Chapter 29 Bile duct exploration and biliary-enteric anastomosis

Anatomy

Safe operative planning and technique demand a comprehensive understanding of the extrahepatic biliary anatomy and a thorough appreciation for the common anatomic variants that may be encountered. Hepatobiliary anatomy is discussed at length in Chapter 1B; in this section, we will highlight specific aspects deserving of additional emphasis.

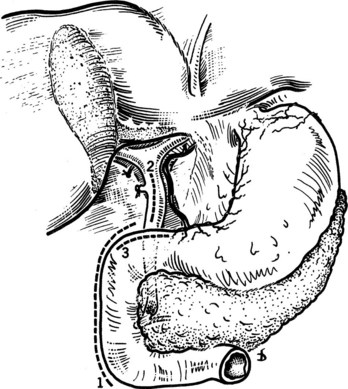

The typically short extrahepatic course of the right hepatic duct makes operative access to the segmental or sectional drainage of the right hemiliver rather difficult. However, the biliary anatomy of the right hemiliver is rather prone to variation, and aberrant drainage from the right anterior or posterior section may assume a long extrahepatic course before joining with the left hepatic ductal system. In comparison, the left biliary system is relatively consistent. Also in contrast to the right, the left hepatic duct invariably has a longer extrahepatic course as it runs along the undersurface of segment IVb (Fig. 29.1). In cases where the base of segment IVb is broad, the left hepatic duct assumes a longer and more transverse course; in cases where the base of segment IVb has a narrower and pyramidal configuration, the course of the left hepatic duct is shorter and more oblique. Drainage from most of segment I enters into the left hepatic duct just before its convergence with the right hepatic duct; drainage from the right portion of segment I typically enters into the right posterior sectoral duct. The left hepatic duct runs along the left portal vein within a peritoneal reflection of the gastrohepatic ligament, and it is best exposed by lowering the hilar plate along the base of segment IVb (Fig. 29.2). These structures are joined by the left hepatic artery as they enter the umbilical fissure, where arterial and venous branches to and biliary ducts from segments II, III, and IV are found. The ligamentum teres along the lower edge of the falciform ligament runs across the umbilical fissure, which is often covered by a bridge of hepatic tissue that crosses from the left lateral section to the base of segment IV. This bridge of tissue must often be divided to permit full exposure of and access to the biliary and vascular structures to and from segments II, III, and IV (Fig. 29.3).

FIGURE 29.1 Diagrammatic expanded view of the liver showing its segmental structure. Elements of the portal triad are distributed to the right and left liver on a segmental basis. The left hepatic duct always pursues an extrahepatic course beneath the base of the quadrate lobe (segment IV) in the groove separating the quadrate from the caudate lobe (segment I; see Fig. 29.2). The ligamentum teres marks the umbilical fissure and runs to join the umbilical portion of the left branch of the portal vein. Each portal triad is composed of hepatic artery, portal vein, and biliary duct. Note the distribution of the left portal triad in the umbilical fissure; major branches recurve to the quadrate lobe medially, and two major branches pursue a lateral course to segments II and III of the left lobe.

FIGURE 29.2 Sagittal section showing the relationship of the quadrate (Q) and caudate lobe (CL) to the left portal triad, which is encased within a reflection of the lesser omentum that fuses with the Glisson capsule at the base of the quadrate lobe. The arrow indicates the point of incision for the dissection to lower the hilar plate (see also Fig. 29.5). A, Left hepatic duct. B, Left branch, portal vein. Note the left hepatic artery (C) joins the left duct and left branch of the portal vein at the umbilical fissure.

FIGURE 29.3 The bridge of liver tissue frequently present between the base of the quadrate lobe (segment IV) and the left lobe of the liver can be divided. This is conveniently done by passing a curved director beneath it and cutting it with diathermy. Such division can be useful in aiding an approach to the left hepatic duct, particularly if the course of the duct is vertical and the base of the quadrate lobe is short. If the bridge of tissue is present, the maneuver is always necessary to allow dissection of the segment III duct (see Fig. 29.8).

