Caring for Patients at the End of Life

Lida Nabati and Janet L. Abrahm

• Oncology clinicians must assess patients’ willingness to accept prognostic information and deliver this information clearly and truthfully.

• Patient decisions about resuscitation preferences and disease-directed therapy, including phase 1 trials, should be discussed in the context of their prognosis, values, and goals.

• A sense of purpose can be maintained by patients who work on completing legacies, reconciliation, saying goodbye, and making plans for support or care of bereaved survivors.

• Physical comfort is a prerequisite for exploring other sources of distress; consultation with anesthesia pain or palliative care specialists can be useful.

• Depression can be ameliorated even in the last weeks of life; delirium can be mistaken for pain and may be exacerbated if it is treated with increases in opioid medication alone.

• Problematic relationships can create open wounds as painful as any physical injury.

• Families with young children are in need of specialized counseling and support.

• Ongoing losses (in physical attractiveness or physical or mental function or of roles in the family, community, or workplace) contribute to spiritual and existential distress. Life reviews and reconnection with sources of spiritual support, including religious rituals, can help.

• Hospice is the gold standard of care at the end of life. Hospice teams are multidisciplinary (including a physician, nurse, social worker, chaplain, and volunteers), but the referring physician remains in charge of the plan of care. Hospice programs provide care in the home, including all medications and durable medical equipment related to the terminal diagnosis. Patients need not have signed a “do not resuscitate” order to enroll in hospice.

• Barriers to hospice referral include physician and patient reluctance to accept a terminal prognosis (i.e., less than 6 months); current inadequate reimbursement for palliative therapies; and physician, family, and patient misconceptions about entry criteria and services provided.

• The intensity of a survivor’s grief depends on the characteristics of the mourner, the nature of the death, and societal and cultural factors.

• Measures that diminish the suffering of the survivors include skillfully communicating the diagnosis and terminal prognosis; providing emotional, psychological, and spiritual support and physical comfort; helping families to resolve outstanding issues; and making the death as peaceful as possible.

• Survivors appreciate ongoing communication with the patient’s physician. The formal bereavement program that hospice programs offer takes place during the first year after the patient’s death. The program includes descriptions of typical manifestations of grieving and offers of counseling, support groups, and services of remembrance.

Introduction

For patients at the end of life, the oncologist’s care continues beyond the cessation of disease-directed therapy. When cure or even prolongation of life is no longer possible, oncologists have one last task remaining: to provide expert care to patients at the end of life and support for their families.1 Despite physical comfort, patients can experience profound suffering from any of the following causes:

• Anxiety, depression, or delirium

• Difficulty in maintaining personal dignity

• Losses of significant aspects of who they were at home, in the community, or in the workplace

• Lack of closure in important relationships

When those problems are addressed, patients have the chance to attain transcendence, a sense that who and what they have been will persist long after they have died.3,4 Through collaborations with psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, and chaplains, oncology clinicians can promote physical comfort, social functioning, and psychological and spiritual well-being.5,6 We need never say, “There is nothing more I can do.”

Patients rely on us to help them achieve a comfortable death that follows a time when goodbyes have been said, legacies have been established, affairs have been settled, and relationships have been brought to an acceptable closure. Their families need us to minimize the patient’s suffering, obtain expert palliative care consultation when needed, and communicate clearly and often with them. Currently, however, such care is the exception rather than the rule.7,8 This chapter provides an outline for oncology clinicians who wish to provide excellent care at the end of life and includes discussions of communication with patients and their families, approaches to ameliorating distress at the end of life, hospice care issues, manifestations of grief and bereavement, and suggestions for supporting bereaved survivors.

Communication Needs of Patients and Families

Timely, truthful, compassionate communication among patients with advanced cancer, their families, and their physicians is needed to dispel fears (e.g., of unrelieved pain or of abandonment), to promote feelings of autonomy and control, to set goals of care, and to enable patients and families to be prepared for what is to come. Ideally, these conversations begin at the time of diagnosis, but they are especially important as patients near the end of life, because they can significantly affect the decisions that patients make regarding their preferences for care. In one study, patients with advanced cancer were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences if they had discussed end-of-life issues with a physician.9 Another study showed that aggressive care at the end of life is associated with poorer quality of life and that patients who have end-of-life discussions with their physicians are less likely to receive aggressive care when they are dying.10

