Chapter 2 Pharmacokinetics

Basic Concepts

Drug Transfer

Active Transport

ATP Dependence

Examples of the ATP binding cassette group of transporters include the multidrug resistance transporters (MDR transporters) such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp, MDR1 or ABCB1).

Examples of the ATP binding cassette group of transporters include the multidrug resistance transporters (MDR transporters) such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp, MDR1 or ABCB1).

P-glycoprotein is an efflux transporter that transports drugs out of cell to the extracellular space.

P-glycoprotein is an efflux transporter that transports drugs out of cell to the extracellular space. P-glycoprotein plays an important role in drug pharmacokinetics and in drug interactions.

P-glycoprotein plays an important role in drug pharmacokinetics and in drug interactions.

Drug Properties

Drug Formulations (Table 2-1)

Solid formulations (e.g., tablets, capsules, suppositories) must disintegrate to release the drug. Disintegration of the dosage form may be compromised under certain conditions (e.g., dry mouth caused by aging, disease, or concurrent drug treatment slows dissolution of nitroglycerin tablets). On the other hand, drugs may be specifically formulated to allow disintegration only in certain sections of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g., enteric-coated tablets disintegrate in the small intestine), for the purpose of protecting the drug from destruction by gastric acid of the stomach (e.g., erythromycin) or protecting the stomach from an irritant drug (e.g., enteric-coated aspirin). Tablets and capsules may also be formulated to slowly release drugs (controlled-release, extended-release, or sustained-release formulations) and prolong their duration of action. Sustained-release formulations are particularly useful for drugs that have very short durations of action (see Table 2-1).

Solid formulations (e.g., tablets, capsules, suppositories) must disintegrate to release the drug. Disintegration of the dosage form may be compromised under certain conditions (e.g., dry mouth caused by aging, disease, or concurrent drug treatment slows dissolution of nitroglycerin tablets). On the other hand, drugs may be specifically formulated to allow disintegration only in certain sections of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g., enteric-coated tablets disintegrate in the small intestine), for the purpose of protecting the drug from destruction by gastric acid of the stomach (e.g., erythromycin) or protecting the stomach from an irritant drug (e.g., enteric-coated aspirin). Tablets and capsules may also be formulated to slowly release drugs (controlled-release, extended-release, or sustained-release formulations) and prolong their duration of action. Sustained-release formulations are particularly useful for drugs that have very short durations of action (see Table 2-1). Semisolid formulations include creams, ointments, and pastes. These formulations are generally for topical application to the skin and require liberation and diffusion of the drug across the skin.

Semisolid formulations include creams, ointments, and pastes. These formulations are generally for topical application to the skin and require liberation and diffusion of the drug across the skin. Liquid formulations may be suspensions or solutions, which do not require disintegration of the formulation and thus are generally absorbed more readily than solid formulations. Suspensions or solutions are also advantageous for patients who cannot swallow tablets or capsules. Drugs in suspension are not dissolved in the liquid vehicle. Therefore, the drug must first dissolve before it can be absorbed. Drugs in solution are already dissolved. Consequently, solutions are generally absorbed more rapidly than suspensions. Drug solutions may also be administered directly into the bloodstream.

Liquid formulations may be suspensions or solutions, which do not require disintegration of the formulation and thus are generally absorbed more readily than solid formulations. Suspensions or solutions are also advantageous for patients who cannot swallow tablets or capsules. Drugs in suspension are not dissolved in the liquid vehicle. Therefore, the drug must first dissolve before it can be absorbed. Drugs in solution are already dissolved. Consequently, solutions are generally absorbed more rapidly than suspensions. Drug solutions may also be administered directly into the bloodstream. Polymer formulations are a special category of solid formulations that incorporate the drug into a matrix that then gradually releases the drug over a prolonged period of time or at specific locations. Examples include transdermal patches and drug-eluting stents. Novel polymer-based formulations for intravenous (IV) delivery are also being designed.

Polymer formulations are a special category of solid formulations that incorporate the drug into a matrix that then gradually releases the drug over a prolonged period of time or at specific locations. Examples include transdermal patches and drug-eluting stents. Novel polymer-based formulations for intravenous (IV) delivery are also being designed.TABLE 2-1 Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of Different Drug Formulations

| Drug Formulations | Examples | General Pharmacokinetic Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Solids |

Drug Chemistry

Molecular size and shape. Smaller molecules are absorbed more readily. Drug shape affects affinity of the drug for carrier molecules or other binding sites such as plasma proteins or tissue. Drugs of similar structure may exhibit competition for such binding sites, which can affect their pharmacokinetics.

Molecular size and shape. Smaller molecules are absorbed more readily. Drug shape affects affinity of the drug for carrier molecules or other binding sites such as plasma proteins or tissue. Drugs of similar structure may exhibit competition for such binding sites, which can affect their pharmacokinetics.Effect of pH

For drugs that are weak acids, the following equation applies, where HA = drug with proton, which is therefore nonionized. H+ = proton, and A− is the ionized drug.

For drugs that are weak acids, the following equation applies, where HA = drug with proton, which is therefore nonionized. H+ = proton, and A− is the ionized drug.

Under basic conditions, weak acids are ionized to a greater extent (because the basic environment will shift the reaction to the right).

Under basic conditions, weak acids are ionized to a greater extent (because the basic environment will shift the reaction to the right). Under acidic conditions, weak acids are nonionized to a greater extent (because the acidic environment will shift the reaction to the left).

Under acidic conditions, weak acids are nonionized to a greater extent (because the acidic environment will shift the reaction to the left). The greater the difference between the pH and the pKa, the greater the degree of ionization or nonionization.

The greater the difference between the pH and the pKa, the greater the degree of ionization or nonionization. The relationship between the pH of the drug’s environment and the degree of its ionization is determined by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

The relationship between the pH of the drug’s environment and the degree of its ionization is determined by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

For drugs that are weak bases, the reverse is true compared with weak acids: HB+ = drug with proton, which is therefore ionized. H+ = proton, and B is the nonionized drug.

For drugs that are weak bases, the reverse is true compared with weak acids: HB+ = drug with proton, which is therefore ionized. H+ = proton, and B is the nonionized drug.

Under basic conditions, weak bases are nonionized to a greater extent (because the basic environment will shift the reaction to the right).

Under basic conditions, weak bases are nonionized to a greater extent (because the basic environment will shift the reaction to the right). Under acidic conditions, weak bases are ionized to a greater extent (because the acidic environment will shift the reaction to the left).

Under acidic conditions, weak bases are ionized to a greater extent (because the acidic environment will shift the reaction to the left). Again, the greater the difference between the pH and the pKa, the greater the degree of ionization or nonionization.

Again, the greater the difference between the pH and the pKa, the greater the degree of ionization or nonionization. The relationship between the pH of the drug’s environment and the degree of its ionization is determined by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

The relationship between the pH of the drug’s environment and the degree of its ionization is determined by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

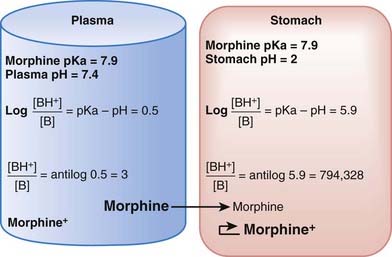

The practical implications are as follows: The ionized form of the drug may become stranded in certain locations. This effect, referred to as ion trapping or pH trapping, occurs when drugs accumulate in a certain body compartment because they can diffuse into this area, but then become ionized owing to the prevailing pH and are unable to diffuse out of this location. An example, shown in Figure 2-1, is the trapping of basic drugs (e.g., morphine, pKa 7.9) in the stomach. The drug is approximately 50% nonionized in the plasma (pH approximately 7.4) because it is in an environment with a pH close to its pKa. In the stomach (pH approximately 2), the drug is highly ionized (approximately 200,000×), it cannot diffuse across the cells lining the stomach, and the drug molecules are trapped in the stomach.

