Uvea

Normal Anatomy

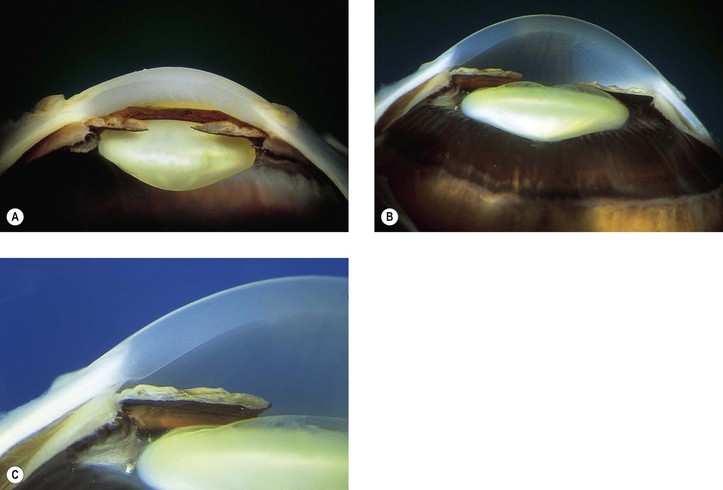

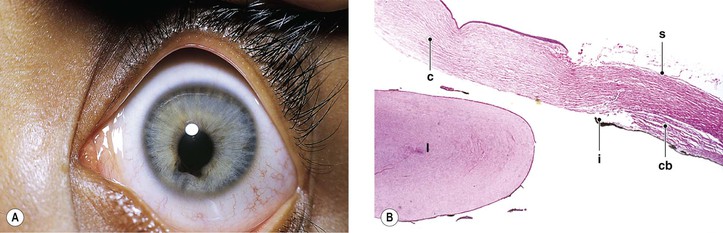

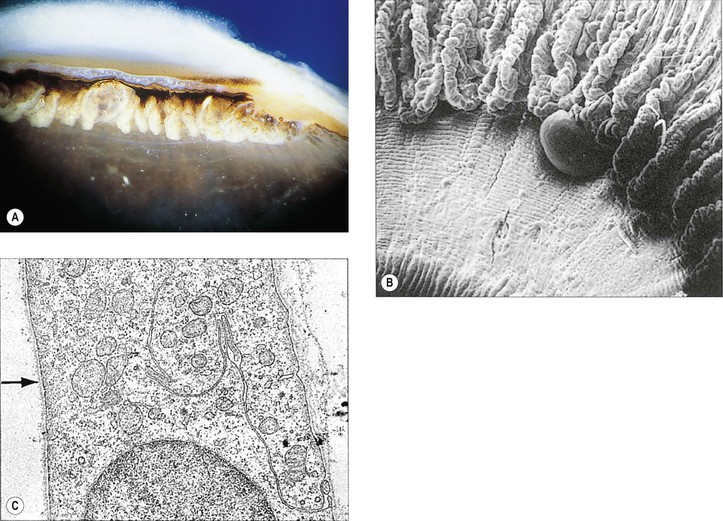

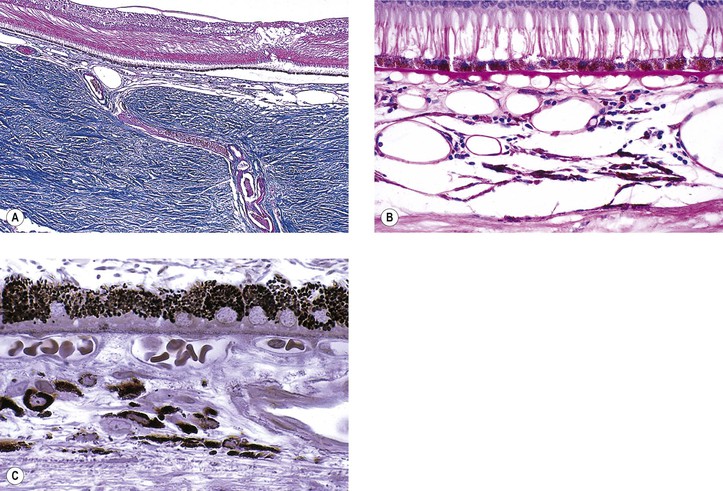

I. The uvea is composed of three parts: iris, ciliary body, and choroid (Figs. 9.1 and 9.2).

A. The iris is a circular, extremely thin diaphragm separating the anterior or aqueous compartment of the eye into anterior and posterior chambers.

