Chapter 37 Cholecystolithiasis and stones in the common bile duct

Which approach and when?

Cholecystolithiasis

Indications for Cholecystectomy

Asymptomatic Gallstones

Surprisingly, most patients with gallstones, about 65% to 80%, are asymptomatic (see Chapter 30). Studies of the natural history of silent gallstones have shown that symptoms develop in 1% to 2% of patients per year. Among patients with asymptomatic gallstones, about 10% develop symptoms in 5 years, and about 20% develop symptoms by 20 years. Additionally, most patients experience symptoms for some time before they develop a complication (National Institutes of Health [NIH] Consensus Statement Online, 1992; Stewart et al, 1989; Festi et al, 2010; McSherry et al, 1985). So, the majority of patients with asymptomatic gallstones can be observed, and surgical intervention (laparoscopic cholecystectomy) can be offered if symptoms develop.

Surgical treatment of asymptomatic gallstones is indicated in a number of patient populations for whom prophylactic cholecystectomy was once recommended. These populations comprise transplant patients and those with diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, sickle cell anemia or other chronic hemolytic anemia, patients undergoing bariatric or other gastrointestinal operations, and those with a potentially increased risk of gallbladder carcinoma (Table 37.1).

| Patient Population | Management |

|---|---|

| Healthy adults | Expectant |

| Children (without hemoglobinopathy or hemolytic anemia) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Chronic liver disease | |

| Previous bariatric procedure | |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | |

| Transplant Kidney or pancreas Cardiac | ExpectantCholecystectomy posttransplant |

| Undergoing gastrointestinal operation | Incidental cholecystectomy |

| Hemoglobinopathy/chronic hemolytic anemia (sickle cell disease, spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, β-thalassemia) | Elective cholecystectomy |

| High-risk group for gallbladder carcinoma (>3 cm gallstones, calcified gallbladder, Native American race) |

Prophylactic cholecystectomy for asymptomatic cholelithiasis was previously recommended for patients with diabetes mellitus. Studies in the late 1960s reported a higher mortality following emergency cholecystectomy in diabetic patients. Subsequent meta-analysis revealed that diabetes was not an independent variable; instead, cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular, or prerenal azotemia were associated with more severe acute cholecystitis (Stewart et al, 1989; Hickman et al, 1988). More recent series have shown similar complication rates for acute cholecystectomy among diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Diabetic patients with asymptomatic gallstones today are managed expectantly.

The incidence of gallstones is twice as high in patients with chronic liver disease. Most of these patients remain asymptomatic. Operative morbidity and mortality rates for patients with chronic liver disease are also significantly higher. Meta-analyses report no increase in mortality in asymptomatic patients with an expectant management approach (Stewart et al, 1989; NIH Consensus Statement Online, 1992).

Patients undergoing bariatric surgery have a higher incidence of cholelithiasis, because obesity is associated with cholelithiasis, and gallstones may form during rapid weight loss. Studies report a cholelithiasis incidence of 27% to 35% before bariatric operations and a 28% to 71% increase in gallstone formation following bariatric surgery (Wudel et al, 2002). Many surgeons utilize bile salt medications during periods of rapid weight to help prevent cholesterol gallstones. But even if gallstones form, most are asymptomatic, and elective cholecystectomy is safe for symptomatic disease (NIH Consensus Statement Online, 1992).

Several factors must be considered for potential transplant patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis: cholelithiasis is common, immunosuppression may increase infectious morbidity, and morbidity and mortality may be increased with emergency surgery. This problem was examined with a recent decision analysis, using probabilities and outcomes derived from a pooled analysis of published studies (Kao et al, 2005). The authors recommended prophylactic posttransplantation cholecystectomy for cardiac transplant recipients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis. For pancreas and kidney transplant patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis, however, expectant management was recommended.

Asymptomatic gallstones found at another gastrointestinal operation should generally be removed if exposure is adequate, if the cholecystectomy can be done safely. Studies of expectant management for patients with asymptomatic gallstones undergoing laparotomy for other conditions have shown a high (up to 70%) incidence of symptoms and/or complications from the biliary system, and a significant percentage (up to 40%) of patients require a cholecystectomy within 1 year of the initial operation. Further, no increase in morbidity is associated with concomitant cholecystectomy (Stewart et al, 1989; Klaus et al, 2002).

The management of patients with asymptomatic gallstones undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair has recently evolved, especially with the advent of endovascular aortic procedures. In the past, when AAA repair and cholecystectomy were open operations, concomitant cholecystectomy was recommended to prevent the higher morbidity associated with the development of acute cholecystitis in the postoperative period. Studies reported no increase in graft infection or morbidity when cholecystectomy was done following closure of the retroperitoneum; however, more recent data show similar mortality rates with or without concomitant cholecystectomy. Today, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is typically performed after endovascular AAA repair, without increased morbidity (Cadot et al, 2002).

Children with asymptomatic gallstones comprise two main etiologic groups: those with hemolytic anemia (sickle cell disease, β-thalassemia, hemoglobinopathies) and those whose cholelithiasis stems from some other cause (total parenteral nutrition, short bowel syndrome, cardiac surgery, leukemia, lymphoma). Expectant management for children with hemolytic anemia is associated with a significant increase in morbidity and postoperative hospital stay, so elective cholecystectomy is recommended (Curro et al, 2007). For patients with sickle cell disease and asymptomatic gallstones, elective cholecystectomy is advised, because expectant management yields more than a twofold increase in morbidity. Further, the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis can be difficult to differentiate from acute vasoocclusive sickle cell crisis (Curro et al, 2007). In contrast, children with asymptomatic gallstones caused by other etiologies can be safely managed expectantly. These gallstones even regress in 17% to 34% of cases.