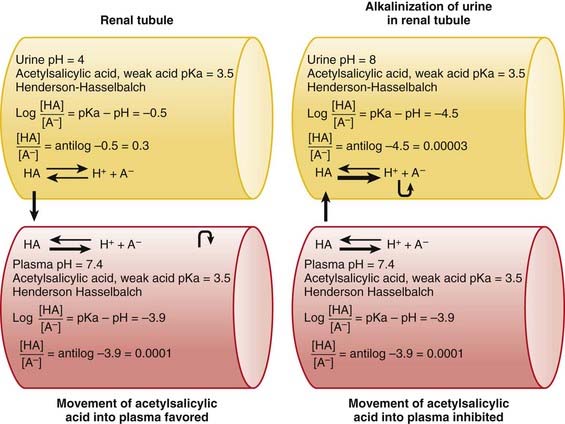

The concepts of acidic and basic drugs and their relative ionization at different pH values can be used clinically. For example, acidification of the urine is used to increase the elimination of amphetamine, a basic drug with pKa approximately 9.8. Rendering the urine acidic increases the amount of amphetamine in the ionized state, preventing its reabsorption from the urine into the bloodstream. Conversely, alkalinization of the urine is used to increase the excretion of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), an acidic drug. Increasing the pH of urine above the pKa of acetylsalicylic acid increases the proportion of the drug in the ionized state by about 10,000 times. The ionized form of the drug is not able to be reabsorbed across the renal tubule into the bloodstream. Moreover, the low concentration of the non-ionized form in the renal tubule compared with that in the blood favors diffusion of the non-ionized drug into the renal tubules (see Figure 2-2).

Absorption

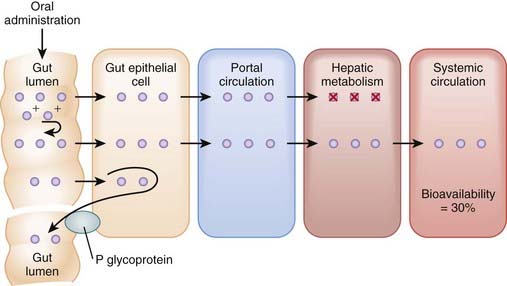

Bioavailability will be influenced by any factors that impede the active drug from reaching the systemic circulation (Figure 2-3). These include diffusion across physiologic barriers, the effect of transporters that prevent accumulation of drug in the blood, and metabolism of the drug before it reaches the systemic circulation. For example, after oral administration, a drug may have low bioavailability if:

The drug is actively transported from the epithelial cell cytoplasm back into the gut lumen by drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein (e.g., cyclosporine).

The drug is actively transported from the epithelial cell cytoplasm back into the gut lumen by drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein (e.g., cyclosporine).Routes of Administration

Enteral Administration

Oral (PO) administration is the most frequently used route of administration because of its simplicity and convenience, which improve patient compliance. Bioavailability of drugs administered orally varies greatly. This route is effective for drugs with moderate to high oral bioavailability and for drugs of varying pKa because gut pH varies considerably along the length of the GI tract. Administration via this route is less desirable for drugs that are irritating to the GI tract or when the patient is vomiting or unable to swallow. Drugs given orally must be acid stable or protected from gastric acid (e.g., by enteric coatings). Additional factors influencing absorption of orally administered drugs include the following:

Oral (PO) administration is the most frequently used route of administration because of its simplicity and convenience, which improve patient compliance. Bioavailability of drugs administered orally varies greatly. This route is effective for drugs with moderate to high oral bioavailability and for drugs of varying pKa because gut pH varies considerably along the length of the GI tract. Administration via this route is less desirable for drugs that are irritating to the GI tract or when the patient is vomiting or unable to swallow. Drugs given orally must be acid stable or protected from gastric acid (e.g., by enteric coatings). Additional factors influencing absorption of orally administered drugs include the following:

Gastric emptying time. For most drugs the greatest absorption occurs in the small intestine owing to its large surface. More rapid gastric emptying facilitates their absorption because the drug is delivered to the small intestine more quickly. Conversely, factors that slow gastric emptying (e.g., food, anticholinergic drugs) generally slow absorption.

Gastric emptying time. For most drugs the greatest absorption occurs in the small intestine owing to its large surface. More rapid gastric emptying facilitates their absorption because the drug is delivered to the small intestine more quickly. Conversely, factors that slow gastric emptying (e.g., food, anticholinergic drugs) generally slow absorption. Intestinal motility. Increases in intestinal motility (e.g., diarrhea) may move drugs through the intestine too rapidly to permit effective absorption.

Intestinal motility. Increases in intestinal motility (e.g., diarrhea) may move drugs through the intestine too rapidly to permit effective absorption. Food. In addition to affecting gastric emptying time, food may reduce the absorption of some drugs (e.g., tetracycline) owing to physical interactions with the drug (e.g., chelation). Alternatively, absorption of some drugs (e.g., clarithromycin) is improved by administration with food.

Food. In addition to affecting gastric emptying time, food may reduce the absorption of some drugs (e.g., tetracycline) owing to physical interactions with the drug (e.g., chelation). Alternatively, absorption of some drugs (e.g., clarithromycin) is improved by administration with food. Rectal administration via suppositories to produce a systemic effect is useful in situations in which the patient is unable to take medication orally (e.g., is unconscious, vomiting, convulsing). Drugs are absorbed through the rectal mucosa. Because of the anatomy of the venous drainage of the rectum, approximately 50% of the dose bypasses the portal circulation, which is an advantage if the drug has low oral bioavailability. On the other hand, drug absorption via this route is incomplete and erratic, in part because of variability in drug dissociation from the suppository. Rectal administration is also used for local topical effects (e.g., antiinflammatory drugs in the treatment of colitis).

Rectal administration via suppositories to produce a systemic effect is useful in situations in which the patient is unable to take medication orally (e.g., is unconscious, vomiting, convulsing). Drugs are absorbed through the rectal mucosa. Because of the anatomy of the venous drainage of the rectum, approximately 50% of the dose bypasses the portal circulation, which is an advantage if the drug has low oral bioavailability. On the other hand, drug absorption via this route is incomplete and erratic, in part because of variability in drug dissociation from the suppository. Rectal administration is also used for local topical effects (e.g., antiinflammatory drugs in the treatment of colitis). Sublingual (under the tongue) or buccal (between gum and cheek) administration is advantageous for drugs that have low oral availability because venous drainage from the mouth bypasses the liver. Drugs must be lipophilic and are absorbed rapidly. Buccal formulations can provide extended-release options to provide long-lasting effects.

Sublingual (under the tongue) or buccal (between gum and cheek) administration is advantageous for drugs that have low oral availability because venous drainage from the mouth bypasses the liver. Drugs must be lipophilic and are absorbed rapidly. Buccal formulations can provide extended-release options to provide long-lasting effects.Parenteral Administration

IV administration is the most reliable method for delivering drug to the systemic circulation because it bypasses many of the absorption barriers, efflux pumps, and metabolic mechanisms. In fact, by definition, bioavailability of drugs is 100% by IV injection because the drug is administered directly into the vascular space. It is also one of the preferred routes of administration to rapidly achieve therapeutically effective drug concentrations. IV infusions may be used to achieve a constant level of drug in the bloodstream. Drugs must be in aqueous solution or very fine suspensions to avoid the possibility of embolism. Caution must be used with drugs or drug combinations with the propensity to form precipitates.

