Cancers of the Cervix, Vulva, and Vagina

Anuja Jhingran, Anthony H. Russell, Michael V. Seiden, Linda R. Duska, Anne Kathryn Goodman, Susanna I. Lee, Subba R. Digumarthy and Arlan F. Fuller, Jr.

Cervix Cancer

Epidemiology

Although cervical cancer is the third most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, it ranks as the most common gynecologic malignancy worldwide and is the third most common cancer in women in the world, with an estimated 530,000 cases in 2008. Marked disparity in incidence exists between countries where routine gynecologic care and Pap smear screening are available, and countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa, where cervical cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death in women.1

Molecular epidemiological studies have demonstrated that correlation of sexual activity with cervical carcinoma is related to transmission of the epithelial trophic and oncogenic HPV.4–4 Most HPV infections are transient, resulting in no changes or low-grade intraepithelial lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] 1) that will be spontaneously cleared in most young women.5,6 Development of high-grade intraepithelial lesions will occur in a small minority of women, usually within 24 months.7 High-grade lesions (CIN 2/3) may progress to invasive cervical cancer if not treated.8,9

Cases of CIN 2/3 that progress to invasive cancer will do so over a period of 8 to 12 years, which has been referred to as the detectable preclinical phase.10–13 Thus the opportunities for early detection and intervention are abundant. However, an estimated one half of the invasive cervical cancers diagnosed in the United States are found in women who have never been screened, and an additional 10% are diagnosed in women who have not been screened within the preceding 5 years.14

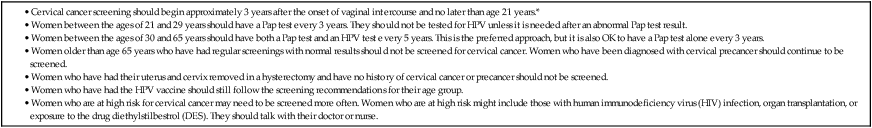

Based on a comprehensive review of available evidence, the American Cancer Society released new screening recommendations for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer on March 12, 2012. Table 87-1 is a synopsis of their recommendations.15 The biggest change from the past is that Pap tests are no longer recommended every year and there are two types of test that are used for cervical cancer screening. The Pap test can find early cell changes and treat them before they become cancer. The HPV test finds certain infections that can lead to cell changes and cancer. The HPV test may be used along with a Pap test or to help doctors decide how to treat women who have an abnormal Pap test.

Table 87-1

American Cancer Society Guidelines for Screening by Cytology for the Early Detection of Cervical Neoplasia and Cancer

Human Papillomavirus Biology

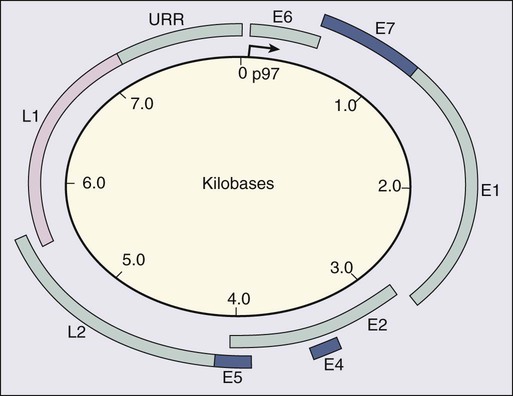

HPV is a double-stranded DNA virus in the Papovaviridae family (Fig. 87-1). This virus, made up of approximately 8000 nucleotides, encodes seven early genes and two late genes, as well as having a small, untranslated region. Approximately 100 different serotypes with limited DNA homology have been identified. Although the identification of high-risk subtypes of HPV has been important in defining potential therapeutic targets for the prevention of cervical carcinoma, HPV infection has not adequately explained all of the biological features of preinvasive disease and progression to invasive disease. Studies in sexually active college women demonstrated that infection with HPV is extremely common, occurring in up to 50% of women who become sexually active between the ages of 16 and 21 years, with the first abnormal Pap smear appearing in only a subset of women 1 year after infection. These infections typically are associated with low-grade dysplastic lesions and usually are transient. Persistent infection with associated high-grade dysplastic lesions is seen in only a small proportion of infected women (perhaps 1% or 2%). Biological and/or immunologic cofactors that allow the persistence of HPV infection in a small subset of women remain unclear. Epidemiological studies suggest that coinfection with herpes simplex virus type II, long-term oral contraceptive use, cigarette smoking, and high parity may increase the risk of persistent infection, carcinoma in situ (CIS), and invasive disease.16,17 Although long-term epidemiological studies undertaken since appreciation of the role of HPV remain incomplete, it is known that in the large majority of women, the period between HPV infection, dysplasia, and then invasive carcinoma typically is years to decades, offering the potential for screening and early intervention to change the natural history and morbidity associated with this disease.18–22

Molecular epidemiological studies have divided HPV serotypes into high-, intermediate-, and low-risk subtypes for the development of cervical neoplasia.23 Low-risk subtypes are associated with venereal warts (condylomata acuminata), whereas intermediate- and high-risk subtypes are associated with cervical dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. Recent worldwide review of HPV typing demonstrated that 87% of squamous cell carcinomas had an identifiable HPV genome associated with the tumor as compared with 76.4% of adenocarcinomas. HPV-16 was the predominant type, associated with between 46% and 63% of the squamous carcinomas, whereas HPV-18 was associated with 10% to 14% of squamous cell carcinomas. Sixteen other HPV types were associated with the remaining 25% of cases, including HPV-45, -31, and -33. Most epidemiological studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of HPV-18 (37% to 41%), followed by HPV-16 (26% to 36%) in women with adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Several authors have shown a positive association between the presence of certain HPV subtypes and prognosis. Barnes and colleagues24 showed that, among invasive carcinomas, HPV-18 is associated with poorly differentiated histology and higher incidence of nodal metastases. Similarly, Walker25 reported that HPV-18–associated cancers were more likely to recur than were HPV-16–associated cancers. By contrast, HPV-16 was associated with large cell-keratinizing tumors, and these tumors were less likely to recur.26 Lombard27 demonstrated HPV-18–associated tumors to have a relative risk of death 2.4 times greater than that observed for patients with HPV-16–associated tumors and 4.4 times greater than that for patients with a tumor associated with another HPV type.

In a recent randomized, placebo-controlled study, the delivery of three vaccinations at day 0, month 2, and month 6 reduced the risk of persistent new HPV-16 infection from 3.8 cases per 100 women-years at risk to 0 per 100 woman-years in the group that were vaccinated, for a 100% efficacy rate. In this study, involving 2392 young women between the ages of 16 and 23 years, nine cases of HPV-16–related CIN were noted, all in the placebo recipients.28 The HPV vaccine with just HPV-16 and another double-variant vaccine are now commercially available and are recommended for both girls and boys from the ages of 9 through 31 years. The use of the vaccine worldwide should help eliminate cervical and head and neck cancers caused by HPV-16.

Maiman, Fruchter, and associates29–32 investigated the disease characteristics, recurrence risks, and survival rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive patients with CIN and invasive cervical cancer. HIV-infected women had significantly higher rates of recurrence of CIN after standard therapies than did seronegative women. HIV-infected women with cervical cancer had significantly more advanced disease than did those who were not infected. Only 3 (19%) of 16 HIV-seropositive patients were first seen with an early-stage disease (defined as stage Ia or nonbulky Ib) compared with 35 (52%) of 68 in the HIV-seronegative group. When upstaged based on surgicopathological findings, only one (6%) HIV-infected patient had early-stage disease compared with 40% of uninfected patients. The response to therapy and prognosis was poorer among HIV-seropositive women, with higher recurrence and death rates. The majority of seropositive women had lymph node metastases and high-grade tumors. They generally were asymptomatic with respect to their HIV disease, but died of cervical cancer. The significant impact of immune status on disease progression was made evident by prolonged disease-free follow-up in seropositive patients with CD4 counts greater than 500/mm3, in contrast to those with CD4 counts less than 500/mm3. The observed marked increased risk of invasive cervical carcinoma in women infected with the HIV virus and the demonstration that highly effective antiretroviral therapy is capable of doubling the CIN regression rates in women infected with HIV, as compared with those women not receiving highly effective antiretroviral therapy, provides suggestive, indirect clinical evidence supporting the critical importance of the intact immune system in limiting the progression of HPV infection to invasive cancer in healthier populations.

Pathology

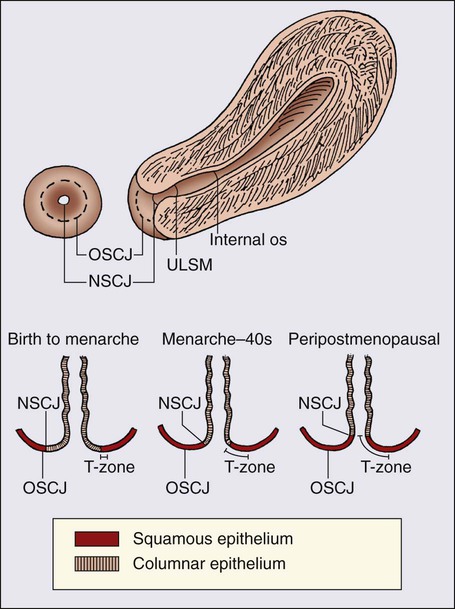

The epithelium of the cervix is composed of squamous epithelium that covers the exocervix and glands and columnar epithelial cells that line the endocervix. The border between the squamous and columnar epithelium is called the squamocolumnar junction, the site of ongoing squamous metaplasia believed to be most vulnerable to viral neoplastic transformation. With increasing age, the squamocolumnar junction migrates from the exocervix into the distal endocervical canal (Fig. 87-2), with the region between the original and subsequent locations termed the transformation zone. The transformation zone is the most common location for detection of early cervical cancers (Fig. 87-3). Tumors arising on the ectocervix typically are squamous cell carcinomas, whereas adenocarcinomas are more likely to have their epicenter in the endocervix.

