9 Upper Extremity Joint Injections

Indications for Intraarticular Steroids

The most common use of corticosteroids in the peripheral joints is in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.1 These drugs are used specifically to reduce inflammation and provide relief from pain attributable to synovitis and conditions associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Other indications for the use of corticosteroids into joints include painful osteoarthritis and adhesive capsulitis. Aspiration of synovial fluid for pain relief and laboratory evaluation of the synovial fluid and arthrography for the evaluation of joints are common diagnostic tools that facilitate the rehabilitation of painful joints.

Drugs: Action, Selection, Dosage

Corticosteroids produce significant antiinflammatory effects. Numerous long-acting corticosteroid ester preparations are available. The most widely used corticosteroids include triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog), triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan), betamethasone sodium phosphate (Celestone) and betamethasone acetate (Soluspan), and methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrol).2 These compounds were developed to reduce undesirable hormonal side effects with less rapid dissipation from the joint. None of these corticosteroid derivatives appears to have any superiority over another; however, triamcinolone hexacetonide is the least water-soluble preparation and thus provides the longest duration of effectiveness within the peripheral joint space.3 Systemic absorption after peripheral joint injection occurs within 2 to 3 weeks. Improvement of inflammatory processes remote from the injection site demonstrates that intraarticular corticosteroids exert a systemic effect. The pharmacology of corticosteroids and anesthetics is discussed in Chapter 2.

The number of injections per joint is also widely variable. Commonly, joints that are injected for the purpose of reducing inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis will be injected many times over the course of the disease process. These multiple injections have been shown to cause interference with normal cartilage protein synthesis.2 However, it has also been demonstrated that patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis who do not receive intraarticular corticosteroid injections have joint disuse and decreased function much sooner than those who receive the injections.4 For the purposes of pain reduction in osteoarthritis as well as an adjunct in the mobilization of the treatment of adhesive capsulitis, injections at the rate of one per 4 to 6 weeks for a maximum of three injections is the most commonly accepted regimen. This regimen, of course, is subject to the patient’s response to his or her overall treatment plan, of which the intraarticular corticosteroid injection is but one part.

It is usual practice to combine the corticosteroid medications with an anesthetic substance, such as procaine (Novocain) or lidocaine (Xylocaine) or the equivalent. The combined use of corticosteroids and anesthetic agents provides a larger volume of injectable material with which to bathe the joint more adequately. The added effect of analgesia is also desirable for patient comfort and for a more immediate response to treatment. Thus, the patient may obtain immediate pain relief and provide valuable feedback with which to help determine the overall rehabilitation plan. The usual anesthetic injected is lidocaine, 1% without epinephrine, with which the practitioner can provide a preliminary skin wheal and a control test before proceeding with the deeper injection. Bupivacaine (Marcaine, Sensorcaine), 0.25% or 0.5%, is also useful in providing a longer-acting analgesic effect for the patient. The dosages of lidocaine and bupivacaine also vary widely with the size of the joint. Usually, the smaller joints such as the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, and elbow joints would take 1 to 2 mL of 1% lidocaine combined with the corticosteroid. The glenohumeral, knee, and hip joints would take 2-4 mL of anesthetic agent. Bupivacaine is often preferable for non–weight-bearing joints such as the shoulder, elbow, acromioclavicular, and sternoclavicular joints, so long as these joints can be somewhat immobilized for several hours. Likewise, lidocaine is the drug of choice for injections in the weight-bearing joints, such as the knee, because its duration is much shorter and, thus, the joint is subject to less postinjection trauma by the seemingly compliant patient.

Contraindications and Complications

The clinician must be acutely sensitive to contraindications and complications of intraarticular corticosteroid therapy.1,4,5,7,22,26 Some of the most obvious contraindications include infection of the joint or of the skin overlying the joint. A patient with generalized infection also should be considered an unsuitable candidate for corticosteroid injection. Injection of corticosteroids may render a joint susceptible to hematogenous seeding from more distant skin lesions. Thus, the overall health of the patient must be assessed before considering the use of intraarticular corticosteroids.6 Other obvious contraindications include hypersensitivity to any of the anesthetic preparations or the corticosteroids themselves. Patients receiving intraarticular injections in the presence of anticoagulants would be susceptible to bleeding. Determination of prothrombin time is suggested before injection therapy in these patients.

