This chapter covers the common pathology of the mouth, salivary glands, oesophagus, stomach and proximal duodenum. Inflammatory conditions of this region are frequent, and include oral ulcers, oesophagitis, gastritis and gastroduodenal (peptic) ulceration. Carcinoma of the oesophagus and stomach has a particularly poor prognosis. While the incidence of gastric cancer is decreasing in the UK, oesophageal carcinoma is rising in frequency. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric pathology, and the significance of lower oesophageal epithelial metaplasia (Barrett’s oesophagus) will be discussed. Oral squamous cell cancer is relatively uncommon in the Western world but is a major health problem in India and other parts of Asia.

Part 1: Mouth and salivary glands

16.1. Inflammation and infection

The following conditions are common in the mouth:

• non-specific ulceration (‘aphthous ulcers’)

• herpes simplex type 1 infection (‘cold sore’)

• candidiasis, especially in diabetic and immunosuppressed patients

• benign fibroepithelial polyp (reactive fibrous proliferation secondary to chronic irritation)

• cysts associated with teeth (developmental or inflammatory).

The oral mucosa can manifest several inflammatory conditions seen in the skin, such as lichen planus, bullous pemphigoid and erythema multiforme. Xerostomia (dry mouth) can be a feature of autoimmune disease in Sjögren’s syndrome (see below).

Salivary gland inflammation can be due to:

• viral infection, e.g. mumps

• bacterial infection – staphylococcal and streptococcal, associated with salivary duct calculi (stones) and dehydration

• autoimmune disease.

Sjögren’s syndrome results from autoimmune inflammatory damage to the salivary glands, lacrimal glands and small mucous glands of the nasal mucosa. Clinically this can present with dry mouth and dry eyes. There is a close association between Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis.

Leucoplakia is a clinical term describing a ‘white patch’ of oral mucosa. Leucoplakia does not reflect a specific pathological diagnosis and is often caused by inflammation or reactive hyperkeratosis (thickened keratin layer), but on occasion it can represent epithelial dysplasia or malignancy (Box 22). A more sinister lesion is erythroplakia, a velvety red patch of oral mucosa, which typically shows high-grade epithelial dysplasia on biopsy.

Box 22

• Candida infection

• Smoking-related keratosis

• Traumatic keratosis from rubbing denture plate

• Lichen planus

• Squamous epithelial dysplasia

16.2. Oral and salivary gland neoplasia

Benign tumours of the oral cavity include squamous cell papilloma (analogous to skin lesions) and haemangiomas. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for over 95% of oral malignancies (Table 24).

| Incidence | Age 50–70years. Less than 5% of non-skin cancers in Western world; up to 40% of all cancers in India |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Smoking, alcohol, betel nut chewing (India/Asia), chronic infl ammation UV light and pipe smoking in lip carcinoma |

| Protective factors | Fruit and vegetable consumption |

| Associated lesions | Epithelial dysplasia, may be erythroplakia (over 50% progress to invasive cancer) or less frequently leucoplakia |

| Clinical presentation | Mass noted by patient or dentist |

| Location | Floor of mouth, tongue and hard palate most frequent |

| Macroscopic appearance | Raised fi rm mass ± ulceration |

| Histological features | Vary from well-differentiated tumours with orderly keratinisation to anaplastic (undifferentiated) tumours |

| Pattern of spread | Local infi ltration of oral structures, regional lymph nodes, lung, liver, bone |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Dependent on site: lip 90%; anterior tongue 60%; other sites 20–30% |

Salivary gland tumour pathology is complex, as both epithelial cells and associated myoepithelial cells may give rise to neoplasms. Most tumours arise in the parotid gland, and over 80% of these are benign. Neoplasms arising in the submandibular and sublingual glands and the minor salivary glands scattered throughout the oral mucosa have a much higher likelihood of being malignant (approximately 50%).

Pleomorphic adenoma

Pleomorphic adenoma is the commonest salivary tumour, arising most frequently in the parotid gland. The histological appearance is very variable, with epithelial glands or cell sheets, embedded in a connective tissue stroma showing myxoid changes, fibrosis, cartilaginous areas or even bone formation. Pleomorphic adenomas are benign tumours that appear well circumscribed macroscopically and do not infiltrate local structures (the facial nerve is, therefore, usually spared by pleomorphic adenomas arising in the parotid). However, there are often microscopic projections of tumour into the adjacent tissues, and attempted removal by enucleation carries a significant risk of multifocal recurrence, which can be difficult to treat. Up to 5% of pleomorphic adenomas may undergo malignant transformation to a high-grade carcinoma. The risk of malignant change is increased in longstanding adenomas.