IV administration is the most reliable method for delivering drug to the systemic circulation because it bypasses many of the absorption barriers, efflux pumps, and metabolic mechanisms. In fact, by definition, bioavailability of drugs is 100% by IV injection because the drug is administered directly into the vascular space. It is also one of the preferred routes of administration to rapidly achieve therapeutically effective drug concentrations. IV infusions may be used to achieve a constant level of drug in the bloodstream. Drugs must be in aqueous solution or very fine suspensions to avoid the possibility of embolism. Caution must be used with drugs or drug combinations with the propensity to form precipitates. IM administration of drugs in aqueous solution results in rapid absorption of drug in most cases. Drug absorption is dependent on muscle blood flow and thus is influenced by factors that alter blood flow to the muscle (e.g., exercise). It is also possible to achieve a slower, more constant absorption and effect of drug by altering the drug vehicle. Depot IM injections use drug formulation to slowly release drug at the site of injection.

IM administration of drugs in aqueous solution results in rapid absorption of drug in most cases. Drug absorption is dependent on muscle blood flow and thus is influenced by factors that alter blood flow to the muscle (e.g., exercise). It is also possible to achieve a slower, more constant absorption and effect of drug by altering the drug vehicle. Depot IM injections use drug formulation to slowly release drug at the site of injection. SC administration is used for drugs that have low oral bioavailability (e.g., insulin). In addition, the rate of absorption can be manipulated by using different formulations of the drug (e.g., fast-acting versus slow-acting insulin preparations). This route is not appropriate for solutions that are irritating to tissue because these may produce necrosis and sloughing of the skin.

SC administration is used for drugs that have low oral bioavailability (e.g., insulin). In addition, the rate of absorption can be manipulated by using different formulations of the drug (e.g., fast-acting versus slow-acting insulin preparations). This route is not appropriate for solutions that are irritating to tissue because these may produce necrosis and sloughing of the skin. Transdermal administration is administration through the skin. The drug must be highly lipophilic. Drugs may be applied as ointments or in special matrices (e.g., transdermal patches). Absorption via this route is slow but conducive to producing long-lasting effects. Special slow-release matrices in some transdermal patches can maintain steady drug concentrations that approach those of constant IV infusion.

Transdermal administration is administration through the skin. The drug must be highly lipophilic. Drugs may be applied as ointments or in special matrices (e.g., transdermal patches). Absorption via this route is slow but conducive to producing long-lasting effects. Special slow-release matrices in some transdermal patches can maintain steady drug concentrations that approach those of constant IV infusion. Inhalational administration can be used. The lungs serve as an effective route of administration of drugs. The pulmonary alveoli represent a large surface and a minimal barrier to diffusion. The lungs also receive the total cardiac output as blood flow. Thus, absorption from the lungs can be very rapid and complete. Drugs must be nonirritating and gaseous or very fine aerosols. The intended effects may be systemic (e.g., inhaled general anesthetics) or local (e.g., bronchodilators in the treatment of asthma).

Inhalational administration can be used. The lungs serve as an effective route of administration of drugs. The pulmonary alveoli represent a large surface and a minimal barrier to diffusion. The lungs also receive the total cardiac output as blood flow. Thus, absorption from the lungs can be very rapid and complete. Drugs must be nonirritating and gaseous or very fine aerosols. The intended effects may be systemic (e.g., inhaled general anesthetics) or local (e.g., bronchodilators in the treatment of asthma). Topical administration involves application of the drug primarily to elicit local effects at the site of application and to avoid systemic effects. Examples include drugs administered to the eye, the nasal mucosa, or the skin. Generally drugs are formulated to be less lipophilic to reduce systemic absorption.

Topical administration involves application of the drug primarily to elicit local effects at the site of application and to avoid systemic effects. Examples include drugs administered to the eye, the nasal mucosa, or the skin. Generally drugs are formulated to be less lipophilic to reduce systemic absorption. Intrathecal administration penetrates the subarachnoid space to allow access of the drug to the cerebrospinal fluid of the spinal cord. This approach is used to circumvent the blood-brain barrier. Intrathecal administration is used to produce spinal anesthesia and in pain management and, in select cases, to administer cancer therapy.

Intrathecal administration penetrates the subarachnoid space to allow access of the drug to the cerebrospinal fluid of the spinal cord. This approach is used to circumvent the blood-brain barrier. Intrathecal administration is used to produce spinal anesthesia and in pain management and, in select cases, to administer cancer therapy.Drug Distribution

Initial Drug Distribution

Drug Redistribution

After the initial distribution to high–blood flow tissues, drugs redistribute to those tissues for which they have affinity.

After the initial distribution to high–blood flow tissues, drugs redistribute to those tissues for which they have affinity. Drugs may sequester in tissues for which they have affinity. These tissues may then act as a sink for the drug and increase its apparent volume of distribution (see later). In addition, as plasma concentrations of drug fall, the tissue releases drug back into the circulation, thus prolonging the duration of action of the drug.

Drugs may sequester in tissues for which they have affinity. These tissues may then act as a sink for the drug and increase its apparent volume of distribution (see later). In addition, as plasma concentrations of drug fall, the tissue releases drug back into the circulation, thus prolonging the duration of action of the drug.Effect of Drug Binding on Distribution

Plasma Protein Binding

Plasma proteins, such as albumin, α-glycoprotein, and steroid hormone binding globulins, exhibit affinity for a number of drugs.

Plasma proteins, such as albumin, α-glycoprotein, and steroid hormone binding globulins, exhibit affinity for a number of drugs. Binding to plasma protein is generally reversible and determined by the concentration of drug, the affinity of the protein for the drug, and the number of binding sites available.

Binding to plasma protein is generally reversible and determined by the concentration of drug, the affinity of the protein for the drug, and the number of binding sites available. Only free drug in the plasma is able to diffuse to its molecular site of action. Thus plasma protein binding can greatly reduce the concentration of drug at the sites of action and necessitate larger doses.

Only free drug in the plasma is able to diffuse to its molecular site of action. Thus plasma protein binding can greatly reduce the concentration of drug at the sites of action and necessitate larger doses.Volume of Distribution

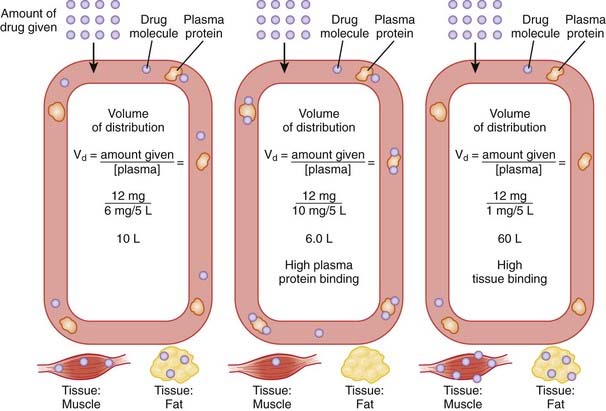

The volume of distribution represents the theoretical volume in liters (therefore also called apparent volume of distribution) into which a drug is dissolved to produce the plasma concentration observed at steady state. Volume of distribution is calculated as the quotient of the amount of drug administered and the steady state plasma concentration (Figure 2-4).

Vd is largely determined by the chemical characteristic of the drug and its ability to interact with various tissue compartments.

Vd is largely determined by the chemical characteristic of the drug and its ability to interact with various tissue compartments.

