Trial of Labor and Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery

David H. Chestnut MD

Chapter Outline

PRIMARY CESAREAN DELIVERY: CHOICE OF UTERINE INCISION

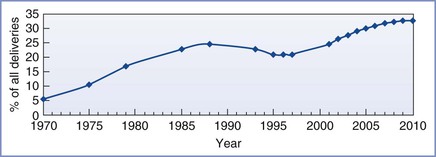

In 1916, Edward Cragin1 stated, “Once a cesarean, always a cesarean.” This edict has had a profound effect on obstetric practice in the United States. The cesarean delivery rate increased from 5.5% of all deliveries in 1970 to 24.7% in 1988 (Figure 19-1). Much of the increase in the cesarean delivery rate resulted from performance of repeat cesarean deliveries. In contemporary practice, elective repeat cesarean deliveries account for one third of all cesarean deliveries. Cesarean delivery is the most frequently performed major surgery in the United States.

For many years most U.S. physicians ignored Cragin’s subsequent statement, “Many exceptions occur.”1 In 1981 the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Conference on Childbirth concluded that vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) is an appropriate option for many women.2 In 1991, Rosen et al.3 modified Cragin’s original dictum as follows: “Once a cesarean, a trial of labor should precede a second cesarean except in the most unusual circumstances.” In 1988 and again in 1994, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)4 concluded: “The concept of routine repeat cesarean birth should be replaced by a specific decision process between the patient and the physician for a subsequent mode of delivery.… In the absence of a contraindication, a woman with one previous cesarean delivery with a lower uterine segment incision should be counseled and encouraged to undergo a trial of labor in her current pregnancy.”

The VBAC rate increased from 2% in 1970 to 28% in 1995. This change in practice helped reduce the overall cesarean delivery rate from 24.7% in 1988 to 20.7% in 1996 (see Figure 19-1). Subsequently the safety of a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) underwent further scrutiny and criticism, and the VBAC rate sharply declined.5 The VBAC rate in the United States dropped from 28% in 1995 to 9% in 2004. Meanwhile, in 2009, the overall cesarean delivery rate rose to 32.9%, the highest rate ever recorded in this country.6

Primary Cesarean Delivery: Choice of Uterine Incision

Obstetric practice in 1916 hardly resembled obstetric practice today. In 1916, only 1% to 2% of all infants were delivered by cesarean delivery. Most cesarean deliveries were performed in patients with a contracted bony pelvis, and obstetricians uniformly performed a classic uterine incision (i.e., a long vertical incision in the upper portion of the uterus) (Figure 19-2). A patient with a classic uterine incision is at high risk for catastrophic uterine rupture during a subsequent pregnancy. Such uterine rupture may occur before or during labor, and it often results in maternal and perinatal morbidity or mortality.

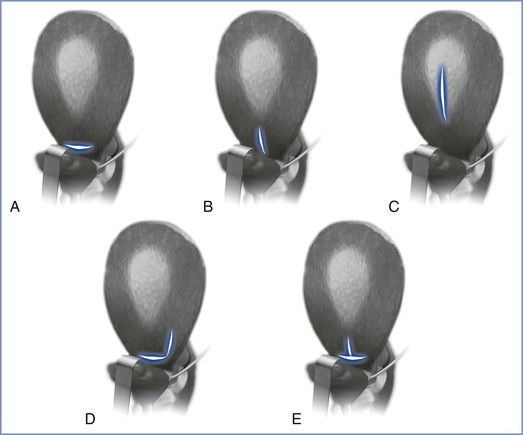

FIGURE 19-2 Uterine incisions for cesarean delivery. A, Low-transverse incision. The bladder is retracted downward, and the incision is made in the lower uterine segment, curving gently upward. If the lower segment is poorly developed, the incision also can curve sharply upward at each end to avoid extending into the ascending branches of the uterine arteries. B, Low-vertical incision. The incision is made vertically in the lower uterine segment after reflection of the bladder, with avoidance of extension into the bladder below. If more room is needed, the incision can be extended upward into the upper uterine segment. C, Classic incision. The incision is entirely within the upper uterine segment and can be at the level shown or in the fundus. D, J-shaped incision. If more room is needed when an initial transverse incision has been made, either end of the incision can be extended upward into the upper uterine segment and parallel to the ascending branch of the uterine artery. E, T-shaped incision. More room can be obtained in a transverse incision by an upward midline extension into the upper uterine segment. (Modified from Landon MB. Cesarean delivery. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 5th edition. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2007:493.)

In 1922, De Lee and Cornell7 advocated the performance of a vertical incision in the lower uterine segment. Unfortunately, low-vertical incisions rarely are confined to the lower uterine segment. Such incisions often extend to the body of the uterus, which does not heal as well as the lower uterine segment. Kerr8 later advocated the performance of a low-transverse uterine incision (see Figure 19-2). A low-transverse uterine incision results in less blood loss and is easier to repair than a classic uterine incision.9 Further, a low-transverse uterine incision is more likely to heal satisfactorily and to maintain its integrity during a subsequent pregnancy. Thus, obstetricians prefer to make a low-transverse uterine incision during most cesarean deliveries.

Obstetricians reserve the low-vertical incision for patients whose lower uterine segment does not have enough width to allow safe delivery. Preterm parturients may have a narrow lower uterine segment. In these patients, delivery through a transverse uterine incision may cause an extension of the incision into the vessels of the broad ligament. For example, a patient with preterm labor at 26 weeks’ gestation may undergo cesarean delivery because of a breech presentation, and the obstetrician may perform a low-vertical incision to facilitate an atraumatic delivery of the fetal head.

Obstetricians rarely perform a classic uterine incision in modern obstetric practice. An obstetrician may perform a classic uterine incision when the need for extensive intrauterine manipulation of the fetus (e.g., delivery of a fetus with a transverse lie) is anticipated. Some obstetricians prefer a classic uterine incision in patients with an anterior placenta previa. In such cases, the performance of a classic incision allows the obstetrician to avoid cutting through the placenta, which might result in significant hemorrhage.

Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes

Multiple studies have demonstrated that TOLAC results in a successful VBAC in 60% to 80% of women in whom a low-transverse uterine incision was made for a previous cesarean delivery.10–13 A 2010 National Institute of Health (NIH) consensus development panel14 concluded that although the TOLAC rate has declined dramatically in recent years, the VBAC rate after TOLAC has remained constant at approximately 74%. However, the panel acknowledged that many published studies were observational and did not address issues of selection bias. The panel also noted that a history of vaginal delivery, either before or after a prior cesarean delivery, is consistently associated with an increased likelihood of successful VBAC.14

Maternal Outcomes

Flamm et al.10 performed a prospective multicenter study of TOLAC. Of the 7229 patients, 5022 (70%) underwent TOLAC and 2207 underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery. Some 3746 (75%) of the women who opted for TOLAC delivered vaginally. The incidence of uterine rupture was 0.8%. The incidence of postpartum transfusion, the incidence of postpartum fever, and the duration of hospitalization were significantly lower in the TOLAC group than in the elective repeat cesarean group. Likewise, in a 1991 meta-analysis of 31 studies, Rosen et al.3 noted that maternal febrile morbidity was significantly lower among women who attempted VBAC than among those who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery.