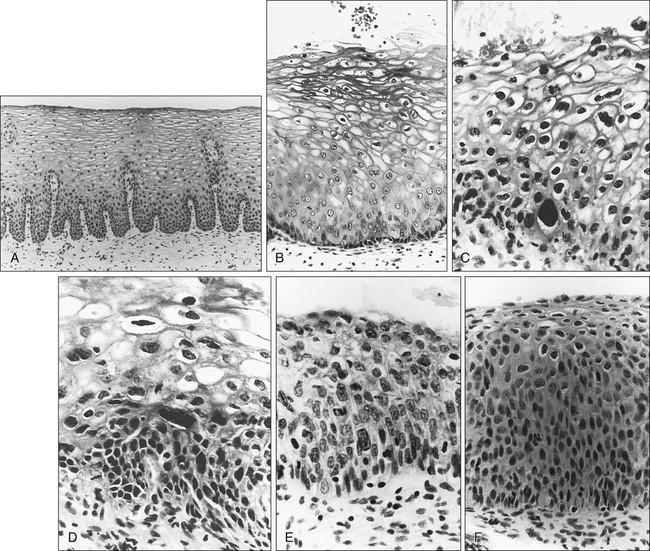

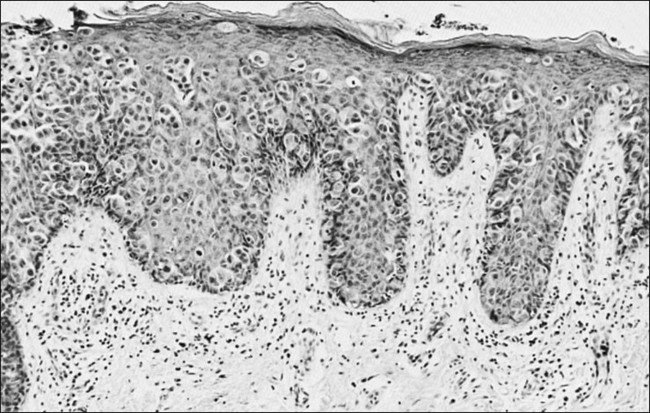

A continuum appears to exist from CIN to frankly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 87-4). The mean age of women with CIN is 15.6 years younger than that of women with invasive cancer, suggesting slow progression of CIN to invasive carcinoma.18 The natural history of HPV infection and CIN in part reflects the host immune system response to the virus. Seventy-five percent of CIN 1 lesions will spontaneously regress or persist as CIN 1, without progression to invasive carcinoma.18–21

Miller22 reported, in a 13-year observational study, that only 14% of CIN 3 lesions had progressed, whereas 61% persisted, and the remainder disappeared. Patients taking corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs and patients with HIV infection are at higher risk of progressing to invasive cancer and may have a shorter transit time for this progression.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Cervix

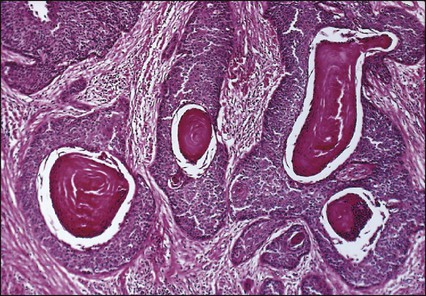

Approximately 75% of invasive cervical carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas. Tumor histology differs between well, moderately, or poorly differentiated tumors. Squamous carcinomas (Fig. 87-5) may be keratinizing (sometimes containing characteristic keratin pearls) or nonkeratinizing. Large cell and small cell variants exist. True verrucous cancers of the cervix are rare.

Cervical Adenocarcinomas

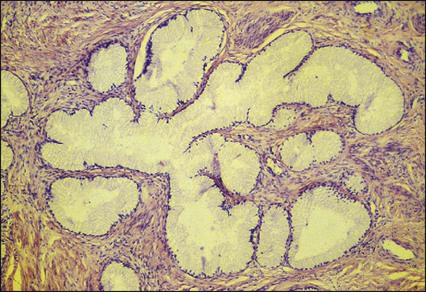

Clinically important subtypes also include clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix associated with in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure, which tend to be diagnosed at a younger age than most other adenocarcinomas, and so-called adenomalignum or minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (Fig. 87-6), an entity associated with deceptively bland or benign-appearing cells, which may be cause for undertreatment of a true malignancy, with a significant likelihood of recurrence even when diagnosed at an early stage.33,34

Adenosquamous Carcinomas

Adenosquamous carcinomas consist of a malignant glandular component and a malignant squamous component and make up approximately one-third of cervical carcinomas with glandular differentiation. Opinions vary regarding the prognosis of adenosquamous carcinoma compared with pure adenocarcinoma or pure squamous carcinoma when prognosis is adjusted for clinical stage at diagnosis. A clinically important variant of adenosquamous carcinoma is the so-called glassy cell carcinoma, thought to represent a very poorly differentiated adenosquamous carcinoma, the name of which derives from the ground-glass or granular appearance of the cytoplasm seen in many cases. Additional features may include an intense stromal inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of eosinophils and plasma cells. Some patients may have accompanying eosinophilia in their circulating blood, with elevated absolute eosinophil counts. This histologic type is associated with a rapid clinical rate of growth, proclivity for early regional dissemination, and increased risk of recurrence after surgical therapy or radiation therapy, even in the absence of other recognized adverse prognostic factors.35–38

Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Cervix

Neuroendocrine tumors in the cervix include typical and atypical carcinoid tumors, and large cell, small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and undifferentiated small cell carcinoma. Both large cell and small cell neuroendocrine tumors resemble similar carcinomas arising in the lung and other aerodigestive sites.39,40 Undifferentiated small cell carcinoma is a very poorly differentiated carcinoma with neuroendocrine features, histologically similar to anaplastic small cell carcinoma of the lung.41 Neuroendocrine carcinomas tend to behave very aggressively, with frequent widespread metastasis to multiple sites, including bone, liver, and skin. Brain metastases may occur when disease is advanced but usually are preceded by lung metastases.43 Efforts to treat these tumors by using approaches typically used for small cell carcinomas of the lung have had mixed results.42

Screening

Screening for cervical cancer and its precursors with the Pap smear and pelvic examination has resulted in dramatic reductions in cervical cancer mortality in every country where this has been widely used, and is arguably the most effective screening program in effect for any neoplastic disease, in either gender. Table 87-1 outlines the current screening guidelines of the American Cancer Society. The false-negative rate of the Pap smear is approximately 10% to 15% in women with invasive cancer, but the sensitivity, as defined by the detection of biopsy-proven CIN, is 51%.45–45 The sensitivity of the test may be improved by ensuring adequate sampling of the squamocolumnar junction and the endocervical canal. Smears without endocervical or metaplastic cells may be inadequate and possibly should be repeated.46

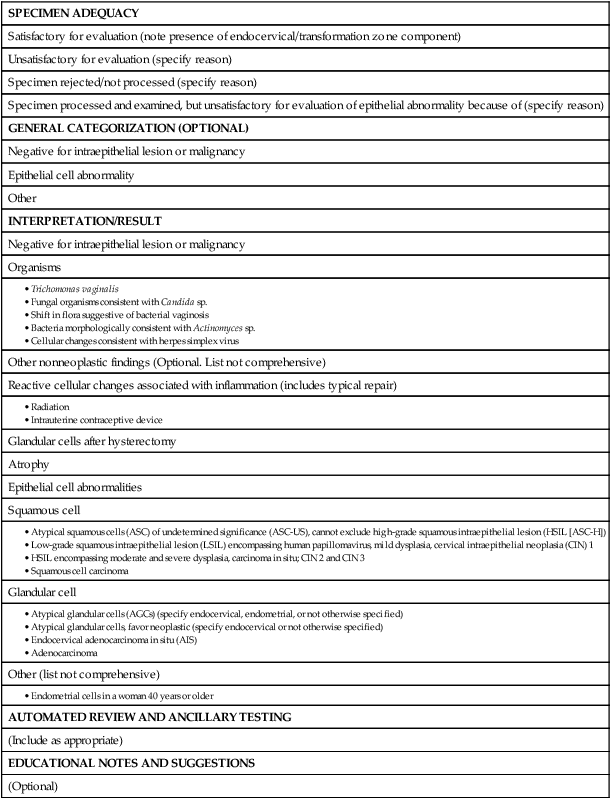

In the 1980s, cytology laboratories began reporting an increasing number of smears with changes of “squamous atypia” in response to concerns from clinicians over an unacceptably high false-negative cytology rate and increased recognition by cytopathologists of the cytologic changes associated with HPV infection. The use of multiple classification systems with inconsistently defined numeric grading conventions added further imprecision. In an attempt to eliminate confusion among clinicians and cytopathologists, a uniform system for reporting epithelial cell abnormalities was established in 1988 at a National Cancer Institute (NCI) workshop for reporting cervical and vaginal cytologic diagnoses.47

The Bethesda System has since been revised, in 1991 and again in 2001 (Table 87-2),48 to reflect laboratory and clinical experience gained since the original implementation, as well as the increased use of new technologies and results from interval research studies. An important contribution of the Bethesda System was the creation of a standardized format and nomenclature for cytology laboratory reports that includes both a descriptive diagnosis and an evaluation of specimen adequacy.

Table 87-2

| SPECIMEN ADEQUACY |

| Satisfactory for evaluation (note presence of endocervical/transformation zone component) |

| Unsatisfactory for evaluation (specify reason) |

| Specimen rejected/not processed (specify reason) |

| Specimen processed and examined, but unsatisfactory for evaluation of epithelial abnormality because of (specify reason) |

| GENERAL CATEGORIZATION (OPTIONAL) |

| Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy |

| Epithelial cell abnormality |

| Other |

| INTERPRETATION/RESULT |

| Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy |

| Organisms |

• Atypical squamous cells (ASC) of undetermined significance (ASC-US), cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL [ASC-H])

• Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) encompassing human papillomavirus, mild dysplasia, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1

• HSIL encompassing moderate and severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ; CIN 2 and CIN 3

Adapted from Soloman D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 2002;287:2114.

Diagnosis

Management of the patient with an abnormal Pap smear with respect to further diagnostic assessments, therapeutic intervention, and subsequent surveillance follow-up is a complex arena in which guidelines continue to evolve. The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) has developed contemporary guidelines for management of cervical cytologic abnormalities and CIN based on current reporting terminology (Bethesda 2001).49,50 Techniques for further evaluation can include colposcopy, endocervical curettage or brushing, and cervical conization by cold knife or loop electrodiathermy excision procedure (LEEP).

Testing for high-risk, oncogenic HPV DNA51–57 synchronously, or subsequent to cytologic screening, is proving to be a useful complementary tool in triage of patients with ASC-US smears, and in determining the need for colposcopy and the intervals for repeated screening. It may be helpful in the follow-up of younger patients with LSIL smears, and a useful tool in identifying older women who can safely be screened at 3-year intervals instead of annually.

