Miscellaneous CNS neoplasms and cysts

Diverse neoplasms covered in this chapter are:

glial tumors of uncertain origin

glial tumors of uncertain origin

mesenchymal non-meningothelial neoplasms, including vasoformative neoplasms

mesenchymal non-meningothelial neoplasms, including vasoformative neoplasms

In addition, there is a section on heterogeneous cysts/neoplasm-like entities.

GLIAL TUMORS OF UNCERTAIN ORIGIN

ASTROBLASTOMA

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

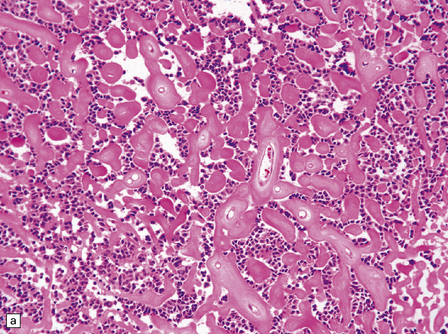

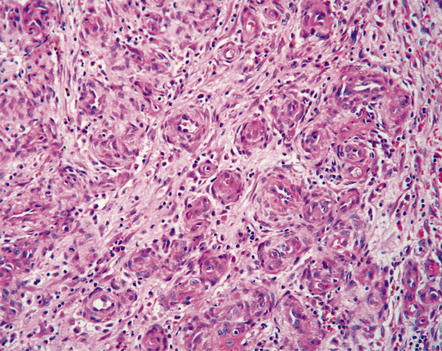

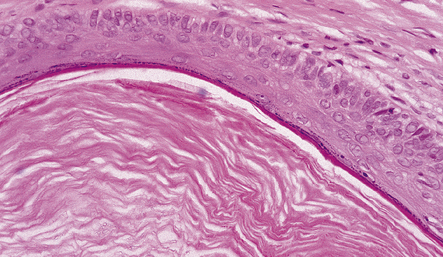

The astroblastoma is usually a solid uniform mass of firm, yet slightly mucoid tissue, though cyst formation can occur. It is characterized microscopically by two particular features: astroblastomatous rosettes (Fig. 45.1) and a focal hyalinization of its vascular network (Fig. 45.2). The astroblastomatous rosette is centered on a capillary, onto which slightly stubby cytoplasmic processes project from uniform cells with round or oval nuclei. The tumor cells may have either indistinct cytoplasmic borders or an epithelioid appearance. Sometimes, they show artifactual perinuclear clearing, reminiscent of cells in most oligodendrogliomas. The mitotic count is variable, as is the presence of necrosis. Vascular proliferation is rarely like that seen in glioblastomas. Instead, the astroblastoma’s angiogenesis may sometimes simulate that found in pilocytic astrocytomas.

45.1 Astroblastoma. (a) The astroblastomatous rosette forms around a capillary and is characterized by a corona of short fibrillary processes from perivascular tumor cells. (b) Tumor cells in astroblastomas tend to have a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio and monomorphic nuclei.

ANGIOCENTRIC GLIOMA

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Macroscopically, angiocentric gliomas expand and distort involved brain. Microscopically, they consist of uniform cells with oval or spindle-shaped nuclei. Generally, cytoplasmic processes or borders are poorly defined, though some cells appear epithelioid. Characteristically, tumor cells have a distinctive alignment around blood vessels of varying caliber (Fig. 45.3), either parallel to blood flow or as a rosette with nuclei pointing to the lumen. Tumor cells are not within the perivascular space, a location often invaded by other types of diffuse glioma. Invasion of cerebral tissues is observed, in the manner of other diffuse gliomas, including a tendency to congregate around neurons. Necrosis and angiogenesis are absent, and dystrophic calcification is rare. Mitotic figures are very rare.

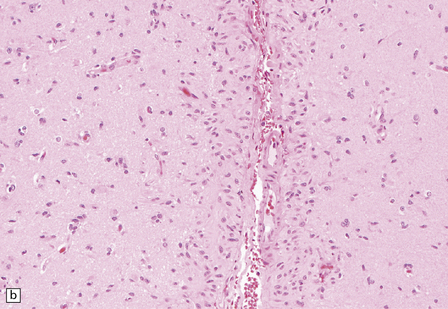

45.3 Angiocentric glioma (a) At low power, perivascular and infiltrative tumor cell patterns can discerned, as can aggregates of subpial cells (b). EMA immunoreactivity is demonstrated by most tumor cells (c).

Neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for GFAP and S-100. Intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity for EMA is reminiscent of that seen in ependymomas (Fig. 45.3c), and microlumina with microvilli and cilia are evident at the ultrastructural level.

CHORDOID GLIOMA OF THE THIRD VENTRICLE

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

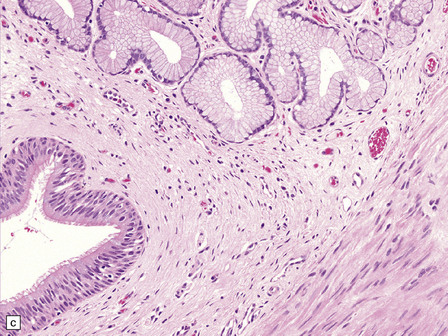

The mucoid nature of this generally solid neoplasm may be apparent macroscopically. It is composed of cords or sheets of epithelioid cells variably set against a myxoid matrix, regions of which show microvacuolation and contain a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Fig. 45.4). A few cells demonstrate fibrillary cytoplasmic processes, hinting at glial differentiation. Mitoses are absent or sparse. Tumor cells are GFAP-positive and immunoreactive for vimentin and CD34. Occasionally, a few cells are immunoreactive for EMA. Widespread immunoreactivity for EMA, but none for GFAP, distinguishes the chordoid meningioma from the chordoid glioma.