B. The ciliary body, contiguous with the iris anteriorly and the choroid posteriorly, is divisible into an anterior ring, the pars plicata (approximately 1.5 mm wide in meridional sections), containing 70–75 meridional folds or processes, and a posterior ring, the pars plana (approximately 3.5–4 mm wide in meridional sections).

C. The largest part of the uvea, the choroid, extends from the ora serrata to the optic nerve.

Congenital and Developmental Defects

Persistent Pupillary Membrane

I. Persistence of a pupillary membrane (Fig. 9.3), a common clinical finding, is caused by incomplete atrophy (resorption) of the anterior lenticular fetal vascular arcades and associated mesodermal tissue derived from the primitive annular vessel.

II. Histologically, fine strands of mesodermal tissue are seen, rarely with blood vessels.

Persistent Tunica Vasculosa Lentis

Heterochromia Iridis and Iridum

Heterochromia iridum (see Chapter 17) is a difference in pigmentation between the two irises, as contrasted to heterochromia iridis, which is an alteration within a single iris.

Congenital and Developmental Defects of the Pigment Epithelium

See Chapter 17.

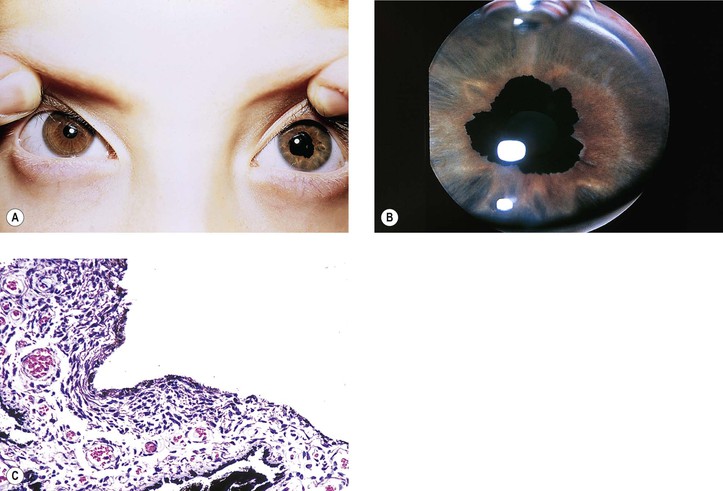

Aniridia (Hypoplasia) of the Iris

I. Complete absence of the iris, called aniridia, is exceedingly rare. In almost all cases, gonioscopy reveals a rudimentary iris in continuity with the ciliary body (i.e., iris hypoplasia; Fig. 9.6; see also Figs. 2.19 and 16.5).

II. Photophobia, nystagmus, and poor vision may be present.

III. Glaucoma is often associated with hypoplasia of the iris.

V. Aniridia may be associated with Wilms’ tumor (see section Other Congenital Anomalies in Chapter 2).

VI. The condition may be autosomal dominant or, less commonly, autosomal recessive.

VII. Histologically, only a rim of rudimentary iris tissue is seen.

Ectropion Uveae (Hyperplasia of Iris Pigment Border or Seam)

I. Two forms are found: congenital and acquired.

A. Congenital ectropion uveae (Fig. 9.7) results from a proliferation of iris pigment epithelium onto the anterior surface of the iris from the pigment border (seam or ruff), where the two layers of pigment epithelium are continuous.

2. The condition may be an isolated finding or may be associated with neurofibromatosis, facial hemihypertrophy, peripheral corneal dysgenesis, or the Prader–Willi syndrome (approximately 1% of patients with Prader–Willi syndrome, a chromosome 15q deletion syndrome, have oculocutaneous albinism).

Histologically, flattened iris pigment epithelium lines the anterior surface of the involved iris, which may show increased neovascularization.

Peripheral Dysgenesis of the Cornea and Iris

See Chapter 8.

