32 Tumors of the Salivary Glands

Major Salivary Gland Tumors

Anatomy

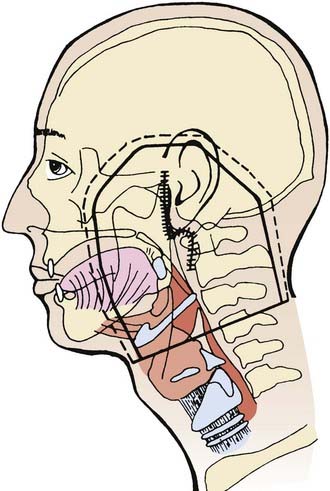

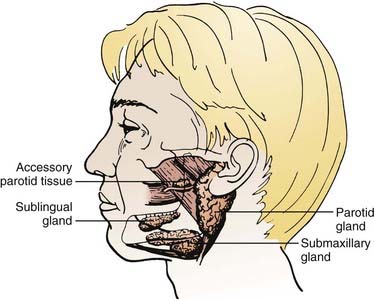

The major salivary glands comprise the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual salivary glands (Fig. 32-1). Each are paired glands that have different secretory functions: (1) parotid gland—serous; (2) submandibular gland—seromucous; (3) sublingual gland—mucous.

FIGURE 32-1 • The anatomic locations of major salivary glands: parotid, submandibular, sublingual.

(From Spiro JD, Spiro RM: Salivary tumors. In Shah J (ed): Cancer of the head and neck, London, 2001, BC Decker, p 241.)

Parotid Gland

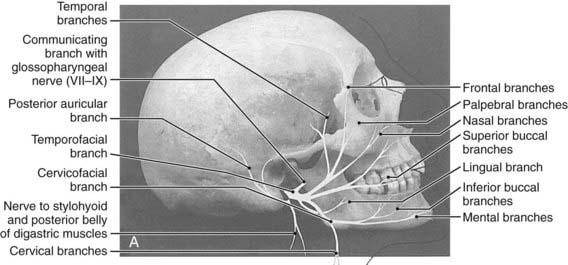

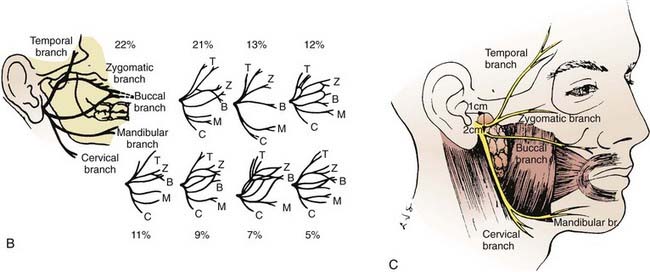

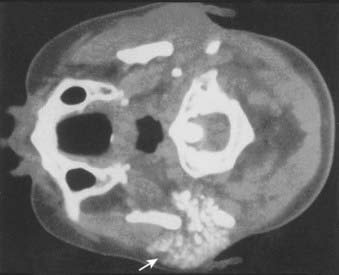

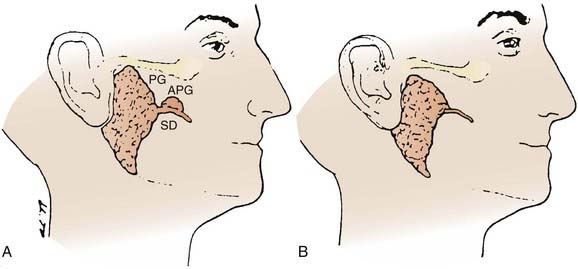

The parotid glands are the largest of the salivary glands (see Fig. 32-1 and Fig. 32-2). These paired glands are surrounded by a discrete capsule and have the following anatomic landmarks: (1) anterior—wraps around the ascending mandibular ramus anterior to the tragus and extends toward the anterior margin of the masseter muscle; (2) posterior—extends from the angle of the mandible under the earlobe toward the mastoid tip; (3) superior—extends to the inferior aspect of the zygoma at the temporomandibular joint level; (4) inferior—extends to the inferior aspect of the angle of the mandible; (5) medial—borders the parapharyngeal-base of skull; (6) lateral—located below the skin of the preauricular cheek–upper neck. The gland is divided into two lobes by the path of the facial nerve, which exits from the stylomastoid foramen (Fig. 32-3): (1) superficial lobe—accounts for 80% of the gland and is located just lateral to the facial nerve; (2) deep lobe—accounts for 20% of the gland and is located medial to the facial nerve and adjacent to the medial aspect of the angle of the mandible and is connected to the superficial lobe by the isthmus (Fig. 32-4). The deep lobe is in close anatomic proximity to the internal carotid artery; the internal jugular vein; the cervical sympathetic chain; and the cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1 The Anatomic Relationship of the Major Salivary Glands and Cranial Nerves

| Major Salivary Gland | Adjacent Cranial Nerve | Base of Skull Foramen |

|---|---|---|

| Parotid | ||

| Superficial/deep lobes | Facial nerve (CN VII) | Stylomastoid foramen |

| Deep lobe | Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) | Jugular foramen |

| Vagus nerve (CN X) | Jugular foramen | |

| Accessory nerve (CN XI) | Jugular foramen | |

| Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) | Hypoglossal canal | |

| Submandibular | Lingual nerve (CNV3) | Foramen ovale |

| Facial nerve (CN VII): | Stylomastoid foramen | |

| Mandibular/cervical branches | ||

| Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) | Hypoglossal canal | |

| Sublingual | Lingual nerve (CN V3) | Foramen ovale |

CN, Cranial nerve.

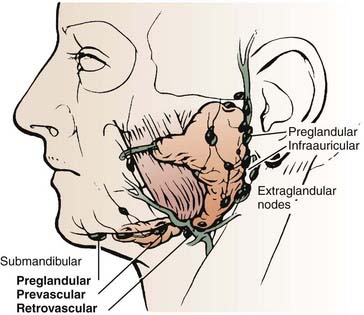

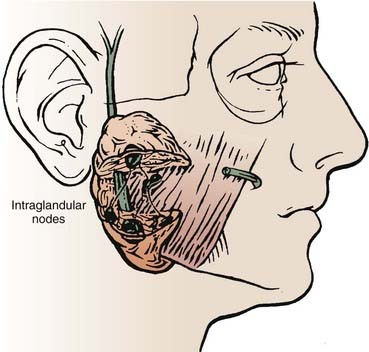

The parotid gland drains into the oral cavity through the Stensen duct (Fig. 32-5). This duct runs from the upper anterior third of the parotid gland and exits through the buccal mucosa by the second molar. The lymphatic drainage of the parotid gland progresses in an orderly fashion. Initially, it drains into the periparotid (Fig. 32-6) and intraparotid (Fig. 32-7) nodes that comprise two groups located within the fascia of the gland in two respective locations: between the gland and the superficial fascia and within the parenchyma. It then drains into the submandibular nodes (level IB), the upper (level II) and mid (level III) cervical nodes, and sometimes to the retropharyngeal nodes. Drainage to the contralateral nodes is very rare. However, it must be considered if the primary tumor extends across the midline or if there is massive ipsilateral cervical node involvement, which may disrupt the lymphatic pathways and cause spread to the opposite side.

FIGURE 32-6 • Periparotid lymph nodes are located on the surface of the superficial lobe but within the fascia.

(From Hoffman H, Funk G, Endres D: Evaluation and surgical treatment of tumors of the salivary glands. In Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, et al (eds): Comprehensive management of head and neck tumors, vol 2, Philadelphia, 1987, WB Saunders, p 1112.)

FIGURE 32-7 • Intraparotid nodes are located within the parenchyma of the gland.

(From Hoffman H, Funk G, Endres D: Evaluation and surgical treatment of tumors of the salivary glands. In Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, et al (eds): Comprehensive management of head and neck tumors, vol 2, Philadelphia, 1987, WB Saunders, p 1112.)

Occasionally, there is an accessory parotid lobe (Fig. 32-8). This lobe has been reported in 21% of normal adult cadavers.1 However, in a review of 2261 patients with parotid lesions at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between 1939 and 1978, only 23 patients (1%) had an accessory parotid gland.2 Accessory parotid glands are located either cephalad or lateral to the anterior aspect of the Stensen duct and lie over the anterior aspect of the masseter muscle but are separate from the superficial lobe of the parotid gland. Clinically, they are adjacent to the Stensen duct, which is located midway along a line drawn between the tragus of the ear to the lateral upper lip. There can be 1 to 10 tributary ducts from the accessory lobe that will empty into the Stensen duct. This lobe can be clinically significant in that it may be the primary site of a malignant tumor that presents as an asymptomatic swelling in the mid cheek region.

