Abnormal Presentation and Multiple Gestation

Joy L. Hawkins MD, BettyLou Koffel MD

Chapter Outline

The labor and delivery of a parturient with a multiple gestation and/or fetal breech presentation represents a major challenge for the obstetrician and the anesthesia provider. Anesthetic requirements may change from moment to moment, and an obstetric emergency may necessitate immediate intervention. All members of the perinatal care team must communicate directly and clearly with each other as well as with the parturient and her family to ensure the best possible outcome for both the mother and the neonate(s).

The presentation denotes that portion of the fetus that overlies the pelvic inlet. In most cases, the fetal presenting part can be palpated through the cervix during a vaginal examination. The presentation may be cephalic, breech, or shoulder. Breech and shoulder presentations occur with increased frequency in patients with multiple gestation. Cephalic presentations are further subdivided into vertex, brow, and face presentations according to the degree of flexion of the neck. With an asynclitic presentation, the fetal head is tilted toward one shoulder and the opposite parietal eminence enters the pelvic inlet first.

The lie refers to the alignment of the fetal spine with the maternal spine. The fetal lie can be either longitudinal or transverse. A fetus with a vertex or breech presentation has a longitudinal lie. A persistent oblique or transverse lie typically requires cesarean delivery.

The position of the fetus denotes the relationship of a specific fetal bony point to the maternal pelvis. The position of the occiput defines the position for vertex presentations. Other markers for position are the sacrum for breech presentations, the mentum for face presentations, and the acromion for shoulder presentations. The attitude of the fetus describes the relationship of the fetal parts with one another; the term is typically used to refer to the position of the head with regard to the trunk, as in flexed, military, or hyperextended.

Abnormal Position

During normal labor, the fetal occiput rotates from a transverse or oblique position to a direct occiput anterior position. In a minority of patients with an oblique posterior position, the occiput rotates directly posteriorly and results in a persistent occiput posterior position. The occiput posterior position may lead to a prolonged labor that is associated with increased maternal discomfort. Less often, the vertex remains in the occiput transverse position; this condition is known as deep transverse arrest.

In the past, obstetricians performed manual or forceps rotation to hasten delivery and lessen perineal trauma in women with an abnormal position of the vertex. Today, many obstetricians are reluctant to perform rotational forceps delivery for fear of causing excessive maternal and/or fetal trauma. In cases of persistent occiput posterior position, the contemporary obstetrician is more likely to allow the head to remain in the occiput posterior position at vaginal delivery. Only 29% of nulliparous women and 55% of parous women with a persistent occiput posterior position will achieve spontaneous vaginal delivery.1 Some cases of persistent occiput posterior position, and many cases of deep transverse arrest, require cesarean delivery because of dystocia.

During administration of epidural analgesia to a patient with an abnormal position, the addition of a lipid-soluble opioid to a dilute solution of local anesthetic is particularly useful. This combination provides analgesia while preserving pelvic muscle tone. Relaxation of the pelvic floor and perineum may prevent the spontaneous rotation of the vertex during labor.2 In contrast, profound pelvic floor relaxation is needed to facilitate instrumental vaginal delivery with forceps.

Breech Presentation

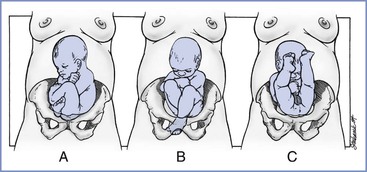

Breech presentation describes a longitudinal lie in which the fetal buttocks and/or lower extremities overlie the pelvic inlet. Figure 35-1 shows the three varieties of breech presentation:

• Frank breech—lower extremities flexed at the hips and extended at the knees

• Complete breech—lower extremities flexed at both the hips and the knees

• Incomplete breech—one or both of the lower extremities extended at the hips

FIGURE 35-1 Three possible breech presentations. A, The complete breech demonstrates flexion of the hips and flexion of the knees. B, The incomplete breech demonstrates intermediate deflexion of one or both hips and knees. C, The frank breech shows flexion of the hips and extension of both knees. (From Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:396.)

Ultrasonographic or radiographic examination typically allows the obstetrician to confirm the type of breech presentation and to exclude the presence of associated severe congenital anomalies (e.g., anencephaly). The type of breech presentation may influence the obstetrician’s decision regarding the mode of delivery. The fetus with a frank breech presentation tends to remain in that presentation throughout labor. In contrast, a complete breech presentation may change to an incomplete breech presentation at any time before or during labor.

Epidemiology

The breech presentation is the most common of the abnormal presentations. Both the incidence and the type of breech presentation vary with gestational age (Table 35-1). Before 28 weeks’ gestation, approximately 25% of fetuses are in a breech presentation.3 Most change to a vertex presentation by 34 weeks’ gestation, but 3% to 4% of fetuses remain in a breech presentation at term.3

TABLE 35-1

Types of Breech Presentation

| Type of Breech | Percentage of All Breech Presentations | Percentage of Preterm Gestation Breech Presentations |

| Frank | 48-73 | 38 |

| Complete | 5-12 | 12 |

| Incomplete | 12-38 | 50 |

Modified from Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012: 396.

Many factors predispose to breech presentation (Box 35-1).4 Abnormalities of the fetus or the maternal pelvis or uterus may play a role. Among patients with pelvic or uterine abnormalities, a breech presentation may allow more room for fetal growth and movement. Likewise, hydrocephalic fetuses are more likely to assume a breech presentation. Multiparity, multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, and anencephaly also predispose to breech presentation. These conditions may interfere with the normal process of accommodation between the fetal head and the uterine cavity and maternal pelvis. Other factors may also play a role. In a prospective cohort study, low free thyroid hormone (T4) levels at 12 weeks’ gestation were associated with breech presentation at term.5

Obstetric Complications

Obstetric complications are more likely with a breech presentation (Table 35-2). Cesarean delivery decreases the risk for some of these complications. Vaginal breech delivery entails a higher risk for neonatal trauma than delivery of an infant with a vertex presentation, but cesarean delivery does not eliminate the risk for trauma to the infant.6 Rather, cesarean delivery of a breech presentation can be difficult and traumatic, especially if the skin and uterine incisions are insufficient or maternal muscle relaxation is inadequate.

TABLE 35-2

Incidence of Complications Associated with Breech Presentation

| Complication | Incidence |

| Intrapartum fetal death | Increased 16-fold* |

| Intrapartum asphyxia | Increased 3.8-fold* |

| Umbilical cord prolapse | Increased 5- to 20-fold* |

| Birth trauma | Increased 13-fold* |

| Arrest of aftercoming head | 4.6%-8.8% |

| Spinal cord injuries with deflexion | 21% |

| Major congenital anomalies | 6%-18% |

| Preterm delivery | 16%-33% |

| Hyperextension of head | 5% |

* Compared with cephalic presentation.

Modified from Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:401.

The risk for umbilical cord prolapse varies with the type of breech presentation (Table 35-3). In the parturient with an incomplete breech presentation, the presenting part does not fill the cervix as well as the vertex or buttocks, allowing the umbilical cord to prolapse into the vagina before delivery. Umbilical cord prolapse typically necessitates emergency cesarean delivery.

TABLE 35-3

Risk for Umbilical Cord Prolapse

| Type of Breech | Risk for Cord Prolapse (%) |

| Frank | 0.5 |

| Complete | 4-6 |

| Incomplete | 15-18 |

Modified from Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:396.

Morbidity and Mortality

There is a higher risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality with a breech presentation, even when the risk is adjusted for preterm gestation. The factors that cause breech presentation are often more important than the presentation itself. For example, the severe congenital anomalies that predispose to breech presentation (e.g., hydrocephalus, anencephaly) significantly contribute to neonatal morbidity and mortality. Relative perinatal mortality rates (calculated from data for linked siblings from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway) confirm that breech presentation is a marker of perinatal risk, regardless of the mode of delivery.7 Both nonreassuring fetal heart rate (FHR) tracings and dystocia occur more commonly in patients with a term breech presentation, even those who have undergone successful external cephalic version.8

Vaginal breech delivery entails a higher risk for maternal morbidity (e.g., infection, perineal trauma, hemorrhage) than vertex delivery.4 However, among women with a fetal breech presentation, maternal outcomes are similar between women who had a planned cesarean delivery and those who had a trial of labor. At 2 years postpartum, maternal morbidity assessed by questionnaire (917 responses for a 79% return) was not different for urinary incontinence, breast-feeding, pain, depression, menstrual problems, fatigue, and distressing memories of the birth experience.9 In a single-center study of 846 singleton breech deliveries, Schiff et al.10 also did not find a higher risk for maternal morbidity in women who underwent cesarean delivery during labor than in women who underwent planned cesarean delivery.