The vast majority of patients (80% to 98%) want to be able to do the following:

• Name a proxy to make health care decisions

• Know what to expect as their physical condition deteriorates

• Put their financial affairs in order

• Know that the doctor is comfortable talking about death and dying

• Feel that the family and they themselves are prepared for their death

• Have funeral arrangements in place

• Have treatment preferences, especially about resuscitation, in writing11

Families want to be able to say goodbye and be present when the death occurs, talk about their fears, and talk about the death with the clinicians.12 Bereaved survivors are more likely to have a major depressive disorder if they feel that they have not been prepared for the death.13 For patients and survivors to be prepared, physicians must be clear about the prognosis.

The cultural norms of medicine, however, favor optimism over accuracy and avoidance over confrontation in delivering a prognosis.14 Physicians might assume that patients will ask when they are ready for the information. No data are available, however, on how often patients with advanced refractory disease ask about their prognosis. Moreover, patients are known to be reticent about raising other important topics—such as uncontrolled pain or their wishes regarding resuscitation—with their physicians.15,16 Physicians might also worry that giving a truthful prognosis will eliminate hope.

Further, patients need to decide whether it still makes sense for them to undergo attempts at resuscitation. The likelihood of poor functional and cognitive outcomes affects their decisions, as does their understanding of their prognosis.17 It is important, therefore, to tell a patient who has widely metastatic cancer that attempts at resuscitation have very limited efficacy.18,19 It is optimal to include family members in these discussions (with the patient’s permission) because they, too, are usually unaware that the patient is incurable or that the patient would benefit from hospice care until they hear it directly from the physician.20 It is equally important to correct mistaken impressions of patients who really have only weeks or months to live. Patients who believe that they have a greater than 10% chance of surviving 6 months, for example, usually want to be resuscitated. Only patients who believe that they have a less than 10% chance of surviving for 6 months overwhelmingly choose comfort care and do not want to be resuscitated.21

Before sharing prognostic information, it is important to assess a patient’s willingness to accept this information. For patients who are willing to discuss prognosis, using straightforward communication strategies described in the literature can enhance the effectiveness of the communication both for the clinician and the patient and family who are receiving the bad news (Box 46-3).22 For patients who are reluctant or ambivalent, exploring their reasons for deferring the discussion and acknowledging emotions surrounding prognosis can be helpful in navigating the next best steps for communication. Negotiating a limited disclosure or disclosure to a designated proxy may ultimately be in the patient’s best interest if it is believed that prognostic information is likely to affect patient decision making.23

Shared decision making is recommended for a patient-centered approach to care.24 Communication with dying patients must also be culturally effective and extend to include psychosocial and spiritual needs, addressing loss, dignity, and the need for meaning.4,5,25,26 Clinicians who are not experienced in such conversations might find it helpful to use the questions crafted by experts in this field (Box 46-1).5,8,25,27

Distress

Dying patients might experience problems of a physical, psychological, social, or spiritual nature. These patients define quality of life at the end of life as including physical comfort, a sense of control and dignity, relieving burden on their loved ones, strengthening and completing relationships with significant others, and avoiding prolongation of the dying process.28 To provide high-quality care, therefore, oncologists need to collaborate with an interdisciplinary team such as that provided by palliative care and hospice programs. In 2006, the specialty of Hospice and Palliative Medicine was recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties, training approved by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education started in 2007, and the first certifying examination was given in 2008. The American Society of Clinical Oncology first advocated for integrating palliative care into comprehensive oncology care29 and issued a provisional clinical opinion document in 2012 reaffirming the importance of early integration of palliative care into oncology care.30 Physicians and nurses trained as palliative care practitioners address all dimensions of distress, including communication, decision making, management of complications of treatment and the disease, symptom control, psychosocial care of patients and their families, and care of the dying.8

Physical Causes

• Restlessness/agitation/delirium or noisy or moist breathing (60%)

Most of the physical problems that dying patients experience can be controlled by using a limited number of medications given by the oral, sublingual, buccal, rectal, transdermal, or, if necessary, parenteral route (Table 46-1).