Finally, gallstones have a proven association with gallbladder carcinoma (Tewari, 2006; see Chapter 49). In a review of 200 consecutive calculous cholecystitis specimens, Albores-Saavedra and colleagues (1980) reported that 83% exhibited epithelial hyperplasia, 13.5% atypical hyperplasia, and 3.5% carcinoma in situ. The risk of gallbladder carcinoma increases with larger gallstones: the relative risk rises from 2.4 for stones 2 to 2.9 cm in diameter to 10 for gallstones larger than 3 cm. Native Americans and patients with gallbladder calcification also have a higher incidence of gallbladder cancer. Elective cholecystectomy has been recommended in patients with gallstones greater than 3 cm in diameter, but no proof is available to support that such an approach is warranted from an oncologic standpoint.

Symptomatic Gallstones

Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis occurs in about 20% of patients with symptomatic gallstones (see Chapter 31). The pathogenesis is prolonged calculous obstruction of the cystic duct with resulting inflammation. The inflamed gallbladder becomes dilated and edematous, manifested by wall thickening, and an exudate of pericholecystic fluid can develop. If the gallstones are sterile, the inflammation is initially sterile, which can occur in patients with cholesterol gallstones. In other cases, however, gallstone formation occurs as a result of bacterial colonization of the biliary tree, rendering pigmented gallstones containing bacterial microcolonies (Stewart et al, 2002). In these cases, obstruction of the cystic duct results in a contained infection of the gallbladder. Research on the pathogenesis of gallstone-associated infections has shown that patients with bacteria-laden gallstones have more severe biliary infections. In addition, acute cholecystitis can coexist with choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, or gallstone pancreatitis. In the general population, 5% of patients presenting with cholecystitis have coexisting common bile duct stones. In the elderly, however, this figure rises to 10% to 20% (Siegel & Kasmin, 1997).

The initial treatment for patients with acute cholecystitis is intravenous hydration, antibiotics, and bowel rest. Many patients should be offered early cholecystectomy, but others will benefit from delayed intervention, either following conservative therapy or percutaneous gallbladder drainage. Several factors govern the approach to patients with acute cholecystitis. One consideration is patient comorbidity; emergency cholecystectomy in patients with significant comorbidities can be associated with high morbidity (20% to 30%) and mortality (6% to 30%) rates. Guidelines for the management of acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis were described at an international consensus meeting held in Tokyo in 2006 (Takada et al, 2007). The Tokyo Guidelines define three levels of severity for acute cholecystitis and serve as a useful tool in the management of acute cholecystitis (Table 37.2).

| Grade | Criteria |

|---|---|

| I Mild | Acute cholecystitis that does not meet the criteria for a more severe gradeMild gallbladder inflammation, no organ dysfunction |

| II Moderate | The presence of one or more of the following:1. Elevated while blood cell count (>18,000/mm3)2. Palpable tender mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant3. Duration of complaints >72 h4. Marked local inflammation (biliary peritonitis, pericholecystic abscess, hepatic abscess, gangrenous cholecystitis, emphysematous cholecystitis) |

| III Severe | The presence of one or more of the following:1. Cardiovascular system: hypotension requiring dopamine >5 µg/kg/min or any dose of dobutamine2. Nervous system: decreased level of consciousness3. Respiratory system: Pao2/Fio2 ratio <3004. Renal system: serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL5. Liver: PT-INR >1.56. Hematologic system: platelet count <100,000/mm3 |

PT-INR, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio

Grade I Acute Cholecystitis

Patients presenting with mild grade I acute cholecystitis should be offered early cholecystectomy, performed laparoscopically if possible; numerous studies document a high success rate for laparoscopic cholecystectomy when the procedure is performed within 48 to 96 hours of onset of acute cholecystitis (Hadad et al, 2007). Further, a Cochrane review of five randomized trials showed a shorter hospital stay for early cholecystectomy patients and no significant difference in complication rates or conversion rates between early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (within 7 days) versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy (6 to 12 weeks; Gurusamy & Samraj, 2006). Conversion rates, however, were 45% among patients randomized to the delayed group, those who required a cholecystectomy between 1 and 6 weeks. For patients with significant medical problems, cholecystectomy may need to be delayed to maximize medical therapy. Most patients with acute cholecystitis can be safely managed with antibiotics and bowel rest with resolution of their acute illness; they can then undergo an elective cholecystectomy once their medical problems have been addressed.

Grade II Acute Cholecystitis

Patients presenting with grade II acute cholecystitis are a more diverse group. Many will be well managed with early cholecystectomy; this is particularly true for cases with delayed presentation as their only grade II finding. In these cases, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed if possible within 7 days of the acute illness. In cases with severe local inflammation, early gallbladder drainage (percutaneous or surgical) is recommended as the initial treatment of choice, followed by elective cholecystectomy once the acute inflammation resolves. The key is to identify which patients have such an inflammatory process. Several studies have correlated such findings as age older than 50 years, male sex, presence of diabetes, elevated bilirubin level (>1.5 mg/dL), and leukocytosis (while blood cell count >15,000 mm3) in the setting of gangrenous cholecystitis (Nguyen et al, 2004). These findings are also frequently associated with a severe inflammatory process. Other factors suggestive of an inflammatory process include symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction. Patients with such symptoms should have cross-sectional imaging, with either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to determine whether a severe inflammatory process is present (Fig. 37.1), followed by percutaneous cholecystostomy if such is found (Takada et al, 2007).

Grade III Acute Cholecystitis

Patients presenting with grade III acute cholecystitis have associated organ dysfunction, and they require intensive organ support and medical treatment. Because the source of their inflammatory (septic) response and organ dysfunction is the severe cholecystitis, percutaneous cholecystostomy is necessary to treat the severe infection as well as the associated organ dysfunction. Numerous studies have documented the success of percutaneous cholecystostomy in achieving control of the underlying infection within 24 to 48 hours (Howard et al, 2009). In rare cases, urgent cholecystectomy may be required, such as cases with biliary peritonitis as a result of perforation of the gallbladder; but in general, cholecystectomy in the acute phase of grade III acute cholecystitis should be avoided (Takada et al, 2007).