Obstetric Management

External Cephalic Version

The process of external cephalic version converts a breech or shoulder presentation to a vertex presentation. The average success rate for this procedure is 58%, with a wide range reported in published studies.11,12 External cephalic version is most likely to be successful if (1) the presenting part has not entered the pelvis, (2) amniotic fluid volume is normal, (3) the fetal back is not positioned posteriorly, (4) the patient is not obese, (5) the patient is parous, and (6) the presentation is either frank breech or transverse.13 Early labor does not preclude successful external cephalic version, but external cephalic version is rarely successful when the cervix is fully dilated or when the membranes have ruptured. No scoring system has been developed that reliably predicts which candidates will have a successful version attempt, although the variables just listed can be used when obtaining informed consent.

The optimal timing of external cephalic version is after 36 or 37 weeks’ gestation, for the following reasons.11,14 First, if spontaneous version to a vertex presentation is going to occur, it will likely happen by 36 or 37 weeks’ gestation, and successful performance of external cephalic version after 37 weeks’ gestation decreases the likelihood of reversion from a vertex to a breech presentation. Second, if complications occur during external cephalic version performed after 37 weeks’ gestation, emergency delivery will not result in delivery of a preterm infant.

Successful external cephalic version helps reduce the risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with breech delivery. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)11 has suggested that “because the risk of an adverse event occurring as a result of external cephalic version is small and the cesarean delivery rate is significantly lower among women who have undergone successful version, all women near term with breech presentations should be offered a version attempt.” Labor and vaginal delivery occur in the majority of patients who have undergone successful external cephalic version, albeit with an increased risk for intrapartum cesarean delivery because of dystocia or a nonreassuring FHR tracing.15 A meta-analysis found that the intrapartum cesarean delivery rate was 27.6% after successful external cephalic version versus 12.5% in women with a spontaneous cephalic presentation.15

External cephalic version is associated with a low rate of morbidity in contemporary obstetric practice, although placental abruption and preterm labor have been reported.11 Safe external cephalic version requires FHR monitoring and access to cesarean delivery services. In a systematic review of 84 studies that involved 12,955 women, complications included transient (6.1%) and persistent (0.22%) FHR abnormalities, vaginal bleeding (0.30%), placental abruption (0.08%), emergency cesarean delivery (0.35%), and stillbirth (0.19%).12 Fetal-maternal hemorrhage is another potential complication of external cephalic version.12 In one study, 16 of 89 (18%) patients undergoing external cephalic version had Kleihauer-Betke stains that signaled the occurrence of fetal-maternal hemorrhage.16

Obstetricians usually administer a tocolytic agent (e.g., terbutaline) before performing external cephalic version. A randomized placebo-controlled trial found that the success rate of version was doubled when terbutaline was given rather than placebo.16 Several studies have shown a benefit to tocolysis only in nulliparous women.11 A randomized controlled trial of intravenous nitroglycerin for tocolysis (100- to 300-µg bolus doses, up to a maximum total dose of 1000 µg) found that the success rate was 24% in nulliparous women who received nitroglycerin versus 8% in the placebo group.17 The success rate was higher in parous women (43%), but it did not differ between the nitroglycerin and placebo groups.17 Interestingly, the rates of hypotension were similar between groups. A Cochrane Review18 found that tocolytic therapy for external cephalic version increases the number of women with a cephalic presentation at the onset of labor (relative risk [RR], 1.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 1.85) and reduces the number of cesarean deliveries (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.94).

Several studies have described the use of epidural or spinal analgesia or anesthesia for external cephalic version.19 Maternal discomfort may be significant during external cephalic version; greater pain during the procedure is associated with a lower chance of success.20 Some obstetricians argue that the absence of anesthesia limits the force that the obstetrician can apply during the procedure. They contend that administration of anesthesia may encourage the obstetrician to use excessive force, possibly increasing the risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality, but that concern is not supported by published evidence. In fact, spinal anesthesia reduces the force required for successful version.21

Weiniger et al.22 randomly assigned 70 nulliparous women to receive either spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine 7.5 mg or no anesthesia for external cephalic version. The success rate was 67% in those receiving spinal anesthesia, 32% in those without analgesia, and 42% in those who did not consent to enroll in the study. A randomized controlled trial in parous women using similar methodology also found an increased success rate with spinal anesthesia (87% versus 58%).23 In contrast, Sullivan et al.24 randomized 96 parturients to receive either intrathecal bupivacaine 2.5 mg with fentanyl 15 µg as part of a combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique or intravenous fentanyl 50 µg before attempted external cephalic version. There was no difference between groups in the rate of successful external cephalic version (47% with CSE analgesia and 31% with intravenous fentanyl) or vaginal delivery (36% versus 25%), although pain scores were lower and satisfaction scores were higher with CSE analgesia.

A meta-analysis of seven studies using neuraxial blockade to facilitate external cephalic version concluded that administration of an anesthetic dose of local anesthetic doubles the success rate of external cephalic version (RR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46 to 2.60), whereas an analgesic dose does not have any effect (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.49).25 A subsequent meta-analysis confirmed that neuraxial blockade increases the rate of successful version (60%) compared with no neuraxial block (38%); when the authors calculated the number needed to treat, they determined that five women must receive a neuraxial block to achieve one additional successful version.19 There was no difference between groups in the rate of cesarean delivery; however, this second meta-analysis failed to distinguish between neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia, and it included at least one trial that allowed both vaginal breech delivery and spinal anesthesia for a subsequent version attempt among control patients who had a failed version.19 Several investigators have reported successful outcomes with neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia in women in whom the first attempt at external cephalic version without neuraxial analgesia had been unsuccessful.22,26 These patients elected to undergo another version attempt with neuraxial analgesia. Weiniger et al.22 found that failure of external cephalic version was attributed to pain in 15 women in their control group. Eleven of those 15 (73%) women subsequently had successful external cephalic version with spinal analgesia. Cherayil et al.26 reported successful version in 13 of 15 (87%) repeat procedures performed with neuraxial blockade.

In our practices, we do not routinely provide spinal or epidural analgesia during external cephalic version. However, emerging evidence suggests that it may help facilitate successful version and vaginal delivery. If a neuraxial technique is used, administration of an anesthetic dose of local anesthetic appears to result in higher success rates than use of an analgesic dose.

Mode of Delivery

A substantial number of obstetricians recommend the routine performance of cesarean delivery in patients with a breech presentation. The publication of the Term Breech Trial in 2000 changed clinical practice around the world.6 In contemporary obstetric practice in the United States, most parturients with a breech presentation are delivered abdominally.

The Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group6 enrolled 2088 women from 26 countries with a singleton fetus in a frank or complete breech presentation. These women were randomly assigned to undergo planned cesarean delivery or planned vaginal delivery. Using an intent-to-treat analysis, the investigators noted that perinatal and neonatal mortality rates, and serious neonatal morbidity, were significantly lower in the planned cesarean delivery group (1.6% versus 5%). This difference was greatest in those countries with a low perinatal mortality rate (e.g., Canada, United Kingdom, United States).6 Secondary analysis of perinatal outcomes demonstrated that the lowest risk for adverse outcome occurred when a pre-labor cesarean delivery was performed at term gestation. The risk for adverse outcome progressively increased with cesarean delivery performed during early labor and active labor and was highest with a vaginal birth. Labor augmentation and a longer time between the start of pushing and delivery were associated with an increased risk for adverse perinatal outcome, whereas the presence of an experienced clinician at delivery was associated with a reduced risk for adverse perinatal outcome.27 Interestingly, in a 2-year follow-up study in some centers that participated in the Term Breech Trial there was no difference in the risk for death or neurodevelopmental delay between children delivered by planned cesarean and those delivered by planned vaginal delivery.28 The following two factors may have contributed to the lack of significant differences in outcome at 2 years of age: (1) the sample size may have been inadequate, and (2) measures of early neonatal morbidity have a low predictive value for long-term outcomes (i.e., most children with early neonatal morbidity survive and develop normally).28

In the Term Breech Trial,6 maternal morbidity and mortality did not differ between the two groups for the first 6 postpartum weeks. Women who underwent planned cesarean delivery were less likely to report urinary incontinence at 3 months29; however, there was no difference at 2 years.9 As assessed by questionnaire, maternal outcomes at 2 years after delivery were similar after planned abdominal delivery and after planned vaginal delivery for singleton breech infants born at term.9

As a result of the Term Breech Trial, the number of planned vaginal breech deliveries has decreased in many regions of the world. For example, in Denmark, the proportion of singleton term breech infants delivered vaginally decreased abruptly from 20% before 1999 to 6% after 2001.30 At the same time, intrapartum or early neonatal mortality among all term breech infants decreased from 0.13% to 0.05% (RR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.98).30 These kinds of trends are self-reinforcing. As the number of practitioners with experience in performing vaginal breech delivery has decreased, the number of vaginal breech deliveries available to teach obstetric residents may no longer be adequate.31 Results from an Australian survey suggest that “few of the next generation of …obstetricians plan to offer vaginal breech delivery to their patients.”32

Nevertheless, obstetricians in selected regions of the world retain a strong tradition of offering vaginal breech delivery for selected patients. Published in 2006, the PREsentation et MODe d ‘Accouchement (PREMODA; presentation and mode of delivery) study33 described birth outcomes for all term breech deliveries in 2001 through 2002 in 174 centers in France and Belgium. The study included 5579 women who planned cesarean breech delivery and 2526 women who planned vaginal breech delivery, of whom 1796 actually delivered vaginally.33 The primary outcome captured a composite of fetal and neonatal mortality and serious morbidity and was not different between women who planned to undergo vaginal delivery (1.60%; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.17) and women who planned to undergo cesarean delivery (1.45%; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.81), with an overall odds ratio of 1.10 (95% CI, 0.75 to 1.61).33 The authors suggested that rigorous adherence to protocols for patient selection, intrapartum fetal surveillance, and second-stage management contributed to improved outcomes for women attempting vaginal breech delivery.

In 2006, in recognition of results from the PREMODA study and other single-center descriptions of excellent outcomes for vaginal breech delivery, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) made the following recommendations about mode of singleton breech delivery at term31:

Although a planned trial of labor and vaginal breech delivery occurs uncommonly in most hospitals in North America and the United Kingdom, vaginal breech delivery still occurs because some patients present in advanced labor. Selection criteria such as those listed in Box 35-2 are used by advocates of a trial of labor and vaginal delivery.4 The availability of personnel experienced in obstetric anesthesia and neonatal resuscitation are prerequisites for a trial of labor. Hyperextension of the fetal head remains an absolute contraindication to a trial of labor in the patient with a breech presentation.4

Vaginal Breech Delivery

Several aspects of the conduct of breech labor differ from those for a vertex presentation. The cervix must be fully dilated before the patient begins to push. Indeed, some obstetricians delay maternal expulsive efforts until 30 minutes after the diagnosis of full cervical dilation. Others delay expulsive efforts until the breech is at the perineum.

There are three varieties of vaginal breech delivery. Spontaneous breech delivery is delivery without any traction or manipulation other than support of the infant’s body. With assisted breech delivery (also known as partial breech extraction), the infant is delivered spontaneously as far as the umbilicus; at that time, the obstetrician assists delivery of the chest and the aftercoming head. With total breech extraction, the obstetrician applies traction on the feet and ankles to deliver the entire body of the infant. Except for vaginal delivery of a second twin, obstetricians almost never perform total breech extraction. Total breech extraction increases the likelihood of difficult, traumatic delivery, including entrapment of the fetal head.

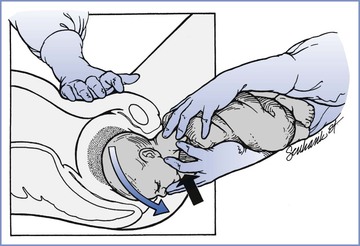

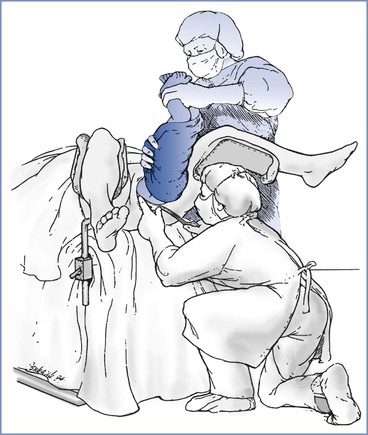

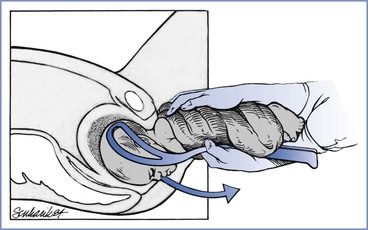

During assisted breech delivery or total breech extraction, the obstetrician attempts to maintain flexion of the cervical spine during delivery of the aftercoming head. This may be accomplished manually or by the application of Piper forceps (Figures 35-2 through 35-4). In most cases the obstetrician performs a generous episiotomy to prevent perineal obstruction of the aftercoming head.

FIGURE 35-2 Vaginal breech delivery. The black arrow indicates the direction of pressure from two fingers of the operator’s right hand on the fetal maxilla (not the mandible). This maneuver assists in maintaining appropriate flexion of the fetal vertex (direction of blue arrow), as does moderate suprapubic pressure from an assistant. Delivery of the head may be accomplished with continued maternal expulsive forces and gentle downward traction. (From Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:400.)

FIGURE 35-3 Vaginal breech delivery. Demonstration of incorrect assistance during the application of Piper forceps; the assistant hyperextends the fetal neck. Such positioning increases the risk for neurologic injury. (From Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:400.)

FIGURE 35-4 Vaginal breech delivery. Once the Piper forceps are applied, the fetal trunk is supported by one hand, and gentle traction on the forceps (arrow) in the direction of the pelvic axis results in a controlled delivery. (From Lanni SM, Seeds JW. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:401.)

Cesarean Delivery

Cesarean delivery does not guarantee an atraumatic delivery, especially if the skin and uterine incisions are inadequate. Before 32 weeks’ gestation, the lower uterine segment may be inadequate to allow an atraumatic delivery through a low transverse uterine incision. In such cases, the obstetrician should perform a low vertical uterine incision, which can be extended to facilitate an atraumatic delivery. Unfortunately, such incisions often extend to the body of the uterus, which does not heal as well as the lower uterine segment. It is unclear whether this situation increases the risk for uterine rupture during a trial of labor in a subsequent pregnancy (see Chapter 19).

Anesthetic Management

Benefits of neuraxial analgesia during labor include (1) pain relief, (2) inhibition of early pushing by blocking the perineal reflex, (3) ability of the parturient to push during the second stage and spontaneously deliver the infant to the level of the umbilicus, (4) a relaxed pelvic floor and perineum at delivery, and (5) the option to extend analgesia to surgical anesthesia for emergency cesarean delivery if needed.

