13 Trigger Point Injections

Trigger Points versus Tender Spots

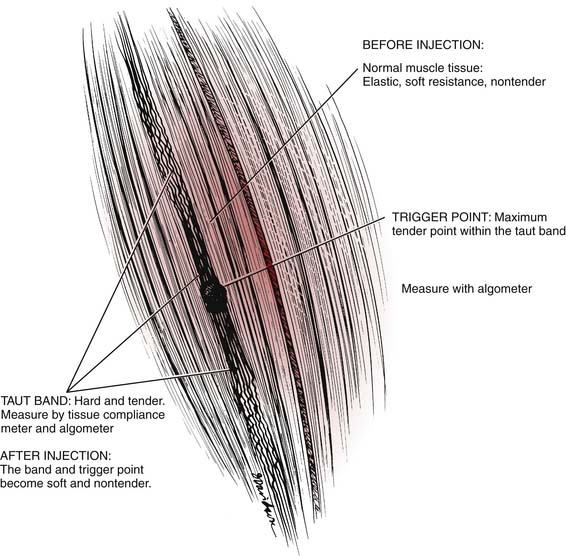

Trigger points (TrPs) are small, exquisitely tender areas in various soft tissues, including muscles, ligaments, periosteum, tendons, and pericapsular areas.1–1d These points may radiate pain into a specific distant area called a “reference pain zone.”1d–9 The referred pain may be present at rest. The pain may occur only on activation of the trigger point by local pressure, piercing by an injection needle, or activity of the involved muscle (particularly its overuse). TrPs located in muscles are called myofascial because they also may involve the fascia. In addition to the focal tenderness, they are characterized by the presence of a taut band6,8,9 that is sensitive to pressure, which indicates sensitization of the nerve endings within. The hard resistance to palpation and needle penetration is interpreted as evidence that a group of the affected muscle fibers is constantly contracted. Later, approximately 6 to 8 weeks after an injury, the resistance to the needle usually becomes very hard. This is characteristic of fibrotic (scar) tissues that fail to respond to conservative therapy. Because there are no definitive histologic studies of TrPs at different stages, it may be assumed that the damaged tissue has healed by a scar.

