Cancer-Related Pain

Stuart A. Grossman and Suzanne Nesbit

Major Presenting Symptom of Malignancies

• Cancer pain affects more than 30% of patients undergoing antineoplastic therapy.

• Moderate to severe pain occurs in more than 70% of patients during the later phases of their illness.

• Cancer pain significantly affects quality of life.

• Cancer pain is frequently managed poorly.

• Cancer pain can be of nociceptive, neuropathic, or sympathetically maintained origin.

• Cancer pain can be a result of direct tumor involvement (70%), evaluation or therapy (20%), or illness unrelated to the malignancy (<10%).

• Determining the etiology of pain is key to appropriate therapy.

• Pain should be treated aggressively during evaluation.

• The pain should be fully evaluated using a careful history, physical examination, and selected laboratory tests.

• Measurements of pain intensity should be performed with use of validated pain assessment scales.

• Results should be recorded serially as an integral part of the medical record.

• In 85% of patients, pain can be well palliated using simple, inexpensive, “low-technology,” oral analgesics.

• The addition of appropriate adjuvant pain medications, alternate routes of opioid administration, antineoplastic therapy, nonpharmacologic approaches, neurostimulatory techniques, regional analgesia, and neuroablative procedures provides excellent palliation for nearly all patients with pain relating to cancer.

Incidence

Facts

Pain is one of the most common and dreaded symptoms associated with cancer. It occurs in one quarter to half of patients with newly diagnosed malignancies, in one third of patients undergoing treatment, and in more than three quarters of patients with advanced disease. Overall, 75% of patients with cancer experience pain severe enough to require treatment with opioids during their illness.1 Unrelieved pain directly affects patients’ daily activities, quality of life, and psychological status. The importance of this symptom and the availability of excellent analgesic therapies make it imperative that health care providers be adept at the evaluation and treatment of cancer pain (Box 40-1).

Etiology

Pain in patients with malignancies is a complex and often recurring process that occurs as a result of many causes. Ninety percent of pain in patients with cancer results from the tumor or its evaluation or therapy to treat the tumor, whereas less than 10% is due to unrelated illnesses. In 70% of patients, pain develops when a tumor invades or compresses soft tissue, bone, or neural structures. The common pain syndromes that result are listed in Box 40-2. The remaining 20% of cancer pain occurs as a result of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that patients undergo in the process of evaluation and treatment.2 Examples of these procedures include venipuncture, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, endoscopy, lumbar puncture, invasive radiologic procedures, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Pain in patients who are long-term survivors of cancer is an increasingly important topic. Currently more than 3.5% of the population in the United States are cancer survivors, and this rate is rising annually.3,4 Chronic pain syndromes are surprisingly common in this patient population. Currently, about 50% of patients with head and neck cancer will become long-term survivors, and 17% of these persons report substantial chronic pain.5 Twenty percent of breast cancer survivors younger than 40 years who are treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy report significant pain years after treatment has been completed, and this pain appears to interfere with quality of life.6,7 Approximately 30% of long-term survivors of lung cancer report substantial pain related to their illness.8 In addition, hip and sacral pain related to prior treatment with radiation is seen in 30% of long-term gynecologic cancer survivors.9 Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain is also an increasingly important long-term problem for cancer survivors.10 Of particular importance is emerging information suggesting that inadequately treated acute pain may predispose long-term cancer survivors to chronic pain syndromes.11

Current Status of Cancer Pain Management

Although proper use of available therapeutic approaches should result in excellent pain control in nearly 95% of patients with cancer pain, this pain remains grossly undertreated throughout the world. In most countries, the lack of availability of oral opioids is a major contributing factor.12 Even in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where a wide range of opioid analgesics and routes of administration are readily available, studies suggest that cancer pain is undertreated. A survey of oncologists highlights their reluctance to assess pain routinely and to prescribe appropriate analgesics. These findings prompted the creation of cancer pain initiatives in most states and the development of cancer pain guidelines and algorithms.13–18 In addition, to improve the overall management of pain in the United States, The Joint Commission has set new standards for pain management that are required for continued accreditation.19

Barriers to the Provision of Adequate Analgesia

• Failure to appreciate the intensity of the pain their patients are experiencing

