Cancer of the Penis

Jonathan E. Heinlen and Daniel J. Culkin

• Penile cancer is rare in developed countries, but responsible for a large proportion of solid tumors in males where sanitation and medical care are poor.

• Most penile cancer is squamous cell carcinoma and many are associated with high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) infection.

• Presentation is typically with localized disease with predictable spread to regional lymph nodes preceding widespread metastasis.

• Penile sparing treatment is indicated for minimally invasive disease

• Penectomy remains the standard of care for invasion into corpora or urethra.

• Radiation has a growing role in the treatment of small lesions.

• Lymphadenectomy remains an important element of treatment in men with intermediate- and high-risk disease.

• Sentinel lymph node biopsy is gaining acceptance using newer techniques

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

• Multimodal therapy is investigational for advanced disease.

• Treatment of bladder outlet obstruction is an important consideration

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

• Effective chemotherapy is still elusive, although newer multi-agent regimens hold promise.

Introduction

Penile cancer is an uncommon malignancy. Patients typically present with low-stage lesions, with 3% to 4% presenting with metastatic disease.1,2 Because of the intimate nature of the disease, many men will delay diagnosis and as many as one third of cases manifest with locally or regionally advanced disease. Lesions rarely arise from the shaft of the penis and in 98% of cases originate from the glans, prepuce, or corona.3 From here they progress to local invasion of the cavernosa and metastasize early to the inguinal lymph nodes. The most important factor for long-term survival is disease stage at the time of diagnosis, followed by histologic grade of the tumor. Although penile cancer is a very treatable disease with good prognosis when detected early, advanced penile cancer is associated with poor survival and ineffective systemic treatment options.

Epidemiology

Penile cancer is exceedingly rare in North America and Scandinavia and is far more prevalent in South America, Asia, and Africa. In industrialized nations, penile cancer affects between 1 and 9 per 1,000,000 men. In less developed nations such as sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South America it represents as many as 10% of male malignancies.4 Incidence in Africa and Asia ranges between 10% and 20%.5 Possibly because of improving worldwide health conditions and increasing prevalence of circumcision, the incidence of penile cancer has been decreasing in recent years.6

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

There are many cited risk factors for penile cancer. Risk factors include phimosis, human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, genital warts, cigarette smoking, and trauma or balanitis.3 Twenty-five percent to 60% of penile cancer cases are associated with phimosis.1,7 Phimosis is a known risk factor for invasive carcinoma (OR = 16), but not for carcinoma in situ (CIS).8 Circumcision performed in the first year of life virtually eliminates the risk of invasive penile carcinoma. Older studies have shown that the risk of penile cancer is the same in men who are uncircumcised as in those circumcised after the first year of life.9 Cigarette smoking is a risk factor (OR = 1.44), especially in long-term smokers or those who smoke more than 10 cigarettes daily (OR = 2.1). Chewing tobacco (OR = 3.1) is a greater risk than cigarette smoking.10 History of trauma is a risk factor for CIS and invasive cancer, as is balanitis. Likewise, men with a personal history of anal or genital warts are at elevated risk for the disease (OR = 3.7).8,9

In recent years, infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) has been a subject of investigation as a major etiologic factor for penile cancer. HPV is highly prevalent worldwide in men, with up to 70% of all males infected. Only 10% of men are infected with known oncogenic strains of HPV, however. Men with invasive penile cancer have a 24% to 62% rate of infection with high-risk HPV, whereas controls have a 12% rate. As many as 95% of penile cancers are associated with HPV-16 infection.3,11

Evidence suggests that oncogenesis of penile cancer falls into two pathways—HPV associated and non–HPV associated. HPV associated tumors are much more likely to be of the basaloid or warty subtypes.12 These tumors are similar in nature to tumors arising from the mucosa of the anal and oropharyngeal regions and most frequently occur on the glans.12 Non–HPV-associated cancers tend to be keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), similar to what is seen on nongenital skin and tends to be well differentiated. Up to 30% of these tumors may contain HPV DNA but it is uncertain if HPV plays an etiologic role in these tumors. Non–HPV-associated cancers tend to be associated with chronic inflammatory skin conditions such as lichen sclerosus.

Little is known about molecular alterations common in penile carcinoma owing to its rarity as well as its association with concomitant infection and inflammation. Observations have been made regarding certain DNA copy number gains (8q24, 16p11-12, 20q11-13, 22q, 19q13, 5p15) and deletions (13q21-22, q21-32).13 Increasing aneuploidy appears to be associated with a high risk of invasive cancer.14 E6, the oncogenic product of HPV, is known to bind to p53, causing suppression of its normal cell cycle inhibitory function. This results in increased cell proliferation, decreased apoptotic control, and loss of differentiation. As such, the relationship of p53 expression to penile cancer prognosis has been investigated with contradictory results. Alternately, a positive or negative relationship between p53 expression and HPV infections has been seen. It has been suggested that late alteration of p53 may be associated with disease progression and metastasis.15

Other HPV-associated pathways and genes that have been investigated include p16INK4a/cyclin D/retinoblastoma, c-RAS, MYC, PIK3CA, PTEN, BRAF, HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS. The general observation is that larger and more advanced tumors are associated with mutations in more of these pathways. HPV18 has been found in metastatic tumor linked to p53 and c-ras mutation.15 DNA methylation has been evaluated in penile cancer and hypermethylation found in DAPK, HIT, MGMT, p14ARF, p16INK4a, RAR-B, RASSF1A, and RUNX3.16 In another study, methylation of TSP-1 was associated with poorly differentiated tumor and increased risk of vascular invasion.17

