Chronic and subacute viral infections of the CNS

Chronic/subacute viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) tend to progress over months or years rather than days or weeks. The incubation period is usually considerably longer than that of acute viral infections. In the past, classifications of chronic (slow) virus infections have included Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and other spongiform encephalopathies (prion diseases), but according to current understanding of the pathogenesis of these diseases this designation is inappropriate. Prion diseases are considered in Chapter 32.

SUBACUTE MEASLES ENCEPHALITIDES

MEASLES INCLUSION BODY ENCEPHALITIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

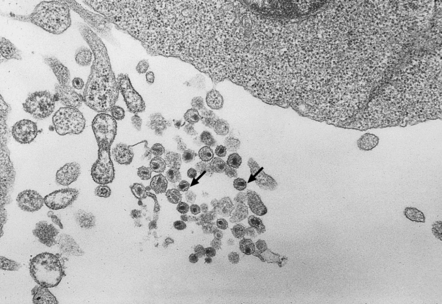

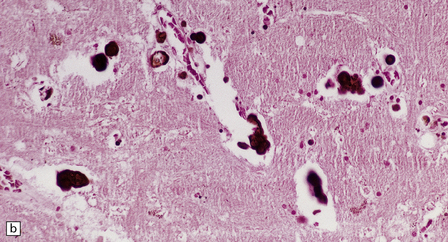

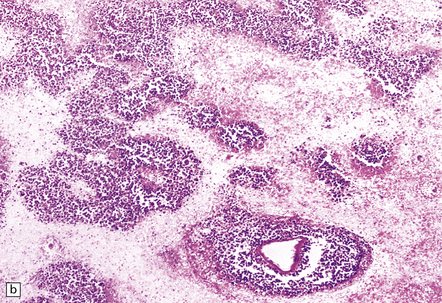

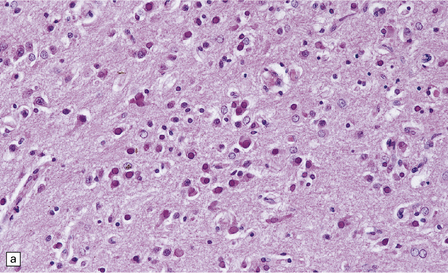

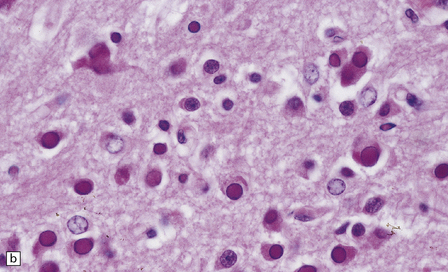

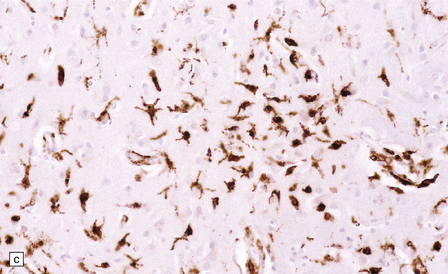

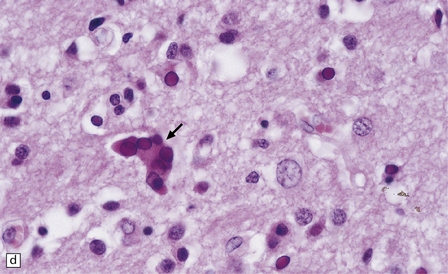

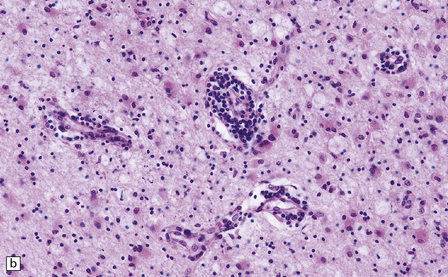

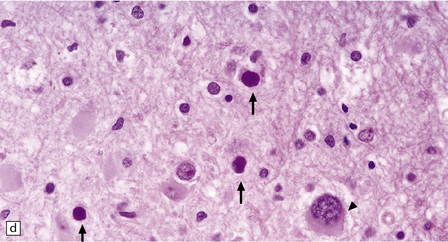

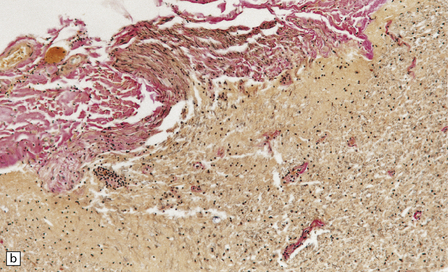

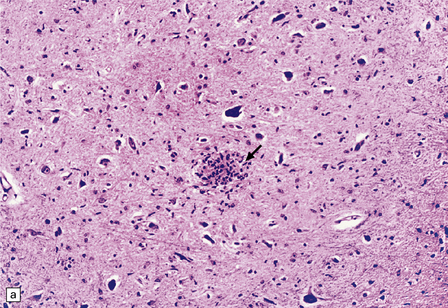

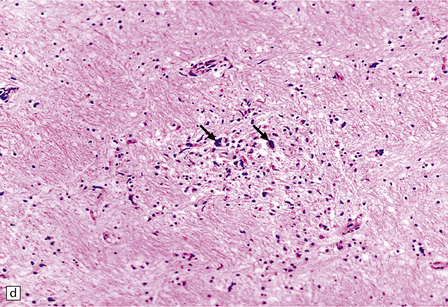

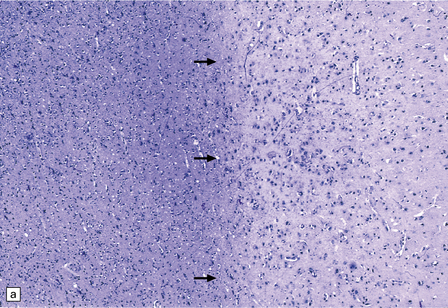

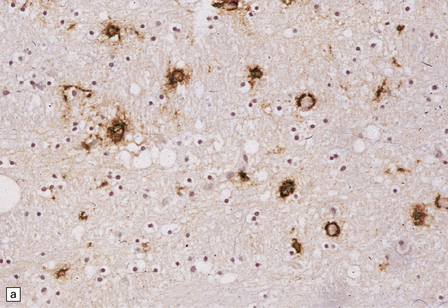

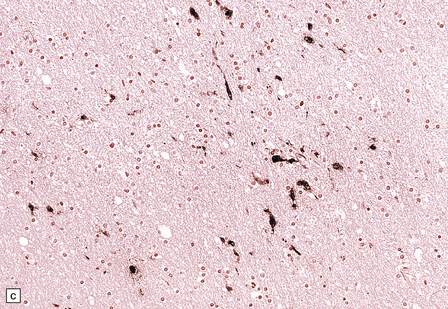

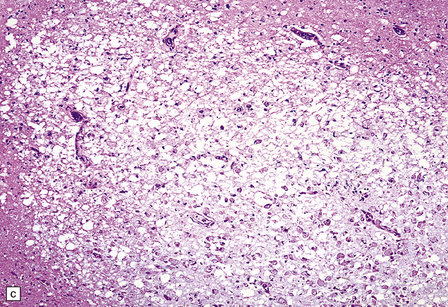

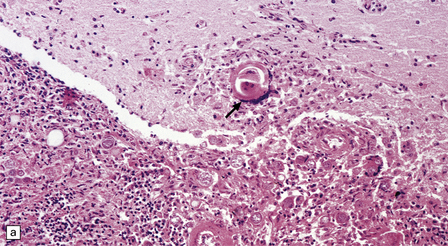

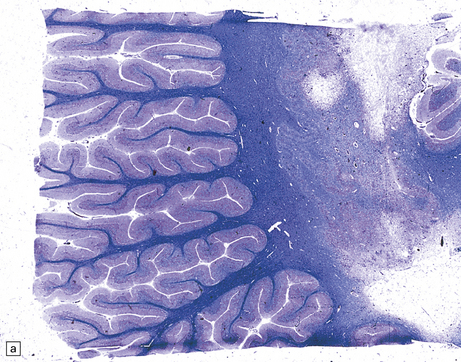

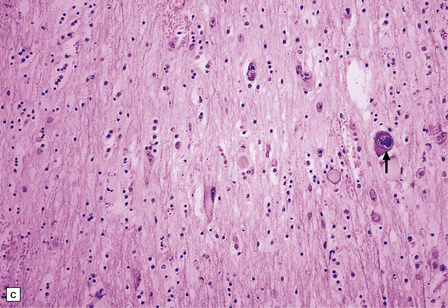

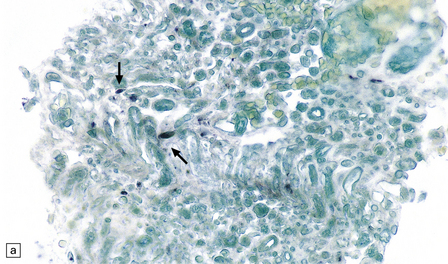

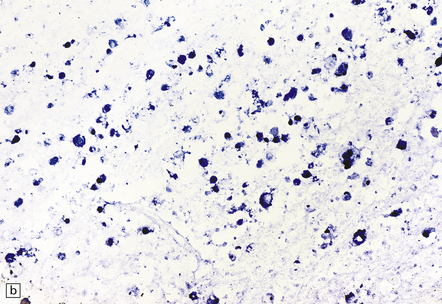

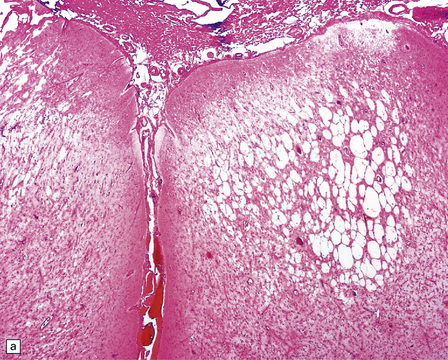

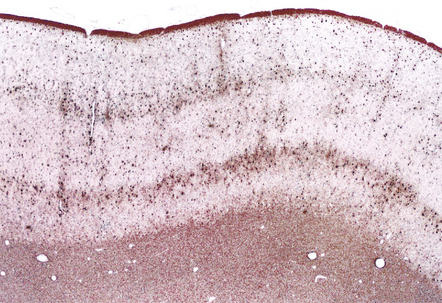

Macroscopically, the brain usually appears normal, although there may be foci of softening and discoloration. Histology reveals occasional or numerous foci of hypercellularity (Fig. 13.1), within which many neurons and some astrocytes and oligodendrocytes contain eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Fig. 13.1). Most of these are intranuclear, largely filling the nucleus, apart from a few pyknotic clumps of marginated chromatin. Less well-defined eosinophilic inclusions may be visible in the cytoplasm. The lesions also contain reactive astrocytes and microglia, and occasional multinucleated cells. The lesions occur in any part of the brain. The inclusions are readily seen in hematoxylin–eosin preparations and can also be demonstrated immunohistochemically or by electron microscopy (Fig. 13.1).