Warthin’s tumour

This tumour accounts for approximately 10% of salivary neoplasms, and arises almost exclusively in the parotid. There is a strong male preponderance. Ten per cent of tumours are bilateral, and a similar number are multifocal. The microscopic appearance is distinctive, with a double layer of eosinophilic epithelial cells covering reactive lymphoid tissue. The eosinophilic cells (oncocytes) are the neoplastic population. Warthin’s tumour is benign and malignant change does not occur.

Salivary gland carcinoma

Many different histological variants of salivary gland carcinoma (Table 25) are now recognised. The two commonest are:

• Adenoid cystic carcinoma – this malignancy appears low grade on histological grounds, but is locally invasive and 50% will metastasise. The long-term survival is poor. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is composed of regular small epithelioid cells in a cribriform (‘sieve-like’) architectural pattern, associated with basement-membrane-like material. Perineural invasion by the tumour is a characteristic feature.

| Incidence | Uncommon; adults; slight female predominance |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Irradiation (muco-epidermoid carcinoma) |

| Associated lesions | Small percentage of pleomorphic adenomas undergo malignant transformation |

| Common clinical presentation | Mass, pain, facial nerve involvement (parotid tumours) |

| Location | Parotid, 15% of tumours are malignant Submandibular, 40% malignant Minor salivary glands, majority malignant |

| Macroscopic appearance | Variable, usually infi ltrative margin |

| Histological features | Variable |

| Pattern of spread | Adenoid cystic, local perineural invasion, late dissemination to lung, liver, bone, brain (50%) Muco-epidermoid, low-grade lesions recur locally, high-grade lesions may disseminate widely |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Adenoid cystic, 60% at 5years, but 15% at 15years Muco-epidermoid, 50–90%, depending on grade |

Part 2: Oesophagus, stomach and proximal duodenum

16.3. Inflammation, infection and benign conditions

Oesophagitis

This disease may be due to infection, particularly by Candida in debilitated and immunosuppressed patients. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is the commonest cause of oesophagitis in the UK, and its prevalence appears to be increasing. It is associated with sliding hiatus hernia, smoking, obesity, pregnancy and ingestion of certain foods. GORD classically presents with burning epigastric pain, which may be accentuated by bending or lying down, but is often asymptomatic. Histology shows hyperplasia of squamous oesophageal epithelium with inflammation (eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes) and ulceration in more severe cases. Complications include:

• haematemesis

• anaemia

• inflammatory stricture

• Barrett’s oesophagus (see below).

Other causes of oesophagitis include alcohol, corrosive chemical ingestion, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and graft-versus-host disease.

Barrett’s oesophagus

This syndrome describes a metaplastic change of the squamous epithelium of the lower oesophagus into glandular epithelium. The metaplastic glandular epithelium may resemble gastric or small intestinal mucosa. Barrett’s usually occurs in patients with more severe longstanding GORD. Endoscopically the metaplastic focus has a red, velvety appearance. Barrett’s may progress to glandular dysplasia and eventually to invasive adenocarcinoma. Both Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma have increased in incidence in recent years. For this reason, regular surveillance endoscopies are usually performed in patients with known Barrett’s change, to identify high-grade dysplasia and early stage malignancy. However, the degree of increased cancer risk associated with Barrett’s remains unclear, and less than half of all patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma will describe any clinical history of reflux disease.

Achalasia

This is a motility disorder in which reduced oesophageal peristalsis and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter cause lower oesophagus dilatation. Resulting symptoms include dysphagia and food regurgitation. In most cases the pathogenesis is unknown. Achalasia can be secondary to Chagas’ disease, caused by the protozoon Trypanosoma cruzi (frequent in Central America, Chagas’ disease also causes acute myocarditis and chronic dilated cardiomyopathy).

Hiatus hernia

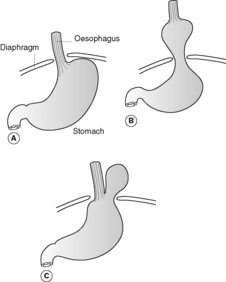

This is a common condition in which part of the stomach herniates up through the oesophageal opening of the diaphragm and into the mediastinum (Figure 41). The great majority are sliding, and are often associated with reflux oesophagitis. Rolling hernias are less common.