Prevention and Early Detection

Circumcision is a divisive topic in the medical literature, with strong proponents both for and against routine circumcision. Many political authorities are withdrawing public funding for circumcision based on evaluation of cost-effectiveness in preventing disease. Also, opponents of circumcision argue that the procedure is primarily cosmetic and is performed without the assent of the patient.18 A recent meta-analysis suggests a significant decrease in the likelihood of developing invasive penile cancer in patients who underwent childhood or adolescent circumcision (OR = 0.33).19 Also, regardless of the direct goal of preventing penile cancer, circumcision reduces the transmission of high-risk HPV by up to 35% and of HIV by up to 60%.19

Although HPV appears to have a significant role in the development of penile malignancy, vaccination of men against HPV for penile cancer prevention is considered unreasonable because of the low incidence of penile cancer. Many other cancers in both men and women, however, are associated with high-risk HPV, and some groups have proposed increased efforts to vaccinate against HPV on the basis of herd immunity.20 In 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization of all males of age 11 or 12 with the HPV4 vaccine on the basis of risk reduction for anal, pharyngeal, and penile cancer and to prevent genital warts.21

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Leukoplakia

Leukoplakia is a disease seen primarily in diabetic men. Perimeatal blanched plaques and/or scaled areas are seen that extend into the urethral meatus. Microscopically the appearance is consistent with acanthosis, parakeratosis, and hyperkeratosis. Leukoplakia can be seen in proximity to malignant lesions and is a response to recurrent inflammation or irritation. It is not, in and of itself, proved to be a premalignant condition. Because of its association with comorbid malignancy, however, treatment is excision or biopsy followed by close follow-up. Up to 20% of men with leukoplakia have been shown to eventually develop penile cancer.22 Extensive lesions have been treated successfully with bleomycin.23

Penile Lichen Sclerosus (et Atrophicus)

Widely known also as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA) of the penis is a disorder primarily affecting the glans, prepuce, and urethra. This is seen almost exclusively in uncircumcised boys and men and circumcision is often curative. Although most often a complaint of middle-aged men, epidemiological data support diagnosis at any age in males from 2 to 90.24 BXO manifests as ivory-colored sclerotic plaques on the glans and inner prepuce. These are often pruritic in nature. They are grossly and histologically distinct from leukoplakia. Microscopically there is marked fibrosis, epidermal atrophy, interface dermatitis, and dermal edema. Patients may experience painful erections—particularly a burning sensation when the phallus is engorged, phimosis, or dysuria. In advanced disease, sexual intercourse can cause fissuring and blistering.

Penile LSA may play a role in the development of SCC. Malignancy has been observed in 2.3% to 5.8% of patients.25 Etiologic associations of BXO include HPV, particularly serotype 16, spirochetes, and atypical mycobacteria.24 First-line treatments for BXO are topical steroids and/or circumcision, though it is not known whether treatment for BXO has a preventative role for the development of penile SCC.

Carcinoma In Situ

CIS of the genitalia is named differently depending on the location of the lesion. A sharply demarcated, shiny, raised erythematous plaque of the nonkeratinized glans or mucosal surface of the prepuce is called erythroplasia of Queyrat (EQ). Bowen disease (BD) describes the same histologic entity presenting as red scaling patches on the keratinized genital surfaces such as the penile shaft, scrotum, or perineum.26,27 Unlike BXO, these lesions are definitely considered premalignant or malignant because of a progression rate to SCC of 10% to 30%.28 EQ and BD tend to be diseases of older men with the most common diagnosis in the fifth decade. Bowen disease typically involves the epithelial cell layers of hair follicles with a very similar histologic appearance to EQ. When found on the penis, this lesion often appears as a scaling plaque without notable erythema and signifies the presence of CIS. Only about 1 lesion in 10 will progress to invasive carcinoma, a rate that is comparable with EQ.

Histologically, these lesions demonstrate diffuse changes throughout the squamous epithelial cell layers including keratinocyte hyperplasia, nuclear atypia with many mitoses, proliferation of enlarged hyperchromatic cells, multinucleated cells, and loss of polarity within most cells. Presence of inflammatory cell infiltration and increased density of microvasculature is common. Similar to invasive penile carcinoma, links to HPV infection have been investigated and have shown association with many of the same viral strains.29,30 A small study of EQ identified DNA from HPV type 8 in every sample of penile CIS, whereas this viral DNA was not identified in any samples of BD lesions. In addition, HPV type 16 was found in more than 80% of BD samples.30

Bowenoid Papulosis

Bowenoid papulosis (BP) is markedly different from EQ and BD in presentation, demographics, and clinical course. Men who have BP are much younger than EQ and BD patients, with a mean of about 30 years of age.31 These lesions are groups of scaling, erythematous papules typically seen on the keratinized skin of the penile shaft. Histologically, the cellular morphology mimics CIS, but the keratinocytes tend to be slightly more differentiated than those seen in CIS. In addition, histologic sections of bowenoid papules demonstrate that the more atypical-appearing cells tend to be found among the top epithelial cell layers and in the upper portion of the sweat glands. Because of histologic similarities, a physician must combine the clinical presentation and the histologic findings in order to confidently arrive at the diagnosis.26

The etiology of BP is still unclear. Investigations into the viral etiology of BP have provided increasing evidence to support a link to HPV subtypes (6, 11, 18, 42, 43, 44).32 Progression of BP to SCC has been reported in lesions with high-risk HPV strains.33 There have been other reports of malignant conversion as well.34 Spontaneous regression has also been reported.35

Recently, treatment for BP has consisted primarily of topical therapy including 5-FU, imiquimod cream, and cidofovir in immunocompromised patients.36 Historically, these lesions have been surgically excised and results with laser and other forms of ablative therapy have been mixed.37 Often, topical and extirpative therapy can be used in combination with good results.