In contrast, McMahon et al.15 performed a population-based longitudinal study of 6138 women in Nova Scotia who had previously undergone cesarean delivery and who delivered a single live infant between 1986 and 1992. Some 3249 women attempted VBAC, and 2889 women chose a repeat cesarean delivery. There was no difference between the two groups in the incidence of “minor complications” (e.g., puerperal fever, transfusion, wound infection). However, “major complications” (e.g., hysterectomy, uterine rupture, operative injury) were nearly twice as common among women who attempted VBAC than among women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery.

Landon et al.11 subsequently conducted a prospective 4-year observational study of all parturients with a singleton gestation and a prior cesarean delivery at 19 academic medical centers. Among the 17,898 women who attempted VBAC, 13,139 (73.4%) delivered vaginally. Symptomatic uterine rupture occurred in 124 (0.7%) women who underwent a trial of labor. The rate of endometritis was higher in women who underwent a trial of labor than in women who had an elective repeat cesarean delivery (2.9% versus 1.8%), as was the rate of blood transfusion (1.7% versus 1.0%).15

In a 2004 systematic review of published studies of attempted VBAC, Guise et al.16 observed no significant difference in the incidence of maternal death or hysterectomy between women who attempted a trial of labor and those who underwent repeat cesarean delivery. Uterine rupture was more common in the women who attempted a trial of labor, but the rates of asymptomatic uterine dehiscence did not differ.

Wen et al.17 performed a retrospective cohort comparison of outcomes after TOLAC or elective repeat cesarean delivery in 308,755 Canadian women with a history of previous cesarean delivery. These investigators observed that the rates of uterine rupture (0.65%), transfusion (0.19%), and hysterectomy (0.10%) were significantly higher in the TOLAC group. However, the maternal in-hospital death rate was significantly lower in the TOLAC group (1.6 per 100,000) than in the elective cesarean delivery group (5.6 per 100,000). Similarly, Guise et al.18 observed a lower maternal mortality rate in women who underwent TOLAC than in women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery (0.004% versus 0.013%, respectively).

Cahill et al.19 performed a multicenter cohort study in which they concluded that among TOLAC candidates who had a prior vaginal delivery, those who attempted VBAC had a lower risk for overall major maternal morbidities, as well as maternal fever and transfusion, than women who chose repeat cesarean delivery. These investigators concluded that women who have had a prior vaginal delivery have “less composite maternal morbidity if they attempt VBAC compared with [those] undergoing an elective repeat cesarean delivery.” Further, they concluded that a trial of labor is “a safer overall option for women who have had a prior vaginal birth.”19

Rossi and D’Addario12 performed a meta-analysis of studies published in 2000-2007 that compared maternal morbidity in women who underwent TOLAC versus women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery. Successful VBAC occurred in 17,905 (73%) of 24,349 women who underwent TOLAC. Overall maternal morbidity did not differ between women who underwent TOLAC and women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery. Likewise, the incidence of blood transfusion and hysterectomy did not differ between the two groups. The incidence of uterine rupture was higher in the TOLAC group (1.3% versus 0.4%). Further, maternal morbidity, uterine rupture, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy were more common in women who had a failed TOLAC.

The 2010 NIH consensus development panel14 noted that the overall benefits of TOLAC “are directly related to having a [successful] VBAC as these women typically have the lowest morbidity.” Likewise, the panel noted that the harms of TOLAC “are associated with an unsuccessful trial of labor resulting in cesarean delivery because these deliveries have the highest morbidity.” However, the panel concluded that women who undergo TOLAC, regardless of the ultimate mode of delivery, are at decreased risk for maternal mortality compared with women who undergo elective repeat cesarean delivery. The panel also cited low-grade evidence of a shorter hospitalization overall for women attempting TOLAC compared with women undergoing elective repeat cesarean delivery.

Neonatal Outcomes

Lydon-Rochelle et al.20 conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort analysis of obstetric outcomes for all 20,095 nulliparous women who gave birth to a live singleton infant by cesarean delivery in civilian hospitals in Washington between 1987 and 1996 and who subsequently delivered a second singleton child during the same period. These investigators observed that spontaneous labor was associated with a tripling of the risk for uterine rupture (i.e., a uterine rupture rate of 5.2 per 1000 women who had spontaneous onset of labor versus 1.6 per 1000 women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery without labor). Further, the incidence of infant death was more than 10 times higher among the 91 women who experienced uterine rupture than among the 20,004 who did not (i.e., a 5.5% incidence of infant death versus a 0.5% incidence, respectively).20

In the study performed by McMahon et al.15 there was no difference between the two groups in perinatal mortality or morbidity. However, two perinatal deaths occurred after uterine rupture in the TOLAC group. Landon et al.11 observed that hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy occurred in no infants whose mothers underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery and in 12 infants delivered at term whose mothers underwent a trial of labor (P < .001).

The 2010 NIH consensus development panel14 concluded that the perinatal mortality rate (death between 20 weeks’ gestation and 28 days of life) is increased with TOLAC when compared with elective repeat cesarean delivery (i.e., 130 deaths per 100,000 infants compared with 50 deaths per 100,000 infants, respectively). Likewise, the panel concluded that the neonatal mortality rate (death in the first 28 days of life) is also increased with TOLAC when compared with elective repeat cesarean delivery (110 deaths per 100,000 infants versus 50 deaths per 100,000 infants, respectively).14

On the other hand, successful VBAC avoids the neonatal risks of elective cesarean delivery. Inappropriate assessment of gestational age or fetal maturity occasionally leads to the delivery of a preterm infant. Elective cesarean delivery results in some cases of iatrogenic neonatal respiratory sequelae, including respiratory distress syndrome and transient tachypnea of the newborn. Kamath et al.21 observed that newborns born after elective repeat cesarean delivery had significantly higher rates of respiratory morbidity and neonatal intensive care unit admission—and a longer length of hospital stay—than infants whose mothers attempted VBAC. However, the 2010 NIH consensus development panel14 concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether substantial differences in respiratory outcomes occur in infants born via elective repeat cesarean delivery compared with infants born after TOLAC.