Coloboma

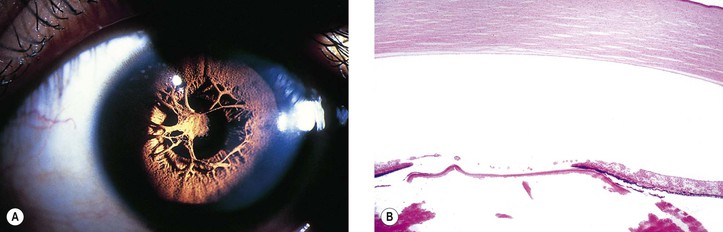

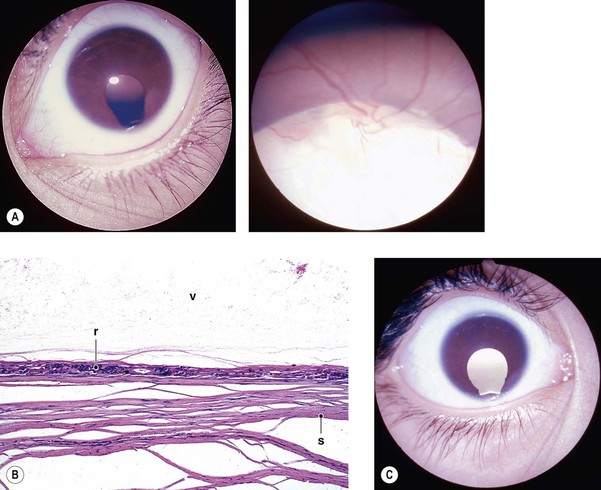

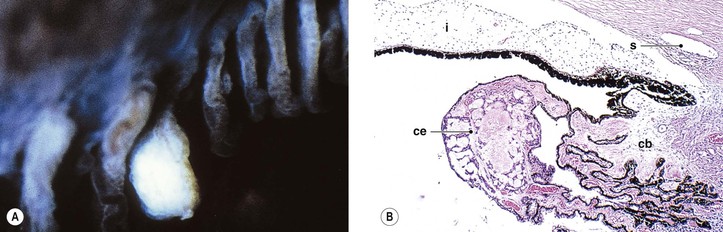

I. A coloboma (i.e., localized absence or defect) of the iris may occur alone or in association with a coloboma of the ciliary body and choroid (Fig. 9.8; see also Fig. 2.9).

A. Typical colobomas occur in the region of the embryonic cleft, inferonasally, and may be complete, incomplete (e.g., iris stromal hypoplasia; see Fig. 9.6A), or cystic in the area of the choroid.

B. Atypical colobomas occur in regions other than the inferonasal area.

II. The extent of a coloboma of the choroid varies.

A. It may be complete from the optic nerve to the ora serrata inferonasally.

III. Colobomas may occur alone or in association with other ocular anomalies.

IV. The condition may be inherited as an irregular autosomal-dominant trait.

V. Histology

A. The iris coloboma shows a complete absence of all tissue in the involved area.

C. The choroidal coloboma shows an absence or atrophy of choroid and an absence of RPE with atrophic and gliotic retina, sometimes containing rosettes.

1. The RPE tends to be hyperplastic at the edge of the defect.

Cysts of the Iris and Anterior Ciliary Body (Pars Plicata)

I. Iris stromal cysts (Figs. 9.9 and 9.10) resemble implantation iris cysts after nonsurgical or surgical trauma.

II. Iris or ciliary body epithelial cysts are associated with the nonpigmented epithelium of the ciliary body or the pigmented neuroepithelium on the posterior surface of the iris or at the pupillary margin.

Cysts of the Posterior Ciliary Body (Pars Plana)

I. Most cysts of the pars plana (Fig. 9.11) are acquired.

Inflammations

See Chapters 3 and 4.

Injuries

See Chapter 5.

Systemic Diseases

Diabetes Mellitus

See sections Iris and Ciliary Body and Choroid in Chapter 15.

Vascular Diseases

See section Vascular Diseases in Chapter 11.

Cystinosis

See Chapter 8.

Homocystinuria

See Chapter 10.

Amyloidosis

See Chapters 7 and 12.

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma (Nevoxanthoendothelioma)

