8 Medicolegal Issues

Understanding Informed Consent

The law implicitly recognizes that a person has a strong interest in being free from nonconsensual invasion of bodily integrity.1 In short, the law recognizes the individual’s interest in preserving the “inviolability of the person,”1 an interest protected within the context of medical malpractice with the doctrine of informed consent. It has long been accepted that a patient must agree to any procedures or treatment. However, earlier it was accepted that the physician could steer the patient in the direction that he or she wanted. This has changed: it is now recognized that “[I]t is the prerogative of the patient, not the physician, to determine the direction in which his … interests lie.”1 Consequently, a body of law that dictates the manner in which the patient’s consent or refusal needs to be obtained has developed. Some consider the right to informed consent to be the most important aspect of patients’ rights.2

Although the vast majority of claims of medical malpractice focus on errors in diagnosis and improper treatment and performance of procedures, a recent analysis found that allegations of failure to inform and breach of warranty were present in 6% of cases.3

The Legal Framework for Informed Consent

The physician performing the procedure is the appropriate person to meet with the patient. Of course, other health care providers are of great assistance to reaffirm the consent, answer additional questions a patient may have, and continue a dialogue. To enable a patient to make an informed decision, “the physician owes to his patient the duty to disclose in a reasonable manner all significant medical information that the physician possesses or reasonably should possess that is material to an intelligent decision by the patient whether to undergo a proposed procedure.”1 The specific law varies somewhat from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Use of this language facilitates discussion of the two perspectives involved in the decision-making process: the physician and the patient.

Role of the Physician

The major role of the physician in the process of obtaining informed consent is that of an expert. Through education and experience, the physician is able to recognize the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment. Because the patient has limited knowledge of the medical and technical aspects of the procedure, the physician should begin the discussion with a reasonable explanation of the medical diagnosis—an obvious but often overlooked point. Thereafter, significant information includes the nature and probability of risks involved in the procedure, expected benefits, the irreversibility of the procedure, the available alternatives to the proposed procedure, and the likely result of no treatment.1 Whether a physician has provided appropriate information to a patient generally will be measured by what is customarily done or by the standard of what the average physician should tell a patient about a given procedure. It often is essentially the same information that the physician has imparted to countless previous patients. In general, the duty to disclose does not require the physician to disclose all possible and/or remote risks, nor does it require the physician to discuss with a patient the information that he believes the patient already has, such as the risk of infection or other inherent risks of a procedure.1

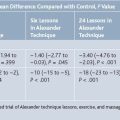

Recent studies have focused on the manner in which informed consent is obtained. For example, in a prospective, randomized, controlled study conducted by Bennet and colleagues, 99 out of 109 patients undergoing imaging-guided spinal injections agreed to particpate and were assigned to one of three groups.4 The control group was given informed consent in the customary manner at the investigators’ institution with 12 key points of consent discussed conversationally. The “teach-the-teacher” group had to repeat the 12 key points back to the investigator before informed consent could be completed. The third group viewed a set of diagrams illustrating the 12 key points before signing the informed consent. Following the procedure, all participants completed a survey to test knowledge recall, anxiety, and pain during the procedure. Statistically significant results included a lower survey score for the control group. Not surprisingly, it took significantly longer to obtain informed consent in the “teach the teacher” group than in the control group or in the diagram group. Overall, the diagram method was optimal and required less time and had improved patient-physician communication.