Drugs that bind extensively to plasma proteins generally have a relatively small volume of distribution (e.g., 7 to 8 L) because these drugs will be highly restricted to the plasma.

Drugs that bind extensively to plasma proteins generally have a relatively small volume of distribution (e.g., 7 to 8 L) because these drugs will be highly restricted to the plasma. Changes in Vd influence drug plasma concentrations and may necessitate changes in dosage or result in toxicity. For example, loss of skeletal muscle mass with aging or disease (heart failure) requires a reduction in the dose of digoxin, a drug that is highly bound to skeletal muscle protein. The dose of digoxin is often adjusted to lean body mass.

Changes in Vd influence drug plasma concentrations and may necessitate changes in dosage or result in toxicity. For example, loss of skeletal muscle mass with aging or disease (heart failure) requires a reduction in the dose of digoxin, a drug that is highly bound to skeletal muscle protein. The dose of digoxin is often adjusted to lean body mass.Drug Elimination

Biotransformation (Metabolism)

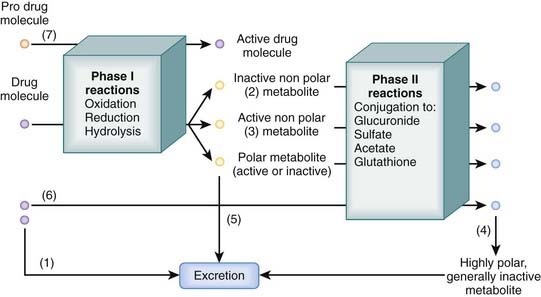

Many drugs are lipophilic molecules that resist excretion via the kidney or gut because they can readily diffuse back into the circulation. Biotransformation is an essential step in eliminating these drugs by converting them to more polar water-soluble compounds. There are several different biotransformation pathways that drug molecules may follow (Figure 2-5). Biotransformation:

May convert drugs to active metabolites that may have the same or different beneficial actions as the parent drug

May convert drugs to active metabolites that may have the same or different beneficial actions as the parent drug Occurs in many tissues including the kidney, gut, and lungs, but for most drugs the liver is the major site of biotransformation

Occurs in many tissues including the kidney, gut, and lungs, but for most drugs the liver is the major site of biotransformationTwo major processes contribute to biotransformation of drugs.

Phase I Reactions

Phase I reactions are also called oxidation-reduction reactions or handle reactions.

These reactions uncover or add a reactive group to the drug molecule through oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis.

These reactions uncover or add a reactive group to the drug molecule through oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis. They make the drug molecule more polar and more reactive, which facilitates excretion or further biotransformation of the drug through phase II reactions.

They make the drug molecule more polar and more reactive, which facilitates excretion or further biotransformation of the drug through phase II reactions.Oxidation

Oxidation accounts for a large proportion of drug metabolism.

It is mediated primarily by mixed function oxygenases (monooxygenases; microsomal mixed function oxidases) located in endoplasmic reticulum, which include the following:

It is mediated primarily by mixed function oxygenases (monooxygenases; microsomal mixed function oxidases) located in endoplasmic reticulum, which include the following:

The cytochrome P-450 family accounts for over 80% of drug oxidation. In this group of enzymes:

The cytochrome P-450 family accounts for over 80% of drug oxidation. In this group of enzymes:

CYPs are not substrate selective, meaning that many different drugs may be metabolized by one or more CYP isoforms, although there is generally one isoform that accounts for the majority of a given drug’s biotransformation.

CYPs are not substrate selective, meaning that many different drugs may be metabolized by one or more CYP isoforms, although there is generally one isoform that accounts for the majority of a given drug’s biotransformation. Interaction at CYPs is an important pharmacokinetic mechanism that can affect clinical use of drugs. Knowledge of CYP isoforms involved in metabolism of drugs and the type of interaction can guide clinical selection of drugs and explain adverse drug interactions. Interactions may take the form of competition, inhibition, or induction.

Interaction at CYPs is an important pharmacokinetic mechanism that can affect clinical use of drugs. Knowledge of CYP isoforms involved in metabolism of drugs and the type of interaction can guide clinical selection of drugs and explain adverse drug interactions. Interactions may take the form of competition, inhibition, or induction.

Generally increase plasma concentrations of substrate drugs, drug effect, and potentially drug toxicity

Generally increase plasma concentrations of substrate drugs, drug effect, and potentially drug toxicity Examples of clinically important CYP isoforms include the following:

Examples of clinically important CYP isoforms include the following:

CYP2D6

CYP2D6

Phase II Reactions

Phase II reactions are also called conjugation reactions.

These reactions add a polar group, such as glucuronide, glutathione, acetate, or sulfate, to the drug molecule.

These reactions add a polar group, such as glucuronide, glutathione, acetate, or sulfate, to the drug molecule. Generally they inactivate the drug but in some cases can produce active metabolites (e.g., conversion of procainamide to N-acetylprocainamide).

Generally they inactivate the drug but in some cases can produce active metabolites (e.g., conversion of procainamide to N-acetylprocainamide). Conjugation reactions can occur:

Conjugation reactions can occur:

With a reactive intermediate generated by phase I reactions. In this case, conjugation reactions may play an important role in neutralizing reactive intermediates. For example, phase I metabolism of acetaminophen generates a reactive intermediate capable of producing liver damage. Generally, liver damage does not occur because the reactive intermediate is rapidly conjugated to glutathione. However, under conditions in which cellular glutathione levels are depleted or excessive doses of acetaminophen lead to such high levels of reactive intermediate that glutathione conjugation is overwhelmed, acetaminophen will cause liver damage.

With a reactive intermediate generated by phase I reactions. In this case, conjugation reactions may play an important role in neutralizing reactive intermediates. For example, phase I metabolism of acetaminophen generates a reactive intermediate capable of producing liver damage. Generally, liver damage does not occur because the reactive intermediate is rapidly conjugated to glutathione. However, under conditions in which cellular glutathione levels are depleted or excessive doses of acetaminophen lead to such high levels of reactive intermediate that glutathione conjugation is overwhelmed, acetaminophen will cause liver damage. Phase II reactions are also subject to genetic polymorphisms. Acetylation capacity is an important polymorphism. Approximately 40% to 50% of the population exhibits slow acetylation capacity (slow acetylators). In these patients, drugs that are biotransformed through acetylation (e.g., hydralazine, isoniazid, procainamide) exhibit slowed metabolism. Dosages of such drugs must be adjusted downward to account for slowed biotransformation in affected patients.

Phase II reactions are also subject to genetic polymorphisms. Acetylation capacity is an important polymorphism. Approximately 40% to 50% of the population exhibits slow acetylation capacity (slow acetylators). In these patients, drugs that are biotransformed through acetylation (e.g., hydralazine, isoniazid, procainamide) exhibit slowed metabolism. Dosages of such drugs must be adjusted downward to account for slowed biotransformation in affected patients.Drug Excretion

Renal Excretion

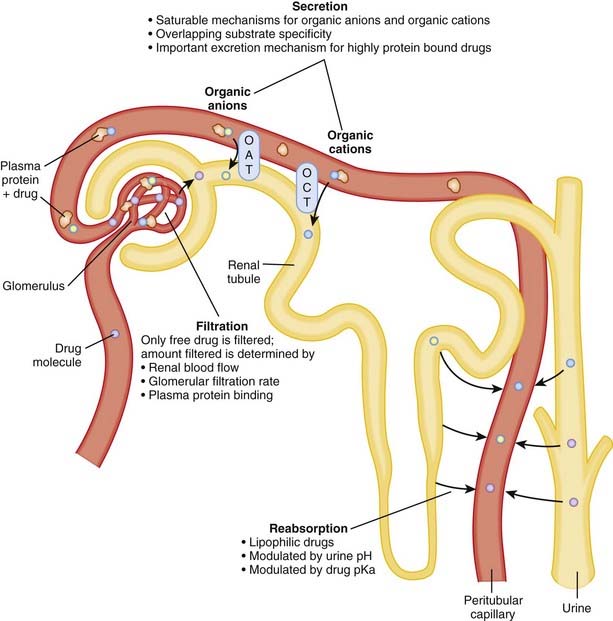

Renal excretion is quantitatively the most important route of excretion for most drugs and drug metabolites. Renal excretion involves three processes: glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and/or tubular reabsorption (Figure 2-6). The sum of these processes determines the extent of net renal drug excretion.