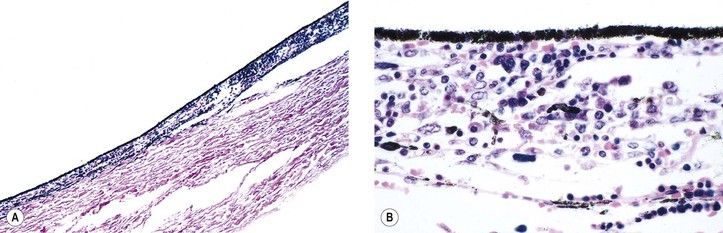

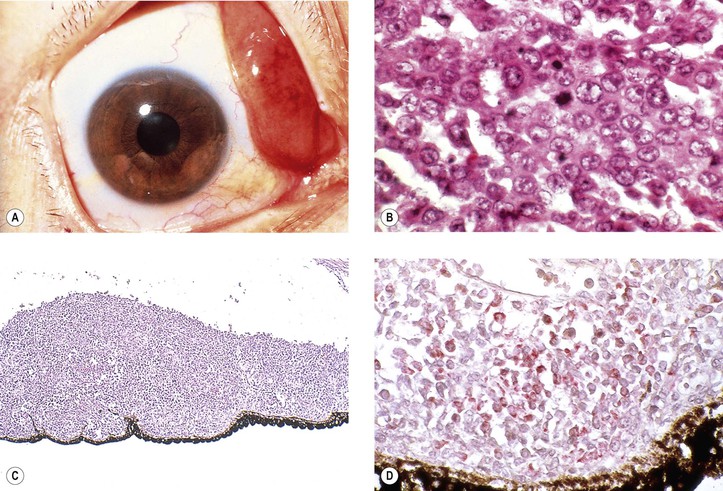

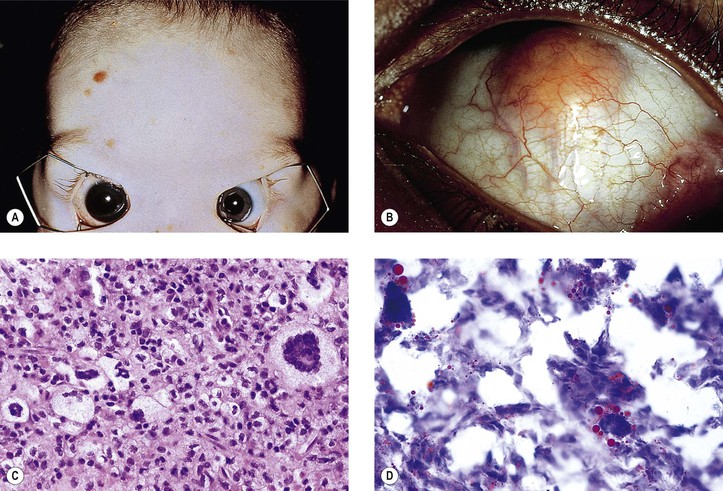

I. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG), a non-Langerhans’ cell histiocytoses (Fig. 9.12; see also Fig. 1.19), is a benign cutaneous disorder of infants and young children.

A. The typical raised orange-skin lesions occur singly or in crops and regress spontaneously.

B. The skin lesions may predate or postdate the ocular lesions or occur simultaneously.

II. Ocular findings include mainly diffuse or discrete iris involvement and occasionally ciliary body and anterior choroidal lesions, epibulbar involvement, corneal lesions, nodules on the lids, and orbital granulomas.

B. The iris lesions are quite vascular and bleed easily.

III. JXG is separate from the group of nonlipid reticuloendothelioses called Langerhans’ granulomatoses or histiocytosis X (eosinophilic granuloma, Letterer–Siwe disease, and Hand–Schüller–Christian disease; see discussion of reticuloendothelial system in subsection Primary Orbital Tumors in Chapter 14).

Langerhans’ Granulomatoses (Histiocytosis X)

See discussion of reticuloendothelial system in subsection Primary Orbital Tumors in Chapter 14.

Collagen Diseases

See subsection Collagen Diseases in Chapter 6.

Mucopolysaccharidoses

See Chapter 8.

Atrophies and Degenerations

See subsections Atrophy and Degeneration and Dystrophy in Chapter 1.

Iris Neovascularization (Rubeosis Iridis)

See Figs. 9.13 and 9.14; see also Fig. 15.5.

The term rubeosis iridis means “red iris” and should be restricted to clinical usage; iris neovascularization is the proper histopathologic term.

Choroidal Folds

Heterochromia

See subsection Heterochromia Iridis and Iridum, this chapter, and Chapter 17.

Macular Degeneration

See Chapter 11.

Dystrophies

Iris Nevus Syndrome

See Chapter 16.

Chandler’s Syndrome

See Chapter 16.

Essential Iris Atrophy

See Chapter 16.

Iridoschisis

See Chapter 16.