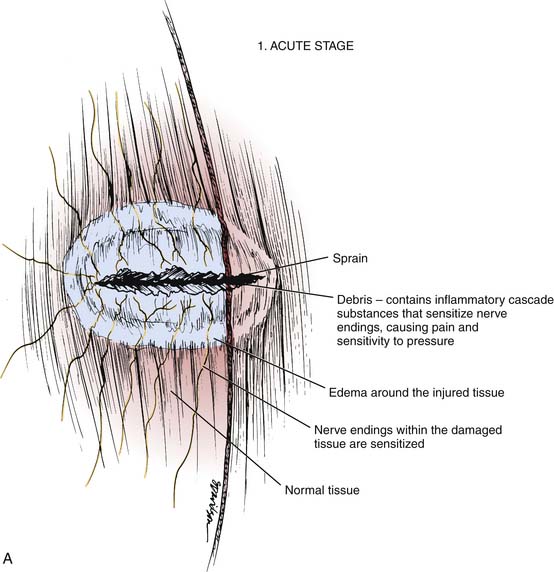

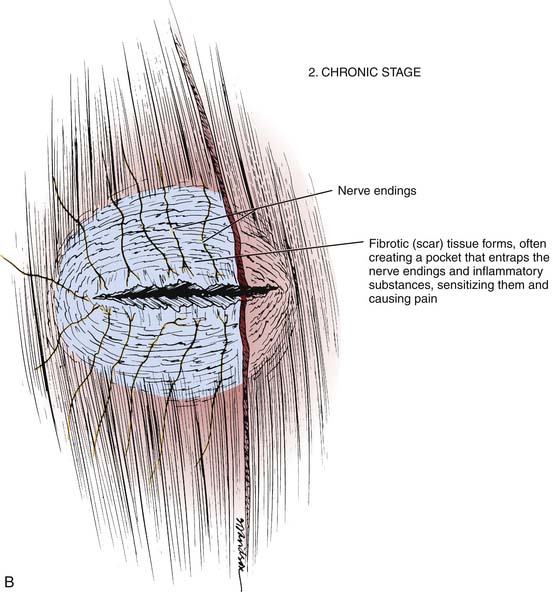

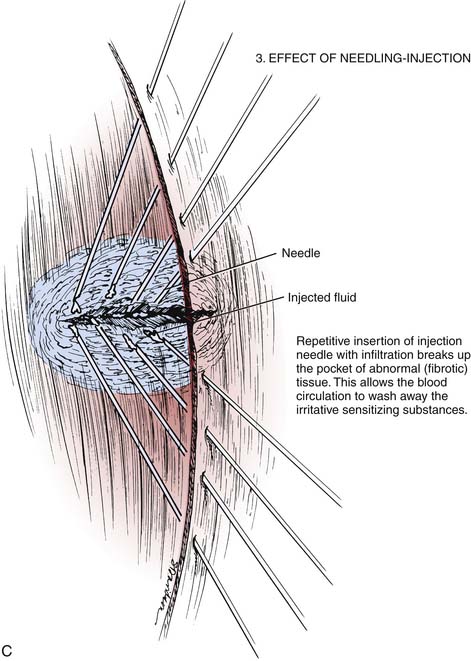

Commonly, tender spots and some TrPs represent local tissue damage that causes inflammation and irritation that can be diagnosed by increased sensitivity to pressure. Figures 13-1 and 13-2 illustrate a possible concept of pathologic changes following local tissue damage. This hypothesis may explain clinical findings in acute and chronic injury and the effect of needling. Conceptually, the TSs or TrP at the chronic stage can be thought of as a pocket of fibrotic tissue that contains sensitizing agents that are the products of tissue damage. These substances cause sensitization of the entrapped nerve fibers. This sensitization increases the nerve’s reactivity so that a lower pressure produces pain.

Figure 13-2 and Table 13-1 illustrate physical findings over TrPs and taut bands before, during, and after injection combined with needling. TrPs and TSs are the immediate cause of pain in a variety of conditions. These include sports or work-related injuries, sprains, strains, or muscle tension related to nonphysiologic posture or stress. Headaches also are frequently caused by TrPs. Certain hormonal disorders such as thyroid or estrogen deficiencies are frequent causes and perpetuators of widespread TrPs.

Table 13-1 Physical Findings Before, During, and After Trigger Point Injections

| Before Injection | During Injection | After Injection |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Muscle Tissue | ||

| Elastic soft resistance; nontender | Minimal resistance to needle progression; no pain | Normal tissue findings |

| Taut Band | ||

| Hard and tender. Local twitch response can be elicited on snapping. | Penetration of the needle causes pain and encounters hard resistance as in fibrotic tissue (particularly in chronic TrP). Local twitch response occurs when the needle enters the hyperirritable fibers. | The hard and tender areas on palpation become nontender. Pressure pain sensitivity becomes normal immediately. Soreness from injection resolves in 3-5 days. Local twitch response can no longer be elicited. Hyperirritability resolves. |

| Trigger Point | ||

| Maximum tender point within the taut band. | Maximum pain on needle penetration with hard resistance as in the taut band. | Trigger point sensitivity to pressure disappears. Hard consistency becomes normal, similar to improvement in taut bands. |

TrP, Trigger point.

Trigger Point Injections

Needling represents the most effective treatment of trigger points and TSs.9a–9f Injecting a local anesthetic (usually lidocaine) is combined with a special needling technique to break up the abnormal tissue that causes the pain. The critical factor in TIs is not the injected substance but rather the mechanical disruption of the abnormal tissue and interruption of the TrP mechanism if one has developed.2,10,11 Intensive stimulation also may contribute to the prolonged relief of pain by TrP injections.12 The fact that the symptoms originated in the treated TrP is confirmed by observing whether the pain is reproduced by pressure on the trigger area and relieved after the TrP injection.13 The injections are followed by a specific program of stretching and exercises. After fibrotic tissue (scar) has formed in the damaged tissue, the most effective way to break it up is through needling: the repetitive insertion and withdrawal of the injection needle in the affected area.

Local anesthetics, such as 1% lidocaine or 0.5% procaine, provide temporary relief, lasting about 45 minutes. Long-term relief from pain is achieved by the needling, which mechanically breaks up the abnormal tissue.13a The number of injections needed depends on the number of TrPs present.

Common Trigger Point Injection Techniques

Three commonly employed trigger point techniques include needling combined with infiltration of the entire taut band, technique of Travell and Simons, and injection of corticosteroids. There are some clinicians who have proposed ultrasound guidance in the cervicothoracic regions to prevent complications.13

Trigger Point Injection Techniques

The needle should be sufficiently long to be able to reach deeper than the trigger point. The diameter of the needle should be large enough to facilitate mechanical disruption of the abnormal tissue areas.18 A 22- to 25-gauge needle is usually sufficient. The total amount of 1% lidocaine injected ranges from 1 to 12 mL. Commonly, an extensive area must be infiltrated that ranges from 3 to 25 cm in length and 2 to 10 cm in width. The size of the infiltration depends on the extent of the trigger point and on the length of the affected muscle fibers. At each stop of the needle’s penetration, no more than 0.1 or 0.2 mL should be injected. Larger volumes can damage the muscle, negating any benefit.

