Chapter 24 Wilson disease

Wilson disease

Wilson disease is an inborn error of copper metabolism manifest as hepatic cirrhosis and basal ganglia damage (Wilson, 1912). Wilson disease is one of the few curable movement disorders at the present time. It presents in so many guises that any patient with a movement disorder under the age of 50 years should be considered to possibly have Wilson disease. It is sufficiently rare that the diagnosis is often missed. In a review of 307 patients, the average delay to diagnosis was 2 years and misdiagnoses included schizophrenia, juvenile polyarthritis, rheumatic chorea, nephrotic syndrome, metachromatic leukodystrophy, congenital myopathies, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, and neurodegenerative disease (Prashanth et al., 2004).

Wilson disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene responsible lies on chromosome 13q14.3 (whereas that for ceruloplasmin is located on chromosome 8 (Wang et al., 1988). The Wilson disease gene encodes for a copper-transporting P-type ATPase (ATP7B) (Petrukhin et al., 1993; Tanzi et al., 1993). Over 300 mutations of the gene have been detected, and more are being found regularly (Thomas et al., 1995; Shah et al., 1997; Curtis et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2010). The enzyme binds copper in its large N-terminal domain and aids in intracellular processing in the hepatocyte (Ala et al., 2007).

Intestinal absorption of copper is normal in Wilson disease (normal adults absorb about 1 mg of copper daily), as is subsequent transport into the hepatocyte. Since absorption is about 1 mg per day, and the requirement is for 0.75 mg per day, about 0.25 mg must be excreted from the body each day (Lorincz, 2010). There are two pathways for copper excretion from the hepatocyte aided by ATP7B. One is the attachment to ceruloplasmin in the Golgi apparatus, and subsequent delivery of the copper–ceruloplasmin complex into the serum. A second is promotion of copper excretion into the bile. The mutations lead to failure to excrete copper by both routes, causing build-up of copper in the hepatocyte and eventual spillover of free copper into the circulation. This leads to a substantial positive net copper balance and systemic copper poisoning (Cuthbert, 1998; Loudianos and Gitlin, 2000). There is increased circulating free copper and excessive urinary excretion of copper, but this is insufficient to prevent copper accumulation (the normal human body contains 80 mg of copper). Excess copper in the liver causes progressive liver damage. Copper also accumulates in brain and other sites (the eye, kidney, bones, and blood tissues being particularly vulnerable to copper toxicity). Some of the toxicity of copper may be due to oxidative mechanisms.

Curiously, monozygotic twins might be discordant for Wilson disease, suggesting that epigenetic or environmental factors must also be important (Czlonkowska et al., 2009).

The prevalence of heterozygous carriers, who have inherited only one abnormal gene, is around 1 in 100–200 of the population (Reilly et al., 1993). Heterozygotes do not develop Wilson disease, but may exhibit mild abnormalities of copper metabolism, and prevalence is estimated to be about 17 per million of the population.

The initial manifestations of the illness (Table 24.1) are neurologic in about 40% of patients (usually after the age of 12 years) (Brewer, 2000a; Lorincz, 2010). The remainder present with symptoms of liver disease (about 40%) (usually at an earlier age) (Manolaki et al., 2009) or a psychiatric illness (about 15%). The psychiatric picture may show a change in personality or mood. Psychosis is rare. What determines these individual variations in clinical presentation is not clear. One factor has been determined; patients with ApoE epsilon3/3 genotype have delayed onset of symptoms compared to all other ApoE genotypes (Schiefermeier et al., 2000). Symptoms usually appear between the ages of 11 and 25 years, but can occur as early as 4 and as late as 50+ years (Starosta-Rubinstein et al., 1987; Stremmel et al., 1991; Walshe and Yealland, 1992; Ferenci et al., 2007). Some patients with Wilson disease have autonomic nervous system abnormalities (Bhattacharya et al., 2002; Meenakshi-Sundaram et al., 2002).

| Liver disease (40%) |

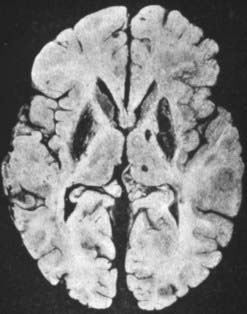

The pathologic abnormalities in the brain are primarily in the basal ganglia, with cavitary necrosis of the putamen and caudate, associated with neuronal loss, axonal degeneration and astrocytosis (Fig. 24.1). In addition, there is cortical atrophy. In a recent pathologic study of eight patients, six had neurological manifestations clinically (Meenakshi-Sundaram et al., 2008). Of these six, five had central pontine myelinolysis, five had subcortical white matter cavitations, four had putaminal softening, and six had variable ventricular dilatation. The liver in Wilson disease develops cirrhosis, typically of the nodular type.

Figure 24.1 Postmortem brain of a patient with Wilson disease showing the cavitary necrosis of the basal ganglia.

From Wilson SAK. Progressive lenticular degeneration: A familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Brain 1912;34:295–507.