The manner in which information is given and how much information is offered, are both important considerations. Too much information may actually increase anxiety just prior to a procedure.5 A recent review on informed consent in Pain Practices found that although “disclosure has improved, but is still uneven, comprehension is often poor, for both patients and research subjects.”6 An important factor is not only the improvement of consent forms, but also improving the consent process. A group of Swiss researchers studied the effect of combined written and oral information versus just oral information when obtaining informed consent. In this study, participants who were given the written information as well as the oral instructions rated the quality of information they received as higher than the oral-only group.7

Role of the Patient

Although explanations to patients may be nearly identical for a given procedure, the law often also requires that the conversation be tailored to the particular patient. It is incumbent on the physician to have an appreciation of what information is important to a particular patient. The patient has the right to know all information that he or she considers material to his or her decision. Materiality is defined as the significance a specific patient attaches to the disclosed risks in deciding whether to undergo the proposed procedure.8 Materiality of information about a side effect or consequence is a function not only of the severity of that consequence, but also of the likelihood that it will occur.8 Remote risks whose likelihood of occurrence is not more than negligible need not warrant discussion. In summary, provide the patient with a realistic appreciation of his or her medical condition and an appropriate explanation of the treatments available. Never forget that however unwise his or her sense of values may be in the eyes of the medical profession, every patient has the right to forgo treatment or even cure if it entails personally intolerable consequences or risks.8

Avoiding Legal Entanglements

Lack of informed consent may develop into a lawsuit only when a physician fails to disclose a risk that subsequently becomes an injury. Otherwise, as one court stated, “an omission (of material information), however unpardonable, is legally without consequence.”9 Practically, the patient must demonstrate that, had the proper information been disclosed, he or she would not have consented to the course of therapy. To control the subjectivity of this application, some jurisdictions require the patient to prove that if the risk had been disclosed neither this patient, nor a reasonable person in this patient’s situation, would have consented.1

Requirements of Documentation

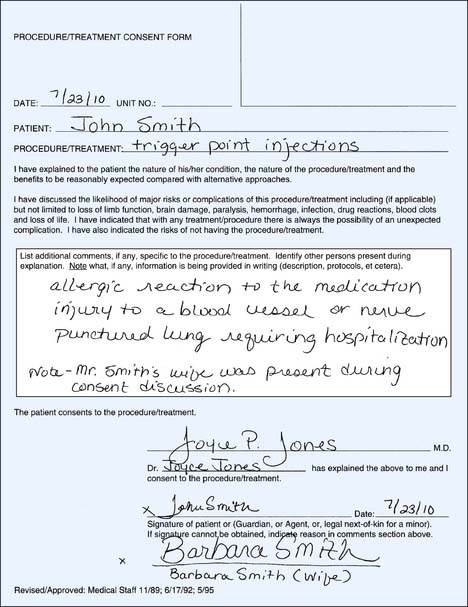

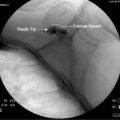

A signed form entitled “consent to treatment” is required for all procedures; note, however, that the form only proves consent, not that it was informed.10 The exchange of information that precedes the signed consent is crucial to the process. Good chart documentation (including signed consent forms, which are often and appropriately recommended by attorneys and risk managers) does not insulate a physician from a lawsuit but does make the defense of one considerably less difficult. Malpractice claims often are made years after the treatment was rendered, by which time any specific discussion with the patient in question has long since faded from memory. A standard consent form does nothing to jog the memory of the physician or the patient about the discussion; thus, it is highly important to tailor the discussion (and the subsequent documentation) for each patient, regardless of the procedure. Gone are the days when the phrase “reviewed the risks and benefits and the patient consents” was sufficient. On the standard consent form there usually is an area in which additional information may be added—savvy doctors will make pertinent notes in this body before every procedure (Fig. 8-1). For example, if trigger-point injections are to be given in the piriformis muscle, note that injury to the sciatic nerve is possible. If the injections are to be done in the region of the middle trapezius, noting that potential complications include a pneumothorax is more appropriate. Any notations on the consent form may be bolstered by further documentation in the medical record regarding the details of the discussion. In certain circumstances, it may be advisable to provide the patient with a written summary of the discussion to take home and review before the procedure.