HPV triage of patients with an ASC-US smear is at least as sensitive as immediate colposcopy for ultimately detecting CIN 3 and results in referral of about half as many women to colposcopy. A follow-up strategy that uses repeated cytology is sensitive at an ASC-US referral threshold, but requires two follow-up visits and, ultimately, more colposcopic examinations than does HPV triage.58

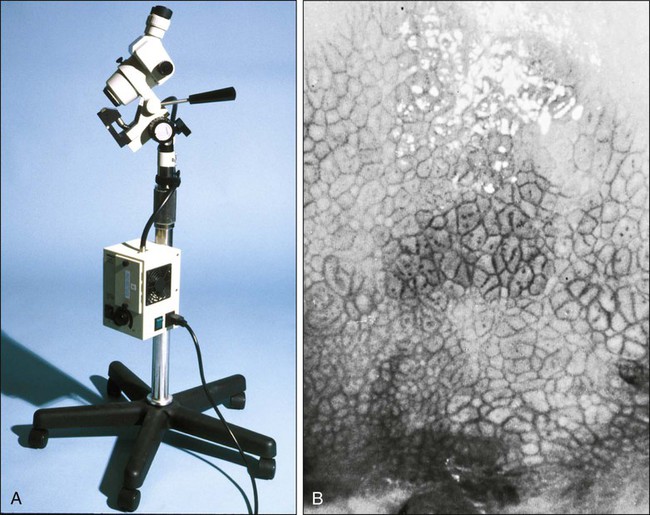

Colposcopy

Patients with a gross lesion of the cervix should undergo cervical biopsy. For patients with an abnormal cytologic evaluation, without a gross lesion, a colposcopic examination with directed punch biopsies is required. Colposcopy allows the clinician to identify areas suggestive of dysplasia. A 3% acetic acid solution is applied to the cervix for 30 to 90 seconds, which causes a transient reaction with the envelope proteins of the papillomavirus, in addition to producing an osmotic dehydration of the dysplastic cells, thereby accentuating the optically dense chromatin to produce a whitish area. The skilled colposcopist can further distinguish between grades of dysplasia based on acetowhitening and types of vascular patterns (Fig. 87-7). An additional technique to help visualize abnormal areas is the application of quarter-strength Lugol iodine after the initial inspection for acetowhitening. High-grade lesions turn mustard yellow.

Endocervical Curettage or Endocervical Brush

Study of the endocervical canal is required when no abnormalities are found on colposcopic examination, when the entire squamocolumnar junction cannot be visualized, or when atypical endocervical cells are present on Pap smear. Some experts advocate the use of endocervical curettage (ECC) as part of every colposcopic examination to safeguard against missing occult cancer within the endocervical canal. Others reserve ECC for patients with recurrent cytologic atypia after therapy. A sleeved endocervical brush is an alternative to ECC that is less uncomfortable for many patients. A recent, prospective comparison of ECC specimens with sleeved endocervical brush specimens (both obtained from the same patient sequentially after randomization with respect to the order of obtaining specimens) before cervical conization or hysterectomy revealed a higher rate of inadequate specimens from ECC, comparability of the two techniques with respect to sensitivity and specificity in unmatched analysis, and superior sensitivity of the sleeved endocervical brush in matched analysis. As the sleeved endocervical brush is at least isoeffective and possibly better than ECC but more comfortable for the patient, many clinicians prefer this maneuver, which may serve to increase patient compliance with subsequent surveillance follow-up and repeated assessment.59

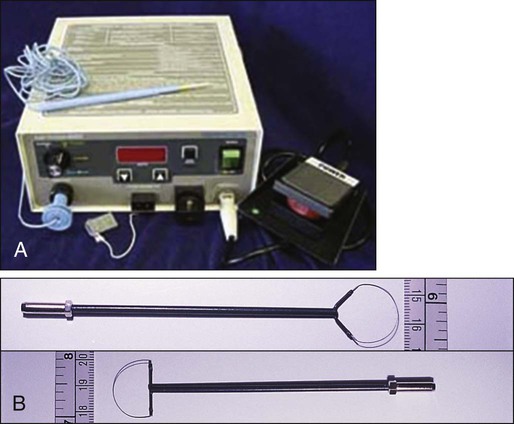

Loop Electrodiathermy Excision Procedure

LEEP uses wire-loop electrodes in conjunction with a radiofrequency alternating current to excise the entire transformation zone and distal canal under local anesthesia (Fig. 87-8). Compared with ablative procedures, LEEP has the major advantage of obtaining tissue for histologic evaluation. At many centers, LEEP has become the preferred treatment for CIN that can be assessed adequately with colposcopy.60–72

Complications include bleeding, with a reported incidence of 1% to 8%,73,74 cervical stenosis (1%), and, rarely, pelvic cellulitis or adnexal abscess. In some cases, LEEP may not be an adequate alternative to formal excisional conization, such as in those patients in whom microinvasive or invasive cancer is suspected, or in those with adenocarcinoma in situ, because it may treat disease within the cervical canal inadequately and complicate pathological interpretation of the specimen. Appropriate application of this technique will yield tissue suitable for pathological study and reliable diagnosis. Excess heat may result in thermal artifact that can compromise interpretation of margins and the therapeutic adequacy of the LEEP procedure.

Diagnostic or Therapeutic Excisional Conization (Cone Biopsy)

Diagnostic or therapeutic excisional conization (cone biopsy) must be performed under general or regional anesthesia. Complications, which include hemorrhage, sepsis, infertility, stenosis, and cervical incompetence, occur in 2% to 12% of patients, depending on depth and geometry of excision.75–75 Width and depth of the cone should be tailored to the topography of the lesion, to produce the least amount of injury while providing clear surgical margins. Conization may be performed with a cold knife or with the carbon dioxide laser.

Staging

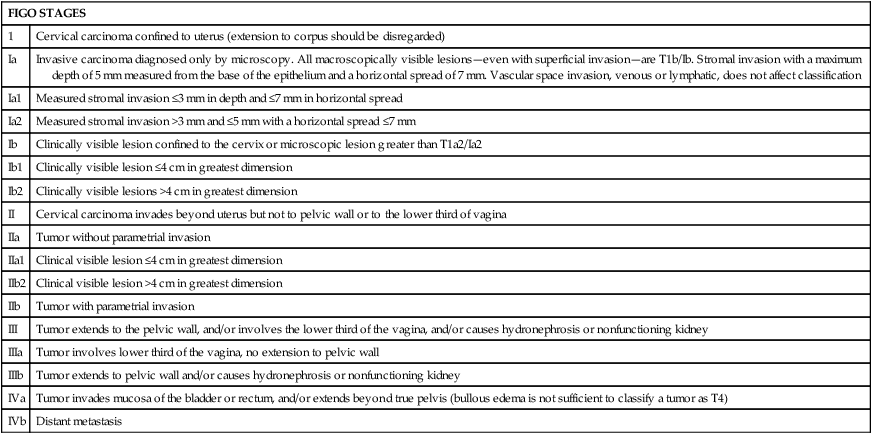

The revised 2009 staging criteria (Table 87-3)76 of the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) are a mixture of histopathological, clinical, and radiographic assessments that reflect the fact that invasive cervical cancer is most prevalent in less-developed portions of the globe where sophisticated and expensive imaging modalities may not be widely available. Cervical cancer is clinically staged, and staging is based primarily on inspection and palpation of the cervix, vagina, parametrium, and pelvic sidewalls. Only the subclassification of stage I (Ia1, Ia2) requires pathological assessment. The FIGO staging system permits assessment through biopsy, physical examination, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, excretory urography (intravenous pyelography), and plain film radiography of the chest and skeletal system. Results of lymphangiography, computed tomography (CT), MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET) may be of great value in planning treatment, but do not influence assignment of clinical stage in the FIGO formalism. When findings are equivocal, by convention, a patient is assigned to a lower stage. Once clinical stage has been assigned, it cannot be altered by subsequent events or findings. Findings from surgical evaluation (by laparoscopy or by surgical assessment of retroperitoneal lymph nodes via extraperitoneal or transperitoneal node dissection) will not alter assignment of clinical stage. However, these findings may profoundly influence subsequent treatment. Similarly, evidence of nodal or other spread discerned at the time of hysterectomy does not alter clinical stage.

Table 87-3

FIGO 2009 Staging for Cervical Cancer

| FIGO STAGES | |

| 1 | Cervical carcinoma confined to uterus (extension to corpus should be disregarded) |

| Ia | Invasive carcinoma diagnosed only by microscopy. All macroscopically visible lesions—even with superficial invasion—are T1b/Ib. Stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5 mm measured from the base of the epithelium and a horizontal spread of 7 mm. Vascular space invasion, venous or lymphatic, does not affect classification |

| Ia1 | Measured stromal invasion ≤3 mm in depth and ≤7 mm in horizontal spread |

| Ia2 | Measured stromal invasion >3 mm and ≤5 mm with a horizontal spread ≤7 mm |

| Ib | Clinically visible lesion confined to the cervix or microscopic lesion greater than T1a2/Ia2 |

| Ib1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4 cm in greatest dimension |

| Ib2 | Clinically visible lesions >4 cm in greatest dimension |

| II | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond uterus but not to pelvic wall or to the lower third of vagina |

| IIa | Tumor without parametrial invasion |

| IIa1 | Clinical visible lesion ≤4 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIb2 | Clinical visible lesion >4 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIb | Tumor with parametrial invasion |

| III | Tumor extends to the pelvic wall, and/or involves the lower third of the vagina, and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| IIIa | Tumor involves lower third of the vagina, no extension to pelvic wall |

| IIIb | Tumor extends to pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| IVa | Tumor invades mucosa of the bladder or rectum, and/or extends beyond true pelvis (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4) |

| IVb | Distant metastasis |

Diagnostic Imaging Evaluation of Cervical Cancer

The FIGO staging system is based predominantly on clinical examination under anesthesia, ultrasonography, intravenous urography, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, and chest radiography. Significant inaccuracies occur in this staging because of possible errors in gynecologic examination (24% to 39%).77 The various imaging modalities have a complementary role in the accurate staging and complete evaluation of the cancer that have important therapeutic implications.