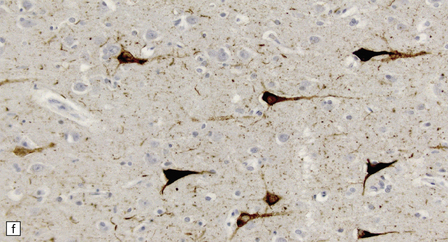

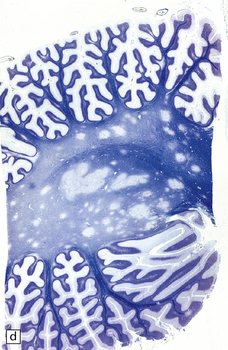

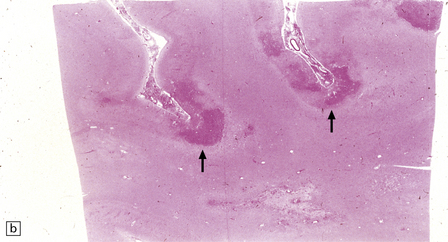

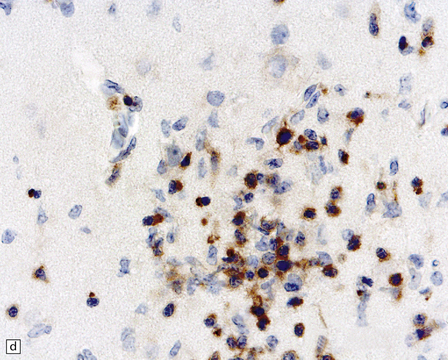

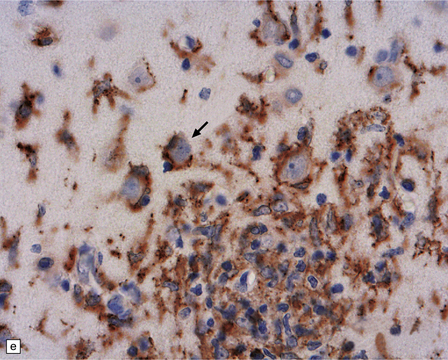

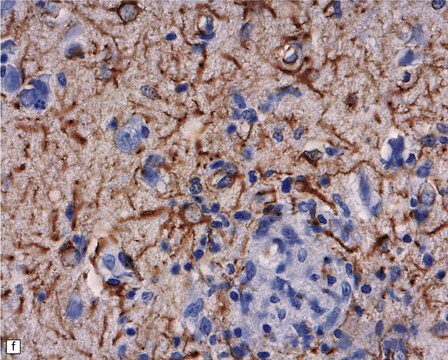

13.1 Measles inclusion body encephalitis.

(a) Focus of hypercellularity in the cerebral cortex. (b) Inclusion bodies are prominent. They fill the nuclei of neurons and glia. Eosinophilic inclusions are also visible in the cytoplasm of some of the cells. (c) Clusters of CD68-immunoreactive microglia within a focus of hypercellularity. (d) Multinucleated cell (arrow) with nuclear inclusion bodies. (e) Immunohistochemical demonstration of measles virus antigen. In contrast to the paucity of viral antigen in SSPE, in measles inclusion body encephalitis antigen is abundant. (f) Measles virus nucleocapsid particles in the nucleus of an infected neuron.

SUBACUTE SCLEROSING PANENCEPHALITIS (SSPE)

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

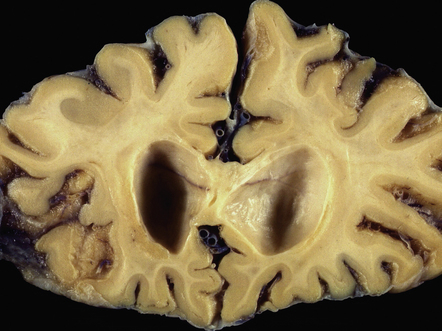

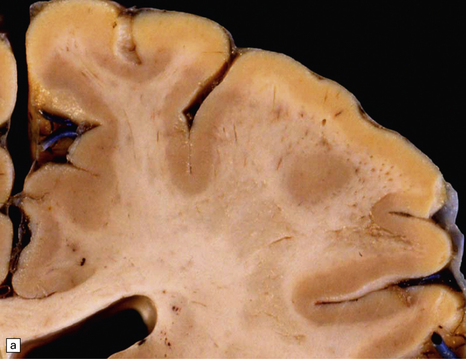

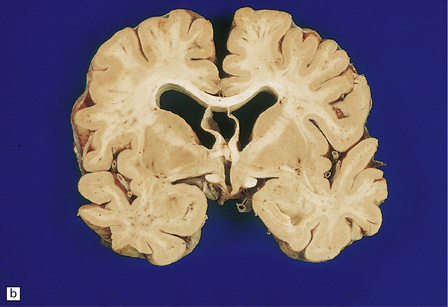

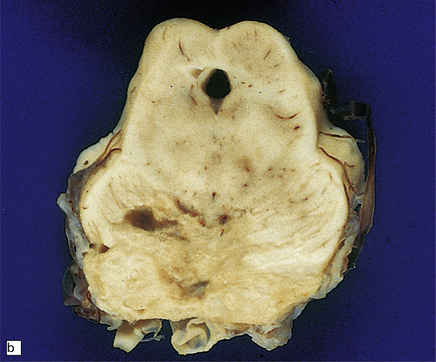

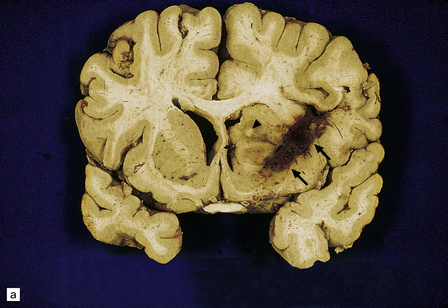

Often the brain is macroscopically normal. However, in cases of longer duration, there is usually moderate to marked brain atrophy and the white matter may have an abnormally firm texture and a mottled gray appearance that can simulate a leukodystrophy (Fig. 13.2).

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

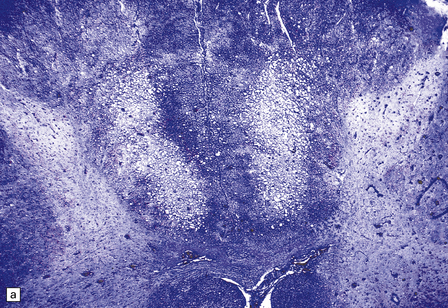

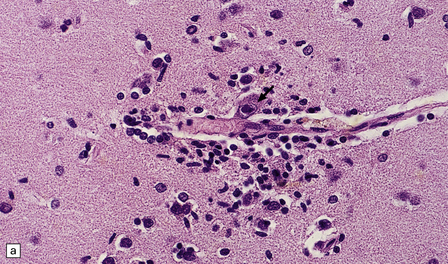

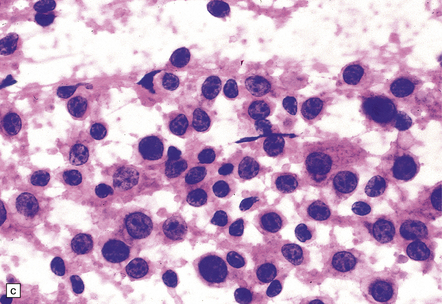

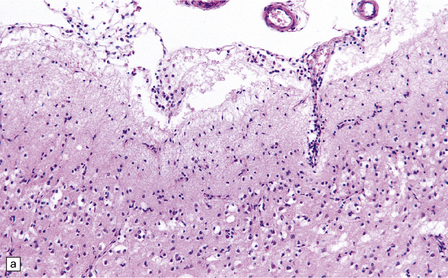

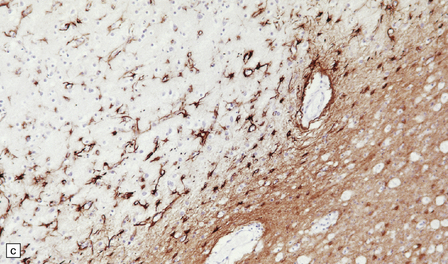

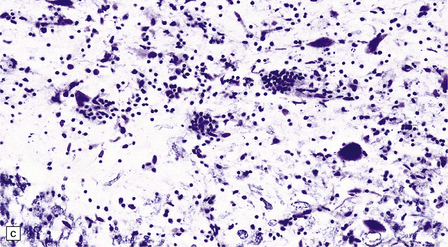

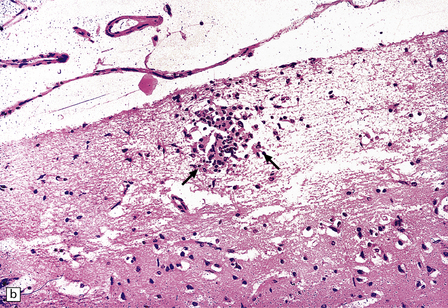

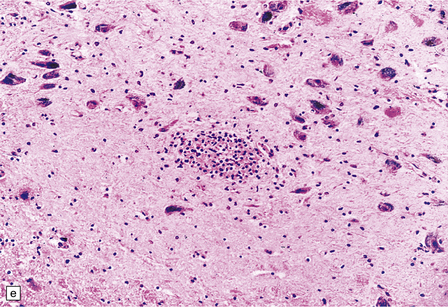

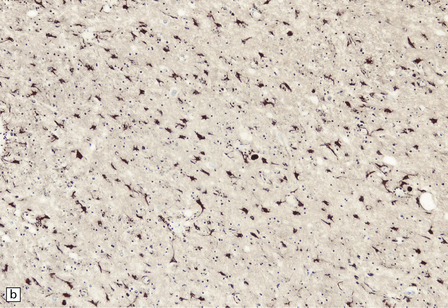

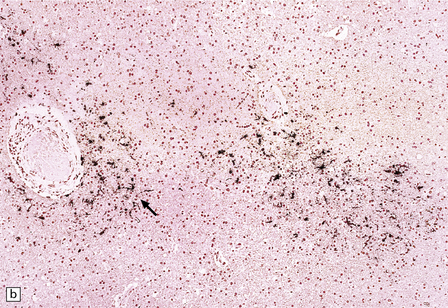

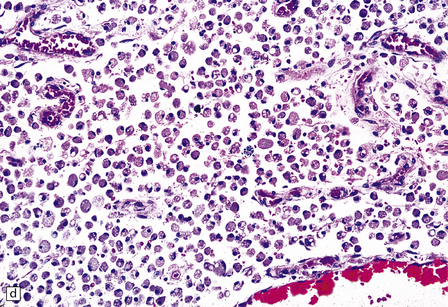

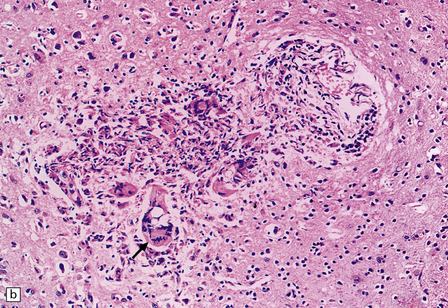

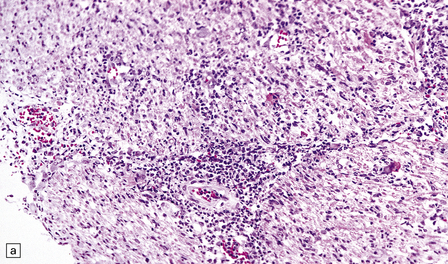

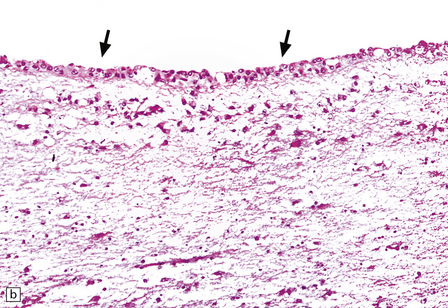

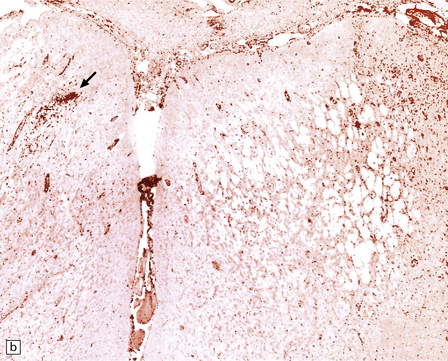

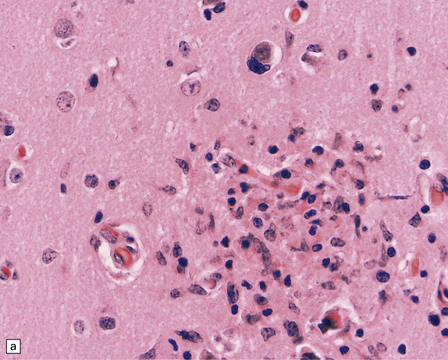

There is a chronic encephalitis, with leptomeningeal, perivascular, and parenchymal infiltration by lymphocytes (predominantly T cells) and microglia (Fig. 13.3).