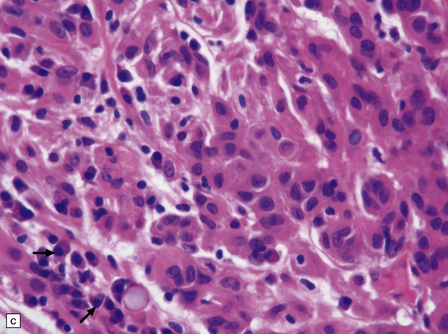

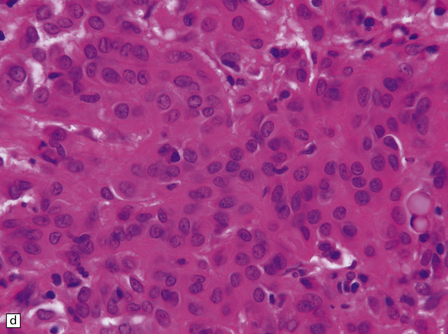

45.4 Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. (a) Cords of tumor cells, focal microvacuolation, and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate are characteristic. (b) A vague trabecular arrangement of moderately uniform cells is evident, along with microvacuolation and a myxoid background. (c) A mixture of epithelioid cells and cells with fibrillary cytoplasmic processes is present. Note the plasma cells (arrows) and the Russell bodies. (d) Cytoplasmic borders are apparent in this population of epithelioid cells.

MESENCHYMAL NON-MENINGOTHELIAL NEOPLASMS

LIPOMA

CNS lipomas are rare. They occur preferentially in the anterior part of the corpus callosum (usually in association with its partial agenesis, see Chapter 3), over the quadrigeminal plate, in the cerebellopontine angle, at the base of the brain, and in the spinal cord. Lipomas of the lumbosacral cord are sometimes associated with neural tube defects.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

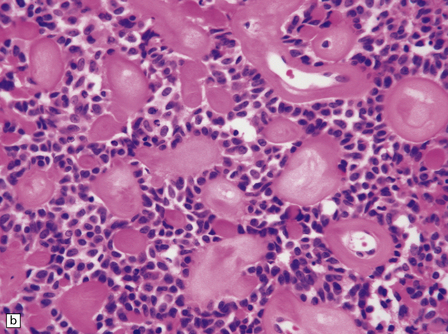

Lipomas are soft yellow masses (Figs 45.5, 45.6) and usually encroach upon adjacent structures. They are composed of mature lipocytes, but rarely they contain other ectopic tissues such as striated muscle and cartilage. Spinal examples may be poorly defined and occasionally contain prominent blood vessels (angiolipoma).

SOLITARY FIBROUS TUMOR OF THE MENINGES

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

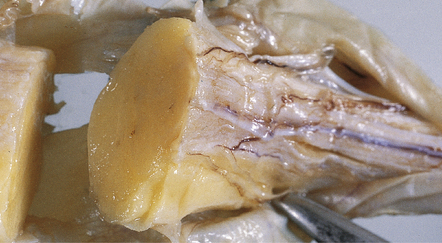

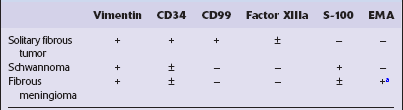

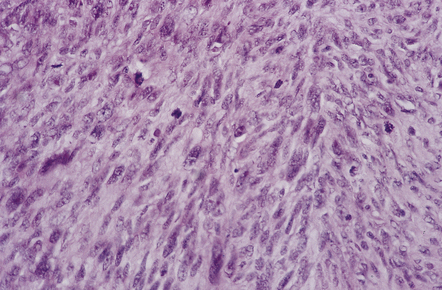

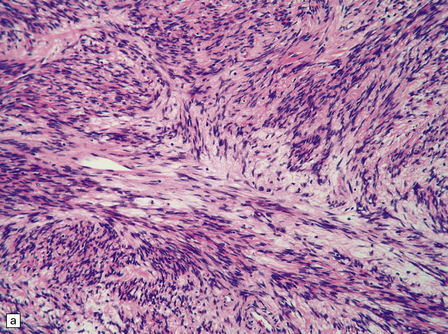

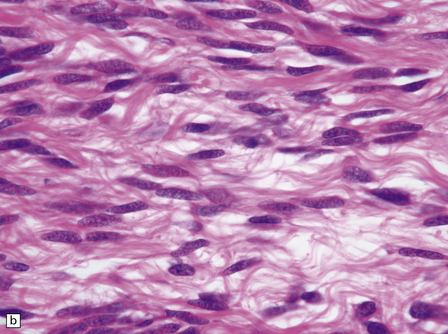

The solitary fibrous tumor looks just like a meningioma. It is usually affixed to dura, projecting away from this structure as a globular mass. Microscopically, the uniform spindle-shaped tumor cells form interweaving fascicles (Fig. 45.7), and bundles of collagen parallel the elongated nuclei. The collagen can become dense, diminishing the tumor’s cellularity. Mitoses are rare.