Cholecystectomy Technique

Choosing Laparoscopic Versus Open Techniques

For typical uncomplicated gallstone disease, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred method of removing the gallbladder (Keus et al, 2006). Since its debut, cholecystectomy rates have increased worldwide, reflecting patient acceptance of the laparoscopic technique. Because the technical aspects of this operation are covered in other chapters (see Chapters 33 and 34), this section will focus on concepts of feasibility and safety that relate to disease severity and the choice between laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy (Callery, 2006).

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed only by surgeons properly trained and proctored, and experience should be correlated to how difficult the operation may be based on disease severity. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for severe acute and chronic inflammation is considerably more difficult and is an advanced operation. Less experienced surgeons must recognize this and seek the help they need during the operation, and conversion to open cholecystectomy may be necessary in some patients (Ishizaki et al, 2006). Biliary injuries are more likely to occur during difficult laparoscopic operations, no different than with open operations, but at a higher incidence (see Chapter 42A, Chapter 42B ). When laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed for acute cholecystitis, biliary injuries occur three times more often than during elective laparoscopic cases and twice as often compared with open cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis.

Today, the selection of open cholecystectomy may be difficult for some. Over the past 20 years, open cholecystectomy has been far less frequently performed. Trainees during this period presumably have received valid instruction and proctoring for laparoscopic cholecystectomy but have less experience with difficult open cases (Schulman et al, 2007). The experience needed to command the laparoscopic operation potentially reduces the level of comfort with the open technique. Finally, there is the pressure related to patient expectation for rapid recovery.

Behind these two very different techniques are scenarios that might subtly account in part for static biliary injury rates (Khan et al, 2007). Because of inexperience, the surgeon ignores or resists the sensible default option to convert to the open technique, does not, and causes injury. In other instances, the surgeon overextends laparoscopic experience when disease severity warrants conversion. What can help prevent this? First, during informed consent, patients need to be made fully aware that open cholecystectomy is always a possibility. If faced with acute or chronic cholecystitis at operation, the surgeon should seek help rather than persist on marginal laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy experience. Conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy is not a defeat but rather is reflective of caution and good judgment (Jenkins et al, 2007; Wolf, 2009).

The difficult open cholecystectomy demands adequate exposure, retraction, and identification of anatomy by dissection in the anterior and posterior aspects of the triangle of Calot, followed by dissection of the gallbladder off the liver bed. The surgeon achieves conclusive identification of the cystic structures as the only two structures entering the gallbladder, eliminating the possibility of misidentification (Callery, 2006). As with the laparoscopic technique, once the critical view is attained, the cystic structures can be occluded with ligatures and divided. Failure to achieve this critical view should prompt cholangiography to define ductal anatomy. Avoidance of ductal injury in the liver bed depends upon a combination of patience and staying in the correct plane of dissection, with meticulous technique and experience. In some cases of acute cholecystitis, the gallbladder “shells out” relatively easily from its edematous hepatic bed. In other cases, and especially in chronic cholecystitis, the dissection of the gallbladder out of the liver bed can be tedious, frustrating, and bloody. Hemostasis can take time but must be achieved, with argon beam, cautery, packing, and topical hemostatics if necessary. Subtotal cholecystectomy is always a valid option, especially in patients with cirrhosis or in those with severe inflammation that obscures the anatomy within the porta hepatis. Surgeons should indicate in operative notes for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy precisely how they identified the cystic structures for division. For conversions, they should specify the circumstances, stressing safety and surgical judgment.

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy (See Chapter 32)

The indications for percutaneous cholecystostomy include grade II acute cholecystitis with a severe inflammatory process, grade III acute cholecystitis with associated organ dysfunction, or acute cholecystitis in patients with severe medical morbidity that limits the surgical options (Takada et al, 2007; Hirota et al, 2007; Yamashita et al, 2007; Howard et al, 2009). The technical success rate of percutaneous radiologically guided cholecystostomy is 98% to 100% with few procedure-related complications (mortality and major complications, 0% to 6.5%; minor complications, 0% to 20%) (Howard et al, 2009; Sugiyama et al, 1998).

Timing of Subsequent Operation for Cholecystitis

Once the inflammatory process has resolved, elective cholecystectomy can be performed early (within 1 to 7 days) or delayed (6 to 8 weeks) with excellent success and conversion rates as low as 3% (Akyurek, 2005). Some have reported using percutaneous cholecystostomy as definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis in high-risk, elderly, and debilitated patients. In patients who do not have subsequent cholecystectomy, recurrent biliary symptoms occur in 9% to 33% (Griniatsos et al, 2008; Sugiyama et al, 1998).

Choledocholithiasis (See Chapter 35)

The clinical clues of common bile duct (CBD) stones were recognized during the Roman Empire by Soranus of Ephesus, who described jaundice, itching, dark urine, and acholic stools. Not all common bile duct stones render such a classic clinical scenario, but they still carry risk if left unidentified and untreated. More than 85% of CBD stones originate in the gallbladder and secondarily migrate into the CBD. For patients undergoing cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones, the prevalence of choledocholithiasis ranges from 10% to 15%. Primary CBD stones are far less common and are typically associated with conditions of biliary infection and stasis: benign biliary strictures, sclerosing cholangitis, and choledochal cysts. Primary CBD stones are more prevalent in Asians and can relate to parasitic infections (Kaufman et al, 1989).

Silent Common Bile Duct Stones

Published reports using routine intraoperative cholangiography have found that at least 12% of CBD stones are clinically silent (Murison et al, 1993), and approximately 6% do not exhibit abnormalities in liver function tests (LFTs) or in the diameter of the CBD (Majeed et al, 1999). When prospectively followed, data suggest that more than one third of asymptomatic stones will pass spontaneously after the first 6 weeks after cholecystectomy (Collins et al, 2004).