Glomerular filtration

Glomerular filtration

The kidney filters approximately 180 L of fluid per day; thus there is a large capacity for drug excretion via this route.

The kidney filters approximately 180 L of fluid per day; thus there is a large capacity for drug excretion via this route. The glomerular barrier restricts passage of plasma proteins, red blood cells, and other large blood constituents. Accordingly, drugs that are bound to these blood elements will not be effectively filtered.

The glomerular barrier restricts passage of plasma proteins, red blood cells, and other large blood constituents. Accordingly, drugs that are bound to these blood elements will not be effectively filtered. Factors influencing the amount of drug excreted by filtration include the following:

Factors influencing the amount of drug excreted by filtration include the following:

Tubular secretion

Tubular secretion

Secretory mechanisms in the renal tubules actively transport endogenous substances and drug molecules from the plasma in peritubular capillaries to the tubular lumen.

Secretory mechanisms in the renal tubules actively transport endogenous substances and drug molecules from the plasma in peritubular capillaries to the tubular lumen. Although quite diverse in some characteristics, the tubular transporters can be classified into two major groups: the organic anion transporter (OAT) and the organic cation transporter (OCT) families.

Although quite diverse in some characteristics, the tubular transporters can be classified into two major groups: the organic anion transporter (OAT) and the organic cation transporter (OCT) families. Members of the OAT and OCT families belong to the larger superfamilies of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters and the solute carrier proteins (SLCs).

Members of the OAT and OCT families belong to the larger superfamilies of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters and the solute carrier proteins (SLCs). Tubular transporters exhibit:

Tubular transporters exhibit:

Tubular secretion is:

Tubular secretion is:

Tubular reabsorption

Tubular reabsorption

Once in the renal tubule, the nonionized form of the drug is able to diffuse across the tubular membrane and reenter the plasma.

Once in the renal tubule, the nonionized form of the drug is able to diffuse across the tubular membrane and reenter the plasma. As water is reabsorbed along the renal tubule the tubular drug concentration increases, providing a concentration gradient favoring drug reabsorption.

As water is reabsorbed along the renal tubule the tubular drug concentration increases, providing a concentration gradient favoring drug reabsorption. Manipulation of the pH of the tubular fluid can be used to enhance or inhibit tubular reabsorption according to the Henderson-Hasselbalch relationship. Acidification of urine can be used to decrease reabsorption of weak bases by increasing the proportion of drug in the ionized form. Conversely, alkalinization of urine can be used to increase the renal excretion of acidic drugs because a greater proportion of the drug is in the ionized form.

Manipulation of the pH of the tubular fluid can be used to enhance or inhibit tubular reabsorption according to the Henderson-Hasselbalch relationship. Acidification of urine can be used to decrease reabsorption of weak bases by increasing the proportion of drug in the ionized form. Conversely, alkalinization of urine can be used to increase the renal excretion of acidic drugs because a greater proportion of the drug is in the ionized form.Clinical Pharmacokinetics

Plasma Concentration Curves

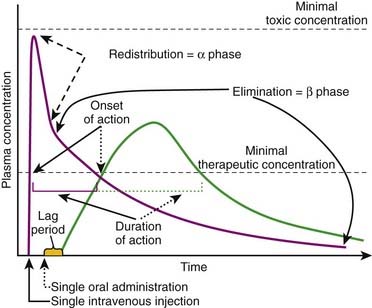

Plasma concentration curves depict the plasma concentration of drugs over time (Figure 2-7). These curves are useful in illustrating several important principles. Although the different phases of the plasma drug profile will be discussed sequentially, it is important to note that the processes of absorption, distribution, and elimination occur simultaneously. As soon as a drug reaches the systemic circulation (absorption), it is also being distributed and eliminated.

Plasma concentrations that exceed the minimally therapeutic concentration will exert a pharmacologic effect. The point at which plasma concentrations exceed this level represents the onset of action of the drug. The duration of action of the drug is the time over which the plasma concentrations exceed the minimally therapeutic concentration. Plasma concentrations that exceed the minimally toxic concentration will produce toxic effects. An important goal of pharmacotherapy is to maintain plasma concentrations between the minimally therapeutic and minimally toxic concentrations.

Plasma concentrations that exceed the minimally therapeutic concentration will exert a pharmacologic effect. The point at which plasma concentrations exceed this level represents the onset of action of the drug. The duration of action of the drug is the time over which the plasma concentrations exceed the minimally therapeutic concentration. Plasma concentrations that exceed the minimally toxic concentration will produce toxic effects. An important goal of pharmacotherapy is to maintain plasma concentrations between the minimally therapeutic and minimally toxic concentrations. IV administration delivers drug directly to the systemic circulation. If given as a single bolus injection, drugs will reach their peak concentration immediately. Subsequently, plasma concentrations will decrease rapidly as drug is distributed to various tissues. This is the so-called alpha (α) or redistribution phase. The plasma concentration profile then enters a phase of slower monoexponential decay that reflects predominantly elimination of the drug and is called the beta (β) or elimination phase. Plasma sampling for drug-monitoring purposes is generally performed in the β phase, because plasma concentrations in this stage are deemed to be representative of the drug concentrations at the site of action.

IV administration delivers drug directly to the systemic circulation. If given as a single bolus injection, drugs will reach their peak concentration immediately. Subsequently, plasma concentrations will decrease rapidly as drug is distributed to various tissues. This is the so-called alpha (α) or redistribution phase. The plasma concentration profile then enters a phase of slower monoexponential decay that reflects predominantly elimination of the drug and is called the beta (β) or elimination phase. Plasma sampling for drug-monitoring purposes is generally performed in the β phase, because plasma concentrations in this stage are deemed to be representative of the drug concentrations at the site of action. Oral or other nonvascular routes of administration result in a delayed peak plasma concentration.

Oral or other nonvascular routes of administration result in a delayed peak plasma concentration.