Eligibility and Selection Criteria

Most studies suggest a high likelihood of success with TOLAC, even in women in whom the indication for previous cesarean delivery was dystocia or failure to progress in labor. Rosen and Dickinson22 performed a meta-analysis of 29 studies of attempted VBAC. Among women whose previous cesarean deliveries were performed for dystocia or cephalopelvic disproportion, the average rate of successful VBAC was 67%. Later studies have concluded that a history of previous vaginal delivery (including previous VBAC) is the greatest predictor for successful VBAC.23

The highest risk for maternal morbidity and mortality is associated with unsuccessful TOLAC.14 The ACOG13 concluded that women with at least a 60% to 70% chance of successful VBAC have equal or less maternal morbidity when they undergo TOLAC than women who undergo elective repeat cesarean delivery. Conversely, the ACOG13 noted that women who have a lower than 60% probability of successful VBAC have a greater likelihood of morbidity than women who undergo elective repeat cesarean delivery. Thus, the ability to identify women with a high likelihood of successful VBAC would improve the safety of TOLAC. Investigators have attempted to develop reliable scoring systems for predicting the success or failure of TOLAC, with limited success. Grobman et al.24 developed a nomogram specifically for women undergoing TOLAC at term gestation with one previous low-transverse cesarean delivery, a singleton gestation, and a vertex fetal presentation. The nomogram incorporates six variables that may be ascertained at the first prenatal visit; those variables include maternal age, body mass index, ethnicity, prior vaginal delivery, prior VBAC, and a recurring indication for cesarean delivery. This model was validated in a subsequent study.25

The ACOG13 concluded that the “preponderance of evidence suggests that most women with one previous cesarean delivery with a low-transverse incision are candidates for and should be counseled about VBAC and offered TOLAC.” A history of dystocia, a need for induction of labor, and maternal obesity are associated with a lower likelihood of successful VBAC.24,26–28

History of More Than One Cesarean Delivery

Studies that have assessed outcomes of TOLAC in women with a history of more than one cesarean delivery have not demonstrated consistent conclusions. One large multicenter study found no increased risk for uterine rupture (0.9% versus 0.7%) in women with more than one previous cesarean delivery, when compared with women with only one previous cesarean delivery.29 A second large study observed that the risk for uterine rupture increased from 0.9% to 1.8% during TOLAC in women with two previous cesarean deliveries.30 Both studies observed that TOLAC was associated with some increase in maternal morbidity in women with more than one previous cesarean delivery, although the absolute magnitude of the difference in morbidity was relatively small.29,30 The ACOG13 concluded that it is reasonable to consider TOLAC for women with two previous low-transverse cesarean deliveries. Data regarding the risk of TOLAC in women with more than two previous cesarean deliveries are limited.13

Previous Low-Vertical Incision

Some obstetricians allow a trial of labor after a previous low-vertical uterine incision, provided that there is documentation that the uterine incision was confined to the lower uterine segment. (Low-vertical uterine incisions often extend above the lower uterine segment, especially when performed in preterm patients.) Naef et al.31 retrospectively reviewed outcomes for 174 women who attempted VBAC after a previous low-vertical cesarean delivery; 144 (83%) women delivered vaginally. Uterine rupture occurred in 2 (1.1%) of the patients. These investigators concluded that “the likelihood of successful outcome and the incidence of complications are comparable to those of published experience with a trial of labor after a previous low-segment transverse incision.”31 Adair et al.32 made similar observations. The ACOG13 concluded that there is no consistent evidence of an increased risk for uterine rupture in women with a previous low-vertical uterine incision, and that obstetricians and patients may choose to undergo TOLAC in the presence of a documented prior low-vertical uterine incision.

Twin Gestation

Some obstetricians believe that uterine overdistention, which occurs with twin gestation, increases the risk for uterine rupture in patients with a history of previous cesarean delivery. Early reports suggested otherwise, but these studies were limited by the small number of patients.33,34 Cahill et al.35 performed a retrospective cohort study of 25,005 obstetric patients with at least one previous cesarean delivery, which included 535 patients with a twin pregnancy. The investigators observed that women with a twin gestation were less likely to attempt VBAC but were no more likely to have a failed VBAC or to experience major morbidity than women with a singleton gestation.

Likewise, a report from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Unit Cesarean Registry36 included outcome measures for 186 women with a twin gestation who attempted VBAC. Some 120 (64.5%) women delivered vaginally. Women who attempted a trial of labor with twin gestation had no higher risk for transfusion, endometritis, intensive care unit admission, or uterine rupture than women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery. The investigators concluded that a trial of labor in women with a twin gestation after previous cesarean delivery does not appear to be associated with a higher risk for maternal morbidity.36

Ford et al.37 subsequently examined outcomes for 6555 women with a twin gestation who delivered between 1993 and 2002. Among 1850 women who underwent a trial of labor, 836 (45.2%) delivered vaginally. The rate of uterine rupture was higher in the trial-of-labor group than in the elective cesarean delivery group (0.9% versus 0.1%), but the rate of wound complications was lower in the trial-of-labor group (0.6% versus 1.3%).

The ACOG13 concluded that “women with one previous cesarean delivery with a low-transverse [uterine] incision, who are otherwise appropriate candidates for twin vaginal delivery, may be considered candidates for TOLAC.”

Unknown Uterine Scar

For some patients, there is no documentation of the type of uterine incision performed during a previous cesarean delivery. Some obstetricians require documentation of the type of previous uterine incision before they allow a patient to attempt VBAC. At least two studies have concluded that a trial of labor does not significantly increase maternal or perinatal mortality in patients with an unknown uterine scar.38,39 Perhaps this conclusion is true because most patients with an unknown uterine scar had a low-transverse uterine incision at previous cesarean delivery. Ultrasonography may help the obstetrician confirm the presence of a low-transverse uterine scar in the pregnant woman with an unknown uterine scar.40 The ACOG13 concluded that “TOLAC is not contraindicated for women with one previous cesarean delivery with an unknown uterine scar type unless there is a high clinical suspicion of a previous classical uterine incision.”

Suspected Macrosomia

In 1994 the ACOG4 concluded that an estimated fetal weight of more than 4000 g does not contraindicate TOLAC. However, in 1999, the ACOG41 included suspected macrosomia on the list of TOLAC eligibility criteria that are controversial. In 2004, the ACOG42 noted that macrosomia is associated with a lower likelihood of successful VBAC but did not include a specific recommendation regarding TOLAC in cases of suspected macrosomia. However, the ACOG cited one report that observed that the rate of uterine rupture appeared to be higher only in women without a previous vaginal delivery.43 A report from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Unit Cesarean Registry44 concluded that for women with a history of previous cesarean delivery for dystocia, a higher birth weight in a subsequent pregnancy (relative to the first pregnancy birth weight) diminishes the chances of successful VBAC. In 2010 the ACOG13 concluded that “suspected macrosomia alone should not preclude the possibility of TOLAC.”