Submandibular Gland

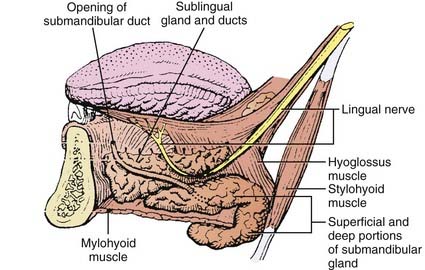

The submandibular gland (see Fig. 32-1) is 25% of the size of the parotid gland and measures 3 to 4 cm. These paired glands are surrounded by a capsule and are located in the upper anterior triangle of the neck. They are medial to the proximal half of the mandible (Fig. 32-9). The majority of the gland is over the external surface of the mylohyoid muscle, which forms the muscular floor of mouth in the region between the insertion of the muscle and the mandible and which divides the gland into contiguous superficial and deep portions (Fig. 32-10). The posterior aspect is anterior to but near the lower anterior margin of the parotid gland. The inferior aspect can extend caudad a fair distance and approaches the level of the hyoid bone. Of clinical importance is the fact that the submandibular gland is lateral to and abuts the lingual nerve (cranial nerve V3) and hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) and is medial to the marginal mandibular and cervical branches of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) (see Table 32-1).

Sublingual Gland

The paired sublingual salivary glands (see Fig. 32-1) are the smallest of the major salivary glands and are approximately 10% of the size of parotid glands. These glands do not have a discrete capsule. They are located in the anterior floor of mouth adjacent to the medial aspect of the mandible and occupy a submucosal position. Sublingual salivary glands are adjacent and superior to the mylohyoid muscle in the area of the sublingual depression. They occupy a position just medial to the inner surface of the mandible near the mental symphysis (see Fig. 32-10). It is clinically important to note that the lingual nerve (cranial nerve V3) courses adjacent to the sublingual gland (see Table 32-1).

Pathologic Conditions

Benign Tumors

Malignant Tumors

Histopathologic Types

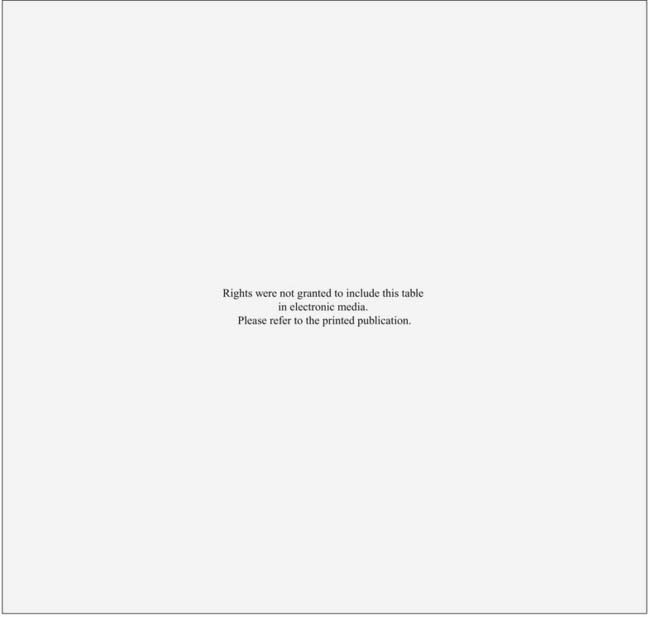

The relative incidence of the different histologic types according to gland of origin is detailed in Table 32-2.

Table 32-2 Distribution of Histologic Types of Major Salivary Gland Cancer

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Parotid (n = 1778 cases) | |

| Mucoepidermoid | 32 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 16 |

| Malignant mixed | 14 |

| Adenoid cystic | 11 |

| Acinic | 11 |

| Undifferentiated and squamous | 16 |

| Submandibular (n = 383 cases) | |

| Adenoid cystic | 41 |

| Acinic | 17 |

| Mucoepidermoid | 12 |

| Malignant mixed | 10 |

| Undifferentiated | 9 |

| Squamous | 9 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 |

Data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.1

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

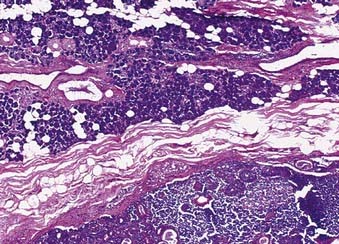

The majority of these cancers are low-grade cancers that tend to be slow-growing, well-circumscribed, and cured by surgery alone. However, some variants are high grades with an aggressive behavior. Mucin production may be absent in high-grade tumors, which are invasive and have an increased risk of spread to lymph nodes (Fig. 32-11). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common cancer of the parotid gland.3

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

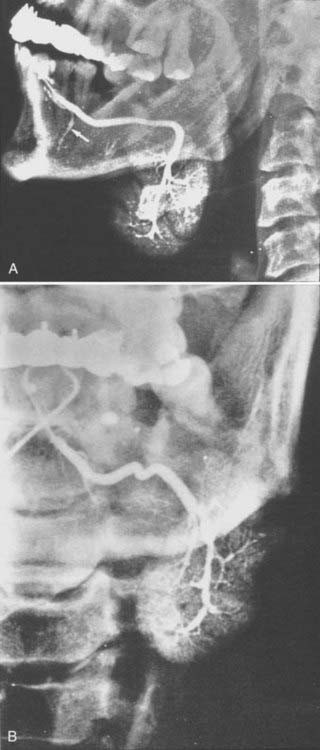

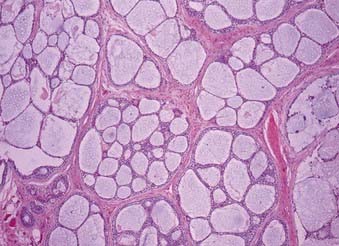

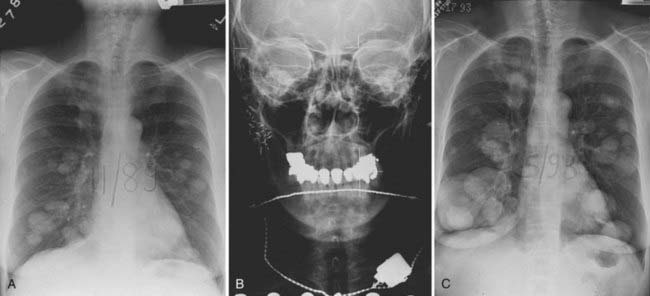

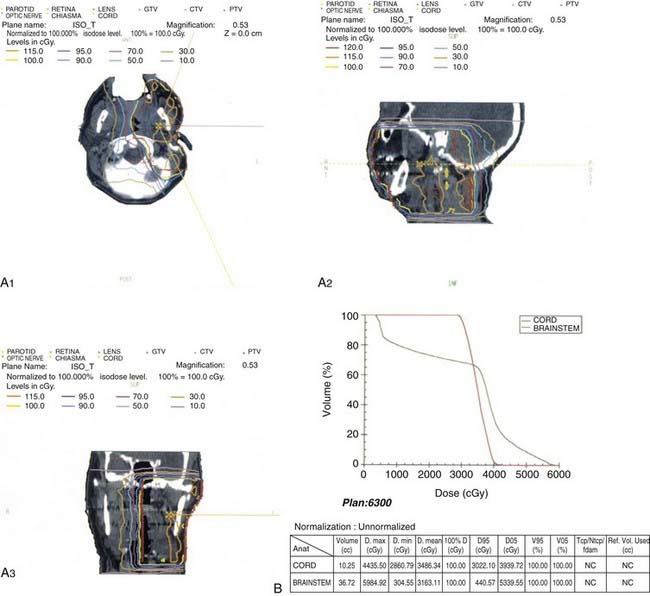

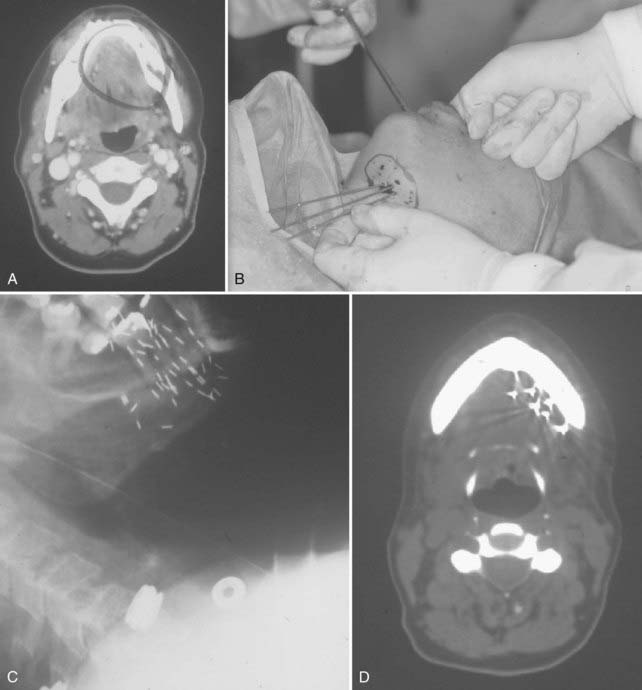

This is the predominant malignant histologic type in submandibular and minor salivary gland tumors.3 The appearance (Fig. 32-12) can vary from a cribriform pattern (differentiated) to a mixed cribriform pattern and solid features (moderately differentiated) to solid features (undifferentiated). Some authors have observed that the solid variety can have a more malignant behavior. The natural history can be varied, ranging from a matter of months to 20 years or more. The first evidence of recurrence can be 20 years after diagnosis, making it very difficult to ever determine that an individual patient is cured. Lymph node spread is distinctly uncommon (<5%). Adenoid cystic tumors can cause perineural spread, which may track along the pathways of the cranial nerves to the base of skull. This is important in planning radiation treatment. Many patients (ultimately up to 40%) will develop pulmonary metastases. Because prolonged survival can occur (10 to 20 years) with pulmonary metastases, the primary site must be managed adequately despite the presence of metastatic disease. An example of the management of the primary site in a patient with adenoid cystic cancer and lung metastases is illustrated in Fig. 32-13.