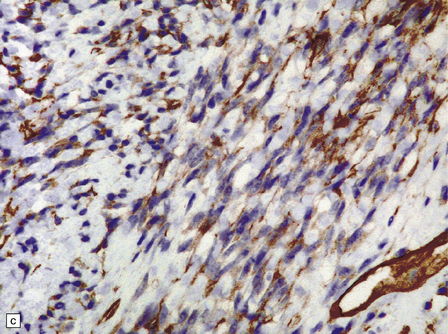

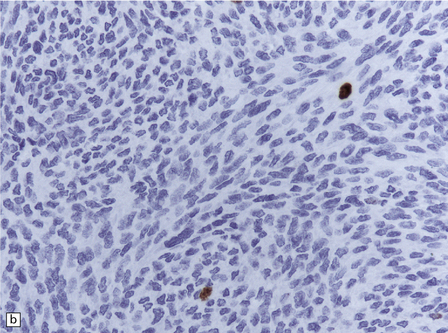

45.7 Solitary fibrous tumor of the meninges. (a) The monomorphic cells have a fascicular arrangement. (b) Serpentine collagenous bands weave between elongated nuclei. (c) Tumor cells are immunoreactive for CD34.

Immunohistochemistry reveals reactivities for CD34, CD99, factor XIIIa, and vimentin, but not EMA or S-100. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analyses help to confirm the non-meningothelial status of this tumor, and the use of these six antibodies allows the solitary fibrous tumor to be distinguished from meningioma and schwannoma (Table 45.1).

VASOFORMATIVE NEOPLASMS

Vasoformative neoplasms of the CNS include the hemangioma (Fig. 45.8), epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, hemangiopericytoma, and angiosarcoma. Hemangiomas that encroach on the CNS usually arise in the thoracic spine. Hemangiopericytomas account for less than 0.5% of primary CNS neoplasms, and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcomas are very rare. Angiosarcomas can occur in the context of previous radiotherapy to the neuraxis.

HEMANGIOPERICYTOMA

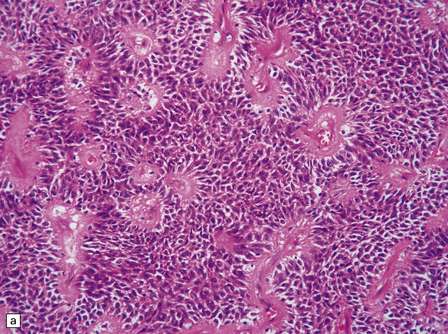

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

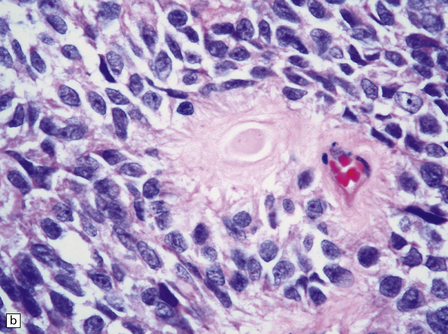

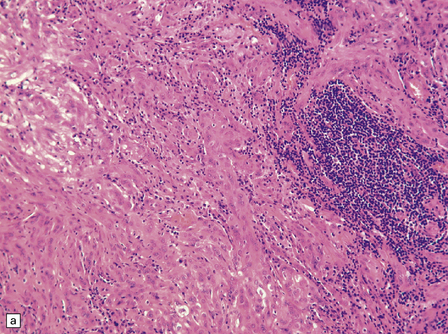

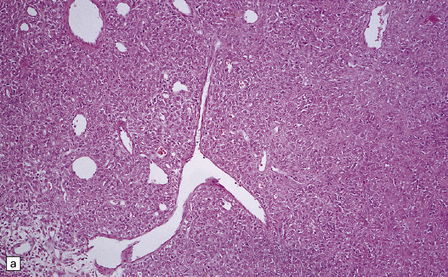

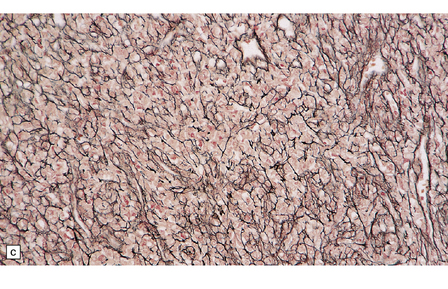

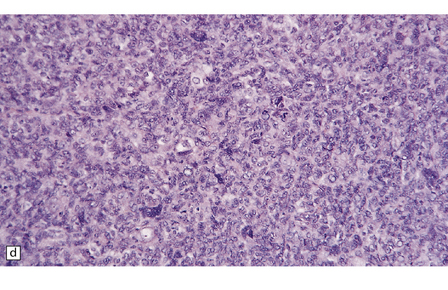

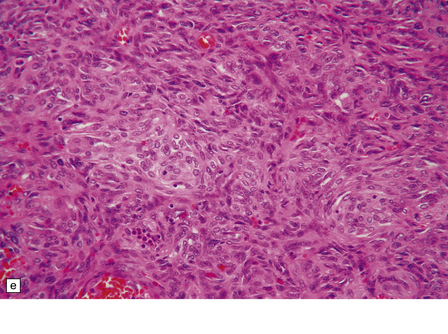

Hemangiopericytomas are usually spherical and discrete, but may invade the skull. They have a firm and homogeneous texture. Microscopically, many hemangiopericytomas are characterized by a uniform histologic appearance with a sheet-like arrangement of cells having a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 45.9). The cells are interspersed with many tiny capillaries, and a few larger, slightly gaping, vascular channels that may have a branching appearance. Other characteristics include focal lobularity, paucicellular areas, and dense pericellular reticulin. Diffuse fibrosis is sometimes seen. Mitoses are readily found, but foci of necrosis are uncommon. Cytologic pleomorphism and a high mitotic count are usually associated with rapid growth and aggressive behavior. The classic hemangiopericytoma is WHO grade II, but tumors with at least 5 mitoses per 10 HPFs and some of the following features: necrosis, hemorrhage, and increased nuclear pleomorphism or cell density, are regarded as anaplastic and WHO grade III.