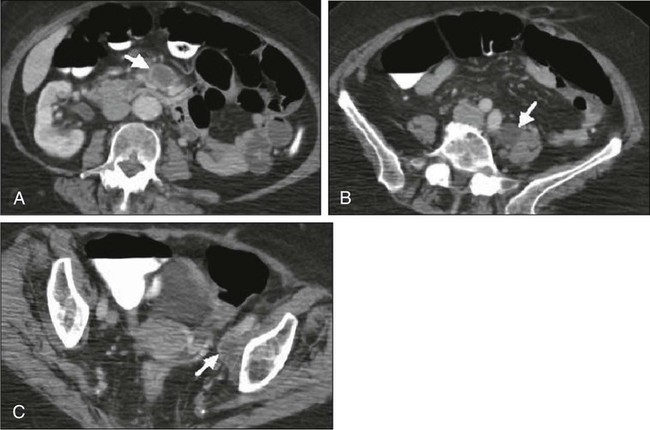

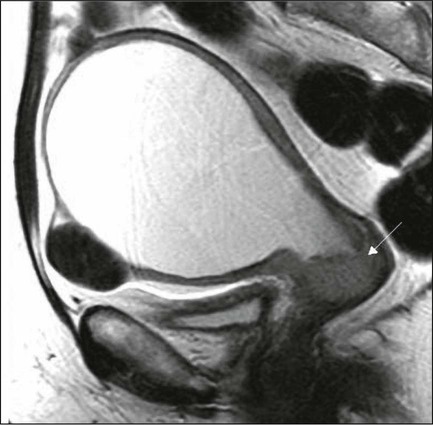

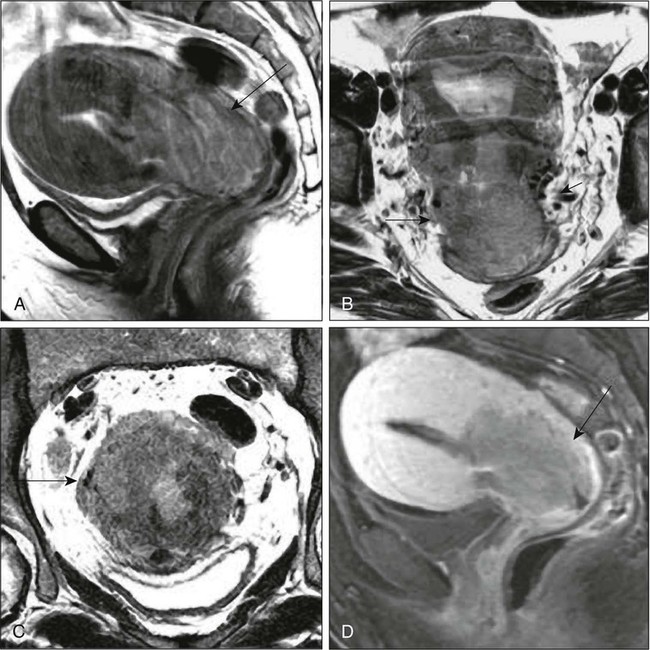

Today, clinicians most often obtain a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis for patients with disease of stage Ib2 or greater (Fig. 87-9).78 Lymph nodes larger than 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter are suspicious for tumor involvement and should be biopsied. Unfortunately, microscopic metastases are not readily detected with CT, and the inflammation commonly associated with advanced disease may cause enlargement of nodes that do not contain metastases. The sensitivity of MRI in the detection of regional metastases is similar to that of CT. However, MRI provides better anatomic delineation and accurate estimation of the tumor size, volume, and local extent within the pelvis, which can influence the choice of therapy (Fig. 87-10). Involvement of the vagina, parametrium, pelvic wall muscles, ureter, bladder, and rectum can be better assessed with MRI for accurate staging (Fig. 87-11).77 MRI before and after vaginal opacification with contrast medium can be used if imaging evaluation of the vaginal wall or fornices is required.79 T2-weighted images obtained by using phased-array coil, fast spin-echo or conventional spin-echo techniques are accurate in local staging and lymph nodal assessment; the former technique is faster with increased resolution.80 Dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images are helpful in identifying smaller tumors, fistulous tracts, and invasion into bladder and rectum.77 Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging is useful in differentiating areas composed predominantly of tumor cells (well-enhanced areas) from those of fibrous tissue with scattered cancer cells (poorly enhanced areas). This information can be helpful, as radiation therapy is more effective in well-enhanced tumors.81

MRI is very useful in the evaluation of tumor volume and enlarged lymph nodes, inherently important prognostic factors as well as determinants of the design of radiation treatment ports and selection of radiation dose. However, MRI cannot identify micrometastases to lymph nodes and differentiate malignant from nonmalignant enlargement. MRI with newer contrast agents like ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide has been useful in distinguishing benign from malignant nodes.82 The shape, volume, and direction of the growth of the tumor can be well assessed, and these are crucial for planning brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy.77 MRI also is useful in the follow-up evaluation of the tumor, its response to treatment, and identification of recurrences. However, benign conditions, like edema or inflammation, sometimes cannot be differentiated from tumors. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is useful in differentiating malignant lesions that usually have shorter and stronger enhancement than benign conditions in patients who have abnormalities after treatment for cervical cancer.83

Recent studies have suggested that 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET) is more sensitive and specific than more standard radiographic studies in the detection of lymph node involvement by cervical cancer.86–86 Grigsby and colleagues87 have reported a strong correlation between abnormal posttherapy FDG uptake and tumor recurrence. PET scans are now Medicare approved and considered standard of care for staging purposes for all newly diagnosed cervical carcinomas.

Laboratory Evaluation

Routine laboratory assessment should include complete blood counts with differential counts and red cell indices. Many patients with advanced disease will be anemic at the time of diagnosis, often reflecting chronic blood loss and iron deficiency. Anemic patients treated with radiation or chemoradiation have poorer outcomes than do patients with near-normal hemoglobin levels.88–91 Anemia at diagnosis (before treatment) correlates significantly with reduced pelvic control and survival with univariate analysis, but not always when data are subjected to multivariate analysis. In contrast, multivariate analysis reveals that hemoglobin level during the course of radiation therapy or chemoradiation is a robust predictor of local outcome and survival.88–91 Transfusion for anemic patients with maintenance of average weekly nadir hemoglobin levels at or above 11 to 12 g/dL through radiation therapy is associated with improvement in prognosis to that associated with patients with near-normal or normal hemoglobin levels at diagnosis.88,90 This effect may be partially mediated through better tumor oxygenation and oxygen-enhanced radiation lethality to clonogenic cells, as well as reduced angiogenesis in better-oxygenated tumors. With pelvic or extended-field radiation that will encompass a substantial percentage of adult bone marrow, hemoglobin may decline slowly, even when adequate iron stores are present and patients are supported with hematinics. Concurrent administration of cisplatin further aggravates this problem, and can result in clinically significant reduction in hemoglobin levels over the course of a 6- to 8-week program of chemoradiation, even in patients with normal hemoglobin levels at the time of diagnosis. Frequent monitoring of hemoglobin levels as well as white cell counts and platelets should be performed throughout a course of chemoradiation, and hemoglobin level should be supported, either by transfusion or through the use of recombinant erythropoietin. The minimal hemoglobin level required is uncertain, but it seems prudent to target a minimum of 10 g/dL.

Neutropenia may indicate supportive treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to avoid prolonged treatment interruptions that are known to adversely affect local tumor control in patients treated with radiation.92,93 Absolute neutrophil counts should be monitored at least weekly in patients undergoing chemoradiation.

An elevated platelet count has been associated with advanced malignancy and is considered a consequence of increased platelet production.94 Hernandez and associates95 identified this effect in advanced cervical cancer, and Rodriguez and coworkers96 identified the preoperative platelet count as an adverse prognostic factor, even for patients with stage Ib cervical carcinoma. The cumulative 5-year survival of women with a platelet count greater than 300,000 (85 women) was 65%, compared with 84% for the group with a normal value (134 women). At issue was the question of whether the value could have been elevated simply because of bleeding from the primary tumor, but no association was found with the preoperative hematocrit. This study of surgically treated patients with early disease also demonstrated that the effect was not a consequence of metastatic disease and did correlate with tumor volume, with nearly half of the patients with platelet counts in excess of 300,000 having “large” lesion size, in contrast to only 28% (32 of 114) patients with normal counts.97 In a multivariate analysis, adjusting for age, race, tumor size, and presence of lymph node metastases, high platelet count was still associated with an adverse prognosis.

Prognostic Factors

Prognostic factors fall into two groups: tumor-related factors and patient-related factors. Probably the most important tumor-related factor is tumor size, and this is true both for patients treated with hysterectomy97,98 and for patients treated with radiation therapy.101–101 In fact, FIGO, in 1995, divided stage Ib into two groups according to size; other stage categories act, in part, as surrogates for tumor size. For patients treated with surgery, histologic evidence of extracervical spread is associated with a poorer prognosis. Parametrial extension is associated with a higher rate of lymph node involvement, local recurrence and death from cancer.102,103 Uterine body involvement is associated with an increased rate of distant metastases in patients treated with radiation therapy or surgery.104,105

Lymph node involvement is another important tumor-related factor. After radical hysterectomy, reported-year survival rates usually are about 35% to 40% lower when the pelvic lymph nodes are involved.106,107 However, studies suggest that postoperative chemoradiation improves these results.108 Several reports suggest that survival decreases with increasing size of the largest involved nodes,109,110 increasing number of nodes involved,106,110,111 and the increasing level of regional involvement and with extent of central disease in the cervix. Overall, the survival rates for patients with positive paraaortic nodes are about half those of patients who have similar stages of disease without paraaortic lymph node involvment.114–114 Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) also is correlated with an increased risk of recurrence. This reflects, in part, the strong correlation between LVSI and lymph node involvement; however, in a large number of postoperative studies, LVSI is an independent predictor of prognosis.107,115–117

Investigators have compared the outcome of patients with adenocarcinomas with squamous carcinomas and have reached varying conclusions about the relative prognoses of the two histologic types of cervical cancer.120–120 In a review of 1767 patients with stage Ib disease (229 with adenocarcinoma), Eifel and colleagues121 found that patients with adenocarcinoma had a significantly higher risk of recurrence and death from disease, independent of age, tumor size, or tumor morphology. The rate of distant metastasis for patients with bulky (>4 cm) adenocarcinomas was almost twice that for patients with squamous carcinoma (37% vs. 21%, P < 0.01). Several investigators have reported high recurrence rates after radical hysterectomy for adenocarcinomas. In a subset analysis of a randomized Gynecologic Oncology Group study, Rotman and associates122 reported a high recurrence rate (11 of 25 patients [44%]) after treatment with radical hysterectomy alone for adeno-adenosquamous carcinomas of the cervix; in contrast, only 3 of 31 patients (10%) who received postoperative radiation therapy had recurrences. However, all of these comparisons had a relatively small number of patients treated with cervical adenocarcinomas.

Other tumor factors include correlation between the serum concentration of squamous cell carcinoma antigen and the extent of squamous carcinoma of the cervix.125–125 Increased tumor vascularity has been associated with a relatively poor prognosis,126,127 and a strong inflammatory response in the cervical stroma tends to predict a good outcome.126 Some authors have reported a correlation between HPV subtype and prognosis.27 Several investigators have reported a higher recurrence rate in patients with histologically negative lymph nodes when a polymerase chain reaction assay of the lymph nodes was strongly positive for HPV DNA.128,129 Other authors have correlated poor prognosis with the presence of HPV messenger RNA128 or HPV-related proteins130 in the peripheral blood of cervical cancer patients.

Patient-related factors have been discussed elsewhere in this chapter and include age, hemoglobin, platelet counts, race, and smoking.131 Several studies have demonstrated that in the United States, women of color with invasive cervical cancer present with higher-stage disease134–134 and lower hemoglobin levels135,136 than do white women. Differences in socioeconomic status may influence minority patients’ access to care and ability to comply with treatment recommendations.136 In a study of 1304 women treated with radiation for cervical cancer, Kucera and colleagues131 reported that smokers with cervical cancer had a poorer 5-year survival rate than nonsmokers. This difference was statistically significant for patients with stage III disease (5-year survival rate 20.3% vs. 33.9%, P < 0.01). However, the authors did not analyze the possible influence of smoking-related deaths from causes other than cervical cancer.