A detailed analysis of the psychiatric presentation of 15 patients showed an affective disorder spectrum abnormality in 11 and a schizophreniform illness in 3 (Srinivas et al., 2008). Note was made that while the psychiatric symptoms improved in five patients with de-coppering therapy, seven patients needed symptomatic treatment as well.

Those with neurologic abnormalities usually present in the second or third decade, as (1) an akinetic-rigid syndrome resembling parkinsonism, (2) a generalized dystonic syndrome (pure chorea is uncommon), or (3) postural and intention tremor with ataxia, titubation and dysarthria (pseudosclerosis) (Table 24.2 and Video 24.1). The tremor may be mild, but is classically a slow, high-amplitude proximal tremor with the appearance of “wing-beating” when the arms are elevated and the hands placed near the nose. Dysarthria and clumsiness of the hands are common presenting features. The speech abnormality may include rapid speech, hypophonia, and slurring. It is most unusual for the illness to present with a gait disorder. No two patients with Wilson disease are ever quite the same. The facile grinning face with drooling saliva is characteristic. Early pseudobulbar features are common. Eye movements can be disordered with slow saccades (Kirkham and Kamin, 1974) and occasionally ophthalmoplegia (Gadoth and Liel, 1980). Vision and sensation are not affected, and paralysis does not occur although pyramidal signs may be evident. Sphincter control is spared. Seizures are infrequent (Smith and Mattson, 1967). Cognitive changes are common, even to the extent of a frank dementia. Changes in school or work performance are often the initial indication of the illness. Impulsiveness or antisocial behavior, and other indices of personality change are common (Dening and Berrios, 1989; Dening, 1991; Akil and Brewer, 1995). ![]()

Table 24.2 Number (percentage) of Wilson disease patients with different initial symptoms and signs

| Juveniles (n = 65) | Adults (n = 71) | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Personality change | 21 (32) | 23 (32) |

| Speech defect | 63 (41) | 42 (30) |

| Drooling | 31 (20) | 22 (16) |

| Dysphagia | 14 (9) | 7 (5) |

| Hand tremor | 48 (31) | 55 (39) |

| Hand clumsy | 32 (21) | 20 (14) |

| Abnormal gait | 34 (22) | 18 (13) |

| Fall at work or school | 40 (26) | |

| Signs | ||

| Personality disorder | 14 (21) | 13 (18) |

| Dysarthria | 34 (52) | 19 (27) |

| Gait abnormal | 8 (12) | 5 (7) |

| Eye movement abnormal | 4 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Drooling | 18 (28) | 11 (15) |

| Parkinsonian facies | 15 (23) | 5 (7) |

| Open mouth | 10 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Bradykinesia | 6 (9) | 3 (4) |

| Tongue abnormal | 11 (17) | 9 (13) |

| UL tremor | 17 (26) | 23 (32) |

| UL dystonia | 14 (21) | 13 (18) |

| UL spontaneous movements | 8 (12) | 0 (0) |

| LL tremor | 2 (3) | 6 (8) |

| LL dystonia | 12 (18) | 0 (0) |

| LL spontaneous movements | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Liver disease | 19 (29) | 8 (11) |

UL, upper limb; LL lower limb.

From Walshe JM, Yealland M. Wilson’s disease: the problem of delayed diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55(8):692–696.

Many of those with neurologic complaints give a history of prior or concurrent liver disease. This may consist of a previous episode of acute hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, portal hypertension, or asymptomatic hepatosplenomegaly (Scheinberg and Sternlieb, 1984). An unexplained hemolytic anemia, renal disease with hematuria, amino-aciduria, renal tubular defects, and calculi (Wiebers et al., 1979), or skeletal disease with osteoporosis/osteomalacia (Carpenter et al., 1983) are other clues.

Laboratory testing can make a definitive diagnosis (Mak and Lam, 2008). The diagnosis (Table 24.3) is first tested by looking for reduced serum ceruloplasmin. However, 5% of those with Wilson disease have a normal serum ceruloplasmin. The concentration of this copper protein may be low in heterozygotes, in patients with severe protein loss, and with severe liver disease of other cause. Serum ceruloplasmin may be increased by pregnancy and estrogens. Serum total copper is low in many patients (but nonspecific; Kumar et al., 2007), and urinary copper excretion is nearly always raised. However, anything causing cholestasis (particularly drugs) may raise serum copper and increase urinary copper excretion. When an expert examines the cornea with a slit lamp, virtually all patients with neurologic Wilson disease show Kayser–Fleischer rings in the Descemet membrane (Fig. 24.2) (Wiebers et al., 1977). However, rare patients with neurologic Wilson disease but no Kayser–Fleischer rings have been described (Ross et al., 1985; Demirkiran et al., 1996). A Kayser–Fleischer ring occasionally is only seen in one eye (Madden et al., 1985). The yellow and brown copper deposits are seen at the limbus of the cornea, usually first visible and most dense at the upper and lower poles of the eye. Kayser–Fleischer rings are not present in all patients with the liver manifestations of Wilson disease and other liver disease can produce them (Fleming et al., 1977).