Table 46-1

Treatment of Common Physical Problems in the Last Days of Life

| Problem | Agent(s) | Routes, Doses |

| Pain (continuous) | Morphine, hydromorphone | IV/SC infusion |

| Fentanyl | Transdermal | |

| Morphine, oxycodone | SL oral concentrates | |

| Pain (intermittent) | Morphine, oxycodone | SL oral concentrates |

| Fentanyl | Buccal lozenge | |

| “Death rattle” | Scopolamine | Transdermal scopolamine patch, 1-3 every 3 days |

| Hyoscyamine | 0.125-0.25 mg SL, 3-4 times daily | |

| Glycopyrrolate | 0.1-0.2 mg IV, 3-4 times daily | |

| Anxiety | Lorazepam | 0.5-2 mg SL; every 2 hours |

| Clonazepam | 0.5-2 mg twice daily PO | |

| Depression | Methylphenidate | 2.5-5 mg PO every morning or every morning and noon |

| Delirium (mild) | Haloperidol | 1-5 mg PO or PR or 0.5-3 mg SC, IV, every 2-12 hours |

| Chlorpromazine | 12.5-50 mg PO, IV, or PR every 4-8 hours | |

| Olanzapine | 2.5-5 mg PO or SL at bedtime or twice a day | |

| Dyspnea (anxiety) | Lorazepam | 1 mg SL, PO every 2 hours |

| Dyspnea (other) | Morphine | 5-10 mg PO/PR every 2 hours; 1-3 mg IV every hour |

| Chlorpromazine | 25-50 mg PO, IV, or PR every 4-12 hours | |

| Nausea | Lorazepam/metoclopramide or haloperidol | Compounded suppositories with desired agents (depending on presumed cause of nausea) every 6 hours PR |

IV, Intravenous; PO, oral; PR, per rectum; SC, subcutaneous; SL, sublingual.

Data from Abrahm JL. A physician’s guide to pain and symptom management in cancer patients. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005 and Cowan JD, Palmer TW. Practical guide to palliative sedation. Curr Oncol Rep 2002;4:242–249.

Pain Control

If oncologists use World Health Organization guidelines for cancer pain relief, 50% of their patients near death will experience no pain, 25% will experience mild to moderate pain, and only 3% will experience severe pain.32 Patients require close monitoring, and both opioids and nonopioid adjuvants are usually required. Special considerations in dosing opioids at the end of life include available routes of administration, the patient’s ability to swallow, gut function, and hepatic and renal function. For patients who are unable to take pills, buccal, sublingual, transmucosal, or rectal opioids are usually effective, although absorption of transdermal fentanyl is impaired in patients with cachcxia.33–36 Concentrated morphine or oxycodone oral solutions (20 mg/mL) can be given hourly or every 2 hours and are often satisfactory. Rectal administration of sustained-release opioid preparations is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but studies indicate that morphine absorption from a sustained-release preparation placed in the rectal vault is equivalent to that from oral administration.37 If pain is a new problem and the patient is not accustomed to taking opioids, therapy can be instituted with rectal sustained-release morphine, 15 mg every 12 hours, or with 5 to 10 mg of immediate-release oxycodone. Pain relief occurs 30 minutes to an hour after rectal administration of immediate-release oxycodone, and the pain relief lasts for 8 to 12 hours.38

Nonopioid analgesics and adjuvants can also be given rectally or subcutaneously.34 Rectal indomethacin can be administered to patients who have previously benefited from oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and patients taking a stable glucocorticoid dose for bone or nerve pain can receive subcutaneous dexamethasone or specially compounded dexamethasone suppositories. Rectal doxepin can replace oral tricyclic antidepressant agents.

Death Rattle

Pooling of secretions in the hypopharynx of dying patients causes the loud rasping sounds referred to as the “death rattle.” Patients are usually unaware of these loud respirations, but they can be very distressing for families. The patient can be repositioned to a lateral recumbent position and, if needed, one of the following agents can be administered: hyoscyamine (0.125 mg three or four times daily sublingual [Levsin SL]), glycopyrrolate (subcutaneously or intravenously 0.2 mg every 4 to 8 hours or 0.6 to 1.2 mg per day by subcutaneous or intravenous continuous infusion), or scopolamine in a transdermal patch.39

Dyspnea

The prevalence of cancer-related dyspnea in dying patients is approximately 70%.40 Dyspnea often progresses with increased intensity and is more prevalent in the last weeks of life.41 Dying patients benefit from the same symptomatic therapies that are recommended for patients with less advanced disease. Any opioid that is being used for pain control can also be used to ameliorate the patient’s dyspnea. Aggressive treatment of panic due to perceived breathlessness includes an oral or parenteral opioid (e.g., morphine 5 to 10 mg orally), rectal or parenteral chlorpromazine, or sublingual or parenteral benzodiazepines for refractory panic.

