Chapter 646 Vesiculobullous Disorders

Many diseases are characterized by vesiculobullous lesions; they vary considerably in cause, age of onset, and pattern. The morphology of the blister often provides a visual clue to the location of the lesion within the skin. Blisters localized to the epidermal layers are thin-walled, relatively flaccid, and easily ruptured. Subepidermal blisters are tense, thick-walled, and more durable. Biopsies of blisters can be diagnostic because the level of cleavage within the skin and associated findings, such as the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate, are characteristic for a particular disorder. Other diagnostic procedures, such as immunofluorescence and electron microscopy, can often help distinguish vesiculobullous disorders that have nearly identical histopathologic findings (Table 646-1).

Table 646-1 SITES OF BLISTER FORMATION AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES FOR THE VESICULOBULLOUS DISORDERS

| DISORDER | BLISTER CLEAVAGE SITE | DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES |

|---|---|---|

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | IE | Zn level |

| Bullous impetigo | GL | Smear, culture |

| Bullous pemphigoid | SE (junctional) | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Candidosis | SC | KOH preparation, culture |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | SE | Direct immunofluorescence studies |

| Dermatophytosis | IE | KOH preparation, culture |

| Dyshidrotic eczema | IE | Routine histopathology |

| EB—simplex | IE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| EB of the hands and feet | IE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Junctional EB (letalis) | SE (junctional) | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Recessive dystrophic EB | SE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Dominant dystrophic EB | SE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis | IE | Routine histopathology |

| Erythema multiforme | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Erythema toxicum | SC, IE | Smear for eosinophils |

| Incontinentia pigmenti | IE | |

| Insect bites | IE | Routine histopathology |

| Linear IgA dermatosis | SE | Direct immunofluorescence studies |

| Mastocytosis | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Miliaria crystallina | IC | Routine histopathology |

| Neonatal pustular melanosis | SC, IE | Smear for cells |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | GL | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Tzanck smear | ||

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Suprabasal | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Tzanck smear | ||

| Scabies | IE | Scraping |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | GL | Routine histopathology |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Viral blisters | IE |

EB, epidermolysis bullosa; GL, granular layer; IC, intracorneal; IE, intraepidermal; KOH, potassium hydroxide; SC, subcorneal; SE, subepidermal.

646.1 Erythema Multiforme

Clinical Manifestations

EM has numerous morphologic manifestations on the skin, varying from erythematous macules, papules, vesicles, bullae, or urticaria-appearing plaques to patches of confluent erythema. The eruption appears most commonly in patients between the ages of 10 and 40 yr and usually is asymptomatic, although a burning sensation or pruritus may be present. The diagnosis of EM is established by finding the classic lesion: doughnut-shaped, target-like (iris or bull’s-eye) papules with an erythematous outer border, an inner pale ring, and a dusky purple to necrotic center (Figs. 646-1 and 646-2).

Gober MD, Laing JM, Burnett JW, et al. The Herpes simplex virus gene Pol expressed in herpes-associated erythema multiforme lesions upregulates/activates SP1 and inflammatory cytokines. Dermatology. 2007;215:97-106.

Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT. Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1883-1888.

Williams PM, Conklin RJ. Erythema multiforme: a review and contrast from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:67-76.

646.2 Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Etiology

Clinical Manifestations

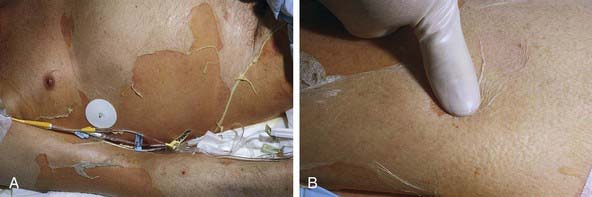

Cutaneous lesions in Stevens-Johnson syndrome generally consist initially of erythematous macules that rapidly and variably develop central necrosis to form vesicles, bullae, and areas of denudation on the face, trunk, and extremities. The skin lesions are typically more widespread than in EM and are accompanied by involvement of two or more mucosal surfaces, namely the eyes, oral cavity, upper airway or esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, or anogenital mucosa (Fig. 646-3). A burning sensation, edema, and erythema of the lips and buccal mucosa are often the presenting signs, followed by development of bullae, ulceration, and hemorrhagic crusting. Lesions may be preceded by a flu-like upper respiratory illness. Pain from mucosal ulceration is often severe, but skin tenderness is minimal to absent in Stevens-Johnson syndrome, in contrast to pain in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Corneal ulceration, anterior uveitis, panophthalmitis, bronchitis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, enterocolitis, polyarthritis, hematuria, and acute tubular necrosis leading to renal failure may occur. Disseminated cutaneous bullae and erosions may result in increased insensible fluid loss and a high risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis. New lesions occur in crops, and complete healing may take 4-6 wk; ocular scarring, visual impairment, and strictures of the esophagus, bronchi, vagina, urethra, or anus may remain. Nonspecific laboratory abnormalities in Stevens-Johnson syndrome include leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and, occasionally, increased liver transaminase levels and decreased serum albumin values. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is the most severe disorder in the clinical spectrum of the disease, involving considerable constitutional toxicity and extensive necrolysis of the mucous membranes and > 30% of the body surface area (Fig. 646-4).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome includes toxic epidermal necrolysis, urticaria, DRESS (drug rash [or reaction] with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome (Chapter 637.2) and other drug eruptions and viral exanthems, including Kawasaki disease.