Patients with a recent injury to the joint such as a ligamentous destruction or bony destruction of the underlying joint should not be subjected to corticosteroid therapy. Instead, aspiration of the joint may be indicated if there is a relatively large inflammatory effusion.7 Soft tissue or bony tumors at or near the underlying joint would also be a major contraindication to corticosteroid injections.

Even small doses of corticosteroids with intraarticular injections may trigger episodes of hyperglycemia, glycosuria, and even electrolyte imbalance in patients with diabetes; caution must be exercised in such situations.8

Although rare, infections can be a serious complication.9,10 Usually, infections can be avoided by using an aseptic technique.11 Infections may be quite subtle in patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis and in those receiving immunosuppressive agents. The most common organism is Staphylococcus aureus.12,13 One must also use caution in geriatric patients and in those with debilitating diseases.

Hypercorticism from systemic corticosteroid therapy may be a complication if the patient receives multiple intraarticular injections in succession or if the patient is receiving concomitant oral cortisone therapy. Corticosteroid arthropathy with avascular necrosis also has been reported14 but is rare and has not been noted to occur after single corticosteroid injections. Joint capsule calcification is also a potential complication of multiple intraarticular corticosteroid injections.15

A common complication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are receiving corticosteroid injections in the joints is “postinjection flare” (the joint appears inflamed or even infected), which tends to subside spontaneously in 24 to 72 hours.16 Other less common complications include Tachon syndrome (intense dorsal spine pain immediately following an injection that quickly subsides)17 and chorioretinopathy.18

Alternatives to Corticosteroids

Alternatives to intraarticular corticosteroids include viscosupplementation and plasma-rich platelet (PRP) injections. Viscosupplementation injections use gel-like substances such as hyaluronates to supplement the viscous properties of synovial fluid and have been approved for use in the knee joint. Other joints including the shoulder have been treated with this form of injections with good results.19,20

Plasma rich platelet injections use concentrated platelets from autologous blood to stimulate a healing response in damaged tissue. Blood is drawn from the patient and placed in a centrifuge. The concentrated platelets are removed and reinjected directly into the patient’s abnormal joint, usually under ultrasound guidance. These concentrated platelets produce growth factors that include platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). These compounds are instrumental in attracting cells that promote healing by stimulating neovascularization and cellular reproduction.16,21–23 The efficacy of PRP injections and appropriate clinical indications (when and where it should be used) are currently being researched and yet to be definitively determined. Initial results of clinical studies appear promising.24–26

Techniques for Intraarticular Injections

When the clinician has established that a peripheral joint needs to be injected or aspirated, the specific preparation for the injection is essentially the same for all joints. Thorough understanding of the underlying anatomy is important to accomplish a painless injection. The optimal site for injection of the joint usually is the extensor surface at a point where the synovium is closest to the skin. Approaching the joint from the extensor surfaces allows the injection to be as remote as possible from any major arteries, veins, and nerves.27 When the site of injection has been determined, it can be marked with the needle hub or a retracted ballpoint pen by pressing the skin to produce a temporary indentation to mark the point of entry. The skin is then prepared by cleansing a generous area with a detergent or cleaner such as an iodine-based surgical scrub. This area is then painted with an antiseptic solution and allowed to dry. Aseptic technique is always advised, including the wearing of sterile gloves so that the area to be injected may be continually palpated and the anatomy appreciated throughout the procedure. A small skin wheal may then be raised using 1% lidocaine with no epinephrine (or an equivalent anesthetic agent). A 27-gauge skin needle approximately 0.75 to 1.0 inch long is used with approximately 1 mL of anesthetic agent. For joints distended with fluid or those that are particularly close to the surface of the skin, such as the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints, the raising of a skin wheal or preanesthesia is usually not necessary. If a patient is particularly apprehensive about the injection procedure, one of the vapo-coolant sprays such as dichlorotetrafluoroethane or ethyl chloride may provide adequate anesthesia.