Choroidal Dystrophies

I. Regional choroidal dystrophies

A. Choriocapillaris atrophy involving the posterior eyegrounds

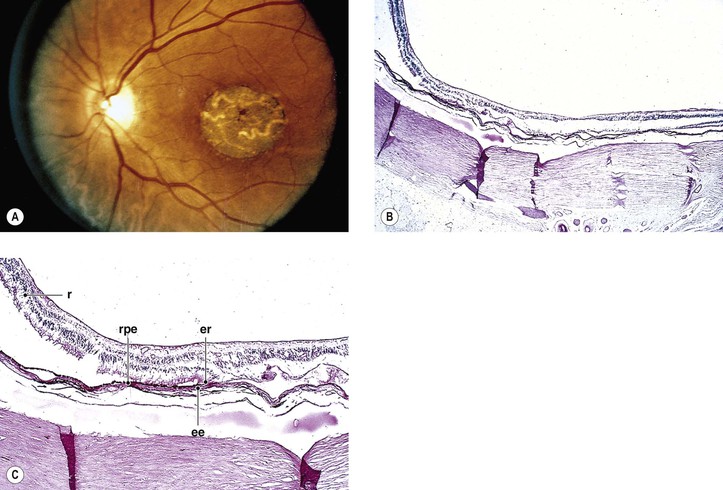

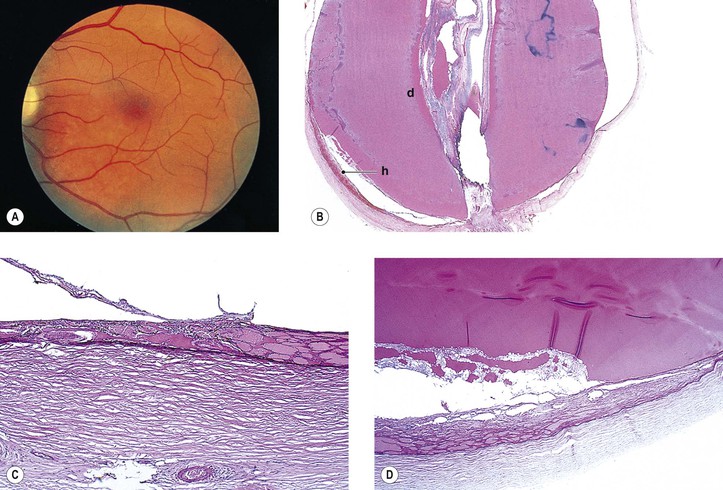

1. Involvement of the macula alone [central areolar choroidal sclerosis (Fig. 9.15), central progressive areolar choroidal dystrophy, central choroidal angiosclerosis]

2. Involvement of the peripapillary area—peripapillary choroidal sclerosis

3. Involvement of the paramacular area—also called serpiginous choroiditis or circinate choroidal sclerosis

a. The dystrophy, usually bilateral, is characterized by well-defined gray lesions seen initially at the level of the pigment epithelium, usually contiguous with or very close to the optic nerve.

1) Each new lesion remains stationary.

c. Visual acuity is only affected if the central fovea is involved in an attack.

6. Malignant myopia (see Chapter 11)

II. Diffuse choroidal dystrophies

B. Diffuse total choroidal vascular atrophy

1. Autosomal-recessive inheritance (carried on chromosome 10q26)—also called gyrate atrophy of the choroid

c. Patients have hyperornithinemia (10- to 20-fold increased ornithine concentration in plasma and other body fluids), caused by a deficiency of the mitochondrial matrix enzyme ornithine-δ-aminotransferase (OAT). They may also show subjective sensory symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.

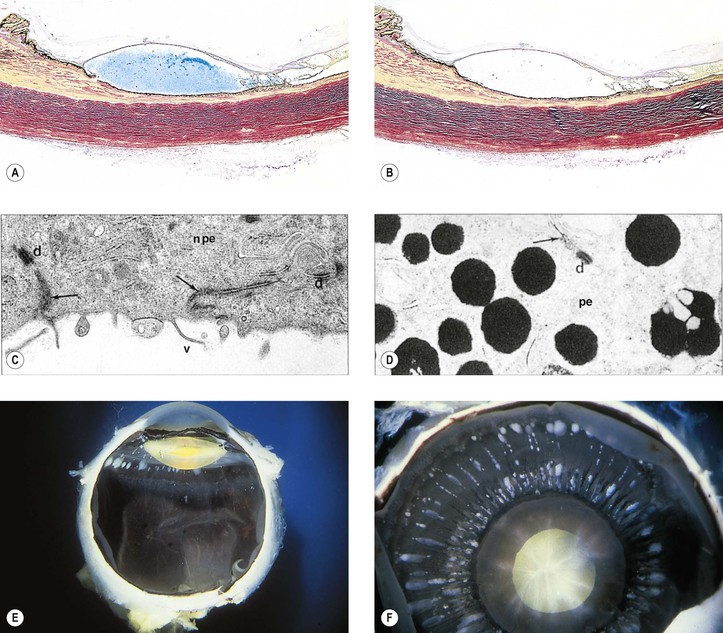

2. X-linked inheritance—also called choroideremia, progressive tapetochoroidal dystrophy, and progressive chorioretinal degeneration (Fig. 9.16)

b. The CHM gene (xq21.2) is responsible for choroideremia.

c. Component A (but not B) of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase appears to be deficient in choroideremia.