Table 24.3 The diagnosis of Wilson disease (WD)

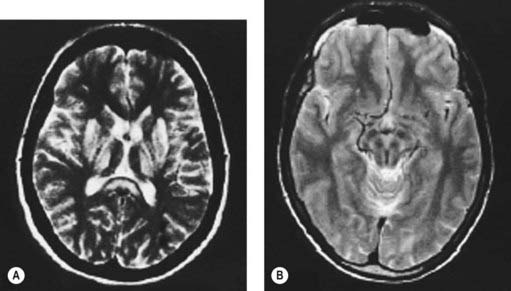

Computed tomography (Harik and Post, 1981; Williams and Walshe, 1981) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Starosta-Rubinstein et al., 1987; Alanen et al., 1999; Giagheddu et al., 2001) of the brain usually reveals changes in the basal ganglia, which are reversible with treatment. Caudate and putamen show increased T2 signal, and there may be similar changes in the substantia nigra pars compacta, periaqueductal gray, the pontine tegmentum, and the thalamus (Fig. 24.3A) (Saatci et al., 1997). Particularly striking are the putaminal lesions with a pattern of symmetric, bilateral, concentric-laminar T2 hyperintensity. Hyperintensity of the mesencephalon with sparing of the red nuclei and lateral aspect of the substantia nigra gives rise to the “face of the giant panda sign” (Fig. 24.3B) (Giagheddu et al., 2001). A “double panda sign” has also been described (Jacobs et al., 2003; Liebeskind et al., 2003). There can be hyperintensity of the middle cerebellar peduncle (Uchino et al., 2004). Another change has a similar appearance to central pontine myelinolysis, and this will improve with therapy (Sinha et al., 2007b). Diffusion-weighted MRI might also be useful (Favrole et al., 2006). In a study of 100 patients with various extrapyramidal diseases, the MRI features most useful to diagnose Wilson disease were the “face of giant panda” sign (seen in 14.3%), tectal plate hyperintensity (seen in 75%), central pontine myelinolysis-like abnormalities (seen in 62.5%), and concurrent signal changes in basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem (seen in 55.3%) (Prashanth et al., 2010).

Positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodopa shows reduced uptake in the striatum indicating loss of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway (Snow et al., 1991). Transcranial brain parenchyma sonography (TCS) detects lenticular nucleus hyperechogenicity, likely to be caused by copper accumulation, in neurologically symptomatic and asymptomatic Wilson disease patients (Walter et al., 2005). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy is also abnormal (Lucato et al., 2005; Tarnacka et al., 2009).

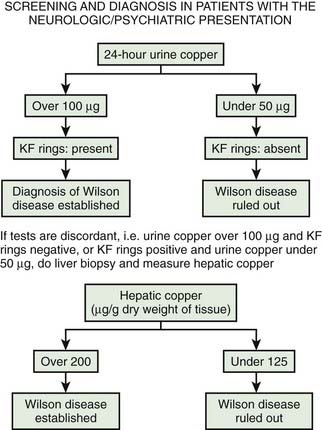

If there is any doubt about the diagnosis of Wilson disease in a patient presenting with neurologic problems under the age of 50, the first test would be a 24-hour urine copper excretion. In Wilson disease, excretion is typically more than 100 µg/24 hours and less than 50 µg/24 hours would exclude the diagnosis (Brewer and Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan, 1992; Brewer, 2000a). The definitive investigation is a liver biopsy with histologic assessment of tissue, and measurement of copper concentration. Guidelines for diagnosis have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (Roberts and Schilsky, 2008). An algorithm for the diagnosis is presented in Figure 24.4 (Brewer, 2008).

Genetic linkage studies to chromosome 13 may be valuable if other family members are available, and the gene can be closely searched for a mutation (Farrer et al., 1991; Caca et al., 2001; Davies et al., 2008). However, since there are so many possible mutations, such testing is not easily nor currently commercially available. Genotyping microarray is one method for looking for multiple mutations in one test (Gojova et al., 2008). Another technique is high-resolution melting analysis (Lin et al., 2010). Certainly if you know the high-frequency mutations in a population, it is possible to focus on those (Schilsky and Ala, 2010).

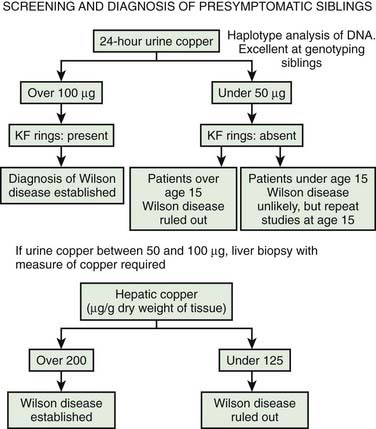

All siblings, who have a one in four chance of developing the illness, and cousins of known patients, should be screened for Wilson disease. Clinical signs, the presence of a Kayser–Fleischer ring, and abnormalities of serum and urine copper metabolism indicate the need for prophylactic treatment. If there is doubt, a liver biopsy may be undertaken, although molecular genetic techniques may prove diagnostic. An algorithm for evaluating presymptomatic siblings is presented in Figure 24.5 (Brewer, 2008).