Treatment Overview

Patients with large FIGO stage IIa or with stages IIb through IVa disease usually are managed with chemoradiation. Some patients with an incomplete response to chemoradiation may benefit from a combined approach using adjunctive hysterectomy to clear persistent central disease after chemoradiation. Patients with bulky Ib2 or IIa disease and rare patients with bulky central stage IIb lesions with minimal, medial parametrial invasion may be considered for this approach. For patients in whom disease recurs centrally in the pelvis after maximal chemoradiation, radical exenterative surgery can be performed, provided that no distant disease is present. Optimal candidates have mobile central disease without lymph node involvement.139–139 Intraoperative radiation therapy may be part of salvage surgery when lateral or posterior surgical margins will be predictably inadequate.140,141 Recurrent disease after initial radical surgery historically has been treated with salvage radiation, but currently should be treated with chemoradiation.142

Hysterectomy

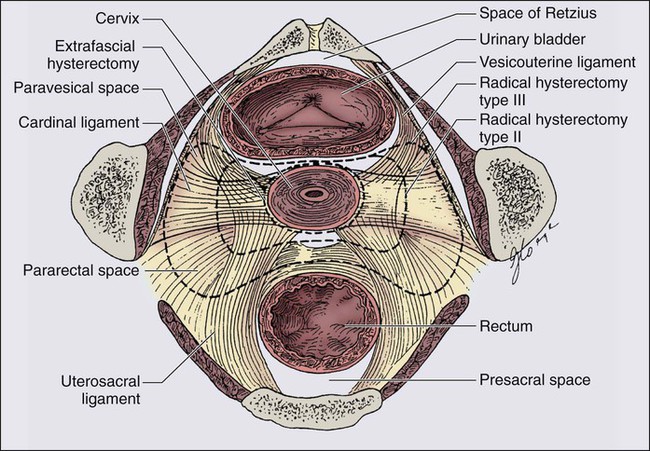

Hysterectomy involves the removal of the uterus and varying amounts of surrounding tissue (Fig. 87-12). Because the risk of ovarian metastases is low (0.5%), ovarian preservation usually is recommended in premenopausal women, obviating the need for hormone replacement therapy.143 An important exception is when nodal metastases from a primary cervical adenocarcinoma are detected intraoperatively, when the risk of ovarian metastasis escalates steeply, perhaps to as high as 25%.144 Five types of hysterectomy have been described.145

Surgical Alternatives to Conventional Radical Abdominal Hysterectomy

Laparoscopy/robot have been coordinated with vaginal hysterectomy, with varying amounts of surgery being carried out via the laparoscopic or robotic approach, ranging from pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy to lymphadenectomy plus important components of the radical hysterectomy.148–148

Radical trachelectomy is an operation suitable for selected patients with small, generally exophytic squamous tumors (usually <2 cm, although some patients with larger tumors have been treated in this fashion) involving primarily the cervix who desire conservation of reproductive capacity. In this surgery, the main trunk of the uterine artery is preserved, although branches to the cervix and vaginal fornices are sacrificed before amputation of the cervix at a point approximately 5 mm caudal to the uterine isthmus. The uterus is suspended from the lateral stumps of the transected paracervical ligaments. Isthmic cerclage is performed in a fashion similar to that used as prophylaxis against miscarriage, and an anastomosis between the vaginal mucosa and the isthmic mucosa is performed. Variations on this surgery can be performed vaginally with laparoscopy, or abdominally. The margin between the superior extent of the tumor and the uterine isthmus must be a minimum of 1.5 cm, but 2 cm is preferable. MRI can be used preoperatively to assist in patient selection for this procedure. Intraoperative assessment by inspection of the trachelectomy specimen and frozen-section pathological study are done to ensure an adequate surgical margin, and patients must be prepared for hysterectomy in the eventuality that a satisfactory margin cannot be obtained. Numerous successful pregnancies have been reported after such surgery, although the risk of miscarriage is increased. In carefully selected patients, the risk of cancer recurrence is very small.151–151

Damage to the pelvic autonomic nerves during radical hysterectomy is responsible for much of the late morbidity after surgical treatment of FIGO stages Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer, including problems with bladder function, defecation, and sexual dysfunction. Nerve-sparing radical abdominal hysterectomy152 endeavors to spare important components of the autonomic innervation of the true pelvis by identification and preservation of the hypogastric nerves, which carry sympathetic fibers; the inferior hypogastric plexus formed from the fusion of the hypogastric nerves with fibers of the pelvic splanchnic nerves derived from sacral roots S2 to S4, which carry parasympathetic fibers; and the most distal part of the hypogastric plexus, which extends to the lateral vaginal wall and the base of the bladder. In aggregate, these structures are important in controlling bladder compliance, urinary continence, vaginal lubrication and genital engorgement during sexual arousal, small muscle contractions with orgasm, and some rectal functions. This recent surgical innovation is intended not to compromise the efficacy of the cancer surgery, while preserving important components of quality of life in cancer survivors. Precise criteria for patient selection have not been defined.

Radiation Therapy

Patients with very-small-volume cervical tumors of stages Ia1 to Ib1 (Ib1, <1 cm in diameter) can be treated successfully with intracavitary brachytherapy alone, with results that parallel the efficacy of surgery.153 Brachytherapy alone, particularly if conducted on an outpatient basis with high-dose-rate (HDR) technology, may serve as suitable alternative therapy for medically compromised patients for whom operative intervention implies more than minimal risk of intraoperative or perioperative morbidity. At the other end of the spectrum of invasive disease, patients with very extensive stage III or IVa cervical cancer may not have geometry compatible with brachytherapy, and cure sometimes may be accomplished with teletherapy administered alone (or, more commonly, in combination with chemotherapy) by using progressively smaller teletherapy treatment volumes carried to progressively higher cumulative radiation dose (“shrinking fields technique”). However, radiation-based therapy with curative intent is accomplished for most patients with a combination of external beam (teletherapy) and intracavitary or interstitial isotope therapy (brachytherapy).

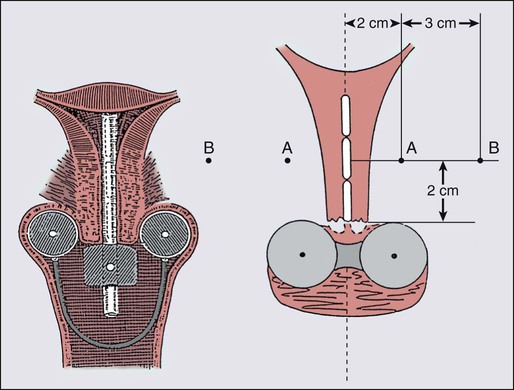

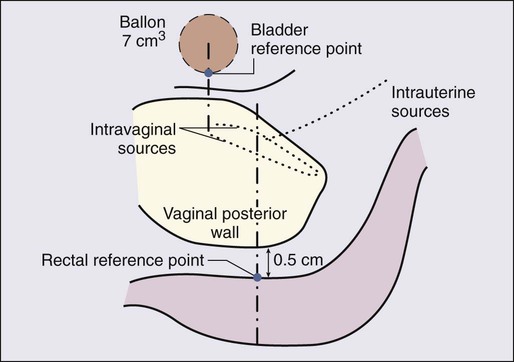

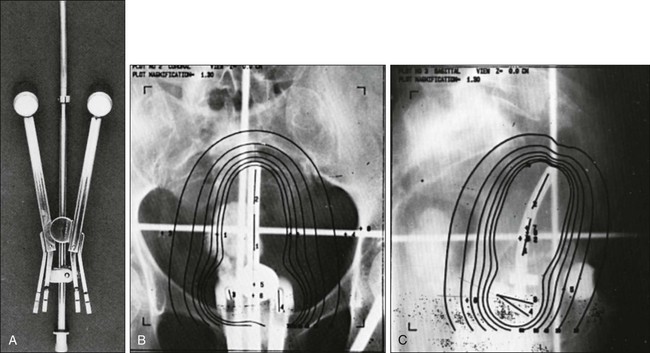

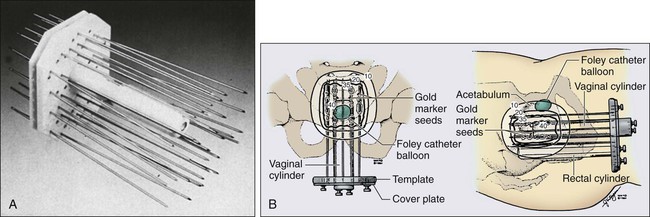

The brachytherapy dose conventionally has been calculated and prescribed at points A and B (Fig. 87-13). Doses to the bladder neck and anterior rectal wall (dose-limiting normal structures) usually are specified as well (Fig. 87-14).154 Brachytherapy usually is accomplished by using one or two intracavitary or interstitial inpatient applications of low-dose-rate (LDR) (40 to 60 cGy/h) technologies. Most applicators for intracavitary brachytherapy resemble the apparatus in Figure 87-15, and consist of intrauterine tandem and paired colpostats or ovoids, which are placed in the lateral vaginal fornices, resulting in a classic pear-shaped isodose distribution. The customary strategy is intracavitary brachytherapy supplemented by tailored teletherapy treatment to boost volumes, generally lateral and posterior to the cervix and medial parametria. In patients whose vaginal anatomy does not accommodate tandem and colpostat devices (a so-called conical vagina with flush or ablated fornices and a narrowed upper vagina) or patients with extensive, lateral parametrial invasion, interstitial implantation may provide more satisfactory dose distribution when gross tumor extends beyond the traditional pear-shaped dose envelope provided by intracavitary brachytherapy (Fig. 87-16). Interstitial templates have been used to treat cervical cancer for many years; however, reported series have been small, and patient follow-up rarely has been sufficient to permit calculation of long-term survival rates.157–157 One of the largest series is from University of California–Irvine, where they described 5-year survival rates of 21% and 29%, respectively, for patients with stage IIB and IIIB disease with high complication rates.158 At present, there is no definite evidence to indicate that interstitial therapy improves the outcome of patients with advanced intact cervical lesions.

LDR brachytherapy procedures require insertion under anesthesia and hospitalization for radiation safety and patient immobilization. Alternatively, multiple outpatient intracavitary insertions may be performed by using HDR (100 cGy/min) remote afterloading technology. Most commonly, five intracavitary insertions are performed when HDR technology is used. Because of miniaturization of the high-activity source and the hardware used for treatment, these insertions may be accomplished under conscious sedation when cooperative patients with favorable vaginal anatomy are selected. More tailored dose distributions often can be designed with the inherently more flexible HDR systems than with historically used LDR equipment using multiple sources with fixed physical dimensions and a limited spectrum of source strengths. The comparative data that exist suggest that HDR and LDR technologies are approximately isoeffective for tumor control and roughly equivalent with respect to complications when appropriate dose-rate corrections have been applied.159,160

It seems increasingly clear that either approach (LDR or HDR brachytherapy) in the hands of physicians with substantial brachytherapy experience is likely to be superior to the other approach in the hands of the clinician who treats only a limited number of patients. Brachytherapy often has been described as an art and not a science. The American Brachytherapy Society is attempting to place brachytherapy on a more rational, scientific basis by developing guidelines grounded in established practice and data driven to replace what has often been based on subjective criteria and intuition coupled with the hard lessons of experience.161,162 Improvements in diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT, PET, and combination, hybrid, or fusion studies) are anticipated to facilitate these efforts by providing improved understanding of the spatial relations of brachytherapy sources and both cancer and dose-limiting normal tissues. This effort, however, remains a work in progress.

