Cancer of the Small Bowel

Laura Doyon, Alexander Greenstein and Adrian Greenstein

• Small bowel tumors are rare, with incidence of less than 10% of new gastrointestinal cancer diagnoses and less than 1% of all new diagnosed cancers each year.

• Genes involved include APC and KIT and mismatch-repair genes.

• Malignant small bowel tumors consist of carcinoid (37.4%), adenocarcinoma (36.9%), lymphomas (17.3%), and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) (8.4%).

• Staging is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. Gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma is staged with the Ann Arbor system based on lymphatic and extra lymphatic involvement above and below the diaphragm.

• Primary therapy for small bowel neoplasms is surgical resection. Appropriate lymphadenectomy must be performed for adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors.

• Chemotherapy is often used for adenocarcinoma; however, there is no clear benefit for prognosis. GISTs are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

• Surgery may be used to control complications of local symptoms such as bowel obstruction. Chemotherapeutic options are being explored that do not have a clear benefit for prognosis as of this time.

• Gastrointestinal bleeding, mechanical obstruction, pain, and perforation may require palliative surgery in situations when curative resection is not possible. The use of palliative chemotherapy is also being explored. Somatostatin analogs are used in carcinoid syndrome.

Epidemiology

Small bowel cancer is rare, comprising less than 1% of new cancer diagnoses each year. The estimated incidence of new cases of small bowel malignancies in 2012 is 8,070, with 1,150 deaths. This is in contrast to the estimated new cases of colorectal cancer totaling 143,460, with 51,690 deaths. Small bowel cancer makes up less than 10% of gastrointestinal cancers each year.1

However, 17 years later, results from 2004 SEER database documented that the overall incidence of small bowel malignancies increased (from 2.1 to 9.3 per million). Carcinoid tumors have now superseded adenocarcinoma in incidence: carcinoid 37.4%, adenocarcinoma 36.9%, lymphomas 17.3%, and stromal tumors 8.4%.2 The overall increased incidence appears to be largely due to carcinoid tumors; it is unclear whether this is due to improved imaging, because most carcinoids are asymptomatic.

SEER trends from 1973 to 2000 showed an increasing incidence in black men, who had roughly double the rate of incidence of both carcinoid and carcinoma compared with whites (10.6 vs. 5.6 per million people and 9.2 vs. 5.4 per million people, respectively).3

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

The rarity of small bowel cancer has made the study of its pathogenesis difficult. However, the etiology of small intestinal adenocarcinoma may be similar to that of colon cancer because it appears to share the adenoma-carcinoma sequence previously described in colon cancer.4 Nevertheless, although the small bowel contains 90% of the mucosa of the GI tract, it is surprising that this results in only 1% to 2% of gastrointestinal malignancies. Previous theories as to why cancer of the small bowel mucosa is so rare compared with the colon include the small bowel’s lower bacterial load and faster transit time of ingested carcinogens. The three main categories of risk factors include environmental, genetic, and chronic inflammatory factors.

Genetic Factors

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in the adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) gene. In addition to the thousands of colonic polyps these patients typically develop, patients have nearly 100% cumulative lifetime risk of developing duodenal polyps that may become malignant. In fact, in postcolectomy patients, duodenal cancer as well as abdominal desmoid tumors seem to be the most important factors in long-term cancer risk.6

Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) is a condition caused by loss of DNA mismatch repair genes and predisposes patients to increased risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma in addition to colonic carcinoma. In a series by Rodriguez-Bigas et al., 42 individuals with HNPCC developed 42 primary and 7 metachronous small bowel tumors, with 46 adenocarcinomas and 3 carcinoids. The small bowel was the first site of carcinoma in 57% of these patients.7

Lastly, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant polyposis disorder with substantially increased relative and absolute risk of several types of cancer, including adenocarcinoma of small bowel.8

