Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Cancer

Ariela Noy, Mark Dickson, Roy M. Gulick, Joel Palefsky, Paul G. Rubinstein and Elizabeth Stier

• Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), Kaposi sarcoma (KS), cervical cancer, and anal cancer all occur with increased incidence in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). NHL, KS, and cervical cancer are acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) defining.

• KS occurs in HIV-infected patients who also are infected with KS-associated herpesvirus. Outside of Africa and in some Mediterranean populations, KS occurs mainly in men who have sex with men.

• Lymphoma (non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin) occurs in all HIV risk groups. These neoplasms tend to be aggressive and extranodal and manifest at an advanced stage. Burkitt lymphoma and HL tend to occur in patients with higher CD4 counts (typically greater than 200 cells/µL), whereas primary central nervous system lymphoma tends to occur in patients with very low CD4 counts (typically less than 50/mm3).

• The CD4 T-cell count and HIV load should be determined for all malignancies. Use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) should be optimized, possibly during but certainly after cancer therapy.

• KS is always associated with KS-associated herpesvirus; immunocompromise, inflammatory cytokines, and perhaps the HIV TaT protein contribute to pathogenesis.

• Lymphoma in HIV-infected patients is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in approximately half of the cases; immunocompromise, chronic antigen stimulation, and perhaps inflammatory cytokines and chemokines contribute to pathogenesis.

• Cervical and anal cancer require the oncogenic strains of human papilloma virus. The pathogenesis of these two cancers is remarkably similar.

• A biopsy is indicated to confirm diagnosis.

• A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen is also indicated.

• Gastrointestinal endoscopy is performed if clinically indicated.

• Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and treatment of opportunistic infections sometimes are associated with regression of KS.

• If disease is symptomatic or rapidly progressive, or with visceral involvement, systemic therapy with liposomal anthracycline or paclitaxel is instituted; all patients should receive pneumocystis prophylaxis. Hematopoietic growth factors, antifungal treatment, and antiherpesvirus prophylaxis or treatment also are appropriate for most patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy.

• If disease is indolent and antiretroviral therapy has just been initiated or major changes have been made, observation may be appropriate.

• For a few lesions, topical therapy, injection of lesions, or radiation therapy may be adequate treatment.

• For persons with systemic disease, consider interferon, thalidomide, or experimental therapy.

• Signs and symptoms of tumor lysis.

• Extent of disease can be determined with use of CT and bone marrow biopsy in most cases.

• Extranodal and atypical presentations of lymphoma are common, as are constitutional symptoms (especially with HL).

• Positron emission tomography scans with fluorodeoxyglucose labeling should be interpreted with extreme caution because HIV infection, inflammation associated with opportunistic infection, and immune reconstitution syndrome all are associated with fluorodeoxyglucose activity.

• Chemotherapy (with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin [doxorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], and prednisone [CHOP] plus rituximab or etoposide, Oncovin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone [EPOCH] plus rituximab) is used to treat NHL.

• Intrathecal prophylaxis is appropriate for patients with Burkitt lymphoma or Burkitt-like lymphoma, for patients with bone marrow involvement of NHL, and for patients with EBV-associated NHL. Either cytarabine or methotrexate can be used for this purpose.

• Patients with relapsed lymphoma may be appropriate candidates for high-dose therapy with stem cell rescue.

• HIV-associated classic HL occurs in patients with higher CD4 counts. It is 80% to 100% associated with EBV. Patients are seen with more advanced disease and more aggressive histologies (mixed cellularity and lymphocyte-depleted HL).

• Staging and evaluation are similar to that for NHL.

• Treatment with doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) results in an overall survival rate at 5 years of 75% (15% below that of the non-HIV population).

• Prevention of invasive disease by screening for and treatment of preinvasive disease is the mainstay in the developed world.

• Staging requires both visualization of the cervical area and CT scanning.

• Treatment depends heavily on the extent of disease because it varies from colposcopic therapies to surgery alone or in combination with radiation and chemotherapy.

• Early stages are treated with curative intent.

• Distantly metastatic disease is largely treated for palliation.

• Prevention of invasive disease by screening for and treatment of preinvasive disease is an active area of research because the progression rates are under investigation.

• Staging requires both visualization of the anal area and CT scanning.

• Treatment of preinvasive lesions varies among practitioners and is an active area of investigation.

• Treatment depends heavily on the extent of disease because it varies from local therapies to surgery alone or in combination with radiation and chemotherapy.

• Early stages are treated with curative intent.

• Distantly metastatic disease is largely treated for palliation, although some patients with only local nodal metastases may be cured.

• Hepatitis B and C virus promote hepatocellular cancer. HIV infection dramatically accelerates this process, although hepatocellular cancer is not an AIDS-defining cancer.

• Early-stage disease is amenable to curative resection or possibly liver transplantation. For larger tumors, multiple tumors, or extrahepatic metastases, systemic chemotherapy is required. Specific approaches in the setting of HIV have not been studied.

• Pneumocystis prophylaxis is given regardless of the CD4 count.

• Other prophylaxis for bacteria, fungi, herpes viruses, and mycobacterium depend on the regimen and level of preexisting immunosuppression.

