Cancer of the Central Nervous System

Jay F. Dorsey, Andrew B. Hollander, Michelle Alonso-Basanta, Lukasz Macyszyn, Leif-Erik Bohman, Kevin D. Judy, Amit Maity, John Y.K. Lee, Robert A. Lustig, Peter C. Phillips and Amy A. Pruitt

• An estimated 66,290 new primary tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) will be diagnosed in the United States in 2012, of which approximately one third will be malignant.

• An estimated 4200 new childhood (ages 0 to 19 years) primary benign and malignant CNS tumors will be diagnosed in 2012. Brain tumors are the second most common malignancy among children, second only to leukemias.

• Radiation exposure is the best established risk factor for brain tumors. Hereditary syndromes including neurofibromatosis type 1 and 2, tuberous sclerosis, von Hippel–Lindau, and Li-Fraumeni are associated with higher risk of brain tumors.

• Taking all age groups into account, histologic types of CNS tumors include meningiomas (35%), glioblastomas (16%), other astrocytomas (7%), tumors of cranial and paraspinal nerves ( 9%), tumors of the sellar region (14%), oligodendrogliomas (2%), ependymomas (2%), and embryonal tumors including medulloblastomas (1%).

• Among children 14 years or younger, histologic tumor types include pilocytic astrocytomas (17%), glioblastomas (3%), other astrocytomas (9%), ependymomas (6%), oligodendrogliomas (1%), embryonal tumors including medulloblastomas (15%), craniopharyngiomas (4%), and germ cell tumors (4%).

• Most brain tumors are supratentorial; notable exceptions include brainstem gliomas, cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas, medulloblastomas, and ependymomas that involve the posterior fossa.

• Glioblastoma (World Health Organization grade IV astrocytoma) and brainstem gliomas in children carry the poorest prognosis. Pilocytic astrocytomas carry the best prognosis.

• General signs and symptoms from mass effect, increased intracranial pressure, edema, or shift or destruction of surrounding brain tissue may include changes in personality and cognitive function, headaches, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and papilledema.

• Focal signs and symptoms may include focal seizures, visual changes, speech abnormalities, gait abnormalities, and cranial nerve deficits.

• Posterior fossa tumors often compress the fourth ventricle, causing hydrocephalus, and frequently manifest with ataxia and intractable nausea and vomiting.

• Brainstem gliomas often manifest with a combination of cranial nerve palsies and “long tract” signs such as hemianesthesia or hemiparesis coupled with ataxia in cases with cerebellar involvement.

• Pineal region tumors (germ cell tumors, pineocytomas, and pineoblastomas, as well as gliomas of this region) may compress the aqueduct of Sylvius, causing hydrocephalus. Compression of the pretectal area produces Parinaud syndrome, with paralysis of upgaze, ptosis, and loss of pupillary light reflexes, along with retraction-convergence nystagmus.

• Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium contrast is the most sensitive technique.

• Computed tomography scanning is good for visualizing intratumoral calcifications and bone erosion but poor at visualizing the posterior fossa.

• Positron emission tomography and advanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques may help discriminate between tumor recurrence and radiation necrosis or pseudoprogression.

• Magnetic resonance spectroscopy may help distinguish a high-grade tumor from a low-grade tumor or radiation necrosis.

• For most brain tumors, tissue diagnosis is required (an exception may be selected brainstem gliomas).

• Treatment for brain tumors is highly dependent on histologic type. For many tumors (e.g., gliomas, meningiomas, primitive neuroectodermal tumors [PNETs], and ependymomas), maximal surgical resection that is safely feasible is the primary treatment.

• For some tumors (e.g., glioblastomas, PNETs, and germ cell tumors), radiation therapy is an essential adjunct treatment after surgery.

• For some tumors (e.g., acoustic neuromas and glomus tumors), either irradiation or surgery can offer successful control; the decision between the two is based on assessment of adverse effects.

• Chemotherapy is assuming an increasingly important role in the management of many brain tumors (e.g., glioblastomas, germ cell tumors, anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, PNETs, and CNS lymphomas).

Introduction

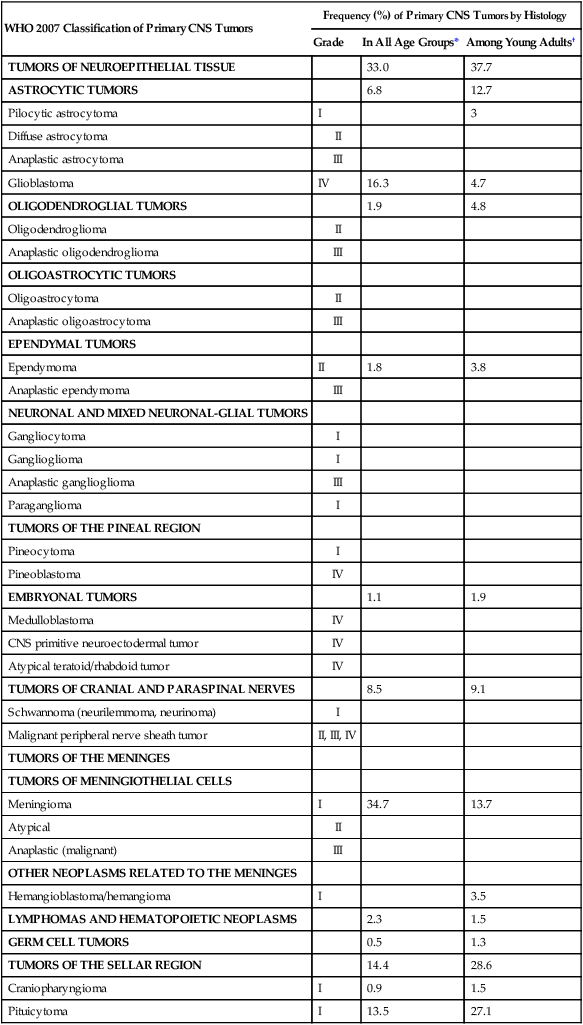

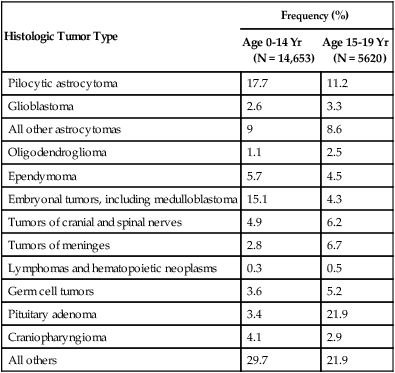

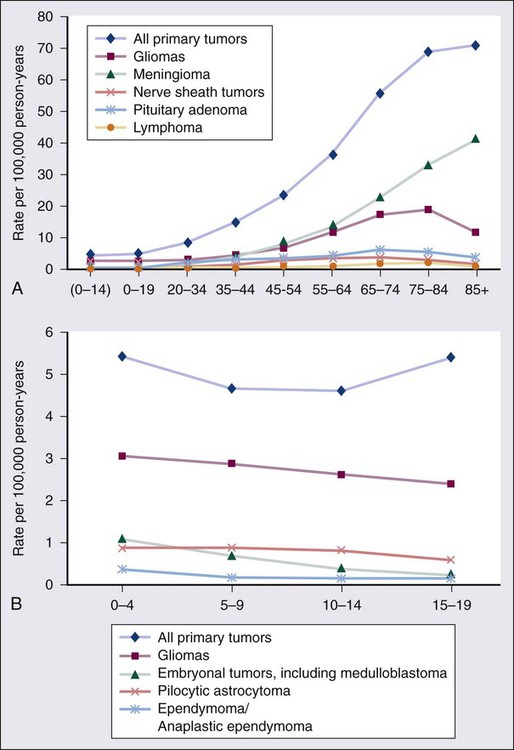

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of central nervous system (CNS) tumors is based on tumor histology and cellular origin and was established to provide a common classification and grading of human CNS tumors that is accepted and used worldwide. The WHO divides brain tumors into classes: neuroepithelial tumors, tumors of the cranial and paraspinal nerves, tumors of the meninges, lymphomas and hematopoietic neoplasms, and germ cell tumors and tumors of the sellar region.1 The different histologic types of CNS tumors are shown in Table 66-1. Meningiomas, glioblastomas, and astrocytomas constitute more than half of all CNS tumors. The frequency of different histologic tumor types varies with age, as shown in Figure 66-1. The incidence of all brain tumors is highest in the 75- to 84-year-old group. The incidence of meningiomas increases with increasing age, whereas for gliomas and pituitary adenomas, the incidence increases with age but then declines at the highest age category (see Fig. 66-1, A). Certain histologic types, such as germ cell tumors, medulloblastomas, and pilocytic astrocytomas, are far more common in children than in adults (Table 66-2; See Fig. 66-1, B).