Oesophageal varices

Gastritis and benign ulcer disease

• Gastritis: inflammation of gastric mucosa, which may be acute or chronic.

• Gastric erosion: superficial loss of gastric mucosal tissue, not extending beyond muscularis mucosa. Erosions are associated with acute inflammation and are transient.

• Gastric ulcer: ulceration that extends through, and often well beyond, the mucosa, and may be acute or chronic.

Acute gastritis

Acute gastritis is most commonly due to:

• non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

• excess alcohol

• heavy smoking

• ‘stress’ (burns, trauma, shock) causing mucosal ischaemia

• chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Clinical consequences include haematemesis (vomiting blood), melaena (dark, altered blood in faeces), epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting.

Acute gastric ulceration

Acute gastric ulceration can also be caused by severe stress. Sepsis, shock, trauma, burns and raised intracranial pressure are the commonest predisposing factors and up to 10% of patients admitted to intensive care units will develop acute gastric erosions or ulcers. The ulcers are small (less than 10mm diameter), frequently multiple and occur anywhere in the stomach. The adjacent mucosa rarely shows chronic gastritis. Acute ulcers are transient lesions that heal with complete restoration of normal structure and without scarring.

Chronic gastritis

Chronic gastritis can be classified into three major groups:

• Autoimmune – in pernicious anaemia, with autoantibodies to gastric acid producing parietal cells in the body of the stomach.

• Bacterial – H. pylori infection (most common cause of chronic gastritis, preferentially affecting the antrum)

• Chemical – due to biliary reflux or NSAIDs.

Other causes include alcohol, smoking, Crohn’s disease and graft-versus-host disease.

Chronic mucosal inflammation can lead to intestinal metaplasia and gastric atrophy, and predisposes to development of gastric carcinoma. However, chronic gastritis and Helicobacter infection are very common, and clearly only a small percentage of those afflicted will eventually develop malignancy. Chronic gastritis itself is often asymptomatic.

Chronic peptic ulceration

Chronic peptic ulceration occurs in the gastric antrum, but is most frequent in the proximal duodenum. Lesions are usually solitary (if multiple, think of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, see below). Peptic ulcer disease is common in adulthood and more frequent in men than women. The pathogenesis of peptic ulceration involves breakdown of mucosal defence mechanisms and increased injurious stimuli. The majority of cases (especially duodenal ulcers) are associated with H. pylori chronic gastritis. Other risk factors include smoking, chronic NSAID use, liver cirrhosis, chronic lung disease, hyperparathyroidism and chronic renal failure. Significant complications of peptic ulcer include:

• haemorrhage (clinically serious in up to 33%)

• perforation with peritonitis (5%)

• gastric outlet obstruction secondary to scarring.

Malignant change does not occur in duodenal peptic ulcers and is very unusual in gastric peptic ulcers.

Recurrent peptic ulcers occur in the Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Hypersecretion of gastric acid is provoked by a gastrin-secreting tumour (usually located within the pancreas). The peptic ulcers can be multiple and arise in the stomach, proximal and distal duodenum and jejunum.

16.4. Oesophageal and gastric neoplasia

Oesophagus

Benign tumours in the oesophagus are very uncommon, but can be of epithelial (squamous cell papilloma) or of connective tissue origin (lipoma, haemangioma). The vast majority of malignant oesophageal tumours are squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas (Table 26).

| Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Over 50s; decreasing in incidence in Western world More common in men; high incidence in parts of China, Iran, former USSR |

Increasing incidence; over 40s, more common in men |

| Risk factors | Smoking, alcohol (particularly spirits), ?vitamin defi ciencies, ?food contamination – fungal organisms, nitrosamines | GORD, Barrett’s oesophagus, smoking; obesity |

| Associated lesions | Chronic oesophagitis; squamous dysplasia/carcinoma-in-situ | Barrett’s oesophagus |

| Common clinical presentation | Gradual development of dysphagia, fi rst to solids then to liquids | As for squamous cell carcinoma |

| Location | Upper third 25% Middle third 50% Lower third 25% |

Lower third of oesophagus |

| Macroscopic appearance | Polypoid usually, but can be fl at or ulcerated | Variable |

| Histological features | Squamous differentiation, with or without keratinisation | Glandular differentiation; may be histologically indistinguishable from gastric cancer |

| Pattern of spread | Local submucosal spread beyond area of grossly visible tumour, can erode locally into trachea (fi stula formation, aspiration pneumonia) or aorta (haemorrhage) Regional lymph nodes, liver and lung |