The Drug Elimination or β Phase

Elimination Kinetics

First-Order Kinetics

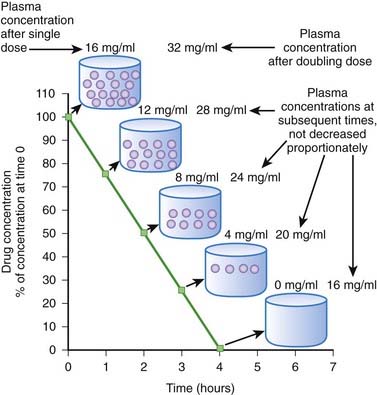

When drug elimination proceeds by first-order kinetics, a constant proportion or fraction of drug is eliminated per unit time (e.g., 25%/hr). As a result, plasma drug concentrations decline exponentially. This occurs because the elimination mechanisms adjust their activity to the prevailing drug concentration. When drug concentrations increase, elimination mechanisms can accept more drug. Conversely, when plasma concentrations decline, the elimination mechanisms process less drug. Important: as long as elimination proceeds by first-order kinetics the fraction of drug eliminated per unit time remains constant regardless of the starting concentration. An example is shown in Figure 2-8. In this example 50% of the drug is eliminated in 1 hour. One hour after the peak concentration of 16 mg/mL, the drug concentration is 8 mg/mL. After 1 additional hour, the plasma concentration has been reduced to 50% of 8 mg/mL, and so on for each additional hour. An important feature of first-order kinetics is that the proportion of drug eliminated is independent of the starting concentration. If the dose of drug was doubled and peak concentration reached 32 mg/mL, 50% of the drug would still be eliminated each hour. The constant proportionality of first-order elimination allows relatively accurate prediction of plasma concentrations over time. Doubling of the dose results in a doubling of plasma concentrations at any time point. As a result, for drugs that are eliminated by first-order kinetics:

Zero-Order Kinetics

Zero-order kinetics is also called saturation kinetics. In this case, elimination mechanisms become saturated and unable to process more drug when drug concentrations rise. Consequently, for drugs that are eliminated by zero-order kinetics, a constant amount of drug is eliminated per unit time (e.g., 5 mg/hr) regardless of drug plasma concentration. Plasma concentrations decline in linear fashion (Figure 2-9). As a result, a progressively smaller proportion of drug is eliminated as plasma concentrations increase. In other words, the proportion of drug eliminated depends on the starting concentration. Zero-order kinetics makes prediction of drug concentrations over time problematic. In the example shown in Figure 2-9, 4 mg/mL of drug is eliminated per hour. In the case of a dose that produced a starting concentration of 16 mg/mL, plasma concentrations will have declined to 4 mg/mL in 3 hours. However if the dose is doubled to achieve initial plasma concentrations of 32 mg/mL, after 3 hours plasma concentrations would be 20 mg/mL or 5 times higher than the lower dose at a comparable time, a much greater level than we would have predicted by doubling the dose. Thus, the effects of changing dosage can be quite unpredictable for drugs that are eliminated by zero-order kinetics. For drugs that are eliminated by zero-order kinetics:

The time to completely eliminate the drug is dependent on dose. This make repetitive administration complicated.

The time to completely eliminate the drug is dependent on dose. This make repetitive administration complicated. Increasing dose or frequency of administration can produce unpredictable increases in plasma concentrations.

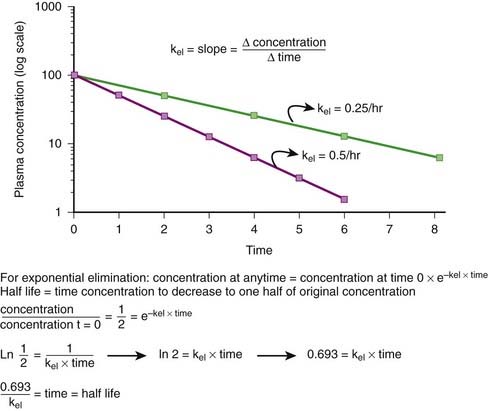

Increasing dose or frequency of administration can produce unpredictable increases in plasma concentrations.The majority of drugs are eliminated by first-order kinetics. For drugs that exhibit first-order kinetics, the β phase is used to obtain several important parameters (Figure 2-10).

Elimination Rate Constant (kel, ke)

First-order kinetics dictate that plasma concentrations fall exponentially during the elimination phase. It is typical to plot these data on a semilogarithmic scale to linearize the plasma concentration time curve. The slope of this curve is the elimination rate constant (kel). The elimination rate constant describes the fraction of drug eliminated per unit of time or the rate at which plasma concentrations will decline during the elimination phase. For example (see Figure 2-10), if 25% of a drug were eliminated per hour, then kel would be 0.25/hr. The value for kel is estimated as the slope of the elimination phase of the plasma concentration curve. Note that kel is independent of the dose or starting concentration for drugs that follow first-order kinetics. As long as elimination mechanisms are not saturated, in our example, 25% of the starting concentration will be eliminated per hour whether the starting concentration (dose) is 10 units or 100 units. The elimination rate constant (proportion per unit time) can be used to calculate the time necessary to eliminate a certain proportion of drug (inverse of rate constant). Clinically, a very useful time interval is the time necessary to reduce drug concentration by one half—in other words, the half-life.

Half-life (t1/2) is the time for plasma concentrations to decline to one half their starting value. Half-life is calculated as:

Half-life (t1/2) is the time for plasma concentrations to decline to one half their starting value. Half-life is calculated as:

where 0.693 is a constant derived from the natural log (ln) (because the decay is exponential for first-order kinetics) of the ratio of drug concentration at the beginning and end of one half-life, which by definition is 2 (100%/50%) (ln 2 = 0.693).

Thus the half-life is inversely related to the elimination rate constant because t1/2 estimates the time needed to eliminate a specific proportion (50%) of drug. This makes the t1/2 a very useful parameter that can be used to estimate the:

Thus the half-life is inversely related to the elimination rate constant because t1/2 estimates the time needed to eliminate a specific proportion (50%) of drug. This makes the t1/2 a very useful parameter that can be used to estimate the:

Time for the drug to be completely eliminated from the body. Four to five half-lives are necessary to reduce drug concentration by 95% to 97%.

Time for the drug to be completely eliminated from the body. Four to five half-lives are necessary to reduce drug concentration by 95% to 97%. Duration of action of the drug. The longer the half-life of the drug, the longer the plasma concentration of the drug will remain above the minimally effective concentration.

Duration of action of the drug. The longer the half-life of the drug, the longer the plasma concentration of the drug will remain above the minimally effective concentration. Because the half-life is derived from the kel, half-life is also independent of dosage, as long as the drug is eliminated by first-order kinetics. In contrast, for drugs that exhibit zero-order kinetics (saturable elimination), half-life generally increases with dosage because a constant amount (not proportion) of drug is eliminated.

Because the half-life is derived from the kel, half-life is also independent of dosage, as long as the drug is eliminated by first-order kinetics. In contrast, for drugs that exhibit zero-order kinetics (saturable elimination), half-life generally increases with dosage because a constant amount (not proportion) of drug is eliminated.Clearance

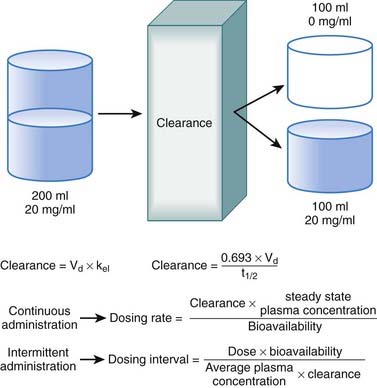

Clearance is another index of the ability of the body to eliminate drug. Rather than describing the amount of drug eliminated, clearance describes the volume of plasma from which drug would be totally removed per unit time. Clearance can be visualized as the circulation consisting of units or packets of blood containing a given concentration of drug. Clearance removes all of the drug from a certain unit of plasma in a given period of time (Figure 2-11). Although somewhat difficult conceptually, clearance is very valuable practically. Having an idea of how much plasma is cleared of drug over time allows estimation of how much drug must be given to maintain a constant plasma concentration.