• In HAART-naive patients, antiretroviral therapy should typically be initiated shortly after cytotoxic chemotherapy begins and when associated nausea is controlled.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a true pandemic, that is, an infection that affects persons in every country of the world.1 HIV is transmitted most commonly worldwide by sexual contact and also by intravenous drug use, transfusion of infected blood or blood products, and perinatally from an infected mother to her child. HIV may be transmitted by infected blood, blood products, bloody fluids, or genital secretions, but not by saliva, sweat, urine, other nonbloody fluids, or feces. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is diagnosed when severe immunodeficiency develops in a person with HIV infection as demonstrated by a CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/µL or the development of one or more of 25 specific AIDS-associated diseases, including opportunistic infections and malignancies.2 In the absence of HIV treatment, the time from initial HIV infection to the development of severe immunodeficiency and AIDS is approximately 10 years.3 Effective antiretroviral therapy has changed the natural history of the disease, prevents HIV disease progression, and prolongs survival.

The first cases of AIDS were described in 1981 in five young gay men in Los Angeles.4 Since the beginning of the HIV pandemic, an estimated 70 million people worldwide have acquired HIV infection and more than half of them died.1 Currently, an estimated 34 million people are living with HIV infection, with more than two thirds of them living in sub-Saharan Africa. An estimated 1.2 million people are currently living with HIV infection in the United States.5 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends routine HIV testing for all persons aged 13 to 64 years, not based on risk.6

Acute HIV infection can present as a nonspecific illness characterized by fever, oral ulcers, and maculopapular rash7; however, at least 50% of newly infected persons may be completely asymptomatic. The clinical illness will subside over several weeks and then the patient enters an asymptomatic phase, often with nonspecific generalized lymphadenopathy, that may last years as the CD4 lymphocyte count gradually declines over time. HIV-associated diseases that occur at higher CD4 counts (>300 cells/µL) include those caused by more aggressive pathogens (e.g., tuberculosis, herpes zoster, and pneumococcal pneumonia), as well as Kaposi sarcoma (KS). As the CD4 cell count declines below 300, other HIV-associated illnesses also occur, including oral hairy leukoplakia, oral thrush, and seborrheic dermatitis. When the CD4 cell count declines below 200, the case definition of AIDS is met, and AIDS-defining illnesses may also occur, including Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly P. carinii) pneumonia, central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis, and cryptococcal meningitis. Multiple opportunistic illnesses can occur simultaneously in a single patient.

With the development of effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV-associated malignancies have decreased markedly8; however, the risks remain high for both AIDS-defining and non–AIDS-defining cancers in comparison with the remainder of the population. AIDS-defining cancers include various aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), KS, and cervical cancer. The non-AIDS defining cancers include those disproportionately found in the setting of HIV such as Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), anal cancer, and hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV)-related liver cancer, as well as cancers that are increased because of associated habits such as a high smoking prevalence in people living with HIV.

A recent study9 detailed the cancer burden in the U.S. AIDS population, which quadrupled from 1991 to 2005 (from 96,179 to 413,080), largely because of an increase in the number of people aged 40 years or older. Nearly 80,000 cancers occurred during this time frame. When comparing 1991-1995 to 2001-2005, AIDS-defining cancers decreased by more than a factor of three (34,587 to 10,325 cancers; P (trend) < .001), whereas non–AIDS-defining cancers increased by about a factor of three (3193 to 10,059 cancers; P (trend) < .001). From 1991-1995 to 2001-2005, estimated counts increased for anal cancer (206 to 1564 cases), liver cancer (116 to 583 cases), prostate cancer (87 to 759 cases), lung cancer (875 to 1882 cases), and HL (426 to 897 cases).

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the average life expectancy of a patient with AIDS was less than 1 year. Today, it is estimated that a person diagnosed with HIV infection and appropriately managed with antiretroviral treatment will live close to the average life expectancy of the general population.10 This outcome is attributable to the 27 unique drugs for the treatment of HIV infection approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which typically are used in combination regimens of three or more drugs. This life expectancy makes treatment of the various malignancies more of an imperative than in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era. In addition, the aging HIV-infected population will experience cancers commensurate with the aging process. Cancer is now the leading cause of death for HIV-1–infected persons treated with HAART. A malignancy will develop in 25% to 40% of HIV-positive patients.11–20 Recently, studies of HAART interruption have shown a sixfold increase in both AIDS-related and non-AIDS-related cancers and an increased risk of cancer-associated death.21

AIDS-Related Lymphoma

Epidemiology

NHL and HL occur with increased frequency in patients infected with HIV.9 NHL will develop in approximately 10% of HIV-positive people, and although the incidence has greatly reduced during treatment with HAART, it is still increased 25-fold to 150-fold compared with the general population.22–25 These recent studies also demonstrate that the duration and depth of the CD4 nadir and the duration of viremia increase the incidence of NHL. NHL remains the AIDS-defining condition in approximately 3% of HIV-infected persons.