Tumors

Epithelial

I. Hyperplasias (see Chapter 1 and section Melanotic Tumors of Pigment Epithelium of Iris, Ciliary Body, and Retina in Chapter 17)

II. Benign adenoma of Fuchs (Fuchs’ reactive hyperplasia, coronal adenoma, Fuchs’ epithelioma, benign ciliary epithelioma; Fig. 9.17)

B. It may rarely cause localized occlusion of the anterior chamber angle.

C. The tumor is proliferative rather than neoplastic—that is, a hyperplasia and not an adenoma.

Muscular

I. Leiomyomas—benign smooth-muscle tumors—may rarely occur in the iris, ciliary body, or choroid.

A. Leiomyomas have a predilection for women.

B. The tumors tend to affect the ciliary body and anterior choroid.

D. Mesectodermal leiomyoma (see Chapter 14)

2. Histologically (Fig. 9.18), widely spaced tumor cell nuclei are set in a fibrillar cytoplasmic matrix and may show immunoexpression of neural markers.

E. Leiomyosarcoma has been reported as a rare iris neoplasm.

II. A rhabdomyosarcoma is an extremely rare tumor of the iris and is probably atavistic.

Vascular

I. True hemangiomas of the iris and ciliary body are extremely rare.

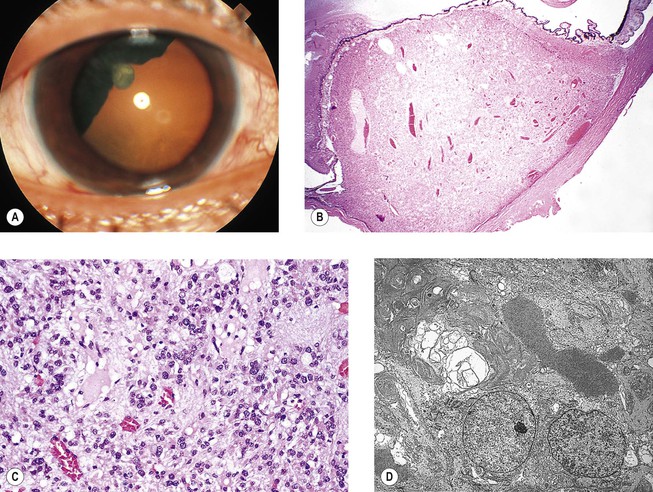

II. Hemangioma of the choroid (Fig. 9.19)

A. Hemangioma of the choroid occurs in two types: circumscribed and diffuse.

1. Circumscribed is usually solitary and not associated with any systemic process.

2. Diffuse may rarely occur as an isolated finding but mostly is part of the Sturge–Weber syndrome (see Fig. 2.2).

B. Over long intervals of observation, choroidal hemangiomas may show slight enlargement.

III. Hemangiopericytoma

A. Hemangiopericytomas are much more common in the orbit (see Chapter 14) than intraocularly.

IV. Arteriovenular (AV) malformation of the iris

A. AV iris malformation, also called racemose hemangioma, is rare.

Osseous

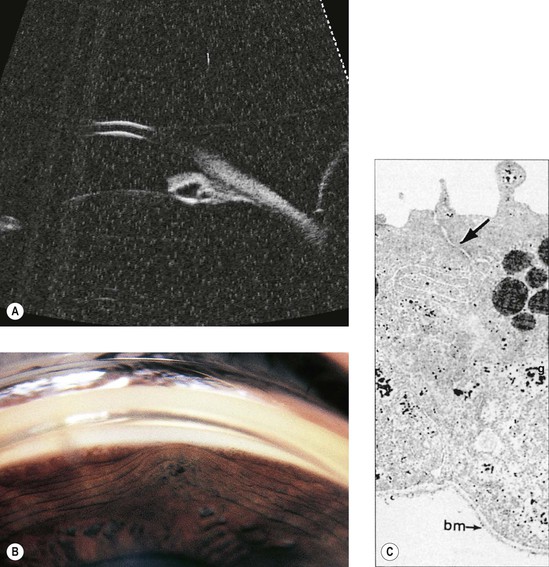

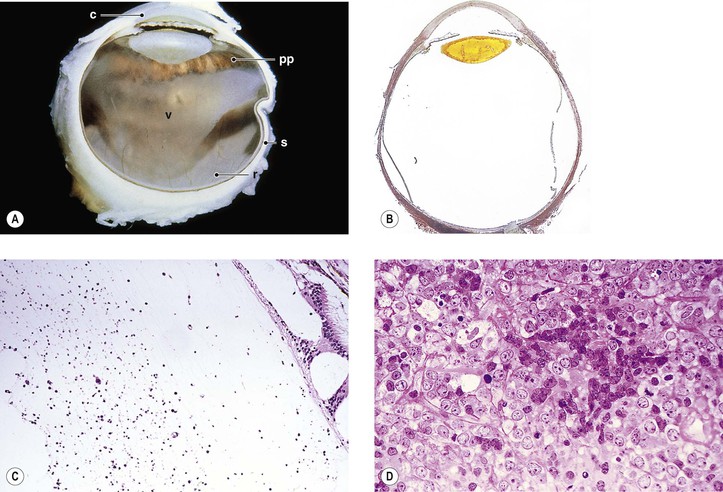

I. Choroidal osteoma (osseous choristoma of the choroid; Fig. 9.20)

A. This benign, ossifying lesion is found mainly in women in their second or third decade of life and is bilateral in approximately 25% of patients.