Bile Duct Exploration

Overview

The most common indication for exploration of the biliary system is the presence of common bile duct stones. Contemporary percutaneous and endoscopic techniques have largely replaced operative interventions for this indication, and nonoperative, laparoscopic, and open operative strategies are addressed in greater detail in Chapters 34, 35, and 36, respectively. In this chapter, we highlight the various operative approaches for open exploration of the bile ducts.

Incision and Exposure

A right subcostal incision generally affords satisfactory exposure of the extrahepatic biliary system. The hepatic flexure of the right hemicolon is mobilized, and the proximal transverse colon is mobilized off the duodenum. Downward retraction of the proximal transverse colon facilitates exposure of the duodenum, whose retroperitoneal attachments are freed with a generous Kocher maneuver. A cholecystectomy is often performed in conjunction with bile duct exploration for patients with calculous disease, and removal of the gallbladder greatly enhances exposure of and access to the porta hepatis. Alternatively, retraction of the mobilized gallbladder can be useful for exposing the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct. Cephalad retraction of the undersurface of the liver along the base of segment IVb also enhances optimal visualization of the extrahepatic biliary system (Fig. 29.4).

FIGURE 29.4 The initial line of incision for an approach to the left hepatic duct by lowering of the hilar plate. The liver is elevated, and the quadrate lobe is retracted upward. The incision is made at precisely the point at which the Glisson capsule reflects to the lesser omentum (see Fig. 29.2).

Supraduodenal Exploration (See Chapter 35)

Choledochotomy

Open exploration of the extrahepatic biliary system is best undertaken through a longitudinal distal choledochotomy. Opening the common bile duct distally toward the duodenum facilitates exploration of the distal biliary system and permits easy construction of a choleodochoduodenostomy, if necessary. Care must be taken to verify the anatomic relationship between the cystic duct and common bile duct, as low or anterior insertion of the cystic duct can result in unintended injury to this structure (Fig. 29.5). Placement of the incision in an anterior location minimizes the risk of injury to the periductal vasculature, which typically runs along the medial and lateral aspects of the common hepatic and common bile ducts. The length of the choledochotomy is dictated by the diameter of the duct and the size of the stones present within its lumen, but length typically ranges between 1 to 2 cm.

A number of options exist for bile duct exploration, and these are discussed in further detail in Chapters 34 and 35; regardless of the method used, care must be taken to be as atraumatic as possible (Orloff, 1978). Iatrogenic injury to the duct mucosa can result in delayed stricture formation, and inaccurate delivery of rigid instrumentation can create false passages into the duodenum or pancreas. Fiberoptic choledochoscopy permits excellent visualization when saline is infused at a low rate through the endoscope. This is particularly effective for exploring the smaller intrahepatic radicles of the proximal biliary system.

Transduodenal Exploration

In unusual cases in which gallstones are impacted at or near the ampulla of Vater, or in patients whose surgically altered anatomy makes endoscopic techniques difficult (e.g., after Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy), transduodenal exploration may be warranted. Transduodenal access to the distal biliary system requires operative sphincterotomy, which in turn requires operative sphincteroplasty to avoid postoperative papillary stenosis. Chapter 62C discusses transduodenal resections for neoplastic disease, the details of which are not dissimilar to the approach used for calculous disease (see Chapter 35).

Outcomes After Bile Duct Exploration

Advances in endoscopic and percutaneous approaches have vastly limited the indications for operative bile duct exploration. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that historical analyses have largely substantiated the safety and efficacy of operative bile duct exploration. In a representative single-center North American series of 100 consecutive, open, supraduodenal common bile duct explorations, no operative mortalities were encountered, and the overall morbidity rate was 15.7%, including a 5.3% rate of retained common duct stones (Pappas et al, 1990). Similar observations have been reported in retrospective analyses of transduodenal sphincteroplasties and common bile duct explorations (Kibria & Hall, 2002; Morgan et al, 2008; Sellner et al, 1988), highlighting low rates of morbidity and recurrent choledocholithiasis.