Chronic Inflammation

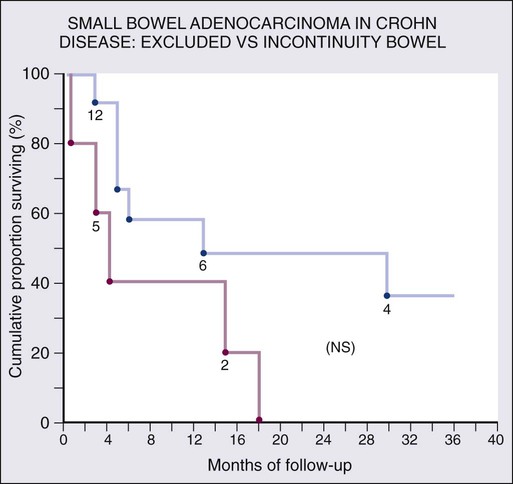

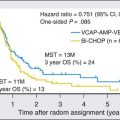

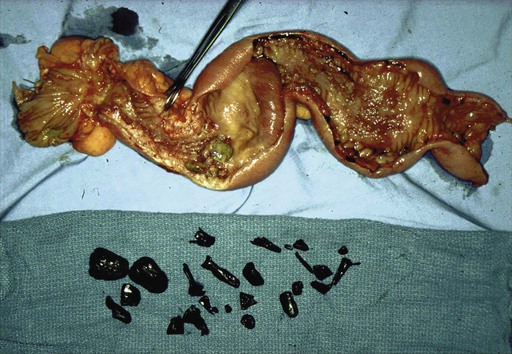

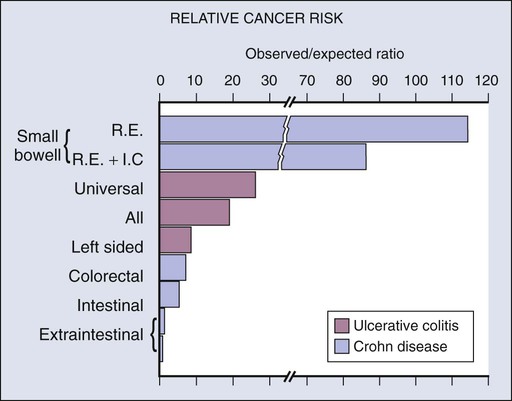

Chronic mucosal inflammation has been noted as a cause for development of adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. A series of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) at The Mount Sinai Hospital demonstrated that 67% of GI cancers associated with Crohn disease and 96% of those associated with ulcerative colitis were located in diseased bowel.9 In this series, seven cancers were found in the bypassed loops of diseased bowel, an operation seldom performed today (Fig. 76-1).10

Clinical Presentation

In general, small bowel tumors are almost always discovered late because presenting symptoms are vague. Pain, often crampy, is the most common presentation, followed by nausea and vomiting, and then weight loss. Small bowel obstruction tends to occur more often in malignant cases, whereas GI bleeding is more frequent with benign tumors.11 Mean age at presentation is 65 years, with a slight predominance in men.12 The mean age in Crohn disease–related small bowel cancer is about a decade earlier.10,13

Malignant Tumors of the Small Bowel

Adenocarcinoma

Symptomatic Presentation

Adenocarcinoma presents most often in patients between ages 50 and 70 years, but predisposing factors such as Crohn disease may cause an earlier presentation. Prevalence is slightly increased in males. In a series of 491 patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma, the following distribution of presenting symptoms was noted: abdominal pain (43%), nausea and vomiting (16%), anemia (15%), overt GI tract bleeding (7%), jaundice (6%), weight loss (3%), other or no symptoms (9%).14 More proximal lesions present with nausea and vomiting, and distal lesions present with crampy pain and distention before the onset of vomiting.

Although adenocarcinoma associated with Crohn disease tends to occur in the ileum, isolated cases of adenocarcinoma may occur in the duodenum. Diagnosis is particularly difficult in Crohn disease despite the increased incidence because of the difficulty of surveillance even with the more recent use of capsule endoscopy. The symptoms are difficult to differentiate from the symptoms of obstructing Crohn disease (Figs. 76-2 and 76-3). Physicians should consider this possibility if symptoms recur after a long period of quiescence.