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

As in the general population, lymphogenesis is a multistep process, with a panoply of acquired gene mutations contributing to the malignant phenotype. Each subtype of lymphoma has its own set of acquired genetic mutations that can also vary within a subtype. Particular to HIV, decreased immune surveillance, B-cell dysregulation,26 and, in certain subtypes, the oncogenic viruses HHV-8 and EBV are involved in the pathophysiology of the disorder.27 For example, CNS lymphomas are virtually always associated with EBV, whereas primary effusion lymphoma is associated with HHV-8 infection. AIDS-Burkitt lymphoma is variably associated with EBV but also contains activating mutations in the c-myc proto-oncogene, frequent inactivation of p53, and point mutations in BCL6. One study showed that loss of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells in subjects progressing to EBV-related NHL correlated with loss of CD4+ T cells and that these cells were better preserved in equally immunocompromised patients in whom lymphoma did not develop.28 Early studies suggest that HIV-associated NHL will have a unique set of mutations,29 but research in this area is ongoing. Inherited factors may also play a role. One study demonstrated that lymphoma is less likely to develop in HIV-infected patients who are heterozygous for the CCR5-D32 deletion, whereas lymphoma is more likely to develop in persons with stromal cell–derived factor-1 mutations.30

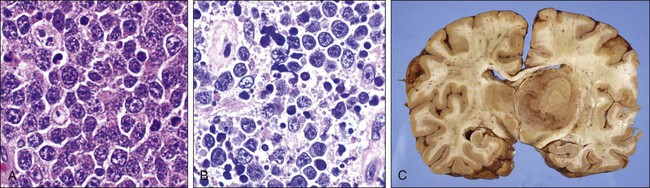

Three types of lymphoma are now recognized as AIDS defining by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Burkitt lymphoma; immunoblastic lymphoma, which is a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; and primary CNS lymphoma. Primary effusion lymphomas are also highly associated with HIV. The World Health Organization more recently provided a classification system for the HIV-associated lymphomas (Box 65-1 and Figure 65-1). The frequency of NHL increases with the degree of immunosuppression, particularly for CNS lymphoma, which is only seen when the CD4 count is less than 50/µL. T-cell and other lymphomas are rare.

Clinical Manifestations and Patient Evaluation

Patients with HIV-NHL frequently present with advanced stage III or IV disease. The majority will present with a rapidly growing mass or the development of systemic B symptoms (e.g., fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss). The clinical presentation is dependent on the site of involvement. Extranodal involvement including the bone marrow (25% to 40%), gastrointestinal tract (26%), and CNS (17% to 32%) is common. Leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry may be present alone at a higher frequency than in the immunocompetent population.31 Involvement of the small bowel and rectum is also prevalent, particularly in persons with large cell histology. Several prognostic factors affect survival, including CD4 count, Karnofsky performance, age, and lactate dehydrogenase level predict response to therapy.32

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

A randomized phase 3 study of CHOP with or without rituximab failed to demonstrate any added benefit of rituximab and suggested increased toxicity in persons with a CD4 count less than 50.33 In contrast, in another study, the addition of rituximab to CHOP produced a complete response rate of 77% and a 2-year survival rate of 75% in patients with AIDS-related NHL, with no increase in the risk of life-threatening infections.34 The current standard of care is to use rituximab with attention to infection, including hematopoietic growth factors and antibiotic prophylaxis in persons at highest risk.

Treatment with etoposide, prednisone, Oncovin (vincristine), cyclophosphamide, and hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin) (EPOCH) has produced responses of 79% in a preliminary study.35 Antiviral therapy was suspended during treatment in this protocol for fear of concurrent toxicities, leading to transient increases in viral load and decreases in CD4 counts. A multicenter trial by the AIDS Malignancy Consortium investigated EPOCH with concurrent versus sequential rituximab and found the complete response (CR) rate to be higher in the concurrent arm and similar to the National Cancer Institute pilot study.36 The vast majority of patients continued to undergo HAART during treatment, challenging the earlier assertion that HAART must be suspended.

Primary CNS Lymphoma

The response to therapy in patients with primary CNS lymphoma has been very disappointing. Palliation with steroids and whole-brain radiation (3000 to 5400 Gy) has response rates of 75%, and treatment with high-dose methotrexate has reportedly had similar results, but the response duration is short, with a median survival of 2 to 4 months regardless of CD4 count. A pilot study with only antiviral agents and immunomodulation was very promising, with two of five patients treated remaining in complete remission at 28 months and 52 months, respectively, but the study was closed early because of low accrual.37

Burkitt Lymphoma

Before HAART, treatments were too toxic and the prognosis was dismal. One small retrospective study40 and one small prospective study41 initially challenged the prevailing dogma, reporting intensive therapies such as cyclophosphamide, Oncovin (vincristine), doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, VePesid (etoposide), and Ara-C (cytarabine) (CODOX-M/IVAC) or hyper–cyclophosphamide, vincristine, Adriamycin (doxorubicin), and dexamethasone (CVAD). CVAD with methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine could be safely given with HAART with success rates of 80% to 90%. More recent publications have also suggested the same.42,43 Another retrospective study has supported the use of EPOCH-rituximab as more efficacious and less toxic.44 A recently completed clinical trial by the AIDS Malignancy Consortium was designed to reduce toxicity while maintaining efficacy and may confirm these results prospectively in a multicenter setting.45 The National Cancer Institute has also reported early results with EPOCH-rituximab in a prospective study, citing nearly 100% efficacy.46 A confirmatory multiinstitutional study is ongoing.

Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a very rare CD20-negative variant of HIV-associated NHL. It was originally described as almost exclusively associated with HIV and nearly always fatal in the pre-HAART era.47 The sine qua non of stage I disease is a mass in the jaw, but disseminated disease, including numerous bone lesions, is common. A retrospective study suggested curability in the HAART era in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients.48 Optimal management will be difficult to define because of the rarity of the disease.