Biliary-Enteric Anastomosis

Overview

For this reason, preoperative planning must incorporate comprehensive radiographic evaluation of the relevant biliary anatomy; these strategies and techniques are addressed in Chapters 13, 16, 17, and 18. In some cases, preoperative insertion of percutaneous transhepatic biliary stents may facilitate intraoperative identification of the right or left hepatic ducts. However, it is important to recognize that stent insertion is associated with a risk of procedural complications and inevitably results in bacterial contamination of the biliary tree that can lead to cholangitis and periductal inflammatory changes that may delay or hinder operative intervention. Because of these risks, and because the hepatic ducts can be identified without stents at the time of operative exploration, we have not routinely used preoperative biliary stents. When undertaken, caution must be exercised to avoid attempted percutaneous drainage if it is unlikely that the stent can be placed across the obstructing lesion. Insertion of a percutaneous drain into an excluded biliary segment will result in bacterial colonization of static bile; if that hepatic segment cannot be decompressed by a subsequent operative intervention, it will not be possible to remove that external drain without risking refractory cholangitis.

Incision and Exposure

A right subcostal incision with or without an upper midline extension or left subcostal extension provides adequate exposure for construction of the biliary-enteric anastomosis. Use of retractors capable of upward elevation and cephalad retraction of the costal edges are quite valuable for optimizing visual exposure of the relevant hilar anatomy. Division of the ligamentum teres and mobilization of the falciform ligament off the anterior surface of the liver also facilitate operative exposure; anterocephalad retraction of the ligamentum teres and division of the bridge of tissue overlying the umbilical fissure are critical for optimal visualization of the vascular inflow and biliary drainage of segments II, III, and IV (see Fig. 29.3).

If direct surgical decompression of the gallbladder is not to be undertaken, cholecystectomy will also facilitate access to the extrahepatic biliary system by exposing the cystic duct, which can be followed to its origin off the common hepatic duct or right hepatic duct. Cholecystectomy also exposes the cystic plate, which runs in continuity with the hilar plate. Lowering of the hilar plate permits exposure of the left hepatic duct as it courses along the base of segment IVb. In cases of unilateral hepatic atrophy as a result of long-standing biliary obstruction or preoperative portal vein embolization, it is critical to understand that the normal anatomic relationships of the portal structures are altered. In the more common circumstance of right-sided atrophy, the portal and hilar structures are rotated posteriorly and to the right; as a result, the portal vein, which is typically most posterior, is often encountered first; meticulous dissection is necessary to identify the common bile duct and hepatic duct deep within the porta hepatis (Pottakkat et al, 2009).

Hepaticojejunostomy

Approach to the Right Hepatic Duct

A plane of dissection between the Glisson capsule along the base of segment IVb and the peritoneal reflection enveloping the porta hepatis is developed, effectively lowering the hilar plate. In this way, the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts may be exposed (see Fig. 29.4). If the extrahepatic course of the right hepatic duct is too short to be visualized in this way, as is often the case, the intrahepatic right portal pedicle may be exposed through hepatotomies created along the base of the gallbladder fossa and the caudate process (see Chapter 90A; Launois & Jamieson, 1992). The right portal pedicle may be encircled and delivered, and further mobilization can permit delivery of the right anterior and posterior sectional ducts (see Fig. 29.5).

Approach to the Left Hepatic Duct

The ligamentum teres is ligated with a firm tie and divided to permit anterocephalad retraction; this enhances exposure of the undersurface of the left hemiliver (see Fig. 29.3). The left hepatic duct runs with the left portal vein within a peritoneal reflection along the undersurface of the left hemiliver and is best approached by lowering the hilar plate (Fig. 29.6; Blumgart & Kelley, 1984). This dissection is greatly facilitated by placing a curved or malleable retractor to elevate and retract segment IVb in an anterocephalad direction.