Pathology reports from the population-based Cancer Surveillance Program found that 50% of small bowel adenocarcinoma occurred in the duodenum, and half of those were located in the second portion specifically, despite the fact that the duodenum composes only 4% of small bowel length. Possible explanations are that bile might be carcinogenic, or that the alternating acidic and alkaline environments from gastric and pancreatic secretions may be caustic.15

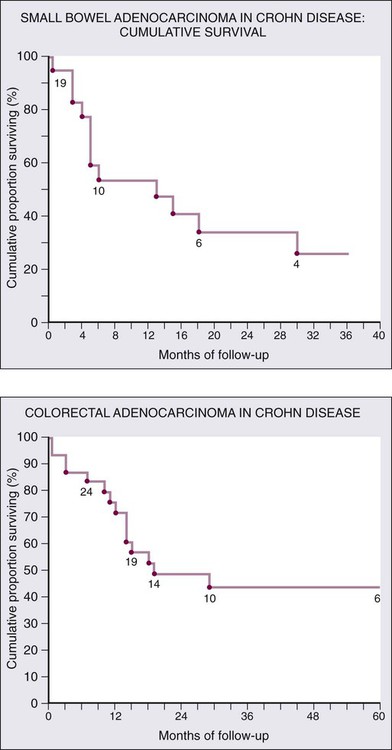

Although there is a well-documented increased relative risk of developing intestinal adenocarcinoma in Crohn disease compared with the general population, it is still rare (Fig. 76-4). A 25-year history of regional ileitis only confers a cumulative risk of 2.2%.16 The authors’ experience at The Mount Sinai Hospital between 1960 and 2009 involved 48 cases of small bowel carcinoma in two series of patients with Crohn disease. The overall average time between initial diagnosis of Crohn disease to diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma was 25.8 years.10,13

Because early symptoms are vague, these tumors often present at a late stage: 3% present as carcinoma in situ, 12% as stage I, 27% as stage II, 26% as stage III, and 32% as stage IV.17

Surgical Management

As with colorectal adenocarcinoma, the primary therapy of localized small bowel adenocarcinoma is radical segmental resection including associated mesentery and lymph nodes. Adequate nodal resection provides vital information for staging as well as clearance of early lymph node metastases. For tumors of the duodenum, traditionally pancreaticoduodenectomy has been performed; however, there is some suggestion that segmental duodenal resection may be performed especially for more distal lesions.18 Tumors of the terminal ileum require an ileocolic resection.

Postoperative Chemotherapy and Neoadjuvant Therapy

Although in practice, adjuvant chemotherapy is used to treat small bowel adenocarcinoma, as of this time, there is no clear evidence for benefit.19 Common regimens are 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based plus platinum-type chemoradiotherapy. Newer studies are exploring the role of neoadjuvant therapy. The difficulty of preoperative diagnosis virtually precludes this modality in the vast majority of patients. Preoperative diagnosis was made in only 2 of 19 patients in the earlier described series. Unresectable disease is usually treated with palliative chemotherapy although it is unclear that it will improve prognosis. Heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may be useful for treating cancer that has metastasized to the peritoneal cavity, in addition to cytoreductive surgery.39

Prognosis

Outcomes are generally worse for similarly staged small bowel compared to colon adenocarcinoma; the most important staging factor is node status (Fig. 76-5). Five-year disease-specific survival by stage is as follows: stage I, 65%; stage II, 48%; stage III, 35%; stage IV, 4%.20 Additionally, adenocarcinoma of the duodenum tends to have worse outcomes than adenocarcinoma of the jejunum or ileum.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Symptomatic Presentation

As discussed previously, carcinoid tumors appear to be increasing in incidence, and can present in patients ranging from 20 to 80 years old, with predominance in the 60s. Incidence, location, and presentation do not seem to be influenced by the presence of Crohn disease.21 Carcinoid tumors are classified by their location of origin—foregut, midgut, or hindgut. Most often, these tumors are located in the ileum, within 60 cm of the ileocecal valve. In 30% of cases, multiple nodules exist, thus making adequate evaluation of the entire length of bowel mandatory.22

Surgical and Medical Management of Incidental, Functional, Multiple, and Metastatic Carcinoid Tumors

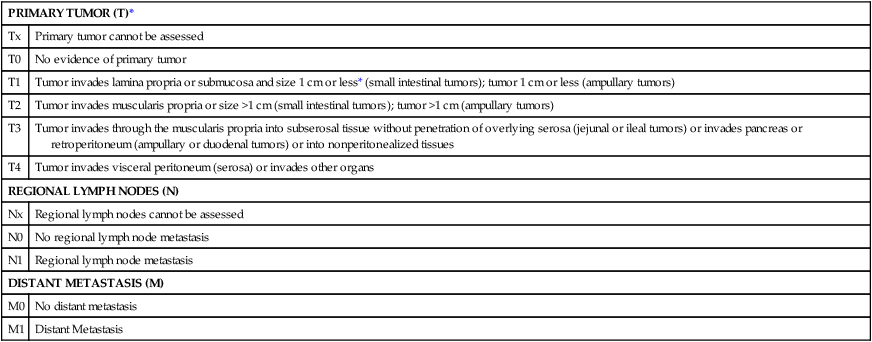

Tumor staging is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system (Table 76-1).