If the joint is to be aspirated before introduction of a corticosteroid, the same technique is used in preparation; however, a larger needle may be introduced, such as a 20- or even an 18-gauge needle. Again, slow, steady pressure is used when the needle is introduced into the joint. The aspirate is then withdrawn with the practitioner gently pulling the plunger on the syringe with the dominant hand, holding the syringe barrel steady with the nondominant hand. If it is suspected that not all of the aspirate has been obtained from the joint, the needle tip may be moved around within the joint, and the joint itself may be “milked,” using steady pressure with the opposite hand on the joint itself by kneading the skin toward the site of aspiration. After all of the available fluid is aspirated, the needle may be left in place with the syringe removed. A separate syringe may then be attached to the aspirating needle, and the injectant may then be introduced into the joint itself. Again, a slow, gentle introduction of the injectable material is desired.

Upper Extremity Joints

Glenohumeral Joint

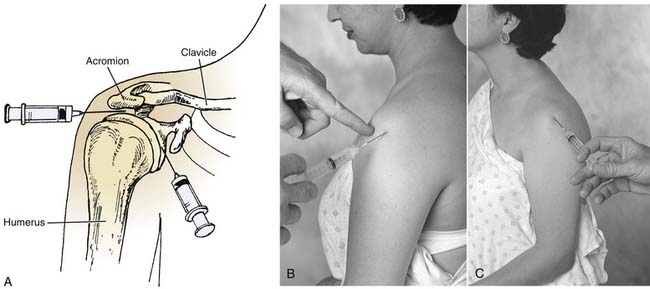

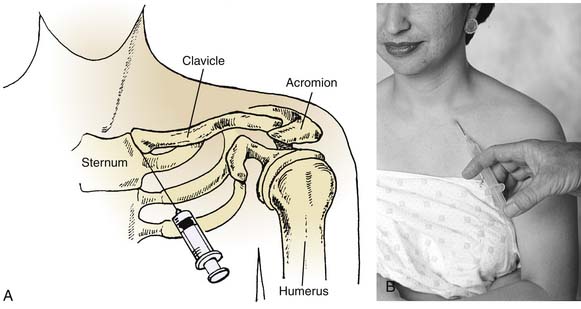

The glenohumeral joint is subject to multiple traumatic and pathologic problems more frequently than any other joint except the knee. The anatomy of the shoulder must be well understood for a relatively painless injection to be achieved.40 In entering the subacromial space in the shoulder, there is little anterior space for placement of the needle. A lateral or posterior approach may be more desirable.28

When injecting the shoulder for problems such as bicipital tendinitis, the anterior approach is necessary (Fig. 9-1). The patient is placed in a sitting position, the anterior portion of the shoulder is prepared aseptically, and, if desired, a cutaneous wheal is raised medial to the head of the humerus and just inferior to the tip of the coracoid process. It is useful to have obese patients lie supine with the forearm across the abdomen. In this position, the shoulder may be passively rotated internally and externally to identify the head of the humerus. The coracoid process is then easily palpated. The needle is directed in the anteroposterior plane just lateral to the coracoid process. The needle is advanced into the groove between the medial aspect of the humeral head and the glenoid. No resistance should be felt as the needle is advanced.

The lateral approach to injection of the shoulder is sometimes useful when treating supraspinatus tendinitis (see Fig. 9-1).28 The patient is placed in a sitting position with the arm relaxed in the lap, which increases the subacromial space. The lateral-most point of the shoulder is palpated and the needle is prepared for insertion below the acromion. After aseptic preparation, the needle is directed almost perpendicularly to the skin surface, with a slight upward angle. The space is then easily entered, and no resistance should be felt as the needle is advanced.