Buschke-Lowenstein Tumor (Verrucous Carcinoma)

Commonly known as verrucous carcinoma or giant condyloma acuminatum, Buschke-Lowenstein (BL) tumors are very similar in appearance to benign condyloma venereatum. Unlike their benign counterparts, BL tumors tend to invade tissue and cause significant damage. The rete pegs of these lesions are often seen penetrating deeply into surrounding tissue. This aggressive behavior is in contrast to the well-differentiated cells that compose BL tumors; cellular anaplasia is very atypical in these specimens. A viral etiology appears to play a role in the development of BL tumors. Investigators have found associations with HPV strains 6 and 11.38 Despite the local tissue destruction commonly found with these tumors, metastatic progression of the tumor does not occur. Therefore local control is the primary objective and may require partial or total penectomy. To date, no large-scale trials of topical or radiation therapies have shown efficacy. A report of BL tumor regression after treatment with intralesional injection of interferon-alpha suggests that local nonexcisional therapy directed at the viral etiology may hold promise for future nonexcisional treatment. Use of systemic chemotherapy with bleomycin, methotrexate, and cisplatin has been reported to achieve regression of BL lesions. However, given the toxicity of these agents, this approach is not routinely advocated for this disease.39,40 CO2 laser ablation has also been shown to have a role in local control of this disease.41

Nonsquamous Malignancy

Penile tumors not arising from squamous epithelium are rare, comprising fewer than 5% of tumors. The most common nonsquamous malignancy is sarcoma. Other known malignancies include melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and lymphoma. With the increasing prevalence of HIV and AIDS, the incidence of Kaposi sarcoma has risen; nearly 20% of patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma have a lesion on the genitals.42 Most of these appear on the scrotum or perineum and only a small percentage of these patients present with a penile lesion. The gross appearance of Kaposi sarcoma is of erythematous nodules, with sharp margins found most often on the glans penis. Standard treatment includes local excision, laser ablation, or palliative radiation.43

Basal cell carcinoma of the penis most often is found on the penile shaft, with only a small fraction of cases reported on the prepuce or glans.44 Appearance of this tumor on the scrotum or perineum is less common. The typical appearance of basal cell carcinoma of the penis is a well-circumscribed lesion with clear borders and central pitting. Given the slow rate of growth and lack of metastasis, local excision is often curative.44

In contrast, melanoma of the penis carries a very poor prognosis. Almost 40% of patients present with regional lymph node metastasis.45 Two of every three lesions are found on the glans. Wide local excision with a 3- to 5-cm margin is the treatment of choice for lesions less than 1.5 mm Breslow depth.45 Bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection has been the standard of care of lesions more than 1.5 mm thick.45

Far more unusual tumors have been cited in sporadic case reports. These tumors include penile schwannoma, plexiform neurofibroma, vascular hemangioendothelioma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and synovial sarcoma.46–52 Generally, the prognosis of these tumors is similar to the outcomes of these malignancies when identified elsewhere in the body.

Extramammary Paget disease is a very rare penoscrotal neoplasm, and distinguishing this lesion from EQ or BD is clinically impossible. Histologically, it is diagnosed by the presence of large, clear staining cells with hypochromatic nuclei within the epidermis called Paget cells. This disease is seen in older men and appears as a well-demarcated, erythematous, eczematous lesion. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes occurs very rarely. It is considered the etiology of adenocarcinoma in situ of the epidermis. This entity arises from pluripotent intraepidermal cells undergoing malignant transformation during apocrine differentiation.53 Clinical suspicion for underlying genitourinary malignancies should be very high because 16% to 33% of patients with penoscrotal Paget disease have concurrent internal genitourinary carcinoma.54,55 Historically, patients with extramammary Paget disease were evaluated extensively for occult pulmonary and gastrointestinal malignancy. However, retrospective analysis of patients with penoscrotal Paget disease reveals that 92% of those with associated malignancy have genitourinary pathology.53 Treatment generally consists of wide local excision that typically requires coverage of the defect with skin grafting or tissue flaps.53 Mohs micrographic surgery has been recommended as the therapy of choice because of the very high incidence of positive margins using standard surgical techniques.56 Nonexcisional treatments have been described, but these isolated reports do not provide enough data to evaluate for efficacy.57 Recurrence in these patients is very common and close follow-up is recommended.