The Controversial Timing of HAART

The optimal timing of HAART with combination chemotherapy is controversial.49 Many oncologists continue to administer antiretroviral drugs during chemotherapy, but some oncologists temporarily discontinue them, citing fears of drug-drug interactions and increased toxicities. However, early immune reconstitution could be important, and six randomized studies in persons with infections have shown a decrease in infection mortality when HAART is started immediately.50 A retrospective Italian study reported decreased infection but great neurotoxicity and anemia when CHOP was combined with HAART, but this early study was performed in the 1990s.51 The panoply of currently available HAART medications allows minimization of drug-drug interaction. It is unlikely that a controlled clinical trial will be conducted.

Hodgkin Lymphoma

As a population, patients infected with HIV have a ten- to twenty-fivefold increased risk of developing HL compared with the general population. Patients diagnosed with HIV-associated HL present with many high-risk characteristics that distinguish it from non–HIV-related classic HL.52 The differences, described in the following sections, are seen in the epidemiology, patients’ advanced presentation, more aggressive histologies, immunohistochemistry, and poorer overall outcome.52

Epidemiology

Multiple large database studies of linked cancer and HIV/AIDS registries from 1992-2005 in the United States showed that HIV-associated classic HL represents the second to third most common non-AIDS defining cancer.9,53 In 2001 the World Health Organization categorized it as an HIV-associated lymphoma.54,55 However, unlike HIV-associated NHL, the risk for developing HIV-associated classic HL was 68% higher in 1996-2002, the post-HAART era (standardized incidence ratio [SIR] 13.6), than in 1990-1995 (SIR 8.1)56 and is increasing with time despite stable rates of HL in the general population.57 Patients who have HL and HIV are more commonly male (85% vs. 54% in the general population), and in contrast to HIV-associated KS and NHL, HIV-associated HL develops mostly in patients with higher CD4 counts (>200 cells/µL).52,58

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

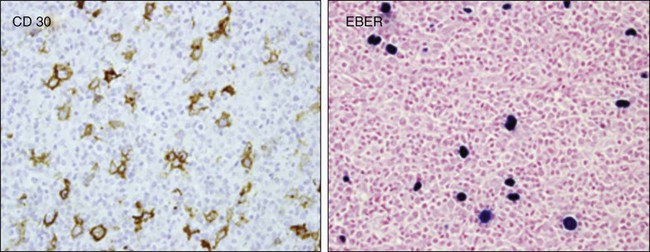

The transformed cell that defines classic Hodgkin lymphoma is the Reed-Sternberg cell, a large multinuclear cell that expresses surface antigens CD15 and CD30 without B- or T-cell surface antigens55 and originates from germinal B cell lymphocytes, as demonstrated by the expression of PAX 5, B-cell specific activator protein, and B-cell clonality based on single-cell polymerase chain reaction of the IgH gene.59–63 However, in persons with HIV, the Reed-Sternberg cell has been linked to postgerminal lymphocytes.64 It is interesting to note that diffuse large B-cell lymphoma derived from a nongerminal center has a worse prognosis than germinal cell–derived large cell lymphoma in most studies.

Reed-Sternberg cells are surrounded by B cells and CD4 cells, eosinophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts, all of which affect its survival and disease course.65,66 This trophic effect, which is attributed in part to CD4 cells, may explain the increase in incidence of HIV-related classic HL in the post-HAART era.58,62,63 The tumor microenvironment may also explain why patients with HIV-associated HL present with higher CD4 counts compared with other HIV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders, with the exception of Burkitt lymphoma.58,62,63 Mixed cellularity and lymphocytic depletion predominate in HIV-associated classic HL compared with the non-HIV population (discussed later).66 In addition, histologically, the Reed-Sternberg cell is found in much higher concentrations in HIV-associated classic HL than in non–HIV-associated classic HL.52 HIV-associated classic HL is associated in 80% to 100% of cases with EBV co-infection of the Reed-Sternberg cell, compared with 30% to 40% in patients with non–HIV-associated classic HL52,67,68 (see Figure 65-2).

Pathology

The pathology of HIV-associated classic HL changes as the immunosuppression progresses.58 In patients with CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/µL, the incidence of mixed cellularity (MC) classic HL is slightly higher than nodal sclerosing classic HL.58 At CD4 counts below 100 cells/µL, the incidence of HIV-associated classic HL decreases as a whole, but the incidence of nodal sclerosing classic HL decreases much more dramatically, falling almost to 0, compared with MC HIV-associated classic HL, explaining the increase of MC histology compared with all other histologic subtypes.58

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

As defined by the international prognostic score for advanced HL for non–HIV-associated HL, the following factors predict poorer outcome: >45 years of age, male gender, stage IV disease, a low albumin level, anemia, lymphopenia, and leukocytosis.69 In a single-institution retrospective study, half of the 51% of the patients who were seen with advanced disease had an international prognostic score of more than 5.70 Depending on the study, patients with HIV-associated HL are seen with advanced disease in 50% to 80% of cases.