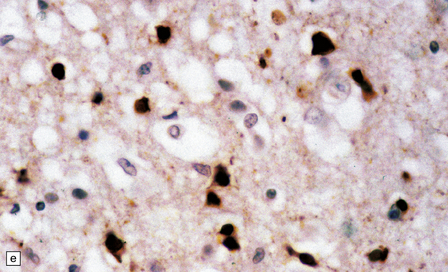

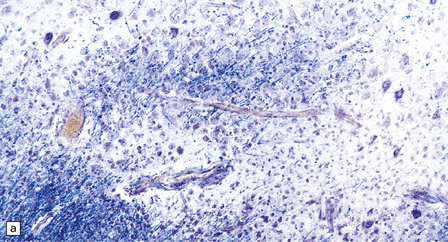

13.3 SSPE.

Leptomeningeal, perivascular, and parenchymal infiltration of the cerebral cortex (a) and white matter (b) by mononuclear inflammatory cells in SSPE. Note the marked reactive gliosis. (c) Dense gliosis of the white matter and deep cerebral cortex in SSPE. Immunostained for glial fibrillary acidic protein. (d) Intranuclear inclusions. These are sparse in SSPE and may be absent, particularly if the disease has run a protracted course. (e) Scattered neurofibrillary tangles (arrows) in the cerebral cortex. These are most numerous in cases with illness of long duration. (f) In a patient with longstanding SSPE, the cerebral cortex includes many neurons and neuritic processes that are immunopositive for phospho-tau.

The distribution and severity of lesions are variable, but the cerebral cortex, white matter, basal ganglia, and thalamus are usually involved. The affected gray matter shows inflammation, gliosis, loss of neurons, occasional neuronophagia, and sparse intranuclear inclusions, which are sharply defined eosinophilic bodies with a surrounding clear space (‘halo’) (Fig. 13.3). In most cases these sparse inclusion bodies can be detected immunohistochemically. Another finding, in some cases of several years’ duration, is the presence of Alzheimer-type neurofibrillary tangles (Fig. 13.3). These are most often found in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, and may be numerous.

The affected white matter is severely gliotic and is characterized by a predominantly perivascular inflammation and a patchy, in some cases extensive, loss of myelinated fibers (Fig. 13.3).

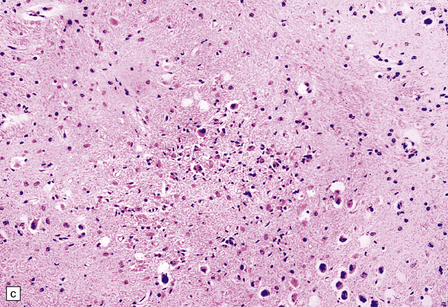

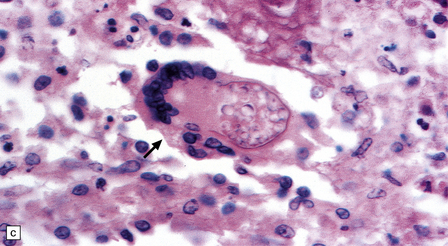

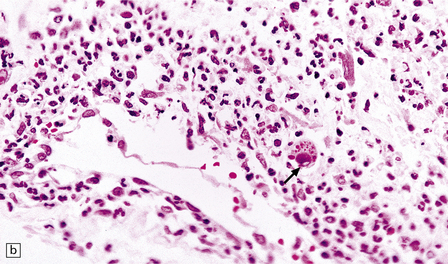

CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS HERPES SIMPLEX ENCEPHALITIS

Very rarely, children who have experienced an otherwise typical attack of acute herpes encephalitis (see Chapter 12) develop focal or multifocal chronic granulomatous encephalitis, sometimes after an intervening symptom-free period of months or years. Histology reveals a patchy cortical and leptomeningeal infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells and scattered, well-circumscribed granulomas that contain epithelioid macrophages and giant cells, with surrounding lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. Foci of necrosis and mineralization may be prominent. In some patients, HSV DNA or antigen are demonstrable by PCR or immunohistochemistry (Fig. 13.4).

PROGRESSIVE MULTIFOCAL LEUKOENCEPHALOPATHY (PML)

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

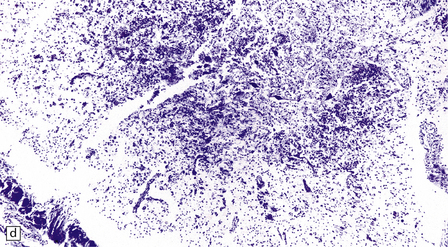

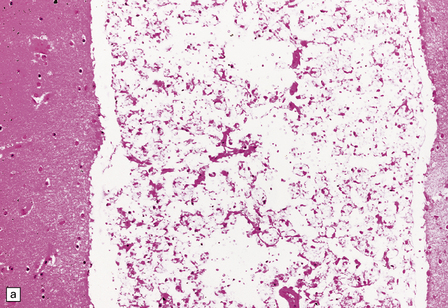

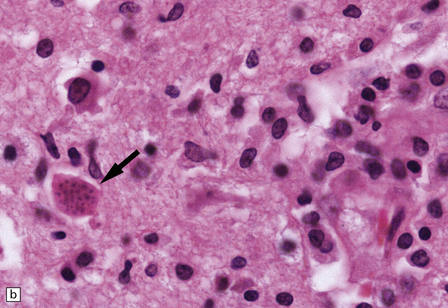

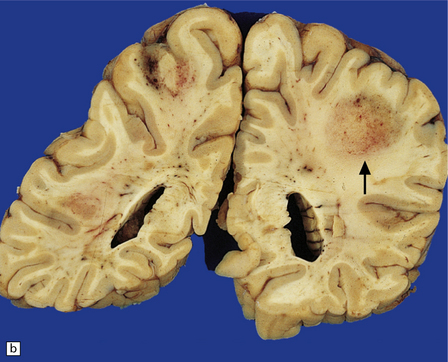

The cut surface of the fixed brain affected by PML appears asymmetrically pitted by small foci of gray discoloration mixed with larger confluent areas of abnormal parenchyma, which may be centrally necrotic (Fig. 13.5). The lesions tend to be most numerous in the cerebral white matter, but also involve the cerebral cortex and deep gray matter (Fig. 13.5). The cerebellum (Fig. 13.5), brain stem, and much less commonly the spinal cord, may also be involved.

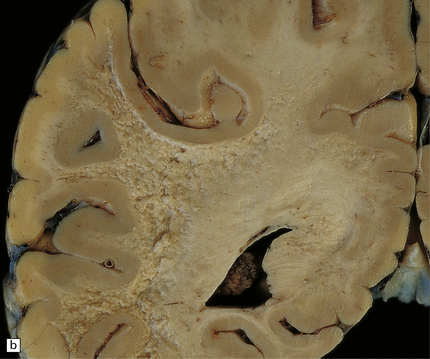

13.5 PML.

(a) Numerous small and larger confluent foci of gray discoloration in the cerebral cortex and white matter. Some of the foci are partly cavitated. (b) In this case there is granularity and focal cavitation of the white matter. (c) Extensive loss of myelin staining in the basal ganglia and hypothalamus. (d) Foci of demyelination in the white matter of the cerebellum.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

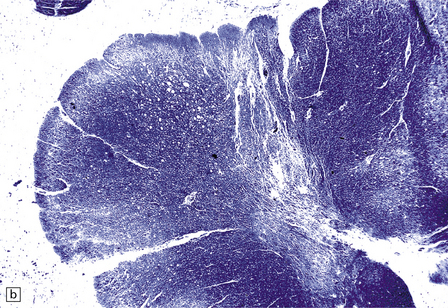

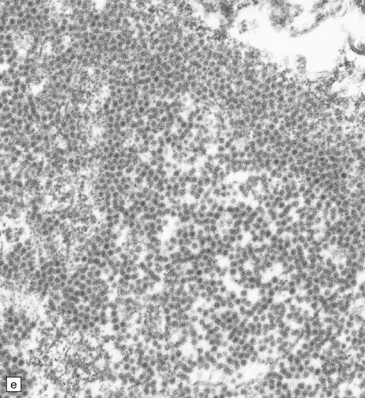

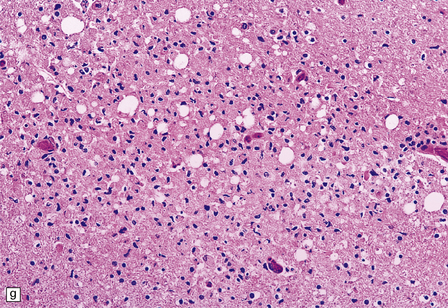

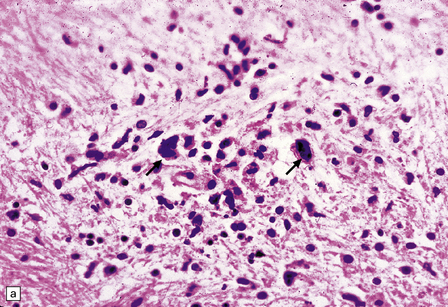

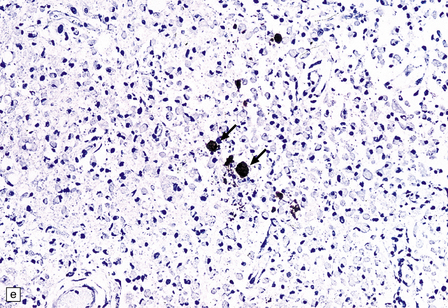

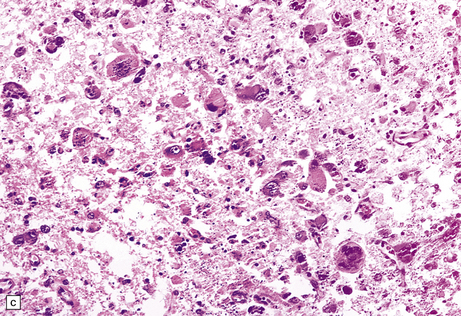

There are multiple foci of demyelination (Fig. 13.6). Some are small and rounded, others confluent, irregular, and occasionally with central necrosis. These lesions contain moderate numbers of foamy macrophages (Fig. 13.6), but only scanty perivascular lymphocytes. Lymphocytic infiltrates may be commoner in PML associated with AIDS and may confer a slightly better prognosis.