Table 66-1

Primary Central Nervous System Tumors: Distribution by Histologic Type

| WHO 2007 Classification of Primary CNS Tumors | Frequency (%) of Primary CNS Tumors by Histology | ||

| Grade | In All Age Groups* | Among Young Adults† | |

| TUMORS OF NEUROEPITHELIAL TISSUE | 33.0 | 37.7 | |

| ASTROCYTIC TUMORS | 6.8 | 12.7 | |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | I | 3 | |

| Diffuse astrocytoma | II | ||

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | ||

| Glioblastoma | IV | 16.3 | 4.7 |

| OLIGODENDROGLIAL TUMORS | 1.9 | 4.8 | |

| Oligodendroglioma | II | ||

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | III | ||

| OLIGOASTROCYTIC TUMORS | |||

| Oligoastrocytoma | II | ||

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma | III | ||

| EPENDYMAL TUMORS | |||

| Ependymoma | II | 1.8 | 3.8 |

| Anaplastic ependymoma | III | ||

| NEURONAL AND MIXED NEURONAL-GLIAL TUMORS | |||

| Gangliocytoma | I | ||

| Ganglioglioma | I | ||

| Anaplastic ganglioglioma | III | ||

| Paraganglioma | I | ||

| TUMORS OF THE PINEAL REGION | |||

| Pineocytoma | I | ||

| Pineoblastoma | IV | ||

| EMBRYONAL TUMORS | 1.1 | 1.9 | |

| Medulloblastoma | IV | ||

| CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumor | IV | ||

| Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor | IV | ||

| TUMORS OF CRANIAL AND PARASPINAL NERVES | 8.5 | 9.1 | |

| Schwannoma (neurilemmoma, neurinoma) | I | ||

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | II, III, IV | ||

| TUMORS OF THE MENINGES | |||

| TUMORS OF MENINGIOTHELIAL CELLS | |||

| Meningioma | I | 34.7 | 13.7 |

| Atypical | II | ||

| Anaplastic (malignant) | III | ||

| OTHER NEOPLASMS RELATED TO THE MENINGES | |||

| Hemangioblastoma/hemangioma | I | 3.5 | |

| LYMPHOMAS AND HEMATOPOIETIC NEOPLASMS | 2.3 | 1.5 | |

| GERM CELL TUMORS | 0.5 | 1.3 | |

| TUMORS OF THE SELLAR REGION | 14.4 | 28.6 | |

| Craniopharyngioma | I | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| Pituicytoma | I | 13.5 | 27.1 |

CNS, Central nervous system; WHO, World Health Organization.

*Frequency among all patients with primary brain and CNS tumors (N = 295, 986). Other neoplasms without frequency listed together account for the remaining 6.7%.

†Frequency among young adults (20 to 34 years of age) with primary brain and CNS tumors (N = 25,250). Other neoplasms without frequency listed together account for the remaining 4.6%.

Data from WHO 2007 Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System and from Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), 2004-2008.

Table 66-2

Primary Central Nervous System Tumors of Childhood: Distribution by Histologic Type

| Histologic Tumor Type | Frequency (%) | |

| Age 0-14 Yr (N = 14,653) |

Age 15-19 Yr (N = 5620) |

|

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | 17.7 | 11.2 |

| Glioblastoma | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| All other astrocytomas | 9 | 8.6 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 1.1 | 2.5 |

| Ependymoma | 5.7 | 4.5 |

| Embryonal tumors, including medulloblastoma | 15.1 | 4.3 |

| Tumors of cranial and spinal nerves | 4.9 | 6.2 |

| Tumors of meninges | 2.8 | 6.7 |

| Lymphomas and hematopoietic neoplasms | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Germ cell tumors | 3.6 | 5.2 |

| Pituitary adenoma | 3.4 | 21.9 |

| Craniopharyngioma | 4.1 | 2.9 |

| All others | 29.7 | 21.9 |

Data from Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS 2012), 2004-2008.

Epidemiology

An estimated 66,290 new cases of primary CNS tumors were expected to be diagnosed in the United States in 2012.2 Approximately 22,910 of these tumors were expected to be malignant, representing 1.4% of all primary malignant cancers diagnosed in the United States.3 Malignant CNS tumors were expected to cause approximately 13,700 deaths in 2012.3

On the basis of data provided by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, Deorah and colleagues4 found that the incidence of brain cancer increased until 1987, when the annual percentage of change reversed direction. Elderly persons experienced an increase in brain cancer until 1985, but their rates were stable thereafter. Overall, however, the incidence of glioblastoma has been increasing, with survival only modestly improved during the past decade.5

Ionizing radiation is one of the few factors shown to have a strong association with the development of brain tumors. Exposure to ionizing radiation represents the most important exogenous risk factor for childhood brain tumors. Prenatal diagnostic x-ray exposure increases the risk of childhood brain tumors,6 and various reports describe the occurrence of gliomas, meningiomas, and other brain tumors in children who received radiation therapy to the head for tinea capitis and for prior malignancies.7–10 A dose of 1 to 2 Gy of radiation, which was used to treat tinea capitis in Israeli children, was associated with an increased risk of the development of brain tumors—specifically, meningiomas, gliomas, and nerve sheath tumors.11 A dose-response correlation in the induction of brain tumors was seen, with a relative risk of 3.0 at a dose of 1 Gy. Tumors developed at least 6 years after irradiation, with a mean interval greater than 15 years. Even lower doses of radiation delivered with radium-226 that were used to treat hemangiomas in Swedish infants (with a mean dose to the brain of 7 cGy) were found to be associated with an excess risk of intracranial tumors, including pituitary adenomas, gliomas, meningiomas, and nerve sheath tumors.12

A large amount of data has been accumulated on the incidence of brain tumors in patients who received cranial irradiation for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The estimated cumulative risk of secondary malignant brain tumors after childhood ALL therapy is 0.5% at 10 years after completion of therapy.13 In a study from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the actuarial 20-year probability of developing a brain tumor in these patients was 1.4%.14 The probability of developing a high-grade glioma was greater in children younger than 5 years of age at diagnosis than in those 6 years of age or older (1.08% vs. 0.45%; P = 0.045). An apparent dose-response correlation was observed: the 20-year risk of developing a brain tumor was 3.2% in patients who received greater than 30 Gy, versus 1.03% in patients who received 21 Gy or less (P = .015). No CNS malignancies were seen in patients who did not receive cranial irradiation. The latency between irradiation and the diagnosis of a brain tumor ranged from 5.9 to 29 years (median, 12.6) but was longer for meningiomas (median, 19 years) than for high-grade gliomas (median, 9.1 years). Very similar results regarding the frequency of brain tumors, latency, and dependence on prior cranial irradiation were seen in studies from the German Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster group15 and the Children’s Cancer Study Group.16 The types of brain tumors that have been reported in these series include gliomas, meningiomas, and medulloblastomas. Patients who received cranial irradiation for ALL also often received intrathecal chemotherapy. It has been suggested that cranial irradiation and intrathecal chemotherapy may work synergistically to increase the incidence of glial tumors.17,18

Viruses can induce brain tumors in animals in the experimental setting; however, no conclusive data point to viruses as a cause of brain tumors in humans (reviewed by Berleur and Cordier19). The relationship of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and gliomas remains controversial. The HCMV and gliomas symposium held in April 2011 resulted in consensus that sufficient evidence exists to conclude that HCMV viral gene expression exists in most, if not all, malignant gliomas and that HCMV could influence the phenotype of malignant gliomas by interacting with signaling pathways.20 Other authors who have used the Cytomegalovirus Seroprevalence in the United States data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1988-2004, have concluded that a possible CMV-glioblastoma association could not be corroborated with CMV seropositivity rates.21

Also lacking is conclusive evidence that occupational exposure to industrial chemicals leads to the development of brain tumors, although a number of studies have suggested such a link (reviewed by Wrensch and coworkers22). Some of the chemicals that can induce brain tumors in laboratory animals, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can do so only when administered by direct contact or transplacentally, but not by inhalation or dermal contact; the latter two modes of exposure are more relevant in the occupational setting. Specific chemicals that have been examined include cosmetics containing N-nitroso compounds, organic solvents, chemicals used in the manufacture of synthetic rubber, formaldehyde, phenols, polycyclic aromatic compounds, polyvinyl chloride, and pesticides. Although many chemicals can induce brain tumors in laboratory animals, no definitive associations have been found in humans. For example, N-nitroso compounds, which commonly are present in foods, are known to be neurocarcinogenic in animals. Oxidants in the environment can cause DNA damage, so it has been hypothesized that antioxidants, such as vitamin E, found in certain foods may protect against the development of cancers. Epidemiologic studies, however, have provided mixed support for the idea that the intake of N-nitroso compounds, antioxidants, or specific nutrients in foods can influence the risk of developing brain tumors.19

Vinyl chloride can induce brain tumors in rats; however, a recent review found that the association in humans is inconclusive.23

Recently a great deal of interest has emerged in a possible association between the use of cell phones and the risk of brain tumors. In a case-control study, Inskip and coworkers were unable to show a correlation between the duration of cell phone use and the development of gliomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.24 Other large case-control studies also have failed to find any association between cell phone use and the risk of developing brain tumors.27–27 A metaanalysis of 9 case-control studies revealed no increased risk in analog or digital cellular phone users.28 Nevertheless, some still claim that there is a link between cell phone use and brain tumors.29 Additionally, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a WHO agency, has classified radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.”30

Other factors that have been analyzed for their possible relationship to the development of brain tumors include a history of head trauma and injury, drugs and medications, allergies, seizures, smoking and alcohol consumption, and exposure to power-frequency electromagnetic fields. None of these factors, however, has been conclusively shown to be important (reviewed by Wrensch and associates22).