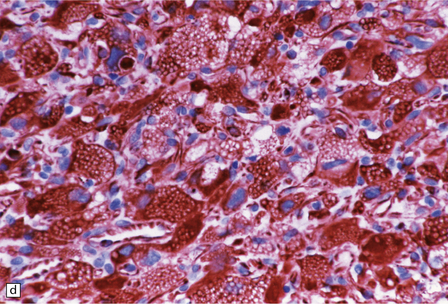

45.9 Hemangiopericytoma. (a) This is characterized at low magnification by a sheet of neoplastic cells interspersed with dilated blood vessels. One of the blood vessels in this field has a typical ‘stag horn’ shape. (b) At higher magnification, smaller vascular channels can be discerned between the closely packed cells, which have oval or asymmetrically tapered nuclei and a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio. Mitoses are evident. (c) Hemangiopericytomas have a dense reticulin pattern and this feature helps to distinguish them from meningiomas. (d) Cytologic pleomorphism and a high mitotic count are shown by some hemangiopericytomas and are usually associated with rapid growth and particularly aggressive behavior. (e) Typical histologic features of hemangiopericytoma were recorded elsewhere in this tumor, which in this region shows whorls of cells reminiscent of a meningioma. The cells in these structures were not immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen.

SARCOMAS

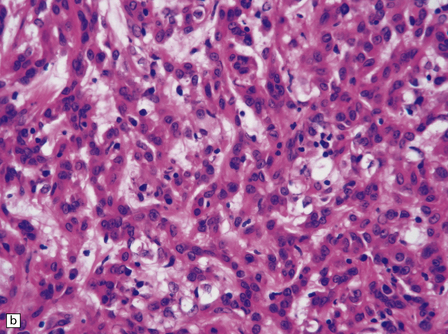

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Sarcomas are generally composed of anaplastic spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 45.10). There are usually abundant mitoses and foci of necrosis. Individual histologic characteristics sometimes allow subclassification. For example:

a vasoformative pattern is seen in angiosarcomas

a vasoformative pattern is seen in angiosarcomas

fascicles arranged in a ‘herring-bone’ pattern are typical of fibrosarcomas.

fascicles arranged in a ‘herring-bone’ pattern are typical of fibrosarcomas.