Treatment of Wilson disease

The treatments for Wilson disease have been reviewed (Walshe, 1999; Brewer, 2000b, 2006; Gouider-Khouja, 2009; Lorincz, 2010). Guidelines for treatment have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (Roberts and Schilsky, 2008).

The gold standard of treatment (Table 24.4) is D-penicillamine (Shimizu et al., 1999; Walshe, 1999), building up to around 1 g/day, along with pyridoxine 25 mg/day. D-penicillamine should be introduced gradually because about 20% of patients may develop early side effects. The commonest are fever, a rash, and lymphadenopathy. Gradual reintroduction of D-penicillamine in low dosage under steroid cover may overcome these problems. More serious is the development of bone marrow depression. Unfortunately, 20–40% of those with neurologic disability will exhibit deterioration in the initial months of penicillamine treatment (Brewer, 1999). The neurologic deterioration can be severe; in one case the patient developed marked dystonia (status dystonicus) and died (Svetel et al., 2001). However, clinical improvement usually occurs within about 3 months, but it may take 6 months to a year before noticeable change takes place.

Reducing copper intake obviously is wise (Shimizu et al., 1999), but strict diets are rarely followed. Copper-rich foods include liver, nuts, chocolate, coffee, and shellfish.

An alternative to D-penicillamine is trientine (triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride) (Brewer, 1999; Shimizu et al., 1999), another chelator. Trientine undoubtedly is a valuable alternative in those intolerant to the latter, but it has advantages in that the initial worsening may not occur (Brewer, 1999). It can also be used in children where it can be effective with fewer side effects than with penicillamine (Taylor et al., 2009). Trientine is relatively safe (it can cause a sideroblastic anemia and can reactivate penicillamine-induced lupus), but is expensive and poorly absorbed.

Zinc and tetrathiomolybdate prevent the absorption of copper and are other alternatives. Zinc is an excellent agent for chronic use for mild cases and prevention (Hoogenraad, 2006; Linn et al., 2009), but may not be rapid enough for initiating therapy in someone with severe illness (Brewer, 1999, 2000a). Zinc is also the treatment of choice during pregnancy. Zinc can also be given safely in the pediatric age group (Brewer et al., 2001). Long-term follow-up of neurologically asymptomatic children treated for 10 years shows that zinc is well tolerated; liver disease improves, neurologic disorders do not develop, and growth is normal (Marcellini et al., 2005). Zinc monotherapy may fail and chelators would be needed (Weiss et al., 2011).

Tetrathiomolybdate is not easily available except experimentally (Brewer, 2005, 2009). An open-label study of 55 de novo patients reported treatment with doses of 120–410 mg per day for 8 weeks with follow-up for 3 years (Brewer et al., 2003). Only 2 (4%) showed initial neurologic deterioration, and overall neurologic improvement was excellent. Five patients had bone marrow suppression and 3 had aminotransferase elevation; the authors thought that this may have been precipitated by a too rapid dose escalation. A randomized, double-blind trial of 48 patients compared tetrathiomolybdate with trientine (Brewer et al., 2006). Patients either received 500 mg of trientine hydrochloride two times per day or 20 mg of tetrathiomolybdate three times per day with meals and 20 mg three times per day between meals for 8 weeks. All patients received 50 mg of zinc twice a day. There were more side effects (including neurologic deterioration) with trientine. For those patients that did not deteriorate the improvement was similar, but given the side effects tetrathiomolybdate should be preferred. It has now been demonstrated that free copper levels drop with tetrathiomolybdate therapy, while they might rise with trientine (Brewer et al., 2009). This may explain the early deterioration with trientine.

With therapy, in addition to clinical improvement, there is also radiologic improvement (Sinha et al., 2007a). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, particularly measuring N-acetylaspartate (NAA), can be helpful in assessment of treatment efficacy (Tarnacka et al., 2008).

In desperate cases, injection of dimercaprol (BAL) still may be life-saving (Scheinberg and Sternlieb, 1995). But because injections are painful, this cannot be used chronically (Walshe, 1999).

The role of these alternative agents in the treatment of Wilson disease is debated, and there is a nice formal debate published in Movement Disorders (Brewer, 1999; LeWitt, 1999; Walshe, 1999). Brewer (1999) takes the strong view that D-penicillamine should not be used. He and others favor zinc, or a combination of zinc and trientine, or tetrathiomolybdate, on the grounds that such an approach reduces the chances of initial neurologic deterioration, and causes fewer side effects than D-penicillamine (Czlonkowska et al., 1996; Brewer, 1999, 2000a, 2005; Schilsky, 2001). In a systematic review of the literature, for neurologic Wilson disease, zinc was best tolerated and had good efficacy (Wiggelinkhuizen et al., 2009).