Diagnostic Considerations

More often than not, the presence of CBD stones is uncertain. Clinicians use predictive models based on risk factors that include clinical features, abnormal LFTs, jaundice, and CBD dilation. These are very sensitive (96% to 98%) but not very specific (0% to 70%) (Koo & Traverso, 1996). The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) provides a practical strategy that assigns low (<10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), or high (>50%) risk of CBD stones using relevant risk factors (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee et al, 2010).

Imaging Modalities: Why and When

Transabdominal Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound (US) is an appropriate initial modality in the evaluation of CBD stones (Williams et al, 2008). US can identify bile duct dilation owing to stone obstruction, and it can visualize the actual stone (sensitivity 0.3, specificity 1.0; see Chapter 13). If the extrahepatic bile duct diameter is less than 5 mm, CBD stones are exceedingly rare, whereas a diameter greater than 10 mm with jaundice predicts CBD stones in more than 90% of cases (Abboud et al, 1996). Axial CT scans have better sensitivity (84%) for choledocholithiasis than US (see Chapter 16). Helical CT scans outperform conventional nonhelical CT, with 88% sensitivity and 73% to 97% specificity (Tseng et al, 2008). In terms of availability, cost, and radiation exposure, US prevails as the first-line diagnostic.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the most accurate noninvasive modality available (see Chapter 17). Regardless, its sensitivity decreases for small CBD stones (29% if <5 mm) (Sugiyama et al, 1998). MRCP is the standard investigation for CBD stones for patients with intermediate probability or for those who need to be investigated to exclude other differential diagnoses. MRCP is especially helpful when anatomical considerations preclude endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP; status post–Billroth II gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y biliary bypass, duodenal stenoses).

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

ERCP is still considered the gold standard diagnostic modality (see Chapter 18), although it is invasive, requires radiation, and has significant complications (Andriulli et al, 2007). Routine ERCP prior to all laparoscopic cholecystectomies is impractical and unnecessary. When overused, most cholangiograms are normal, and costs and complication rates are prohibitive. Even in patients at high risk—those with jaundice, cholestatic LFTs, CBD dilation, and a history of pancreatitis—half will not have CBD stones at the time of ERCP (Daradkeh et al, 2000), therefore ERCP is now reserved more for its therapeutic than diagnostic strength.

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic US (EUS) is very sensitive for choledocholithiasis (see Chapter 14; Garrow et al, 2007), and a meta-analysis reveals that EUS can reduce unnecessary diagnostic ERCP (Tse et al, 2008). A systematic review reveals that patients who undergo EUS can avoid ERCP in 67% of cases, with fewer complications and less pancreatitis compared with those undergoing ERCP initially (Petrov & Savides, 2009). The diagnostic efficacy of EUS and MRCP compared with ERCP have revealed the tests to be quite comparable (Verma et al, 2006).

Real-Time Fluoroscopic Intraoperative Cholangiography

Real-time fluoroscopic intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) during cholecystectomy can accurately diagnose CBD stones and both minimize and maximize the need for ERCP (see Chapter 21). The technique can be performed safely in both open and laparoscopic approaches. Surgeons can interact with the findings, flushing the duct to clear stones or debris. Open and laparoscopic IOC can successfully be completed in about 95% of patients (see Chapter 34), with sensitivity for detecting CBD stones between 80% and 92% and specificity of 93% to 97% (Machi et al, 1999). Regardless, an ongoing debate remains whether IOC should be performed routinely or selectively during cholecystectomy. When used routinely, it has high sensitivity and specificity both for suspected CBD stones and for the 3% to 4% of stones that are not clinically suspected but may become symptomatic postoperatively. Other suggested benefits specifically relate to the prevention of bile duct injuries (Fletcher et al, 1999). No large prospective randomized trials that answer the question definitively, so most practicing surgeons perform IOC selectively.

Symptomatic Common Bile Duct Stones

The symptoms of CBD stones relate to partial or complete biliary obstruction with and without inflammatory complications such as cholangitis, hepatic abscesses, or pancreatitis. In chronic scenarios, and depending on the extent and duration of biliary obstruction (>5 years), choledocholithiasis may also lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension (see Chapter 35). Because of the uncertain clinical behavior and potential harmful complications, it is currently accepted that in the great majority of situations, CBD stones should be removed, even if they are asymptomatic (Williams et al, 2008).

Definitive Treatment Approaches: Biliary Obstruction

Catheter-Based Approaches (See Chapters 27, 28, and 36)

ERCP

Before the laparoscopic era, ERCP was not commonly used, because open surgical bile duct clearance was superior to ERCP in terms of success and morbidity (see Chapters 29 and 35; Martin et al, 2006). This changed as laparoscopic cholecystectomy emerged and outpaced the abilities of most surgeons to perform laparoscopic CBD stone removal. Indeed, ERCP captured and has held its role as the first-line approach to CBD stones, being successful in more than 90% of patients (Rieger & Wayand, 1995). Although well tolerated in most, a 10% rate of complications remains constant for ERCP (Andriulli et al, 2007), with a serious morbidity rate of 1.5% and an overall mortality rate of 0.2% to 0.5% (Freeman et al, 1996). When surgical and endoscopic teams are inexperienced with CBD stones, the perceived need for preoperative ERCP increases. In this setting, ERCP allows laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be performed quickly and with confidence that CBD stones are already managed. If ERCP fails, the surgical plan will need to consider intraoperative management of choledocholithiasis. Conversely, in centers where successful sphincterotomy and stone extraction is almost assured, the rate of preoperative ERCP will be lower. If the surgeon finds a stone at operation, ERCP becomes a reliable postoperative option. Current consensus accepts the use of ERCP prior to laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with a high probability of choledocholithiasis. It is recommended that patients with a low or intermediate index of suspicion for choledocholithiasis undergo additional imaging techniques (MRCP, EUS, IOC) to avoid unnecessary biliary instrumentations (Tse et al, 2004; Williams et al, 2008; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, 2010).