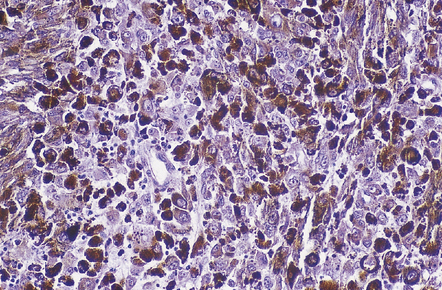

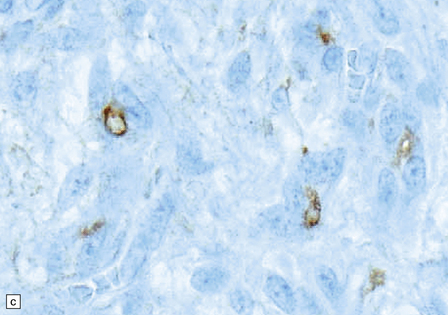

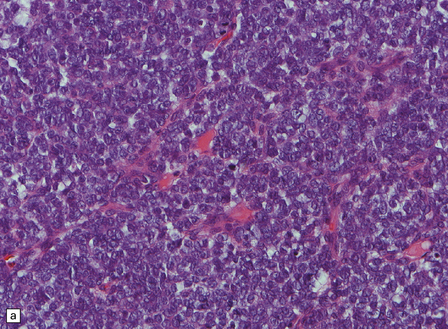

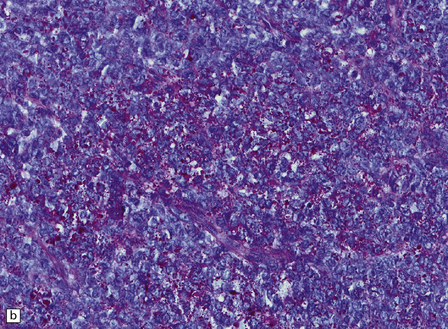

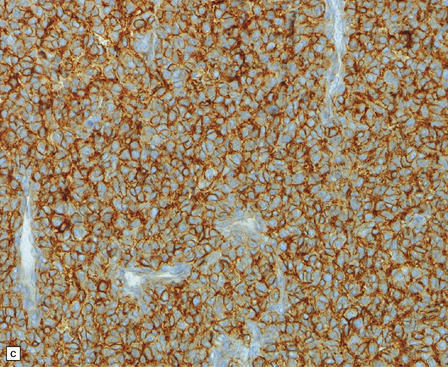

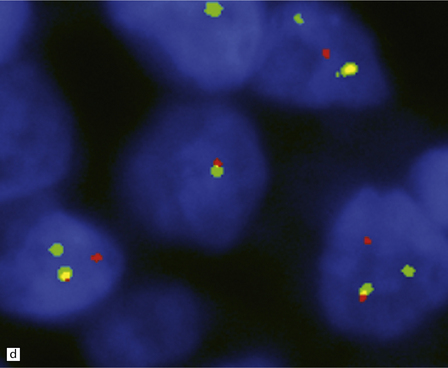

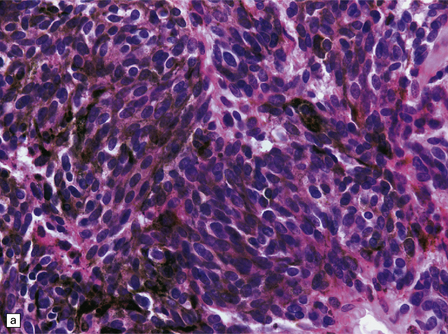

An important entity in this group to recognize when considering the differential diagnosis of intracranial or spinal embryonal tumors is the peripheral PNET, which is synonymous with extra-skeletal Ewing sarcoma. Ewing sarcoma itself, arising in the skull or vertebra, may also impinge on the CNS. Histopathologically (Fig. 45.11a–c), this tumor usually appears as sheets of small round cells with a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio and nuclear hyperchromasia. Mitotic activity is readily detected. Intracytoplasmic glycogen is a frequent finding. Immunoreactivity for neuronal antigens is evident, along with strong membranous immunostaining for CD99. A pathognomonic cytogenetic abnormality involving fusion of EWSR1 with several gene partners, usually FLI1, should be sought (Fig. 45.11d).

45.11 Peripheral PNET/Ewing sarcoma (a) This tumor consists of densely packed small round cells with nuclear hyperchromasia, and thus appears identical to many CNS PNETs. (b) Cytoplasmic glycogen is a feature of many examples. (c) Widespread strong immunoreactivity for CD99 is evident. (d) EWSR1 translocation and gene fusion were suggested in this case by the results of interphase FISH with a ‘break apart’ probe; the separated red and green signals indicate that a translocation of EWSR1 has occurred.

MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASMS

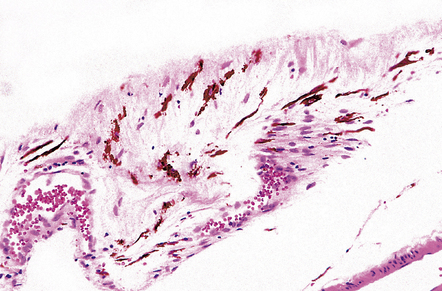

Melanocytes are normally present in the leptomeninges (Fig. 45.12), and give rise to various neoplasms recognized by the WHO classification. These are:

45.12 Meningeal melanocytes.

Metastatic malignant melanomas greatly outnumber primary melanocytic neoplasms.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

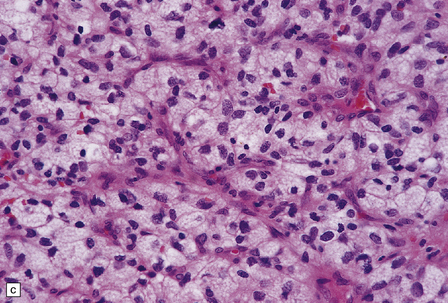

Cells in diffuse melanosis and melanocytoma tend to be arranged in nests or sheets. They are uniform with oval or spindle-shaped nuclei (Fig. 45.13). Mitoses are rare, and necrosis is absent. Melanin may be abundant or patchy.

45.13 Meningeal melanocytoma. (a) These tumors typically consist of fascicles of fusiform cells with little pleomorphism, no necrosis, and only scanty mitotic figures. Melanin is usually abundant. (b) Only occasional nuclei are immunopositive for Ki-67.

Malignant melanomas (Fig. 45.14) show cytologic atypia, an increased mitotic count, and necrosis, and invade adjacent structures. Neoplasms showing intermediate histology between those of melanocytoma and malignant melanoma are difficult to classify.

HEMANGIOBLASTOMA

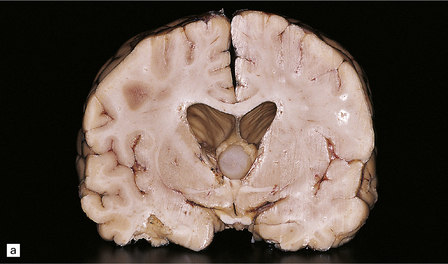

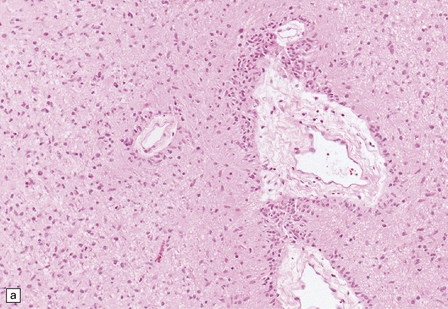

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

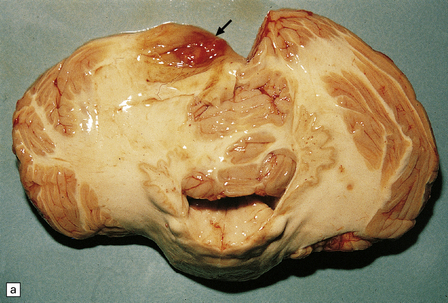

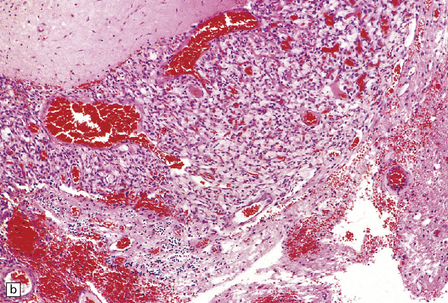

Cerebellar hemangioblastomas frequently present as cysts with a mural nodule (Fig. 45.15), and their vascular nature imparts a red color to the nodule. The mural nodule is composed of clusters of neoplastic cells and may be minute. Surgical specimens of cyst wall should be examined carefully for neoplastic cells.