Analgesia for Labor

Emergency cesarean delivery may be required at any time during a trial of labor. Epidural analgesia and CSE analgesia are excellent choices during a trial of labor in patients with a breech presentation. The anesthesia provider should tailor the analgesic technique to the needs of the individual patient. Patients with a breech presentation often have earlier complaints of rectal pressure than patients with a vertex presentation. It is important to provide sufficient sacral analgesia to inhibit pushing during the first stage of labor. The patient must not push before the cervix is fully dilated; otherwise, the patient might push a fetal lower extremity through her partially dilated cervix, which may result in fetal head entrapment. Early pushing may also increase the risk for a prolapsed umbilical cord. A bolus dose of local anesthetic solution that includes a lipid-soluble opioid (e.g., fentanyl, sufentanil) may be required to block the sacral segments and the reflex urge to push during the late first stage of labor. Use of a local anesthetic alone to eliminate low back and perineal discomfort results in extensive motor blockade, which may decrease the effectiveness of maternal expulsive efforts during the second stage. The advantages of the epidural administration of both a local anesthetic and a lipid-soluble opioid were confirmed by Benhamou et al.,34 who observed that a continuous epidural infusion of bupivacaine 0.0625% with sufentanil 0.25 µg/mL produced better maternal analgesia and less motor block than administration of bupivacaine 0.125% in parturients with a breech presentation.

Anesthesia for Vaginal Breech Delivery

The patient with a breech presentation should deliver in an operating room where an emergency abdominal delivery can be performed immediately. The anesthesia provider should consider administration of a nonparticulate antacid at the time of transfer to the delivery/operating room. The anesthesia provider should be prepared for emergency administration of general anesthesia at any time. Umbilical cord compression is common during the second stage of labor in a patient with a breech presentation. For these reasons, the mother may receive supplemental oxygen during vaginal breech delivery.

Provision of effective analgesia/anesthesia for vaginal breech delivery represents a true challenge for the anesthesia provider. During the second stage of labor, the anesthesia provider is asked to provide adequate analgesia (which should include neuroblockade of the sacral segments) while maintaining adequate maternal expulsive efforts. If a patient is unable to achieve spontaneous delivery of a vertex presentation, the obstetrician may perform instrumental vaginal delivery. In contrast, total breech extraction of a singleton fetus is unacceptable in modern obstetric practice. Most obstetricians insist on spontaneous delivery of the infant to the level of the umbilicus.

At any time, the anesthesia provider may be asked to quickly provide dense anesthesia for vaginal or cesarean delivery. Many obstetricians routinely apply Piper forceps to the aftercoming head. This maneuver requires adequate anesthesia and perineal muscle relaxation. Because a dilute solution of local anesthetic has been administered during the first stage of labor, it is often necessary to administer a more concentrated solution of local anesthetic at the time of delivery. Either 3% 2-chloroprocaine or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine and bicarbonate may be used to rapidly extend the epidural analgesia to anesthesia for operative delivery. To ensure adequate anesthesia for operative delivery, we begin to inject a more concentrated solution of local anesthetic at the first evidence of difficulty.

Perhaps the obstetrician’s greatest fear is the risk for fetal head entrapment. Most cases of this complication involve entrapment of the fetal head behind a partially dilated cervix. The head may also be entrapped by the perineum. Fetal head entrapment is more likely to occur in patients at less than 32 weeks’ gestation. Before 32 weeks’ gestation, the fetal head is larger than the wedge formed by the fetal buttocks and thighs. The lower extremities, buttocks, and abdomen may deliver before the cervix is fully dilated, and the cervix may then entrap the head. If this complication occurs, the obstetrician may choose one of the following three options: (1) performance of Dührssen incisions in the cervix, (2) relaxation of skeletal and cervical smooth muscle, or (3) cesarean delivery.

The performance of Dührssen incisions may be technically difficult. The obstetrician makes two or three radial incisions in the cervix at the 2-, 6-, and 10-o’clock positions.4 This procedure is associated with a high risk for maternal morbidity (e.g., genitourinary trauma, hemorrhage). The blood loss may be substantial and concealed. Bleeding within the peritoneal cavity may not be visible externally.

More often, the obstetrician requests that the anesthesia provider establish relaxation of skeletal and cervical smooth muscle. Smooth muscle represents less than 15% of total cervical tissue,35 and some physicians argue that it is not possible to provide profound relaxation of the cervix through smooth muscle relaxation. Nonetheless, the provision of both skeletal and smooth muscle relaxation often facilitates vaginal delivery of the aftercoming head. In the past, the technique of choice was rapid-sequence induction of general anesthesia, followed by administration of a high concentration (2 to 3 minimum alveolar concentration [MAC]) of a volatile halogenated agent. This technique results in uterine and cervical relaxation in 2 to 3 minutes. If fetal head entrapment results from perineal obstruction, delivery may soon follow the administration of succinylcholine.

Immediately after delivery, the anesthesia provider should discontinue administration of the volatile halogenated agent and substitute nitrous oxide, with or without an opioid. Administration of a high concentration of a volatile halogenated agent increases the risk for uterine atony and hemorrhage after delivery. Prompt discontinuation of the volatile halogenated agent, along with intravenous administration of oxytocin, should facilitate adequate uterine tone in most patients. Anesthesia should be maintained until the placenta is delivered, the episiotomy and lacerations are repaired, and hemostasis is secured.

In modern practice, intravenous or sublingual administration of nitroglycerin has nearly replaced the use of volatile halogenated agents as agents for uterine relaxation. Administration of nitroglycerin results in the release of nitric oxide, which helps mediate the relaxation of smooth muscle. Transient hypotension is common. Use of nitroglycerin for this purpose is based on case reports and small series of cases. Well-designed clinical trials of the use of nitroglycerin to provide uterine relaxation in obstetric emergencies are lacking, although the administration of nitroglycerin for this purpose appears safe for both the mother and the infant.36

Buhimschi et al.37 attempted to provide an objective assessment of the effect of nitroglycerin on uterine tone and contractility in laboring women. In a double-blind fashion, 12 parturients were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or sublingual nitroglycerin (three doses, 800 µg each) 10 minutes apart. Intrauterine pressure was measured with a sensor-tip catheter. Sublingual nitroglycerin did not reduce either uterine activity or tone, despite a significant (20%) reduction in maternal mean arterial pressure. The authors suggested that higher doses may be required but may increase the risk for maternal hypotension.

Published case reports have described clinically apparent uterine relaxation achieved with intravenous nitroglycerin doses ranging from 50 to 1500 µg. Sublingual sprays of metered-dose nitroglycerin (400 to 800 µg) may provide a more convenient means of administration, whereas intravenous administration may allow for more rigorous titration. Either sublingual or intravenous routes of administration appear to provide a rapid onset of uterine relaxation, and the effect typically is very brief. The patient should be warned about the acute onset of headache, and she should be treated with a vasopressor such as phenylephrine if hypotension occurs. The anesthesia provider should simultaneously prepare for the induction of general anesthesia should nitroglycerin not provide enough relaxation.

The use of epidural analgesia has likely lowered the incidence of fetal head entrapment during vaginal breech delivery for at least two reasons. First, epidural analgesia inhibits early pushing during the first stage of labor. Second, although epidural analgesia does not relax the cervix at delivery, it provides effective pain relief and skeletal muscle relaxation. A relaxed pelvic floor and perineum facilitates placement of Piper forceps and delivery of the aftercoming head. Moreover, effective analgesia and skeletal muscle relaxation allow an assistant to provide maternal suprapubic pressure, which helps maintain flexion of the fetal cervical spine during delivery.

Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

Spinal, epidural, or general anesthesia can be administered for cesarean delivery. At cesarean delivery, the obstetrician should perform a uterine incision that allows an atraumatic delivery of the infant. Rarely, the obstetrician may request provision of uterine relaxation even when a vertical uterine incision has been performed. Uterine relaxation may be necessary in cases of fetal malformations (e.g., sacral teratoma, hydrocephalus). When general anesthesia is used, the anesthesia provider may increase the concentration of the volatile halogenated agent. When neuraxial anesthesia is used, intravenous or sublingual administration of nitroglycerin, or intravenous administration of a beta-adrenergic tocolytic agent such as terbutaline, typically provides adequate relaxation. Rarely, it is necessary to perform intraoperative induction of general anesthesia followed by administration of a high concentration of a volatile halogenated agent.