Regional lymph nodes, liver and lung |

| Prognosis (per cent 5- year survival) | 5%; often advanced stage tumour at presentation | As for squamous cell carcinoma |

Stomach

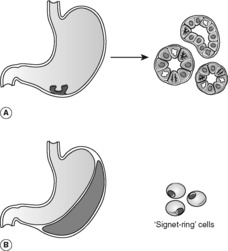

Benign epithelial neoplastic polyps (adenomas) are rare in the stomach, in contrast to the colon. Up to a third are associated with invasive carcinoma at the time of diagnosis, either within the polyp itself or in the adjacent mucosa. Gastric adenocarcinoma (Table 27) has classically been divided into two based on the histological growth patterns (Figure 42): intestinal type (with gland formation) and diffuse type (also known as ‘signet-ring’ carcinoma).

| Incidence | Geographical variation – highest in Far East, Central America, Scandinavia. Incidence of intestinal type variant has declined in UK over last 50years |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Chronic gastritis; dietary factors (nitrosamines, smoked/salted foods) |

| Protective factors | Fresh fruit and vegetable consumption |

| Associated lesions | Helicobacter gastritis, intestinal metaplasia |

| Common clinical presentation | Non-specifi c symptoms; weight loss, pain, nausea and vomiting |

| Location | Most frequent in antrum, but can occur anywhere |

| Macroscopic appearance | Polypoid, flat or ulcerated Diffuse thickening of stomach wall, ‘linitis plastica’, especially with signet-ring type |

| Histological features | Gland forming (intestinal type) or diffuse infi ltration of single adenocarcinoma cells (signet-ring type) |

| Pattern of spread | Through serosal surface; local invasion of duodenum and pancreas Regional lymph nodes (also supraclavicular node) Peritoneal spread (especially to ovaries, resulting in Krukenberg’s tumour) |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Less than 5% Early gastric cancer (confi ned to mucosa or submucosa, with or without lymph node spread) has a better prognosis |

Lymphoma

Lymphoma can arise as a primary tumour in the stomach. There is a strong association with Helicobacter infection. It seems that hyperplasia of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) induced by chronic bacterial infection provides fertile soil for development of a monoclonal neoplastic lymphoid proliferation. In contrast with lymphomas arising in lymph nodes, MALT lymphomas tend to remain localised to their site of origin and may be amenable to surgical resection. Indeed, some apparent gastric lymphomas may regress following treatment of Helicobacter infection, blurring the distinction between hyperplasia and neoplasia (recall that the latter is an uncontrolled proliferation, which does not regress when the precipitating stimulus is removed).

Self-assessment: questions

True-false questions

1. Helicobacter infection in the stomach is associated with:

a. gastric carcinoma

b. acute gastric ulceration

c. chronic duodenal ulceration

d. intestinal metaplasia

e. gastric lymphoma

2. Regarding salivary gland tumours:

a. malignant tumours arise most commonly in the parotid gland

b. pleomorphic adenomas have a 20% risk of malignant transformation

c. facial nerve impairment is an ominous sign

d. adenoid cystic carcinoma has a good long-term prognosis

e. enucleation of pleomorphic adenoma is appropriate treatment

3. Barrett’s oesophagus:

a. is a dysplastic change

b. confers an increased risk of oesophageal squamous carcinoma

c. can contain small intestinal-type epithelium

d. can be complicated by benign oesophageal stricture

e. increases in frequency with increased duration of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms

4. Oral leucoplakia (white mucosal patches) can be caused by:

a. Candida infection

b. smoking

c. epithelial dysplasia

d. ill-fitting dentures

e. invasive carcinoma

5. Concerning gastric cancer:

a. it is commoner in the UK than in Japan

b. diffuse type (signet-ring) adenocarcinoma is decreasing in incidence

c. many cancers arise from pre-existing benign peptic ulcers

d. overall 5-year survival is 25%

e. histological type is the most important prognostic factor

6. Acute gastric ulcers:

a. are often multiple

b. are common in severely ill patients

c. are usually >25mm in diameter

d. are confined to the antrum

e. usually heal without scarring

7. Concerning chronic gastritis:

a. autoantibodies to gastrin-producing cells are present in autoimmune gastritis

b. squamous metaplasia is often seen on biopsy

c. chemical gastritis can be secondary to bile reflux

d. it confers a high risk of development of gastric cancer

e. it is frequently seen in patients taking long-term steroids

8. Concerning squamous cell carcinoma of the mouth:

a. the incidence is higher in the Far East than the UK

b. prognosis is best for anterior tumours

c. there is an association with sun exposure

d. the tumour rarely spreads beyond the oral cavity

e. erythroplakia is a risk factor

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 63-year-old man presents to his general practitioner with swallowing problems. He describes gradually increasing difficulty with swallowing solid food, but no problems with liquids. He has recently lost half a stone in weight, and has a several years’ history of ‘heartburn’.