1. Growth may be seen in approximately 51% of cases with long-term follow-up.

B. The characteristic clinical findings include:

C. The tumor is dense ultrasonically; tissues behind the tumor are silent.

Melanomatous

See Chapter 17.

Leukemic and Lymphomatous

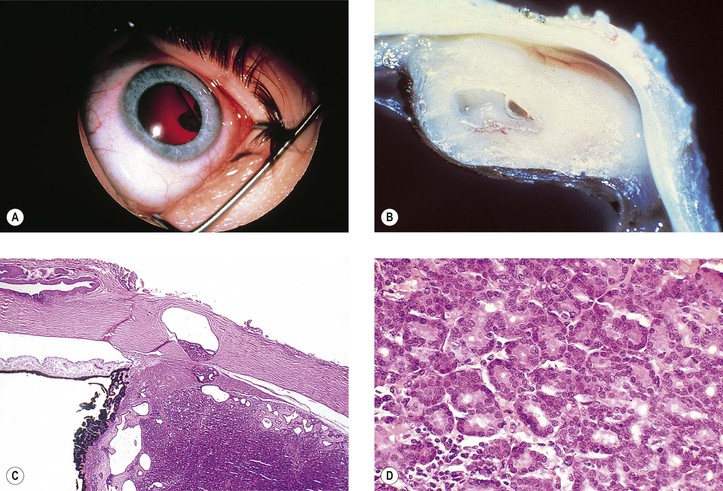

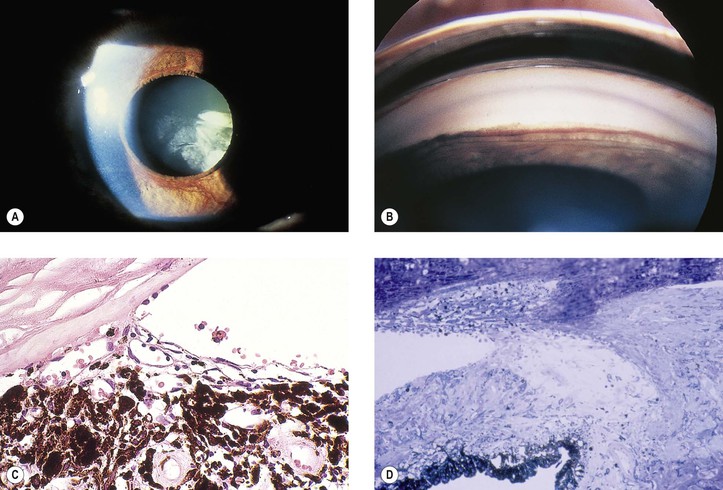

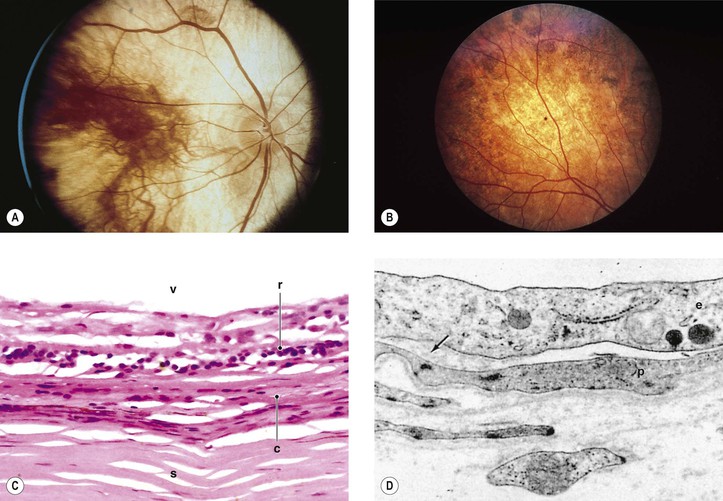

I. Acute granulocytic (myelogenous; Fig. 9.21) and lymphocytic leukemias not infrequently have uveal, usually posterior choroidal, infiltrates as part of the generalized disease.