Regardless of the route of delivery, all members of the obstetric care team should remember that newborn infants with a breech presentation tend to be more depressed than infants with a vertex presentation. An individual skilled in neonatal resuscitation should be immediately available.

Other Abnormal Presentations

Face Presentation

Face presentation occurs in 1 in 500 live births. Vaginal delivery can be achieved in 70% to 80% of infants with a face presentation if the mentum rotates to an anterior position.4 Manual efforts to flex the fetal cervical spine or convert an unfavorable mentum posterior position to a more favorable mentum anterior position are rarely successful.4

Brow Presentation

In patients with a brow presentation, the cervical spine position is intermediate between the full flexion of a normal vertex presentation and the full extension of a face presentation. Brow presentation occurs in approximately 1 in 1500 deliveries. Persistent brow presentation typically requires cesarean delivery due to dystocia. Spontaneous flexion or extension of the neck may occur during labor, which may allow vaginal delivery.4

Compound Presentation

Compound presentation (an extremity is prolapsed alongside the main presenting fetal part) occurs in 1 in 400 to 1 in 1200 deliveries. Most often, an upper extremity presents with the vertex. Umbilical cord prolapse is more common (10% to 20%), as is neurologic or musculoskeletal damage to the involved extremity.4 Labor and delivery may occur safely, but abdominal delivery is needed in patients with cord prolapse or arrest of labor. Manipulation of the prolapsed extremity should be avoided.4

Shoulder Presentation

A shoulder presentation (also known as a transverse lie) mandates performance of cesarean delivery except in two circumstances. First, successful external cephalic version may allow vaginal delivery. Second, the obstetrician may perform internal podalic version and total breech extraction of a second twin with a shoulder presentation.

Cesarean delivery of a fetus with a back-down transverse lie can be especially difficult with no presenting part to grasp. This presentation represents one of the few indications in contemporary obstetric practice for a classical uterine incision.

Multiple Gestation

Epidemiology

Monozygotic twins (which occur when a single fertilized ovum divides into two distinct individuals after a variable number of divisions) exhibit a constant incidence of approximately 4 per 1000 births. The incidence of dizygotic twins (which occur when two separate ova are fertilized) varies among races and by maternal age. In the United States, dizygotic twins occur most frequently among non-Hispanic black and white Americans, with an intermediate frequency among Asian Americans and Puerto Ricans, and least frequently among Native Americans and other Hispanic groups.38 The incidence increases from 15 per 1000 among women younger than 20 years of age to 53 per 1000 among women 35 to 39 years of age, 63 per 1000 among women 40 to 44 years of age, and 227 per 1000 among those 45 years of age and older.38 The incidence also increases with parity, independent of maternal age.39 In the United States the rate of multiple gestation increased by 75% between 1980 and 2010.38 Twin births represented 3.3% of all births in 2010.38 Higher-order multiples (e.g., triplets) have declined in frequency from 0.2% of all live births in 1998 to 0.14% in 2010. Delayed childbearing and spontaneous twinning among women older than age 30 appears to explain one third of the increase in the rate of multiple gestation between 1980 and 2010, with the remainder attributed to greater use of assisted reproductive technologies.40

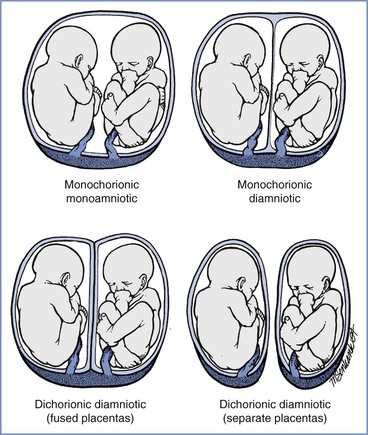

Placentation

Placentas in multiple gestation may be (1) dichorionic diamniotic, (2) monochorionic diamniotic, or (3) monochorionic monoamniotic (Figure 35-5). In all occurrences of dizygotic twins, the placenta is dichorionic diamniotic. A dichorionic diamniotic placenta is also present if monozygotic twinning occurs during the first 2 to 3 days after fertilization. Twinning between 3 and 8 days commonly results in a monochorionic diamniotic placenta. Monochorionic monoamniotic placentas are found when twinning occurs at 8 to 13 days. Embryonic cleavage between 13 and 15 days results in conjoined twins with a monochorionic monoamniotic placenta. Chorionicity is best determined by ultrasonography in the first or early second trimester.41

FIGURE 35-5 Placentation in twin pregnancies. (Newman R, Unal ER. Multiple gestations. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2012:674.)

The type of placentation determines the likelihood of vascular communications. Vascular communications occur in nearly all monochorionic placentas and are rare in dichorionic placentas.42 Vascular communications may result in twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and intrauterine fetal death. Monochorionic placentation also increases the risk for intrauterine fetal death from other causes (e.g., cord accident).42

Physiologic Changes

Multiple gestation accelerates and may exaggerate the physiologic and anatomic changes of pregnancy. Of interest to the anesthesia provider, multiple gestation intensifies the cardiovascular and pulmonary changes of pregnancy. In contrast, the renal, hepatic, and central nervous system changes resemble those that occur in women with a singleton fetus.

Increased uterine size, especially near term, results in a reduction in both total lung capacity and functional residual capacity. During periods of hypoventilation or apnea, hypoxemia develops more rapidly because of the decreased functional residual capacity and an increased maternal metabolic rate. However, a cross-sectional study demonstrated no significant difference in respiratory function between 68 women with a twin pregnancy and 140 women with a singleton pregnancy.43 Maternal weight increases at a greater rate after 30 weeks’ gestation in women with multiple gestation,44 a process that may increase the risk for difficult tracheal intubation and ventilation. Greater uterine size displaces the stomach cephalad, decreasing the competence of the lower esophageal sphincter and increasing the risk for pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.

Maternal plasma volume increases by an additional 750 mL with twin gestation.45 Relative or actual anemia often occurs. Likewise, multiple gestation results in a 20% greater increase in cardiac output than occurs in women with a singleton fetus, owing to a greater stroke volume (15%) and a higher heart rate (3.5%).46 The greater fetal weight and larger volume of amniotic fluid predispose the mother with multiple gestation to aortocaval compression and the supine hypotension syndrome.

Obstetric Complications

Fetal Complications

Fetal complications include those related solely to multiple gestation (e.g., twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome) and those related to abnormal presentation (e.g., prolapsed cord) (Box 35-3).

Twin-to-Twin Transfusion.

Nearly all monochorionic twin placentas have vascular anastomoses. Deep arteriovenous anastomoses create a common villous compartment in about half of monochorionic twin placentas. Most of these anastomoses have little fetal consequence. Those with deep arteriovenous vascular communications may result in twin-to-twin transfusion,47 in which one twin becomes the donor and the other twin becomes the recipient. The donor twin is smaller and is at risk for fetal growth restriction (also known as intrauterine growth restriction) and anemia. The recipient twin is plethoric and is at risk for volume overload and cardiac failure. Alternative explanations for the syndrome include unequal blood volumes secondary to compression of a velamentous umbilical cord insertion and higher arterial blood pressure in the donor than in the recipient. Twin-to-twin transfusion increases both the perinatal mortality rate and the risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in survivors.48

The therapeutic options most often considered are decompression amniocentesis, interruption of the placental vessel communications, amniotic septostomy, and selective feticide.49 Selective fetoscopic laser photocoagulation may be sufficient to address the vascular anastomoses. Decompression amniocentesis or serial amnioreduction may improve circulation to a “stuck” donor twin, allowing restoration of normal amniotic fluid volume and “catch-up” fetal growth. Compared with serial amnioreduction, septostomy has the advantage of requiring only a single procedure.50 Increasing evidence supports the use of endoscopic laser coagulation to improve perinatal outcome.51–53

Fetal Growth Restriction.

Twin-to-twin transfusion represents only one of the potential causes of fetal growth restriction in multiple gestation. The polyhydramnios within one fetal sac may limit the growth of the other fetus. In patients with three or more fetuses, limited intrauterine size may restrict fetal growth. Of course, factors that cause fetal growth restriction in singleton pregnancies also may cause fetal growth restriction in multiple gestation (e.g., uteroplacental insufficiency, chromosomal abnormalities).