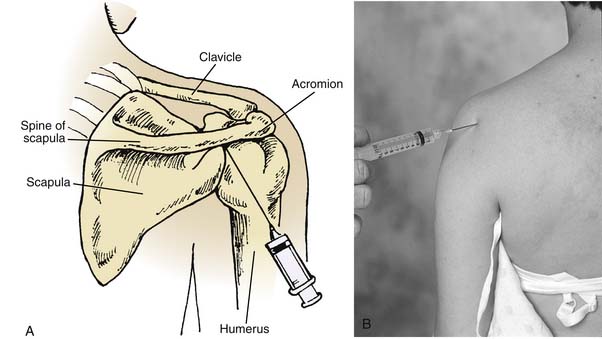

The posterior approach to the shoulder is popular for conditions such as adhesive capsulitis as well as synovitis or chronic osteoarthritis (Fig. 9-2).29 The posterior approach also allows the practitioner to be out of the patient’s vision, thereby reducing any apprehension. The patient is placed in the sitting position with his or her arm in the lap, which allows internal rotation of the shoulder and adduction of the arm. The skin is prepared aseptically, and the site of injection is palpated. The site of injection is just under the posteroinferior border of the posterolateral angle of the acromion. It is useful for the practitioner to palpate the patient’s coracoid process in the anterior portion of the shoulder with the index finger. This is the point at which the needle is “aimed.” The needle is then inserted approximately 1 inch below the posterolateral acromion process and directed from the posterolateral portion of the shoulder to the anteromedial portion of the shoulder toward the coracoid process. If resistance is encountered, the needle may be withdrawn slightly and angled upward. The needle will then be in the upper recess of the shoulder joint away from the head of the humerus.

Acromioclavicular Joint

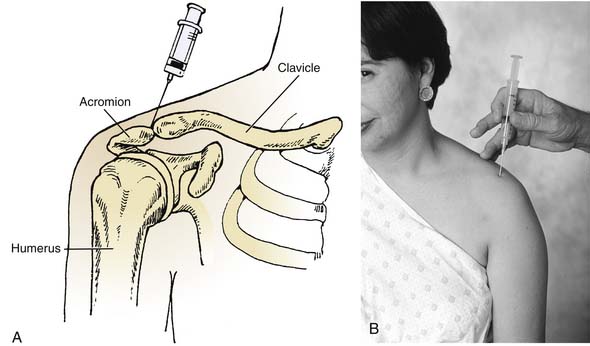

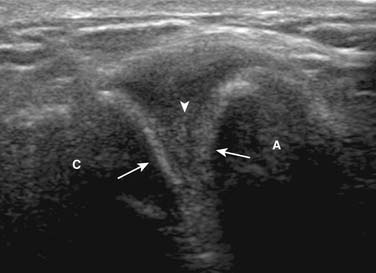

The acromioclavicular joint is small and superficial (Figs. 9-3 and 9-4). It is occasionally swollen and usually tender during palpation when inflamed. This joint can be injected easily using a 25-gauge needle with the patient sitting or supine and the shoulder propped on a pillow. Usually, injections into this joint are for chronic pain, such as occurs in shoulder separations that have not responded to noninvasive treatment.

Many times, the joint is injected for diagnostic purposes to delineate the source of pain in the shoulder, and therefore corticosteroids are not used. However, with chronic pain that does not subside after a trial of anesthetics (such as lidocaine), corticosteroids may be used.

Sternoclavicular Joint

The sternoclavicular joint is easily located just lateral to the notch of the sternum (Fig. 9-5). Many times the sternoclavicular joint is slightly dislocated, providing a source of pain and making it easily palpable because the proximal clavicle may be slightly elevated in relationship to the sternum. This joint is small and may be difficult to inject unless a 25- or 27-gauge needle is used. Great care should be taken that these injections into the sternoclavicular area are done superficially because immediately posterior to the sternoclavicular joint are the brachiocephalic veins.

Elbow

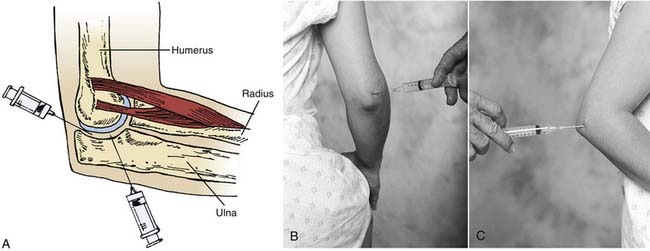

The elbow region is usually subject to periarticular problems, including lateral epicondylitis and medial epicondylitis; however, in this chapter, attention is directed to the joint space itself. Aspiration for problems such as synovitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and arthrography of the joint for delineation of multiple pathologic processes, including loose bodies, are the initial approaches to treatment.30 When it is determined that an intraarticular injection is needed, the practitioner must remember that the extensor surfaces of the joint are the safest places to avoid vessels and nerves. Thus, the injection should be directed to the posterolateral portion of the elbow or to the posterior portion of the elbow (Figs. 9-6 and 9-7). These approaches will allow the practitioner to enter the humeroulnar joint, the true elbow joint.