Borchers AT, Lee JL, Naguwa SM, et al. Stevens-Johnson and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Autoimmune Rev. 2008;7:598-605.

Chung WH, Hung SI, Yang JY, et al. Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nat Med. 2008;14:1343-1350.

de Prost N, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Duong T, et al. Bacteremia in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Medicine. 2010;89(1):28-36.

Ferrel PB, McLeod HL. Carbamazepine, HLA-B*1502 and risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: US FDA recommendations. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1543-1546.

Gregory DG. The ophthalmologic management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2008;6:87-95.

Gubinelli E, Canzona F, Tonanzi T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with etanercept. J Dermatol. 2009;36:150-153.

Hazin R, Ibrahimi OA, Hazin MT, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Ann Med. 2008;40:129-138.

Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Aihara M, et al. HLA-B locus in Japanese patients with anti-epileptic and allopurinol related Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1617-1622.

Williams PM, Conklin RJ. Erythema multiforme: a review and contrast from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:67-76.

646.3 Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Epidemiology and Etiology

The pathogenesis of toxic epidermal necrolysis is not proved but may involve a hypersensitivity phenomenon that results in damage primarily to the basal cell layer of the epidermis. Epidermal damage appears to result from keratinocyte apoptosis (Chapter 646.2). This condition is triggered by many of the same factors that are thought to be responsible for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, principally drugs such as the sulfonamides, amoxicillin, phenobarbital, hydantoin, butazones, and allopurinol. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is defined by (1) widespread blister formation and morbilliform or confluent erythema, associated with skin tenderness; (2) absence of target lesions; (3) sudden onset and generalization within 24-48 hr; (4) histologic findings of full-thickness epidermal necrosis and a minimal to absent dermal infiltrate. These criteria categorize toxic epidermal necrolysis as a separate entity from EM.

Clinical Manifestations

The prodrome consists of fever, malaise, localized skin tenderness, and diffuse erythema. Inflammation of the eyelids, conjunctivae, mouth, and genitals may precede skin lesions. Flaccid bullae may develop, although this is not a prominent feature. Characteristically, full-thickness epidermis is lost in large sheets (see Fig. 646-4). Nikolsky sign (denudation of the skin with gentle tangential pressure) is present but only in the areas of erythema (see Fig. 646-4). Healing takes place over 14 or more days. Scarring, particularly of the eyes, may result in corneal opacity. The course may be relentlessly progressive, complicated by severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, shock, and secondary localized infection and septicemia. Loss of nails and hair may also occur. Long-term morbidity includes alterations in skin pigmentation, eye problems (lack of tears, conjunctival scarring, loss of lashes), and strictures of mucosal surfaces. The differential diagnosis includes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, in which the blister cleavage plane is intraepidermal; graft versus host disease; chemical burns; drug eruptions; toxic shock syndrome; and pemphigus.

Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS syndrome; Chapter 637.2) is a multisystem reaction that appears approximately 4 wk to 3 mo after the start of therapy with phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone, primidone, or other drugs, most commonly antibiotics. The mucocutaneous eruption may be identical to that of EM, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis, but the reaction also typically includes lymphadenopathy as well as fever, hepatic, renal and pulmonary disease, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and leukocytosis.

Treatment

Appreciation of the specific etiologic factor is crucial. When the disorder is drug induced, administration of the drug must be discontinued as soon as possible. Management is similar to that for severe burns and may be best accomplished in a burn unit (Chapter 68). It may include strict reverse isolation, meticulous fluid and electrolyte therapy, use of an air-fluid bed, and daily cultures. Systemic antibiotic therapy is indicated when secondary infection is evident or suspected. Skin care consists of cleansing with isotonic saline or Burow solution. Biologic or colloid gel (Hydrogel) dressings alleviate pain and reduce fluid loss. Narcotics are often required for pain relief. Mouth and eye care, as for EM major, may be necessary. Because of an immune mechanism, systemic glucocorticosteroids and IVIG have been used with apparent success. Nonetheless, this treatment remains controversial.