Preterm Labor.

Patients with multiple gestation are at high risk for preterm labor and delivery. Preterm labor occurs in 52% of women with twins resulting from in vitro fertilization compared with 22% of women with spontaneous twins.54 Sixty percent of women with twins deliver before 37 weeks’ gestation, and only 6.4% of triplet pregnancies reach term.55 Routine use of bed rest, prophylactic cerclage, vaginal progesterone, and/or tocolytic therapy has not been shown to improve perinatal outcome in multiple gestation pregnancies.56 When preterm labor occurs, the patient may receive parenteral tocolytic therapy to facilitate administration of betamethasone to accelerate fetal lung maturation, or magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection, or both. The side effects of magnesium and other tocolytic agents may affect the response to anesthesia (see Chapter 34) and may increase the risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Multiple gestation most likely increases the risk for pulmonary edema associated with tocolytic therapy.57

Abnormal Presentation.

Multiple gestation is associated with a higher incidence of abnormal presentation, which results in part from the need to accommodate two or more fetuses within the uterine cavity. Malpresentation increases the risk for umbilical cord prolapse, which may occur either before or after delivery of the first infant.

Morbidity and Mortality.

Approximately 9% of all cases of perinatal mortality result from multiple gestation.58 The perinatal mortality rate in twin pregnancies is almost three times greater than that associated with singleton pregnancies (16 deaths per 1000 births versus 6 per 1000 births, respectively).58 Preterm delivery accounts for most of this increase, although twins and triplets also have a higher weight-specific mortality, which may be related to twin-to-twin transfusion, congenital malformations, preeclampsia, malpresentation, and/or prolapsed umbilical cord. Some maternal-fetal medicine specialists advocate selective multifetal reduction to reduce the risk for maternal morbidity and the perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with three or more fetuses; this issue is a matter of great controversy. The ACOG59 has stated:

High-order multiple gestation creates a medical and ethical dilemma. If a pregnancy with 4 or more fetuses is continued, the probability is high that not all fetuses will survive intact and that the woman will experience serious morbidity. However, fetal reduction to triplet or twin gestations is associated with a significant risk of losing either another fetus or the whole pregnancy.

Intensive inpatient monitoring may improve perinatal survival of monoamniotic twins. In a retrospective analysis of 87 women who had living twins at 24 weeks’ gestation, there were no intrauterine fetal deaths among 43 women who were admitted electively for inpatient surveillance (at a median gestational age of 26.5 weeks).60 In comparison, among women who were monitored as outpatients and admitted only for routine obstetric indications (at a median gestational age of 30.1 weeks), the rate of intrauterine fetal death was 14.8%.60 Intensive surveillance may also benefit monochorionic diamniotic pregnancies.61 The long-term outcome of the complications of monochorionicity remains an area of limited knowledge.62

Johnson and Zhang63 evaluated outcome for 150,386 sets of twins and 5240 sets of triplets born between 1995 and 1997; fetal death at 20 weeks’ gestation or later occurred in 2.6% of twin gestations and 4.3% of triplet gestations. The investigators noted that “survival of the remaining fetuses was inversely related to the time of the first fetal demise.”63 Opposite-gender twins were more likely to survive, possibly reflecting the absence of monochorionic placentation. In monochorionic twin gestations complicated by twin-to-twin transfusion and fetal death, approximately 40% of the surviving twins experience mortality or serious neurodevelopmental morbidity.64 Death of one fetus may occur well before term. Obstetric management decisions are based on the cause of death and the status of both the surviving fetus and the mother. If the cause of death was an abnormality of the fetus rather than maternal or uteroplacental pathology, expectant management of the pregnancy may be warranted.42,59 Development of maternal disseminated intravascular coagulation from dead fetal tissue is a theoretical complication that appears to occur rarely.59

Multiple gestation is also associated with an increased risk for neonatal morbidity and mortality. Despite a 95% neonatal survival rate, triplets may have a significantly greater risk for intraventricular hemorrhage and retinopathy of prematurity.65

Order of Delivery.

Birth order does not seem to influence perinatal outcome in contemporary obstetric practice.59,66 Administration of neuraxial anesthesia may improve the outcome for the second twin. In 1987, Crawford67 observed that among women who received epidural analgesia, the two twins had similar umbilical cord blood pH measurements. In contrast, among women who received general anesthesia, the second twin tended to be more acidotic than the first. Likewise, Jarvis and Whitfield68 reported no difference in outcome for first and second twins when the mother received epidural analgesia. Administration of general anesthesia is increasingly rare for cesarean delivery in women with multiple gestation.69

Maternal Complications

Multiple gestation increases the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality (Box 35-4), even with adjustment of data for confounding factors.70 The ACOG59 has stated: “Women with multiple gestations are nearly 6 times more likely to be hospitalized with complications, including preeclampsia, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption, pyelonephritis, and postpartum hemorrhage.”59 The incidence of maternal complications increases in proportion to the number of fetuses. Nearly all triplet gestations are associated with antenatal and/or postnatal maternal complications.71 Abdominal distention and diaphragmatic elevation can cause respiratory distress and may necessitate early delivery in some patients with three or more fetuses. The increased incidence of cesarean delivery contributes to the higher risk for maternal morbidity and mortality associated with multiple gestation.

Multiple gestation (and the use of assisted reproductive technologies72) increases both the incidence and severity of preeclampsia.42 Preeclampsia prompts delivery by 34 weeks’ gestation in as many as 70% of patients with quadruplet pregnancies.73

Blood loss with delivery is approximately 500 mL greater in multiple gestation pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies.42 Uterine distention increases the risk for uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage. Most cases of atony respond to standard pharmacologic therapy (e.g., oxytocin, methylergonovine, 15-methyl prostaglandin F2α [carboprost]). Persistent uterine atony may require the performance of a uterine brace suture or emergency hysterectomy.

Obstetric Management

Delivery at 38 weeks’ gestation for twins and 35 weeks’ gestation for triplets may be associated with the lowest risk for perinatal mortality.59 Twin gestation itself does not contraindicate labor and vaginal delivery. However, multiple gestation is associated with a higher incidence of cesarean delivery. Most obstetricians favor cesarean delivery for all patients with three or more fetuses.42

A meta-analysis of four studies involving 1932 infants found no difference in perinatal or neonatal mortality, neonatal morbidity, or maternal morbidity between twins born through planned cesarean delivery and those born through vaginal delivery unless the first twin (twin A) was in a breech presentation.74 Other studies have shown no maternal benefit to a prophylactic cesarean delivery, whereas maternal febrile morbidity is higher and the mother’s risks for future pregnancies are increased.75,76 Recent studies have found that neonatal morbidity is lower after vaginal delivery compared with scheduled cesarean delivery, even if only the second twin is considered.77,78 A cohort study of 2597 twin deliveries at or after 34 weeks’ gestation, with the first twin in a cephalic presentation, found that intrapartum and postpartum neonatal complications occurred in 26.5% of vaginal deliveries and 31.7% of scheduled cesarean deliveries (P = 0.005).77 The authors concluded that their findings do not support a policy of planned cesarean delivery for twin pregnancies at or after 34 weeks’ gestation.77 A meta-analysis of 39,571 twin pregnancies found that neonatal morbidity was lower after vaginal delivery than after cesarean delivery for twin A, but there was no significant difference in neonatal morbidity between the two modes of delivery for twin B.78 When outcomes were stratified for both presentation and mode of delivery, the mortality rate was lower after vaginal delivery than after cesarean delivery for both vertex and non-vertex twin B.78

Both fetuses have a vertex presentation in 30% to 50% of cases of twin gestation, and in 25% to 40% of cases the presentation is a vertex/breech combination. The remaining patients have various combinations of vertex, breech, and transverse lie. Most obstetricians allow a trial of labor if both twins have vertex presentation. Similarly, a majority of obstetricians opt for cesarean delivery if the first twin has a breech or shoulder presentation. Notwithstanding the results of recent studies,74,77,78 controversy remains regarding the ideal management in cases in which twin A has a vertex presentation and twin B has a nonvertex presentation.59,75

Twin A

Decisions regarding the method of delivery typically revolve around the gestational age and presentation of twin A. An obstetrician who is unwilling to allow a trial of labor in a patient with a singleton breech presentation is unlikely to allow a trial of labor in a patient with a breech presentation for twin A. Moreover, if twin A has a breech presentation and twin B has a vertex presentation, the chins may become interlocked during labor and delivery. This complication occurs infrequently, but the consequences can be devastating.42 Other indications for cesarean delivery of twin A include (1) evidence of discordant growth (especially if twin B is larger than twin A), (2) twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, (3) selected congenital anomalies, and (4) evidence of uteroplacental insufficiency.42 A trial of labor mandates continuous FHR monitoring of both fetuses. After amniotomy, an electrocardiography lead may be placed on the scalp of twin A and Doppler ultrasonography may be used to monitor twin B.