Figure 9-6 Drawing depicting elbow joint injections (A) and surface anatomy (B) lateral, and (C) posterior.

(From Jacobson, J, Fundamentals of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2007, p 110.)

The patient is placed with the elbow positioned between 50 and 90 degrees of flexion. The posterior and/or lateral skin surfaces are prepared aseptically. For the posterolateral approach, the lateral epicondyle area and the posterior olecranon area are palpated. The groove between the olecranon below and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus is located. The needle is then directed proximally toward the head of the radius and medially into the elbow joint. Again, no resistance should be felt when the needle enters the joint. Aspiration or injection of the joint may then be undertaken. The posterior approach to the elbow is relatively simple. The posterior olecranon is palpated with the lateral olecranon groove located just posterior to the lateral epicondyle. The needle is then inserted above the superior aspect of and lateral to the olecranon. It is advanced into the joint, and, again, no resistance should be felt.

Wrist

Many of the small joints of the wrist have interconnecting synovial spaces, making it possible to provide relief to the entire joint complex with one injection. The wrist may be infiltrated by several methods.31–33 The route of entry may be influenced by the site of inflammation or desired anatomic area. The preferred method is the dorsal approach, which may be facilitated with slight flexion of the hand. This can be easily accomplished by flexing the hand over a rolled towel. The point of entry (Fig. 9-8) is just medial to the extensor pollicis longus tendon in the distal aspect of the midpoint of the radius and ulna. This can be easily palpated as a depression between the radius and the scaphoid and lunate bones. The needle is placed perpendicular to the skin and inserted 1 to 2 cm lateral to the extensor pollicis longus tendon.32 Optional approaches to the wrist include the ulnar or the dorsal snuffbox approach. With the ulnar approach, the injection is made just distal to the lateral ulnar margin in a palpable gap between the border of the distal ulna and the carpal bones. A third approach is the dorsal aspect just medial to the anatomic snuffbox between the radius and carpal bones (Fig. 9-9). Anesthetic and corticosteroid preparations may diffuse throughout the joint and are facilitated by range-of-motion exercises following injection.7,34 The approach used should be based on the area of maximal point tenderness or site of inflammation and specific anatomic structures underlying the region to be infiltrated, such as the scapholunate ligaments or the triangular fibrocartilaginous complex. Caution should be taken to arrive at an accurate diagnosis when treating a chronic condition. An underlying wrist injury with unremarkable initial radiographs may cause scapholunate dissociation, carpal instability, or avascular necrosis. These disorders should be considered in the differential diagnosis during conservative management.

Intercarpal Joints

Injection into the intercarpal joints such as the triquetrolunate space can be accomplished by palpating the borders of the carpal bone. Palpation is easier to perform when the joint is swollen and fluctuant.33 Ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance may be necessary for precise location.

Carpometacarpal Joint

The first carpometacarpal joint or trapeziometacarpal joint is a frequent source of pain in osteoarthritis and from occupations or sports that subject the patient to undue stress. The joint may be infiltrated or aspirated from the dorsal aspect of the radial side of the carpometacarpal joint (Fig. 9-10) by holding the thumb in slight flexion and palpating for the point of maximal tenderness.14,31,35 When injecting the carpometacarpal joint, care should be taken to avoid the radial artery and the extensor pollicis tendon.36 To avoid the radial artery, the needle should be placed toward the dorsal side of the extensor pollicis brevis tendon.