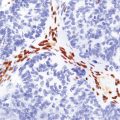

45.15 Hemangioblastoma. (a) A red nodule is present on the superomedial aspect of the cerebellar hemisphere (arrow). (b) This histologic field shows a vascular neoplasm abutting brain tissue. (c) Lipid-containing interstitial cells dominate the histology of this hemangioblastoma. (d) Cells in the hemangioblastoma are strongly immunopositive for vimentin. (Courtesy of Dr T Revesz, Institute of Neurology, London, UK.)

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

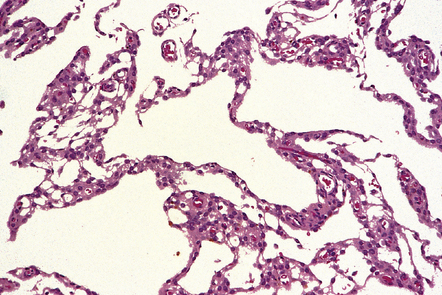

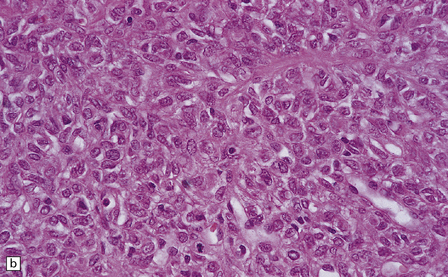

Hemangioblastomas comprise two cell populations, which are combined in varying proportions:

One population consists of endothelial cells and pericytes, which form a dense network of small vascular channels.

One population consists of endothelial cells and pericytes, which form a dense network of small vascular channels.

The second (neoplastic) population consists of interstitial (stromal) cells, which contain lipid and variable amounts of glycogen and which often show nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia.

The second (neoplastic) population consists of interstitial (stromal) cells, which contain lipid and variable amounts of glycogen and which often show nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia.

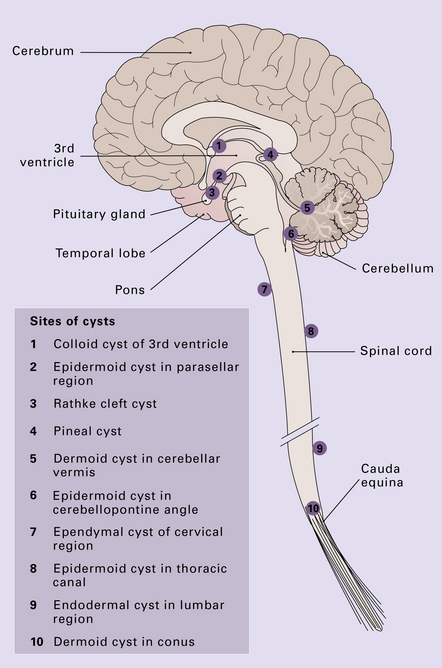

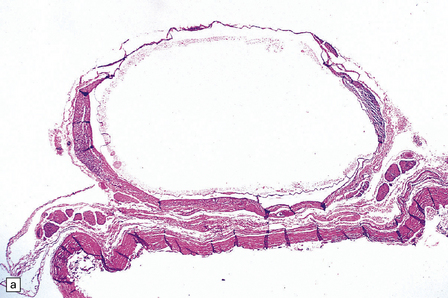

CYSTS

Benign cysts occur at several sites in and around the CNS (Fig. 45.16) and the cysts considered in this chapter are: epidermoid and dermoid cysts; colloid cyst of the third ventricle; endodermal (enterogenous) cyst; ependymal (neuroglial) cyst, and arachnoid cyst. The pineal cyst is included in Chapter 39.

EPIDERMOID AND DERMOID CYSTS

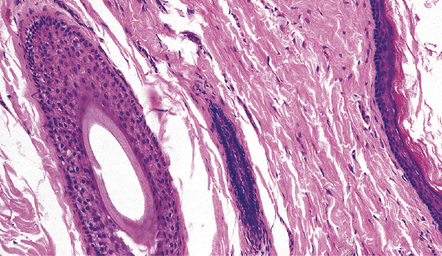

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

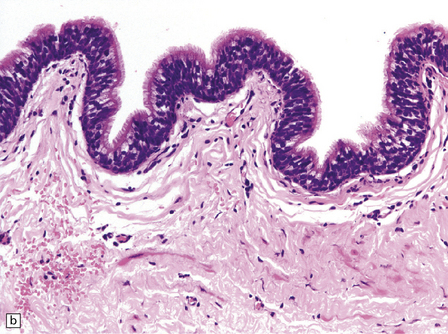

Both epidermoid (Fig. 45.17) and dermoid (Fig. 45.18) cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium. The central eosinophilic material is formed from degenerate keratinocytes plus secretions from sebaceous glands in the case of the dermoid cyst. The dermoid cyst is distinguished by the presence of adnexal appendages such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles.