Liver transplantation has also been employed, and cures Wilson disease (Schilsky et al., 1994; Shimizu et al., 1999; Podgaetz and Chan, 2003; Arnon et al., 2011). The neurologic manifestations can be reversed in about 80% of cases, and liver transplantation can be undertaken for the neurologic disorder even with stable liver disease (Stracciari et al., 2000; Geissler et al., 2003). A series of 21 patients had a mean follow-up of 5.2 years and an actuarial follow-up of 10 years (Schumacher et al., 2001). All patients did well with the neurologic functioning improving over 1–1.5 years. In a series of 24 patients with a mean follow-up period of 92 months, quality of life improved to the same level as controls in the general population (Sutcliffe et al., 2003). In a series of 13 patients, all did well, and those without neurologic manifestations before transplant did not develop them (Pabon et al., 2008). Other series also report good results (Marin et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2009; Yoshitoshi et al., 2009).

Hereditary deficiency of ceruloplasmin

A rare condition, hereditary deficiency of ceruloplasmin, can cause a movement disorder. In this autosomal recessive disorder due to gene defects in the ceruloplasmin gene (Yazaki et al., 1998), homozygotes develop iron overload (Miyajima et al., 1987; Harris et al., 1995). The disorder is estimated to occur in 0.5 persons per million in Japan (Miyajima et al., 1999). Ceruloplasmin oxidizes ferrous iron to ferric iron (so some call it ceruloplasmin “ferroxidase”), which is stored in ferritin and hemosiderin. Ferric iron can be transported out of cells. Absence of ceruloplasmin leads to a low serum iron with normal total iron binding capacity, and sometimes to anemia. Serum ferritin, and liver and brain iron concentrations are increased. Brain MRI shows increased iron deposition in the striatum, substantia nigra, red nuclei, and dentate nuclei. T2 hypointensities can be marked, including the cerebral cortex (Grisoli et al., 2005). Clinical presentation has been with insulin-dependent diabetes, retinal degeneration, subcortical dementia, and a movement disorder which typically is a facial dyskinesia (blepharospasm and oral dystonia) and torticollis, rigidity, and sometimes ataxia (Miyajima et al., 1987; Kawanami et al., 1996). One patient has presented with parkinsonism (Kohno et al., 2000). A review of 33 patients found the age at diagnosis to be 16 to 71, and there was cognitive impairment in 42%, cranial-facial dyskinesia in 28%, cerebellar ataxia in 46%, and retinal degeneration in 75% of patients (McNeill et al., 2008). Treatment is by iron chelation with desferrioxamine (Miyajima et al., 1997). One patient was successfully treated with repeated infusions of fresh frozen plasma (containing ceruloplasmin) (Yonekawa et al., 1999).

Hypoceruloplasminemia-related movement disorder (HCMD)

There is one report of HCMD without Kayser–Fleischer rings and without the Wilson disease mutation (Lirong et al., 2009). Patients presented with parkinsonism, tremor, dystonia, ataxia, and a tic disorder. It is not clear what these patients have, and whether this is even a homogeneous entity.

Akil M., Brewer G.J. Psychiatric and behavioral abnormalities in Wilson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1995;65:171-178.

Ala A., Walker A.P., Ashkan K., et al. Wilson’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):397-408.

Alanen A., Komu M., Penttinen M., Leino R. Magnetic resonance imaging and proton MR spectroscopy in Wilson’s disease. Br J Radiol. 1999;72(860):749-756.

Arnon R., Annunziato R., Schilsky M., et al. Liver transplantation for children with Wilson disease: a comparison of outcomes between children and adults. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(1):E52-E60.

Bhattacharya K., Velickovic M., Schilsky M., Kaufmann H. Autonomic cardiovascular reflexes in Wilson’s disease. Clin Auton Res. 2002;12(3):190-192.

Brewer G.J. Penicillamine should not be used as initial therapy in Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14(4):551-554.

Brewer G.J. Recognition, diagnosis, and management of Wilson’s disease. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223(1):39-46.

Brewer G.J. Wilson’s disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(3):193-204.

Brewer G.J. Neurologically presenting Wilson’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(3):185-192.

Brewer G.J. Novel therapeutic approaches to the treatment of Wilson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7(3):317-324.

Brewer G.J. Wilson’s disease. In: Hallett M., Poewe W., editors. Therapeutics of Parkinson’s Disease and Other Movement Disorders. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008:251-261.

Brewer G.J. The use of copper-lowering therapy with tetrathiomolybdate in medicine. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(1):89-97.

Brewer G.J., Askari F., Dick R.B., et al. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with tetrathiomolybdate: V. control of free copper by tetrathiomolybdate and a comparison with trientine. Transl Res. 2009;154(2):70-77.

Brewer G.J., Askari F., Lorincz M.T., et al. Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate: IV. Comparison of tetrathiomolybdate and trientine in a double-blind study of treatment of the neurologic presentation of Wilson disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):521-527.

Brewer G.J., Dick R.D., Johnson V.D., et al. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc XVI: treatment during the pediatric years. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;137(3):191-198.

Brewer G.J., Hedera P., Kluin K.J., et al. Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate: III. Initial therapy in a total of 55 neurologically affected patients and follow-up with zinc therapy. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(3):379-385.

Brewer G.J., Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V. Wilson disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1992;71(3):139-164.