Therapy

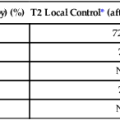

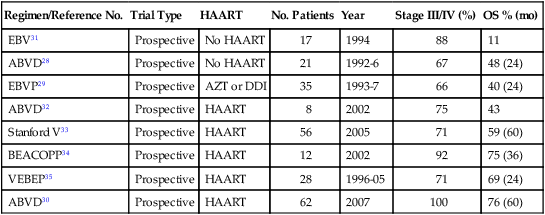

Currently, no standard of care exists for the upfront treatment of HIV-associated classic HL. Outcomes of prospective clinical trials for HIV-associated classic HL in the pre- and post-HAART era are summarized in Table 65-1. In the pre-HAART era, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group performed a prospective trial using Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) with supportive granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF).71 CR was attained in only nine patients (43%) and a partial remission was attained in 4 subjects (19%), resulting in a 2-year overall survival (OS) rate of 48%.71 Even with routine G-CSF use, severe neutropenia developed in 10 patients and opportunistic infections occurred in 6 patients (29%) during the study. A similar study with epirubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and prednisone (EBVP) in which only azidothymidine or dideoxyinosine was used as HIV therapy showed an equivalent 2-year OS of 40%.72

Table 65-1

Summary of Prospective Trials of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma in the Pre- and Post-Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era

| Regimen/Reference No. | Trial Type | HAART | No. Patients | Year | Stage III/IV (%) | OS % (mo) |

| EBV31 | Prospective | No HAART | 17 | 1994 | 88 | 11 |

| ABVD28 | Prospective | No HAART | 21 | 1992-6 | 67 | 48 (24) |

| EBVP29 | Prospective | AZT or DDI | 35 | 1993-7 | 66 | 40 (24) |

| ABVD32 | Prospective | HAART | 8 | 2002 | 75 | 43 |

| Stanford V33 | Prospective | HAART | 56 | 2005 | 71 | 59 (60) |

| BEACOPP34 | Prospective | HAART | 12 | 2002 | 92 | 75 (36) |

| VEBEP35 | Prospective | HAART | 28 | 1996-05 | 71 | 69 (24) |

| ABVD30 | Prospective | HAART | 62 | 2007 | 100 | 76 (60) |

Retrospective data show a positive effect of HAART on OS, disease-free survival, and infectious complications. The OS improved from 48% at 2 years to 76% at 5 years when comparing HIV-associated classic HL studies with ABVD with and without HAART.71,73 In the post-HAART era, only five prospective studies have been completed.72–75 A study of therapy with the ABVD regimen in patients with advanced stage HIV-associated HL assessed the outcome in 62 patients (1996-2005).73 The 5-year event-free survival probability was 71%, and OS was 76%.73 The vinorelbine, epirubicin, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, prednisone (VEBEP), Stanford V, and bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin (doxorubicin), cyclophosphamide, Oncovin (vincristine), procarbazine, prednisone (BEACOPP) studies included all stages, and despite the inclusion of earlier stages, the OS did not compare well with ABVD (see Table 65-1).77–77 The BEACOPP regimen did show improved CR rates compared with ABVD (100% vs. 87%), but 3 of the 12 patients studied died while undergoing chemotherapy (25%). Thus based on OS, adverse events, and progression-free survival, ABVD currently is the most commonly used regimen for advanced stage HIV-associated classic HL, although the OS is still about 15% lower than in the non-HIV population.71–79

Galamini et al.80 showed that a fluorodeoxyglucose–positron electron tomography scan performed at the completion of cycle 2 was prognostic for advanced HL in patients without HIV, although this finding has not been clearly demonstrated in the HIV population and is currently being evaluated in prospective clinical trials.81 The choice of concurrent antiretroviral therapy is important because protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors are potent inhibitors or inducers of the cytochrome p450 system.82 Ritonavir accelerates vinblastine-associated neuropathy, requiring either vinblastine dose reduction or a change to a nonritonavir-based regimen.83,84

Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

The outcomes for patients with HIV-associated classic HL are inferior to those of HIV-negative patients, likely because the outcomes are affected by Reed-Sternberg cell origin, EBV co-infection status, presentation, and histology. In an attempt to move the OS of persons with HIV-associated HL closer to that of the non-HIV population, clinical trial by the Aids Malignancy Consortium are currently under development to investigate the role of brentuximab (Vedotin), an anti-CD30 drug antibody conjugate, in conjunction with Adriamycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine, which has showed promise in the relapsed/refractory HL setting. See Table 65-1 for a summary of prospective trials.

Transplantation for HL and NHL

Myeloablative autologous transplants have been performed in patients with both NHL and HL in the setting of relapsed and refractory disease in small pilot studies.87–87 The Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS & Tumors (GICAT) reported the largest study and the only one enrolling patients before second-line therapy, with 27 of 50 going on to autologous transplant with a median overall survival of 33 months in all 50 eligible patients.88 In addition, two retrospective case control studies have suggested no difference between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients undergoing autologous transplant for the same indications.89,90 The AIDS Malignancy Consortium and Bone Marrow Clinical Trials Network have partnered in an ongoing trial to demonstrate multicenter feasibility and study biological correlates. Finally, gene therapy pilot studies are ongoing to test the feasibility of engineered hematopoietic stem cell HIV resistance at the time of transplant for malignancy.91

Nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation has been used in patients with refractory disease; it has produced short-term remissions (12 months) and was associated with little toxicity and few opportunistic infections.92 A case has been reported of simultaneous treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia and eradication of HIV infection using a donor with homozygous CCR5 deletion, a receptor necessary for HIV infection. However, the rarity of this deletion makes this approach unique. The AIDS Malignancy Consortium and Bone Marrow Clinical Trials Network have recently opened an allogeneic transplant pilot study for HIV-infected patients with a wide variety of hematologic malignancies.