Metastatic Tumors

Secondary tumors of the penis from metastatic nonurologic primary malignancies are rare, with less than 500 reported cases.58 Metastatic tumors to the penis are most often found in the presence of advanced systemic carcinoma. The index of suspicion for penile metastasis should be high in patients who have a known malignancy and subsequently suffer from priapism or complain of a new penile lesion. The common presentation of a penile metastasis is multiple nodules along the penile skin with occasional ulceration that may have the appearance of a syphilitic chancre. These lesions typically are not painful. Almost 50% of patients will have extensive involvement of the corpora cavernosa, which accounts for the common presentation of priapism.59

The primary tumors that frequently metastasize to the penis are prostate, bladder, renal cell, testis, and rectal carcinoma.58,59 The prognosis is dismal with less than 6 month survival for these patients. Treatment should be with systemic chemotherapy or local radiotherapy with surgical treatment reserved for palliation.60

Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Over 95% of primary penile tumors are SCC. Unfortunately, more than half of patients will have invasive disease at the time of diagnosis.3 This malignancy can arise anywhere on the penis, but fewer than 20% of tumors originate proximal to the foreskin and glans. Fifty percent of tumors arise on the glans itself, 20% on the foreskin, and 10% involve both the glans and foreskin.3

Metastasis of penile SCC occurs first in the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, with risk of lymphatic spread related directly to tumor size and grade.61 The lymphatic drainage is unpredictable, meaning that it cannot be accurately assessed based on tumor location which side lymph nodes might be involved, necessitating treatment of both inguinal lymph node beds when indicated. Small tumors of the glans and prepuce are very rarely metastatic at presentation; however, tumors involving 75% of the penile shaft or more are almost always metastatic.62

Penile SCC is graded using the Broder scale to quantify the degree of tumor cell differentiation.62a Half of all lesions are either grade I or II at diagnosis. Histologically, these tumors have a hyperkeratotic dermis with cords of carcinoma cells extending into deeper tissue layers. There are also intercellular bridges, keratin, and keratin pearls prominent throughout the specimen. More than 50% of tumors that arise on the penile shaft tend to be high grade, whereas only 10% of preputial SCC demonstrate poorly differentiated histology.3

Other grading systems have been developed to improve the reproducibility of the Broder classification. Factors that influence grading in these systems are the number of mitotic cells per high-power field, degree of keratinization and cellular atypia, and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the tumor. Each parameter is assigned a score and these are then summed to give a grade. Application of this system revealed 80% survival among patients with low-grade tumors.63 Another technique for correlating histology and survival classifies tumors based on superficial spread, vertical growth, verrucous features, and multicentricity. These categories revealed metastatic disease in 42%, with superficial disease and 82% with vertical tumor growth.64 Other features studied for prognostic significance include ulcerative versus exophytic appearance. Exophytic tumors have a high degree of keratinization on histologic examination with cells that appear more differentiated. Conversely, ulcerative penile malignancy is more often poorly differentiated with a higher incidence of lymph node involvement.5 Sarcomatoid differentiation is a very poor prognostic indicator, with up to 89% chance of lymph node involvement at presentation.65

The disease ultimately progresses to invasion and local tissue destruction with eventual invasion of the corpora and urethra causing urinary obstruction. Metastasis occurs with invasion of the lymphatic bed of the prepuce and penile skin. These empty to the penile base and then to both inguinal node clusters. The anatomy of lymphatic drainage has complicated efforts to develop reliable sentinel node biopsy techniques. Once the superficial lymphatic system is entered, tumor spreads to the deep inguinal nodes under the fascia lata and medial to the femoral vein. The lymphatic system for the glans, urethra, and corpus spongiosum are variable and may seed the superficial or deep inguinal nodes. Drainage is very rarely to the external iliac node complex. Metastatic disease to the iliac lymph nodes portends a high probability of distant lymphatic and nonlymphatic spread. Distant metastasis to liver, lungs, and bones are signs of advanced disease and carry a very poor prognosis. Fortunately, fewer than 5% of patients have clinically evident distant metastasis at diagnosis.3

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

Penile SCC most commonly begins as a painless lesion on the glans or prepuce. Generally, this is a disease of older men in their sixth or seventh decade. Clinical suspicion in younger patients is warranted, however, as many such cases have been reported.66,67 Lesions vary in presentation from the innocuous appearing bump with slight induration and erythema to the obviously malignant fungating penile tumor that leads to auto-amputation. Though typically nonpainful, infection and involvement of deep structures can cause pain. Most lesions are firm and indurated and may be exophytic or ulcerated. Phimosis may obscure early tumors and delay diagnosis for as much as a year.68 Chronic malodorous discharge from a phimotic foreskin should raise suspicion for occult tumor. Other signs of occult tumor are bleeding due to invasion of deep penile structures, urethra-cutaneous fistula, and distortion of basic penile morphology.

Inguinal lymphadenopathy is a common finding at diagnosis, with nearly 60% of patients having palpable inguinal lymph nodes. Many of these patients have concomitant infections that are responsible for the inflammation of the inguinal nodes and this adenopathy will subside with appropriate treatment. More ominously, one in five patients with clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes will have microscopic evidence of metastatic disease.5

Although many staging systems have been used, current staging of penile carcinoma follows the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system that incorporates tumor invasion, local node involvement, and the presence of distant metastases (TNM) to stratify patients based upon prognosis (Table 85-1).69 This staging system continues to evolve, as it has recently been reported, for instance, that corpus spongiosum involvement is prognostically better than corpus cavernosum involvement.