Gestation beyond 40 Weeks

Studies have consistently demonstrated decreased rates of successful VBAC in women who undergo TOLAC after 40 weeks’ gestation.45–47 One study observed an increased incidence of uterine rupture in women undergoing TOLAC beyond 40 weeks’ gestation,47 but other studies (including the largest study46 that has assessed this risk factor) have not confirmed an increased risk for uterine rupture in these patients. The ACOG13 concluded that although the likelihood of successful VBAC may be diminished in more advanced gestations, a “gestational age of greater than 40 weeks alone should not preclude TOLAC.”

Breech Presentation and External Cephalic Version

Breech presentation itself does not increase the risk for uterine rupture. In contemporary practice, most obstetricians do not allow a trial of labor in any patient with a breech presentation. Thus, most patients with a breech presentation undergo elective cesarean delivery, with or without a history of previous cesarean delivery. The ACOG13 concluded that external cephalic version is not contraindicated in women with a previous low-transverse uterine incision who are at low risk for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes from external cephalic version and TOLAC.

Size of Hospital

Most studies of VBAC have been conducted in university or tertiary care hospitals with in-house obstetricians, anesthesia providers, and operating room staff. In 1999 the ACOG41 noted that “the safety of [a] trial of labor is less well documented in smaller community hospitals or facilities where resources may be more limited.” A 2007 study48 evaluated outcomes for women who attempted VBAC in 17 diverse hospitals, including six university hospitals, five community hospitals with an obstetrics-gynecology residency program, and six community hospitals without an obstetrics-gynecology residency program. The incidence of uterine rupture with attempted VBAC was significantly higher in community hospitals than in university hospitals (1.2% versus 0.6%, respectively). However, the rates of maternal blood transfusion and composite adverse maternal outcome were identical in community and university hospitals.48

Contraindications

Social and Economic Factors

Why do most eligible patients choose to undergo elective repeat cesarean delivery? The low frequency of TOLAC has resulted, in part, from both physician and patient preference. VBAC requires more physician effort than elective repeat cesarean delivery. In some cases, physician reimbursement is greater for elective repeat cesarean delivery than for VBAC, despite the fact that VBAC requires greater physician effort.

Stafford49 reviewed the impact of nonclinical factors on the performance of repeat cesarean delivery in California. He observed that “proprietary hospitals, with the greatest incentive to maximize reimbursement, had the highest repeat cesarean [delivery] rates.” Nonteaching hospitals and hospitals with low-volume obstetric services had lower VBAC rates than teaching hospitals and hospitals with high-volume obstetric services. Likewise, Hueston and Rudy50 found that women who undergo elective repeat cesarean delivery are more likely to have private insurance than women who attempt VBAC. Stafford49 concluded: “Because a cesarean [delivery] is nearly twice as costly as a vaginal birth,… the higher repeat cesarean [delivery] rates associated with proprietary hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, and low-volume hospitals contribute to increased health care expenditures.”

In contrast, after assessing both the direct and indirect costs of VBAC, Clark et al.51 concluded that “any economic savings for the healthcare system of a policy of trial of labor are at best marginal, even in a tertiary care center with a success rate for vaginal birth after cesarean of 70%.” Further, they stated that “a policy of trial of labor does not result in any cost saving under most birthing circumstances encountered in the United States today.”51 The ACOG41 had earlier acknowledged that “the difficulty in assessing the cost-benefit of VBAC is that the costs are not all incurred by one entity.” In 2004 the ACOG42 made the following conclusion:

A true analysis of the cost-effectiveness of VBAC should include hospital and physician costs, the method of reimbursement, potential professional liability expenses, and the probability that a woman will continue with childbearing after her first attempt at VBAC. Higher costs may be incurred by a hospital if a woman has a prolonged labor or has significant complications or if the newborn is admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit.

Some women reject TOLAC because they have experienced prolonged, painful labor during a previous pregnancy. They fear that they will again experience a prolonged, painful labor and ultimately need a repeat cesarean delivery. This fear is more common in women who have delivered in smaller hospitals without the availability of neuraxial analgesia during labor. Other women reject TOLAC because they prefer to schedule the date of elective repeat cesarean delivery. (A scheduled, elective cesarean delivery allows the patient to arrange for a relative or friend to provide child care.) Kirk et al.52 questioned 160 women regarding factors affecting their choice between VBAC and elective repeat cesarean delivery. These investigators concluded that “social exigencies appeared to play a more important role than an assessment of the medical risks in making these decisions.” Similarly, Joseph et al.53 observed that fear and inconvenience are the most common deterrents to attempted VBAC. Finally, some women reject a trial of labor because of their concern about the adverse effects of labor and vaginal delivery on the maternal pelvic floor, with the risk for subsequent problems such as urinary and fecal incontinence.

Some insurance carriers previously required that eligible women with a history of previous cesarean delivery attempt VBAC in subsequent pregnancies. These carriers denied partial or full reimbursement to women who chose elective repeat cesarean delivery unless there was a medical reason to perform repeat cesarean delivery. The ACOG and others have agreed that hospitals and insurers should not mandate a trial of labor for pregnant women with a history of previous cesarean delivery.54 In 2004 the ACOG42 concluded, “After thorough counseling that weighs the individual benefits and risks of VBAC, the ultimate decision to attempt this procedure or undergo a repeat cesarean delivery should be made by the patient and her physician.”

Medicolegal Factors

What is the risk for uterine rupture during VBAC? A lower uterine segment scar is relatively avascular, and massive hemorrhage rarely follows separation of a lower segment scar. In contrast, rupture of a classic uterine scar may result in massive intraperitoneal bleeding. Unfortunately, there is some inconsistency and confusion in reports of the incidence of asymptomatic uterine scar dehiscence as opposed to frank uterine rupture. Uterine scar dehiscence may be defined as a uterine wall defect that does not result in fetal compromise or maternal hemorrhage and that does not require emergency cesarean delivery or postpartum laparotomy. In contrast, uterine rupture may be accompanied by extrusion of the fetus or placenta and results in fetal compromise, maternal hemorrhage, or both, sufficient to require cesarean delivery or postpartum laparotomy.55

Some obstetricians have suggested that earlier studies underestimated the risks of TOLAC. Scott56 reported 12 women from Salt Lake City, Utah, who experienced clinically significant uterine rupture during TOLAC. Some of the women did not experience optimal obstetric management. For example, Scott’s series included two women whose labor occurred at home.56 Of interest, the number of home VBACs in the United States increased from 664 in 2003 to approximately 1000 in 2008, perhaps as a result of restricted access to TOLAC in some hospitals.57

Obstetricians understandably fear that they will be found liable if an adverse event occurs during TOLAC. In one case, a jury awarded a verdict of $98.5 million because of a delayed diagnosis of uterine rupture.58 Phelan59 cited another court decision that he predicted would have a “chilling effect on the future of VBAC.” In this case, the fetal heart rate (FHR) was normal until it abruptly decreased to 80 beats per minute at a cervical dilation of 9 cm. The interval between the onset of the FHR deceleration and emergency cesarean delivery was 27 minutes. At delivery, the fetal head was found in the left adnexa. The mother required transfusion, and the child suffered from developmental delay and cerebral palsy. The court found that the defendants were negligent in their failure to deliver the infant in a timely manner and to provide adequate informed consent. The court also concluded that “the ACOG 30-minute rule represented the maximum period of elapse” and did not represent the minimum standard of care. As a result of this verdict, Phelan59 proposed the use of a VBAC consent form that includes the following statement: “I understand that if my uterus ruptures during my VBAC, there may not be sufficient time to operate and to prevent the death of or permanent brain injury to my baby.” Flamm60 responded that “widespread implementation of this or similar consent forms essentially would mean the end of VBAC.”