Endorf FW, Cancio LC, Gibran NS. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:706-712.

Levi N, Bastuji-Garin S, Mockenhaupt M, et al. Medications as risk factors of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children: a pooled analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e297-e304.

646.4 Mechanobullous Disorders

Epidermolysis Bullosa

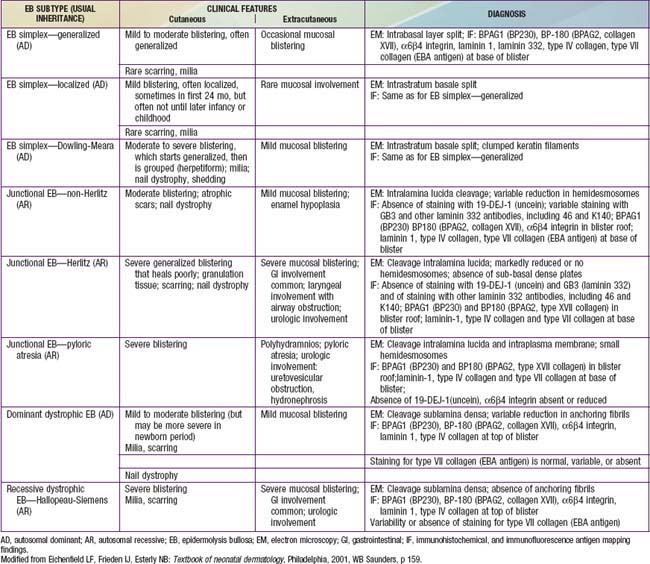

Diseases categorized under the general term epidermolysis bullosa (EB) are a heterogeneous group of congenital, hereditary blistering disorders. They differ in severity and prognosis, clinical and histologic features, and inheritance patterns, but are all characterized by induction of blisters by trauma and exacerbation of blistering in warm weather. The disorders can be categorized under 3 major headings with multiple subgroupings: epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB), and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) (Table 646-2). Kindler syndrome (Kindlin-1 gene), which includes poikiloderma and photosensitivity as well as easy blistering, is also considered a separate form of EB.

Table 646-2 CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF SELECTED EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA SUBTYPES IN THE NEONATAL PERIOD

Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex

EBS—localized (formerly Weber-Cockayne) predominantly affects the hands and feet and often manifests when a child begins to walk; onset may be delayed until puberty or early adulthood, when heavy shoes are worn or the feet are subjected to increased trauma. Bullae are usually restricted to the hands and feet (Fig. 646-5); rarely, they occur elsewhere, such as the dorsal aspect of the arms and the shins. The disorder ranges from mildly incapacitating to crippling at times of severe exacerbations.

EBS—Dowling-Meara (herpetiformis) is characterized by grouped blisters resembling those of herpes simplex (Fig. 646-6). During infancy, blistering may be severe and extensive, may involve mucous membranes, and may result in shedding of nails, formation of milia, and mild pigmentary changes, without scarring. After the first few months of life, warm temperatures do not appear to exacerbate blistering. Hyperkeratosis and hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles may develop, but generally, the condition improves with age.

Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa

JEB—Herlitz is an autosomal recessive condition that is life threatening. Blisters appear at birth or develop during the neonatal period, particularly on the perioral area, scalp, legs, diaper area, and thorax. Nails eventually become dystrophic and then often permanently lost. Mucous membrane involvement may be severe, and ulceration of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary epithelium has been documented in many affected children, although less frequently than in severe recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB). Healing is delayed, and vegetating granulomas may persist for a long time. Large, moist, erosive plaques (Fig. 646-7) may provide a portal of entry for bacteria, and septicemia is a frequent cause of death. Mild atrophy may be seen in areas of recurrent blistering. Defective dentition with early loss of teeth as a result of rampant caries is characteristic. Growth retardation and recalcitrant anemia are almost invariable. In addition to infection, cachexia and circulatory failure are common causes of death. Most patients die within the first 3 yr of life.

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa

Dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DDEB) is the most common type of DEB. The spectrum of DDEB is varied. Blisters may be manifest at birth and are often limited and characteristically form over acral bony prominences. The lesions heal promptly, with the formation of soft, wrinkled scars, milia, and alterations in pigmentation (Fig. 646-8). Abnormal nails and nail loss are common. In many cases, the blistering process is mild, causing little restriction of activity and not impairing growth and development. Mucous membrane involvement tends to be minimal.