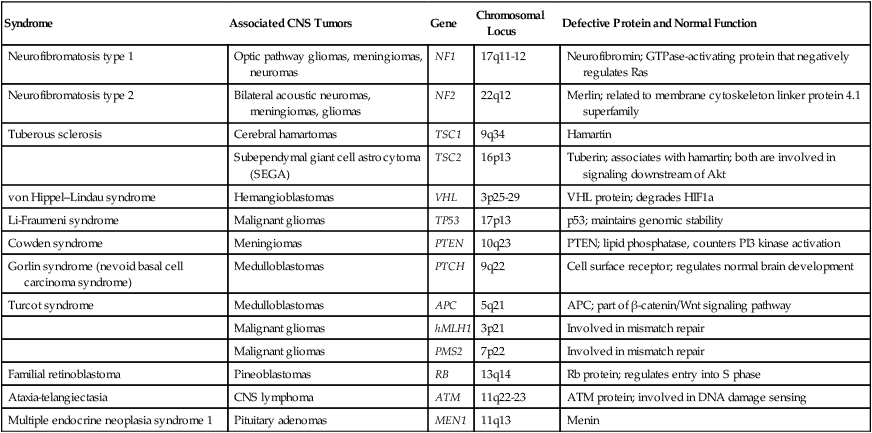

Most brain tumors represent sporadic cases; however, familial clustering has been noted. It is estimated that hereditary syndromes account for 2% of childhood brain tumors, although this may be an underestimate because hereditary syndromes may be undiagnosed in a number of cases.31 Some hereditary syndromes known to be associated with brain tumors are listed in Table 66-3 (reviewed by Kimmelman and Liang32). Some of the associations are extremely strong. Nearly 70% of all optic pathway gliomas occur in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and acoustic neuromas commonly occur in patients with NF2. In addition, hereditary immunosuppression disorders such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, as well as treatment-associated immunosuppression as in organ-transplant recipients, or exogenous immunosuppression as in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, are known to be associated with an increased risk of primary CNS lymphoma.

Table 66-3

Hereditary Syndromes Associated with Brain Tumors

| Syndrome | Associated CNS Tumors | Gene | Chromosomal Locus | Defective Protein and Normal Function |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | Optic pathway gliomas, meningiomas, neuromas | NF1 | 17q11-12 | Neurofibromin; GTPase-activating protein that negatively regulates Ras |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | Bilateral acoustic neuromas, meningiomas, gliomas | NF2 | 22q12 | Merlin; related to membrane cytoskeleton linker protein 4.1 superfamily |

| Tuberous sclerosis | Cerebral hamartomas | TSC1 | 9q34 | Hamartin |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) | TSC2 | 16p13 | Tuberin; associates with hamartin; both are involved in signaling downstream of Akt | |

| von Hippel–Lindau syndrome | Hemangioblastomas | VHL | 3p25-29 | VHL protein; degrades HIF1a |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | Malignant gliomas | TP53 | 17p13 | p53; maintains genomic stability |

| Cowden syndrome | Meningiomas | PTEN | 10q23 | PTEN; lipid phosphatase, counters PI3 kinase activation |

| Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome) | Medulloblastomas | PTCH | 9q22 | Cell surface receptor; regulates normal brain development |

| Turcot syndrome | Medulloblastomas | APC | 5q21 | APC; part of β-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway |

| Malignant gliomas | hMLH1 | 3p21 | Involved in mismatch repair | |

| Malignant gliomas | PMS2 | 7p22 | Involved in mismatch repair | |

| Familial retinoblastoma | Pineoblastomas | RB | 13q14 | Rb protein; regulates entry into S phase |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia | CNS lymphoma | ATM | 11q22-23 | ATM protein; involved in DNA damage sensing |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome 1 | Pituitary adenomas | MEN1 | 11q13 | Menin |

Tumor Biology

Cell Proliferation

Normal cells rely on growth factors secreted in their local environment to stimulate their growth. However, many CNS tumors have developed the ability to express their own growth factors along with the respective receptors, resulting in an autocrine loop that allows for self-stimulation.33 Platelet-derived growth factor receptor–α (PDGFR-α), for example, is overexpressed in all grades of astrocytomas, but only higher-grade tumors overexpress the ligands PDGFA and PDGFB.34 Insulin-like growth factors and their receptors both are expressed in brain tumors, including gliomas and meningiomas.35 The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is amplified or overexpressed in 50% of glioblastomas,33 and expression of transforming growth factor–α (TGF-α), a ligand that binds to this receptor, is increased in many gliomas.36,37 Both scatter factor (also known as hepatocyte growth factor) and its receptor c-Met are expressed in gliomas, with the highest level of expression seen in the most malignant tumors.38

As a result of increasing expression of receptors and ligands, increased signaling occurs in many brain tumors, resulting in activation of many different pathways that are important in proliferation (reviewed by Rao and James36). The best studied of these pathways is the microtubule-associated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which involves Ras and Raf. Another pathway that has attracted much attention recently is the phosphoinositide-3 (PI3) kinase pathway, which leads to activation of Akt. Mutation of PTEN, which occurs in 30% to 40% of glioblastomas, also can lead to increased Akt activation.39

Ras activation commonly is seen in human astrocytomas and neurofibromas despite the fact that these tumors rarely contain Ras mutations. In astrocytomas, Ras activation probably occurs through activation of growth factor receptors such as EGFR and PDGFR.40 Other mechanisms of activation of aberrant G proteins have been identified in other CNS tumors (reviewed by Woods and co-workers41). In NF1, loss of expression of neurofibromin, an inactivator of Ras, is seen (see Table 66-3). This loss of neurofibromin leads to the increased Ras activation seen in NF1-associated astrocytomas. Pituitary adenomas often show activation of the α subunit of the large heterotrimeric Gs protein, resulting in mitogenic signaling.

The Wnt pathway has been shown to play a role in glioma tumorigenesis. Investigators have shown that the Wnt-specific secretory protein Evi is overexpressed in astrocytomas.42 Furthermore, the same researchers showed that the depletion of this protein in glioma cells leads to decreased cell proliferation and apoptosis. Additionally, silencing of Evi in glioma cells leads to reduced cell migration and the ability to form tumors in vivo.42 Involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in gliomas has been reviewed by Zhang et al.43

Invasion

Many brain tumors, particularly gliomas, display an invasive phenotype with infiltration of tumor cells into surrounding tissues, making a cure very difficult to achieve. In fact, tumor recurrence was reported in one case even after the drastic measure of taking out the entire hemisphere in which a glioma was located.44 The process of invasion involves several steps: detachment of the invading cell from the primary tumor mass, adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM), degradation of ECM, and cell motility and contractility.45 The details of the mechanisms of glioma invasion are only beginning to be understood. Numerous molecules associated with invasion have been found to be upregulated in gliomas, including tenascin-C, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), various integrins, and matrix metalloproteinases (reviewed by Demuth and Berens46).

Some controversy exists regarding deregulated Rho guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) signaling in brain tumors. For example, although RhoA and RhoB are reduced in some astrocytic tumors, some studies report Rho-dependent lysophosphatidic acid–induced migration in glioma cells. Expression of another member of the Rho subfamily, Rac1, has been found to be reduced in astrocytic tumors; additionally, this protein has been shown to be overexpressed and to have induced invasion in medulloblastoma tumors. The role of Rho GTPases has been reviewed by Khalil and El-Sibai.47

Angiogenesis and Hypoxia

For a tumor to grow beyond a certain size, it must develop a blood supply. The process of angiogenesis is described in detail in Chapter 8. The vasculature of normal brain, which is composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes, is highly specialized. Together these cells form the blood-brain barrier, which selectively restricts exchange of molecules between the intra- and extracerebral circulatory systems. As primary brain tumors or brain metastases grow, the integrity of the blood-brain barrier is compromised.48–51

A number of growth factors are known to be important in angiogenesis. The most prominent of these is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is overexpressed in many brain tumors. In one study, increasing VEGF expression correlated with increasing malignant grade in astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymomas.52 In this study it also was found that increased expression of the VEGF receptors Flt-1 and KDR in tumor vasculature correlated with increasing VEGF expression and malignant grade. Hypoxia and acidosis have been shown to independently regulate VEGF transcription in brain tumors in vitro and in vivo.53 Additionally, both tumor suppressors and oncogenes, as well as hormones, cytokines, and other signaling molecules, have been shown to regulate VEGF expression.51,54–57 Growth factors other than VEGF that may play a role in angiogenesis in gliomas include members of the TGF-β family, PDGF, placenta growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and scatter factor/hepatocyte scatter factor.58 Angiogenesis can also be negatively regulated by factors such as thrombospondins 1 and 2 (TSP1 and TSP2). TSP1 is positively regulated by p53, and thus loss of p53, which commonly occurs in gliomas, can lead to decreased TSP1 expression and increased angiogenesis.58 Angiogenesis in brain tumors has been reviewed by Jain et al.51

Angiogenesis is particularly prominent within glioblastomas. One of the characteristic features of these tumors is endothelial proliferation and neovascularization. A variety of growth factors that can increase angiogenesis are expressed by glioblastomas, with the foremost being VEGF. VEGF, also known as vascular permeability factor, is a potent inducer of capillary permeability. The high levels of VEGF expression in glioblastomas may be responsible for the edema associated with these tumors. Some evidence indicates that genetic changes common to glioblastomas, such as EGFR activation and PTEN mutation, may contribute to high levels of VEGF expression, perhaps through activation of the PI3 kinase pathway.61–61

Despite expressing high levels of VEGF, glioblastomas contain significant regions of hypoxia, which may be a cause of treatment resistance. Hypoxia has been shown to be present in malignant gliomas by both polarographic needle electrode measurement62,63 and binding of the 2-nitroimidazole EF5.64 Hypoxia, as measured by binding of EF5, has been shown to correlate with more rapid tumor recurrence.64 Evidence indicates that hypoxia is involved in many aspects of tumor growth, including induction of angiogenesis, increased invasion and metastases, resistance to chemotherapy, resistance to radiotherapy, increased brain tumor stem cell population, and stem cell genetic instability.65

The presence of hypoxia in glioblastomas is consistent with the histologic features commonly seen in these tumors, including the presence of pseudopalisading necrosis and proliferative blood vessels. It has been proposed that pseudopalisades seen within glioblastomas represent a wave of tumor cells actively migrating away from central hypoxia that arises as a result of vasoocclusion and intravascular thrombosis.66 It may seem counterintuitive that hypoxia can persist in the presence of high VEGF levels and robust neovascularization; however, the explanation may be that although hypoxia may stimulate VEGF and the formation of new vessels, many of these vessels are nonfunctional and do not transport oxygen well.