1. What is your differential diagnosis based on this history?

2. What changes might be present within oesophageal biopsies taken at endoscopy?

Case history 2

1. What specific questions would you ask the patient to help establish the cause of the ulcer?

2. Why might the endoscopist take a biopsy from the stomach (rather than the duodenal lesion)?

Viva questions

1. What are the causes and complications of acute gastritis?

2. Discuss the epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer.

Self-assessment: answers

True-false answers

1.

a. True

b. False.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True

2.

a. True. Although only 10–15% of parotid tumours are malignant, neoplasms develop more frequently at this site than in the other salivary tissues, so that salivary gland cancers are still most common in the parotid.

b. False. Less than 5%.

c. True. As it indicates tumour infiltration of the nerve.

d. False.

e. False. Microscopic residual deposits cause subsequent clinical recurrence.

3.

a. False. Barrett’s is a metaplastic change; replacement of one adult differentiated epithelium by another. Although Barrett’s itself is a benign process, there is a greater risk of developing glandular epithelial dysplasia and adenocarcinoma within the area of Barrett’s change.

b. False. It is the risk of adenocarcinoma that is increased.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True.

4.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True. Early stage invasive carcinoma may develop within a leucoplakic patch of dysplasia or carcinoma-in-situ.

5.

a. False.

b. False. It is the intestinal type of adenocarcinoma that is declining in frequency.

c. False.

d. False. It is 5%.

e. False. Surgical resectability, which is related to tumour stage, is the most important prognostic factor.

6.

a. True.

b. True.

c. False.

d. False.

e. True. Acute gastric ulcers are usually superficial.

7.

a. False. The antibodies present are against acid-producing parietal cells.

b. False. Intestinal metaplasia may be present.

c. True.

d. False. Chronic gastritis is very common, and the percentage of patients developing malignancy is low.

e. False. Steroids can cause acute ulceration if given in high doses. Chemical gastritis can be caused by NSAIDs.

8.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True. For carcinoma of the lip, which shares the same risk factors as skin cancer at other sites (see Ch. 26).

d. False.

e. True.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. The symptoms suggest oesophageal obstruction and are most likely to be due to a benign inflammatory stricture or a malignancy. The history of heartburn points to GORD. Another much less common possibility is achalasia. Dysphagia due to cerebrovascular accident is of sudden onset. Benign strictures can complicate severe oesophagitis from any cause, including physical and chemical injury (such as caustic substance ingestion, irradiation and cancer chemotherapy). Oesophageal stricture also occurs in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

2. In benign strictures, oesophageal mucosal biopsies may show inflammatory changes with squamous epithelial hyperplasia. Ulceration may be present. The fibrosis causing a benign stricture may not be seen histologically as the scar tissue lies deeper within the wall of the oesophagus and may not be sampled in a superficial biopsy. Inflammation and squamous hyperplasia would be seen in GORD. Identification of glandular epithelium within the anatomical oesophagus would signify Barrett’s metaplasia. If a malignant tumour is present, biopsy will confirm whether this is squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or a more unusual tumour type (such as sarcoma or melanoma). Even if no mass is seen, in the presence of Barrett’s oesophagus there is an increased risk of malignancy and of premalignant (dysplastic) changes in the glandular epithelium. For this reason, patients known to have Barrett’s change may undergo regular endoscopies, although the effectiveness of this surveillance in identifying early stage, potentially curable, oesophageal tumours is not yet clearly established.

Viva answers

1. Comment: See text, Section 16.3.

2. Comment: Important points to include in your answer are:

• the worldwide geographical variation in oral, gastric and oesophageal cancers

• the changing incidence of certain cancers (increasing oesophageal adenocarcinoma, decreasing intestinal-type gastric carcinoma in the UK) and possible reasons for this (increasing incidence of GORD and Barrett’s metaplasia in oesophageal adenocarcinoma; ?decreasing frequency of Helicobacter gastritis with improved general health and sanitation corresponding to reduced gastric cancer incidence)

• the role of environmental factors including smoking, alcohol and dietary habits.