Chemoradiation

Multiple clinical trials have investigated the sequential use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed up by conventional radical radiation therapy for patients.163–166 In several of these studies, patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed up by radiation had worse survival probability than did patients treated with radiation alone. This has been attributed to selection of cross-resistant tumor clonogens, as well as delay in initiation of the potentially curative therapy.

In dramatic contrast to the manifest failure of sequential chemotherapy and radiation, the large majority of prospective, randomized controlled trials investigating radiation and synchronous chemotherapy have demonstrated improvements in both local control and survival. Data from five phase III randomized clinical trials sponsored by the NCI have shown that the addition of concurrent cisplatin-containing chemotherapy to radiation results in a reduction in risk of recurrence by 21%.108,167–170 Four of these trials pertained to women with locally advanced cervical cancer, stages Ib2 to IVa. The fifth studied high-risk postoperative patients stages Ib to IIa with cancer extension to parametrium, surgical margins, or regional lymph nodes.

The optimal drug regimen is uncertain. Four of these trials had an experimental arm containing 5-fluorouracil (5-FU); however, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) prospectively compared weekly cisplatin with continuous-infusion 5-FU at 225 mg/m2 for 5 days weekly (a lower daily dose than the 1000 mg/m2 per 24 hours for 96 hours used in the previous positive studies) and terminated the study (GOG protocol 165) when it became clear that no possibility existed that the 5-FU arm might ultimately prove superior. Weekly cisplatin at a dose of 40 mg/m2 for 6 doses has become the most commonly used regimen for concurrent chemotherapy with radiation for advanced cervical cancer. The National Cancer Institute of Canada prospectively compared radiation alone with radiation plus weekly cisplatin in 259 patients with squamous cancers with bulky (≥5 cm) stage Ib2 to IIa, or smaller tumors with positive nodes, and patients with stages IIb to IVa cancers.171 The study was designed to have an 80% probability of detecting a 15% survival difference at 5 years. Although patients receiving the cisplatin regimen did marginally better, the study failed to find a statistically significant difference.171 The NCI made a clinical announcement in 1999, after the 5 trials from the United States, that “strong consideration should be given to the incorporation of concurrent chemotherapy with radiation therapy for patients who require radiation therapy for the management of cervical cancer.”172

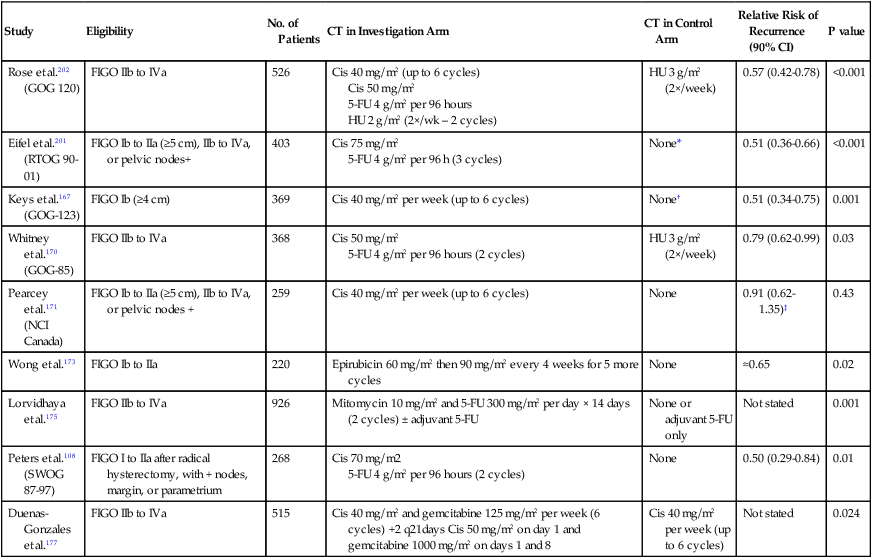

The NCI announcement was further confirmed by three additional prospective, randomized studies that found relapse-free survival benefit from the synchronous administration of epirubicin with radiation,173 mitomycin-C with radiation,174 and 5-FU plus mitomycin-C with radiation175 (Table 87-4). A meta-analysis was done to assess the effect of chemoradiotherapy on outcome in patients with local advanced cervical cancer.176 In the meta-analysis, based on 13 randomized trials, they found a 6% improvement in 5-year survival with chemoradiotherapy. A larger advantage was seen in stages I and II disease compared with stage III disease. They found a significant survival benefit in both groups of trials that used platinum-based (P = 0.017) and non–platinum-based (P = 0.009). Interestingly, there was a larger survival benefit seen in the two trials that used adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to concurrent chemoradiation therapy and the conclusion of the meta-analysis was that the results endorsed the recommendation of the NCI. However, both platinum-based and non–platinum-based chemoradiotherapy could be used.176

Table 87-4

Prospective Randomized Trials that Investigated the Role of Concurrent Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Patients with Locoregional Advanced Cervical Cancer

| Study | Eligibility | No. of Patients | CT in Investigation Arm | CT in Control Arm | Relative Risk of Recurrence (90% CI) | P value |

| Rose et al.202 (GOG 120) | FIGO IIb to IVa | 526 | Cis 40 mg/m2 (up to 6 cycles) Cis 50 mg/m2 5-FU 4 g/m2 per 96 hours HU 2 g/m2 (2×/wk – 2 cycles) |

HU 3 g/m2 (2×/week) | 0.57 (0.42-0.78) | <0.001 |

| Eifel et al.201 (RTOG 90-01) | FIGO Ib to IIa (≥5 cm), IIb to IVa, or pelvic nodes+ | 403 | Cis 75 mg/m2 5-FU 4 g/m2 per 96 h (3 cycles) |

None* | 0.51 (0.36-0.66) | <0.001 |

| Keys et al.167 (GOG-123) | FIGO Ib (≥4 cm) | 369 | Cis 40 mg/m2 per week (up to 6 cycles) | None† | 0.51 (0.34-0.75) | 0.001 |

| Whitney et al.170 (GOG-85) | FIGO IIb to IVa | 368 | Cis 50 mg/m2 5-FU 4 g/m2 per 96 hours (2 cycles) |

HU 3 g/m2 (2×/week) | 0.79 (0.62-0.99) | 0.03 |

| Pearcey et al.171 (NCI Canada) | FIGO Ib to IIa (≥5 cm), IIb to IVa, or pelvic nodes + | 259 | Cis 40 mg/m2 per week (up to 6 cycles) | None | 0.91 (0.62-1.35)‡ | 0.43 |

| Wong et al.173 | FIGO Ib to IIa | 220 | Epirubicin 60 mg/m2 then 90 mg/m2 every 4 weeks for 5 more cycles | None | ≈0.65 | 0.02 |

| Lorvidhaya et al.175 | FIGO IIb to IVa | 926 | Mitomycin 10 mg/m2 and 5-FU 300 mg/m2 per day × 14 days (2 cycles) ± adjuvant 5-FU | None or adjuvant 5-FU only | Not stated | 0.001 |

| Peters et al.108 (SWOG 87-97) | FIGO I to IIa after radical hysterectomy, with + nodes, margin, or parametrium | 268 | Cis 70 mg/m2 5-FU 4 g/m2 per 96 hours (2 cycles) |

None | 0.50 (0.29-0.84) | 0.01 |

| Duenas-Gonzales et al.177 | FIGO IIb to IVa | 515 | Cis 40 mg/m2 and gemcitabine 125 mg/m2 per week (6 cycles) +2 q21days Cis 50 mg/m2 on day 1 and gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 | Cis 40 mg/m2 per week (up to 6 cycles) | Not stated | 0.024 |

*Patients in the control arm had prophylactic paraaortic irradiation.

†All patients had extrafascial hysterectomy after radiation therapy.

Modified from Cox JD, Ang KK. Radiation oncology, rationale, technique and results. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. p. 748.

The most recent study evaluating concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy, published in 2010, was conducted in eight developing world countries and was completed in less than 2 years.177 This was a phase III randomized study evaluating standard concurrent weekly cisplatin and pelvic irradiation compared to weekly cisplatin and gemcitabine and pelvic radiation therapy followed by two additional courses of adjuvant gemcitabine+cisplatin. The authors reported a 9% improvement in progression-free survival associated with the experimental arm of gemcitabine+cisplatin+radiation compared to the standard arm of cisplatin+radiation at 3 years follow-up, with increased but clinically manageable toxicity.177 These results are very promising, especially because the study was done in developing countries and so quickly; however, the study does raise a lot of questions, including whether the observed benefit was related to the concurrent use of chemotherapy, the adjuvant use chemotherapy, or both. It does not answer the question of whether this regimen was equally effective in stage IIB patients as well as stage III patients (see Table 87-4). Most studies have demonstrated that the use of combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy is associated with a statistically significant increase in gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicity that, although significant, has been tolerable. Data suggest that synchronous administration of chemotherapy potentiates radiation effect in cycling, immediately responding cell systems, in both cancer and normal tissue. Thus both immediate normal tissue reactions and side effects are potentiated. Importantly, an increase in catastrophic late complications such as bowel obstruction, fistula formation, or second malignancies, has not been seen. Given the preponderance of evidence, which suggests that synchronous radiation with radiopotentiating chemotherapy favorably affects the probability of cancer-free survival, clinical research into the optimal drugs and schedule of administration is likely to play a central role in clinical investigation for the foreseeable future.

Treatment of Locoregional Disease by Stage

Stages Ia1 and Ia2 (Microinvasion)

The purpose of defining microinvasion is to identify a group of patients who are not at risk for lymph node involvement and therefore are treatable with conservative therapy. In the current staging classification, stage Ia1 is defined as a tumor with stromal invasion no greater than 3 mm in depth beneath the basement membrane and no wider than 7 mm. Stage Ia2 is defined as a tumor with stromal invasion greater than 3 mm, no greater than 5 mm in depth, and no wider than 7 mm. Patients at highest risk for metastases or recurrence in this group appear to be those with evidence of tumor in the lymphovascular spaces.107,178

Patients with stage Ia1 disease can be adequately treated with therapeutic conization if conservation of reproductive capacity is desired, or extrafascial hysterectomy. The risk of pelvic lymph node metastases with 1 to 3 mm of stromal invasion is less than 1%.179,180 For patients opting for therapeutic conization, the following histopathological criteria should be met: (a) depth of stromal invasion 3 mm or less, (b) diameter of lesions less than 7 mm, (c) no lymphovascular invasion, and (d) clear margins. Patients treated with conization should be followed up closely with cytologic, colposcopic, and ECC evaluation every 3 months for the first year.181 A vaginal or a type I abdominal hysterectomy (extrafascial) is appropriate treatment if future childbearing is not desired.