COLLOID CYST OF THE THIRD VENTRICLE

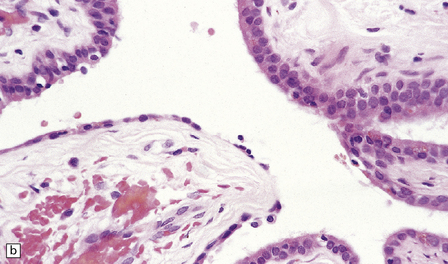

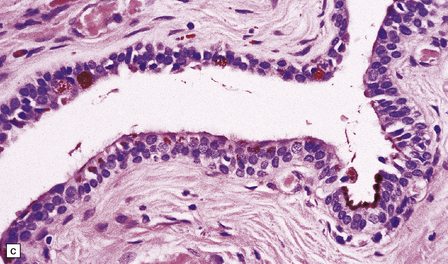

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Nearly all colloid cysts are found in the anterior part of the third ventricle (Fig. 45.19), though some examples are located in the posterior part of the third ventricle, and rare examples have been reported in the lateral and fourth ventricles. They are usually lined by a single layer of columnar cells, some of which are ciliated or contain mucin (Fig. 45.19c). Like the endodermal cyst, the colloid cyst has an epithelium with a cytokeratin-positive and EMA-positive immunophenotype.

ENDODERMAL CYST

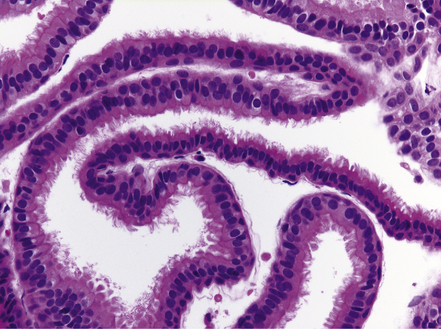

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Endodermal cysts are simple fluid-filled sacs (Fig. 45.20a) Their thin walls are lined by a columnar or cuboidal epithelium, which covers a connective tissue stroma. The cyst epithelium may show features of a gastrointestinal or respiratory epithelium (Fig. 45.20b). Goblet cells are readily found, but ciliation is a variable feature (Fig. 45.20c). Squamous metaplasia is sometimes seen. The underlying stroma may contain glands, lymphoid tissue or even glial elements.

45.20 Endodermal (enterogenous) cyst. (a) This cyst displaced and compressed the spinal cord at T11. (b) This epithelium is respiratory in nature, displaying surface cilia and containing goblet cells. (c) This example has a ciliated epithelium, and its stroma contains glands and smooth muscle.

The epithelium shows immunoreactivities for cytokeratins and EMA, but not GFAP.

EPENDYMAL CYST

REFERENCES

Gliomas of undetermined origin

Bonnin, J.M., Rubinstein, L.J. Astroblastomas: a pathological study of 23 tumors, with a postoperative follow-up in 13 patients. Neurosurgery.. 1989;25(1):6–13.

Brat, D.J., Hirose, Y., Cohen, K.J., et al. Astroblastoma: clinicopathologic features and chromosomal abnormalities defined by comparative genomic hybridization. Brain Pathol.. 2000;10(3):342–352.

Brat, D.J., Scheithauer, B.W., Staugaitis, S.M., et al. Third ventricular chordoid glioma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 1998;57(3):283–290.

Horbinski, C., Dacic, S., McLendon, R.E., et al. Chordoid glioma: a case report and molecular characterization of five cases. Brain Pathol.. 2009;19(3):439–448.

Leeds, N.E., Lang, F.F., Ribalta, T., et al. Origin of chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. Arch Pathol Lab Med.. 2006;130(4):460–464.

Pasquier, B., Péoc’h, M., Morrison, A.L., et al. Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: a report of two new cases, with further evidence supporting an ependymal differentiation, and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(10):1330–1342.

Reifenberger, G., Weber, T., Weber, R.G., et al. Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: immunohistochemical and molecular genetic characterization of a novel tumor entity. Brain Pathol.. 1999;9(4):617–626.

Mesenchymal non-meningothelial neoplasms

Brunori, A., Cerasoli, S., Donati, R., et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the meninges: two new cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol.. 1999;51(6):636–640.

Budka, H. Intracranial lipomatous hamartomas (intracranial “lipomas”). A study of 13 cases including combinations with medulloblastoma, colloid and epidermoid cysts, angiomatosis and other malformations. Acta Neuropathol (Berl).. 1974;28(3):205–222.

Chang, S.M., Barker, F.G., 2nd., Larson, D.A., et al. Sarcomas subsequent to cranial irradiation. Neurosurgery.. 1995;36(4):685–690.

Coffin, C.M., Hornick, J.L., Fletcher, C.D. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol.. 2007;31(4):509–520.

Fletcher, C.D. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology.. 2006;48(1):3–12.

Gaspar, L.E., Mackenzie, I.R., Gilbert, J.J., et al. Primary cerebral fibrosarcomas. Clinicopathologic study and review of the literature. Cancer.. 1993;72(11):3277–3281.

Guthrie, B.L., Ebersold, M.J., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: histopathological features, treatment, and long-term follow-up of 44 cases. Neurosurgery.. 1989;25(4):514–522.