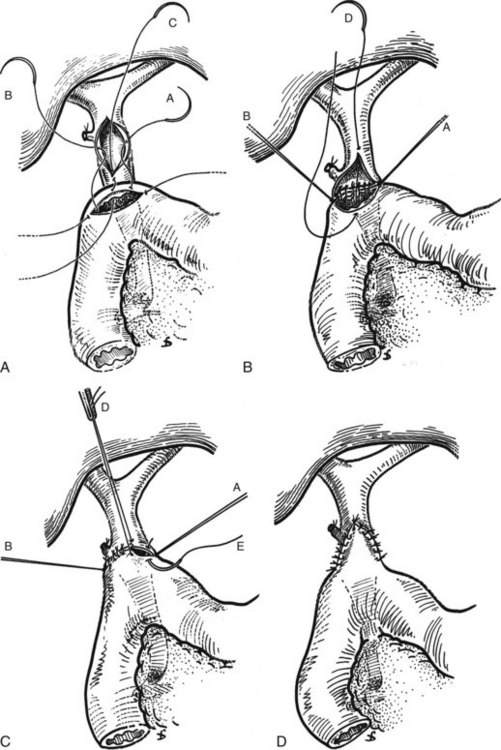

Approach to the Segment III Hepatic Duct

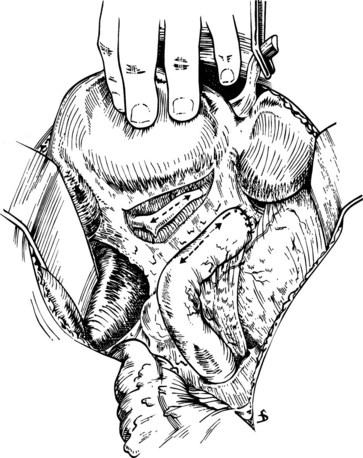

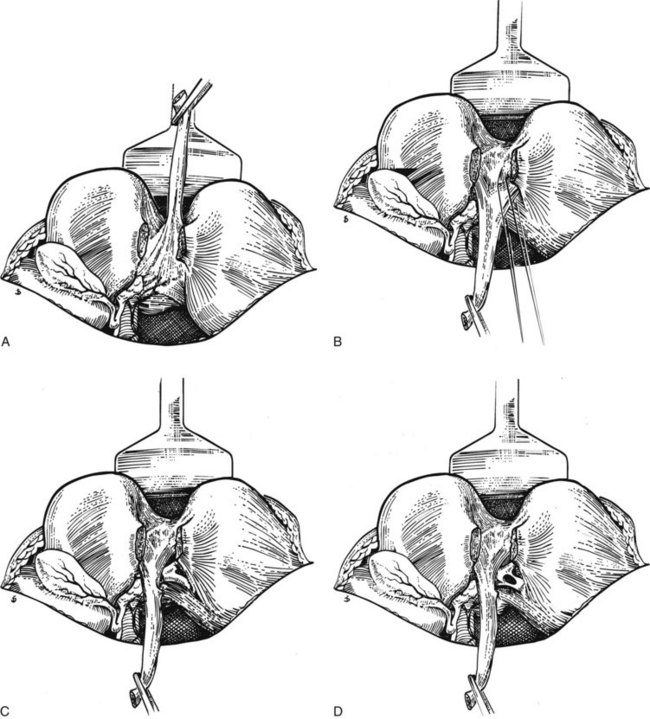

On occasion, the presence of bulky, irresectable tumor along the hepatic hilus may make operative exposure in that region impermissible. In this circumstance, access to the left hepatic duct upstream of the point of obstruction may provide a means of adequately draining the obstructed liver. This can be achieved by exposing the left hepatic duct within the umbilical fissure (Bismuth & Corlette, 1975; Voyles et al, 1983). If the left hemiliver has not atrophied from long-standing biliary obstruction, unilateral left-sided biliary drainage will effectively relieve obstructive jaundice and restore adequate hepatic function, even when the biliary drainage of the excluded right hemiliver remains completely obstructed (Baer et al, 1994). As before, the ligated falciform ligament is elevated, and the bridge of hepatic tissue overlying the umbilical fissure (if present) is divided to optimize exposure of the segment III duct. This can be facilitated by dividing the liver tissue along the left of the ligamentum teres, through which the segment III duct may be exposed and opened without fear of injury to the vascular inflow to segment III (Fig. 29.7). On occasion, a wedge resection of a portion of segment III can also be performed to provide exposure of the segment III duct (Fig. 29.8).