Figure 646-8 Scarring with milia formation over the knee in dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

RDEB—severe generalized (formerly RDEB—Hallopeau-Siemens) is the most incapacitating form of epidermolysis bullosa, although the clinical spectrum is wide. Some patients have blisters, scarring, and milia formation primarily on the hands, feet, elbows, and knees (Fig. 646-9). Others have extensive erosions and blister formation at birth that seriously impedes their care and feeding. Mucous membrane lesions are common and may cause severe nutritional deprivation, even in older children, whose growth may be retarded. During childhood, esophageal erosions and strictures, scarring of the buccal mucosa, flexion contractures of joints secondary to scarring of the integument, development of cutaneous carcinomas, and the development of digital fusion may significantly limit the quality of life (Fig. 646-10).

Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

Fine JD, Hall M, Weiner M, et al. The risk of cardiomyopathy in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:677-682.

Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, et al. Cause-specific risks of childhood death in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. J Pediatr. 2008;152:276-280.

Wagner JE, Ishida-Yamamoto A, McGrath JA, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):629-638.

646.5 Pemphigus

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus Foliaceus

Clinical Manifestations

The superficial blisters rupture quickly, leaving erosions surrounded by erythema that heal with crusting and scaling (Fig. 646-11). Nikolsky sign is present. Focal lesions are usually localized to the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk. Mucous membrane lesions are minimal or absent. Pruritus, pain, and a burning sensation are frequent complaints. The clinical course varies but is generally more benign than that of PV. Fogo selvagem, which is endemic in certain areas of Brazil, is identical clinically, histopathologically, and immunologically to pemphigus foliaceus.

Bullous Pemphigoid

Amagai M, Ikeda S, Shimizu H, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:595-603.

Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, et al. A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus. N Engl J Med. 2009;357:545-552.

Razzaque Ahmed A, Spigelman Z, Cavacini LA, et al. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with rituximab and intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1772-1778.

Yazganoglu KD, Baykal C, Kucukoglu R. Childhood pemphigus vulgaris: five cases in 16 years. J Dermatol. 2006;33:846-849.

646.6 Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Etiology/Pathogenesis

In dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), IgA antibodies are directed at epidermal transglutaminase. Gluten-sensitive enteropathy is found in all patients with DH, although the majority are asymptomatic or have minimal gastrointestinal symptoms (Chapter 330.2). The severity of the skin disease and the responsiveness to gluten restriction do not correlate with the severity of the intestinal inflammation. An antibody to smooth muscle endomysium is found in 70-90% of patients with DH. Ninety percent of patients with the disease express HLA DQ2. HLA DQ2–negative patients with DH usually express HLA DQ8.

Clinical Manifestations

DH is characterized by symmetric, grouped, small, tense, erythematous, stinging, intensely pruritic papules and vesicles. The eruption is pleomorphic, including erythematous, urticarial, papular, vesicular, and bullous lesions. Sites of predilection are the knees, elbows, shoulders, buttocks, and scalp; mucous membranes are usually spared. Hemorrhagic lesions may develop on the palms and soles. When pruritus is severe, excoriations may be the only visible sign (Fig. 646-12).

Alonso-Llamazares J, Gibson LE, Rogers RS. Clinical, pathologic and immunopathologic features of dermatitis herpetiformis: review of the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:910-919.

Templet JT, Welsh JP, Cusack CA. Childhood dermatitis herpetiformis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:473-476.

Zone JJ. Skin manifestations of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S87-S91.

646.7 Linear IgA Dermatosis (Chronic Bullous Dermatosis of Childhood)

Clinical Manifestations

This rare dermatosis is most common in the 1st decade of life, with a peak incidence during the preschool years. The eruption consists of many large, tense bullae filled with clear or hemorrhagic fluid that develop on a normal or erythematous, urticarial base. Areas of predilection are the genitals and buttocks (Fig. 646-13), the perioral region, and the scalp. Sausage-shaped bullae may be arranged in an annular or rosette-like fashion around a central crust (Fig. 646-14). Erythematous plaques with gyrate margins bordered by intact bullae may develop over larger areas. Pruritus may be absent or very intense, and systemic signs or symptoms are absent.

Ho JC, NG PL, Tan SH, et al. Childhood linear IgA bullous disease triggered by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E40-E43.

Nanda A, Dvorak R, Al-Sabah H, et al. Linear IgA disease of childhood: an experience from Kuwait. Pediatric Dermatol. 2006;23:443-447.

Onodera H, Mohm MCJr, Yoshinda A, et al. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Dermatol. 2005;32:759-764.