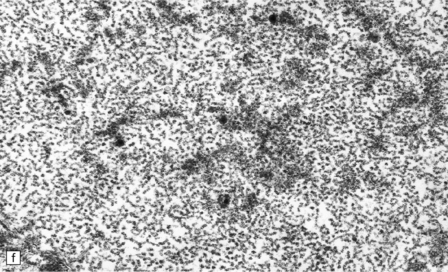

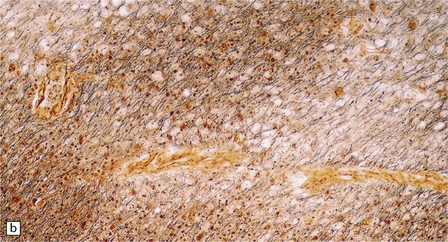

13.6 Histology of PML.

(a) Section stained for myelin with solochrome cyanin. (b) Adjacent section stained for axons. Axons traverse the foci of demyelination. The scattered cells with very large nuclei, seen best in (a), are atypical astrocytes. (c) Foamy macrophages, bizarre astrocytes, and very sparse lymphocytes in a region of demyelination. (d) Oligodendrocytes at the edge of a focus of demyelination have enlarged nuclei containing amphophilic viral inclusions (arrows). Note the large atypical astrocyte (arrowhead). (e) Intranuclear polyomavirus particles in PML. (f) Many of the enlarged nuclei within oligodendrocytes near the edge of a focus of demyelination appear immunopositive when labeled with antibody to SV40. Note too the very scanty lymphocytic cuffing of small blood vessels.

A striking feature, particularly in older lesions, is the presence of very large astrocytes with bizarre, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 13.6). These cells resemble the individual astrocytes that can be seen in glioblastomas. Typical reactive astrocytes are also present.

Mitoses are rare. Those that do occur may appear atypical. However, despite the nuclear pleomorphism, the lesions are easily distinguishable from a neoplasm by their relatively low cellularity and the presence of viral inclusions, which are seen towards the periphery of the foci of demyelination in the enlarged nuclei of oligodendrocytes. The homogeneous amphophilic inclusions (Fig. 13.6) largely fill the nuclei and consist of closely packed polyomavirus particles, which are readily identifiable on electron microscopy (Fig. 13.6). The virus can be demonstrated immunohistochemically (e.g. with SV40 antibody, which also labels JC virus), and viral nucleic acids can be detected and specifically identified by in situ hybridization.

Very rarely, astrocytic neoplasms have been reported in PML.

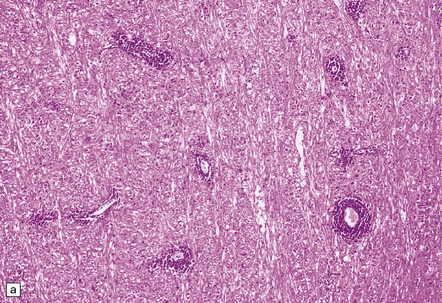

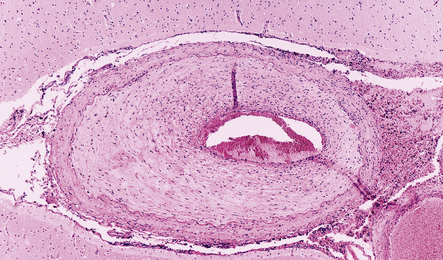

HUMAN T CELL LEUKEMIA/LYMPHOTROPIC VIRUS-1 (HTLV-1)-ASSOCIATED MYELOPATHY (HAM) (TROPICAL SPASTIC PARAPARESIS)

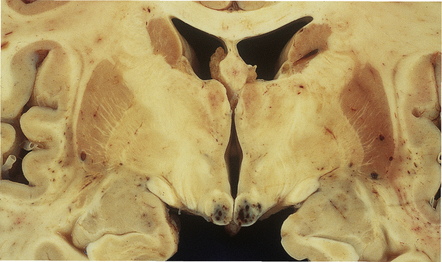

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

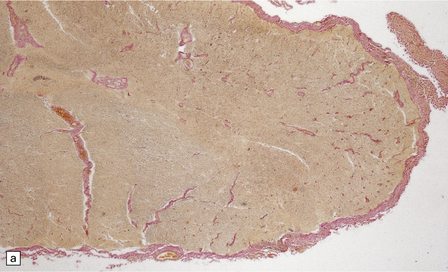

In longstanding cases of HAM, there may be meningeal thickening (Fig. 13.7) and atrophy of the spinal cord, particularly in the lower thoracic region. Lateral funicular degeneration may also be visible.

13.7 HAM.

(a) Collagenous thickening of the spinal leptomeninges and the walls of parenchymal blood vessels. (b) Higher magnification reveals thickened leptomeninges and patchy infiltration by lymphocytes in the dorsal root entry zone. (c) Perivascular and parenchymal infiltrates of lymphocytes in the spinal gray matter in HAM. (d) Degeneration of myelinated fibers in the anterior and lateral funiculi of the spinal cord with relative preservation of anterior horn cells.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

An infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages is seen in the leptomeninges and parenchyma of the spinal cord (Fig. 13.7), and is most marked in the lower thoracic region. Hyaline thickening of small blood vessels is a prominent feature. Intramyelinic vacuolation and demyelination may be evident early in the course of disease, but soon progress to symmetric degeneration and gliosis involving the long tracts in the spinal cord (Fig. 13.7). The degeneration tends to be most severe in the lateral columns. The anterior and less commonly the posterior columns may also be involved. The neurons are relatively well preserved (Fig. 13.7). Sparse viral nucleic acids may be detectable within the spinal cord by in situ hybridization or by polymerase chain reaction. Adventitial fibrosis and scanty perivascular inflammation have been observed in the cerebral white matter and less commonly in the cerebellum and brain stem.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV) INFECTION

Direct infection of the CNS by HIV.

Direct infection of the CNS by HIV.

HIV-related immunosuppression, leading to opportunistic infections (OIs) and neoplasms, especially primary CNS lymphoma.

HIV-related immunosuppression, leading to opportunistic infections (OIs) and neoplasms, especially primary CNS lymphoma.

Systemic factors and miscellaneous (non-specific) conditions related to cachexia, metabolic derangement, hypoxia, and other diverse abnormalities that can result from chronic HIV infection treatment.

Systemic factors and miscellaneous (non-specific) conditions related to cachexia, metabolic derangement, hypoxia, and other diverse abnormalities that can result from chronic HIV infection treatment.

DIRECT HIV INFECTION OF THE CNS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

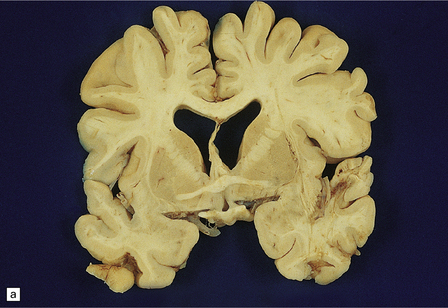

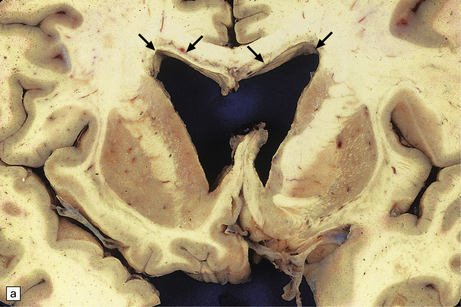

The brain may appear normal or show diffuse atrophy with modest ventriculomegaly (Fig. 13.10) and ill-defined gray discoloration of the centrum semiovale.

13.10 Macroscopic appearance of brain in AIDS dementia/subacute encephalitis of AIDS.

(a) Brain slice from a 39-year-old man with multiple complications of HIV infection including widespread microglial nodule encephalitis and vacuolar myelopathy. Note the mild diffuse cortical atrophy and ventricular enlargement with blunting of the angles of the lateral ventricles. (b) Brain slice from another patient, in a coronal plane similar to that in (a), showing slightly more prominent atrophy of the deep white matter, and blunting of the angles of the lateral ventricles. Cavum septum pellucidum was an incidental finding.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

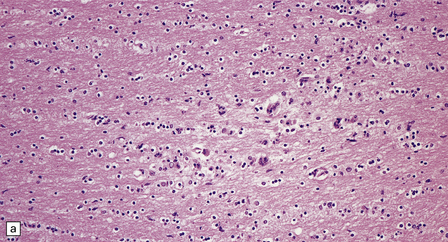

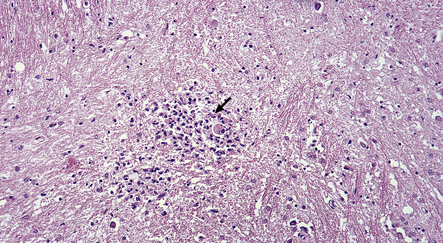

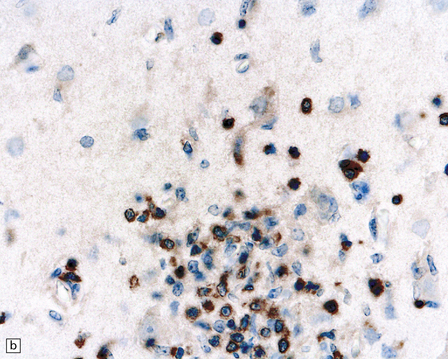

Widespread low-grade inflammation, with microglial nodules and perivascular lymphocyte cuffing (Fig. 13.11). MGNE (microglial nodule encephalitis) is however not specific for direct infection with HIV and is also a feature of many OIs, including CMV, toxoplasmosis, and certain fungal infections.

Widespread low-grade inflammation, with microglial nodules and perivascular lymphocyte cuffing (Fig. 13.11). MGNE (microglial nodule encephalitis) is however not specific for direct infection with HIV and is also a feature of many OIs, including CMV, toxoplasmosis, and certain fungal infections.