Interphalangeal Joints

The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints are affected most frequently by arthritic processes. The proximal interphalangeal joint is frequently affected in rheumatoid arthritis.12,33 These smaller joints require a small-gauge needle (25- or 27-gauge) to facilitate entry. A vapo-coolant spray may be used for superficial skin anesthesia with or without a superficial skin wheal to diminish the pain on initial infiltration; infiltration of these smaller joints is painful.31 Because the joint space is very small, the tip of the needle must be advanced gently into the intraarticular capsule. The joint will accommodate only a small amount of fluid, usually less than 2 mL, and overdistention should be avoided. Pericapsular and subcutaneous injections have been known to provide some beneficial effect when direct joint infiltration could not be obtained, presumably by transport of the corticosteroids to inflamed capsule and synovium.36 The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints are infiltrated by palpating the borders of the joint and advancing a fine needle, preferably with a small syringe (2 mL) to facilitate fine motor control. Splinting the affected joint may allow resolution of an inflammatory response.37–39

Conclusion

The upper extremity peripheral joints are not difficult to inject. With practice, the clinician can become adept at entering these joints with ease, providing an effective addition to the management of peripheral joint problems. After the joints are injected, they should not be subjected to intensive exercise or motion for several days. This period of relative rest helps to promote the retention of the corticosteroid in the joint, allowing longer contact with the joint surface and delaying absorption of the drug systemically.7

1. Bloom B.J., Alario A.J., Miller L.C. Intra-articular corticosteroid therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Report of an experiential cohort and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2010 Feb 14.

2. Gray R.G., Gottlieb N.L. Intra-articular corticosteroids: An updated assessment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:235-263.

3. Bain L.S., Balch H.W., Wetherly J.M., et al. Intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide: Double-blind comparison with methylprednisolone. Br J Clin Pract. 1972;26:559-561.

4. Gordon G.V., Schumacher H.R. Electron microscopic study for depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6:7-14.

5. Perrot S., Laroche F., Poncet C., et al. Are joint and soft tissue injections painful? Results of a national French cross-sectional study of procedural pain in rheumatological practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:16.

6. Gowans J., Granieri P. Septic arthritis: Its relation to intra-articular injections of hydrocortisone acetate. N Engl J Med. 1959;261:502-504.

7. Neustadt D.H. Local corticosteroid injection therapy and soft tissue rheumatic conditions of hand and wrist. Arthritis. 1991;34:923-926.

8. Gray R.G., Gottlieb N.L. Rheumatic disorders associated with diabetes mellitus: Literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1976;6:19-34.

9. Kothari T., Reyes M.P., Brooks N., et al. Pseudomonas cepacia septic arthritis due to intra-articular injections of methylprednisolone. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116:1230-1235.

10. Rhee Y.G., Cho N.S., Kim B.H., Ha J.H. Injection-induced pyogenic arthritis of the shoulder joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1):63-67.

11. Stanley D., Conolly W.B. Iatrogenic injection injuries of the hand and upper limb. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:442-446.

12. Pfenninger J.L. Injections of joints and soft tissue: Part I. General guidelines. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:1196-1202.

13. Stefanich R.J. Intra-articular corticosteroids in treatment of osteoarthritis. Orthop Rev. 1986;15:65-71.

14. Hollander J.L. Intrasynovial corticosteroid therapy in arthritis. Md State Med J. 1970;19:62-66.

15. Hardin J.G. Jr. Controlled study of the long-term effects of “total hand” injection. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:619.

16. de Mos M., et al. Can platelet rich plasma enhance tendon repair? A cell culture study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1171-1178.

17. Hajjioui A., Nys A., Poiraudeau S., Revel M. An unusual complication of intra-articular injections of corticosteroids: Tachon syndrome. Two case reports. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007;50(9):721-723.

18. Hurvitz A.P., Hodapp K.L., Jadgchew J., et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy resulting in altered vision and color perception after glenohumeral corticosteroid injection. Orthopedics. 32(8), 2009 Aug.

19. Noel E., Hardy P., Hagena F.W., et al. Efficacy and safety of Hylan G-F20 in shoulder osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff. Open-label prospective multicenter study. Joint Bone Spine. 2009 Dec;76(6):670-673.