Histologic Grade

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

Parotid

Primary Site

A thorough history and carefully detailed physical examination are always crucial first steps in the evaluation of patients with a parotid mass. The differential diagnoses of a parotid mass include a malignant tumor as well as several types of benign causes (Table 32-3). Parotid malignancy is usually an asymptomatic mass. However, as the lesion progresses and enlarges, episodic pain occurs in 10% to 20% of cases; subsequently, significant pain can result and become constant. Patients can present with complaints of an inability to move one side of the face (cranial nerve VII), a shoulder (cranial nerve IX), or one side of the tongue (cranial nerve XII) as the adjacent cranial nerves become involved by the malignant tumor. Clinical presentations can vary according to the histopathologic findings (Table 32-4).

Workup with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in selected cases. Slices should cover from above the ears to below the clavicles, thus imaging the base of skull, parotid, retropharyngeal nodes, cervical nodes, and supraclavicular nodes. There are four indications for a pretreatment CT or MRI in parotid gland tumors4: (1) deep lobe parotid tumors, (2) neurologically symptomatic tumors, (3) recurrent tumors, and (4) large tumors.

In general, 75% to 80% of parotid masses are benign and 20% to 25% are malignant. An FNA biopsy is an accurate diagnostic technique with overall sensitivities of greater than 90% and specificities of greater than 95%.5–10 FNA biopsies are as accurate as frozen section analysis in parotid masses. Note that a malignant salivary gland tumor is more likely to be inaccurately diagnosed as a benign lesion than an adenoma is to be erroneously called a malignant lesion. Salivary gland lesions that are particularly associated with difficulties in achieving an accurate diagnosis include acinic cell carcinomas (false-negative confusion for a benign process), monomorphic adenomas (false-positive confusion with an adenoid cystic carcinoma), and lymphoid lesions (both false-negative and false-positive diagnoses).

Lymph Nodes

Although the overall risk (18%)11 of lymphatic spread is less common than for mucosal squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck, it is still essential to carefully evaluate the regional lymph nodes. The influence of tumor histologic features on the frequency of clinically involved nodes at presentation in 474 previously untreated major salivary gland cancers was reviewed by Armstrong from MSKCC.12 These data are presented in Table 32-5. The risk of nodal involvement increases with grade and size. However, adenoid cystic cancer, despite often being aggressive histologically and large in size, had only a 2% rate of clinically evident metastases.

Table 32-5 Clinically Involved Nodes at Presentation in Major Salivary Gland Cancers: The Influence of Tumor Histology

| Histologic Subtypes | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anaplastic | 6/7 | (86) |

| Epidermoid | 6/28 | (21) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11/49 | (22) |

| Mucoepidermoid | 30/209 | (14) |

| Malignant mixed | 11/69 | (16) |

| Acinic | 2/55 | (2) |

| Adenoid cystic | 1/55 | (2) |

| Oncocytoma | 0/2 | (0) |

| Total | 67/474 | (14) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

In the series reported by Armstrong and associates,12 overall clinically occult, pathologically positive nodes occurred in 12% (47/407). By univariate analysis, several factors appeared to predict the risk of occult metastases, but multivariate analysis revealed that only size and grade were significant risk factors. Tumors of 4 cm or more had a 20% (32/164) risk of occult metastases, compared with a 4% (9/220) risk for smaller tumors (P < 0.00001). High-grade tumors (regardless of histologic type) had a 49% (29/59) risk of occult metastases, compared with a 7% (15/221) risk for intermediate or low-grade tumors (P < 0.00001). The effects of tumor histologic anatomy and grade on occult nodal metastases are detailed in Tables 32-6 and 32-7.

Table 32-6 Effect of Tumor Histology on Occult Lymph Node Involvement in Major Salivary Gland Cancers

| Histologic Subtypes | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermoid | 9/22 | (41) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7/38 | (18) |

| Mucoepidermoid | 26/179 | (14) |

| Acinic | 2/53 | (4) |

| Adenoid cystic | 2/54 | (4) |

| Anaplastic | 1/1 | |

| Malignant mixed | 0/58 | |

| Oncocytoma | 0/2 | |

| Total | 47/407 | (12) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

Table 32-7 Effect of Tumor Grade on Occult Lymph Node Involvement in Major Salivary Gland Cancer

| Tumor Grade | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 2/125 | (2) |

| Intermediate | 13/96 | (14) |

| High | 29/59 | (49) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

It is rare for a low-grade tumor to metastasize to the regional nodes. All high-grade lesions carry a significant risk for nodal metastasis irrespective of the histologic type. High–T stage lesions are associated with an increased incidence of nodal metastasis. Submandibular or sublingual primary salivary malignancies have an increased risk for nodal spread compared with parotid salivary malignancies. The histologic type can influence the risk for nodal metastasis as well. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma are associated with a high incidence of nodal metastasis; however, adenoid cystic carcinoma, malignant mixed carcinoma, and acinic cell carcinoma have a low incidence (see Tables 32-5 and 32-6).

Distant Spread

The most likely site for distant metastasis is the lung, followed by the bones and liver. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, malignant mixed tumor, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma have a risk for distant metastases that ranges from 25% to 35%.13 Careful examination of the lungs, percussion of the bones, and palpation of the liver should be documented.

Staging

Periodically, the staging criteria are reviewed and modified to better establish a system that reflects contemporary technology and therapeutic interventions. The current AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (Table 32–8) represents the seventh edition, published in 2010.14 The following examines the changes from the sixth edition (2002)15 as they relate to major salivary gland tumors.

Lymph Node (N) Staging

There are two major groups of regional lymph nodes that can occasionally harbor metastatic disease from a parotid gland malignancy that are not specifically addressed in the AJCC cancer staging criteria. They include: (1) peirparotid and intraparotid lymph nodes; (2) ipsilateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Their estimated risk of involvement is less than 5%, yet this finding is prognostically important. Metastatic disease to these lymph nodes can be designated as N1 or N2 based on the size of enlargement and the number of lymph nodes involved.16

Treatment

Surgery

Surgical resection of the involved major salivary gland is the primary treatment of choice. However, patients must be carefully selected to ensure resectability (see “Staging”).

Parotid Gland

In selected cases in which the facial nerve has been sacrificed, it is desirable to perform an immediate cable grafting as long as there are disease-free proximal and distal branches of the facial nerve. Donor nerves include the sensory nerve branches of the cervical plexus or the sural nerves. In cases in which the proximal stump of the facial nerve is not available, the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) can be anastomosed to the remaining distal portion of the facial nerve. The functional outcome of such nerve grafts are often quite suboptimal, although it usually allows an improvement in muscle tone. It should be noted that the use of postoperative radiation therapy in these patients is not contraindicated. Radiation can begin 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively with a completely healed incision without any adverse effect on the nerve graft.17