Xerostomia

Although dying patients are unlikely to be thirsty or hungry, they might complain of dry mouth, which often is caused by opioids.42 Hydration is not indicated to relieve this symptom because no difference in the reports of thirst or dry mouth has been found between dehydrated and normally hydrated dying patients, and no controlled studies have shown that artificial hydration is effective.43 Providing parenteral hydration increases distress, because it causes nausea and vomiting from increased gastric secretions; dyspnea from ascites, upper airway secretions, and pulmonary edema; and pain from ascites and peripheral edema.42 Moistening the mouth with swabs or offering sips of water, ice chips, or fruit-flavored ice usually ameliorates the xerostomia.

Psychological Causes

According to Dr. Susan Block, “grief, sadness, despair, fear, anxiety, loss and loneliness are present, at times, for nearly all patients facing the end of their lives.”44 Patients need “good communication and trust among patient, family, and clinical team, the ability to share fears and concerns, as well as meticulous attention to physical comfort and psychological and spiritual concerns.”44 The elements of a thorough psychosocial assessment (which includes “developmental issues; meaning and impact of illness; coping style; impact on sense of self; relationships; stressors; spiritual resources; economic circumstances; and the physician-patient relationship”) can be found in Dr. Block’s review.44

Anxiety

Anxiety, seen in up to 34% of patients with cancer, can arise from situational, physical, psychological, or existential factors.45,46 It can range from mild and controlled without interventions to severe and debilitating. Sepsis, hypoxia, metabolic abnormalities, withdrawal from medications (e.g., opioids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], or benzodiazepines), adverse medication effects (e.g., glucocorticoids, akathisia from antiemetic agents, or paradoxical agitation from benzodiazepines), and uncontrolled pain or delirium all can manifest as anxiety. Patients with panic disorders, agitated depression, phobias, posttraumatic stress disorders, or adjustment disorders also can present with anxiety. Chemoreceptors can be triggered by hypoxia in patients with advanced parenchymal disease, pleural effusion, pneumonia, or pulmonary edema and lead to sensation of choking, air hunger, and anxiety. Having dependent children is an independent predictor of panic in patients with advanced cancer.47

Pharmacologic treatments usually include benzodiazepines unless contraindicated (e.g., short-acting lorazepam, 0.5 to 2 mg every 2 hours as needed, or long-acting clonazepam, 0.5 to 2 mg orally twice daily) or SSRIs. Opioids with or without benzodiazepines are useful for patients whose anxiety is due to dyspnea.48 Nonpharmacologic treatments, such as cognitive behavioral interventions,49 relaxation training, hypnosis, supportive psychotherapy, and counseling, are also very effective.46

Depression

Depression is more prevalent as cancer progresses to advanced stages.50 Diagnosis of depression in patients with advanced cancer is made challenging by the prevalence of cancer-related somatic symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia. Additionally, sadness is common at the end of life and is not necessarily pathological. Patients with cancer can experience appropriate sadness in response to realization of limited life expectancy, adjustment disorders with depressed mood, or debilitating major depressive episodes. Terminally ill patients who answer “Yes” to the screening question “Are you depressed?” are likely to be diagnosed as depressed in a more comprehensive evaluation.51 Clinicians can determine whether patients are truly depressed by examining them for evidence of hopelessness, a sensation of helplessness, or guilt or reports of being a burden to caregivers. Clinicians can ask, “How do you see your future? What do you imagine is ahead for yourself with this illness? What aspects of your life do you feel most proud of? What aspects of your life do you feel most troubled by?”52 The clinician can serve as a therapeutic agent by listening actively and providing support for both the patient and the family. For patients with mild symptoms of depression, psychoeducation, supportive counseling, and encouraging peer support may be sufficient. For moderate to severely depressed patients, pharmacotherapy should be considered. Methylphenidate appears to have benefit in patients with advanced disease53 and can be effective in days. An SSRI should be considered along with the methylphenidate for patients with more extended prognoses, because the effects of the SSRI may take several weeks to appear. Tricyclic antidepressants are generally avoided in this population because of adverse effects. Mirtazapine may be helpful, particularly in patients for whom insomnia and anorexia are also concerns.54