Stem Cells

Identification of glioblastoma stemlike cells has proved to be challenging. Early studies showed differences between CD133+ and CD133− glioma cells, including differences in tumor-forming capacity in xenografts.67 However, other studies have shown that CD133− stemlike cells may also be capable of forming tumors, although these two cell populations exhibit distinct molecular profiles and growth characteristics.68

Efforts are being made to elucidate transduction pathways that influence tumorigenicity and are unique to glioma stemlike cells to allow treatments to target these pathways. It has been demonstrated that glioma stemlike cells may be relatively radioresistant as a result of overexpression of DNA damage repair proteins, including the checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2.69 The cells may be made more radiosensitive by using specific inhibitors of Chk1/Chk2. Piccirillo and colleagues70 showed that CD133+ glioblastoma stem cells have a functional bone morphogenic protein receptor pathway. By exposing mice implanted with orthotopic glioblastomas to bone morphogenic protein 4, they were able to cause the CD133+ cells to differentiate toward glial cells and reduce tumor growth. These two strategies have the potential to be used to target stem cells in glioblastomas. Another potential strategy is to target the tumor stroma, which provides a specialized niche for tumor cells. Calabrese and associates71 showed recently that stem cells in brain tumors occupied a perivascular niche and can be targeted by using antiangiogenic therapy.

Other potential targets include signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a transcription factor activated by interleukin (IL)-6, a molecule that is overexpressed in glioblastoma. STAT3 is constitutively active in numerous cancers, including glioblastoma. Expression of a dominant negative mutant STAT3 or silencing STAT3 with a lentivirus have been shown to reduce proliferation of a glioblastoma cell line.72 Other groups are investigating nanotechnology to target glioma stemlike cells. Some investigators have used iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated to a glioblastoma-specific target of EGFRvIII in an animal model,73 whereas others have used curcumin nanoparticles to inhibit glioblastoma and medulloblastoma cell proliferation in culture.74 Glioblastoma stemlike cells have been reviewed in detail by Nduom et al.75 and by Tabatabai and Weller.76 The stemlike cell hypothesis applies to other brain tumor histologies as well. The role of medulloblastoma and ependymoma tumor-initiating cells have been reviewed by Manoranjan et al.77 and Poppleton and Gilbertson,78 respectively.

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology of Signs and Symptoms

Parenchymal brain tumors produce clinical signs and symptoms by three main mechanisms, each of which has important implications for therapy. First, infiltration along nerve fiber tracts is typical of primary brain tumors such as low-grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. The first clinical manifestation may be seizures. Normal brain tissue may be present within areas appearing abnormal on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and functional mapping may be necessary for safe resection of these slowly growing tumors.79–82 Second, displacement of brain tissue with production of vasogenic edema is typical of cerebral metastases. Such tumors sometimes can be resected or irradiated focally with less risk to adjacent normal brain tissue than is the case with infiltrating tumors. Third, rapidly growing aggressive tumors such as high-grade astrocytomas may enlarge as a mass and also destroy surrounding neuropil to such an extent that surgical resection, although helpful for the reduction of mass effect and intracranial pressure (ICP), may not alleviate local symptoms and signs.

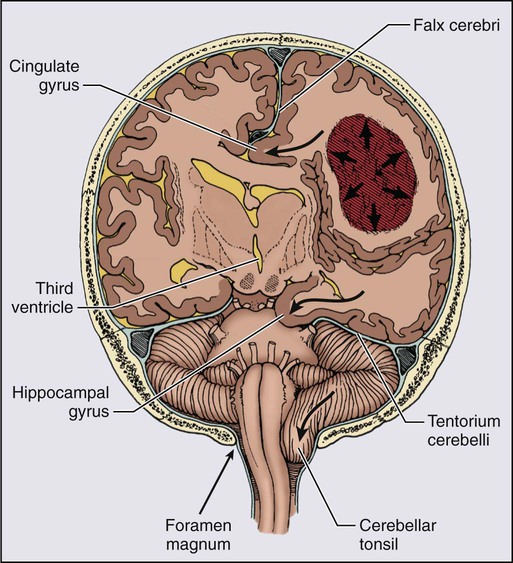

Sustained ICP in excess of 200 mm H2O causes brain shifts that can displace brain tissue through fixed intracranial openings, producing life-threatening herniation syndromes83 (Fig. 66-2). The uncal herniation syndrome is caused by tumors arising in the lateral aspect of the brain, most commonly the temporal lobe. The earliest, most consistent sign of uncal herniation is a unilaterally dilated pupil due to compression of the ipsilateral third cranial nerve, which is followed by extraocular movement abnormalities consistent with an oculomotor palsy. The posterior cerebral artery may be compressed against the tentorium, leading to homonymous hemianopia. Brainstem compression can cause compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle against the edge of the tentorium, causing what is known as the Kernohan notch phenomenon.84 Patients with uncal herniation initially may be awake, but progression to obtundation, coma, and death may occur rapidly.

The central herniation syndrome results from tumors that arise along the midline axis of the brain, especially those deep in the basal ganglia and thalamus regions. The initial signs and symptoms are due to diencephalic compression. The first evidence for this syndrome often is an alteration in the level of alertness and behavior. Some patients become agitated, whereas others become very drowsy. Hemisensory or hemiparetic deficits and periodic Cheyne-Stokes respirations may develop in these patients. Initially with diencephalic compression, pupils are small (1 to 3 mm), but as the syndrome progresses and the midbrain and upper pons are compressed, the pupils dilate moderately and fix at midposition (3 to 5 mm). As the syndrome progresses, patients become progressively lethargic and apathetic and Cushing’s signs of hypertension and bradycardia may develop as a result of direct compression of the hemodynamic control nuclei within the brainstem.85,86

General Signs and Symptoms

Seizures occurring for the first time in adults are more likely to be due to focal brain pathology, particularly neoplasms, than are seizures occurring in childhood. Intracranial tumors produce generalized tonic-clonic seizures, secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and partial, localization-related seizures. Seizures are more common in persons with cortical tumors than in persons with infratentorial or deep thalamic lesions, and they occur more often in low-grade astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, or oligoastrocytomas (60% to 80%) than in high-grade gliomas (20% to 40%) or cerebral metastases (15% to 20%).87,88 Seizures occur at some time in 25% to 50% of patients with brain tumors. Seizure frequency may increase during radiation treatment and continue at an increased frequency for several months thereafter because of localized swelling.

Papilledema, that is, swelling of the optic nerve head with engorgement of retinal veins, usually indicates raised ICP. Currently, papilledema is seen in fewer than 20% of patients at presentation, down from 59% in the 1971 report by Huber.89 The development of papilledema is dependent on the location of the tumor and the rate of growth.

Treatment of Brain Tumor Symptoms

Acute Raised ICP

Chronically Increased ICP

Dexamethasone in doses of 8 to 40 mg per day upregulates angiopoietin 1 to stabilize the blood-brain barrier and downregulates VEGF.92–92 Controlling the edema helps to control headache, nausea, and seizures as well. Because chronically raised ICP can cause visual loss, careful ophthalmologic follow-up evaluation with visual field assessment is essential. Acetazolamide therapy for symptomatic plateau waves has been useful for some patients with raised ICP from intracerebral or leptomeningeal tumor.93

In the doses required to treat cerebral edema, corticosteroids produce many adverse effects that range from the easily managed gastritis symptoms and glucose intolerance to insomnia, steroid psychosis, intractable hiccoughs, and disabling myopathy. The psychosis may readily respond to reduction of the steroid dose and the addition of neuroleptic agents. Treatment of the steroid myopathy, however, will require weeks of physical therapy with attempts at steroid reduction. Anecdotal reports suggest that substitution of a nonfluorinated steroid such as methylprednisolone for fluorinated steroids such as dexamethasone may help minimize the weakness.94

Many patients with brain tumors are treated with corticosteroids for prolonged periods and are thus susceptible to infection, particularly with Pneumocystis jiroveci, which carries a 50% mortality rate. Among solid tumors, primary and metastatic brain tumors have the highest rate of Pneumocystis infection, which occurs in 2% of patients and proves fatal to 40% of these patients.95 The mean duration of steroid therapy before infection was 7 months, with a mean dexamethasone equivalent dose of 1 to 2 mg per day.96 In view of these statistics, prophylaxis with one double-strength tablet of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole three times a week should be provided for patients with brain tumors during steroid administration and for 1 month afterward. Alternatives for patients allergic to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are aerosolized pentamidine, dapsone, or atovaquone. Withdrawal of corticosteroids after use for more than 2 weeks may result in an adrenal insufficiency state with symptoms of lethargy, hypotension, electrolyte imbalance, arthralgias, and diffuse weakness that may be difficult to distinguish from those of the tumor. Intercurrent systemic stressors such as surgery or systemic infection may lead to serious hypotension. Chronic glucocorticoid supplementation with hydrocortisone, 10 to 20 mg per day, is essential for these patients.97,98

In view of the multiple complications of corticosteroids, the urgent need for alternative drugs to control cerebral edema is evident. The advent of VEGF inhibitors offers the possibility of controlling peritumoral edema with such agents as bevacizumab or cediranib.99

Seizures

A rash develops in approximately 20% of patients with gliomas who are treated with phenytoin or carbamazepine and cranial irradiation; the most serious and sometimes life-threatening reaction, the Stevens-Johnson syndrome, occurs in a few patients. This reaction is seen in the setting of hypersensitivity to AEDs that is unmasked during tapering of high-dose corticosteroids. The mechanism may be depletion of suppressor T cells by radiation, allowing emergence of the hypersensitivity syndrome, sometimes also called DRESS (drug rash, eosinophilia, and systemic symptoms).100,101 Treatment is controversial, but often the corticosteroid dose is doubled as AEDs are withdrawn abruptly.