Radiation Therapy

External-Beam Radiation Therapy

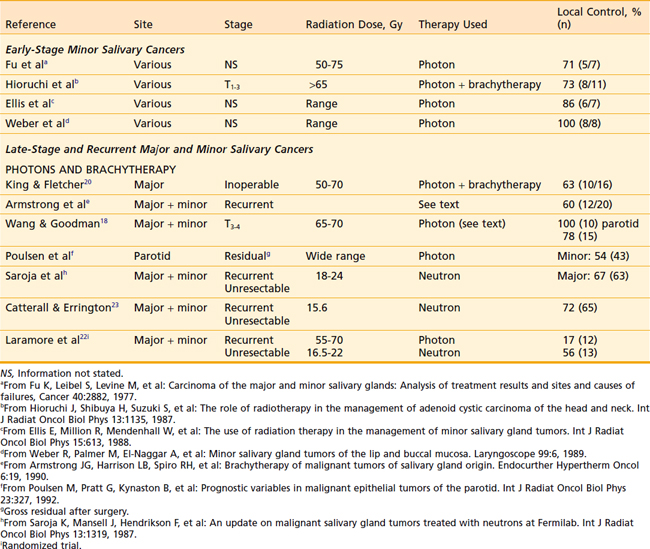

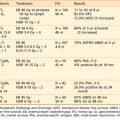

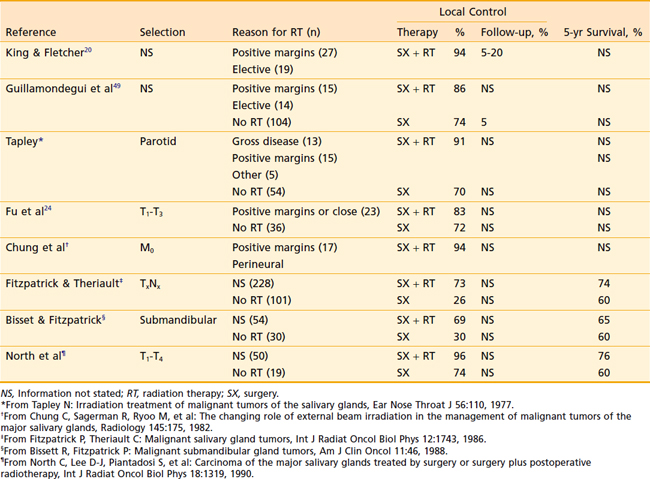

There is no evidence to indicate that unresectable malignant salivary gland tumors do not respond to conventionally fractionated photon radiation therapy. The literature contains reports of partially resected and unresected salivary gland cancers that were successfully treated in this fashion (Table 32-9) and the response rates are similar to those obtained from treating equivalent-sized squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.

The use of altered fractionation has been reported with encouraging results. Wang and Goodman18 from Massachusetts General Hospital treated 14 patients with unresectable malignant parotid carcinomas using accelerated hyperfractionation (1.60 Gy twice a day) photon therapy and various boost techniques to a total dosage of 65 to 70 cGy. The 5-year actuarial local control rate was 82% and the disease-specific survival rate was 55%.

Brachytherapy

Armstrong et al.19 reported on 20 patients with recurrent or advanced disease treated with brachytherapy alone using 192Ir or 125I. Previously, radiation therapy had been administered to 15 of these patients. The implant was to gross disease in 15 of the 20 patients. The actuarial local control rate at 5 years was 60%. Two patients had soft tissue necrosis as a complication and were treated with conservative management. However, two patients with extensive skull base tumors treated with partial surgery and 125I implants for gross residual disease had cerebral abscesses, of which one was fatal.

In unresectable cases with no prior history of radiation, combined external-beam and brachytherapy techniques have been employed. King and Fletcher20 reported on 16 such patients treated in this fashion with 10 (63%) achieving local control.

Fast Neutron Therapy

Fast neutron therapy is a specialized form of external-beam radiation. Only a few institutions in the United States have this modality, including the University of Washington in Seattle (Fig. 32-14) and Wayne State University in Detroit.

FIGURE 32-14 • Cyclotron unit delivering fast neutron therapy.

(Courtesy George E. Laramore, University of Washington.)

The therapeutic indications include treatment of primary or locally recurrent major or minor salivary gland malignancies including adenoid cystic carcinomas that have either unresectable disease or partially resected residual gross disease (Table 32-10). The results of fast neutron therapy for malignant salivary gland tumors compared with photon or electron therapy include (1) improved local-regional control, (2) no significant improvement in survival, and (3) greater grade 3 or 4 long-term toxicity with fast neutrons (10%-19%) (Table 32-11).

Table 32-10 Indications for Neutron Therapy in Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

| Primary Disease and Recurrent Disease |

Table 32-11 Results of Fast Neutron Therapy in Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

Fast neutrons are a densely ionizing, high linear energy transfer type of particulate radiation that have a limited role in clinical radiation oncology (Fig. 32-15). They are contrasted with photons in the following fashion: (1) the biologic effectiveness of fast neutrons is much less affected by a hypoxic environment; (2) the lethal effects of fast neutrons are less dependent on the cell cycle phase compared with photons; (3) the repair of sublethal damage in malignant cells matters less; (4) fast neutrons are biologically more effective (relative biologic effectiveness [RBE] > 2.6). Also, fast neutrons lack skin sparing and thus can cause a more prominent acute dermal reaction than photons.

Batterman and associates21 measured the RBE of fast neutrons to cobalt-60 for human tumors metastatic to lung. RBE was inferred by observation of growth delay. A metastatic adenoid cystic cancer had an RBE of 8 compared with 2.5 to 4 for most other tumors. This observation on limited clinical material prompted an enthusiastic evaluation of the role of neutrons for the treatment of localized salivary cancers.

Fast neutrons have a high RBE compared with photons. This does not mean, however, that they have a superior therapeutic ratio. Estimates of the exact RBE for salivary cancers are variable and it may simply be that more “radiation effect” was given with the fast neutron doses than with the photon doses. This may have had two effects—one was the increased local control, and the other was the doubling of severe late effects. In the paper from Laramore and associates,22 severe late effects were detailed comparing the two treatments. Severe late effects can be assessed by measuring the occurrence of each category of toxicity in each patient. For photons, there were 10 events in 12 categories of toxicity in 12 patients. This represents a 7% occurrence rate (10/144 = 7%). For fast neutrons, there were 26 events in 12 categories of toxicity in 13 patients, representing a 17% occurrence rate (26/156 = 17%). The outstanding question about fast neutron therapy is whether equivalent local control could be achieved with photons if the dose of photons were escalated to a point at which the toxicity was equivalent to that of fast neutron therapy.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG; United States) and the Medical Research Council (MRC; England)22 conducted a major randomized phase III multi-institutional clinical trial of the treatment of 32 patients with unresectable salivary gland tumors with either fast neutrons, photons or electrons, or both. The 10-year likelihood of local control was 56% with fast neutrons and 17% with photons and electrons. The fast neutron group had a higher incidence of distant metastasis. The overall survival was not improved with fast neutrons.

Caterall et al.23 reported on the MRC cyclotron experience of 65 patients with locally advanced or recurrent malignant salivary gland tumors, 89% of which were stage IV, who were treated with fast neutron radiotherapy. They achieved a 72% local control rate. The 5-year survival rate was 50%. The facial nerve was not damaged by fast neutron therapy.

Prott et al.24 reviewed their nonrandomized experience in treating patients with unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands using fast neutron therapy. Seventy-two patients were followed for a median of 50 months; 39.1% had a complete remission and 48.6% had a partial remission. The recurrence-free survival was 86% at 1 year, 71% at 2 years and 45% at 5 years. It was concluded that fast neutron therapy for unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland was an effective treatment.

Huber et al.25 evaluated and compared their patients with unresectable or partially resectable adenoid cystic carcinoma of major and minor salivary glands that were treated with one of the following approaches: (1) fast neutron therapy, (2) photon therapy, or (3) photon and neutron mixed-beam therapy. The 75 patients in this nonrandomized study were followed for a median of 51 months. The 5-year actuarial local control was as follows: (1) fast neutron therapy: 75%; (2) photon therapy: 32%; (3) photon and neutron mixed-beam therapy: 32%. Postoperative radiation and small tumor size were associated with high local control rates on multivariate analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival. However, those patients who were treated for primary disease and had negative nodes were associated with improved survival rate on multivariate analysis. Overall acute toxicity was comparable; but there was a higher percentage of grade 3 or 4 late toxicity with fast neutrons (19%) compared with photons (4%) or photon and neutron mixed-beam (10%) therapy. It was concluded that fast neutron therapy could be recommended for unresectable or partially resected adenoid cystic carcinomas of the salivary gland.

Douglas et al.26 reviewed their nonrandomized experience in treating patients with malignant salivary gland tumors using fast neutron therapy. Of 279 evaluable patients, 263 had gross residual disease and 16 patients had no gross disease. There were 141 patients with major salivary gland tumors and 138 patients with minor salivary gland tumors. These patients were followed for a median of 36 months. The 6-year actuarial local-regional control rate was 59%. Patients who had no gross disease enjoyed a 100% 6-year actuarial local-regional control rate. Those patients with a tumor size less than or equal to 4 cm, with no base-of-skull invasion and prior surgical resection but no prior radiation therapy had a statistically significant improvement in local-regional control on a multivariate analysis. The 6-year actuarial cause-specific survival rate was 67%. Those patients with stage I–II disease, minor salivary gland sites, no base-of-skull invasion, and primary disease had a statistically significant improvement in cause-specific survival on multivariate analysis. The 6-year actuarial freedom from metastatic disease was 64%. Those patients without lymph node involvement and no base-of-skull invasion predominated this group. The long-term rate of grade 3 or 4 toxicity was 10%. It was concluded that fast neutron therapy for malignant salivary gland tumors with gross disease resulted in good local-regional control. However, for patients with no gross disease, this treatment resulted in excellent long-term control.

Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy

The indications for postoperative radiation therapy for major salivary gland malignancies include (1) resectable primary T3-T4 and recurrent tumors, (2) unresectable or gross residual disease, (3) close or microscopically positive surgical margins, (4) deep lobe parotid tumors, (5) perineural (including facial nerve) and vascular invasion, (6) positive or close surgical margins, (7) high-grade histologic features, (8) adenoid cystic carcinoma, (9) locoregional lymph node metastasis, and (10) concern of the surgeon over the margins or conduct of the procedure (e.g., piecemeal resection, tumor spillage) irrespective of the pathology report (Table 32-12).

Table 32-12 Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Major Salivary Gland Malignancies

Spiro and colleagues27 reviewed the experience at MSKCC of 288 patients with parotid malignancies who were primarily treated with surgery (only 12 patients underwent postoperative radiation therapy). Recurrence rates by stage were as follows: (1) stage I: 7%; (2) stage II: 21%; and (3) stage III: 58%.

In comparison, Harrison and colleagues28 reported on the 5-year actuarial local control rates by T classification of MSKCC patients with major salivary gland malignancies who were treated with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy: (1) T1: 100%; (2) T2: 83%; (3) T3: 80%; (4) T4: 43%. Patients without neck node involvement had an 83% local control rate versus 58% for those with nodal metastasis.

At the University of California, San Francisco, Fu and colleagues29 reported on 35 patients with minor and major salivary gland carcinomas who had known microscopic disease at or close to the surgical margins following curative surgery. There was a 54% (7/13) recurrence rate in patients who underwent surgery alone compared with a 14% (3/22) rate for those treated with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy.

Various other retrospective reports are reported in the literature detailing the value of adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy (Table 32-13).

Table 32-13 Effect of Postoperative Radiation Therapy on Local Control and Survival in Cancer of Major Salivary Glands

The biggest criticism of these studies is that they do not accurately compare the distribution of the many prognostic factors between the surgery-alone patients and the combined-treatment group. These factors include three primary sites; a large number of histologic features; and the effect of grade, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, extent of surgery, margin status, and deep lobe involvement. To control for this large number of variables, Armstrong and associates30 performed a matched-pair analysis comparing 46 patients treated with surgery and postoperative radiation with 46 prognostically matched patients treated with surgery alone. The large population of patients treated with surgery alone at MSKCC allowed selection (without reference to outcome) of very well-matched pairs. This analysis demonstrated that outcome was excellent for stage I and II cancers treated with surgery alone. For patients with T3 and T4 tumors or nodal disease, postoperative radiation therapy significantly improved locoregional control and survival (Table 32-14). There was a trend toward improved outcome when high-grade tumors were treated with postoperative radiation. Despite the enhancement of local control with radiation, local failures occurred in 51% of stage III and IV tumors, and 37% of high-grade tumors. Harrison and associates28 reported that local failure was particularly high for T4 tumors, despite the use of surgery and postoperative radiation. This provides a rationale for adjuvant brachytherapy in selected cases. Although the data are limited for adenoid cystic cancer (Table 32-15), most authorities recommend postoperative radiation for all but the smallest tumors.

Table 32-14 Postoperative Radiation Therapy: A Matched-Pair Analysis

| Reference | Surgery, % | Surgery + Radiation, % |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I/II | ||

| 5-yr survival | 96 | 82 |

| 5-yr local control | 91 | 79 |

| Stage III/IV | ||

| 5-yr survival | 10 | 51 |

| 5-yr local control | 17 | 51 |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

Table 32-15 Effect of Postoperative Radiation Therapy on Local Control of Adenoid Cystic Cancer

| Reference | Surgery, % (n) | Surgery + Radiation, % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Fu et al26 | 30 (10) | 90 (10) |

| Matsuba et al* | 24 (19) | 60 (36) |

| Miglianico et al† | 44 (38) | 78 (43) |

* From Matsuba H, Spector G, Thawley SE, et al: Adenoid cystic salivary gland carcinoma: a histopathologic review of treatment failure patterns, Cancer 57:519, 1986.

† From Miglianico L, Eschwege F, Marandas P, et al: Cervico-facial adenoid cystic carcinoma: study of 102 cases. Influence of radiation therapy, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 13:673, 1987.

Radiation Oncology Treatment Planning

Simulation

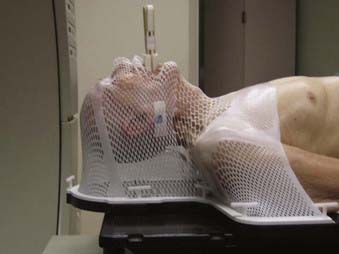

Patients undergo simulation in a supine position. The head is placed in a holder that allows hyperextension of the neck. All incisional scars and masses are wired with material appropriate for visualization on regular fluoroscopic simulation films or on the CT scans, depending on which unit is used. A bite block is employed for patients with tumors of the submandibular or sublingual glands; however, it is usually unnecessary for parotid gland tumors. A customized thermoplastic face mask (Fig. 32-16 and Fig. 32-17) or extended head and shoulder immobilizaton unit is created for immobilization and consistency of the head and neck position throughout treatment. A shoulder pull board is employed to bring the shoulder maximally in a caudad direction, particularly when the neck nodes are treated.

FIGURE 32-16 • Customized thermoplastic immobilization face mask and bite block in preparation for computed tomography simulation.

At this time, the patient undergoes a fluoroscopically assisted simulation or a CT simulation, depending on whether they will be treated with a two-dimensional or three-dimensional conformal or intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) treatment plan.31

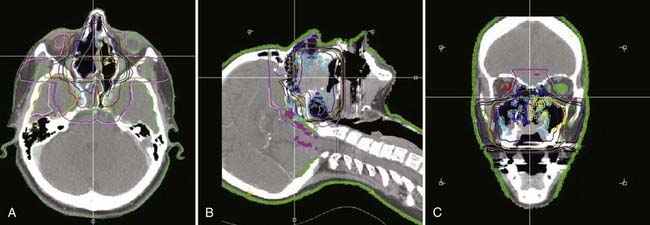

For the patients who undergo a CT simulation (Fig. 32-18), the area within the superior and inferior borders of the field, which includes the treatment volume, are scanned using 3-mm slices. No intravenous contrast is needed. The radiation oncologist then selects the isocenter location on the CT scan, which is then marked on the patient with a permanent tattoo.

Computer Treatment Planning

The computer data from the CT simulation is downloaded from the CT simulator and transferred to treatment planning computers. The clinical target volume, which represents the visualized tumor (gross target volume) and regions at risk for microscopic disease, such as adjacent tissues or lymph nodes as well as the important adjacent normal structures including the spinal cord, brainstem, optic nerves and chiasm, orbits, cochlea, and the contralateral parotid gland are contoured. When contouring the postoperative surgical bed, the remaining intact contralateral salivary gland is used as an anatomic reference point. A generous margin around the anatomic region of at least 2 cm should be considered to cover the entire operative bed with sufficient borders. For patients who have adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland, the usual approach is to irradiate the pathways of the adjacent cranial nerve up to the base of the skull. The detailed and complex pathways of the cranial nerve must be carefully and accurately contoured. LeBlanc32 has correlated gross anatomic information with associated CT axial images delineating these pathways. The regional lymph node areas require contouring in specific instances, as noted earlier. Several excellent references are available that explore the anatomic region of the respective surgical lymph node group levels (I to VI) with respect to their location on axial CT slices. Nowak et al.33 correlated the borders of the surgical levels in the neck (I to VI) with structures seen on a CT scan. They defined the six cervical lymph node regions and noted their respective reproducible landmarks on the CT scan. Wijers et al.34 presented a more simplified approach for delineating cervical nodal target volume based on CT scans. Chao et al.35 published guidelines for target volume determination of head and neck lymph nodes. This was based on their analysis of lymph node failure in IMRT-treated patients. The Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, the Groupe d’Oncologie Radiothérapie Tête Et Cou, and the RTOG consensus guidelines give a very nicely detailed color atlas of CT-based delineation of lymph node levels in the N0 neck (www.rtog.org.).