Delirium

Delirium (hypoactive, hyperactive, or mixed) has been reported in up to 88% of dying patients.55 Hallmarks of delirium include abrupt onset and fluctuating course, impaired arousal and attention, as well as cognitive and/or perceptual impairments.56,57 Patients with hypoactive delirium might be mistaken as depressed because they can appear withdrawn, paranoid (e.g., fearing that the caregiver is trying to poison them with medications), or sad, yet careful mental status testing might demonstrate significant cognitive impairment. The Confusion Assessment Method can be a useful tool for detecting delirium and has been validated in a cancer population.58 Patients with agitated delirium may cry out, be restless, and pick at clothes or bed sheets. Some persons may interpret this behavior as indicating the presence of pain, although it is important to distinguish between pain and delirium, particularly because opioid therapy is often an etiologic factor in delirium. Patients with any type of delirium can experience insomnia and daytime somnolence, nightmares, agitation, irritability, distractibility, hypersensitivity to light and sound, anxiety, difficulty in concentrating or marshaling thoughts, fleeting illusions, hallucinations and delusions, emotional lability, attention deficits, and memory disturbances, all of which can be extremely distressing and thus warrant treatment.59

The etiology of delirium among patients with advanced cancer is often multifactorial.55 Medical causes include metabolic abnormalities (e.g., hypercalcemia, hyperglycemia, and uremia), malnutrition, dehydration, hypoxia, fever, infection, urinary retention, obstipation, uncontrolled pain, hepatic failure, primary brain tumor, and brain metastases. Medications—especially opioids, benzodiazepines, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and high-dose corticosteroids—often contribute to delirium. When opioids are implicated, opioid rotation may be indicated and may improve the delirium.60 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation can differentiate delirium from anxiety, minor depression, anger, dementia, and psychosis.59 Among patients who are very near the end of life, the burden of the evaluation might exceed the benefit of finding a specific, reversible cause. Empiric therapy that controls the delirium might suffice. If the patient lacks the ability to make decisions related to care, discussion with the patient’s surrogate decision maker can help clarify the best course of action. Treatment protocols for delirium are included in Table 46-1.

Agitation in the Dying Patient

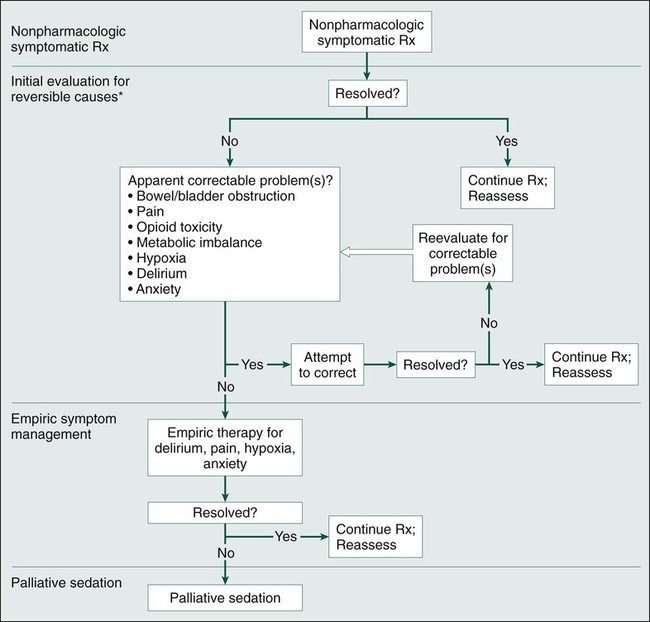

Many patients who are actively dying of cancer show signs of restlessness and agitation. They might toss and turn, moan, have muscle twitching or spasm, and be awake only intermittently. For some patients, this agitation indicates pain or delirium, but other patients may be suffering from unresolved spiritual or social problems. The approach to assessment and treatment of agitated dying patients involves, sequentially, nonpharmacologic symptomatic therapy, an evaluation for reversible causes and treating those that are found, and empiric symptom management (Fig. 46-1). Whenever a treatment resolves the agitation, it should be continued, and the patient should be reassessed. In rare cases, patients with agitation require sedation. The aggressiveness of the evaluation and the nature of the treatments that are provided should be guided by the patient’s goals and the burdens and benefits of each intervention. The site of care (i.e., hospital, nursing home, or home) need not be the deciding factor in the decision about which palliative assessment and therapies to offer.