Injection Procedure

Postinjection Care

Postinjection care includes the following steps:

Other Injections

1. Fischer A.A. Pressure threshold measurement for diagnosis of myofascial pain and evaluation of treatment results. Clin J Pain. 1987;2:207-214.

1a. Fischer A.A. Documentation of myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:286-291.

1b. Kraus H. Diagnosis and Treatment of Muscle Pain. Chicago: Quintessence; 1988.

1c. Kraus H., Fischer A.A. Diagnosis and treatment of myofascial pain. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58:235-239.

1d. Affaitati G., Fabrizio A., Savini A., et al. A randomized, controlled study comparing a lidocaine patch, a placebo patch, and anesthetic injection for treatment of trigger points in patients with myofascial pain syndrome: Evaluation of pain and somatic pain thresholds. Clin Ther. 2009;31(4):705-720.

2. Fischer A.A. Quantitative and objective compliance recording. In: Nordhoff L.S., editor. Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen; 1996:142-148.

3. Fischer A.A. New approaches in treatment of myofascial pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1997;8:153-169.

4. Fischer A.A. New developments in diagnosis of myofascial pain and fibromyalgia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1997;8:1-21.

5. Fischer A.A. Algometry in diagnosis of musculoskeletal pain and evaluation of treatment outcome: An update. In: Fischer A.A., editor. Muscle Pain Syndromes and Fibromyalgia. New York: Haworth Medical Press; 1998:5-32.

6. Fischer A.A. Treatment of myofascial pain. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 1999;7:131-142.

7. Fischer A.A., Imamura S.T., Imamura M. Myofascial trigger points are most frequently a manifestation of segmental spinal sensitization. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 1998;6(Suppl 2):20.

8. Fischer A.A., Imamura S.T., Kaziyama H.S., Imamura M. Trigger point injections and “paraspinous blocks” which relieve segmental spinal sensitization are effective treatment for chronic pain. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 1998;6(Suppl 2):52.

9. Frost F.A., Jessen B., Siggaard-Andersen J. A control, double-blind comparison of mepivacaine injection versus saline injection for myofascial pain. Lancet. 1980;1:499-500.

9a. Deyo R.A. Conservative therapy for low back pain. Distinguishing useful from useless therapy. JAMA. 1983;250:1057-1062.

9b. Fischer A.A. Diagnosis and management of chronic pain in physical medicine and rehabilitation. In: Ruskin A.P., editor. Current Therapy in Physiatry. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1984.

9c. Garvey T.A., Marks M.R., Wiesel S.W. A prospective, randomized, double-blind evaluation of trigger-point injection therapy for low-back pain. Spine. 1989;14:962-964.

9d. Melzack R. Prolonged relief of pain by brief, intense transcutaneous somatic stimulation. Pain. 1975;1:357-373.

9e. Hackett G.S. Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy, 3rd ed. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1958.

9f. Scott N.A., Guo B., Barton P.M., Gerwin R.D. Trigger point injections for chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Pain Med. 2009;10(1):54-69.

10. Fischer A.A. Local injections in pain management. Trigger point needling with infiltration and somatic blocks. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1995;6:851-870.

11. Fischer A.A. Injection techniques in the management of local pain. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehabil. 1996;7:107-117.

12. Fischer A.A. Myofascial pain. In: Windsor R.E., Lox D.M., editors. Soft Tissue Injuries: Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 1998:85-100.

13. Bonica J.J. Management of myofascial pain syndromes in general practice. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;164:732-738.

13a. Venancio Rde A., Alencar F.G.Jr. Zamperini C. Botulinum toxin, lidocaine, and dry-needling injections in patients with myofascial pain and headaches. Cranio. 2009;27(1):46-53.

14. Simons D.G. Myofascial pain syndromes due to trigger points. In: Goodgold J., editor. Rehabilitation Medicine. St. Louis: Mosby, 1988.

15. Simons D.G. Muscular pain syndromes. In: Fricton J.R., Awad E.A., editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. New York: Raven Press, 1990.

16. Travell J.G., Simons D.G. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Vol. I. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1983.

17. Tavell J.G., Simons D.G. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. The Lower Extremities, Vol. II. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1992.

18. Yoon SH, Rah UW, Sheen SS, Cho KH. Comparison of 3 needle sizes for trigger point injection in myofascial pain syndrome of upper and middle trapezius muscle: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90(8):1332-1339.

19. Botwin K.P., Sharma K., Saliba R., Patel B.C. Ultrasound-guided trigger point injections in the cervicothoracic musculature: A new and unreported technique. Pain Physician. 2008;11(6):885-889.