Caca K., Ferenci P., Kuhn H.J., Polli C., et al. High prevalence of the H1069Q mutation in East German patients with Wilson disease: rapid detection of mutations by limited sequencing and phenotype-genotype analysis. J Hepatol. 2001;35(5):575-581.

Carpenter T.O., Carnes D.L.Jr, Anast C.S. Hypoparathyroidism in Wilson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(15):873-877.

Cheng F., Li G.Q., Zhang F., Li X.C., et al. Outcomes of living-related liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease: a single-center experience in China. Transplantation. 2009;87(5):751-757.

Curtis D., Durkie M., Balac P., et al. A study of Wilson disease mutations in Britain. Hum Mutat. 1999;14(4):304-311.

Cuthbert J.A. Wilson’s disease. Update of a systemic disorder with protean manifestations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27(3):655-681. vi–vii

Czlonkowska A., Gajda J., Rodo M. Effects of long-term treatment in Wilson’s disease with D-penicillamine and zinc sulphate. J Neurol. 1996;243(3):269-273.

Czlonkowska A., Gromadzka G., Chabik G. Monozygotic female twins discordant for phenotype of Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(7):1066-1069.

Davies L.P., Macintyre G., Cox D.W. New mutations in the Wilson disease gene, ATP7B: implications for molecular testing. Genet Test. 2008;12(1):139-145.

Demirkiran M., Jankovic J., Lewis R.A., Cox D.W. Neurologic presentation of Wilson disease without Kayser-Fleischer rings. Neurology. 1996;46(4):1040-1043.

Dening T.R. The neuropsychiatry of Wilson’s disease: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1991;21(2):135-148.

Dening T.R., Berrios G.E. Wilson’s disease. Psychiatric symptoms in 195 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(12):1126-1134.

Farrer L.A., Bowcock A.M., Hebert J.M., et al. Predictive testing for Wilson’s disease using tightly linked and flanking DNA markers. Neurology. 1991;41(7):992-999.

Favrole P., Chabriat H., Guichard J.P., Woimant F. Clinical correlates of cerebral water diffusion in Wilson disease. Neurology. 2006;66(3):384-389.

Ferenci P., Czlonkowska A., Merle U., et al. Late-onset Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4):1294-1298.

Fleming C.R., Dickson E.R., Wahner H.W., et al. Pigmented corneal rings in non-Wilsonian liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86(3):285-288.

Gadoth N., Liel Y. Transient external ophthalmoplegia in Wilson’s disease. Metab Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1980;4(2):71-72.

Geissler I., Heinemann K., Rohm S., et al. Liver transplantation for hepatic and neurological Wilson’s disease. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(4):1445-1446.

Giagheddu M., Tamburini G., Piga M., et al. Comparison of MRI, EEG, EPs and ECD-SPECT in Wilson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103(2):71-81.

Gojova L., Jansova E., Kulm M., et al. Genotyping microarray as a novel approach for the detection of ATP7B gene mutations in patients with Wilson disease. Clin Genet. 2008;73(5):441-452.

Gouider-Khouja N. Wilson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(Suppl 3):S126-S129.

Grisoli M., Piperno A., Chiapparini L., et al. MR imaging of cerebral cortical involvement in aceruloplasminemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(3):657-661.

Harik S.I., Post M.J. Computed tomography in Wilson disease. Neurology. 1981;31(1):107-110.

Harris Z.L., Takahashi Y., Miyajima H., et al. Aceruloplasminemia: molecular characterization of this disorder of iron metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(7):2539-2543.

Hoogenraad T.U. Paradigm shift in treatment of Wilson’s disease: zinc therapy now treatment of choice. Brain Dev. 2006;28(3):141-146.

Jacobs D.A., Markowitz C.E., Liebeskind D.S., Galetta S.L. The “double panda sign” in Wilson’s disease. Neurology. 2003;61(7):969.

Kawanami T., Kato T., Daimon M., et al. Hereditary caeruloplasmin deficiency: clinicopathological study of a patient. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(5):506-509.

Kirkham T.H., Kamin D.F. Slow saccadic eye movements in Wilson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37(2):191-194.

Kohno S., Miyajima H., Takahashi Y., Inoue Y. Aceruloplasminemia with a novel mutation associated with parkinsonism. Neurogenetics. 2000;2(4):237-238.

Kumar N., Butz J.A., Burritt M.F. Clinical significance of the laboratory determination of low serum copper in adults. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(10):1402-1410.

LeWitt P.A. Penicillamine as a controversial treatment for Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14(4):555-556.

Liebeskind D.S., Wong S., Hamilton R.H. Faces of the giant panda and her cub: MRI correlates of Wilson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(5):682.

Lin C.W., Er T.K., Tsai F.J., et al. Development of a high-resolution melting method for the screening of Wilson disease-related ATP7B gene mutations. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(17–18):1223-1231.

Linn F.H., Houwen R.H., van Hattum J., et al. Long-term exclusive zinc monotherapy in symptomatic Wilson disease: experience in 17 patients. Hepatology. 2009;50(5):1442-1452.