• Reluctance to evaluate the etiology of the pain

• Lack of training in pain management

• Excessive concern regarding the regulatory oversight of opioid prescribing

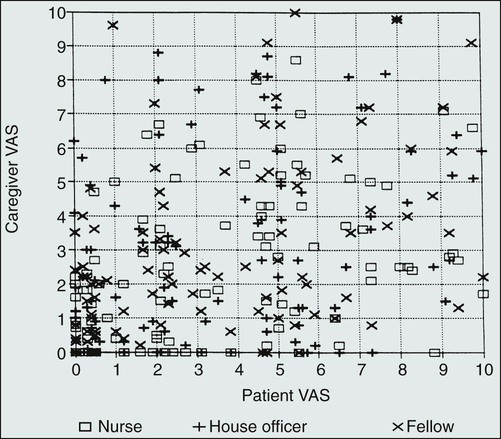

One major barrier to the provision of adequate analgesia in patients with cancer is the failure of health care providers to appreciate the intensity of patients’ pain. This barrier occurs because pain is entirely subjective and can only be experienced and quantified by the patient. There are no pathognomonic findings on physical examination, and results of laboratory studies can be normal. Assessment of pain is further complicated by the complexities surrounding death and dying and the possibility that patients with chronic, severe pain might not appear or act uncomfortable. In one study examining health care provider perceptions of patient pain, pain intensity was quantitatively assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) in 103 consecutive patients admitted to the solid-tumor service of a large cancer center.20 Each patient’s primary care nurse, house officer, and oncology fellow rated his or her perceptions of their patient’s pain intensity using the same pain rating instrument as the patient. The results (Fig. 40-1) demonstrate a lack of correlation between the patient’s and the health care provider’s perception of patient pain. Furthermore, the concordance between patient and health care provider pain intensity scores was highest when patients had no pain and lowest when the patients were experiencing severe discomfort. Similar results have been obtained in studies of patients with cancer and their next of kin and in patients with burns.

These issues are greatly magnified in children, the elderly, or persons with a history of drug abuse. Children have special difficulty in communicating pain intensity, and their unique pain management needs have been relatively neglected. Special pain assessment tools are required, and the child’s age and developmental level must be considered when planning assessment or interventions. Many elderly patients also find it difficult to communicate their discomfort to health care professionals, have multisystem disease, and are especially sensitive to the adverse effects of analgesics.21–24 Persons with cancer and a current or prior history of drug abuse often have difficulty finding health care providers who believe their reports of pain and who will provide the high doses of analgesics required by these opioid-tolerant individuals.25

Another barrier to the provision of adequate analgesia relates to the training of medical professionals. The principles of cancer pain management receive little attention in academic centers and relevant scientific societies. Medical school courses and textbooks typically focus on diseases rather than symptoms, and pain management issues are infrequently highlighted at rounds, educational conferences, or in the formal curriculum of those training to care for patients with cancer. These circumstances leave many health care professionals eager to concentrate on medical problems they feel competent to handle. In addition, the scarcity of research abstracts on cancer pain at the scientific meetings of physician oncologic societies reinforces the notion that pain control is a topic of limited importance. The lack of training and emphasis on cancer pain management is evident in many ways, including physicians’ lack of opioid-prescribing skills, failure to evaluate the etiology of cancer pain, and excessive concerns regarding the regulatory oversight of opioid prescribing. These difficulties in calculating equi-analgesic doses have prompted the development of software to facilitate opioid conversions.26

Physicians, pharmacists, and nurses caring for patients with cancer must be willing to prescribe, dispense, and administer the opioids in doses required to alleviate their pain. However, drug enforcement agencies often discourage opioid prescribing in an attempt to reduce the illegal diversion of these drugs. Some health care professionals with limited knowledge and experience react to the perceived threat of investigation by law enforcement agencies with dramatic decreases in opioid prescribing, potentially compromising the appropriate treatment of patients with cancer pain.27,28

Evaluation of the Patient with Pain

• Estimate the severity of pain

• Form a clinical impression regarding the etiology of the pain

• Determine the need for further diagnostic studies

• Formulate therapeutic recommendations that take into account the patient’s overall medical and psychosocial status (Box 40-3)

A detailed pain history is the cornerstone of the assessment. Obtaining this history can be a complex process, because 75% of patients with advanced cancer have several concurrent painful sites and nearly one third have four or more separate pain problems.19 Each distinct pain must be identified and characterized. Pertinent information should include its intensity, location, radiation, how and when it began, how it has changed over time, and what makes it better or worse. The quality of each pain, its temporal pattern, whether it is associated with neurologic or vasomotor abnormalities, how it interferes with the patient’s life, and an account of the successes and failures of current and prior therapeutic modalities also provide valuable insight.