Table 85-1

TNM Staging of Penile Cancer119

| Tumor | Nodes | Metastasis |

| Tis: Carcinoma in situ | cN0: No palpable nodes | M0: Absence of metastasis |

| Ta: Verrucous carcinoma, noninvasive | cN1: Mobile, palpable, unilateral node | M1: Presence of metastasis |

| T1: Invades subepithelial connective tissue | cN2: Mobile, palpable, multiple or bilateral nodes | |

| T2: Invades corpora cavernosum or spongiosum | cN3: Fixed inguinal or pelvic nodes, unilateral or bilateral | |

| T3: Invades urethra | pN0: No regional nodal metastasis | |

| T4: Invades other adjacent structures | pN1: Single inguinal lymph node | |

| pN2: Multiple inguinal lymph nodes | ||

| pN3: Pelvic lymph nodes or extranodal extension of inguinal lymph nodes |

The importance of physical examination in the setting of suspected penile malignancy cannot be overstated. Thorough evaluation will provide valuable information regarding the stage of the cancer. Physical exam is remarkably reliable for predicting involvement of corpora, and tumor size, which is linked closely to prognosis, is quickly assessed. Patient counseling regarding the expected outcome of surgery is done primarily on physical exam. As the presence of corporal invasion (T2) is a determining factor in the use of penile sparing techniques, particular attention has been paid recently to penile MRI to detect involvement of the corpora cavernosa and spongiosum. Sensitivity ranges from 75% to 88% and specificity 83% to 98% for accurate detection of T2 disease. Noncontrast MRI seems to be as effective as enhanced MRI in delineating corporal invasion; however, detection of more advanced disease is improved with the use of contrast.70 Pharmaceutically induced erection using alprostadil improves detection over flaccid MRI.70

The presence of palpable inguinal adenopathy at the time of diagnosis is an important concern; however, the role of infection of the tumor is often confounding to the determination of malignant lymph node involvement. The presence of matted, bulky nodes is strongly suggestive of progression to pelvic lymph node involvement.71 After treatment for T1 tumors, many practitioners advocate a long course of antibiotic therapy followed by reevaluation of nodes prior to making a clinical decision for lymphadenectomy.

Pathological T stage and tumor grade are important predictors of lymph node metastases, with a reported incidence of 19% to 29% for grade I, 46% to 65% for grade II, and 82% to 85% for grade III penile SCC.72 Patients with pathological T2 disease or higher have an ~15% to 25% chance of harboring disease in clinically nonpalpable lymph nodes. For this reason, it is often desirable to stratify those patients with clinically nonpalpable nodes using minimally invasive techniques prior to pursuing potentially morbid lymphadenectomy.

Some investigators have proposed cytologic aspiration or CT-guided biopsy of suspicious nodes to aid in the decision to excise lymph nodes. Others use ultrasound guidance for needle aspiration of lymph nodes, citing the ability of good ultrasonographers to reliably show changes in the nodal architecture that might suggest the presence of malignancy.73 Work with vulvar cancer that has a similar lymphatic drainage quotes a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 100% respectively in a series of 44 patients.74 In the past, the considerable false-negative rate with aspiration cytology has limited the clinical usefulness of this procedure.75,76

Dynamic sentinel lymph node biopsy (DSNB) has seen widespread use in breast cancer staging and treatment. Even prior to the use of sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer, it was investigated for penile cancer staging. In the original inception of sentinel lymph node biopsy for penile cancer, the false-negative rate was thought to be unacceptably high. Newer techniques using a combination of radiotracers and dye as well as the addition of real-time ultrasound have decreased the false-negative rate from 19.2% to 4.8%.77 Timing has been shown to be important, with a 7% complication rate inside of 30 days from initial penectomy and 1% after that initial window.78

Imaging using CT and MRI has been shown to be nearly useless in ruling out disease in patients with nonpalpable adenopathy. Positive predictive value for nodal metastasis is as high as 100% when features such as size >1.5 cm, nodal necrosis, presence of irregularity, and evidence of local tissue infiltration are used. This holds true for pelvic nodal assessment, with the exception of the size criteria.79 On MRI, the signal intensity of lymph nodes can be compared with that of the primary tumor, and similarity should raise suspicion even when enlargement is not present. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) has been evaluated in small studies and found to have sensitivity of 91%.80 The resolution of even the most modern CT scanners, however, limits the usefulness of CT in detection of clinically negative nodes. Nanoparticle enhanced MRI uses an infusion of iron oxide particles, which are taken up homogenously by functioning macrophages in normal nodes and provide low signal on gradient T2 images. Metastatic nodes, lacking normal function, do not take up this agent and therefore have a comparatively high signal intensity. On the basis of 10 patients, this was evaluated node for node and found to have a 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity compared to the pathological results after lymphadenectomy. The technique is also being investigated for use with other tumors but as of this writing does not have FDA approval.81,82

Primary Therapy

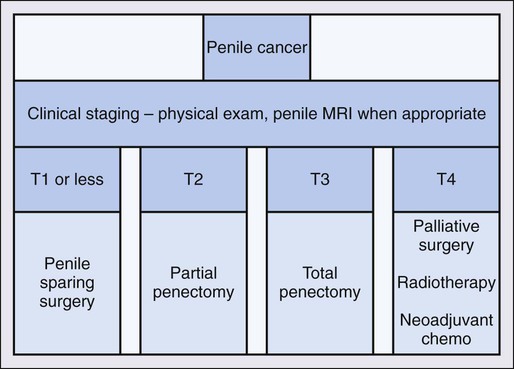

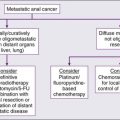

Therapy for penile cancer focuses on treatment of the primary tumor as well as the regional lymph nodes (Figure 85-1). Historically, penectomy, either partial or total, with 2-cm margins has been the mainstay of treatment for the primary lesion. Despite traditional wide margins, a margin of only a few millimeters appears to offer good local control.83,84 More recently, the role of penile sparing techniques have been investigated with encouraging results. Penile sparing is now considered standard for T1 tumors, with low-grade histology and select patients with T1 tumors and intermediate or high grade.