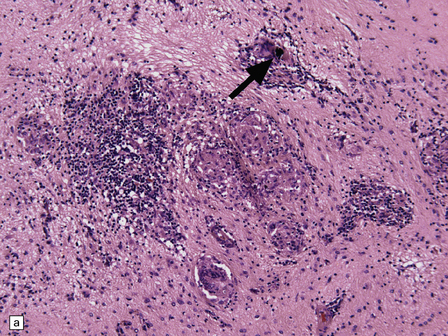

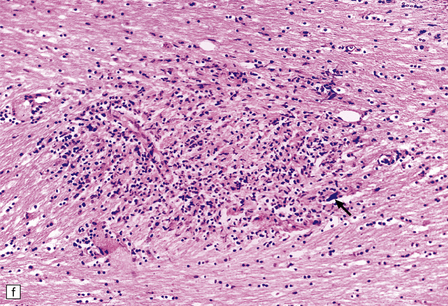

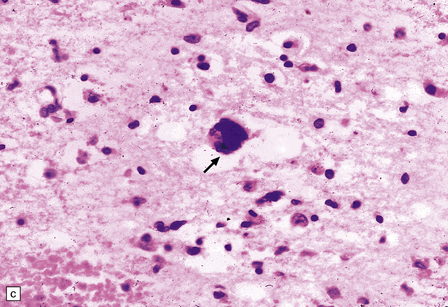

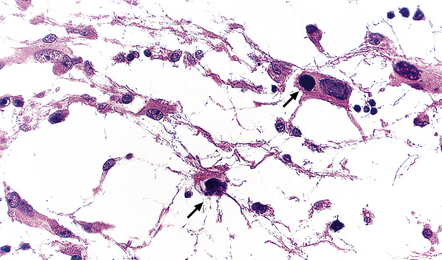

13.11 Microglial nodule encephalitis.

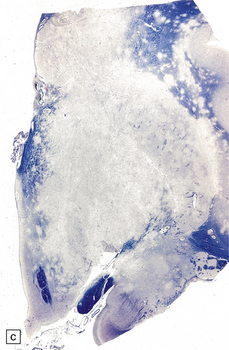

This is a characteristic finding in the brains of patients who die with HIV infection, and may be due to an identified agent (e.g. HIV, CMV, toxoplasmosis), though occasionally no causal micro-organism is found. Inflammatory foci contain varying numbers of microglia, some lymphocytes and (often) surrounding astrocytes. (a) Small microglial nodule (MGN, arrow) within brain parenchyma. (b) Subpial microglial nodule (arrows), one of many identified in a patient who had severe AIDS dementia and harbored a ‘neurotropic’ strain of HIV. Note slightly more prominent cytoplasm of component cells in the MGN. This is a characteristic finding in the brains of patients who die with HIV infection, and may be due to an identified agent (e.g. HIV, CMV, toxoplasmosis), though occasionally no causal micro-organism is found. Inflammatory foci contain varying numbers of microglia, some lymphocytes and (often) surrounding astrocytes. (c) Poorly defined region of microglial activation. (d–f) Compact collections of microglia, including one in the substantia nigra (e). The presence of multinucleated cells in (d) (arrows) and (f) is strong evidence for HIV infection of the brain. (g) Loosely defined collection of microglia, associated with vacuolation of the surrounding neuropil.

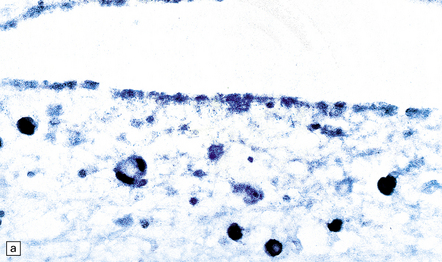

Leukoencephalopathy with patchy demyelination and variable gliosis of white matter, often with associated gliosis of deep central gray matter (Fig. 13.12).

Leukoencephalopathy with patchy demyelination and variable gliosis of white matter, often with associated gliosis of deep central gray matter (Fig. 13.12).

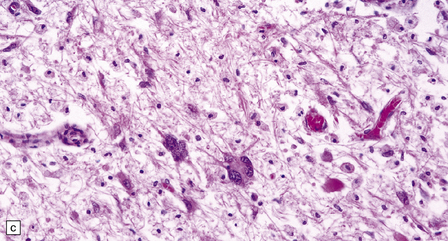

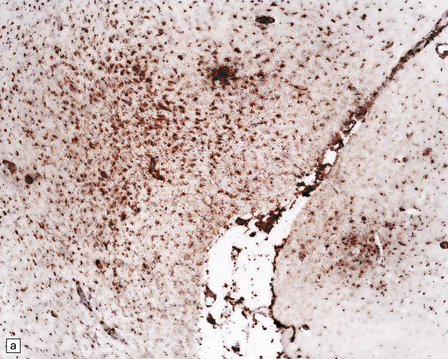

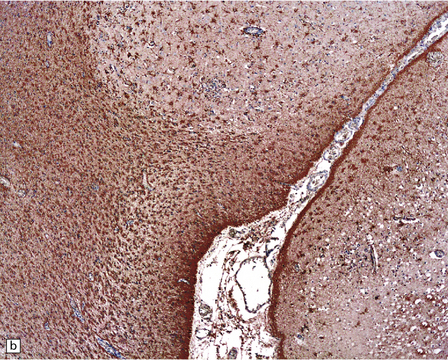

13.12 HIV leukoencephalopathy.

This is characterized by pallor of myelin staining, and mild to moderate white matter astrocytic gliosis as illustrated in (a). Arrows indicate the junction between cortex, at right, and subcortical white matter, at left. Astrocytic gliosis is also often noted in the deep central gray matter (b).

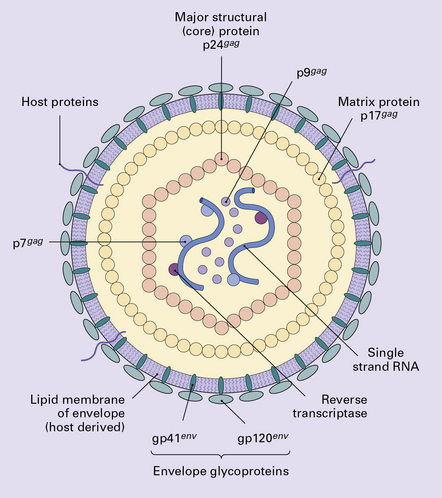

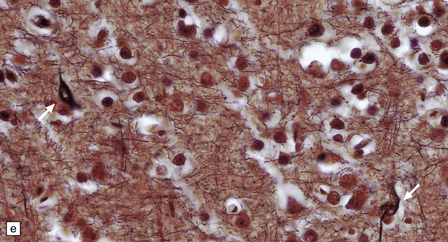

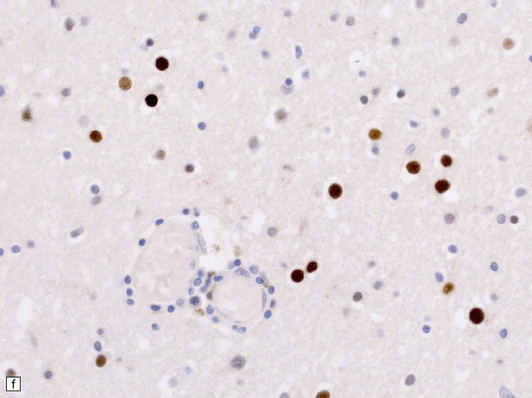

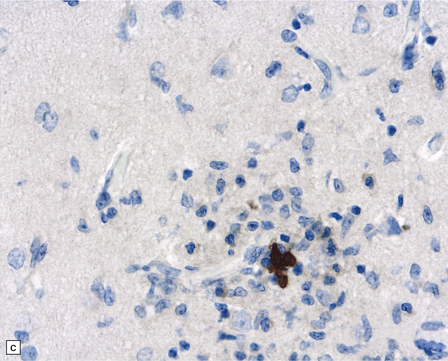

Multinucleated cells, usually pericapillary, with scant cytoplasm (morulae) or abundant cytoplasm (true giant cells) (Fig. 13.13), in which HIV antigen can be demonstrated with antibody to gp41 or p24 (Fig. 13.14). Even without immunohistochemistry, the multinucleated cells are sufficiently characteristic to allow a diagnosis of HIV encephalitis provided that other causes of granulomatous inflammation with giant cell formation are ruled out. HIV antigen may also be demonstrable in microglial cells without characteristic ‘giant cell’ morphology (Fig. 13.15).

Multinucleated cells, usually pericapillary, with scant cytoplasm (morulae) or abundant cytoplasm (true giant cells) (Fig. 13.13), in which HIV antigen can be demonstrated with antibody to gp41 or p24 (Fig. 13.14). Even without immunohistochemistry, the multinucleated cells are sufficiently characteristic to allow a diagnosis of HIV encephalitis provided that other causes of granulomatous inflammation with giant cell formation are ruled out. HIV antigen may also be demonstrable in microglial cells without characteristic ‘giant cell’ morphology (Fig. 13.15).

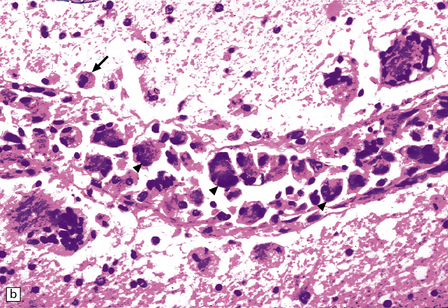

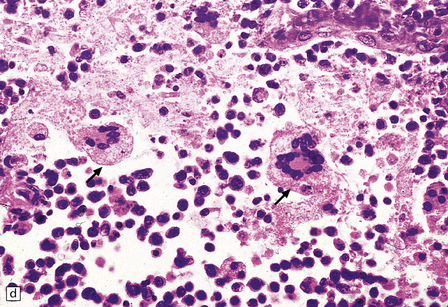

13.13 Multinucleated cells, characteristic of HIV infection of brain (HIV-GC).

Parenchymal HIV-GC are indicated by arrows in each frame. The cells may be associated with MGNs (a) or have a morular appearance (c). The cells contain variable amounts of eosinophilic or foamy cytoplasm, and tend to aggregate around blood vessels (especially capillaries), as in (b): the arrowheads indicate several intraluminal HIV-GC. (d) HIV-GC adjacent to a CNS lymphoma.

13.14 HIV brain infection.

(a) Immunohistochemical demonstration of HIV p24 antigen in scattered microglia/macrophages and multicleated cells. (b) and (c) HIV-immunoreactive cells with more typical microglial morphology. In (b), they are prominent in a perivascular distribution (arrow).

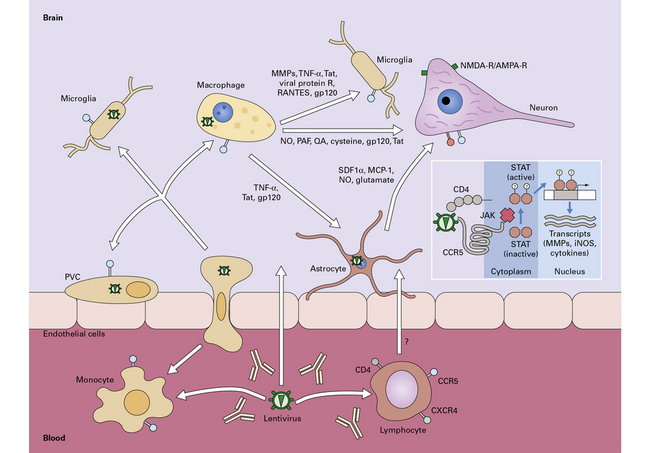

13.15 Potential mechanisms by which HIV enters the nervous system and causes neuronal injury.

Macrophages and lymphocytes, expressing CD4 and CCR5 or CXCR4 are infected in the periphery and subsequently cross the blood–brain (or blood–nerve) barrier. Once in the nervous system, other cells of macrophage/microglial lineage are infected or are induced to release potential neurotoxins, including cytokines, chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), quinolinic acid, glutamate, and nitric oxide. To a limited extent, astrocytes are also infected; this may influence neuronal survival. Inset shows a potential signaling pathway in microglia/macrophages, involving HIV gp120 induction of MMP expression through CCR5 and subsequent activation and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor, STAT-1. (Diagram reproduced by courtesy of Dr Chris Power, University of Calgary, Canada, and the Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences.)