Table 76-1

Tumor-Node-Metastasis: Gastrointestinal Carcinoid

| PRIMARY TUMOR (T)* | |

| Tx | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa and size 1 cm or less* (small intestinal tumors); tumor 1 cm or less (ampullary tumors) |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria or size >1 cm (small intestinal tumors); tumor >1 cm (ampullary tumors) |

| T3 | Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into subserosal tissue without penetration of overlying serosa (jejunal or ileal tumors) or invades pancreas or retroperitoneum (ampullary or duodenal tumors) or into nonperitonealized tissues |

| T4 | Tumor invades visceral peritoneum (serosa) or invades other organs |

| REGIONAL LYMPH NODES (N) | |

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| DISTANT METASTASIS (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant Metastasis |

*For any T, add (m) for multiple tumors.

From AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Treatment of nonmetastatic disease consists of segmental resection of the affected portion of bowel in addition to the associated mesentery. Thorough examination of the remainder of the bowel should be performed to rule out and resect any synchronous lesions. Even in metastatic cases, surgery may be necessary, especially for palliation of bleeding, obstruction, ischemia, or other local symptoms related to either the primary lesion or mesenteric metastases. Excision or ablation of liver metastases can be performed to lessen the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. Finally, long-acting somatostatin analogs such as octreotide are used to alleviate symptoms and perhaps slow disease progression.23

Gastrointestinal Lymphoma

Lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal site for non-Hodgkin lymphoma; however, it is usually part of widely disseminated lymphoma with systemic nodal involvement, whereas primary gastrointestinal tract lymphoma is much less common. The incidence has increased over the past century, specifically having doubled in the United States from 1985 to 1990, which is thought to be due to increases in the number of immunocompromised patients as well as immigration from the Middle East.24

Gastrointestinal lymphoma can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, arising from lymphoid aggregates in the submucosa. Distribution varies in different populations. In industrialized nations, the stomach is the most common site, followed by the small intestine and the ileocecal region.25 In the United States, for example, the most common type of primary GI lymphoma is B-cell lymphoma derived from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). In the Middle East and Mediterranean, as many as 75% of the GI lymphomas are located in the small intestine, and are related to immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID). These differ from western MALT lymphomas in that they secrete alpha heavy chains.

Symptomatic Presentation

In the United States, small bowel lymphoma usually presents in the seventh decade of life, with a predilection for men. There are several predisposing conditions, such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), Crohn disease, immunosuppressive medications, radiation therapy, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, and other autoimmune diseases. Low-grade B-cell lymphomas have the best chance of survival, whereas T-cell lymphomas have the worst.26

Gastrointestinal lymphomas are classified as B-cell or T-cell, and low or high grade. The World Health Organization classification system determines treatment based on these criteria.27

Chemotherapeutic, Medical, and Surgical Management of Small Bowel Lymphoma

Treatment is dependent on the type of lymphoma; however, the overall trend is chemotherapy or radiation-based therapy with surgical interventions reserved for complications. Early-stage MALT lymphomas are treated with locoregional low-dose radiation therapy, usually with very good responses. Advanced-stage MALT lymphoma treatment is more experimental, but often treated with a combination of chemotherapy plus immunotherapy such as rituximab. For IPSID, earlier stages are treated with antibiotics, with the addition of chemotherapy and radiation for later stages. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is treated with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), with surgery reserved for complications such as perforation, obstruction, bleeding, or large inflammatory mass. Enteropathy-associated T-cell disease is treated with combination chemotherapy like other high-grade T-cell lymphomas. Primary intestinal follicular lymphoma is a diffuse indolent disease that has been successfully treated with a variety of modalities: watch and wait, radiation, rituximab, and chemotherapy.28 Mantle cell and Burkitt lymphoma are treated with chemotherapy.