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography (See Chapter 28)

Compared with ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is time consuming, more involved, and likely more stressful for a patient. It is usually reserved for patients in whom anatomical considerations preclude safe ERCP, such as in the case of an impossible ampullary cannulation. Experienced PTC groups have reported successful stone removal rates in more than 90% of cases, with complication rates around 5% (Garcia-Vila et al, 2004), although these are hardly the norms. PTC stone removal takes time, involving insertions of catheters that are upsized over time, before stones are actually retrieved with stone baskets. Consequently, there are many reports of attempts to make it easier. Gil and colleagues (2000) have reported the safety and utility of balloon dilation of the papilla in the clearing of CBD stones using occlusion balloon pushing. This is also gaining popularity for the laparoscopic surgeon during IOC.

Surgical Approaches: Open and Laparoscopic Techniques (See Chapters 29 and 35)

Cholecystectomy with Intraoperative Cholangiography (See Chapters 21 and 34)

Open and laparoscopic IOC can successfully be completed in the majority of patients by the majority of surgeons (Machi et al, 1999). IOC can be performed through the direct insertion of contrast medium into the gallbladder or more often by intubating the cystic duct. Plain radiographs have largely been replaced by digital fluoroscopic imaging. IOC is common, and most surgeons receive sufficient training. Laparoscopic ultrasound cholangiography is also efficacious (Stiegmann et al, 1995) but not broadly used.

Since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the debate over routine versus selective IOC has been rekindled because of the increased incidence of CBD injuries and the inability to palpate the CBD during laparoscopy. IOC accurately defines the biliary anatomy and may protect against intraoperative bile duct injuries (Fletcher et al, 1999), or at least it reduces their severity (Woods et al, 1995). Opponents claim that routine IOC may lead to bile duct injury and unnecessary CBD explorations because of false positives and that it may add time and costs unnecessarily.

Selective IOC pivots upon predicting the probability of choledocholithiasis. In general, patients with a low probability (normal LFTs, normal CBD diameter) may undergo cholecystectomy with no further preoperative investigation and selective IOC. Patients with intermediate risk (isolated abnormal LFTs or CBD dilatation) may undergo further preoperative imaging (MRCP) and routine IOC at an absolute minimum. Patients with high risk (jaundice, cholangitis) warrant confirmatory/therapeutic ERCP (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, 2010) at most centers. In fact, today many patients are triaged for this purpose, but in years past, many would undergo open CBDE. Ultimately, the choice of modality depends on local availability and expertise in minimally invasive treatments coupled with considerations of cost and convenience.

CBDE: Transcystic versus Choledochotomy Access (See Chapters 29, 34, and 35)

When IOC reveals CBD stones, they can readily be removed during cholecystectomy. The open choledochotomy to allow cholangioscopy, flushing, forceps and balloon clearance, and T-tube placement is rarely performed or taught today. Instead, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) has evolved as an efficient, well-accepted, and broadly utilized technique as described in other chapters. Several studies have shown LCBDE to be as efficient as preoperative or postoperative ERCP in terms of stone clearance, morbidity, mortality, and short hospital stay (Martin et al, 2006; Clayton et al, 2006) and is thus recommended for surgeons with appropiate skills and facilities. Further, for capable surgeons, LCBDE is as safe and efficient as ERCP, thus avoiding the discomfort, costs, and potential complications of an extra procedure (Martin et al, 2006).

LCBDE can be safely performed through either transcystic or choledochotomy approaches. Many prefer the transcystic approach. It is feasible in most cases, saves time, does not violate the CBD, and shows no higher morbidity than standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy alone (Hanif et al, 2010; Tinoco et al, 2008). The most consistent risk factor for failing transcystic stone clearance is the size of the stone. Once stones exceed 5 mm, the likelihood of transcystic extraction falls considerably (Stromberg et al, 2008), and laparoscopic choledochotomy becomes necessary. However, many surgeons do not have the laparoscopic dissection and suturing expertise to perform this procedure; they rely instead on ERCP, or they convert to an open operation. Experienced surgeons can remove larger or multiple CBD stones with reported success rates of up to 90% (Lien et al, 2005). A 2007 Cochrane review was not able to conclude significant differences in outcomes for primary closure of the CBD versus the routine use of T-tube drainage after open CBD exploration (Gurusamy, 2009). Similar outcomes have been reported from a recent randomized clinical trial for LCBDE through choledochotomy (Zhang et al, 2009).

Gallstone Pancreatitis

Acute gallstone pancreatitis is the most frequent form of acute pancreatitis in Western countries (see Chapter 53). The two most commonly accepted mechanisms for the pathogenesis of gallstone pancreatitis are reflux of bile into the pancreatic duct and transient ampullary obstruction caused by temporary impaction of a stone in the ampulla. The disease is mild in approximately 80% of patients, but 20% experience a more severe clinical course that includes complications such as pancreatic necrosis, multisystem organ failure, and even death (see Chapter 54; Acosta et al, 1997; Alexakis et al, 2007; NIH, 2002).

In many patients, the biliary obstruction has spontaneously resolved at the time of presentation, so biliary decompression is not needed. These patients should undergo elective cholecystectomy once the pancreatitis has resolved. At the other end of the spectrum are patients with gallstone pancreatitis and associated acute cholangitis (see Chapter 43). Clear evidence shows that endoscopic biliary drainage is beneficial in patients with acute cholangitis, thus these patients should have early biliary decompression.