Penile Sparing Management of Penile Cancer

The psychological impact of penectomy is significant and must be discussed in detail with patients prior to offering treatment for penile malignancy. Patients without cavernosal involvement of the primary tumor (<T2) may be offered penile sparing as long as they do not have multifocal disease, as this may make reconstruction difficult or impossible. Patients with T2 disease limited to the glans may undergo glansectomy with resurfacing of the corporal heads, which does not appear to worsen prognosis. Options for penile sparing in T1 disease include laser ablation, 5-FU, local excision and/or circumcision, Mohs micrographic surgery, and for tumors that are very superficial, photodynamic therapy may be an option. Intraarterial targeted chemotherapy has been explored for clinically localized disease in small series with good results.85 Radiation by external beam or with brachytherapy for the primary tumor have been reported, again, with good results.86

Recurrence after local treatment should prompt investigation for corporal involvement with biopsy, physical exam, or potentially penile MRI. If the tumor remains clinically noninvasive, it is reasonable to repeat treatment with penile sparing technique. Consideration of wider margins of treatment should be made regardless of approach as it has been shown that microscopic extension of the primary tumor may occur 5 mm beyond the gross margin.84

Management of Locally Advanced Disease

Tumors that invade the corpora cavernosa or spongiosum require more aggressive therapy. Partial penectomy with a 2-cm margin has been the standard treatment, though some have concluded that a 5-mm margin is safe.87 The goal of partial penectomy is to allow a useful penile length while removing all of the primary tumor. Creation of a widely spatulated neomeatus is a key principle of the surgery to avoid all too common urethral stricture after reconstruction.88 About 50% of men report erectile function after partial penectomy that is sufficient for intercourse.89

Treatment of Associated Inguinal Lymphadenopathy

Excision of inguinal metastasis has a clear survival benefit. Patients with known nodal metastasis have a 5% survival rate in 3 years without treatment. Conversely, patients with node-negative disease have a 77% survival rate at 5 years.90 The most important prognostic factor for predicting nodal involvement is the depth of invasion of the primary tumor. Superficial disease or T1 lesions have a very low rate of metastases to the inguinal region. Half of patients with corporal involvement will have lymph node metastasis, whereas more than two thirds of patients with T4 disease do.91

Extent of lymph node involvement also has prognostic significance because 5-year survival decreases in conjunction with increasing number of involved lymph nodes. Patients without nodal involvement have an excellent 5-year survival rate of 95%, but only 81% of those with up to 3 positive lymph nodes will be alive after the same period. Patients with more than three malignant lymph nodes have a 50% mortality rate and no patients with pelvic nodal metastases are alive after 5 years.92 Several series confirm these findings with a 93% 5-year and 84% 10-year survival rates in node-negative disease but 62% survival for N1 and N2 patients in the same period.93

The most reliable method for determining regional node status is ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy. The procedure is associated with the possibility of significant morbidity including lymphedema, lymphocele, and wound infection and breakdown. Authors have shown that lymphadenectomy in high-risk patients improves survival when at least 8 nodes are removed.94 Considering the high stakes, many authors advocate lymphadenectomy in all patients with high-risk primary tumor pathology. Advocates of DNSB have shown that though 23% of patients with a negative sentinel node will ultimately develop nodal metastasis in follow-up, 77% of patients with a negative sentinel node will be saved a potentially debilitating surgery.95 There is no debate, however, that patients with bulky nodal disease should undergo lymphadenectomy.

Superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy is performed on patients with T2–T4 disease and either clinically negative or minimally palpable lymph nodes. Patients undergoing superficial dissection should have an intraoperative frozen section to determine the need for deep dissection beneath the fascia lata. The incidence of “skip” lesions is negligible, so in the presence of a negative superficial lymphadenectomy, there is no clear indication for deeper dissection and therefore higher morbidity. Involvement of two or more nodes with metastatic disease is an indication for dissection of the deep inguinal lymph nodes.96 Technical considerations are to leave the adipose layer superficial to Scarpa’s fascia intact and to leave the saphenous vein intact if possible. This decreases the likelihood of flap necrosis and epidermolysis. Limiting anatomic borders to 2 cm above and 10 cm below the inguinal ligament and meticulous surgical technique have led to significant improvement in morbidity of the modified superficial lymphadenectomy with an overall complication rate of around 15%.97