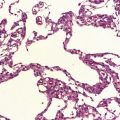

Vacuolar Myelopathy

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES: The vacuolar myelopathy resembles subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord (Fig. 13.16) (see Chapter 21). There is vacuolation of the spinal white matter in the posterior columns and lateral corticospinal tracts, most pronounced in the thoracic segments. Breakdown of myelin, and later axons, is accompanied by an accumulation of macrophages containing debris.

Necrotizing leukoencephalopathy

Rarely, HIV infection of the CNS produces a severe necrotizing leukoencephalopathy (Fig. 13.17). A severe leukoencephalopathy, characterized by intense perivascular macrophage and lymphocyte infiltration and high levels of HIV in the CNS, has been described in rare individuals receiving cART. This may result, in part, from an exaggerated response of the reconstituted immune system to HIV antigens.

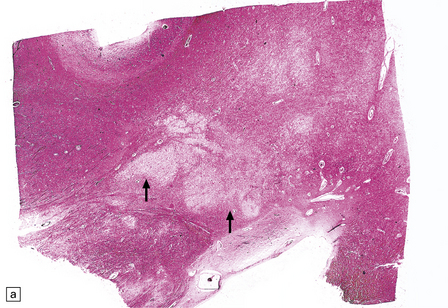

13.17 Necrotizing leukoencephalopathy associated with HIV infection.

(a) Patchy necrosis (arrows) of the internal capsule. (b) Dystrophic calcification and reactive (gemistocytic) astrocytes in a focus of white matter necrosis. (c–e) All sections are from the brain of a patient who had severe HIV encephalitis with numerous HIV-immunopositive cells throughout the brain. In (c) there is prominent vacuolation of the white matter. Other regions contained large collections of foamy macrophages (d,e), among which were HIV-immunoreactive cells: arrows in (e).

HIV-ASSOCIATED IMMUNOSUPPRESSION AND NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

Deficient cell-mediated immunity due to HIV infection may lead to:

Bacterial infection, especially by atypical, e.g. acid-fast bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI).

Bacterial infection, especially by atypical, e.g. acid-fast bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI).

Fungal infections of the CNS in AIDS

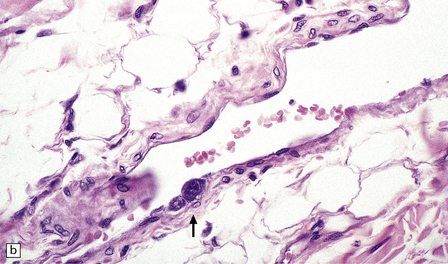

Cryptococcus neoformans: In most series, C. neoformans is the commonest fungal opportunistic infection of the CNS in AIDS, affecting up to 5–10% of patients. It presents as a meningitis, which is often low grade. The brain usually has a glistening sheen on external examination and a cribriform appearance, especially affecting gray matter structures (Fig. 13.19), on sectioning as a result of fungal proliferation in the perivascular (Virchow–Robin) spaces. Rarely, there is a necrotic abscess. The inflammatory response may be virtually non-existent, mild or, rarely, of severe granulomatous type (Fig. 13.20).

13.19 Section through the midbrain of an AIDS patient with severe cryptococcal meningoencephalitis.

Distension of perivascular spaces by proliferating fungi gives affected parts of the brain (in this case, the substantia nigra) a cribriform appearance. Because of its denser microvasculature, the gray matter is usually more severely affected than the white matter.

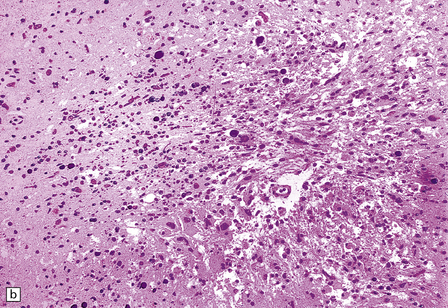

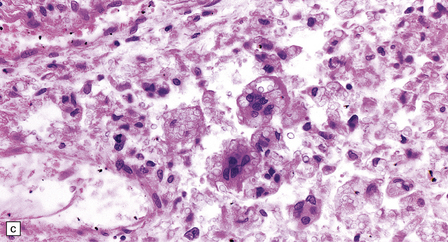

13.20 Variable inflammatory response to cryptococcal infection in AIDS.

(a) This shows fungal yeasts expanding the subarachnoid space surrounding the cerebellum, with virtually no associated inflammation. (b) Severe granulomatous inflammation in the subarachnoid space, with necrosis of the underlying cortex and white matter. Necrosis is most severe at the depths of sulci (arrows). (c) Magnified view of the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate revealing cryptococcal yeast forms in the cytoplasm of multinucleated giant cells.

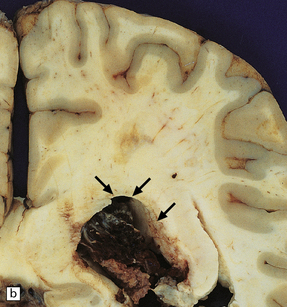

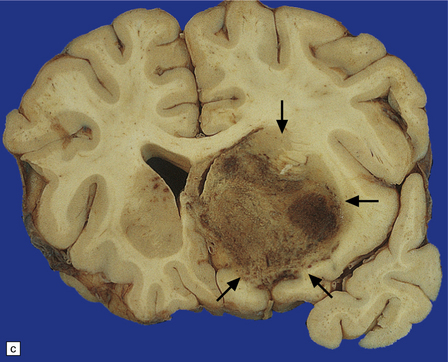

Aspergillus fumigatus: A. fumigatus infection usually causes abscesses that present as markedly hemorrhagic space-occupying lesions. CNS involvement is usually associated with widely disseminated infection and the brain contains multiple necrotic, often hemorrhagic, lesions (Fig. 13.21). Histology reveals angioinvasive fungal hyphae, vascular thrombosis and infarction, and variable inflammation. Mycotic aneurysms are common (see Chapter 10).

13.21 Aspergillus infection in a patient with AIDS.

(a) Multiple foci of hemorrhagic necrosis are typical of CNS aspergillosis. Aspergillus is known to be highly angioinvasive; arrow indicates thrombosed anterior cerebral arteries. (b) Two extensively necrotic ‘aspergillomas’ (arrows) in the brain of a patient with AIDS.

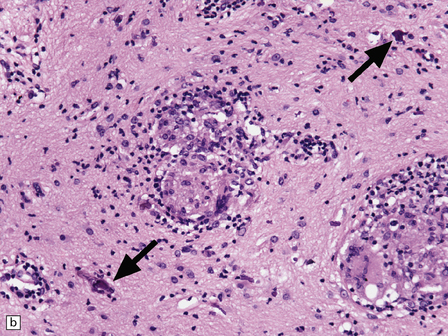

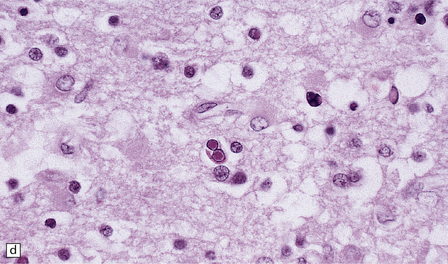

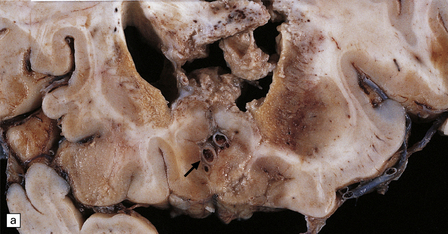

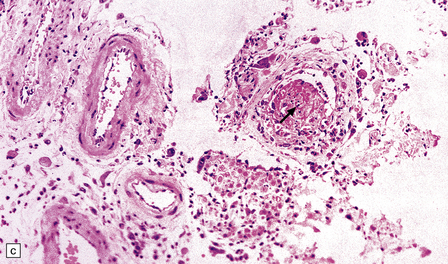

Coccidioides immitis: This is an important AIDS-related infection in areas where the fungus is common in dusty soil (e.g. south-western United States, especially the San Joaquin Valley of central California). Macroscopic examination of the brain reveals meningitis and abscesses, usually microabscesses rather than large mass lesions (Fig. 13.22). Histology reveals large spherules with enclosed endospores, often engulfed by multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 13.22) and associated with acute or chronic granulomatous inflammation. Fibrinoid necrosis of small vessels and endarteritis obliterans are common.

13.22 Coccidioidomycosis, a common OI in patients with AIDS in the south-western USA.

(a) Granulomatous meningoencephalitis; arrow indicates a multinucleated giant cell surrounding encysted fungal organisms. (b) A microglial nodule-like structure, with several multinucleated giant cells; arrow indicates a multinucleated cell with vacuolated cytoplasm containing fungi. (c) The fungal endospores are encapsulated within spherules, some of which are engulfed by foreign body-type giant cells (arrow). (Courtesy of Dr Paul S Mischel.)

Other fungal infections: Many other fungal infections have been described in the CNS of patients with AIDS, including histoplasmosis, candidiasis, and mucormycosis (see Chapter 17).

Viral encephalitides and myelitides in AIDS

Low-grade microglial nodule encephalitis (MGNE). Cytomegalic cells occur within microglial nodules (Fig. 13.23) or without any associated inflammation.

Low-grade microglial nodule encephalitis (MGNE). Cytomegalic cells occur within microglial nodules (Fig. 13.23) or without any associated inflammation.

13.23 CMV-related microglial nodule encephalitis (MGNE) involving the medulla of a patient with AIDS.

A cytomegalic cell (arrow) is present within the microglial nodule.

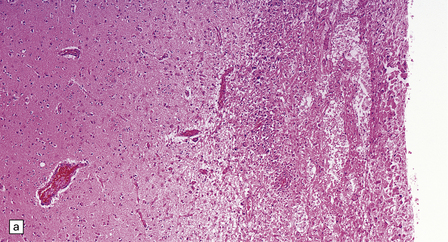

Severe necrotizing encephalitis with large regions of cystic encephalomalacia (Fig. 13.24) resembling infarcts.

Severe necrotizing encephalitis with large regions of cystic encephalomalacia (Fig. 13.24) resembling infarcts.

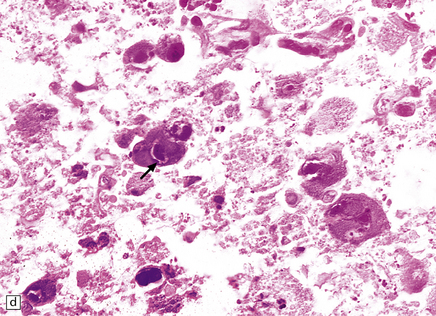

13.24 Severe necrotizing CMV encephalitis in patients with AIDS.

(a) Large regions of cystic encephalomalacia resembling infarcts are seen within the cerebellar white matter. (b) Patchy, extensive necrosis in the basis pontis of a patient with AIDS and CMV encephalitis. (c,d) Cytomegalic cells with characteristic nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions (arrow, d) among extensive foci of necrosis.

