plan for management. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6482):1643-1645.

Thompson JN, et al. Renal impairment following biliary tract surgery. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):843-847.

Toouli J. Sphincter of Oddi: function, dysfunction, and its management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(Suppl 3):S57-S62.

Wegstapel HB, et al. The relationship between in vivo emptying of the gallbladder, biliary pain, and in vitro contractility of the gallbladder in patients with gallstones: is biliary colic muscular in origin? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(4):421-425.

Weinert CA, et al. Relationship between persistence of abdominal symptoms and successful outcome after cholecystectomy. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(7):989-995.