Many instruments have been developed to aid in pain assessment. These instruments attempt to characterize and quantify the quality and/or intensity of a patient’s pain and represent the best available means to document the discomfort and to follow the results of therapy serially. Each instrument has its shortcomings, but several have been validated in patients with cancer pain and incorporated into clinical practice. Most instruments contain a variant of the unidimensional visual analog scale and a schematic representation of the body for patients to indicate where their pain is located. The McGill Pain Questionnaire is comprehensive but too awkward and time-consuming for most oncology patients in a clinical setting.29 The Wisconsin Brief Pain Inventory, which can be completed in 15 minutes, provides information on the characteristics, severity, and location of the pain, its interference with normal life functions, and the efficacy of prior therapy. The Memorial Pain Assessment Card can be completed in less than a minute and features scales for the measurement of pain intensity and pain relief.30 It is also designed to provide insight into global suffering or psychological distress. The Hopkins Pain Rating Instrument is a validated plastic version of the visual analog scale that obviates the need for the paper, pencil, ruler, and measurements associated with the standard visual analog scale.31 This instrument simplifies repeated pain intensity measurements, making it easier to reassess the efficacy of therapeutic endeavors on a continuing basis.32

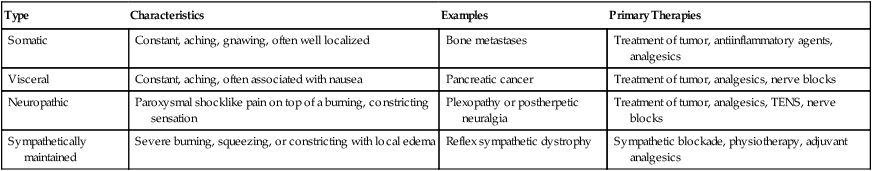

The history, physical examination, and review of other available data should provide the clinician with sufficient information to formulate a differential diagnosis for each of the patient’s distinct pains and to make recommendations regarding the workup and therapy for each. Based on this initial impression, analgesic therapy should be initiated. The nature of the treatment prescribed might depend on the clinician’s judgment regarding the origin of the pain. Somatic, visceral, neuropathic, and sympathetically maintained pain are each approached somewhat differently (Table 40-1). Prompt institution of therapy reassures patients that their pain will receive immediate attention, ensures patient comfort for diagnostic studies, and can provide information on the accuracy of the clinician’s assessment. Excellent pain relief suggests an accurate initial diagnosis and appropriate therapy, whereas suboptimal control might prompt a new treatment approach or a search for a different etiology of the pain.

Table 40-1

| Type | Characteristics | Examples | Primary Therapies |

| Somatic | Constant, aching, gnawing, often well localized | Bone metastases | Treatment of tumor, antiinflammatory agents, analgesics |

| Visceral | Constant, aching, often associated with nausea | Pancreatic cancer | Treatment of tumor, analgesics, nerve blocks |

| Neuropathic | Paroxysmal shocklike pain on top of a burning, constricting sensation | Plexopathy or postherpetic neuralgia | Treatment of tumor, analgesics, TENS, nerve blocks |

| Sympathetically maintained | Severe burning, squeezing, or constricting with local edema | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy | Sympathetic blockade, physiotherapy, adjuvant analgesics |

Management of Cancer Pain

Pharmacologic Therapy

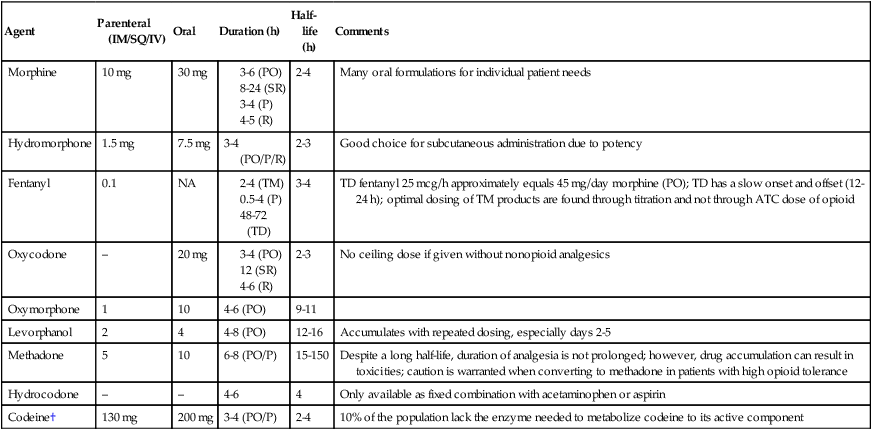

Pharmacologic approaches are the most commonly used treatments for cancer pain, because they are effective, safe, and usually inexpensive. These pharmacologic approaches are classified as nonopioids, opioids, and adjuvant analgesics. The World Health Organization’s analgesic ladder was introduced as a framework for analgesic prescribing. Aspirin, acetaminophen, or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are preferred for mild to moderate pain.33 If these drugs do not provide adequate analgesia, then codeine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone will frequently provide excellent relief. For persistent or severe pain, codeine (or its congener) is replaced by a potent opioid, such as morphine (Table 40-2). Drug rotation should be considered before an entire class of agents is abandoned, because patients frequently tolerate one NSAID or opioid better than another. In addition, patients with severe pain might need a strong opioid as initial therapy to ensure rapid pain relief.34

*Refer to www.hopweb.org for opioid conversions.