Clearance is expressed in units of volume and time (e.g., milliliters per minute). Because clearance is removal of drug from the circulation, clearance is related to the elimination rate constant and the apparent volume into which the drug is dissolved:

Clearance is expressed in units of volume and time (e.g., milliliters per minute). Because clearance is removal of drug from the circulation, clearance is related to the elimination rate constant and the apparent volume into which the drug is dissolved:

Clearance is inversely related to half-life. Intuitively, the higher the clearance, the shorter the half-life and vice versa. Mathematically, clearance can be determined as follows:

Clearance is inversely related to half-life. Intuitively, the higher the clearance, the shorter the half-life and vice versa. Mathematically, clearance can be determined as follows:

Clearance can be used to calculate the rate at which drug must be added to the circulation to maintain the steady state plasma concentration or, in other words, the dosage rate. If you know what is going out, you can administer the same amount going in, and theoretically the plasma concentration should remain constant.

Clearance can be used to calculate the rate at which drug must be added to the circulation to maintain the steady state plasma concentration or, in other words, the dosage rate. If you know what is going out, you can administer the same amount going in, and theoretically the plasma concentration should remain constant.Administration Protocols

Continuous Administration

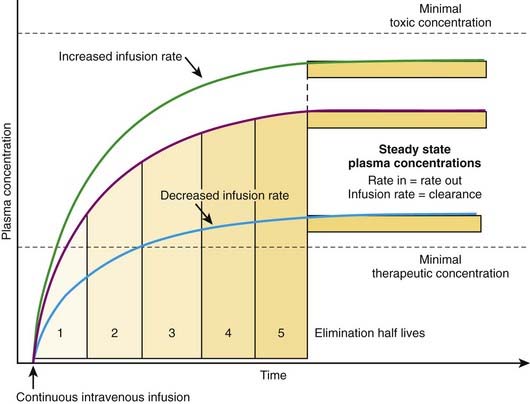

The most effective way to achieve a desired steady state drug concentration with minimal fluctuations is to administer the drug as a continuous infusion. Figure 2-12 illustrates that plasma drug concentrations begin to rise with the onset of an IV infusion because drug is continually delivered directly into the circulation. As plasma concentrations begin to increase with onset of the infusion, drug elimination will also begin to occur. Thus, simultaneously, drug is being added to the circulation and drug is being taken away. Plasma drug concentrations will continue to rise as long as the rate of drug delivery exceeds the rate of drug elimination until a point is reached at which the clearance of the drug from plasma is equal to the delivery of new drug into the plasma. At this point the rate of drug delivery equals the rate of elimination, and steady state has been achieved. This balance between drug in and drug out, or steady state, will be achieved in four to five half-lives. A change in the infusion rate will result in a change in the steady state plasma concentrations; however, the time to reach steady state will still be four to five half-lives. Plasma drug concentrations will remain stable unless the rate of infusion or the clearance is altered in some way (e.g., by induction of metabolic enzymes).

For direct administration into the circulation (e.g., IV route), the dosing rate is calculated as follows:

For direct administration into the circulation (e.g., IV route), the dosing rate is calculated as follows:

Intermittent Administration

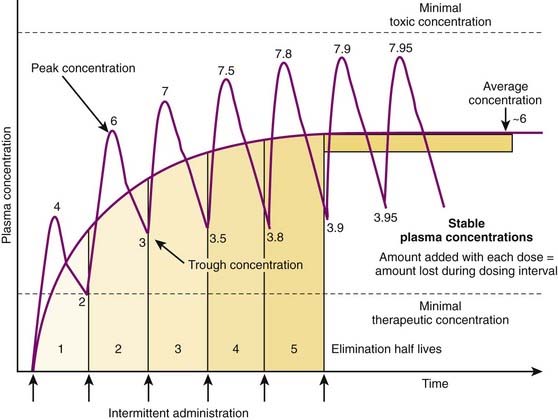

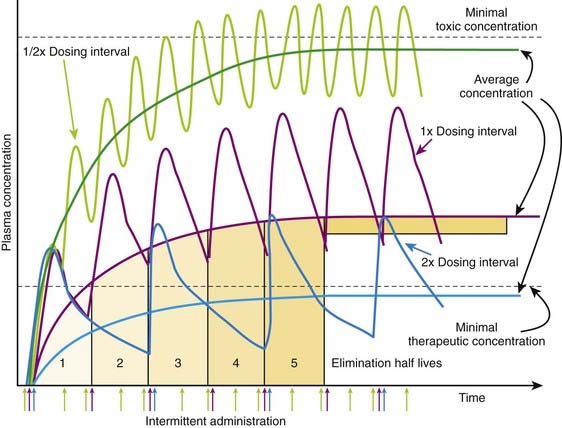

Although there are many examples in which continuous administration of drug is practiced, drugs are usually administered on an intermittent basis. Intermittent administration will result in much greater fluctuations in plasma drug concentrations. Plasma concentrations will rise in the absorptive phase to reach a peak and then decrease in the redistribution and elimination phases to reach a trough concentration until the next dose is given (Figure 2-13). In keeping with the general principle discussed earlier, stable average plasma drug concentrations will be reached when the amount of drug added in the next dose equals the amount eliminated during the interval between doses. For drugs that obey first-order kinetics, stable average drug concentrations will be achieved in 4 to 5 half-lives. Thus, the clinician must estimate a dose and administration interval to attain the desired steady state concentration of drug while once again minimizing the fluctuations in drug concentrations to avoid potential toxicity or lack of efficacy. An additional factor to consider is patient compliance. It would be possible to closely approximate a continuous infusion and very steady plasma concentrations using very small doses administered very frequently. However, most patients would not readily accept such a regimen. Thus dosage schedules should also be designed to provide convenient intervals to promote patient compliance. For intermittent dosage regimens:

The plasma concentration of drug is constantly changing, rising to a peak value sometime after absorption and falling to a trough value immediately before the next dose.

The plasma concentration of drug is constantly changing, rising to a peak value sometime after absorption and falling to a trough value immediately before the next dose. Accordingly, steady state concentrations are never truly achieved. Instead an average drug concentration between the peak and trough concentration is achieved.

Accordingly, steady state concentrations are never truly achieved. Instead an average drug concentration between the peak and trough concentration is achieved. Average drug concentrations will be determined by the size of the dose, the time between each dose (dosage interval), the bioavailability, and the clearance of the drug.

Average drug concentrations will be determined by the size of the dose, the time between each dose (dosage interval), the bioavailability, and the clearance of the drug.

Intuitively, as bioavailability and dose increase, so should the average concentration of drug in the plasma. Conversely as the interval between doses increases, the average concentration should decrease. Similarly, as clearance of drug increases, for any given dose and dosage interval, the average concentration should decrease.

Intuitively, as bioavailability and dose increase, so should the average concentration of drug in the plasma. Conversely as the interval between doses increases, the average concentration should decrease. Similarly, as clearance of drug increases, for any given dose and dosage interval, the average concentration should decrease. In many cases, only a limited number of dosage strengths are available based on what is manufactured (only certain strengths of tablets are available). Thus, the clinician can adjust the dosage interval. Rearranging the previous equation, the dosage interval can be calculated as follows:

In many cases, only a limited number of dosage strengths are available based on what is manufactured (only certain strengths of tablets are available). Thus, the clinician can adjust the dosage interval. Rearranging the previous equation, the dosage interval can be calculated as follows:

It is important to note that dose and dosage interval, the two variables most readily controlled by the physician, will affect the average drug concentration in the plasma and therefore the time to reach a therapeutic concentration. However, dose and dosage interval do not affect the time to reach a stable average concentration.