The Role of the Doctor-Patient Relationship

In studies that have explored the relationship between physicians’ claims experience and the quality of care they provide, a common theme is that the differences between sued and never-sued physicians are not necessarily explained by their quality of care or their chart documentation. “[I]f quality of care, medical negligence, and chart documentation are not the critical factors leading to litigation, what factors are critical? Patient dissatisfaction is critical.”11 Although the law dictates what needs to be said to a patient, experience dictates that the manner in which it is said and the amount of time it takes to say it are equally important in providing good quality care and in avoiding a malpractice allegation. Effective communication between the patient and the physician not only enhances treatment outcomes but also enhances patient satisfaction. This combination tips the balance away from litigation, even in the face of unfavorable procedure outcomes.

One study found that routine visits with physicians with no malpractice claims were longer than routine visits with physicians who had experienced malpractice claims.11 This same study found that the malpractice claims were more strongly correlated with the process and tone of a discussion than the content of that discussion.

When Medical Negligence Is an Issue

By virtue of the doctor-patient relationship, a physician must exercise the degree of knowledge and skill of the average qualified physician practicing the specialty.12 Any breach of this standard that results in injury to a patient may be actionable as a medical malpractice claim. Proof of compliance with the standard of practice usually will come through a review by an expert witness, who will offer opinions based on his or her education, training, and experience in the specialty, and, in particular, in the procedure at issue. In addition, an expert opinion must be based on the facts of the case.

The medical records best demonstrate facts. It is essential to accurately and completely describe every procedure. The procedure note should contain the indications for the procedure, the details of its performance, and the patient’s reaction or initial outcome. For example, the diagnosis for a trigger-point injection may be fibromyalgia, and the indications may be to alleviate pain and muscle spasm. Symptoms and their duration and prior treatment intervention also should be documented. The following sample documentation may be useful: “Under sterile conditions using a 1-inch, 27-gauge sterile disposable needle and a solution of 2 mL 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) and 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine (Sensorcaine), a total of 6 trigger-point injections were done in the bilateral upper trapezii. A 2 mL aliquot of the mixture was used at each site. Patient tolerated the procedure well and reported immediate relief of pain in the cervical region.” Finally, follow-up plans should be clearly documented. Once again, providing the patient with a copy of the plan may be appropriate.

After analysis of the records, an expert may evaluate the physician’s proficiency with the procedure. “When a new procedure is instituted into clinical practice, proctorship and supervision by a more experienced colleague or other specialist with appropriate documentation may help establish a basis for indicating that the physician has attained the requisite degree of knowledge and skill for the procedure.”13

1. Harnish v Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 387 Mass. 152, 439 N.E.2d, 240 (1982).

2. Annas G.J. A national bill of patients’ rights. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:695-699.

3. Physician Insurers Association of America: Cumulative Data Sharing Reports, 1997.

4. Bennett D.L., Dharia C.V., Ferguson K.J., Okon A.E. Patient-physician communication: informed consent for imaging-guided spinal injections. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:38-44.

5. Yucel A., Gecici O., Emul M., et al. Effect of informed consent for intravascular contrast material on the level of anxiety: How much information should be given? Acta Radiol. 2005;46:701-707.

6. Cahana A., Hurst S.A. Voluntary informed consent in research and clinical care: An update. Pain Pract. 2008;8:446-451.

7. Felley C., Perneger T.V., Goulet I., et al. Combined written and oral information prior to gastrointestinal endoscopy compared with oral information alone: A randomized trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:22.

8. Precourt v Frederick, 395 Mass. 689, 481 N.E.2d 1144 (1985).

9. Cobbs v Grant, 8 Cal. 3d 229, 104 Cal. Rptr. 505, 502 P. 2d 1 (1972).

10. Urbanski P.K. Getting the “go ahead”: Helping patients understand informed consent. AWHONN Lifelines. 1997; 1(3):45-48.

11. Levinson W., Roter D.L., Mullooly J.P., et al. Physician-patient communication: The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553-559.

12. Brune v Belinkoff, 354 Mass. 102, 235 N.E.2d 793 (1968).

13. Brenner R.J. Interventional procedures of the breast: Medicolegal considerations. Radiology. 1995;195:611-615.