FIGURE 29.7 A, The liver is held up so that its inferior surface is seen. The bridge of liver between the quadrate lobe and the left lobe of the liver has been divided. The base of the ligamentum teres is seen. B, The ligamentum teres is then pulled downward. The peritoneum of its upper surface on the left side is incised, and the extensions passing into the liver are exposed. The left sides of these extensions are divided between ligatures, which must be passed carefully using aneurysm needles. This part of the dissection is tedious and should be carried out meticulously because hemorrhage within the recess adjacent to the segment III duct can be difficult to control. C, The segment III duct is exposed. D, The duct is opened longitudinally for anastomosis, which is carried out by the technique illustrated in Fig. 29.13.

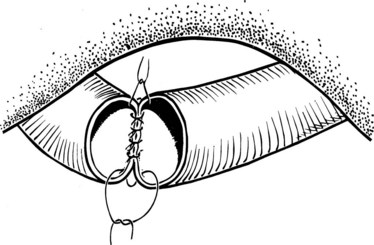

Anastomotic Technique

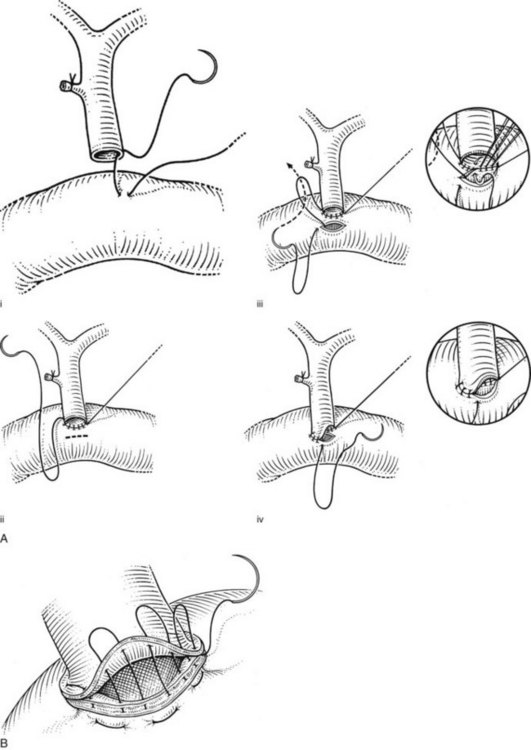

We have used a standardized technique for hepaticojejunostomy that can be applied for nearly all circumstances of proximal biliary drainage. This technique is of particular utility for difficult high anastomoses, where duct mobility and size are limited. A 70-cm Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum is prepared and delivered through a transverse mesocolonic defect fashioned to the right of the middle colic vessels. A small jejunotomy, whose diameter is slightly smaller than that of the duct, is cut at the site of planned anastomosis. We do not typically use transanastomotic stents, but if a stent is to be used, it is preferable to pass it through the cut hepatic duct prior to construction of the anastomosis. The stent is affixed against the duct wall with a single 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable catgut suture, which is tied on the outside of the duct wall (Fig. 29.9); this maneuver helps to avoid inadvertent dislodgment of the tube during placement of the anastomotic sutures.