Cervical Cancer and HIV

Epidemiology

Cancer of the cervix uteri is the second most common cancer among women worldwide. However, about 86% of the cases occur in developing countries. Whereas in developed countries it is the tenth most common type of cancer in women (9.0 per 100,000 women), in developing countries it is the second most common type of cancer (17.8 per 100,000) and cause of cancer deaths (9.8 per 100,000) among women. On the continent of Africa and in Central America, cervical cancer is the number one cause of cancer-related mortality among women.93

The HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study reported that cervical cancers in patients with AIDS has increased with time (1980-1989: 0.11% [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.09%-0.13%]; 2001-2007: 0.71% [95% CI, 0.51%-0.91%]; P < .001).94 The estimated risk may be 1.5 to 8 times that of the general population.95. In Uganda and South Africa, the relative risk of cervical cancer in HIV-positive women is about twice that of the general population.96 In the absence of cervical cancer screening programs, the majority of these cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

HPVs are a large family of small double-stranded DNA viruses that infect squamous epithelia. HPV infection is the major cause of cervical cancer. Genital HPV infections in women are very common, are sexually transmitted as a result of microabrasion in the genital epithelium, and have a peak prevalence between ages 18 and 30 years. Most of these infections clear spontaneously, but in 10% of immunocompetent women, these infections remain persistent and may progress to grade 2/3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasm and eventually to invasive cancer of the cervix. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasms are genetically unstable lesions associated with a spectrum of cytological atypia, ranging from low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 1 to high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 3. The latter are usually caused by high-risk HPVs, especially HPV 16 and 18. The oncogenic properties of high-risk HPV reside in the E6 and E7 genes, which, if inappropriately expressed in dividing cells, deregulate cell division and differentiation.97 The molecular, immunologic, and genetic factors associated with persistence and progression of HPV infections to cervical intraepithelial neoplasm and cancer have not been fully identified.

HIV-positive women are much more likely to have persistent HPV infections. The rate of cervical HPV infection in HIV-infected women with normal cervical cytology is more than 55% in South and Central America and Africa. In addition, HIV-infected women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 2+ are more likely to be infected with multiple HPV types compared with women with HIV in general (41.4% vs. 6.7%). When comparing HPV clearance rates, HIV-positive women with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/µL had a 71% lower chance of clearance of HPV infection compared with the women who had CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/µL. However, independent of CD4 count, HPV was more likely to persist in HIV-infected patients compared with immunocompetent women.98

HPV 16 and 18 account for approximately 70% of the cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix worldwide, but sparse data exist on HPV types identified in squamous cell carcinoma of HIV-positive women. A study from Kenya and South Africa found that although HIV-positive women were more likely to have multiple HPV types identified in cervical cancer, the HPV 16 and/or 18 prevalence combined was similar in HIV-positive (66.7%) and HIV-negative cases (69.1%) (PR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.2).99

Prevention and Early Detection

Studies evaluating the best method of cervical surveillance in HIV-infected women compared colposcopy, cervical cytology, and HPV testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 2+ or higher. Cervical cytology and colposcopy had similar rates of diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity of 98%-100%, specificity of 63%-65%, and positive predictive value of 22%-23%). HPV testing had similar sensitivity (91%) but significantly poorer specificity (48%).98

The prophylactic HPV L1 viruslike particle vaccines are highly efficacious and safe in the immunocompetent population, preventing >98% of HPV 16/18–related high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 2/3) in phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Because the current HPV vaccines include only 2 of the 15 oncogenic HPVs, they will not eliminate cervical cancer or the other HPV-associated anogenital diseases but could reduce, for example, the incidence of cervical cancer by as much as 70% if effectively delivered to female adolescents.100 HPV vaccine studies in HIV-infected women are ongoing.

In the general populations, the majority (69%) of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (associated with HPV 16 [59%] and HPV 18 [13%]), and 25% are adenocarcinomas (HPV 16 [36%] and HPV 18 [37%]). Data are limited on the histologic distribution of cervical cancers in HIV-positive populations. A retrospective study in South Africa found a similar distribution of squamous cell carcinomas (>90%) among the HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.101

The standard of care for the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer is concurrent chemoradiotherapy using cisplatin as the chemotherapeutic radiosensitizing agent. This regimen is the current standard of care based on multiple randomized, controlled trials showing improved efficacy when cisplatin was added to radiation therapy, even in high-risk patients who have histologic evidence of metastatic disease to pelvic and/or paraaortic lymph nodes. Data are very limited on the standard treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer in HIV-positive women. A retrospective study from South Africa comparing the treatment and prognoses of women treated for cervical cancer stratified by HIV status showed that 49 HIV-positive patients (88.1%) but only 213 HIV-negative patients (65.7%) presented with stage IIIB disease (P = .009). Forty-seven HIV-positive patients (79.7%) and 291 HIV-negative patients (89.8%) completed the equivalent dose of 68-Gy external-beam radiation and high-dose brachytherapy (P = .03). Of the 333 patients who underwent concurrent chemotherapy, 26 HIV-positive patients (53.1%) and 212 HIV-negative patients (74.6%) completed four weekly cycles of platinum-based treatment. In models that included age, disease stage, HIV status, and treatment, a poor response at 6 weeks was associated only with stage IIIB disease (odds ratio [OR], 2.39; 95% CI, 1.45-3.96) and with patients receiving an equivalent radiation dose in 2-Gy fractions of <68 Gy (OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.24-7.94).101

Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

Although cervical cancer treatments have been improving in recent years, undeniably, prevention has the largest impact on minimizing the burden of HIV-associated cervical cancer. Prophylactic vaccination against HPV will likely have clear clinical benefits in HIV-infected women, especially if the vaccine is administered before sexual contact. However, clinical trials of vaccination in persons with HIV are ongoing, and the efficacy and duration of immunity are unknown. In addition, only cancers attributed to HPV types 16 and 18 will be prevented. Algorithms for screening in HIV-uninfected women might not apply to HIV-positive women, because the course of disease from persistence to cancer appears to be different in the setting of HIV, particularly in persons with a poor immune status. Also, treatments for cervical precancerous lesions in persons with HIV should focus on cancer control rather than cure, because clearance of HPV in the setting of HIV is unlikely. Because cervical cancer trials are conducted in developed countries and typically exclude the enrollment of HIV-positive women, minimal data exist particular to cervical cancer treatment in the setting of HIV. The burden of disease of HIV-associated cervical cancer in developing countries is likely large but only estimated at present. A pressing need exists to directly address the drug-drug interactions of ART on standard and targeted cervical cancer treatments through pharmacokinetic trials, as well as to find ways to minimize dose delays and modifications due to marrow toxicities of both chemotherapy and pelvic radiation in the setting of HIV. Lastly, nodal control and extrapelvic recurrences are often more common in the setting of HIV and require further study.95

Anal Cancer and HIV

Incidence of Anal Cancer

Although the incidence of anal cancer is relatively low compared with other HPV-associated cancers such as cervical cancer, the incidence of this disease has been increasing among both men and women by about 2% per year.102 From 2003-2007, the incidence of anal cancer was 1.8/100,000 in women and 1.4/100,000 in men.103 Before the HIV epidemic, the known risk factors for anal cancer included smoking, history of homosexual contact, history of genital warts and other sexually transmitted infections,104 and chronic irritation in the form of hemorrhoids, fissures, and fistulas.105 Men who have sex with men are among those at highest risk for anal cancer, with an estimated incidence as high as 36.9/100,000106 before the onset of the HIV epidemic. Finally, a risk factor for anal cancer of increasing importance is immunosuppression. Solid organ transplant recipients, including renal transplants and heart and lung transplants, are at increased risk of anal cancer.109–109

Persons with HIV-associated immunosuppression are at especially high risk of anal cancer. This high risk was true before the availability of HAART,110 and the incidence of anal cancer has not declined since HAART became widely available; in fact, it may actually be increasing in some HAART-treated populations111–115 to as high as 128/100,000.116 Given that most HIV-positive persons currently do not undergo screening or treatment for high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia, the longer survival time afforded by HAART may give a high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia lesion more time to progress to cancer.

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

Anal cancer is very similar biologically to cervical cancer. As with cervical cancer, most anal cancers (approximately 90%) are associated with HPV.117 Similarly, HPV 16 is the most common type and is more dominant than in cervical cancer. Most anal cancers are classified histologically as squamous cell cancer, with a smaller proportion classified as adenocarcinoma and small cell/neuroendocrine.103

Prevention of Anal Cancer

Anal cancer can potentially be prevented through primary prevention or secondary prevention approaches. Primary prevention consists of vaccination to prevent initial infection with HPV, the causative agent of anal cancer. The quadrivalent vaccine was initially approved in women to prevent cervical and vulvovaginal HPV infection with the vaccine types (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) and their associated precancerous lesions. More recently the quadrivalent vaccine was shown to be effective in males in prevention of anal HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia attributed to these types.118 The quadrivalent vaccine is approved for routine use in males aged 9 to 21 years (up to 26 years if HIV-positive or otherwise immunocompromised) and in females aged 9 to 26 years for prevention of anal HPV infection with the vaccine types, and anal intraepithelial neoplasia and anal cancer attributed to these types. Because the majority of, but not all, anal cancers are due to HPV 16 or 18, if vaccination is universally adopted, it may prevent most, but not all, anal cancers in the future.

Secondary prevention is modeled after cervical cancer prevention programs. Anal cytology is used to screen at-risk groups, followed by referral of persons with abnormal anal cytology results for high-resolution anoscopy and biopsy.119 At-risk groups include, but are not limited to, all HIV-infected men and women, HIV-negative men who have sex with men, those with immunosuppression due to causes other than HIV, women with a history of cervical or vulvar cancer, and persons with perianal HPV-related lesions. The goal of high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) is to identify high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia and remove it before progression to anal cancer. These procedures are not yet considered standard of care because a reduction in the incidence of anal cancer has not yet been proven. Based on the strength of the data showing that this approach in the cervix is effective to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer and the high and/or rising incidence of anal cancer in at-risk groups, a growing number of clinicians are screening for and treating high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia while awaiting the data from such a study.

Treatment of High-Grade Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Anal Cancer

Treatment of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia is an active area of investigation and currently includes infrared coagulation, topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), electrocautery, and imiquimod.119 Treatment of invasive anal squamous cell carcinomas has changed considerably since the 1970s when first-line therapy included radical excision. Currently, first-line therapy consists of a combination of chemotherapy (typically 5-FU and mitomycin C) and radiotherapy. Many clinicians now use cis-platinum in place of mitomycin C,120 although one randomized controlled trial failed to show a survival advantage for cis-platinum.121 The AIDS Malignancy Consortium and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) have reported safety and early efficacy with cetuximab plus cisplatin, 5-FU, and radiation in immunocompetent (ECOG 3205) and HIV-positive (AMC045) patients.122 Abdominoperineal resection is reserved for patients who cannot tolerate radiation and chemotherapy or for salvage therapy among persons for whom first-line therapy fails.