A secondary question is whether patients with gallstone pancreatitis, without cholangitis, benefit from biliary decompression. Clinical and experimental studies suggest that impacted ampullary stones and persistent biliopancreatic obstruction are associated with a more severe clinical course. In theory, early endoscopic removal of obstructing ampullary gallstones should improve outcomes (Acosta et al, 1997; Alexakis et al, 2007). Between the late 1970s and mid-1980s, urgent surgery with biliary decompression was studied as a treatment of choice for patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis, but this approach was associated with an increased mortality rate among patients with severe pancreatitis. As such, surgical treatment during the acute phase of the gallstone pancreatitis is not recommended.

The role of nonsurgical intervention, prior to definitive surgical therapy, has been examined in several prospective randomized studies in which patients with cholangitis were excluded. Integral to any interpretation of treatment approach is the severity of the gallstone pancreatitis. These studies defined severe pancreatitis utilizing a number of systems that included the Ranson criteria (>3), Glasgow criteria (>3), or the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (>8). The Ranson and Glasgow criteria have the advantage of ease of use and considerable areas of overlap (Table 37.3). A recent meta-analysis analyzed five prospective randomized studies that examined the use of early biliary decompression in cases of gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis (Moretti et al, 2008). This study reported a significant reduction in pancreatitis-related complications in patients with predicted severe pancreatitis (rate difference of 38.5%; 95% confidence interval, −53% to −23.9%); P < .0001); but no advantage was seen in cases with mild pancreatitis, and no difference in mortality rate was noted.

Table 37.3 Ranson and Glasgow Criteria for Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

| Criterion* | Action |

|---|---|

| Ranson | |

| Age >55 years | Admission |

| WBC count >16,000/mm3 | Admission |

| Glucose >200 mg/dL | Admission |

| AST >250 IU/L | Admission |

| LDH >350 IU/L | Admission |

| Increased BUN >8 mg/dL | 48 hr |

| Pao2 <60 mm Hg | 48 hr |

| Calcium <8.0 mg/dL | 48 hr |

| Base deficit <4 mEq/L | 48 hr |

| Fluid sequestration ≥6 L | 48 hr |

| Glasgow | |

| Age >55 years | Admission |

| WBC count >15,000/mm3 | Admission |

| Glucose >200 mg/dL | Admission |

| AST/ALT >96 IU/L | 48 hr |

| LDH >219 IU/L | 48 hr |

| BUN >45 mg/dL | Admission |

| PaO2 <76 mm Hg | Admission |

| Calcium <8.0 mg/dL | 48 hr |

| Albumin <3.4 g/dL | 48 hr |

WBC, white blood cell count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen

* Mortality rates: 0 to 2 = 2%, 3 to 4 = 15%, 5 to 6 = 40%, >7 = 100%

The severity of the patient’s illness guides the timing of intervention. Patients whose biliary obstruction has spontaneously resolved at the time of presentation and those who have mild predicted pancreatitis should have early elective cholecystectomy once their pancreatitis has resolved. Patients with severe predicted pancreatitis and those with associated cholangitis should undergo early biliary decompression (ERCP or PTC). Among cases of escalating pancreatitis, biliary decompression should be performed within 24 to 72 hours of admission (Moretti et al, 2008). For cases with associated cholangitis, biliary decompression should occur within 24 hours of presentation. Elective cholecystectomy can then be performed once the severe illness has resolved.

Cholangitis (See Chapter 43)

Clinical findings associated with acute cholangitis include RUQ abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, and chills—also known as Charcot’s triad (1877). Not all patients with cholangitis manifest all findings: 90% develop fever, but only about 50% to 70% of patients develop all three symptoms. Reynolds’ pentad (1959)—Charcot’s triad plus shock and altered mental status—represents a form of severe (grade III) cholangitis, which can also manifest with multiorgan dysfunction. Severe cholangitis is present in about 30% of patients with acute cholangitis (Gouma, 2003).

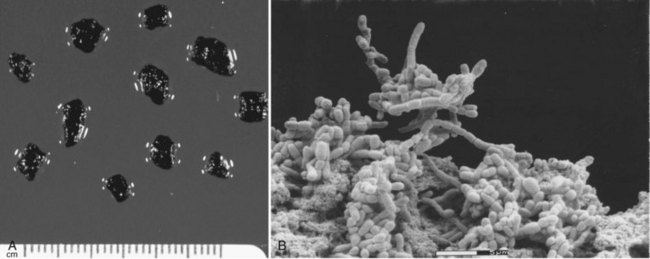

Cholangitis is a localized infection of the biliary tree, and an understanding of the pathophysiology of cholangitis guides treatment decisions. Research in this disease has shown that bacteria-laden gallstones are the source of infection. These bacteria exist in a bacterial microcolony (biofilm) within the pigmented matrix of gallstones (Fig. 37.2; Stewart et al, 2002). The bacteria must detach from the biofilm to cause a localized infection, and it must reflux into the cholangiovenous circulation to cause a more severe illness, including bacteremia and organ dysfunction (Raper et al, 1989; Stewart et al, 2003). Cholangiovenous reflux occurs with biliary pressures greater than 20 cm H2O, and even at this pressure, bacterial characteristics (slime production) influence cholangiovenous reflux (see Chapter 7). In addition, bacterial breakdown by complement releases endotoxin, and this influences the induction of inflammatory cytokines that drive the septic manifestations.