†Not recommended for acute or chronic pain management.14

The site of action of the nonopioids is primarily the peripheral nervous system. These agents are not associated with physical dependence, tolerance, or addiction, and they have a maximum dose associated with analgesia. Many are available in combination with a weak opioid. The antiinflammatory component of aspirin and of the NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors is often useful for patients with somatic pain from bone metastasis, inflammation, or mechanical compression of tendons, muscles, pleura, and peritoneum and for nonobstructive visceral pain. Because some of these agents can affect platelet and renal function or act as antipyretics, they should be administered thoughtfully to patients receiving chemotherapy. COX-2 inhibitors allow NSAIDs to be used with less risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and platelet dysfunction. However, the increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and hypertension in patients with a prior cardiac history warrants caution with both selective and nonselective NSAIDs.35 In addition, it is important to recognize that sustained high doses of acetaminophen can cause renal and hepatic damage, especially when combined with more than 2 oz of alcohol per day or with other agents that cause liver damage or induce hepatic microsomes. The manufacturer of Tylenol, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, voluntarily decreased the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen to 3 g per day on their product labeling.

Most patients with moderate to severe pain rely primarily on opioid analgesics for the management of their cancer pain. The pain of the vast majority of patients can be managed with oral opioids, which are best given “around the clock” to keep pain under control. Although tolerance to these agents occurs, tumor progression is the most common reason for increasing opioid requirements. Tolerance can easily be overcome by raising opioid doses. Addiction is extremely rare in patients with cancer who are taking opioids for pain relief (Box 40-4). Most opioid adverse effects can be managed without excessive difficulty (Table 40-3). Constipation should be anticipated and treated prophylactically.36

Table 40-3

Management of Common Opioid Adverse Effects

| Adverse Effect | Specific Agents |

| Constipation | Stool softeners |

| Irritants | |

| Bulk laxatives | |

| Lubricants | |

| Enemas Peripheral Mu antagonists |

|

| Nausea and vomiting | Promethazine |

| Prochlorperazine Haloperidol |

|

| Olanzapine | |

| 5HT3 antagonists Dronabinol |

|

| Scopolamine | |

| Sedation | Dextroamphetamine |

| Methylphenidate | |

| Modafinil | |

| Pruritus | Hydroxyzine |

| Diphenhydramine | |

| Myoclonus | Benzodiazepines |

| Anxiolytics | |

| Withdrawal symptoms | Clonidine |

1. Morphine-like opioid agonists that bind competitively with µ and κ receptors (e.g., codeine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, and methadone)

2. Opioid antagonists that have no agonist receptor activity (e.g., naloxone)

3. Mixed agonists-antagonists (e.g., pentazocine and butorphanol) or partial agonists (e.g., buprenorphine)

The mixed agonist-antagonist drugs have limited utility in persons with cancer pain because of their adverse effect profiles and their propensity to induce opioid withdrawal in patients who have received opioid agonists. Proper opioid prescribing is critical for patients with cancer (Box 40-5), who often require high doses of opioids for long periods.14