In view of all of the potential hazards of AEDs, it is worthwhile to consider whether their prophylactic use is justified in the brain tumor population. A controlled prospective study of patients with brain tumors addressing the question of prophylaxis for epilepsy showed an overall incidence of 26% with no difference in the seizure rate between patients taking AEDS and patients not receiving prophylaxis.102 A second study involving 100 patients with brain tumors confirmed the lack of efficacy of AEDs in preventing seizures or altering survival outcome in this clinical setting.103 These findings are consistent with those of Foy and colleagues,104 who conducted a prospective trial in 276 patients who had undergone craniotomy (not all of whom had tumors) who were randomized postoperatively to receive phenytoin, carbamazepine, or no treatment. No difference in the incidence of seizures (37%) or postoperative complications was found among the groups.104 For all of these reasons, a practice parameter published by the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology concluded that no benefit could be established for routine prophylactic use of AEDs in patients with brain tumors.105 However, the advent of AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes has recently caused some neurologists to reconsider prophylactic use of seizure medicines in high-risk patients, particularly those with hemorrhagic metastases, such as patients with melanoma.

Of the newer agents, levetiracetam is emerging as an excellent choice in patients with a brain tumor because its level is not affected by chemotherapy drugs and it does not alter the metabolism of any chemotherapeutic agents. The clinician must be familiar with some adverse effects specific to these drugs (summarized in Table 66-4) to be able to diagnose symptoms accurately, eliminate the offending drug, and avoid unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Table 66-4

Adverse Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs: Special Issues in Patients with Brain Tumors

| Drug | Potential Adverse Effect(s) |

| Oxcarbazepine | Hyponatremia (confusion, seizures) |

| Gabapentin | Sedation, ataxia, weight gain |

| Depakote | Weight gain, platelet dysfunction |

| Topiramate | Memory/word-finding problems, weight loss |

| Zonisamide | Sedation |

| Levetiracetam | Psychosis, irritability, lethargy |

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis is extremely common in patients with brain tumors, with a reported incidence of 28% to 45%.106,107 High-grade tumors express elevated levels of tissue factor, which plays an important role in initiation of the coagulation cascade.108 Patients with gliomas and meningiomas are at the highest risk for thromboembolism, which is a common cause of fever of unknown origin in this population. Alterations in fibrinolysis, immobility, paresis, tumor necrosis factor, steroids, and neurosurgical procedures all combine to make patients with brain tumors a high-risk group. The risk is greatest in the postoperative period and in patients with hemiplegia. Antiangiogenic agents are associated with a small increased risk of thrombosis and bleeding.109 Patients receiving thalidomide or derivatives have a high risk of thromboembolism, and chronic prophylaxis is recommended.110 It appears that patients taking bevacizumab may safely undergo anticoagulation.111

Many patients with brain tumors receive vena cava filters because of the perceived risk of hemorrhage into their intracranial tumors. However, retrospective studies have suggested a very low risk of hemorrhage and also have demonstrated an incidence of complications of vena cava filters of greater than 60% in this patient group. Complications included pulmonary embolism, filter thrombosis, and postphlebitic syndrome.112 Low-molecular-weight heparin drugs have a good safety profile in the neurosurgical population.113 Prophylaxis with enoxaparin, 40 mg, administered subcutaneously daily, plus use of external compression stockings has been found to be superior to the use of compression stockings alone for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after neurosurgery.114,115 Although no absolute guidelines are available, most neurosurgeons would be reluctant to institute full anticoagulation in these patients within 3 weeks of surgery. Because most primary and secondary brain tumors pose a continuing risk of thromboembolism, life-long anticoagulation is recommended. Patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia must not receive heparin products. No clear-cut guidelines exist for the use of direct thrombin inhibitors in patients with brain tumors. Current FDA-approved low-molecular-weight heparinoids include dalteparin, enoxaparin, tinzaparin, and nadroparin. A subset of patients with late white matter changes due to radiation therapy, like patients with extensive ischemic leukoaraiosis, may be at special risk for brain hemorrhage while taking heparin.

Diagnostic Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Multiple sequences may be obtained from the MRI scans, highlighting different properties of both brain and tumor. Of particular interest are the T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. These sequences highlight tumor-related vasogenic edema and nonenhancing portions of the tumor, which appear as areas of increased T2 signal compared with normal brain. Evaluating this signal pattern is very important in assessing the degree of mass effect, because the increased signal may represent the true limits of a glial tumor, as tumor cells are invariably present in the nonenhancing tissue surrounding the enhancing component.116 This phenomenon provides the rationale for extending the irradiated zone in standard external beam radiation therapy to include the edematous volume of brain plus a margin. The presence of an edema pattern extending into the corpus callosum implies direct tumor invasion into the corpus callosum. The extremely compact fiber tracts passing through the corpus callosum impede passage of edematous fluid, and thus any increased T2 signal that is present is likely created by tumor infiltration. This point is very important to keep in mind in assessing the extent of tumor.

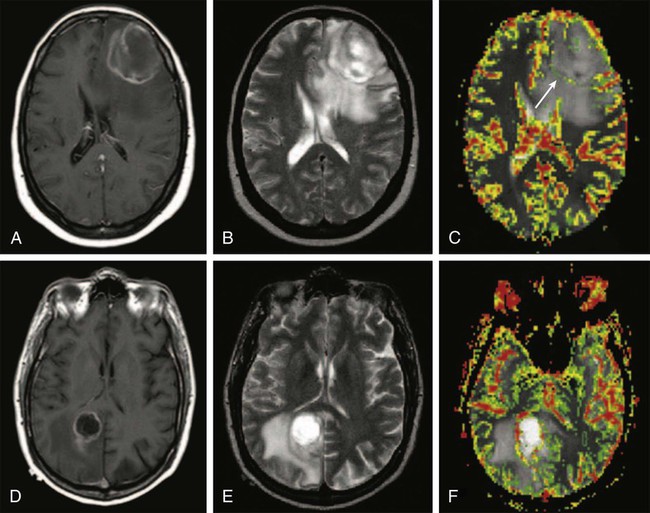

Endothelial proliferation with neovascularity is a hallmark of malignancy in brain neoplasms. Both MRI and CT perfusion imaging can be performed in combination with conventional MRI examinations to determine the extent of neovascularity.117 The correlation between relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and grade of malignant glioma appears to be very good.118 Perfusion imaging with dynamic susceptibility contrast–enhanced MRI is especially helpful in distinguishing grade III from grade IV malignant gliomas, but it can also be used to distinguish gliomas from other neoplasms such as intracranial metastases (Fig. 66-3).119,120 It has been shown that anaplastic astrocytomas that enhance have a higher vascularity index than do nonenhancing anaplastic astrocytomas. Perfusion imaging may enable monitoring of the antiangiogenic effects of treatment in brain tumors. Furthermore, perfusion imaging is also useful in determining vascularity in benign tumors such as meningiomas, a phenomena that may be associated with disease progression.121

Functional MRI techniques have been used to identify areas of brain activity in real time, which is quite useful when identifying regions of eloquent brain adjacent to tumors.122,123 By identifying language and motor areas adjacent to tumors, one can determine the extent of surgical resection that can be carried out while attempting to preserve functional activity.124 It is now possible to import functional MRI images into frameless stereotaxy units that are used for intraoperative surgical planning.125 By using discrete motor, sensory, language, or visual paradigms, the functional activity of relevant cortical brain can be imaged. One limitation to functional MRI scanning is its inability to identify subcortical white matter tracts adjacent to the gray matter activated by the investigated activity. For this reason, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is increasingly being used to map subcortical white matter tracts. It has been shown that combining DTI with conventional anatomic images of the lesion of interest facilitates extended resection of tumor while preserving function.126

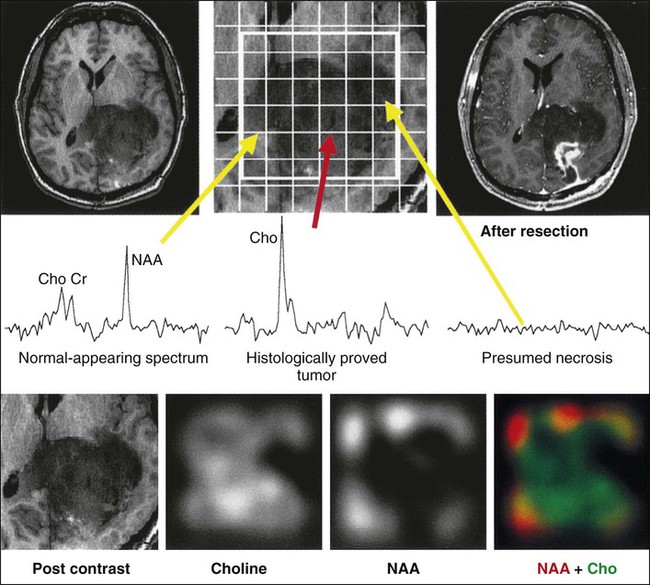

A great deal of interest has centered on the capability of clinical MRI scanners to perform magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to evaluate molecular components of a defined voxel within the brain tissue. Today’s smaller voxel sizes allow a much greater degree of selectivity in evaluating components of a tumor. MRS of malignant gliomas has been evaluated extensively, and the presence or absence of five metabolites provides the most useful information. N-acetylaspartate (NAA) is a marker of healthy neurons, whereas increases in choline are associated with high cellular turnover. Creatine serves an internal marker and is related to the energy state of the tumor. A lipid peak indicates the presence of necrosis and suggests higher grade malignancy, whereas lactate indicates the presence of hypoxia.127,128 Malignant gliomas exhibit a higher choline peak relative to creatine and a lower NAA peak relative to choline, with increasing grade of malignancy (Fig. 66-4). Lipid and lactate peaks, which also constitute markers of malignancy, can be seen both in primary gliomas and metastatic tumors. MRS can help determine whether an enhancing region in a previously treated tumor bed represents active tumor or radiation necrosis. MRS is also used to monitor treatment effects over an extended period. The development of the multivoxel technique, in which small individual voxels within large areas of the brain can be evaluated, allowing one to determine small areas of active tumor within a large region of brain, has been quite useful.