Greene61 wrote a sobering editorial on the risks of attempted VBAC. Observing that the study performed by Lydon-Rochelle et al.20 was an observational study that reflected “broad experience in a wide range of clinical-practice settings,” he stated that “there is no reason to believe that improvements in clinical care can substantially reduce the risks of uterine rupture and perinatal mortality.” Greene61 concluded his editorial as follows:

After a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of attempting a vaginal delivery after cesarean section, a patient might ask, “But doctor, what is the safest thing for my baby?” Given the findings of Lydon-Rochelle et al., my unequivocal answer: elective repeated cesarean section.

In an earlier editorial, Pitkin62 made the following statement regarding VBAC: “Many women with previous cesareans can be delivered vaginally, and thereby gain substantial advantage, but neither the decision for trial [of] labor nor management during that labor should be arrived at in a cavalier or superficial manner.”

Professional Society Practice Guidelines

In 1999 the ACOG41 issued guidelines stating that because uterine rupture may be catastrophic, VBAC should be attempted in institutions equipped to respond to emergencies with physicians immediately available to provide emergency care. The ACOG63 defended this guideline by noting that “VBAC is a completely elective procedure that allows for reasonable precautions in assuming this small but significant risk [of uterine rupture].” In contrast, other obstetric catastrophes (e.g., placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse) cannot be predicted. The ACOG63 has also noted that “the operational definition of ‘immediately available’ personnel and facilities remains the purview of each local institution.” However, this requirement for the immediate availability of physicians and other personnel clearly represents a more stringent standard than the “readily available” requirement in other published guidelines for obstetric care.

Earlier, Zlatnik64 made the following comments regarding VBAC in a community hospital: “If a timely cesarean [delivery] cannot be performed in a community hospital, VBAC is out of the question, but the larger question is: Should obstetrics continue to be practiced there? Timely cesarean [delivery] is an essential option for all laboring women.”

In contrast, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)65 published the following recommendations:

Women with one previous cesarean delivery with a low transverse incision are candidates for and should be offered a trial of labor (TOL).…Trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) should not be restricted only to facilities with available surgical teams present throughout labor since there is no evidence that these additional resources result in improved outcomes. At the same time, it is clinically appropriate that a management plan for uterine rupture and other potential emergencies requiring rapid cesarean section should be documented for each woman undergoing TOLAC.

The AAFP65 has argued that the ACOG guidelines suggest that “one rare obstetrical catastrophe (e.g., uterine rupture) merits a level of resource that has not been recommended for other rare obstetrical catastrophes that may actually be more common.” The AAFP has acknowledged that these other complications are “largely not predictable,” whereas a TOLAC is a “planned event that may demand a different degree of preparedness.” Nonetheless, they stated that their recommendations significantly differ from ACOG guidelines because they could find “no evidence to support a different level of care for TOLAC patients.”65

In response, Dr. Gary Hankins, Chair of the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, made the following statement66:

It’s very troubling when people who may not even be qualified to perform a cesarean section start issuing guidelines about the safety of this kind of thing.… Their argument is that the available data don’t prove it’s unsafe—they’re not arguing that it is safe.…Our main concern is with having the best possible outcome for mother and baby. If women are given the true numbers about the bad outcomes that can be associated with VBAC, no woman is going to take the chance [of laboring without immediately available surgical support].

The 2010 NIH consensus development panel14 noted that approximately one third of hospitals and one half of obstetric physicians in the United States no longer offer TOLAC largely because of fear of liability and litigation. The panel14 expressed concern that practice guidelines have created barriers that prevent women from choosing TOLAC. The panel concluded that TOLAC remains “a reasonable option for many pregnant women with one prior low-transverse uterine incision.” The panel acknowledged that decision-making may be difficult, because the benefit of TOLAC for the woman may come at the price of increased risk for the infant. The panel stated that pregnant women should be given the opportunity to make informed decisions about the risks and benefits of TOLAC versus elective repeat cesarean delivery. The panel also urged professional societies to reassess the requirement for immediate availability of surgical and anesthesia providers.

Subsequently the ACOG13 issued a revised practice bulletin, in which they stated that restricting access was not the intention of their “immediately available” requirement. The ACOG13 noted that “much of the data concerning the safety of TOLAC was obtained from centers capable of performing immediate, emergency cesarean delivery.” Further, they stated that “although there is reason to think that rapid availability of cesarean delivery may provide a small incremental benefit in safety, comparative data examining in detail the effect of alternate systems and response times are not available.” A recent study55 evaluated neonatal outcome after 36 cases of uterine rupture that occurred among 11,195 cases of TOLAC between 2000 and 2009. None of the 17 infants who were delivered less than 18 minutes after the identification of uterine rupture had either an umbilical arterial blood pH less than 7.0 or evidence of neurologic injury. In contrast, three infants who were delivered more than 30 minutes after the diagnosis of uterine rupture had an umbilical arterial blood pH less than 6.8 and suffered neonatal neurologic injury.55

The revised ACOG practice bulletin reaffirmed the earlier “immediately available” recommendation, but it also affirmed thoughtful, informed decision-making. Specifically, the ACOG13 concluded:

Because of the risks associated with TOLAC and [because] uterine rupture and other complications may be unpredictable, the College recommends that TOLAC be undertaken in facilities with staff immediately available to provide emergency care. When resources for immediate cesarean delivery are not available, the College recommends that health care providers and patients considering TOLAC discuss the hospital’s resources and availability of obstetric, pediatric, anesthetic, and operating staffs.…The decision to offer and pursue TOLAC in a setting in which the option of immediate cesarean delivery is more limited should be carefully considered by patients and their health care providers. In such situations the best alternative may be to refer patients to a facility with available resources.

Further, the ACOG13 also encouraged respect for patient autonomy, as follows:

Respect for patient autonomy also argues that even if a center does not offer TOLAC, such a policy cannot be used to force women to have cesarean delivery or to deny care to women in labor who decline to have a repeat cesarean delivery.…Respect for patient autonomy supports that patients should be allowed to accept increased levels of risk; however, patients should be clearly informed of such potential increase in risk and management alternatives.