Gastrointestinal Sarcomas

Symptomatic Presentation

Sarcomas of the GI tract are malignant mesenchymal tumors, of which GISTs (gastrointestinal stromal tumors) are the most common, making up about 10% of small bowel neoplasms.12,17 Before the understanding of the unique molecular characteristics of GISTs, many of these tumors were classified as leiomyosarcomas in older series. GISTs may appear to be similar to leiomyosarcomas. They are, however, unique in that they express c-kit (the CD-117 antigen), which is related to the KIT tyrosine kinase receptor. A subset of GIST tumors without KIT mutations instead have involvement of another tyrosine kinase, the platelet-derived growth factor receptor α.

Sarcomas of the GI tract usually present in the sixth decade of life, often with GI bleeding as the first symptom. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, weight loss, and less commonly, small bowel obstruction. The majority of these tumors are located in the jejunum, followed by the ileum and then duodenum.29 GI sarcomas tend to spread hematogenously, with most metastases located in the liver.

Surgical and Medical Treatment

The primary modality of treatment of gastrointestinal sarcomas is surgical resection with negative margins. A complete resection including the tumor pseudocapsule is required. Wider resections with negative margins or lymph nodes are of no benefit because nodal metastases are rare. All GISTs <2 cm should be resected; recommendations are conflicting for lesions smaller than this.30 Larger lesions may warrant preoperative treatment with the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, imatinib, if ability to resect is borderline or would require major organ disruption, or if there are high-risk characteristics such as size >5 cm, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power field.31 The tumor should be handled with care so as to avoid tumor rupture, which would increase risk of local recurrence. Adjuvant therapy with imatinib 400 mg daily for 3 years is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence.32

Metastatic Lesions

Metastatic lesions from other organs may spread to the small bowel and are common in the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Other tumors may spread hematogenously, the most common of which is malignant melanoma. Melanotic metastases are often multiple. Other tumors which metastasize to small bowel infrequently include breast, lung, cervix, pancreas, and colon.33 Metastatic melanoma of the GI tract can present with bleeding, obstruction, abdominal pain, or intussusception. Overall survival is poor. However, palliative resections may be considered, and in some cases have resulted in a modest increase in survival.34

Benign Tumors of the Small Bowel

Adenomas

Villous tumors have a more significant risk of malignant transformation. They tend to favor the duodenum, especially near the ampulla of Vater. Superficially, villous adenomas may have histologic appearance of adenoma, but deeper sections may reveal adenocarcinoma. A report of 192 cases of duodenal villous adenoma demonstrated that 42% of adenomas contained a focus of carcinoma at the time of diagnosis. Removal of pedunculated duodenal villous polyps can be done endoscopically, whereas larger polyps may require surgical resection to resect the entire base and address all involved mucosa.35 Villous adenomas in the more distal small bowel, once symptomatic, will require a limited jejuna or ileal resection usually done laparoscopically.

Risk factors for villous adenomas include FAP, with the majority of these patients developing multiple duodenal adenomas, and upper GI malignancy being the greatest cause of morbidity after colectomy.6

Brunner gland adenoma is a rare neoplasm derived from the exocrine glands of proximal duodenum. Endoscopic removal is recommended to prevent complications due to gastrointestinal bleeding. There have been no reports of malignant transformation.36

Desmoid Tumors

Desmoid tumors are rare, benign fibromatous lesions, which have a tendency to occur in as many as 20% of patients with FAP. They can occur in sites of surgical trauma, such as the abdominal wall or mesentery. Although these tumors cannot metastasize, locally they can be highly aggressive and tend to recur after resection.37

Hamartomas

Hamartomas are commonly found in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS). They are composed of proliferations of smooth muscle and can grossly appear either sessile or pedunculated. In one series, 64% of patients with PJS were found to have small bowel hamartomas, although they can be located anywhere from the stomach to the rectum.37

Surgical Considerations: Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection

Historically, all small bowel surgery was done via the open technique using a laparotomy incision. Over the past two decades, more of these cases are being performed by using either laparoscopy-assisted or entirely laparoscopic techniques. Initial diagnostic laparoscopy may also be helpful to survey the abdomen and identify metastatic deposits. It is important when performing minimally invasive surgery to do a true cancer operation by taking the appropriate draining lymph nodes. If this can be accomplished, the tumor may be extracted through a relatively small incision, with less pain, faster return of bowel function, earlier hospital discharge, and earlier return to work.38 Most recurrent tumors generally still require open surgery to obtain adequate margins and lymph node resection.