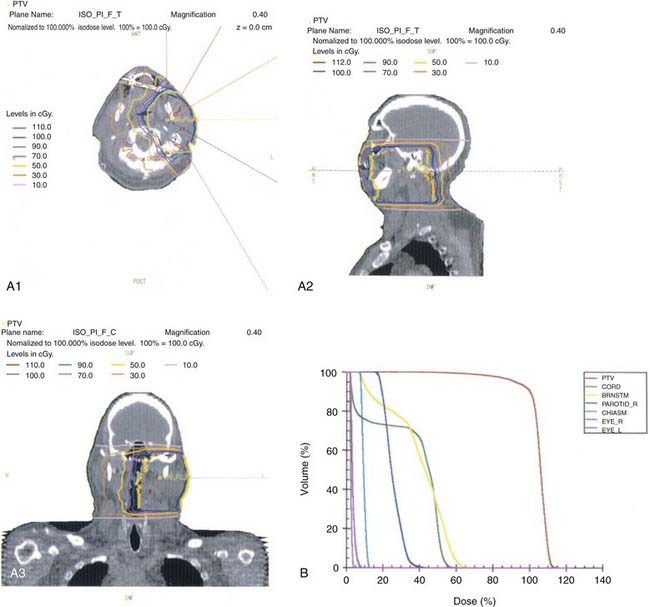

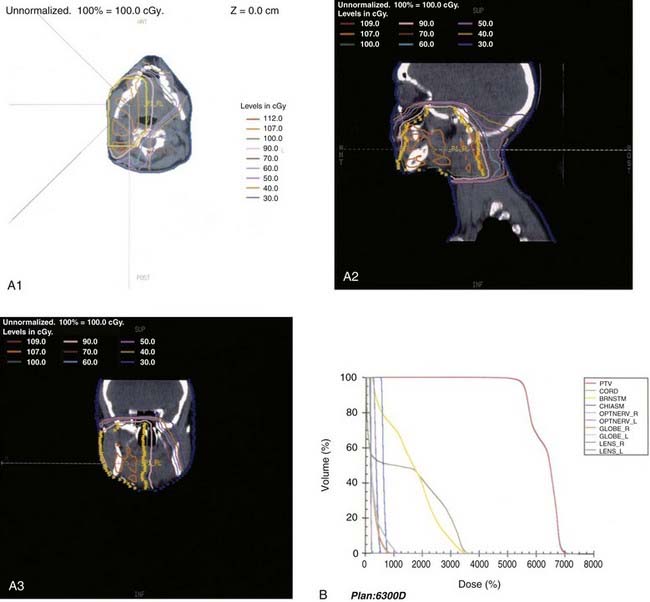

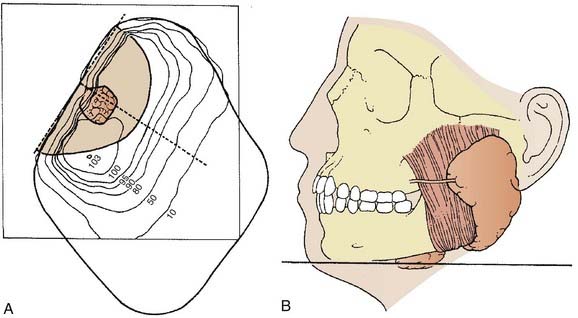

This anatomic data is then used for computer-based complex treatment planning employing the three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) or IMRT technique, whichever is most appropriate. A thorough discussion between the radiation oncologist and dosimetry staff is held to outline the disease status, treatment goals, areas of concern, and dosage planned. The resulting isodose curves, dose-volume histograms for the tumor area as well as the adjacent critical structures, and the digitally reconstructed radiographs are carefully evaluated (Fig. 32-19, Fig. 32-20, and Fig. 32-21).

Radiation Therapy Techniques

Parotid Gland Tumors

Primary Site

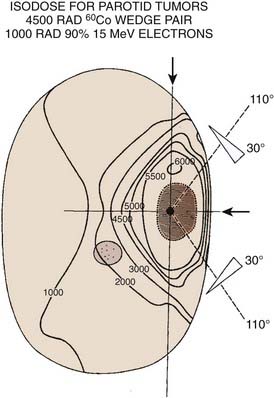

Radiation therapy approaches include (1) electrons—lateral en face electron beam (Fig. 32-22), (2) combination of electrons and photons (50% to 80% weighting toward electrons)—lateral en face electron beam and photons using a direct lateral field or a wedge-pair technique, and (3) photons—wedge pair using 3D-CRT or IMRT approach (see Figs. 32-19 through 32-21).

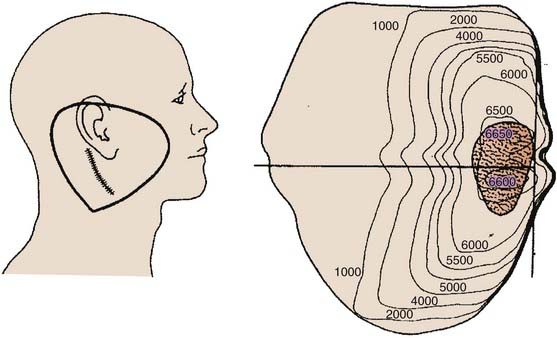

The most frequently used techniques have been with a combination of electrons and photons as a so-called mixed beam (Fig. 32-23) or photons alone using a wedge pair (Fig 32-24). Electrons are delivered with a direct lateral en face approach covering the tumor (parotid gland) or tumor bed with a 2- to 3-cm margin (Fig. 32-25).

FIGURE 32-23 • Transverse image of a parotid gland mixed beam (photon and electron) therapy isodose distribution.

(From Perez CA, Brady LW, eds: Principles and practice of radiation oncology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1998, Lippincott-Raven, p 970.)

FIGURE 32-24 • Transverse image of a parotid gland wedge pair photon beam therapy isodose distribution.

(From Wang CC: Radiation therapy for head and neck neoplasms, ed 3, New York, 1997, Wiley-Liss, p 317.)

Side Effects

Critical Normal Tissues: Radiation Injury

Dose-Limiting Tissues

The dose-limiting tissues are the mandible, brain, spinal cord, cochlea eyes, and salivary tissue.

Tolerance Doses and Fractionation

Loss of salivary function is usually complete and permanent after doses of 35 Gy in conventional fractionation. Marks and associates36 noted that only one-fifth of patients who received between 40 and 60 Gy had any measurable salivary flow after salivary stimulation. Young patients have better chances of recovery of some salivary function, and the higher the rate of pretreatment salivary flow, the greater the chance of recovery.37

Acute and Late Side Effects

Xerostomia

Acute xerostomia occur for most patients by the third to fourth week of treatment and usually becomes more prominent throughout the remaining course of radiation therapy, even with maximum sparing of the contralateral salivary glands, particularly during treatment for parotid gland tumors. With the use of 3D-CRT or IMRT, the contralateral and other salivary glands can be spared by limiting the total dosage to 26 Gy, which allows for a high incidence of substantive salivary recovery in the months following completion of radiation therapy.31

Induction of Malignancy

This is clearly a potential late complication from radiation therapy that can occur whenever a patient receives such treatment anywhere on the body. The latent period is approximately 13.3 years. Available data specific to the salivary gland are obtained from atomic bomb survivors and from patients who received radiation for benign conditions. Although the quality of such information is questionable with respect to its usefulness in associating radiation as an causal agent for the development of salivary gland malignancies, it is clear that children who received low-dose radiation for benign conditions such as thymic enlargement, tinea capitis, or infected tonsils have an increased incidence of such tumors. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma have been reported as the two most common types of malignant salivary gland tumors induced by radiation.38 In survivors of the atomic bomb, there was a fivefold greater incidence of salivary neoplasia than that expected in a normal population.39 Besides salivary gland malignancies that could be induced by radiation, the other tissues within the treatment volume also can potentially develop a malignancy such as bone, soft tissue sarcomas, or both; however, the incidence is similarly very rare.

Chemotherapy

Treatment with chemotherapy has response rates between 40% and 50%40–42 with duration of responses ranging from 5 to 8 months.43,44 Active single agents include doxorubicin, CAP, paclitaxel, hydroxyurea, bleomycin, and 5-fluorouracil. However, single-agent therapy has limited activity against malignant salivary gland tumors. The best response rates are associated with combination chemotherapeutic regimens such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and CAP, for which response rates have been between 22% and 100%. Complete response rates of 0% to 40% have been reported for combination chemotherapy.

Special Cases

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (Cylindroma)

There is a 50% incidence of microscopic perineural invasion, particularly of the adjacent cranial nerves. Perineural spread can be associated with skip areas of involvement and therefore one cannot be comfortable with negative neural margins on frozen section. Thus, postoperative radiation therapy of the entire pathway of the adjacent cranial nerve to the base of the skull is employed. The resultant base-of-skull failure from perineural invasion and extension of adenoid cystic carcinoma is associated with significant morbidity and is very difficult to treat effectively. Garden et al.45 found that the base-of-skull failure was rare whether or not elective radiation was given to the skull base. The policy at MSKCC, however, is to irradiate the adjacent cranial nerve pathway to the base of the skull in all patients who have adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland (see Fig. 32-20).