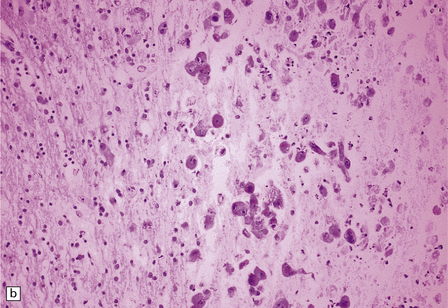

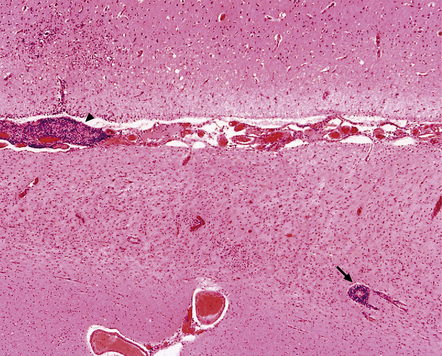

Ventriculoencephalitis (Figs 13.25, 13.26) visible macroscopically or on imaging studies as ‘sugar icing’-like material lining the ventricular surfaces, with hemorrhagic necrosis of adjacent brain parenchyma.

Ventriculoencephalitis (Figs 13.25, 13.26) visible macroscopically or on imaging studies as ‘sugar icing’-like material lining the ventricular surfaces, with hemorrhagic necrosis of adjacent brain parenchyma.

13.25 Necrotizing CMV ventriculoencephalitis.

(a) There is congestion and focal hemorrhagic necrosis of peri-ventricular tissue adjacent to the ependymal lining (arrows). (b) A more posterior coronal slice through the same brain shows similar features (arrows), as well as acute hemorrhage into the choroid plexus, epithelial cells of which are frequently infected by CMV.

13.26 Necrotizing CMV ventriculoencephalitis and associated CMV encephalitis.

(a) The ventricular cavity (barely visible at right of figure) is surrounded by a thick layer of inflamed, partly necrotic ependymal and subependymal tissue. (b) Within this periventricular tissue, cytomegalic cells are prominent. (c) Elsewhere within the brain, isolated cytomegalic cells (e.g. arrow) are seen, often with minimal surrounding inflammation.

Meningoradiculitis and myelitis (Fig. 13.27) with a clinical presentation simulating Guillain–Barré syndrome. This is often due to CMV-associated vasculopathy, with microvascular thrombi in and around the nerve roots.

Meningoradiculitis and myelitis (Fig. 13.27) with a clinical presentation simulating Guillain–Barré syndrome. This is often due to CMV-associated vasculopathy, with microvascular thrombi in and around the nerve roots.

13.27 CMV radiculitis in an AIDS patient who presented with an acute polyradiculitis, resembling Guillain–Barré syndrome.

(a) The nerve roots show a moderately severe chronic inflammatory infiltrate within which (b) are typical CMV inclusions (arrow). (c) Foci of necrosis are associated with microthrombi (arrow) in small meningeal arteries harboring CMV in their walls.

Rarely, widespread infection of microvascular endothelial cells (Fig. 13.28) that sometimes also involves the peripheral nerve and skeletal muscle, including epineurial/epimysial tissues.

Rarely, widespread infection of microvascular endothelial cells (Fig. 13.28) that sometimes also involves the peripheral nerve and skeletal muscle, including epineurial/epimysial tissues.

There is evidence of occasional coinfection of single cells by HIV and CMV.

Leukoencephalopathy and leukoencephalitis with sharply demarcated necrotizing lesions.

Leukoencephalopathy and leukoencephalitis with sharply demarcated necrotizing lesions.

Encephalitis involving the visual system.

Encephalitis involving the visual system.

Myeloradiculitis (Fig. 13.29).

Myeloradiculitis (Fig. 13.29).

13.29 VZV infection of nerve roots and brain.

(a) Radiculitis. Immunostained VZV-infected cells (arrows) in a nerve root. (Courtesy of Professor Françoise Gray, Hôpital Raymond Poincare, Paris, France.) (b) Ventriculitis. Arrows indicate ventricular lining that was heavily infected with VZV. Small ependymal intranuclear inclusions are barely visible at this magnification. Subependymal region shows only slight rarefaction, and minimal inflammation (contrast the appearance of CMV ependymitis, Fig. 13.26).

Other herpesviruses infections: Herpes simplex encephalitis occurs rarely in patients with AIDS, while Epstein–Barr virus infection is associated with primary CNS lymphoma in AIDS patients (see below and Chapter 42). The role of human herpesvirus-6 in the pathogenesis of AIDS-related neurologic syndromes has not yet been defined. Another herpesvirus, designated human herpesvirus-8 (HHV8) or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), has a role in the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma and primary effusion (body cavity-based) lymphomas, but not directly in the development of neurologic disease.

The neuropathology of PML is described on p.325.

Other viral infections of the CNS that have rarely been reported in patients with AIDS include adenovirus encephalitis (Fig. 13.30) and measles inclusion body encephalitis (see p.323).

13.30 Adenovirus encephalitis.

Intranuclear adenovirus inclusions (arrows) in adenovirus ventriculo-encephalitis in a child with AIDS.

Diagnosis of the specific viral infection in the histological material can be achieved by:

Immunohistochemistry for viral antigen(s) (Figs 13.13, 13.29).

Immunohistochemistry for viral antigen(s) (Figs 13.13, 13.29).

In situ hybridization using probes specific for viral DNA and RNA (Fig. 13.31).

In situ hybridization using probes specific for viral DNA and RNA (Fig. 13.31).

13.31 Detection of CMV by in situ hybridization.

Note subependymal (a) and numerous parenchymal (b) cells that are positive for CMV DNA, in the brain of a patient with AIDS.

Parasitic infections/infestations of the CNS in AIDS

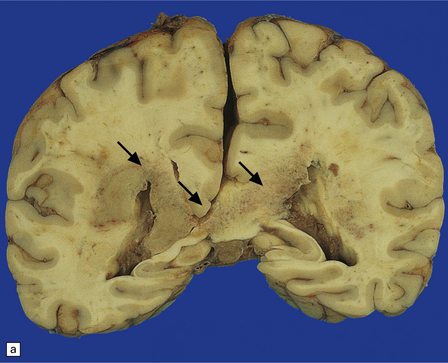

The most important parasitic infection of the CNS in AIDS is toxoplasmosis. This usually produces large necrotic brain abscesses, which may be multiple (Fig. 13.32). The neuropathology of parasitic infections is discussed in detail in Chapter 18.

13.32 CNS toxoplasmosis.

(a) Coronal slice from an affected AIDS patient. Arrows indicate hemorrhagic linear lesion representing a biopsy needle track (biopsy had been carried out several days prior to patient’s death). Arrowhead indicates a large necrotic focus in the right caudate nucleus. (b) Intracellular tachyzoites (arrow) adjacent to a necrotic focus in an AIDS patient with toxoplasmosis. The surrounding cells consist largely of macrophages and microglia.

Bacterial infections of the CNS in AIDS

The commonest bacterial infections in AIDS are due to acid-fast bacilli, including:

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, which is found in large numbers in the cytoplasm of infected macrophages within the CNS, often in a perivascular distribution. This usually produces only mild parenchymal injury, but rarely causes focal necrosis.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, which is found in large numbers in the cytoplasm of infected macrophages within the CNS, often in a perivascular distribution. This usually produces only mild parenchymal injury, but rarely causes focal necrosis.

The incidence of neurosyphilis is increased in patients with AIDS.

Neoplasms of the CNS in AIDS

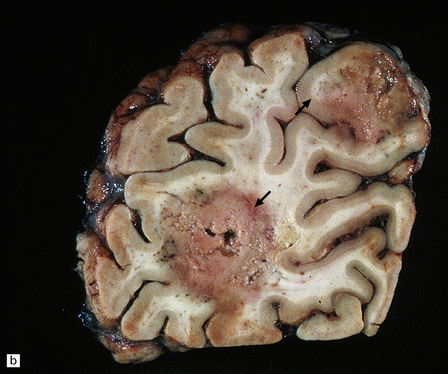

PCNSL in AIDS is usually high-grade, non-Hodgkin’s, B cell lymphoma, and associated with Epstein–Barr virus infection. The prognosis is dismal despite aggressive radiotherapy; however, improved survival is now observed in some patients following cART. Neuropathologic examination reveals unifocal or multifocal lesions, which may mimic a glioblastoma macroscopically (Figs 13.33, 13.34) and are often necrotic.

13.33 PCNSL in AIDS.

(a) PCNSL mimicking a ‘butterfly’ glioblastoma, with tumor (arrows) extending across the corpus callosum. (b) Multifocal PCNSL. The arrow indicates a focus on the right. A smaller focus is seen in the left parietal region. (c) Hemorrhage and necrosis in an AIDS-related PCNSL (arrows) involving the right basal ganglia, with surrounding edema.

HIV-ASSOCIATED SYSTEMIC FACTORS AND MISCELLANEOUS CONDITIONS CAUSING NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

Cerebrovascular disease in AIDS

Metabolic and nutritional abnormalities in AIDS

Hypoxic encephalopathy may occur, as would be expected in patients who often develop respiratory failure due to overwhelming pneumonia (e.g. caused by Pneumocystis carinii or CMV). Rarely, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (secondary to thiamine deficiency) is observed (Fig. 13.36). Alzheimer’s type II astrocytosis is usually associated with liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy (see Chapter 22), but is often observed in patients with AIDS in the absence of liver failure.

13.36 Typical mammillary body lesions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy in an AIDS patient.

These developed shortly after starting zidovudine therapy.

Central pontine myelinolysis is seen occasionally in association with AIDS and not always after rapid correction of hyponatremia (see Chapter 22). It should be distinguished from multifocal necrotizing leukoencephalopathy, which may also complicate AIDS (see Chapter 22).

RASMUSSEN’S ENCEPHALITIS

This is a rare syndrome occurring in children (see also Epilepsy in Childhood, in Chapter 7), characterized by:

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The affected cerebral hemisphere shows variable focal atrophy and, in some cases, cavitation.

Microscopically, the cortex and (less prominently) white matter are consistently affected by multifocal patchy inflammation, astrocytosis, cortical neuron loss (often in a laminar pattern involving layers 5 and 6) and spongy cavitation, these changes eventually leading to atrophy (Figs 13.37–13.40). The inflammation is characterized by:

13.37 Rasmussen encephalitis.

Corticectomy specimen. Cortex in lower half of micrograph shows severe neuronal loss and astrocytic gliosis (contrast with relatively preserved cortex in upper half of micrograph). A low grade multifocal lymphocytic infiltrate is present within the brain. Perivascular lymphocytic cuffing is present within the severely affected cortex (arrow), while some small vessels in the meninges are effaced by lymphoid cells (arrowhead). (Courtesy of Dr Hajime Miyata.)

13.38 Chronic Rasmussen encephalitis.

(a) Note extensive microcystic cavitation of the affected cortex. (b) Even within this severely affected region of cortex, scattered collections of CD3-immunoreactive T-lymphocytes remain (arrow). (Courtesy of Dr Hajime Miyata.)

13.39 Focal cortical involvement in Rasmussen encephalitis.

CD68- (a) and GFAP-immunostained (b) sections show an abrupt boundary between severely affected (lower part of micrograph) and less prominently involved brain tissue (upper part). Panels are from parallel sections immunostained with the two different antibodies. (Courtesy of Dr Hajime Miyata.)

13.40 Rasmussen encephalitis.

Laminar nature of astrocytic proliferation is accentuated in this GFAP-immunostained section. (Courtesy of Dr Hajime Miyata.)