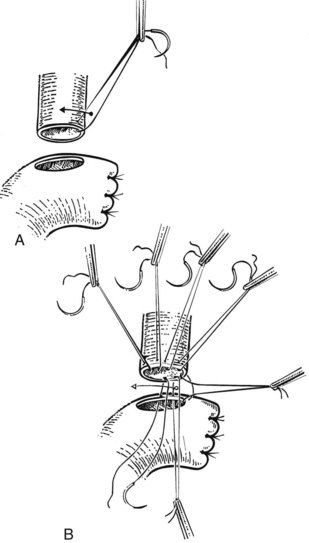

When more than one biliary duct orifice is present, every effort should be made to approximate them with a row of 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures so that they may be treated as a single duct for anastomotic purposes (Fig. 29.10). Anastomotic construction begins with an anterior row of 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures placed along the hepatic duct only, working from left to right. In cases where the duct orifice is small, interrupted sutures should be used. The needles are left on the sutures, which are then retracted in a cephalad direction so as to enhance exposure of the posterior duct wall. A posterior row of full-thickness sutures securing the duct mucosa to the jejunal mucosa is then placed, again working from left to right. Once this row is completed, the sutures are pulled to bring the duct and jejunum into close apposition. The anterior sutures are again retracted to facilitate exposure of the posterior wall of the anastomosis, the posterior sutures are tied, and all but the right and left corner stay sutures are cut. The anterior row of the anastomosis is then completed by suturing the remaining needles to the jejunum, working from right to left. These sutures are left untied so as to maximize exposure of the duct lumen; once this row is completed, the sutures are tied to complete the anastomosis (Fig. 29.11).

Choledochojejunostomy

Anastomotic Technique

The hepaticojejunostomy or choledochojejunostomy can be performed in an end-to-side or a side-to-side manner. When undertaken in an end-to-side manner, a cholecystectomy is performed, and the common hepatic duct or common bile duct is encircled at the point of planned transection. The duct is sharply transected, the endobiliary stent (if present) is removed, and a specimen of bile may be aspirated for microbiologic analysis. The distal aspect of the duct is oversewn with 3-0 absorbable suture, and a 70-cm Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum is prepared for construction of the biliary-enteric anastomosis to the proximal aspect of the duct. The posterior wall of the duct is sutured against the jejunum with a running row of 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable sutures. A corresponding jejunotomy is fashioned just opposite the duct, and a series of interrupted 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable sutures are used to approximate the exposed mucosa along the posterior wall of the jejunotomy against the posterior wall of the duct. The anterior row of the anastomosis is then completed with the running sutures used to construct the posterior row (Fig. 29.12). We use a single row of sutures; placement of a second layer merely introduces the risk of excessively narrowing the lumen of the anastomosis. Of course, care must be taken to ensure that the sutures are secured tightly and placed at close intervals so as to avoid bile leakage. Placement of a sponge circumferentially around the completed anastomosis provides an intraoperative opportunity to ensure the absence of a significant leak.

Alternatively, the side-to-side anastomosis is initiated by placing stay sutures of 4-0 absorbable suture along either side of the planned longitudinal ductotomy, which is fashioned sharply. The biliary-enteric anastomosis is then constructed to a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb using a technique similar to that used for the choledochoduodenostomy (described below). Potential advantages of the side-to-side anastomosis include less devascularization of the untransected duct and the retention of biliary-duodenal continuity, in those circumstances in which future endoscopic retrograde cholangiographic procedures may be desirable (Winslow et al, 2009).