Birnbach et al.67 reviewed the impact of anesthesia provider availability on the incidence of VBAC in the United States. They concluded that the “immediately available” requirement necessitates having an in-hospital anesthesia provider who is not performing another simultaneous anesthetic. Their economic analysis prompted a conclusion that “the minimum requirement to provide immediate anesthesia care for all deliveries would be to have all deliveries at facilities with greater than 1500 deliveries annually.”

Obstetric Management

Intravenous Access and Availability of Blood

It seems prudent to recommend the early establishment of intravenous access in women who undergo TOLAC. Resources for transfusion of blood and blood products should be readily available.

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring

Continuous electronic FHR monitoring represents the best means of detecting uterine rupture.68–70 Rodriguez et al.69 reviewed 76 cases of uterine rupture at their hospital. A nonreassuring FHR pattern occurred in 59 of the 76 patients and was the most reliable sign of uterine rupture.

Intrauterine Pressure Monitoring

The intrauterine pressure catheter provides a quantitative measurement of uterine tone both during and between contractions. In the past, some obstetricians contended that an intrauterine pressure catheter should be used in all patients who undergo TOLAC, arguing that a loss of intrauterine pressure and cessation of labor will signal the occurrence of uterine rupture. In one study,69 39 patients had an intrauterine pressure catheter at the time of uterine rupture. None of these patients experienced an apparent decrease in resting uterine tone or cessation of labor, but 4 patients experienced an increase in baseline uterine tone. In these 4 patients, the increase in baseline uterine tone was associated with severe variable FHR decelerations that prompted immediate cesarean delivery. The authors concluded that the information obtained from the use of the intrauterine pressure catheter did not help obstetricians make the diagnosis of uterine rupture.69

Use of Prostaglandins

Lydon-Rochelle et al.20 observed a uterine rupture rate of 24.5 per 1000 women who attempted VBAC with prostaglandin-induced labor. The ACOG13 cited evidence from small studies that observed an increased risk for uterine rupture after the use of misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) in women who attempted VBAC. The ACOG13,71 has concluded that “misoprostol should not be used for third trimester cervical ripening or labor induction in patients who have had a cesarean delivery or major uterine surgery.”

Induction and Augmentation of Labor

Induction of labor is less likely to result in successful VBAC than spontaneous labor.26 Studies of outcomes after the use of oxytocin augmentation of labor during TOLAC have demonstrated conflicting results.3,20,72–74 In a 1991 meta-analysis of 31 studies of VBAC, Rosen et al.3 noted that the use of oxytocin did not increase the risk for uterine scar dehiscence or rupture during VBAC. In contrast, in one large retrospective study of more than 20,000 women, uterine rupture was nearly five times more common among women undergoing induction of labor with oxytocin than in those who had an elective repeat cesarean delivery.20 Zelop et al.73 observed a higher rate of uterine rupture in women undergoing oxytocin induction of labor for attempted VBAC than in similar women attempting VBAC with spontaneous labor. Further, the rate of uterine rupture was also higher in women receiving oxytocin for augmentation of labor, but the difference was not statistically significant. The ACOG13 has concluded that “the varying outcomes of available studies and small absolute magnitude of the risk reported in those studies support that oxytocin augmentation may be used in patients undergoing TOLAC.”

Anesthetic Management

In the past, some obstetricians contended that epidural analgesia might mask the pain of uterine scar separation or rupture and thereby delay the diagnosis of uterine scar dehiscence or rupture.75,76 Plauché et al.75 stated, “Regional anesthesia, such as epidural anesthesia, blunts the patient’s perception of symptoms and the physician’s ability to elicit signs of early uterine rupture.” Others have argued that the sympathectomy associated with epidural anesthesia might attenuate the maternal compensatory response to the hemorrhage associated with uterine rupture. For example, sympathectomy might prevent the compensatory tachycardia and vasoconstriction that occur during hemorrhage. However, consensus now exists that these concerns do not preclude administration of neuraxial analgesia during TOLAC, for several reasons.

First, pain, uterine tenderness, and tachycardia have low sensitivity as diagnostic symptoms and signs of lower uterine segment scar dehiscence or rupture. Some uterine scars separate painlessly. Many obstetricians have discovered an asymptomatic lower uterine segment scar dehiscence at the time of elective repeat cesarean delivery. Molloy et al.77 reported 8 cases of uterine rupture among 1781 patients who attempted VBAC. None of these 8 patients had abdominal pain, but all had FHR abnormalities. Johnson and Oriol70 reviewed 14 studies of VBAC published between 1980 and 1989. Among 10,967 patients who attempted VBAC, 1623 patients received epidural analgesia. Of those who experienced uterine rupture, 5 of 14 patients (35%) with epidural analgesia experienced abdominal pain, compared with 4 of 23 patients (17%) without epidural analgesia. FHR abnormalities represented the most common sign of uterine rupture among patients who did and did not receive epidural analgesia. None of the investigators in these studies observed that epidural analgesia delayed the diagnosis of uterine rupture.

Second, pain, uterine tenderness, and tachycardia have low specificity as diagnostic symptoms and signs of lower uterine segment scar dehiscence. Case et al.78 reported 20 patients with a history of previous cesarean delivery in whom the indication for urgent repeat cesarean delivery was severe hypogastric pain, tenderness, or both. At surgery, they confirmed the presence of scar dehiscence in only one of the 20 patients. Eckstein et al.79 suggested that the unexpected development of pain during previously successful epidural analgesia might be indicative of uterine rupture. Crawford80 referred to this phenomenon as the “epidural sieve.” Others have described patients who received epidural analgesia and subsequently complained of pain and tenderness secondary to uterine scar rupture.81–84 I have provided epidural analgesia for several patients in whom the first suggestion of scar separation was the sudden and unexpected development of “breakthrough pain” despite the continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic. A recent study85 found evidence of “epidural dose escalation immediately before uterine rupture in women who attempted VBAC, when compared with women who did not have uterine rupture.” The authors concluded that “clinical suspicion for uterine rupture should be high in women who require frequent epidural dosing during a VBAC trial.”85 Thus, epidural analgesia may improve the specificity of abdominal pain as a symptom of uterine scar separation or rupture.