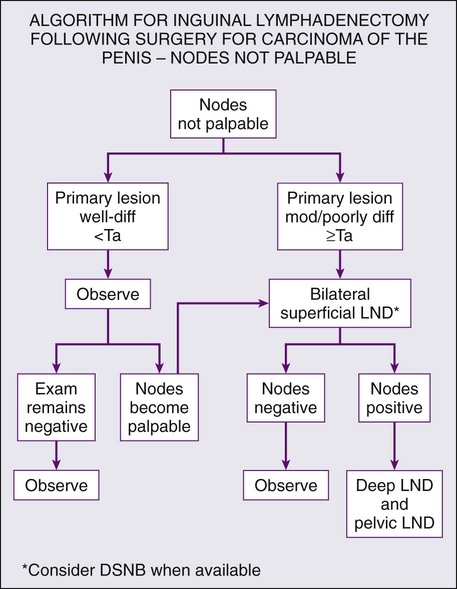

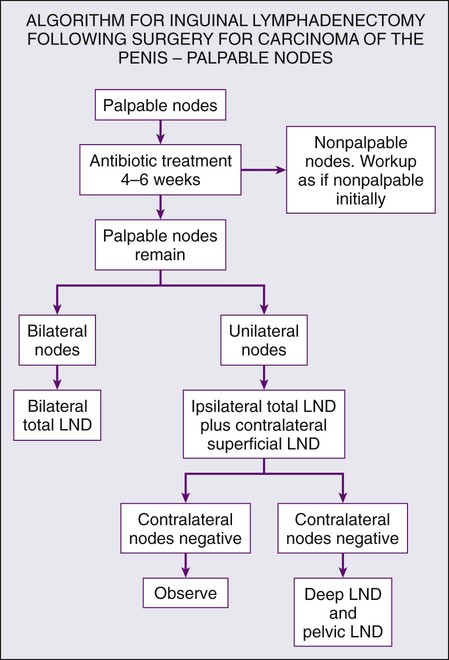

Radical inguinal lymphadenectomy extends the dissection from the sartorius to the adductor longus and from the inguinal ligament to the apex of the femoral triangle. The fascia lata is incised and the saphenous vein is ligated. The vascular sheath of the femoral vessels is incised to ensure removal of all lymphatics encasing the vessels. This procedure is indicated when nodes are clinically bulky or when superficial inguinal dissection is positive for multiple metastatic nodes. The greatest challenge in radical inguinal lymphadenectomy is coverage of the femoral vessels and reconstruction of the inguinal area. In cases where nodes are ulcerated or involve the skin, wide excision with a 3-cm margin is indicated that invariably requires creation of a wide flap for adequate coverage. Graciles, rectus abdominal, and tensor fascia lata flaps are all described to augment or improve coverage and local healing. The surgeon must also be prepared to deal with the sequelae of vascular invasion and the possibility of control and reconstruction of the femoral vasculature. As expected, given the radical nature of the procedure, complications of deep inguinal lymphadenectomy are frequent and severe. Summary of recommendations for lymph node management are provided in Figures 85-2 and 85-3.

Radiation Therapy

Studies on the efficacy of radiation therapy as a primary treatment have shown promise, especially in tumors less than 4 cm.86,98,99 Disease-free rates range from 70% to 90% and penile sparing is achieved in 80% of men.99 Brachytherapy—with the use of radioactive seeds—has efficacy as well as external beam radiation or a combination of both when total dose exceeds 60 Gy. Complications include urethral stenosis, necrosis of the glans, and fibrosis of the corpora. Currently, there are no studies comparing the efficacy of radiotherapy with surgery.86,98,99

Multimodal Therapy

Patients with inoperable lymphadenopathy or locally advanced disease may be candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Leitje et al. reported on 20 patients who had undergone chemotherapy prior to surgical resection of tumor including several different cytotoxic regimens and surgical approaches. Nine had sufficient response to proceed with surgery and of them 8 experienced long-term survival with no evidence of disease.100 Pagliaro et al. report 30 men who underwent cisplatin, ifosfamide, and paclitaxel treatment prior to resection of bulky adenopathy. Twenty-two patients proceeded to surgery and 9 (30%) were without evidence of disease. Three patients had a complete pathological response.101

Small, uncontrolled studies suggest that the addition of chemotherapy to radiation may offer more promising results than radiation alone.102 Bleomycin in combination with radiation has been contrasted to surgical intervention and has shown similar 3-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates.103 This report compared 19 patients who underwent surgery with a cohort treated with a combination of bleomycin and radiation. Methotrexate, 5-FU, and cisplatin have also been reported to have responses in advanced penile cancer when combined with radiotherapy. These early findings provide hope that multimodality strategies may decrease the extent of surgical resection, improve long-term outcome, and perhaps even offer organ preservation. Gotsadze reported on 223 patients who received either chemotherapy, radiation, or both for the primary lesion. There was no statistical difference in local control between groups, and the 5-year survival rate was 78% to 88%.104

Multimodal therapy for advanced disease with organ-sparing intent has focused primarily on the combination of radiation with bleomycin, a known radiosensitizer. Many patients reported in the literature had relatively low-stage disease. Edsmyr et al. treated 47 patients with T1–T3 penile cancer with bleomycin and radiation. Two of the 7 patients treated at the lower dose of radiation required subsequent surgical salvage and all 7 remained alive and disease-free at 7 years or greater. Similar favorable results were reported in patients treated at the higher radiation dose, with 10% requiring surgical salvage. Little toxicity was reported.103

In a smaller study, Perez-Tamayo et al. reported a considerably less favorable experience. Ten patients with T1 and T2 N0 penile cancer received bleomycin with external beam radiation. Eight of the 10 patients had moderate to severe toxicity and there was 1 treatment-related death. The goal of penile preservation was achieved in 4 patients (40%).105 Modig et al. reported on 25 patients with T1 penile cancer treated with 56- to 58-Gy radiotherapy and concurrent daily bleomycin totaling 70 to 140 mg. At greater than 8 years of follow-up, 5 patients had local recurrence and none had died of penile cancer.102

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

When inguinal dissection is forgone because of the presence of distant metastases, there remains the possibility of skin ulceration and superinfection of nodal metastases. Treating physicians should also be aware of the risk of femoral vessel disruption and occasional dramatic exsanguination. In these cases, treatment with an in situ graft is not often successful because of the likelihood of infection. Extraanatomic bypass has been described,106 but data are scarce.