Microglial activation, with microglia often closely apposed to neurons.

Microglial activation, with microglia often closely apposed to neurons.

Microglial nodules (Fig. 13.39), which may be in close proximity to pyknotic neurons.

Microglial nodules (Fig. 13.39), which may be in close proximity to pyknotic neurons.

Perivascular and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltrates composed mainly of T-cells (Fig. 13.40).

Perivascular and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltrates composed mainly of T-cells (Fig. 13.40).

Focal meningitis with lymphocytic cuffing and even infiltration of meningeal veins (Fig. 13.41).

Focal meningitis with lymphocytic cuffing and even infiltration of meningeal veins (Fig. 13.41).

13.41 Rasmussen encephalitis.

The micrographs are from the same regions of adjacent sections through a cortical resection specimen, and are stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (a), or different primary antibodies (b–f). Note the more abundant T (CD3-positive) (b) than B lymphocytes (CD20-positive) (c). The CD4+ cells and microglia express ICAM3 (d), but the microglia are better highlighted by immunohistochemistry for CD68 (e). Many are closely apposed to neurons (arrow). Labeling for GFAP (f) emphasizes the reactive astrocytosis. (Courtesy of Dr Hajime Miyata.)

REFERENCES

Chronic enteroviral encephalomyelitis

Cunningham, C.K., Bonville, C.A., Ochs, H.D., et al. Enteroviral meningoencephalitis as a complication of X-linked hyper IgM syndrome. J Pediatr.. 1999;134:584–588.

McKinney, R.E., Jr., Katz, S.L., Wilfert, C.M. Chronic enteroviral meningoencephalitis in agammaglobulinemic patients. Rev Infect Dis.. 1987;9:334–356.

Padate, B.P., Keidan, J. Enteroviral meningoencephalitis in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated previously with rituximab. Clin Lab Haematol.. 2006;28:69–71.

Rudge, P., Webster, A.D., Revesz, T., et al. Encephalomyelitis in primary hypogammaglobulinaemia. Brain.. 1996;119(Pt 1):1–15.

Subacute measle encephalitides

Allen, I.V., McQuaid, S., McMahon, J., et al. The significance of measles virus antigen and genome distribution in the CNS in SSPE for mechanisms of viral spread and demyelination. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 1996;55:471–480.

Bancher, C., Leitner, H., Jellinger, K., et al. On the relationship between measles virus and Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Neurobiol Aging.. 1996;17:527–533.

Garg, R.K. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Neurol.. 2008;255:1861–1871.

McQuaid, S., Cosby, S.L. An immunohistochemical study of the distribution of the measles virus receptors, CD46 and SLAM, in normal human tissues and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Lab Invest.. 2002;82:403–409.

Ortega-Aznar, A., Romero-Vidal, F.J., Castellvi, J., et al. Adult-onset subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinico-pathological findings in 2 new cases. Clin Neuropathol.. 2003;22:110–118.

Ozturk, A., Gurses, C., Baykan, B., et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of 36 patients. J Child Neurol.. 2002;17:25–29.

Prashanth, L.K., Taly, A.B., Ravi, V., et al. Adult onset subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinical profile of 39 patients from a tertiary care centre. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 2006;77:630–633.

Rima, B.K., Duprex, W.P. Molecular mechanisms of measles virus persistence. Virus Res.. 2005;111:132–147.

Singer, C., Lang, A.E., Suchowersky, O. Adult-onset subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: case reports and review of the literature. Mov Disord.. 1997;12:342–353.

Souraud, J.B., Faivre, A., Waku-Kouomou, D., et al. Adult fulminant subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: pathological and molecular studies – a case report. Clin Neuropathol.. 2009;28:213–218.

Progressive rubella panencephalitis

Frey, T.K. Neurological aspects of rubella virus infection. Intervirology.. 1997;40:167–175.

Townsend, J.J., Stroop, W.G., Baringer, J.R., et al. Neuropathology of progressive rubella panencephalitis after childhood rubella. Neurology.. 1982;32:185–190.

Wolinsky, J.S., Berg, B.O., Maitalnd, C.H. Progressive rubella panencephalitis. Arch Neurol.. 1976;33:722–723.

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Brew, B.J., Davies, N.W., Cinque, P., et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other forms of JC virus disease. Nat Rev Neurol.. 2010;6:667–679.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K., Tyler, K.L. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon β1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med.. 2005;353:369–374.

Koralnik, I.J. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy revisited: Has the disease outgrown its name? Ann Neurol.. 2006;60:162–173.

Koralnik, I.J., Wuthrich, C., Dang, X., et al. JC virus granule cell neuronopathy: A novel clinical syndrome distinct from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol.. 2005;57:576–580.

Langer-Gould, A., Atlas, S.W., Green, A.J., et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med.. 2005;353:375–381.

Lima, M.A., Bernal-Cano, F., Clifford, D.B., et al. Clinical outcome of long-term survivors of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 2010;81:1288–1291.

Metz, I., Radue, E.W., Oterino, A., et al. Pathology of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in multiple sclerosis with natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl).. 2012;123(2):235–245.

Sabath, B.F., Major, E.O. Traffic of JC virus from sites of initial infection to the brain: the path to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis.. 2002;186(suppl 2):S180–S186.

Tan, C.S., Ellis, L.C., Wuthrich, C., et al. JC virus latency in the brain and extraneural organs of patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol.. 2010;84:9200–9209.

Tan, C.S., Koralnik, I.J. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol.. 2010;9:425–437.

Tavazzi, E., White, M.K., Khalili, K., Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: clinical and molecular aspects. Rev Med Virol. 2011.

White, M.K., Khalili, K. Pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy revisited. J Infect Dis.. 2011;203:578–586.

Wuthrich, C., Cheng, Y.M., Joseph, J.T., et al. Frequent infection of cerebellar granule cell neurons by polyomavirus JC in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2009;68:15–25.

Araujo, A., Hall, W.W. Human T-lymphotropic virus type II and neurological disease. Ann Neurol.. 2004;56:10–19.

Aye, M.M., Matsuoka, E., Moritoyo, T., et al. Histopathological analysis of four autopsy cases of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis: inflammatory changes occur simultaneously in the entire central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol (Berl).. 2000;100:245–252.

Castro-Costa, C.M., Dom, R., Carton, H., et al. Neuropathology of two Brazilian autopsied cases of tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-I associated myelopathy (TSP/HAM) of long evolution. Arq Neuropsiquiatr.. 2002;60:531–536.

Grant, C., Barmak, K., Alefantis, T., et al. Human T cell leukemia virus type I and neurologic disease: events in bone marrow, peripheral blood, and central nervous system during normal immune surveillance and neuroinflammation. J Cell Physiol.. 2002;190:133–159.

Izumo, S., Neuropathology of HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP). Neuropathology. 2010.

Nakamura, T. Immunopathogenesis of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Ann Med.. 2000;32:600–607.

Osame, M. Pathological mechanisms of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP). J Neurovirol.. 2002;8:359–364.

Takenouchi, N., Yao, K., Jacobson, S. Immunopathogenesis of HTLV-I associated neurologic disease: molecular, histopathologic, and immunologic approaches. Front Biosci.. 2004;9:2527–2539.

Aboulafia, D.M., Taylor, L. Vacuolar myelopathy and vacuolar cerebellar leukoencephalopathy: A late complication of AIDS after highly active antiretroviral therapy-induced immune reconstitution. AIDS Patient Care STDS.. 2002;16:579–584.

Anthony, I.C., Bell, J.E. The neuropathology of HIV/AIDS. Int Rev Psychiatry.. 2008;20:15–24.

Brew, B.J., Letendre, S.L. Biomarkers of HIV-related central nervous system disease. Int Rev Psychiatry.. 2008;20:73–88.

Collazos, J. Opportunistic infections of the CNS in patients with AIDS. Diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs.. 2003;17:869–887.

Di Rocco, A., Simpson, D.M. AIDS-associated vacuolar myelopathy. AIDS Patient Care STDS.. 1998;12:457–461.

Gray F., ed. Atlas of the neuropathology of HIV infection. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Green, D.A., Masliah, E., Vinters, H.V., et al. Brain deposition of beta-amyloid is a common pathologic feature in HIV positive patients. AIDS.. 2005;19:407–411.

Holloway, R.G., Mushlin, A.I. Intracranial mass lesions in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: Using decision analysis to determine the effectiveness of stereotactic brain biopsy. Neurology.. 1996;46:1010–1015.

Johnson, T., Nath, A. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol.. 2011;24:284–290.

Kaul, M. HIV-1 associated dementia: Update on pathological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Neurol.. 2009;22:315–320.

Kumar, A.M., Borodowsky, I., Fernandez, B., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA levels in different regions of human brain: Quantification using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Neurovirol.. 2007;13:210–224.

McCombe, J.A., Auer, R.N., Maingat, F.G., et al. Neurologic immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV/AIDS. Outcome and epidemiology. Neurology.. 2009;72:835–841.

Mocchetti, I., Bachis, A., Marliah, E. Chemokine receptors and neurotrophic factors: Potential therapy against AIDS dementia? J Neurosci Res.. 2008;86:243–255.

Petito, C.K., Kerza-Kwiatecki, A.P., Gendelman, H.E., et al. Review: neuronal injury in HIV infection. J Neurovirol.. 1999;5:327–341.

Power, C., Boisse, L., Rourke, S., et al. NeuroAIDS: An evolving epidemic. Can J Neurol Sci.. 2009;36:285–295.

Sacktor, N. The epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol.. 2002;8(suppl 2):115–121.

Scaravilli, F., Bazille, C., Gray, F. Neuropathologic contributions to understanding AIDS and the central nervous system. Brain Pathol.. 2007;17:197–208.

Vinters, H.V., Anders, K.H. Neuropathology of AIDS. Boca Raton: CRC press; 1990.

Vinters, H.V., Kwok, M.K., Ho, H.W., et al. Cytomegalovirus in the nervous system of patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Brain.. 1989;112:245–268.

Wiley, C.A., Soontornniyomkij, V., Radhakrishnan, L., et al. Distribution of brain HIV load in AIDS. Brain Pathol.. 1998;8:277–284.

Xu, J., Ikezu, T. The comorbidity of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: a foreseeable medical challenge in post-HAART era. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol.. 2009;4:200–212.

Bien, C.G., Elger, C.E., Leitner, Y., et al. Slowly progressive hemiparesis in childhood as a consequence of Rasmussen encephalitis without or with delayed-onset seizures. Eur J Neurol.. 2007;14:387–390.

Bien, C.G., Widman, G., Urbach, H., et al. The natural history of Rasmussen’s encephalitis. Brain.. 2002;125:1751–1759.

Freeman, J.M. Rasmussen’s syndrome: progressive autoimmune multi-focal encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol.. 2005;32:295–299.

Pardo, C.A., Vining, E.P., Guo, L., et al. The pathology of Rasmussen syndrome: stages of cortical involvement and neuropathological studies in 45 hemispherectomies. Epilepsia.. 2004;45:516–526.

Wagner, A.S., Yin, N.S., Tung, S., et al, Intimal thickening of meningeal arteries after serial corticectomies for Rasmussen encephalitis. Hum Pathol. 2012. [[Epub ahead of print]].