Microinvasive carcinoma with stromal invasion 3.1 to 5 mm is associated with a 5% risk of nodal metastases.182 The preferred treatment for stage Ia2 is a modified radical (type II) hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. Treatment with radiation also will have a high probability of success and may be preferable therapy in patients who are compromised surgical candidates based on age and comorbidities.

Stages Ib1, Ib2, and IIa

Stage Ib is defined as a clinically evident lesion confined to the cervix or preclinical lesions greater than those of Ia2. Patients with IIa disease have extension to the upper vagina without parametrial involvement. The incidence of pelvic nodal metastases is approximately 15% to 25% for patients with stage Ib disease.182 Treatment must be directed toward the lymph nodes, cervix, parametrial tissue, paravaginal tissue, and upper vagina; therefore, a radical (type III) hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy and paraaortic lymph node evaluation has historically been the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy is as effective as surgery based on a prospective, randomized comparison conducted in Italy.183 In that study, 337 analyzed patients (FIGO stages Ib1, Ib2, and IIa) were randomly assigned to treatment with initial type III hysterectomy or with radiation therapy using a radiation dose (cumulative teletherapy and brachytherapy dose of 76 Gy at point A) that is substantially lower than the 85 to 90 Gy used in leading centers in the United States. Postoperative pelvic radiation therapy was administered to patients with positive nodes, positive margins, positive parametria, or less than a 3-mm surgical margin. Forty-six of 55 patients (84%) with tumors larger than 4 cm in diameter received postoperative radiation therapy. Chemotherapy was not used. Five-year survival and disease-free survival rates were identical in both groups (83% and 74%, respectively). Serious complications occurred in 28% of the group treated initially with surgery, and 12% of the radiation therapy group. Theoretically, results with chemoradiation might well be superior to those with surgery, but the benefit for synchronous administration of chemotherapy has been documented only in patients with tumors larger than 4 cm (Ib2) or more advanced stages of disease.

Given that surgery and radiation therapy are approximately isoeffective with respect to cancer control, treatment generally is selected on the basis of physician and patient preference and differences in treatment-related morbidity. Surgery provides important prognostic information and offers premenopausal women the option of ovarian conservation, because the risk of ovarian metastases is only 0.5%.143 Considerable debate concerns whether sexual function is more feasible or better after surgical treatment or radiation therapy. Both forms of treatment carry some risk of urologic or bowel injury. However, the nature of those complications, the ability to remedy those complications, and the impact of chronic complications on quality of life are both challenging to quantitate and vulnerable to subjective interpretation. Radiation carries a small but not trivial risk of late induction of second malignancies.

For patients with stage Ib1 who are young and free of major comorbid conditions, surgery tends to be the preferred option. In patients who are poor surgical risks or elderly, radiation therapy is more sensible. Radiation therapy usually is a combination of teletherapy intended to encompass the primary, microscopic regional extensions, and regional lymph nodes, supplemented by intracavitary brachytherapy intended selectively to take the gross disease in the uterus and cervix to a much higher dose while sparing normal tissues including bladder and rectum. When disease is very small (<1 cm in diameter), the risk of nodal metastases is low, and the treatment approach may be modified to intracavitary brachytherapy therapy alone with excellent results.153

The treatment of patients with stage Ib2 disease remains a source of continued controversy. With either surgery or radiation therapy, progressive decrements in survival probability are found as tumor size increases. In some centers, patients with stage Ib2 disease continue to undergo initial surgery, recognizing that most will have indications for postoperative radiation therapy, but that surgery will clear gross central disease, which is the most likely site of pelvic failure in patients treated with radiation. Because the morbidity of combined therapy is greater, some surgeons limit the radicality of surgical extirpation in anticipation of postoperative radiation therapy in a sensible effort to limit morbidity.184 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin, vincristine, and bleomycin for 3 cycles at 10-day intervals before attempted radical hysterectomy has been used with encouraging results in Ib2 cancers as reported by Sardi and colleagues in Argentina.185 Pathological downstaging was observed in patients operated on after neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with patients undergoing initial surgery. These results have not been reproduced in the context of a multiinstitutional trial, when tested by the GOG.

Alternatively, radiation has been used as initial therapy supplemented by type I adjuvant hysterectomy to clear central disease. The GOG compared radical radiation therapy with attenuated preoperative radiation therapy supplemented by extrafascial hysterectomy.167 A lower cumulative incidence of local relapse was noted in the radiation therapy plus hysterectomy group (at 5 years: 27% vs. 14%). No statistical differences were observed in outcomes between regimens, except for the adjusted comparison of progression-free survival, although all indicated a slightly lower risk in the adjuvant hysterectomy regimen (unadjusted relative risk of progression, 0.77; P = 0.07; unadjusted relative risk of death, P = 0.26; both one-tailed). Because preliminary analysis of this trial suggested benefit from surgery in improved local control, the GOG carried out a successor trial in which all patients had attenuated preoperative radiation therapy, followed by extrafascial hysterectomy. Half of the patients were randomized to receive weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 during teletherapy. The rates of both progression-free survival (P < 0.001) and overall survival (P = 0.008) were significantly higher in the combined therapy (chemoradiation) group at 4 years.167

Patients undergoing primary surgery for stages Ib and IIa cancer who are found to have adverse clinicopathological prognostic factors may be advised to undergo adjuvant postoperative pelvic radiation therapy or adjuvant chemoradiation. Much effort has been expended in attempting to define clinicopathological factors that reliably identify patients at high-risk for failure after initial surgical therapy. Primary tumor size, depth of cervical invasion, and LVSI are thought to be independent prognostic factors in node-negative patients with surgically treated stage Ib squamous carcinoma of the cervix.107 Parametrial extension186 and parametrial node metastasis,187 independent of retroperitoneal lymph node status,103 predict an increased risk of recurrence in surgically treated patients. Positive or insecure margins including vaginal margins,188 extension of cancer to the lower uterine segment,189,190 and adverse histopathology37 are additional parameters that may correlate with a more ominous outlook. Controversies persist concerning the relative importance of some of these factors in multivariant analysis. However, with consensus approaching unanimity, metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes is recognized as a dominant prognostic indicator.191

Two cooperative NCI-sponsored intergroup studies have been carried out prospectively evaluating adjuvant therapy for patients with adverse histopathological features after radical hysterectomy. Sedlis192 reported on 277 “intermediate-risk” node-negative patients who were identified based on combinations of tumor size, depth of cervical stromal invasion, and lymphatic space invasion. Based on historic outcomes, these patients were estimated to have an approximate 25% probability of recurrence after surgery, with the pelvis being the most probable site of relapse. Patients were randomly assigned to observation versus adjuvant pelvic teletherapy. In an update of this series by Rotman,122 there was a 46% reduction in the risk of recurrence (P = 0.007) and a significant improvement in recurrence or death (hazard ratio = 0.58) when postoperative pelvic irradiation was given. Although there was a 30% reduction in the risk of death for patients who received radiation therapy, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.07).

Peters108 reported on 243 analyzable “high-risk” patients who had positive nodes, parametrial extension, or positive surgical margins. After radical hysterectomy, these patients were randomly assigned to receive adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy, or the same adjuvant radiation regimen with 2 cycles of synchronous 5-FU and cisplatin followed by 2 further cycles of sequential 5-FU and cisplatin. Cisplatin was administered at 70 mg/m2, and 5-FU was administered at 1000 mg/m2 per 24 hours for 96 hours with each cycle. The projected progression-free survival at 4 years was 80% for the patients in the radiation-plus-chemotherapy arm compared with 63% in patients receiving adjuvant radiation alone. Analysis of patterns of treatment failure at the time of initial recurrence revealed that 11 of 127 patients receiving chemoradiation had a component of pelvic recurrence compared with 25 of 116 patients receiving radiation, suggesting that the addition of chemotherapy resulted in a 60% reduction in the rate of pelvic failure. A component of distant metastatic spread was seen in 13 of 127 patients in the chemoradiation group and 18 of 116 patients in the radiation group, suggesting that the addition of chemotherapy resulted in a 34% reduction in distant spread. Paradoxically, the effect of the chemotherapy appears to have been greater on local disease than on distant dissemination, suggesting that the primary benefit may have been as a potentiator of local radiation effect.

In a small, randomized trial, Tattersall193 reported that the addition of 3 cycles of cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin before adjuvant pelvic radiation produced no benefit compared with immediate postoperative radiation therapy in patients with stages Ib to IIa disease with pelvic node metastases. In a complementary, randomized trial in which all patients received adjuvant postoperative chemotherapy, Curtin194 reported that the addition of delayed adjuvant radiation produced no benefit in either pelvic control or survival.

Stages IIb and III

In the United States, patients with advanced disease are treated with chemoradiation. Teletherapy with synchronous chemotherapy is supplemented with intracavitary brachytherapy whenever feasible. The Syed-Neblett or Martinez interstitial templates are alternative brachytherapy approaches that have the theoretic advantage of extending the brachytherapy isodoses laterally to treat pelvic side walls and parametrium.195,196 However, it is unclear that this provides any advantage compared with conventional intracavitary brachytherapy supplemented by teletherapy boost treatments to limited volumes.

It is important to remember that even patients with very large tumors (even tumors measuring 7 cm or more in diameter) have a chance of being cured with radiation therapy alone, particularly if the patient is not found to have extensive regional metastases. Before the use of concurrent chemoradiation, 5-year survival rates for patients with stage IIb disease usually were reported to be between 50% and 75%.101,197,198 The broad range probably reflects differences in staging, patient selection, and treatment technique between reporting institutions. For patients with stage IIIb disease, reported survival rates after treatment with radiation therapy alone ranged between 30% and 50%.99,198–200 However, in recent years, prospective trials with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation have improved survival even more,108,167–170 and have become the standard of care in this group of patients. The data and studies have been discussed earlier in this chapter; however, two major studies and their updates are discussed below.