Social Causes

Family concerns and relationship issues can weigh heavily on dying patients. Practical concerns are often the easiest to resolve, although a major concern of dying patients is the burden they feel they are imposing on their loved ones.28 They also want to strengthen and complete their relationships. For this reason, problematic relationships can create open wounds that are as painful as those from any physical injury. Dr. Ira Byock offers five simple phrases (“The Five Things”) that encompass the subjects people can benefit from discussing with those they love: “Forgive me; I forgive you; thank you; I love you; and goodbye.”3 Many patients and families find it difficult to say these phrases or discuss these subjects. Palliative care clinicians, social workers, chaplains, and psychologists can be of great help in facilitating these conversations and bringing peace to a dying patient and to the soon-to-be-bereaved family members.

• Communication with health care providers

• Help with caregiving and meeting financial and social costs

Oncology clinicians can help by simplifying medication regimens, anticipating symptoms, and planning for emergencies that can be foreseen.64 Box 46-2 provides suggestions about how oncologists can address some of the family’s needs. Social workers collaborate with the patient’s primary oncology team to provide most of the support, explain the benefits of hospice and other needed services, and arrange family access to these services.

Cultural Considerations

To avoid communication difficulties, physicians and nurses should explore with patients and families what they believe are appropriate context and structure of end-of-life discussions (Box 46-3).66 Non-Hispanic whites and African Americans, for example, differ in many areas: who they want present (immediate family only versus extended family, friends, and pastor); having durable power of attorney or a living will in place and interest in knowing about hospice programs67 (more common in non-Hispanic whites68–68); and what the focus and tempo of the discussion should be (e.g., concerns about prognosis, irreversibility of the illness, quality of life, financial concerns and medical choices versus spiritual concerns, lack of trust, concerns about “do not resuscitate” orders and hospice, allowing adequate time for decisions, and not feeling pressure to make decisions).68,69 More patients who are not of non-Hispanic white or African American descent prefer to have surrogates informed of their prognosis and make treatment decisions for them. Some patients from Asian, Bosnian, or Italian American cultures might perceive frank communication about a serious illness or prognosis as “at a minimum, disrespectful, and more significantly, inhumane.”66 It is therefore important to determine from the patient whether the patient or his or her designees are to be involved in these discussions and to respect that choice as the exercise of that patient’s autonomy. Every effort should be made to provide a medically trained interpreter in conversations about prognosis and goals of care when the clinician is not a fluent speaker of the patient’s language.66

Spiritual and Existential Causes

Dying patients also can suffer as a result of spiritual and existential concerns. When patients believe their spiritual needs are supported by their medical team, they seek less aggressive care at the end of life and have a higher quality of life.70 As cancer advances, patients face ongoing losses in terms of normal appearance and physical and mental function, roles in the family, community, or workplace, control, autonomy, and privacy.2 Suffering arises when the illness robs patients of something fundamental to who they are, and consequently, each person’s sources of suffering are unique. For example, although loss of mobility might be irrelevant to someone whose major avocation is reading, it can be devastating to an avid golfer. Young patients in particular search for the meaning in their existence, their illness, and their premature deaths. Counseling, including life reviews (“What have you been most proud of in your life? What surprised you most? What has made you happiest? What do you wish you could have done better or differently?”) may help dying patients to find a context and a meaning for their lives.

Some patients seem to blame themselves for their illness, even though scientific evidence does not support their belief. The concern could arise from a much larger sense of guilt about the patients’ sense of failure to live the lives they believe they should have lived. Other patients—those with uncontrolled pain, for example—might feel that God is testing or punishing them and search their consciences for a transgression so dreadful that it deserved such punishment.71 A mental health professional or chaplain might be able to provide reassurance or help patients develop strategies to right the wrongs they believe they caused. Even dying patients can be provided hope that in the absence of a cure, they will still be able to heal these wounds.

Religious rituals can be an important source of comfort and healing to dying patients and their families.71 Even in a hospital setting, therefore, every effort should be made to identify and accommodate these spiritual practices. Appropriate hospital or community religious leaders should be welcomed as part of the patient’s care team and should be assisted in performing the necessary rites before and after the patient dies.