The 2006 Tokyo International Consensus Meeting described three grades of acute cholangitis (Table 37.4): grade I is mild and responds to initial medical treatment; grade II is moderate and does not respond to initial medical treatment, but it is not associated with organ dysfunction; and grade III is severe and is associated with organ dysfunction (Miura et al, 2007). All patients with suspected cholangitis should be treated with intravenous hydration and antibiotics that cover the most common biliary organisms: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterococcus, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas spp., and anaerobic pathogens. Patients with severe grade III cholangitis also require organ support and stabilization of organ dysfunction.

| Grade | Criteria |

|---|---|

| I Mild | Responds to initial medical treatment |

| II Moderate | Does not respond to the initial medical treatment but is not associated with organ dysfunction |

| III Severe | Associated dysfunction at least in one of the following organ systems:1. Cardiovascular system: hypotension requiring dopamine >5 µg/kg/min or any dose of dobutamine2. Nervous system: decreased level of consciousness3. Respiratory system: Pao2/Fio2 ratio <3004. Renal system: serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL5. Liver: PT-INR >1.56. Hematologic system: platelet count <100,000/mm3 |

PT-INR, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio

The critical component of the treatment of cholangitis is biliary decompression. Because elevated biliary pressure drives cholangiovenous reflux, decompression of the biliary tree with ERCP is crucial; PTC may be used if ERCP is not available. Not only does biliary drainage prevent bacterial cholangiovenous reflux, it has also been shown to be associated with a marked decreased in bile and serum endotoxin levels. In a prospective randomized trial, Lai and colleagues (1992) demonstrated decreased mortality associated with endoscopic drainage compared with urgent surgical intervention, 10% versus 32%, respectively. A nonrandomized study by Leese and others (1986) showed similar findings. These and other studies emphasize the need for nonsurgical decompression in the setting of severe acute cholangitis.

The Tokyo Guidelines provide a useful tool for the management of acute cholangitis (see Table 37.4). Patients with grade I cholangitis who respond to medical therapy can be treated with ERCP (within 24 hours) followed by definitive surgical treatment (laparoscopic cholecystectomy), or the surgeon can proceed to laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative LCBDE after medical stabilization (Takada et al, 2007; Miura et al, 2007). Factors guiding these choices include the patient’s clinical findings and the surgeon’s experience with LCBDE.

By definition, patients with grade II cholangitis do not respond to medical therapy, so they require urgent biliary decompression. Patients with severe (grade III) cholangitis require urgent endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage following stabilization of organ dysfunction. For patients with grade II or III cholangitis, the initial therapy should emphasize biliary decompression rather than definitive removal of all common duct stones. Prolonged procedures with excessive manipulation in an attempt to remove large stones should be avoided in patients with active infectious manifestations. Once the acute illness has resolved, early cholecystectomy can be performed within 6 weeks of biliarydecompression with no increase in postoperative complications (Li et al, 2010).

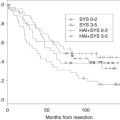

Need for Cholecystectomy After ERCP/Sphincterotomy

There has been considerable debate over whether cholecystectomy is required after ERCP/sphincterotomy for patients who initially present with choledocholithiasis. Retrospective studies have reported a low incidence of cholecystectomy among patients with a gallbladder in situ following ERCP/sphincterotomy managed by watchful waiting (10% to 15% over 5 to 14 years) (Schreurs et al, 2004; Sugiyama et al, 1998). Many of these studies involved older patient populations and patients with multiple medical illnesses. More recently, however, a Cochrane review of prospective randomized studies reported that elective cholecystectomy is recommended (McAlister et al, 2007). For five randomized trials with 662 participants, an increased mortality in the expectant group compared with the cholecystectomy group was noted, and patients in the observation group had higher rates of recurrent biliary pain, jaundice, or cholangitis and more need for repeat ERCP or cholangiography (McAlister et al, 2007).

Abboud PA, et al. Predictors of common bile duct stones prior to cholecystectomy: A meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44(4):450-455.

Acosta JM, et al. Effect of duration of ampullary gallstone obstruction on severity of lesions of acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:499-505. Erratum in: J Am Coll Surg 1997;185:423-424

Akyurek N, et al. Management of acute calculous cholecystitis in high-risk patients: Percutaneous cholecystotomy followed by early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15(6):315-320.

Albores-Saavedra J, et al. The precursor lesions of invasive gallbladder carcinoma: hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 1980;45:919-927.

Alexakis N, et al. When is pancreatitis considered to be of biliary origin and what are the implications for management? Pancreatology. 2007;7(2-3):131-141.

Andriulli A, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1781-1788.

American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice CommitteeMaple JT, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(1):1-9.

Cadot H, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysmorrhaphy and cholelithiasis in the era of endovascular surgery. Am Surg. 2002;68:839-843. discussion 843-844

Callery MP. Avoiding biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: technical considerations. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(11):1654-1658.

Clayton ES, et al. Meta-analysis of endoscopy and surgery versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones with the gallbladder in situ. Br J Surg. 2006;93(10):1185-1191.

Collins C, et al. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239(1):28-33.

Curro G, et al. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis in children with sickle cell disease. Ann Surg. 2007;245:126-129.

Daradkeh S, Shennak M, Abu-Khalaf M. Selective use of perioperative ERCP in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47(35):1213-1215.

Festi D, et al. Natural history of gallstone disease: expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroent Hepatol. 2010;25:719-724.

Fletcher DR, et al. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography—a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999;229(4):449-457.

Freeman ML, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(13):909-918.

Garrow D, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(5):616-623.

Garcia-Vila JH, Redondo-Ibanez M, Diaz-Ramon C. Balloon sphincteroplasty and transpapillary elimination of bile duct stones: 10 years’ experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(6):1451-1458.

Gil S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of balloon dilation of the papilla and the use of an occlusion balloon for clearance of bile duct calculi. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(5):1455-1460.

Gouma DJ. Management of acute cholangitis. Dig Dis. 2003;21(1):25-29.

Griniatsos J, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy without interval cholecystectomy as definitive treatment of acute cholecystitis in elderly and critically ill patients. South Med J. 2008;101:586-590.

Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, 2006: Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD005440.

Gurusamy KS, et al, 2009: Cholecystectomy for suspected gallbladder dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD007086.

Hadad SM, et al. Delay from symptom onset increases the conversion rate in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. World J Surg. 2007;31:1298-1301.

Hanif F, et al. Laparoscopic transcystic bile duct exploration: the treatment of first choice for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(7):1552-1556.