The unanticipated case of head entrapment, deflexed head, or locked twins may necessitate emergency abdominal delivery of both twins. The obstetrician proceeds with cesarean delivery while an assistant supports the exteriorized body of twin A. The obstetrician applies gentle traction on the head while the infant’s body is guided back into the vagina. This can be accomplished without major injury to the infant or the mother.79

Twin B

If twin A is delivered vaginally, the obstetrician must make a decision about the method of delivery of twin B. If twin B has a vertex presentation and the head is well applied to the cervix, the obstetrician may allow the patient to resume labor and await spontaneous vaginal delivery. Rarely, if twin B has a vertex presentation but the head is not well applied to the cervix, the obstetrician may perform internal podalic version and total breech extraction.

For the twin B with nonvertex presentation, options include (1) external cephalic version followed by a resumption of labor, (2) internal podalic version and total breech extraction, and (3) performance of cesarean delivery. Real-time ultrasonography facilitates the performance of external cephalic version. This procedure is successful in approximately 70% of cases. The likelihood of success is not associated with parity, gestational age, or birth weight.80 One study noted that mothers who received epidural anesthesia were more relaxed and tolerated the procedure better than those who did not receive epidural anesthesia.80

Delivery of twin B is the one situation in contemporary obstetric practice in which internal podalic version and total breech extraction are considered appropriate. Indeed, breech extraction may be preferable to external cephalic version at the time of delivery. After vaginal delivery of twin A, the second twin requires cesarean delivery in approximately 10% of cases.81 Predictors of emergency cesarean delivery of twin B include malpresentation, nonreassuring FHR tracing, cephalopelvic disproportion, and cord prolapse.81 In a cohort study of twin pregnancies that used active management of the second stage of labor, which included breech extraction of the second twin and internal version of a nonengaged second twin, no patients required a cesarean delivery for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin.82 The investigators stated that an epidural catheter was placed and tested before delivery in all patients that had a trial of labor, and all twin deliveries occurred in the operating room with an anesthesiologist present.82 The obstetrician will opt for total breech extraction of twin B only if there is evidence that twin B is not larger than twin A. Antepartum ultrasonographic examination allows the obstetrician to assess the head size and weight of both fetuses. If twin B is not larger than twin A, the pelvis and cervical dilation are probably adequate for vaginal delivery of twin B, provided that the cervix has not begun to contract.

In the past, obstetricians favored the delivery of twin B within 15 to 30 minutes of delivery of twin A. However, most data supporting this practice were obtained before the use of intrapartum FHR monitoring. In a review of 118 twin deliveries, Leung et al.83 demonstrated an association between the twin-twin delivery interval and the umbilical cord blood gas and pH measurements for twin B. The investigators noted that continuous FHR monitoring is essential; 73% of the second twins not delivered by 30 minutes required operative delivery because of a nonreassuring FHR tracing. A German retrospective analysis of 4110 twin pregnancies suggested that the interval between delivery of twins is an independent risk factor for adverse short-term outcomes for twin B.84 Continuous FHR monitoring of twin B is essential.

Anesthetic Management

Labor and Vaginal Delivery

Epidural analgesia provides optimal analgesia and flexibility for subsequent anesthetic needs. The anesthesia provider must be vigilant, because obstetric conditions and anesthetic requirements may change rapidly. Given the greater risk for cesarean delivery in patients with multiple gestation, the anesthesia provider should aim for optimal epidural anesthesia. If there is any question regarding the location of the catheter or the efficacy of the block, the catheter should be removed and replaced.

Patients with multiple gestation may be at increased risk for aortocaval compression and hypotension during the administration of neuraxial anesthesia. Use of the full lateral position, both during and after induction of epidural anesthesia, reduces the risk for aortocaval compression. Because these patients are at increased risk for uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage, establishment of large-bore intravenous access is recommended before delivery.

Patients with multiple gestation should deliver in a room where an emergency abdominal delivery can be performed immediately. As the time for delivery of twin A nears, we augment the intensity of epidural blockade to optimize analgesia. We typically extend the sensory level to approximately T8 to T6 using a solution of local anesthetic that is more concentrated than that used earlier during labor. Effective anesthesia facilitates the performance of internal podalic version and total breech extraction of twin B, and it also enables the extension of anesthesia for cesarean delivery if necessary. We prepare a syringe of 3% 2-chloroprocaine to be used if emergency extension of epidural anesthesia is required.

We prefer to administer CSE anesthesia for vaginal delivery in patients with multiple gestation who do not have preexisting epidural analgesia. We prefer not to administer single-shot spinal anesthesia for vaginal delivery in those patients because of its lack of flexibility in cases of rapidly changing conditions. However, spinal anesthesia may be appropriate when delivery appears imminent in a patient without preexisting epidural labor analgesia.

Vaginal Delivery of Twin A/Operative Delivery of Twin B

The flexibility associated with epidural analgesia is especially advantageous if the obstetrician delivers twin A vaginally and twin B abdominally. We administer a nonparticulate antacid at the first sign of obstetrician concern, or even before proceeding to the operating room. We inject additional local anesthetic to extend the surgical sensory level to approximately T4. In cases of prolonged fetal bradycardia, it may be necessary to administer general anesthesia if adequate neuraxial anesthesia cannot be achieved rapidly. Typically this problem can be avoided if (1) both the level and intensity of anesthesia are optimized at the time of delivery of twin A and (2) the anesthesia provider is present in the room and gives attention to both the FHR tracing and the obstetrician.

If the obstetrician opts for internal podalic version and total breech extraction of twin B, it is better to perform the procedure shortly after the delivery of twin A, before the uterus and the cervix begin to contract. Pain relief and skeletal muscle relaxation (both provided by epidural anesthesia) facilitate internal version and total breech extraction of twin B. In some cases, pharmacologic uterine relaxation may be required to facilitate internal version and breech extraction of twin B. Sublingual (400 to 800 µg) or intravenous (100 to 250 µg) administration of nitroglycerin should provide adequate relaxation for internal podalic version.85,86 Intravenous or subcutaneous terbutaline 250 µg may also be used for uterine relaxation. If this maneuver is unsuccessful, rapid-sequence induction of general anesthesia, followed by administration of a high concentration of a volatile halogenated agent (as discussed earlier) may be needed.

Cesarean Delivery

Epidural, spinal, or general anesthesia can be safely administered for elective abdominal delivery. Spinal anesthesia is increasingly preferred by many anesthesia providers. A historical preference for epidural anesthesia was based on the gradual onset of sympathetic blockade, which was thought to reduce the incidence of severe hypotension. It has been long believed that women with multiple gestation are at higher risk for hemodynamic instability during administration of neuraxial anesthesia than women with a singleton gestation. Ngan Kee et al.87 compared the incidence of hypotension and vasopressor requirements in women with multiple and singleton gestations undergoing cesarean delivery with spinal anesthesia. There were no differences between groups in maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Comparison of brachial artery and popliteal artery blood pressures allows the detection of occult supine hypotension, which results in reduced uteroplacental perfusion in the presence of a normal brachial artery pressure. If either hypotension or occult supine hypotension is detected, additional left uterine displacement or displacement to the other side may resolve the problem. A nonreassuring FHR tracing for either infant should also prompt the administration of additional efforts to optimize uteroplacental perfusion.