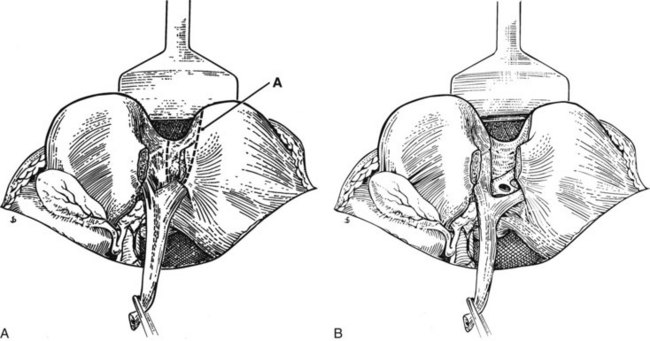

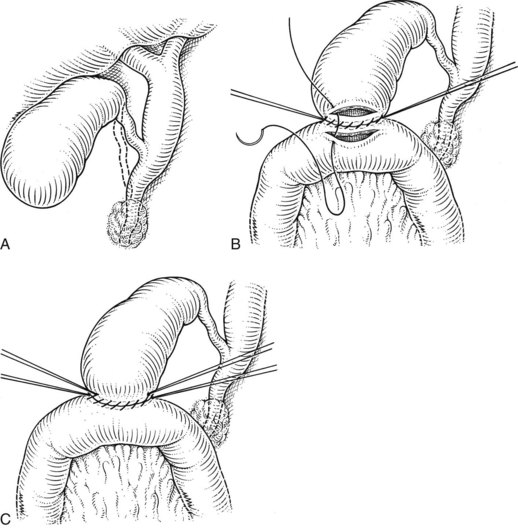

Choledochoduodenostomy

The choledochoduodenostomy can also be a useful operative maneuver when a distal periampullary stricture is present. It is most commonly performed after common bile duct exploration for calculous disease; in this way, a supraduodenal choledochotomy may be anastomosed to a duodenotomy instead of to an external T-tube. In this procedure, a longitudinal choledochotomy is made, through which the extrahepatic biliary system may be explored. For optimal anastomosis, the duct opening should measure at least 2.5 cm in length; this will typically require extension onto the common hepatic duct. A generous Kocher maneuver is performed to permit easy mobility of the duodenum, and a longitudinally oriented duodenotomy is made along the superior aspect of the postbulbar duodenum. Because of the flexibility of the duodenal wall, the duodenotomy may be considerably shorter in length than the ductotomy (Fig. 29.13). Three corner 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures are placed between the ends of the duodenotomy and the midpoints of the ductotomy and between the distal end of the ductotomy and the midpoint of the posterior aspect of the duodenotomy. Retraction of these sutures reorients the distal portion of the ductotomy transversely, which facilitates placement of the posterior row of sutures. The fourth corner suture is then placed between the proximal end of the ductotomy and the midpoint of the anterior aspect of the duodenotomy. Retraction of this suture tents the remaining anterior wall of the anastomosis forward, which facilitates placement of the anterior row of sutures (Fig. 29.14). As with the hepaticojejunostomy and choledochojejunostomy, a single row of sutures is used.

Cholecystoduodenostomy and Choledochojejunostomy

An alternative approach to cases of distal biliary obstruction is direct drainage of the gallbladder. High rates of patency failure have been documented, particularly with cholecystoduodenostomy; as a result, we typically do not use this procedure except when advanced malignancy mandates the use of a simple operative intervention (Dayton et al, 1980). Cholecystoenterostomy for palliative biliary decompression is particularly suitable where major tumoral obstruction obscures access to the porta hepatis. Prior to undertaking cholecystoenterostomy, it is imperative to confirm that the extrahepatic biliary obstruction does not extend to the level of the cystic duct insertion. In addition, the presence of significant stone burden within the gallbladder makes this operative strategy less attractive.

The gallbladder is almost invariably distended in patients who are appropriate candidates for cholecystoenterostomy. The gallbladder and cystic duct are carefully evaluated to confirm that the cystic duct does not insert distally into the common bile duct at the level of tumoral obstruction. If cholecystoduodenostomy is undertaken, a generous Kocher maneuver is performed to permit sufficient mobility of the duodenum. If cholecystojejunostomy is planned, a loop of jejunum is utilized; we do not routinely use construction of a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb for this purpose. The gallbladder fundus is secured to the small bowel with a row of 3-0 sutures, a longitudinal cholecystotomy is fashioned, and bile is aspirated. Any stones present in the lumen of the gallbladder are evacuated, and a bile specimen may be sent for microbiologic analysis. Decompression of the common hepatic duct is confirmed, and a corresponding longitudinal enterotomy is fashioned opposite the cholecystotomy. An anterior row of sutures is then placed to complete the anastomosis (Fig. 29.15).