Spiro and Huvos reviewed the MSKCC experience of 184 previously untreated patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the minor and major salivary glands.46 Of these, 63% were stage I or II, 43% stage III, and 21% stage IV. Sixty-eight percent were grade 1 (cribriform pattern only), 26% were grade 2 (mixed cribriform pattern and solid features), and only 5% were grade 3 (solid only). All patients were treated with surgery but relatively few received postoperative radiation therapy. The cumulative 10-year survival rate was as follows: (1) stage I/II, 75%; (2) stage III, 43%; and (3) stage IV, 15%. The cause-specific survival at 10 years was 94% for stage I. They arrived at two important conclusions: (1) The clinical stage was the only factor that had significant effect on survival, and (2) the tumor grade alone was not predictive of survival, regional nodal metastasis, or distant metastasis. Surgery alone has been associated with a local control rate of 25% to 40%; however, when postoperative radiation therapy is employed, local control rates increase 75% to 80%.

Adenoid cystic carcinomas can have a natural history of several years even when presenting with metastatic disease. Consideration of controlling the primary tumor is prudent (see Fig. 32-13).

Recurrent Major Salivary Gland Cancers

Armstrong and associates47 reviewed the experience at MSKCC of recurrent major salivary gland malignancies in 78 patients who underwent resection of locally confined recurrent major salivary gland cancers. Thirty-eight patients had completely resected tumors, with low- or intermediate-grade histologic anatomy, without lymph node spread, and the cause-specific survival rate was 83% at 5 years, 70% at 10 years, and 48% at 15 years. Local control for these 38 patients was superior for those with tumors of 3 cm or less compared with those with larger tumors: 80% versus 62% at 5 years, and 73% versus 25% at 10 years (P < 0.05).

However, another study by Spiro and Spiro at MSKCC reviewed the results of attempted salvage of patients developing locally confined recurrences following initial therapy of their primary tumor.48 Between 1966 and 1982, 155 patients presented with locally confined new primary carcinomas and were treated surgically with or without radiation therapy.48 Of the latter group, local failure occurred in 15% (23/155) and only 7 of the 23 were suitable for salvage surgical therapy. All but one of the seven died of their disease, with an actuarial survival rate of only 21% 5 years after recurrence.48a In an attempt to explain this discrepancy, it has been postulated that the extent or completeness of therapy administered at the time of the initial diagnosis, before the development of a recurrence, may be an important predictor of the success of management of locally recurrent salivary cancer. The mechanisms of local recurrence following minimal or inadequate initial therapy may differ from the mechanisms of recurrence following aggressive initial therapy. The former may be related to technical factors, whereas the latter may be a manifestation of biologic aggressiveness.

Few other data address the role of postoperative conventional external-beam radiotherapy in the management of recurrent tumors of the major salivary glands. Guillamondejui and associates49 from the MD Anderson Hospital treated 12 patients with surgery or radiotherapy or both for locoregional recurrences. Locoregional control was achieved in 42% (5/12). In contrast, King and Fletcher,50 from the same institution, reported a crude locoregional control rate of 81% (25/31), with minimum follow-up of 2 years, among patients presenting with postoperative local recurrences treated with radiotherapy. Tu and associates,51 from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, reported a significant survival advantage with the use of postoperative radiotherapy for recurrent parotid cancers. At 5 years, 89% of the patients (17/19) were alive in the combined-therapy arm compared with 59% (10/17) in the surgery-alone arm.52 This paper did not compare prognostic factors between the two groups, nor did it detail the patterns of treatment failure. In addition, as the numbers of patients were small, it is difficult to make firm conclusions as to the efficacy of postoperative radiation therapy.

Armstrong and associates reported on 20 patients with recurrent19 or advanced12 disease who were treated with 192Ir and 125I brachytherapy as described earlier.19 Previous radiation therapy had been administered to 15 patients. The implant was to gross disease in 15 of the 20 patients. Actuarial local control was 60% at 5 years. Two patients had soft tissue necrosis as a complication, which was resolved with conservative management. There were two cerebral abscesses, one of which was fatal. Both patients had extensive skull-base tumors treated with partial resection and 125I brachytherapy for gross residual disease.

Brachytherapy can be used in conjunction with resection if the resection margins are close or positive, or in the presence of a T4 tumor. It may also be used as sole treatment of accessible localized recurrent disease previously treated with radiation therapy. Permanent 125I seeds can be implanted directly into the tumor or embedded in a synthetic absorbable suture and sewn into tumor beds. The typical matched peripheral dose for 125I implants is 160 Gy. Afterloaded 192Ir can be used as a temporary implant in single or multiple planes for either microscopic residual disease or unresected disease. Typical median peripheral doses are 45 Gy for microscopic disease and 60 Gy for gross disease. A patient with a resectable submandibular cancer with lung metastases who was treated with 125I is illustrated in Fig. 32-26.

Pleomorphic Adenoma (Benign Mixed Tumor)

Pleomorphic adenomas are radioresponsive tumors. In selected cases that are at high risk for local recurrence, the use of postoperative radiation therapy is associated with a cumulative risk of recurrence of 8% at 20 years.53

There is an established role for the use of radiation therapy in this benign lesion.54–58 The indications for postoperative radiation therapy include (1) more than three histologically benign local recurrences, with each recurrence associated with an increasing degree of infiltration; (2) a large lesion (>3 to 5 cm) for which surgery is associated with inadequate margins; (3) microscopically positive surgical margins; (4) macroscopic residual disease; and (5) malignant transformation54 (Table 32-16). Previously, postoperative radiation therapy was indicated if there was tumor spill during surgery, but now this is not felt to be the case.58a

Table 32-16 Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Pleomorphic Adenomas

Minor Salivary Gland Tumors

Pathologic Conditions

In general adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most-often encountered malignant minor salivary gland tumor. However, adenocarcinoma is most common in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses,11 whereas mucoepidermoid carcinoma is highest in the oropharyngeal region, particularly in the base of tongue.59

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

Regional Lymph Nodes

There is an overall 15% risk for cervical lymph node metastasis. This risk, however, is related to the site of origin and the grade of tumor.11 The physical examination should include palpation of regional nodes. There may be an increased risk for bilateral or contralateral nodal metastasis, particularly when the primary site is in the oral cavity or oropharynx because of the rich lymphatic pathways in these regions.

Treatment

Surgery

Surgical resection of malignant minor salivary gland tumors is the primary treatment of choice. However, patients must be carefully selected to ensure resectability. A review of the MSKCC experience by Spiro noted that there were fewer early-stage lesions for the minor salivary gland lesions compared with the major salivary gland malignancies.11 In fact, almost all of the minor salivary gland malignancies were locally advanced.

Radiation Oncology

Indications for Primary Treatment With Radiation Therapy

Patients with disease in inaccessible sites or sites where the required surgery would have unacceptable cosmetic or functional results can be treated with radical radiation alone. The techniques are similar to those used for squamous cell cancers in the same location. The radiation doses are similar to those previously presented for the major salivary gland malignancies. The results of radiation alone for minor salivary cancers are detailed in Table 32-9. Although relatively small numbers are reported, local control is between 70% and 100%.

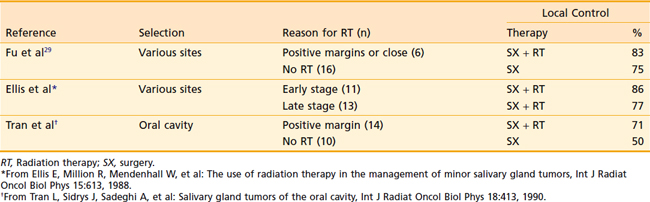

Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy

Few data are available to support the use of postoperative radiation therapy for minor salivary gland malignancies compared with the data available for such treatment in major salivary gland malignancies. Postoperative external-beam radiation therapy has been reported for minor salivary gland malignancies with a local control rate of 75%,61–64 compared with 50% reported for surgery alone.60,61,64 Several series using postoperative radiation therapy for minor salivary gland malignancies are detailed in Table 32-17.

Table 32-17 Effect of Postoperative Radiation Therapy on Local Control in Cancer of Minor Salivary Glands

It is hard to make conclusions based on such limited data; however, it appears that postoperative radiation may improve outcome in selected patients. There is no good hypothesis to explain why postoperative radiation is effective for selected major salivary gland cancers and ineffective for selected minor salivary gland cancers. Therefore, it is reasonable to recommend postoperative radiation therapy for the following indications: (1) resectable primary T3-T4 and recurrent tumors, (2) unresectable or partially resected gross residual disease, (3) close or microscopically positive surgical margins, (4) perineural or vascular invasion, (5) positive or close surgical margins, (6) high-grade histologic findings, (7) adenoid cystic carcinoma, (8) locoregional lymph node metastasis, (9) concern of the surgeon over the margins of resection or conduct of the procedure (e.g., piecemeal resection, tumor spillage) irrespective of the pathology report (Table 32-18).