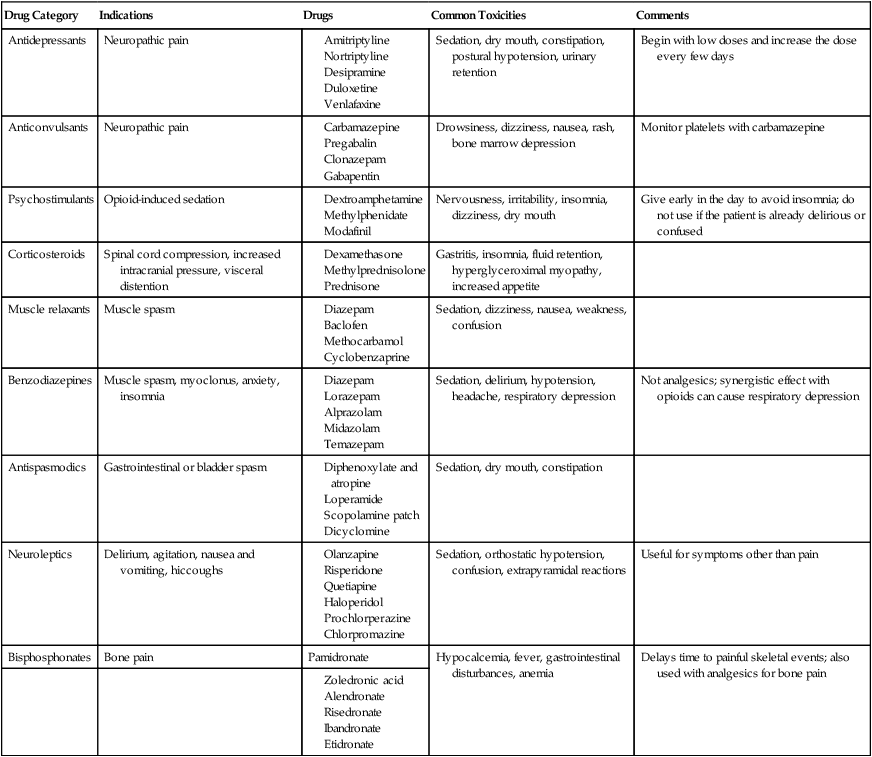

Several classes of drugs that are used primarily for conditions other than pain have been found to be useful adjuvant analgesics in specific circumstances (Table 40-4).14 Antidepressants and anticonvulsants can be effective in neuropathic pain. Psychostimulants can decrease opioid-induced sedation. Glucocorticoids are effective antiinflammatory agents and are also used to reduce pain associated with brain edema and epidural metastases. Muscle relaxants and anxiolytic, antispasmodic, and neuroleptic agents also are administered for specific indications. Bisphosphonates reduce the incidence of skeletal complications, particularly in patients with myeloma and breast cancer. Caution must be exercised in the use of adjuvant drugs that have sedative properties because the dose of opioids should not be compromised by the toxicities of these secondary agents.

Table 40-4

Commonly Used Adjuvant Analgesics for Cancer Pain

| Drug Category | Indications | Drugs | Common Toxicities | Comments |

| Antidepressants | Neuropathic pain | Sedation, dry mouth, constipation, postural hypotension, urinary retention | Begin with low doses and increase the dose every few days | |

| Anticonvulsants | Neuropathic pain | Drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, rash, bone marrow depression | Monitor platelets with carbamazepine | |

| Psychostimulants | Opioid-induced sedation | Nervousness, irritability, insomnia, dizziness, dry mouth | Give early in the day to avoid insomnia; do not use if the patient is already delirious or confused | |

| Corticosteroids | Spinal cord compression, increased intracranial pressure, visceral distention | Gastritis, insomnia, fluid retention, hyperglyceroximal myopathy, increased appetite | ||

| Muscle relaxants | Muscle spasm | Sedation, dizziness, nausea, weakness, confusion | ||

| Benzodiazepines | Muscle spasm, myoclonus, anxiety, insomnia | Sedation, delirium, hypotension, headache, respiratory depression | Not analgesics; synergistic effect with opioids can cause respiratory depression | |

| Antispasmodics | Gastrointestinal or bladder spasm | Sedation, dry mouth, constipation | ||

| Neuroleptics | Delirium, agitation, nausea and vomiting, hiccoughs | Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, confusion, extrapyramidal reactions | Useful for symptoms other than pain | |

| Bisphosphonates | Bone pain | Pamidronate | Hypocalcemia, fever, gastrointestinal disturbances, anemia | Delays time to painful skeletal events; also used with analgesics for bone pain |

• Intractable vomiting or gastrointestinal tract obstructions, making oral therapy impractical

• Ineffective pain relief despite titration to toxicity with several oral opioids

• Unacceptable toxicities to several oral opioids

• Such high opioid requirements that oral administration is impractical

Transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl (TIRF) products can be effective for patients with incident or breakthrough pain, for whom rapid onset and short duration of action are desired.37 These fentanyl products are available as a lozenge, a buccal and sublingual tablet, a soluble film, and a sublingual and nasal spray. The onset of analgesia can be as soon as 5 minutes. The optimal dose for these delivery systems is found through titration and is not predicted by the around-the-clock dose of opioids. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration enacted a TIRF Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, which requires providers and pharmacists to enroll and complete training before prescribing or dispensing TIRF products. Patients must sign an agreement before initiating therapy.38