Palliative Sedation for Refractory Symptoms

Palliative sedation is considered when, despite expert evaluation and management, a patient who is near death continues to experience intolerable physical, psychological, or spiritual-existential distress.72 Fewer than 5% of patients need palliative sedation; those who do most commonly suffer from refractory pain, cough, dyspnea, seizures, or delirium. Expert palliative care and pastoral consultation, evaluation by a psychiatrist, and discussions among the health care team, the patient, and the family members should be undertaken before palliative sedation is administered. Most often, all the people concerned reach a consensus on the need for and acceptability of sedation as a means of achieving symptom control. Obtaining formal informed consent, either from the patient or surrogate decision maker, is necessary.

Medications that are used to produce the sedation that relieves the distressing symptom(s) include opioids, neuroleptics, intravenous benzodiazepines, and subcutaneous or intravenous barbiturates. A systematic review demonstrated no decrease in survival from the implementation of palliative sedation.73 Intravenous hydration or enteral or parenteral nutrition are rarely used in imminently dying patients whether or not the patients are sedated, because these patients are rarely experiencing hunger or thirst.42

Hospice Care

In 2010, approximately one million patients died while receiving hospice care, and roughly one third of persons admitted to hospice had a cancer diagnosis.74 Hospice care allows many patients to fulfill their desire to die at home, although hospice care can be provided in other settings. Hospice can be an enormous source of comfort to families of dying patients and professional caregivers, particularly those who have never witnessed a “natural” death. The team members have “been there,” can explain what is likely to happen, and can provide expert symptom management for hours, days, weeks, and months. One study demonstrated prolonged survival in patients enrolled in hospice,75 and hospice care might also decrease the risk of death of surviving spouses.76,77

American patients are generally very resistant to accepting a terminal prognosis.78,79 To enroll in hospice, patients must acknowledge their 6-month prognosis, forego curative therapy, and give informed consent. To acknowledge a prognosis estimate, this estimate must first be conveyed by the clinician. Many barriers prevent communication of this information. These requirements, common misconceptions about hospice care (Box 46-4), and clinician-related factors (e.g., reluctance to prognosticate, overestimating prognosis, and delayed or late referrals) can be serious obstacles to enrollment in hospice programs.80

Clinical Care Provided

Patients in hospice programs are cared for by medically directed, interdisciplinary teams that include the referring physician, the hospice medical director, a nursing director of patient services, an office administrator, a nurse, a social worker, a bereavement counselor, a home health aide, a chaplain, and volunteers. The core team also can request additional consultations from physicians, registered dietitians, or occupational, speech, or physical therapists (Box 46-5).

Medications and Treatments Provided

Hospice programs provide 95% of the cost of prescription drugs related to the terminal diagnosis and necessary for its palliative treatment (and many programs waive the other 5% if the patient has no insurance coverage). Hospice programs also provide all durable medical equipment, supplies, and oxygen for needs related to the terminal diagnosis; laboratory and diagnostic procedures related to the terminal diagnosis; and transportation when medically necessary for changes in the patient’s level of care (see Box 46-5).

Financial Considerations

The hospice benefit (under Medicare) is a managed care, capped reimbursement program that reimburses a hospice program a per-diem rate based on the patient’s level of care (approximately $147 per day for routine or respite care and approximately $650 per day for inpatient acute care).81 Given this reimbursement schedule, aggressive palliation using chemotherapy or radiation is often prohibitively expensive for small to moderate-size hospices. Individual hospices must decide both which treatments are consistent with their philosophy and which they can afford. Most hospices must secure additional funding from grants and donations to provide the mandated services. Many more hospices are declaring an “open access” policy, allowing patients who otherwise meet eligibility criteria to enroll in hospice and continue with costly therapies such as parenteral nutrition and palliative radiation.82

Grief and Bereavement

Grief and bereavement are integral to the cancer experience and should be a priority for the care of patients with cancer. Grief is a “process of experiencing the psychological, behavioral, social, and physical reactions to the perception of loss,” and it is distinguishable from the anxiety and depression that survivors might also be experiencing.83,84 The intensity of a survivor’s grief is based on the characteristics of the mourner himself or herself, the nature of the death, and societal and cultural factors. Rando83 writes that being very attached to or very dependent on the deceased, having a great deal of ambivalence in one’s feelings toward the deceased, having a personal history of clinical depression, or having difficulty with previous losses all can exacerbate the grief. Studies have confirmed the association between attachment and dependence and severity of grief but also found that having more ambivalence predicted for less grief.85 Sudden or accidental death, suicide, or homicide magnify the grief.83 The perception of a violent death is associated with major depression in the survivors, but religious rituals, a good support system, and involvement with hospice programs for more than 3 days decrease depression.86,87