Jellinger, K., Paulus, W. Mesenchymal, non-meningothelial tumors of the central nervous system. Brain Pathol.. 1991;1(2):79–87.

Mena, H., Ribas, J.L., Pezeshkpour, G.H., et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the central nervous system: a review of 94 cases. Hum Pathol.. 1991;22(1):84–91.

Oliveira, A.M., Scheithauer, B.W., Salomao, D.R., et al. Primary sarcomas of the brain and spinal cord: a study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.. 2002;26(8):1056–1063.

Paulus, W., Slowik, F., Jellinger, K. Primary intracranial sarcomas: histopathological features of 19 cases. Histopathology.. 1991;18(5):395–402.

Rajaram, V., Brat, D.J., Perry, A. Anaplastic meningioma versus meningeal hemangiopericytoma: immunohistochemical and genetic markers. Hum Pathol.. 2004;35(11):1413–1418.

Swain, R.S., Tihan, T., Horvai, A.E., et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the central nervous system and its relationship to inflammatory pseudotumor. Hum Pathol.. 2008;39(3):410–419.

Tihan, T., Viglione, M., Rosenblum, M.K., et al. Solitary fibrous tumors in the central nervous system. A clinicopathologic review of 18 cases and comparison to meningeal hemangiopericytomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med.. 2003;127(4):432–439.

Wiebe, S., Munoz, D.G., Smith, S., et al. Meningioangiomatosis. A comprehensive analysis of clinical and laboratory features. Brain.. 1999;122(Part4):709–726.

Brat, D.J., Giannini, C., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous systems. Am J Surg Pathol.. 1999;23(7):745–754.

Litofsky, N.S., Zee, C.S., Breeze, R.E., et al. Meningeal melanocytoma: diagnostic criteria for a rare lesion. Neurosurgery.. 1992;31(5):945–948.

Reyes-Mugica, M., Chou, P., Byrd, S., et al. Nevomelanocytic proliferations in the central nervous system of children. Cancer.. 1993;72(7):2277–2285.

Boughey, A.M., Fletcher, N.A., Harding, A.E. Central nervous system haemangioblastoma: a clinical and genetic study of 52 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 1990;53(8):644–648.

Hasselblatt, M., Jeibmann, A., Gerss, J., et al. Cellular and reticular variants of haemangioblastoma revisited: a clinicopathologic study of 88 cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol.. 2005;31(6):618–622.

Joseph, J.T., Lisle, D.K., Jacoby, L.B., et al. NF2 gene analysis distinguishes hemangiopericytoma from meningioma. Am J Pathol.. 1995;147(5):1450–1455.

Maher, E.R., Neumann, H.P., Richard, S. von Hippel-Lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet.. 2011;19(6):617–623.

Neumann, H.P., Lips, C.J., Hsia, Y.E., et al. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Brain Pathol.. 1995;5(2):181–193.

Shehata, B.M., Stockwell, C.A., Castellano-Sanchez, A.A., et al. Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: an update on the clinico-pathologic and genetic aspects. Adv Anat Pathol.. 2008;15(3):165–171.

Traen, S., Seynaeve, R., Cardoen, L., et al. Central nervous system lesions in Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. JBR-BTR.. 2011;94(3):140–141.

Agnoli, A.L., Laun, A., Schönmayr, R., et al. Enterogenous intraspinal cysts. J Neurosurg.. 1984;61(5):834–840.

Agnoli, A.L., Schönmayr, R., Laun, A., et al. Intraspinal arachnoid cysts. Acta Neurochir (Wien).. 1982;61(4):291–302.

Berger, M.S., Wilson, C.B. Epidermoid cysts of the posterior fossa. J Neurosurg.. 1985;62(2):214–219.

Boockvar, J.A., Shafa, R., Forman, M.S., et al. Symptomatic lateral ventricular ependymal cysts: criteria for distinguishing these rare cysts from other symptomatic cysts of the ventricles: case report. Neurosurgery.. 2000;46(5):1229–1233.

Friede, R.L., Yasargil, M.G. Supratentorial intracerebral epithelial (ependymal) cysts: review, case reports, and fine structure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 1977;40(2):127–137.

Guidetti, B., Gagliardi, F.M. Epidermoid and dermoid cysts. Clinical evaluation and late surgical results. J Neurosurg. 1977;47(1):12–18.

Hamlat, A., Hua, Z.F., Saikali, S., et al. Malignant transformation of intra-cranial epithelial cysts: systematic article review. J Neurooncol.. 2005;74(2):187–194.

Inoue, T., Matsushima, T., Fukui, M., et al. Immunohistochemical study of intracranial cysts. Neurosurgery.. 1988;23(5):576–581.

Jeffree, R.L., Besser, M. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle: a clinical review of 39 cases. J Clin Neurosci.. 2001;8(4):328–331.

Klein, P., Rubinstein, L.J. Benign symptomatic glial cysts of the pineal gland: a report of seven cases and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 1989;52(8):991–995.

Lach, B., Scheithauer, B.W., Gregor, A., et al. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle. A comparative immunohistochemical study of neuraxis cysts and choroid plexus epithelium. J Neurosurg.. 1993;78(1):101–111.

Perry, A., Scheithauer, B.W., Zaias, B.W., et al. Aggressive enterogenous cyst with extensive craniospinal spread: case report. Neurosurgery.. 1999;44(2):401–405.

Shenoy, S.N., Raja, A. Spinal neurenteric cyst. Report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg.. 2004;40(6):284–292.