Intraspinal opioids produce analgesia without blocking other sensory, motor, or sympathetic functions. These opioids can be delivered into the epidural space through a tunneled external catheter or to the subarachnoid space or lateral ventricles using a totally implanted pump.39 Because the total daily dose of intraspinal opioid is one tenth to one hundredth that of parenteral opioid, it is associated with fewer systemic toxicities. Chronic administration of opioids via the epidural or intrathecal route is invasive, expensive, and frequently ineffective in patients requiring high doses of systemic opioids. Tolerance, pruritus, urinary retention, and nausea and vomiting occur in as many as 20% of patients receiving opioids via the spine. Respiratory depression is unusual. The addition of low doses of anesthetic agents or agents such as clonidine to opioids delivered via the intrathecal or epidural route could add considerably to pain relief. Ziconotide, a selective N-type calcium channel blocker, is approved for intrathecal analgesia in patients with pain refractory to other treatments.40 Intraspinal opioids are generally used after documentation of the failure of maximal doses of opioids delivered through other routes.41 Consensus guidelines are available to guide the practitioner with proper drug selections for intraspinal analgesia.42

Antineoplastic Therapy

Antineoplastic therapy can provide analgesia if it reduces the size of lesions invading or compressing normal tissues. Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for most patients with local pain from tumor progression. It is frequently administered to patients with symptomatic bone, brain, epidural, and plexus metastases. Systemic radiopharmaceutical agents such as strontium-89 and samarium are also used for the treatment of pain from bone metastases.43 Chemotherapy can provide substantial pain relief in malignancies that respond rapidly and frequently to this therapeutic modality. Surgery can be effective in relieving pain from intestinal obstruction, pathological fractures, and obstructive hydrocephalus.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Neurostimulatory techniques, such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, are safe, noninvasive, relatively inexpensive, and easily added to other analgesic approaches. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation could provide short-term benefits in patients with cancer, and a 2- to 4-week trial will often determine its clinical usefulness. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as progressive muscle relaxation, massage, use of heat or cold, guided imagery, biofeedback, hypnosis, and acupuncture are useful adjuncts to pain management.44 Although psychotherapy is indicated for an associated depression, unrelieved pain can result in depression that is best treated with analgesic therapies.

Invasive Therapy

Although most cancer pain can be well controlled using the techniques previously discussed, some pain remains refractory, and some patients have persistent adverse effects from opioids despite aggressive therapy with psychostimulants, antiemetics, and laxatives. The adverse effects can be severe enough that patients might refuse to take sufficient medication to relieve their pain. Adding adjuvant medications, changing to another opioid, or using continuous intravenous or subcutaneous infusions to reduce “peak” levels might be helpful. In select patients, regional analgesia or neuroablative procedures might permit the doses of pharmacologic agents to be reduced substantially.45 In particular, spinal metastases may be treated with minimally invasive therapies such as vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty, or radiofrequency ablation.46,47 Neurosurgery has been shown to be the first-line therapy over radiation therapy in the management of a solitary spinal metastasis.48,49 These invasive approaches should be considered under the following conditions:

Regional Analgesia

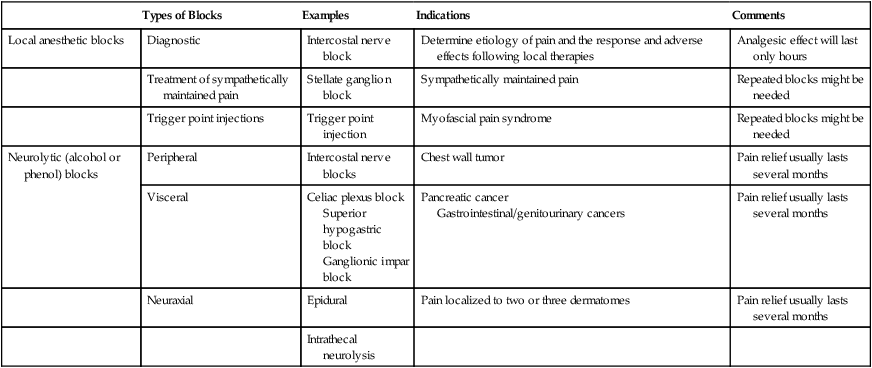

Regional analgesia can be achieved with long-acting local anesthetics that provide pain relief for 3 to 12 hours, neurolytic agents (alcohol or phenol) that produce analgesia for weeks to months, or opioids injected into the epidural or subarachnoid space (Table 40-5). Diagnostic blocks with local anesthetics are usually performed before neurolysis, which permits the anesthesiologist to determine the response to local therapy and allows the patient to decide whether the “numbness” that replaces the pain is tolerable. If the pain can be relieved temporarily with local anesthetics, alcohol or phenol can be injected into the subarachnoid or epidural space to destroy nociceptive fibers in the dorsal rootlets, thus simulating a surgical rhizotomy. Although injections of these neurolytic agents are commonly called “permanent blocks,” pain relief usually lasts several months. Neurolytic blocks can be particularly useful in the thoracic region, where they are associated with few motor complications. In the cervical and lumbar regions, motor and/or sphincter dysfunction that can be permanent develops in nearly 20% of patients. In patients with preexisting lower extremity paralysis, a colostomy, or nephrostomy tubes—cases in which loss of motor or sphincter function might be less critical—lumbar neurolysis might be worthwhile. Other potential adverse effects of these procedures include hypotension, toxic reactions from accidental intravenous or subarachnoid administration, or pneumothorax after needle placement. Neurolysis is usually restricted to patients with a limited life expectancy, because it can produce a painful neuritis that becomes clinically apparent only months after the procedure.