20. Peterson C., Hodler J. Evidence-based radiology (Part 2): Is there sufficient research to support the use of therapeutic injections into the peripheral joints? Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39(1):11-18.

21. Anitua E., Andía I., Sanchez M., et al. Autologous preparations rich in growth factors promote proliferation and induce VEGF and HGF production by human tendon cells in culture. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:281-286.

22. Menetrey J., Kasemkijwattana C., Day C.S., et al. Growth factors improve muscle healing in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 82. 2000;:131-137.

23. Yasuda K., Tomita F., Yamazaki S., et al. The effect of growth factors on biomechancical properties of the bone-patellar tendon-bone graft after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a canine model study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:870-880.

24. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 34(11):1774-1778.

25. Sanchez M., Azofra J., Anitua E., et al. Plasma rich in growth factors to treat an articular cartilage avulsion: A case report. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1648-1652.

26. Sánchez M., Anitua E., Azofra J., et al. Comparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:245-251.

27. Gray R.G., Tenenbaum J., Gottlieb N.L. Local corticosteroid injection treatment in rheumatic disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1981;10:231-254.

28. Doherty M., Hazleman B.L., Hutton C.W., et al. Rheumatology Examination and Injection Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992.

29. Jacobs L.G., Smith M.G., Khan S.A., et al. Manipulation or intra-articular steroids in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder? A prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):348-353.

30. Hudson T.M. Elbow arthrography. Radiol Clin North Am. 1981;19:227-241.

31. Leversee J.H. Aspiration of joint and soft tissue injections. Prim Care. 1986;13:579-599.

32. Pfenninger J.L. Infections of joints and soft tissues: Part II. Guidelines for specific joints. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:1690-1701.

33. Steinbrocker O., Neustadt D.H. Aspiration Injection Therapy in Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disorders: Handbook on Technique and Management. Hagerstown, Md: Harper & Row; 1972.

34. Owen D.F. Intra-articular and soft tissue aspiration injection. Clin Rheumatol Pract (Mar-May). 1986:52-63.

35. Wilke W.S., Tuggle C.J. Optimal techniques for intra-articular and peri-articular joint injections. Mod Med. 1988;56:58-72.

36. Taweepoke P., Frame J.D. Acute ischemia of the hand by accidental radial infusion of Depo-Medrone. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15:118-120.

37. Howard L.D., Pratt E.R., Punnell S. The use of compound F (hydrocortisone) in operative and nonoperative conditions of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35:994-1002.

38. Marks M., Gunther S.F. Efficacy of cortisone injection in treatment of trigger fingers and thumbs. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:722-727.

39. FaunØ P., Andersen H.J., Simonsen O. A long-term follow up of the effects of repeated corticosteroid injections for stenosing tenovaginitis. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14B:242-243.

40. Shortt C.P., Morrison W.B., Roberts C.C., et al. Shoulder, hip, and knee arthrography needle placement using fluoroscopic guidance: Practice patterns of musculoskeletal radiologists in North America. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(4):377-385.

41. Alarcon-Segovia D., Ward L.E. Marked destructive changes occurring in osteoarthritic finger joints after intra-articular injection of corticosteroids. Arthritis Rheum. 1966;9:443-463.

42. Jalava S. Periarticular calcification after intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide. Scand J Rheumatol. 1980;9:190-192.

43. Bliddal H., Terslev L., Qvistgaard E., et al. A randomized, controlled study of a single intra-articular injection of etanercept or glucocorticosteroids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35(5):341-345.

44. McCarty D.J., McCarthy G., Carrera G. Intra-articular corticosteroids possibly leading to local osteonecrosis and marrow fat-induced synovitis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1091-1094.

45. Castles J.J. Clinical pharmacology of glucocorticoids. In: McCarty D.J., Hollander J.L., editors. Arthritis and Allied Conditions. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1993:665-682.

46. Behrens F., Shepard N., Mitchell N. Alterations of rabbit articular cartilage by intra-articular injection of glucocorticoids. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57A:70-76.

47. Zuckerman J.D., Meislin R.J., Rothberg M. Injections for joint and soft tissue disorders: When and how to use them. Geriatrics. 1990;4:45-52.