Computed Tomography

A CT scan usually is the first study obtained when a patient presents with a neurologic complaint. In part because of its extensive availability and rapid acquisition times, CT provides a robust screening tool. Hemorrhagic lesions can be seen as a result of the increased density of extravasated blood products in comparison with surrounding tissues. Infarcts manifest acutely as edematous hypodense tissue and can be confused with tumors, especially low-grade gliomas, which may not enhance with contrast agents. However, cytotoxic edema associated with infarcts often involves both gray and white matter, whereas vasogenic edema as a result of the presence of tumor predominately involves the white matter. Iodinated contrast agents may be useful to differentiate tumor from the surrounding edematous brain tissue because disruption of the blood-brain barrier permits leakage of the contrast agent into the interstitial space. The pattern of ring enhancement of tumors may be difficult to distinguish from the ring enhancement of a cerebral abscess, although brain tumors are far more common than brain abscesses in the United States. Infarcted brain tissue may also enhance after administration of contrast material. This finding is most common 2 to 3 weeks after a stroke, and thus clinical history should complement image interpretation.129

Positron Emission Tomography

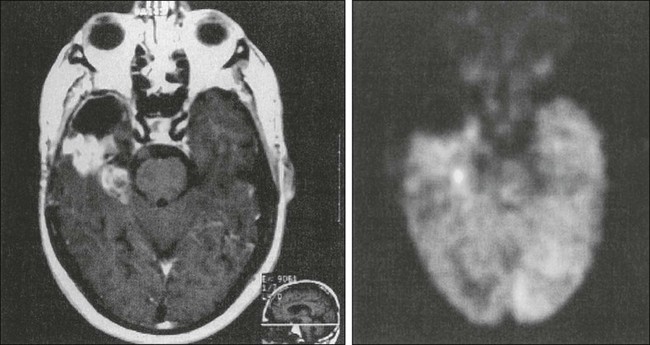

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging uses a radioactive isotope analogue of glucose, fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), to image glucose metabolism. Because glucose is the sole fuel for brain tissue, this metabolic imaging allows visualization of brain physiology. Because glioblastomas, untreated primary CNS lymphoma, oligodendrogliomas, and malignant meningiomas have increased glucose metabolism compared with normal brain tissue, these tumors have greater FDG avidity and will be “PET positive.”130 Anaplastic astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, meningiomas, and metastatic tumors show variable FDG uptake (Fig. 66-5), whereas low-grade gliomas and radiation necrosis show little to no FDG uptake. PET imaging using targeted tracers, such as the somatostatin-receptor ligand gallium-68 DOTATOC in meningiomas, might be more useful for tumors where FDG is too variable for accurate delineation.131

Surgery: General Considerations

Establishing a tissue diagnosis is extremely important for therapeutic and prognostic considerations. Frequently, the histologic diagnosis may be straightforward; however, a category of tumors exist that manifest as mixed gliomas, in which tissue sampling can induce errors in diagnosis.132 A limited biopsy specimen may show a solitary cell type, but examination of a more extensive specimen may reveal the presence of other components. Accurate diagnosis is particularly important when the other components identified may change the histopathological interpretation from a grade II glioma to an anaplastic grade III glioma. Noninvasive means of establishing tissue diagnosis have been pursued, primarily through the use of MRS.133,134 Significant progress has been made to determine the histologic diagnosis of tumors with MRS; however, MRS is still not specific enough to form the basis for major therapeutic decisions. Histopathological determination remains the gold standard.

The most common presenting manifestations in patients with glioma are headache and seizures.135 Debulking large tumors will reduce dural stretch, thus decreasing headaches. The incidence of seizures in patients with malignant gliomas can be decreased by at least 75% with attempts at gross total resection.136 Recovery from other neurologic deficits such as hemiparesis, visual field loss, or aphasia will depend on whether the impaired brain tissue is merely compressed by the tumor mass or whether the tumor has infiltrated and damaged these neural tracts. In the former case, but not the latter, debulking the tumor will help relieve the patient’s symptoms.

Radiation Therapy: General Considerations

Radiation Therapy: Technical Details

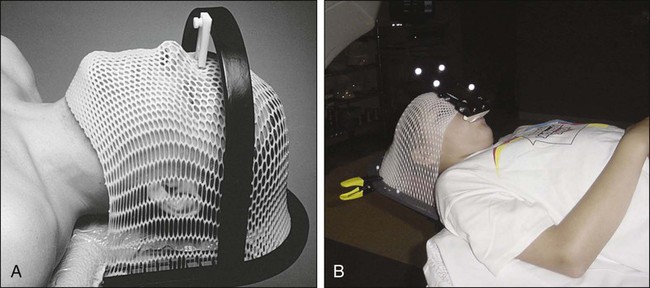

Treatment planning begins with CT simulation of the patient with appropriate immobilization devices. Figure 66-6 shows thermoplastic mask and bite-block immobilization devices. A previously obtained MRI image or an MRI image obtained at the time of simulation may be fused with the CT images in the treatment planning system to facilitate better target volume delineation. Computerized treatment planning is then used to generate radiation beam angles, blocks, and dose distributions.

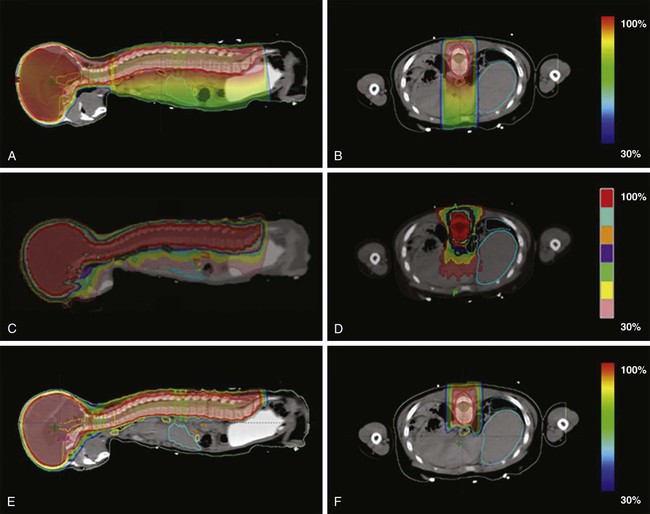

Most brain tumors are treated with focal radiation therapy, and often brain metastases and some leukemias and lymphomas require whole-brain radiotherapy; however, for some tumors, such as primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) and metastatic germ cell tumors of the CNS, it may be necessary to include the entire craniospinal axis in the irradiated zone. Proton therapy for craniospinal irradiation has the advantage of reducing dose to the vertebral bodies and essentially eliminating exit dose through the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis.137 E-Figure 66-1 shows sample treatment plans for craniospinal irradiation using three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, tomotherapy, and proton beam techniques.138

Adverse Effects after Irradiation of the Brain or Spine

Acute and Early Delayed Effects after Cranial Irradiation

A variety of adverse effects may occur after irradiation of the CNS (reviewed by Schultheiss and associates139). These effects can be divided into acute, which occur during the treatment; delayed early, which occur within a few months of radiation; and late, which occur months to years later.

The most common delayed early effect from radiation is the somnolence syndrome, which is characterized by excessive drowsiness, nausea, and irritability.140 If this syndrome occurs, it generally does so 1 to 3 months after radiation has been completed. This syndrome is thought to be due to transient, diffuse demyelination. It usually is seen after whole-brain irradiation but also can develop after limited-field irradiation. The syndrome resolves spontaneously, but steroids can shorten its duration. Delayed early effects occurring after cranial irradiation can also take the form of focal neurologic signs due to intralesional reactions related to tumor response or perilesional reactions related to edema or demyelination.

Radiation Necrosis of the Brain

One of the most serious late effects of cranial irradiation is brain necrosis, which may cause significant and persistent neurologic injury.141,142 Histopathological changes seen in radiation necrosis include coagulative and liquefactive necrosis, mostly in white matter, and associated endothelial thickening, vascular hyalinization, fibrinoid deposition, and calcification.143 It may produce progressive cerebral edema and mass effect requiring prolonged corticosteroid use or surgery. Radiation necrosis may be confused with tumor growth, resulting in the inappropriate use of antitumor therapies. The onset of radiation necrosis includes behavioral changes, such as lethargy and dementia, headache and papilledema, and seizure. Clinical signs and symptoms are usually identified from 2 to 3 years after irradiation, although confirmed cases have been detected as early as 9 months and as late as 16 years after completion of radiation therapy. The signs and symptoms are strongly related to the site of radiation necrosis; however, the most common clinical signs are focal motor deficits.