Table 40-5

Regional Anesthetic Techniques

| Types of Blocks | Examples | Indications | Comments | |

| Local anesthetic blocks | Diagnostic | Intercostal nerve block | Determine etiology of pain and the response and adverse effects following local therapies | Analgesic effect will last only hours |

| Treatment of sympathetically maintained pain | Stellate ganglion block | Sympathetically maintained pain | Repeated blocks might be needed | |

| Trigger point injections | Trigger point injection | Myofascial pain syndrome | Repeated blocks might be needed | |

| Neurolytic (alcohol or phenol) blocks | Peripheral | Intercostal nerve blocks | Chest wall tumor | Pain relief usually lasts several months |

| Visceral | Celiac plexus block Superior hypogastric block Ganglionic impar block |

Pancreatic cancer Gastrointestinal/genitourinary cancers |

Pain relief usually lasts several months | |

| Neuraxial | Epidural | Pain localized to two or three dermatomes | Pain relief usually lasts several months | |

| Intrathecal neurolysis |

Neurolytic blocks are used in select patients who have localized or regional pain. Percutaneous celiac plexus neurolysis is an outpatient procedure associated with few risks; it alleviates pain originating in the pancreas, stomach, gallbladder, or other upper abdominal viscera in most patients. One randomized, prospective, double-blind trial comparing celiac plexus injections of alcohol or saline solution and systemic analgesic therapy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer showed greater pain relief with the block. Opioid consumption and quality of life were not statistically significant, however.50 In other settings, it has been shown to decrease opioid requirements. Although pain can recur months after a celiac block, subsequent blocks can provide excellent pain relief. Less commonly used neurolytic procedures include intercostal blocks (chest wall or rib pain), neuraxial blocks (pain in two to three dermatomes), Gasserian ganglion neurolysis (pain in the anterior two thirds of the head), brachial plexus blocks (for patients with preexisting limb paralysis), and ganglion impar and superior hypogastric blocks (for lower abdominal and pelvic pain).

Difficult-to-Manage Pain Problems

Difficult-to-manage pain problems are most common in patients with any of the following conditions:

Patients with Pain of Neuropathic Origin

Any injury to the peripheral or central nervous system can cause neuropathic pain, which is often characterized by paroxysms of shocklike pain on top of a burning or constricting sensation. Neuropathic pain in patients with cancer commonly arises when a tumor invades or compresses a peripheral nerve, nerve plexus, or the spinal cord. It can occur as a result of surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy as exemplified by postmastectomy and postthoracotomy syndromes, radiation-induced plexopathies, and chemotherapy-induced neuropathies.51 Neuropathic pain also can accompany disorders that are unrelated to the tumor or its treatment, such as diabetes mellitus, nerve entrapment syndromes, and herpes zoster.

Providing adequate relief from neuropathic pain can be difficult even for experienced physicians.52 Although this pain may improve upon the administration of opioids, it usually responds less well to these agents than does nociceptive pain. Optimal therapy for neuropathic pain often relies on opioids used in combination with a variety of nonopioid “adjuvant” analgesics (see Table 40-4). Tricyclic antidepressants have been studied most extensively in this situation. Although the most convincing efficacy data is with amitriptyline, this agent is associated with significant anticholinergic effects and sedation. Other drugs in this class with a more favorable toxicity profile include desipramine and nortriptyline. Duloxetine, a serotonin and dual serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has a substantial effect in neuropathic pain.53

Anticonvulsant agents are also helpful in the management of neuropathic pain, particularly if the pain has lancinating qualities. The doses of these agents are similar to those used for the control of seizures. Care must be taken to avoid abrupt withdrawal, which could induce seizures. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy.54 Other studies suggest that it might help in the management of neuropathic pain resulting from cancer or its treatment. This agent is well tolerated, no drug-drug interactions have been identified, and the average effective dose is 1800 to 3600 mg/day. Pregabalin has a mechanism of action and adverse effects similar to gabapentin. Maximum doses are achieved within 1 to 2 weeks, offering a potential advantage over gabapentin. Systemically administered local anesthetics have been used for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Anesthetic creams that produce few systemic adverse effects are also available. Topical lidocaine patches are an effective means to control neuropathic pain that is confined to a small area. In clinically controlled trials, intravenous lidocaine has been demonstrated to be as effective as other analgesics for refractory pain.55,56 Capsaicin, a neurotoxin that selectively destroys nociceptors, is also manufactured as a topical preparation and provides relief in some patients. If oral agents and topical creams are ineffective, afferent input can be reduced with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or regional anesthetic techniques such as long-term epidural catheters or intrathecal pumps for the delivery of local anesthetics. Neurolytic blocks, more invasive neurostimulatory techniques, or even neurosurgical procedures might be indicated in extreme situations.