Jawan et al.88 found that women with multiple gestation had a greater cephalad spread of neuroblockade with spinal anesthesia than women with a singleton gestation, whereas Ngan Kee et al.87 did not. Similarly, Behforouz et al.89 found no difference in the extent of sensory blockade after administration of epidural anesthesia between women with higher-order multiple gestation pregnancies and women with a singleton gestation. In any case, any difference that may exist is likely to be of little clinical significance.

Vallejo and Ramanathan90 demonstrated that mean umbilical venous and umbilical arterial lidocaine concentrations were 35% to 53% higher in twin newborns than in singleton newborns exposed to epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Mean fetal-to-maternal lidocaine ratios were at least 18% higher in the twin newborns than in the singleton newborns. The investigators speculated that this difference may be a result of the greater maternal cardiac output and plasma volume associated with twin gestation as well as the decreased total plasma protein concentration, which leads to an increase in the free lidocaine concentration.90 The clinical relevance of these findings is unclear.

When general anesthesia is used, the greater oxygen consumption and decreased functional residual capacity associated with multiple gestation increase the risk for maternal hypoxemia during periods of apnea. Adequate denitrogenation (preoxygenation) is essential.

The presence of two or more fetuses results in a prolonged uterine incision-to-delivery interval because of the longer time required to deliver multiple infants. A prolonged interval increases the risk for umbilical cord blood acidemia and neonatal depression. Neonatal depression is less likely with neuraxial anesthesia than with general anesthesia.68 In any case, an individual skilled in neonatal resuscitation should be immediately available.

References

1. Fitzpatrick M, McQuillan K, O’Herlihy C. Influence of persistent occiput posterior position on delivery outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1027–1031.

2. Lieberman E, Davidson K, Lee-Parritz A, Shearer E. Changes in fetal position during labor and their association with epidural analgesia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:974–982.

3. Hickock DE, Gordon DC, Millberg JA, et al. The frequency of breech presentation by gestational age at birth: a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:851–852.

4. Lanni S, Seeds J. Malpresentations and shoulder dystocia. Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th edition. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia; 2012:388–414.

5. Pop VJ, Brouwers EP, Wijnen H, et al. Low concentrations of maternal thyroxin during early gestation: a risk factor of breech presentation? BJOG. 2004;111:925–930.

6. Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2000;356:1375–1383.

7. Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Dalaker K, Irgens LM. Perinatal mortality in breech presentation sibships. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:775–780.

8. Lau TK, Lo KW, Rogers M. Pregnancy outcome after successful external cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:218–223.

9. Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ, et al. Maternal outcomes at 2 years after planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the international randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:917–927.

10. Schiff E, Friedman SA, Mashiach S, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcome of 846 term singleton breech deliveries: seven-year experience at a single center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:18–23.

11. American College of Obstetrician and Gynecologists. External cephalic version. [ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 13. Washington, DC] February 2000.

12. Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, et al. External cephalic version-related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1143–1151.

13. Kok M, Cnossen J, Gravendeel L, et al. Clinical factors to predict the outcome of external cephalic version: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:630.e1–630.e7.

14. Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Ross SJ, et al. The Early External Cephalic Version (ECV) 2 Trial: an international multicentre randomised controlled trial of timing of ECV for breech pregnancies. BJOG. 2011;118:564–577.

15. Chan LY, Tang JL, Tsoi KF, et al. Intrapartum cesarean delivery after successful external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:155–160.

16. Fernandez CO, Bloom SL, Smulian JC, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of terbutaline for external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:775–779.

17. Hilton J, Allan B, Swaby C, et al. Intravenous nitroglycerin for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:560–567.

18. Cluver C, Hofmeyr GJ, Gyte GM, Sinclair M. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1).

19. Goetzinger KR, Harper LM, Tuuli MG, et al. Effect of regional anesthesia on the success rate of external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1137–1144.

20. Fok WY, Chan LW, Leung TY, Lau TK. Maternal experience of pain during external cephalic version at term. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:748–751.

21. Suen SS, Khaw KS, Law LW, et al. The force applied to successfully turn a foetus during reattempts of external cephalic version is substantially reduced when performed under spinal analgesia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:719–722.

22. Weiniger CF, Ginosar Y, Elchalal U, et al. External cephalic version for breech presentation with or without spinal analgesia in nulliparous women at term: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1343–1350.

23. Weiniger CF, Ginosar Y, Elchalal U, et al. Randomized controlled trial of external cephalic version in term multiparae with or without spinal analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:613–618.

24. Sullivan JT, Grobman WA, Bauchat JR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of combined spinal-epidural analgesia on the success of external cephalic version for breech presentation. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:328–334.

25. Lavoie A, Guay J. Anesthetic dose neuraxial blockade increases the success rate of external fetal version: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:408–414.

26. Cherayil G, Feinberg B, Robinson J, Tsen LC. Central neuraxial blockade promotes external cephalic version success after a failed attempt. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1589–1592.

27. Su M, McLeod L, Ross S, et al. Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcome in the Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:740–745.

28. Whyte H, Hannah ME, Saigal S, et al. Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the international randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:864–871.

29. Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hodnett ED, et al. Outcomes at 3 months after planned cesarean vs planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term: the international randomized Term Breech Trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1822–1831.

30. Tharin JEH, Rasmussen S, Krebs L. Consequences of the Term Breech Trial in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:767–771.

31. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. ACOG Committee Opinion. 2006 [No. 340. Washington, DC, July] .

32. Chinnock M, Robson S. Obstetric trainees’ experience in vaginal breech delivery: implications for future practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:900–903.

33. Goffinet F, Carayol M, Foidart JM, et al. Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1002–1011.

34. Benhamou D, Mercier FJ, Ben Ayed M, Auroy Y. Continuous epidural analgesia with bupivacaine 0.125% or bupivacaine 0.0625% plus sufentanil 0.25 microg.mL(-1): a study in singleton breech presentation. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2002;11:13–18.

35. Danforth DN. The distribution and functional activity of the cervical musculature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1261–1271.

36. Caponas G. Glyceryl trinitrate and acute uterine relaxation: a literature review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:163–177.

37. Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Malinow AM, et al. The effect of fundal pressure manoeuvre on intrauterine pressure in the second stage of labour. BJOG. 2002;109:520–526.

38. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1–72.

39. Hrubec Z, Robinette CD. The study of human twins in medical research. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:435–441.

40. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ. Three decades of twin births in the United States, 1980-2009. [NCHS Data Brief No. 8. Hyattsville, MD] January 2012.

41. Lee YM, Cleary-Goldman J, Thaker HM, Simpson LL. Antenatal sonographic prediction of twin chorionicity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:863–867.

42. Newman R, Unal ER. Multiple gestations. Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia; 2012.

43. McAuliffe F, Kametas N, Costello J, et al. Respiratory function in singleton and twin pregnancy. BJOG. 2002;109:765–769.

44. Hickok DE, Pederson AL, Worthington-Roberts B. Weight gain patterns during twin gestation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89:642–646.

45. Thomsen JK, Fogh-Andersen N, Jaszczak P. Atrial natriuretic peptide, blood volume, aldosterone, and sodium excretion during twin pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:14–20.

46. Kametas NA, McAuliffe F, Krampl E, et al. Maternal cardiac function in twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:806–815.

47. Bermudez C, Becerra CH, Bornick PW, et al. Placental types and twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:489–494.

49. Habli M, Lim FY, Crombleholme T. Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome: a comprehensive update. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:391–416.

50. Moise KJ Jr, Dorman K, Lamvu G, et al. A randomized trial of amnioreduction versus septostomy in the treatment of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:701–707.

51. Roberts D, Neilson JP, Weindling AM. Interventions for the treatment of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1).

52. Crombleholme TM, Shera D, Lee H, et al. A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial of amnioreduction vs selective fetoscopic laser photocoagulation for the treatment of severe twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:396.e1–396.e9.