Accurate data regarding the incidence of brain necrosis based on CT and MRI findings come from a randomized trial of irradiation for low-grade gliomas.144 In this study, the 2-year actuarial incidence of brain necrosis was 2.5% for patients receiving 50.4 Gy and 5% for those receiving 64.8 Gy. A retrospective review of 426 patients treated for glioma with radiation found that radionecrosis developed in 4.9% of patients.145 The risk of necrosis increased with longer survival and with increasing dose of radiation. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with increased risk of radiation necrosis.145

Often radiation necrosis is difficult to distinguish from recurrent tumor by CT or MRI, which may show increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images and contrast enhancement on T1-weighted images.146 As discussed earlier in the Diagnostic Imaging section, PET scanning with FDG may help distinguish viable tumor from necrotic tissue.149–149 Advanced MRI techniques may also help differentiate tumor from necrosis. On MRS, NAA is significantly reduced in patients with radiation necrosis, whereas changes in choline and creatine are more variable. A high choline level is more consistent with disease progression, whereas a decreased creatine level is generally associated with radiation injury.143 Ratios of metabolites are considered, and pooling ratios of different metabolites may be helpful in differentiating tumor from necrosis.150 Diffusion-weighted imaging may also differentiate between necrosis and recurrence, although it can be confounded by surrounding edema. Perfusion imaging techniques that measure rCBV may also help differentiate recurrence from necrosis by allowing for indirect assessment of tumor angiogenesis and vascularity. Hyperperfusion is seen with tumor recurrence, and necrosis is associated with ischemia-related change.143,150 Still, rCBV may be increased in areas of radiation-induced inflammation. Advanced MRI techniques of late radiation-induced injury are reviewed by Pruzincová et al.150

Management of radiation necrosis may be either medical or surgical. Corticosteroids may counteract the vascular endothelial damage and also decrease the inflammatory response.151 Other therapies, such as hyperbaric oxygen,152 anticoagulants,153 and vitamins154 have met with varying degrees of success, and no large trials have been conducted to support their use.155 A promising therapy for brain necrosis is the anti-VEGF agent bevacizumab, which may result in decreased vessel permeability. A recent double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 14 patients with CNS radiation necrosis showed that patients receiving the antibody demonstrated a radiographic response, whereas those treated with placebo did not demonstrate a response. Importantly, all patients treated with bevacizumab showed clinical improvement.156 Surgical exploration often is necessary not only to establish a diagnosis but also as a therapeutic intervention to remove the region of necrosis. Resection reduces mass effect and edema and results in clinical improvement in the majority of patients.143

Neurocognitive Deficits after Cranial Irradiation

Neurocognitive deficits often are observed after cranial irradiation, especially in young children. Many of the sequelae appear several years after treatment of children with brain tumors, which mandates long-term follow-up. Sequential assessments of neurocognitive function demonstrated progressive deterioration during 6 years after radiotherapy in children with ALL who were treated with 18 Gy of whole-brain irradiation.157 Numerous studies of neurocognitive function in children after whole-brain irradiation for ALL have been performed.158–162 In summary, these findings show that whole-brain irradiation can lead to decline in neurocognitive function, an effect that appears to be greater in younger children and with higher doses of radiation (e.g., 24 Gy) but can be seen after treatment with 18 Gy.157 It also is possible that an interaction between methotrexate (intrathecal or high-dose systemic) and whole-brain irradiation causes these late effects.162 In one study, serial intelligence quotient (IQ) examinations were used to follow-up 44 pediatric patients with medulloblastoma who were treated with postoperative radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. At a mean of 5.2 years from completion of radiotherapy, the mean estimated full-scale IQ was greater than one standard deviation below the expected population norm, and a mean loss of 2.55 estimated full-scale IQ points occurred per year. This study suggests that the decline in IQ was not because of a loss of previously known skills and information, but rather an inability to acquire new skills and information at a rate comparable with healthy control subjects.163

Although the major portion of the literature on neurocognitive function after cranial irradiation concerns children, some data on adults are available. Taphoorn and colleagues164 found no significant differences in neurocognitive function between patients with low-grade gliomas who were treated with radiation (45 to 63 Gy) and those who were not treated with radiation. In another retrospective study, young adults with low-grade brain tumors who were treated with 54 to 56 Gy of radiation delivered to limited fields often showed a transient, early delayed drop in neuropsychological performance at 6 months; however, the risk of long-term cognitive dysfunction was low, at least up to 4 years.165

In a North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) randomized study of a dose of 64.8 versus 50.4 Gy for treatment of low-grade gliomas,144 data regarding cognitive performance were collected prospectively. With a median follow-up time of 7.4 years in survivors, the vast majority of patients with normal baseline findings on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) maintained normal findings after undergoing radiotherapy.166 Patients with abnormal MMSE results before radiotherapy were more likely to have an improvement in cognitive abilities than deterioration after being treated with radiotherapy. Armstrong and co-workers167 conducted prospective, comprehensive, longitudinal neuropsychological testing on 26 adult patients with low-grade supratentorial brain tumors, mostly gliomas, who had been treated with radiotherapy. Nine patients underwent testing 6 years after being treated with radiotherapy. No declines were noted on most neurocognitive tests. Seven of the 37 neuropsychological tests showed improvement over 6 years. However, declines emerged only after 5 years on selected tests of cognitive function such as visual memory.

Some evidence indicates that adults treated with brain radiotherapy may experience long-term cognitive sequelae. One study aimed to differentiate causes of cognitive disability—either the tumor itself or various treatments, including radiotherapy, surgery, or medication—in a population of patients with a low-grade glioma at a mean of 6 years from diagnosis. Their findings suggest that the tumor had the greatest deleterious effect on cognitive functioning and that radiotherapy resulted in long-term cognitive disability mostly when high doses per fraction (>2 Gy) were used.168 An update of this study, which assessed cognitive abnormalities at a mean of 12 years after diagnosis, showed that patients who were treated with radiation therapy had greater deficits than did control subjects who did not undergo radiotherapy. The patients who underwent radiation therapy had more deficits in attention functioning at follow-up, regardless of fraction dose, and they also performed worse in tests of executive functioning and information processing speed.169

Data regarding treatment of these cognitive deficits in brain tumor survivors are limited and conflicting. In a randomized trial of 83 childhood survivors of ALL or malignant brain tumors who had problems with academic achievement, the use of methylphenidate was investigated, and it was revealed that the drug at least temporarily reduced some attentional and social deficits.170 However, a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial in patients with a brain tumor failed to show that prophylactic use of methylphenidate improved quality of life or cognitive function.171 A phase 2 trial of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil in patients who received radiation for brain tumors showed improved cognitive functioning, mood, and health-related quality of life after a 24-week course of the drug.172 Cranial transplantation of human stem cells is a treatment currently under investigation in the laboratory. Radiation-induced depletion of stem cells in the brain, especially in the area of the hippocampus, may be partially responsible for radiation-induced cognitive deficits. Using rats subjected to cranial irradiation, researchers have transplanted human embryonic stem cells173 or human neural stem cells174 into the hippocampal formations. Animals receiving stem cells showed superior performance on hippocampal-dependent cognitive tasks.173,174

Another treatment complication associated with cranial radiotherapy is leukoencephalopathy, which is most often associated with intravenous or intrathecal methotrexate and cranial irradiation.141,175 Young age also is an important risk factor; however, leukoencephalopathy can affect all age groups. Histologically, multifocal white matter destruction with loss of myelin can be seen, especially in the periventricular regions; MRI scans show these periventricular abnormalities. CT scans also may reveal the presence of intracerebral microcalcifications due to mineralizing microangiopathy. The clinical expression of leukoencephalopathy ranges from mild evidence of white matter injury on neuroimaging studies to severe necrotizing leukoencephalopathy with profound neurologic impairment and, in some cases, death. Mild or subclinical cases are more common than severe necrotizing leukoencephalopathy. The bulk of the experience comes from children who received 24 Gy of whole-brain radiation along with high doses of intravenous and intrathecal methotrexate. The frequency of leukoencephalopathy is low in patients who receive cranial radiotherapy and intrathecal methotrexate or cranial irradiation and intravenous methotrexate but may be as high as 45% in patients who receive all three treatments.176 In general, methotrexate is most toxic when given during or after radiation.

Cranial irradiation can result in arterial vascular problems such as vessel obliteration or narrowing, resulting in a strokelike syndrome.177 These complications are rare, but when they occur, they are more likely to happen after irradiation of the parasellar region.

Endocrine Deficits after Cranial or Spinal Irradiation

Endocrine problems are common after cranial irradiation, particularly in children.180–180 Such problems include growth hormone deficiency and thyroid and gonadal dysfunction.

The hypothalamus is more radiosensitive than the pituitary gland and is responsible for endocrine dysfunction at lower doses. At higher doses (greater than 40 Gy), however, both the anterior pituitary gland and the hypothalamus contribute to endocrine dysfunction. Of all the hormones, growth hormone is the most likely to show deficiency after irradiation and is seen in a majority of children who have received whole-brain irradiation. One study found that in children with ALL who received a dose of 24 Gy to the whole brain, 56% experienced growth hormone deficiency, whereas no such problems were seen in children who received a dose of 18 Gy, at least 4 years later.181 The latency of onset is dose-dependent and is shorter with higher doses.182 Growth may be further impaired by spinal irradiation, which directly affects the vertebral body growth center.

Precocious puberty may occur after relatively low doses, on the order of 18 Gy.183 Deficiencies in other hormones, such as gonadotropins, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), are rare after doses lower than 40 Gy.179 Thyroid dysfunction is common in patients with brain tumors who are treated with high-dose radiotherapy.184 Constine and associates studied endocrine function in 32 patients with brain tumors not involving the hypothalamic-pituitary region who received 39.6 to 70.2 Gy to this region.185 Hypothalamic or pituitary hypothyroidism developed in 65% of the patients. Fourteen of 23 postpubertal patients (61%) had evidence of hypogonadism as manifested by oligomenorrhea, low estradiol levels, or low testosterone levels. Half of the patients had mild hyperprolactinemia. Subtle abnormalities in adrenal function were seen in 35% of patients.