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

Although available data remain scant, single-agent chemotherapy as well as multiagent regimen combinations have some evidence of activity for this disease. Chemotherapy has also been combined with surgery and/or radiation in an effort to develop multimodal therapy for penile cancer. Use of single-agent chemotherapy as treatment for local control of penile lesions has shown to produce complete response in some patients; however, this is not usually a durable response.107 Intraarterial chemotherapy has been investigated by some authors and is generally reserved for attempted downstaging of primary tumors to allow for some degree of penile preservation.85,108–110 Agents with established activity in penile cancer include bleomycin, methotrexate, and cisplatin. Combination chemotherapy regimens evaluated to date include cisplatin/5-FU, cisplatin/bleomycin/methotrexate, and vincristine/bleomycin/methotrexate. Many available reports are difficult to interpret because of small sample size, variable patient selection, and variable doses and schedules. Many newer agents have not been studied in penile cancer to date. In recent years, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been investigated for downstaging of unresectable tumors prior to surgical consolidation.110

Single-Agent Chemotherapy

Single-agent chemotherapy with bleomycin, methotrexate, and cisplatin has modest activity in advanced penile cancer. Overall response rates with single agents have been disappointing. Bleomycin produced a 21% overall response rate at the cost of severe pulmonary toxicity that limits cumulative dosage to 400 Units.111 Methotrexate had a better overall response rate (54.5%); however, the median duration of response was only 3 months.112 Cisplatin has been investigated in multiple studies with an overall response of 17.5%. Renal toxicity necessitated discontinuation in 8% of study participants.113

Cisplatin and 5-FU

Hussein et al. reported 6 responses (1 CR and 5 PRs) in 6 previously untreated patients who received a similar regimen.114 No patient had a pathological CR. Patients were treated with surgery or radiation after chemotherapy. All patients ultimately progressed with a median time to progression of 12 months and a median survival of 16 months. Shammas et al. described 2 responders among 8 chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-naïve patients treated with the same regimen.115 The differences in results reported by these groups may be due to patient selection, variable chemotherapy delivery, and/or chance, considering the small sample sizes. These data suggest that cisplatin with 5-FU has significant activity for SCC of the penis, although observed responses lack durability. Reported complications included nausea and vomiting, mucositis, renal insufficiency, infections, alopecia, and ototoxicity. Fatigue and general decline also limited this therapy, particularly in elderly patients.

Cisplatin, Bleomycin, and Methotrexate

This combination showed promising preliminary results in a single-institution trial. A total of 14 chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-naive patients were treated. Ten of the 14 of patients responded (72% response rate, 2 CRs and 8 PRs) with a median response duration of 5.9 months, whereas 1 patient remaining disease-free after 24 months of follow-up.116 A confirmatory trial, which was the largest multiinstitutional prospective clinical trial ever performed in penile cancer, was reported by SWOG.113 This study showed a response rate of 32.5% (5 CRs and 8 PRs in 40 evaluable patients) but toxicity was formidable, with 11% treatment-related mortality and 17% of the remaining patients experiencing life-threatening toxicity. Of the 5 treatment-related deaths, 1 was due to infection and 4 were due to pulmonary complications. Later follow-up studies suggested that observed responses were not durable in nature.117

Vincristine, Bleomycin, and Methotrexate

Vincristine, bleomycin, and methotrexate (VBM) has been studied for advanced penile cancer with a reported response rate of 53.8%.118 A total of 13 patients with unresectable inguinal metastases were treated. There were 7 cases of a PR, of which 5 could be radically resected after chemotherapy. Two of these 5 patients (15% of the whole group) were long-term survivors without disease after 5 and 13 years of follow-up. Lejite et al. saw 3 partial responses in 5 patients treated for the purpose of neoadjuvant consolidation.110 Treatment was generally well tolerated, although fever, lung fibrosis, and skin hyperpigmentation were seen.

Controversies, Problems, Challenges, Future Possibilities, and Clinical Trials

The role of lymphadenectomy and dynamic sentinel node biopsy remains a topic of wide debate. Despite the clear role of lymphadenectomy in survival of patients with penile cancer, only 25% of patients undergo the recommended treatment in the United States.94 Factors influencing this trend are the rarity of the disease, hesitancy of patients to undergo morbid treatment without clinically apparent disease, and unfamiliarity of surgeons with the procedure. The data on DSNB is a mixed bag—although many patients are saved from a potentially debilitating procedure, the nearly 25% false negative rate in high-risk patients means that the remaining patients must remain on close surveillance for several years, which bears a not insubstantial cost and psychological impact to the patient.

The development of novel agents for treatment of metastatic disease is underway. Neoadjuvant treatment with an ifosfamide-based regimen has shown promise, though data for its use as palliative chemotherapy are not yet available.101 Multimodality treatment will continue to be an area of interest, particularly neoadjuvant chemotherapy for lymphadenectomy. Brachytherapy for penile sparing of locally advanced tumors holds promise and bears further investigation.