Outcomes after Biliary-Enteric Anastomosis

Longitudinal analyses of outcomes after biliary-enteric anastomosis for benign and malignant diseases confirms the safety and efficacy of the operative approaches outlined in this section (Chapman et al, 1995; Jarnagin et al, 1998; Moraca et al, 2002; Tocchi et al, 1996). Comparative analyses of effectiveness of the various surgical options are limited, but short-term perioperative morbidity and long-term patency appear favorable after segment III bypass when compared with bypasses to the right sectoral ducts. Of note is a measurable incidence of cholangiocarcinoma after biliary-enteric anastomosis; long-term follow-up of 1003 patients who underwent biliary bypass for benign disease identified 55 cases (5.5%) of primary bile duct cancer after intervals of 132 to 218 months (Tocchi et al, 2001).

Baer HU, et al. The effect of communication between the right and left liver on the outcome of surgical drainage for jaundice due to malignant obstruction at the hilus of the liver. HPB Surg. 1994;8:27-31.

Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastmosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1975;140:170-178.

Blumgart LH, Kelley CJ. Hepaticojejunostomy in benign and malignant high bile duct stricture: approaches to the left hepatic ducts. Br J Surg. 1984;71:257-261.

Chapman WC, et al. Postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures: management and outcome in 130 patients. Arch Surg. 1995;130:597-602.

Dayton MT, Traverso LW, Longmire WPJr. Efficacy of the gallbladder for drainage in biliary obstruction: a comparison of malignany and benign disease. Arch Surg. 1980;115:1086-1089.

Jarnagin WR, et al. Intrahepatic biliary enteric bypass provides effective palliation in selected patients with malignant obstruction at the hepatic duct confluence. Am J Surg. 1998;175:453-460.

Kibria S, Hall R. Recurrent bile duct stones after transduodenal sphincteroplasty. HPB (Oxford). 2002;4:63-66.

Launois C, Jamieson GG. The importance of Glisson’s capsule and its sheath in the intrahepatic approach to resection of the liver. Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1992;174:4-10.

Moraca RJ, et al. Long-term biliary function after reconstruction of major bile duct injuries with hepaticoduodenostomy or hepaticojejunostomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:889-893.

Morgan KA, Romagnuolo J, Adams DB. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty in the management of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreas divisum in the modern era. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:908-914.

Orloff M. Importance of surgical technique in prevention of retained and recurrent bile duct stones. World J Surg. 1978;2:403-410.

Pappas TN, Slimane TB, Brooks DC. 100 consecutive common duct explorations without mortality. Ann Surg. 1990;211:260-262.

Pottakkat B, et al. Surgical management of patients with post-cholecystectomy benign biliary stricture complicated by atrophy-hypertrophy complex of the liver. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:125-129.

Sellner FJ, Wimberger M, Jelinek R. Factors affecting mortality in transduodenal sphincteroplasty. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:23-27.

Tocchi A, et al. The long-term outcome of hepaticojejunostomy in the treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Ann Surg. 1996;224:162-167.

Tocchi A, et al. Late development of bile duct cancer in patients who had biliary-enteric drainage for benign disease: a follow-up study of more than 1,000 patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:210-214.

Voyles CR, et al. Carcinoma of the proximal extrahepatic biliary tree: radiologic assessment and therapeutic alternatives. Ann Surg. 1983;197:188-194.

Winslow ER, et al. “Sideways”: results of repair of biliary injuries using a policy of side-to-side hepatico-jejunostomy. Ann Surg. 2009;249:426-434.