II. Malignant lymphomas (see Chapter 14)—non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the CNS (NHL-CNS) and systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma rarely involve the eye but do so much more often than Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

A. NHL-CNS—old terms—reticulum cell sarcoma, histiocytic lymphoma, microgliomatosis

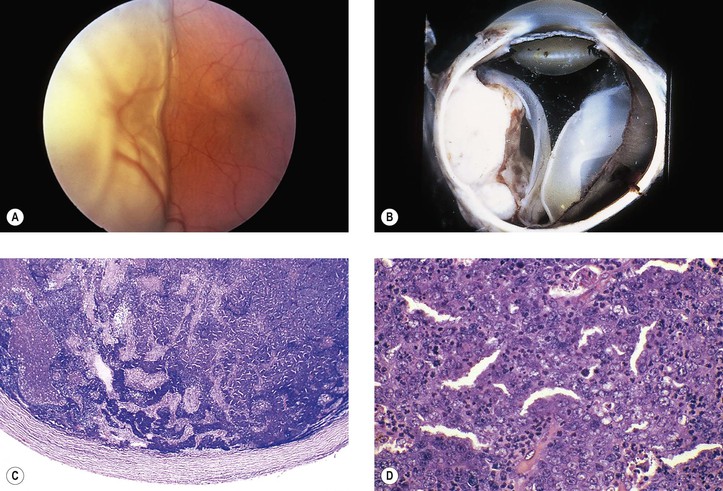

1. NHL-CNS (Fig. 9.22), usually a large B-cell lymphoma, may be associated with similar multifocal neoplastic infiltrates in the vitreous, presenting clinically as uveitis.

a. Vitreoretinal lymphoma is a rare subtype of primary CNS lymphoma.

b. The retina and choroid may also be involved (oculocerebral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma).

2. Systemic spread outside the CNS and eyes is found in only 7.5% of autopsies.

B. Systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

1. Systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma almost always arises outside the CNS.

2. Ocular involvement occurs through invasion of choroidal circulation and spreads to the choroid.

III. Occasionally, benign lymphoid infiltration (lymphoid tumor), containing lymphocytes, plasma cells, and reticulum cells, may be seen in the uveal tract.

B. They resemble the inflammatory pseudotumors, especially reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (see Chapter 14), seen in the orbit.

Other Tumors

I. Neural

A. Neurofibromas of the uvea occur as part of diffuse neurofibromatosis (see Chapter 2).

B. Neurilemmomas (see Chapter 14) and glioneuromas (see Chapter 17) are exceedingly rare tumors of the uveal tract.

II. Benign fibrous tumor is exceedingly rare.

Secondary Neoplasms

A. Squamous (or rarely basal) cell carcinoma of conjunctiva

B. Malignant melanoma of conjunctiva

D. Malignant melanoma of uvea (e.g., ciliary body melanoma extending into choroid or iris)

E. Embryonal and adult medulloepitheliomas

G. Meningioma of optic nerve sheaths

II. Metastatic—most common adult intraocular neoplasm (Fig. 9.23)

C. All other primary sites are relatively uncommon as sources of intraocular metastases.

Uveal Edema (Uveal Detachment; Uveal Hydrops)

Types

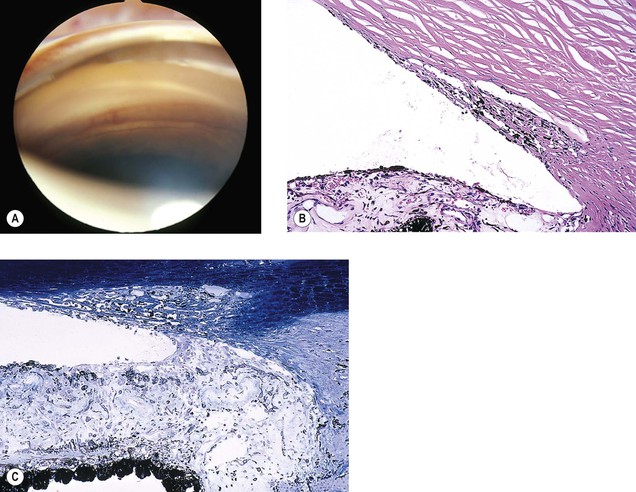

I. Uveal effusion syndrome—uveal effusion with choroidal and ciliary body detachment (spontaneous serous detachments)

II. Post-trauma—either surgical or nonsurgical trauma

B. Uveal hemorrhage may occur secondary to the trauma and result in uveal detachment.

Access the complete reference list online at ![]()