Each bereaved person’s loss is unique, as are the experiences and manifestations of grief and mourning. Many people manifest typical symptoms of grief, some of which become less persistent as the people rebuild their lives.83,84,88,89 Recurrent intense symptoms typically occur at the anniversary of the death of the patient but can occur at unpredictable times, sparked by any type of reminder of the deceased. Although there are no rigid stages through which bereaved survivors pass, some manifestations of grief are typical.

At the time of death, survivors often appear numb, confused, or dazed and usually express some form of denial as the reality of the death intensifies.90 Behavior can range from uncontrolled shrieking to an unnerving calm. In the weeks and months that follow, pain intensifies as the absence of the person who has died asserts itself repeatedly. Mourners yearn for the one who is dead and experience repeated pangs of intense grief; denial is replaced by disorganization, depression, disinterest, and despair.89 Survivors commonly experience the feelings, behaviors, physical symptoms, spiritual concerns, and thoughts listed in Box 46-6.

Often by a year or two after the loss, survivors accommodate to it.83 They tacitly acknowledge the changes that must be made if they are ever to resume old relationships and responsibilities or establish new ones and risk recurrent loss. Accommodation involves realizing that loving someone new need not mean betraying the memory of the person who has died.83

About 10% to 20% of survivors, however, suffer either from depression and/or from “prolonged grief disorder.” Patients with depression have “symptoms of sadness, impassivity, and psychomotor retardation,”91 but they do not yearn for the deceased and they can accept the death. Depressed survivors benefit from counseling and consideration of pharmacologic treatment.91,92 Patients with prolonged grief disorder, in contrast, have grief that causes serious functional impairments. They experience profound yearning for the deceased, as well as “numbness, feeling that part of oneself has died, assuming symptoms of the deceased, disbelief, or bitterness.”91,93 These patients are at increased risk of medical and psychiatric illness94 and should be referred for psychiatric or spiritual counseling. Survivors with a history of attachment disorders (e.g., childhood abuse or childhood separation anxiety) or an aversion to lifestyle changes and who are unprepared for the death and are not supported after it are at higher risk of experiencing “prolonged grief disorder.” Additional risks include a “dependent, close, confiding” relationship with the deceased.91 No randomized controlled trial of a pharmacotherapy agent that is effective for extreme grief symptoms has been conducted,90,91 but a new effective type of psychotherapy has been developed specifically for this persons with this disorder that is superior to standard interpersonal psychotherapy.95

Skillful communication regarding end-of-life care and the provision of emotional, psychological, and spiritual support and physical comfort, as well as helping families to resolve outstanding issues, can help make the death as peaceful as possible and diminish the suffering of the survivors.10 Survivors who feel unprepared for the patient’s death have a higher risk of experiencing prolonged grief disorder.86

After the patient dies, survivors appreciate ongoing communication with the patient’s physician.92 When a formal bereavement program is offered, such as through hospice programs, it usually takes place during the first year after the patient’s death. After the formal program ends, the bereaved are encouraged to continue to participate in any bereavement activities that have been meaningful to them (Box 46-7). Survivors who experience severe grief symptoms or depression should be referred for formal assessment and consideration of pharmacologic treatment.92,96 Unfortunately, although the depression often responds to standard therapy, there is no widely accepted effective therapy for the symptoms of extreme grief.96

The care of patients with cancer can take a significant emotional toll on their clinicians. Oncologists face mortality and suffering on a daily basis. They work long hours and often feel unprepared to have difficult conversations and to deal with the emotional content that emerges from them. They are at risk of burnout.97,98 It is important for oncology clinicians to take time to grieve their losses so they can remain compassionate. Acknowledging and honoring the deceased with condolences letters or phone calls or by attending funeral and memorial services allows clinicians to process their grief. These activities also can serve as an opportunity to remain in contact with the bereaved and identify those who may benefit from referral for bereavement services.