Table 32-18 Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Minor Salivary Gland Malignancies

1 Frommer J. The human accessory parotid gland: its incidence, nature and significance. Oral Surg. 1977;43:671.

2 Johnson FE, Spiro RH. Tumors arising in accessory parotid tissue. Am J Surg. 1979;138:576.

3 Spiro JD, Spiro RH. Salivary tumors. In: Shah J, editor. Cancer of the head and neck. Hamilton, Ontario/London: BC Decker; 2001:240.

4 Eisele DW, Kleinberg LR, O’Malley BB. Management of malignant salivary gland tumors. In: Harrison LB, Sessions RB, Hong WK, editors. Head and neck cancer. A multidisciplinary approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999:721.

5 O’Dwyer P, Farrar WB, James A. Needle aspiration biopsy of major salivary gland tumors: its value. Cancer. 1986;57:554.

6 Frable MAS, Frable WJ. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of salivary glands. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:245.

7 Roland NJ, Caslin AW, Smith PA, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions reported immediately in a head and neck clinic. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1025.

8 Zurrida S, Alasio L, Tradati N, et al. Fine needle aspiration of parotid masses. Cancer. 1993;72:2306.

9 Layfield JL, Tan P, Glasgow BJ. Fine needle aspiration of salivary gland lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:346.

10 Jayaram G, Verma AK, Sood N, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:256.

11 Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2807 patients. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8:177.

12 Armstrong JG, Harrison LG, Spiro RH, et al. The indications for elective treatment of the neck in cancer of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 1992;69:615.

13 Wang CC. Tumors of the salivary glands. In: Wang CC, editor. Radiation therapy for head and neck neoplasms. ed 3. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997:311.

14 American Joint Committee on Cancer, Major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual). ed 7. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 2010; Springer, New York:79.

15 American Joint Committee on Cancer. Major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual. In: Greene Fl, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. ed 6. New York: Springer; 2002:69.

16 Personal communication with Jatin P. Shah, Chief, Head and Neck Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

17 McGuitt WF. Effect of radiation therapy on facial nerve cable autografts. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1976;82:487.

18 Wang CC, Goodman M. Photon irradiation of unresectable carcinomas of salivary glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:569.

19 Armstrong JG, Harrison LB, Spiro RH, et al. Brachytherapy of malignant tumors of salivary gland origin. Endocurither Hypertherm Oncol. 1996;6:19.

20 King JJ, Fletcher GH. Malignant tumors of the major salivary glands. Radiology. 1971;123:49.

21 Batterman J, Breuer K, Hart G, et al. Observations on pulmonary metastases in patients after single doses and multiple fractions of fast neutrons and cobalt-60 gamma rays. Eur J Cancer. 1981;17:539.

22 Laramore G, Krall J, Griffin T, et al. Neutron versus photon irradiation for unresectable salivary gland tumors: final report of an RTOG-MRC randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:235.

23 Catterall M, Errington RD. The implications of improved treatment of malignant salivary gland tumors by fast neutron radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1314.

24 Prott FJ, Micke O, Haverkamp U, et al. Results of fast neutron therapy of adenoid cystic carcinomas of the salivary glands. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(5C):3743.

25 Huber PE, Debus J, Latz D, et al. Radiotherapy for advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma: neutrons, photons or mixed beam? Radiother Oncol. 2001;59(2):161.

26 Douglas JG, Koh WJ, Austin-Seymour M, et al. Treatment of salivary gland neoplasms with fast neutron radiotherapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(9):944.

27 Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Cancer of the parotid gland: a clinicopathologic study of 288 primary cases. Am J Surg. 1975;130:457.

28 Harrison LB, Armstrong JG, Spiro RH. Postoperative radiation therapy for major salivary gland malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 1990;45:52.

29 Fu KK, Leibel SA, Levine ML, et al. Carcinoma of the major and minor salivary glands. Cancer. 1977;40:2882.

30 Armstrong JG, Harrison LB, Spiro RH, et al. Malignant tumors of major salivary gland origin: a matched pair analysis of the role of combined surgery and postoperative radiation therapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:290.

31 Chong LM, Hunt M. Intensity modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. In: Fuks Z, Leibel SA, Ling CC, editors. A practical guide to intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Madison, Wisc: Medical Physics Publishing, 2003.

32 Leblanc A. The cranial nerves, ed 2. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1995.

33 Nowak PJ, Wijers OB, Lagerwaard FJ, et al. A three-dimensional CT-based target definition for elective radiation of the neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:33.

34 Wijers OB, Levendag PC, Tan T, et al. A simplified CT-based definition of the lymph node levels in the node negative neck. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52:35.

35 Chao KSC, Wippold FJ, et al. Determination and delineation of nodal target volumes for head and neck cancer based on patterns of failure in patients receiving definitive and postoperative IMRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:1174.

36 Marks J, Davis CC, Gottsman VL, et al. The effects of radiation on parotid salivary function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:1013.

37 Mira J, Wescott W, Starcke E, et al. Some factors influencing salivary function when treating with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:535.

38 Lawson W, Som ML. Second primary cancer after irradiation of laryngeal cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1975;84:771.

39 Belsky JL, Takechi N, Yamamoto T, et al. Salivary gland neoplasms following atomic radiation: additional cases and reanalysis of combined data in a fixed population, 1957–1970. Cancer. 1975;35:555.

40 Dreyfus AI, Clark JR, Fallon BG, et al. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin combination chemotherapy for advanced carcinomas of salivary gland origin. Cancer. 1987;60:2869.

41 Kaplan MJ, Johns ME, Cantrell RW. Chemotherapy for salivary gland cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1966;95:165.

42 Dimery IW, Legha SS, Shirinian M, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and cisplatin combination chemotherapy in advanced or recurrent salivary gland carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1056.

43 Licitra L, Marchini S, Spinazze S, et al. Cisplatin in advanced salivary gland carcinoma. Cancer. 1991;68:1874.

44 Creaghan ET, Woods JE, Rubin J, et al. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy for neoplasms arising from salivary glands and contiguous structures in the head and neck. Cancer. 1988;62:2313.

45 Garden AS, Weber RS, Morrison WH, et al. The influence of positive margins and nerve invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck treated with surgery and radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:619.

46 Spiro RH, Huvos AG. Stage means more than grade in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1992;164:230.

47 Armstrong JG, Harrison LB, Spiro RH, et al. Observation on the natural history and treatment of recurrent major salivary gland cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1990;44:138.

48 Spiro R, Spiro J. Cancer of the salivary glands. In: Meyers E, Sven J, editors. Cancer of the head and neck. ed 2. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1984:645.

48a Armstrong JG: Unpublished data.

49 Guillamondejui OM, Byers RM, Luna MH, et al. Aggressive surgery in treatment for parotid cancer. The role of adjunctive postoperative radiotherapy. Am J Roentgenol. 1975;123:49.

50 King JJ, Fletcher GH. Malignant tumors of the major salivary glands. Radiology. 1971;100:381.

51 Tu G-Y, Hu Y, Jiang P, et al. The superiority of combined therapy (surgery and postoperative irradiation) in parotid cancer. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:710.

52 Woods J, Weiland L, Chong G, et al. Pathology and surgery of primary tumors of the parotid. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57:565.

53 Dawson AK, Orr JA. Long-term results of local excision and radiotherapy in pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Int J Radiat Ncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:4.

54 Chen AM, Garcia J, Bucci MK, et al. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: long-term outcome of patients treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(4):1031.

55 Leverstein H, Tiwari RM, Snow GB. The surgical management of recurrent or residual pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Analysis and results in 40 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.. 1997;254(7):313.

56 Barton J, Slevin NJ, Gleave EN. Radiotherapy for pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22(5):925.

57 Touquet R, Mackenzie IJ, Carruth JA. Management of the parotid pleomorphic adenoma, the problem of exposing tumour tissue at operation. The logical pursuit of treatment policies. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28(6):404.

58 Carew JF, Spiro RH, Singh B, et al. Treatment of recurrent pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(5):539.

58a Buchman C, Stringer SP, Mendenhall WM, et al. Pleomorphic adenoma: effect of tumor spill and inadequate resection on tumor recurrence. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1231-1234.

59 DeVries EJ, Johnson JT, Meyers EN, et al. Base of tongue salivary gland tumors. Head Neck Surg. 1987;9:329.

60 Spiro RH, Thaler HT, Hicks WF. The importance of clinical staging of minor salivary gland carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1991;162:330.

61 Eapen LJ, Gerig LH, Catton GE, et al. Impact of local radiation in the management of salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10:239.

62 Garden AS, Weber RS, Ang KK, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy for malignant tumors of minor salivary glands. Outcomes and patterns of failure. Cancer. 1994;73:2563.

63 Parson JT, Mendenhall WM, Strenger SP, et al. Management of minor salivary gland carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:443.

64 Sadeghi A, Tran LM, Mark R, et al. Minor salivary gland tumors of the head and neck: treatment strategies and prognosis. Am J Clin Oncol. 1993;16:3.