Lirong J., Jianjun J., Hua Z., et al. Hypoceruloplasminemia-related movement disorder without Kayser-Fleischer rings is different from Wilson disease and not involved in ATP7B mutation. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1130-1137.

Lorincz M.T. Neurologic Wilson’s disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1184:173-187.

Loudianos G., Gitlin J.D. Wilson’s disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20(3):353-364.

Lucato L.T., Otaduy M.C., Barbosa E.R., et al. Proton MR spectroscopy in Wilson disease: analysis of 36 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(5):1066-1071.

Madden J.W., Ironside J.W., Triger D.R., Bradshaw J.P. An unusual case of Wilson’s disease. Q J Med. 1985;55(216):63-73.

Mak C.M., Lam C.W. Diagnosis of Wilson’s disease: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2008;45(3):263-290.

Manolaki N., Nikolopoulou G., Daikos G.L., et al. Wilson disease in children: analysis of 57 cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(1):72-77.

Marcellini M., Di Ciommo V., Callea F., et al. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc from the time of diagnosis in pediatric patients: a single-hospital, 10-year follow-up study. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145(3):139-143.

Marin C., Robles R., Parrilla G., et al. Liver transplantation in Wilson’s disease: are its indications established? Transplant Proc. 2007;39(7):2300-2301.

McNeill A., Pandolfo M., Kuhn J., et al. The neurological presentation of ceruloplasmin gene mutations. Eur Neurol. 2008;60(4):200-205.

Meenakshi-Sundaram S., Mahadevan A., Taly A.B., et al. Wilson’s disease: a clinico-neuropathological autopsy study. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(4):409-417.

Meenakshi-Sundaram S., Taly A.B., Kamath V., et al. Autonomic dysfunction in Wilson’s disease – a clinical and electrophysiological study. Clin Auton Res. 2002;12(3):185-189.

Miyajima H., Kohno S., Takahashi Y., et al. Estimation of the gene frequency of aceruloplasminemia in Japan. Neurology. 1999;53(3):617-619.

Miyajima H., Nishimura Y., Mizoguchi K., et al. Familial apoceruloplasmin deficiency associated with blepharospasm and retinal degeneration. Neurology. 1987;37(5):761-767.

Miyajima H., Takahashi Y., Kamata T., et al. Use of desferrioxamine in the treatment of aceruloplasminemia. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(3):404-407.

Pabon V., Dumortier J., Gincul R., et al. Long-term results of liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32(4):378-381.

Petrukhin K., Fischer S.G., Pirastu M., et al. Mapping, cloning and genetic characterization of the region containing the Wilson disease gene. Nat Genet. 1993;5(4):338-343.

Podgaetz E., Chan C. Liver transplantation for Wilson s disease: our experience with review of the literature. Ann Hepatol. 2003;2(3):131-134.

Prashanth L.K., Sinha S., Taly A.B., Vasudev M.K. Do MRI features distinguish Wilson’s disease from other early onset extrapyramidal disorders? An analysis of 100 cases. Mov Disord. 2010;25(6):672-678.

Prashanth L.K., Taly A.B., Sinha S., et al. Wilson’s disease: diagnostic errors and clinical implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(6):907-909.

Reilly M., Daly L., Hutchinson M. An epidemiological study of Wilson’s disease in the Republic of Ireland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(3):298-300.

Roberts E.A., Schilsky M.L. Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):2089-2111.

Ross M.E., Jacobson I.M., Dienstag J.L., Martin J.B. Late-onset Wilson’s disease with neurological involvement in the absence of Kayser-Fleischer rings. Ann Neurol. 1985;17(4):411-413.

Saatci I., Topcu M., Baltaoglu F.F., et al. Cranial MR findings in Wilson’s disease. Acta Radiol. 1997;38(2):250-258.

Scheinberg I.H., Sternlieb I. Wilson’s disease. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1984.

Scheinberg I.H., Sternlieb I. Treatment of the neurologic manifestations of Wilson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(4):339-340.

Schiefermeier M., Kollegger H., Madl C., et al. The impact of apolipoprotein E genotypes on age at onset of symptoms and phenotypic expression in Wilson’s disease. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 3):585-590.

Schilsky M.L. Treatment of wilson’s disease: what are the relative roles of penicillamine, trientine, and zinc supplementation? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3(1):54-59.

Schilsky M.L., Ala A. Genetic testing for Wilson disease: availability and utility. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12(1):57-61.

Schilsky M.L., Scheinberg I.H., Sternlieb I. Liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease: indications and outcome. Hepatology. 1994;19(3):583-587.

Schumacher G., Platz K.P., Mueller A.R., et al. Liver transplantation in neurologic Wilson’s disease. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1–2):1518-1519.

Shah A.B., Chernov I., Zhang H.T., et al. Identification and analysis of mutations in the Wilson disease gene (ATP7B): population frequencies, genotype-phenotype correlation, and functional analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61(2):317-328.

Shimizu N., Yamaguchi Y., Aoki T. Treatment and management of Wilson’s disease. Pediatr Int. 1999;41(4):419-422.