Hickman MS, Schwesinger WH, Page CP. Acute cholecystitis in the diabetic: a case-control study of outcome. Arch Surg. 1988;123:409-411.

Hirota M, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:78-82.

Howard JM, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: a safe option in the management of acute biliary sepsis in the elderly. Int J Surg. 2009;7:94-99.

Ishizaki Y, et al. Conversion of elective laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy between 1993 and 2004. Br J Surg. 2006;93(8):987-991.

Jenkins PJ, et al. Open cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era. Br J Surg. 2007;94(11):1382-1385.

Kao LS, Flowers C, Flum DR. Prophylactic cholecystectomy in transplant patients: a decision analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:965-972.

Kaufman HS, et al. The role of bacteria in gallbladder and common duct stone formation. Ann Surg. 1989;209(5):584-591.

Keus F, et al, 2006: Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev (4):CD006231.

Khan MH, et al. Frequency of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy detected by ERCP: experience at a large tertiary referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:247-252.

Klaus A, et al. Incidental cholecystectomy during laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Am Surg. 2002;68:619-623.

Koo KP, Traverso LW. Do preoperative indicators predict the presence of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg. 1996;171(5):495-499.

Lai EC, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586.

Leese T, et al. Management of acute cholangitis and the impact of endoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1986;73:1988-1992.

Li VK, Yum JL, Yeung YP. Optimal timing of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy after acute cholangitis and subsequent clearance of choledocholithiasis. Am J Surg. 2010;200(4):483-488.

Lien HH, et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with T-tube choledochotomy for the management of choledocholithiasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15(3):298-302.

Machi J, et al. Laparoscopic ultrasonography versus operative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: review of the literature and a comparison with open intraoperative ultrasonography. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(4):360-367.

Majeed AW, et al. Common duct diameter as an independent predictor of choledocholithiasis: Is it useful? Clin Radiol. 1999;54(3):170-172.

Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J, 2006: Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD003327.

McAlister VC, Davenport E, Renouf E, 2007: Cholecystectomy deferral in patients with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD006233.

McSherry CK, et al. The natural history of diagnosed gallstone disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ann Surg. 1985;202:59-63.

Miura F, et al. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):27-34.

Moretti A, et al. Is early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography useful in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:379-385.

Murison MS, Gartell PC, McGinn FP. Does selective preoperative cholangiography result in missed common bile duct stones? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1993;38(4):220-224.

National Institutes of Health. Gallstones and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. NIH Consensus Statement. 1992;10(3):1-20. Available at Online Sep 14-16 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=hsnihcdc&part=A11132

National Institutes of Health. State-of-the-science statement on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for diagnosis and therapy. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19(1):1-23.

Nguyen L, et al. Use of a predictive equation for diagnosis of acute gangrenous cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2004;188:463-466.

Petrov MS, Savides TJ. Systematic review of endoscopic ultrasonography versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for suspected choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 2009;96(9):967-974.

Raper SE, et al. Anatomic correlates of bacterial cholangiovenous reflux. Surgery. 1989;105:352-359.

Rieger R, Wayand W. Yield of prospective, noninvasive evaluation of the common bile duct combined with selective ERCP/sphincterotomy in 1390 consecutive laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(1):6-12.

Schreurs WH, et al. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones leaving the gallbladder in situ: a cohort study with long-term follow-up. Dig Surg. 2004;21(1):60-64. discussion 65

Schulman CI, et al. Are we training our residents to perform open gallbladder and common bile duct operations? J Surg Res. 2007;142(2):246-249.

Siegel JH, Kasmin FE. Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut. 1997;41:433-435.

Stewart L, Easter D, Moossa AR. Asymptomatic gallstones: nonsurgical versus surgical approach. Prob General Surg. 1989;6:73-80.

Stewart L, et al. Pathogenesis of pigment gallstones in Western societies: the central role of bacteria. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6(6):891-903. discussion 903-904

Stewart L, et al. Cholangitis: bacterial virulence factors that facilitate cholangiovenous reflux and TNFα production. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:191-199.

Stiegmann GV, et al. Laparoscopic ultrasonography as compared with static or dynamic cholangiography at laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective multicenter trial. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(12):1269-1273.

Stromberg C, Nilsson M, Leijonmarck CE. Stone clearance and risk factors for failure in laparoscopic transcystic exploration of the common bile duct. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(5):1194-1199.

Sugiyama M, Tokuhara M, Atomi Y. Is percutaneous cholecystostomy the optimal treatment for acute cholecystitis in the very elderly? World J Surg. 1998;22:459-463.

Takada T, et al. Background: Tokyo guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:1-10.

Tewari M. Contribution of silent gallstones in gallbladder cancer. J Surg Onc. 2006;93:629-632.

Tinoco R, et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Ann Surg. 2008;247(4):674-679.

Tse F, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. The elective evaluation of patients with suspected choledocholithiasis undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(3):437-448.

Tse F, et al. EUS: A meta-analysis of test performance in suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(2):235-244.

Tseng CW, et al. Can computed tomography with coronal reconstruction improve the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(10):1586-1589.

Verma D, et al. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(2):248-254.

Williams EJ, et al. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57(7):1004-1021.

Wolf AS, et al. Surgical outcomes of open cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era. Am J Surg. 2009;197(6):781-784.

Woods MS, et al. Biliary tract complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy are detected more frequently with routine intraoperative cholangiography. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(10):1076-1080.

Wudel LJ. Prevention of gallstone formation in morbidly obese patients undergoing rapid weight loss: Results of a randomized controlled pilot study. J Surg Res. 2002;102(1):50-56.

Yamashita Y, et al. Surgical treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:91-97.

Zhang WJ, et al. Laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct with primary closure versus T-tube drainage: a randomized clinical trial. J Surg Res. 2009;157(1):e1-e5.