It is important to note that dose and dosage interval, the two variables most readily controlled by the physician, will affect the average drug concentration in the plasma and therefore the time to reach a therapeutic concentration. However, dose and dosage interval do not affect the time to reach a stable average concentration. The time to reach a stable average concentration will be determined by clearance and half-life. As described earlier, 4 to 5 half-lives will be required to reach a stable average drug concentration regardless of the dose or dosage interval. In practice:

The time to reach a stable average concentration will be determined by clearance and half-life. As described earlier, 4 to 5 half-lives will be required to reach a stable average drug concentration regardless of the dose or dosage interval. In practice:

For a drug with a t1/2 of 5 hours, stable average plasma concentrations will be obtained in about a day (20 to 25 hours).

For a drug with a t1/2 of 5 hours, stable average plasma concentrations will be obtained in about a day (20 to 25 hours). Administering a drug at a dosage interval equal to the drug’s t1/2 will result in peak drug concentration of approximately twice that of trough concentrations, or a twofold variation of concentrations between doses. Unless the drug has a low therapeutic index, this is generally an acceptable fluctuation in drug concentrations.

Administering a drug at a dosage interval equal to the drug’s t1/2 will result in peak drug concentration of approximately twice that of trough concentrations, or a twofold variation of concentrations between doses. Unless the drug has a low therapeutic index, this is generally an acceptable fluctuation in drug concentrations. Figure 2-14 illustrates the effect of altering dosage intervals on a drug that is eliminated by first-order kinetics. Note that in all cases the initial dose produces approximately equivalent plasma concentrations. However, plasma concentrations at subsequent doses differ greatly based on how much time is available for drug elimination during the dosage interval. Halving the dosage interval (purple curve) approximately doubles the average plasma concentration. Peak concentrations of drug exceed the minimal toxic concentrations and may be associated with adverse effects. Conversely, when the dosage interval is doubled (yellow curve), the peak concentrations initially exceed the minimal therapeutic concentrations but fall below that level during the dosage interval. The average plasma concentration also falls below therapeutic levels, and the drug is not effective. In both cases, the time to achieve stable average concentrations is approximately 4 to 5 half-lives.

Figure 2-14 illustrates the effect of altering dosage intervals on a drug that is eliminated by first-order kinetics. Note that in all cases the initial dose produces approximately equivalent plasma concentrations. However, plasma concentrations at subsequent doses differ greatly based on how much time is available for drug elimination during the dosage interval. Halving the dosage interval (purple curve) approximately doubles the average plasma concentration. Peak concentrations of drug exceed the minimal toxic concentrations and may be associated with adverse effects. Conversely, when the dosage interval is doubled (yellow curve), the peak concentrations initially exceed the minimal therapeutic concentrations but fall below that level during the dosage interval. The average plasma concentration also falls below therapeutic levels, and the drug is not effective. In both cases, the time to achieve stable average concentrations is approximately 4 to 5 half-lives. If the drug has a very high therapeutic index, much larger variations may be acceptable to allow longer dosage intervals. Some penicillin-like antibiotics have a very large therapeutic index but short half-lives (1 to 2 hours). A dosage interval near the half-life would clearly be inconvenient. Therefore very large doses of drug are given at dosage intervals that may be much greater than the half-life. In such cases the plasma concentrations peak at very high levels, and the majority of drug (>95%) is eliminated before the next dose. However, plasma concentrations remain above the minimal therapeutic concentrations for the better part of the dosage interval owing to the high initial concentrations. For example, ampicillin (half-life 1.8 hours) is given orally at dose of 500 mg, 4 times per day.

If the drug has a very high therapeutic index, much larger variations may be acceptable to allow longer dosage intervals. Some penicillin-like antibiotics have a very large therapeutic index but short half-lives (1 to 2 hours). A dosage interval near the half-life would clearly be inconvenient. Therefore very large doses of drug are given at dosage intervals that may be much greater than the half-life. In such cases the plasma concentrations peak at very high levels, and the majority of drug (>95%) is eliminated before the next dose. However, plasma concentrations remain above the minimal therapeutic concentrations for the better part of the dosage interval owing to the high initial concentrations. For example, ampicillin (half-life 1.8 hours) is given orally at dose of 500 mg, 4 times per day. If the drug has a very low therapeutic index, large variations in plasma concentrations could be dangerous. Therefore doses and dosage intervals are designed to maintain effective average concentrations with slight differences between peak and trough concentrations. This is generally achieved by using very short dosage intervals.

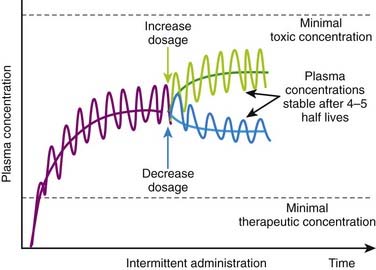

If the drug has a very low therapeutic index, large variations in plasma concentrations could be dangerous. Therefore doses and dosage intervals are designed to maintain effective average concentrations with slight differences between peak and trough concentrations. This is generally achieved by using very short dosage intervals. Basic pharmacokinetic principles can also predict the effect of changes in dosage or in dosage interval that occur during maintenance therapy. An increase or decrease in dosage will be associated with changes in peak, trough, and average plasma concentrations. An increase in dosage will cause peak concentrations to increase progressively with each dose until elimination mechanisms match the new increment in plasma concentrations at each administration. Conversely, with a reduction in dosage, trough concentration will progressively decrease until elimination matches the new, lower amount of drug added to the circulation at each administration. In both cases, peak, trough, and average plasma concentrations will stabilize over the course of 4 to 5 half-lives (Figure 2-15).

Basic pharmacokinetic principles can also predict the effect of changes in dosage or in dosage interval that occur during maintenance therapy. An increase or decrease in dosage will be associated with changes in peak, trough, and average plasma concentrations. An increase in dosage will cause peak concentrations to increase progressively with each dose until elimination mechanisms match the new increment in plasma concentrations at each administration. Conversely, with a reduction in dosage, trough concentration will progressively decrease until elimination matches the new, lower amount of drug added to the circulation at each administration. In both cases, peak, trough, and average plasma concentrations will stabilize over the course of 4 to 5 half-lives (Figure 2-15).Loading Doses

Loading doses are useful in emergency situations in which it is important to achieve a drug effect as soon as possible—for example, the administration of an anticonvulsant medication during a seizure. In these cases the drug would be given directly into the circulation to eliminate the time needed for absorption.

Loading doses are useful in emergency situations in which it is important to achieve a drug effect as soon as possible—for example, the administration of an anticonvulsant medication during a seizure. In these cases the drug would be given directly into the circulation to eliminate the time needed for absorption. Loading doses are also useful for drugs that have a very long half-life. In these cases the normal maintenance doses are generally small to avoid excessive accumulation of the drug. Consequently, plasma concentrations will rise very slowly on initiation of therapy. Therefore one or two larger loading doses may be given to increase plasma concentrations to therapeutic levels in a reasonable amount of time. These are then followed by the normal maintenance doses.

Loading doses are also useful for drugs that have a very long half-life. In these cases the normal maintenance doses are generally small to avoid excessive accumulation of the drug. Consequently, plasma concentrations will rise very slowly on initiation of therapy. Therefore one or two larger loading doses may be given to increase plasma concentrations to therapeutic levels in a reasonable amount of time. These are then followed by the normal maintenance doses. The primary determinants of the size of the loading dose are the volume of distribution and the desired plasma concentration. In addition, if the drug is not given directly into the circulation, the bioavailability of the drug must be accounted for. Accordingly,

The primary determinants of the size of the loading dose are the volume of distribution and the desired plasma concentration. In addition, if the drug is not given directly into the circulation, the bioavailability of the drug must be accounted for. Accordingly,