In patients experiencing opioid-resistant pain, unique agents such as ketamine can be considered. Ketamine is a rapidly acting dissociative anesthetic agent that in subanesthetic doses can provide relief for patients with cancer. Although no large randomized, controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of ketamine have been performed, a large body of uncontrolled trials and case reports exists. Ketamine can be administered by several routes of administration including intrathecal, intravenous, topical, and intranasal. The agent is generally well tolerated at the lower doses, with the major concern being psychotomimetic effects. Its analgesic and opioid-sparing effects are postulated to be mediated by blockade of the NMDA receptor. The efficacy of ketamine persists after the medication has been discontinued, which may be beneficial.57,58

Patients with Episodic or Incidental Pain

It is widely recognized that some patients experience transient but severe exacerbations of their pain. These exacerbations can occur for a variety of reasons, one of which is an inadequate analgesic regimen. For example, a patient who receives opioids every 6 hours and has good relief for only 4 hours needs a change in regimen to ensure that opioid levels will not fall below the analgesic threshold after 4 hours. This change is best accomplished by providing the agent more frequently or by administering sufficient doses of a sustained-release preparation. Episodic pain associated with voluntary or involuntary movements poses a more difficult therapeutic problem. Examples of these “incident” pains are seen in patients with pelvic metastases or pathological fractures who have severe pain with walking or sitting, patients with rib metastases who experience stabbing chest pain with movement or coughing, or patients with esophageal, rectal, or bladder lesions with pain on swallowing, defecation, or urination, respectively. Involuntary precipitants can include bowel or ureteral distention. In a study of incident pain, nearly three quarters was directly related to neoplastic lesions, 20% resulted from antineoplastic therapy, and the remainder was unrelated to the tumor or its treatment.61–61

Many of the approaches described in the foregoing discussion might not be effective, or even possible or advisable, in the context of a patient’s illness. In such situations, opioids remain the mainstay of therapy. The baseline dose of opioid can be escalated until pain relief or intolerable adverse effects occur. Although this approach might produce relief, patients are often excessively sedated during the intervals between the severe pain episodes. Alternatively, patients might elect to take supplemental analgesics (usually short-acting opioids) 30 to 60 minutes before they know a precipitating event is likely to occur. If the pain is unpredictable, the additional medications are taken as soon as the pain begins. The optimal timing of opioids for episodic pain is difficult to achieve. Episodic pain is characterized by a quick onset and short duration. Although parenteral opioids have a faster onset of action than oral opioids, using them is not practical in the home setting. Alternatively, transmucosal fentanyl products may provide the best option. The doses of these supplemental opioids must be determined from the patient’s baseline opioid requirements. It is common to begin with 5% to 10% of the total daily opioid dose ordered every 2 to 3 hours as needed. The dosing of transmucosal formulations, as previously mentioned, is determined through titration and is not based on the baseline opioid requirement.59

Patients with a History of Substance Abuse

The principles of cancer pain assessment and management in patients with a current or prior history of drug abuse are similar to those for any patient with cancer pain.25 These individuals should not remain in pain as a result of this complicating medical problem. Patients with a history of drug abuse, however, often have difficulty finding physicians who believe their reports of pain and who will provide the high doses of analgesics required in these opioid-tolerant individuals. As a result, they can become angry, frustrated, and more persistent in their demands for opioids. This constellation of symptoms is also seen in patients who do not have a history of drug abuse but who have severe, untreated pain. Their preoccupation with obtaining analgesics is referred to as pseudoaddiction and tends to disappear rapidly with appropriate pain therapy.

Conclusion

Cancer pain remains undertreated despite evidence that a careful assessment of cancer pain and the appropriate use of available therapies should result in excellent relief in nearly 95% of patients. Providing optimal cancer pain relief tests the skills and commitment of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists, because the diagnostic, therapeutic, and social issues in these patients are complex and constantly changing. Meeting these challenges can be satisfying, because patients and family are grateful to find that pain can usually be alleviated. Furthermore, as noted in the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s policy statement on cancer pain, “patients with cancer have a right to effective treatment of pain” and the “evaluation and treatment of cancer pain are an integral part” of each caregiver’s responsibilities.18