In patients receiving craniospinal radiation, hypothyroidism also may occur as a result of the exit dose to the thyroid gland. In a study of radiation therapy for brain tumors not involving the hypothalamic-pituitary axis conducted at the Christie Hospital in Manchester, the incidence of hypothyroidism was 15% or 33% (P = .013), respectively, for patients receiving cranial or craniospinal irradiation.186 The mean spinal dose was 29 Gy, and the exit dose to the thyroid gland ranged from 10 to 15 Gy.

Optic Neuropathy after Cranial Irradiation

Irradiation of tumors that are close to the optic nerves or chiasm may result in a sufficient dose to these structures to cause concern about the development of optic neuropathy. Two major classes of optic neuropathy are recognized: anterior optic neuropathy and retrobulbar optic neuropathy.187 The former is thought to be due to vascular injury affecting the nerve head inside the globe anterior or adjacent to the lamina cribrosa. This vascular injury is associated with swelling of the optic head, in contrast with retrobulbar optic neuropathy, which is due to more proximal injury to the optic nerve. Diagnostic criteria for retrobulbar optic neuropathy include (1) visual loss (monocular or binocular) accompanied by corresponding visual field defects, (2) funduscopic examination, which often shows a pale optic disc but without edema, (3) onset 6 months to several years after radiation therapy that delivered a significant dose to the optic nerve/chiasm, and (4) no radiologic evidence of visual pathway compression.188 MRI scans may show pathological contrast enhancement of the region of the optic nerve/chiasm that received a high dose of radiation.189

Parsons and colleagues187 examined radiation-induced optic neuropathy in patients receiving radiation treatment for primary extracranial head and neck tumors. Of 215 optic nerves at risk, these investigators found anterior optic neuropathy in 5 nerves and retrobulbar optic neuropathy in 12 nerves. No injuries were observed in 106 optic nerves that underwent irradiation with less than 59 Gy. The 15-year actuarial risk of optic nerve neuropathy after administration of 60 Gy or more was 11% when daily fractions less than 1.9 Gy were used, versus 47% when 1.9 Gy or more was used.

Although these data suggest that the optic nerve/chiasm tolerance is at least 59 Gy, their population did not include patients with intracranial tumors compressing the optic nerve/chiasm. It is possible in the latter situation that the tolerance of the optic nerve/chiasm is lower as a result of ischemic injury. In some patients with pituitary adenomas or craniopharyngiomas treated with radiation, optic neuropathy developed after doses as low as 45 to 50 Gy, although in many of these cases the daily fraction size was greater than 2 Gy.188,190,191 On the basis of these results, most investigators currently recommend limiting the optic chiasm/nerve dose to 50 Gy in 1.8- to 2-Gy fractions in the treatment of pituitary adenomas or craniopharyngiomas. For other brain tumors requiring higher doses, most radiation oncologists would try to restrict the optic nerve/chiasm dose to 54 Gy or lower. In one series in which the risk of optic neuropathy after stereotactic radiosurgery was examined, a risk of 1.1% for patients receiving 12 Gy or less was found, and the risk was increased in patients who received previous or concurrent external beam radiation therapy.192 A conservative estimate for single-dose tolerance of the optic nerve/chiasm in stereotactic radiosurgery is 8 Gy.193 Adherence to these guidelines should keep the risk of radiation-induced optic neuropathy extremely low (1% or less) but unfortunately will not completely eliminate it. Possible treatments include use of hyperbaric oxygen, corticosteroids, or anticoagulation, but none is particularly effective.194

Second Malignant Neoplasms Developing after Cranial Irradiation

Second malignant neoplasms including malignant gliomas and meningiomas remain relatively uncommon consequences of radiation therapy for brain tumors.8,195 Concern exists that the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy may increase the risk of second malignancies in long-term survivors of childhood brain tumors.17,18 This outcome may be especially true after prolonged use of alkylating agents and etoposide with or without irradiation.

Myelopathy after Spinal Irradiation

A delayed early effect that can be seen after irradiation of the cervical spine is Lhermitte syndrome, which is characterized by an electric shock–like sensation precipitated by forward neck flexion.196 The symptoms typically start weeks to a few months after completion of radiation therapy. They are maximal at first but abate with time, without the development of any objective signs. The paresthesias most commonly occur in the lumbosacral region but also can involve the upper and lower extremities and the upper back. This transient form of Lhermitte syndrome can occur after doses of radiation well within accepted spinal cord tolerance and is not associated with any permanent late sequelae. The pathogenesis is thought to involve an inhibitory effect on oligodendrocytes that results in transient reversible demyelination. A more ominous form of Lhermitte syndrome can manifest after a longer latency period after completion of radiation therapy (at least a year), which then progresses to chronic radiation myelopathy.

Chronic myelopathy is the most catastrophic late effect that can occur after spinal cord irradiation. Nearly half of the affected patients will die from complications.197 A biphasic distribution in the latency period from irradiation to the onset of myelopathy has been observed. The early peak is from 12 to 14 months, and the second peak is from 24 to 28 months. The pathological insults that lead to myelopathy include damage to oligodendroglial cells, causing demyelination and white matter necrosis, and death of endothelial cells, resulting in vascular injury. In some patients, partial neurologic dysfunction develops; others progress to complete paraplegia or quadriplegia. No clinical or radiologic findings are pathognomonic for radiation-induced myelopathy. Therefore the diagnosis usually is made by a combination of (1) neurologic abnormalities corresponding to a level just below the irradiated region, (2) a history of spinal cord irradiation with a high total dose (greater than 45 Gy) at least 6 months before the onset of signs and symptoms, (3) MRI findings of increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images in the irradiated region,198 and (4) exclusion of other etiologic factors. The MRI findings in spinal cord myelopathy can mimic tumor recurrence with gadolinium enhancement on MRI.

The probability of developing chronic radiation myelopathy is dependent not only on the total dose delivered to the spinal cord but also on the fraction size. Larger fraction sizes are associated with more severe later effects (Schultheiss and associates139). Using standard fraction sizes (1.8 to 2 Gy per day), a commonly observed limit for dose to the spinal cord is 45 Gy. In a study of the incidence of myelitis after irradiation of the cervical cord, Marcus and Million199 found that of 1112 patients, chronic radiation myelopathy developed in only 2 (0.18%). This complication developed in 2 out of 471 patients (0.42%) receiving between 45 and 50 Gy. Myelitis developed in none of the 442 patients who received between 40 and 45 Gy and none of the 75 patients who received more than 50 Gy. The investigators’ conclusion was that even with doses of up to 50 to 55 Gy to the cervical cord, the likelihood of developing chronic myelopathy was extremely low. Even if the spinal cord dose is limited to 45 Gy, myelitis may still develop. This report cited published cases in which myelitis developed with doses less than 45 Gy or even less than 40 Gy, given in 1.8- to 2-Gy daily fractions. Such cases, however, are extremely rare, with an estimated risk of 0.2% or less for the development of chronic myelopathy at this dose.139 No effective treatment exists for this condition, and only case reports are found in the literature suggesting possible instances of benefit with growth factors, anticoagulation, and bevacizumab.

General Principles of Chemotherapy

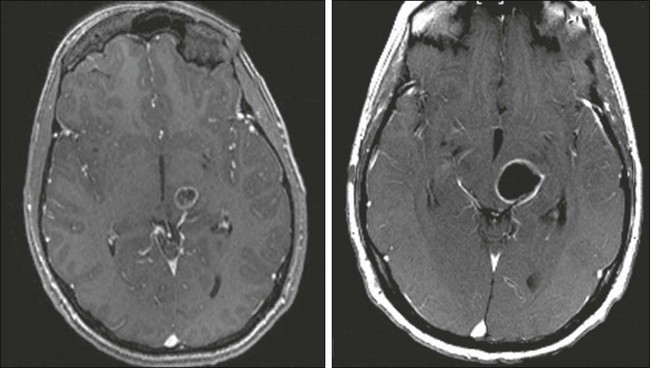

Complicating assessment of chemotherapy in patients with a brain tumor is the observation that corticosteroids also often reduce MRI contrast enhancement and relieve symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish chemotherapy effects from corticosteroid effects. For almost 20 years, standard response criteria have been the Macdonald criteria, which use two-dimensional measurements of enhancing tumor and account for corticosteroid use and clinical status. However, it has been recognized recently that reliance on contrast enhancement is a limitation in many anaplastic gliomas. Two situations in particular have led to the development of a new set of response criteria (Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology, or RANO). First, pseudoprogression is defined as an increase in contrast enhancement or edema on MRI without true tumor progression, a phenomenon made more common by the addition of temozolomide to radiotherapy.200,201 The first postradiation MRI shows increased contrast enhancement in up to 50% of patients (see Fig. 66-7), in half of whom the enhancement eventually subsides. The phenomenon may be asymptomatic but can also cause neurologic decline. Failure to recognize pseudoprogression may cause the physician to prematurely terminate effective therapy.202,203 Second, pseudoregression refers to a decrease in contrast enhancement on MRI without true response, a phenomenon increasingly seen in patients treated with VEGF pathway antiangiogenic agents.204 Infiltrative tumor may be distinguished from radiation-related FLAIR and T2 signal MRI changes by diffusion-weighted MRI sequences that show diffusion restriction in areas infiltrated by neoplastic cells.205

Similarly, confusion may arise when neuroimaging documents enlargement of a mass after stereotactic radiosurgery that may progress over many months. Because PET scanning may not reliably distinguish radiation necrosis from tumor progression, the results of concurrent chemotherapy may be ambiguous. Multicentric recurrence outside original radiation fields and after temozolomide appears to be more common when patients have positive O6-methylguanine DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status.206,207