Early in the HIV epidemic, HIV-positive patients often were unable to tolerate full-dose therapy because of toxicity, but with improvements in HIV therapy, some studies show that HIV-positive patients tolerate full-dose therapy with good outcomes.123,124 Other studies continue to show a worse outcome among HIV-positive patients compared with HIV-negative patients.125 Five-year survival rates for anal cancer in the general population ranges from 71% for stage I cancer to 21% for stage IV cancer.126

Kaposi Sarcoma

Epidemiology

AIDS-associated KS is the most common malignancy in people infected with HIV. KS-associated herpesvirus is endemic in Africa and much of the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe. Elsewhere, associated herpesvirus infection is common in men who have sex with men, although the risk has decreased threefold with the introduction of HAART. For example, in a combined analysis of 47,936 HIV-positive persons from North America, Europe, and Australia, KS age-adjusted incidence rates decreased from 15.2 to 4.9 cases per 1000 person-years between the periods 1992-1996 and 1997-1999.127

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

KS is a low-grade vascular tumor associated with HHV-8, also known as KS-associated herpesvirus. Latent infection with KS-associated herpesvirus transforms spindle and endothelial cells, which form KS lesions.128 KS growth is promoted by the latency-associated nuclear antigen, which inhibits p53.129 Several cytokines also play a role, including interleukins-1 and -6, vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, basic-fibroblast growth factor, and stem cell factor.130–134

Clinical Manifestations/Patient Evaluation/Staging

Unlike most solid tumors that are staged using the TNM system, KS staging depends on the extent of tumor (T), immune status (I), and severity of systemic illness (S).135 This system, developed by the AIDS Clinical Trial Group of the National Institutes of Health, underscores the importance of systemic immune function in disease severity and prognosis.

Treatment

Treatment is based on the extent of disease. HAART is indicated as the first treatment in patients with HIV and KS (regardless of CD4 count) who are not already being treated with HAART.136 Immune reconstitution can often lead to regression of KS lesions without additional therapy, although flares of KS can also occur.137 If the disease presentation is mild or indolent and HAART has just been started or modified, observation for several months may be appropriate.

For KS that does not regress with HAART alone, treatment is guided by the extent of disease. For skin lesions that are limited in extent and number, local therapy such as radiation, cryotherapy, intralesional vinblastine, or topical alitretinoin gel are reasonable options.138,139

For extensive cutaneous disease, rapidly progressive disease, or visceral involvement, systemic chemotherapy is appropriate. First-line treatment with liposomal doxorubicin is associated with high response rates and excellent tolerability. Liposomal doxorubicin is superior to combination therapy with doxorubicin, vincristine, and bleomycin.140

The liposomal formulation of doxorubicin is superior to the unencapsulated form as directly compared in a randomized clinical trial. The drug accumulates in tumor, skin, soft tissue, and extremities. Thus if liposomal doxorubicin is unavailable, standard doxorubicin is not considered an acceptable substitute. Liposomal daunorubicin, however, is an acceptable substitute and is associated with comparable efficacy.141

For patients who are intolerant or refractory to liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel is the preferred second-line agent. It is administered at 100 mg/m2 every 2 weeks.142,143 These doses are generally not highly myelosuppressive, but G-CSF can be used if needed. Response rates of 70% have been reported, with common toxicities, including alopecia and neuropathy. For KS that progresses despite treatment with liposomal doxorubicin and paclitaxel, vinorelbine or gemcitabine are reasonable options.144,145

It is common practice in oncology to administer systemic glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone to prevent infusion reactions related to liposomal drugs and taxanes. However, corticosteroids can worsen immune suppression and thus aggravate KS.146 For this reason the minimal dose necessary to prevent a reaction should be used, and in some patients steroids may be safely omitted.

Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

Several other agents have activity in persons with advanced KS, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.147 The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor sirolimus has also shown significant activity in persons with KS, but its use is complicated by pharmacologic interactions with many HAART agents.148 Further research on mTOR inhibitors in persons with KS is warranted. A safe and effective oral treatment for advanced KS would represent a major advance, especially in resource-limited settings such sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of the world’s burden of HIV-KS occurs, and where access to effective intravenous chemotherapy is limited.149

Hepatocellular Carcinoma and HIV

Epidemiology

HBV accounts for as much as half of all cases of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Worldwide,150 400 million people are infected with HBV,1 predominantly in Asia and Africa, where as many as 70% of adults show serologic evidence of current or prior infection, and 8% to 15% have chronic HBV infection.150 Much of the infection occurs perinatally. Approximately 10% of the HIV-infected population has concurrent chronic hepatitis B,2 with co-infection more common in areas of high prevalence for both viruses. In countries where the viruses are highly endemic, the rate can be as high as 25%.151 Co-infection with HIV increases hepatitis B viremia, progression to chronic hepatitis B fivefold, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.150

Overall, HIV infection increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma sevenfold,152 in part because of co-infection with HCV and HBV.