Sinha S., Taly A.B., Prashanth L.K., et al. Sequential MRI changes in Wilson’s disease with de-coppering therapy: a study of 50 patients. Br J Radiol. 2007;80(957):744-749.

Sinha S., Taly A.B., Ravishankar S., et al. Central pontine signal changes in Wilson’s disease: distinct MRI morphology and sequential changes with de-coppering therapy. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17(4):286-291.

Smith C.K., Mattson R.H. Seizures in Wilson’s disease. Neurology. 1967;17(11):1121-1123.

Snow B.J., Bhatt M., Martin W.R., et al. The nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway in Wilson’s disease studied with positron emission tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(1):12-17.

Srinivas K., Sinha S., Taly A.B., et al. Dominant psychiatric manifestations in Wilson’s disease: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge!. J Neurol Sci. 2008;266(1–2):104-108.

Starosta-Rubinstein S., Young A.B., Kluin K., et al. Clinical assessment of 31 patients with Wilson’s disease. Correlations with structural changes on magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 1987;44(4):365-370.

Stracciari A., Tempestini A., Borghi A., Guarino M. Effect of liver transplantation on neurological manifestations in Wilson disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(3):384-386.

Stremmel W., Meyerrose K.W., Niederau C., et al. Wilson disease: clinical presentation, treatment, and survival. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(9):720-726.

Sutcliffe R.P., Maguire D.D., Muiesan P., et al. Liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease: long-term results and quality-of-life assessment. Transplantation. 2003;75(7):1003-1006.

Svetel M., Sternic N., Pejovic S., Kostic V.S. Penicillamine-induced lethal status dystonicus in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2001;16(3):568-569.

Tanzi R.E., Petrukhin K., Chernov I., et al. The Wilson disease gene is a copper transporting ATPase with homology to the Menkes disease gene. Nat Genet. 1993;5(4):344-350.

Tarnacka B., Szeszkowski W., Golebiowski M., Czlonkowska A. MR spectroscopy in monitoring the treatment of Wilson’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 2008;23(11):1560-1566.

Tarnacka B., Szeszkowski W., Golebiowski M., Czlonkowska A. Metabolic changes in 37 newly diagnosed Wilson’s disease patients assessed by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(8):582-586.

Taylor R.M., Chen Y., Dhawan A. Triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride (trientine) in children with Wilson disease: experience at King’s College Hospital and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(9):1061-1068.

Thomas G.R., Roberts E.A., Walshe J.M., Cox D.W. Haplotypes and mutations in Wilson disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56(6):1315-1319.

Uchino A., Sawada A., Takase Y., Kudo S. Symmetrical lesions of the middle cerebellar peduncle: MR imaging and differential diagnosis. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2004;3(3):133-140.

Walshe J.M. Penicillamine: the treatment of first choice for patients with Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14(4):545-550.

Walshe J.M., Yealland M. Wilson’s disease: the problem of delayed diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(8):692-696.

Walter U., Krolikowski K., Tarnacka B., et al. Sonographic detection of basal ganglia lesions in asymptomatic and symptomatic Wilson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1726-1732.

Wang H., Koschinsky M., Hamerton J.L. Localization of the processed gene for human ceruloplasmin to chromosome region 8q21.13–q23.1 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1988;47(4):230-231.

Weiss K.H., Gotthard D.N., Klemm D., et al. Zinc monotherapy is not as effective as chelating agents in treatment of Wilson disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(4):1189-1198.

Wiebers D.O., Hollenhorst R.W., Goldstein N.P. The ophthalmologic manifestations of Wilson’s disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977;52(7):409-416.

Wiebers D.O., Wilson D.M., McLeod R.A., Goldstein N.P. Renal stones in Wilson’s disease. Am J Med. 1979;67(2):249-254.

Wiggelinkhuizen M., Tilanus M.E., Bollen C.W., Houwen R.H. Systematic review: clinical efficacy of chelator agents and zinc in the initial treatment of Wilson disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(9):947-958.

Williams F.J., Walshe J.M. Wilson’s disease. An analysis of the cranial computerized tomographic appearances found in 60 patients and the changes in response to treatment with chelating agents. Brain. 1981;104(Pt 4):735-752.

Wilson S.A.K. Progressive lenticular degeneration: A familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Brain. 1912;34:295-507.

Yazaki M., Yoshida K., Nakamura A., et al. A novel splicing mutation in the ceruloplasmin gene responsible for hereditary ceruloplasmin deficiency with hemosiderosis. J Neurol Sci. 1998;156(1):30-34.

Yonekawa M., Okabe T., Asamoto Y., Ohta M. A case of hereditary ceruloplasmin deficiency with iron deposition in the brain associated with chorea, dementia, diabetes mellitus and retinal pigmentation: administration of fresh-frozen human plasma. Eur Neurol. 1999;42(3):157-162.

Yoshitoshi E.Y., Takada Y., Oike F., et al. Long-term outcomes for 32 cases of Wilson’s disease after living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87(2):261-267.