Although the preliminary finding of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 90–01, first published in 1999, demonstrated a highly significant overall survival benefit from chemotherapy among patients with stage Ib to IIb (79% vs. 55% at 5 years, P < 0.0001), no significant difference was found in survival among patients with stages III to IVa disease; at the time, follow-up was incomplete and the total number of patients with the more advanced stage was small, contributing to large confidence intervals on the results.169 However, an update in 2004201 showed a significant difference in disease free-survival (54% vs. 37%, P = 0.05) and a trend toward improved overall survival (59% vs. 45%, P = 0.07). An update of GOG 120, in which a greater percentage of patients enrolled had stages III to IV disease, found a significant improvement in progression-free survival and overall survival in patients receiving concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy with radiation therapy compared with patients receiving hydroxyurea and radiation, and the results were analogous in patients with stages IIb and III (each P < 0.025) (see Table 87-4).202

Regional Disease

Most patients treated with radical hysterectomy who are found to have lymph node metastases require postoperative radiation therapy. On the basis of the findings of Peters and colleagues,107 concurrent chemotherapy is recommended if no medical contraindications are present.

Patients with paraaortic node involvement can be treated effectively with extended-field irradiation. Five-year survival rates range between 25% and 50%. Some investigators have advocated prophylactic irradiation of the aortic nodes for patients with an increased risk of metastases to this region. The value of prophylactic extended-field irradiation was tested in two randomized trials. In RTOG 79–20,203 patients with stage Ib2 to IIb disease were randomly assigned to receive brachytherapy plus external beam radiation therapy to the pelvis or to the pelvis and paraaortic nodes. The absolute 5-year survival rate was significantly better for those who had paraaortic treatment, but no difference was found in disease-free survival. A European trial204 done at the same time had a similar randomization, but included patients with more advanced disease (e.g., with pelvic lymph node metastases or bulky stages IIb or IIIb disease). No significant difference was found in the 4-year disease-free survival rates between the two arms, but the rate of paraaortic node recurrence was significantly higher for patients in whom that area was not treated.

In several phase II studies, concurrent chemotherapy has been given with extended field irradiation.205,206 Although side effects are more significant when treatment fields are enlarged, combined therapy may be tolerable if careful consideration is given to the chemotherapy regimen, the volume of tissue irradiated, and other factors that might increase the risk of serious toxicity. However, new imaging techniques such as PET and safer methods of surgical evaluation of lymph nodes (e.g., retroperitoneal or laparoscopic lymphadenectomy), may increase the precision with which the extent of regional disease can be estimated, decreasing the margin for improvement to be gained by treating large volumes prophylactically. However, it is important to remember that there is no evidence that chemotherapy given concurrently with radiation can prevent recurrence in nonirradiated nodal sites (the rate of aortic recurrence in patients treated on RTOG 90–01 with pelvic chemoradiation was 9%).201

Some bulky nodal metastases can be difficult to control with external beam radiation therapy alone. Some investigators have suggested resections of nodes larger than 2 cm before radiation therapy. Several investigators have reported high local control rates in patients treated with excision of bulky nodes and radiation; however, the numbers of patients in these series are small.207,208 With standard radiation therapy, it is difficult to deliver a high enough dose to the node without exceeding normal tissue tolerance limits; however, with modern conformal or intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) techniques, this may be possible.

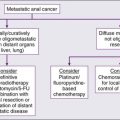

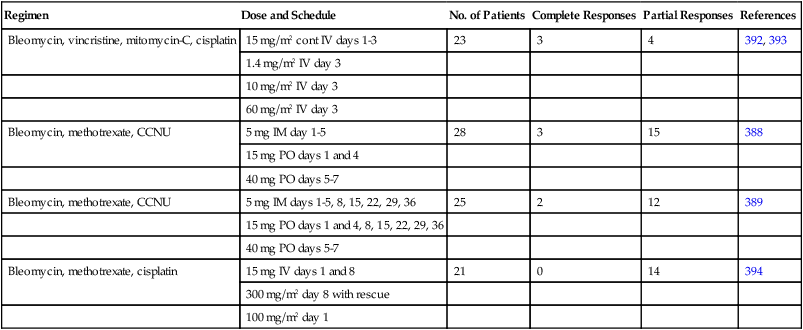

Treatment of Metastatic Disease and Salvage Chemotherapy

Cervical cancer is not considered curable with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy traditionally has been reserved for patients with extrapelvic metastatic disease or recurrent disease who are not candidates for radiation therapy or exenterative surgery. In an important GOG study, Thigpen and colleagues209 found that cisplatin has the greatest antitumor activity in advanced squamous carcinoma of the cervix, with a response rate of 20% to 25%. Unfortunately, in most series, responses to cisplatin are short-lived (3 to 6 months). The median duration of response for complete responders is 6 months, and the median survival is only 9 months.210,211 Other agents reported to achieve partial responses (15% to 25%) include carboplatin, iphosphamide, 5-FU, doxorubicin, methotrexate, hexamethylmelamine, mitomycin-C, vinblastine, bleomycin, paclitaxel, topotecan, vinorelbine, and irinotecan. Little objective evidence suggests that combination chemotherapy is superior to single-agent cisplatin.

Numerous platinum combination-based regimens incorporating drugs such as doxorubicin, iphosphamide, bleomycin, and, most recently, paclitaxel, have demonstrated higher response rates (typically in the 20% to 40% range) with the combinations having greater toxicity. A limited number of reasonably well-powered randomized trials comparing these doublets with either triplet regimens or singlet regimens have demonstrated that combination therapy leads to a slightly higher response rate and a longer progression-free survival that does not appear to affect overall survival.212,213

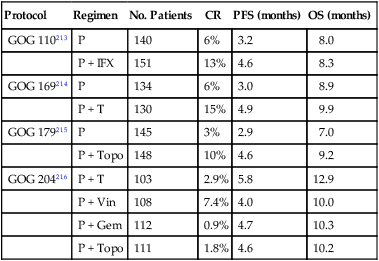

The GOG has done numerous trials in the recurrent and metastatic setting. One of these trials, GOG 169, compared paclitaxel and cisplatinum with single-agent cisplatinum.214 In this study of 241 eligible women, the response rate to single-agent cisplatin was 19%. The response rate to the doublet was 36%. The median time to progression was prolonged from 2.8 months with cisplatin alone to 4.8 months for the doublet. However, overall survival for the two arms was equivalent, with an 8.8-month median for cisplatin and a 9.7-month median for the doublet.214 The GOG did a subsequent trial with three arms, cisplatin, MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) and topotecan and cisplatin doublet. The MVAC arm was closed early because of toxicity and results showed a 2.9-month improvement in median survival favoring topotecan+cisplatin over cisplatin.215 These results led to the largest randomized trial in patients with cervical carcinoma, GOG 204. GOG 204 randomly assigned 513 patients with advanced (stage IVb), recurrent or persistent cervical cancer to four arms: paclitaxel+cisplatin (PC), vinorelbine+cisplatin (VC), gemcitabine+cisplatin (GC), and topotecan+cisplatin (TC).216 The results showed that VC, GC, and TC were not superior to PC in terms of overall survival; however, the trend in response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival favored PC (Table 87-5).216

Table 87-5

Comparison of GOG Phase III Trials for Advanced, Recurrent, or Persistent Cervical Carcinoma

| Protocol | Regimen | No. Patients | CR | PFS (months) | OS (months) |

| GOG 110213 | P | 140 | 6% | 3.2 | 8.0 |

| P + IFX | 151 | 13% | 4.6 | 8.3 | |

| GOG 169214 | P | 134 | 6% | 3.0 | 8.9 |

| P + T | 130 | 15% | 4.9 | 9.9 | |

| GOG 179215 | P | 145 | 3% | 2.9 | 7.0 |

| P + Topo | 148 | 10% | 4.6 | 9.2 | |

| GOG 204216 | P + T | 103 | 2.9% | 5.8 | 12.9 |

| P + Vin | 108 | 7.4% | 4.0 | 10.0 | |

| P + Gem | 112 | 0.9% | 4.7 | 10.3 | |

| P + Topo | 111 | 1.8% | 4.6 | 10.2 |

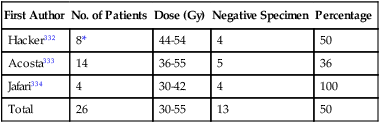

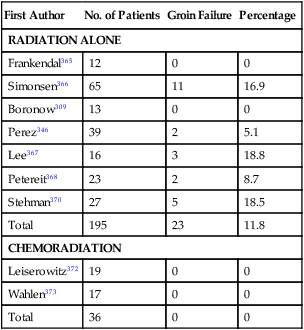

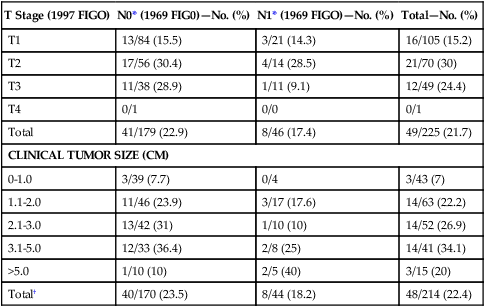

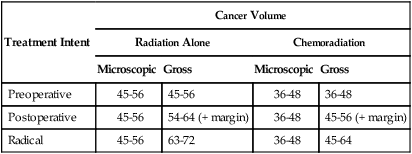

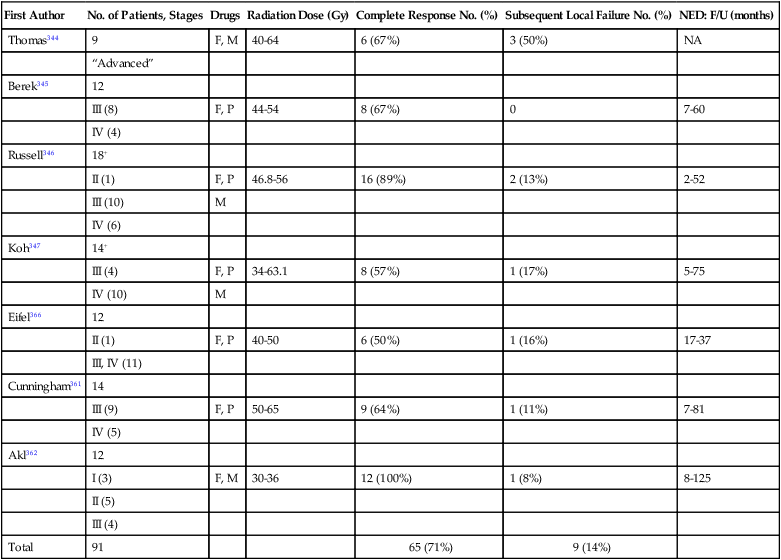

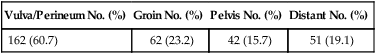

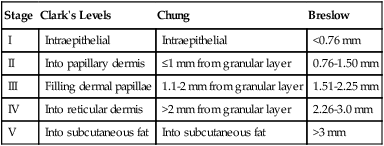

The experience with carboplatin is less. Nagao et al. reported a 76% objective response rate for carboplatin in combination with docetaxel.217 The Japan Clinical Oncology Group is presently conducting a phase III trial investigating paclitaxel in combination with either cisplatin or carboplatin to try to improve the toxicity profile.