Third, most cases of lower uterine segment scar dehiscence do not lead to severe hemorrhage. In one report of six cases of uterine scar dehiscence or rupture, only one patient had intrapartum vaginal bleeding.68 However, if significant bleeding should occur, epidural anesthesia may attenuate the maternal compensatory response to hemorrhage. Vincent et al.86 observed that epidural anesthesia (median sensory level of T9) significantly worsened maternal hypotension, uterine blood flow, and fetal oxygenation during untreated hemorrhage (20 mL/kg) in gravid ewes. Intravascular volume replacement promptly eliminated the differences between groups in maternal mean arterial pressure, cardiac output, and fetal PaO2. Maternal heart rate did not change significantly during hemorrhage in the control animals. However, there was a significant drop in maternal heart rate during hemorrhage in the animals that received epidural anesthesia.86

Fourth, several published series have reported the successful use of epidural analgesia in women undergoing TOLAC.39,68,80,87–90 There is little evidence that epidural analgesia either decreases the likelihood of vaginal delivery or adversely affects maternal or neonatal outcome in women who have uterine scar separation or rupture. Flamm et al.90 reported a multicenter study of 1776 patients who attempted VBAC. Approximately 134 (74%) of 181 women who received epidural analgesia delivered vaginally, compared with 1180 (74%) of 1595 women who did not receive epidural analgesia. Phelan et al.87 reported that among patients who received both oxytocin augmentation and epidural analgesia, 69% delivered vaginally. This did not differ from the incidence of vaginal delivery among patients who received oxytocin without epidural analgesia. Other investigators have reported results of smaller studies suggesting a lower rate of successful VBAC among patients who received epidural analgesia.88,89 However, this effect was limited to patients who received oxytocin for the induction or augmentation of labor. These investigators concluded that epidural analgesia does not decrease the likelihood of successful VBAC.

Fifth, some obstetricians favor the use of epidural analgesia because it facilitates postpartum uterine exploration to assess the integrity of the uterine scar. Meehan et al.91 earlier supported routine postpartum palpation of the uterine scar. However, Meehan et al.92 subsequently acknowledged that it is not necessary to repair all such defects. Many obstetricians manage asymptomatic uterine scar dehiscence with “expectant observation.” Thus, they argue that routine palpation of the uterine scar is unnecessary after successful VBAC.9

Sixth, epidural analgesia provides rapid access to safe, surgical anesthesia if cesarean delivery or postpartum laparotomy should be required.93

Finally, it is inhumane to deny effective analgesia to women who undergo TOLAC. Further, the ACOG13 has concluded that adequate pain relief may encourage more women to choose TOLAC. Thus, the availability and use of neuraxial analgesia may decrease the incidence of unnecessary repeat cesarean delivery.

The ACOG13 has stated that good and consistent scientific evidence supports a conclusion that epidural analgesia may be used during TOLAC. In my judgment, the availability of neuraxial analgesia is an essential component of a successful VBAC program. It seems reasonable to provide analgesia—but not total anesthesia—during labor in patients attempting VBAC.

References

1. Cragin EB. Conservatism in obstetrics. New York Med J. 1916;104:1–3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. Repeat cesarean birth. [NIH Publication No. 82-2067] Cesarean Childbirth. United States Government Printing Office: Washington DC; 1981:351–374.

3. Rosen MG, Dickinson JC, Westhoff CL. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a meta-analysis of morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:465–470.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Vaginal delivery after a previous cesarean birth. ACOG: Washington, DC; October 1994.

5. Yeh J, Wactawiski-Wende J, Shelton JA, Reschke J. Temporal trend in the rates of trial of labor in low-risk pregnancies and their impact on the rates and success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:144–152.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Births: preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. November, 2011.

7. De Lee JB, Cornell EL. Low cervical cesarean section (laparotrachelotomy). JAMA. 1992;79:109–112.

8. Kerr JMM. The technique of cesarean section, with special reference to the lower uterine segment incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1926;12:729–734.

9. Landon MB. Cesarean delivery. Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 5th edition. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2007:486–520.

10. Flamm BL, Goings JR, Liu Y, Wolde-Tsadik G. Elective repeat cesarean delivery versus trial of labor: a prospective multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:927–932.

11. Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2581–2589.

12. Rossi AC, D’Addario V. Maternal morbidity following a trial of labor after cesarean section vs. elective repeat cesarean delivery: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;224–231.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. ACOG Practice: Washington, DC; August 2010.

14. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1279–1295.

15. McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA, Olshan AF. Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:689–695.

16. Guise JM, Berlin M, McDonagh M, et al. Safety of vaginal birth after cesarean: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:420–429.

17. Wen SW, Rusen ID, Walker M, et al. Comparison of maternal mortality and morbidity between trial of labor and elective cesarean section among women with previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1263–1269.

18. Guise JM, Denman MA, Emeis Cm, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1267–1278.

19. Cahill AG, Stamilio DM, Odibo AO, et al. Is vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) or elective repeat cesarean safer in women with a prior vaginal delivery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1143–1147.

20. Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:3–8.

21. Kamath BD, Todd JK, Glazner JE, et al. Neonatal outcomes after elective cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1231–1238.

22. Rosen MG, Dickinson JC. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a meta-analysis of indicators for success. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:865–869.

23. Mercer BM, Gilbert S, Landon MB, et al. Labor outcomes with increasing number of prior vaginal births after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:285–291.

24. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:806–812.

25. Costantine MM, Fox K, Byers BD, et al. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1029–1033.

26. Landon MB, Leindecker S, Spong CY, et al. The MFMU Cesarean Registry. Factors affecting the success of trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1016–1023.

27. Goodall PT, Ahn JT, Chapa JB, Hibbard JU. Obesity as a risk factor for failed trial of labor in patients with previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1423–1426.

28. Srinivas SK, Stamilio DM, Stevens EJ, et al. Predicting failure of a vaginal birth attempt after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:800–805.

29. Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, et al. Risk of uterine rupture during a trial labor in women with multiple and single prior cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:12–20.

30. Macones GA, Cahill A, Pare E, et al. Obstetric outcomes in women with two prior cesarean deliveries: is vaginal birth after cesarean delivery a viable option? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1223–1228.

31. Naef RW, Ray MA, Chauhan SP, et al. Trial of labor after cesarean delivery with a lower-segment, vertical uterine incision: is it safe? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1666–1674.

32. Adair CD, Sanchez-Ramos L, Whitaker D, et al. Trial of labor in patients with a previous lower uterine vertical cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:966–970.

33. Strong TH, Phelan JP, Ahn MO, Sarno AP. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in the twin gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:29–33.

34. Miller DA, Mullin P, Hou D, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean section in twin gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:194–198.

35. Cahill A, Stamilio DM, Pare E, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) attempt in twin pregnancies: is it safe? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1050–1055.

36. Varner MW, Leindecker S, Spong CY, et al. The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Unit Cesarean Registry: trial of labor with a twin gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:135–140.

37. Ford AD, Bateman BT, Simpson LL. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in twin gestations: a large, nationwide sample of deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1138–1142.

38. Beall M, Eglinton GS, Clark SL, Phelan JP. Vaginal delivery after cesarean section in women with unknown types of uterine scar. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:31–35.

39. Pruett KM, Kirshon B, Cotton DB. Unknown uterine scar and trial of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:807–810.

40. Lonky NM, Worthen N, Ross MG. Prediction of cesarean section scars with ultrasound imaging during pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1989;8:15–19.

41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetricians-Gynecologists. ACOG Practice. July 1999 [Bulletin No. 5. Washington, DC] .

42. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. ACOG Practice. July 2004 [Bulletin No. 54. Washington, DC] .

43. Elkousy MA, Sammel M, Stevens E, et al. The effect of birth weight on vaginal birth after cesarean delivery success rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:824–830.

45. Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Cohen A, et al. Trial of labor after 40 weeks’ gestation in women with prior cesarean. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:391–393.

46. Coassolo KM, Stamilio DM, Pare E, et al. Safety and efficacy of vaginal birth after cesarean attempts at or beyond 40 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:700–706.

47. Kiran TS, Chui YK, Bethel J, Bhal PS. Is gestational age an independent variable affecting uterine scare rupture rates? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:68–71.

48. DeFranco EA, Rampersad R, Atkins KL, et al. Do vaginal birth after cesarean outcomes differ based on hospital setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:400.e1–400.e6.

49. Stafford RS. The impact of nonclinical factors on repeat cesarean section. JAMA. 1991;265:59–63.

50. Hueston WJ, Rudy M. Factors predicting elective repeat cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:741–744.

51. Clark SL, Scott JR, Porter TF, et al. Is vaginal birth after cesarean less expensive than repeat cesarean delivery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:599–602.

52. Kirk EP, Doyle KA, Leigh J, Garrard ML. Vaginal birth after cesarean or repeat cesarean section: medical risks or social realities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:1398–1405.

53. Joseph GF, Stedman CF, Robichaux AG. Vaginal birth after cesarean section: the impact of patient resistance to a trial of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1441–1447.

54. Sachs BP, Kobelin C, Castro MA, Frigoletto F. The risks of lowering the cesarean-delivery rate. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:54–57.

55. Holmgren C, Scott JR, Porter TF, et al. Uterine rupture with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: decision-to-delivery time and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:725–731.

56. Scott JR. Mandatory trial of labor after cesarean delivery: an alternative viewpoint. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:811–814.

57. MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Mathews TJ, Stotland N. Trends and characteristics of home vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in the United States and selected states. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:737–744.

58. Freeman G. $98.5 million verdict in missed uterine rupture. [editor] OB-GYN Malpractice Prev. 1996;3:41–48.

59. Phelan JP. VBAC: Time to reconsider? OBG Management. 1996;(November):62–68.

60. Flamm BL. Once a cesarean, always a controversy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:312–315.

61. Greene MF. Vaginal delivery after cesarean section: is the risk acceptable (editorial)? N Engl J Med. 2001;345:54–55.

62. Pitkin RM. Once a cesarean (editorial)? Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:939.

63. ACOG calls for ‘immediately available’ VBAC services. ASA Newsl. 1999;63:21.

64. Zlatnik FJ. VBAC and the community hospital revisited. Iowa Perinat Lett. 1989;10:20.

65. American Academy of Family Physicians. Trial of Labor after Cesarean (TOLAC), formerly trial of labor versus elective repeat cesarean section for the woman with a previous cesarean section. March. 2005.

66. Sullivan MG. Family physicians’ VBAC guideline raises concern. Ob Gyn News. September 1, 2005.

67. Birnbach DJ, Bucklin BA, Dexter F. Impact of anesthesiologists on the incidence of vaginal birth after cesarean in the United States: role of anesthesia availability, productivity, guidelines, and patient safety. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:318–324.

68. Uppington J. Epidural analgesia and previous caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1983;38:336–341.

69. Rodriguez MH, Masaki DI, Phelan JP, Diaz FG. Uterine rupture: are intrauterine pressure catheters useful in the diagnosis? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:666–669.

70. Johnson C, Oriol N. The role of epidural anesthesia in trial of labor. Reg Anesth. 1990;15:304–308.

71. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Induction of labor for vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. ACOG: Washington, DC; August 2006.

72. Flamm BL, Goings JR, Fuelberth NJ, et al. Oxytocin during labor after previous cesarean section: results of a multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:709–712.

73. Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, et al. Uterine rupture during induced or augmented labor in gravid women with one prior cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:882–886.

74. Harper LM, Cahill AG, Boslaugh S, et al. Association of induction of labor and uterine rupture in women attempting vaginal birth after cesarean: a survival analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:51.e1–51.e5.

75. Plauché WC, Von Almen W, Muller R. Catastrophic uterine rupture. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:792–797.

76. Abraham R, Sadovsky E. Delay in the diagnosis of rupture of the uterus due to epidural anesthesia in labor. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1992;33:239–240.

77. Molloy BG, Sheil O, Duignan NM. Delivery after caesarean section: review of 2176 consecutive cases. Br Med J. 1987;294:1645–1647.

78. Case BD, Corcoran R, Jeffcoate N, Randle GH. Caesarean section and its place in modern obstetric practice. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1971;78:203–214.

79. Eckstein KL, Oberlander SG, Marx GF. Uterine rupture during extradural blockade. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1973;20:566–568.

80. Crawford JS. The epidural sieve and MBC (minimal blocking concentration): a hypothesis. Anaesthesia. 1976;31:1277–1280.

81. Carlsson C, Nybell-Lindahl G, Ingemarsson I. Extradural block in patients who have previously undergone caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:827–830.

82. Rowbottom SJ, Tabrizian I. Epidural analgesia and uterine rupture during labour. Anaesth Intens Care. 1994;22:79–80.

83. Kelly MC, Hill DA, Wilson DB. Low dose epidural bupivacaine/fentanyl infusion does not mask uterine rupture. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1997;6:52–54.

84. Rowbottom SJ, Critchley LAH, Gin T. Uterine rupture and epidural analgesia during trial of labour. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:483–488.

85. Cahill AG, Odibo AO, Allsworth JE, Macones GA. Frequent epidural dosing as a marker for impending uterine rupture in patients who attempt vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:355.e1–355.e5.

86. Vincent RD, Chestnut DH, Sipes SL, et al. Epidural anesthesia worsens uterine blood flow and fetal oxygenation during hemorrhage in gravid ewes. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:799–806.

87. Phelan JP, Clark SL, Diaz F, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1510–1515.

88. Stovall TG, Shaver DC, Solomon SK, Anderson GD. Trial of labor in previous cesarean section patients, excluding classical cesarean sections. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:713–717.

89. Sakala EP, Kaye S, Murray RD, Munson LJ. Epidural analgesia: Effect on the likelihood of a successful trial of labor after cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:886–890.

90. Flamm BL, Lim OW, Jones C, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean section: results of a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1079–1084.

91. Meehan FP, Moolgaoker AS, Stallworthy J. Vaginal delivery under caudal analgesia after caesarean section and other major uterine surgery. Br Med J. 1972;2:740–742.

92. Meehan FP, Burke G, Kehoe JT, Magani IM. True rupture/scar dehiscence in delivery following prior section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1990;31:249–255.

93. Bucklin BA. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1444–1448.